Introduction

Each year, more than one in ten of the world's babies are born preterm, and this number is rising. The first choice for feeding these infants is human milk (HM) from their mother. HM is recognized as the best option for providing complete nutrition for infants, especially premature ones, in the first 6 months of their lives. Besides nutrients, HM contains bioactive components such as growth factors, hormones, enzymes, immune factors, antimicrobial and antioxidant substances, and microorganisms that help in the digestion and absorption of nutritive substances. If, for any reason, this is not possible, donor HM obtained from a human milk bank (HMB) is the best alternative (World Health Organization (WHO), 2011; Borges et al., Reference Borges, Oliveira, Hattori and Abdallah2017; Boquien, Reference Boquien2018). HMBs are responsible for the collection, pasteurization, storage, quality control and distribution of HM from donors for premature and hospitalized infants in need.

The distributed HM must fulfil quality standards, especially if it is intended for preterm infants whose immature immune systems are inefficient at fighting off the bacteria and viruses. To provide microbial safety, HM must be pasteurized. In HMBs, low-temperature long-time (LTLT) pasteurization, so-called holder pasteurization (HoP) (62.5°C, 30 min) is used most often. Such conditions ensure microbiological safety but cause the degradation of numerous bioactive components of milk (Piemontese et al., Reference Piemontese, Mallardi, Liotto, Tabasso, Menis, Perrone, Roggero and Mosca2019). Therefore, there is a need to develop alternative preservation techniques that reduce HM quality degradation while ensuring microbiological safety. Satisfactory results have been obtained using high pressure without heating (Wesolowska et al., Reference Wesolowska, Sinkiewicz-Darol, Barbarska, Strom, Rutkowska, Karzel, Rosiak, Oledzka, Orczyk-Pawilowicz, Rzoska and Borszewska-Kornacka2018), microwave heating in controlled temperatures and times (Malinowska-Pańczyk et al., Reference Malinowska-Pańczyk, Królik, Skorupska, Puta, Martysiak-Żurowska and Kiełbratowska2019) and high-temperature short-time (HTST) pasteurization (Escuder-Vieco et al., Reference Escuder-Vieco, Espinosa-Martos, Rodríguez, Corzo, Montilla, Siegfried, Pallás-Alonso and Fernández2018a).

The HTST pasteurization method is based on using a high temperature (72.5°C) for a short time (5–15 s). The HTST pasteurization, a well-established heat treatment in the dairy industry, has been proposed for the treatment of HM. This method is, at least, equivalent to HoP in terms of ensuring milk microbiological safety (Terpstra et al., Reference Terpstra, Rechtman, Lee, Van Hoeij, Berg, Van Engelenberg and Van't Wout2007; Goelz et al., Reference Goelz, Hihn, Hamprecht, Dietz, Jahn, Poets and Elmlinger2009; Giribaldi et al., Reference Giribaldi, Coscia, Peila, Antoniazzi, Lamberti, Ortoffi, Moro, Bertino, Civera and Cavallarin2016; Escuder-Vieco et al., Reference Escuder-Vieco, Espinosa-Martos, Rodríguez, Corzo, Montilla, Siegfried, Pallás-Alonso and Fernández2018a; Perrin et al., Reference Perrin, Festival, Starks, Mondeaux, Brownell and Vickers2019) while it is better at preserving the functionality of its biologically active components (Goelz et al., Reference Goelz, Hihn, Hamprecht, Dietz, Jahn, Poets and Elmlinger2009; Baro et al., Reference Baro, Giribaldi, Arslanoglu, Giuffrida, Dellavalle, Conti, Tonetto, Biasini, Coscia, Fabris, Moro, Cavallarin and Bertino2011; Giribaldi et al., Reference Giribaldi, Coscia, Peila, Antoniazzi, Lamberti, Ortoffi, Moro, Bertino, Civera and Cavallarin2016; Escuder-Vieco et al., Reference Escuder-Vieco, Espinosa-Martos, Rodríguez, Fernández and Pallás-Alonso2018b).

Standard HTST is usually carried out in flow pasteurizers that employ mechanisms of convective heat transfer obtained from steam or hot water. For HTST pasteurization of HM, a medium-scale continuous-flow pasteurizer has been successfully used (Giribaldi et al., Reference Giribaldi, Coscia, Peila, Antoniazzi, Lamberti, Ortoffi, Moro, Bertino, Civera and Cavallarin2016; Escuder-Vieco et al., Reference Escuder-Vieco, Espinosa-Martos, Rodríguez, Corzo, Montilla, Siegfried, Pallás-Alonso and Fernández2018a). Whereas, to pasteurize small volumes of HM, simulated flash-heat pasteurization (FH, heating the milk to 73°C and rapid cooling down to 25°C) monitored by FoneAstra was used (Chaudhri et al., Reference Chaudhri, Vlachos, Kaza, Palludan, Bilbao, Martin, Borriello, Kolko and Israel-Ballard2011).

