Introduction

Health anxiety (HA) is persistent worry about having or developing a severe illness (Asmundson et al., Reference Asmundson, Abramowitz, Richter and Whedon2010), affecting between 1 and 7% of the general population (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Gregory, Walker, Lambe and Salkovskis2017) and 20% of those surveyed across medical settings (Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Cooper, Crawford, Dupont, Green, Murphy, Salkovskis, Smith, Wang, Bhogal, Keeling, Loebenberg, Seivewright, Walker, Cooper, Evered, Kings, Kramo, McNulty, Nagar, Reid, Sanatinia, Sinclair, Trevor, Watson and Tyrer2011), with higher rates in medical conditions such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) (Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Parker and Salkovskis2020) and chronic pain (Rode et al., Reference Rode, Salkovskis, Dowd and Hanna2006). The empirically grounded cognitive behavioural model of HA, the most widely adopted approach to understanding and treating HA, posits that health-focused anxiety is maintained by thoughts and behaviours designed to alleviate or avoid distress, also known as safety-seeking behaviours (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Warwick and Deale2003; Warwick and Salkovskis, Reference Warwick and Salkovskis1990). Treatment based on this approach has been found to be effective across medical conditions (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Gregory, Walker, Lambe and Salkovskis2017; Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Parker and Salkovskis2020; Petricone-Westwood et al., Reference Petricone-Westwood, Jones, Mutsaers, Leclair, Tomei, Trudel, Dinkel and Lebel2019; Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Wang, Crawford, Dupont, Cooper, Nourmand, Lazarevic, Philip and Tyrer2021).

A related construct, health anxiety by proxy (HAP), describes clinical levels of parental distress and excessive pre-occupation with a child’s health, particularly concerning the child’s wellbeing (Lockhart, Reference Lockhart2016). While this type of worry is typical for parents, it should be conceptualised on a continuum (Fisak et al., Reference Fisak, Holderfield, Douglas-Osborn and Cartwright-Hatton2012), recognising that there is likely to be a subgroup with clinical level of distress of this nature. HAP-associated behaviours are purported to include increased checking and monitoring of physical wellbeing, such as looking for bruises, feeling lymph nodes, and seeking medical advice (Lockhart, Reference Lockhart2016; Thorgaard et al., Reference Thorgaard, Frostholm, Walker, Stengaard-Pedersen, Karlsson, Jensen, Fink and Rask2017). HAP research is still in its infancy, with emerging research exploring HA and HAP in groups of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic (Daniels and Rettie, Reference Daniels and Rettie2022), a parent–child focused HAP clinical case study (Salama et al., Reference Salama, Alnajjar, AbuHeweila, Dukmak, Ikhmayyes and Saadeh2023), the recent development of a measure to assess HAP (Ingeman et al., Reference Ingeman, Frostholm, Frydendal, Wright, Lockhart, Garralda, Kangas and Rask2021), and a treatment protocol (Ingeman et al., Reference Ingeman, Frostholm, Wellnitz, Wright, Frydendal, Onghena and Rask2023). HAP has also been investigated in a study examining mothers of young children where it was reported that mothers with severe HA perceived their children as disproportionately unwell, unnecessarily presenting to healthcare settings for physical investigations (Thorgaard et al., Reference Thorgaard, Frostholm, Walker, Stengaard-Pedersen, Karlsson, Jensen, Fink and Rask2017). This concept also relates to research on intergenerational transmission of anxiety between parents and children (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Murayama and Creswell2019). However, the specific subtype in HAP may offer clearer pathways for more targeted interventions.

Childhood cancer is known to affect around 400,000 children globally (World Health Organization, 2021). It is known that parents of children with cancer experience high stress levels (van Warmerdam et al., Reference van Warmerdam, Zabih, Kurdyak, Sutradhar, Nathan and Gupta2019), with no differences in stress identified between mothers and fathers (Kazak et al., Reference Kazak, Boeving, Alderfer, Hwang and Reilly2005). In a qualitative study, 90% of mothers of children with cancer described being hyperaware of their child’s mood, physical health, and looking for signs of illness recurrence (Tutelman et al., Reference Tutelman, Chambers, Urquhart, Fernandez, Heathcote, Noel, Flanders, Guilcher, Schulte and Stinson2019). Comparatively, increased depressive symptoms were evident in mothers, but anxiety scores were similar (Barrera et al., Reference Barrera, Atenafu, Doyle, Berlin-Romalis and Hancock2012). A recent study (mainly of mothers: 78.1%) found that 21% of parents of children with cancer experienced HA. Similarities were found in HA scores between mothers and fathers; however, only 21.9% were fathers (Bilani et al., Reference Bilani, Jamali, Chahine, Zorkot, Homsi, Saab, Saab, Nabulsi and Chaaya2019). Whilst the worry parents experience about their child with cancer is reasonable given these circumstances, clinical levels of worry can affect functioning in both child and parent. Assessment on whether worry of this nature leads to clinical levels of distress in the parent would offer opportunities for intervention to benefit both child and parent (Klassen et al., Reference Klassen, Klaassen, Dix, Pritchard, Yanofsky, O’Donnell, Scott and Sung2008).

