Chapter 1 Introduction: The Power of Food

It is to serve the farmers of this great open country that teeming cities have arisen, great stretches of navigation have been opened, a mighty network of railways has been constructed, a fast increasing mileage of highways has been laid out, and modern inventions have stretched their lines of communication among all the various communities and into nearly every home. Agriculture holds a position in this country that it was never before able to secure anywhere else on earth. . . . [I]n America, the farm has long since ceased to be associated with a mode of life that could be called rustic. It has become a great industrial enterprise.

[T]oday in cosmopolitan Dublin, you can choose to eat an Indian curry, a Mexican burrito, or an Irish breakfast. With an increasingly global food trade a single meal can originate from ten locations across the planet. . . . In eagerness to minimize the distance our food travels, and connect flavours to places, we may risk over-simplifying the complex systems that comprise our food systems. But, whether one grows local or eats global, food will always be inextricably linked to place; and places are in constant flux.

In 1925, Calvin Coolidge looked out on an audience of farmers and policymakers and effectively broke with the agrarian rhetoric of his predecessors. If Thomas Jefferson imagined the United States to be a nation of yeoman farmers, Coolidge called 150 years later for a rural workforce savvy in “management,” “intricate machinery,” and “marketing.”3 Even as the president announced the arrival of industrial agriculture, his rhetoric anticipated a postindustrial era in which farming would be just one among many “enterprises” constituting the human food chain – what the Harvard Business Review would call in 1956 “agribusiness.”4 The speech captures a new dimension of the American national imaginary, I contend, according to which food and agriculture propel, rather than offer a retreat, from modernity. A concept of the food system thus takes hold in American culture, calling into question what is currently an intellectual separation of agricultural history from food studies.5 At World’s Fairs that took place from the 1930s through the 1960s, the systemic connections between the nation’s farms and kitchens were evident in exhibits about the future of food, which were also very much about the U.S. appetite for international power. These futuristic displays presented a cornucopian nation whose agricultural surpluses and scientific innovations combined to generate a global utopia of edible goods. The Fairs gave symbolic expression to a material reality: the nation’s agricultural economy, in Warren Belasco’s words, “had reached its geographical limits,” and the power Coolidge correlated in 1925 to food production would now require not (or at least not only) territorial expansion but new technologies and new markets.6

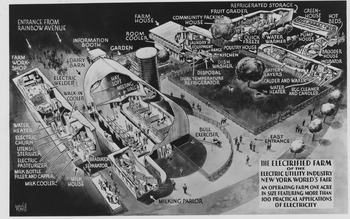

At the same time, a neo-Malthusian streak haunted the American vision of a global food frontier. Plans for futuristic farms and kitchens foresaw a world in which the reduction of farmland and the growth of the human population would make technological fixes vital to manufacturing experiences of culinary abundance out of a handful of staple crops. In the 1960s, the decade in which the Fairs came to an end, American Pop Art painter Tom Wesselmann exposed the rhetoric of American abundance as a fallacy in his “Still Life #30,” a garish painting of a kitchen teeming with food (Figure 1). The apparent cornucopia in the still life is, in fact, a monoculture of consumer brands, while the repetition of packaged meat, bland starches, and canned goods undercuts the colorful kitchen scene and the verdant townscape beyond its open window. Notwithstanding a smattering of vegetables and a bright red apple (whose singularity suggests the post-Edenic character of the Cold War food supply), “Still Life #30” offers a mosaic of culinary monotony. The “Electrified Farm,” which appeared at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, suggests that the conceptual origins of Wesselmann’s homogenous yet overflowing kitchen lie in earlier designs for standardized and productive farms (Figure 2).7 Today, we may not find the push-button farms that engineers forecasted in the thirties, but we can find farmers who spend their time, as novelist Ruth Ozeki pictures a character in All Over Creation (2003), “at a computer, sweating at it, trying to input data and generate readouts and maps.”8 So, too, can we witness a global market for biofuels that require more energy to produce and distribute than the energy they provide.9 In line with Coolidge’s claim that the “network” of railroads, highways, and communication lines served above all to support the industrialization of food production, future-oriented designs like the “Electrified Farm” predicted a time when power would be all too literal as an organizing concept for the modern food system.

1 “Still Life #30.” 1963. Museum of Modern Art, Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen Exhibition.

