1 Introduction

The transition to computer-based testing and digital assessments in various testing programs began in the early 2000s. Recent technological advancements and evolving educational needs have driven the widespread use of these digital assessments (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Persky, Weiss and Jenkins2007; Thurlow et al., Reference Thurlow, Lazarus, Albus and Hodgson2010). A key feature of digital assessments is the collection of process data—information on all of the responses about test-takers’ interactions with computer devices during the test. Process data include real-time responses and actions, such as mouse clicks, keystrokes, response times, and behaviors related to testing accommodations (Bergner & von Davier, Reference Bergner and von Davier2018). Not surprisingly, the rich and detailed information from these data helps researchers understand test-takers’ problem-solving behaviors and their engagement with accessibility tools and testing accommodations. While research using process data has been actively conducted for tasks, such as ability estimation and cheating detection (Jiao et al., Reference Jiao, He and Veldkamp2021), its methods and applications to causal inquiry are still in their early stages. The overarching goal of this article is to propose a causal framework with time-stamped process data to assess the dynamic causal effects of test-related or educational programs.

As a concrete example, consider evaluating the effect of extended time accommodations (ETAs), the most frequently provided accommodation to students with disabilities and/or English language learners. Previous studies (Lee & Suk, Reference Lee and Suk2025; Suk & Kim, Reference Suk and Kim2025; Wei & Zhang, Reference Wei and Zhang2023) used process data to identify whether students who received ETA made use of it during a test and, with this variable, evaluated the effects of using ETA on test scores through different quasi-experimental designs (see Section 2.1 for details). However, these studies focus on test-takers’ final outcomes measured at the end of a test or session and overlook their functional nature over time. It is possible that ETA treatment groups may not differ in terms of final outcomes, but may show temporal or consistent differences during specific periods of testing. Capturing such changes requires researchers to analyze evolving test scores over time rather than the final test scores and view the former as functional outcomes from the field of functional data analysis (Ramsay & Silverman, Reference Ramsay and Silverman2005; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chiou and Müller2016). Briefly, functional data are defined as data that change over a continuous domain (e.g., time and space), and each unit’s outcome is typically a function or a curve that varies over a continuum rather than a single discrete point. Regression models for such functional outcomes try to capture evolving patterns like time-dependent processes or two-dimensional images (Ramsay & Silverman, Reference Ramsay and Silverman2005) (see Section 2.2 for more details on functional data). However, there is still an open question as to how to analyze process data in a functional format to draw causal inferences.

Moreover, the rich information from process data has the potential to uncover the causal mechanisms in digital assessments, i.e., how and why educational programs influence an outcome. For example, previous studies on the ETA evaluation (e.g., Lee & Suk, Reference Lee and Suk2025; Suk & Kim, Reference Suk and Kim2025) assume that the effect of ETA on an outcome manifests only by using it. However, changes in outcomes may result either from using ETA (i.e., indirect effect) or from receiving ETA itself, not through its actual use (i.e., direct effect). This direct effect captures some psychological benefits of receiving ETA, even if the ETA itself is not actually used. For example, the ETA availability can positively affect student performance by reducing anxiety (Lovett & Leja, Reference Lovett and Leja2013). The direct and indirect effects may also vary depending on subgroups defined by test-takers’ characteristics (e.g., disability status and gender). Investigating both direct and indirect effects and conducting their subgroup/moderation analysis helps gain a more nuanced understanding of program effects. While existing causal tools on causal mediation (e.g., Pearl, Reference Pearl2001) and subgroup analysis (e.g., Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lorenzi, Papadogeorgou, Wojdyla, Li and Thomas2021) can support such investigations, a systematic methodology is still needed to extend these tools to the functional data context, in order to capture dynamic aspects of direct and indirect effects using process data in a functional format.

This article proposes a novel causal mediation framework with a functional outcome to evaluate test-related or educational programs in process data. The proposed framework provides the counterfactual definitions for the functional natural direct and indirect effects, and their total average effect. For subgroup analysis, we define these functional effects among subgroups determined by a subset of pre-treatment covariates. We also provide nonparametric identification strategies for each effect depending on the presence or absence of post-treatment confounders and construct estimation methods using generalized additive models (GAMs; Hastie & Tibshirani, Reference Hastie and Tibshirani1986), a flexible and robust tool for analyzing functional data. Through a simulation study, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed GAM-based methods by comparing them with parametric regression methods. Furthermore, we apply our framework to examine the effects of ETA on two functional outcomes—evolving test scores and evolving item access—using process data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP).

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and highlights our contributions. Section 3 describes the study setup. Section 4 outlines our causal mediation framework with a functional outcome by building on the existing causal mediation literature. Section 5 describes the design and results of our simulation study, and Section 6 demonstrates our framework to evaluate the effects of ETA in the NAEP process data. Finally, Section 7 discusses the implications and conclusions of this study.

2 Prior work and our goals

2.1 Causal inference with process data

Most of the research efforts using process data from digital assessments have focused on estimating ability parameters, facilitating cognitive diagnosis, and detecting aberrant responding behavior (Jiao et al., Reference Jiao, He and Veldkamp2021). However, only a few studies have used process data to explore causal questions about students’ testing behaviors or test-related programs. For example, Wei and Zhang (Reference Wei and Zhang2023) use a propensity score method to balance covariates across three distinct profiles of students with learning disabilities: those who do not receive ETA, those who receive ETA but do not use it, and those who both receive and use ETA. They construct students’ ETA use status based on the NAEP process data by comparing their total response time with the standard testing time, and then analyze the math performance among the three profiles. However, Suk and Kim (Reference Suk and Kim2025) suggest using a fuzzy regression discontinuity design with multiple control groups to evaluate the effects of using ETA near the cutoff of a running variable. In their approach, the ETA eligibility status serves as an instrumental variable, and the effect bounds are constructed using multiple control groups. More specifically, the running variable is the English proficiency levels of English language learners, and multiple control groups occur because students either do not receive ETA or decline to use it when offered. Using the NAEP process data, they construct the ETA use status similarly to Wei and Zhang (Reference Wei and Zhang2023) and find no strong evidence of using ETA on the final test scores among a subpopulation.

Additionally, Lee and Suk (Reference Lee and Suk2025) propose an evidence factor analysis in fuzzy regression discontinuity designs to reinforce causal conclusions on the effect of using ETA within a single dataset. Evidence factors represent two or more independent tests of the same null hypothesis about the treatment effect within a single dataset, each potentially subject to different biases (Rosenbaum, Reference Rosenbaum2010). They also use the NAEP process data to demonstrate how to construct and combine three evidence factors in the ETA example, and as a result, there is no strong evidence of the effect of using ETA on the final test scores.

Although these prior studies have utilized process data to find causal evidence on students’ behaviors or testing programs, they have only incorporated a limited portion of process data into causal research, without fully using time information. These studies also assume that the treatment effect manifests only by using it and ignore the potential direct effect of receiving it, not mediated by its actual use. Therefore, there is a need to develop a rigorous methodology for analyzing time-stamped process data to draw causal inferences and discover the underlying mechanisms.

2.2 Causal inference with functional data

In classical statistical methods, the fundamental observational unit is typically a scalar or a vector of fixed length. However, with advances in technologies, observational units can take more complex forms, such as functions, curves, images, or other objects that vary over a continuum. Functional data analysis is a branch of statistics specifically developed to handle such non-scalar data. For simplicity, we will refer to these complex objects as “functions” throughout the manuscript. For example, in NAEP process data, one might traditionally analyze only the final math test score using classical statistical methods, say using a linear regression that regresses the final test score on other covariates. However, if process data capture the entire trajectory of the evolving test score over time, it can be viewed as a function over the testing period. Such functional observations can preserve the full temporal dynamics of test-taking processes.

With the shift in the observational unit, the goals of functional data analysis include understanding relationships, making predictions, and identifying patterns with functional variables. In this field, methodological advances have been made to more effectively address the high dimensionality and inherent complexity of functional data. Key developments include functional principal component analysis, functional regression with functional outcomes and/or functional predictors, and clustering of functional data (Crainiceanu et al., Reference Crainiceanu, Goldsmith, Leroux and Cui2024; Ramsay & Silverman, Reference Ramsay and Silverman2005; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chiou and Müller2016). However, most existing studies are limited to exploring associations rather than causal relationships, and the development of causal inference techniques with such functional data is in its infancy.

Recently, some notable work has been developed. Ecker et al. (Reference Ecker, de Luna and Schelin2023) introduce a causal framework with a functional outcome (e.g., cumulative lifetime incomes) and a scalar binary treatment (e.g., residing in urban versus rural areas) to target the functional average treatment effect (FATE), i.e., the average treatment effect (ATE) over the functional domain. They extend the standard causal assumptions (consistency, positivity, and ignorability/unconfoundedness) to the functional data context to identify the FATE. Ecker et al. (Reference Ecker, de Luna and Schelin2023) use functional linear regression as the outcome model to estimate the FATE and develop simultaneous confidence bands for valid inference across the functional domain. They also examine the subgroup effects of FATE to find effect heterogeneity, say between males versus females. In contrast, Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Wang, Hu and Sun2024) propose a causal framework with a functional treatment (e.g., hippocampal changes over time) and time-to-event (survival) outcomes (e.g., time until conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease). They define the target estimand as the coefficient of functional treatment in a type of functional linear regression model and provide three estimation methods, including regression methods, weighting methods, and combinations of these.

Since process data are collected over a specific time period, it can be considered a type of functional data. As such, causal inference methods for functional data could be applied to evaluate the effects of students’ testing behaviors or test-related programs on the functional outcomes, such as evolving test scores. However, we need additional considerations to accurately establish a functional causal framework for process data. For example, process data from digital-based assessments may require additional assumptions for causal identification due to the unique nature of assignment and outcome processes in digital environments (e.g., one-sided noncompliance and constant potential outcomes over a certain period). Furthermore, while existing studies (Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, de Luna and Schelin2023; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Wang, Hu and Sun2024) focus on estimating the FATE (or a type of ATE), they are limited in investigating causal mechanisms through mediators across the functional domain. In cases where researchers wish to decompose the total effect into direct and indirect effects in functional data, they need to develop a new framework and methods for causal mediation with functional data.

2.3 The goals of this article

To address the limitations of existing approaches, this article seeks to develop a new causal mediation framework for functional outcomes derived from process data. Specifically, we pursue the following four goals.

