Endometriosis is a common gynecological disorder that poses a serious health risk to millions of women around the world (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Horne, Gibson, Roberts and Saunders2024). Early diagnosis of endometriosis is crucial for effective treatment and management of the condition, as delayed treatment can lead to fertility issues and other complications (Salmeri et al., Reference Salmeri, Di Stefano, Viganò, Stratton, Somgliana and Vercellini2024). However, the varied symptomatology of endometriosis, combined with the gold standard for diagnosis being an invasive procedure such as laparoscopy, complicates the early detection of the condition (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Chapron, Giudice, Laufer, Leyland, Missmer, Singh and Taylor2019). The challenges of establishing pathologic symptoms from other conditions further delay the identification of the disease (Davenport et al., Reference Davenport, Smith and Green2023). In addition, patients with endometriosis cannot be cured and primarily rely on contraceptive therapy, with limited options for medication (Malvezzi et al., Reference Malvezzi, Marengo, Podgaec and Piccinato2020). Despite extensive research, the exact etiology of endometriosis remains unclear, with genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors suggested to play significant roles in its pathogenesis (Saunders & Horne, Reference Saunders and Horne2021). Among the various potential risk factors, natural hair color has garnered increasing attention in recent years as a hereditary trait that may influence the risk of developing endometriosis (Farland et al., Reference Farland, Degnan, Harris, Han, Cho, VoPham, Kvaskoff and Missmer2021).

Observational studies suggest a potential link between specific hair color and the risk of developing endometriosis (Flegr & Sýkorová, Reference Flegr and Sýkorová2019; Missmer et al., Reference Missmer, Spiegelman, Hankinson, Malspeis, Barbieri and Hunter2006; Salmeri et al., Reference Salmeri, Ottolina, Bartiromo, Schimberni, Dolci, Ferrari, Villanacci, Arena, Berlanda, Buggio, Di Cello, Fuggetta, Maneschi, Massarotti, Mattei, Perelli, Pino, Porpora, Raimondo and ¼ Candiani2022; Woodworth et al., Reference Woodworth, Singh, Yussman, Sanfilippo, Cook and Lincoln1995; Wyshak & Frisch, Reference Wyshak and Frisch2000). However, the cause-and-effect correlation between hair pigmentation and susceptibility to endometriosis has not been definitively established. Some research suggests that lighter hair colors (such as blonde and red) may be linked to a lower risk of endometriosis, while darker hair colors do not correlate significantly (Wyshak & Frisch, Reference Wyshak and Frisch2000; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Mortlock, MacGregor, Iles, Landi, Shi, Law and Montgomery2021). Moreover, Missmer et al. (Reference Missmer, Spiegelman, Hankinson, Malspeis, Barbieri and Hunter2006) found the relation between red hair color and endometriosis risk may differ by infertility status. However, it has also been reported that hair redness was not associated with endometriosis risk (Kvaskoff et al., Reference Kvaskoff, Han, Qureshi and Missmer2014). Therefore, the association between hair color and endometriosis risk is a complicated issue, and it is closely related to population characteristics. Most of these studies are based on observational data, which cannot establish a causal relationship between hair color and endometriosis. Observational studies frequently face challenges from confounding variables, potentially compromising the validity of their results (Warrington et al., Reference Warrington, Beaumont, Horikoshi, Day, Helgeland, Laurin, Bacelis, Peng, Hao, Feenstra, Wood, Mahajan, Tyrrell, Robertson, Rayner, Qiao, Moen, Vaudel, Marsit and ¼ Freathy2019). Consequently, while preliminary findings exist, the exact impact of natural hair color on the risk of endometriosis still needs to be further explored.

To address this knowledge gap, Mendelian randomization (MR) has been recognized as a potent method for inferring causal relationships. MR utilizes genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs), effectively eliminating confounding factors and reverse causation (Tschiderer et al., Reference Tschiderer, Bakker, Gill, Burgess, Willeit, Ruigrok and Peters2024). By analyzing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with natural hair color, MR studies can more accurately assess the causal relationship between hair color and the risk of endometriosis. The distinctive feature of this methodology is its grounding in Mendel’s principles of inheritance, wherein the stochastic distribution of alleles during meiosis mirrors the design of a randomized controlled trial, thereby establishing a solid framework for causal inference.

