1. Introduction

Monitoring wood formation at high-temporal resolution provides critical insight into tree growth phenology and seasonal radial growth patterns. It enables researchers to track the main phases of annual ring development, including cambial activity and the rate and duration of xylem cell differentiation; that is, cell enlargement, secondary wall deposition and lignification and the eventual programmed cell death of fibres and vessels (Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Rathgeber, Frank, Fonti, Mäkinen, Prislan, Rossi, del Castillo, Campelo, Vavrčík, Camarero, Bryukhanova, Jyske, Gričar, Gryc, De Luis, Vieira, Čufar, Kirdyanov and Fournier2015; Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Lavrič, Ferlan, Vodnik and Eler2017; Rathgeber et al., Reference Rathgeber, Cuny and Fonti2016). Such studies therefore provide a detailed understanding of the kinetics of cell differentiation and xylem production over time (Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Rathgeber, Frank, Fonti and Fournier2014; Jyske et al., Reference Jyske, Mäkinen, Kalliokoski and Nöjd2014; Rathgeber et al., Reference Rathgeber, Rossi and Bontemps2011; Seo et al., Reference Seo, Eckstein, Jalkanen and Schmitt2011). Because of their fine-scale temporal resolution, xylogenesis observations are uniquely suited to assess tree growth responses to short-term environmental variability (Buttò et al., Reference Buttò, Peltier and Rademacher2025; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Deslauriers and Anfodillo2006) and explore climate response mechanisms (Dox et al., Reference Dox, Marien, Zuccarini, Marchand, Prislan, Gric, Flores, Gehrmann, Fonti, Lange, Penuelas and Campioli2022; Friend et al., Reference Friend, Eckes-Shephard, Fonti, Rademacher, Rathgeber, Richardson and Turton2019; Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Gričar, Čufar, de Luis, Merela and Rossi2019; Silvestro et al., Reference Silvestro, Mencuccini, García-Valdés, Antonucci, Arzac, Biondi, Buttò, Camarero, Campelo, Cochard, Čufar, Cuny, de Luis, Deslauriers, Drolet, Fonti, Fonti, Giovannelli, Gričar and Rossi2024). Beyond fundamental tree physiology, wood formation studies inform broader ecological and applied questions, including carbon and water cycling and forest ecosystem functioning (Campioli et al., Reference Campioli, Marchand, Zahnd, Zuccarini, McCormack, Landuyt, Lorer, Delpierre, Gričar and Vitasse2024; Silvestro et al., Reference Silvestro, Deslauriers, Prislan, Rademacher, Rezaie, Richardson, Vitasse and Rossi2025).

Most xylogenesis studies in angiosperms have focused on the phenology of xylem-ring formation, such as the onset and cessation of the above-mentioned differentiation phases, as well as the transition from early to late-wood in the case of ring-porous species. Xylem formation phenology has often been compared with leaf phenology to better understand the coordination between primary and secondary growth (e.g., Dox et al., Reference Dox, Marien, Zuccarini, Marchand, Prislan, Gric, Flores, Gehrmann, Fonti, Lange, Penuelas and Campioli2022; Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Jevšenak, Hafner, Prislan, Ferlan, Lavrič, Vodnik and Eler2022; Pérez-de-Lis et al., Reference Pérez-de-Lis, Rossi, Vázquez-Ruiz, Rozas and García-González2016; Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Gričar, de Luis, Smith and Čufar2013). While these studies provide valuable information on the start and end of the stem growing season, they sometimes differ in how phenological phases are defined and delimited. A key source of variation among studies is that vessels and fibres follow different differentiation timelines. In angiosperms, vessels generally differentiate over a shorter period and lignify sooner, whereas fibres continue differentiating later into the season (Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Koch, Čufar, Gričar and Schmitt2009). Because these cell types follow distinct temporal trajectories and kinetics, phenophases derived from one cell type do not necessarily correspond to those derived from another. Accordingly, studies have focused on different cell types depending on their research aims; for example, vessel development in studies emphasizing conductive function (Pérez-de-Lis et al., Reference Pérez-de-Lis, Rossi, Vázquez-Ruiz, Rozas and García-González2016), whereas others considered both vessels and fibres together to characterize overall xylogenesis (e.g., Dox et al., Reference Dox, Gricar, Marchand, Leys, Zuccarini, Geron, Prislan, Mariën, Fonti, Lange, Peñuelas, Van den Bulcke and Campioli2020; Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Čufar, De Luis and Gričar2018). Each of these choices is appropriate for the specific research question; however, when comparing phenological observations across studies, it is essential to recognize that they reflect different underlying developmental processes. Although these studies use similar definitions of phenophases (Supplementary Table 1), they rely on different criteria and analytical procedures to identify them (Dox et al., Reference Dox, Gricar, Marchand, Leys, Zuccarini, Geron, Prislan, Mariën, Fonti, Lange, Peñuelas, Van den Bulcke and Campioli2020; Lehnebach et al., Reference Lehnebach, Campioli, Gričar, Prislan, Mariën, Beeckman and Van den Bulcke2021; Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Gričar, Čufar, de Luis, Merela and Rossi2019). As a result, current approaches capture only parts of the xylogenesis process, and the resulting phenology estimates are not fully comparable across studies, highlighting a methodological gap that limits synthesis.

The heterogeneous spatial distribution of cell types in developing xylem further complicates efforts to reconstruct intra-seasonal differentiation kinetics. Two recent studies highlight this challenge: Noyer et al. (Reference Noyer, Stojanovic, Horácek and Pérez-de-Lis2023) applied a detailed two-dimensional analysis of cell enlargement by cell type and spatial position, while Lehnebach et al. (Reference Lehnebach, Campioli, Gričar, Prislan, Mariën, Beeckman and Van den Bulcke2021) developed a three-dimensional tomography approach; both show promising results but remain technically demanding and not yet standardizable. Given that several research groups are now monitoring xylem formation in angiosperms, the absence of a common protocol hinders the possibility of building comparable datasets, as has been successfully achieved in gymnosperms (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Silvestro, Liang, Mencuccini, Camarero, Rathgeber, Sylvain, Nabais, Giovannelli, Saracino, Saulino, Guerrieri, Gričar, Prislan, Peters, Čufar, Yang, Antonucci, Babushkina and Rossi2025; Silvestro et al., Reference Silvestro, Mencuccini, García-Valdés, Antonucci, Arzac, Biondi, Buttò, Camarero, Campelo, Cochard, Čufar, Cuny, de Luis, Deslauriers, Drolet, Fonti, Fonti, Giovannelli, Gričar and Rossi2024). Establishing harmonized recommendations for angiosperms would enable integration into larger networks, foster cross-biome comparisons and ultimately improve the incorporation of wood formation processes into vegetation and climate models.

Monitoring xylogenesis requires repeated sampling and microscopic analysis of developing xylem tissues, each providing a snapshot of cell development at a given date. Here, we do not provide a detailed description of sampling and sample preparation techniques, since these have been well established in the literature and most principles are shared between gymnosperms and angiosperms (Fonti et al., Reference Fonti, von Arx, Harroue, Schneider, Nievergelt, Björklund, Hantemirov, Kukarskih, Rathgeber, Studer and Fonti2025; Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Lavrič, Ferlan, Vodnik and Eler2017; Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Martinez Del Castillo, Skoberne, Špenko and Gričar2022; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Anfodillo and Menardi2006).

In this perspective, we provide recommendations for best practices in monitoring angiosperm wood formation, illustrated with examples from temperate and sub-Mediterranean species. The approach applies to a certain extent to other biomes, including tropical, subtropical, arid and boreal regions. We synthesize scattered methodological practices, propose new recommendations and workflows to harmonize angiosperm xylogenesis research and outline future research directions. Specifically, we address variation in wood type (ring-porous and diffuse-porous) and cell type (vessels, fibres and axial parenchyma) and provide a detailed set of annotated images to support cell differentiation phases identification. Finally, we present a research agenda to advance xylogenesis studies, highlighting four priorities: (1) systematic archiving and reuse of histological resources, (2) expanding studies to include branch and coarse root xylogenesis, (3) increasing coverage to capture genetic and environmental variability, and (4) moving toward kinetic analysis of wood formation.

2. Phenology and differentiation dynamics in temperate angiosperms

2.1. Key differentiation phases

The vascular cambium is a lateral meristem responsible for producing both secondary xylem and phloem tissues. It comprises two morphologically distinct types of cells: fusiform cambial cells, which are elongated and aligned axially, and ray cambial cells, which are smaller and radially oriented. Through periclinal (additive) divisions, fusiform cells produce xylem cells toward the pit and phloem cells toward the bark of the stem (Larson, Reference Larson1994). The resulting xylem derivatives include tracheary elements (i.e., tracheids and vessel elements), fibres and axial parenchyma, while phloem derivatives include sieve tubes, companion cells, phloem fibres, and axial parenchyma. Ray cambial cells divide to form ray parenchyma cells in both directions. Once the process of cell differentiation is complete, the cell becomes structurally and/or biochemically distinct from the cambial initial (Savidge, Reference Savidge1996).

