Introduction

Global financial markets can provide a powerful vehicle to lift nations out of poverty. Despite their merits, allowing governments to access much-needed capital for investment, global financial markets have also opened up possibilities for well-connected local elites to plunder the wealth of their countries and expatriate assets into safe havens. This type of “elite capital flight”—facilitated by the secrecy of offshore financial destinations (Cooley, Heathershaw and Sharman Reference Cooley, Heathershaw and Sharman2018)—is different from capital flows related to international trade and investment flows. Previous literature argues that dysfunctional governance frameworks open the floodgates for wealthy elites to move their fortunes abroad. Besides building the bedrock for corrupt business practices, elite capital flight deprives a country of the capital it needs to lift itself out of poverty.Footnote 1

While there is ample evidence of broad-based capital flight during balance-of-payments crises (Walter and Willett Reference Walter and Willett2012; Amri et al., Reference Amri, Chiu, Meyer, Richey and Willett2022; Breen & Egan, Reference Breen and Egan2019; Gehring and Lang Reference Gehring and Lang2020; Moon and Woo Reference Moon and Woo2022), we argue that financial bailouts themselves, intended to stabilize economies, can act as catalysts for elite capital flight. Specifically, when governments anticipate or access emergency liquidity, domestic elites may seize the opportunity to expatriate wealth to offshore destinations before conditions tighten or scrutiny increases. Despite a rapidly growing literature on the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) (Scheubel and Stracca Reference Scheubel and Stracca2019; Schneider and Tobin Reference Schneider and Tobin2020; Romani and Stubbs Reference Romani and Stubbs2024), there has been limited attention to how the design features of different bailout mechanisms shape elite incentives. Our core contribution is to theorize how these features affect the timing and scale of capital flight. We introduce a framework grounded in two independent but complementary dimensions: disbursement control and elite threat perception.

Disbursement control refers to a lender’s institutional ability to monitor, condition, and constrain the use of disbursed funds. It involves phased disbursements, regular program reviews, and sanction mechanisms. Institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) typically exhibit high disbursement control. By contrast, low disbursement control is characteristic of bilateral or opaque arrangements, such as central bank swap lines or commercial loans from geopolitical allies, that disburse funds rapidly and with minimal oversight. Elite threat perception captures the extent to which domestic elites believe their rents, wealth, or political dominance are at risk due to bailout-linked reforms. High threat perception arises when reforms threaten to expose or dismantle monopolistic privileges, clientelist networks, or illicit financial flows. Low elite threat perception, by contrast, occurs when bailouts are technical in nature and focus on liquidity or macroeconomic stabilization without targeting elite behavior or rent structures. We argue that these two dimensions shape distinct elite responses. Where disbursement control is high and threat perception is high, as in many IMF programs, elites are likely to engage in ex ante elite capital flight, moving assets offshore before program start. Anticipating disruptive reforms undermining rent-seeking activities, elites exploit insider information and informal influence to shield their wealth and rescue aligned business interests, often in ways that remain outside the formal reach of compliance regimes (Kern et al. Reference Kern, Nosrati, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023; Nosrati et al. Reference Nosrati, Kern, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023). This dynamic is especially pronounced in environments where domestic institutions are weak and asset protection is feasible through the use of offshore vehicles. In contrast, when disbursement control is weak and elite threat perception is low, as is often the case with PBoC swap lines, elites may engage in ex post elite capital flight. With no immediate transparency requirements or restrictions on the use of funds, elites can opportunistically exploit fungible bailout liquidity for personal gain (i.e., moral hazard). While these funds are not formally earmarked for elites, weak governance allows them to be funneled into elite-dominated financial schemes, including fictitious loans, trade mis-invoicing, opaque credit facilities, or kickback networks (Shea, Reinsberg and Kern Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2022).

To test these theoretical predictions, we employ a mixed-methods research design that combines three short case studies and a large-N analysis to test the generalizability of our findings. We selected Angola (2008), Tajikistan (2008), and Mongolia (2011–16). In the cases of Angola and Tajikistan, we demonstrate how elites, anticipating the arrival of an IMF program and subsequent disruption of their extractive rent-seeking schemes, ex ante move substantial wealth into offshore financial havens. In contrast, we show, in the case of Mongolia, how the ability to draw on PBoC swap lines enabled ex post elite capital flight between 2011 and 2016. For our large-N analysis, we rely on a dataset comprising up to 201 countries between 1990 and 2018. We are particularly interested in capital flight into offshore financial destinations, which we obtained from data on bilateral banking ties from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS 2022).Footnote 2 We specifically isolate the capital outflows of a potential borrowing country into a selected set of offshore tax havens.Footnote 3

Using multivariate linear regression analysis, we find a moderate positive relationship between an anticipated IMF program and offshore capital flight—measured by the proportion of bank deposits held in offshore financial destinations. Substantively, where government elites expect an IMF program, the ex ante offshore deposit share increases by 14.2% (95% CI: 5.7%–22.7%). Moreover, we show that when governments have drawn a PBoC swap line, the ex post share of financial deposits in offshore destinations strongly increases by 92.3% (95% CI: 23.7%–160.5%). If we include both instruments of the GFSN in the same model, the coefficient of the PBoC swap line increases further, whereas the coefficient of IMF programs attenuates. These results are robust against meaningful variation in model specifications. To bolster our inferences, we consider circumstances under which elites can anticipate IMF bailouts less, notably when these bailouts follow deadly natural disasters. We also obtain significant findings using shift-share instrumental-variable designs, suggesting that our core relationships can be causally interpreted. Importantly, accounting for financial crises as a confounding variable, our results remain intact, indicating that our postulated relationship cannot be attributed to elites’ response to the onset of financial turmoil (Stone Reference Stone2008; Marchesi and Marcolongo Reference Marchesi and Marcolongo2023). Finally, we perform falsification tests and verify that our results hold more strongly for theoretically plausible scope conditions.

We contribute to several lines of research. First, we contribute to longstanding research in international political economy on global financial markets (Steinberg Reference Steinberg2015; Frieden Reference Frieden2016; Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Wellhausen Reference Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Wellhausen2021; Bauerle Danzman, Winecoff and Oatley Reference Bauerle Danzman, Kindred Winecoff and Oatley2017; Bunte Reference Bunte2019; Henisz and Mansfield Reference Henisz and Mansfield2019; Kaplan Reference Kaplan2021; Mehrling Reference Mehrling2022; Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Rosendorff Reference Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Peter Rosendorff2024). Here, our focus is aligned with research analyzing various aspects of elite capital flight (Willett and Auerbach Reference Willett and Neiman Auerbach2009; Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2014; Zucman Reference Zucman2015; Boyce and Ndikumana Reference Boyce and Ndikumana2017). More specifically, we complement the existing literature has concentrated on political driving forces of elite capital flight (Rixen Reference Rixen2013; Frantz Reference Frantz2018; Binder Reference Binder2019; Crippa Reference Crippa2025), underlying illicit financial activities (Sharman Reference Sharman2017; Kalyanpur and Thrall Reference Kalyanpur and Thrall2022; Morse Reference Morse2022), and the behavioral mechanics of tax evasion and illicit financial flows (Findley, Nielson and Sharman Reference Findley, Nielson and Sharman2013; Sharman Reference Sharman2017; Saez and Zucman Reference Saez and Zucman2019; Findley et al. Reference Findley, Laney, Nielson and Sharman2017). As such, our work is closely related to research analyzing how regulatory shifts drive elites’ desire to shield their wealth in offshore jurisdictions (for a recent survey, see Crippa and Kalyanpur (Reference Crippa and Kalyanpur2024)). As we are concentrating on international crisis lending, our approach builds on recent political economy literature on foreign aid, demonstrating that significant amounts of aid get wasted due to corruption (Winters and Martinez Reference Winters and Martinez2015; Heinrich and Kobayashi Reference Heinrich and Kobayashi2020; Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022).Footnote 4

Second, our paper expands the vast literature on the GFSN and the international political economy of bailouts (Roubini and Setser Reference Roubini and Setser2004; Schneider and Tobin Reference Schneider and Tobin2020; Scheubel and Stracca Reference Scheubel and Stracca2019; Horn et al. Reference Horn, Parks, Reinhart and Trebesch2023; Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Rosendorff Reference Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Peter Rosendorff2024).Footnote 5 Here, our study offers several innovations. Besides being concerned with the unintended consequences of crisis lending concerning capital flight dynamics (Kern et al. Reference Kern, Nosrati, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023; Nosrati et al. Reference Nosrati, Kern, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023), a key innovation is that we analyze these capital flight dynamics also for the case of PBoC swap lines. While McDowell (Reference McDowell2019a ), Sundquist (Reference Sundquist2021), and Sahasrabuddhe, Li and Wingo (Reference Sahasrabuddhe, Li and Wingo2024) provide in-depth accounts of PBoC swap lines and their modus operandi, they do not consider potential moral hazard effects once these swap lines are deployed.Footnote 6 In particular, we show that the lack of conditions attached to using disbursed funds or macrofinancial safeguards can build the backbone of elite capital flight dynamics triggered by moral hazard. Insofar our work is well-aligned with findings as suggested in Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers (Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022), Kern, Reinsberg and Shea (Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024), and Shea, Reinsberg and Kern (Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024), who find evidence of similar financial re-rerouting mechanisms for international development assistance and emergency lending. Building on a mixed-methods design, a key innovation of our work is to expand on these insights and provide systemic evidence on the viability of capital flight mechanisms in the context of international financial bailouts.