The microwave-assisted heat treatment results from the conversion of electromagnetic field energy into thermal energy through the increased rotation of water and ions molecules when exposed to microwaves. Since the microwave field allows achieving a high temperature of substances containing water in a very short time, it can be used to perform HTST pasteurization for food products (Xanthakis et al., Reference Xanthakis, Gogou, Taoukis and Ahrné2018), whole cow’s milk (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Wang, Sun, Han, Yin, Pei, Liu, Pang, Huang and Chen2024) and HM (Leite et al., Reference Leite, Migotto, Landgraf, Quintal, Gut and Tadini2019).

This study presents the effects of microwave HTST pasteurization (MHTST; 72°C, 15 s) on HM components in comparison with convection HTST pasteurization (CHTST) under identical heating/cooling profiles. The study aimed to check whether the use of microwave heating to HTST pasteurization affects the constituents of HM differently than convection heating.

Several components representing the complexities of HM were selected as indicators of milk quality. The nutritional quality of HM was detected based on the macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein and lipids), total energy, fatty acid (FA) profile and content of malondialdehyde (MDA) as a marker of lipid oxidation. Lysozyme (LZ) activity, lactoferrin (LF) and vitamin C contents as components supporting the immune system and α-amylase activity one of the digestive enzymes present in HM were determined. The antioxidant quality of milk was assessed by total antioxidant capacity (TAC) tests and vitamin C content. Due to their sensitivity to high temperatures, vitamin C and LF also served as markers of heat treatment.

Materials and methods

Collection of milk sample

HM samples from five healthy, lactating mothers of full-term infants were collected between 21 and 30 days of lactation from volunteers in cooperation with the Department of Obstetrics of the Clinical Hospital in Gdańsk, Poland. Mothers collected milk using an electric breast pump (Symphony, Medela, Polska Sp. z o. o., Warsaw, Poland) at home between 7.00 and 10.00 into sterile bottles and then stored it in a refrigerator at about 5°C for a maximum of 6 h. After delivery to the laboratory, all HM were pooled to obtain an average, representative sample of the milk, divided into 50-mL samples and frozen at –80°C until further thawing, processing and analysis. The donors gave written consent to participate in the study, and all the experimental procedures were approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Gdansk (NKEBN/97/210).