The role of gender is critical to consider in oncology research, as much of the research conducted is on the female parent role. A systematic review reported that 67.3% of caregivers involved in research are mothers (Klassen et al., Reference Klassen, Raina, Reineking, Dix, Pritchard and O’Donnell2007). Therefore, interventions are often based on the experience of mothers (Phares et al., Reference Phares, Lopez, Fields, Kamboukos and Duhig2005), who usually accompany their children to the hospital for treatment. The primary caregiver is often used to describe someone primarily responsible for their child’s care, and the secondary caregiver undertakes some care activities, but fewer than the primary caregiver. Caregiving status is often defined by the degree of responsibility for daily care and medical decision-making, but operational definitions vary across studies. Few studies have directly compared psychological outcomes between primary and secondary caregivers, regardless of gender, limiting a nuanced understanding of caregiver burden. The parent’s role as the primary caregiver for their child with cancer significantly contributes to stress levels, which may be linked to anxiety (Bonner et al., Reference Bonner, Hardy, Willard and Hutchinson2007), suggesting that should a father be the primary caregiver, they could have increased anxiety related to health. Indeed, parental involvement with the child has been widely recognised as a fundamental factor in terms of both child development and parental mental health. Numerous studies have identified close parent–child engagement as a protective factor associated with improved emotional wellbeing and reduced psychological distress for both parties (Li and Guo, Reference Li and Guo2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fan, Shang, Li, He, Cao and Ding2024; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Scheiber, Laughlin and Demir-Lira2025; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Hallingberg, Eriksson, Ng, Hamrik, Kopcakova, Movsesyan, Melkumova, Abdrakhmanova and Badura2022).

It has been suggested that parental age may influence levels of parental distress (Oyarzún-Farías et al., Reference Oyarzún-Farías, Cova and Bustos Navarrete2021); with some studies indicating that younger women (Brunton et al., Reference Brunton, Simpson and Dryer2020) and older women (Jadva et al., Reference Jadva, Lysons, Imrie and Golombok2022) (i.e. either side of the spectrum) report highest rates of anxiety. Social support – whether emotional, informational, or practical – plays a crucial role in mitigating psychological distress; those parents with less support have been found to have higher levels of anxiety and depression (Speechley & Noh, Reference Speechley and Noh1992). Research has reported that social support moderates anxiety levels (Vrijmoet-Wiersma et al., Reference Vrijmoet-Wiersma, van Klink, Kolk, Koopman, Ball and Maarten Egeler2008); however, the extent and sources of support available to caregivers may differ by caregiving role and gender. Primary caregivers in particular may experience increased isolation.

While the transmission of anxiety from parent to child is an established relationship (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Murayama and Creswell2019), less is known about specific subtypes, which may be particularly relevant when a child is unwell, and recovery may be influenced by the wellbeing and functioning of the parent. A better understanding of the presence and key factors in HAP in children who have illnesses, particularly cancer, a worrying condition with life-limiting consequences, could inform the development and adaptation of evidence-based interventions to support parents and children at the most difficult times in their lives.

Aims

This study aims to gain a better understanding of HAP in parents of ‘well’ children and in those with cancer, in order to better understand the potential impact of HAP in parents, and to further provide evidence to support the development of interventions for those affected by HAP where present. Drawing from the literature and what are likely to be key factors in understanding HAP, we will investigate the following questions:

-

(1) Are parental health anxiety, social support, and involvement with child positively associated with HAP in parents of children with cancer and with parents of ‘well’ children?

-

(2) Are there significant between-group differences in relation to HAP when considering gender (male and female), child health status (parents of children and cancer versus parents of ‘well’ children) and role of caregiver (primary and secondary)?

-

(3) To what degree (if at all) do these identified factors of interest (gender, social support, health anxiety, health and caregiver status) account for the variation in HAP in parents of children with cancer and children who are ‘well’, after controlling for involvement with the child?