The differentiation process of tracheary elements, fibres and parenchyma (ray and axial) in the xylem can be divided into four successive phases: (I) cell enlargement or post-cambial growth, (II) deposition of the multilayered secondary cell wall, (III) lignification of the cell wall, and (IV) programmed cell death (Luo & Li, Reference Luo and Li2022; Ye & Zhong, Reference Ye and Zhong2015). During the enlargement phase, the primary cell wall is formed. The cell expands due to the increasing volume of the vacuole until it reaches its final size. Once cell expansion ceases, secondary wall formation begins. A multilayered wall, composed of S1, S2 and S3 layers is deposited on the inner side of the primary wall. Lignification begins shortly after deposition of the S1 layer, initially in cell corners and the middle lamella, followed by deposition in the rest of the wall (Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Zupančič, Čufar, Koch, Schmitt and Oven2006). The phases of differentiation are interconnected: secondary wall thickening begins in the central part of the cell while cell elongation at the apices is still ongoing, and lignification initiates even before the complete deposition of the secondary wall layers (Pérez-de-Lis et al., Reference Pérez-de-Lis, Richard, Quilès, Deveau, Adikurnia and Rathgeber2024; Wardrop, Reference Wardrop1965). Fibres usually lignify more gradually and extensively, while vessel elements undergo relatively rapid lignification to quickly provide hydraulic conductivity. The final step, programmed cell death, removes the protoplast, enabling mature tracheary elements to function as conduits (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Guo, Cheng, Cheng, Liu, Ji, Liu, Cheng and Yang2022).

In temperate diffuse-porous species, such as Fagus sylvatica, Betula spp., Populus spp. and Acer spp., vessels are small, numerous and evenly distributed throughout the ring, making earlywood and latewood indistinguishable. In contrast, ring-porous species, such as Quercus spp. and Fraxinus spp., form very large earlywood vessels early in the growing season, followed by a sharp transition to latewood characterized by much smaller vessels and a higher proportion of fibres and parenchyma. These anatomical differences underpin the distinct phenological patterns and differentiation dynamics described in the following subsections, even though both porosity types present similar challenges for tracking xylogenesis, such as overlapping diffe rentiation phases, asynchronous cell-type development and spatial heterogeneity.

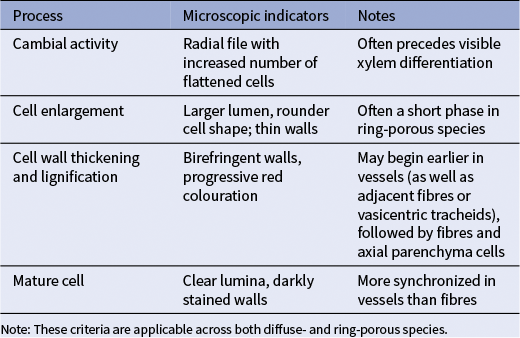

Figures 1–4 (and Supplementary Figure 1) illustrate how these anatomical contrasts translate into the seasonal progression of vessel, fibre and parenchyma differentiation in representative diffuse- and ring-porous species (Fagus sylvatica, Fraxinus ornus, Quercus spp.). Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 highlights how differentiation phases can be identified microscopically from cell shape, wall thickness, birefringence under polarized light and staining patterns. (Together, they provide the visual basis for the detailed descriptions that follow in the subsequent subsections, where we examine vessel, fibre and parenchyma differentiation in more depth).