There have been some MR studies focusing on the association between hair color and various diseases, such as skin cancers, keratinocyte carcinoma, and Parkinson’s disease (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Li, Cho, Qureshi and Li2022; Flores-Torres et al., Reference Flores-Torres, Bjornevik, Zhang, Gao, Hung, Schwarzschild, Chen and Ascherio2024; Li, Wu, et al., Reference Li, Wu and Cao2023; S. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Jin, Xing and Wang2024; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Mortlock, MacGregor, Iles, Landi, Shi, Law and Montgomery2021; Yousaf et al., Reference Yousaf, Lee, Fang and Kolodney2021). Still, research specifically investigating the causal relationship between natural hair color and the risk of endometriosis remains scarce. Consequently, this study seeks to explore the potential causal links between natural hair color and endometriosis risk utilizing a two-sample MR analysis. By integrating large-scale genomic data with epidemiological information, we hope to clarify the potential influence of natural hair color on endometriosis risk, thus providing assistance in the prevention, early diagnosis, and even treatment of this disease. This study will help to understand the intricate relationships among genetic factors, phenotypic traits, and endometriosis risk.

Materials and Methods

Data for Natural Hair Colors

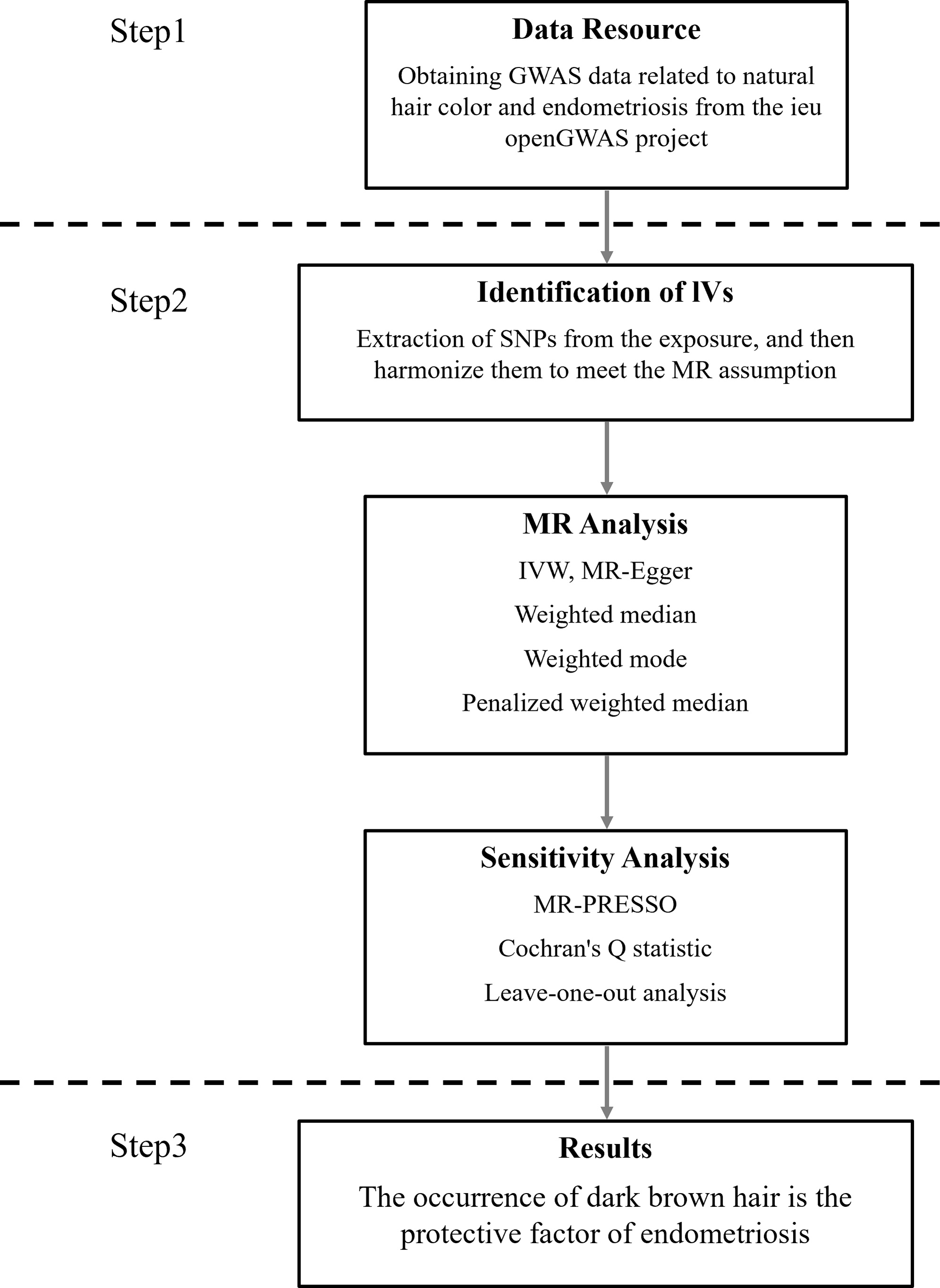

We delineate the methodology and design of our MR study, as illustrated in Figure 1. The exposure variables, encompassing five prevalent hair color categories (natural, pre-graying), are categorized as follows: blonde, red, light brown, dark brown, and black. The genetic variants employed in our analysis were sourced from a genomewide association study (GWAS) conducted by the UK Biobank Consortium (phenotype codes: 1747_1 to 1747_5). These genetic variants can be accessed via the second round of the Neale Lab’s GWAS, which encompasses a substantial cohort of 360,270 individuals with European ancestral roots. The UK Biobank, an expansive and forward-looking large-scale prospective cohort study, is resolutely committed to undertaking comprehensive and elaborate phenotyping evaluations throughout its diverse group of participants. (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). Approximately