From a policy perspective, our study emphasizes how the global institutional architecture of emergency lending sets perverse incentives that further elite capital flight into offshore financial destinations, especially under circumstances of moral hazard on the part of government elites (Dreher and Walter Reference Dreher and Walter2010; Lipscy and Lee Reference Lipscy and Na-Kyung Lee2019; Aklin and Kern Reference Aklin and Kern2019). As financial firms—primarily located in the Global North—frequently facilitate capital flight into offshore financial destinations (Cooley and Sharman Reference Sharman2017; Cooley, Heathershaw and Sharman Reference Cooley, Heathershaw and Sharman2018; Prelec and de Oliveira Reference Prelec and Soares de Oliveira2023; Morse Reference Morse2022; Nosrati et al. Reference Nosrati, Kern, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023; Crippa and Kalyanpur Reference Crippa and Kalyanpur2024), our findings underscore recent transparency rules’ utmost importance and viability.

Theoretical considerations

The empirical puzzle underlying our inquiry is that many heavily indebted and crisis-ridden countries are net creditors to the rest of the world (e.g., Zucman Reference Zucman2015). The so-called Panama and Paradise Papers, alongside various financial leaks, illustrate how senior political and business leaders from Indonesia, Argentina, Pakistan, and several other prominent debt-ridden economies have managed to shield their wealth in offshore financial destinations (for a survey, see, among others, Binder Reference Binder2019; Morse Reference Morse2022; Hoang Reference Hoang2022; Crippa and Kalyanpur Reference Crippa and Kalyanpur2024).Footnote 7 Examining the determinants of elite capital flight into offshore financial destinations, a substantial literature has identified domestic factors such as weak institutions, inadequate fiscal frameworks, and endemic corruption as key enabling forces (Collier, Hoeffler and Pattillo Reference Collier, Hoeffler and Pattillo2001; Le and Rishi Reference Le and Rishi2006; Ndikumana, Boyce and Ndiaye Reference Ndikumana, Boyce and Saloum Ndiaye2014; Zucman Reference Zucman2015; Reuter Reference Reuter2017; Collin Reference Collin2021; Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith2020).Footnote 8 It is often powerful business groups and senior policymakers—given their insider knowledge and capabilities to embezzle public funds—who are the direct beneficiaries of offshore financial wealth (Reuter Reference Reuter2017; Binder Reference Binder2019; Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022; Morse Reference Morse2022). While recent research has focused on various regulatory and tax policy interventions in explaining the increase of elite capital flight to offshore financial destinations (Zucman Reference Zucman2015; Londono-Velez and Avila-Mahecha Reference Londono-Velez and Avila-Mahecha2021; Crippa Reference Crippa2025; Crippa and Kalyanpur Reference Crippa and Kalyanpur2024) these accounts largely treat capital flight as a response to domestic institutional constraints. Relatedly, scholarship that analyzes the political economy of foreign aid has long argued that a portion of foreign aid is wasted due to corruption in the recipient country, resulting in an increase in elite capital flight (Boyce and Ndikumana Reference Boyce and Ndikumana2017; Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022). The latest addition to this literature is an influential study showing how government elites squander World Bank funds to offshore financial destinations (Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022).

Yet in many cases, episodes of elite capital flight coincide with major international financial interventions, raising the possibility that the design of external support itself shapes elite behavior. Historically, elite capital flight has been closely associated with the onset of macroeconomic turmoil and financial crises, particularly in countries facing sharp currency depreciations, banking collapses, or sovereign defaults (Hausmann and Rojas-Suarez Reference Hausmann and Rojas-Suarez1996; Collier, Hoeffler and Pattillo Reference Collier, Hoeffler and Pattillo2001; Willett and Auerbach Reference Willett and Neiman Auerbach2009; Ndikumana, Boyce and Ndiaye Reference Ndikumana, Boyce and Saloum Ndiaye2014). However, these analyses have largely remained silent on whether the design of bailout mechanisms contributes to where and when elites move their funds.

Recent research has begun to explore this question more directly by linking the institutional architecture of international financial support to elite capital flight outcomes (McDowell Reference McDowell2016; Schneider and Tobin Reference Schneider and Tobin2020; Morse Reference Morse2022; Kern et al. Reference Kern, Nosrati, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023; Nosrati et al. Reference Nosrati, Kern, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023; Shea, Reinsberg and Kern Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024). For example, Marchesi and Marcolongo (Reference Marchesi and Marcolongo2023) demonstrates that financial crises tend to result in an ex post increase in elite deposits in offshore financial centers. In contrast, Aiyar and Patnam (Reference Aiyar and Patnam2021) find no such relationship in cases where countries receive IMF support, suggesting that conditional bailouts may constrain capital outflows. However, Kern et al. (Reference Kern, Nosrati, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023) demonstrate that elites may instead engage in ex ante capital flight in anticipation of IMF reform requirements. Related evidence from Kern, Reinsberg and Shea (Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024) and Shea, Reinsberg and Kern (Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024) suggests that capital flight also occurs after disbursement when countries borrow from Chinese sources, which typically offer fewer transparency and enforcement provisions.

Despite these contributions, it remains uncertain how different forms of international financial support influence the timing, scale, and channels of capital flight among domestic elites. Here, we introduce a simple framework built around two analytical dimensions: disbursement control and elite threat perception. These dimensions reflect both the institutional characteristics of external financial aid and the strategic calculations of domestic elites. This approach moves beyond simple comparisons between bailout types and instead focuses on how variations in design and perceived political risk shape elite responses.

First, in our context, disbursement control refers to a lender’s ability to monitor, condition, and constrain the use of disbursed funds. This includes formal mechanisms such as phased disbursements, program reviews, audit trails, and potential sanctions for noncompliance. For instance, a high degree of disbursement control is characteristic of multilateral institutions such as the IMF, which impose structured conditionality, regular monitoring, and program evaluations. Low disbursement control is more common among opaque bilateral lenders, such as central bank swap arrangements or commercial lending from geopolitical partners, where disbursements are rapid, fungible, and rarely subject to independent oversight.

Second, elite threat perception refers to the extent to which domestic elites believe their wealth, rents, or political dominance are at risk due to the terms or implications of a bailout. These threats can emerge through transparency reforms, market liberalization, tax enforcement, or anti-corruption efforts that expose previously shielded wealth. High elite threat perception arises when bailout conditions undermine monopolistic privileges, clientelist structures, or the opacity that enables rent extraction. Low elite threat perception occurs when the bailout avoids reforms targeting elite interests, focusing instead on technical liquidity support or macroeconomic stabilization with no scrutiny of elite behavior.

By separating these dimensions, we conceptualize elite capital flight not merely as a reaction to formal program conditions but as a strategic response to perceived threats to elite rents and wealth. Organizing bailout mechanisms across these two dimensions offers analytical leverage to explain when and why elites choose to move capital offshore, whether preemptively, in anticipation of reforms, or after disbursement, when enforcement is minimal. This framework also clarifies why capital flight may occur either in anticipation of a bailout (ex ante) or after its disbursement (ex post), depending on elite perceptions and the credibility of enforcement. In the following sections, we apply this logic to two prominent instruments in the GFSN, IMF programs, and PBoC swap lines, and derive testable hypotheses. There are several reasons why we chose to focus our analysis on these bailout mechanisms.

First, governments facing balance-of-payments crises have historically turned to the IMF for bailout funding, placing the institution at the center of the GFSN (Schneider and Tobin Reference Schneider and Tobin2020; Scheubel and Stracca Reference Scheubel and Stracca2019; Kern and Reinsberg Reference Kern and Reinsberg2022). More recently, China has emerged as a key international lender to countries in the Global South, with a surge in China-facilitated bailouts (McDowell Reference McDowell2019a ; Kern and Reinsberg Reference Kern and Reinsberg2022; Horn et al. Reference Horn, Parks, Reinhart and Trebesch2023). A central instrument in China’s financial diplomacy has been the expansion of PBoC swap lines (Horn et al. Reference Horn, Parks, Reinhart and Trebesch2023). PBoC swap lines are bilateral agreements through which the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) provides foreign currency liquidity to partner central banks. In these arrangements, the PBoC supplies renminbi (RMB) in exchange for an equivalent amount of the recipient’s domestic currency, based on a predetermined exchange rate. The swap typically has a fixed term (e.g., three months) and may include an agreed-upon interest rate or fee for the use of funds. Importantly, these transactions are not secured through any multilateral enforcement mechanism or collateral, but rely solely on the terms of a bilateral contract between the PBoC and the recipient central bank. An important caveat is that, once drawn upon and disbursed in the local financial system, these can be exchanged in offshore RMB hubs (e.g., Hong Kong) for US Dollars.

Second, while both instruments serve to alleviate foreign reserve shortages, they differ sharply across our two analytical dimensions. In terms of disbursement control, IMF programs require governments to accept binding policy conditions aimed at restoring macroeconomic stability, such as fiscal consolidation, structural reforms, and increased transparency (McDowell Reference McDowell2016). The IMF’s capacity to monitor compliance through phased disbursements and program reviews reflects a high level of disbursement control. At the same time, concerning elite threat perception, IMF conditionality can directly threaten elite financial interests by undermining monopolistic structures, exposing hidden wealth, or curtailing rent-seeking opportunities. By contrast, PBoC swap lines involve no conditionality, oversight, or formal accountability mechanisms. Like IMF loans, the funds are transferred directly to a country’s central bank, ostensibly to shore up reserves and stabilize exchange rates. However, the absence of monitoring or ex post review makes these arrangements more vulnerable to elite capture and misuse. Thus, in our framework, IMF programs are characterized by a high degree of disbursement control and potentially high elite threat perception, whereas PBoC swap lines exemplify low disbursement control paired with low elite threat perception.