Method

Design

This study used a cross-sectional online questionnaire design using two groups: parents of children with cancer and parents of ‘well’ children as defined by study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Participants

Participants were English-speaking parents over 18 living in the United Kingdom, who had a living child aged under 18. For parents of children with cancer, the inclusion criteria was a current diagnosis of any cancer type, at any stage, including remission. For parents of ‘well’ children, the inclusion criteria was the absence of any significant health problems that required care from a medical team.

Procedure

Recruitment took place between October 2022 and April 2023 using the snowballing technique on online platforms: social media (Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook), the University of Bath community, and online organisations. Parents of children with cancer were also recruited through cancer charities and an NHS Trust, using recruitment posters displayed in waiting areas/day units, and given to parents by staff during clinics. Prospective participants were invited to click on a live link or QR code to participate.

Initially, participants were presented with an information sheet and inclusion criteria before providing consent to take part. Participants were then presented with a battery of questionnaires pertaining to the study research questions, including demographic questions. De-brief information was given at the end of the questionnaire, including links to support services. After completing the questionnaire in full, participants were offered the opportunity to access a separate link for a voucher prize draw.

Measures

The Health Anxiety by Proxy Scale (HAPYS) is a 27-item measure recently developed with parents in a clinical setting to measure HAP. The questionnaire uses a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (standing for ‘not at all’) to 5 (standing for ‘a lot’). The scale scores from 0 to 104; higher scores indicate greater HA by proxy. The HAPYS has excellent internal and test–retest reliability, and good convergent validity (Ingeman et al., Reference Ingeman, Wright, Frostholm, Frydendal, Ørnbøl and Rask2024). The alpha level in this sample was .965.

The Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) is a 14-item brief screening measure to assess HA levels, scoring from 0 to 42, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of health anxiety. The measure has good internal consistency (α=.81 – .84) (Karademas et al., Reference Karademas, Christopoulou, Dimostheni and Pavlu2008) and adequate test – retest reliability (r=.87) (Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Etzel, Tomarken, Ciesielski and Deacon2011). The alpha level in this sample was .916.

The Social Support Index (SSI) is a 17-item scale that measures the degree to which families give support to others, view their community as a source of support, and feel that community context can provide emotional, esteem, and network support on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (‘strongly agree’) to 5 (‘strongly disagree’). Some of the SSI items (7, 9, 10, 13, 14 and 17) are reversed before scoring. The score for SSI is the sum of all the items. Higher scores represent better quality of social support as well as stronger perceived support. Evidence of internal consistency, test – retest reliability, and concurrent validity has been reported. The alpha reliability for social support was .77 (McCubbin et al., Reference McCubbin, Thompson and McCubbin1996). The alpha level in this sample was .874.

The Parent – Child Joint Activity Scale (PJAS) is a 35-item scale assessing individual time spent with one’s child (Chandani et al., Reference Chandani, Prince and Scott1999). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 for ‘seldom or never’ to 5 for ‘on most days’. A total score is obtained by summing all the 35 items; the higher the final score, the more parents spend time with their child in joint activities. It has high test – retest reliability with α=.91 and good reliability and validity. The alpha level in this sample was .896.

All parents were also invited to answer questions about their age, gender, ethnicity, employment status, education level, social support, diagnosed physical/mental health disorders, relationship status, size of immediate family, number of children, whether they considered themselves the primary or secondary caregiver, and how they heard about the research. They were asked about their child’s age and gender. Parents of children with cancer were asked additional questions relating to their child’s cancer journey.

Planned analysis

The data were assessed for normality using Shapiro – Wilk’s test and Levene’s test for equality of variances. Due to the normality of the data, a Pearson’s correlation was used to explore the relationships between key variables. These analyses were conducted twice due to the use of two categories of participants (parents of children with cancer and parents of ‘well’ children). To test group differences, independent samples t-test was used. A significance level of p > .05 was applied across tests; however, due to multiple testing, a Bonferroni adjustment was made (p < .016).

Finally, a multiple hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between HAP and two key predictors: parental health anxiety and social support.

Linearity of all variables were assessed by partial regression plots and a plot of studentised residuals against the predicted values. Residuals were independent as assessed by a Durbin – Watson statistic of 2.309. There was homoscedasticity of residual equal for all values as assessed by visual inspection of a plot of studentised residuals versus unstandardised predicted values. There was no evidence of multi-collinearity, as assessed by tolerance values greater than 0.1. The assumption of normality was met, as assessed by Q-Q plots. For the regression analysis, the enter method was used, with one variable per block. The control variable ‘level of involvement with child’ was in the first block, followed by health status of the child (i.e. group), then social support, and finally, health anxiety.