half a million individuals aged between 40 and 69 have enrolled in this study, contributing to an extensive and unprecedented repository of baseline data and biological samples collected up to 2010 (Sudlow et al., Reference Sudlow, Gallacher, Allen, Beral, Burton, Danesh, Downey, Elliott, Green, Landray, Liu, Matthews, Ong, Pell, Silman, Young, Sprosen, Peakman and Collins2015). This substantial cohort offers a unique opportunity to investigate various health-related factors and their implications over time, enhancing our understanding of the demographic’s health trends and outcomes.

Figure 1. Research framework and workflow.

In our investigation, the natural hair color data were derived from a dietary questionnaire, specifically inquiring about the participant’s ‘natural hair color’, with a note that the color before greying was considered for those with grey hair. The objective was to investigate the possible causal relationship between natural hair color and the incidence of endometriosis while disentangling this association from confounding influences such as the use of hair dye. Following the exclusion of statistical analyses and sensitivity analyses, we rigorously excluded SNPs that failed to meet the stringent criteria for IVs. This meticulous process culminated in the selection of a total of 428 SNPs that were deemed suitable and employed as instrumental variables for our analysis.

Data for Endometriosis

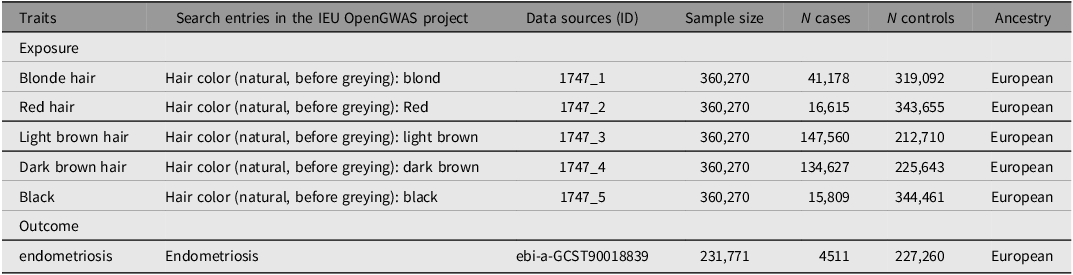

The GWAS data utilized in this study were exclusively sourced from the UK Biobank consortium, which provided summary-level correlation statistical data on endometriosis indicators, encompassing 4511 cases and 227,260 controls. For our analysis, we confined the cohort to female participants of European ancestry to reduce the risk of ancestry discrepancies. The SNPs associated with natural hair color and endometriosis were retrieved from OpenGWAS (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/; Elsworth et al., Reference Elsworth, Lyon, Alexander, Liu, Matthews, Hallett, Bates, Palmer, Haberland, Smith, Zheng, Haycock, Gaunt and Hemani2020). The details concerning the data about the exposure and outcome variables are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. GWAS data for natural hair color and endometriosis in Europe — IEU Open GWAS Project

