This is a book about fiscal policy, collective security, and Renaissance English literature. The authors taken up here – Thomas More, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, George Herbert, and John Milton – were attuned to the way sovereign authority, especially rulers’ obligation to defend the realm, hinged on the ability to raise revenue. These authors were also aware of the ways fiscal action could destabilize rule, how in extreme cases sovereign claims on subjects’ wealth or the uses to which sovereigns put their revenue could become a source of political and geopolitical instability. Fiscal controversy in the works addressed here affords opportunities to examine sovereign authority, its scope, its obligations, and its limits. Attention to the challenges and risks of implementing sovereignty also provides these writers a way to reflect on collective life by foregrounding struggles over how to define collective wellbeing, how to understand collective belonging and obligation, and how to determine who and what should be protected.

In contemporary Western democracies, one of the dominant ways people embrace or resist governmental policies and programs is through arguments about taxation. In the United States, at least, anti-tax activists intent on rolling back the welfare state policies developed over the course of the twentieth century are among the most strident voices in public discourse. However, despite the fact that these latter perspectives are the ones that have been most amplified across a variety of media, such “state phobia” is only one perspective among many about the highly consequential, practical realities of funding governmental activity that make up the quotidian work of governing.1 It is through the largely mundane work of policy makers, administrators, federal, regional, state, and local officials, advisory boards, citizen panels, and the like, that fiscal policy shapes our lives. Taxes provide the resources needed to build and maintain the infrastructures that structure daily life, to fund agencies and programs across all levels of government, and to implement the social safety nets that support at least some of the most vulnerable. Fiscal policy materially determines what governments can and cannot do. Funding decisions effectively select which understandings of collective life come to be implemented, define what values and visions can be realized, and determine who and what should be supported and preserved. Debates about fiscal policy – be they polemical or technical – constitute sites of consensus about or struggle over what kind of world governments should strive to bring into being and protect. In this sense, fiscal policy is a form of worldmaking.

To be sure, fiscal controversy and struggle in early modern England differ significantly from the current polemics surrounding taxation. Arguments about taxation in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England refer to distinctly different issues and structures of authority than do the policy discussions or polemic of the last several decades. Nevertheless, the authors addressed in the chapters here acknowledge the worldmaking potential of fiscal action. Then, as now, debates about how to fund rule constitute important sites for wrestling with the question Michel Foucault locates at the center of governmental reflection: “How are we to be governed?”2 Throughout the period in England, collective security served as the primary justification authorizing sovereigns to request – and for parliaments to grant – taxes. Consequently, inquiry into, advocacy for, debate about, or challenges to taxation represent important places where sovereignty as a structure of authority and security as a practical objective come to be defined, affirmed or contested. More, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton all broach concerns about fiscal policy by way of exploring questions about how to define security, about the scope and limits of governance, about the nature of political community, and about the relation between political and geopolitical scales of action. By creatively reflecting on the worldmaking potentials of fiscal policy, these authors draw on the substantially different resources for literary worldmaking. Their works explore the affordances of imaginative writing for gathering provisional communities of readers or playgoers through representing the challenges of implementing sovereignty.

A preliminary gauge of the centrality of fiscal concerns to the project of governing security can be found, albeit in highly polemical form, in Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan. Writing in the aftermath of the English Civil War, a conflict (as noted in Chapter 6) fueled in large measure by resistance to Charles I’s perceived fiscal aggression, Hobbes singled out the resistance to taxation as perhaps the greatest challenge facing any sovereign. The problem is not any real harm rulers cause by taxing their people, “the dammage, or weakening of their Subjects,” but the perceived sense that taxation constitutes a form of harm.3 As Hobbes explains, “the greatest pressure of Soveraign Governours” derives from:

the restiveness of themselves, that unwillingly contributing to their own defence, make it necessary for their Governours to draw from them what they can in time of Peace, that they may have means on any emergent occasion, or sudden need, to resist, or take advantage on their Enemies. For all men are by nature provided of notable multiplying glasses, (that is their Passions and Self-love,) through which, every little payment appeareth a great grievance; but are destitute of those prospective glasses, (namely Morall and Civill Science,) to see a farre off the miseries that hang over them, and cannot without such payments be avoyded.4

Hobbes’s immediate argument is about peacetime taxation, which, for reasons I discuss here, represents a significant and highly contested change to the basic rationales for Parliamentary taxation in the period.5 But the passage quickly moves from the particular issue of levying taxes when the country is not at war to more abstract insights about the nature of humankind and the foundations of sovereignty as such. Hobbes understands security to be the primary motivation for the contract that forms the sovereign. Safety, the primary justification for sovereignty, functions as both a normative framework for understanding the work of rule and as an imperative obligating obedience to the sovereign.6 Consequently, within the framework Leviathan develops, resistance to taxation constitutes a profound challenge to sovereignty as such, since a sovereign without the resources needed to provide security cannot be said to be a sovereign at all.7 What is so frustrating to Hobbes – and to many rulers and their adherents in the period – is that people develop ideas about security that differ from those of their sovereign. The irony of this fact is that once the sovereign has been formed, the peace and security the sovereign provides obscures the reasons why a sovereign might need emergency funding to maintain peace and security. Resistance to taxation tacitly challenges the sovereign security imaginary. If people shared the sovereign’s understanding of security and assessment of potential “miseries” – if they themselves felt threatened – they would readily provide the resources needed for collective security. The sovereign was created to escape the existential precarity of the “solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short” (186) life in the state of nature as Hobbes describes it. Such an agreement implicitly obligated subjects to provide the resources needed to implement such security. But, feeling safe, people resist paying taxes because they don’t see the dangers the sovereign sees. And because they don’t perceive the world the way the sovereign does, because they disagree with the ruler’s judgment about what constitutes a threat, the effort to fund security itself becomes the threat, a “great grievance” that makes people feel attacked, vulnerable, less secure.

Though the whole point of the passage is to demonstrate what he considered to be the nonsensical and ultimately self-destructive nature of fiscal debate, Hobbes’s discussion of fiscal controversy identifies a crucial aspect of security as a concept and governmental objective, that is, its perspectival nature. To be sure, the way Hobbes characterizes such perspectival difference strives to privilege the sovereign’s ability to discern the “miseries” approaching the polity that require access to the people’s wealth to address. Lacking the sovereign’s epistemologically privileged perspective provided by “Morall and Civill” science, the people see through the “multiplying glasses” of passion and self-interest that skew how they view the world and prevent them from comprehending potential harms facing the polity. Without the aid of the sovereign’s superior “prospective glasses,” people see no reason to provide the sovereign with the resources needed for collective safety and wellbeing. Hobbes’s scorn notwithstanding, the very fact of difference about whether a threat exists suggests the definitional openness of security. The authors taken up here all understand security to be a dialogic phenomenon, a multivalent concept, always embedded in specific contexts, and thus always dynamically interacting with other ways of understanding and inhabiting the world.8 One person’s security can become another person’s vulnerability. Efforts to guarantee the safety of some can render other peoples’ lives insecure.9 Such an insight arises most immediately in Raphael Hythlodaeus’s sharp polemic against Western Europe’s leaders in More’s Utopia and runs throughout each of the chapters within. Securitization, to use a privileged term in the field of Critical Security Studies, is less a singular, top-down, decisive speech act through which matters of security come to be constituted as such, and more of an open-ended question.10 Constituting a state of affairs as a matter of security is a multi-faceted process, a concern and series of ongoing practices dispersed across many domains, operating by multiple logics, and forming the site of conceptual debate, public and private conflict, struggle, compromise and invention.