Microwave HTST

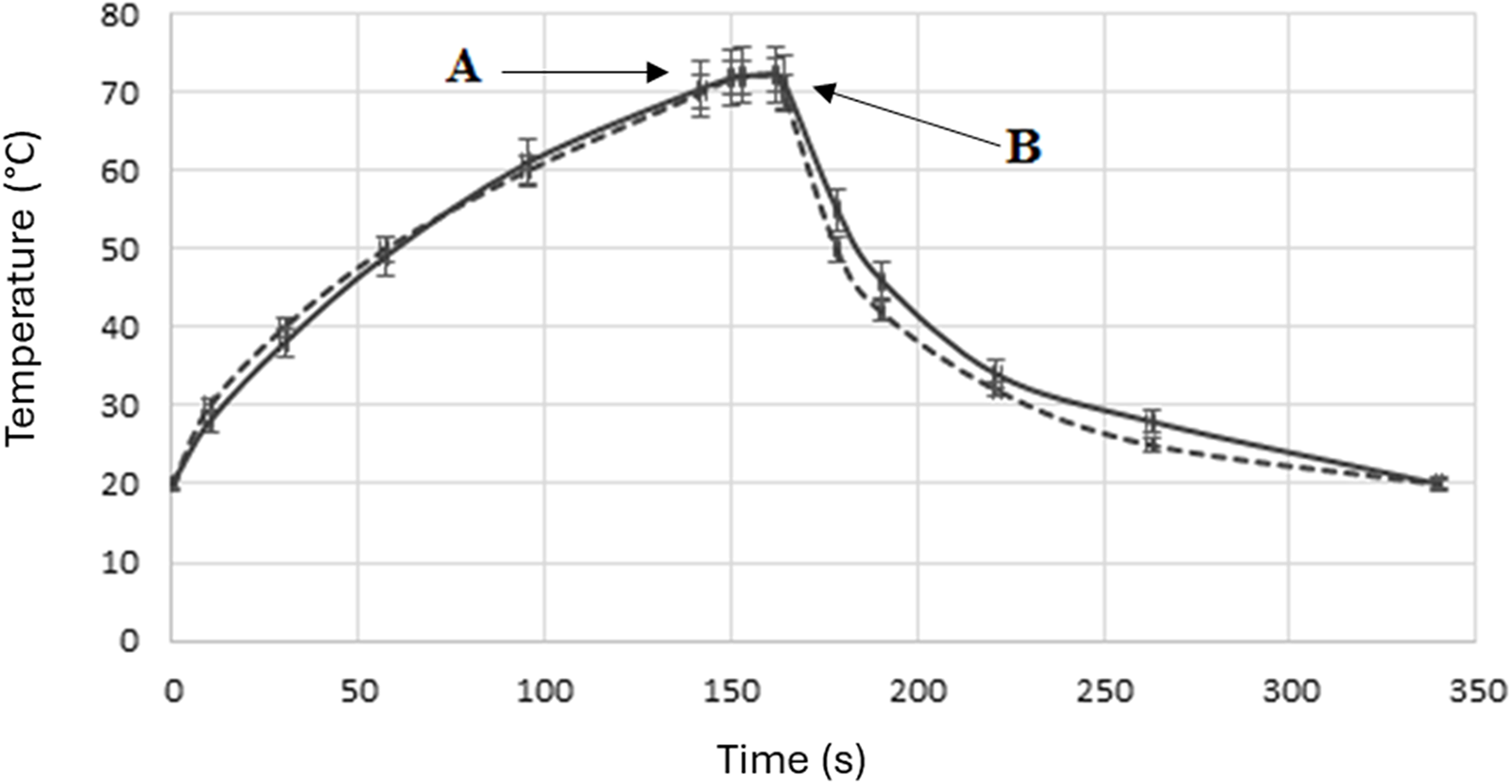

As described in a previous publication (Martysiak-Żurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Puta and Kiełbratowska2019), MHTST was conducted using a prototype microwave flow pasteurizer designed for pasteurization of the liquids at a programmed temperature for a certain period of time and cooling after treatments (2450 MHz, 800 W, EnbioTechnology Co., Kosakowo, Poland). Milk samples (50 mL) were thawed and heated to 20°C, transferred into 100-mL screw-cap laboratory bottles (DURAN®) and placed in a pasteurizer. There were silicone tubes in the sample, through which the milk was pumped through the temperature sensor back into the bottle. This pumping and stirring of milk in a closed circuit ensured a uniform temperature of the liquid and rapid cooling after the process in a heat exchanger with the use of tap water. Milk samples were heated for 150 s until reaching 72°C, and then they were kept at this temperature for 15 s. After that, the cooling stage to ambient temperature was conducted in ice for about 100 s (Fig. 1). All treatments were performed in three replicates for each of the measured variables.

Figure 1. Temperature curve of human milk pasteurization at 72°C for 15 s: microwave heating (dashed line) and convective heating (solid line). (A) Time of reaching the preset temperature, (B) The beginning of sample cooling after heating.

Convective HTST

HTST and MHTST pasteurization were carried out under the same time–temperature conditions (Fig. 1). Each thawed and heated to 20°C milk sample (50 mL) was transferred to a 100-mL screw-cap laboratory bottle (DURAN®) equipped with a thermometer and placed in a 98°C shaking water bath. The temperature changes were monitored, and after reaching 72°C, samples were transferred into a shaking water bath set at 72°C. The pasteurization process was conducted at this temperature for 15 s. After this time, milk samples were cooled on ice to ambient temperature, which took about 100 s. The CHTST was performed in three replications for each of the measured components variables.

Determination of essential macronutrients

HM macronutrients were analysed using the Human Milk Analyzer MIRIS (Miris AB, Uppsala, Sweden) based on semi-solid mid-infrared (MIR) transmission spectroscopy. Concentrations of macronutrients (fat, carbohydrates and protein – total and true) were reported in g/100 mL and energy in kcal/100 mL of HM. Each sample was heated to 40°C in a thermostatic bath and then homogenized using a MIRIS Sonicator (1.5 s/mL) before analysis in triplicate.

Analysis of FA composition

The analysis of HM FA was preceded by extraction of lipids from HM by the Röse–Gottlieb method (EN: ISO 1211:2011). The FAs were derivatized into fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) using the methanolic boron trifluoride (BF3, 14%) reagent (EN: ISO 5509:2000). FAME were separated by high-performance gas chromatography (HP-GC) (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with a flame ionization detector (FID) and Rtx 2330 column (100 m × 0.25 mm, Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Identification of FAME was carried out in comparison to the FAME standard profile (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The results were expressed as the percentage of the individual FAs in the total mass of FAs.

Determination of MDA content

The method used to determine the amount of MDA in HM after pasteurization was described in detail in literature (Martysiak-Żurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Malinowska-Pańczyk, Orzołek, Kusznierewicz and Kiełbratowska2022a). The process involves forming a coloured complex of MDA and thiobarbituric acid, which is analysed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and detected at wavelength 534 nm on the VIS detector. The chromatographic equipment consisted of PerkinElmer Liquid Chromatograph, ZORBAX SB-C18 (4.0 × 250 mm) column and UV-VIS detector (PerkinElmer). The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and acetonitrile (ACN) in 85:15 (v:v) ratio with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. Quantification was performed using a calibration curve made from MDA standards.

Determination of TAC

TEAC assay

The antioxidant capacity of HM was measured by using a modified procedure of Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) described in literature (Martysiak-Żurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Malinowska-Pańczyk, Orzołek, Kiełbratowska and Sinkiewicz-Darol2022b). The sample of HM (0.02 mL) was mixed with 2 mL of the ABTS• + (radical cation 2,2ʹ-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-acid)) working solution (A = 0.7 ± 0.005 at 734 nm), held for 10 min at ambient temperature and centrifuged for 5 min at 700 × g. The absorbance of a supernatant was measured at 734 nm. As a standard, the solutions of Trolox (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) were used. The value of TEAC was expressed in mM of Trolox equivalents (TE) per L of HM.