Level of involvement with child was controlled for a priori due to the literature supporting involvement with child as a core factor in mental health and wellbeing of parent and child (Li and Guo, Reference Li and Guo2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fan, Shang, Li, He, Cao and Ding2024; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Scheiber, Laughlin and Demir-Lira2025; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Hallingberg, Eriksson, Ng, Hamrik, Kopcakova, Movsesyan, Melkumova, Abdrakhmanova and Badura2022). This served to isolate the relative contribution of this variable, to allow interpretation of the full effects of the variables of interest as they are added in sequence.

Results

Sample characteristics

Figure 1 highlights the different stages of recruitment and details about the final sample; of the 176 who made initial contact, 120 were included in the final sample (68.1%).

Figure 1. CONSORT style diagram reporting included and excluded participants.

To summarise, 31.7% of parents of children with cancer were fathers, 92.7% identified as white, 78% were married, 19.5% cared full-time for their child, 63.4% identified as the primary caregiver, 48.8% were in full-time paid work, and 43.9% had education up to a degree (BSc) level; 66.67% of parents disclosed no physical or mental health problems. Regarding the children as reported by parents, 61% were male, 48.8% had leukaemia, 34% were in active treatment and 46.3% had received chemotherapy. The mean time since diagnosis was M=1.98 years (SD=2.833), ranging from 1 month to 12 years, and 51% were on a curable pathway. At least one life-threatening acute event for the child was reported by 46.8% of parents.

For the group of parents with ‘well’ children: 21.5% were fathers, 93.7% identified as white, 62% were married, 48.1% identified as primary caregivers, 50.6% were in full-time paid work, and 27.3% had formal qualifications up to postgraduate level; 38.5% of the children considered were reported as male.

This study asked participants to self-identify their gender. As there were only two respondents who identified outside of male and female, it was not possible to do further meaningful analyses on this group, and the data from these cases were withdrawn.

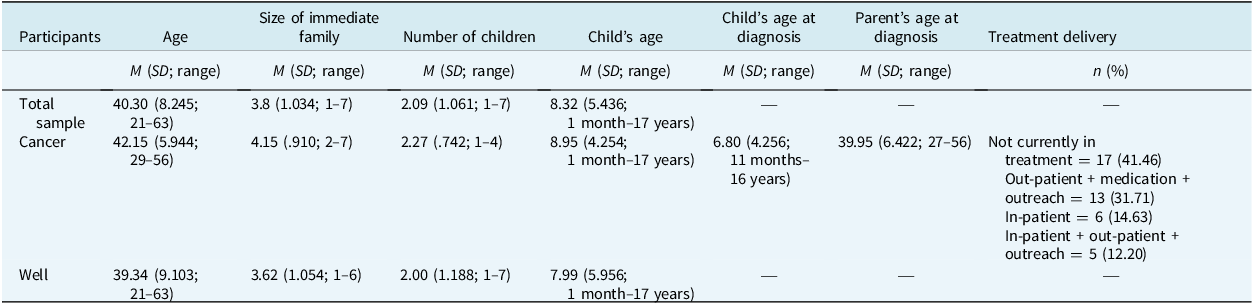

Table 1 includes additional participant information for the total sample and both groups (‘cancer’ and ‘well’).

Table 1. Additional participant information for the total sample and both groups

M, mean; SD, standard deviation; N=120 (n=41 cancer, n=79 well).

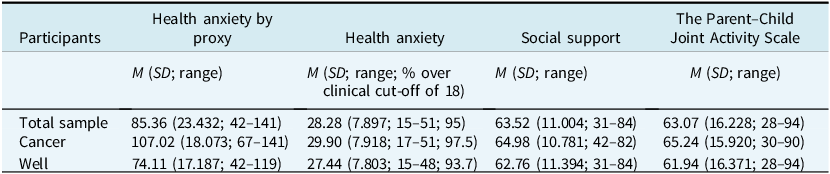

Table 2 shows the questionnaire scores for the total sample and the two groups: parents of children with cancer and parents of ‘well’ children. The HAP scores were higher for parents of children with cancer, but there was lower variance between the two groups of parents. HAP scores were significantly higher for parents of children with cancer than for parents of well children (p < .05), with HAP significantly associated with parent’s own HA (p < .05), as would be expected.

Table 2. Questionnaire scores for the total sample and both groups

M, mean; SD, standard deviation; N=120 (n=41 cancer, n=79 well).

The results are reported in relation to each research question, for clarity:

-

(1) Are parental health anxiety, social support and involvement with child associated with HAP in parents of children with cancer and with parents of ‘well’ children?