Because of this definitional openness, that is, because people frequently see the world in different ways and thus have different ideas about what it means to be secure, about who is responsible for providing security, about the best way to secure this or that aspect of existence, the question of how to fund security can always become difficult, even conflictual. The capaciousness and slipperiness of security as a concept in turn renders fiscal policy in the period (and beyond) an always potentially fraught phenomenon. The effort to fund government can be viewed as either vital to collective wellbeing or as itself a threat. Every ruler during the period, like perhaps almost every sovereign who has ever ruled, had to confront the challenges of gathering the financial means needed to implement their decisions and designs. And at one point or another every ruler in the sixteenth- and seventeenth-centuries faced what David Harris Sacks calls the “paradox of taxation,” the idea that taxes are both vital and potentially harmful, both necessary for fulfilling the imperative to protect the people from threats at home and abroad, and a source of conflict when fiscal burdens came to seem too great.11 In extreme circumstances, the demand to pay for this or that version of security can become controversial, can spur debate, can drive challenges to sovereign or parliamentary authority, can prompt people to question, protest, or even rise up against their leaders.

To highlight how uncertainty about security underpins and drives the paradoxical nature of taxes in early modern England, and by way of characterizing the extreme circumstances to which the authors taken up in this study are drawn, I understand the challenge Hobbes and many others confront as a fiscal security dilemma. In the field of International Relations, a security dilemma generally describes a situation in which one group’s efforts to protect itself or its interests actually create fear in others, and, as a result, prompt greater systemic volatility and vulnerability. Defensive actions by one entity look like threats to others. John H. Herz, provides a canonical account of the phenomenon, arising from group interaction on a heterogeneous and anarchic terrain:

Groups or individuals living in such a constellation must be, and usually are, concerned about their security from being attacked, subjected, dominated, or annihilated by other groups and individuals. Striving to attain security from such attack, they are driven to acquire more and more power in order to escape the impact of the power of others. This, in turn, renders the others more insecure and compels them to prepare for the worst. Since none can ever feel entirely secure in such a world of competing units, power competition ensues, and the vicious circle of security and power accumulation is on.12

Efforts to create security paradoxically generate insecurity, make life seem less safe for the entity striving to protect itself and for the system as a whole. The concept of the security dilemma was developed as a framework for understanding geopolitical realities during the Cold War, and so the emphasis is on relations between nations, an emphasis which is relevant to the present study. Nevertheless, the effort to theorize interstate rivalries occludes how security conflicts relate to internal political struggles and the complex interplay between internal and external scales of action, especially, for present purposes, the fiscal dimensions of security. In this sense, though Hobbes’s work is central to the realist tradition within International Relations theory to which Herz contributes, Hobbes’s analysis provides a kind of corrective to or supplement to Herz’s account by virtue of its awareness of the security struggles internal to the polity.

Though Hobbes’s response to fiscal controversy represents just one effort to solve the fiscal security dilemma, his brief statement outlines the basic structure of the phenomenon addressed in the chapters that follow. The fiscal security dilemma traced here works like this: The primary justification for taxes in the period was to provide the resources needed to defend the realm from its foreign and domestic enemies. But because security is a perspectival phenomenon, efforts to gather the funds necessary to implement security could come to feel more harmful than the putative risk, a burdensome imposition threatening people’s livelihoods. Under such circumstances, protection could feel like predation. From the perspectives of England’s rulers, people’s sense of security – etymologically the state of being sine cura, without care – could itself be a risk, a dangerous complacency that that could endanger the polity, especially if such complacency created resistance to fiscal policy.13 From subjects’ perspective, if taxes became too burdensome – and what constitutes an excessive tax is always a matter of interpretation and debate – efforts to fund security can create resistance to sovereignty. Questions about or struggle over fiscal policy create possibilities for scrutinizing sovereign actions, for challenging definitions of sovereignty, or for offering opposing perspectives about how to define and secure collective wellbeing. Taxes are constitutive of political and geopolitical life, defining mutual obligations and reciprocity between sovereign and subject and shaping relations between sovereigns and nonsovereign agents on an international terrain. For much of the period covered by this book, Parliament complied with royal requests for fiscal assessments, most subjects paid their taxes, and sovereigns at least attempted to fulfill their basic obligations. But at times, taxes could become a site of significant strain, a flashpoint, a potentially volatile site of difference, critique and, on occasion, passive or active resistance.

What follows addresses the work of authors responsive to the always potentially fraught relationship between fiscal policy and matters of collective security and wellbeing. Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine plays, The Jew of Malta, and A Massacre at Paris, William Shakespeare’s history plays, George Herbert’s Country Parson and The Temple, and John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained, and Samson Agonistes, to name the works that figure most centrally in this study, each explore how questions of funding security are linked to some of the primary constitutive tensions that define political community in the English Renaissance. Struggles over funding security are struggles over how to define security. Such struggles provide More, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton, among many others, with a means to see, to think about, and to examine important questions and controversies that define and challenge the terms of collective belonging: What defines security? What does it mean to lead a safe life? What criteria are being used to identify and assess security threats? How is security to be implemented? Whose interests should be secured? Whose interests can be sacrificed? Who is left out of any given definition of security? If people perceive taxes to be too onerous, as the English populace did with some frequency across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, these questions become urgent sources of concern. Fiscal policies are vital for collective security, though they are also always potentially a site of profound resentment, anger, or outright conflict. This study takes up a set of works that understand these governmental realities to be central to the ongoing process of making communal life on volatile political and geopolitical landscapes. More, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Herbert, Milton, and many others, are intensely attuned to questions of security, wealth, and fiscal policy as primary bases of collective life and potential sources of antagonism in the polity. In addressing such administrative concerns, the authors examined here think about the nature of community. They also strive performatively to create communities. Addressing their audiences about the challenges of implementing sovereignty, these authors assemble provisional communities of readers and theater goers through the very process of creatively depicting alternative, improvisational, forms of collective life. What follows is thus a study of how a group of Renaissance authors used questions about funding security as an occasion for literary worldmaking.

Funding Sovereignty

How was sovereignty funded in early modern England?14 This is a complicated question and such complexity was itself frequently a source of confusion and conflict. Nevertheless, following the precedent of such writers as Sir John Fortescue, historians frequently distinguish between “ordinary” and “extraordinary” sources of revenue in the period. Generally speaking, ordinary revenues were those associated with the royal demesne and with returns deriving from a host of feudal rights and privileges attached to the monarch: “income from royal lands, the prerogative rights of the king as feudal overlord, fiscal prerogatives [such as the right to mint and regulate coinage], and the profits of justice.”15 The basic assumption was that such revenues would be adequate for the monarch to fulfill the obligations of office, the charges associated with administering justice and providing for the safety and wellbeing of the people. However, in “extraordinary” circumstances of urgent need English monarchs could appeal to Parliament for supplemental funding through taxes. Such taxes could take any of a number of forms: “both direct (parliamentary subsidies, fifteenths and tenths, etc …) and indirect (the customs and subsidies on wool, tunnage and poundage).”16 These latter extraordinary taxes were understood to be more or less emergency provisions for purposes of collective security understood primarily in terms of military preparedness or military conflict.17 Funding sovereignty – managing the available ordinary and extraordinary fiscal resources – was a complex and ongoing challenge involving tremendous administrative effort, specialized legal institutions, ongoing negotiation with Parliament, and considerable ingenuity. To be sure, there was significant continuity with earlier periods: the Exchequer as an institution had existed since at least the Norman Conquest;18 rates for fifteenths and tenths paid by individual communities had been established by statute in 1334; and procedures for collecting taxes and auditing the work of tax collectors were relatively stable across the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Nevertheless, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries also witnessed significant transformations in the kingdom’s fiscal infrastructure, shifts and innovations that expanded the efficacy and reach of this infrastructure, both in absolute terms of the amount of money that could be raised, and in terms of the legitimacy and efficiency of the fiscal bureaucracy.19 Such shifts and innovations dramatically transformed the nature of state power by expanding “state capacity” in the period in ways that, as described here, augmented England’s military infrastructure and hence its geopolitical standing and agency.20 But, much to Hobbes’s eventual dismay, such developments could also prompt intense questioning, passive resistance through manipulating assessments of individuals’ wealth or various strategies of tax avoidance, struggle at local and national levels, legal challenges, and, at times, most spectacularly as with the English Civil War, open conflict.