Since the moment when Coolidge addressed the Farm Bureau, the political and economic power that has accrued to those who control the world food supply has turned out to be an indicator of global power writ large, and the hegemony of the United States has had a great deal to do with food ever since. Today, what I term U.S. food power is both global in scope and subject to manifold forms of opposition: it drives the international adoption of genetically modified seeds (GMOs), but fuels anti-GMO movements and seed-saver organizations; it inspires the post-9/11 revival of “victory gardens” as instruments of national food security, but spurs community supported agriculture (CSA) as a means to make food systems ecologically and socially sustainable; and it enables the global reach of American food brands, but energizes alternative dietary practices. The United States is, moreover, not the world’s sole food power. Nearly a century since Coolidge delivered his speech, the “great industrial enterprise” has taken root in China, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, India, France, and elsewhere, while transnational social movements have mobilized to contest that enterprise. Put simply, food has become a political mobilizer and cultural buzzword. In the United States, the number of protests, activist groups, conferences, books, films, art installations, and websites devoted to food and food politics grows by the year. This popular discourse attests that food both participates in “complex systems,” from regional watersheds to international markets, and circulates in multivalent cultural forms, from traditional genres like almanacs and cookbooks to new media like blogs and bioart experiments. To invoke Roland Barthes, the “polysemia” of food in contemporary society – as in the multiple social and, I would hasten to add, ecological structures it shapes – is a constitutive feature of modernity.10

The reasons for the proliferation of food movements and food media during the last decade are numerous. Perhaps most importantly, environmental groups have publicized scientific findings that industrial agriculture is a major contributor to climate change at the same time that volatility in rice, wheat, and corn prices have highlighted a troubling paradox of the modern food system: despite tremendous gains in the productivity of agriculture, nearly one billion people are hungry.11 The 2012 exhibition Edible: A Taste of Things to Come illustrates another paradox of the modern food system, one that inspires this book: the richness of cultural responses to the system’s perceived failings. Organized by the playful art collective known as the Center for Genomic Gastronomy, the exhibition assembled artists, activists, cooks, scientists, and hobbyists to imagine possible futures of food. With installations like “Disaster Pharming” and “Vegan Ortolan,” the exhibition showcased the outer reaches of molecular gastronomy and agricultural genetics alongside more familiar “countercuisines”12 such as vegetarianism and raw food. In positing these futures, the exhibition was highly critical of the status quo. The Edible catalog concludes with two infographics: one showing disinvestments in small farmers and increases in obesity rates and another charting the decline of agricultural diversity under the industrialized food regime (in which wheat, rice, milk, potatoes, sugar, and corn have displaced the thousands of edible plants long cultivated around the world).13 Paired with this lament about the present, however, is a celebration of the culinary cosmopolitanism that the present affords. De-centering the United States, and indeed the nation state, as the locus of food power, the Edible curators suggest that the global circulation of foodstuffs and food cultures allows the individual eater to act as a world citizen.

Although Global Appetites makes the case for the cultural significance of the modern food system and the power of a nation like the United States within it, U.S. food power in the period since the First World War certainly has historical precedents. Coolidge acknowledged in 1925 that the farm had “long . . . ceased to be associated with a mode of life that could be called rustic.” Broadening his point, we can identify in European empires and in the colonial United States the twin impulses to expand the geographic scale of food distribution and transform the technological apparatus of agriculture. We also can trace back to the ancient world the very forms of cosmopolitan consumption that the Edible exhibition identifies as uniquely modern and urban. Food historian Massimo Montanari observes that the “social expansion of globalization” should not lead us to “forget its ancient origins as a cultural model.”14 At the same time, Montanari contrasts the “infinite local variations” that once defined international cuisines with the current “tendency toward uniformity of consumer goods” that multinational corporations have effectively promoted.15 It is my contention that literature provides a powerful medium through which to chart both the historical continuities and cultural ruptures that inform late modern appetites for world cuisines and national aspirations for global food power.

Moving from the First World War to the post-9/11 era, Global Appetites argues for the centrality of food to accounts of globalization and U.S. hegemony that pervade the literature of this period. Across genres, literature is a vehicle attuned to the modern food system due to the capacity of imaginative texts to shuttle between social and interpersonal registers and between symbolic and embodied expressions of power. Just as importantly, literature has a facility with shifting from macroscopic to intimate scales of representation that can provide an incisive lens on the interactions between local places and global markets that are so central to how communities and corporations produce, exchange, and make use of food in the modern period. While wide-ranging in its primary materials, the book zeroes in on one question: What forms does the writing of food take in the age of American agribusiness? This question proves pertinent to a wide array of texts, from cookbooks that challenge the products and ideologies of fast food to novels that depict the modernity of rural communities. The literature of food that this book maps includes not just culinary writing and agrarian narrative, but also experimental poetry, postmodern fiction, government propaganda, advertising, memoirs, and manifestos. This body of literature takes shape after the First World War, when industrial agriculture really took off in the United States, and gains momentum during the Cold War, a period in which U.S. corporations began to market food brands and packaged foods internationally. Engaging with these historical shifts, writers elucidate and at times challenge what Henry Luce called in 1941 “The American Century.”16 For Luce, the exceptional history of the United States underwrites a national imperative to lead the world in the twentieth century toward the arguably competing goals of “free enterprise” and political “freedom and justice.”17 From Willa Cather to Toni Morrison, the writers whom I discuss in the pages that follow articulate this sense of American exceptionalism, yet often through a negative form that defines the United States as the main origin of imperialist and unjust practices attending the globalization of food.