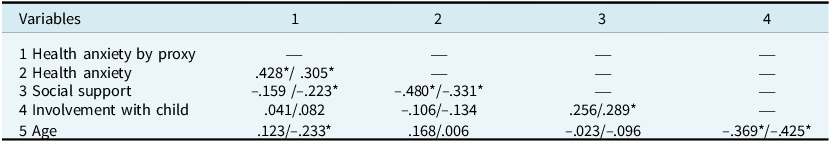

A Pearson’s correlation conducted between HAP and other study variables is reported separately for each group in Table 3. Analysis reflected HA was significantly positively correlated with HAP in parents of children with cancer (r 41=.428, p < 0.05) and parents of well children (r 79=.305, p < .005). Social support was not significantly associated with HAP in parents of children with cancer (r 41=–.159, p > 0.05) but was in parents with well children (r 79=–.223, p < 0.05). Level of involvement was not significantly correlated with HAP in either group. Findings reflected that while parental health anxiety is associated with higher HAP scores, social support does not show a direct linear association with HAP in either group.

-

(2) Are there significant between-group differences in relation to HAP when considering gender, child health status and role of caregiver?

Table 3. Correlations between study variables

Parents of children with cancer/parents of ‘well’ children. *Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed).

A series of independent-sample t-tests were run, with a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level of .016 per test (.05/3) to reduce the risk of a type 2 error. Adjustment reflected no change in significance levels for reported tests. The only group with a statistically significant difference was the health status of the child, p < .001. HAP scores for parents of children with cancer (M=107.02, SD=18.073) were higher than parents of ‘well’ children (M=74.11, SD=17.187), a statistically significant difference (M=32.910, 95% CI [26.243 to 39.578], t 118=9.775, p < .001). HAP scores for males (M=84.53, SD=24.575) were lower than for females (M=85.34, SD=23.134), but no statistically significant differences were evident (M=–.804, 95% CI [–10.629 to 9.021], t 117=–.162, p=.872). HAP scores for primary caregivers (M=87.45, SD=24.700) were higher than for those who were not primary caregivers (M=82.96, SD=21.868), but differences were not statistically significant (M=4.489, 95% CI [–3.998 to 12.976], t 118=1.047, p=.297).

-

(3) To what degree (if at all) do these identified factors of interest (gender, social support, health anxiety, health and caregiver status) account for the variation in HAP in parents of children with cancer and children who are ‘well’?

Tests of association between demographic variables found no significant associations with the primary outcome variable (p > .05). Stage of the cancer journey (F 34,6=1.171, p=.462) and active treatment status (yes/no) (z=–0.68, p=.495) were also not significantly associated with HAP. Therefore, no further demographic variables were controlled in the regression analysis, except a priori, ‘level of involvement’.

Hierarchical multiple regression assessed the relative contribution of key predictor variables on HAP, the criterion variable, using enter method and the planned sequence of entry (i.e. involvement with child, health status of the child/group, social support, HA). When health status of child (children with cancer and ‘well’ children) was added to the regression in block 4, a significant effect was seen (R 2=.450, F 2,117=47.855, p < .001; adjusted R 2=.441), accounting for 44% of the variance in HAP. When social support was added to the regression, there was a change from the previous block with R 2 change of .029, R 2=.466, F 3,116=35.551, p=.012.

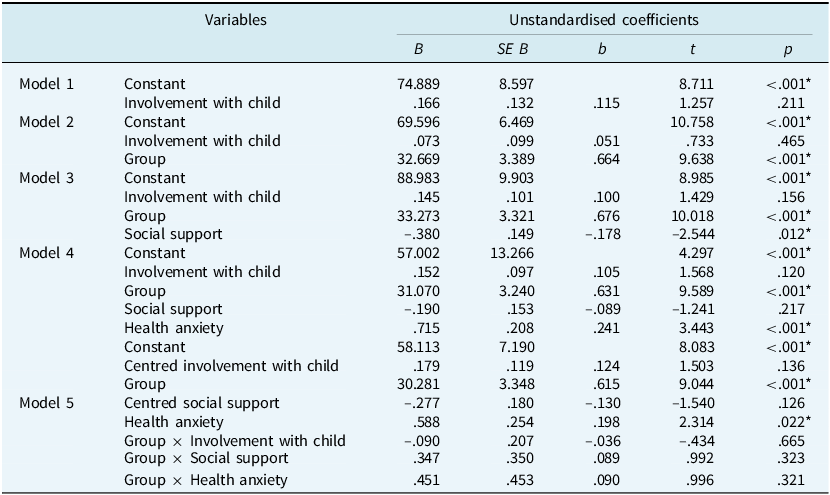

The full final model (Table 4) included involvement with the child as the control variable and group, social support and HA as predictor variables, added in blocks sequentially and HAP as the criterion variable.

