Introduction

Can constitutional court decisions shape public opinion on a governmental policy? In this study, we explore the relationship between the court and the public by examining the extent to which courts can influence public opinion regarding a government bill. We argue that the public support for courts allows them to move public opinion on public policies into the direction of their rulings. However, as the novelty presented in this study, we show that this only holds when courts possess a higher institutional legitimacy.

Legitimacy is perceived to be the major source of power of constitutional courts as they have no formal means to ensure compliance with their decisions (Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2015). As such, legitimacy has been the subject of decades of scholarly attention. Most of the work focuses on the question of whether the court's legitimacy suffers when it releases unpopular decisions (Bartels & Johnston, Reference Bartels and Johnston2013; Caldeira & Gibson, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson & Nelson, Reference Gibson and Nelson2015). Another strand asks whether courts can draw on their institutional legitimacy to move public opinion on public policies in the direction of their rulings. This is called the ‘legitimacy‐conferring capacity’ of courts. The evidence – mostly from the US Supreme Court – of such a legitimacy‐conferring capacity of courts is mixed. Most observational studies (Marshall, Reference Marshall1987; Stoutenborough et al., Reference Stoutenborough, Haider‐Markel and Allen2006) find no sign for such a legitimating power of courts. By contrast, experimental studies (Bartels & Mutz, Reference Bartels and Mutz2009; Hoekstra, Reference Hoekstra1995) find that the Supreme Court is able to move public opinion in the direction of the public policy that it endorses. Similar results are found for Russia (Baird & Javeline, Reference Baird and Javeline2007) and the United Kingdom (Gonzalez‐Ocantos & Dinas, Reference Gonzalez‐Ocantos and Dinas2019).

In order to advance our understanding of European constitutional courts and their importance as a potential ‘legitimizer’ of public policy, we improve upon existing work in two directions. First, previous studies exclusively focus on the US Supreme Court, whereas no existing study analyzes the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of European courts. Therefore, it is unclear whether the findings from the US Supreme Court can be generalized to other court types such as European constitutional courts. Second, prior work constantly assumes that courts belong among the most trusted branches of the government. This surely holds for the US Supreme Court, although it does not hold empirically for other countries given the varying degrees of public support for national high courts worldwide (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). Consequently, the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of courts should also vary: courts with a higher level of public trust are expected to have a higher legitimacy‐conferring capacity than those with a lower level of trust. Despite the simplicity of this argument, it has never previously been tested in a comparative scenario.

We put this theory to the test by comparing the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of two major European constitutional courts with different levels of trust by citizens, namely the French Conseil Constitutionnel (CC) and the German Federal Constitutional Court (GFCC) in a most different systems design (Przeworski & Teune, Reference Przeworski and Teune1970). We conduct several survey priming experiments in a unique, cross‐institutional comparative design. The experiments are embedded in large, representative electoral surveys in both countries, with more than 2,600 respondents each. In our experiments, we provided the respondents information on a fictitious bill on school security. For the different experimental groups, we varied information on the court's approval or disapproval of the bill, as well as other institutions’ approval or disapproval.

We find that the German court can move public opinion into the direction of its decision by placing its stamp of approval or disapproval on public policies. This effect is sufficiently strong to even shape the opinions of those who have strong pre‐existing attitudes towards the issue. We attribute this to the broad institutional support for the German court. By contrast, we find little legitimacy‐conferring capacity for the French Conseil. While there is movement in the expected direction, it is not significant. However, we display evidence that the individual‐level trust conditions the effect of the courts’ approval and disapproval among French and German respondents. The movement is mainly driven by citizens with a high level of pre‐experimental trust in the court in both countries – and France has far fewer citizens trusting the court strongly or very strongly than Germany, as we can show. The findings of this study thus have implications for both our understanding of the role of constitutional courts in democratic politics and public opinion formation in general.

The paper proceeds in the following steps. After the introduction, we outline the legitimacy‐conferring effect and present the main hypothesis in the second section. In the third section, we introduce the research design regarding the case selection and the design of the experiment. The fourth section presents the central results of the experiment and we also conduct a number of tests regarding the effects of prior attitudes, individual‐level attitudes, and robustness checks. Finally, we conclude in the last section.

Court decisions, governmental policy and legitimacy

Legitimacy is perceived to be an important source of power of courts. While much of the existing research on court legitimacy focuses on whether citizens agree or disagree with court decisions and what this implies for citizens’ trust in the court and decision making, it is also important to consider the reversed causal direction, namely the effects of judicial decisions on public opinion. Courts are often among the most trusted political institutions in Western democracies, and they are generally perceived as highly legitimate (Caldeira & Gibson, Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Gibson & Nelson, Reference Gibson and Nelson2015). One of the consequences of this property is the ability of courts to pass their legitimacy to public policies. This argument dates back to Dahl (Reference Dahl1957), who argues that the US Supreme Court is a ‘legitimizer’ of majority coalitions’ policies. He argues that this power stems from the Supreme Court's function as the sole legitimate interpreter and protector of the constitution (Dahl, Reference Dahl1957, p. 293). Supreme Court decisions are therefore viewed as credible, legitimate and rightful. This phenomenon is called the ‘legitimacy‐conferring capacity’ or endorsement effect (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992, p. 33) of courts. In other words, courts are able to use their diffuse supportFootnote 2 – or their ‘reservoir of goodwill’ (Easton, Reference Easton1965) – to induce public (non)‐acceptance of governmental policies via their rulings.

An extensive body of empirical literature exists on the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the US Supreme Court using different measures and methods, with mixed evidence overall. Unfortunately, the findings of these studies depend – at least to some extent – on the nature of the research design. Experimental studies tend to find relative consistent legitimacy‐conferring effects of Supreme Court decisions (Bartels & Mutz, Reference Bartels and Mutz2009; Clawson & Kegler, Reference Clawson and Kegler2001; Hoekstra, Reference Hoekstra1995). By contrast, observational studies mostly find no evidence of a legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the Supreme Court (Hanley, Reference Hanley, Persily, Citrin and Egan2008; Marshall, Reference Marshall1987; Stoutenborough et al., Reference Stoutenborough, Haider‐Markel and Allen2006), although sometimes decisions can polarize public opinion (Brickman & Peterson, Reference Brickman and Peterson2006; Hoekstra & Segal, Reference Hoekstra and Segal1996; Johnson & Martin, Reference Johnson and Martin1998). To further complicate matters, other observational studies find that Supreme Court decisions only induce changes in public opinion under certain conditions, such as saliency (Christenson & Glick, Reference Christenson and Glick2015, Reference Christenson and Glick2018; Tankard & Paluck, Reference Tankard and Paluck2017) or media coverage (Linos & Twist, Reference Linos and Twist2016).