MR Analysis

In the present investigation, the primary analytical approach employed was the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method with multiplicative random effects. In general, IVs used in MR need to meet three conditions: a strong correlation between IVs and exposure, no unmeasured confounding between IVs and outcome, and an exclusive effect of IVs on outcome only through the route of exposure (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Holmes and Davey Smith2018). When IVs meet these stipulated assumptions, the application of the IVW model with multiplicative random effects emerges as the most efficacious and precise technique. This technique, by consolidating data from numerous independent variables, notably amplifies statistical potency and accuracy and is widely embraced due to its straightforwardness and robustness against heterogeneity (J. Bowden et al., Reference Bowden, Del Greco, Minelli, Zhao, Lawlor, Sheehan, Thompson and Davey Smith2019). The MR Egger regression is a modified method of multi-instrumental variable MR based on aggregated data based on IVW. This method requires only the assumption that the pleiotropic effect of the IVs is independent of the association between the IVs and the exposure factor, as well as the assumption of no measurement error, which is less stringent than the core assumptions of the IVs. Its advantage is that it can detect pleiotropy and correct for pleiotropy bias, so it retains the validity of MR analysis (J. Bowden et al., Reference Bowden, Hemani and Davey Smith2018; Burgess & Thompson, Reference Burgess and Thompson2017). Weighted median and weighted mode represent more lenient models. Even if some SNPs fail to meet the IV assumption (such as pleiotropy), this method can still yield an unbiased estimate of the causal effect, provided that more than half of the SNPs are valid. It arrives at its conclusion by calculating the median of all SNP effect estimates and assigning greater weight to SNPs with higher reliability (J. Bowden et al., Reference Bowden, Davey Smith, Haycock and Burgess2016). The results from this approach validate the robustness of the effect estimates derived from the IVW model. The weighted mode method assesses the integration of the impact of different genotypes on a phenotype by computing the weighted average of each genotype (Hartwig et al., Reference Hartwig, Davey Smith and Bowden2017). BWMR, which employs Bayesian inference for MR, assesses the prior distribution of instrument variable effects to deliver a more robust causal effect estimate(Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Ming, Hu, Chen, Liu and Yang2020). This approach is especially effective in tackling potential horizontal pleiotropy and provides reliable results even when the effects of instrument variables are uneven.

Sensitivity Analyses

We implemented a series of sensitivity assessments in light of the potential introduction of pleiotropic and heterogeneity effects via study-specific exposures. The evaluations were conducted through a multifaceted approach, including the application of Cochran’s Q-test, the generation of funnel plots, the implementation of leave-one-out procedures, and the employment of the MR-Egger intercept test. Cochran’s Q-test served to identify the presence of significant heterogeneity, with a p value below .05 indicating the presence of detectable heterogeneity (S. J. Bowden et al., Reference Bowden, Kalliala, Veroniki, Arbyn, Mitra, Lathouras, Mirabello, Chadeau-Hyam, Paraskevaidis, Flanagan and Kyrgiou2019). Funnel plots were deployed to identify potential directional pleiotropy. We employed both the leave-one-out method and the MR-PRESSO (MR Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier) analysis to evaluate horizontal pleiotropy and derive statistically robust estimates. MR-PRESSO is grounded in a regression-based framework, where the slope of the regression line contributes to the exposure-outcome effect. The MR-PRESSO framework, comprising a global test, an outlier test and a distortion test, mainly reduces the effect of pleiotropy by weakening the third IV hypothesis. Specifically, the global test initially identifies pleiotropic SNPs. The detected SNPs are then removed by the outlier test. Following this, the IVW and the multiplicative random-effects mode are conducted to re-estimate the effect. Finally, the distortion test assesses whether there are differences in the effects post-treatment. This approach has been used previously to pinpoint outlier variants that warranted exclusion from IVs prior to MR analysis (Verbanck et al., Reference Verbanck, Chen, Neale and Do2018). All statistical analyses were conducted using the TwoSampleMR and MR-PRESSO packages within the R statistical software environment, version 4.3.3.