First, we aim to re-conceptualize process data as functional outcomes. While researchers in education and psychology often interpret evolving outcomes (e.g., test scores recorded during a test) as repeated discrete outcomes within a longitudinal framework, we adopt a functional data perspective. Under this paradigm, evolving test scores are treated as realizations of an underlying continuous process, where the study unit is an individual’s entire outcome trajectory rather than time-point measurements. This functional view is more appropriate for process data and marks a conceptual shift that is relatively new to the fields of psychology and education. We illustrate this shift using a motivating example of ETA, which serves as the empirical context throughout the manuscript.

Second, we aim to define causal estimands that uncover dynamic causal mechanisms over a functional domain (e.g., time or space). Specifically, we define the average functional indirect and direct effects, along with their subgroups effects, where the subgroups are defined by a subset of pre-treatment covariates (see Equations (1)–(4) for details). The resulting framework enables researchers to effectively answer the causal question: “Why, when, and for whom does a program work?” The “why” component concerns causal mechanisms through direct and indirect pathways; the “when” component captures how effects evolve over the functional domain; and the “whom” component addresses subgroup effects beyond the ATE. When the functional domain corresponds to space, our framework can also address where a program is effective.

Third, we aim to establish identification strategies under several realistic scenarios, including: (i) the presence or absence of post-treatment confounders, (ii) mediators derived from other variables, and (iii) one-sided versus two-sided noncompliance. In particular, the presence of post-treatment confounders requires jointly modeling the mediator and post-treatment confounders. We outline the identification assumptions that are most relevant to our process data setting in the main text, while providing detailed identification results for each scenario in the appendices of the Supplementary Material to broaden the applicability of our approach.

Fourth, we aim to develop estimation and inference procedures for functional causal effects using GAMs. GAMs are widely used in functional data analysis due to their flexibility and adaptivity (Crainiceanu et al., Reference Crainiceanu, Goldsmith, Leroux and Cui2024; Ramsay & Silverman, Reference Ramsay and Silverman2005). We leverage GAMs to construct estimators for our functional direct and indirect effects. Importantly, our estimators go beyond fitting outcome regression by incorporating carefully designed weighting schemes to account for post-treatment variables. For inference, we employ a cluster bootstrap that resamples individuals, rather than time points, to consider unit-specific serial dependence. Through simulation studies, we demonstrate that our GAM-based methods achieve a favorable bias–variance trade-off and perform at least as well as correctly specified parametric methods.

3 Setting

3.1 Notation

Let

![]() $i = 1, \ldots , n$

index subjects, i.e., study units. We suppress the subscript i unless necessary. We consider a setting where the following variables are available for subject i from functional data. We denote the treatment receipt variable as

$i = 1, \ldots , n$

index subjects, i.e., study units. We suppress the subscript i unless necessary. We consider a setting where the following variables are available for subject i from functional data. We denote the treatment receipt variable as

![]() $Z \in \{0, 1\}$

, where

$Z \in \{0, 1\}$

, where

![]() $Z = 1$

indicates that a subject received the treatment and

$Z = 1$

indicates that a subject received the treatment and

![]() $Z=0$

indicates that the subject did not receive it. We denote a set of pre-treatment covariates as

$Z=0$

indicates that the subject did not receive it. We denote a set of pre-treatment covariates as

![]() $X=\{X_{1}, \ldots , X_{p}\} \in \mathbb {R}^{p}$

. We also denote the observed outcome process as

$X=\{X_{1}, \ldots , X_{p}\} \in \mathbb {R}^{p}$

. We also denote the observed outcome process as

![]() $Y(\mathcal {K}) = \{Y(k): k \in \mathcal {K}=[k_0, k_m] \} $

, where

$Y(\mathcal {K}) = \{Y(k): k \in \mathcal {K}=[k_0, k_m] \} $

, where

![]() $k_0$

and

$k_0$

and

![]() $k_m$

represent the minimum and maximum values of the functional domain

$k_m$

represent the minimum and maximum values of the functional domain

![]() $\mathcal {K}$

, respectively. The minimum value

$\mathcal {K}$

, respectively. The minimum value

![]() $k_0$

plays a key role in the definition and identification of the functional causal effects (see Section 4 for details). Additionally,

$k_0$

plays a key role in the definition and identification of the functional causal effects (see Section 4 for details). Additionally,

![]() $W = \{W_1, \ldots , W_{q}\} \in \mathbb {R}^{q}$

denotes the observed post-treatment covariates by time

$W = \{W_1, \ldots , W_{q}\} \in \mathbb {R}^{q}$

denotes the observed post-treatment covariates by time

![]() $k_0$

(e.g., the number of accessed items up to

$k_0$

(e.g., the number of accessed items up to

![]() $k_0$

).

$k_0$

).

For causal mediation analysis with functional data from digital assessments, we introduce additional variables. Let

![]() $T \in \{0, 1\}$

denote the actual treatment use, where

$T \in \{0, 1\}$

denote the actual treatment use, where

![]() $T = 1$

indicates that a subject used the treatment and

$T = 1$

indicates that a subject used the treatment and

![]() $T=0$

indicates that the subject did not use it. Here, T and Z differ because subjects who receive the treatment can decide whether to use it, and T serves as a mediator. We denote a subject’s total response time as

$T=0$

indicates that the subject did not use it. Here, T and Z differ because subjects who receive the treatment can decide whether to use it, and T serves as a mediator. We denote a subject’s total response time as

![]() $H \in \mathcal {K}$

. In particular, we observe the outcome process

$H \in \mathcal {K}$

. In particular, we observe the outcome process

![]() $Y(k)$

over

$Y(k)$

over

![]() $k \in [k_0, H]$

, where the last observation ends at time H, and we use H to derive the treatment use variable as

$k \in [k_0, H]$

, where the last observation ends at time H, and we use H to derive the treatment use variable as ![]() . Therefore, the observed data for a subject consists of

. Therefore, the observed data for a subject consists of

![]() $(X,Z,T,H,W,Y([k_0,H]) )$

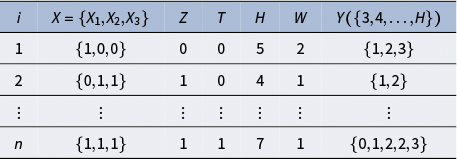

(see Table 1 for the structure of the process data). In Table 1, the first subject (

$(X,Z,T,H,W,Y([k_0,H]) )$

(see Table 1 for the structure of the process data). In Table 1, the first subject (

![]() $i=1$

) has three covariates

$i=1$

) has three covariates

![]() $\{X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{3}\}$

with values {1, 0, 0}, an ETA receipt status of

$\{X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{3}\}$

with values {1, 0, 0}, an ETA receipt status of

![]() $Z=0$

(did not receive), an ETA use status of

$Z=0$

(did not receive), an ETA use status of

![]() $T=0$

(did not use), and a total response time of

$T=0$

(did not use), and a total response time of

![]() $H=5$

minutes. Under

$H=5$

minutes. Under

![]() $k_0=3$

, this student’s post-treatment covariate is observed as

$k_0=3$

, this student’s post-treatment covariate is observed as

![]() $W=2$

. Their functional outcome Y is observed from

$W=2$

. Their functional outcome Y is observed from

![]() $k_0=3$

to their total response time H, with values of 1, 2, and 3 at

$k_0=3$

to their total response time H, with values of 1, 2, and 3 at

![]() $k=3, 4$

, and

$k=3, 4$

, and

![]() $5$

minutes, respectively.

$5$

minutes, respectively.

Table 1 An example of the process data with three-dimensional

![]() $X = \{X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{3}\}$

, one-dimensional W, and

$X = \{X_{1}, X_{2}, X_{3}\}$

, one-dimensional W, and

![]() $k_0=3$

$k_0=3$

Following the Neyman–Rubin’s potential outcome framework (Neyman, Reference Neyman1923; Rubin, Reference Rubin1974) and its extension to causal mediation (Pearl, Reference Pearl2001; Robins & Greenland, Reference Robins and Greenland1992), we define potential (also known as counterfactual) variables. Let

![]() $T^z(k)$

denote the potential treatment use (i.e., mediator) if Z were set to

$T^z(k)$

denote the potential treatment use (i.e., mediator) if Z were set to

![]() $Z =z$

at time k. The relationship between treatment Z and mediator T can be either two-sided or one-sided. For two-sided noncompliance, we assume that

$Z =z$

at time k. The relationship between treatment Z and mediator T can be either two-sided or one-sided. For two-sided noncompliance, we assume that

![]() $T^z(k) \in \{0, 1\}, z=0, 1$

, but for one-sided noncompliance, we assume that

$T^z(k) \in \{0, 1\}, z=0, 1$

, but for one-sided noncompliance, we assume that

![]() $T^1(k) \in \{0, 1\}$

and

$T^1(k) \in \{0, 1\}$

and

![]() $T^0(k) = 0$

. Similarly, let

$T^0(k) = 0$

. Similarly, let

![]() $W^{z}$

be a subject’s potential post-treatment covariate if they received the treatment

$W^{z}$

be a subject’s potential post-treatment covariate if they received the treatment

![]() $Z=z$

. This implicitly assumes that the post-treatment covariate W is not affected by the treatment use T, but W influences T (see Figure 1 in the next section for a graphical illustration). Lastly, let

$Z=z$

. This implicitly assumes that the post-treatment covariate W is not affected by the treatment use T, but W influences T (see Figure 1 in the next section for a graphical illustration). Lastly, let

![]() $Y^{z, T^{z'}}(\mathcal {K}) = \{Y^{z, T^{z'}(k)}(k): k \in \mathcal {K} \}$

denote a subject’s potential outcome process if Z were set to z and T were set to the value it would naturally take under

$Y^{z, T^{z'}}(\mathcal {K}) = \{Y^{z, T^{z'}(k)}(k): k \in \mathcal {K} \}$

denote a subject’s potential outcome process if Z were set to z and T were set to the value it would naturally take under

![]() $Z=z'$

. For example,

$Z=z'$

. For example,

![]() $Y^{1, T^0}(\mathcal {K})$

indicates the potential outcome process if a subject received the treatment (i.e.,

$Y^{1, T^0}(\mathcal {K})$

indicates the potential outcome process if a subject received the treatment (i.e.,

![]() $Z=1$

) and their mediator T took the value it would have attained under the control condition (i.e.,

$Z=1$

) and their mediator T took the value it would have attained under the control condition (i.e.,

![]() $Z=0$

).

$Z=0$

).

