Introduction

Salmonella Spp and Coliform bacteria are widely regarded as key indicators of microbial contamination in milk, posing considerable health risks due to their link with pathogens known to cause severe gastrointestinal and systemic diseases, In areas with limited regulatory oversight, such as Minna, Niger State, inadequate milk handling and processing practices contribute significantly to the dissemination of coliforms and multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. Simultaneously, the widespread and often indiscriminate use of antimicrobials in both poultry and dairy production systems has significantly exacerbated the emergence and dissemination of MDR bacteria. This challenge is particularly critical in integrated farming environments, where close contact between animals, shared water sources, and common equipment increase the risk of cross-contamination and horizontal gene transfer (HGT) (Van Boeckel et al., Reference Van Boeckel2015; Nhung et al., Reference Nhung2016). In livestock systems, antimicrobials are frequently administered not only for therapeutic purposes but also for growth promotion and disease prevention often without veterinary oversight. This practice has been identified as a key driver of resistance selection pressure in both commensal and pathogenic bacteria (Marshall & Levy, Reference Marshall and Levy2011; Landers et al., Reference Landers2012). As a result, bacteria such as E. coli, Salmonella, and Klebsiella spp., commonly found in poultry litter, feces, and raw milk, have increasingly acquired resistance to critical antibiotics, including third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones (Laxminarayan et al., Reference Laxminarayan2013).

Moreover, the presence of mobile genetic elements such as plasmids, integrons, and transposons facilitates the horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) between different bacterial species and genera within these environments (Carattoli, Reference Carattoli2013). This gene exchange can occur through mechanisms such as conjugation, transformation, or transduction, making MDR traits more pervasive and persistent across animal populations and into the wider ecosystem including human handlers and consumers (Manyi-Loh et al., Reference Manyi-Loh2018; Allen et al., Reference Allen2010).

Given these dynamics, integrated poultry-dairy farms represent a critical hotspot for the amplification and transmission of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens. Addressing this issue requires a One Health approach, encompassing coordinated action across veterinary, agricultural and public health sectors to ensure responsible antimicrobial use, biosecurity enhancements and routine surveillance of resistance trends (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson2016; WHO, 2017).

These settings have become critical reservoirs for antimicrobial-resistant pathogens that pose a direct transmission risk to humans through foodborne pathways, environmental exposure and close contact (González-Acuña et al., Reference González-Acuña2021; Kirschke et al., Reference Kirschke, Grunert and Wiegand2022; Musoke et al., Reference Musoke, Kansiime and Muhumuza2023).

Studies in recent years underscore the role of poor hygiene practices in accelerating the spread of microbial contamination in dairy products, particularly in informal market settings where pasteurization and regulated milk handling are not widely practiced (Omore et al., Reference Omore2021). Furthermore, the increased reliance on antibiotics in intensive dairy-poultry production has fostered selective pressure, enabling resistant strains like Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella spp. to proliferate. This rise in resistance in animal agriculture creates serious public health concerns as MDR pathogens can easily enter human food systems and complicate treatment outcomes for infections caused by these pathogens (Tadesse et al., Reference Tadesse, Abebe and Melesse2020; Anyanwu et al., Reference Anyanwu, Okwori, Ogbondeminu and Nwankwo2023).

Proactive interventions, including stricter regulation of antimicrobial use in diary production and enhanced milk processing standards, are increasingly recognized as essential strategies to mitigate the risks associated with MDR bacteria in food systems (Kebede et al., Reference Kebede2023).

Importance of the study

The convergence of milk contamination and the prevalence of MDR bacteria in integrated dairy-poultry production systems presents a significant public health threat, particularly in developing countries where antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance and regulatory frameworks are often inadequate (WHO, 2017; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson2016). In such settings, limited access to veterinary services and weak enforcement of antimicrobial stewardship contribute to the unchecked use of antibiotics in animal husbandry, creating ideal conditions for the selection, amplification, and spread of resistant bacterial strains (Van Boeckel et al., Reference Van Boeckel2015; Laxminarayan et al., Reference Laxminarayan2013).

This study is particularly relevant in the context of integrated livestock farms where cows, poultry, and sometimes rodents coexist within shared spaces. Such proximity facilitates not only environmental contamination but also the exchange of resistance genes through HGT mechanisms – especially plasmid-mediated conjugation – between bacterial species from different animal reservoirs (Carattoli, Reference Carattoli2013; Allen et al., Reference Allen2010). The detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli, Salmonella, and Klebsiella spp. in milk and poultry droppings raises alarm over potential zoonotic transmission routes, especially through the food chain and direct animal–human interactions (Manyi-Loh et al., Reference Manyi-Loh2018; Nhung et al., Reference Nhung2016).

Furthermore, dairy products, particularly raw milk, are widely consumed in many low-income communities without pasteurization, making the presence of MDR pathogens a direct food safety hazard (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver2005). The use of antimicrobials in poultry for growth promotion and disease prevention can contribute to the persistence of resistant bacteria in litter, which may serve as a reservoir for resistant genes that could contaminate milking environments and water sources, subsequently reaching dairy animals and their products (Graham et al., Reference Graham2009; Leonard et al., Reference Leonard2011).

By investigating the prevalence and resistance profiles of bacterial isolates across cow milk, poultry droppings, and rodent reservoirs on a single integrated farm, this study provides valuable insights into the interconnectedness of microbial ecosystems. It also emphasizes the critical need for holistic One Health approaches that integrate animal health, food safety, and environmental monitoring to mitigate the risks of AMR at the human-animal-environment interface (FAO/OIE/WHO, 2022).

Specifically, this study aims to:

-

Assess the level of microbial contamination in raw cow milk from integrated farms.

-

Isolate and identify MDR bacteria from both dairy and poultry sources.

-

Characterize the resistance profiles and determine the presence of ESBL-producing organisms.

-

Explore potential linkages and shared resistance mechanisms between bacterial populations from different sources on the same farm.

-

Provide evidence-based recommendations for improving antimicrobial stewardship, biosecurity, and hygiene practices in integrated livestock systems.

-

To detect Salmonella invA virulence gene using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

-

To determine the antibiotic resistance patterns of E.coli, Klebsiella and Salmonella isolates to commonly used antimicrobial agents

-

To detect the presence of major ESBLs family of genes (blaTEM and blaSHV) by multiplex PCR .

