INTRODUCTION

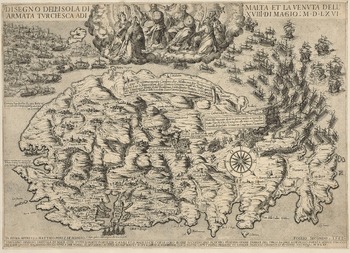

Rome, late spring, 1565. French-born engraver Nicolas Béatrizet (fl. 1540–65) publishes a map of Malta—hinge point of the Mediterranean, base of the Knights of Saint John—on the eve of conflict (fig. 1).Footnote 1 The onset, scope, nature, duration, and outcome of that conflict remain to be seen, but there is little doubt that it is imminent. Word has been leaking out of Constantinople for months about the preparation of a great Ottoman fleet, and most recently about its departure for an unspecified destination. Speculation swirls regarding the target, but Malta, long in the Ottoman crosshairs, appears most likely.Footnote 2

Figure 1. Nicolas Béatrizet. Melita nunc Malta, Rome, 1565. Etching and engraving, 40 x 30.5 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

As late winter of 1565 becomes spring—siege season—many observers in Europe monitor the situation uneasily. Malta might lie along a distant, amorphous frontier, but it is also a threshold, an opening to the possibility of conquest. Renaissance Europe is a fractured, disparate place, with inner conflicts, shifting contours, and little sense of common purpose or identity. But when it comes to the Ottoman threat, there is (mostly) unity, arising from shared fear.Footnote 3 That fear, in April and May 1565, is fixated on this small island between Sicily and Tunisia.

Béatrizet's map emerges from this anxious moment. Oriented with north at upper left, it shows not the whole of Malta, but rather one small section of it: the main deepwater port on its east side shaped by three jutting promontories. The central, vertical one is Mount Sceberras, with the island's main fortification, Fort St. Elmo, at its end. That peninsula divides the harbor into two sides: Marsamxett (then known as Marsamuscetto) at left, and the larger Grand Harbor at right. Extending horizontally toward Sceberras from the right is densely inhabited Birgu, with another fort, St. Angelo, at its tip. Below and parallel to Birgu is Senglea with its windmills, protected by Fort St. Michael. Outside the harbor, ships of all shapes and sizes denote the seafaring might and vigilance of the Knights of Saint John. The central ship, just below the title, Melita nunc Malta (Melita, now [known as] Malta), flies the flag of the order—bearing its signature equal-armed cross with flared, swallowtail ends. The text of the map conveys the same general message that this place is “powerfully defended by its knights against the attacks of its barbarian enemies,” together with basic information about the island's size and position.Footnote 4

Béatrizet's map does not depict any specific military engagement. In it, there are no troops visible on Malta's shores, but there are subtle signs of watchful waiting, and of readiness. Béatrizet portrays guns and cannon radiating from Fort St. Elmo, and firepower at the ready at the other forts, too. He records military preparations that other sources confirm to have been in place. A protective trench appears to the east of Birgu and Senglea, while new ramparts extend across their outward-facing shorelines. Two chains have been stretched across the inlet to prevent enemy vessels from entering. That inhabited sector and headquarters of the Knights of Saint John has been sealed off. The meaning is clear: Malta is ready to repel any offensive.

Béatrizet and his audience understood that something was coming. That something, it turns out, was the Great Siege of Malta: one of the most vaunted military confrontations of the early modern era, between the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe.Footnote 5 Béatrizet's map was the prelude for a series of hastily printed maps that documented the siege's every triumph and reversal over sixteen long weeks. Produced in the heat of the moment, these news maps were part of a media event unprecedented in the sheer quantity and scope of materials produced, all of which sought to sway public perceptions of the episode and to keep Europeans on the edge of their proverbial seats the whole time.Footnote 6

Béatrizet's map was not the first of its kind. Rather, it was one of a host of similarly conceived news maps that had begun to appear in earnest three decades earlier, and it exemplifies many typical features. These works depicted current events in their geographic context, reporting history as it unfolded. Originating in Italy or Northern Europe, they tended to be woodcuts or combinations of engraving and etching, printed on single sheets of paper. They were usually separately published, although occasionally they were combined with written news pamphlets, and many were subsequently copied for incorporation into books of town views, or bound into composite atlases assembled by individual collectors. In news maps, the cartographic stage is the foremost element, depicted in relatively accurate, if sometimes schematic, plan or aerial view. They are invariably adorned with signs of military operations, such as stick-figure infantry, forts, small pictograms of encampments, or galleys and other vessels when the site is a port. Actual fighting is rare, but does sometimes make an appearance. Most maps include text, but rarely more than a few terse lines glossing the events depicted. Finally, and critically, they were issued during or shortly after the episode in question.

News maps occasionally depicted non-military episodes, like natural disasters, but the vast majority revolved around war—which was, after all, a near-constant state of affairs in early modern Europe, with military technology in the midst of rapid change.Footnote 7 Armed conflict, in turn, catalyzed cartographic development, spurring advances in surveying as well as in measured representation.Footnote 8 As R. V. Tooley recognized nearly a century ago, almost all the earliest engraved maps of towns and cities were linked to military events.Footnote 9 Early production of news maps was driven primarily by increasingly frequent Ottoman forays into the western Mediterranean and Central Europe—incursions that signaled the imperial ambitions of Sultan Suleiman the Great (r. 1520–66).Footnote 10 But these works lent themselves just as well to intra-European skirmishes like the Italian Wars, fought between the Habsburgs and the Valois kings of France, or, later, the Thirty Years’ War, between the Habsburgs and the Dutch Republic.

News maps conveyed concrete information about geography and tactical maneuvers together with abstract ideas about expansionism and conquest. It would be reasonable to assume that they played a key role in shaping public views about conflict and external threat, although evidence for consumption is frustratingly slim, and demand must be extrapolated from what is known of supply.Footnote 11 Based on surveys and reports from the battlefield, news maps were published by the hundreds, even the thousands—practically mass produced by early modern standards—their content updated frequently to keep pace with the latest developments.Footnote 12 Yet they have garnered little recognition as a genre. A handful of studies have addressed examples related to given conflicts, or produced by specific individuals.Footnote 13 For the most part, however, news maps have been subsumed into the larger category of printed maps, as if their representation of topical events were incidental to their cartography, or as if they were prompted by the same motivations as their purely geographic counterparts.Footnote 14 Within the increasingly abundant scholarship on printed cartography, moreover, they have been overshadowed by larger, more spectacular or rare items.

A basic aim of this article is to begin to give this distinct corpus the attention it demands. Another is to establish the place of news maps in the larger spectrum of nascent journalistic formats. A key early form of the news, they have been neglected by media historians, who tend to focus instead on textual ancestors of the serial newspaper.Footnote 15 By foregrounding the role of news maps among reporting platforms during this formative period, I seek to give a fuller picture of early modern news culture. The emerging media landscape of the sixteenth century was highly pluralistic and experimental, going well beyond the written word. In this context, the far-reaching role of the visual in general has been overlooked.

My case study will be a small selection of the roughly fifty news maps that European publishers hastened to make public over the course of the four-month Great Siege of Malta, which became a laboratory for the genre's development. To that end, I will rely, in part, on the authoritative catalogue raisonné of Albert Ganado and Maurice Agius-Vadalà, published in 1994. The authors’ goal in that compendium was to assemble a comprehensive repertoire of maps relating to the siege and of the known facts about them. It was not, however, to assess the larger history and cultural implications of news maps in general. Ganado and Agius-Vadalà's corpus, therefore, serves as a building block for my own analysis into the patterns, mechanisms, and representational strategies of this cartographic genre, and for my alignment of it with the rapidly evolving news culture of the sixteenth century. This analysis is facilitated by additional knowledge gleaned from examining scores of news maps in archives and libraries in Europe and the United States, and further enriched by art historical methods of visual analysis.Footnote 16

No other event of the sixteenth century spawned such a large number of news maps. Those relating to Malta thus present a unique opportunity, for they were emblematic of the genre as a whole. Every representational tactic and strategy is on display in the maps that were produced in the summer of 1565—every advantage and limitation of the format as a delivery system for fast-paced news. These works also disclose the common pattern by which such items came to influence grander art forms and other media, providing topographical sources to artists creating battle murals for halls of state. In such elite contexts, they were curated and repackaged as lasting memorials to military prowess. News maps were thereby transformed from the timely to the timeless—from the uncertain, unfolding now, to the heroic, immutable then. By putting news maps into focus, this article will provide new insight into how, where, and why information is deemed culturally relevant, travels, and becomes visual history.