When looking at other court types such as European ‘Kelsenian’ constitutional courtsFootnote 3, we must recognize that little to nothing is known about the interplay between court legitimacy and public opinion. Scholars have not investigated the effect of court decisions on public opinion. If at all, they have examined the role of public support for constitutional court decision making in a separation‐of‐powers framework (Staton and Vanberg, 2008; Brouard, Reference Brouard2009; Sternberg et al., Reference Staton and Vanberg2015; Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2005). In these studies, the authors examine whether constitutional courts have to adjust their decision making in accordance with public opinion, or rather if the opposite effect applies. Other scholars have mainly focused on justices’ preferences and court vetoes (Brouard & Hönnige, Reference Brouard and Hönnige2017; Dyevre, Reference Dyevre2016; Grendstad et al., Reference Grendstad, Shaffer and Waltenburg2015; Hanretty, Reference Hanretty2012; Hönnige, Reference Hönnige2009; Santoni & Zucchini, Reference Santoni and Zucchini2006).

Only a few studies explicitly investigate court legitimacy and diffuse support in the European court context. Most of these studies are rather descriptive or case studies They show that for the German court diffuse support lowers after controversial rulings like the ‘Kruzifix’‐decision (Vorländer & Schaal, Reference Vorländer, Schaal and Vorländer2002). There is no such study for France. However, even these studies impressively show that the popularity of a decision by the court influences the trust in the court at a diffuse level. Notable for European courts are Baird and Javeline (Reference Baird and Javeline2007), who find legitimacy‐conferring effects for the Russian court in a survey experiment on religious rights. They are also able to show systematic differences between more and less tolerant respondents. Gonzalez‐Ocantos and Dinas (Reference Gonzalez‐Ocantos and Dinas2019) also find legitimacy‐conferring effects in their survey experiment on Brexit decisions in the United Kingdom. However, existing work has not directly tested the legitimacy‐conferring capacity in a comparative setting. There is also no systematic research on diffuse levels of trust in constitutional courts over time and across European countries. Exceptions are Eurobarometer, European Social Survey (ESS) and World Values Survey (WVS) data, which, however, asks for trust in the legal system only (Garoupa & Magalhães, Reference Garoupa and Magalhães2021), and a newer study by Engst and Gschwend (Reference Engst and Gschwend2021) for nine countries. In order to advance our understanding of European constitutional courts and their role as a ‘legitimizer’ or ‘de‐legitimizer’ of public policy, we improve upon existing work in two directions. First, it is unclear whether the (mixed) findings from the US Supreme Court can be generalized to other court types such as European constitutional courts. Second, previous studies were single‐country studies with deviating research questions and designs, whereby the results are not directly comparable. As public support for courts varies across national high courts (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998), it seems necessary to account for the effect of the varying support at the system level. The novelty of our study lies in the fact that we explore a ‘most different systems’ scenario: what happens to public opinion if a court with higher diffuse support decides on public policy compared with a court with lower diffuse support deciding on the same issue?

For instance, the German court enjoys consistently high public confidence and its public support often exceeds that of other political institutions (Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2005; Vorländer & Schaal, Reference Vorländer, Schaal and Vorländer2002). By contrast, constitutional courts like those in Russia or Bulgaria possess much lower levels of public support (Staton and Vanberg, 2008; Trochev, Reference Trochev2008). The reasons for a lower institutional legitimacy are manifold. For example, some newly installed courts have had little time to build institutional trust compared with long‐established courts such as the US Supreme Court or courts installed after the Second World War. Other reasons include the institutional embedding in the political system and decisions that receive little specific support (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998).

Our central theoretical claim is the same as in previous studies: constitutional courts receive their legitimacy‐conferring capacity from their perception as the only legitimate and credible interpreter of the constitution. This legitimacy is therefore grounded in their diffuse support, and it allows them to move public opinion into the direction of their ruling. However, we argue that this does not ultimately hold for all constitutional courts. As Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998, p. 365) note, ‘national high courts vary enormously in the degree to which they have achieved institutional legitimacy’. These varying degrees of public support should also be considered theoretically.

We now put these two points together: as public support and the legitimacy of courts varies, so does the legitimacy‐conferring capacity. Courts with a higher level of support are expected to have a higher legitimacy‐conferring capacity than courts with a lower level of support. The conferring of legitimacy can work in both directions: a trusted court can confer legitimacy to a policy with low specific support (Easton, Reference Easton1965) by declaring it constitutional, but it can also take legitimacy away from a policy with high specific support by declaring it unconstitutional.

We should be able to discriminate legitimacy‐conferring effects, namely people moving in the direction of the court ruling in the context of constitutional courts with higher diffuse support, but not in the context of constitutional courts with lower diffuse support. Moreover, the difference should not only be measurable at the aggregate level between courts but also at the individual level for citizens who strongly support the court as an institution and those who only weakly support it. The implication with respect to their legitimacy‐conferring capacity is then as follows:

Hypothesis 1: When a constitutional court has higher diffuse support, its ruling should move more strongly public opinion regarding a governmental policy into the direction of the court ruling.

In summary, we improve upon previous research by arguing that the varying degrees of diffuse support for constitutional courts affect their legitimacy‐conferring capacity, such that courts with higher diffuse support are able to move public opinion, unlike courts with lower diffuse support.

Comparative research design

In this section, we introduce an experimental research design that allows us to test the two competing observable implications in a comparative setting.

Case Selection

The case selection of the two constitutional courts in this comparative study is motivated by the most different system design (Przeworski & Teune, Reference Przeworski and Teune1970). It aims to the GFCC test a mechanism at the individual level for very different case settings at the aggregate level to confirm its generalizability. For our comparative design, we chose (GFCC) and the French CC.

In order to test our hypothesis on the legitimacy‐conferring capacity, the two courts have to meet the following requirements. First, both constitutional courts must possess the right of judicial review, because otherwise the logic of the legitimacy‐conferring capacity could not be applied. As we want to go beyond the Supreme Court, a comparison between two ‘Kelsenian’ type courts is appropriate. Both courts have the right to exercise judicial review (Hönnige, Reference Hönnige2009), and thus meet the first condition. However, within the set of these courts they are institutionally very different regarding the age of the court, their powers and the justice selection system (Brouard & Hönnige, Reference Brouard and Hönnige2017). The differences are so vast that some authors argue that they might even be classified as two sub‐types of European courts (Epstein et al., Reference Epstein, Knight and Shvetsova2001).