One could argue that the literary history this book traces reaches back at least to the turn of the century, when writers such as Upton Sinclair and Frank Norris begin to investigate the rise of industrial agriculture and the corporate ownership of food infrastructure. Hsuan Hsu reminds American Studies scholars that 1898 is a particularly pivotal year for the history of U.S. power as a moment when the Spanish-American War crystallized the nation’s imperial aspirations and actions.18 Although writers like Sinclair make cameo appearances in Global Appetites and although I concur with Hsu’s historical argument, I show that it is not until the First World War that a discourse of food power pervades both politics and literature, just as it is then that the methods of industrial agriculture and the products of U.S. food companies pervade the world system.19 Investigating a set of writers who tackle these historical developments, the book contributes to cultural theories of globalization. Since the 1980s, globalization has come to describe a set of institutions, ideologies, and practices that advance modes of border-crossing connectivity – what sociologist Anthony Giddens terms the “disembedding” of communities from local contexts.20 While the term globalization offers a kind of clarity in connoting free trade, mass media, and consumer culture, scholars have employed it in often sharply divergent analyses. As Ursula K. Heise observes in Sense of Place, Sense of Planet, some theorists “see globalization principally as an economic process and as the most recent form of capitalist expansion, whereas others emphasize its political and cultural dimensions, or characterize it as a heterogeneous and uneven process whose various components . . . do not unfold according to the same logic and at the same pace,” an insightful gloss of a field that includes the work of Arjun Appadurai, Ulrich Beck, Daniel Bell, David Harvey, Fredric Jameson, Saskia Sassen, and others.21 The now omnipresent concept of globalization in the social sciences and humanities serves, furthermore, to encapsulate a host of social conditions associated with the contemporary period as well as to synthesize the overlapping historical designations of late modernity (Beck), late capitalism (Harvey), postmodernism (Jameson), postindustrialism (Bell), and postcolonialism (Appadurai and Sassen).

Shifting the lens of globalization inquiry to food, I have come to question a central premise within this body of theory: the idea that globalization separates spaces of production and consumption, intensifying the process Karl Marx termed “commodity fetishism” and giving rise to decolonial modes of resistance to late capitalism (or what Harvey labels the “new imperialism”).22Global Appetites addresses decolonial movements that resist economic globalization, such as those calling for food justice and seed sovereignty. So too does the book credit those late capitalist ideologies – from free trade to global branding – that depend on the geographic and psychic distance between people and that profit from our enchantment with things. Indeed, we see commodity fetishism at work nowhere more clearly than with food. Outside a small if growing subculture, most consumers in the contemporary United States shop weekly at supermarkets, where the labor conditions and environmental consequences of the produce are as hidden as those of the brand-name packages overflowing from the center aisles. If global commodities like a can of Coke and the Big Mac exemplify Marx’s theory, one’s indulgence in a fair-trade-certified bar of chocolate is surely no less an instance of commodity fetishism than the hurried purchase of a fast food meal. However, despite how robustly the modern food system reinforces the idea that globalization is the apotheosis of capitalism, there is a countervailing pattern to apprehend. Globalization, as this book concludes, also provides the imaginative frameworks and material structures for the contemporary movement to re-localize food and reconnect producers and consumers. This contention speaks not only to globalization studies but also to environmental criticism, and especially to recent work that has questioned the centrality of place-based politics and localism in North American environmentalism.23 From Cather’s novel O Pioneers! (1913) to Novella Carpenter’s memoir Farm City (2009), the primary materials I examine span a century to provide a new account of globalization that emerges out of an environmental sensibility at once local and global in its coordinates. Imaginatively reconnecting farmers and eaters ‒ cities and countrysides – the literature of food shows us that the endgame of globalization may not be the free market that the United States has underwritten for decades and backed with its military. Rather, it opens up the possibility that the outcome of globalization may be a postcapitalist system defined by interchanges between regional communities and the global networks that not only fulfill appetites for exotic foods but also circulate the knowledge and resources that advance alternative food movements, from organic agriculture to urban farming.