SIEGE MAPS AND NEWS CULTURE IN THE DECADES BEFORE MALTA

In the sixteenth century, news consumption was escalating rapidly, thanks to several interrelated factors that favored transnational circulation.Footnote 17 The print industry, with its ability to multiply and disseminate word and image, had expanded dramatically from its origins the previous century, as had public hunger to know about world events as they were happening.Footnote 18 At the same time, the growth of postal networks throughout Europe and beyond meant that printed information could travel farther, wider, and faster than ever before.Footnote 19 Most surviving news maps of the siege of Malta originated in Rome and Venice, then spread quickly to other centers throughout Europe, where they were copied and translated.Footnote 20 At that point they were transmitted to readers eager for the most recent updates, and in all likelihood—like other news formats—sold, posted, discussed, and digested in public squares and taverns.Footnote 21

News maps operated in something approximating the modern notion of real time. Of course, news did not reach the public instantaneously as it seems to today, in the age of the internet and twenty-four-hour news cycle. Ganado and Agius-Vadalà have estimated a time lag of at least three or four weeks before a news map relating to an event in Malta appeared on the market in the major publishing centers of Venice or Rome.Footnote 22 The news required some travel time, then there was further delay as a plate was designed, engraved, and printed—a little bit less if an existing plate just needed reworking. Sometimes new information arrived while a plate was being prepared, and it had to be altered to account for the update. Béatrizet's undated map exemplifies a typical interval. It depicts Malta awaiting its fate in April or early May of 1565, but is thought to have been published, in Rome, in early June.Footnote 23 Meanwhile, in Malta, four hundred miles away, the event that would come to be known as the Great Siege had been underway for several weeks. But—like the light shining from a distant supernova—what looks current depends on where you are standing. What is key is that the news was perceived to be consumed almost as it happened.

News maps were one facet of a growing constellation of reporting platforms, including avvisi (relatively short reports that could be secret or public, print or manuscript), printed folding pamphlets, and larger printed broadsheets—items with which they were sometimes combined, and from which they frequently drew information.Footnote 24 That said, typical news maps stood above and apart from the disposable paper culture that tends to be associated with other proto-journalistic formats, both in terms of their presumed audience and their physical properties. While there is little direct evidence regarding the consumers of these works, certain of their characteristics point to a well-educated and cosmopolitan group—not a truly popular audience, per se. As will be discussed, news maps tended to provide incomplete accounts of hostilities, meaning viewers had to collate them with outside written sources. The process of interpretation was therefore complex and discriminating—most suitable for readers already well versed in international affairs. Cartographic literacy, moreover, was restricted to a fairly elite demographic. Printed maps might have been a public-facing platform, but they were still a specialized form of representation, their conventions familiar mainly to sophisticated viewers.

Beyond this highbrow readership, the material properties of news maps suggest that their producers conceived of them as more than ephemera. On the one hand, news maps produced during the Great Siege—like their brethren from other key moments of the sixteenth century—were not particularly grand or breathtaking. In this sense they differ from a separate, related category of siege view that was intended to commemorate a victory—usually large, glorious woodcuts, meant for display.Footnote 25 Such works were also retrospective. Rather than spreading the news, they framed a certain, partisan version of recent history. By contrast, news maps were made in haste, not lovingly over time and with the benefit of hindsight. This does not mean they were neutral, for they too were mediated through a lens of cultural bias. Like all early modern reporting formats, news maps predated the very concept of journalistic objectivity. That said, the messages of news maps were less orchestrated and overt, their production more haphazard than their larger, celebratory brethren. Decorative flourishes, as well as factors like quality of paper, ink, and engraving, were secondary to freshness of information. A map published by Antonio Lafreri (ca. 1512–77) in August explicitly states as much, for the cartouche includes the following caveat: “And, if the whole [map] is not as polished as one would expect, this is due to the turbulent circumstances which do not allow those who are in Malta (who have sent the drawing) to carry out their work with the ease that is required. And what is being done [for the sake of publishing this map quickly], is done in order to keep refined minds continuously provided with the latest news.”Footnote 26 Clearly, makers of news maps prioritized timeliness over production values.

On the other hand, many sixteenth-century news maps did attain a level of quality sufficient to suggest that a more enduring value was built in from the very start. They do not just survive by accident, even if attrition is an important factor to consider, as it is to a greater or lesser extent with all premodern works on paper.Footnote 27 Most of these works were designed with an eye to aesthetic features—after all, if such aspects had been discounted completely, Lafreri would not have felt compelled to make his excuses—and they were skillfully engraved, often by printmakers who also specialized in other kinds of imagery.Footnote 28 Their dimensions, moreover, tend to be larger than strictly necessary to effectively convey their information. One can assume that their prices followed suit, although explicit evidence in that regard is scant.Footnote 29 Similarly, news maps were occasionally adorned with color to enhance visual appeal—not, say, to clarify topography and battle formations. Where they sometimes fell short, even by the standards of their own time, was in perpetuating mistaken, misleading, or patently false information about the event represented, though this did not stop them from being collected. Indeed, most extant examples survive precisely because they were bound into albums by later collectors seeking to create personalized, pastiche histories.Footnote 30 In sum, news maps should not be considered a visual form of cheap, disposable broadsheet. In the history of news, they embody a liminal, neither-here-nor-there quality, between fleeting and ongoing relevance, popular and privileged imagery.

Malta was a turning point in the history of news maps and of news coverage generally, inviting a great deal of international scrutiny. To be sure, the Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1529 had commanded its fair share of attention, but less ink had been spilled on that otherwise comparable threat to Western Christian civilization. The news pamphlets issued in the midst of that episode—which did not last as long but was similarly followed by an unlikely victory—were numerous, but their numbers were surpassed by materials relating to Malta.Footnote 31 The Great Siege of Vienna was also commemorated in printed imagery, most famously the magnificent, six-sheet circular woodcut view published in Nuremberg by Nicolaus Meldemann (d. 1552) shortly after the event (fig. 2).Footnote 32 That view is one of a handful of the earliest elaborate woodcuts depicting site-specific sieges and battles, which balanced panegyric and documentation.Footnote 33 These were relatively costly luxury items, aimed at a privileged class of collector.Footnote 34 Often sponsored by rulers or civic bodies, they were undeniably ideological. Meldemann's view, for example, was commissioned by Nuremberg's city council as a gift for Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (r. 1519–56), and as a statement of imperial support.Footnote 35 News maps, by contrast, were smaller, more modest, aimed at an open market, and available to a wider spectrum of consumers.

Figure 2. Nicolaus Meldemann. Circular view of Vienna, 1530. Woodcut, 81 x 85.5 cm. Sammlung Wien Museum, 48068, CC0.

They were also, for the most part, a slightly later phenomenon—although it is entirely possible that scattered examples produced in the 1520s have not yet come to light or have since perished. It is telling, however, that not a single news map of the Great Siege of Vienna is known today. News maps as a genre seem to have taken flight in the 1530s, subsequent to Vienna, possibly in response to a perceived lack of geospatial information in coverage of that event. Likely originating in the North—although there is insufficient evidence to say for certain—they quickly spread throughout Europe, following the same international trade circuits as other news forms.Footnote 36 Early innovators in the realm of news-map production include Sebald Beham (1500–50), Jörg Breu the Elder (ca. 1475–1537), and others in the North, as well as Agostino Veneziano (ca. 1490–1540), Antonio Salamanca (1478–1562), and Enea Vico (1523–67) in Rome. These figures recognized a business opportunity when they saw one. Tullio Bulgarelli has noted an uptick in printed avvisi beginning in the 1520s, while Andrew Pettegree has observed that news culture in general surged in the mid-1500s, spurred by the Italian Wars and the Turkish threat.Footnote 37 The rise of news maps fits perfectly within that time frame.Footnote 38 The pace of production increased steadily in the late 1530s and 1540s, tracking events in the Third Ottoman-Venetian War, the Italian War of 1542–46, and other conflicts. The genre continued to build greater momentum in the 1550s with ongoing episodes in the Ottoman-Venetian and Ottoman-Habsburg Wars and the Last Italian War of 1551–59, not to mention the Schmalkaldic War and Wars of Religion.Footnote 39 Wartime is not usually good for the arts, but it proved fertile indeed for news maps. By the time the Siege of Malta was on the horizon, they had crystallized into a distinct genre that took its place within the larger array of early modern journalistic forms.