Attention to how sovereignty is funded defines an expansive field of inquiry, encompassing a host of questions central to struggles over the scope and nature of royal authority. Inquiry into fiscal policy in the period, for instance, encompasses concerns about the organization of the royal household, demesne management, monetary policy, royal access to international credit markets, monarchical rights to buy provisions at set prices, royal supervision of wards, to name only a few key concerns. With the exception of the chapter on Herbert (Chapter 5), which takes as its point of departure a related set of questions that pertain to funding security at the parish level, the primary emphasis of what follows is on the affordances and controversies that accompany efforts to fund sovereignty through direct taxation of subjects and in relation to the collective security of the realm. Such controversies implicitly beg the question of the scope and nature of royal authority and thereby represent a site at which the scope and nature of political agency comes to be defined, asserted, and explored.

Emphasizing the fiscal dimensions of collective security thus complicates the influential account of sovereignty advanced by Carl Schmitt, especially as developed by Giorgio Agamben, an approach that generally ignores questions about, and struggles over, how sovereign authority is implemented.21 The defining aspect of sovereignty for these authors is the capacity for extra-legal action in the face of existential threat. Such a definition has the effect of orienting sovereignty around the scene and temporality of decision – the decision about when an existential threat exists, and thus about when to suspend the law in order to preserve the polity. However valid may be such an account of sovereignty, however much the power to decide defines sovereignty as a phenomenon, the moment of decision is only one aspect of the complex process of implementing security. Sovereignty, as Julie Stone Peters argues, is an “assertion.”22 The practical reality of implementing such assertions highlights the contingent nature of sovereign authority. The efficacy of the kind of decisions Schmitt and Agamben privilege depends on circumstances, institutions, conceptual frameworks, forms of agency, and resources that condition the possibility of sovereign decisions and implementation and that are not entirely within the purview of sovereign agency.23 With respect to the questions of fiscal policy raised here we can say that making a decision is one thing; paying to implement that decision is quite another matter altogether. Margaret Levy has observed that historically “[d]ebate about what constituted sovereignty was also a debate about taxation.”24 Implied in Levy’s formulation is a corollary sense that debate about taxation is implicitly a debate about sovereignty. Decisions are important, certainly. But the Schmittian paradigm occludes the messy realities of sovereignty on the ground – in Braden Cormac’s terms, the “mundane process of administrative distribution and management,” where rulers, legislators, and administrators face the ongoing, and no doubt frequently frustrating, challenges of raising money: assessing, collecting, recording, transporting, and storing wealth, and then putting such resources to work in the service of collective security.25 In Renaissance England, at least, and certainly elsewhere as well, the project of producing sovereignty effects on a fraught geopolitical terrain depends upon elaborate political and administrative infrastructures for requesting, approving, assessing, gathering, holding and distributing revenue.

In its departure from the Schmittian paradigm of the buck-stopping, norm-constituting sovereign decider, the present study intersects with key aspects of Ernst Kantorowicz’s still influential study, The King’s Two Bodies. In an important engagement with Kantorowicz’s work, Jennifer Rust brilliantly highlights how his analysis embeds monarchy in administrative infrastructures, legal frameworks, fiscal procedures, communal structures, and political relations that effectively regulate and thus constrain sovereign decisions.26 Following Rust’s lead we can note that Kantorowicz’s study specifically foregrounds the central role of the fisc, or royal treasury, in conceptualizing and materializing the ongoing existence of the realm over and above the life of any given ruler. Kantorowicz traces how the fisc comes to be conceived as res nullius, ownerless property, effectively belonging to all members of the realm, dedicated to the care and preservation of the people.27 Understanding the royal treasury as collective property in turn creates a potential distinction between the king and the fiscal resources belonging to all. Such a distinction identifies a point of struggle impacting the long-term development of how people understand communal belonging, secular sovereignty and state forms. Writing of the “constitutional struggles of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries” between England’s monarchs and its baronial elites, Kantorowicz observes that:

the baronial objectives were always centered on the fiscal-domanial sphere … Within the orbit of public affairs … and especially public finances, the barons could venture to control the king, to bind him to a council of their own choice, and thus to demonstrate that things of public concern no longer touched the king alone, but “touched all,” the king as well as the whole community of the realm.

Kantorowicz’s reference to early struggles over royal access to wealth highlights the significant role conflict over taxation played in the development of Parliament as an institution.28 If tax policy motivated the creation of forms of political agency through counsel and consent, such concerns also had the effect of redefining kingship in administrative and custodial terms, viewing the “king as the supra-individual administrator of a public sphere” (191), “as the guardian of the public appurtenances which served the benefits and security of the whole body politic, and were supposed to serve the polity in perpetuity – far beyond the life of the individual king” (191). The fisc, and the “security of the whole body politic” represent matters quod omnes tangit, that which touches all; and that which touches all, as the influential Roman legal maxim goes, requires the consent of all.29 Taxes and the administration of security became matters of public scrutiny, judgment, and active political involvement. Shifting the emphasis from the decisions of the sovereign decider to the mundane realities of royal administrative infrastructure, Kantorowicz highlights the constraints set on the sovereign obligation to protect the realm. So doing, he tacitly offers an alternative to Schmitt, an understanding of sovereignty defined through its politically constrained, constitutionally regulated engagement with fiscal and administrative realities.30

Though Sir John Fortescue’s fifteenth-century political reflections are not central to Kantorowicz’s argument, Fortescue’s highly influential work confirms Kantorowicz’s understanding of the practical impossibility of separating sovereignty from fiscal relationships. The understanding of taxes as a matter of collective security is central to Fortescue’s definition of England as a polity ruled both politically and royally, “dominium politicum et regale.” A ruler ruling “regale” – the French king is his privileged example – can simply appropriate his subjects’ wealth at will. By contrast, English kings are bound to respect the laws and limit their claims on people’s goods. As Fortescue asserts, “the king ruling his people politically … is not able to change the laws without the assent of his subjects nor to burden an unwilling people with strange impositions, so that, ruled by laws that they themselves desire, they freely enjoy their goods, and are despoiled neither by their own king nor any other.”31 The king’s respect for the law is linked closely to limits on taxes, which is what he means by “strange impositions.” It is as if establishing limits to the king’s ability to assess taxes is the privileged instance of the law’s efficacy, which is to say, the primary purpose of the law. To be sure, Fortescue makes a strong case for the necessity of a well-funded English monarchy. At the same time, the specter of the English people either being despoiled by their own or a foreign king reinforces the primary royal obligation to protect the people from predatory invasion. Among the most impressive aspects of Fortescue’s argument is the way he is able to recast a strong reminder of the limits of royal prerogative as in actuality the source of the real strength of the English monarchy. As he elaborates:

a king is free and powerful who is able to defend his own people against enemies alien and native, and also their goods and property, not only against the rapine of their neighbours and fellow-citizens, but against his own oppression and plunder, even though his own passions and necessities struggle for the contrary. For who can be freer and more powerful than he who is able to vanquish not only others but also himself?