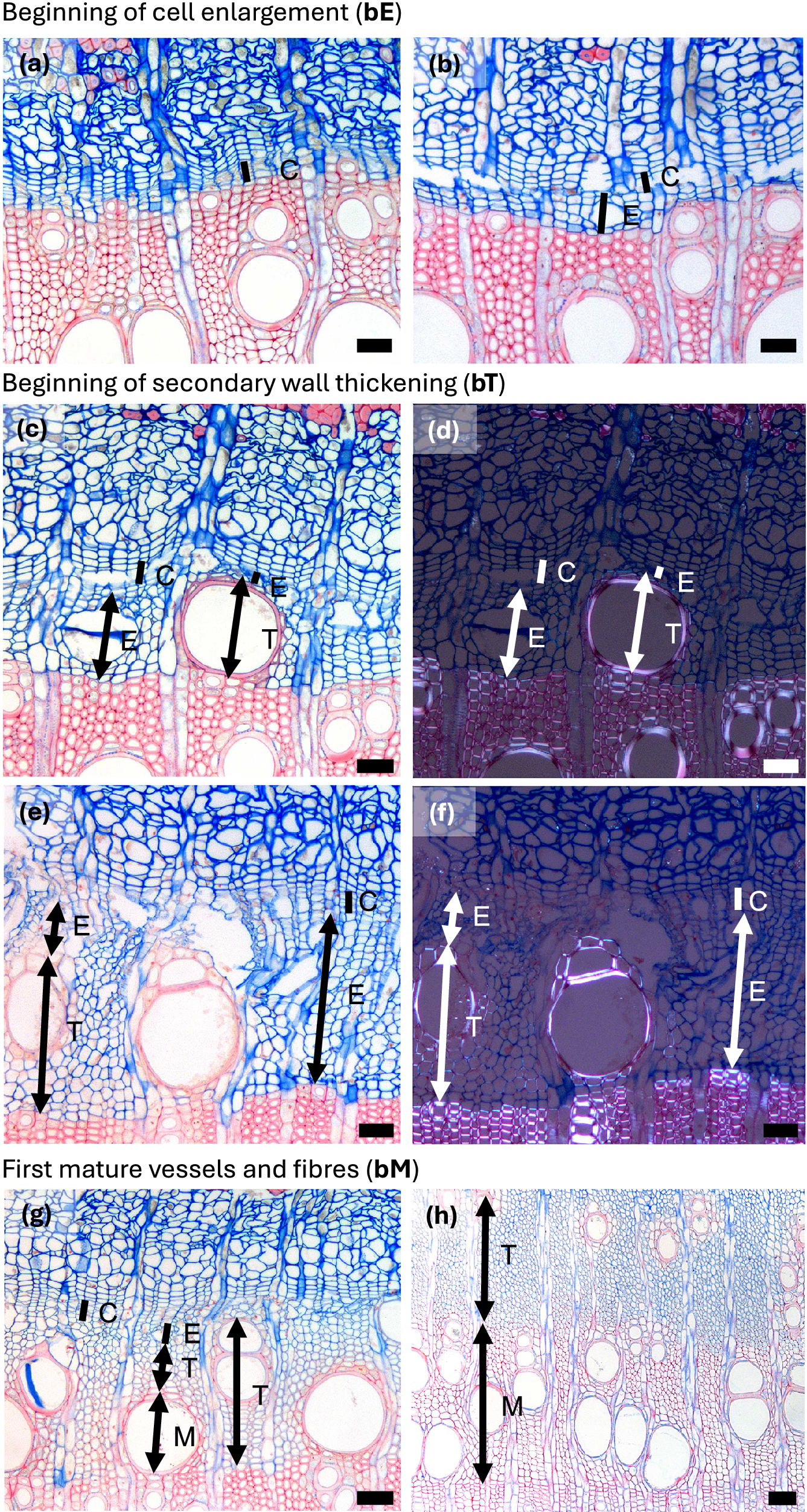

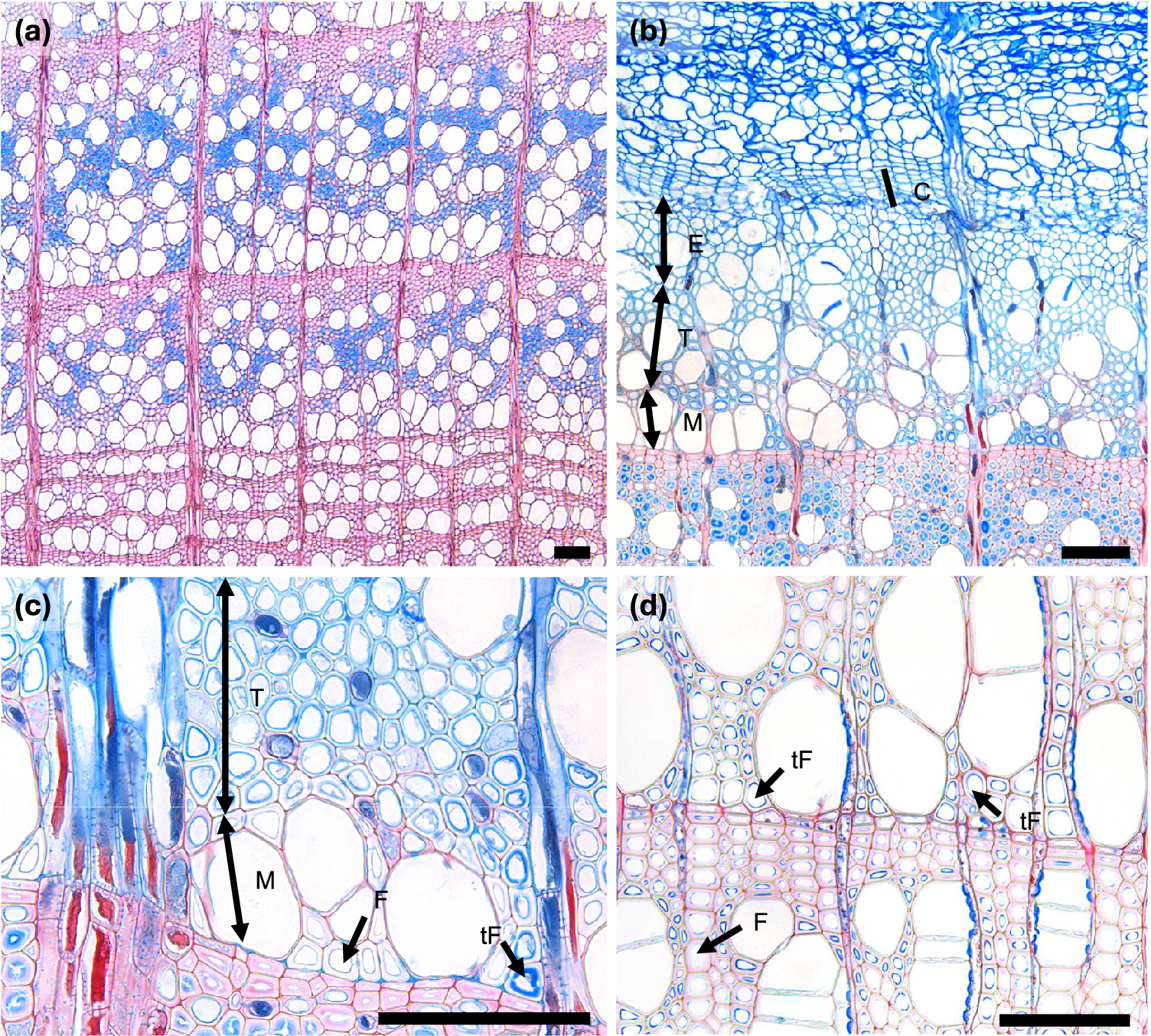

Figure 1. Spring phenological phases in diffuse porous beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). (a) The cambium is in a resting phase, typically consisting of four to five cambial cells (C) arranged in a radial row. (b) An increased number of cambial cells indicates the beginning of cambial production (bC). (c) Shortly after cell production begins, expanding cells or cells in post-cambial growth (E) can be observed beneath the cambium, marking the beginning of cell enlargement (bE). (d) Fibres and vessels were observed in the phase of radial enlargement. (e) The initial thickening of cell walls indicates the onset of secondary wall formation (T). (f) Under polarized light, birefringence becomes visible, confirming the beginning of secondary wall formation, i.e. cell-wall thickening (bT). (g) The onset of lignification is marked by a change in color in sections stained with a double-staining technique, first visible in vessels and the surrounding fibres. (h) Lignification begins in the cell corners and compound middle lamellae. (i) The first fully mature cells (bM), including vessels and fibres (M), can be identified by the uniform coloration of the cell walls and the absence of cellular content in the lumen. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Figure 2. Spring phenological phases in ring porous manna ash (Fraxinus ornus L.). (a, b) An increased number of cambial cells indicates the beginning of cambial production (bC). (c, d) Cell walls of initial cells show birefringence under polarized light as well as red colouring, indicating the beginning of secondary wall formation and lignification (bT). The differentiation dynamics of vessels in ring-porous manna ash can vary significantly; while some vessels may be nearly fully lignified, others may still be in the enlargement phase. (e, f) Secondary wall formation and lignification begin first in vessels and the vasicentric tracheids surrounding them, whereas nearby cells not in direct contact with vessels are often still in the enlargement phase. (g) The first-formed vessels are completely lignified, while the surrounding vasicentric tracheids are still undergoing secondary wall formation and lignification. (h) The first-formed vessels and vasicentric tracheids are fully mature, indicated by red coloration, whereas fibres and later-formed vasicentric tracheids are blue, indicating that they are still in earlier phases of differentiation. Abbreviations: cambial cells (C), cells in the phase of enlargement or post-cambial growth (E), cells in the phase of secondary wall formation and lignification (T), mature cells (M). Scale bars = 100 μm.