THE GREAT SIEGE: THE HEAT OF THE MOMENT

During the tense lead-up to the siege of Malta, there was a lot of behind-the-scenes action before any information became public. Since 1530, this strategically placed, frequently contested island had been in the hands of the Knights Hospitaller, who had occupied it shortly after being routed from their previous island stronghold at Rhodes, in 1522.Footnote 40 In the late 1550s and 1560s, the Knights of Saint John were under the able leadership of Grand Master Jean de Valette (1494–1568). In fall of 1564, he began to hear the rumors from Constantinople, and his powerful ally, the papacy, received similar intelligence. The Venetian Republic was on good terms with its Ottoman trading partners, and their ambassador in Constantinople was also keenly aware of the developing situation.

The news did not come out of the blue. European rulers had long anticipated a Turkish assault on Malta. In fact, the Ottoman fleet commander Sinan Pasha (d. 1553) had raided the island in 1551, but he had been unable to take Birgu or the inland capital of Mdina, so the effort had been diverted to Gozo, the second-largest island in the Maltese archipelago, and ultimately to Tripoli, on the North African coast.Footnote 41 In the wake of that event, the Knights of Saint John had strengthened Malta's fortifications, quickly building Fort St. Michael on Senglea and Fort St. Elmo on the Sceberras Peninsula to augment Fort St. Angelo at Birgu. To the Ottomans, Malta was an alluring target for a couple of reasons. First and foremost, it represented an ideal stepping stone for making inroads into Europe—from it, they would have a convenient base to invade Sicily, then the Kingdom of Naples and beyond. Second, the Knights of Saint John had long been in the sights of the sultans for their crusading zeal—their aggressions on Muslims, Ottoman trade routes and commerce in the Mediterranean, and Barbary corsairs.

In 1558, there had been another close call, when Malta was bypassed by Suleiman's forces en route to sacking the western coast of Italy, Corsica, and Minorca.Footnote 42 In response to the scare, de Valette had charged the Italian engineer Bartolomeo Genga (1518–58) to draw up the design for a new, massive fortification on Sceberras to protect Malta's harbor. Genga's manuscript plan of 1558 still exists—regrettably, for the Knights of Saint John, it remained on paper.Footnote 43 Its irrelevant contours are still visible on Béatrizet's map of 1565 (fig. 3), which he based on an earlier printed plan that had been intended to publicize Genga's idea.Footnote 44 Copying that model, Béatrizet outlined the same fortified enclave on the central promontory of the harbor, labeling it “Pianta di la nova cittade” (“plan of the new citadel”)—but then scratched it out, somewhat mystifyingly writing “ruinata” (“ruined”) beneath the caption.Footnote 45

Figure 3. Detail from figure 1: Nicolas Béatrizet. Melita nunc Malta.

Whatever their meaning, these modifications signal that the plate is not new but rather reworked. The most likely explanation is that Béatrizet had previously issued his own print touting Genga's design—a first state of the eve-of-siege map, of which no example has come to light—and then simply recycled that plate two years later to broadcast the siege preparations. This pattern is very common. Printmakers were resourceful: they copied existing models and reused their own materials whenever possible—practices that can lead to considerable confusion when it comes to assigning authorship and determining sequence. Arguably, however, the means by which news traveled is more interesting than who was first.

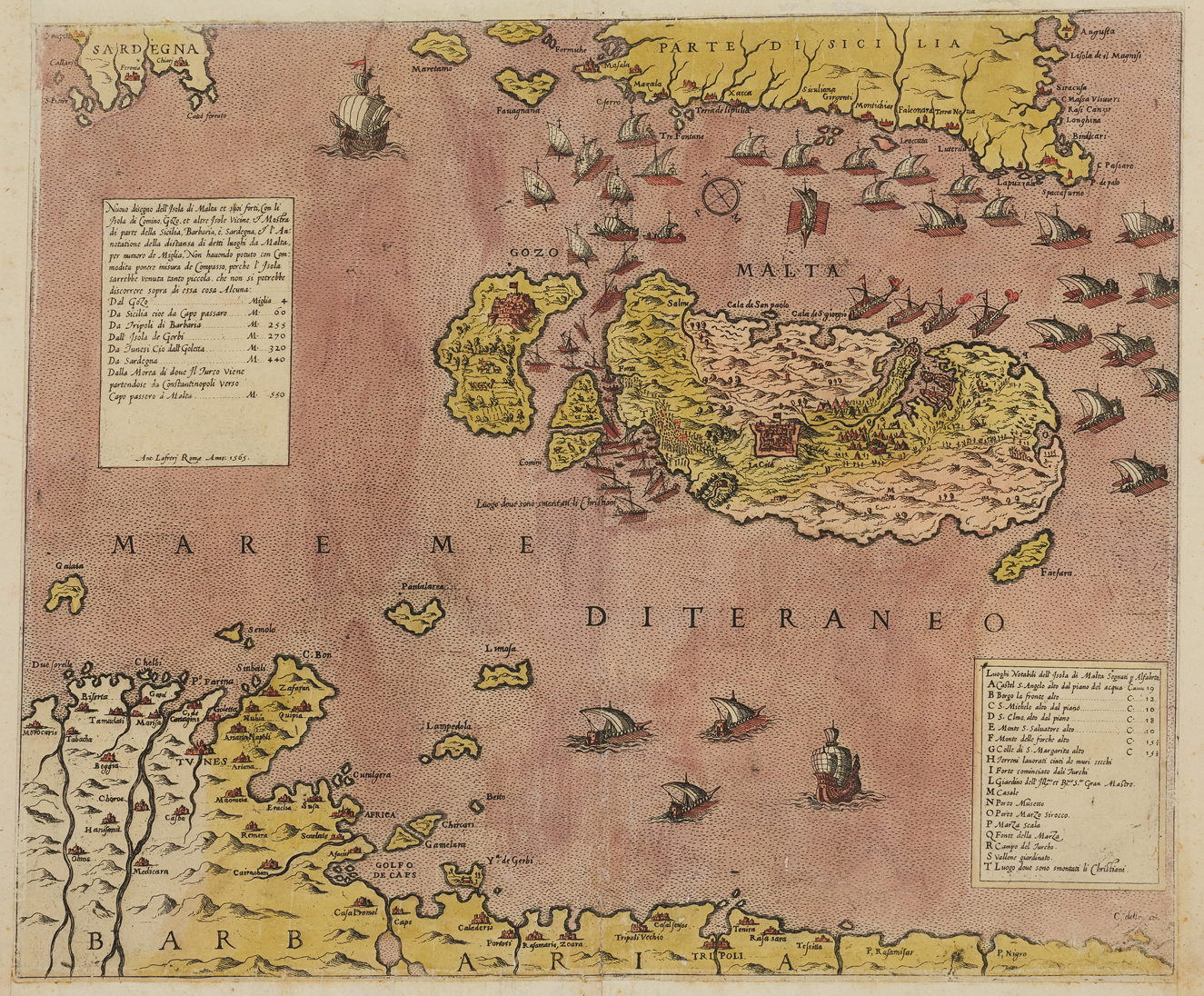

From the late 1550s, it was considered a matter of time before the Ottomans invade Malta. So when the alert was raised in spring of 1565, the Knights of Saint John were ready to mobilize. The Turkish fleet, consisting of almost 200 ships under the command of Piali Pasha (c. 1515–78), arrived on May 18, bringing a huge army. Contemporary estimates for the number of Turkish troops range from 20,000 to almost 40,000. Whatever the case, they vastly outnumbered the defending force of fewer than 6,000, composed of about 500 Knights of Saint John, 1,200 mercenaries, and some 4,000 locals.Footnote 46 A map of the whole island by Venetian printer Niccolò Nelli (fl. 1552–79) shows the scene on that fateful day in May (fig. 4).Footnote 47 Oriented with north at the bottom, it depicts Malta's coastline surrounded by several types of Ottoman vessels (so denoted by the conventional use of the crescent on their standard—a symbol the Turks did not yet widely use for themselves).Footnote 48 Their dispersal all around the shore might refer to the fact that the Ottomans had not been able to land right away, so their galleys had moved along the coastline before laying anchor, but from a visual standpoint it creates the appearance of an ominous stranglehold encircling the island.