Governing in a way that allows the people unimpeded use and enjoyment of their own “goods and property,” protecting his people from “his own oppression and plunder,” the English monarch fosters a prosperity that in turn reinforces collective security. Fortescue’s preferred metaphor for thinking about fiscal policy is as wages for the monarch/soldier, charged with defending the realm (100). Though the image is perhaps jarring, by figuring the kingdom’s ruler as a subordinate to the people, the conceit puts in figurative language a favorite adage Fortescue attributes to Aquinas: “the king is given for the kingdom, and not the kingdom for the king” (99). The idea of a monarch subservient to the kingdom and people – a soldier laboring for wages – brings into vivid relief Fortescue’s sense that fiscal policy, though absolutely necessary for collective wellbeing, nevertheless requires ongoing vigilance not to shade over into confiscatory predation, the monarch’s “own oppression and plunder.” Responsible fiscal policy, in accord with the administrative and custodial framework Kantorowicz describes, requires an ongoing labor of self-restraint to put the monarch in a position not only to prevent the predatory impulses that threaten the realm – “the rapine of … neighbours and fellow-citizens” – but also not to contribute to such dispossession.

“Rapit Fiscus”

Fortescue provides a strong rationale for taxation grounded in consent and mutual obligation of the ruler and the ruled. At the same time, he identifies an important tension within fiscal discourse, an awareness of the potentially difficult distinction between taxation and plunder. “[O]ppression and plunder” is precisely what one would expect from an enemy invader. More’s character Raphael Hythlodaeus echoes Fortescue’s formulation when he describes the fiscal “plunder and confiscation” that characterize contemporary Europe’s monarchs.32 Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles, a work that gives considerable attention to fiscal concerns and conflict, describes King John’s attempts to gather funds as figuratively an attack on his people: “King John being now in rest from warres with forren enimies, began to make warre with his subiects pursses at home, emptieng them by taxes and tallages, to fill his coffers.”33 Shakespeare’s John of Gaunt on his deathbed speech similarly responds to perceived aggressiveness of King Richard’s fiscal demands by lamenting “That England that was wont to conquer others / Hath made a shameful conquest of itself.”34 The idea figures centrally in the development of the myth of an ancient constitution destroyed by the so-called Norman yoke, imposed by William the Conqueror in 1066 that gains considerable purchase in seventeenth-century political controversy.35 And we can perhaps recognize in such language, an important precursor to opposition to taxation in our own moment, polemic that ranges in affective temperature from Robert Nozick’s relatively measured philosophical account of most taxes as illegitimate confiscation to the fervid outrage of (in the United States) Tea Party activists and their successors who – like the original Boston Tea Party Sons of Liberty protesting the Tea Act of 1773 – associate taxation with tyranny.36

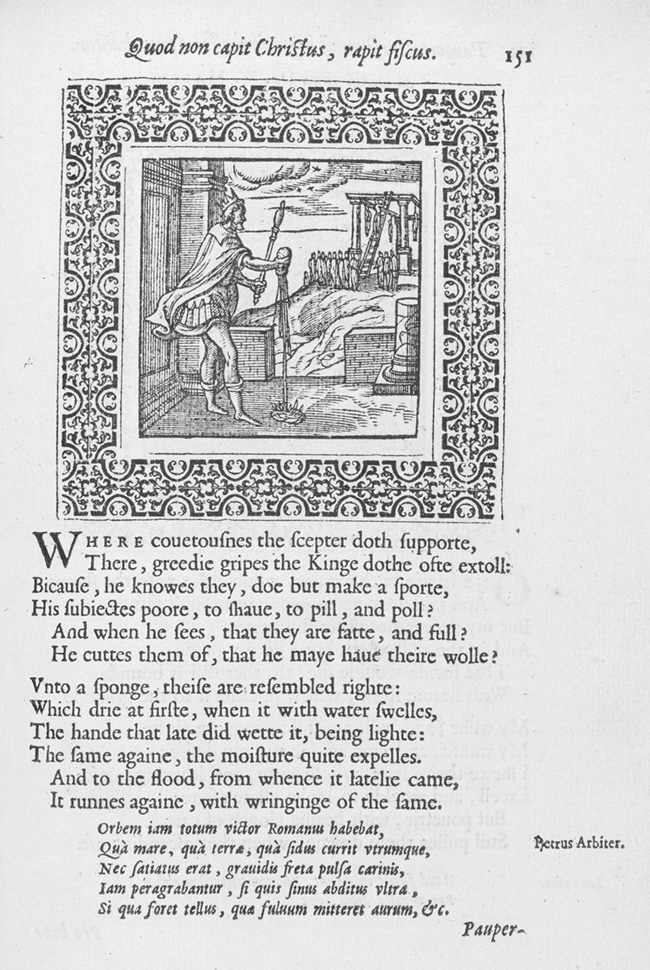

While it is difficult not to recognize the contemporary resonance of the association of taxation and tyranny, it is important to consider the historical specificity of such formulations. As noted at the outset, anti-tax activism in our current neoliberal moment has largely been a matter of wishing to roll back, if not to eliminate altogether, the welfare state institutions of “social security” developed in Western democracies during the middle decades of the twentieth century.37 By contrast, in early modern England, in an era well before the advent of liberal and subsequently welfare state governmental rationalities, concerns about fiscal policy were about the terms of mutual obligation between sovereign and subjects, the scope and limit of the sovereign’s agency, and the nature and shape of communal life. Each of these emphases in turn impact how collective security comes to be defined and implemented. The idea that monarchs are capable of “oppression and plunder” represents a significant, albeit extreme, way of responding to a given fiscal regime. The association of monarchy with fiscal predation is, nevertheless, a commonplace. Consider Figure 1.1 from Geffrey Whitney’s 1586 Choice of Emblemes, which conveniently illustrates the widely understood link between sovereignty and taxation, and, in turn, between taxation and violence.38 The engraving of a sovereign squeezing a sponge with liquid spilling on the ground provides an especially mordant illustration of an especially mordant adage: “Quod non capit Christus, rapit fiscus” – what the church does not capture the royal treasury seizes. In the background, a crowd gathers around gallows on which several bodies hang.

Figure 1.1 “Quod non capit Christus, rapit fiscus.”

Figure 1.1Long description

The illustration features the king with a scepter and sponge, with an execution scene in the background. The text discusses taxation, administrative greed and tyranny, comparing royal servants to sponges that absorb wealth before being wrung out by a rapacious monarch.