Second, another pre‐requisite for the mechanism to work is that decisions of the two courts can be observed by the public in a similar way. In both countries, the court publishes press releases on selected decisions and all decisions are almost instantly available to a wider public on the website. In both countries, the court may hear selected cases in oral hearings, although the space for people actually attending is very limited in both countries. Therefore, in both countries the media are the main channel for the communication between the court and citizens. For the German court, recent research has shown that the use of oral hearings and press releases strongly influences whether decisions are perceived by the media (Meyer, Reference Meyer2019). For France, there is no research on this to date.

Third, the theoretical argument requires two courts that considerably vary in their degrees of public support to ascertain whether support has an effect at the aggregate level. The GFCC is a prime example of a constitutional court that enjoys rather high public confidence (Vorländer & Schaal, Reference Vorländer, Schaal and Vorländer2002). By contrast, the French CC is one of the constitutional courts in Western Europe that cannot rely on overwhelming public support, unlike other courts (Brouard & Hönnige, Reference Brouard and Hönnige2017).

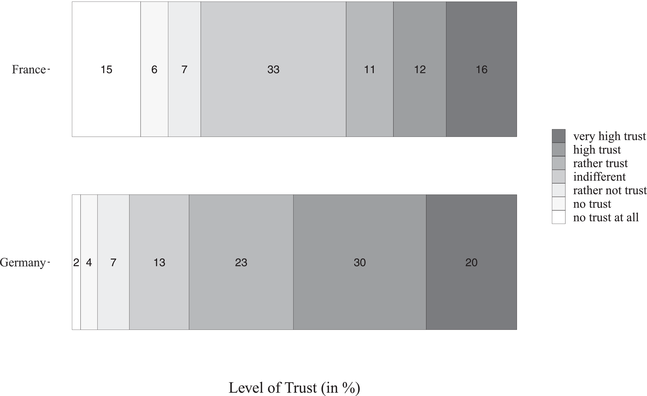

Numbers from our surveys confirm these claims about differences in public support. Figure 1 shows the percentage of the trust rating among respondents of representative surveys in both Germany and France.Footnote 4 It is evident that the GFCC enjoys much higher public support than the CC: the percentage of respondents at the higher trust levels in Germany is always above the percentage of respondents in France, and vice versa. In Germany – for instance – every second respondent (50 per cent) has high or very high trust in the GFCC, while only 28% have the same trust in the CC. Moreover, while in France more than every fifth (22 per cent) respondent has no trust at all in the CC, only 6 per cent have the same low levels of trust in Germany.

Figure 1. Comparison of the institutional trust in the constitutional courts of Germany and France.

Note: Comparison of institutional trust in the constitutional courts in Germany and France. Data from GIP Wave 26 and ENEF 5.

These numbers also correspond to the findings of previous studies (Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2005; Vorländer & Schaal, Reference Vorländer, Schaal and Vorländer2002) for the German court. The German court belongs among the most trusted courts in a comparison of 17 European high courts. For the French court, no older data are available, as the study by Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998) uses the Cour de Cassation instead of the CC. If we compare our French data with the Gibson et al. (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998) data, the Conseil would be at the lower end of the range, close to Bulgaria. The Eurobarometer (EB 90, 2018) contains a variable for ‘trust in justice/trust in the national legal system’, which could be interpreted as a closest equivalent. Here, Germany is again at the top with 73.68 per cent of respondents trusting the legal system (West Germany), while France is ranked in the middle with only 46.49 per cent of respondents trusting the legal system (see Appendix Figure 1B).

Fourth, it is also important, that the court and the legislative institutions – government and parliament – are in a similar relative position with regard to the level of trust for the mechanism to work in a similar way (see Appendix Figure 1C and 1D). In both countries, the courts are trusted the most, followed by the parliament and government with a substantial distance. In Germany, according to the Eurobarometer data (EB, 902018), 63.95 per cent trust or rather trust in parliament and 59.25 per cent in government. In France, 26.71 per cent trust or rather trust in parliament and 26.27 per cent in government.

Fifth, because both courts and their political systems are different, differences in outcomes may not be explained at all by differences in aggregate court support. In accordance with the most different systems design of Przeworski and Teune (Reference Przeworski and Teune1970), we need to provide evidence that the same mechanism is at play at the individual level in both cases.

Experimental design

In order to investigate whether constitutional courts can move public opinion, we use an experimental design embedded in two national representative surveys in Germany and France. The same experiment was implemented in both countries. In Germany, the experiment was implemented as part of Wave 26 (November 2016) and Wave 27 (January 2017) as well as the core study in wave 25 (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Bruch, Felderer, Gebhard, Herzing and Krieger2017a, Reference Blom, Bruch, Felderer, Gebhard, Herzing and Krieger2017b, Reference Blom, Bruch, Felderer, Gebhard, Herzing and Krieger2017c) of the German Internet Panel (hereafter GIP). The GIP collects information on political attitudes and preferences of respondents through bimonthly longitudinal online panel surveys. Although administered online, all surveys are based on a random probability sample of households recruited fact to face from the German population, which were provided with access to internet and special computers if necessary (Blom et al., Reference Blom, Gathmann and Krieger2015). Waves 26 and 27 include N = 2,867 registered participantsFootnote 5 and are representative of both the online and offline population aged 16–75 in Germany. In France, the experiment was embedded in wave 16 (July 2017) and wave 17 (November 2017) of the French National Election Study 2017 (l'enquête électorale française, hereafter ENEF). ENEF 2017 was a panel survey conducted online by IPSOS with more than 12,000 participants. As with almost all surveys in France, sampling is conducted with a quota method based on age, gender, occupation, region and type of residential area.Footnote 6 The experiments were allocated to a random sub‐sample of N = 2,661 respondents.