Figure 4. Niccolò Nelli. Il vero ritratto de l'isola d’ Malta, Venice, 1565. Etching and engraving, 28 x 36.5 cm. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Nelli, like Béatrizet, was using an earlier map as a point of departure: Lafreri's influential fish-shaped plan of 1551 (fig. 5).Footnote 49 Ganado has compellingly argued that Lafreri, in turn, based that map on an official, confidential manuscript plan drawn up as a site study for the Knights of Saint John in the 1520s, as they were plotting their move to Malta after having been driven out of Rhodes.Footnote 50 Thanks to that privileged source, Lafreri's map is highly accurate and detailed, providing a wealth of detail about Malta's topography, network of roads, and place-names. Understandably, it became a prototype for many later representations. Nelli's map of 1565 copies Lafreri's model faithfully, the only real difference being his addition of the newsworthy tidbit: the arrival of the Ottoman fleet. Here another pattern emerges that is common to many news maps—namely, the contrast between freshness of military information and the age of the cartographic model. In this case, even the text is unchanged. Nelli repeats Lafreri's generic snippets about Malta's size, position, and history, as well as his concluding allusion to the uneasy climate in which he had published his plan: “The Holy Knights of the Order of Jerusalem now hold [Malta] with great glory against the investment of the Turks.”Footnote 51

Figure 5. Antonio Lafreri. Melita insula, Rome, 1551. Etching and engraving, 33 x 46.5 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

In Nelli's map, there is no amendment to Lafreri's original text to report the current situation and impending invasion. While it is true, in the most general sense, that the Knights of Saint John were still attempting to hold Malta “against the investment of the Turks,” Nelli offers precious little by way of textual guidance to the viewer. He might have intended to do so: his cartouche leaves extra blank space where additional detail might have been inserted, but was not. Indeed, the only signal that viewers are even looking at a specific fleet is the tiny crescent-bearing flags flying above some of the ships. The map's verbal and visual reticence was typical, again raising the point that the audience for such works must have been sufficiently informed to fill in the blanks.

The pace of events in Malta and of news maps reporting them accelerated quickly. It is possible to sketch a summary of the unfolding story and its cartographic representation through the evolution of a single plate that Nelli published in sequential states, each one following rapidly on the heels of the other.Footnote 52 As the first in the series demonstrates clearly, Nelli did not look to Lafreri's fish-shaped plan as a model for the cartographic stage of this plate, but rather to Béatrizet's eve-of-siege map, focusing on the same geographic area centered around Malta's main harbor, and sharing the same orientation, with north at upper left (fig. 6).Footnote 53

Figure 6. Niccolò Nelli. Il porto dell'isola di Malta, Venice, 1565 (state 1). Etching and engraving, V, 39 x 31 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

Nelli's map collapses a series of episodes from the first month of the siege. The Turks had first laid anchor about six miles away from the fortified port, in an undefended secondary harbor, Marsascirocco, on Malta's southeast coast. Departing from Béatrizet's model, Nelli takes some creative liberty to compress distances and squeeze in that harbor at lower right. The massive Turkish forces proceeded to move overland to pitch camp at Marsa, near the base of Sceberras, where Nelli accordingly portrays a number of pointed Ottoman tents along with other structures, as well as several large cannon, neatly ordered and, presumably, ready to fire. To their right, an adjoining enclosure at the base of Grand Harbor has been set up to store ammunition and other supplies. Meanwhile, in Grand Harbor, the defenders have eliminated one of the two massive chains, and moved the other so that it now seals the inlet dividing Birgu and Senglea.Footnote 54

The Ottomans made their primary target Fort St. Elmo on Sceberras, calculating that if they could take it, they could move their fleet into Marsamuscetto, a better position from which to turn their sights to Senglea and Birgu. Nelli shows the entirety of the Sceberras peninsula crammed with enemy guns and infantry below Fort St. Elmo, which is under heavy infantry assault—perhaps an allusion to the final Turkish push in mid- to late June after a month of intense fighting. Another line of artillery is trained on Senglea point from Corradino Heights, across the inlet to the south, gearing up for a secondary phase of hostilities. The map is dated July 8 but depicts events prior to June 23, when St. Elmo fell—although after having held on for a remarkably long time with a defending force of just 600. It was a victory in defeat, for it took the Turkish commanders much longer than expected to vanquish St. Elmo, under heavy casualties. Clearly, what the Ottomans (and perhaps their Christian adversaries) expected to be a rout was proving to be anything but.Footnote 55

The second map in the series—and the second known state of Nelli's plate—is dated August 4, but again shows the situation about a month earlier (fig. 7).Footnote 56 For this version, Nelli fixed a mistake that had appeared in the previous state: the inclusion, at lower left, of St. Paul's Bay (a cove actually located on the complete opposite side of the island, on its northeast coast). Also, realizing that he would likely have cause to issue multiple maps in August, Nelli cleverly saved himself the trouble of changing the engraved date by leaving a blank space before “Agosto” where he could insert the numerical date by hand. Here, as in other maps he issued in August, the number (in this case, “4”) is written in manually. Nelli, like other producers of news maps, used successive states of the plate to amend perceived flaws in earlier versions and to experiment with timesaving strategies, as well as to update the newsworthy information.

Figure 7. Niccolò Nelli. Il porto dell'isola di Malta, Venice, 1565 (state 2). Etching and engraving, 39.5 x 31 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

Mystifyingly, for a map dated August 4, St. Elmo is not depicted as having fallen—the Knights of Saint John's standard still flies above it—although that episode predates others that are portrayed here. Nelli seems to have been slower to amend information that required correcting the plate than he was to make additions. It was more labor intensive to remove or alter an engraved feature than simply to add new lines to blank space. The former operation required hammering the metal plate from behind, burnishing the surface, and then reengraving it to achieve the desired modification.Footnote 57 This toilsome process is one reason why early modern cartography was sometimes conservative, with errors and inaccuracies persisting long after better knowledge had come to light. The constraints of printmaking techniques worked against the medium's progressive side and its much-vaunted ability to disseminate information widely. Often, prints spread misinformation instead.

If Nelli created possible cause for confusion by leaving outdated episodes in place, he also made important additions that clarified the current situation. Most conspicuously, the Ottoman forces have now overrun the map's whole east (or right) side. A large array of Turkish firepower rings the forts at Senglea and Birgu, with new batteries turned toward them from the San Salvatore bank opposite and above Birgu, and from Bormla, inland at right, joining the ones that were already present on the east side of Sceberras and at Corradino Heights to the south. The besiegers have also set up a new camp east of the two promontories, in Bormla, at the map's far right, as well as a new field hospital for wounded Ottoman soldiers, visible just beneath it. Large, orderly infantry battalions are depicted throughout.

The map alludes to episodes both historical and apocryphal. At upper left, a label next to a small fleet explains that thirteen ships had come from Algiers bearing Ottoman reinforcements. Although the number of ships was closer to thirty, the episode was real: Nelli refers to the arrival of Hassan Pasha (ca. 1517–72), son of legendary admiral Hayrettin Barbarossa (d. 1546) and a high commander in his own right, from Algiers with almost thirty vessels and 2,500 men.Footnote 58 Separately, in Grand Harbor, between Fort St. Elmo on Sceberras and Fort St. Angelo on Birgu, a group of Ottoman vessels appears, alongside a caption describing how a number of Turks had tried to sneak their way into the fort on Birgu by dressing up as Christians, but they were beaten back and drowned. Whether this event is wholly spurious or contains a grain of truth is unclear—it does not correlate with events known from other sources—but rumors and fabrications frequently sneak their way into news maps.Footnote 59 At the same time, it is also worth noting that Nelli has begun to add more textual gloss to the visual information provided by his map.

Nelli issued the third state of the map just one day later, making a single, simple but substantial addition: the label “presa del forte” (“taking of the fort”) above Fort St. Elmo.Footnote 60 Had this momentous event just come to his attention in the space of the twenty-four hours separating this state of the map from the previous one? Perhaps, but Ganado and Agius-Vadalà have also speculated that Nelli might have been releasing information bit by bit, in a shrewd move calculated to sell more maps.Footnote 61 The engraver still did not bother to change the flag flying over the fort from the Knights of Saint John's cross to the Turkish crescent, however, or to remove the infantry assault swarming around it that had led to its fall. The text might signal the taking of St. Elmo, but the image suggests that the struggle goes on.

The fourth state of Nelli's map is dated August 12, one week later.Footnote 62 The only difference is the date—which, as it was handwritten, is not a change to the plate, and thus raises the issue as to whether this version should be considered a new state. It also raises the question of what Nelli intended to convey with those manually entered dates. Clearly they were not meant to signify the date of events represented in the map, or the date the plate was engraved (although both scenarios are possible in other dated news maps), but rather to indicate the date the map was run off the press, and/or sold. In the map of August 12, the date can also be understood to signify that the sheet contains the best and latest state of Nelli's knowledge—in other words, no new information had come to his attention between August 4 and 12.