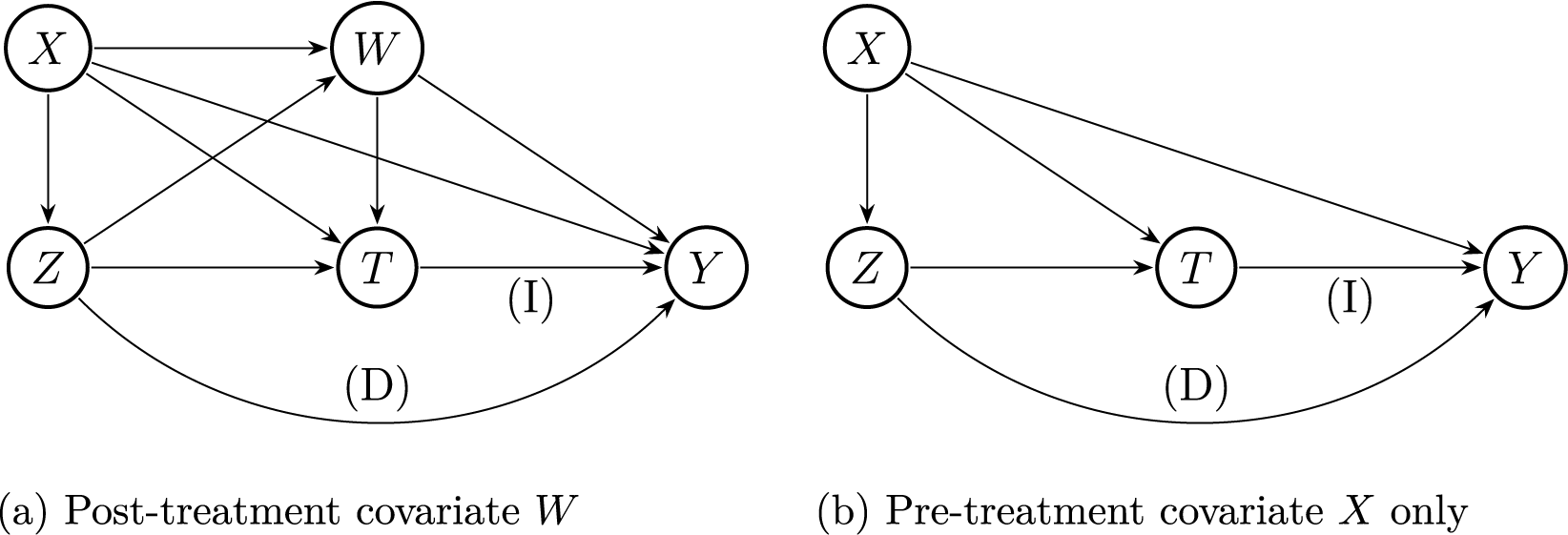

Figure 1 Graphical representations of causal relationships with a functional outcome. The arrows labeled with (D) and (I) represent the functional direct effect and functional indirect effect, respectively.

3.2 Motivating example

Testing accommodations are essential for students with disabilities and English language learners to fully demonstrate their abilities during a test. The ETA is the most frequently provided testing accommodation in many testing programs. Suppose that a researcher is interested in studying the causal mechanism and determining whether the benefit of ETA is a consequence of using ETA (i.e., indirect effect) or partially attributed to receiving ETA, not mediated via its actual use (i.e., direct effect). We also observe one-sided noncompliance in our ETA example; only students who receive ETA can decide to use it or not, but those who do not receive ETA cannot use it.

Figure 1 visualizes the assumed causal mechanisms of ETA with the receipt status (Z) and use status (T). Figure 1a describes the case where post-treatment covariates W are present, and Figure 1b describes the case only with pre-treatment covariates X. Confounding between T and Y arises due to students’ decisions about whether to use ETA, influenced by Z, X, and, if applicable, W. The total effect of Z on functional outcome Y can be decomposed into the indirect causal pathway mediated by T (i.e.,

![]() $Z \rightarrow T \rightarrow Y$

) and the direct pathway not mediated by T (i.e.,

$Z \rightarrow T \rightarrow Y$

) and the direct pathway not mediated by T (i.e.,

![]() $Z \rightarrow Y$

).

$Z \rightarrow Y$

).

4 Causal mediation with a functional outcome from process data

In this section, we extend the standard causal mediation framework (e.g., Pearl, Reference Pearl2001) to the functional outcome context, particularly using process data in digital-based assessments. We use the ETA in digital-based assessments as an illustration of the proposed framework. In this setting, we observe one-sided noncompliance between treatment Z and mediator T (i.e.,

![]() $T^1(k) \in \{0, 1\}$

and

$T^1(k) \in \{0, 1\}$

and

![]() $T^0(k) = 0$

). Additionally, to clearly interpret the causal estimands below, we make the following assumption.

$T^0(k) = 0$

). Additionally, to clearly interpret the causal estimands below, we make the following assumption.

Assumption A1 (Stabilized decision).

-

There exists a constant

$k_0$

such that

$k_0$

such that

$T^z(k)$

is constant for

$T^z(k)$

is constant for

$k_0 \leq k$

, i.e.,

$k_0 \leq k$

, i.e.,

$T^z(k) = T^z(k')$

if

$T^z(k) = T^z(k')$

if

$k_0 \leq k,k'$

. Therefore, we simply denote

$k_0 \leq k,k'$

. Therefore, we simply denote

$T^z=T^z(k)$

for

$T^z=T^z(k)$

for

$k_0 \leq k$

.

$k_0 \leq k$

.

Assumption A1 states that a student’s decision to use the offered ETA becomes constant at or after the minimum valid time

![]() $k_0$

. For example, if the minimum valid time is 10 minutes after the test starts, it is assumed that students make their decisions about ETA use by then (as in Figure 1a). Or, if the minimum valid time is the test start time, it indicates that students decide whether to use the offered ETA at or before the start of the test (see Figure 1b). This minimum time should be determined based on domain knowledge. Indeed, we motivate this assumption based on our NAEP data and prior studies (e.g., Mollenkopf, Reference Mollenkopf1960; Ogut et al., Reference Ogut, Circi, Huo, Hicks and Yin2025; Weinstein & Roediger, Reference Weinstein and Roediger2012), and we provide further discussion of its plausibility in our setting in Section 7.

$k_0$

. For example, if the minimum valid time is 10 minutes after the test starts, it is assumed that students make their decisions about ETA use by then (as in Figure 1a). Or, if the minimum valid time is the test start time, it indicates that students decide whether to use the offered ETA at or before the start of the test (see Figure 1b). This minimum time should be determined based on domain knowledge. Indeed, we motivate this assumption based on our NAEP data and prior studies (e.g., Mollenkopf, Reference Mollenkopf1960; Ogut et al., Reference Ogut, Circi, Huo, Hicks and Yin2025; Weinstein & Roediger, Reference Weinstein and Roediger2012), and we provide further discussion of its plausibility in our setting in Section 7.

Under one-sided noncompliance and stabilized decision, we define the causal estimands of interest and discuss identification and estimation strategies for the target causal estimands.

4.1 Estimands

In causal mediation analysis, we decompose the functional total effect (FTE), also referred to as the FATE, into the functional natural direct effect (FNDE) and functional natural indirect effect (FNIE), across the functional domain

![]() $\mathcal {K}$

. These effects at time k, for

$\mathcal {K}$

. These effects at time k, for

![]() $k \in \mathcal {K}$

, are formally defined as

$k \in \mathcal {K}$

, are formally defined as

$$ \begin{align*} \tau_{\text{TE}}(k) & = E \big\{ Y^{1,T^1} (k) - Y^{0,T^0} (k) \big\} \\ & = \underbrace{ E \big\{ Y^{1,T^1 }(k) - Y^{1,T^0 }(k) \big\} }_{=\text{ functional natural indirect effect}} + \underbrace{ E \big\{ Y^{1,T^0 }(k) - Y^{0,T^0 }(k)\big\} }_{= \text{ functional natural direct effect}} \\ & = \tau_{\text{NIE}}(k) + \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \tau_{\text{TE}}(k) & = E \big\{ Y^{1,T^1} (k) - Y^{0,T^0} (k) \big\} \\ & = \underbrace{ E \big\{ Y^{1,T^1 }(k) - Y^{1,T^0 }(k) \big\} }_{=\text{ functional natural indirect effect}} + \underbrace{ E \big\{ Y^{1,T^0 }(k) - Y^{0,T^0 }(k)\big\} }_{= \text{ functional natural direct effect}} \\ & = \tau_{\text{NIE}}(k) + \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k). \end{align*} $$

In words,

![]() $\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k)$

measures the expected increase in Y at time k when the treatment changes from

$\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k)$

measures the expected increase in Y at time k when the treatment changes from

![]() $Z=0$

to

$Z=0$

to

![]() $Z=1$

while holding the mediator constant at the value it would have attained under

$Z=1$

while holding the mediator constant at the value it would have attained under

![]() $Z=0$

. On the other hand,

$Z=0$

. On the other hand,

![]() $\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k)$

measures the expected increase in Y at time k when the mediator changes to the value it would have attained under

$\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k)$

measures the expected increase in Y at time k when the mediator changes to the value it would have attained under

![]() $Z=0$

while holding the treatment constant at

$Z=0$

while holding the treatment constant at

![]() $Z=1$

.Footnote

1

These effects can be written as follows under one-sided noncompliance:

$Z=1$

.Footnote

1

These effects can be written as follows under one-sided noncompliance:

$$ \begin{align} \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k) &= E \big\{Y^{1, 0}(k) - Y^{0, 0}(k)\big\} ,\\\tau_{\text{NIE}}(k) &= E \big\{Y^{1, T^1}(k) - Y^{1, 0}(k)\big\}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k) &= E \big\{Y^{1, 0}(k) - Y^{0, 0}(k)\big\} ,\\\tau_{\text{NIE}}(k) &= E \big\{Y^{1, T^1}(k) - Y^{1, 0}(k)\big\}. \end{align} $$

For our ETA example,

![]() $\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k)$

means the direct effect of receiving ETA at time k, not mediated by using it, and

$\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k)$

means the direct effect of receiving ETA at time k, not mediated by using it, and

![]() $\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k)$

means the indirect effect of receiving ETA through its natural use by a student at time k.

$\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k)$

means the indirect effect of receiving ETA through its natural use by a student at time k.

Moreover, we are interested in the subgroup effects for the FNDE and FNIE, denoted as S-FNDE and S-FNIE. The S-FNDE and S-FNIE measure the FNDE and FNIE among a subgroup of individuals determined by a subset of pre-treatment covariates V, respectively. These subgroup effects examine effect heterogeneity, i.e., how the effects vary across different subgroups. The S-FNDE and S-FNIE are defined as

For our ETA example, V can be selected as students’ disability status, where

![]() $V = 1$

indicates students with disabilities and

$V = 1$

indicates students with disabilities and

![]() $V = 0$

indicates those without disabilities. Then,

$V = 0$

indicates those without disabilities. Then,

![]() $\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k |V= 1)$

is the direct effect of receiving the ETA at time k among students with disabilities, while

$\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k |V= 1)$

is the direct effect of receiving the ETA at time k among students with disabilities, while

![]() $\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k |V=1)$

is the indirect effect of receiving the ETA via its natural use at time k among students with disabilities. Similarly,

$\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k |V=1)$

is the indirect effect of receiving the ETA via its natural use at time k among students with disabilities. Similarly,

![]() $\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k|V=0)$

and

$\tau _{\text {NDE}}(k|V=0)$

and

![]() $\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k |V=0)$

are the corresponding direct and indirect effects, respectively, among students without disabilities.