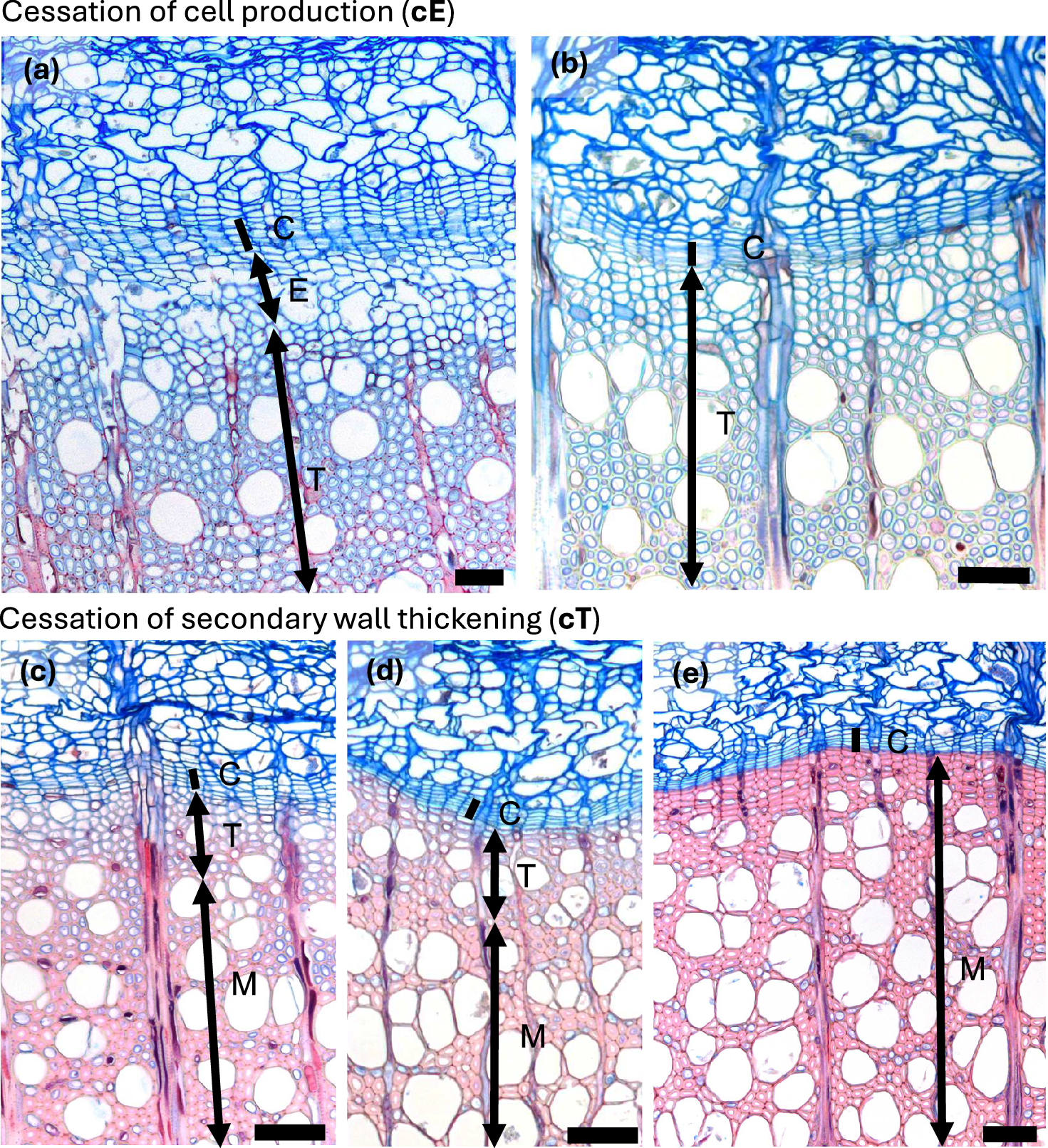

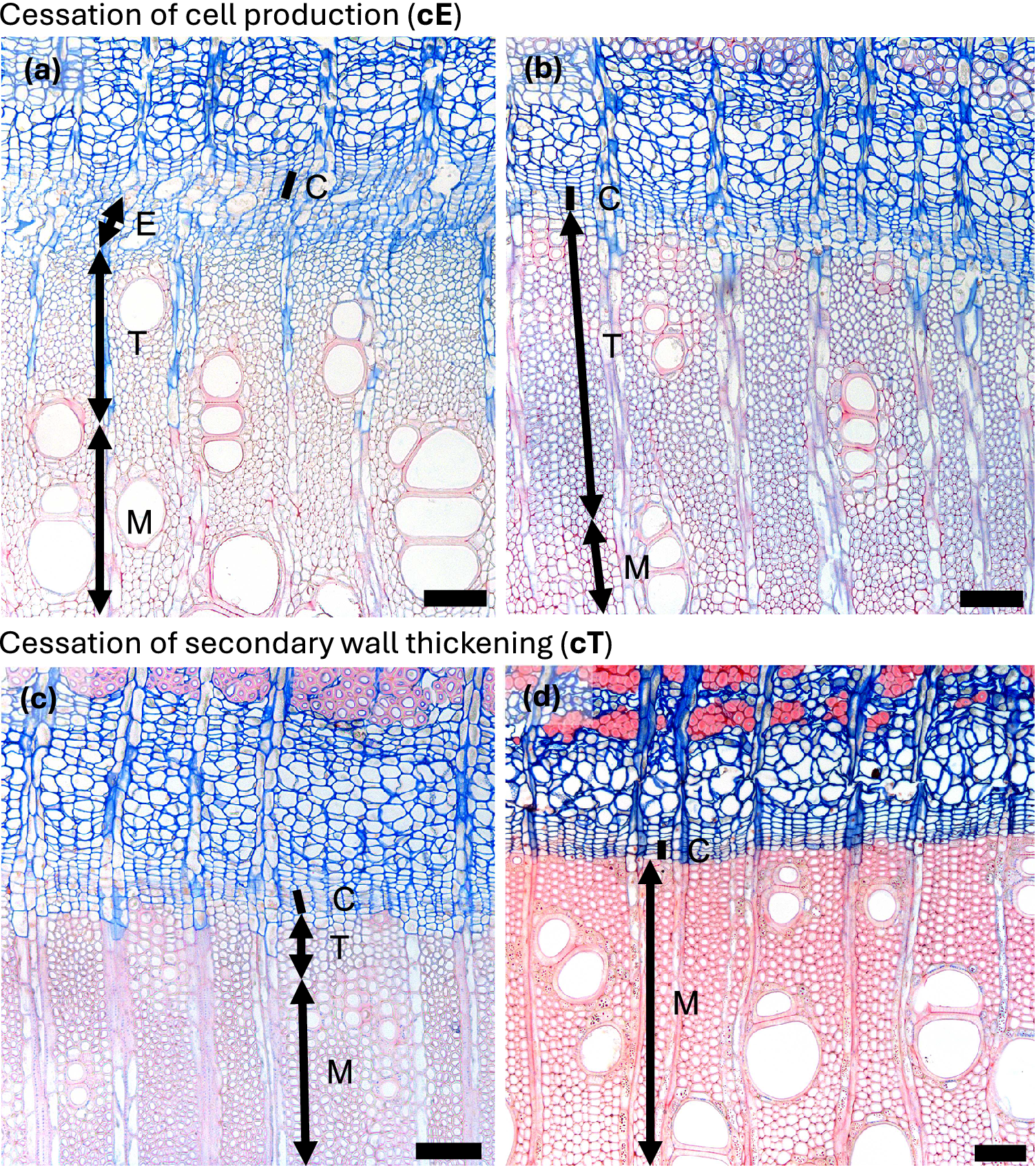

Figure 3. Autumn phenological phases in diffuse porous beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). (a) In the second half of the growing season, the width of the zone containing enlarging cells begins to decrease. (b) Cessation of cambial cell production (cE) is indicated by the absence of cells in the enlargement phase, although the last-formed fibres and vessels continue to differentiate. (c, d) In diffuse-porous beech, the differentiation dynamics of the last-formed vessels and fibres are less pronounced compared to those formed at the beginning of the growing season. (e) Cessation of cell wall deposition and lignification, i.e. thickening (cT) is marked by the presence of fully lignified terminal fibres. Abbreviations: cambial cells (C), cells in the phase of enlargement or post-cambial growth (E), cells undergoing secondary wall formation and lignification (T), mature cells (M). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Figure 4. Autumn phenological phases in ring porous manna ash (Fraxinus ornus L.). (a) An increased number of cambial cells (C) and a width enlarging zone (E) indicate ongoing cambial productivity. (b) A narrow cambium and the absence of enlarging cells indicate the cessation of cell enlargement (cE). (b, c) Following the cessation of cambial cell production, the last-formed cells continue secondary wall formation and lignification. Notably, vessels complete lignification earlier than the surrounding fibres. (d) Cessation of secondary wall formation and lignification, i.e. thickening (cT), is marked by the complete red staining of the cell walls in the last-formed fibres, indicating full lignification. Abbreviations: cambial cells (C), cells in the phase of enlargement or post-cambial growth (E), cells undergoing secondary wall formation and lignification (T), mature cells (M). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Table 1 Summary of the main anatomical indicators used to determine the phase of the xylem tissue across different cell types in angiosperm trees, as observed in microscopic sections

Note: These criteria are applicable across both diffuse- and ring-porous species.

2.2. Differentiation of vessels

For both diffuse- and ring- porous species, earlywood vessel elements enlarge rapidly shortly after the onset of cambial activity (e.g., Čufar et al., Reference Čufar, Cherubini, Gricar, Prislan, Spina and Romagnoli2011; Kudo et al., Reference Kudo, Yasue, Hosoo and Funada2015; Miodek et al., Reference Miodek, Gizińska, Włoch and Kojs2021; Puchałka et al., Reference Puchałka, Prislan, Klisz, Koprowski, Gricar, Puchałka, Koprowski, Prislan and Klisz2024; Umebayashi et al., Reference Umebayashi, Fukuda, Haishi, Sotooka, Zuhair and Otsuki2011). During enlargement, vessels are easily distinguished by their markedly larger lumina compared with surrounding cells and by thin, fragile primary walls, often displaying irregular outlines (Figures 1c–d, 2a–b, Supplementary Figure 1a). Once expansion ceases, secondary-wall deposition and lignification begin. At this phase, vessel walls still stain mainly blue with safranin–astra blue stains, but under polarized light, they exhibit birefringence, reflecting the alignment of cellulose microfibril of the forming S-layers; vessel outlines also appear smoother (Figures 1e–h, 2c–f, Supplementary Figure 1b–d). In both diffuse- and ring-porous species, earlywood vessels are among the first xylem cells to complete differentiation (Figures 1i, 2g, Supplementary Figure 1d). Their rapid maturation is functionally critical, as it restores stem hydraulic conductivity after winter embolism (Hacke & Sperry, Reference Hacke and Sperry2001; Sperry et al., Reference Sperry, Nichols, Sullivan and Eastlack1994).

In ring-porous species, once the large earlywood vessels have differentiated, the cambium gradually transitions to producing latewood, characterized by smaller vessels and a higher proportion of fibres and axial parenchyma. Latewood vessel differentiation proceeds more slowly than that of earlywood vessels and often continues well into the late growing season (Figure 2h, Supplementary Figure 1d–f).

2.3. Differentiation of fibres and axial parenchyma

Fibres and axial parenchyma cells typically begin differentiating alongside vessels early in the growing season, following the same progression as in vessels; the main difference is that fibres undergo less radial expansion and develop thicker secondary walls than vessels (Figures 1i, 2e–f) (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001; Samuels et al., Reference Samuels, Kaneda and Rensing2006). Importantly, initial fibres continue wall thickening and lignification well into late summer (Figures 3c–d, 4c–d), a pattern that may also be related to differences in lignin composition, as vessels and fibres incorporate different proportions of guaiacyl and syringyl monolignols during wall formation (Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Koch, Čufar, Gričar and Schmitt2009). This substantial overlap among differentiating vessels, fibres and parenchyma can complicate phenological assessments, especially when early-phase cell morphologies are difficult to distinguish.

2.4. Asynchronous differentiation of vessels and fibres

Differentiation of vessels, fibres and axial parenchyma is asynchronous following overlapping but distinct developmental timelines (Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Gričar, de Luis, Smith and Čufar2013). Early-season vessels complete differentiation more rapidly than fibres formed at the same time (Figures 1i, 2g) (Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Koch, Čufar, Gričar and Schmitt2009). Toward the end of the growing season, this pattern reverses: vessel differentiation slows, while fibre differentiation accelerates (Figures 3b–d, 4b–d). In addition to these temporal differences, xylem differentiation is also spatially heterogeneous. The progression and rate of differentiation in both vessels and fibres vary with their distance from ray parenchyma; cells adjacent to rays initiate wall formation and lignification earlier than more distal cells (Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Koch, Čufar, Gričar and Schmitt2009), a spatial pattern also observed in conifers (Donaldson, Reference Donaldson2001). In ring-porous species, early-season fibres and vasicentric tracheids located near vessels begin wall formation and lignification sooner than those located farther away (Figure 2e–f), reflecting functional coordination among hydraulically related tissues (Noyer et al., Reference Noyer, Stojanovic, Horácek and Pérez-de-Lis2023). Even among vessels (and the surrounding fibres) formed concurrently, differentiation can vary substantially. For example, one vessel may appear fully mature while an adjacent vessel is still undergoing enlargement (Figure 2c–g), illustrating that individual cells do not differentiate uniformly along their length: differentiation often starts in the central part of the cell and progresses toward both tips. When observed in transverse section, however, the exact position along the cell’s longitudinal axis is unknown, longitudinal gradients in maturation may appear as differences among neighbouring cells. These temporal and spatial differences have important implications for the interpretation of xylogenesis dynamics.