Results

IVs Information

As mentioned above, effective IVs must possess correlation, homogeneity, and no multicollinearity simultaneously. This rule was rigorously conducted in our MR analysis (Figure 1). Given the need for a strong correlation between IVs and exposure factors in the initial analysis, an exceptionally rigorous criterion was adopted, necessitating a p value below the threshold of 5 × 10^-8 to ascertain statistical significance. Meanwhile, the F value of these IVs exceeds 10, reflecting their strong statistical efficacy (Supplementary Table S1). SNPs with an F value less than 10 were excluded to mitigate the risk of residual bias. Considering the assumption of exclusivity in MR, SNPs demonstrating an association with outcomes at the stringent genomewide significance threshold of p < 5×10^-5 were not included in our analysis. After removing SNPs inconsistent with MR assumptions, the MR-PRESSO method was applied to exclude any underlying outliers iteratively. Ultimately, our selection criteria yielded a distinct set of SNPs for each category: 31,152 for red hair, 46 for blonde hair, 139 for light brown hair, 39 for dark brown hair, and 60 for black hair (Supplementary Table S2).

Hair Colors and Endometriosis

As illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3A-E, our analysis demonstrated that genetic predispositions for endometriosis were causally linked to specific hair color. Specifically, dark brown hair was linked to a reduced risk of endometriosis, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.844 (95% CI [0.725, 0.984], p < .05). In contrast, other hair colors, including dark, red, blonde, and light brown, did not correlate statistically significantly with endometriosis risk. The ORs for these hair colors were 0.568 (95% CI [0.280, 1.15], p = .117), 1.058 (95% CI [0.719, 1.558], p = .77), 1.158 (95% CI [0.886. 1.514], p = .28), and 1.306 (95% CI [0.978, 1.743], p = .07) respectively, indicating no discernible association with endometriosis. This observation suggested that genetic liability to dark brown hair was correlated with a decreased risk of endometriosis while genetic heterogeneity to dark hair color or lighter hair colors were not correlated with endometriosis risk. Similar outcomes were observed when employing MR-Egger, weighted median, and weighted mode estimator.

Figure 2. Causal estimates linking genetic hair color predictions to endometriosis risk. The forest plot elucidates the causal impact of hair color on endometriosis, as assessed through different MR methodologies, namely, SNP(single nucleotide polymorphism), IVW (inverse variance weighted), and MR (Mendelian randomization).

Figure 3. Scatter plot of MR estimates of genetic risk of hair color on endometriosis. (A) Blond hair group on endometriosis. (B) Red hair group on endometriosis. (C) Light brown hair group on endometriosis. (D) Dark brown hair on endometriosis. (E) Black hair on endometriosis.