ORAC-FL assay

The TAC of HM was also measured using the oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay with fluorescein (ORAC-FL) method. Milk samples were diluted 300 times with a 75 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Next, 25 µL of diluted HM was mixed with 150 µL 4 nM fluorescein (FL) solution and 25 µL 153 mM 2,2ʹ-azobis(2-aminopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH) solution. Fluorescence was measured every 60 s for 1 h at the absorbance wavelength of 485/20 nm and emission at 528/20 nm. The analysis was performed with a microplate reader (Synergy HT, BIOKOM, Janki k /Warszawy, Poland). The ORAC-FL values were expressed in mM TE/L of HM.

Determination of vitamin C

The amount of vitamin C in HM was measured using optimized reverse-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) with the UV/VIS detection method as previously described (Martysiak-Żurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Malinowska-Pańczyk, Orzołek, Kiełbratowska and Sinkiewicz-Darol2022b). Dehydroxyascorbic acid was reduced into ascorbic acid (AsA) by dithiothreitol. The samples were analysed by RP-HPLC equipped with C-18 column (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) (125 × 4.0 mm I.D., 5 µm particle size) at UV detection at 265 nm. The temperature of column was 25°C and the injection volume was 25 μL. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% acetic acid and methanol (95:5 v:v). The content of vitamin C (mg AsA/100 ml) was calculated using the equation of calibration curve, the dependence of the area of the generated peaks on the AsA content in the standard solutions.

Determination of LF

The content of LF in HM was determined by using the RP-HPLC/UV-VIS method described by Dračková et al. (Reference Dračková, Borkovcová, Janštová, Naiserová, Přldalová, Navrátilová and Vorlová2009). HM samples were stirred thoroughly with 1 M HCl to pH 4.6 and 1.0 mL of sample centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C at 10 000 × g to remove fat and whey. The supernatant containing LF in native form was diluted six times with distilled water and injected into the Kinetex C18 column (4.0 × 150 mm, 5 µm, 100A, Phenomenex) equipped with SB-C18 precolumn (4.6 × 12 mm) and detected at 210 nm wavelength. Mobile phases consisted of A: 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and B: 0.1 % TFA in ACN. The analysis was carried out in the following pattern: 0–2 min 65:35 A:B (v:v), 2–15 min 50:50 A:B, (v:v) and 15–20 min 65:35 A:B (v:v) and flow rate 0.8 mL/min. The amount of LF in HM was calculated using the calibration curve obtained from the analysis of LF standards.

Determination of LZ activity

The LZ activity in HM was determined using a Micrococcus lysodeikticus-based turbidimetric method (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Santos, Fidalgo, Delgadillo and Saraiva2014). The activity was measured by readings of the change in turbidity of the bacterial suspension at 450 nm for 10 min at 1 min intervals, using a spectrophotometer. Each sample was measured in triplicate. Activity unit of LZ was defined as the amount of enzyme that produces a ΔA450 nm/min of 0.001/min, at pH 6.3 at 30°C using a suspension of Micrococcus lysodeikticus as substrate.

Determination of α-amylase activity

The α-amylase (α-A) activity in HM was determined using the α-A activity assay according to the INFOGEST protocol (Brodkorb et al., Reference Brodkorb, Egger, Alminger, Alvito, Assunção, Ballance, Bohn, Bourlieu-Lacanal, Boutrou, Carrière and Clemente2019) and methodology presented by Eivazzadeh-Keihan et al. (Reference Eivazzadeh-Keihan, Dogari, Ahmadpour, Aliabadi, Radinekiyan, Maleki, Fard, Tahmasebi, Mojdehi and Mahdavi2021). The HM sample was stirred with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 6.9 solution (1:19, v:v) and centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C at 2 000 × g. Next, 0.5 mL of HM sample supernatant was mixed with 0.5 mL substrate: 1.0 % soluble potato starch in PBS pH 6.9 (wt/vol) and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding a colour reagent (96 mM 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid in 5.3 M sodium potassium tartrate), and boiled for exactly 10 min at 100°C. After making up to 10 mL of H2O and cooling on ice, the absorbance at 540 nm was measured. The activity of α-A was calculated against a curve of the maltose standard in the range of 1 to 15.0 mM maltose/L of PBS. Activity of α-A unit was defined as activity that releases 1.0 μM of maltose equivalent from starch in 1 min at pH 6.9 and 37°C.

Statistical analysis

The mean values and standard deviations of all the data are presented in Table 1. Each sample was analysed in triplicate. The SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat Software, Inc., CA) was used to conduct statistical analysis of the results. Differences in concentration or activity of the compounds between raw and HTST-treated HM samples were analysed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. Differences between means were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