Finally, these two instruments offer a valuable contrast for examining how variations in disbursement control and elite threat perception influence both anticipatory (ex ante) and reactive (ex post) elite capital flight behavior. While our framework can accommodate a broader typology of bailout instruments, we focus empirically on these two ideal types to maintain analytic clarity. The following sections outline the mechanisms by which each instrument shapes elite incentives for offshore capital movement and derive corresponding hypotheses.

IMF programs

We begin with the IMF, the central node in the global bailout regime, and the case that most clearly illustrates the potential for both strong disbursement control and high elite threat perception. From a theoretical perspective, IMF bailouts come with strings attached that can threaten the locally held wealth of domestic elites. Loan conditions targeting increased transparency, structural reforms that dismantle monopolistic market structures, and fiscal adjustments aimed at boosting public revenue and reducing expenditures can expose illicit enrichment or even jeopardize elite financial schemes. The unifying thread across these conditions is their capacity to disrupt established elite wealth and undermine rent extraction (Bayer et al. Reference Bayer, Hodler, Raschky and Strittmatter2020; Kalyanpur and Thrall Reference Kalyanpur and Thrall2022; Brandt Reference Brandt2023). At the same time, neither the IMF nor domestic authorities have jurisdiction over assets parked in offshore financial centers (Kern et al. Reference Kern, Nosrati, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023). This legal limitation provides local elites with strong incentives to move capital offshore in anticipation of an IMF program that could disrupt rent-extraction opportunities and expose their wealth to scrutiny driven by reform. While it is difficult to identify the exact individuals behind these financial outflows, there is substantial evidence that economic elites drive the bulk of transactions into offshore destinations. For instance, Londono-Velez and Avila-Mahecha (Reference Londono-Velez and Avila-Mahecha2021) use Colombian tax data to confirm that the country’s elites hold the lion’s share of offshore accounts. Similarly, the Panama and Paradise Papers document that wealthy individuals, often politically connected, benefit disproportionately from these offshore schemes (Binder Reference Binder2019; O’Donovan, Wagner and Zeume Reference O’Donovan, Wagner and Zeume2019; Bayer et al. Reference Bayer, Hodler, Raschky and Strittmatter2020; Kalyanpur and Thrall Reference Kalyanpur and Thrall2022; Hoang Reference Hoang2022; Crippa Reference Crippa2025; Crippa and Kalyanpur Reference Crippa and Kalyanpur2024). Synthesizing these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: Offshore capital flight increases as elites anticipate that their country will undergo an IMF program in the following year.

Several implicit assumptions underpin our argument. First, IMF staff are presumed to be unaware of these schemes. The secrecy surrounding elite capital flight makes this plausible (for a review, see Nosrati et al. (Reference Nosrati, Kern, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023)). Second, the IMF continues to provide bailouts even when aware of these perverse incentives. While the IMF cannot legally deny bailout loans to countries in economic distress, it is incentivized to provide loans to avert global financial instability shocks (Tomz Reference Tomz2007; Nooruddin Reference Nooruddin2010; Kaplan and Shim Reference Kaplan and Shim2024). Although the IMF does not initiate negotiations, it is approached by government elites seeking assistance (Stone Reference Stone2004; McDowell Reference McDowell2016; Lipscy and Lee Reference Lipscy and Na-Kyung Lee2019). Once negotiations begin, the IMF cannot legally refuse bailout requests but can impose stringent conditionality to mitigate moral hazard (Dreher Reference Dreher2009). Given its mandate to uphold global financial stability and the severe consequences of sovereign default (Stone Reference Stone2004; Dreher and Jensen Reference Dreher and Jensen2007; McDowell Reference McDowell2016), the IMF rarely denies bailout requests. Additionally, globally operating banks and international financial institutions, which benefit from elite capital flight while having significant exposure to these economies, might lobby their home governments for financial bailouts (Gould Reference Gould2003; Broz and Hawes Reference Broz, J. and Brewster Hawes2006; Ferwerda and Zwiers Reference Ferwerda and Zwiers2022; Copelovitch Reference Copelovitch2010). Finally, a key assumption is that elites have access to private information about the state of the economy, which investors and citizens do not. In many emerging and developing countries, verifiable data on the actual state of the economy is limited, making it likely that only politically well-connected elites can access this information (Crippa Reference Crippa2025; Nosrati et al. Reference Nosrati, Kern, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023). If wealthy elites can anticipate the onset of an IMF program and intend to protect their assets, our proposed effect should manifest only for IMF programs triggered by predictable events. Conversely, the offshore capital flight effect should vanish during IMF programs initiated by unpredictable events, such as natural disasters. Although IMF programs following natural disasters also require negotiation time, they offer faster emergency relief (Ferry and Zeitz Reference Ferry and Zeitz2024). Moreover, elites cannot easily foresee non-anthropogenic natural disasters, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, or pandemics, meaning these programs are not driven by elite intentions. For this reason, we expect the hypothesized relationship between ex ante elite capital flight and IMF programs to disappear in contexts where elites have less control over the occurrence of an IMF program. In contrast, where elites trigger the IMF program after moving their wealth to safe havens, these programs are predictable. Thus, we distinguish between ‘disaster-unrelated programs’ and ‘disaster-related programs.’ While both types address economic shocks, only disaster-unrelated programs involve elite intentionality. Because elites cannot anticipate natural disasters, the perceived threat to their wealth is diminished ex ante, even if subsequent programs involve conditionality. In our framework, low anticipation translates into low elite threat perception, thereby muting capital flight responses in disaster-related bailouts.

PBoC swap lines

In contrast to IMF programs, PBoC swap lines fall into the quadrant of low disbursement control and low elite threat perception in our framework. These bilateral agreements between the PBoC and the central banks of borrowing countries provide renminbi liquidity to address short-term foreign currency shortages. As such, they operate without macrofinancial conditionality or oversight mechanisms (Broz and Zhang Reference Broz and Zhang2018; Sahasrabuddhe Reference Sahasrabuddhe2019; McDowell Reference McDowell2019b ; Horn et al. Reference Horn, Parks, Reinhart and Trebesch2023). Once activated, the recipient central bank has broad discretion over the use of funds, without formal constraints on how proceeds are spent (McDowell Reference McDowell2019b ). This absence of conditionality or monitoring significantly lowers elite threat perception: swap disbursements do not challenge existing rents or expose illicit wealth. At the same time, low disbursement control opens the door to potential misuse. While elites may not gain direct access to these funds, the opaque financial environment facilitates indirect forms of appropriation, such as inflated trade invoices, “evergreening” of politically connected loans, or using reserves to guarantee off-budget liabilities (Shea, Reinsberg and Kern Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024). For instance, in the recent case of Mozambique, repayment of the so-called Tuna bonds, alongside the kickbacks included in this financial scheme, was directly tied (through a guarantee scheme) to the Banco de Moçambique’s foreign reserves. As recent court documents reveal, several policymakers and their family members were beneficiaries of these kickbacks that were wired into a web of offshore bank accounts while being backed by the country’s foreign currency reserves.Footnote 9

As a result, elites face little reason to engage in capital flight before a swap line is activated: their rents remain unthreatened, and oversight is minimal. Instead, capital flight is more likely to occur after disbursement, as elites take advantage of the loosened financial environment and the fungibility of central bank reserves. In practice, this logic is reflected in cases such as Mongolia, where PBoC funds were used to support banks linked to political elites (Arnold Reference Arnold2023), or in the case of Argentina where the PBoC’s swap line allowed the government to prevent defaulting on its IMF payments while maintaining bloated fiscal deficits and being cut off from Western debt markets (Wang and Canuto Reference Wang and Canuto2023).

Hypothesis 2: Elite capital flight increases after a country has drawn on a PBoC swap line.

Our argument is based on several implicit assumptions that we address here. Given this potential leakage of PBoC swap lines, it remains unclear why Beijing would provide these bailout funds. There are several reasons for this.

First, even if PBoC officials are well-informed about a counterparty’s institutional framework before approving a swap line (Yazar Reference Yazar2023), the structure of these agreements significantly limits their ability to monitor how the liquidity is ultimately used. Unlike IMF arrangements, PBoC swap lines do not require external audits, safeguards assessments, or public reporting on fund use (Watrous and Paduano Reference Watrous and Paduano2025). Once disbursed, swap funds are recorded on the recipient central bank’s balance sheet as foreign exchange inflows, which makes it difficult, if not impossible, for external analysts or forensic auditors to trace how the funds are used within the domestic financial system (Fund 2018). This lack of traceability is especially problematic in contexts with known governance vulnerabilities. Recent investigations into Chinese special-purpose vehicle lending schemes, often linked to elite beneficiaries (Gelpern et al. Reference Gelpern, Horn, Morris, Parks and Trebesch2021), show that neither host-country regulators nor the IMF had full visibility over these transactions. Only indirect evidence, like balance-of-payments anomalies, raised red flags after the fact (Kern and Reinsberg Reference Kern and Reinsberg2022; Kern, Reinsberg and Shea Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024; Watrous and Paduano Reference Watrous and Paduano2025). These governance blind spots, coupled with the lack of enforceable safeguards, highlight the limited ability to control the disbursement of swap lines and their potential for exploitation by domestic elites.