Nelli's interventions were more pronounced for the fifth state of his map, which he did not bother to date beyond “Agosto,” but—factoring in the usual time lag and the fact that it seems to depict the situation in mid-July—the map probably originated around the middle of the month (fig. 8).Footnote 63 A key change is the appearance of Turkish galleys in Marsamuscetto to the left of the Sceberras Peninsula, their anchorage there a direct result of the taking of Fort St. Elmo. Now the Ottomans have a toehold in the harbor for mounting their offensive against the other two forts at Birgu and Senglea. Another development portrayed is the first sea assault on Senglea, which took place in early July. Ten Turkish vessels appear massed around the promontory's lower flank, taking fire from the defenders. The only description Nelli gives for the event is “barconi,” or “large boats,” but other sources relate that the Knights of Saint John—who had been forewarned of the attack—managed to fend it off decisively, sinking all ten of the attacking vessels and drowning everyone aboard.Footnote 64 Not pictured is a second, massive assault on Senglea by sea and land that followed on July 15—it too failed.Footnote 65 Meanwhile, on Nelli's map, corpses are piling up outside the Turkish field hospital at right.

Figure 8. Niccolò Nelli. Il porto dell'isola di Malta, Venice, 1565 (state 5). Etching and engraving, 39.5 x 31 cm. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021, RCIN 721037.

That map is the last known state of the Nelli series. It seems likely that others followed later, but none have yet come to light. Did collectors seek to acquire them as they came out, comparing consecutive versions to follow the latest changes in the developing hostilities? It is impossible to say with certainty, but it seems plausible, especially judging from the number of Italian composite atlases assembled by collectors that include multiple maps of Malta during the siege (whether collectors were loyal to any one publisher's versions, however, is doubtful: tastes seem to have been omnivorous).Footnote 66 By the end of the sequence delineated here, Nelli's serially reworked plate had become a digest of the most recent as well as the preceding events, a complicated tale to unravel indeed. Information has accumulated on the cartographic surface, a confusing palimpsest of attacks and retreats, victories and setbacks, past and current happenings.

Nelli was just one of many printers who catered to public demand for news from Malta. A map issued just after its conclusion by a rival in Rome, identified by Ganado and Agius-Vadalà as Palombi (perhaps Pietro Paolo Palumbo, fl. 1562–86), depicts the end of the siege (fig. 9).Footnote 67 It was derived from several prototypes, the most influential being a map issued by Lafreri shortly before, in late September or early October of 1565 (fig. 10).Footnote 68 That model has the unique feature of portraying Malta in relation to the closest landmasses, thus situating it in the larger Mediterranean context. The Palombi mapmaker borrowed that strategy as well as the form of Malta itself, but he radically condensed the distances separating the archipelago from the coasts of Sicily and North Africa. As a result, Malta is drastically inflated in scale—an effect that is heightened by the way it appears uncomfortably cramped within the margins of the image—the seas surrounding it reduced to narrow channels just a few ship-lengths wide.

Figure 9. Palombi (attr.). Nuovo et ultimo disegno di Malta, Rome, 1565. Etching and engraving, 40 x 51.5 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

Figure 10. Antonio Lafreri. Nuovo disegno dell'isola di Malta et suoi forti, Rome, 1565. Etching and engraving, 37.5 x 45 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

Lafreri's map had also compressed the Mediterranean distances (albeit to a much lesser degree), as was openly acknowledged in the title cartouche, where the engraver explained that he had not “been able in practice to draw in the correct proportion, as the Island [of Malta] would have come out so small that it would not have been possible to say anything about it.”Footnote 69 In other words, the misrepresentation was a necessary sleight-of-hand to represent Malta's geographic context and, simultaneously, the specific military events that had made it the center of international attention. Such intentional distortion is quite common in news maps—but much less common is the explicit admission and explanation of it. The Palombi map, for its part, makes no such acknowledgment, despite pushing the distortion considerably further. The maneuver not only magnifies Malta, but also subtly raises the drama of the image, for it leaves no open sea, no blank space or visual breathing room: instead, every inch of the surface churns with activity.

For the depiction of certain details within Malta proper, the designer of the map consulted other models. Remarkably, he reinserted Genga's plan for the new, unrealized citadel, without adding “ruinata” to indicate its nonexistence, as Nelli had. Labeled “la nova citta” (“the new city”), that fort appears as a fully intact, if empty, bastioned circuit sprawling over Sceberras. For the area of Malta's main port, then, the Palombi mapmaker seems to have been going back to one of the many printed derivatives of Genga's plan. More originally—and in another brazen manipulation of scale—he has amplified the size of that center of action relative to the entire island, such that the harbor appears to take up a full half of Malta's width. All of these visual tricks serve as a reminder that the meaning of a news map was not conveyed by means of military operations and textual prompts alone: geography itself could be adjusted to shape the message.

The map provides an overview of the final episodes of the siege, a cartouche at upper left claiming to have derived the information from avvisi published on the tenth and nineteenth of September, a period bracketing the conclusion of the conflict. Through late July and August, Birgu and Senglea had continued to be subjected to relentless bombardment by the Ottomans. Brutal, but ultimately unsuccessful, assaults occurred on August 7 and 20–21. In early September, as the weather was beginning to turn, the Ottoman commander Mustafa ordered a march on Mdina, hoping to take it and set up camp there for the winter. At the last minute he called the operation off, based on (unfounded) fears that defenders within the city still had a large quantity of ammunition. The key turning point came days later, on September 7, with the arrival of the long-anticipated gran soccorso (big relief ): the major relief operation that arrived in the figure of Don García Álvarez de Toledo (1514–77), viceroy of Sicily, with some sixty ships and 10,000 men.Footnote 70

Depicting the arrival of the Spanish fleet and the aftermath of that momentous event, which finally secured the Knights of Saint John's deliverance, the Palombi map balances reportage and triumphalism.Footnote 71 At the top, the gran soccorso is shown departing from Sicily and making its way toward Gozo, at left. From there it turns southward, and proceeds to move counterclockwise along Malta's lower coastline. The picture of this great fleet encircling the island mirrors the arrival of the Ottoman fleet, almost four long months earlier, as depicted on Nelli's first map (fig. 4). Here, however, many more vessels are shown participating, several rows deep, in a victorious flotilla whose forward momentum seems inexorable. At lower left, three great infantry battalions disembark near the small island of Comino and head toward Mdina at center, as occurred right away on September 7. At their head, if one looks very carefully, is a tiny figure turning back and raising his sword: the map's legend explains that this scene, corresponding to the letter F, is Don García himself, exhorting his captains (fig. 11, lower left).

Figure 11. Detail from figure 9: Palombi. Nuovo et ultimo disegno di Malta.

On Sceberras, meanwhile, St. Elmo stands abandoned by the Ottomans (fig. 11, upper right). A final confrontation between the two sides took place on September 11, near Mdina: this skirmish is visible just above and to the right of the walled town, where a turbaned figure can be spotted collapsing at the tip of a soldier's thrusting sword (fig. 11, lower right). From that spot, the Turks flee somewhat chaotically toward upper left, with orderly rows of harquebusiers on their heels. Their destination is St. Paul's Bay, from which the Ottoman fleet is leaving. Fallen bodies litter the way, while small figures bob in the water, in an apparently futile struggle to reach the last departing ship (fig. 11, upper left).Footnote 72 In his authoritative eyewitness account of the siege, Francesco Balbi da Correggio (1505–89) wrote: “Those who could not get into the boats threw themselves into the sea, and, as they were wounded and tired, were drowned before they could reach the galleys.”Footnote 73

Of the dozen or so vignettes identified in the legend, perhaps the most symbolic is indicated by letter I—which notes that Don García, after delivering the relief force and circumnavigating the island, and just before sailing back to Sicily to collect a second squadron of reinforcements, fired a salute toward Grand Master de Valette and the Knights of Saint John in Grand Harbor. On the map, this moment is indicated by the galleys turning northward at upper right, smoke billowing from cannon on their prows (fig. 12, right). The map shows the guns of Birgu—where the standard of the Knights of Saint John flies high—answering in kind (fig. 12, bottom center), but in fact de Valette, low on gunpowder, had opted not to fire.Footnote 74 Meanwhile, the small, disheveled Turkish navy heads northeast, aiming for the narrowing escape route left between the head and tail of the encircling Spanish fleet (fig. 12, top center). A label next to the Ottoman vessels reads: “Armata turchesca che fugge,” or “the Turkish armada, which is fleeing.” This event did not occur until September 12, but here it appears as one part of a larger, continuous flow. In the Palombi map, a whole succession of events that transpired across five days is compressed into a single image. The account given here relates the vignettes in accordance with the known history, but the map itself gives few cues in this regard. Clear sequencing is elusive in news maps.