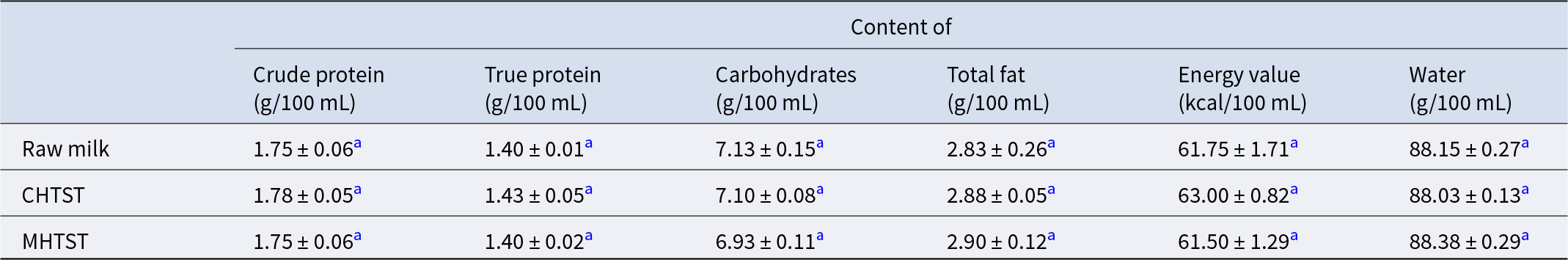

Table 1. Concentration of macronutrient and energy content in pooled human milk: raw (control) and pasteurized by HTST using microwave (MHTST) and conventional (CHTST) heating

Each value is expressed as mean ± SD.

a,b Means value within a column with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Results and discussion

HTST is one of the pasteurization methods successfully used to ensure HM microbiological safety, both in a flow system (Terpstra et al., Reference Terpstra, Rechtman, Lee, Van Hoeij, Berg, Van Engelenberg and Van't Wout2007; Goelz et al., Reference Goelz, Hihn, Hamprecht, Dietz, Jahn, Poets and Elmlinger2009; Escuder-Vieco et al., Reference Escuder-Vieco, Espinosa-Martos, Rodríguez, Corzo, Montilla, Siegfried, Pallás-Alonso and Fernández2018a) and in a static system (Mayayo et al., Reference Mayayo, Montserrat, Ramos, Martínez-Lorenzo, Calvo, Sánchez and Pérez2016; Klotz et al., Reference Klotz, Joellenbeck, Winkler, Kunze, Huzly and Hentschel2017; Manzardo et al., Reference Manzardo, Toll, Müller, Nickel, Jonas, Baumgartner, Wenzel and Klotz2022). One way to quickly heat a liquid, in addition, to its entire volume, is to use microwaves, although microwave heating is still often seen by society as a method that causes greater degradation of food compounds than other forms of heating. However, it is now believed that in polar liquids, microwave non-thermal effects are almost certainly nonexistent. Nonetheless, the possibility should be considered that different methods of heat transfer than ‘conventional’ heating may cause an accelerated effect on cell membranes and protein structures. Khalil and Villota (Reference Khalil and Villota1989) concluded that microwave-heated cells of Staphylococcus aureus suffered a larger injury as well as greater membrane damage than during conventional heating. In previous studies, we have shown that microwave pasteurization conducted under strictly programmed time and temperature conditions ensures the microbiological safety of HM similarly to HoP while better preserving some active components (Martysiak-Żurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Malinowska-Pańczyk, Orzołek, Kusznierewicz and Kiełbratowska2022a, Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Malinowska-Pańczyk, Orzołek, Kiełbratowska and Sinkiewicz-Darol2022b). The Gram-negative bacteria E. coli and P. aeruginosa, and the Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus and S. epidermidis have been completely inactivated already by the time a temperature of 70°C has been attained (the average time to reach the set temperature was 180 s) (Malinowska-Pańczyk et al., Reference Malinowska-Pańczyk, Królik, Skorupska, Puta, Martysiak-Żurowska and Kiełbratowska2019). So, in the present studies, we compared the effect of HM pasteurization with the HTST technique using different methods of generating the high temperatures, both microwave and conduction, but with the same time-temperature conditions (Fig. 1).

Macronutrients and energy content

In principle, the methods used to pasteurize HM (HoP, CHTST, MLTLT pasteurization) do not affect the nutrients in HM (Nebbia et al., Reference Nebbia, Giribaldi, Cavallarin, Bertino, Coscia, Briard-Bion, Ossemond, Henry, Ménard, Dupont and Deglaire2020) or bovine milk (Dehghan et al., Reference Dehghan, Jamalian, Farahnaky, Mesbahi and Moosavi-Nasab2012). But some studies have shown the influence of HTST (conducted convectively) on macronutrient composition, FA profile and lactose content of HM (Escuder-Vieco et al., Reference Escuder-Vieco, Rodríguez, Espinosa-Martos, Corzo, Montilla, García-Serrano, Calvo, Fontecha, Serrano, Fernández and Pallás-Alonso2021). Moreover, so far no one has tested the effect of MHTST on HM. For this reason, we undertook to check the effect of MHTST on the basic nutrients of milk and the FA profiles. The obtained results showing the level of measuring components in raw and pasteurized HM are summarized in Table 1. In the tested samples of pooled raw HM, the total protein content was 1.75 g/100 mL, carbohydrates were 7.13 g/100 mL, fat 2.83 g/100 mL and energy value 61.75 kcal/100 mL. The method of heating had no significant effect on the macronutrients contained in the milk. The largest differences, although not statistically significant, occurred between the carbohydrates content in raw and MHTST milk and the water content and energy value between CHTST and MHTST milk (p = 0.073, p = 0.097 and p = 0.067, respectively).