Second, because PBoC swap lines provide short-term financial stabilization without attached policy conditions, governments in severe financial distress can obtain immediate relief while minimizing the political costs typically associated with IMF programs (Kern, Reinsberg and Shea Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024; Shea, Reinsberg and Kern Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024). In many such cases, governments depend on elite support to remain in power and therefore must accommodate elite interests, whether through patronage, regulatory forbearance, or tolerance of opaque business practices. Although Beijing officially maintains a policy of noninterference in domestic affairs (Brautigam Reference Brautigam2011; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Fuchs, Parks, Strange and Tierney2022), it has a clear interest in preserving the political status quo and sustaining cooperative ties with incumbent regimes (Shea, Reinsberg and Kern Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024). As such, bailouts in the form of PBoC swap lines, with their absence of enforcement mechanisms or conditionality, enable elites to continue extracting rents and receiving patronage, reinforcing the low elite threat perception that characterizes this bailout instrument in our framework.

Third, despite governance risks and the absence of enforceable safeguards, Chinese authorities have strong incentives to maintain PBoC swap lines (Broz and Zhang Reference Broz and Zhang2018; McDowell Reference McDowell2019a ; Sahasrabuddhe, Li and Wingo Reference Sahasrabuddhe, Li and Wingo2024). They allow governments to service maturing debts to Chinese contractors and policy banks, thereby helping Beijing mask non-performing loans without resorting to formal restructurings or write-downs. For instance, Pakistan reportedly used swap proceeds to roll over payments to Saudi Arabia and Chinese firms (Kern, Reinsberg and Shea Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024). These arrangements sustain distressed projects while shielding them from public scrutiny, especially given the opacity and kickback schemes often associated with Chinese loan deals. Moreover, swap lines facilitate trade settlement in renminbi, helping recipient countries ease short-term reserve pressures. This ensures continued Chinese export flows into financially unstable but strategically important markets, preserving Beijing’s commercial footprint even during crisis periods (Hao, Han and Li Reference Hao, Han and Li2022). For instance, Argentina’s reliance on renminbi-denominated trade, facilitated through swap lines, has constrained President Milei’s ability to pivot away from China, despite his ideological inclinations.Footnote 10 At a systemic level, PBoC swap lines allow bypassing dollar-based systems and thus help to advance China’s broader goal of RMB internationalization and the construction of an alternative financial architecture. By combining liquidity support, trade facilitation, and geopolitical leverage, without triggering elite resistance, PBoC swap lines can serve as a low-cost, high-impact instrument of geo-economic influence.

Finally, a key aspect to consider is that an IMF program often coincides with a PBoC swap line. This situation emerges when a country simultaneously draws on multiple credit lines.Footnote 11 Despite advances in analyzing the relationship between Chinese lending and IMF programs (Kern and Reinsberg Reference Kern and Reinsberg2021; Kern, Reinsberg and Shea Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024; Ferry and Zeitz Reference Ferry and Zeitz2023; Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Rosendorff Reference Ballard-Rosa, Mosley and Peter Rosendorff2024; Zeitz Reference Zeitz2025; Watrous and Paduano Reference Watrous and Paduano2025), little guidance exists with respect to elite capital flight. Building on previous work, countries tend to approach the IMF for bailout funding when Chinese bailouts (and thus PBoC swap lines) are insufficient to contain balance-of-payments crises (Kern and Reinsberg Reference Kern and Reinsberg2022; Kern, Reinsberg and Shea Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024; Watrous and Paduano Reference Watrous and Paduano2025). In these cases, elites appear to be siphoning off bailout funds after receiving them from China. In contrast, the spike in elite capital flight seems to have occurred before the onset of an IMF program, allowing elites to shield their wealth in offshore financial havens (Kern, Reinsberg and Shea Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Shea2024). Given the lack of transparency surrounding this topic (Ferry and Zeitz Reference Ferry and Zeitz2023; Horn et al. Reference Horn, Parks, Reinhart and Trebesch2023; Watrous and Paduano Reference Watrous and Paduano2025; Zeitz Reference Zeitz2025), we are left to speculate that our proposed mechanism might have been the reason why the IMF blocked a $1.5 billion PBoC swap line for Sri Lanka in 2022.Footnote 12 Despite this lack of clarity or guidance, for both bailout mechanisms, we believe that the fragmented nature of global financial regulation enables elites to channel funds into offshore financial destinations, where they remain protected.

Scope conditions

Our theoretical framework produces several observable implications beyond the main empirical patterns. Specifically, we expect that the effects of international bailouts on elite capital flight will be most significant in certain institutional and political configurations. These scope conditions influence the likelihood and extent of capital flight by affecting the two core aspects of our framework: disbursement control and elite threat perception. While our main analysis compares IMF programs and PBoC swap lines based on these two aspects, we also explore cases where country-specific institutions or external interventions amplify or reduce either aspect, thereby moderating how elites respond to financial bailouts.

First, we examine instances where disbursement control is heightened. To this end, we analyze the role of central banks. The institutional quality and autonomy of central banks are key to both monitoring outbound financial flows and deterring elite misuse of external funds. However, in practice, they can also be captured by domestic elites and used as vehicles for illicit outflows (Johnson Reference Johnson2016; Kern and Seddon Reference Kern and Seddon2024). Recent research suggests that greater gender diversity on central bank boards, particularly the inclusion of women in decision-making roles, is associated with stronger institutional integrity and reduced tolerance for corruption (Comunale et al. Reference Comunale, de Bruxelles, Kochhar, Raskauskas and Filiz Unsal2023; Kern, Reinsberg and Romelli Reference Kern, Reinsberg and Romelli2024). By increasing professional independence and policy credibility, women’s representation can enhance both formal and informal constraints on elite behavior. This dynamic raises perceived constraints on elite rent extraction, reinforcing disbursement control and reducing opportunities for capital flight. To further probe this dimension, we analyze IMF programs that include conditionality designed to enhance central bank independence (CBI) (Reinsberg, Kern and Rau-Göhring Reference Reinsberg, Kern and Rau-Göhring2020). These “CBI conditions” directly reduce elite influence over monetary authorities, thereby increasing disbursement control and, importantly, raising elite threat perception.

Second, we examine the robustness of the second dimension in our theoretical framework: elite threat perception. Political instability, particularly in the form of coup threats, increases the risk of expropriation or regime turnover, thereby undermining the viability of rent-seeking activities and business models that rely on expropriation and embezzlement. Elites facing such threats have strong incentives to secure assets abroad, leading to increased capital flight. We expect that when an IMF program can result in social unrest and political upheaval (Reinsberg and Abouharb Reference Reinsberg and Rodwan Abouharb2023), elite threat perception is heightened, leading to an increase in ex ante elite capital flight. Similarly, once a PBoC swap line is disbursed, elites will increase their siphoning of funds if they fear that an uprooting of the political status quo will threaten and undermine their rent-seeking activities. This heightened elite threat perception should lead to an increase in ex post elite capital flight.

Finally, elite capital flight requires both motive and means. While our framework emphasizes disbursement control and elite threat perception, the ability to execute illicit transfers also depends on the availability of financial conduits. Among these, state-owned banks play an important role. As integral parts of the domestic financial system and often tied to the monetary transmission mechanism, they are natural intermediaries for channeling bailout funds. In many contexts, they also function as discretionary lending vehicles for politically connected elites (Panizza Reference Panizza2023; Nosrati et al. Reference Nosrati, Kern, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023). Their presence can thus facilitate the misappropriation of external assistance and enable covert capital transfers with limited scrutiny. The implications of this dynamic vary by bailout instrument. Under IMF programs, the Fund’s greater disbursement control through audit requirements, safeguards assessments, and transparency benchmarks can expose financial irregularities and deter misuse. In contrast, PBoC swap lines, which lack such oversight, allow state-owned banks to operate with greater discretion. Their institutional embeddedness and access to bailout funds make them effective channels for ex post capital flight, especially when elites perceive little threat of detection or punishment. Empirically, we find that the share of state-owned banks has no significant effect on ex ante elite capital flight under IMF programs, but plays a substantial role in enabling ex post elite capital flight under PBoC swap arrangements. To further probe this mechanism, we consider an additional scope condition: capital account restrictions. While such controls are designed to prevent outward financial flows, well-connected elites are uniquely positioned to circumvent them through informal or illicit channels (Pond Reference Pond2018). As a result, we expect capital controls to amplify ex ante elite capital flight under IMF programs, as elites anticipate future scrutiny and move early. Conversely, under PBoC swap lines, we expect capital controls to dampen ex post flight, as these controls limit transfer options after funds are received.