In the experimental design, we compare the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the GFCC and the CC with other institutions. We employ a survey priming experiment where respondents are provided with a (hypothetical) public policy issue. The proposed policy in the experiment is a hypothetical ‘school security law’. According to this law, armed security forces are allowed to search students and their lockers to prevent increasing school violence. Precisely, we ask (translation by the authors): ‘In recent years, there were a number of school shootings at home and abroad. Imagine the following situation: Parliament decides on a new school security law. Schools are supposed to hire private security services/allow police access to schools. They are allowed to carry weapons. The security services/police are allowed to stop‐search pupils and their bags regularly. The aim of the new legislation is to improve the safety at schools, although this reduces the freedom of pupils’.Footnote 7

This issue was chosen for two reasons: first, it is an issue that could credibly be addressed by the constitutional courts and other political institutions; and second, it is an issue where sufficient polarization across the respondents can be expected. This ensures sufficient variation in the outcome variable.

Along with the issue, respondents were randomly assigned to an institutional endorsement manipulation containing a single sentence. This manipulation occurred in the form of different institutions stating that they either approve or disapprove the school security law at the end of the example above: ‘[Institution Name] approves/disapproves the new legislation.’. Overall, we used three different institutions in Germany and two in France. Accordingly, we are able to compare the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of these institutions vis‐à‐vis the constitutional courts. Comparing institutions across systems is always a difficult enterprise due to the problem of equivalence (van Deth, Reference Deth and Deth1998).

We therefore opted to use two committees with coordinating and consultative character, respectively, regarding essential questions of school policy. They would be involved in drafting a new piece of school security legislation – as presented in the experimental issue – to express their opinion. In Germany, we used the Conference of the Ministers of Education, which comprises the 16 ministers of education of the 16 states, as school policy is in their power. The conference is used to coordinate school policy nationally. As the equivalent in France, we use the high organizational school committee called the Haut Conseil de l’Éducation.Footnote 8 It is responsible to the Education Minister and comprises nine scientists and politicians, and it advises on school politics and programs and their evaluation.

Additionally, in the second wave, the German survey experiment used the Federal Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (in short, the Data Security Official) to replace the Conference of the Ministers of Education. The Data Security Official would also be involved as soon as personal information on pupils is involved. The institutions are known to the public and are regularly reported on in the media nationally. In the French case, the policy was varied in the second wave, and the results can be found in the online Appendix. Here, we used an economic policy on pensions and consequently controlled with a pension advisory board, the Conseil d'Orientation des Retraites.

Accordingly, we held constant the committees across countries in the first wave, but varied the control institutions and examples within countries in the second wave. A control group received no manipulation at all in both waves.

The online Appendix also includes further details about the wording of the endorsement manipulations and measurement of variables. After the experimental manipulation, respondents were asked to give their opinion on such a school security law on a five‐point scale, ranging from ‘fully disagree’ to ‘disagree’, ‘neither/nor’, ‘agree’ to ‘fully agree’.

The chosen experimental design provides several methodological strengths for assessing the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the different institutions. First, because it contains a true control group that did not receive any institutional endorsement manipulation, we have a reasonable baseline for comparison. Any systematic shift in opinion away from the control group can be attributed to the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of either institutional source. Second, the data quality and size of the survey experiments are an improvement compared with other experimental studies, which mainly rely on laboratory studies involving student samples. Having the same experimental design administered in national representative mass surveys in two countries increases the external validity of our study (Hainmueller et al., Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto2015), while internal validity remains high.

Results of the survey experiments

In this section, we first present the results on the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the courts for different experimental conditions. We then test the effect of strong pre‐existing attitudes, control for different levels of trust and conduct robustness tests.

The legitimacy‐conferring capacity of courts

Due to the categorical, ordered nature of the dependent variable, we use an ordered probit model to analyze the experimental data.Footnote 9 In order to ease the result presentation and further analyses, the original five‐point scale dependent variable was recoded into a three‐point scale variable with three ordered categories, namely disagree, indifferent and agree.Footnote 10 For the German analysis, we aggregate both GIP waves into one dataset to increase computational efficiency. Because the respondents’ answers are then no longer independent, the standard errors are clustered by respondents in the German analysis. In the robustness section later, a variety of alternative models are estimated to demonstrate that the results also hold when the original five‐point scale dependent variable is used or when the German data is not aggregated. In our online Appendix, we also provide a descriptive overview of the distribution of attitudes towards the school security law across German and French respondents. The main differencesFootnote 11 between the two countries is that the majority of the German respondents oppose the proposed school security law (57 per cent), whereas almost a majority of French respondents support it (48 per cent).

For both countries, we estimate a simple ordered probit model with the three‐point scale ordered respondents’ opinions on the school security law as the dependent variable and each experimental treatment group as a dummy independent variable. The control group is used as the reference category. The simplicity of the model derives from the experimental design, with the random assignment of the respondents to the treatment groups.