Figure 12. Detail from figure 9: Palombi. Nuovo et ultimo disegno di Malta.

The Palombi map was ambitious for attempting to compress a series of culminating moments into one image. At 40 x 51.5 cm, moreover, it was larger than those by Béatrizet and Nelli—the size of the copperplate necessitating that it be printed on carta reale, the second-largest standard size of paper.Footnote 75 These features suggest that the Palombi map was meant to be collected and admired—fittingly, as the siege was now over. Many believed the Christian world had been saved from the infidel. The struggle for the Mediterranean was far from done—the Battle of Lepanto, after all, was a mere six years later, and has traditionally been considered the decisive moment—but for the time being, there was a collective sigh of relief, together with the elation that comes from a massive underdog victory. As the Palombi map indicates, the story as told by news maps could help to elicit such responses among Western European beholders. That said, for the most part, these works minimize the human dimension. Even the map's vignettes of Don García rallying his captains or the Ottomans struggling for their lives, while informative, are disconnected and unaffecting—and in any case such anecdotal touches are relatively unusual. News maps tend to be populated by stick figures, positioned like so many toy soldiers of the armchair strategist. Faceless groups of infantry and cavalry do little to convey the human toll of wartime violence. Such expression was not the main goal of these works, which adopted a matter-of-fact tone, putting their viewers into the position of aloof observers rather than participants in the field. As discussed below, monumental, commemorative representations of the same events took a very different approach.

News maps, moreover, are not an inherently storytelling form. In their attempt to condense into a single image multiple events taking place across an extended span of time, they are comparable to late medieval and early Renaissance paintings that employ continuous narrative—but those pictorial works tended to foreground human actions (and increasingly, emotions), and to relate well-known stories. News maps, by definition, relate stories that are new and mostly unfamiliar—that have not yet become part of a common heritage or visual repertoire—and they foreground impersonal geography: where things happened, not how, or why. Sometimes news maps even leave confusion about who participated. When a legend is present, as it is on the Palombi map, it does little to help beholders grasp the unfolding of events, or the narrative arc. In the Palombi map, it is not even readily apparent who is the victor. There is no sense of heroism, or conclusion. Such details must be filled in by the viewer with reference both to the map's legend and to external knowledge of the history that was being written when the image was made. If there is a sense of drama in news maps, it is not to be found in their approach to representing the events in question. Rather, it lies in the tension in the air that surrounded them and the urgency with which they rolled off the presses, bringing critical information before the eyes of the public.

SOURCES, RHETORIC, AND ACCURACY

News maps drew from a variety of sources to inform their representation of events. For the most part, their pattern is simply that of public information being repackaged in a different format. They are most closely related to avvisi—relatively short, written news reports that could be secret or public, and that circulated in manuscript and increasingly in print—as well as similar news bulletins such as those distributed via the Fugger network.Footnote 76 Mapmakers sometimes explicitly acknowledged their debt to avvisi: the Palombi map, for instance, openly states that it is based on two dated ones, a declaration that seems to have served, in part, as an advertisement of up-to-the-minute accuracy—even if avvisi, like news maps, were not always reliable.Footnote 77

Maps occasionally accompanied news pamphlets as illustrations. This combination occurred more commonly in Northern Europe, where it was the custom to use woodcut for maps: a relief method easily combined with moveable type.Footnote 78 There are scattered examples of woodcut maps being included in Italian pamphlets, too, but they tended to be cruder and more schematic than the stand-alone items examined in this study. Most Italian news maps—the lion's share of those surviving from the Great Siege of Malta—are single, engraved sheets, which were complementary to but not formally conjoined with avvisi.Footnote 79 Even in Northern Europe, news maps were not always issued with pamphlets. Ganado and Agius-Vadalà have discovered a French advis that includes an exceptionally rare advertisement for a map: in other words, encouragement to the consumer to buy a separate but related product. “To the reader,” the text begins, “if it pleases you to see the plan of the Island of Malta, the Borgo of Malta . . . , the Turkish camp and batteries, and other details . . . , Monsieur Thevet . . . quite recently produced a beautiful and complete picture thereof, by means of which you can see and understand everything that you could wish for in this regard: for the satisfaction and contentment of your mind.”Footnote 80

Some news maps of the siege, like Béatrizet's, include minimal explanatory text, and the mapmaker must have assumed that his audience was deciphering the map in conjunction with other sources. Over time, however, news maps came to operate more independently, their verbal apparatus expanded with the addition of cartouches, legends, and descriptive captions, which abridge the content found in avvisi. This development was not linear, however: examples continued to abound of the more reticent kind of news map.

It is possible to gain an overview of the kinds of news items regarding Malta that circulated during and immediately after the siege—and with which news maps were potentially correlated—from Carl Göllner's compilation of European printed material relating to the Turks.Footnote 81 For the year 1565, Göllner (whose tally did not include singly issued maps) lists forty-six items, the majority of them news pamphlets, as well as a handful of longer, hastily assembled histories that appeared shortly after the siege's conclusion, in the autumn of that year. Capitalizing on the widespread excitement of the moment, these were essentially avvisi stitched together. The more polished eyewitness narratives that became standard references, by Balbi da Correggio and Antonfrancesco Cirni Corso (ca. 1520–ca. 1583), first appeared later, in 1567.Footnote 82

Most of the news pamphlets reporting events in Malta, be they avvisi, neue Zeitungen (as German versions were typically called), or the equivalents in other languages, were anonymous dispatches reporting specific episodes like the arrival of the Turkish fleet or the fall of St. Elmo, while others provided a digest of recent events to date. Another sizeable category consisted of eyewitness letters from the front by de Valette and other, less illustrious participants in the hostilities. All of these types were translated into the major European languages and published in dozens of cities north and south of the Alps, mirroring the international path of news maps, as will be detailed further below. A foremost example is a letter from Malta dated September 13, the day after the Turkish fleet retreated, written by Spanish Knight Francesco de Guevara (d. 1581). Albert Ganado and Joseph Schirò have counted sixteen surviving editions of this item, “the very first printed narrative of the Great Siege”: six in Italian, five in German, two in French, two in Dutch, and one in Latin.Footnote 83 Malta did not inspire the flood of literary pamphlets—performative material like songs, sonnets, orations, and sermons—that followed in the wake of Lepanto the following decade.Footnote 84 Lepanto, for its part, did not inspire the flood of maps that Malta did, perhaps because Lepanto was a naval battle that took place offshore rather than being enmeshed in distinctive geographic contours, and perhaps because it transpired on a single day rather than being drawn out suspensefully for months.Footnote 85 By the time the news of Lepanto broke, the matter had been decided: all that was left to do was celebrate.

Lepanto, like Malta, was a resounding triumph for Christian Europe. Although the nature of the printed material devoted to the two events diverged, in both cases it was bountiful. It is likely that coverage would have been much less had the outcome of either conflict been different. Bulgarelli, Pettegree, and others have pointed out that European printers were loath to transmit bad news.Footnote 86 Perhaps they did not want to incur the ire of bested rulers by circulating negative publicity, or perhaps they simply did not believe there was an audience eager to pay for it. Göllner's compilation lists dozens of news pamphlets detailing Charles V's 1535 conquest of Tunis, but none relating to the loss of the same port to the Ottomans the previous year—the event that provided the whole raison d’être for the Spanish retaliation—and few relating to the failed Algiers expedition six years later.Footnote 87 News maps follow the same general pattern. Of course, the outcome of Malta was very much in doubt during the summer of 1565, yet the maps kept coming, reflecting the duration and inherent dramatic tension of the struggle, whose prolonged ups and downs surpassed those of most sieges. Moreover, the news maps that were published in the midst of the affair were reissued for decades, through legions of copies and derivatives—and surely there would have been little lasting public appetite for these works had things ended differently.Footnote 88 The longevity of this media event in Western Europe can only be explained in light of its wildly successful conclusion.