Research design

To illustrate the mechanisms of our proposed theoretical framework, we employ a mixed-methods approach, combining three case studies—Angola (2008), Tajikistan (2008), and Mongolia (2011–2016)—with a large-N empirical analysis. Our case selection follows a logic of diverse case selection (Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008), combining elements of both most-similar and most-different research designs. The selected cases share important structural features: all selected countries are resource-dependent economies with significant elite control and documented exposure to offshore financial destinations (OFDs). At the same time, they differ in regime type, creditor institution (IMF vs. PBoC), and across our two core analytical dimensions: disbursement control and elite threat perception. We begin with Angola and Tajikistan in 2008, both of which turned to the IMF during the global financial crisis, at a time when Chinese swap lines were not yet available. In both cases, commodity price shocks threatened a deanchoring of the balance-of-payments (i.e., collapsing oil prices in Angola; falling aluminum prices (and remittances) in Tajikistan), necessitating an IMF bailout entailing significant disbursement control. Consistent with our framework, fears of an incoming IMF program and subsequent conditionality elevated elite threat perception and contributed to ex ante capital flight. Both countries also exhibit well-documented financial linkages to offshore financial centers. The dos Santos family in Angola was at the center of the Luanda Leaks (Heathershaw Reference Heathershaw2011; Cooley and Sharman Reference Cooley and Sharman2015), while Tajikistan’s TALCO aluminum smelter operated through offshore shell companies reportedly controlled by President Rahmon’s family.Footnote 13 In contrast, Mongolia (2011–2016) illustrates ex post capital flight under conditions of low disbursement control and low elite threat perception. While Mongolia shares post-socialist institutional legacies with Tajikistan, it followed a more democratic trajectory. However, repeated activations of PBoC swap lines, in the context of weak banking supervision, enabled politically connected elites to extract liquidity without external oversight. This case exemplifies how bailouts, when implemented in permissive institutional environments, can facilitate ex post elite capital flight following their disbursement. Together, these cases demonstrate variation across both aspects of our theoretical framework, while keeping structural factors such as resource dependence, elite asset concentration, and elite offshore exposure relatively unchanged. We supplement these within-case findings with a large-N empirical analysis to evaluate the broader applicability of our argument.

Mini cases

Tajikistan

Tajikistan provides an illustrative case of ex ante elite capital flight under conditions of high disbursement control and heightened elite threat perception due to looming IMF engagement. Emerging as an independent state from the Soviet Union, Tajikistan remains one of the poorest countries in Central Asia. Despite widespread poverty, the ruling elite has accumulated substantial offshore wealth, with multiple reports documenting their use of shell companies and secrecy jurisdictions to hide public funds abroad (Heathershaw Reference Heathershaw2011).

A key episode illustrating our framework occurred in the early 2000s, when Tajikistan faced a severe external financing gap. Under conditions of low elite threat perception, elites orchestrated a fraudulent scheme buried deep within the central bank’s balance sheet. Specifically, the central bank secretly issued credit guarantees to elite-linked lenders in the cotton sector, pledging nearly all of its foreign reserves. To conceal these liabilities, central bank officials “doctored” financial records, rendering the guarantees invisible to IMF staff during program negotiations.Footnote 14 As a result, when the IMF disbursed funds to replenish what appeared to be depleted reserves, it inadvertently unlocked liquidity that elites subsequently expatriated. This case exemplifies how weak disbursement control, defeated by strategic concealment, can enable ex post elite capital flight even in the absence of immediate elite threat perception. The hidden $300 million loss was only discovered through a later internal IMF audit.Footnote 15

A more systemic illustration involves the Tajikistan Aluminum Company (TALCO), the country’s largest exporter.Footnote 16 In 2005, the government established a tolling arrangement through Talco Management Ltd., registered in the British Virgin Islands, which purchased raw bauxite and sold finished aluminum.Footnote 17 TALCO itself, comprising a single state-owned smelter, operated as a processing facility and received only a fixed fee. As a result, all profits from aluminum exports were booked offshore, bypassing domestic taxation and oversight. According to Heathershaw (Reference Heathershaw2011, 160), this structure diverted over $1.145 billion in public revenue between 2005 and 2008Footnote 18 . This model differs fundamentally from corporate tax minimization schemes, such as Apple’s former “Double Irish” (Palan Reference Palan2024). While the “Double Irish” separated intellectual property from production within a regulated legal framework, the TALCO arrangement lacked any independent corporate governance. The same political actors controlled both the state-owned enterprise and its offshore counterpart, enabling direct rent extraction and providing “substantial cash flow to the ruling elite” (ICG, 2009, 14). A 2008 U.S. diplomatic cable quoted a senior Tajik official stating that “Tajikistan would be ready to accept any conditions the Fund demanded,” underscoring the depth of the fiscal shortfall.Footnote 19

In sum, the Tajikistan case exemplifies that ex ante capital flight, in anticipation of an IMF program.

Angola

Angola’s experience during the global financial crisis provides a textbook case of ex ante elite capital flight under conditions of heightened elite threat perception and disbursement control. Emerging from a protracted civil war, Angola became a key recipient of Chinese development finance. Between 2004 and 2007, the Angolan government contracted over $4.5 billion in oil-backed loans from the China Eximbank and other Chinese entities (Brautigam Reference Brautigam2011; Corkin Reference Corkin2011; Brütsch Reference Brütsch2014). These loans were structured as “loans-for-oil” deals, where Sonangol, the state-owned oil company, pledged future oil shipments as collateral in exchange for capital inflows earmarked for infrastructure and reconstruction.

While these arrangements initially helped rebuild war-torn infrastructure, they also created a fiscal environment vulnerable to elite capture. Much of the incoming finance was routed through Sonangol, which retained discretion over the allocation of funds. This centralization allowed for the expansion of quasi-fiscal operations and the diversion of revenues into offshore escrow accounts under opaque terms (Corkin Reference Corkin2011; Ferreira and Soares de Oliveira Reference Ferreira and Soares de Oliveira2019). As global oil prices collapsed in 2008, Angola’s revenue streams plummeted. Although Sonangol’s earnings had previously been transferred to bolster foreign exchange reserves, much of these funds had already been diverted or poorly documented. To fend off mounting pressures on the Kwanza and prevent a disorderly currency devaluation, the Angolan central bank deployed approximately $8 billion in foreign exchange reserves—a legitimate macroeconomic intervention to stabilize the economy (Jensen and Paulo Reference Jensen and Miguel Paulo2011; Brütsch Reference Brütsch2014). However, by the time Angola approached the IMF for assistance, a significant portion of earlier oil revenues, specifically $4.2 billion, was missing from official accounts. When the IMF initiated a Stand-By Arrangement in 2009, it reported that these funds, held in offshore escrow accounts by Sonangol, could not be traced appropriately or verified.Footnote 20

This sequence maps clearly onto our theoretical expectations. The anticipated arrival of the IMF introduced high disbursement control through conditionality, audit requirements, and transparency provisions (Goes Reference Goes2022). Independently, Angola’s elites, who were confronted with a deteriorating macroeconomic environment, dwindling oil revenues, and looming external scrutiny, experienced heightened elite threat perception. In response, they preemptively moved assets offshore before the Fund’s program was finalized. Angola’s opaque financial governance, heavy dependence on oil exports, and Sonangol’s centralized control over rent flows further amplified the vulnerability to capital flight. Multiple investigations, notably the Luanda LeaksFootnote 21 and Swiss LeaksFootnote 22 , have since documented how Angolan elites, particularly the dos Santos family, systematically utilized complex offshore networks to siphon state-linked funds into OFDs (Salah Ovadia Reference Salah Ovadia2018; Ferreira and Soares de Oliveira Reference Ferreira and Soares de Oliveira2019). Although not all vanished funds can be conclusively tied to elite extraction, the convergence of weak domestic oversight, centralized rent flows, and external conditionality supports the operation of elite-driven capital flight mechanisms. The Angola case thus demonstrates how rising expectations of external scrutiny, paired with anticipated disruptions in rent-seeking through a bailout program, can catalyze preemptive financial outflows ahead of formal bailout engagement.

Mongolia

Mongolia illustrates a case of ex post elite capital flight under conditions of low disbursement control and low elite threat perception. Following the post-2000s mining boom, Mongolia became increasingly dependent on Chinese trade and investment. In 2011, to strengthen reserves and stabilize the Tugrik, the Bank of Mongolia (BoM) signed a bilateral swap agreement with the PBoC, initially granting access to RMB 5 billion (Arnold Reference Arnold2023).

While initially framed as a macroeconomic stabilization tool, the swap line effectively financed a series of quasi-fiscal credit programs between 2012 and 2016. According to KPMG’s audit, between 2012 and 2016, BoM disbursed MNT 7.2 trillion across 17 schemes, bypassing standard due diligence processes (KPMG, 2018, 1214) (KPMG 2023). The IMF later concluded that these programs amounted to quasi-fiscal spending, enabled by swap inflows and conducted in the absence of institutional safeguards (IMF 2018). In this institutional environment, swap-financed liquidity became a conduit for the enrichment of elites. Investigations by the Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG) revealed systemic laundering of corruption proceeds through family-linked bank accounts and offshore vehicles (APG 2017). A prominent example is former Prime Minister Batbold Sukhbaatar, who allegedly used a transnational web of shell companies to embezzle and launder funds derived from resource concessions and kickbacks.Footnote 23 Unlike the Fed or ECB swap facilities (for a review, see Perks et al. (Reference Perks, Rao, Shin and Tokuoka2021)), which operate within highly regulated and transparent banking environments, Mongolia’s BoM functioned in a context of weak governance and limited public accountability. Independent auditors noted the absence of risk management and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) checks—conditions that allowed the financial system to be exploited by elites for personal gain (APG 2017; KPMG 2023).