This thesis informs my analytical methodology, which expands the parameters of food writing beyond taste, the table, and cuisine. I depart from what has been a tendency in the humanities to treat as separate objects of analysis, on the one hand, culinary practices and gastronomical rhetoric and, on the other, agricultural production and agrarian discourse. This intervention informs the predominance of women writers in the book, which emerges out of my finding that the distinction observed between writing about eating and writing about farming is gendered as much as it is formal. Scholars of the American pastoral and agrarian traditions have emphasized male writers, from Frank Norris to Wendell Berry, particularly when their interest is in how rural literature treats the sweeping forces of industrialization and U.S. expansionism. Although Cather is among the exceptions to this pattern, in focusing on her importance to American regionalism, critics tend to diminish her attention to matters national and global in scope. With respect to culinary literature, critics have defined that rhetorical mode primarily around the spaces of the kitchen and the table, thus bracketing it from the wider food system. Rethinking the divide between agriculture and cuisine in literary and cultural studies, I examine a group of women writers whose texts mix formal modes to depict the entanglements of growing, procuring, and consuming food and the interdependencies of food culture and agriculture under globalization.

Food studies scholars such as Warren Belasco, Amy Bentley, Denise Gigante, Harvey Levenstein, and Doris Witt have shown just how significant dietary habits and culinary regimes are to cultural histories of race, class, and gender.24 This scholarship revitalizes structuralist theories of cuisine that Barthes, Mary Douglas, and Claude Lévi-Strauss formulated in the sixties, while also asserting the value of historicist approaches to the study of food.25 That early cohort of structuralist thinkers argued for the social significance of eating by defining food as a system of communication with the capacity to create meaning beyond its “material reality.”26 In turn, their semiotic analyses provided the intellectual foundation for foodways27 to become a subject first in anthropology and cultural geography and, more recently, in the humanities. As Jennifer Fleissner notes, the turn to food in the humanities has focused since the late nineties on reexamining an established philosophical distinction between “aesthetic and gustatory taste,” a distinction Barthes called into question in his seminal comparison of French and American cuisines.28 At the same time, the work of Terry Gifford, Leo Marx, Raymond Williams, and others has made rural culture and agricultural industry important subjects for literary history.29 These scholars demonstrate how multivalent the pastoral tradition is by comparing ideas of rural landscapes that draw on idyllic poetry to realist narratives of farm life that activate the georgic and almanac traditions. The arc and argument of this book are indebted to both of these trajectories within literary and cultural studies. Global Appetites departs from prior scholarship, however, in showing that the history of modernity centers in no small measure on the interactions between places of food production and experiences of food consumption. The book thus recontextualizes Berry’s assertion in “The Pleasures of Eating” that “eating is an agricultural act” by intervening in the localism that his assertion has inspired in sustainable agriculture and related environmental movements.30 In the period that Global Appetites covers, the term food signifies a chain of activities that travels all the way from planting a seed to relishing a square of chocolate and from farms near and far to one’s evening meal.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the literature of food breaks from two genres that map onto the scholarly gap I am identifying between studies of the culinary and studies of the agricultural: namely, gastronomical primers focusing on taste and fine dining and pastoral narratives about the relative simplicity of rural life. Although both genres remain active, as we will see, new cultural templates emerge alongside them to articulate how the social structures and experiential realities of food most change with the rise of factory farms and branded foods. My aim is to define these templates and situate them within the social, technological, and environmental histories of food in the context of agribusiness and in the related context of globalization. Chapter 2 elaborates on this keyword of agribusiness through a reconsideration of Cather’s Nebraska novels O Pioneers!, My Ántonia (1918), and One of Ours (1922). Central to these novels is a story of rural modernity: a sense of agrarian communities as new sites for industrial infrastructure and consumer culture that Coolidge lauded in 1925. Although her fiction conveys ambivalence about the modernity of rural life, Cather disturbs the myth of the United States as a nation of smallholding pioneers by chronicling the importance of modern farms and farmhouses to the nation’s expansionism in the first decades of the twentieth century. The “great industrial enterprise” of food became even more interwoven with U.S. global power during the Second World War, as evident in propaganda that made the productivity of farms and efficiency of kitchens vital to the Allied war effort and to U.S. economic growth. By 1945, the United States had become the world’s largest food exporter.31 Challenging the imperialist character of wartime and postwar food rhetoric, writers on both sides of the Atlantic lay bare what they saw as a growing rather than diminishing stratification of the world’s edible resources. These mid-century writers politicize modernism by juxtaposing rhetorical assertions of American abundance to lived experiences of hunger within and outside the United States. Chapter 3 develops this argument through discussions of the experimental lyrics of Lorine Niedecker, the unconventional culinary writings of M. F. K. Fisher and Elizabeth David, and the absurdist theater of Samuel Beckett (an arguable outlier in this group of writers, but one who makes poignantly visible not only mid-century famine, through the existential sparseness of his stage and the meager rations of his tramps Vladimir and Estragon, but also the power of those – like Pozzo and Godot – who control agricultural land).