Who are – or were – the people suspended from the gibbet? The answer is not entirely clear. The poem immediately below the image, read as a warning to potential administrators excited by the lucrative opportunities of royal fiscal service, suggests that the bodies on the gallows belong to the “greedie gripes” the king employed to enact his “covetousness” – for instance, people like Edmund Dudley and Sir Richard Empson, the architects of Henry VII’s fiscal policy, executed by Henry VIII upon his accession. However, the generalized nature of the adage itself suggests that the engraving depicts the normal operation of the fiscal machinery. On such a reading, the hanging bodies belong to tax delinquents and the “couetousnes” that “the scepter doth supporte” belongs to the monarch who in the image supports the scepter in one hand as he squeezes the filled sponge with the other. Either way – if the sponge figures the royal servants gathering taxes or if the sponge represents the people being taxed – the image comprehends the fisc as a machine for violently seizing wealth. The broken column at the right of the image, with cracks extending along the pillar, provides a commentary on the long-term viability of such a fiscal regime. Similarly, the brief reference at the bottom of the page to an episode from Petronius’s Satyricon hints at catastrophic consequences to follow from the kind of fiscal rapacity the image figures. The full passage Whitney excerpts describes how the relentless and unstinting “quest for wealth” grounds and threatens Roman imperial supremacy, serves as both the motive for its expansive achievements and the means through which the Roman polity becomes corrupted by luxury, slothful indulgence, and wasteful expenditure, “the mad use of wealth” eventually leading to civil war.39

As I have suggested, though the kind of critical perspective Whitney’s version of the “rapit fiscus” emblem is extreme, the jaundiced view of fiscal policy it depicts is nevertheless, precisely in its status as a commonplace, widespread.40 Concerns about taxation, or what amounts to the same thing, complaint about the effects of efforts to raise royal revenue, forms an important component of political discourse in the period. Markku Peltonen has shown how humanist rhetorical pedagogy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in England cultivated a civic consciousness vigilant towards sovereign fiscal action; as he demonstrates, one of the things Renaissance schoolboys learned in class was how to be skeptical about sovereign claims on subjects’ wealth, instruction that fueled debate about royal fiscal policy in Parliament prior to and leading up to the House of Commons’ challenges to Charles I.41 Popular complaint also frequently drew attention to the oppressive effects of taxation. Fiscal concerns frequently played a role in popular resistance movements, from the unrest that led to King John signing the Magna Carta to the English Civil War and beyond, including a number of revolts in the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII and during the Protectorate of Edward VI.42

To be sure, critique of or resistance to fiscal policy does not make reference to a unified set of policy objectives that are consistent over time. Such efforts however do share a commitment to questioning the nature of communal belonging and obligation, to exploring and exploiting forms of collective agency, and to opening up the workings of sovereignty to collective scrutiny. If, as suggested here, fiscal policy is a form of worldmaking, a way of maintaining or bringing a world into being, the fiscal security dilemma described here acknowledges the forms of difference and dissensus that circulate around the challenges of funding security, that derive from the fact that there are fundamental disagreements about what security means, about whose security matters, and about how best to achieve a given vision of collective safety. Each of the authors addressed in this study, albeit each in his own distinctive way, broaches some version of these governmental challenges – More in his depiction of the Utopian polity as an alternative to what he characterizes as the fiscal rapacity obtaining in contemporary Europe; Marlowe in a series of tragedies centered on protagonists assembling and using treasuries to navigate the cutthroat world of geopolitical struggle; Shakespeare in his account of conflicts over fiscal policy and national security that destabilize and drive English history as he understands it; Herbert in poetry that emphasizes the profound inability to regulate the accumulation of wealth or to govern either personal or collective security; and Milton in his late poems that strive, with great difficulty, to define forms of security opposed to a post-Restoration world given over to expansive regimes of material accumulation. Each chapter shows these authors exploring what happens in moments of emergency in ways that highlight the conflicts that arise around efforts to define, fund, and implement security.

Geopolitical Horizons

Because the primary justification for extraordinary taxation in the period was for military purposes, fiscal controversy inherently implicates and impacts foreign policy. England’s foreign involvements led both to periods of intensified demands on fiscal resources – demands that generally led to periods of intensified fiscal controversy – and to profound transformations in England’s fiscal infrastructure and ability to fund war. Though such transformations are not this study’s primary focus, the circumstances and motives driving the long-term development of English fiscal and military capacities are relevant to each chapter here. It will thus be useful to sketch this historical process. The précis of the book’s chapters provided immediately above suggests the contours of this history, a dramatic rearticulation of security thought from a primarily dynastic framework (relevant to the works of More, Marlowe’s Massacre at Paris, and Shakespeare’s history plays) to primarily commercial motives (which play a role in Marlowe’s Jew of Malta, and which draw the attention and concern of Herbert and Milton). Briefly put, England’s relative disadvantage vis-à-vis European dynastic politics created the conditions for and incentives to pursue accumulation strategies organized around expanded international commerce and colonial settlement. Such strategies both required and enabled a reorganization of the nation’s fiscal policy – and capacities for waging war – around redefined notions of security and collective welfare.

The transformation sketched here involves not a dramatic rupture between political and geopolitical formations but the gradual repurposing of the available institutions and administrative competencies for new objectives. Saskia Sassen makes this point in her effort historically to contextualize and to rethink globalization as a long term process facilitated by adapting available administrative and legal infrastructures to the process of assembling “global scales of interaction.”43 With respect to the English state’s fiscal capacities – the administrative structures, political institutions, forms of record keeping and reporting, modes of expertise, and technical knowhow necessary for managing the process of funding government – we can say that such fiscal infrastructures and procedures were initially developed and adapted to a dynastic geopolitical environment that produced imperatives towards territorial expansion. According to Benno Teschke, surveying European international relations over the course of the roughly three centuries between the end of the fifteenth century and the Napoleonic wars, the absolutist form of sovereignty that prevailed on the continent “was not only domestically rapacious, it also produced a structurally aggressive, predatory, expansive foreign policy.”44 In terms I’ve been developing here, we might understand Teschke’s account as showing how “([g]eo)political strategies of accumulation” represent an effort to resolve fiscal security dilemmas in a way that responds to – and that attempts to take advantage of – the anomic and competitive nature of geopolitical relations:

To the degree that monarchs ceaselessly struggled to maintain and enhance their power bases at home against the threat of revolt, they were driven to pursue aggressive foreign policies. This allowed them to meet the territorial aspirations of their families, repay debts, satisfy the desire for social mobility of the ‘sitting’ army of officials and the ‘standing’ army of officers, and share the spoils of war with their growing networks of clients, financiers, and courtly favourites. These elites, in turn, pegged their fortunes to the royal warlord, provided he respected the absolutist historical compromise of aristocratic non-taxation, repaid his debts, and offered prospects for social promotion and geopolitical gain.45

To survive in the geopolitical environment Teschke describes, sovereigns had to augment their territorial holdings and, thus, their opportunities for ongoing extraction of wealth. Because dynastic monarchs were “domestically rapacious” they had access to the resources needed to expand. Though Teschke does not say so explicitly, it is clear that domestic rapacity would be a significant cause for the “threat of revolt” dynastic monarchs face. Securing their interests on a competitive and unstable geopolitical landscape produces deep insecurity. Where levying taxes to fund security risks creating outrage and resistance among the taxed, thereby heightening insecurity, absolutism strives to export its insecurity through plunder and territorial expansion. That is, aggressive military expansion with an eye to the accumulation of wealth and territory represents an effort to resolve the security dilemma by finding sources of revenue outside the polity. Within the system Teschke describes, dynastic actors attempt to solve the fiscal security dilemma at home by effectively exporting it, neutralizing conflict by pursuing, to borrow David Harvey’s terms, a “spatial fix” through territorial expansion.46