In line with our framework, the case illustrates elite capital flight under conditions of low disbursement control. While elite threat perception remained moderate due to China’s geopolitical backing and the absence of IMF oversight during the initial years of the swap agreement, the lack of institutional checks allowed elites to leverage central bank resources for private enrichment. This pattern of behavior reflects a broader risk in swap-based financial stabilization when governance conditions are weak and political insulation remains high. Mongolia thus exemplifies how foreign liquidity injections, absent significant disbursement control, can inadvertently reinforce ex post capital flight.

Data

Turning to our large-N analysis, we assembled a dataset of up to 201 countries between 1990 and 2018.Footnote 24 While data availability for IMF programs is good, there is limited data on Chinese swap lines. For regressions including Chinese swap lines, our effective sample reduces to 38 countries from 2009 to 2018.

Dependent variable

We construct a measure of offshore capital flight using data on direct cross-border capital flows in private bilateral bank deposits from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS 2022). A key advantage of our measure is to isolate de facto bank transactionsFootnote 25 instead of relying on measures related to trade mis-invoicing, statistical residuals in balance-of-payments, or incorporation in offshore financial sinks.Footnote 26

Constructing our measure of offshore capital flight involves two steps. First, we aggregate the reported bank deposit amounts of a country in 18 selected offshore financial centers, many of them considered “tax havens” (Garcia-Bernardo et al. Reference Garcia-Bernardo, Fichtner, Takes and Heemskerk2017; Damgaard, Elkjaer and Johannesen Reference Damgaard, Elkjaer and Johannesen2019; Coppola et al. Reference Coppola, Maggiori, Neiman and Schreger2020). As destination countries, we select the Bahamas, Bahrain, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Chile, Chinese Taipeh, Curacao, Cyprus, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Isle of Man, Jersey, Luxembourg, Macao, Ireland, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland. Banking deposits in these jurisdictions can plausibly be connected to wealthy individuals and firms seeking a safe haven for their private wealth (Zucman Reference Zucman2015; Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022; Kern et al. Reference Kern, Nosrati, Reinsberg and Sevinc2023).Footnote 27 Second, we divide the deposits in offshore destinations by the deposits in all reporting countries. Using the proportion of deposits held in offshore destinations has the advantage of directly capturing the theoretically relevant concept. Empirically, it can mitigate reporting bias across countries and avoid endogenous scaling effects that were to occur if we divided deposits by the size of the economy (which must be expected to shrink during economic downturns).

Figure 1 shows the evolution of offshore capital flight over time between 1990 and 2018. The median share of capital deposits in OFDs has been stable between 1990 and 2018. At the same time, multiple outliers register most of their capital deposits in these destinations. The main takeaway from Figure 1 is that global trends are unlikely to drive our results, given the relatively constant share of capital deposits in OFDs (for similar observations, see, Marchesi and Marcolongo (Reference Marchesi and Marcolongo2023) and Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers (Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022)).

Figure 1. The illustration shows the annual median value of the deposits held in offshore bank accounts as a share of all deposits. Whiskers indicate the 25th percentile and 75th percentile, while dots represent outliers.

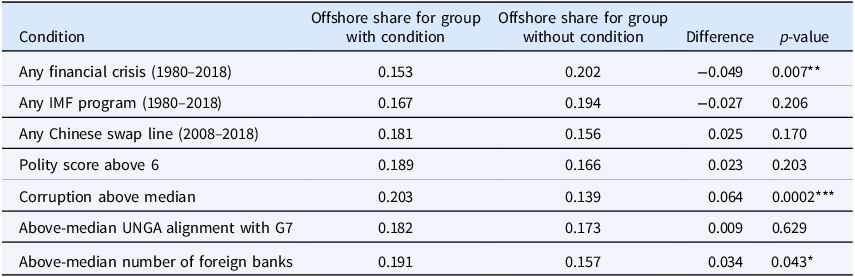

To better understand which countries drive offshore capital flight, we calculate mean group differences and conduct t-tests for various background characteristics. Table 1 shows the results. The share of bank deposits held in OFDs is significantly larger in countries that experience fewer financial crises, more corrupt countries, and countries with more foreign banks. To provide a reading example: The second row shows the mean share of bank deposits in offshore accounts for countries that never had an IMF program and for countries that had at least one program from 1980 to 2018. We find no difference in the prevalence of offshore capital flight depending on whether the country had an IMF program. Neither do we find a statistically significant difference in the use of Chinese swap lines across both groups of countries.

Table 1. Different country characteristics and average offshore capital flight

The results represent the results of two-sided t-tests with unequal variance. Significance levels: °

![]() $p \lt 0.1{,^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

$p \lt 0.1{,^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

Key predictors

Our main predictors are binary and capture the use of GFSN instruments. First, we construct a binary variable indicating whether a country is undergoing an IMF program. This variable enters with a one-year lead, following our argument that offshore capital flight will increase when government elites expect to go under an IMF program. We draw information about IMF programs from the IMF Monitor Database (Kentikelenis, Stubbs and King Reference Kentikelenis, Stubbs and King2016). To maximize the number of observations for analysis, we updated the list of IMF programs based on publicly available data for the latest years in the sample. Second, we include a binary variable indicating whether a country draws a swap line with the Chinese central bank (Horn et al. Reference Horn, Parks, Reinhart and Trebesch2023). The data are available only for the most recent ten-year period in our sample.

To address inferential threats, we identify IMF bailouts following natural disasters. Compared to ordinary bailouts, which reflect the strategic choices of governments, disaster-related bailouts are more difficult to predict by elites, given that the underlying natural disasters are unpredictable. To identify natural disasters, we draw on the EM-DAT database (CRED 2020) and measure the incidence of any natural disasters with at least 25 deaths in a given year.Footnote 28

For Chinese swap lines, we distinguish between when a government requests a swap line and when a government draws on a swap line. If jointly included in a regression model, the estimand of interest—the drawing of a swap line—is plausibly purged from selection effects captured by the agreement indicator.Footnote 29

Control variables

To eliminate confounding bias, we include several control variables, organized in three sets. The first is a minimal set of control variables, which includes country-fixed effects, time-fixed effects, and aggregate capital deposits reported by all 48 destination countries in the BIS database (BIS 2022). Incorporating aggregate capital outflows is important to mitigate concerns that we are picking up an episode of rapid capital outflows.

The second set adds macroeconomic controls, including the percent rate of GDP growth and the (logged) inflation rate,Footnote 30 reserves in months of imports (WDI 2020), and a binary indicator for financial crisis (Laeven and Valencia Reference Laeven and Valencia2013). These variables jointly capture economically turbulent times. During periods of crisis, countries are more likely to seek international financial assistance but are also likely to suffer abrupt money outflows. Importantly, accounting for financial crises in our model is important because this might be an omitted third variable driving both elite capital flight, a fast depletion of foreign reserves, and a country’s need to approach the IMF for bailout funding (Stone Reference Stone2002; Beeson and Broome Reference Beeson and Broome2008; Marchesi and Marcolongo Reference Marchesi and Marcolongo2023).

The third set of controls captures structural variables and political factors. We include the log-transformed GDP per capita (WDI 2020), the polity score for democracy (Marshall, Jaggers and Gurr Reference Marshall, Jaggers and Robert Gurr2015), and the V-Dem sub-index on executive corruption (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Lindberg, Skaaning and Teorell2016). Incentives for offshore capital flight may increase as countries get richer and political leaders become more corrupt but decrease as democratic accountability increases. At the same time, these variables can affect the likelihood of international bailouts. To complete our modeling setup, we include two-way fixed effects: country-fixed effects absorb time-invariant omitted factors, whereas year-fixed effects absorb common shocks. We report descriptive statistics and further information on data sources in the supplementary appendix (Table A1).

Empirical models

Since our dependent variable is continuous, we estimate Ordinary Least Squares regressions. Compared to a nonlinear fractional model, the linear model is easier to interpret. We believe that misspecification bias is unlikely to be an issue, given that there is very little bunching at the extremes. Formally, we estimate models of the following generic form:

where

![]() ${y_{it}} = {{\mathop \sum \nolimits_j^{{J_0}} \,{d_j}} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_j^J \,{d_j}}}$

is the share of deposits held in offshore destinations

${y_{it}} = {{\mathop \sum \nolimits_j^{{J_0}} \,{d_j}} \over {\mathop \sum \nolimits_j^J \,{d_j}}}$

is the share of deposits held in offshore destinations

![]() ${J_0}$

over the deposits in all reporting destinations

${J_0}$

over the deposits in all reporting destinations

![]() $J$

, as a function of financial assistance from the global financial safety net (

$J$

, as a function of financial assistance from the global financial safety net (

![]() $GFS{N_{i,t \cdot }}$

), a vector of control variables (

$GFS{N_{i,t \cdot }}$

), a vector of control variables (

![]() ${X_{it}}$

), country-specific effects (

${X_{it}}$

), country-specific effects (

![]() ${u_i}$

), and year effects (

${u_i}$

), and year effects (

![]() ${\varphi _t}$

). All other terms are estimable parameters, except the idiosyncratic error term (

${\varphi _t}$

). All other terms are estimable parameters, except the idiosyncratic error term (

![]() ${\varepsilon _{it}}$

). For the vector of estimands, we expect

${\varepsilon _{it}}$

). For the vector of estimands, we expect

![]() $\hat \beta \gt 0$

, with the timing of effects differing across different financial instruments. Specifically, we expect capital flows into OFDs to increase when governments are about to agree on an IMF program and when governments have already drawn a Chinese swap line.