The second half of the book turns to contemporary novelists and journalists whose accounts of globalization in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries revolve around agricultural corporations and cosmopolitan consumers as well as countercultural food practices that aspire to disrupt American agribusiness. Chapter 4 focuses on Morrison’s 1981 novel Tar Baby, which is set on a fictionalized Caribbean island that Philadelphia candy executive Valerian Street develops into an enclave of vacation estates. A novel that speaks to the environmental justice movement, Tar Baby links bodily desires for exotic foods – chocolate and other delicacies – to the historical forces that give rise to the supermarket and its promise of plenty. Extending the mid-century dialectic of “luxury feeding”32 and physical hunger, the novel offers a searing critique of free trade that moves from the hemispheric impact of U.S. food companies on the agriculture of island states to everyday acts of food indulgence and food resistance. The chapter has a distinct position in the arc of Global Appetites, as it breaks from the focus on the interconnections of world war and American agribusiness that centrally informs the first half of the book and that returns in Chapter 5. The role of Tar Baby in the book is to move us geographically beyond the United States to refract through a hemispheric lens the image of the world food system as a new frontier for U.S. farmers, corporations, and consumers. In this sense, the chapter builds out my transnational framework for U.S. food power while deepening the book’s historical arc. Published during the period when neoliberal ideologies of free trade were coming to the foreground of U.S. foreign policy, Morrison’s novel de-centers the United States not just by homing in on the Caribbean but also by showing that the spectral origins of U.S. food power lie in colonial histories of empire, botanical prospecting, and slavery.

Turning from chocolate to meat and from the Caribbean to the Pacific Rim, Chapter 5 puts Ozeki’s satirical novels My Year of Meats (1998) and All Over Creation in the context of recent muckraking exposés of the American factory farm. Although the meat industry garnered scant attention in the decades after Upton Sinclair published The Jungle (1906), this inattention turned to alarm at century’s end as environmental groups publicized the brutal working conditions and animal abuses of confined feedlots along with their ecological impacts as a major contributor (via methane pollution) to climate change. The chapter concentrates on My Year of Meats, which critics have read as a feminist narrative in which cosmopolitan bonds among women provide an antidote to late capitalism. While critics have focused on parsing Ozeki’s political allegiances to third-wave feminism and to slow food, I reframe the analysis of her novels around their formal strategies of pastiche and satire. Through these formal methods, Ozeki illuminates contemporary conflicts between postindustrial agriculture and localist food movements. Similar to Tar Baby, My Year of Meats extends the geography of the industrialized food system and its postindustrial developments beyond the transatlantic horizons of Chapters 2 and 3. Her narrative of the U.S.-Japan meat trade, in particular, is a story that takes the reader back to the postwar occupation of Japan to satirize the rhetoric of an American meat-and-grain diet, which presented that diet as an engine of both bodily and national power during the Cold War.

As for the book’s principles of selection, two additional points merit explanation. First, I exclude two writers whom readers may expect to encounter: John Steinbeck and Jane Smiley. Although these quintessential novelists of American farm work and rural culture address the industrialization of agriculture, neither Steinbeck in the first half of the twentieth century nor Smiley in the contemporary period takes up the dialectic of farming and eating or the global horizons of the U.S. food system – the twin concerns that animate Global Appetites. Even though I have chosen not to give these writers prominence, the book does offer a launching point for a reexamination of American regionalism. Second, while my focus is on U.S. literature, each chapter develops a transnational context for the topic at hand. This approach follows from my claim that the literature of food coheres in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries around conflicts as well as synergies among the local, the national, and the global. Chapter 4 thus situates an analysis of the cosmopolitan food tastes and neocolonial food politics that inflect Tar Baby in relationship to Columbus’s Voyages, on the one hand, and Édouard Glissant’s postcolonial writings, on the other. That said, Chapter 3 is the only place where I treat at length writers from outside the United States; there, discussions of Beckett and David show how a creeping U.S. hegemony structures mid-century representations of food power on either side of the Atlantic.33

The idea for this book originated with my observation that pastoral tropes have come to structure much of the contemporary discourse surrounding American agribusiness. The persistence of pastoral sensibilities in the information age extends out from the marketing campaigns of companies such as Foster Farms, Chipotle, and Horizon organic milk to, on the one hand, apologies for GMOs and, on the other, polemics for farmers’ markets and whole foods. This pastoral turn has a specific flavor, however. Although in some instances contemporary food rhetoric features idyllic images of shepherds and meadows, more often it reaches back to a classical georgic tradition that sees food as melding the natural, the cultural, and the technological. This georgic streak today pops up in cultural forms as divergent as molecular gastronomy cuisine, avant-garde bioart, and the agribusiness exposés of writers such as Jonathan Safran Foer and Eric Schlosser.34