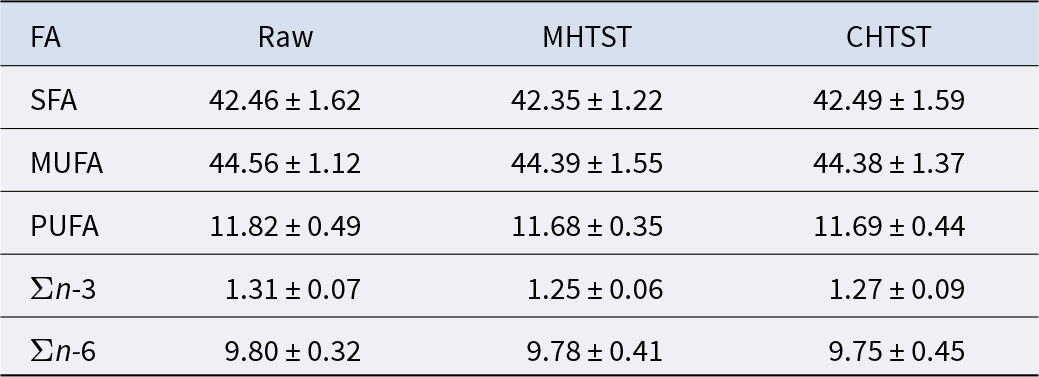

FA profile of HM

The lipids extracted from the samples contained more than 50 FA, with a composition profile characteristic of HM (Supplementary Table). In the PUFAs group, the n-6 FA families were found at the level of about 10% of the total FA content, and the n-3 FA at about 1.3% (Table 2). FA content was not significantly affected by either of the pasteurization methods used in the study. To our knowledge, this is the first study about the influences of MHTST and HTST on the FA profiles of HM. Rodríguez-Alcalá et al. (Reference Rodríguez-Alcalá, Alonso and Fontecha2014) conducted similar HTST (85°C, 15 s) and MHTST (650 W, 90 s) experiments on bovine milk. They observed that after processing, the majority of FA remained stable, and only total CLA content increased. Dehghan et al. (Reference Dehghan, Jamalian, Farahnaky, Mesbahi and Moosavi-Nasab2012) also examined cow’s milk FA profile changes after HTST and MHTST pasteurization (85°C, 15 s) and concluded that the treatment had an effect only on oleic (18:1, 9c) and elaidic (18:1, 9t) acids. Our previous studies provided evidence that HM pasteurization by using microwave MWH at 62.5, 66 and 70°C for 10 min does not change its FA concentration (Martysiak-Żurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Malinowska-Pańczyk, Orzołek, Kusznierewicz and Kiełbratowska2022a).

Table 2. Fatty acid content in raw (control) and pasteurized HM by MHTST and CHTST (mean % of FA in total FA ± SD)

MDA content

HM contains long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), which have an important role in the growth, intestinal repair and development of the visual-cognitive function of a newborn’s brain (Gil, Reference Gil2003). LCPUFAs, because of their structure, are easily oxidized, especially at elevated temperatures, thereby losing their unique biological properties. Therefore, it is necessary to find out if the applied pasteurization technique caused the lipid oxidation. The primary products of lipid oxidation, lipid peroxides, are unstable and quickly transformed into secondary products in the oxidation process. One of the more stable, final secondary products of lipid oxidation is MDA, which is often used as a marker for the extent of lipid oxidative processes. The difference between the levels of MDA in raw milk and pasteurized HTST was not statistically significant. Similarly, Silvestre et al. (Reference Silvestre, Miranda, Muriach, Almansa, Jareno and Romero2008) observed no significant difference in fresh HM after high pasteurization regarding the level of lipid oxidation products. A significant increase in the MDA level, indicating the degradation of FA by oxidation, was shown after microwave processing in camel milk (Alkaladi et al., Reference Alkaladi, Afifi and Kamal2014). The authors conducted microwave pasteurization for 10–50 s; however, the final temperature of HM and microwave power level were not noted, which may indicate that the processing temperature of these samples was too high.

TAC: ORAC-FL and TEAC tests

The results of ORAC-FL and TEAC show different values of antioxidant capacity for the same HM sample because each of the TAC tests works on specific antioxidants with a different mechanism of activity. ORAC-FL procedure is based on hydrogen atom transfer, whereas the TEAC assay uses single-electron transfer in the antioxidant capacity mechanism. Due to the compositional complexity of HM, greater values were obtained by ORAC-FL, because this method is specific not only for water-soluble antioxidants like vitamin C and E but also for phenolic compounds (Sánchez-Hernández et al., Reference Sánchez-Hernández, Esteban-Muñoz, Samaniego-Sánchez, Giménez-Martínez, Miralles and Olalla-Herrera2021).

In the present study, none of the HTST methods caused significant TAC level changes in HM (Fig. 2). Similarly, Silvestre et al. (Reference Silvestre, Miranda, Muriach, Almansa, Jareno and Romero2008) observed that after the HTST (75°C, 15 s), the TAC of HM did not change. The current literature shows ambiguous information about how HM preservation techniques influence the antioxidant capacity of HM, which is largely due to the lack of a standardized method for TAC determination in milk (Juncker et al., Reference Juncker, Ruhé, Burchell, van den Akker Chp, Korosi, van Goudoever Jb and van Keulen Bj2021). The data on the effects of microwave heating on HM antioxidant properties are rudimentary. Our previous study found that the TAC of HM, determined by TEAC and ORAC-FL assay, appeared to be insensitive to microwave pasteurization at 62.5°C (Martysiak-Żurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Żurowska, Malinowska-Pańczyk, Orzołek, Kiełbratowska and Sinkiewicz-Darol2022b).