$\tau _{\text {NIE}}(k |V=0)$

are the corresponding direct and indirect effects, respectively, among students without disabilities.

4.2 Identification

The potential variable

![]() $T^z(k)$

(which equals

$T^z(k)$

(which equals

![]() $T^z$

under Assumption A1), i.e., potential ETA use, is inherently derived from a potential functional mediator at time k for subjects with

$T^z$

under Assumption A1), i.e., potential ETA use, is inherently derived from a potential functional mediator at time k for subjects with

![]() $Z=z$

, denoted as

$Z=z$

, denoted as

![]() $H^z(k)$

. Here,

$H^z(k)$

. Here,

![]() $H^z(k)$

represents the amount of time a subject would intend to spend on the test at time k if they received

$H^z(k)$

represents the amount of time a subject would intend to spend on the test at time k if they received

![]() $Z=z$

. This variable determines the potential intended ETA use variable at time k, specifically,

$Z=z$

. This variable determines the potential intended ETA use variable at time k, specifically, ![]() , where c is the standard testing time. Although

, where c is the standard testing time. Although

![]() $H^z(k)$

is only partially observable through H, we introduce the variable to identify the FNDE and FNIE within a functional framework (see Appendix S1 of the Supplementary Material for details on the identification and use of

$H^z(k)$

is only partially observable through H, we introduce the variable to identify the FNDE and FNIE within a functional framework (see Appendix S1 of the Supplementary Material for details on the identification and use of

![]() $H^z(k)$

). In this article, we focus on the setting of Figure 1a with post-treatment covariates W, due to its added complexities compared to the simpler case of Figure 1b with

$H^z(k)$

). In this article, we focus on the setting of Figure 1a with post-treatment covariates W, due to its added complexities compared to the simpler case of Figure 1b with

![]() $W=\{ \}$

. In the presence of post-treatment covariates, we make the following assumptions to identify the FNDE and FNIE, as well as their subgroup effects (S-FNDE and S-FNIE).

$W=\{ \}$

. In the presence of post-treatment covariates, we make the following assumptions to identify the FNDE and FNIE, as well as their subgroup effects (S-FNDE and S-FNIE).

Assumption A2 (Consistency).

-

(i) If

$Z=z$

and

$Z=z$

and

$k_0 \leq k$

, then

$k_0 \leq k$

, then

$T = T^z(k)$

and

$T = T^z(k)$

and  .

. -

(ii) If

$Z=z$

and

$Z=z$

and

$T=t$

and

$T=t$

and

$k \leq H$

, then

$k \leq H$

, then

$Y(k)=Y^{z,t}(k)$

.

$Y(k)=Y^{z,t}(k)$

. -

(iii) If

$Z=z$

, then

$Z=z$

, then

$W=W^{z}$

.

$W=W^{z}$

.

Assumption A3 (Unconfoundedness).

For all

![]() $z \in \{0,1\}$

:

$z \in \{0,1\}$

:

-

(i)

;

; -

(ii)

Assumption A4 (Positivity).

-

(i)

$P_{Z | X}(z \mid x)> 0$

for all

$P_{Z | X}(z \mid x)> 0$

for all

$z,x$

.

$z,x$

. -

(ii)

$P_{H W | Z,X}(h, w \mid z=1,x)> 0$

for all

$P_{H W | Z,X}(h, w \mid z=1,x)> 0$

for all

$x,w$

and

$x,w$

and

$h \in {\mathcal {K}}$

.

$h \in {\mathcal {K}}$

. -

(iii)

$P_{H W | Z,X}(h, w \mid z=0,x)> 0$

for all

$P_{H W | Z,X}(h, w \mid z=0,x)> 0$

for all

$x,w$

and

$x,w$

and

$h\in [k_0,c]$

.

$h\in [k_0,c]$

.

Assumptions A2–A4 extend the standard identifying assumptions for mediation analysis (Pearl, Reference Pearl2001) to the context of functional outcomes with post-treatment covariates in digital assessments. At a high level, Assumption A2 (Consistency) links observed variables to potential outcomes and mediators; Assumption A3 (Unconfoundedness) states that there are no unmeasured confounders in treatment and mediator assignments, and Assumption A4 (Positivity) ensures sufficient overlap in the distributions of treatment, mediator, and post-treatment covariates between treated units and control units. Note that when post-treatment covariates are absent, one can simply omit or revise parts of the assumptions that include W and

![]() $W^z$

. In Appendix S2 of the Supplementary Material, we provide a set of identifying assumptions for this simplified setting.

$W^z$

. In Appendix S2 of the Supplementary Material, we provide a set of identifying assumptions for this simplified setting.

More specifically, Assumption A2 states that for A2-(i), a subject’s potential ETA use under a given treatment at time k, i.e.,

![]() $T^z(k)$

, is identical to their observed mediator for that same treatment T; we remark that

$T^z(k)$

, is identical to their observed mediator for that same treatment T; we remark that

![]() $T=T^Z=T^Z(k)$

for

$T=T^Z=T^Z(k)$

for

![]() $k_0 \leq k$

under Assumptions A1 and A2. It also assumes that the indicator of whether

$k_0 \leq k$

under Assumptions A1 and A2. It also assumes that the indicator of whether

![]() $H^z(k)$

(i.e., the potential response time at k) exceeds or equals time k is identical to whether H (i.e., the observed total response time) is larger than or equal to k.Footnote

2

Assumption A2-(ii) states that when time k is less than or equal to H (implying that a subject’s data is collected at time k), their potential outcome

$H^z(k)$

(i.e., the potential response time at k) exceeds or equals time k is identical to whether H (i.e., the observed total response time) is larger than or equal to k.Footnote

2

Assumption A2-(ii) states that when time k is less than or equal to H (implying that a subject’s data is collected at time k), their potential outcome

![]() $Y^{z, t}(k)$

is the same as the observed outcome

$Y^{z, t}(k)$

is the same as the observed outcome

![]() $Y(k)$

if their treatment and mediator were set to

$Y(k)$

if their treatment and mediator were set to

![]() $Z=z$

and

$Z=z$

and

![]() $T=t$

. Likewise, Assumption A2-(iii) states that their potential post-treatment covariate

$T=t$

. Likewise, Assumption A2-(iii) states that their potential post-treatment covariate

![]() $W^{z}$

under

$W^{z}$

under

![]() $Z=z$

is the same as the observed post-treatment covariate W.

$Z=z$

is the same as the observed post-treatment covariate W.

Assumption A3-(i) states that within every value of the pre-treatment covariates X, the treatment Z is randomly assigned to subjects, and thus, independent of the potential outcome process

![]() $Y^{z, t}(\mathcal {K})$

, the potential functional mediator process

$Y^{z, t}(\mathcal {K})$

, the potential functional mediator process

![]() $H^{z}(\mathcal {K})$

, and the potential post-treatment covariates

$H^{z}(\mathcal {K})$

, and the potential post-treatment covariates

![]() $W^{z}$

. In our ETA context, suppose two students have the same pre-treatment covariates, including disability status, English-language learner status, prior math level, and perseverance level. Assumption A3-(i) means that, given these covariates, the ETA receipt status is as good as randomly assigned. Next, Assumption A3-(ii) states that conditional on treatment and the pre- and post-treatment covariates,

$W^{z}$

. In our ETA context, suppose two students have the same pre-treatment covariates, including disability status, English-language learner status, prior math level, and perseverance level. Assumption A3-(i) means that, given these covariates, the ETA receipt status is as good as randomly assigned. Next, Assumption A3-(ii) states that conditional on treatment and the pre- and post-treatment covariates,

![]() $H^{z}(\mathcal {K})$

is independent of

$H^{z}(\mathcal {K})$

is independent of

![]() $Y^{z, t}(\mathcal {K})$

. In particular, it is important to adjust for the post-treatment covariates as well to ensure the independence between

$Y^{z, t}(\mathcal {K})$

. In particular, it is important to adjust for the post-treatment covariates as well to ensure the independence between

![]() $H^{z}(\mathcal {K})$

and

$H^{z}(\mathcal {K})$

and

![]() $Y^{z, t}(\mathcal {K})$

. To illustrate, consider two students who receive the same treatment (say,

$Y^{z, t}(\mathcal {K})$

. To illustrate, consider two students who receive the same treatment (say,

![]() $Z=1$

) and share identical pre-treatment covariates (e.g., disability status and prior math level) and post-treatment covariates (e.g., items accessed up to

$Z=1$

) and share identical pre-treatment covariates (e.g., disability status and prior math level) and post-treatment covariates (e.g., items accessed up to

![]() $k_0$

). Assumption A3-(ii) implies that given this information, their potential use of ETA (as determined by their potential total response time) is independent of their potential evolving test scores, and thus, the assignment of the mediator (i.e., the ETA use) is as good as random.

$k_0$

). Assumption A3-(ii) implies that given this information, their potential use of ETA (as determined by their potential total response time) is independent of their potential evolving test scores, and thus, the assignment of the mediator (i.e., the ETA use) is as good as random.

Assumption A4 states that (i) for every value of the covariates, the probability of receiving treatment (i.e., the propensity score) is between 0 and 1, (ii) for every value of the pre- and post-treatment covariates, the density distribution of the observed response time H over

![]() $\mathcal {K}$

is non-zero among subjects with

$\mathcal {K}$

is non-zero among subjects with

![]() $Z=1$

, and (iii) for every value of the pre- and post-treatment covariates, the density distribution of H over

$Z=1$

, and (iii) for every value of the pre- and post-treatment covariates, the density distribution of H over

![]() $[k_0,c]$

is non-zero among subjects with

$[k_0,c]$

is non-zero among subjects with

![]() $Z=0$

. In our ETA example, Assumption A4-(i) means that each eligible student has a real chance of receiving ETA given their pre-treatment covariates, and A4-(ii) and A4-(iii) mean that for each combination of pre-treatment covariates and ETA receipt status, there are students who exhibit all possible values of response time and early-test covariates.