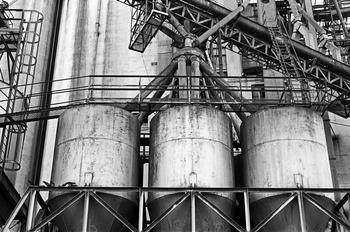

In contrast to this recent renaissance of georgic notions of food, the first half of “The American Century” tended to the modernist veneration of industrialized agriculture that we see in Coolidge’s 1925 speech. This vision of an engineered food system severed, thru technical fixes, from the unpredictability of natural ecosystems and the diversity of culinary traditions redoubled during the Cold War. In 1968, USAID Administrator William Gaud coined the now notorious moniker of the Green Revolution, a term that categorized the multiple industries constituting agribusiness – from seed companies and pesticide manufacturers to food science labs and packaged food makers – as participants in a humanitarian project to solve world famine. In line with the Nobel Prize winning scientist Norman Borlaug, Gaud suggested that the same compounds that had gone into chemical weapons (DDT most infamously) were migrating from combat zones to fields of grain, where they would serve the common good. The Green Revolution failed to realize this political promise for its critics, who instead saw its end result as a global trade in pesticides, fertilizers, and seeds that produced skyrocketing farmer debt and eroded regional food traditions.35 The amalgamation of weapons production and agribusiness began during the First World War, when chemical gas and barbed wire simultaneously structured the trenches of Europe and the industrializing farms of the American Midwest. The tacit alliance between war and food accelerated in the fifties and sixties, when corporations began marketing chemical inputs to farmers as part of the Green Revolution while supplying the Department of Defense with weapons such as Agent Orange. In our own historical moment, we can witness this militarization of the food system in the physical infrastructure that has developed to support American agribusiness for nearly a century. A 2008 photograph of a California feed mill showing an intricate series of pipes and silos, brings powerfully to mind – in the mill’s scale and complexity – what Dwight D. Eisenhower termed in 1961 the “military-industrial complex” (Figure 3).36 To quote food journalist Michael Pollan, agribusiness has aimed throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first to put the national “war machine to peacetime purposes.”37

3 “Feed Mill, California 2008.”

The multinational corporation Monsanto provides a window onto the important cultural shift that occurred between the Cold War and the early twenty-first century – the transition from the modernist exaltation to the georgic redefinition of agribusiness.38 Founded in 1901, Monsanto got its start manufacturing saccharin and caffeine, growing rapidly during the century into nearly every realm of commercial chemistry. By the start of the Cold War, Monsanto had outpaced its identity as a “Chemical Works” and rebranded itself a life science research firm, adding to its product portfolio hybrid seeds, synthetic pesticides, and, beginning in 1982, the first commercial GMOs.39 In mid-century advertisements for household plastics, Monsanto extolled the synthetic quality of Green Revolution technologies and advanced the idea that technology would transform not just farms but everyday spaces of eating. One Saturday Evening Post advertisement features a family of four standing in their living room, where an assembly line of red, yellow, and green plastics is laid out before them.40 With the tagline “for happier picnicking days,” the ad suggests that consumers have no need of open space or fresh food but instead can take pleasure in the convenience of disposable plastics.

In the 1960s, while Monsanto was crafting a national brand identity as a company that brought dazzling technologies to both farms and kitchens, the biologist Rachel Carson became one of Monsanto’s first public critics. Her famous exposé Silent Spring (1962) interweaves scientific data with pastoral and apocalyptic narrative to document the pernicious effects of agribusiness, describing the net impact of DDT and other chemical compounds as a worldwide alteration of the human food chain and the ecosystems supporting it.41 Monsanto evidently perceived Silent Spring as a pressing public relations threat, a perception that prompted the company to publish a 1962 parody of Carson’s opening chapter in an internal newsletter. Entitled “A Desolate Year,” the parody rejoins Silent Spring with a story of apocalyptic blight caused not by pesticides but by pests.42 Although Carson’s environmental activism and Monsanto’s business model could not have been more opposed, both drew on a similar logic according to which the modern food system culminates in a fully industrialized and technologically amended system. In the case of Silent Spring, this telos inspires not colorful images of agricultural and alimentary bounty but dystopian anxieties about environmental and somatic crises. Carson, to this point, connects her frequent trope of pesticides-as-weapons to a sense that the suburban American home has joined forces with the chemically fueled farm. Alluding to Monsanto’s kitchen plastics and home gardening chemicals, Carson takes U.S. consumer culture to task for “the use of poisons in the kitchen,” “the fad of gardening by poisons,” and the presence of pesticide-laden foods on supermarket shelves.43