$\hat \beta \gt 0$

, with the timing of effects differing across different financial instruments. Specifically, we expect capital flows into OFDs to increase when governments are about to agree on an IMF program and when governments have already drawn a Chinese swap line.

When distinguishing between ordinary bailouts (

![]() $GFS{N^O}$

) and disaster-related bailouts (

$GFS{N^O}$

) and disaster-related bailouts (

![]() $GFS{N^D}$

), we estimate the following model:

$GFS{N^D}$

), we estimate the following model:

where variables are defined in the same way as above. We expect

![]() ${\hat \beta _1} \gt 0$

but

${\hat \beta _1} \gt 0$

but

![]() ${\hat \beta _2} = 0$

.

${\hat \beta _2} = 0$

.

Illustrative evidence

We first illustrate offshore capital flight patterns around different types of financial insurance mechanisms using quarterly data. To that end, we isolate all 558 episodes of IMF program onsets between 1993 and 2018 and fit a local polynomial to examine the evolution of offshore capital flight around the onset of an IMF program.Footnote 31 We do the same for all 13 cases between 2008 and 2018 in which countries have drawn a Chinese swap line for the first time.Footnote 32

Figure 2 shows that while the pre-program offshore capital flight is relatively stable in the three years before an IMF program, it displays an upward spike two quarters before the IMF program onset and drops sharply after that to reach a local minimum by the third quarter of an IMF program. This pattern is consistent with an elite-driven capital flight to offshore destinations in the run-up to an IMF program.Footnote 33 Even if one considers that it may take up to one quarter to finalize negotiations for an IMF program (McDowell and Steinberg Reference McDowell and Steinberg2017), the peak of capital outflow still lies before the decision to approach the Fund. After the IMF program onset, we observe a drop in offshore capital flight, likely driven by an uptake in (ordinary) capital flight following IMF program onset (Pepinsky Reference Pepinsky2014; Gehring and Lang Reference Gehring and Lang2020).

Figure 2. The illustration shows the local polynomial fit of the offshore capital deposit share for 558 IMF program onsets in the sample period.

Figure 3 shows that capital flight into offshore destinations peaks after the fourth quarter after the country has drawn a Chinese swap line. In contrast, offshore financial flows are relatively stable before the use of a Chinese swap line. These patterns are consistent with elite capital flight because Chinese swap lines do not come with fiduciary safeguards that would prevent the siphoning of funds to offshore destinations. In the next sections, we will probe the robustness of these patterns using multivariate analysis at different levels of temporal granularity.

Figure 3. The illustration shows the local polynomial fit of the offshore capital deposit share for 13 Chinese swap drawings in the sample period.

Regression analysis

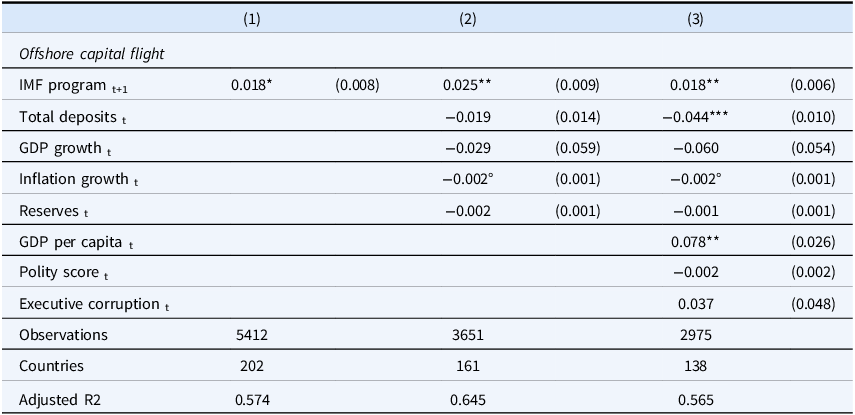

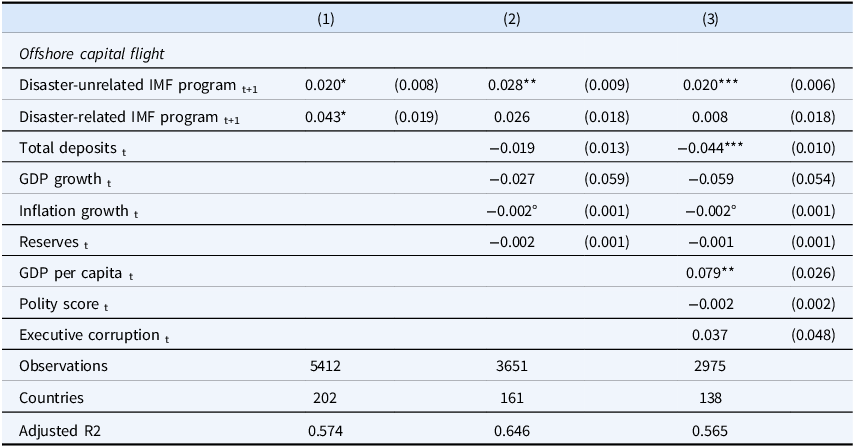

Using annual data, we test the relationship between anticipated bailouts and offshore capital flight with multivariate regression analysis. Table 2 presents the results for IMF programs under three different sets of control variables. We find that the anticipation of an IMF program is related to an increase in the proportion of bank deposits in offshore destinations by about two percentage points—equivalent to 14.2% (95% CI: 5.7%–22.7%).Footnote

34

Coefficient magnitudes are remarkably similar across different model specifications, and estimates are statistically significant (

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

). Control variables behave in line with theoretical expectations but are mostly insignificant. For example, the proportion of elite capital flight is lower when countries register more bank deposits abroad. Neither economic crisis variables nor political characteristics are consistently related to elite capital flight. Countries with a higher per capita income register a higher share of offshore deposits.

$p \lt 0.05$

). Control variables behave in line with theoretical expectations but are mostly insignificant. For example, the proportion of elite capital flight is lower when countries register more bank deposits abroad. Neither economic crisis variables nor political characteristics are consistently related to elite capital flight. Countries with a higher per capita income register a higher share of offshore deposits.

Table 2. IMF program anticipation and offshore capital flight

OLS regression with two-way fixed effects and robust standard errors clustered on countries in parentheses. Significance levels: °

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

,

$p \lt 0.1$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

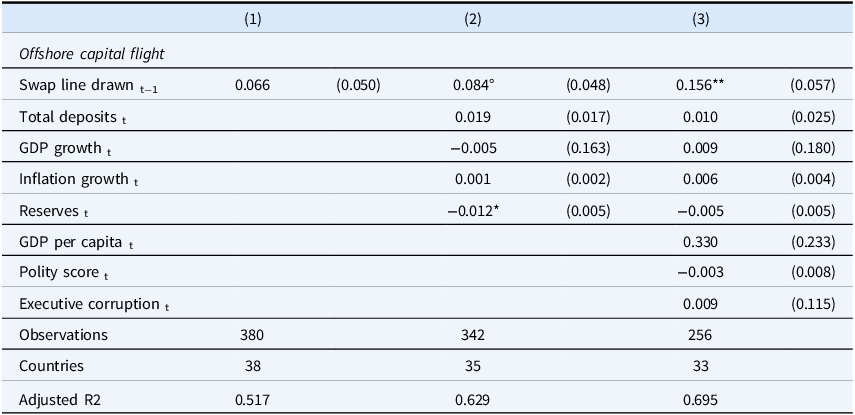

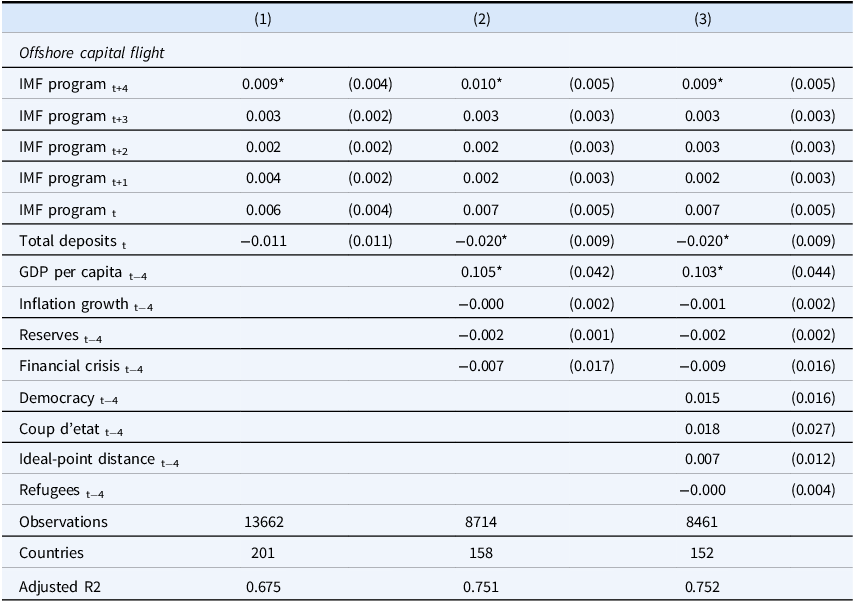

Table 3 presents the results for Chinese swap lines using different sets of control variables. We find that a country registers an increase in the proportion of bank deposits in offshore destinations after having drawn a Chinese swap line by up to 15.6 percentage points—equivalent to 92.3% (95% CI: 23.7%–160.5%).Footnote 35 Coefficient magnitudes are stronger once we control for crisis variables and political characteristics. Control variables do not generally reach conventional levels of statistical significance but tend to show the expected sign.