Figure 2. Changes in mean concentration or activity of bioactive components in human milk after the high temperature short time (HTST, 72°C, 15 s) pasteurization by convection (CHTST) and microwave (MHTST), compared with raw human milk (RAW, 100% value). The data are presented as mean values with the standard deviation (±SD). Different lowercase letters (a, b, c) indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Vitamin C content

The average vitamin C content of European HM is reported to be about 50 mg/L, but the levels of vitamin C in the milk of individual women can vary considerably (Martysiak-Zurowska et al., Reference Martysiak-Zurowska, Zagierski, Wos-Wasilewska and Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz2016). In the presented study, the level of vitamin C was reported at approximately 43 mg/L. Due to the strong sensitivity of vitamin C to high temperatures, its degradation was observed in both HTST methods (raw HM vs MHTST p < 10−13; raw HM vs CHTST p < 10−14) . However, the decrease caused by MHTST was less severe than in HTST (by 42.6 and 50.2%, respectively; MHTST vs CHTST p = 0.0006). In the literature, it was reported that the decrease of AsA content was lower (by 16.6%) for the HTST (72°C, 16 s) method than in our research (Haddad and Loewenstein, Reference Haddad and Loewenstein1983). Several studies indicated that HoP of HM decreased vitamin C between 12% and 40% and AsA between 16% and 41% (Juncker et al., Reference Juncker, Ruhé, Burchell, van den Akker Chp, Korosi, van Goudoever Jb and van Keulen Bj2021). Even though the decrease in vitamin C level occurs after processing, it does not affect the TAC changes, which may indicate that other antioxidant compounds of HM are more thermally stable.

LF content

LF is a glycoprotein whose main roles are the regulation of the iron absorption and antibacterial, antiviral and antifungal activity (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Jenkins, Vargova, Bowler, Juszczak, King, Linsell, Murray, Partlett, Patel and Berrington2019). The measured level of LF in raw milk (1.89 mg/mL) coincides with values described for mature HM in the literature (Montagne et al., Reference Montagne, Trégoat, Cuillière, Béné and Faure2000). In the present study, MHTST caused an insignificant change in LF content (p < 0.05), whereas CHTST resulted in a 42% reduction (p < 10−12) in this protein content in comparison to raw HM (Fig. 2). Both pasteurization processes were designed so that the course of the time–temperature curve (heating and cooling) was identical. The only difference was the use of another process for transferring and distributing thermal energy in the liquid. The microwaves heated the entire volume of the milk in the flow at the same time. In convection pasteurization, thermal energy was transferred from the outside (in the first stage – from a water bath at 98°C) through the walls of the bottle to the centre, where the temperature was measured. The denaturation of LF was probably due to the heating of HM above 72°C near the inside walls of the bottle during HTST. Convection heating involves the transfer of heat from one place to another as a result of fluid movement, which promotes uneven temperature distribution in the liquid. Based on the iron-saturation levels, LF has been found to exist in three different forms: iron depleted apo-form, iron saturated holo-form and partially iron saturated mono-form (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Timilsena, Blanch and Adhikari2017). In breast milk, LF exists mainly in the apo-form, which denatures at about 70°C (holo-LF denatures at ∼90°C) (Baro et al., Reference Baro, Giribaldi, Arslanoglu, Giuffrida, Dellavalle, Conti, Tonetto, Biasini, Coscia, Fabris, Moro, Cavallarin and Bertino2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Timilsena, Blanch and Adhikari2017). Additionally, this protein is denatured significantly faster at temperatures above 72°C, so the overheating of the milk >72°C could have resulted in a greater degradation of LF (Sánchez et al., Reference Sánchez, Peiro, Castillo, Perez, Ena and Calvo1992). This study showed how important an element affecting HM quality is strict adherence to the temperature and time of the pasteurization process. Even a slight increase in temperature can result in a greater depletion of bioactive components in the HM. Klotz et al. (Reference Klotz, Joellenbeck, Winkler, Kunze, Huzly and Hentschel2017) noted a 68% and 80% decrease in the amount of LF after HTST (72°C, 5 s) and LTLT (63°C, 30 min) treatments, respectively. Another study reported 48% retention of LF after HTST (72°C, 15 s) (Kontopodi et al., Reference Kontopodi, Boeren, Stahl, van Goudoever Jb, van Elburg Rm and Hettinga2022). No such findings have been reported for MHTST yet. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to show the effect of microwave heating on LF levels in HM. Leite et al. (Reference Leite, Robinson, Salcedo, Ract, Quintal, Tadini and Barile2022) investigated the effect of so-called ‘microwave-assisted heating’ on bioactive and immunological compounds in HM and presented a 75.5% reduction of LF after 10 s of microwave heating at 70°C, but no significant change in the concentration of this protein after microwave heating at 60°C for 30 s. Other researchers using a similar technique (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Wang, Sun, Han, Yin, Pei, Liu, Pang, Huang and Chen2024) showed about a 45% decrease in LZ in cow milk microwave-assisted heating for 20 s at 90°C and more than 70% degradation of this protein in milk samples heated for 90 s at 95°C. This strongly suggests that the effect of microwave heating on the components of mammalian milk is still not precisely defined, and the biggest problem seems to be the lack of control over the microwave exposure time and the value of the temperature generated by the microwaves. The prototype microwave pasteurizer used in our work provides temperature and time control, giving confidence in our results. Considering the importance of LF, especially for premature infants, MHTST pasteurization is a better alternative than CHTST.