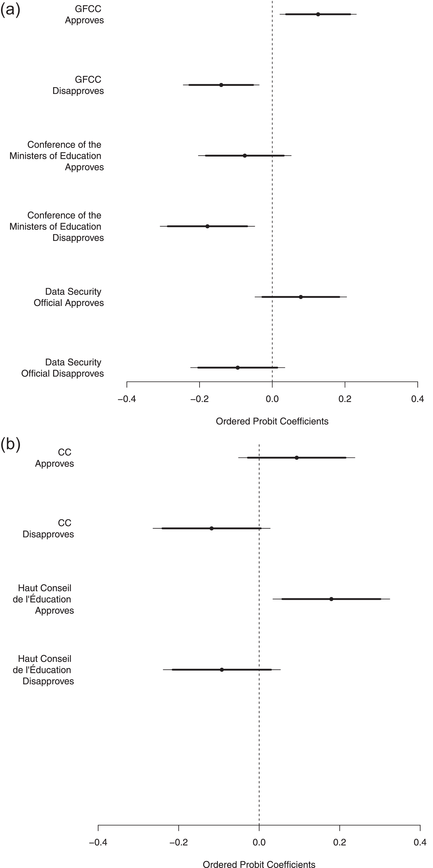

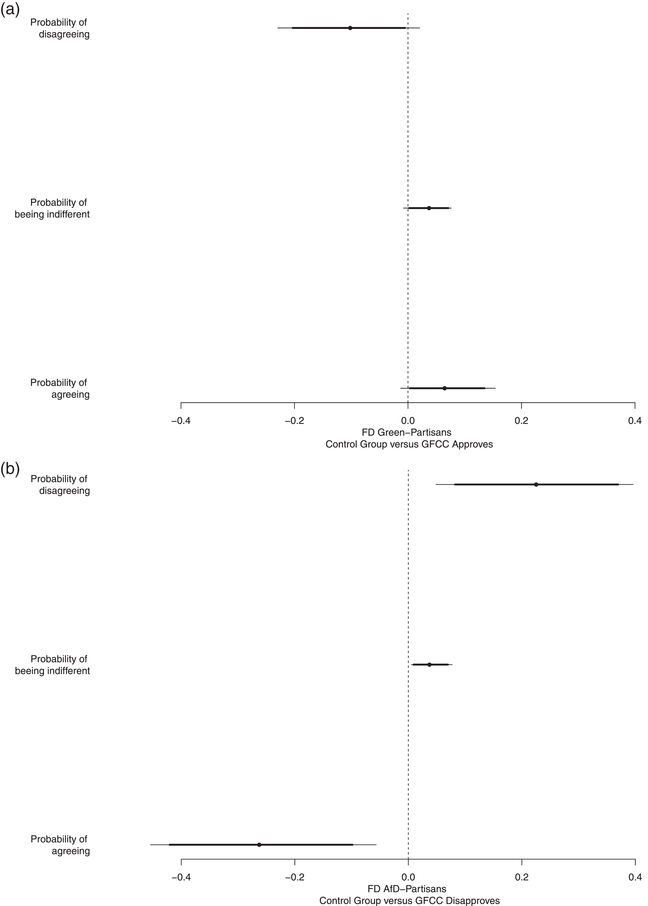

Figure 2 reports the ordered probit results from both countries. The respective regression tables are in the online Appendix. For Germany, there is a statistically significant effectFootnote 12 of both GFCC endorsements. This means that compared with the control group, the GFCC approving or disapproving the school security law leads to a positive or negative, statistically significant change in public opinion. This is exactly what Hypothesis 1 predicts: due to its reputation as a credible and legitimate interpreter of the constitution, the GFCC is able to confer legitimacy by placing its stamp of approval or disapproval on the governmental policy.

Figure 2. (A and B) Ordered probit regression results of survey experiments in Germany and France

Note: This figure shows the estimates of the ordered probit regression for the survey experiment in both Germany and France. The points represent the ordered probit point estimates and the thin and thick bars represent 95 and 90 per cent confidence intervals. See online Appendix for the regression tables.

The German national expert bodies do not have the same legitimacy‐conferring capacity as the GFCC. If the Data Security Official approves or disapproves the governmental policy, we observe a shift of public opinion in the corresponding direction, although these effects are not statistically significant. With respect to the Conference of the Ministers of Education, we see that both coefficients are negative, indicating that respondents dislike the school security law independent of whether the Minister of Education approves or disapproves this policy. However, only the coefficient for the Minister of Education disapproving the law is statistically significant. In summary, the survey experiment in Germany shows that an endorsement by the GFCC indeed leads to public opinion moving in the corresponding direction.

In the analysis of the French experiment, both CC treatment coefficients show the expected direction, although neither coefficient is statistically significant (p > 0.10) compared to our baseline (no endorsement). Nevertheless, the first differences between both coefficients are statistically significant as we can see from Figure 3 in the Appendix. Therefore, an endorsement of the CC does lead to less change in public opinion in either direction. Again, this is exactly what Hypothesis 1 predicts: if a constitutional court has a lower level of trust (such as the CC), then we should observe a weaker movement of public opinion and thus there are weaker endorsement effects. With respect to the Haut Conseil de l’Éducation, there is a statistically significant positive effect for the Haut Conseil approving the school security law, but no significant effect for the Haut Conseil disapproving a law. This is an interesting finding as it suggests that the Haut Conseil at least partially occupies a stronger legitimacy‐conferring capacity than the CC. In summary, the survey experiments show that the French court does not possess the same legitimacy‐conferring capacity as the German court, even though the direction of the expected change is correct for the French court as well. In order to evaluate the substantive relevance of the results, we calculate quantities of interests using simulations and Zelig (King et al., Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000; Venables & Ripley, Reference Venables, Ripley, Choirat, Gandrud, Honaker, Imai, King and Lau2012). This allows us to provide substantial interpretations of the effect magnitudes.Footnote 13 We only present results for the German analysis. The simulations using the French data confirmed that there is no statistically significant legitimacy‐conferring effect of the CC. We use the first differences between the control group and the respective treatment groups to visualize our findings.Footnote 14 We provide an additional result visualization in the form of commonly‐employed ‘ternary plots’ (King et al., Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000, 358) in the online Appendix.

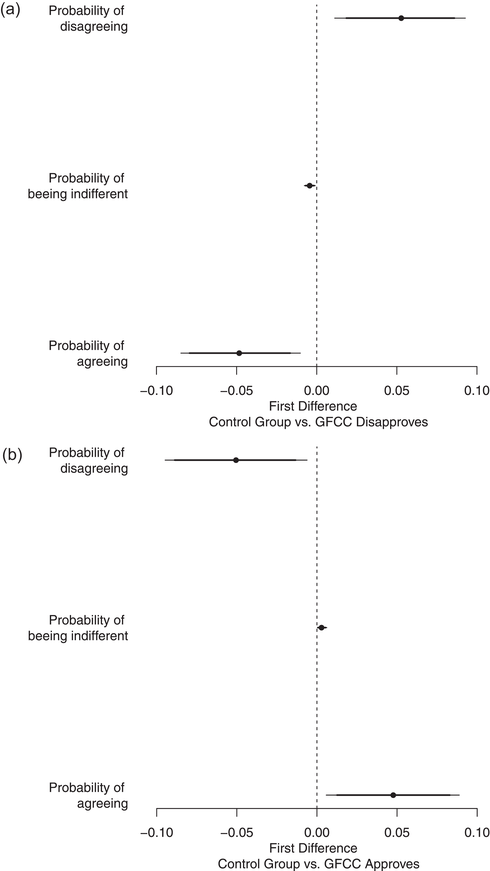

Figure 3. A and B. First difference of control group and ‘GFCC disapproves/approves’ treatment groups

Note: First differences between the simulated predicted probabilities of the control group and the ‘GFCC disapproves/approves’ treatment group. Number of simulation = 1,000. The thin and thick bars represent 95 and 90 per cent confidence intervals, respectively. The points represent the first difference point estimates. Simulations are based on the ordered probit models in the online Appendix.