Given the number of geopolitical players drawn by the lure of spoil and territorial expansion and given the fact that people generally dislike being conquered, the systemic impact of such accumulation strategies is to heighten geopolitical volatility. Inter-European conflict was a more or less zero-sum game. Not every ruler who entered the arena of geopolitical conflict could succeed and whatever successes this or that leader achieved were only ever temporary. Such systemic volatility represents both an endemic challenge to rule and an opportunity, a kind of lure to geopolitical aspiration. Those English rulers lured by dynastic conflict – with a very few exceptions in its long history – existed at a competitive disadvantage geopolitically and thus largely failed to achieve the kind of material accumulation of territory and spoils drawing dynastic aspirants into geopolitical conflict. At least, More, Marlowe, and Shakespeare give voice to an awareness of the endemic volatility surrounding the geopolitical environment Teschke describes and the domestic risks associated with dynastic rivalry. To take one instance, Shakespeare’s King John, powerfully dramatizes the fiscal security dilemma I’ve been describing and speaks to such risks. Because he is strapped for cash, when John declares war on France at the outset of the play, he must appropriate aggressively the wealth needed to fund the war. His mismanagement of the conflict and subsequent peace negotiations leads to a failure to provide the kind of spoils that would satisfy his nobles or the benefits of collective security. Adapting Holinshed’s account of John’s reign briefly noted here, Shakespeare represents John’s fiscal policy as prompting bitter resentment and an outrage that heightens instability in the realm. Such fiscal resentment and outrage in turn heightens international antagonism, and Shakespeare highlights how the anger created by his fiscal actions becomes a resource that can be mobilized against John. Cardinal Pandulph, papal legate and general force of chaos in an extremely chaotic play, explains to the French nobles how John’s fiscal rapacity creates a geopolitical opportunity. In large part because of John’s aggressive fiscal policy:

There is much to say about this passage, especially about the complex reasons why Pandulph is able to equate John’s fiscal policy with “bloody” violence. I will discuss this aspect of the play in greater detail in Chapter 4. For now, we can observe how Pandulph brings to light the geopolitical embeddedness of fiscal policy. Shakespeare, like many others, understands that the fiscal security dilemma derives from and contributes to international antagonism. Taxes are necessary to fund the military activities required to exist in a predatory international environment. But, as Pandulph also knows, and as Shakespeare’s histories emphasize consistently, taxes can also create discontent and unrest capable of volatilizing both political and geopolitical relations.

Stated in slightly different terms, by way of highlighting one prominent source of England’s historical disadvantage on the terrain of the continent’s dynastic struggles, England’s monarchs were constrained by the constitutional limits on the royal ability to tax. To draw again on Kantorowicz’s central conceptual distinction, such constitutional constraints set up a potential conflict between the king’s two bodies, between the demands of providing for the “security of the whole body politic” and the interests of the private person of the monarch, between the “sempiternal” custodian of collective safety and wellbeing and the aspirations of the mortal dynastic agent interested in expanding the family fortunes. Fortescue again is helpful here to the extent that, for him, the incentive for royal fiscal restraint he advocates is to make the English people “rich and wealthy” in ways that allow the king to participate in the arena of European dynastic conflict, that will provide the king with the “power to subdue his enemies, and all others upon whom he shall wish to reign” (117). Once the realm’s prosperity and capacity to fund collective defense had been appropriately reestablished, then, if the king wanted, he could pursue whatever dynastic projects he wished.

Fortescue sought to constitute royal imperial aspirations as a benefit of good governance, an option available to dynastic rulers at their discretion, but not a requirement for the wellbeing and survival of the kingdom. But for other writers, such expansion was not an option but an imperative. To take the most prominent example, Machiavelli would argue that the polity that wishes to endure must expand. At least, his Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livius counseled the Florentine Republic that its security required ongoing imperial growth to resolve the tensions between its people and its elites.47 The imperative to expand, as Vickie B Sullivan has shown, represents a way to resolve the irreducible antagonism between the people, who wish to live in safety and not to be overtaxed, and the nobility, who desire above all opportunities to satisfy their desires for honor and wealth.48 Fortescue, by contrast, who cast a jaundiced eye on the demands and behavior of England’s elites, understood it to be the monarch’s choice whether or not to pursue territorial expansion, plunder, and subjection of “all others upon whom he shall wish to reign,” so long as it was understood that such a choice was contingent upon domestic fiscal restraint. That is, Fortescue’s imagined fiscal settlement sought to partition the monarch’s obligation to provide peace and security from the dynastic energies animating kings, and thereby to prioritize obligations to the realm over any private motives the sitting ruler may possess. Fortescue saw no problem with “oppression and plunder,” so long as such activities were directed outward and were undertaken after the monarch’s fiscal affairs were in order.

In practice, though, the distinction between the king’s two bodies could be a fuzzy one, especially when it came to defining collective security. Edward IV, who earned a reputation (among some historians at least) as exemplary for his fiscal restraint, indicated in an address to Parliament in 1467, his intention to “lyve upon my nowne” in order “not to charge my Subgettes but in grete and urgent causes, concernyng more the wele of theym self, and also the defence of theym and of this my Realme, rather than myne nowne pleasir.”49 But it is hard to imagine a monarch not making this kind of distinction between the defense and collective wellbeing of the realm as opposed to the pursuit of private, self-interested “pleasir.” Dynastic objectives clearly figured into how English rulers defined security and most of England’s monarchs for most of its history found it difficult, if not impossible, to live on demesne resources and feudal benefits alone. Military campaigns with obviously dynastic motives continued to take place and intensified during the reign of Henry VIII. The generally poor record of English monarchs’ military fortunes on the continent during the sixteenth century, coupled with dramatically increasing costs of war, saddled England with extraordinary debt, which by mid-century created incentives to rethink English foreign policy. Queen Elizabeth I understood both the limits on fiscal capacity she faced and the disadvantages of the kinds of conflicts Tudor monarchs before her pursued. Though Elizabeth’s own account of her approach to fiscal matters could be characterized as essentially Fortescuean, at least in her stated respect for the consent of her subjects and in her commitment to living within her fiscal means, she nevertheless implicitly rejected the Fortescuean compromise described immediately above that tacitly endorsed dynastic motives as a valid ground for geopolitical action.50 For instance, in her first request to Parliament for financial support, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal Sir Nicholas Bacon reported that Queen Elizabeth:

hath commanded me for to say unto you, that albeit yourselves see that this is noe matter of will, noe matter of displeasure, noe private cause of her owne, which in tymes past have bene sufficient for princes’ pretences (the more the pittie!), but a matter for the universal weale of this realme, the defence of our countrie, the preservacion of every man, his howse and familie particularlie…

At this earliest moment of her reign, in her first interaction with Parliament, Elizabeth differentiates herself from her forbears by constituting the obvious personal motives of former monarchs as lamentable “pretences” for accessing subjects’ wealth – “the more the pittie!” – at odds with the “universal weale,” “defence,” and “preservation” of the realm. So doing, she announced her commitment to what Giovanni Arrighi characterizes as a “realist” stance towards foreign policy that explicitly eschewed dynastic objectives and the general “adventurism” of many of her predecessors.51

Elizabeth’s desire to reground England’s relation to the geopolitical environment was successful for a while. But her general reticence towards continental wars was a source of frustration to some of her nobles and, eventually, largely due to the confessionalization of conflict in the latter decades of the century, England was drawn into ongoing European wars.52 Skyrocketing military expenditures forced her in the latter years of her reign to intensify the taxation of her people in ways that in turn intensified pushback, debate, critical complaint, fear, and, on occasion, outrage. Though Elizabeth would later in the seventeenth century come to be idealized for her willingness to get involved in confessional conflicts, the celebration of King James I at his coronation as the “King of peace and plentie” no doubt drew much of the joy it voiced from the promise of relief from the considerable burdens of funding security in the last years of Elizabeth’s rule.53 Nevertheless, fiscal exhaustion notwithstanding, precisely because of the many challenges she faced, her reign witnessed developments that, in the long term would transform England’s status as a geopolitical player. England eventually was able to achieve the vision of extended territorial expansion Teschke understands as animating late-medieval European dynastic geopolitics, but only by transforming the terms, technologies, and objectives of geopolitical engagement.