Table 4. Hierarchical regression

* Significant findings at the .05 level.

All variables of interest (group, social support, HA) were independently statistically significant, accounting for 51% of the variance, when controlling for level of involvement (R 2=.528, F 4,115=32.121, p < .001; adjusted R 2=.511). Parents of a child with cancer had on average a 31-point higher HAP score than parents of a ‘well’ child. Parents with a 1-point higher HA score will have on average a 0.7-point higher HAP score, providing all other variables are equal.

It was agreed that it would be beneficial to understand more about the relationships among the variables on HAP, and specifically whether having a child with cancer influenced other variables’ scores. Therefore, further analytical steps were taken to identify the influence of group membership: interaction terms (involvement with the child, social support and HA) were added to the regression model to assess whether the effect of any predictor might differ between the two groups. Adding interactions directly into the model would inflate relationships, risking collinearity due to the correlation between variables. The variables were ‘centred’ to reduce the risk of mathematical collinearity in the expanded model. Variables were added to the model in one block. Once centred, the new full model (model five) – including centred involvement with the child, group, HA, centred social support, and interactions between group and each of the three predictors – involvement with the child, group, HA, and centred social support to predict HAP, was statistically significant with R 2=.534, F 7,112=18.319, p < .001; adjusted R 2=.505.

In model five, HA was significantly associated with HAP (p=.022), while holding all other model variables constant. Analysis indicated that after controlling for HA involvement with the child and social support, parents of children with cancer were more likely to have higher HAP scores than parents of ‘well’ children (p < .001), the estimated mean difference being 30.3 points (SE=3.35, 95% CI [23.6 to 37.0]). As interaction terms were introduced, HA and group remained significant, with only slight changes to their associated coefficients. Social support and involvement with the child were not significant predictors in the final fifth model. Notably, once HA was added in, the previously observed effect of social support became non-significant, which is likely due to the shared variance explained by the moderate significant association between these two factors.

These findings suggest that HA is a stronger predictor of HAP than social support. The group differences in the associations between HAP, HA and social support (see Table 3), indicate that, particularly in parents of ‘well’ children, social support may influence HAP indirectly through the relationship with HA. Once HA is entered into the model, it acts as a confounder between social support and HAP, reducing the direct association between social support and HAP.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore HAP in parents of children with cancer and to compare these findings with parents of children who are considered to be physically and psychologically ‘well’. Variables of interest accounted for over half of the variance in HAP, offering insight into both groups of parents, establishing difference, relative contribution of key factors and how childhood illness impacts the family in a way that is clinically distressing to the parents.

For both groups of parents, HAP was significantly associated with health anxiety about themselves. This might be expected when we consider the current dominant model of HA, the empirically grounded cognitive behavioural model of HA (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Warwick and Deale2003) whereby thoughts about illness, meaning making and behavioural responses to illness are key in the maintenance of self-focused HA. Therefore, if the individual is a parent or caregiver, this then may also include those closest to them. This warrants further investigation. The presence of cancer is unlikely to independently ‘cause’ HAP, but it is possible that an underlying vulnerability or history of anxiety may be displaced into monitoring and managing the child’s health problem; investigating anxiety prior to the child’s diagnosis of cancer would highlight whether this is the case. In this instance, the child’s ongoing illness may act as a persistent stimulus and trigger for HAP. A recent paper by Haig-Ferguson et al. (Reference Haig-Ferguson, Cooper, Cartwright, Loades and Daniels2021) on intergenerational transmission of health anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic posited an interaction between parental cognitions and behaviours and childhood health related anxiety, suggesting that parental health anxiety could create a reciprocal maintenance of health anxiety. Findings from Daniels and Rettie (Reference Daniels and Rettie2022) highlighted that 51% of participants shielding a person with clinical vulnerability to COVID-19 reported clinical levels of health anxiety about the person they were shielding, providing further evidence of excessive caregiver concern when exposed to illness in a close family member.