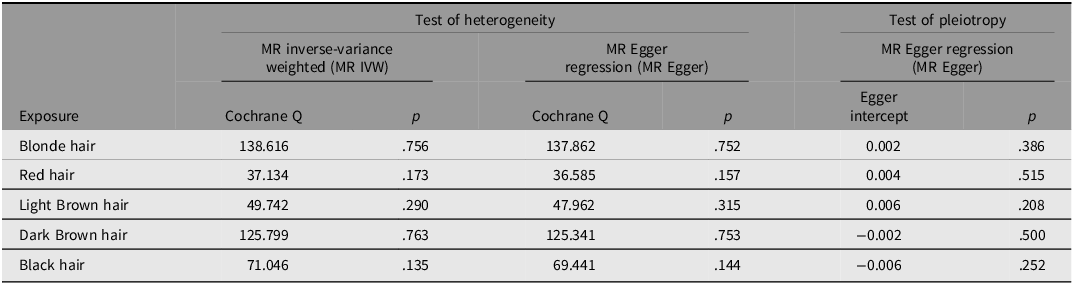

Results of Cochran’s Q test indicated no significant heterogeneity (Q_pval > 0.05), suggesting that the heterogeneity level did not exceed the statistical significance threshold in both MR Egger and IVW analyses (Cochran’s Q_pval was .75 and .76 respectively). This observation suggests that genetic variants acting as IVs may exert distinct influences on the relationship between hair color and endometriosis risk (Table 2). We also visualized the heterogeneity test results by funnel plots. As shown in Figure 4 A-E, the funnel plot of the symmetry distribution indicates that there is no directional horizontal pleiotropy, implying the lack of significant heterogeneity. Leave-one-out analysis confirmed that the exclusion of any single SNP did not disproportionately influence the causal estimates of hair color on endometriosis susceptibility, identifying the reliability of our results (Figure 5A-E). The forest plot results indicate that, after the removal of a single SNP, the remaining SNPs will not significantly alter the analytical outcomes (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 2. Sensitivity analysis of natural hair color

Note: MR, Mendelian randomization.

Figure 4. Funnel plots illustrating the overall heterogeneity of Mendelian. (A) Blond hair group on endometriosis. (B) Red hair group on endometriosis. (C) Light brown hair group on endometriosis. (D) Dark brown hair on endometriosis. (E) Black hair on endometriosis.

Figure 5. Leave-one-out diagrams for causal effects on endometriosis. (A) Blond hair group on endometriosis. (B) Red hair group on endometriosis. (C) Light brown hair group on endometriosis. (D) Dark brown hair on endometriosis. (E) Black hair on endometriosis.

It has been reported that many loci involved in the pigmentation pathway affecting hair color (Lona-Durazo et al., Reference Lona-Durazo, Mendes, Thakur, Funderburk, Zhang, Kovacs, Choi, Brown and Parra2021). To exclude the mediating effect of pigmentation on the results, we further performed MR analysis of hair color and skin pigmentation. Despite the notable causal association between natural hair color and pigmentation, the p value for heterogeneity was nearly zero, which is undesirable (Table S3−S5). Consequently, we contend that a causal relationship between hair color and endometriosis is more plausible. Furthermore, Bayesian MR analysis was conducted to determine the plausibility of the study. Positive findings weres also observed (Table S6), which further reinforces our conclusions.

Our study provides evidence that individuals with dark brown hair exhibit an increased susceptibility to endometriosis. In contrast, dark hair color and lighter hair colors do not show a significant correlation with endometriosis risk. The absence of heterogeneity and directed pleiotropy, along with the robustness of our findings across various MR.

Discussion

In this study, we employed the two-sample MR methodology to explore the putative genetic connection between innate hair color and the onset of endometriosis. To enhance the comprehensiveness and robustness of our findings, we combined GWAS summary statistics derived from large-scale cohort studies with those sourced from traditional observational research. The analysis unveiled a compelling potential connection between natural hair color and the susceptibility to endometriosis, with a particularly pronounced association evident in individuals characterized by dark brown hair, indicating a lower propensity for endometriosis. The congruence in the effect sizes and directions across the robust MR techniques provided substantial backing for these observations.