As of 2009, Monsanto stood among the most profitable companies in the world, with revenues representing one-fourth of the global agrochemical industry, one-tenth of the commercial seed industry, and an estimated 90 percent of the GMO market – a monopoly that led the U.S. Justice Department to launch an antitrust investigation.44 During the last fifty years, the rhetoric that supports Monsanto’s power has moved from the modernist valuation of synthetic technologies to a quasi-pastoral image of transgenic seeds. This observation resonates with Belasco’s analysis of “recombinant culture” – a conceptual framework for prototyping food technologies that combine nostalgia with novelty. This framework comes to the fore, he shows, in the 1990s and 2000s.45 Exploiting the current appeal of products that recombine the pastoral (or artisanal) and the postindustrial (or high-tech), Monsanto spins a vision of GMOs that downplays both the company’s R&D investments and the environmental risks some of their biotechnologies may pose, and it does so by presenting GMOs as an extension of, rather than a radical break from, ancient constructions of agriculture.

Through its “Imagine™” rebranding effort (launched in 2003), Monsanto draws explicitly on georgic motifs to articulate a green vision of its technologies. The logo that accompanies the “Imagine™” tagline features the company’s name adjacent to an evergreen-colored vine, perhaps one of the most archetypal of images in georgic literature dating back to Virgil’s Georgics. Monsanto’s visual mark advances an ethic of corporate environmental responsibility and depicts the continuity of the organic world and agricultural biotechnology. However, the press kit announcing the new brand identity also endorses Monsanto’s technical virtuosity: “The new Monsanto tagline, Imagine, emphasizes the ‘ag’ in Imagine and reflects the company’s strategic focus on investing in and developing new agronomic tools. Monsanto is committed to researching new agronomic systems that are more environmentally sustainable and that will deliver value across the agricultural chain.”46 In advertisements that the company has run since launching “Imagine,” Monsanto continues to leverage georgic ideas of agriculture as a careful balance of nature and techne. Consider, for example, a recent print marketing campaign that ran in The New Yorker and New Republic for Monsanto’s most successful GMOs: Roundup Ready soy and Bt corn.47 Directed at consumers anxious about the rise of a technology that remains unlabeled and hence invisible, the advertisement intimates that Monsanto’s patented seed technologies are safe to eaters by suggesting GMOs synchronize with ecological cycles even as their engineered traits serve to “squeeze more food” from the environment.48

The pastoral mode – whether in its idyllic or georgic form – has perhaps always worked to mask the environmental, somatic, and social consequences of the technological interventions that have long characterized agriculture. In the contemporary period, however, the gap between rhetoric and praxis undergoes a categorical shift. Although farmers have for millennia altered plant and animal genetics, the arrival of transgenic crops represents a major change in the technologies of food production and, by extension, in the stories we tell about food. Monsanto’s planned release of the so-called terminator gene, for example, would prevent farmers from saving seeds for future plantings, an ancient and economical practice.49 Signaling a threat to seed saving, this spectral technology has prompted legal battles over the authority of corporations to predetermine how communities grow and harvest food. Monsanto has vacillated in press releases about the fate of the terminator gene, which has only exacerbated concerns over the ecological risks and social injustices it embodies for opponents. As long as Monsanto officially withholds the technology, scientists are unable to test its effects and, hence, are unable to quell dystopian accounts of the terminator gene that have gone viral. Environmental activists meanwhile have alleged that Monsanto has incorporated the gene covertly into existing transgenic seeds. Conflicts such as the one over the terminator gene are, I argue, about narrative flows of information and misinformation as well as material flows of food and food technologies. In an elegant critique of GMOs, Anne-Lise François highlights the literariness of both agribusiness and countercultural food movements. She defines Monsanto’s vision for GMOs, as I do, to be a teleological one that culminates in a “genetically engineered bioculture” wherein corporations determine which genetic traits and even which species will persist in the future.50 Her analysis suggests, however, that the story of food in biotechnical times is “ongoing and unfinished” and, hence, invites counter-narratives.