$Z=0$

. In our ETA example, Assumption A4-(i) means that each eligible student has a real chance of receiving ETA given their pre-treatment covariates, and A4-(ii) and A4-(iii) mean that for each combination of pre-treatment covariates and ETA receipt status, there are students who exhibit all possible values of response time and early-test covariates.

In addition to Assumptions A1–A4, we assume that

![]() $Y^{z,t=0}(k)=Y^{z,t=0}(c)$

for

$Y^{z,t=0}(k)=Y^{z,t=0}(c)$

for

![]() $k\geq c $

to reflect that a student’s outcome does not change over the extended time period

$k\geq c $

to reflect that a student’s outcome does not change over the extended time period

![]() $[c,k_m]$

if they do not use the ETA. In Appendix S1 of the Supplementary Material, we provide formal proofs of identification for the FNDE and FNIE based on these assumptions, building on identification results of Pearl (Reference Pearl2001) and Robins (Reference Robins1986). Briefly, the identifying formulas for the FNDE and FNIE depend on the outcome model and the model for the post-treatment variables (i.e., the mediator and the post-treatment confounder), which are defined as

$[c,k_m]$

if they do not use the ETA. In Appendix S1 of the Supplementary Material, we provide formal proofs of identification for the FNDE and FNIE based on these assumptions, building on identification results of Pearl (Reference Pearl2001) and Robins (Reference Robins1986). Briefly, the identifying formulas for the FNDE and FNIE depend on the outcome model and the model for the post-treatment variables (i.e., the mediator and the post-treatment confounder), which are defined as

where

![]() $(z,t) \in \{(0,0),(1,0),(1,1)\}$

. Note that

$(z,t) \in \{(0,0),(1,0),(1,1)\}$

. Note that

![]() $(z,t)=(0,1)$

is not considered due to one-sided noncompliance. In Appendix S3 of the Supplementary Material, we also outline the identifying assumptions for the general case with a binary static mediator so that readers can adapt them in their specific contexts.

$(z,t)=(0,1)$

is not considered due to one-sided noncompliance. In Appendix S3 of the Supplementary Material, we also outline the identifying assumptions for the general case with a binary static mediator so that readers can adapt them in their specific contexts.

4.3 Estimation

To estimate the FNDE and FNIE, as well as their subgroup effects, we use function-on-scalar regression from the functional data analysis literature (Crainiceanu et al., Reference Crainiceanu, Goldsmith, Leroux and Cui2024). Let

![]() $S=\{ W,X\} \in \mathbb {R}^{p+q}$

. We estimate the outcome model (5), i.e.,

$S=\{ W,X\} \in \mathbb {R}^{p+q}$

. We estimate the outcome model (5), i.e.,

![]() $m_{zt}(k,w,x)$

, using a GAM in the following additive form:

$m_{zt}(k,w,x)$

, using a GAM in the following additive form:

$$ \begin{align} m_{zt}(k, w, x) &= m_{zt}(k, s) = \beta_{0zt}(k) + \sum_{r=1}^{R} f_{rzt}(k,s_r). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} m_{zt}(k, w, x) &= m_{zt}(k, s) = \beta_{0zt}(k) + \sum_{r=1}^{R} f_{rzt}(k,s_r). \end{align} $$

In this model,

![]() $\beta _{0zt}(k)$

represents the functional intercept, while

$\beta _{0zt}(k)$

represents the functional intercept, while

![]() $f_{rzt}(k, s_r)$

is its r-th smooth function that depends on a subset of covariates

$f_{rzt}(k, s_r)$

is its r-th smooth function that depends on a subset of covariates

![]() $S_r \subseteq S$

(

$S_r \subseteq S$

(

![]() $r=1, \ldots , R$

). These smooth functions can vary across covariate domains and the functional domain and may include time-invariant linear terms, linear interaction terms, as well as one-dimensional and multi-dimensional smooth terms.

$r=1, \ldots , R$

). These smooth functions can vary across covariate domains and the functional domain and may include time-invariant linear terms, linear interaction terms, as well as one-dimensional and multi-dimensional smooth terms.

As an example, consider the following instance of GAMs for the outcome model:

$$ \begin{align} m_{zt}(k, s) &= \beta_{0zt}(k) + \sum_{j=1}^{p+q} f_{jzt}(s_j) + \sum_{j=1}^{p+q}f_{jzt}(k, s_j). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} m_{zt}(k, s) &= \beta_{0zt}(k) + \sum_{j=1}^{p+q} f_{jzt}(s_j) + \sum_{j=1}^{p+q}f_{jzt}(k, s_j). \end{align} $$

Here,

![]() $f_{jzt}(s_j)$

is a time-invariant, univariate smooth function, and

$f_{jzt}(s_j)$

is a time-invariant, univariate smooth function, and

![]() $f_{jzt}(k,s_{j})$

is a time-varying smooth function. Both are defined for subjects with

$f_{jzt}(k,s_{j})$

is a time-varying smooth function. Both are defined for subjects with

![]() $Z=z$

and

$Z=z$

and

![]() $T=t$

and for each covariate

$T=t$

and for each covariate

![]() $S_j$

(

$S_j$

(

![]() $j=1, \ldots , p+q$

).

$j=1, \ldots , p+q$

).

These smooth functions are parameterized using spline basis expansions. Specifically, for the smooth functions in the outcome model (8), we may take

$$ \begin{align} \beta_{0zt}(k) &= \sum_{l=1}^{L_{0jzt}}\beta_{0zt,l}\phi_{zt,l}(k) , \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \beta_{0zt}(k) &= \sum_{l=1}^{L_{0jzt}}\beta_{0zt,l}\phi_{zt,l}(k) , \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{jzt}(s_{j}) &= \sum_{l=1}^{L_{1jzt}} \beta_{1jzt,l} \phi_{zt,l}(s_j), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{jzt}(s_{j}) &= \sum_{l=1}^{L_{1jzt}} \beta_{1jzt,l} \phi_{zt,l}(s_j), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{jzt}(k,s_j) &= \sum_{l=1}^{L_{2jzt}} \beta_{2jzt,l} \phi_{zt,l}(k,s_j), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f_{jzt}(k,s_j) &= \sum_{l=1}^{L_{2jzt}} \beta_{2jzt,l} \phi_{zt,l}(k,s_j), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\{\phi _{zt,l}(\cdot ) \}$

are basis functions, and

$\{\phi _{zt,l}(\cdot ) \}$

are basis functions, and

![]() $\{\beta _{(\cdot )jzt,l}\}$

are the corresponding coefficients. Various classes of basis functions can be used, including B-splines, natural cubic splines, and thin plate splines. In this study, we use thin plate splines. For an overview of thin plate splines, see Section 5.5.1 of Wood (Reference Wood2017) and Wood (Reference Wood2003). We select the smoothing parameter, which controls the trade-off between smoothness and model fit, using the generalized cross-validation (GCV) method. Additionally, we estimate the post-treatment variable model (6) using a similar approach, but with a link function (e.g., logit). More details on its estimation are provided in Appendix S4 of the Supplementary Material.

$\{\beta _{(\cdot )jzt,l}\}$

are the corresponding coefficients. Various classes of basis functions can be used, including B-splines, natural cubic splines, and thin plate splines. In this study, we use thin plate splines. For an overview of thin plate splines, see Section 5.5.1 of Wood (Reference Wood2017) and Wood (Reference Wood2003). We select the smoothing parameter, which controls the trade-off between smoothness and model fit, using the generalized cross-validation (GCV) method. Additionally, we estimate the post-treatment variable model (6) using a similar approach, but with a link function (e.g., logit). More details on its estimation are provided in Appendix S4 of the Supplementary Material.

Let us denote estimators of

![]() $m_{zt}$

and

$m_{zt}$

and

![]() $g_{zt}$

in (5) and (6) as

$g_{zt}$

in (5) and (6) as

![]() $\hat {m}_{zt}$

and

$\hat {m}_{zt}$

and

![]() $\hat {g}_{zt}$

, respectively. Using these estimators, we construct estimators for the FNDE and FNIE, and their total effect, FTE, as

$\hat {g}_{zt}$

, respectively. Using these estimators, we construct estimators for the FNDE and FNIE, and their total effect, FTE, as

where

![]() $\hat {g}_{z\cdot } (w,x) = \hat {g}_{z0}(w,x)+\hat {g}_{z1}(w,x)$

, which is an estimator for

$\hat {g}_{z\cdot } (w,x) = \hat {g}_{z0}(w,x)+\hat {g}_{z1}(w,x)$

, which is an estimator for

![]() $P( W=w | Z=z,X=x )$

. If W is continuous, the summation over w can be replaced with an integral. Likewise, the estimators for the subgroup effects of S-FNDE, S-FNIE, and S-FTE are as follows:

$P( W=w | Z=z,X=x )$

. If W is continuous, the summation over w can be replaced with an integral. Likewise, the estimators for the subgroup effects of S-FNDE, S-FNIE, and S-FTE are as follows:

For inference, we use nonparametric cluster bootstrapping to obtain standard errors or confidence intervals. Specifically, we resample individuals, rather than time points, to account for unit-specific serial dependence. For each sample, we apply the above GAM estimators, i.e.,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE}}(k)$

,

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE}}(k)$

,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE}}(k)$

,

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE}}(k)$

,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE}}(k)$

,

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE}}(k)$

,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE}}(k | v)$

,

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE}}(k | v)$

,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE}}(k | v)$

, and

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE}}(k | v)$

, and

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE}}(k | v)$

, and then compute standard errors or pointwise confidence intervals from the bootstrap distribution (see Appendix S5 of the Supplementary Material for details).

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE}}(k | v)$

, and then compute standard errors or pointwise confidence intervals from the bootstrap distribution (see Appendix S5 of the Supplementary Material for details).

5 Simulation study

5.1 Designs and evaluation

We conducted a simulation study to investigate the finite-sample performance of the proposed estimators. We varied the number of observations n from

![]() $\{ 100, 200, 500, 1,000 \}$

. We set the standard testing time to

$\{ 100, 200, 500, 1,000 \}$

. We set the standard testing time to

![]() $c=20$

, the maximum extended testing time to

$c=20$

, the maximum extended testing time to

![]() $k_{m}=40$

, and the minimum value of the functional domain to

$k_{m}=40$

, and the minimum value of the functional domain to

![]() $k_0=6$

. For each subject i, we generated two binary covariates

$k_0=6$

. For each subject i, we generated two binary covariates

![]() $X_{i1}$

and

$X_{i1}$

and

![]() $X_{i2}$

independently from

$X_{i2}$

independently from

![]() $\text {Ber}(0.5)$

, and the ETA receipt status

$\text {Ber}(0.5)$

, and the ETA receipt status

![]() $Z_{i}$

from

$Z_{i}$

from

![]() $\text {Ber}(\text {expit}(0.2(X_{i1}+X_{i2}-1))),$

where

$\text {Ber}(\text {expit}(0.2(X_{i1}+X_{i2}-1))),$

where

![]() $\text {expit}(v)=\exp (v)/\{1+\exp (v)\}$

.