We do not suggest this is a causal factor, as it is outwith the scope of this study to assess direction, causality and mechanisms, but more that if an individual already has a history of health anxiety, they may be more likely for these health concerns to expand to those in their immediate circle, as reflected in studies on shielding (Daniels and Rettie, Reference Daniels and Rettie2022). The relationship is complex, as we point out, and there is much to do in this field. Our results suggest that this is more likely in those who are parents to persistently unwell children, with parents of children with cancer in this study reporting greater worries about their child’s health than parents of children who did not have cancer. This finding is consistent with the expectation that having a child with cancer will bring additional concerns (McElderry et al., Reference McElderry, Mueller, Garcia, Carroll and Bennett2019). Indeed, higher levels of HAP were identified in parents of children with cancer when compared with parents of ‘well’ children when all other variables were kept constant, indicating that a child’s health status is likely to influence levels of HAP in parents. However, while accounting for around half of the variance in HAP is substantial, this also reflects that there are other factors unaccounted for that may help us to understand HAP better. For example, history of cancer in the family (including personal history; Albiani et al., Reference Albiani, McShane, Holter, Semotiuk, Aronson, Cohen and Hart2019; Bonadona et al., Reference Bonadona, Saltel, Desseigne, Mignotte, Saurin, Wang, Sinilnikova, Giraud, Freyer, Plauchu, Puisieux and Lasset2002), parenting style (Möller et al., Reference Möller, Majdandžić and Bögels2015) or general stress (Kubb and Foran, Reference Kubb and Foran2024) could all play a role in the degree to which a parent excessively worries about their child. Previous research findings reflect that parents of unwell children are more generally anxious than those of ‘well’ children due to increased burden and associated impacts on social, financial and emotional wellbeing as well as employment (van Oers et al., Reference van Oers, Haverman, Limperg, van Dijk-Lokkart, Maurice-Stam and Grootenhuis2014). Evidence reflects that health anxiety is more common in those with medical problems (Tyrer et al., Reference Tyrer, Cooper, Crawford, Dupont, Green, Murphy, Salkovskis, Smith, Wang, Bhogal, Keeling, Loebenberg, Seivewright, Walker, Cooper, Evered, Kings, Kramo, McNulty, Nagar, Reid, Sanatinia, Sinclair, Trevor, Watson and Tyrer2011). The same underlying mechanisms in terms of vulnerability and responses to illness may be at play here. However, research into the relationship between a caregiver and their anxiety about someone close to them with medical problems is very much in its infancy. Further research to both replicate and elucidate this relationship is needed.

This research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic – a period marked by heightened public concern around health, which may have led to elevated levels of health anxiety across the general population. It is also plausible that individuals experiencing higher levels of anxiety were more inclined to engage with and respond to studies related to their concerns, potentially introducing a self-selection bias (Kaźmierczak et al., Reference Kaźmierczak, Zajenkowska, Rogoza, Jonason and Ścigała2023). Furthermore, parents may generally report higher levels of health anxiety compared with non-parents (Benassi et al., Reference Benassi, Vallone, Camia and Scorza2020; Simon and Nath, Reference Simon and Nath2004), a hypothesis that warrants future investigation. Replication of this study post-pandemic would help determine whether the observed levels of HAP were influenced by this unique contextual factor.

Social support was inversely related to HA among parents of children with cancer. This is of particular interest as previous research has indicated that feeling well supported and connected can reduce parental anxiety (Bayat et al., Reference Bayat, Erdem and Gül Kuzucu2008) and anxiety in adults with cancer (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Hadjistavropoulos and Sherry2012). It might be that experiencing health anxiety itself inhibits social activity, perhaps through avoidant safety behaviours intended to protect their children from exposure to additional illness (Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Warwick and Deale2003). However, we also know that parenting a child with an illness can be isolating for many reasons (Carlsson et al., Reference Carlsson, Kukkola, Ljungman, Hovén and von Essen2019), and that fear of judgement from other parents (Lemmen et al., Reference Lemmen, Mageto, Njuguna, Midiwo, Vik, Kaspers and Mostert2024) can also create a barrier to accessing social support. Given the likely confounding influence of HA of social support and HAP in the parents of well children, it is difficult to disentangle and draw a meaningful conclusion about the nature of the relationship between these variables. However, we can reasonably suggest that, in line with existing evidence, social support is an important factor while experiencing mental health difficulties (Harandi et al., Reference Harandi, Taghinasab and Nayeri2017), parenting a well child or otherwise.

It is clear that there is scope for further research and exploration of HAP, with the opportunity to develop or adapt existing evidence-based models such as those proposed by Salkovskis et al. (Reference Salkovskis, Warwick and Deale2003), Haig-Ferguson et al. (Reference Haig-Ferguson, Cooper, Cartwright, Loades and Daniels2021), and also most recently in a large-scale randomised controlled trial, self-guided online interventions with parents who experience high levels of anxiety (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Alvarez, Arbon, Bremner, Elsby-Pearson, Emsley, Jones, Lawrence, Lester, Morson, Simner, Thomson and Cartwright-Hatton2024). What should be noted in all these cases is the crucial role of parental mental health in an unwell child’s life, and conversely the importance of parenting responsibility when working with individuals with anxiety. Adapting interventions to account for biopsychosocial factors is also particularly relevant (Abramowitz and Braddock, Reference Abramowitz and Braddock2008). However, this is an emerging field requiring replication and extension of existing findings in order to support advancement of clinical models.