Materials and methods

Study area

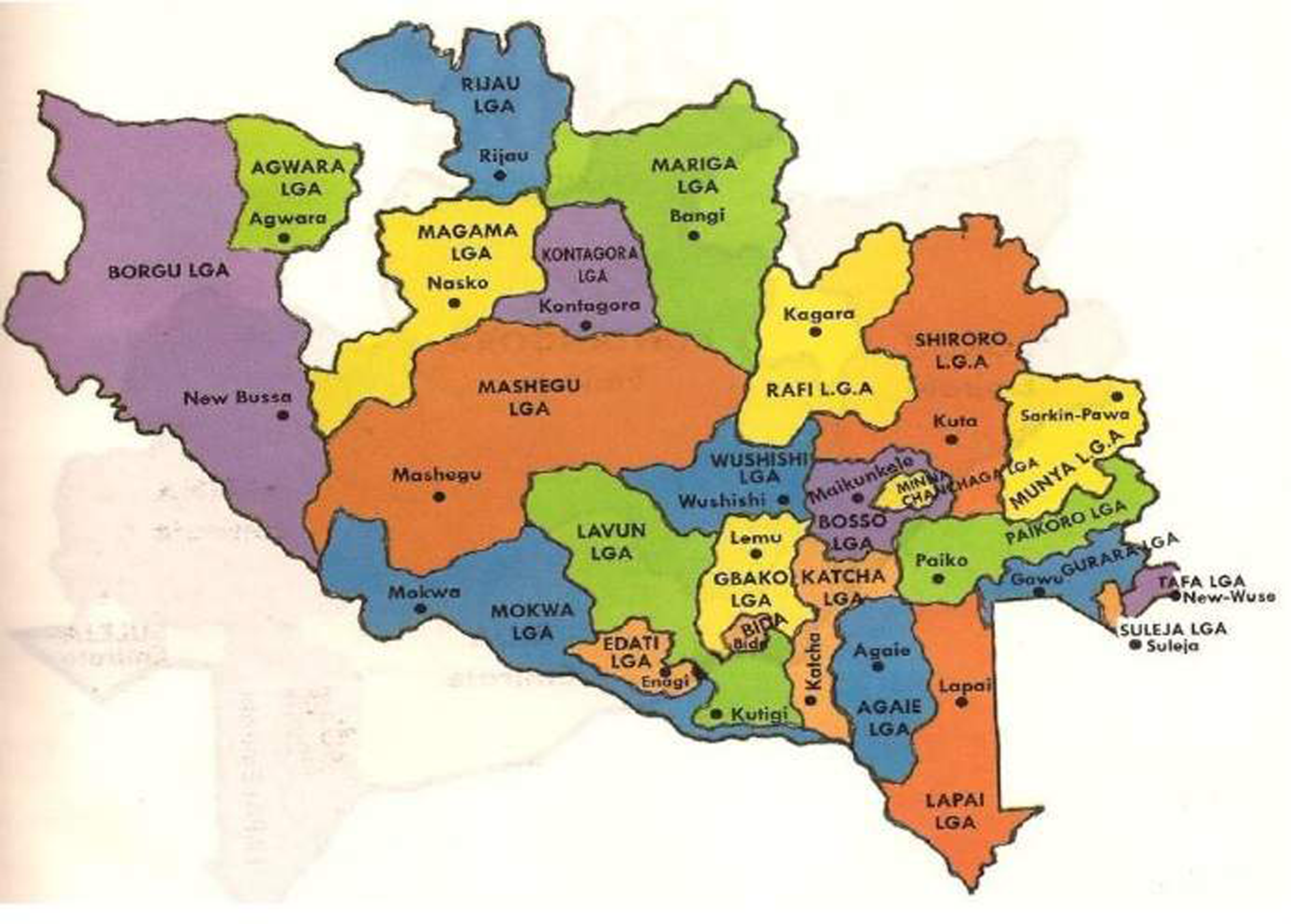

The study was conducted in Minna, Niger State, Nigeria, targeting three primary locations: Bosso, Tunga, and Chanchaga. Milk samples were collected from vendors, while bacterial samples were obtained from poultry farms for comparative analysis. Niger State (Figure 1) is situated in the North Central geo-political zone lying between longitude 10o00’N and latitude 6000’E. It shares borders with the Republic of Benin (West), Zamfara State (North), Kebbi (North-West), Kaduna (North-East), Kogi (South), Kwara (South West) and the FCT (South-East). The State is comprised of 3 geo-political Zones with (Zone ‘A” with 8 LGAs; Zone ‘B” with 8 LGAs; while Zone ‘C” has 9 LGAs) a total of 25 Local Government Areas (LGAs).

Figure 1. Map of Niger state showing the location of LGAs (Source: Google maps).

Study design

A cross-sectional study involving commercial poultry farms in Minna registered with Veterinary clinic Bosso was conducted. Sampling was carried out between the months of January and April, 2024. The sampling was done with farmer’s consent.

Sample collection

Sampling method

The samples included poultry cloacal swabs and intestinal contents rats trapped in poultry houses in various commercial poultry farms in Minna. The sampling was done with farmer’s consent. The captured rats were immediately transported to biotechnology center of FUT Minna wrapped in a pack of ice and aseptically dissected and different segments of small and large intestinal contents were taken and homogenized for each rat before inoculated in an enrichment media and incubated overnight for growth

Laboratory procedure

Salmonella

For isolation of Salmonella, fecal specimens from rat and swab samples from chicken were directly inoculated into Rappaport and Vasiliadis (RVS) broth for selective enrichment. The RVS broth was incubated over night at 42˚C under aerobic conditions. A loop of inoculum from the RVS broth was then streaked onto Salmonella-Shigella agar (SSA) and incubated for 24 h at 37˚C in an incubator; pink colonies were then inoculated onto nutrient agar slants and incubated at 37˚C for 24 h. After growth the nutrient slants were stored in the refrigerator pending further biochemical testing.

E.coli and Klebsiella spp

For isolation of E.coli and Klebsiella the intestinal swab and cloacal swabs collected were directly inoculated into E. Coli broth for selective enrichment and incubated for 24 h for growth.

Klebsiella Suspension from Es. Coli broth were then streaked onto MacConkey (MAC) agar and E.coli suspension from E. Coli broth were streaked on E.M.B agar and incubated for 24 h at 37˚C in an aerobic environment. MAC agar is a selective medium for Enterobacteriaceae organisms, which are lactose fermenting and produce a green metallic sheen on the media was considered a suspect of E.coli and was then inoculated onto nutrient agar slants and incubated at 37˚C for 24 h. After growth the nutrient slants were stored in the refrigerator pending further procedures.

Biochemical tests

Biochemical tests were performed on the isolates stored on nutrient agar slants.

TSI was performed first to screen the isolates:

Triple sugar iron (TSI) and urease test

Two colonies were selected from each plate, based on their appearance. Salmonella organisms are lactose and sucrose negative, and their colonies appeared pinkish on the red SS agar background. The selected colonies were inoculated onto TSI (triple-sugar iron) agar, and those which exhibited an alkaline slant, an acid butt, and H2S production were subjected to further biochemical testing. Colonies that demonstrated positive motility, and were lysine decarboxylase positive and indole negative, was presumptively considered to be Salmonella, and was subcultured and stored on TSA (tryptic soy agar) slants.

E.coli

Isolates that exhibited an acid slant over acid and no H2S production on TSI were subjected to further biochemical testing. Colonies that were indole and decarboxylase positive, regardless of motility, were considered to be E. coli, and were subcultured and stored on TSA slants at 42° C.

Biochemical characterization

Appropriate biochemical tests which included; Triple Sugar Iron agar (TSI), Urease, Indole, Motility, Citrate Utilization, Methyl Red-Voges Proskauer (MRVP) and carbohydrate fermentation which includes: Rhamnose, Mannitol, Maltose, xylose, Lysine, Ornithine tests as earlier described (Cheesbrough, Reference Cheesbrough2003; Odewumi, Reference Odewumi1981).

Triple sugar iron test

TSI slants were prepared according to manufacturer’s recommendation (Oxoid UK). The TSI slants were inoculated by stabbing the butt and streaking the surface of the slants with sterile straight wire containing the test organism. The slants were incubated at 37° C for 24 h. After 24 h the reaction of Salmonella organisms on TSI slant was Alkaline over acid (Pink slant, Yellow butt), and gas (crack or bubble in the agar), and hydrogen sulfide (black coloration) was produced.

Urease test

Urea slants were prepared according to manufacturer’s recommendation (Oxoid UK). The urea slants were then inoculated by streaking the surface of the slants with a loopful of the test organism. The test tube were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. A positive result was indicated pink coloration and a negative result there was no change in color. The isolates of Salmonella species are urease negative.

Indole test

The test was conducted using SIM medium (Oxoid UK). It was prepared according to manufacturer’s recommendation. The isolates was grown in 5 ml of peptone water and incubated at 37° C for 24 h, followed by addition of three drops of Kovacs reagent and shaken gently.

Salmonella species are indole negative and this is indicated by the indole reagent retaining its yellow color (Cheesbrough, Reference Cheesbrough2003).

Motility test

The motility medium was inoculated by making a fine stab using a straight wire loop to a depth of 1 – 2 cm short of the bottom of the test tube and incubated at 37° C for 24 h. Salmonella species give a cloudy appearance since they are motile (Cheesbrough, Reference Cheesbrough2003).