Returning to the sources for news maps, avvisi and related pamphlets were helpful when it came to portraying military operations, but not when it came to cartography. For this aspect, the makers of news maps often took the path of least resistance—copying and borrowing from other printed maps. This fits the pattern of public information repackaged. It should be noted that there was a long tradition of mapmakers looking to other maps for their own work. Even the most learned and respected of sixteenth-century cartographers, like Giacomo Gastaldi (1500–66) in Venice or Gerard Mercator (1512–94) in Flanders, relied on a scholarly approach combining judicious compilation of existing sources and original observation.Footnote 89 That said, most designers of news maps were not experts in cartography, and their copying was less discerning—more along the lines of plagiarism, although it was a fairly common, and to an extent accepted, practice.Footnote 90

Printed exempla aside, the true cartographic antecedents of most news maps were surveys from the front, made on site by military engineers. In this regard, it is a case of highly classified information being made public. This part of the process is more opaque, for it is almost impossible to reconstruct how such top-secret materials leaked out—but it is clear that they did. Lafreri's fish-shaped map of 1551, it will be recalled, was based on the Knights of Saint John's site study of more than two decades earlier. How Lafreri gained access to that plan, or a copy of it, is unknown. Similarly, at least one of the maps that disseminated Genga's design for the new fortification on Mount Sceberras had access to that plan—the others probably copied the first printed one, most likely Nelli's version. It is possible that sometimes manuscript plans were leaked deliberately by those in power, in hopes of swaying public opinion toward a given point of view or course of action (such as the construction of a new citadel), while at other times, they were leaked furtively, for commercial or other motives. Similarly, the original designer is usually unknown.

There exists a handful of original surveys of the Great Siege made while it was in progress by on-site military engineers, both Christian and Ottoman. One such survival (fig. 13), ascribed to Girolamo Cassar (ca. 1520–ca. 1594) by Ganado and Agius-Vadalà, bears telling similarities to a map issued by Lafreri (fig. 14), and must have served him as a model.Footnote 91 Indeed, Lafreri's map is the same one that mentioned “those who are in Malta (who have sent the drawing),” and the close resemblance between the two maps attests to Lafreri's statement having a basis in truth—more so than his apology for the map's lack of polish, as it is in fact one of the largest and most refined maps produced during the siege.Footnote 92 A comparison of Lafreri's print with Cassar's plan reveals not just Lafreri's debt to that prototype, but also the changes he made to outfit it for public consumption. Lafreri focused on the harbor more closely than Cassar, but many details, from his chosen orientation (with southwest at the top) to individual geographic features, particulars of military architecture, and locations of Turkish camps, are very faithful to the survey. In other ways, Lafreri tempers the technical aspects of Cassar's plan. He enlivens the interiors of fortifications with buildings depicted in perspective, and transforms Cassar's abstract ballistic lines into little pictures of cannon blazing away. Lafreri also depicts human beings in action—stick figures, to be sure, but an animated presence nonetheless. These artistic strategies translate Cassar's technical graphic conventions into lay terms, while also lending greater visual interest. At lower right, a solitary Turk faces the beholder and gesticulates meaningfully toward Fort St. Elmo, which is empty, having fallen: this somewhat heavy-handed device comes straight out of the bible for Renaissance painters, Della pittura by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72).

Figure 13. Girolamo Cassar (attr.). Disegnio de i porti del isola di Malta (detail), 1565. Manuscript, 43.5 x 59 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

Figure 14. Antonio Lafreri. Ultimo disegno delli forti di Malta venuto nuovamente, Rome, 1565. Etching and engraving, 35.5 x 51 cm. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021, RCIN 721038.

News maps trumpeted their own basis in the latest surveys from the front even more vehemently than in the latest news reports. Here, the connection served not just to guarantee accuracy, but also to ensure a scoop, given that avvisi were publicly available while battlefield surveys were not. Lafreri mentions on three separate occasions that he has based a map on a drawing sent from Malta.Footnote 93 Giovanni Battista Pittoni (1520–83) was more emphatic. In the cartouche of a map he published during the siege, he simultaneously disparaged the errors of his competitors and celebrated his own exactitude: “As I wanted to demonstrate how far from the truth are the confusing designs [already in circulation], I have made up my mind to publish the true design which on the day after the assault was taken [from Malta] to Sicily by the Knight Raffaele Salvago and another Captain, which design has been approved and reviewed by many experts.”Footnote 94 Pittoni was pushing his bravado a step further by invoking expert sanction. Such claims were effective marketing tools, and it is likely that they were sometimes false, or at least stale repetitions of an established formula.

Mapmakers used additional rhetorical strategies to claim accuracy and novelty of information. Pittoni was not the only one to sing the praises of his improvements over previous maps. A map by Palombi stated smugly that it was “the latest print correcting all the others made to date.”Footnote 95 Nelli similarly stressed the superiority of his portrayal to all competitors: “I do not need to overstrain myself,” he sniffed, “by referring to the infinite number of those gentlemen who have unanimously agreed that of the many versions mine is the most correct.”Footnote 96 Like Palombi, he embraced a falsely impartial tone by ventriloquially placing hyperbolic approval in the mouths of unnamed (but apparently innumerable) experts. On a slightly more subtle level, variations on the words nuovo and vero—often in the superlative versions nuovissimo or verissimo—come up repeatedly in titles and cartouches, usually modifying the noun ritratto, or portrait, a term denoting verisimilitude or likeness that was used frequently for maps of towns and cities.Footnote 97

Clearly, mapmakers took any opportunity to emphasize a truthful representation based on the most recent state of knowledge, above and beyond others. That this was sometimes empty rhetoric is demonstrated by a series of maps published in Venice by Domenico Zenoi (fl. 1560–80). In June or July of 1565, Zenoi published a map that hailed itself as Il vero ritrato, venutto novamente (The true portrait, newly arrived) of Malta, asserting its trustworthiness and hinting at its source in a recent drawing from the front. Yet the map is based on a preexisting plate and includes many inexplicable errors: Turkish camps and battles are placed in the wrong locations, while Genga's unrealized fort is not only present but also mislabeled as the current residence of the Grand Master and the Knights of Saint John.Footnote 98

Zenoi—perhaps the unnamed target of Pittoni's allusion to “confusing designs” already in circulation—must soon have become aware of the problems with his map, because within weeks he brought out a heavily reworked second state of the plate, terming it Il vero disegno del porto di Malta (The true design of the port of Malta), perhaps to distinguish it from his own previous, untrue version.Footnote 99 Most of his improvements were cribbed directly from Pittoni's map—which, after all, had “been approved and reviewed by many experts.” Shortly after, Zenoi produced another creative compilation of existing prototypes, which he dubbed the Verissimo disegno del porto di Malta (Truest design of the port of Malta).Footnote 100 Finally, in late August, Zenoi published a map from another plate, “newly amended of many errors” (“di nuovo da molti errori emendato”)—although it is unclear whether he is owning up to his own previous errors, or implying that he has corrected those of others.Footnote 101 What is clear is that this map, too, had its share of mistakes and falsehoods. Zenoi's bluster is extreme, but it reflects the extent to which accuracy—or at least the semblance of it—was a desirable quality for map consumers who were keen to follow momentous events unfolding far away.

There was an additional, implicit factor that contributed to the perception of exactitude in news maps: the measured graphic language of cartography itself.Footnote 102 Associated with the specialized expertise of surveyors and military engineers, cartography had progressed by leaps and bounds in the sixteenth century—with technological improvements going hand in hand with new modes of representation. Surveying and military engineering were increasingly seen as gentlemanly skills, and there arose a whole category of printed treatises on the topic geared toward a nonspecialist audience.Footnote 103 The modern notion that cartography is an objective science has its origins in this time. Just by virtue of being maps, images of the siege of Malta gained a certain credence.

DISSEMINATION AND COMMEMORATION

Italian news maps of the Great Siege were the first to appear on the market and remained the most plentiful, even if one allows that more were preserved relative to their Northern counterparts thanks to their later inclusion in composite atlases.Footnote 104 As noted, some maps issued during the siege continued to be reissued for decades, long after the event itself had ceased to be newsworthy. Lafreri's Ultimo disegno (Latest drawing), for example, was published in four states through 1602—at which point it was hardly the “latest drawing”—and spawned many copies.Footnote 105 Restrikes and later editions took on new meaning as time went on, becoming ways of retracing the past rather than monitoring the present.