2.5. The specific case of tension wood

Tension wood is a specialized type of reaction wood formed in angiosperms to adjust stem and branch position, for example, on the upper side of leaning trunks growing on slopes or in response to displacement by wind or other mechanical forces (Jourez et al. Reference Jourez, Riboux and Leclercq2001; Groover, Reference Groover2016).

The presence of tension wood in angiosperm growth rings can lead to misinterpretation of xylogenesis phenophases if not recognized. Tension wood is characterized by the formation of gelatinous fibres (G-fibres) that contain a cellulose-rich gelatinous (G) layer within the secondary wall. This G-layer has very low lignin content and therefore stains differently from fibres without tension wood (Figure 5a). Under safranin–astra blue, the G-layer typically appears intensely blue, in contrast to the red or purple tones of lignified secondary walls. As a result, fibres containing a G-layer may resemble cells that are still undergoing secondary-wall formation. Although mature fibres lack cell contents, as opposed to developing cells, the weakly lignified G-layer can mimic the staining pattern of earlier differentiation phases, complicating phenophase assignment (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. Presence of tension wood in beech growth rings. (a) Fully formed growth ring with a high proportion of tension wood fibres. Due to the presence of a cellulose-rich gelatinous (G) layer, their cell walls stain intensely blue with safranin–astra blue. (b) Developing a growth ring containing tension wood, where G-fibres can already be identified during secondary-wall formation. (c–d) Comparison between normal fibres (F) and tension wood fibres (tF): normal fibres are characterized by a lignified secondary wall staining red to purple with safranin–astra blue, whereas tension wood fibres show the deposition of a cellulose-rich G-layer, visible as a distinct, darker blue layer with weak or absent lignin staining.

However, G-fibres can already be distinguished during secondary-wall deposition: compared with fibres developing a normal S2 layer, their thin secondary walls stain more intensely blue due to their high cellulose content and show weak or absent lignin staining (Figure 5c–d). This provides an important diagnostic cue for identifying tension-wood formation before the G-layer is fully expressed. However, in species such as Populus spp. tension wood may be present only in very small amounts or restricted to narrow zones, sometimes appearing merely as a thin G-layer in the corners of fibre walls, making it difficult to detect without high-quality staining or close microscopic inspection.

Growth rings containing substantial tension wood are often wider, reflecting increased and prolonged cambial activity and enhanced fibre production on the tension side of leaning stems or branches (Abedini et al., Reference Abedini, Clair, Pourtahmasi, Laurans and Arnould2015; Pilate et al., Reference Pilate, Déjardin, Laurans and Leplé2004). For reliable phenological assessments, we recommend avoiding tension wood whenever possible by sampling perpendicular to the tension wood (at 90°). When tension wood is present in small amounts, its impact on xylogenesis interpretation is usually limited. However, when it occurs in larger proportions, it can bias estimates of the duration and timing of fibre wall thickening and maturation, potentially leading to false conclusions if not considered.

3. Recommendations for quantifying the developmental phases of xylogenesis

3.1. Width-based approach

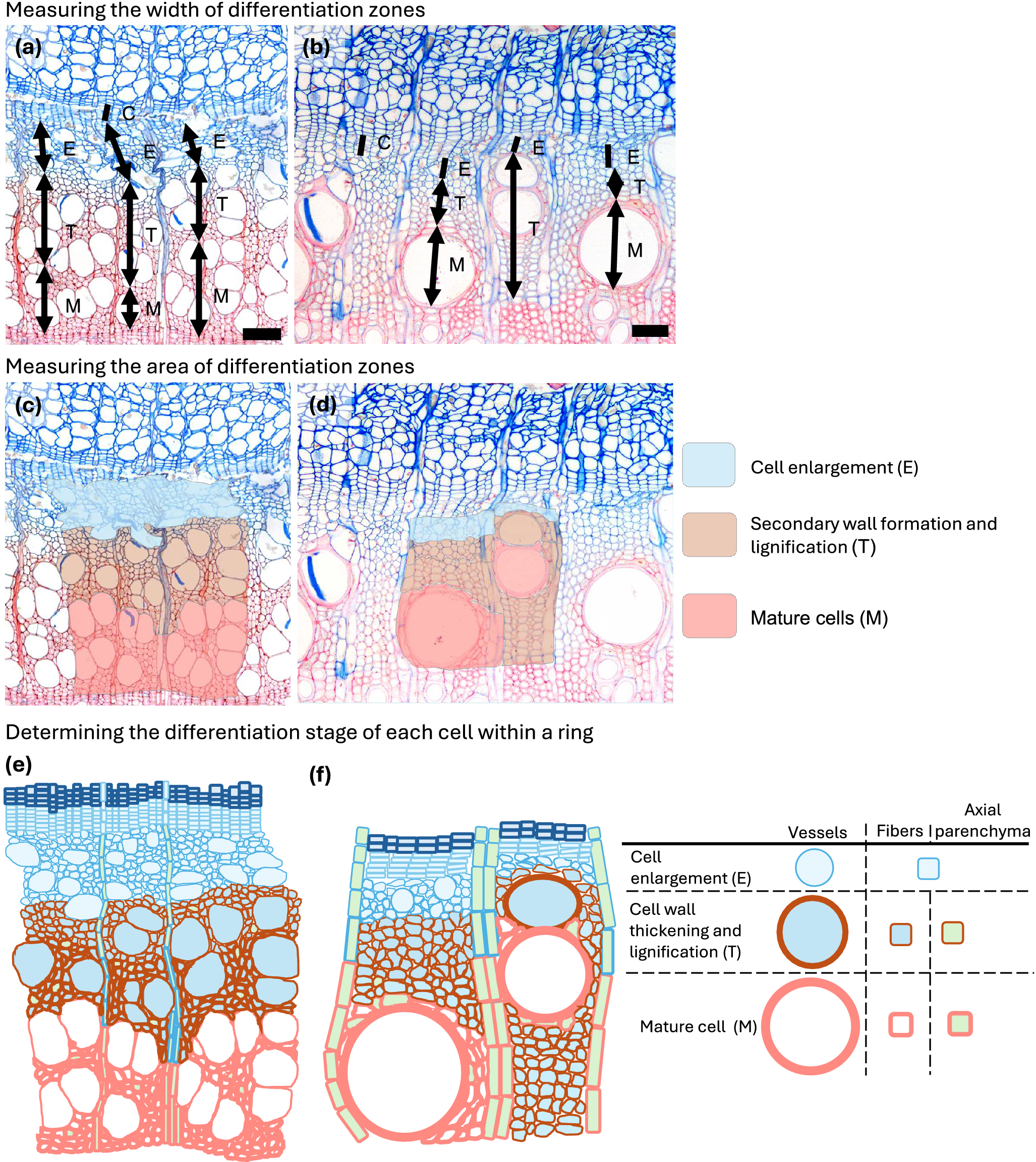

In addition to illustrating developmental features, Figures 1–4 also demonstrate common approaches for measuring xylogenesis in angiosperms. The underlying principle parallels the method used in conifers, where, along at least three radial files in the sample, cambial cells (C) and tracheids in enlargement (E), in secondary-wall formation and lignification (T) and in maturity (M) are counted. In angiosperms, rather than counting individual cells, the radial width of each band comprising cells in a similar differentiation phase (E, T and M) is measured at three positions within each sample (Figure 6a–b and Table 1). For the cambial zone specifically, either the number of cambial cells can be counted, or the radial width of the cambial band can be measured. This width-based approach is straightforward and enables rapid assessment of cambial activity and xylem cell development. However, it may obscure cell-specific differentiation dynamics as described in Section 2. The measurements of the width of the band can be expressed in micrometres or as a proportion of the ring width (i.e. sum E, T and M).

Figure 6. Overview of three approaches for quantifying xylogenesis in angiosperms. (a–b) Width-based approach, illustrated for Fagus (a) and Fraxinus (b). In this method, the widths of the differentiation zones: cambial cells (C), enlarging cells (E), cells undergoing secondary-wall thickening and lignification (T), and mature cells (M)—are measured along selected radial files. (c–d) Area-based approach, shown for Fagus (c) and Fraxinus (d), where the anatomical areas occupied by cells in the same differentiation phases are delineated; when a phase occurs in disconnected patches, each patch is outlined separately and their areas summed (d). (e–f) Cell-based approach, illustrated for Fagus (e) and Fraxinus (f). Individual cells within a defined region are classified according to their differentiation phase, enabling detailed, cell-type-specific assessment of xylogenesis.