Citrate test

Citrate was prepared according to manufacturer’s recommendations (BIOTEC, United Kingdom). Citrate slants were inoculated by using sterile wire loop carrying the culture to be inoculated by swabbing the surface. Slants were incubated at 37° C for 24 h. Salmonella species is citrate positive, hence, the medium turned blue while E.coli is citrate negative and the color remained unchanged.

Methyl red (MR) and Voges Proskauer (VP) tests

Five mls of MR-VP broth was inoculated and incubated for 48 h at 37° C. After incubation, 1 ml of the broth was transferred to a small tube and 2–3 drops of Methyl Red was added. Salmonella species are Methyl Red positive which was indicated by formation of ring at the top of the tube a red coloration. To the rest of the broth in the tube, 15 drops of 5% ᾳ-Naphthol in ethanol followed by 5 drops of 40% potassium hydroxide was added, shaken and placed in a sloppy position. Salmonella are Voges-Proskauer negative, hence no color change occurred (Cheesbrough, Reference Cheesbrough2003).

Sugars (mannitol, maltose, rhamnose and xylose)

One gram (1g) of each sugar was weighed and 1.5g of andrate peptone water was also weighed and mixed in a conical flask, which was dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water and 5 ml was dispensed into sterile test tubes and steamed at 115° C for 5 – 10 min and allowed to cool. A colony subcultured on a selective medium was picked and inoculated into the test tubes, after which they were incubated for 24 – 48 h at 37°C. Red coloration indicated a positive result while light pink coloration indicates a negative result.

Amino acid decarboxylase test (arginine, ornithine and lysine)

One gram of each amino acid was weighed along with 1.5g of peptone water, dissolved in 100mls of distilled water, which was dispensed into sterile test tubes, heated for 5 – 10 min and allowed to cool. The stored isolates were inoculated in to the tubes and then 2 – 3 drops of mineral oil will be added to them, which was covered and kept incubator for 24hours.

Milk Samples: Fresh milk samples were collected aseptically from various vendors and transported under refrigeration to the laboratory.

Microbiological and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Coliform Detection and Identification: MacConkey agar was used to detect coliforms in milk. Presumptive coliform colonies were further analyzed using biochemical tests and molecular identification (16S rRNA sequencing).

Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing: Isolates from milk and poultry were tested for susceptibility to 20 antibiotics. The Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method was employed, and multidrug resistance was defined as resistance to three or more antibiotic classes. ESBL production was confirmed using the combined disk test and multiplex PCR to detect blaTEM_ and blaSHV_ genes.

Determination of antibiotic susceptibility of E. coli, Klebsiella and Salmonella isolates

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) protocol (2011) was used to determine the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of all isolates by disk diffusion method (Sarkar, Reference Sarkar2015b). Four to five (4 – 5) colonies of the test isolates from a purified culture were picked using sterile Pasteur loop and emulsified in sterile normal saline. The turbidity of the suspension was adjusted to 0.5 MacFarland’s standard and then 100 μl of the suspension was dispensed and evenly spread on Mueller-Hinton agar plates. Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of all isolates confirmed to be E. coli, Samonella and Klebsiella from the Microbact 12E test was determined using a panel of twenty four antibiotic discs obtained from Oxoid (UK). Sulfamethoxazole/ Trimethoprim (25 μg), (5 μg), Kanamycin (30 μg), Gentamicin (10 μg), Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid (20 μg + 10 μg),Tetracycline (30 μg), Ticarcillin/Clavulanic acid (85 μg), Ampicillin (10 μg), Streptomycin (10 μg), Chloramphenicol (30 μg), Cephalothin(30 μg), Cefazolin (30 µg), Cefixime (5 µg), Cefoxitin (30 µg), Ofloxacin (5µg) Enrofloxacin (5 μg), Ciprofloxacin (5 μg), Nalidixic acid (30 µg), Cefotaxime (30 µg), Ceftazidime (30 µg), Imipenem (10 µg), Nitrofurantoin (300 µg), Fosfomycin (200 µg), Azithromycin (15 µg). A disk dispenser (Oxoid UK) was used to apply the discs on the surface of each of the pre-inoculated Mueller-Hinton plates which were then incubated aerobically at 37˚C or 24h. After incubation the diameters of the zones of inhibition were measured to the nearest millimeter (mm) using a meter rule and classified as susceptible (S), intermediate resistance (I) or resistant (R) according to the CLSI (2011) criteria.

Detection of Salmonella invA gene

Extraction of salmonella DNA

Bacteria were cultured on nutrient agar for 24 h at 37° C. Extraction of DNA was performed by boiling for 10 min and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was used for amplification by PCR with specific primers.

Primer set and PCR amplification program

Salmonella specific primers, S1319 and S141 (Rahn et al., Reference Rahn, De Grandis, Clarke, McEwen, Galán, Ginocchio, Curtiss and Gyles1992) have respectively the following nucleotide sequences based on the invA gene of Salmonella forward5´ GTG AAA TTA TCG CCA CGT TCG GGC AA -3´and Reverse 5´ TCA TCG CAC CGT CAA AGG AAC C -3´. Reaction with these primers was carried out in a 50µl amplification mixture consisting of 25µl of PCR Master mix (Genei, Bangalore), 2µl of each primer, 19 µl of molecular grade water and 2 µl of DNA extraction for each isolate was used in the reaction.

Amplification was conducted in Master-gradient Thermocycler (Eppendorf). The cycle conditions were as follow: An initial incubation at 94° C for 60 sec, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94° C for 60 sec, annealing at 64° C for 30 sec and elongation at 72° C for 30 sec, followed by 7 min final extension period at 72° C.

Electrophoresis of PCR products

The amplified DNA product from Salmonella specific-PCR were analyzed with electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and visualized by UV illumination. Separation was carried out at a current of 120 V. Eight micro liter of PCR product mixed with 3µl of 6 X-loading dye (Genei, Bangalore), and loaded on to agarose gel. A 100bp DNA ladder was used as a marker for PCR products.

Multiplex PCR protocol

Isolates showing increased zone of inhibition to third-generation cephalosporins that is, ceftazidime (30 mg), cefotaxime (30 mg) and to fourth generation cephalosporins, cefepime (30 mg), were screened for ESBL production.

ESBL detection: ESBL detection was carried out following the CLSI recommended method for screening and confirmation using cefotaxime and ceftazidime as substrates (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), 2006). Cefepime were tested as substrate following the same method. A >5 mm increase in zone diameter for either antimicrobial agent tested in combination with clavulanic acid versus its zone when tested alone was taken as positive result for ESBL production.

Reference strains: Three strains, E. coli J53 R1, E. coli C600PUD16 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 700,603 were used as standard ESBL-positive strains. E. coli J53 R1 harbored TEM-ESBL and the remaining strains carried SHV-ESBL. A non ESBL-producing organism (E. coli ATCC 25,922) was used as negative control.

Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria

Genomic DNA was purifying by phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation method. The DNA was stored at −20˚C. The samples were run on 0.8 per cent agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The stained gel was examined under UV light for the presence of plasmid bands of particular size using a molecular weight marker; λ DNA HindIII double digest (Roche, USA). PCR for beta -lactamase encoding genes: PCR analysis for b-lactamase genes of the family TEM and SHV was carried out. Primers obtained from Sigma, USA used for bla TEM are 5’AAAATTCTTGAAGACG 3’ and 5’TTACCAATGCTTAATCA 3’ and for bla SHV are 5’ TTAACTCCCTGTTAGCCA 3’ and 5’GATTTGCTGATTTCGCCC 3.’ For PCR amplifications, about 500 pg of DNA was added to 50 ml mixture containing 200 mM of dNTPs, 0.4 mM of each primer and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Roche diagnostics) in 1× PCR buffer. Amplification was performed in a Techne® Genius Thermocycler (Cambridge, UK) with cycling parameters comprising initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles each of denaturation at 94° C for 30 sec, annealing at 50° C for 30 sec, amplification at 72° C for 2 min and final extension at 72° C for 10 min, for the amplification of bla TEM. For bla SHV amplifications conditions for thermal cycling was same except for Tm of 55° C. The amplified products will be separated in 1.5 per cent agarose gel. The gel was visualized by staining with ethidium bromide (0.5 mg/ml) in a dark room for 30 min. A 100 bp ladder molecular weight marker (Roche, USA) was used to measure the molecular weights of amplified products. The images of ethidium bromide stained DNA a band was digitized using a gel documentation system (AlphaimagerTM 3400, USA).