Table 3. IMF program anticipation and offshore capital flight

OLS regression with two-way fixed effects and robust standard errors clustered on countries in parentheses. Significance levels: °

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

,

$p \lt 0.1$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

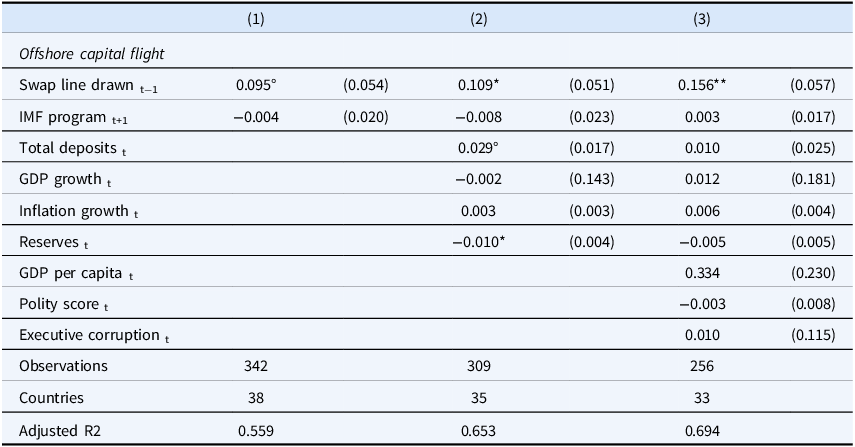

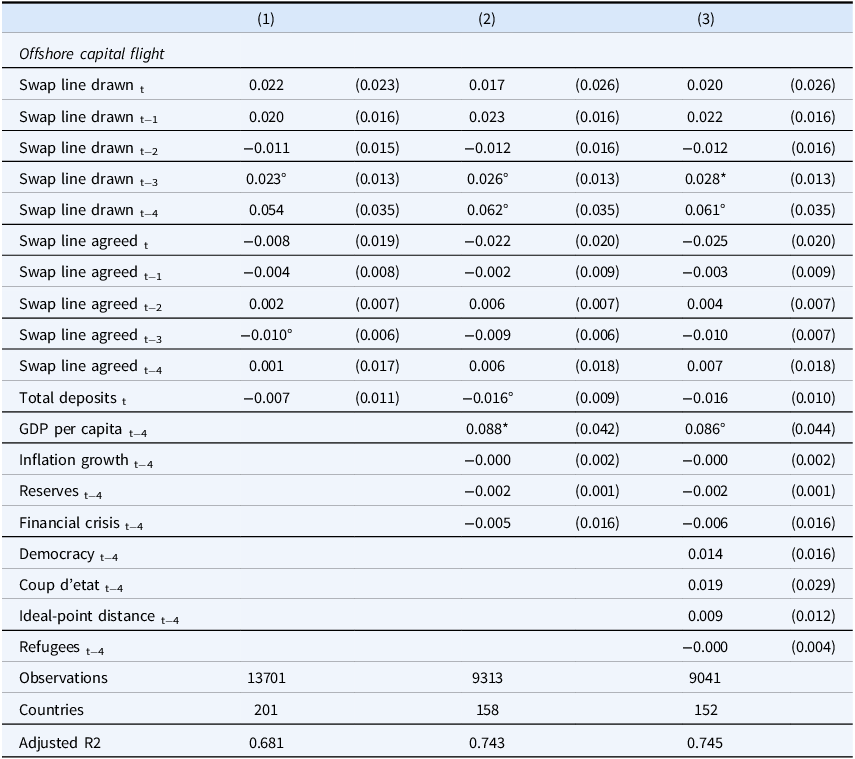

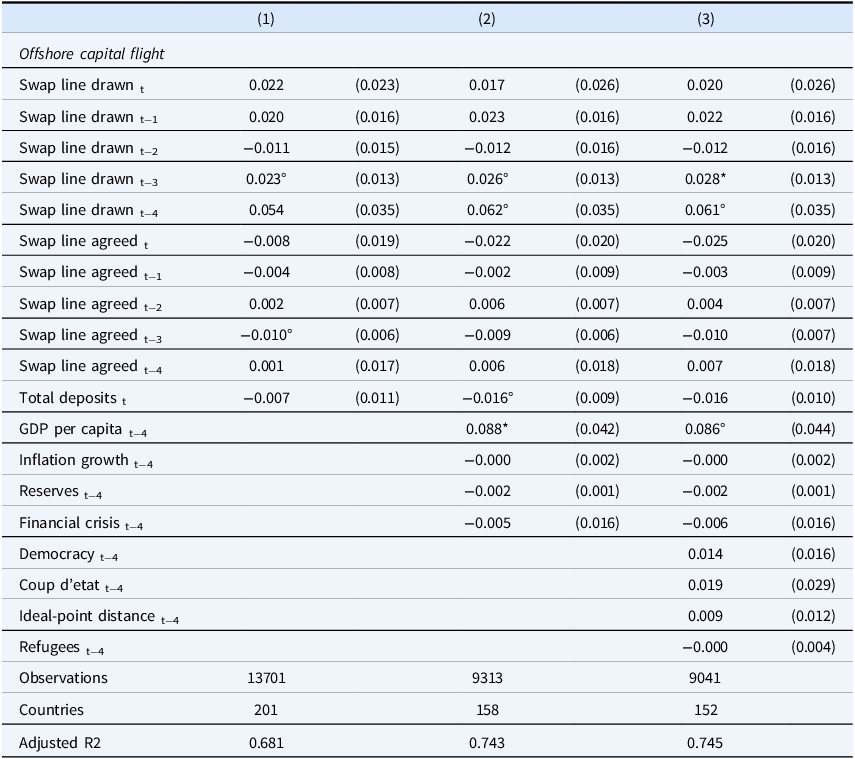

Ultimately, we are interested in the combined effect of different financial insurance mechanisms. Table 4 therefore includes both IMF programs and Chinese swap lines in the regression model. We find that only Chinese swap line drawings are significantly related to capital flight into offshore financial destinations. In contrast, an impending IMF program no longer has a significant relationship with offshore capital flight.

Table 4. Chinese swap line drawings, IMF program anticipation, and offshore capital flight

OLS regression with two-way fixed effects and robust standard errors clustered on countries in parentheses. Significance levels: °

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

,

$p \lt 0.1$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}p \lt 0.05$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}p \lt 0.01$

,

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}p \lt 0.001$

.

In the supplemental appendix, we probe the robustness of the latter set of findings to meaningful variations in our model specification. In particular, we use an extended set of control variables that mirrors the lag-lead structure of our key predictors. Despite this more demanding specification, our results are qualitatively unaffected (Table A2). We also include additional control variables—the incidence of a banking crisis, an ordinal measure of the exchange rate regime, and an index of capital account restrictions.Footnote 36 Our results are unchanged (Table A3). In addition, we exclude high-income countries from the sample, considering they are unlikely to receive bailouts.Footnote 37 Our estimates are unchanged, suggesting that our results are not driven by our sampling choice (Table A4). Finally, we probe our results using alternative definitions of offshore destinations. We obtain similar results when including the United Kingdom (which is not a “tax haven” but a conduit for international financial flows, specifically in the Commonwealth) and the Netherlands (due to its role as a conduit for international financial flows and its favorable (corporate) tax regime). Our results also hold for the list of 17 OFD countries dubbed “tax havens” (Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers Reference Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers2022), as well as countries with disproportionate flows of “phantom FDI”—investment flows that do not reflect real economic activity and that facilitate offshore capital flight (Damgaard, Elkjaer and Johannesen Reference Damgaard, Elkjaer and Johannesen2019). Results are not robust to an extensive list of “financial sinks” (Garcia-Bernardo et al. Reference Garcia-Bernardo, Fichtner, Takes and Heemskerk2017), although we note that limited data availability prevents us from including many relevant jurisdictions from this list. Our final destination country serves as a placebo test: flows into the US should be an unattractive target for elite capital flight, given that the Treasury can sanction financial transactions and freeze the assets of foreign entities in the US (Bean Reference Bean2018; Crippa Reference Crippa2025; Crippa and Kalyanpur Reference Crippa and Kalyanpur2024). In fact, we obtain a negative relationship between Chinese swaps and offshore capital flight into the US (Table A5).

Finally, we use a counterfactual two-way fixed-effects estimator that circumvents the problems of canonical fixed-effects estimation (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Li, Chen and Liu2022). The canonical two-way fixed-effects estimator can be biased in the presence of treatment effect heterogeneity, carry-over effects, and treatment reversals (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Li, Chen and Liu2022). Our baseline results may be biased given the problem of negative weights, which occurs under staggered treatment adoption and treatment effect heterogeneity, although treatment reversal is less relevant in our setting, given the quasi-absorbing nature of the treatment. The fixed-effects counterfactual estimator addresses this inferential challenge by matching each treated observation with a predicted counterfactual and calculating the average treatment effect using appropriately defined weights (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Li, Chen and Liu2022). Using this enhanced estimator, we obtain qualitatively similar results. Focusing on IMF program participation, we appear to find a small positive contemporaneous effect on the OFD share.Footnote 38 Focusing on Chinese swap lines, we find a significantly positive effect of the swap line being drawn on the OFD share, which becomes more robust once we balance the sample for IMF program participation (Figure A2).

Threats to inference