$\text {expit}(v)=\exp (v)/\{1+\exp (v)\}$

.

For the outcome, we considered the following two data-generating processes: the linear outcome model and the cubic outcome model. The linear outcome model uses

The cubic outcome model uses, for ![]() and

and

![]() $ \nu _k = -10 \{ -|(k-5)/50-1|^3 +1\}$

,

$ \nu _k = -10 \{ -|(k-5)/50-1|^3 +1\}$

,

The post-treatment covariate at time

![]() $k_0=6$

was selected as

$k_0=6$

was selected as ![]() , where

, where

![]() $C=8.25$

for the linear outcome model and

$C=8.25$

for the linear outcome model and

![]() $C=6.88$

for the cubic outcome model. Thus,

$C=6.88$

for the cubic outcome model. Thus,

![]() $W_i^z$

serves as an indicator of whether a student achieved a high test score (or accessed more items) within the first 5 minutes.

$W_i^z$

serves as an indicator of whether a student achieved a high test score (or accessed more items) within the first 5 minutes.

We also generated

![]() $H_i^z(k_0)$

, i.e., the amount of time that subject i would intend to spend on the test for

$H_i^z(k_0)$

, i.e., the amount of time that subject i would intend to spend on the test for

![]() $Z_i=z$

, conditional on the pre-treatment covariates

$Z_i=z$

, conditional on the pre-treatment covariates

![]() $(X_{i1}, X_{i2})$

and the post-treatment covariates

$(X_{i1}, X_{i2})$

and the post-treatment covariates

![]() $W_{i}^z$

, as follows for

$W_{i}^z$

, as follows for

![]() $z=0,1$

:

$z=0,1$

:

$$ \begin{align*} & P\{ H_i^{z}(k_0) = (10,15,20) \cdot (z+1) \} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} (0.2,0.2,0.6) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=0 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=0 \\ (0.25,0.25,0.5) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=0 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=1 \\ (0.3,0.3,0.4) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=1 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=0 \\ (1/3,1/3,1/3) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=1 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=1 \\ (1/3,1/3,1/3) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=2. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} & P\{ H_i^{z}(k_0) = (10,15,20) \cdot (z+1) \} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} (0.2,0.2,0.6) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=0 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=0 \\ (0.25,0.25,0.5) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=0 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=1 \\ (0.3,0.3,0.4) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=1 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=0 \\ (1/3,1/3,1/3) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=1 \text{ and } W_i^{0}=1 \\ (1/3,1/3,1/3) & \text{ if } X_{i1}+X_{i2}=2. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

Roughly speaking, students with higher values of the covariate sum

![]() $X_{i1}+X_{i2}$

and

$X_{i1}+X_{i2}$

and

![]() $W_i^{z}=1$

(i.e., higher early-stage test scores) will likely have shorter actual response times. Given

$W_i^{z}=1$

(i.e., higher early-stage test scores) will likely have shorter actual response times. Given

![]() $H_i^{z}(k_0)$

, we defined

$H_i^{z}(k_0)$

, we defined

![]() $H_{i}^{z}(k) = H_i^{z}(k_0)$

for all

$H_{i}^{z}(k) = H_i^{z}(k_0)$

for all

![]() $k \in \mathcal {K}$

. The ETA use variable at time k was determined by

$k \in \mathcal {K}$

. The ETA use variable at time k was determined by ![]() . Note that

. Note that

![]() $T^{0}(k) = 0$

due to one-sided noncompliance in ETA settings. The observed data for subject i were defined by

$T^{0}(k) = 0$

due to one-sided noncompliance in ETA settings. The observed data for subject i were defined by

![]() $\{X_{i1},X_{i2},Z_i, W_i, H_i, T_i, Y_i(k) \}$

for

$\{X_{i1},X_{i2},Z_i, W_i, H_i, T_i, Y_i(k) \}$

for

![]() $k \in [6, H_i]$

, where

$k \in [6, H_i]$

, where

![]() $\{ H_i, T_i, Y_i(k) \}$

were obtained from

$\{ H_i, T_i, Y_i(k) \}$

were obtained from

![]() $H_i=H_i^{Z_i}(k)$

,

$H_i=H_i^{Z_i}(k)$

,

![]() $T_i=T_i^{Z_i}(k)$

, and

$T_i=T_i^{Z_i}(k)$

, and

![]() $Y_i(k) = Y_i^{Z_i,T_i}(k)$

.

$Y_i(k) = Y_i^{Z_i,T_i}(k)$

.

Using the simulated data, we estimated the FNDE, FNIE, and FTE using the proposed GAM estimators in Section 4.3. We denote these estimators as

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE},GAM}$

,

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE},GAM}$

,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE},GAM}$

, and

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE},GAM}$

, and

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE},GAM}$

. For implementation, we used the function gam from R package mgcv (Wood, Reference Wood2023) to fit the GAMs for both the outcome and post-treatment variable models. Details on the implementation are provided in Appendix S6 of the Supplementary Material. As comparison estimators, we considered two parametric regression-based estimators for the FNDE, FNIE, and FTE, fitting the smooth curves over time through linear and cubic terms. We refer to them as linear estimators (denoted as

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE},GAM}$

. For implementation, we used the function gam from R package mgcv (Wood, Reference Wood2023) to fit the GAMs for both the outcome and post-treatment variable models. Details on the implementation are provided in Appendix S6 of the Supplementary Material. As comparison estimators, we considered two parametric regression-based estimators for the FNDE, FNIE, and FTE, fitting the smooth curves over time through linear and cubic terms. We refer to them as linear estimators (denoted as

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE},Lin}$

,

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE},Lin}$

,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE},Lin}$

, and

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE},Lin}$

, and

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE},Lin}$

) and cubic estimators (denoted as

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE},Lin}$

) and cubic estimators (denoted as

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE},Cub}$

,

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NDE},Cub}$

,

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE},Cub}$

, and

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {NIE},Cub}$

, and

![]() $\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE},Cub}$

), respectively (see Appendix S6 of the Supplementary Material for a detailed specification of the coefficients in model (9)). We repeated the simulation 1,000 times.

$\hat {\tau }_{\text {TE},Cub}$

), respectively (see Appendix S6 of the Supplementary Material for a detailed specification of the coefficients in model (9)). We repeated the simulation 1,000 times.

Based on 1,000 repetitions, we calculated the bias and mean squared error (MSE) of the three estimators, defined as follows for the FNDE:

$$ \begin{align*} \text{Bias}_{\text{NDE}, \star} &= \frac{1}{1000} \sum_{j=1}^{1000} \frac{1}{35} \sum_{k=6}^{40} \big\{ \hat{\tau}_{\text{NDE}, \star}^{(j)}(k) - \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k) \big\} \\ \text{MSE}_{\text{NDE}, \star} &= \frac{1}{1000} \sum_{j=1}^{1000} \frac{1}{35} \sum_{k=6}^{40} \big\{ \hat{\tau}_{\text{NDE}, \star}^{(j)}(k) - \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k) \big\}^2, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \text{Bias}_{\text{NDE}, \star} &= \frac{1}{1000} \sum_{j=1}^{1000} \frac{1}{35} \sum_{k=6}^{40} \big\{ \hat{\tau}_{\text{NDE}, \star}^{(j)}(k) - \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k) \big\} \\ \text{MSE}_{\text{NDE}, \star} &= \frac{1}{1000} \sum_{j=1}^{1000} \frac{1}{35} \sum_{k=6}^{40} \big\{ \hat{\tau}_{\text{NDE}, \star}^{(j)}(k) - \tau_{\text{NDE}}(k) \big\}^2, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\star \in \{ GAM, Lin, Cub\}$

denotes the estimator type and the superscript

$\star \in \{ GAM, Lin, Cub\}$

denotes the estimator type and the superscript

![]() $^{(j)}$

represents the simulation repetition index. The bias and MSE for the FNIE and FTE are similarly defined. Smaller bias and MSE values indicate better performance of an estimator.

$^{(j)}$

represents the simulation repetition index. The bias and MSE for the FNIE and FTE are similarly defined. Smaller bias and MSE values indicate better performance of an estimator.

We also evaluated the performance of the inferential procedure based on the bootstrap. For each k, we calculated the empirical coverage rates of 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the FNDE based on the proposed GAM method (denoted as

![]() $\text {CI}_{\text {NDE},GAM}(k)$

) as follows:

$\text {CI}_{\text {NDE},GAM}(k)$

) as follows:

The coverage rates of the empirical coverage rates of 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for the FNIE and FTE are similarly defined. The R code for the simulations is available at https://github.com/qkrcks0218/FDA.

5.2 Simulation results

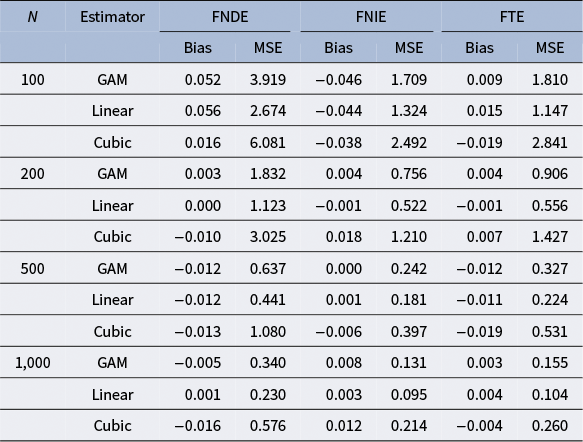

Table 2 summarizes the simulation results under the linear outcome model. In this design, the linear and cubic estimators are correctly specified due to the linear form of the outcome model. However, the cubic estimator includes redundant regressors of higher-order time components. As discussed earlier, the GAM estimator is expected to capture the linear form due to its flexibility and adaptivity. This is confirmed by our finding that all three estimators exhibit negligible bias across all three estimands and sample sizes. In terms of MSE, the linear estimator achieves the smallest value, as it is the correctly specified and parsimonious model. In this design, the linear estimator serves as an oracle estimator. The cubic estimator is less efficient than the linear estimator due to the inclusion of redundant terms. The GAM estimator performs between the linear and cubic estimators, and it consistently shows a smaller MSE than the cubic estimator across all three estimands and sample sizes.