Restriction digestion analysis: The 1080 bp and 768 bp PCR products of TEM and SHV genes respectively were digested with restriction enzymes BSeG1, Pst 1and EcoR 1 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, USA) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. After digestion, the products were run on 1.5 per cent agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The stains gels were examined under UV light for the DNA bands of particular size using a molecular weight marker of 100 bp ladder.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistical analysis in to simple percentages, tables, figures and charts.

Result

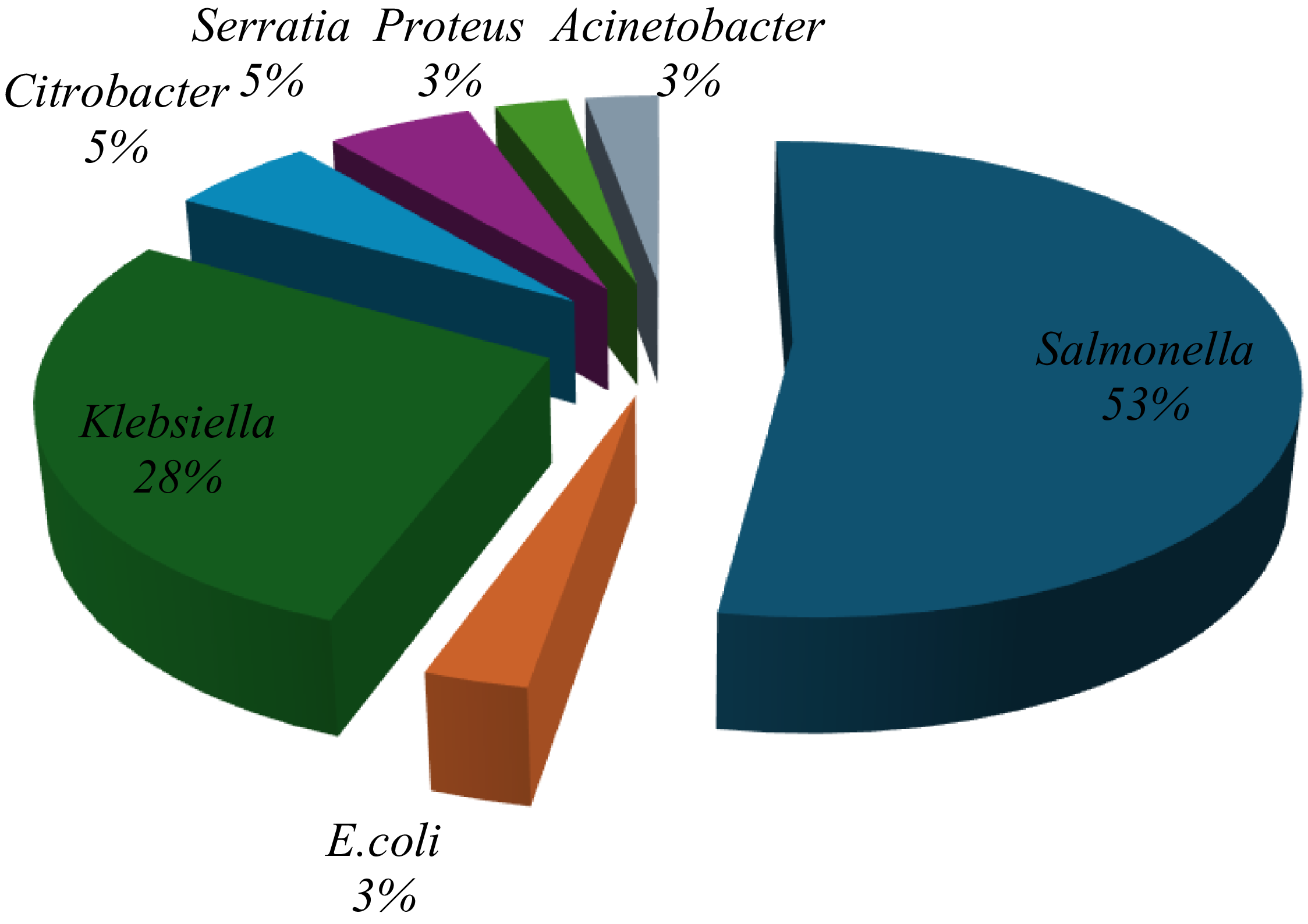

A total of 321 milk samples were collected from a commercial dairy in Minna and tested for bacterial contamination. Initial screening using conventional biochemical tests identified 24 samples (30.4%) as positive for E. coli, 35 samples (44.3%) for Salmonella spp., and 20 samples (25.3%) for Klebsiella spp. However, subsequent confirmation using the Microbact® identification system yielded different results: 19 isolates (52.7%) were confirmed as Salmonella spp., while only 1 isolate each (2.8%) was confirmed as E. coli and Klebsiella spp., respectively. Additionally, 10 isolates (27.8%) were identified as Citrobacter spp. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportions of different organisms identified from milk identified by Microbact.12E.

Antibiograms of Salmonella isolates

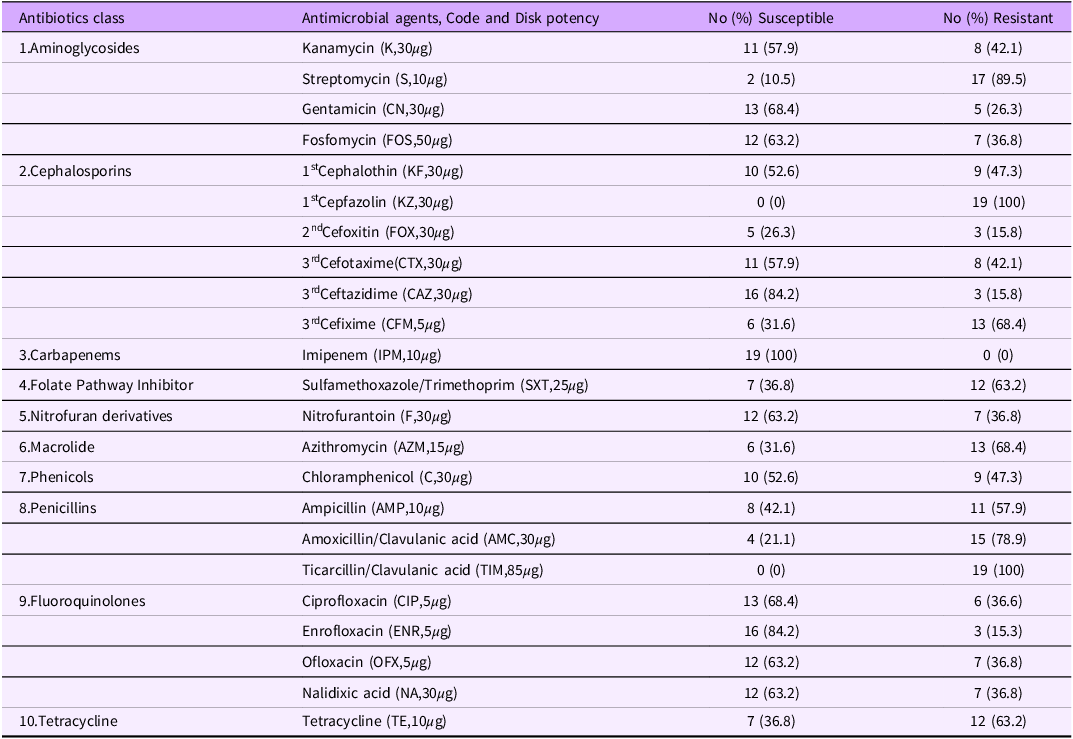

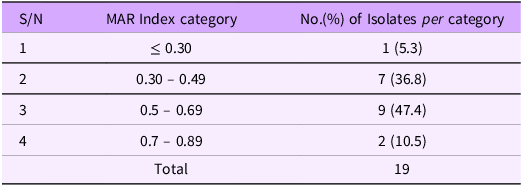

Nineteen (19) Salmonella spp isolates confirmed by Microbact were tested against 23 antibiotics (representing ten antibiotic classes) using standard disk diffusion sensitivity method (Table 1).