Strengths and limitations

This study consulted parents of children with cancer to shape the research throughout, ensuring face validity and relevance of the study. The use of a control group strengthens the study, taking steps towards isolating the effects of HAP and placing findings in context. This offers a more robust foundation to support future development in the field. Despite active efforts to recruit a broad sample, the sample size was modest, including fewer fathers, and consisted mainly of married, educated white women, therefore the comparison of male/female caregivers was not possible. All participant data not identifying as male or female was withdrawn due to low response rate within non-male/female categories. Future research should seek to specifically include those from all gender categories to ensure that all parent voices are represented. More diverse samples representative of the general population are needed in order to answer questions about the role of men and those from ethnically diverse groups in their parenting roles. While this study grouped cancers under an umbrella term, further investigation of different cancer groups would provide increased understanding of factors impacting HAP. However, these limitations do not undermine the findings of the study.

Future directions

As the construct of HAP is relatively new, there are many avenues worthy of exploration. This might initially include establishing that this is not a phenomenon restricted to the field of oncology, with future research focusing on replicating findings and building in other clinical populations. Furthermore, the type of illness – which impacts both the prognosis and the nature of disease – is likely to place a crucial role in HAP and should be explored in more detail in chronic and episodic conditions to assess whether the relationships identified here remain intact.

In addition, it is important to understand how HAP is expressed, particularly in relation to cognitive and behavioural components. Investigating constructs such as catastrophic thinking, rumination and behavioural patterns such as reassurance seeking and how they present in HAP, and how this aligns with the model of HA would advance our understanding and potential treatment implication and may offer empirical data to support the parent – child reciprocal mode of HA proposed by Haig-Ferguson et al. (Reference Haig-Ferguson, Cooper, Cartwright, Loades and Daniels2021). This too offers a framework for investigating the dynamic interplay between parent and child factors.

Several elements of the parent – child relationship remain under-explored. For instance, it is still unclear how a parent’s health anxiety may influence a child’s own health-related beliefs, emotional responses, or behaviours, and conversely, how a child’s health status or level of emotional expression may reinforce parental anxiety. The potential for reciprocal reinforcement – where parental concern increases child distress, which then reinforces the parent’s worry – requires further empirical investigation. Attachment style, parental modelling of health behaviours, family communication patterns, and the child’s temperament or resilience may all moderate or mediate this dynamic. These factors are important to explore not only for theoretical refinement but also for informing targeted interventions.

Future work in these areas would enhance the literature by offering a deeper understanding of HAP, moving beyond a narrow focus on child illness and towards a broader understanding of the psychological, relational and contextual factors that contribute to parental anxiety.

As discussed, it is evident that there are factors not measured in this study which would explain at least as much of the variance as we have explained through the data collected in this study. We have speculated what these might be, and future work should look to allied fields such as HA in children and adults, and intergenerational transmission of anxiety, to consider what factors might be important to explore further.

Conclusions

Parents of children with cancer have higher rates of HAP (but not parental HA) than parents of ‘well’ children, with high rates of HAP associated with lower levels of social support in both groups. Health anxiety over parents’ own health and the health status of their child are key factors in understanding HAP, which is an important step to understanding additional considerations in the understanding of the challenges that both parents of children with illness and the children themselves face during these critical life events. However, further research is needed to replicate findings and further elucidate the mechanisms of maintenance and impact on the child of parental health anxiety.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.D., upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant privacy and consent.

Author contributions

Francesca Cocks: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Software (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (equal); Cara Davis: Supervision (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Charlotte Peters: Resources (equal), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Rita De Nicola: Resources (supporting), Writing - review & editing (supporting); Jo Daniels: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Supervision (lead), Writing - original draft (supporting), Writing - review & editing (lead).

Financial support

This was work completed as part of the requirements of a Doctorate in Clinical Psychology thesis. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Bath ethics committee (PREC reference number: 22-129) and NHS ethics (IRAS number: 301753). Approval was also gained from the Participant Identification Centre (PiC) site (Paediatric Oncology department within an NHS trust). Any necessary informed consent to participate and for the results to be published has been obtained. The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.