The simulation results in Figure 3 show that the GFCC approval or disapproval leads to a statistically significant movement in public opinion. Respondents who received the treatment that the GFCC disapproves the school security law have on average a 5 (± 0.1) percentage‐point higher probability of disagreeing with the school security law than respondents in the control group (changing from an average 52 per cent predicted probability of disagreeing with the school security law in the control group to an average 57 per cent predicted probability of disagreeing in the ‘GFCC disapproves’ treatment group). Likewise, respondents who received the treatment that the GFCC approves the school security law have on average a 5 (± 0.2) percentage‐point higher probability of agreeing with the school security law (changing from a predicted probability of an average 34 per cent of agreeing in the control group to an average 39 per cent a predicted probability of agreeing in the ‘GFCC approves’ treatment group). All first differences of these effects are significantly different from zero at the 95 per cent level.

This five percentage‐point movement in both directions is a substantial change for three reasons. First, although the absolute change seems small, it reflects the aggregate change in opinion. Previous studies demonstrate that it is difficult to detect an aggregate change in opinion because issue polarization can lead to different sub‐groups of the sample moving in different directions, thus cancelling out the overall effect (see Christenson & Glick, Reference Christenson and Glick2015). Second, most of the German respondents rather disagree with the school security law, which makes it a hard‐case scenario to test the legitimacy‐conferring capacity. Finally, our experimental manipulations only comprise one added sentence to the described case context, whereas other studies employed more profound endorsement manipulations, for example, detailed court reasonings and arguments against or in favour of the governmental policies (Hoekstra, Reference Hoekstra1995; Bartels & Mutz, Reference Bartels and Mutz2009).

In summary, the GFCC is able to move public opinion concerning governmental policies into the direction of its ruling due to its higher level of public support, whereas the CC does not possess a statistically significant legitimacy‐conferring capacity.

Pre‐existing attitudes and the court's legitimacy‐conferring capacity

In this section, we seek to investigate at the individual level whether constitutional courts have the power to overcome pre‐existing attitudes and induce opinion change even among those who are initially either strongly in favour or against the governmental policy.

Individuals do not form their opinion in a vacuum. Instead, they have pre‐existing attitudes that might lead to them supporting – or not supporting – a policy's goal. It is widely accepted that people develop their policy preferences using their party identification as a heuristic (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). We use the existence of these pre‐existing attitudes to investigate whether the GFCC's legitimacy‐conferring capacity is sufficiently strong to even change the opinion of those who hold strong prior attitudes with respect to the school security law. We expect that the rather highly trusted GFCC is able to confer legitimacy to the school security law, namely, to induce at least a ‘soft’ opinion change among those who either strongly support or oppose the governmental policy. In the same line, we expect that the French CC – a court that is not viewed particularly positively by the public – should not be able to induce such an opinion change. The hypothesis in this regard is thus as follows:

Hypothesis 2: The legitimacy‐conferring capacity of a court with a higher level of diffuse support should be sufficiently strong to move public opinion even among those who hold strong prior attitudes.

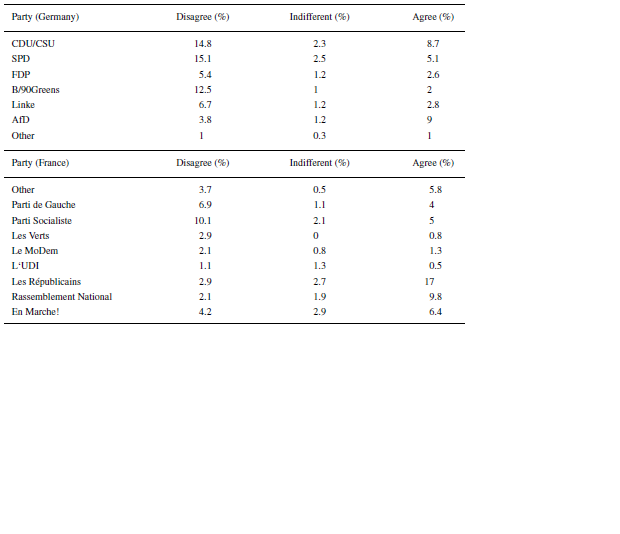

We approximate the pre‐existing attitudes of the respondents towards the school security law via their party affiliation.Footnote 15 Table 1 shows the distribution of the respondents’ opinions on the school security law over different party affiliations in Germany and France for the control group. When looking at the German respondents, we observe that partisans of the right‐wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) party are supportive towards the proposed school security law, while partisans of the Greens strongly oppose such a law. Therefore, we use AfD partisans and Green partisans to test the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the GFCC at the individual level. If the GFCC is truly perceived as a highly legitimate institution, then the treatment of the GFCC disapproving the law should shift AfD partisans towards more disagreement. Conversely, the approving treatment should shift Green voters towards more agreement. This would provide additional evidence in favour of the strong legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the GFCC.

Table 1. Support for the school security law according to partisanship in Germany and France in percent of survey respondents

Note: This table shows the distribution of the support for the school security law according to partisanship in Germany and France for the control group. For example, in Germany, there are 14.8 per cent of the respondents that disagree with the school security law and are close to the CDU‐CSU.

When looking at the French respondents, we observe that partisans of the right‐wing Front NationalFootnote 16 (National Front) and the Republicans (Les Républicains) exhibit strong support for the school security law, while partisans of the Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste) oppose such a policy. However, in contrast to the GFCC, we do not expect that a ruling of the CC leads to these partisans shifting their opinion in direction of the ruling, due to the lower public support and institutional legitimacy of the CC. In order to test these implications, we run additional ordered probit models where we include an interaction between the experimental groups and the party affiliation. Our online Appendix provides the corresponding regression tables.

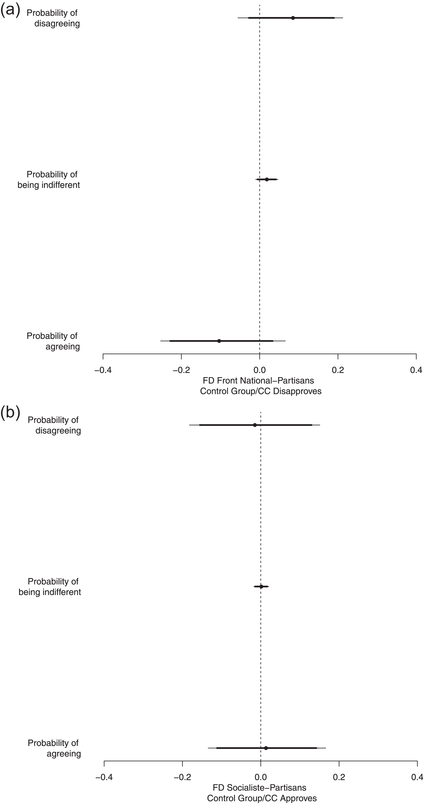

Simulations are used again to provide a substantial interpretation of the results. The left side of Figure 4 plots the first differences of the predicted probabilities for Green partisans in the control group and Green partisans who received the endorsement that the GFCC approves the school security law. We find that Green partisans have a 20 percentage‐point higher probability of disagreeing with the school security law than non‐Green partisans, simply looking at the results of the baseline model (not included in the graph). Nonetheless, Green partisans’ opinions are affected by the court's ruling: A Green partisan in the control group has an 80% (±.4) probability of disagreeing with the school security law, although this probability decreases by about 8 (±.8) percentage points on average when a Green partisan receives the endorsement that the GFCC approves the school security law. This first difference is statistically significant at the 90% level.