3.2. Area-based approach

To better capture the irregular, discontinuous and spatially heterogeneous differentiation of xylem tissue, an area-based approach can be used. In this method, a portion of the transverse section that includes the cambial zone and the newly forming annual ring is selected for analysis. Measurements may be taken in a representative portion of the sample or across the full width of the microcore.

Within this region, the area occupied by cells in the same differentiation phase is delineated and quantified (Figure 6c–d; Table 1; Supplementary Figure 2b). The area outline should follow the actual anatomical distribution of cells belonging to each phase (E, T and M). When the same differentiation phase occurs in disconnected patches, each patch should be outlined separately and their areas summed (as illustrated in Figure 6d). Expressing the area of each phase as a relative proportion of the total analysed area (i.e. sum E, T and M) enables comparison among samples even when the size or shape of the analysed region differs.

3.3. Cell-based approach

A cell-based approach involves identifying every cell within the selected region (or the entire sample), making it possible to distinguish the phenology and differentiation kinetics of individual cell types (Figure 6e–f and Table 1). This approach has already been demonstrated conceptually by Noyer et al. (Reference Noyer, Stojanovic, Horácek and Pérez-de-Lis2023), who mapped individual cells and assigned differentiation phases across two-dimensional sections of the enlarging annual ring. Although highly informative, such analyses remain time-consuming.

Recent advances in automated and semi-automated image analysis may substantially reduce processing time. Cell-detection models already exist for quantitative wood anatomy in microtome sections (e.g., ROXAS by von Arx & Carrer, Reference von Arx and Carrer2014) and for X-ray scans (e.g., Roboflow, Van den Bulcke et al., Reference Van den Bulcke, Verschuren, De Blaere, Vansuyt, Dekegeleer, Kibleur, Pieters, De Mil, Hubau, Beeckman, Van Acker and wyffels2025). Building on these tools, additional models could be trained to recognize xylogenesis phases (C, E, T and M) based on staining patterns, anatomical features or cell-wall density.

Such developments would allow the reconstruction of cell-type-specific differentiation trajectories, enabling comparisons of timing and rates of development using either cell counts or areas occupied by each cell type. This approach is particularly valuable for understudied cell types, such as axial and ray parenchyma differentiation. Ultimately, this approach would generate complementary datasets, such as xylogenesis of vessels, fibres, axial as well as parenchyma, providing a more complete representation of angiosperm xylem formation.

4. Recommendations to assess xylem formation phenology and growth dynamics

After measurements have been performed (whether by counting cells, measuring the width or area of differentiation zones or applying cell-based approaches), the next step is to assess xylem phenology and growth dynamics. Because multiple analytical approaches exist, the interpretation of the same dataset can differ depending on how phenophase boundaries are defined and how seasonal growth patterns are modelled.

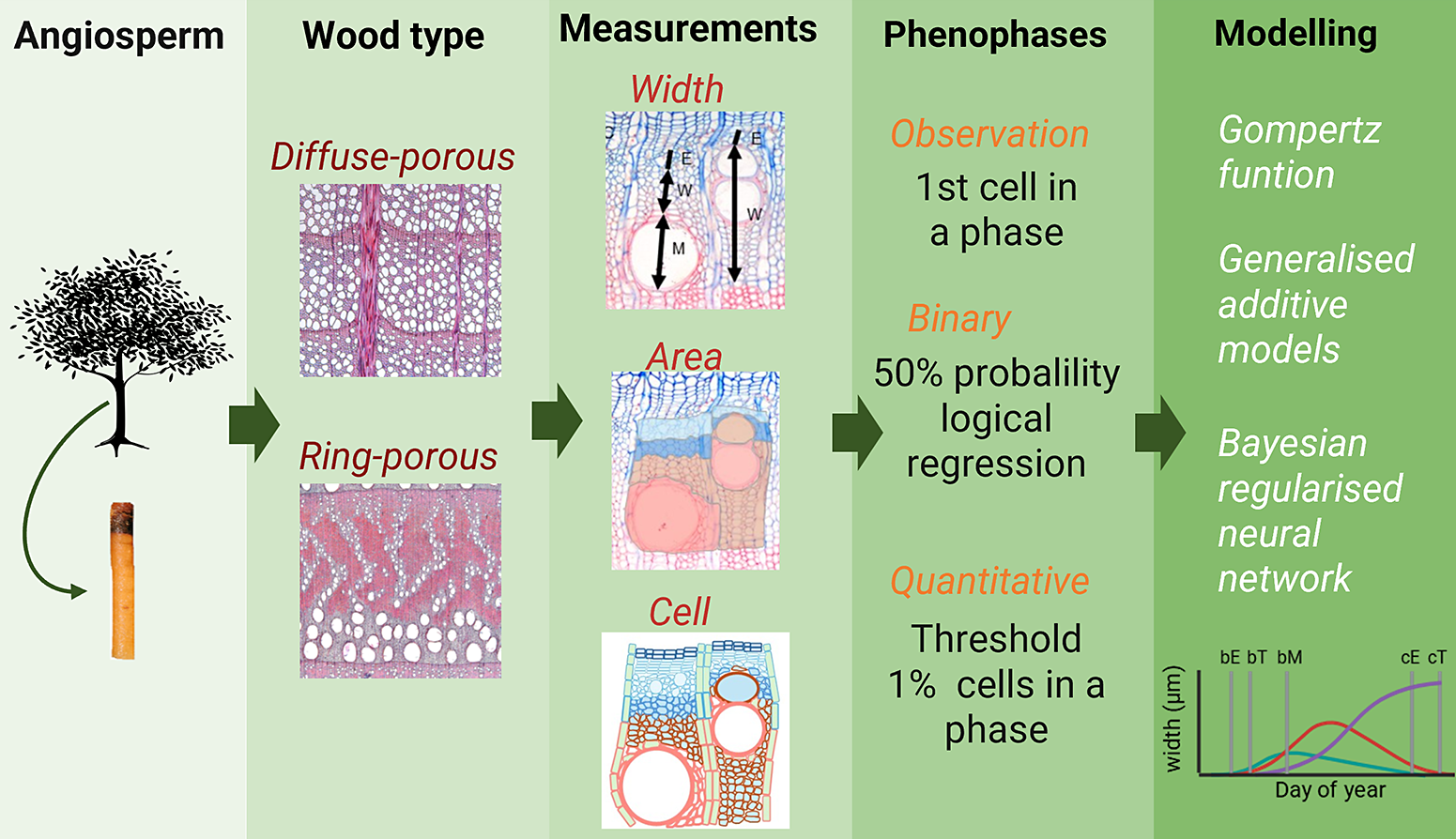

Figure 7. Schematic view of the specificities and methods to measure xylogenesis, define phenophases and model wood growth in angiosperm trees presented in this perspective paper.

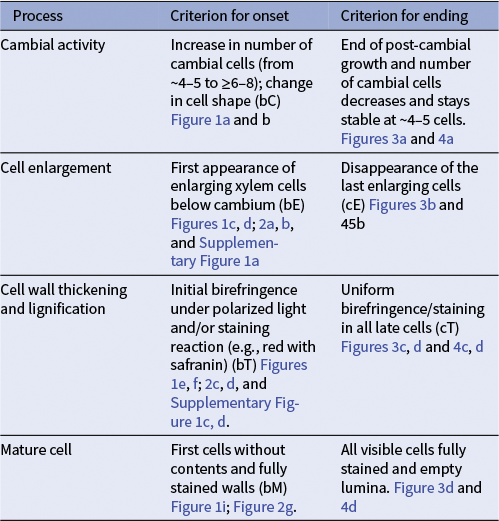

Consistent phenophase definitions are essential for comparing xylogenesis timing across species, sites and studies. Figures 1–4 and Table 2 summarize the key anatomical markers that indicate the onset and cessation of the main differentiation phases, such as the presence of enlarging cells, birefringence of secondary walls during thickening, uniform staining of mature cells and the absence of cytoplasm. These anatomical features provide the foundation for identifying phenophases and serve as reference criteria for the quantitative and statistical approaches introduced below. Supplementary Table 1 further offers harmonized definitions aligned with established gymnosperm terminology, facilitating consistency across taxa.

Table 2 Criteria to defined the onset and end of phenophases visually

Beyond identifying phenological dates, modelling weekly measurements is crucial for describing how xylem formation progresses through the season; its rate, duration and temporal pattern. However, estimates of these parameters may differ depending on the chosen modelling approach (e.g., Gompertz curves, generalized additive models (GAMs) and Bayesian neural networks (BRNN)) (e.g., Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Rathgeber, Kiessé, Hartmann, Barbeito and Fournier2013; Jevšenak et al., Reference Jevšenak, Gričar, Rossi and Prislan2022), reinforcing the need for reporting and careful interpretation.

The following sections provide recommendations for defining key developmental phases and for selecting appropriate tools to quantify xylem growth dynamics.