Previous investigations have endeavored to unravel the possible causal nexus connecting natural hair pigmentation with the onset of endometriosis. In 1992, Frisch initially reported a suggestive correlation between red hair and endometriosis within a sample of 5398 alumnae (Frisch et al., Reference Frisch, Wyshak, Albert and Sober1992). Subsequently, Woodworth et al. (Reference Woodworth, Singh, Yussman, Sanfilippo, Cook and Lincoln1995) conducted a prospective investigation to assess the association between red hair color and endometriosis in a cohort of infertile patients, which included 143 women who underwent laparoscopy or laparotomy for infertility, with 12 exhibiting natural red hair. Their findings indicated that a higher proportion of red-haired women (83%) had endometriosis compared to non-red-haired women (42%), hinting at a potential link between red hair color and the onset of endometriosis (Woodworth et al., Reference Woodworth, Singh, Yussman, Sanfilippo, Cook and Lincoln1995). More recently, through a multicentric, retrospective study, Salmeri et al. (Reference Salmeri, Ottolina, Bartiromo, Schimberni, Dolci, Ferrari, Villanacci, Arena, Berlanda, Buggio, Di Cello, Fuggetta, Maneschi, Massarotti, Mattei, Perelli, Pino, Porpora, Raimondo and ¼ Candiani2022) identified a potential predisposition to ureteral endometriosis in patients with blonde or light brown hair. In addition, dysmenorrhea, a clinical symptom of endometriosis, has been linked to heightened pain sensitivity in women with red hair, as suggested by prior studies (Bohn et al., Reference Bohn, Bullard, Rodriguez and Ecker2021; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Kleisner and Flegr2017). This observation has also led to the hypothesis that there might be a connection between red hair and an increased susceptibility to endometriosis. However, the results of our MR analysis identified that red, blonde, and light brown hair color did not influence the risk of endometriosis. In a separate study within the NHSII cohort, which followed participants for 10 years, a total of 1130 cases of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis were analyzed, including 900 with no history of infertility and 228 with reported infertility assessments during the follow-up period. Notably, red-haired women without a history of infertility exhibited an increased risk of endometriosis, whereas those with infertility had a reduced risk. Conversely, dark brown hair did not influence the diagnosis rate of laparoscopic endometriosis (Missmer et al., Reference Missmer, Spiegelman, Hankinson, Malspeis, Barbieri and Hunter2006). Nevertheless, our finding that dark brown hair serves as a protective role for endometriosis is inconsistent with this. Another large French nested case-control study involving 4241 cases of surgically confirmed endometriosis did not observe a relationship between endometriosis risk and hair color (Kvaskoff et al., Reference Kvaskoff, Mesrine, Clavel-Chapelon and Boutron-Ruault2009). Therefore, the relationship between hair color and endometriosis is controversial and their specific causal relationship depends on many factors, such as regional differences, pregnancy, and disease history. Analysis for larger population sizes might help determine whether hair color can be utilized as a risk factor for endometriosis.

Although the mechanisms through which hair color influences endometriosis remain elusive, preliminary evidence and inferences may provide valuable insights. Genes associated with red hair (encoding eumelanin pigmentation) are located on chromosome 4 (Eiberg & Mohr, Reference Eiberg and Mohr1987). Red hair is inherited through mutations in the melanocortin-1 receptor gene (MC1-R), resulting in a lack of eumelanin (Healy et al., Reference Healy, Jordan, Budd, Suffolk, Rees and Jackson2001). Patients with red hair exhibit a reduction in coagulation and an increased risk of bleeding during surgical procedures. In a recent study, nine red-haired women were compared with nine ‘black’-haired women (all Caucasian, with similar height, weight, and age), and it was found that the platelet function of the red-haired women was significantly decreased, although there were no absolute differences in platelet count or coagulation factors (Stemberger et al., Reference Stemberger, Leimer and Wiedermann1984). Moreover, the genetic etiology of red hair color has been implicated in a deficiency of the immune system (Millington, Reference Millington2006), specifically in the coding of the third component of the complement system, which is located on chromosome 19. The manifestation of red hair may symbolize an underlying immunopathological condition that diminishes the clearance of retrograde menstrual debris, consequently augmenting the probability of ectopic pregnancies (Eiberg et al., Reference Eiberg, Mohr, Nielsen and Simonsen1983). It has been documented that the levels of leukocytes, particularly macrophages, T lymphocytes, and natural killer cells, are elevated in the peritoneal fluid of women affected by endometriosis (Woodworth et al., Reference Woodworth, Singh, Yussman, Sanfilippo, Cook and Lincoln1995). Halme et al. (Reference Halme, Becker and Haskill1987) conducted a comparative study on the secretion profiles of peritoneal macrophages between women with and without endometriosis, discovering that those with the condition secreted higher levels of growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Research has found that the gene for brown hair color is located on chromosome 15 and is linked to aromatase (CYP19; Pośpiech et al., Reference Pośpiech, Teisseyre, Mielniczuk and Branicki2022). It has been reported that in Chinese Han women, the CYP19 gene polymorphism is not associated with susceptibility to endometriosis or chocolate cysts, but the CYP19 rs700518AA genotypes are associated with genetic susceptibility to infertility related to endometriosis (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Lu, Wang, Qu, Li, Xu, Huang, Han and Lv2014). Therefore, brown hair color may influence endometriosis through the mechanism of genetic linkage. Overall, the specific mechanisms through which hair color influences endometriosis remain contentious and warrant further investigation.