Table 1. Antibiotic susceptibilities of 19 Salmonella isolates milk to 23 different antibiotics

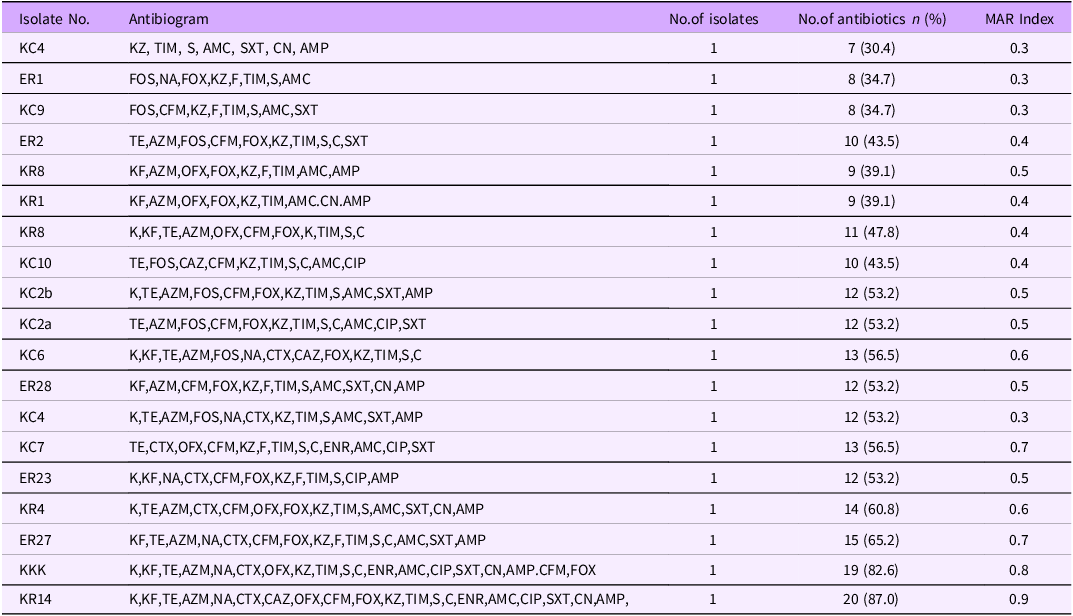

Multi-drug resistance patterns of Salmonella from milk

All the isolates showed resistance to at least four different classes of antibiotics, and thus classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR). The resistance profiles of MDR Salmonella spp ranged from 7 to 20 antibiotics (Table 2) and the isolate that was resistant to the highest number of antibiotic was sensitive only to imipenem

Table 2. Multi-drug resistance patterns of 19 Salmonella isolates from milk to 23 Different antibiotics

Antibiotic susceptibility of E.coli and Klebsiella isolates

Antibiotic susceptibility of E.coli against a panel 23 antibiotics indicated resistance to 13 (56.5%) different antibiotics, while Klebsiella spp showed resistance to 14 (60.9%) different types. The organisms were multidrug-resistant and expressed resistance to at least 9 different antibiotics. Both organisms showed sensitivity to Enrofloxacin, Ampicillin, Gentamicin and Kanamycin. E.coli as MARI of 0.7 and Klebsiella spp had 0.6 respectively (Table 3)

Table 3. Multiple antibiotic resistance index (MARI) of 19 Salmonella isolated from milk

Multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) indices of Salmonella isolates

The antibiograms were used to calculate the multiple antibiotic resistances (MAR) indices. Multi-drug resistance, as defined by the joint committee of European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, was observed in all the 19 Salmonella isolates (100%). Out of these, only 1(5.3%) isolate had MAR index of ≤ 0.30 (cut off value) where as 7(36.8%) isolates had values between 0.30 and 0.49,9 (47.4%) and 2(10.5%) isolates had values between 0.50 and 0.69 and 0.70 and 0.89 respectively (Table 3)