4.1. Identifying xylem phenology: Key developmental phases and phenological dates

In practice, most studies determine the onset of the growing season by identifying the first enlarging cells, the first appearance of secondary-wall thickening and the first fully mature cells (e.g., Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Dox, Gričar, Prislan, Van Den Bulcke, Fonti and Campioli2021; Prislan et al., Reference Prislan, Gričar, Čufar, de Luis, Merela and Rossi2019), mirroring approaches long used in gymnosperms (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Silvestro, Liang, Mencuccini, Camarero, Rathgeber, Sylvain, Nabais, Giovannelli, Saracino, Saulino, Guerrieri, Gričar, Prislan, Peters, Čufar, Yang, Antonucci, Babushkina and Rossi2025; Silvestro et al., Reference Silvestro, Mencuccini, García-Valdés, Antonucci, Arzac, Biondi, Buttò, Camarero, Campelo, Cochard, Čufar, Cuny, de Luis, Deslauriers, Drolet, Fonti, Fonti, Giovannelli, Gričar and Rossi2024). At the end of the growing season, the cessation of enlargement and the point at which the last-formed cells are fully mature are commonly used to define the end of differentiation (Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Lavrič, Ferlan, Vodnik and Eler2017). Because vessels, fibres and axial parenchyma do not differentiate synchronously in angiosperms, we recommend recording cell-type-specific phenophases whenever possible; for example, distinguishing the onset of secondary-wall formation in vessels versus fibres and noting the timing at which each cell type reaches full maturity. Late-season assessments should pay particular attention to when the final fibres and vessels complete differentiation, as their timing can diverge substantially.

In gymnosperms, Rathgeber et al. (Reference Rathgeber, Santenoise and Cuny2018) proposed, through the CAVIAR framework, using logistic regression to describe the seasonal probability of each differentiation phase. In this approach, the presence or absence of a given differentiation phase is modelled, and the phenophase dates correspond to the day when the modelled probability of a phase reaches 50%. This approach offers a consistent criterion for identifying the onset or cessation of cell enlargement or cell wall thickening. Because this method estimates the point at which a phase is well established across radial files, it may yield onset dates that are slightly later than the initial microscopical observation of the appearance of the first differentiating cells, but it provides a robust measure of the generalized phenological signal. Although originally developed for gymnosperms, the same principle can also be applied to angiosperms.

To define the cessation of cell enlargement or secondary-wall formation, Dox et al. (Reference Dox, Gricar, Marchand, Leys, Zuccarini, Geron, Prislan, Mariën, Fonti, Lange, Peñuelas, Van den Bulcke and Campioli2020) proposed that a phase has ended when the measured width of the corresponding zone represents less than 0.5% of the total differentiating ring for at least three consecutive sampling dates. Marchand et al. (Reference Marchand, Gričar, Zuccarini, Dox, Mariën, Verlinden, Heinecke, Prislan, Marie, Lange, Van den Bulcke, Penuelas, Fonti and Campioli2025) later adopted a slightly broader cut-off (1%) to minimize the influence of rare late-season cells that do not reflect sustained activity. These criteria provide objective and reproducible estimates of late-season phenophases. Comparable proportional rules could be applied to early-season transitions, for example, defining the onset of wall thickening when the width (or area) of the thickening zone exceeds 1% of the total increment.

Because different analytical approaches (first appearance, logistic regression and proportional criteria) do not necessarily yield identical dates, we recommend that studies explicitly report the method used. When synthesizing results across studies, priority should be given to consistently defined metrics (e.g., proportional criteria) or variability should be interpreted with caution as partly methodological. In the long term, adopting harmonized quantitative criteria (applied to widths, areas or cell counts) would greatly improve comparability among angiosperm xylogenesis studies.

4.2. Modelling xylem growth dynamics

Weekly measurements of xylem growth ring formation can be modelled using parametric growth curves (e.g., Gompertz functions; Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Deslauriers and Anfodillo2006) or flexible smoothing approaches such as generalized additive models (GAMs) (Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Rathgeber, Kiessé, Hartmann, Barbeito and Fournier2013) and Bayesian regularized neural network (BRNN) (Jevšenak et al., Reference Jevšenak, Gričar, Rossi and Prislan2022). These models reconstruct the continuous progression of xylem development from discrete sampling points, enabling quantification of growth rates and comparison of growth dynamics across years, species or experimental treatments (Buttò et al., Reference Buttò, Peltier and Rademacher2025).

Growth-curve models also help identify additional phenological events during xylem ring formation (e.g., the timing of maximum growth rate). When combined with quantitative wood-anatomy data (e.g., cell dimensions, wall thickness and lumen area), these models can also be used to determine transition dates between earlywood and latewood (e.g., Gricar et al., Reference Gricar, Cufar, Eler, Gryc, Vavrcík, de Luis and Prislan2021) and to infer cell-type-specific developmental kinetics (Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Rathgeber, Frank, Fonti and Fournier2014, Reference Cuny, Fonti, Rathgeber, von Arx, Peters and Frank2019).

Because different modelling approaches may yield slightly different estimates (Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Rathgeber, Kiessé, Hartmann, Barbeito and Fournier2013; Jevšenak et al., Reference Jevšenak, Gričar, Rossi and Prislan2022), we recommend that studies clearly report the modelling framework used and interpret model-derived parameters considering methodological differences.

5. Future research directions

5.1. Archiving and future use of histological resources

We propose that preserving histological slides and their digital copy using scanning microscopes (e.g., Fonti et al., Reference Fonti, von Arx, Harroue, Schneider, Nievergelt, Björklund, Hantemirov, Kukarskih, Rathgeber, Studer and Fonti2025) or alternative methods, should become a standard practice. This would allow current observations to be digitally documented and enable future re-examination, facilitating data verification and maximizing the long-term scientific value of collected samples. For instance, phloem tissue is consistently present on the histological slides prepared for xylem studies, yet it is rarely analysed (Gričar, Reference Gričar2024; Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Jevšenak, Giagli, Eler, Tsalagkas, Gryc, Vavrčík, Čufar and Prislan2024; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liesche, Crivellaro, Doležal, Altman, Chiatante, Dimitrova, Fan, Fu, Forest, Gričar, Heuret, Isnard, Maurin, Montagnoli, Rathgeber, Tsedensodnom, Trueba and Salmon2025). Moreover, such preserved materials open the door for detailed anatomical analyses, enabling the quantification of wood and phloem traits and supporting investigations into relationships between growth processes and anatomical structure (see Section 6.4). Ideally, imaging should also capture birefringence channels to detect the onset of secondary cell wall formation.

Archived slides can also be reanalysed using alternative or updated methods, such as switching between counting- and measurement-based approaches, extending the analysis to additional bandwidths or training artificial intelligence models (Altman et al., Reference Altman, Altmanova, Fibich, Korznikov and Fonti2025). This contributes to the creation of a robust and standardized, large-scale dataset. Looking ahead, these existing histological resources can also play a pivotal role in calibrating emerging technologies, such as high-resolution X-ray computed tomography (HRXCT) (Lehnebach et al., Reference Lehnebach, Campioli, Gričar, Prislan, Mariën, Beeckman and Van den Bulcke2021).

5.2. Assessing xylogenesis beyond the stem: Branches and coarse roots

Xylogenesis research has historically focused on stems, with limited data on branch and coarse root development. Yet different organs may follow distinct phenological patterns, influenced by their function, age and environment (Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Lavrič, Ferlan, Vodnik and Eler2017; Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Gričar, Zuccarini, Dox, Mariën, Verlinden, Heinecke, Prislan, Marie, Lange, Van den Bulcke, Penuelas, Fonti and Campioli2025; Silvestro et al., Reference Silvestro, Deslauriers, Prislan, Rademacher, Rezaie, Richardson, Vitasse and Rossi2025).