Table 2 Simulation results under the linear outcome model

Note: FNDE = functional natural direct effect; FNIE = functional natural indirect effect; FTE = functional total effect; GAM = generalized additive model; Linear = parametric regression with a linear term; Cubic = parametric regression with linear, quadratic, and cubic terms; MSE = mean squared error.

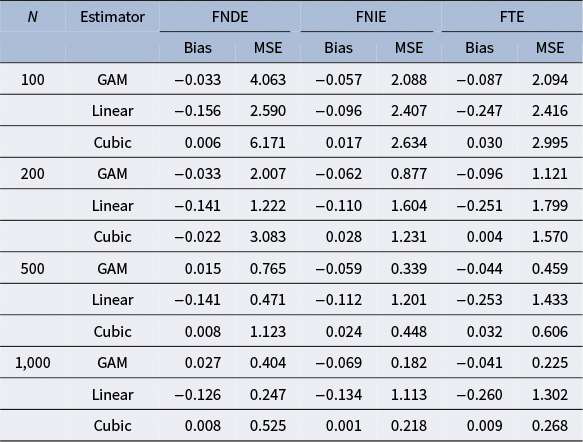

Next, we summarize simulation results under the cubic outcome model in Table 3. In this design, the cubic estimator is still correctly specified, but the linear estimator is mis-specified. Despite the change in the outcome model form, the GAM estimator is expected to capture the true model with no concerns about mis-specification. In line with this expectation, both the GAM and cubic estimators exhibit negligible bias, and the GAM estimator generally shows slightly larger absolute bias. In contrast, the linear estimator shows substantial bias for all three estimands and sample sizes. Regarding MSE, the GAM estimator generally achieves the smallest value, and it outperforms the cubic estimator. Although the GAM estimator exhibits (slightly) larger bias than the cubic estimator, its smaller MSE highlights a superior bias–variance trade-off. In contrast, the linear estimator yields much larger MSE due to model mis-specification.

Table 3 Simulation results under the cubic outcome model

Note: FNDE = functional natural direct effect; FNIE = functional natural indirect effect; FTE = functional total effect; GAM = generalized additive model; Linear = parametric regression with a linear term; Cubic = parametric regression with linear, quadratic, and cubic terms; MSE = mean squared error.

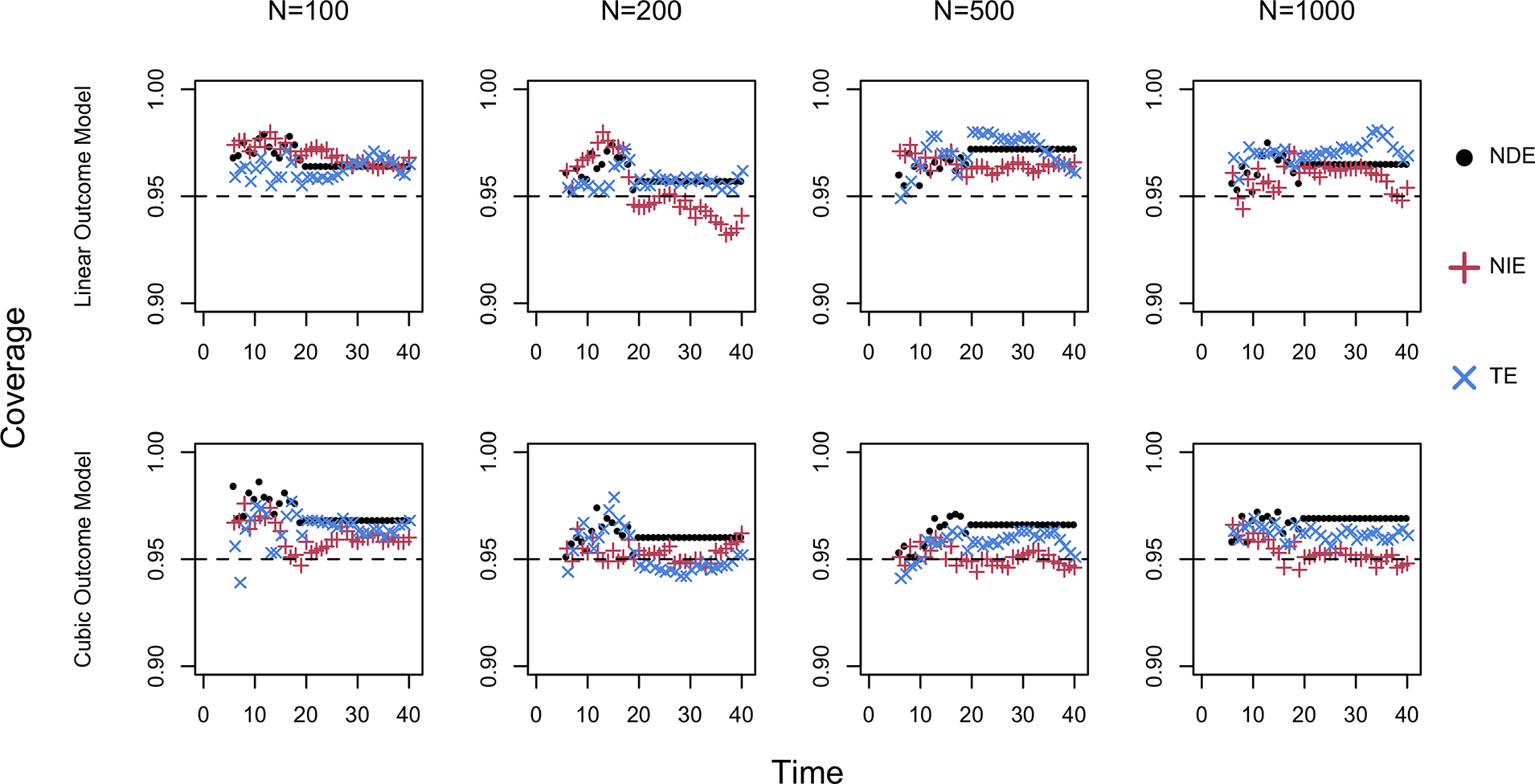

Figure 2 visually presents the coverage rates under linear and cubic outcome scenarios over the functional domain. In both scenarios, the coverage rates are close to the nominal 95% level across all the estimands and sample sizes. This indicates that the bootstrap procedure provides valid inference.

Figure 2 Coverage of 95% bootstrap confidence intervals. The horizontal black line provides a reference for the nominal level 95%; FNDE = functional natural direct effect; FNIE = functional natural indirect effect; FTE = functional total effect.

Overall, our simulation study demonstrates that the GAM estimator performs at least as well as, and often better than, correctly specified parametric models. This emphasizes its capacity to efficiently estimate functional causal effects without concerns about model mis-specification. Additionally, the proposed bootstrap-based method performs well in both outcome models, and it ensures reliable statistical inference with the GAM estimator.

6 Empirical example: ETA

6.1 Data and variables

In our study, we used the 2017 NAEP Grade 8 restricted-use process data for mathematics to estimate the functional total, direct, and indirect effects of receiving ETA. The 2017 NAEP math assessment was administered with multiple test forms, each consisting of two blocks. We used process data from one block, named

![]() $M3$

, across multiple test forms. Note that test forms were randomly assigned to students, so ignoring form differences should not introduce bias. The selected block contains 15 items, including multiple choice items, selected response items, and constructed response items. The actual items are available on the website: https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/nqt/searchquestions. Within each block, students could revisit and change their answers.

$M3$

, across multiple test forms. Note that test forms were randomly assigned to students, so ignoring form differences should not introduce bias. The selected block contains 15 items, including multiple choice items, selected response items, and constructed response items. The actual items are available on the website: https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/nqt/searchquestions. Within each block, students could revisit and change their answers.

The standard testing duration is 30 minutes, and the extended time adds extra 60 minutes, so the full testing time domain ranges from 1 to 90 minutes. In our data analysis, we set

![]() $k_0=6$

(i.e., 20% of the standard 30-minute testing time). That is, students’ decisions to use ETA are assumed to stabilize after the first 6 minutes, and thus, their early-test responses up to 6 minutes serve as post-treatment covariates. We select

$k_0=6$

(i.e., 20% of the standard 30-minute testing time). That is, students’ decisions to use ETA are assumed to stabilize after the first 6 minutes, and thus, their early-test responses up to 6 minutes serve as post-treatment covariates. We select

![]() $k_0=6$

because this initial 20% of the testing period serves as a reasonable window where students form their impressions and decide whether to use ETA. Importantly, we do not claim that

$k_0=6$

because this initial 20% of the testing period serves as a reasonable window where students form their impressions and decide whether to use ETA. Importantly, we do not claim that

![]() $k_0=6$

is universally correct. Rather, it is a context-specific choice based on prior literature and testing situations. Using

$k_0=6$

is universally correct. Rather, it is a context-specific choice based on prior literature and testing situations. Using

![]() $k_0=6$

, we incorporate a binary post-treatment covariate about whether the number of items accessed by 6 minutes exceeds the sample median. However, if researchers believe that decisions about the use of ETA are made prior to the test, they do not need to include post-treatment covariates, and the setting becomes Figure 1b. Or, if ETA use decisions are believed to stabilize later in the test, say 15 minutes, they may set

$k_0=6$

, we incorporate a binary post-treatment covariate about whether the number of items accessed by 6 minutes exceeds the sample median. However, if researchers believe that decisions about the use of ETA are made prior to the test, they do not need to include post-treatment covariates, and the setting becomes Figure 1b. Or, if ETA use decisions are believed to stabilize later in the test, say 15 minutes, they may set

![]() $k_0=15$

and incorporate additional test-taking covariates up to 15 minutes. Additionally, the end of the functional domain

$k_0=15$

and incorporate additional test-taking covariates up to 15 minutes. Additionally, the end of the functional domain

![]() $k_m$

was 76 minutes because the range (76, 90] has a relatively small number of students. For these reasons, we used the range [6, 76] as our functional domain of interest.

$k_m$

was 76 minutes because the range (76, 90] has a relatively small number of students. For these reasons, we used the range [6, 76] as our functional domain of interest.

Our target sample consists of students eligible for ETA, i.e., students with disabilities and English language learners. We excluded students who spent less than 2 minutes on the test due to extremely low efforts, as well as those who spent more than 76 minutes due to small sample sizes at time k. As a result, our final analysis sample included 4,130 studentsFootnote 3 (99.2% of the eligible sample for ETA in the process data), with about 66% of these students having disabilities, and 33% being English language learners without disabilities.