Lysozyme activity

The content of LZ in HM depends on the time of lactation and ranges from 0.37 g/L in colostrum to 0.89 g/L in mature milk (Montagne et al., Reference Montagne, Trégoat, Cuillière, Béné and Faure2000). The main benefit of this enzyme presence is an improvement of the immune system. The increasing level of LZ during lactation prevents the growth of bacteria that cause intestinal infections and diarrhoea, while facilitating the growth of beneficial microbiomes (Minami et al., Reference Minami, Odamaki, Hashikura, Abe and Xiao2016).

In this study, the LZ activity in raw, pooled HM was 21 898 ± 942 U/L which is characteristic of mature milk. No significant effect of the pasteurization methods on the activity of this protein was found. Giribaldi et al. (Reference Giribaldi, Coscia, Peila, Antoniazzi, Lamberti, Ortoffi, Moro, Bertino, Civera and Cavallarin2016) and Kontopodi et al. (Reference Kontopodi, Boeren, Stahl, van Goudoever Jb, van Elburg Rm and Hettinga2022) came up with the same conclusions for HTST (72°C, 15 s). However, Mayayo et al. (Reference Mayayo, Montserrat, Ramos, Martínez-Lorenzo, Calvo, Sánchez and Pérez2016) noted about a 20% higher activity of HM LZ after HTST. Other researchers observed an LZ activity drop by 44% (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Santos, Fidalgo, Delgadillo and Saraiva2014), or retained all as an effect of the HoP, and only retained 78.4% activity after using FH in which the HM is heating to a conservative 73°C and then cooling it as quickly as possible (Daniels et al., Reference Daniels, Schmidt, King, Israel-Ballard, Mansen and Coutsoudis2017).

α-Amylase activity

HM provides digestive enzymes (α-As and lipases) that compensate for the immaturity of a newborn’s digestive system and the absence of amylase during the neonatal period (Hamosh et al., Reference Hamosh, Henderson, Ellis, Mao and Hamosh1997). Unfortunately, data on the activity of this enzyme in HM are ambiguous, which are related to the use of several, non-standardized techniques for measuring α-A activity. In our study, the measurement method was based on the technique used in the INFOGEST protocol to check activity of α-A (Brodkorb et al., Reference Brodkorb, Egger, Alminger, Alvito, Assunção, Ballance, Bohn, Bourlieu-Lacanal, Boutrou, Carrière and Clemente2019). In raw HM, the α-amylase activity averaged 12 433 U/L. Both MHTST and CHTST pasteurization resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the activity of this enzyme, by about 6 and 7% respectively (Raw HM vs MHTST p = 0.046; Raw HM vs CHTST p = 0.030). There are no data in the literature regarding the effect of HM fixation techniques on this enzyme. The only study by Henderson et al. (Reference Henderson, Fay and Hamosh1998) presented the effect of HoP on this protein. It was shown that the α-A lost only about 15% of its initial activity as a result of heat treatment.

Conclusion

HTST pasteurization by both microwave and convection heating did not affect the level of HM macronutrients or the FA profile. PUFAs remained unchanged and did not undergo oxidative degradation, which was confirmed by determining the level of MDA. Despite the significant decrease in vitamin C content in both techniques, no changes in the antioxidant capacity of milk were observed after HTST pasteurization. The novelty of the present study lies in the demonstration that microwave-assisted HTST provides better retention of LF and vitamin C than CHTST. Due to the significance of LF for premature infants, MHTST pasteurization offers a better alternative compared to CHTST. It is also very important that no additional negative effects of microwave radiation on HM were observed. There were not any additional negative impacts of microwave radiation on HM. The presented research indicates that the use of microwave radiation under controlled conditions may be a promising method of generating high temperatures during the pasteurization of HM by HTST.

The use of CHTST pasteurization in the food industry requires the use of dedicated flow systems, in which milk is pasteurized by a continuous system of plate heat exchangers, usually adapted to significant volumes of pasteurized liquid. Therefore, it is not applicable in the case of donor HM in HMBs. Industrial HTST systems also require significant water and energy consumption and the disposal of cleaning agent residues. The use of microwave heating allows for a significant reduction of these inconveniences. However, more research is needed to confirm the safety of using microwaves for heating HM. Future studies should investigate the effect of MHTST on the preservation of other bioactive compounds, as well as conduct further studies to confirm the safety of using microwaves for heating HM.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022029925101362.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all mothers who agreed to donate human milk samples as part of this study.

Competing interests

None of the authors declared a conflict of interest.