Figure 4. A and B. Effect of GFCC treatment on partisans of the AfD and Greens.

The same effect is also observable for AfD partisans, albeit in the opposite direction (right side of Figure 4). An AfD partisan in the control group has a 65 per cent (±.5) probability of agreeing with the school security law. However, this changes when AfD partisans are exposed to the treatment where the GFCC disapproves the law. When receiving the treatment that the GFCC disapproves the law, the probability of disagreeing with the school security law increases by about 15 (±.7) percentage points on average. This first difference is statistically significant at the 95 per cent level.

We conduct a similar analysis for the CC looking at respondents who are affiliated to the Front National and the Socialists. The results are displayed in Figure 5. As expected, neither partisans of the Socialist Party nor the National Front are affected by the CC ruling. This means that in contrast to the GFCC, the French constitutional court does not possess sufficient legitimating power to move respondents with strong prior attitudes in the direction of its decisions.

Figure 5. A and B. Effect of CC treatment on partisans of the Socialist Party and the Front National

Note: Figures 4 and 5 show the effect of court endorsement on voters of the Greens and AfD in Germany and the Socialist Party and the Front National in France. The first differences are calculated based on a simulation with N = 1,000 draws. The first difference on the left is the difference in the predicted probabilities of a Green/Socialist Party voter in the control group and the ‘court approves’ treatment group. The first difference on the right is the difference between an AfD/Front National voter in the control group and the ‘court disapproves’ treatment group. The points represent the first difference point estimates and the thin and thick bars represent 95 and 90 per cent confidence intervals, respectively. The regression tables are in the online Appendix.

Our analyses show that the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the GFCC is sufficiently strong to even overcome strong pre‐existing attitudes of individuals at the micro level. The German court is capable of shifting individuals’ positions in the direction of its decision, even if they initially have diverging preferences. This is particularly strong evidence in favour of the perception of the GFCC as a legitimacy‐conferring institution.

Individual institutional trust and the court's legitimacy‐conferring capacity

We have argued that the differences observed in the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of the German and French constitutional courts are due to varying degrees of public support. We documented the different levels of public support by means of the institutional trust of respondents in Figure 1, and showed that the GFCC is in fact considerably more trusted than the French CC. Following this argument, we develop an additional hypothesis that aims to disentangle the relationship of public support and the court's legitimacy‐conferring capacity in further detail.

If the differences in the legitimacy‐conferring capacity between the two courts are due to different levels of institutional trust, respondents with lower levels of institutional trust should not perceive the respective court as a legitimate actor. Therefore, the institutional endorsement should not or only weakly affect such respondents, independent of whether the endorsing institution is the French or German court. By contrast, someone who trusts the court also perceives it as legitimate and is therefore expected to be affected by its ruling. The hypothesis is thus as follows:

Hypothesis 3: Respondents with a higher level of trust in a court should have a higher probability of following the court decision than those with only a lower level of trust.

If it is truly institutional trust and resulting legitimacy that decides about the efficiency of the court approving or disapproving a policy, then respondents with a higher level of trust in the respective court should have a higher probability of following the court ruling than those with lower levels of trust, independent of whether they are German or French. In other words, if two respondents – one with a higher level of trust and one with a lower level of trust – are exposed to a court ruling, then the ruling should affect the respondent with higher trust more strongly than the respondent with lower trust.

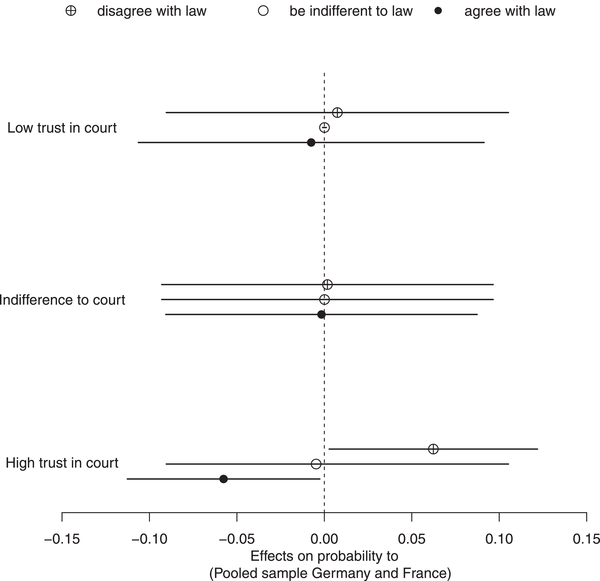

This argument is tested by looking at the effect of the disapproval treatment according to the respondents’ level of trust in the court.Footnote 17 If trust plays an important role beyond country‐specific differences, we should observe significant differences conditional on trust. In particular, the effect of the treatment should be higher among respondents with higher levels of trust and it should increase the probability of disagreeing with the school security law (because this is the direction of the treatment).

Figure 6 shows the average marginal effect of the disagreement treatment conditional on trust levels. The disagreement treatment only has a significant effect among those who have confidence in the courtFootnote 18. Respondents who have high trust in the GFCC or the CC have on average a 6 percentage‐point higher probability of disagreeing with the school security law when exposed to the treatment. Conversely, the disagreement treatment is associated with a 6 percentage‐point decrease in the average marginal effect of agreeing with the school security law. This conditional effect of trust holds even when controlling for the direct effects of ideology, trust and national context. The analyses of the interaction between the disagreement treatment and varying levels of trust at the individual level confirm that institutional trust is a key factor shaping the court's legitimacy‐conferring capacity. It also leads to the conclusion, that the system‐level differences between Germany and France are explained by the fact that fewer French respondents trust or strongly trust the court than in Germany.