Stated in slightly different terms that emphasize England’s eventual imperial achievements, although Elizabeth eschewed adventurism in the dynastic sense Arrighi mentions, she and many others embraced adventurism in other, specifically commercial and colonial, senses. Focused on the long-term history of global capitalism, Arrighi argues that a set of responses to the weaknesses identified by the early Tudor monarchs’ poor military record and at times aggressive fiscal demands decisively shaped England’s abilities to establish and secure global trade networks: forging an alliance between the crown and merchant capital; reforming monetary and fiscal policy; lending support to a variety of joint stock companies centered on expanding trade; stimulating the development of the country’s industrial capacity; dramatically increasing the size and strength of the navy, and so forth.54 Following Ellen Meiksins Wood, we can add to Arrighi’s list England’s experience in Ireland, a kind of laboratory in which England gradually developed colonial administrative competence vital to its eventual imperial trajectory.55 Such initiatives allowed England to repurpose its existing capacities for assembling global scales of interaction, again to draw on Saskia Sassen’s framework, into an aggressively expansive commercial and colonial regime of accumulation.56 Although the shape of Charles Tilly’s version of the development of global capitalism differs significantly from that advanced by Arrighi, Tilly similarly shows how England by the latter decades of the seventeenth century had acquired the fiscal capacity that afforded its rulers dramatically expanded access to the wealth needed to wage war on an expanded scale.57 As Tilly argues, England forged a middle path between coercion-intensive and capital-intensive strategies of state formation. The hard-fought compromise between England’s monarchs and its merchant communities ultimately enhanced the strength of Parliament’s control over fiscal policy. In what to most of England’s monarchs over the centuries would have appeared to be an almost unthinkable irony, bolstering the institutions of consent to taxation profoundly expanded the capacity to tax. Expanded access to subjects’ wealth allowed England not only to survive geopolitically, but also to establish an extensive commercial and colonial empire scarcely imaginable in earlier centuries.

The processes of historical transformation sketched here involved a significant reconceptualization of security, aligning security more strongly with trade. Certainly, international trade had long been understood to be a factor impacting English security, given, for instance, the role customs revenue frequently played in funding sovereignty. In another register, as I elaborate in Chapter 2, Thomas More would critique Henry VII’s tax policy as effectively destroying trade rather than creating the conditions for expanded commerce, which in an ideal world would enhance collective wealth and thereby enhance the monarch’s ability to provide security. The alignment of security with commercial prosperity is thus a tendential, long-term development. Nevertheless, the seventeenth century witnessed an intensification and elevation of commercial activity as a normative criterion for understanding the nature and purpose of collective life and for evaluating the work of the nation’s rulers. Charles Taylor traces the development during this period of a “modern social imaginary” that understands collective belonging and practical interactions to be oriented toward “collective security” and “prosperity”; Taylor understands the development of these criteria for comprehending and evaluating social existence as deriving from the work of natural law theorists like Hugo Grotius and John Locke who grounded political authority in the right to self-preservation and who privileged security of property as a primary source of political legitimacy.58 Though it is not Taylor’s primary emphasis, the conceptual developments and practical orientation towards social life he describes take place in relation to, and no doubt contribute to, the expansion of fiscal and military capacities Arrighi, Sassen, and Tilly variously examine. It should also be clear from this chapter’s emphasis on the definitional openness of security as a concept that such a vision of security was not unanimously embraced. With respect to the authors taken up in this study, Herbert (as I discuss in Chapter 5) will take a grim view of a world given over to an expansive regime of material accumulation. And, though (as I show in Chapter 6) he was not by any stretch of the imagination hostile towards commerce as a human endeavor, Milton was nevertheless horrified by the argument that monarchy should be reinstated in England because a restored Charles II would be good for trade. Herbert and Milton’s responses suggest that transformation does not mean state formation is teleologically driven. However dramatic and decisive were the developments sketched here, such achievements were not predetermined or inevitable. Attention to struggles over defining and funding security highlights the contested and contingent nature of collective life, a contingency to which the authors taken up in this study were consistently and insistently drawn.

Literature and Controversy

This book foregrounds authors inspired by the “bureaucratic muse,” to borrow Ethan Knapp’s apt description of the ways administrative cultures enable and impact medieval literary production.59 The authors taken up in this study are frequently drawn to the administrative concerns underpinning the fiscal security dilemmas described here, and by the efforts to resolve those dilemmas. This book’s emphases are often thematic, but they are not exclusively so. That is, the ultimate objective of what follows is not only to highlight important transformations in how security was conceptualized and funded in the period, but also to understand the particular representational strategies authors employ and the motivating objectives orienting their engagement with the challenges of defining and implementing security. How authors depict security dilemmas tells us much about why they write, about their understandings of what literature can do, and about the kind of communities literary representation can sponsor. More, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton, among many others, demonstrate how forms of critical awareness and debate, pleasure and sociality can arise from the literary representation of governmental struggle.

In a word, these authors broach fiscal security dilemmas because they are controversial. The works studied here are controversial in the sense of the term developed by Michel Callon, Pierre Lascoumes, and Yannick Barthe. In their research on the social dimensions of technological innovation, they argue that “controversies are … [w]ith the hybrid forums in which they develop … powerful apparatuses for exploring and learning about possible worlds.”60 Their specific point of reference is how concerns about or resistance to the adoption of new technologies performs a salutary function. Controversy forces science out of the lab, reconfiguring the science–policy nexus, bringing it into “hybrid forums” by incorporating dissenting voices and the perspectives of protestors, of the concerned, of those impacted by technology’s unanticipated consequences, into the project of technical world making. As they write, “socio-technical controversies tend to bring about a common world … open to new explorations and learning processes” (35). Though Callon, Lascoume, and Barthe focus on technological innovation, their approach can be adapted to the administrative concerns orienting this study. Fiscal controversy brings into conflict competing understandings of security, alternative definitions of the common good, collective wellbeing and how best to secure it. Such controversy disrupts the taken-for-grantedness of the world, deroutinizes ongoing practices of worldmaking in ways that expand the concerns, perspectives, processes, and agents relevant to collective life. Controversy acknowledges the irreducible fact of difference driving political and geopolitical existence as authors in the period understand it. Controversies arise when people attempt to actualize their distinct perspectives, press competing claims deriving from alternative accounts of the world. Pressed far enough, such competing claims strain the available resources for stabilizing collective life and maintaining harmony.

With respect to this study’s animating concerns, fiscal policy is not controversial if it rests on a shared basis of consent and shared definitions of collective security. Taxation becomes controversial when there is no shared agreement about what defines the common good, what constitutes a legitimate security threat, when a particular understanding of security merits appropriating someone’s wealth, or who is included in or excluded from any given definition of security. Controversy thus brings into question prevailing definitions of whose perspective is relevant to collective life, challenges the evaluative criteria and modes of justification through which a status quo comes to be constituted. In terms of this study’s primary emphases, the controversies characterizing fiscal security dilemmas, the struggles over how to define security, how security comes to be implemented and governed, who pays for collective safety, for how long, and to what ends, all demonstrate the ongoing processes of struggle and creativity informing the governance of collective life.

More, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton engage with fiscal controversy in order precisely, in Callon, Lascoume, and Barthe’s words, to “explor[e] and learn … about possible worlds.” Broaching controversy represents a way both to question collective life and to perform collective existence through the resources of literary representation. The literary texts analyzed here gather people together in textual or theatrical communities through the act of figuring sovereignty and security under strain. Through imagining such moments of struggle, authors assemble provisional communities around the challenges of implementing sovereignty, the conflicts that arise in the vicinity of the basic need to fund sovereign designs, and the efforts of individuals and groups to assert their definitions of collective wellbeing. Their works engage fiscal controversies by way of dramatizing conflict in ways that foreground the fissures and fault lines of collective life. So doing, the authors examined here reflect upon the dynamism of political existence and enable readers or audiences to experience and imaginatively participate in that dynamism in textual or dramatic form.

Although Callon, Lascoumes, and Barthe’s understanding of controversy helps frame this book’s approach to fiscal security dilemmas, it will be important to distinguish from their project the kinds of literary engagement with controversy examined here. Callon and his coauthors possess an Enlightenment optimism in the powers of rational-critical exchange to direct dissensus and conflict into compromise, their sense that all participants in an exchange are “constrain[ed]” (33) by the norms of reasoned debate in public. By contrast, the chapters to follow focus on literary texts selected precisely because they are not committed to a single shared framework capable of adjudicating multiple incompatible perspectives in a way that would facilitate compromise. More, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton remediate controversy in ways that foreground multiple worlds in conflict. The works taken up here stage the clash of incompatible perspectives on security and collective wellbeing and put on display the challenges of funding security that simultaneously define and constrain the work of governance. They do so in order both to examine the nature of community and to create provisional forms of association through the very act of reading a work of literature or watching a theatrical performance. The literary depiction of security dilemmas is thus an exercise in exploring ways of being together in the world, in improvisationally inhabiting what Henry Turner refers to as “the ecology of … associational life” in early modern England.61

Sir Thomas More’s Utopia provides an occasion to delve into how fiscal policy and administrative activity constitute forms of worldmaking and thereby provide resources for performing associational life. Chapter 2, “Funding Utopia: Security, Fiscal Policy, and Humanist Association” argues that More’s Utopia places the challenges of defining and funding security at the center of its project, both in Book One’s critique of contemporary rule and in Book Two’s thought experiment about how to govern security. Utopia, as an alternative to contemporary Europe, can be seen as an attempt to resolve the fiscal security dilemmas besetting European governments by eliminating private property and money. The presence of other polities, though, complicates the effort to imagine a world in which security is distributed equitably, a world without fiscal conflict or the violence that monarchical wealth enables. Though Utopia imagines an existence where money is not necessary, the anomic and predatory geopolitical landscape within which Utopia exists forces Utopia to maintain a virtual fisc in the form of precious metals, foreign treasuries, and foreign debt obligations. Such reserves allow Utopia effectively to export insecurity, that is, to make Utopian existence safe by making non-Utopians’ existence more vulnerable. However, such geopolitical realities create ongoing challenges that cannot be neutralized by its governmental program, since Utopia’s massive fiscal reserves generate an ongoing need to protect itself from foreign conquest and plunder. Utopia thus provides both a powerful diagnosis of the shortcomings of contemporary governmental practice and a meditation on the limits of the ability to govern security. The narrative’s aims are further complicated by a refusal to endorse a clear set of policy recommendations. The deep irony that characterizes More’s work has the effect of underspecifying Utopia’s relation to its contemporary moment in ways that facilitate and intensify governmental inquiry, debate, and forms of sociability associated with humanist culture. The Utopian thought experiment institutes a way of exploring possibilities for improvisational sociality in the vicinity of sovereignty and administration, but in ways not fully defined by the demands and strictures of governmental reality.

The possibilities for improvisational sociality that inhere in governmental controversy inform the subsequent two chapters’ account of fiscal security dilemmas on the popular stage. Chapter 3, “Marlowe’s Treasuries,” demonstrates the centrality of fiscal infrastructures to the action of Marlowe’s plays. His Tamburlaine plays, The Jew of Malta, and A Massacre at Paris all hinge on the agencies created by – and the violence associated with – wealth organized into treasuries. Where More and his narrative interlocutors were deeply interested in the mundane workings of fiscal policy and the challenges and perplexities of implementing security, Marlowe is drawn to fiscal dimensions of more spectacular political and geopolitical conflict. The protagonists of the plays examined here – specifically, Tamburlaine, Barabas, and the Duke of Guise – draw attention to their own and others’ treasuries, and their stories underscore both the security and the volatility associated with treasuries in action. Tamburlaine, for instance, uses his treasury to heighten his prestige and to fund his imperial expansion project. In ways that echo Machiavelli’s vision of security produced through an expansive regime of accumulation, Tamburlaine uses his treasury to fund conquest that in turn enables further conquest. Though The Jew of Malta is attuned to the impossibility of reproducing Tamburlaine’s achievement, treasuries function in this play similarly to create episodes of heightened precarity. Maltese tax policy, the decision to appropriate the wealth of their island’s Jewish denizens, puts in motion all of the subsequent action of the play. The titular character Barabas, dispossessed of his considerable fortune, reassembles a treasury to revenge his fiscal treatment by creating suffering for those who originally seized his wealth. The Duke of Guise in A Massacre at Paris explicitly draws attention to how the revenue he receives from a variety of sources makes it possible for him to magnify confessional antagonisms between Protestants and Catholics. In each of these instances, treasuries drive the action by creating security for some through extreme violence to others. For Marlowe, treasuries are central to his depiction of geopolitical existence. Fiscal realities, in turn, represent a primary formal mechanism impacting how Marlowe’s characters – and audiences – experience the antagonistic spaces of geopolitical existence. Marlowe’s awareness of the challenges of implementing sovereignty are thus central to his ongoing project of creating controversial experience in the form of theatrical states of emergency.

Chapter 4, “Sovereignty and Security Dilemmas in William Shakespeare’s History Plays,” continues to explore how fiscal policy and questions of national security play on stage. As suggested briefly here, fiscal concerns pervade Shakespeare’s history plays. All of his sovereigns wrestle with the need to fund security in the face of ongoing domestic and international threats, and all of them have to confront ongoing fiscal discontent. Chapter 4 shows how security dilemmas are at the heart of controversies that drive English history as Shakespeare understands it. The ongoing effort to cover the expenses associated with implementing security coupled with subjects’ resentment at having to pay for their sovereign’s decisions opens up the terms of security and collective wellbeing for collective scrutiny. The controversy arising from implementing security creates forms of agency and affiliation that exceed or counter those associated with sovereign authority. All of Shakespeare’s history plays – but primarily in this chapter King John, The First Part and The Second Part of Henry IV, and Henry V – show sovereignty to be inherently fragile. Shakespeare’s monarchs struggle to secure their own interests and their hold on power in the face of threats from at home and abroad, endeavor to assemble the resources needed to reign, and strive to answer contestatory versions of how sovereigns and subjects relate. Henry V is the monarch who most successfully manages the fiscal security dilemma through military expansion. However, even his successes are subject to skeptical scrutiny, and the histories embed an awareness of the ongoing challenges of expansive foreign policies. By depicting a multiplicity of voices and perspectives on collective existence, Shakespeare foregrounds fiscal controversies and the alternative visions of security and collective life such controversies prompt. Shakespeare’s histories situate their audiences in this dialogic space of controversy. These plays attempt to create what I shall characterize as “strange” theatrical experiences by immersing theatergoers in an underdetermined world defined by antagonism, conflict, geopolitical struggle, and political inventiveness.