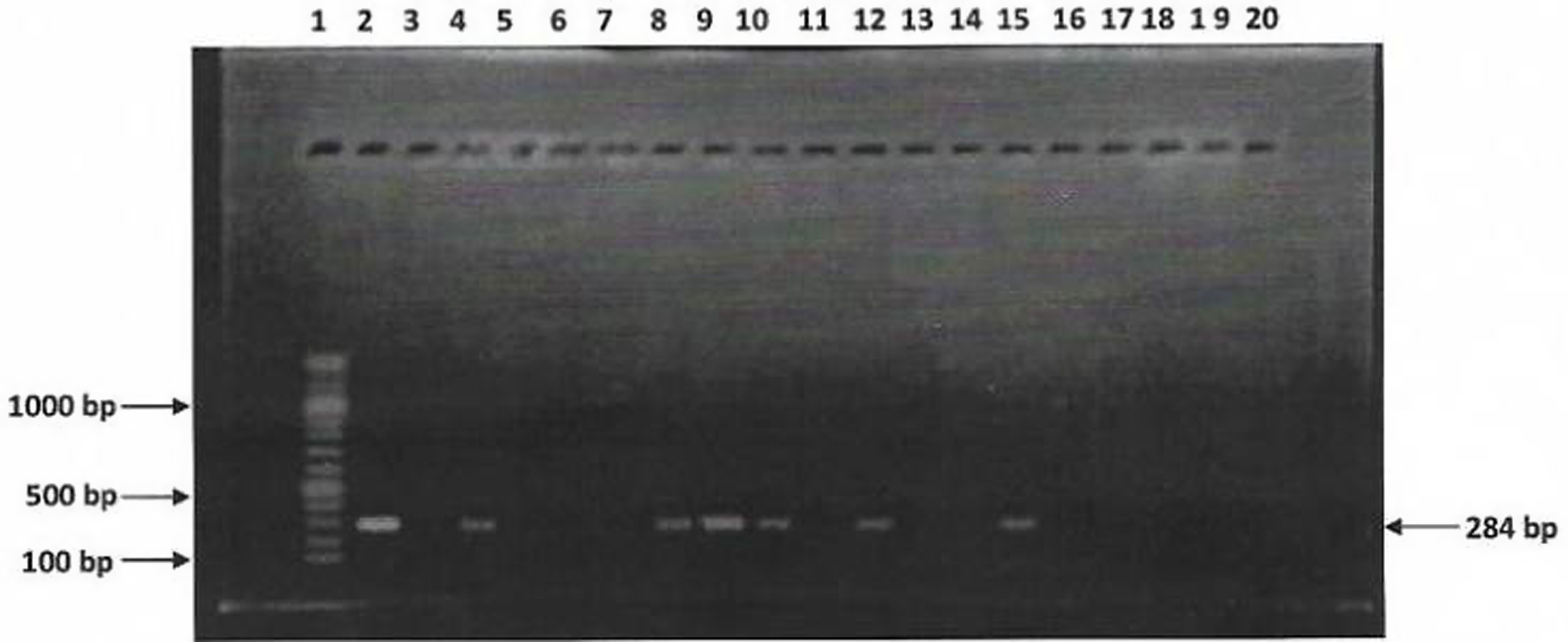

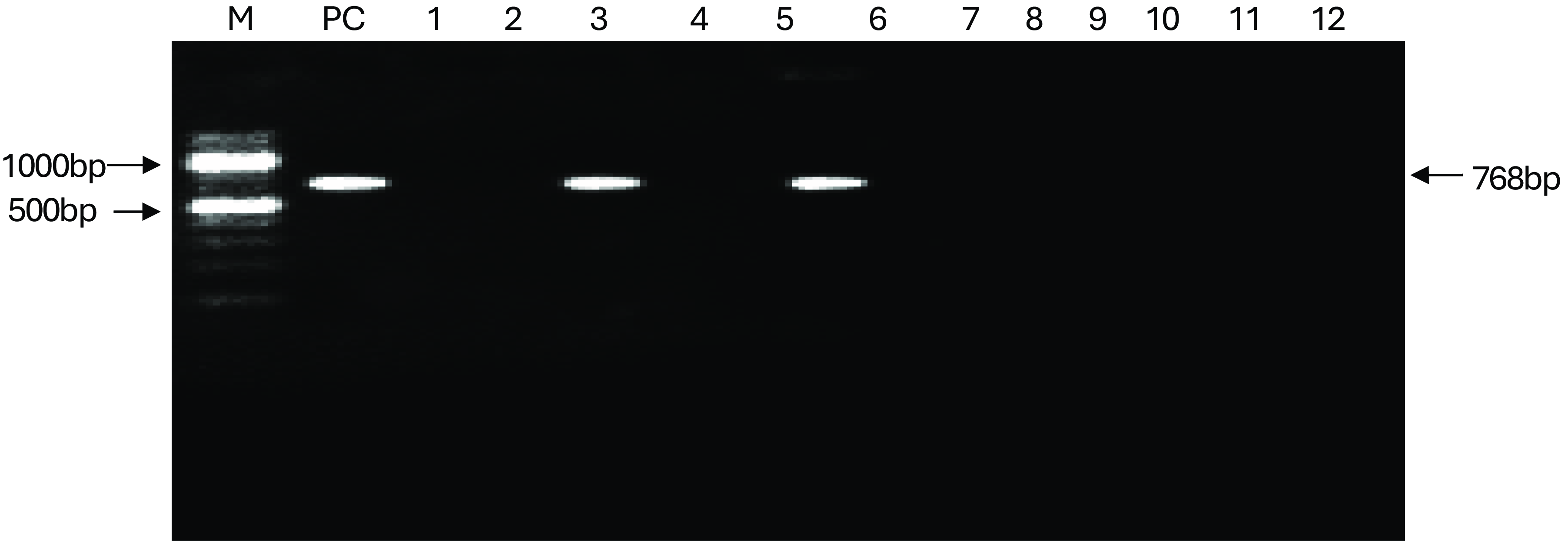

Detection of inva gene in Salmonella isolates

Sixteen (16) Salmonella isolates were examined for the presence of invA gene using PCR. Figure 3 show agarose gel electrophoresis picture of the PCR. Only six (6) out of sixteen isolates were positive for invA (284bp). Figures 4 and 5 showed agarose gel electrophoresis picture of the multiplex PCR for beta-lactamase genes. Of the 12 isolates tested 3(25%) showed amplification of genes corresponding to blaTEM (1080bp) and 2(16%) isolates showed blaSHV (768bp). This indicates co-carriage of these genes in the Salmonella species isolated and which were also multidrug-resistant.

Figure 3. PCR detection of invA virulence gene in 16 Salmonella isolates. L1 = 100bp DNA ladder, L2 = Positive control, L3 to 18 are isolates KC9, KR8, KC2, KR1, KC7, KKK, KC4, KR4, KC10, KR14, KCa2, KC7, SC2, ER8, ER27 and EC6, respectively; L19 = Negative control.

Figure 4. PCR detection of bla TEM in Salmonella isolates, M = DNA marker, PC = positive control, ladder: 1 to 12, are isolates: KC9, KR8, KC2, KR1, KC7, KKK, KC4, KR4, KC10, KR14, KCa2, KC7, respectively; NC = negative control.

Figure 5. PCR detection of blaSH gene in Salmonella isolates, PC = positive control, Lanes 1 to 12, are as follows KC9, KR8, KC2, KR1, KC7, KKK, KC4, KR4, KC10, KR14, KCa2, KC7, respectively NC = negative control.

Prevalence of Coliforms in milk samples

Out of the total milk samples analyzed, 68.8% of fresh milk and 98.1% of fermented milk samples were positive for coliforms. Notable coliform species included E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and Citrobacter murliniae. Contamination rates were highest in Chanchaga, suggesting site-specific factors affecting hygiene.

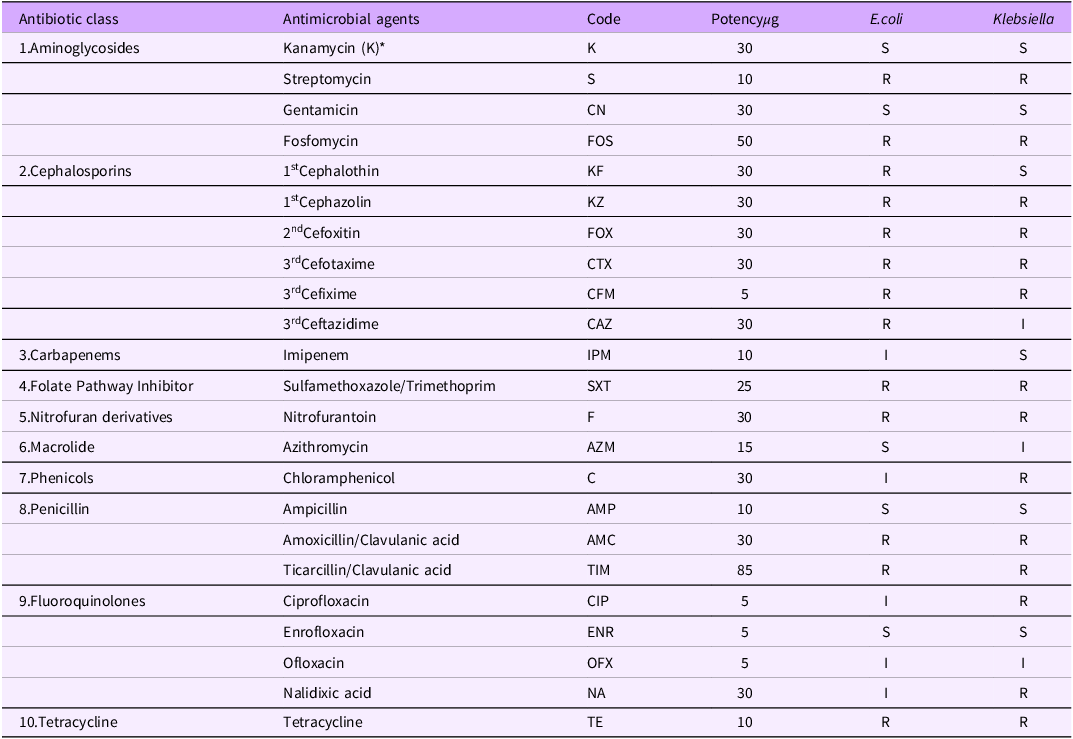

Antibiotic resistance in relation to dairy and poultry farming

Table 4 presents the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of E. coli and Klebsiella species isolated from rats and chickens. The findings reveal widespread resistance across multiple antibiotic classes, including aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, folate pathway inhibitors, nitrofuran derivatives, and tetracyclines highlighting the serious threat of MDR bacterial contamination in animal production systems

Table 4. Antibiotic susceptibilities of E.coli and Klebsiella isolates from rats and chickens

From milk samples, Salmonella, E. coli, and Klebsiella spp. showed high levels of AMR. Among the isolates:

53% were identified as Salmonella with ESBL production.

Resistance profiles showed that 92% of isolates had a MAR index above 0.2, indicating exposure to high levels of antimicrobial agents.