Figure 6. Average conditional marginal effects of disagreement treatment conditional on trust level

Note: Pooled data for Germany and France. Average conditional marginal effects of the disagreeing court decision treatment on the (dis)agreement with the new school security law conditional on trust levels. Trust was recoded at three levels (low trust = 1, 2, 3; indifferent = 4; high trust = 5, 6, 7). The bars represent the 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Test of model assumptions and robustness checks

In this section, we report five different robustness and diagnostic tests. In the first robustness test, we check whether the joint estimation of both GIP waves (November 2016 and January 2017) affects the robustness of our results (see Tables 9–11 in the online Appendix). Using only the data of Wave 26, the coefficient for the ‘GFCC disapproves’ treatment is barely not statistically significant (p = 0.14), and in Wave 27 the FCC approves endorsement is not quite significant (p = 0.11). This is due to the larger standard errors resulting from the reduced sample size. All other effects are similar to the aggregated analysis. The same can be seen in a pooled analysis and a dummy variable for the wave.

For the second diagnostic test, we explore the effect of potential individual heterogeneity. Previous research shows that with respect to an individual's legitimacy perception, knowledge about the constitutional court can introduce heterogeneity (Sen, Reference Sen2017). If the legitimating power of the constitutional courts systematically differs depending on how knowledgeable respondents are, then an individual's knowledge should be taken into account. In order to test this, we use two questions in the surveys that measure the respondents’ knowledge about the courts. We find the same patterns as in the main analysis, independent of how knowledgeable respondents are (see Tables 14–15 of the online Appendix).

In the third robustness check, we assess whether the school security law as governmental policy presented in the experiment might alter the results. Respondents have (at least in Germany) a rather negative opinion towards such a policy. In order to test whether the findings are dependent on the choice of governmental policy, a similar experiment was implemented again in Wave 16 of the ENEF, but this time another governmental policy issue was chosen (a potential increase in the retirement age). Using this data, we are able to replicate our findings from the initial experiments: even when considering a different policy, the French CC has no legitimacy‐conferring capacity (see Table 8).

In the fourth robustness test, we replicate the main analyses again, but this time we use the original five‐point scale of the respondents’ opinions on the school security law as the dependent variable instead of the recoded three‐point scale (see Tables 12–13 in the online Appendix). Using the original five‐point scale does not alter the results. In fact, in the German analysis the effects become stronger.

In the final robustness check, we evaluate whether people's trust in court rating might be affected by the treatment group to which they were assigned (see Tables 16–17 in the online Appendix). This could be possible because the trust rating in the GIP was asked after the experimental manipulation in the form of the institutional endorsement. If the treatment and the trust rating are not independent, then the previous analyses would suffer from the problem of endogeneity. However, t‐tests of the trust rating individuals in each experimental group provide insignificant results. This shows that there are no statistically significant differences in the trust ratings of respondents receiving different institutional endorsements.

Conclusion

In this study, we have tackled the question of whether constitutional courts can change public opinion by endorsing a certain policy position. Scholars have long debated whether courts have a legitimacy‐conferring capacity and can move public opinion by placing their stamp of approval or disapproval on a certain public policy (Baird & Javeline, Reference Baird and Javeline2007; Bartels & Mutz, Reference Bartels and Mutz2009; Clawson & Kegler, Reference Clawson and Kegler2001; Gonzalez‐Ocantos & Dinas, Reference Gonzalez‐Ocantos and Dinas2019; Hoekstra, Reference Hoekstra1995), with mixed evidence. We argue that specifying the conditions under which one should expect opinion changes is more complex than previously thought.

Our comparative survey experiments on a fictitious but plausible school security law were conducted in Germany and France and embedded in national electoral surveys with more than 2,600 respondents in each country. The results demonstrate that the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of constitutional courts is highly dependent on their institutional reputation and thus their legitimacy.

The GFCC – a court that enjoys considerably high public support – is capable of moving public opinion in the direction of its decisions by legitimizing and de‐legitimizing it. This effect is so powerful that even respondents with strong pre‐existing attitudes are affected. In Germany, Green partisans are willing to accept conservative policies if supported by the court, and AfD partisans accept liberal policies if the courts support them. By contrast, the French CC is less trusted, and the effects are weak even if it also proceeds in the expected direction. However, and this point is important, the differences on the system level are driven by citizens’ attitudes towards the court on the individual level: in both countries, respondents with a higher level of trust in the court react significantly more strongly to court rulings than respondents with a lower level of trust. In Germany, far more citizens have a higher trust in the court and thus the legitimacy‐conferring effect is higher than in France. Legitimacy‐conferring also works in two directions: courts with a strong support base can legitimize a policy but also de‐legitimize it.

These findings have important implications for both our understanding of the role of constitutional courts in democratic politics and public opinion formation in general. What is known from the US Supreme Court (Bartels & Mutz, Reference Bartels and Mutz2009; Clawson & Kegler, Reference Clawson and Kegler2001; Hoekstra, Reference Hoekstra1995) does not hold unconditionally for all European constitutional courts. The legitimacy‐conferring capacity of courts is highly dependent on their institutional legitimacy and thus their diffuse support. This aspect should be considered within the concept of comparative politics.

Our work also opens up new avenues for further research. First, previous research on European courts has mainly focused on the limitations of courts in separation‐of‐powers games, namely how public opinion may shape courts’ decision making (Brouard, Reference Brouard2009; Staton and Vanberg, 2008; Sternberg et al., Reference Staton and Vanberg2015; Vanberg, Reference Vanberg2005). Our research shows that there is also a theoretical need to understand the opposite direction. Second, because survey experiments are often criticized with respect to their external validity, it is necessary that additional studies confirm the experimental evidence with observational data; for instance, from a panel where respondents are asked before and after a landmark decision takes place outside the US Supreme Court (Christenson & Glick, Reference Christenson and Glick2018). Furthermore, future studies should take into account different salient and non‐salient public policies, the role of the media as a mediator of how the public learns about a decision, or how individuals form their attitudes when they have access to competing arguments. Also, a stronger focus should be laid on the directions of legitimacy‐conferring (legitimizing and de‐legitimizing), the effect strengths and reasons for possible variation. Finally, recent events in Eastern Europe have shown that trust in courts may be less stable than originally assumed: in the Hungarian case, it quickly evaporated. Further research is therefore required to disentangle the causal mechanisms of how public support and institutional legitimacy translate into the legitimacy‐conferring capacity of constitutional courts.

Acknowledgement

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material