Xylem in branches is generally narrower, with ring widths approximately three- to fivefold smaller and vessels of smaller diameter compared with the stem; a pattern consistent in both ring-porous and diffuse-porous species (Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Lavrič, Ferlan, Vodnik and Eler2017; Lintunen et al., Reference Lintunen, Kalliokoski and Niinemets2010; Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Gričar, Prislan, Dox, Verlinden, Flores and Campioli2025). The measurement method detailed for stems (Section 3.5) is equally applicable to branches (Supplementary Figure 2a–c), and the phenophases defined for stem xylogenesis can also be identified in branches using the same criteria (Section 5). Tension wood or reaction wood can be present and is usually discarded from the analysis to limit bias of xylogenesis measurements induced by it (Gričar et al., Reference Gričar, Lavrič, Ferlan, Vodnik and Eler2017; Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Gričar, Prislan, Dox, Verlinden, Flores and Campioli2025). Coarse roots typically form larger and more uniform earlywood vessels, with vessel size increasing further along the root system, a trend observed in both ring- and diffuse-porous species (Lintunen et al., Reference Lintunen, Kalliokoski and Niinemets2010; Lübbe et al., Reference Lübbe, Lamarque, Delzon, Torres Ruiz, Burlett, Leuschner and Schuldt2022; Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Gričar, Zuccarini, Dox, Mariën, Verlinden, Heinecke, Prislan, Marie, Lange, Van den Bulcke, Penuelas, Fonti and Campioli2025). The xylem ring is usually dominated by earlywood, while latewood is minimal or absent, resulting in less distinct ring boundaries compared to the stems. Wood formation in coarse roots can vary markedly around the circumference (Lintunen et al., Reference Lintunen, Kalliokoski and Niinemets2010; Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Gričar, Zuccarini, Dox, Mariën, Verlinden, Heinecke, Prislan, Marie, Lange, Van den Bulcke, Penuelas, Fonti and Campioli2025). To account for this heterogeneity, it is recommended to measure width, area or cell-based methods in at least four locations evenly distributed around the cross-section (Supplementary Figure 2). While all stem-defined phenophases can be identified in coarse roots, the cessation of cell enlargement and cell wall thickening for fibres and parenchyma (e.g., cE and cT) is often unclear. This is due to autumn and winter xylem formation producing narrow, flattened fibres and parenchyma cells (Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Gričar, Zuccarini, Dox, Mariën, Verlinden, Heinecke, Prislan, Marie, Lange, Van den Bulcke, Penuelas, Fonti and Campioli2025). Radial sections, as a complement to the transverse sections, could help differentiate the xylogenesis phase in autumn and winter. Therefore, we emphasize the importance of recording phenophases by cell type in coarse roots (Supplementary Figure 2).

Future studies should aim to adopt a whole-tree approach, synchronously assessing xylogenesis in stem, branches and especially coarse roots. A holistic understanding of organ-specific wood formation is essential to quantify total tree wood production and carbon sequestration, improving our grasp of internal allocation strategies.

5.3. Towards a global synthesis of angiosperm xylogenesis

Most angiosperm xylogenesis studies are concentrated in temperate and Mediterranean European forests, leaving major biomes, especially tropical, arid, boreal and southern hemispheric systems, understudied. Recent work from Asia, Africa, South America and Australia reveals substantial variability in phenophase timing and duration across species and environments, highlighting the role of local adaptation (Hicter et al., Reference Hicter, Beeckman, Luse Belanganayi, De Mil, Van den Bulcke, Kitin, Bauters, Lievens, Musepena, Mbifo Ndiapo, Luambua, Laurent, Angoboy Ilondea and Hubau2025; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Fan, Lin, Kaewmano, Wei, Fu, Grießinger and Bräuning2024; Marcati et al., Reference Marcati, Machado, Podadera, Lara, Bosio and Wiedenhoeft2016; Mendivelso et al., Reference Mendivelso, Camarero, Gutiérrez and Castaño-Naranjo2016; Nikerova et al., Reference Nikerova, Galibina, Moshchenskaya, Tarelkina, Borodina, Sofronova, Semenova, Ivanova and Novitskaya2022; Pompa-García et al., Reference Pompa-García, Camarero and Colangelo2023; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Fu, Yan, Bräuning and Fan2025; Zweifel et al., Reference Zweifel, Drew, Schweingruber and Downes2014).

Expanding monitoring to diverse ecosystems is crucial for building a comprehensive picture of angiosperm wood formation. While gymnosperms have benefited from decades of coordinated global research (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Silvestro, Liang, Mencuccini, Camarero, Rathgeber, Sylvain, Nabais, Giovannelli, Saracino, Saulino, Guerrieri, Gričar, Prislan, Peters, Čufar, Yang, Antonucci, Babushkina and Rossi2025; Silvestro et al., Reference Silvestro, Mencuccini, García-Valdés, Antonucci, Arzac, Biondi, Buttò, Camarero, Campelo, Cochard, Čufar, Cuny, de Luis, Deslauriers, Drolet, Fonti, Fonti, Giovannelli, Gričar and Rossi2024), a comparable synthesis for angiosperms is still lacking. This imbalance limits our ability to generalize findings, build inclusive datasets and develop reliable forest models. A globally representative xylogenesis database for angiosperms is urgently needed to improve predictions of forest productivity and reduce bias in carbon cycle projections.

5.4. Integrating xylogenesis and quantitative wood anatomy

Combining xylogenesis with quantitative wood anatomy offers a powerful and promising avenue to calculate daily rates of cell enlargement and wall thickening, as recently demonstrated for gymnosperms (Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Rathgeber, Frank, Fonti and Fournier2014, Reference Cuny, Fonti, Rathgeber, von Arx, Peters and Frank2019; Martínez-Sancho et al., Reference Martínez-Sancho, Treydte, Lehmann, Rigling and Fonti2022). Extending this approach to angiosperms would allow us to capture the dynamics of the kinetics of wood formation with greater precision (daily or weekly scale) (Buttò et al., Reference Buttò, Peltier and Rademacher2025). It would also be possible to investigate potential compensation mechanisms in angiosperm cell differentiation under temperature or water limitation (which was found already for conifers Cuny et al., Reference Cuny, Fonti, Rathgeber, von Arx, Peters and Frank2019; Larysch et al., Reference Larysch, Stangler, Puhlmann, Rathgeber, Seifert and Kahle2022; Vieira et al., Reference Vieira, Carvalho and Campelo2020) or even other drivers of intra-annual wood formation and carbon sequestration (Andrianantenaina et al., Reference Andrianantenaina, Rathgeber, Pérez-de-Lis, Cuny and Ruelle2019). Therefore, to achieve it, area or cell-type based measurement of xylogenesis should be developed to account for the temporal variability of the development of vessels, fibres and parenchyma (Keret et al., Reference Keret, Schliephack, Stangler, Seifert, Kahle, Drew and Hills2024; Noyer et al., Reference Noyer, Stojanovic, Horácek and Pérez-de-Lis2023). This integrated framework would greatly enhance our capacity to identify the environmental and physiological drivers of wood formation and to quantify their imprints on wood anatomy.

6. Conclusion

These recommendations provide a structured framework for studying xylogenesis in angiosperm trees, aiming to improve consistency in anatomical observations, measurement, phenophase definitions and analysis across cell types, wood types and tree organs. They represent an important step toward generating more comparable and comprehensive datasets, which are essential for advancing both fundamental and applied research. However, key challenges remain. These include the need to better characterize cell-type-specific differentiation dynamics, expand geographic and ecological coverage beyond currently well-studied regions, extend xylogenesis monitoring to branches and roots and implement kinetic analysis to investigate the intra-annual effect of climate on xylogenesis. Addressing these gaps will require methodological refinement and stronger integration of wood formation studies with ecological modelling. Ultimately, these efforts will support a more holistic understanding of how angiosperm trees grow, function and respond to environmental change, providing critical insights for predicting forest dynamics, carbon cycling and ecosystem resilience under future climates.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/qpb.2026.10039.

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the FAIRWood project.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Pictures supporting this research will be made available on request.

Author contributions

LJM and PP conceived and developed the study. All authors contributed to the text and discussion.

Funding statement

This work is part of the FAIRWood project funded by the CESAB of the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB). This work was also supported by Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO, grant number 49572) and the Slovenian Research Agency (ARIS) through research core funding (P4-0430) and projects J4-2541, J4-4541 and J4-50130.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/qpb.2026.10039.

Comments

Dear editors,

We are pleased to submit our manuscript for the special collection 'Advances in xylem and phloem formation research’ titled “Recommendations for assessing xylogenesis in angiosperm trees” authored by Lorène J. Marchand, Peter Prislan, Jožica Gričar, Cristina Nabais, Elena Larysch, Roberto Silvestro, Omar Flores, Cyrille B. K. Rathgeber and Patrick Fonti to Quantitative Plant Biology.

While significant progress has been made in gymnosperms, leading to the establishment of a unique large-scale database and state-of-the-art studies, a comparable synthesis for angiosperms remains lacking. This imbalance limits our ability to generalize findings, build inclusive datasets, and develop robust forest growth and carbon cycle models.

Our manuscript addresses this gap by providing a conceptual and methodological framework for assessing wood formation in angiosperms. Rather than providing a detailed implementation protocol, we aim to highlight key challenges, species-specific peculiarities, and methodological considerations essential for harmonizing xylogenesis studies across different contexts. The recommendations consider variation in wood type (ring-porous and diffuse-porous), cell type (vessels, fibers and parenchyma), and organ (stem, branch, and coarse root), and are supplemented by a comprehensive set of annotated micrographs to aid in the identification of xylem differentiation stages.

In the second part, we outline future research priorities toward the development of a globally representative xylogenesis database for angiosperms, with the goal of supporting climate modeling, enhancing forest productivity forecasts, and reducing biases in carbon cycle projections.

We believe that our contribution is timely, relevant to the focus of the special collection, and will be of interest to a broad audience working on wood formation, forest ecology, and global change biology. We thank you for considering our manuscript and are happy to respond to any questions or reviewer comments.

Yours sincerely,

Lorène J. Marchand, Peter Prislan and co-authors