MDR Salmonella isolates were particularly resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, with resistance frequencies of 68.4% to cefixime and 42.1% to cefotaxime.

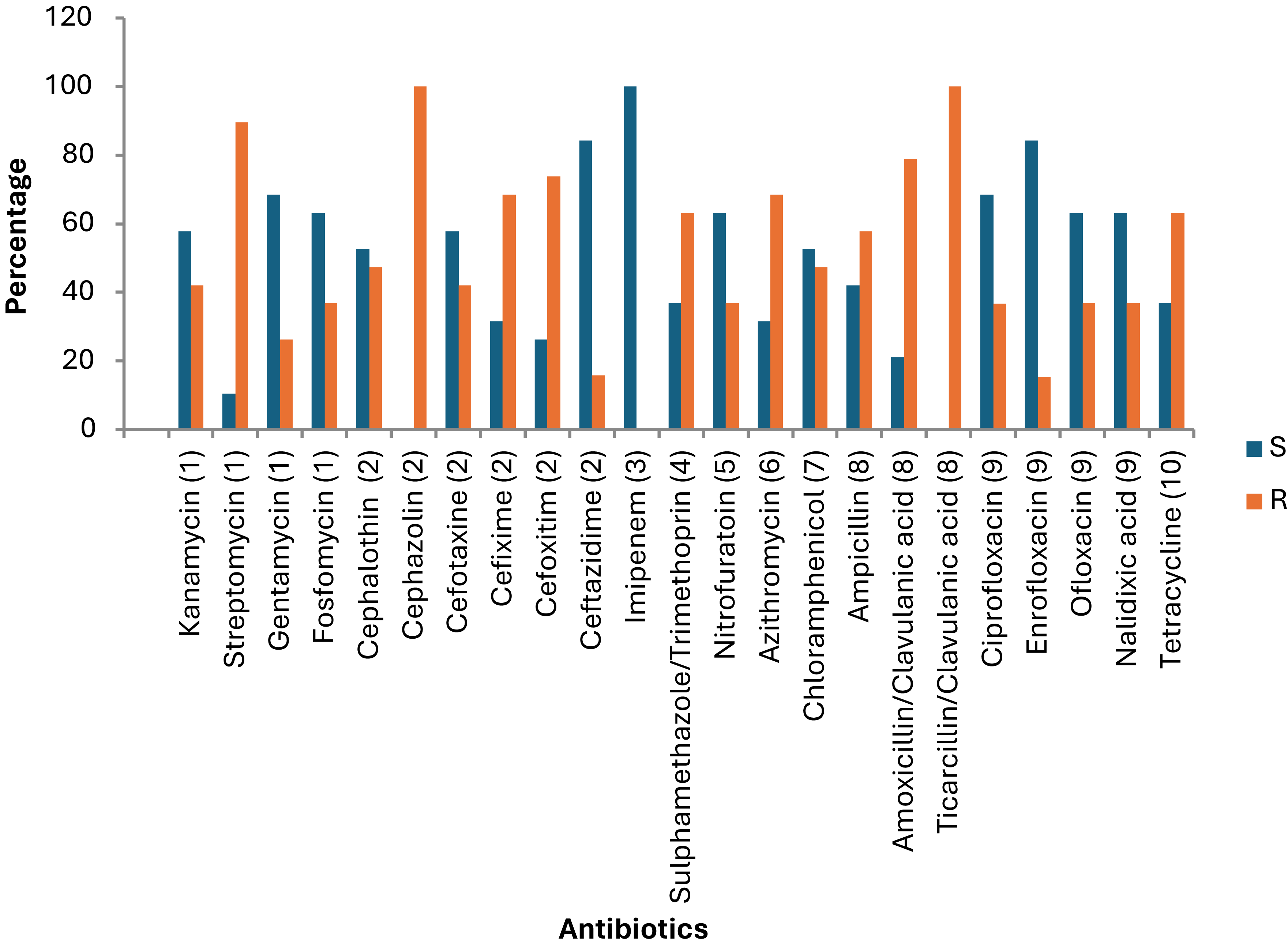

The antimicrobial susceptibility profile of E. coli and Klebsiella isolates from rats and chickens in this study reveals widespread multidrug resistance (MDR), with notable resistance to commonly used antibiotics such as streptomycin, fosfomycin, multiple generations of cephalosporins (e.g., cephalothin, cefotaxime, cefixime), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, tetracycline, and beta-lactams including amoxicillin-clavulanate and ticarcillin-clavulanate (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Percentage sensitivity of Salmonella isolates to 23 different antibiotics. S = sensitive, R = resistances. The Y-axis represents the percentage of isolates. (1) Aminoglycosides, (2) Cephalosporins, (3) Carbapenems, (4) Folate pathway inhibitors, (5) Nitrofuran derivatives, (6) Macrolide, (7) Phenicols, (8) Penicillin, (9) Quinolones, (10) Tetracyclines.

Discussion

The isolation of these resistant bacteria from both rats and chickens suggests significant environmental circulation and cross-species transmission, particularly in farm settings where poultry and dairy cattle are housed in close proximity (Leonard & Markey, Reference Leonard and Markey2008). Such proximity facilitates microbial exchange via shared water sources, feeding areas, equipment, and personnel, promoting HGT and the spread of AMR (Woolhouse et al., Reference Woolhouse, Ward, van Bunnik and Farrar2015; Nhung et al., Reference Nhung, Cuong, Thwaites and Carrique-Mas2017). The detection of resistance to high-priority antibiotics like ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime, and ceftazidime is especially concerning, as these are critical in human medicine and often used to treat severe infections (WHO, 2019). This situation is further exacerbated in developing countries where informal farming systems dominate, and antimicrobial use is often unregulated (Van Boeckel et al., Reference Van Boeckel2015). The convergence of MDR bacteria in both poultry and potential dairy environments raises significant food safety concerns, particularly given the risk of milk and poultry meat contamination. Thus, this study underscores the urgent need for improved biosecurity, spatial separation of livestock species, regulation of antibiotic use, and comprehensive AMR surveillance in integrated livestock systems to safeguard public health through a One Health approach (FAO, 2016; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson2016).

Rationale for including poultry environments

The inclusion of bacterial isolates from poultry environments can be justified under a One Health framework, particularly in integrated farm settings where cows and poultry cohabitate or share water, feed, or space. This co-existence can facilitate the interspecies transfer of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) bacteria or genes, especially via the environment (soil, water, rodents, and farm workers).

Risk factors associated with contamination

The findings of this study reveal significant associations between contamination levels in milk and a variety of vendor and environmental practices. Notably, infrequent handwashing, absence of protective clothing, and milking activities conducted near waste disposal sites were strongly linked to elevated levels of microbial contamination in milk. These risk factors reflect broader challenges in hygienic milk handling, especially within informal dairy sectors in developing countries. identified several key risk factors significantly associated with microbial contamination in dairy products and the prevalence of MDR bacteria in integrated farm environments. Poor hygiene practices among milk vendors and farmworkers such as infrequent handwashing, absence of protective clothing and the proximity of milking areas to waste dumps or animal feces were strongly correlated with elevated levels of coliform contamination in fresh and fermented milk. These findings are consistent with earlier reports that link inadequate personal hygiene and unsanitary production environments with increased microbial load in dairy products (Sarkar, Reference Sarkar2015a; Addis et al., Reference Addis, Pal and Kyule2011; Oliver et al., Reference Oliver2005).

Vendor hygiene and environmental contamination

Hand hygiene is a critical barrier in preventing the transmission of pathogens during milking, handling, and selling processes. Infrequent handwashing has been linked to higher rates of E. coli and Salmonella contamination in raw milk in several low- and middle-income countries (Karimuribo et al., Reference Karimuribo2017). Similarly, the absence of protective gear (such as gloves and aprons) during milking and handling activities can introduce bacteria from the skin and clothing into milk containers, especially when milking is done manually (Kang’ethe et al., Reference Kang’ethe2000).