When interpreting our research results, it is necessary to recognize certain limitations. First, the specific demographic limitations of the European population may restrict the generalizability of our findings, which might not be suitable for other populations. Second, the use of relaxed linkage disequilibrium (LD) threshold could inadvertently engender feeble instrumental biases or augment the probability of encountering horizontal pleiotropy. Additionally, the scarcity of GWAS data tailored to different endometriosis types hinders a more comprehensive assessment of its role as a potential confounder. Moreover, IVs generally encapsulate only a fraction of the exposure’s variability, leading to the absence of power calculations in our study, thus reducing statistical power for rejecting the null assumption. To enhance statistical power, it is advisable to incorporate more publicly available GWAS summary statistics into MR analyses. Moreover, although we cannot entirely exclude the presence of minor effect magnitudes or nonlinear relationships, we can dismiss certain effect sizes documented in observational research. It is important to note that these MR estimates are interpreted as the causal effect of a genetically predicted predisposition to a particular natural hair color on endometriosis risk. In other words, the ORs obtained should be understood as reflecting differences in endometriosis risk between populations with genetic variants strongly associated with having a specific hair color and those without these variants, rather than the effect of changing one’s hair color at a given point in life. The results do not imply that altering hair color would affect endometriosis risk. Instead, the findings highlight potential shared biological pathways influenced by pigmentation-associated genes.

Endometriosis, a multifactorial disease with unknown etiology, exerts a substantial impact on women’s health and quality of life. Identifying the protective factors of endometriosis is crucial for understanding the development and progression of the disease. Cardoso et al. (Reference Cardoso, Abrão, Vianna-Jorge, Ferrari, Berardo, Machado and Perini2017) conducted a case-control study comprising 293 cases and 223 controls to investigate the role of SNPs in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR2 as potential risk factors for endometriosis. They found that the VEGF +405G>C and VEGFR2 1192C>T polymorphisms are associated with a protective effect against the development of endometriosis, with the VEGFR2 1192C>T linked to a reduction in cyclical urinary symptoms. Another case-control study conducted in 2019 indicated that not being breastfed may confer protection against the development of deep infiltrating endometriosis in Chinese women, highlighting early-life exposures as potential factors associated with the pathogenesis of endometriosis (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Zhang, Xue, Zhou, Sun and Leng2019). More recently, Li, Liu et al. (Reference Li, Liu, Ye, Zhang, Li, Yuan, Du, Wang and Yang2023) demonstrated that plasma levels of A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13 (ADAMTS13) negatively affect the development of endometriosis through MR analysis. The identification of these factors not only enables the formulation of more tailored preventive strategies but also informs early intervention tactics for individuals at heightened risk. In our study, dark brown hair color was a protective factor for endometriosis, which may have important implications for the prevention and early diagnosis of this disease. The strategic application of diverse diagnostic techniques for individuals without dark brown hair can significantly enhance endometriosis detection rates, thereby facilitating timely intervention and potentially mitigating disease progression.

Conclusion

Our study first explored the causal relationship between natural hair pigmentation and the risk of endometriosis by a two-sample MR analysis. Our results indicate that the presence of dark brown hair is linked to a reduced likelihood of developing endometriosis, suggesting potential genetic or environmental links that could influence the disease’s prevalence among different hair color groups. Hence, it may be crucial to conduct an exhaustive investigation into the potential mechanisms through which dark brown hair may confer protection against endometriosis. This endeavor might require the execution of a larger MR study or a well-structured randomized controlled trial to further elucidate these underlying pathways.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2025.1.

Availability of data and materials

All data used for Mendelian randomization analyses are publicly available from the GWAS. Data from UK Biobank are available after the application (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

Author contributions

YPZ did the analysis and interpretation of data, drafted the article and revised it critically. Y. provided academic guidance for this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Youth Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31800677).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants gave written informed consent before data collection. UK Biobank has full ethical approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (16/NW/0274).