Unsurprisingly, given that events in Malta were considered an existential threat to Christian Europe and concerned multiple major European powers, the prints issued in Rome and Venice in late spring and summer of 1565 were quickly copied north of the Alps. Adding to the transnational interest in the siege was the heterogeneous makeup of the Knights of Saint John themselves, who hailed from diverse regions of France, Italy, Spain, Germany, and many other places.Footnote 106 In August, André Thevet (1502–90) published a woodcut in Paris based loosely on Nelli's map of July 8, with some elements taken from Béatrizet's map (this is the item mentioned previously as having been advertised in a separate advis).Footnote 107 That same month, a German adaptation of one of Lafreri's maps appeared in Nuremberg, published by Hans Wolff Glaser (ca. 1500–73).Footnote 108 In October, Antwerp printer Hieronymus Cock (1518–70) published a French-language map based on a prototype of several months before by Roman mapmaker Mario Cartaro (d. 1620), updating its information to reflect later stages of the siege.Footnote 109 Cock employed exactly the same adjectives as his Italian colleagues, titling his map La vraye et nouvelle description de Malta (The true and new description of Malta), and despite its derivative nature, he did not hesitate to add that it was “contrefaictes au vyf,” or “made from life”: another common rhetorical strategy to assure its credibility.Footnote 110 In September, a map based on Zenoi's Il vero disegno del porto di Malta was attached to a pamphlet published in Augsburg by Matthäus Franck (fl. 1560s), complete with many of the Venetian prototype's fictions.Footnote 111

Not all Northern maps were so plainly imitative. Toward the end of the year, in Nuremberg, Mathias Zündt (ca. 1498–1572) published a splendid map giving a detailed overview of the siege (fig. 15).Footnote 112 His main point of departure was the Palombi map (fig. 9), to which his own was comparable in size, but he referred to a number of other cartographic sources to compile an original image. One of Zündt's innovations was the inclusion of an inset map of all of Europe and the Mediterranean at lower left, in a nod to the larger geopolitical context for Ottoman-Christian conflicts. Within the map proper, he provided a summary of events, from the May arrival of the Turkish fleet and its anchorage at Marsascirocco at lower right, to the struggle for Fort St. Elmo toward the center, the Ottoman assaults on Birgu and Senglea, the arrival of the gran soccorso, and the departure of the Turks in early September. Zündt pushed pictorial aspects further than earlier maps: people, ships, and vignettes are more detailed, carefully rendered, and inflated in size, while many more central characters and episodes are included and labeled. As usual, the mapmaker mixed truthful reporting with honest mistakes, while sprinkling in some deliberate fiction—the most brazen example being a final, heated naval battle between the two sides that is depicted toward the top of the map, in the channel separating Sicily and Malta. Zündt seems to have been dissatisfied with the anticlimactic ending of the siege, in which the Turkish fleet simply limped off toward home. Apparently he could not resist the impulse to send them off with a bang, inserting what today would be considered more of a Hollywood ending.

Figure 15. Mathias Zündt. Gewisse Verzaychnus der Insel und Ports Malta, Nuremberg, 1565. Etching and engraving, 32 x 49 cm. Image courtesy of Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Heritage Malta, and the Malta Study Center at the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library.

In several respects, Zündt's map moves into a different realm from the others examined thus far. Published a few months after the siege had concluded, it not only summarizes the entire sequence of events, but also gives commemorative shape to them. The perspective is more global and sweeping in this map than in most published in the midst of the siege and the production values are distinctly higher—more time, care, and resources having been devoted to its production. Not coincidentally, Zündt's map was also a commissioned work, unlike any of the others considered thus far. Joining the ranks of Meldemann's spectacular circular view of the 1529 siege of Vienna, it was financed by Nuremberg's city council, which clearly had an established tradition of procuring celebratory images of Christian victories.Footnote 113 In sum, Zündt marks the beginning of a transition from reporting news from Malta as it happened toward memorializing it as a past event: enshrining it in the annals of history.

The process was carried much further in monumental, painted depictions of the siege that soon graced halls of state throughout Europe, the earliest dating from just a year or two after the hostilities. Noted examples are in the Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola and the Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Palace.Footnote 114 These cycles cannot be examined here, but in both cases, the artists relied on widely available news maps by Lafreri, Nelli, and others, as did Italian artist Matteo Perez d'Aleccio (1547–1628) in his seminal cycle of twelve frescoes (1576–81) depicting the Great Siege for the Grand Master's Palace in Malta.Footnote 115 Now damaged, the series is best known through the luxury album of fifteen etchings d'Aleccio published in Rome in 1582, reproducing the murals.Footnote 116 Both versions were very much in line with established conventions for monumental, commemorative battle cycles for powerful rulers.Footnote 117

Even a cursory examination reveals the basic mechanisms by which d'Aleccio transformed preexisting news maps into commemorative visual history. First, he separated and ordered individual events sequentially, in the case of the etchings adding explanatory captions. Consequently, less outside knowledge was required of the beholder. D'Aleccio also inserted many more trappings of fine art: allegorical figures, pictorial vignettes, escutcheons, and other such symbolic and narrative devices. For example, his second image (and first map), showing the arrival of the Turkish fleet, is derived from Lafreri's fish-shaped plan of the archipelago, but the map is now capped by a heavenly scene presided over by Christ and God enthroned, with the Virgin Mary and saints at their feet, interceding on behalf of the Knights of Saint John (fig. 16). Cartography, here, has been infused with divine providence and favor. In other images, d'Aleccio makes the cartographic base a backdrop for a battle scene, full of drama and featuring human actors who dominate the foreground, inhabiting their own spatial logic distinct from their topographically accurate setting (fig. 17). The prominence and individualization granted to key players like de Valette or Mustafa signal the grand, heroic tradition in which d'Aleccio was operating. The radical departure from news maps is evident in the contrast between these figures and the minuscule, faceless iteration of Don García on the Palombi map.

Figure 16. Matteo Perez d'Aleccio. Disegno dell'isola di Malta et la venuta dell'armata turchesca (second image and first map in the series), Rome, 1582. Etching and engraving, 31.5 x 45 cm. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021, RCIN 721033.b.

Figure 17. Matteo Perez d'Aleccio. Assedio e batteria al borgo e alla posta di Castiglia (eighth image in the series), Rome, 1582. Etching and engraving, 32 x 45 cm. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2021, RCIN 721033.h.

News maps like that one occasionally labeled protagonists or hinted at sequencing, but for the most part their cartographic mode is dehumanized and ahistorical: no real hero emerges from their faceless stick-figure staffage, no clear narrative arc from their jumble of vignettes, no sense of cause and effect linking the diverse events represented. D'Aleccio's series encapsulates the way news maps could inform other types of visual expression, while differing starkly from them. His etchings can be more or less documentary, and more or less propagandistic—or both at the same time. The cartographic accuracy of his settings could attest to the truth of the events depicted therein.Footnote 118 Indeed, such elite and ultimately canonical depictions actualize the cliché that history is written by the victors—a version of history, needless to say, that favors the actions of great men, not larger social forces or seismic if slow-moving cultural shifts. Be that as it may, d'Aleccio moves seamlessly between modes, deftly navigating the fine line between ephemerality and monumentalization, reportage and visual statecraft.

CONCLUSION

Voltaire (1694–1778), in his Annales de l'Empire (1753), claimed that “nothing is better known” than the siege of Malta. That might have been true in his time, but today it is sobering to see how an event that sparked such international interest at the time, and for long after, could be relegated to an obscure chapter of history in modern times. The Great Siege was considered a major turning point when it happened, but the degree to which it marked a sea change in the larger history of Ottoman-Christian relations in the Mediterranean is debated. The print coverage of the Great Siege was, however, an undeniable watershed in the early history of news reporting. For the first time, a rich and abundant variety of print media, in formats both verbal and visual, was deployed to meet international demand, while fueling further demand.

One lingering question merits a brief excursus: how did the other side represent the same event? In this study, the discussion of news maps relating to Malta must remain one-sided, for there was no comparable category of images available to the Turkish public.Footnote 119 This is not to say that Ottoman cartography was inferior: on the contrary, it was highly sophisticated and in many respects the equal of Western European mapping.Footnote 120 The Topkapi Museum in Istanbul houses a highly accurate manuscript survey on parchment made by an Ottoman military engineer during the siege that is every bit as accomplished as Cassar's plan.Footnote 121 There also exist many fine miniatures of battles and sieges during the time of Suleiman by famous topographical painter Matrakçi Nasuh (d. 1564), who created four luxury manuscripts for the sultan relating to Ottoman military campaigns.Footnote 122 None of these works, however, entered the public sphere, for Turkish print culture developed considerably later.Footnote 123 Matrakçi did not publicize his miniatures the way d'Aleccio did his mural cycle: the viewership for those miniatures, created for the most privileged of patrons, remained exclusive. Cartography in general was the province of the elite, and therefore did not have the impact on public perceptions of major events in the Ottoman Empire that it did in Europe.