From the advertising campaigns of Monsanto to the jeremiads of anti-GMO activists, contemporary food discourse reanimates long-standing pastoral narratives. However, in this discourse we can also recognize an emergent narrative of the information-intensive and networked structure of food in the twenty-first century. Positing the network society as the most apt descriptor of globalization, Manuel Castells speculates that the “informational, global economy” organizes around “command and control centers able to coordinate, innovate, and manage the intertwined activities of networks of firms.”51 For Castells, those who manage information are “at the core of all economic processes.”52Global Appetites demonstrates that these information and communication networks are also at the core of the food system. During the industrial revolution, American literature oriented around what Leo Marx termed “the machine in the garden”: a pastoral trope through which writers could acknowledge “unprecedented” appearances of technologies like the railroad and the telegraph in rural places.53 For writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne, however, technology interrupts the rural scene without completely altering the cognitive difference between the city and the country. In the postindustrial era of networks, the boundary between the lab and the field all but disappears and the rural landscape is as likely to host a server farm as a field of grain. As a result, the recourse to pastoral tropes, even georgic ones, rings increasingly hollow. Contemporary representations of the food system thus reorient around a double recognition that the rural no longer provides a retreat from technological and economic networks and that the future of food production may move from the farms of the countryside to the vertical greenhouses and biotech labs of the city. I term this recognition the “postindustrial pastoral.”54

One strain of the postindustrial pastoral concerns the global networks of people, places, and things found in the supermarket – an idea Morrison’s Tar Baby as well as Allen Ginsberg’s iconic poem “A Supermarket in California” explore. In his blockbuster book The Omnivore’s Dilemma (2006), Pollan coins the term “supermarket pastoral” but restricts its use to organic food marketing: the “grocery store poems” that, contra Ginsberg’s surreal description of the imported foods and immigrant communities populating a Berkeley supermarket at night, tap into consumer nostalgia for quaint dairies in Wisconsin and verdant fields in Iowa.55 The supermarket pastoral is not limited to a sentimental and commercial mode, however. Consider the kitchen of Oedipa Maas in Thomas Pynchon’s novella The Crying of Lot 49 (1965):

Oedipa had been named also to execute the will in a codicil dated a year ago. She tried to think back to whether anything unusual had happened around then. Through the rest of the afternoon, through her trip to the market in downtown Kinneret-Among-The-Pines to buy ricotta and listen to the Muzak . . .; then through the sunned gathering of her marjoram and sweet basil from the herb garden, reading of book reviews in the latest Scientific American, into the layering of a lasagna, garlicking of a bread, tearing up of romaine leaves, eventually, oven on, into the mixing of the twilight’s whiskey sours against the arrival of her husband, Wendell (‘Mucho’) Maas from work, she wondered, wondered.56

In its lyrical key, the scene invokes an elegiac sense of a lost georgic landscape: the citrus farms of Southern California eclipsed by master-planned communities. In its postindustrial key, however, Pynchon spoofs the fantasy of integrating bucolic landscapes into the logic of suburban convenience and the metropolitan infrastructure of freeways, mass media, and strip malls. Oedipa’s herb garden is strictly décor, in other words, garnish for food bought at the gleaming “Kinneret-Among-The-Pines” supermarket and a visual accompaniment to the easy-listening tunes piped in to her suburban world.

Global Appetites concludes with a genre of contemporary nonfiction that seeks to integrate pastoral ideas of rural life into a polemic for local food. Yet this polemic – and practice – of revitalizing local food systems is partly made possible by the very networks of information, technology, and trade that its authors seem to discredit (but that a postmodern novelist like Pynchon would likely say are impossible to escape). I call this genre the “locavore memoir,” adapting the term that has come to signify the 100-mile-radius and kindred diets in the United States. An early adopter of this popular form, ethnobotanist Gary Paul Nabhan documents in Coming Home to Eat (2002) a fifteen-month commitment to grow, forage, barter, and otherwise consume only foods native to the Sonoran Desert region where he lives. He contextualizes this experiment as a protest of free trade institutions and American agribusiness.57 In the more recent Farm City, Carpenter – a self-proclaimed urban farmer living in inner-city Oakland – documents her own decision to feed herself “exclusively off of [her] urban farm” for a single, and tortuously coffee-free, month.58 On its surface, the locavore memoir advocates a radical extraction of the individual eater from the global food system. However, even as these writers give voice to just such a cultural practice, their language of eating locally and knowing where one’s food comes from has made its way into fast food menus and national farm policy debates. Furthermore, locavores like Nabhan and Carpenter depend on seed and livestock networks and also participate in political coalitions that are global in scope and networked in structure. To this point, it is difficult to imagine how a “greenhorn” like Carpenter could have turned a vacant lot into an urban farm, complete with chickens and two pigs, in a time before computing technologies and online communities. By the close of the century this book examines, globalization makes available modes of production and tools of interconnection that no longer serve only agribusiness. The literature of food no doubt continues to spotlight the detrimental consequences of globalization and the culpability of the United States in advancing the “great industrial enterprise” Coolidge eagerly described nearly ninety years ago. At the same time, twenty-first-century writers and their activist compatriots are today re-positioning food practices that resist the globalization of agribusiness within networks of people, places, technologies, and appetites that are themselves global in nature.