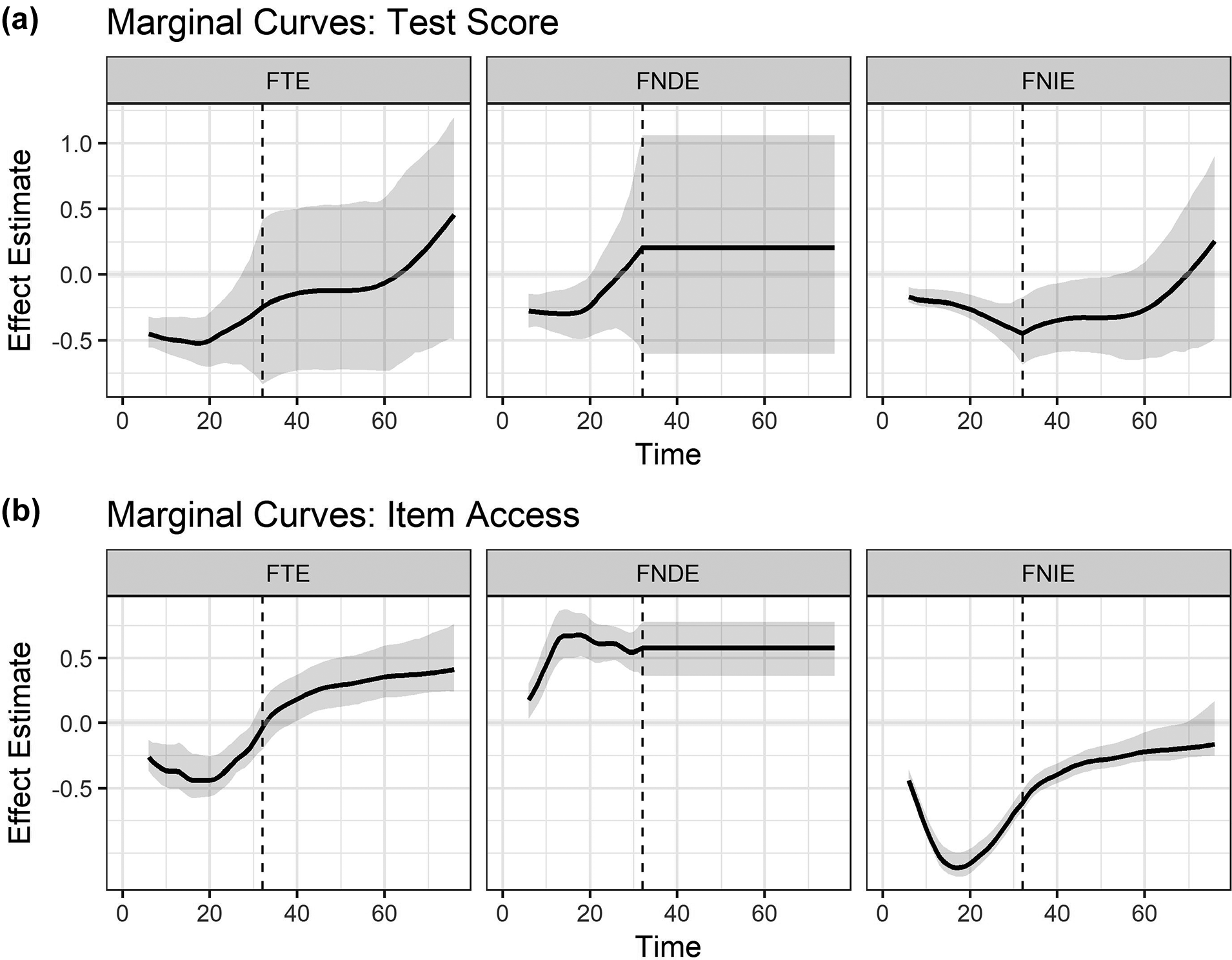

The functional outcomes of interest are test scores and item access (the number of items a student accessed). We constructed these two outcomes by transforming the raw, unstructured process data into a functional format. The first outcome is a student’s evolving test scores on a 15-item math test block over time, and ranges from 0 to 25 points. The second outcome is a student’s evolving item access over time, ranging from 0 to 15 items. In this study, we counted a student’s access to an item only if they spent more than 3 seconds on it because shorter visits are not considered effortful.

In addition, our treatment variable Z is whether a student received ETA or not, where

![]() $Z = 1$

denotes that a student received ETA and

$Z = 1$

denotes that a student received ETA and

![]() $Z = 0$

denotes that a student did not receive it. Our mediator variable T is whether a student used ETA or not, where

$Z = 0$

denotes that a student did not receive it. Our mediator variable T is whether a student used ETA or not, where

![]() $T = 1$

denotes that a student used ETA and

$T = 1$

denotes that a student used ETA and

![]() $T = 0$

denotes that a student did not use it.

$T = 0$

denotes that a student did not use it.

![]() $H $

is a student’s observed total response time, and when

$H $

is a student’s observed total response time, and when

![]() $H $

is larger than 32 minutes,

$H $

is larger than 32 minutes,

![]() $T = 1$

; otherwise,

$T = 1$

; otherwise,

![]() $T = 0$

. Following prior works (e.g., Lee & Suk, Reference Lee and Suk2025; Suk & Kim, Reference Suk and Kim2025), we use 32 minutes (rather than 30 minutes) as the end of the standard testing period due to interruptions in the typical testing experiences during the NAEP test. We assume one-sided noncompliance between the treatment Z and mediator T, where some ETA recipients did not use ETA, but all non-recipients did not use it. As in prior work, only about 30% of the recipients used ETA, and similar patterns were found among both students with disabilities and English language learners.

$T = 0$

. Following prior works (e.g., Lee & Suk, Reference Lee and Suk2025; Suk & Kim, Reference Suk and Kim2025), we use 32 minutes (rather than 30 minutes) as the end of the standard testing period due to interruptions in the typical testing experiences during the NAEP test. We assume one-sided noncompliance between the treatment Z and mediator T, where some ETA recipients did not use ETA, but all non-recipients did not use it. As in prior work, only about 30% of the recipients used ETA, and similar patterns were found among both students with disabilities and English language learners.

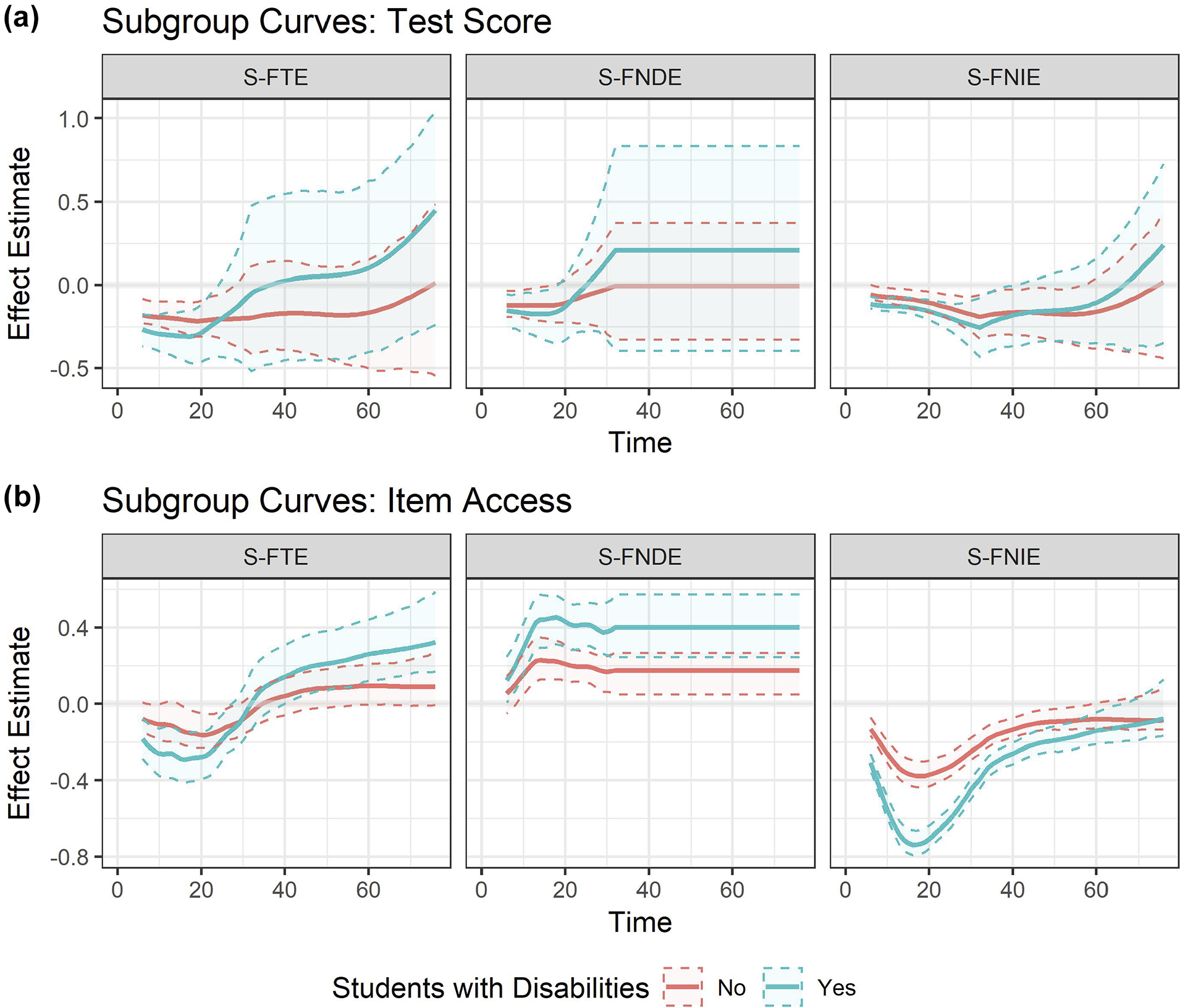

Furthermore, we used students’ disability status as a moderator V to explore subgroup effects. We also used a set of pre-treatment covariates X, including students’ sex, race, disability status, limited English proficiency status, free lunch status, parental education, interest in math, and a proxy for the current math course level. These variables partially explained why some eligible students did not receive or use ETA. For a full list of the variables used in data analysis, see Appendix S7 of the Supplementary Material.

Following our proposed methods discussed in Section 4.3, we used GAM estimators to estimate the FNDE, FNIE, and FTE, as well as their subgroup effects. Following the approach used in the simulation study, we employed the gam function from the R package mgcv (Wood, Reference Wood2023) to fit GAMs for both the outcome and post-treatment variable models. In the gam function, we selected knots=18 and gamma=1.5, which resulted in no diagnostic issue via the gam.check command. See Appendix S6 of the Supplementary Material for details on the implementation. We also conducted nonparametric bootstrapping to estimate confidence intervals for each effect in R software.