Moreover, environmental proximity to waste disposal areas, stagnant water, and poultry housing increases the risk of cross-contamination. Waste materials serve as reservoirs for fecal coliforms and MDR bacteria, which may contaminate the milk either directly or through vectors like rodents and flies (Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa2014).

Hand hygiene remains one of the most critical practices in preventing the transfer of pathogens during milking and post-harvest handling. Infrequent or improper handwashing among milk handlers can facilitate the transmission of fecal and environmental bacteria, including E. coli and Salmonella, directly into milk (Sarkar, Reference Sarkar2015a; Addis et al., Reference Addis, Pal and Kyule2011). Similarly, the lack of protective clothing, such as gloves and aprons, further increases the likelihood of contamination, particularly when handlers come into contact with animal waste or dirty equipment (Fadaei, Reference Fadaei2014). In a study conducted in Tanzania, Mdegela et al. (Reference Mdegela2011) reported that poor personal hygiene and unhygienic milking environments were significantly associated with bacterial contamination in milk.

The proximity of milking areas to waste dumps, animal dung, or poultry houses serves as a major risk factor, as it creates an environment conducive to the presence and transfer of coliforms and other pathogenic bacteria into the milk supply. Airborne transmission, contaminated surfaces, and shared water sources can all contribute to this pathway (Mhone et al., Reference Mhone2011).

Furthermore, the inclusion of data from poultry environments in this study underscores the amplifying role of frequent antibiotic use in poultry production. Farms where antibiotics are regularly administered either prophylactically or for growth promotion tend to harbor higher concentrations of MDR strains, particularly Klebsiella and E. coli, in both litter and feces. These bacteria can persist in the environment and potentially contaminate nearby dairy facilities through vectors such as rodents, flies, and contaminated water (Leonard et al., Reference Leonard2011; Manyi-Loh et al., Reference Manyi-Loh2018).

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) between bacteria from poultry and dairy environments – facilitated by mobile genetic elements such as plasmids has also been well documented in integrated farms. These interactions increase the risk of spreading resistance genes, including those conferring resistance to critical antibiotics like third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones (Carattoli, Reference Carattoli2013; Allen et al., Reference Allen2010). The detection of ESBL-producing bacteria in both milk and poultry environments in this study further supports these findings.

Role of poultry antibiotic practices

The study also found a higher prevalence of MDR bacterial strains in poultry environments where antibiotics were frequently administered, often without veterinary supervision. This finding supports global evidence that the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials in poultry especially for prophylaxis and growth promotion exerts selective pressure that fosters resistance in both commensal and pathogenic bacteria (Van Boeckel et al., Reference Van Boeckel2015; Marshall & Levy, Reference Marshall and Levy2011). These resistant bacteria, or their genes, can be transferred to other animal species or humans through direct contact, contaminated water sources, or shared farm infrastructure (Nhung et al., Reference Nhung2016; Manyi-Loh et al., Reference Manyi-Loh2018).

Additionally, integrated farming systems, where poultry and dairy animals share water troughs, feeding areas, or manure disposal zones, provide a unique ecological niche for HGT among bacterial populations (Carattoli, Reference Carattoli2013; Allen et al., Reference Allen2010). This interconnection elevates the risk of coliforms acquiring resistance genes, including those for ESBLs, which compromise the efficacy of critical antibiotics such as cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones (Ezenduka et al., Reference Ezenduka2020).

Risk factor analysis

These risk factors both behavioral (e.g., hygiene practices) and systemic (e.g., antibiotic misuse) highlight critical control points for intervention. Strategies to mitigate contamination and AMR spread must therefore include:

-

Training of milk vendors and handlers on hygiene and safe handling.

-

Enforcement of biosecurity measures around waste management and farm layout.

-

Strict regulation of antimicrobial use in both dairy and poultry systems.

-

Routine surveillance of resistance trends in integrated farming environments.

-

Hygiene education and training for milk vendors and farmworkers.

-

Provision and enforcement of protective clothing during milking and processing.

-

Spatial reorganization of farms to separate dairy activities from waste disposal and poultry housing.

-

Strict regulation and monitoring of antimicrobial usage in poultry production

Furthermore these findings of this study reveal an alarming level of coliform contamination and MDR bacterial presence in milk samples collected from Minna, Niger State 68.8% in fresh milk and a staggering 98.1% in fermented milk. These results align with previous research across Sub-Saharan Africa, highlighting microbial hazards associated with informal dairy markets where pasteurization is either absent or poorly implemented, and hygiene practices are often inadequate (Musoke et al., Reference Musoke, Kansiime and Muhumuza2023; Omore et al., Reference Omore2021).

An important and often overlooked factor contributing to such contamination is the spatial proximity of dairy farms to poultry houses. In many rural and peri-urban farming systems, co-location of dairy and poultry units is common due to shared resources such as water, feed storage areas, and workers. This proximity provides a conduit for cross-contamination between the two environments. For instance, poultry droppings which are rich in coliforms and other enteric pathogens can contaminate water sources, milking equipment, or even the hides and udders of dairy cattle, especially in farms lacking proper biosecurity protocols.

Moreover, the microbial exchange between these two production systems poses a significant risk for the horizontal transfer of ARGs. Bacteria such as E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and C. murliniae found in the milk samples are not only common in dairy environments but also frequently isolated from poultry. These organisms are capable of acquiring and exchanging plasmid-mediated resistance genes, especially in environments with heavy antimicrobial use, as is often reported in poultry production for growth promotion and disease prevention.

This genetic interplay is facilitated when bacteria from both sources come into contact through shared environments or equipment, promoting the emergence of MDR strains. For instance, E. coli strains isolated from poultry have been shown to carry resistance determinants that can be transferred to human pathogens or those found in other animals, including cattle (Tadesse et al., Reference Tadesse, Abebe and Melesse2020). This scenario is particularly concerning in informal farming settings where antimicrobial stewardship is minimal and surveillance of resistance patterns is lacking.

In conclusion, the high contamination rates in milk samples are not only a function of poor hygiene and processing conditions but may also be exacerbated by cross-contamination and genetic exchanges between microbial populations in co-located poultry and dairy systems. This underscores the urgent need for integrated farm management practices, improved spatial planning, and strict biosecurity measures to mitigate the risks of zoonotic pathogen transmission and the spread of AMR.

Antimicrobial resistance patterns

The MDR profiles observed, particularly in Salmonella isolates, highlight significant concerns in AMR in dairy production, with 92% of Salmonella isolates showing a multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index above 0.2. The MAR index values, which indicate high-level antibiotic exposure, suggest an environment where indiscriminate antibiotic use is common, fostering conditions that favor the survival and transmission of MDR pathogens (Anyanwu et al., Reference Anyanwu, Okwori, Ogbondeminu and Nwankwo2023). Similar trends have been observed globally, where pathogens resistant to third-generation cephalosporins such as cefixime and cefotaxime, which are crucial for treating human infections pose challenges to both food safety and public health (Kirschke et al., Reference Kirschke, Grunert and Wiegand2022). This resistance indicates that effective treatment options are narrowing, increasing the risk of transmission through dairy products. The prevalence of resistance among milk-derived isolates suggests an urgent need for antibiotic stewardship programs in animal agriculture to mitigate AMR emergence in food systems (González-Acuña et al., Reference González-Acuña2021).

The use of ESBL screening, particularly for genes like blaTEM and blaSHV, further confirms the adaptability of these pathogens. ESBL-producing Salmonella and E. coli strains, which can resist broad-spectrum beta-lactams, complicate treatment options for foodborne infections (Kebede et al., Reference Kebede2023). This study’s results are consistent with research highlighting the rapid adaptation of bacteria in response to heavy antibiotic use, underscoring the public health risks associated with antibiotic residues and their selective pressure on microbial populations.

PCR detection of virulence and resistance genes

The detection of invA, a virulence gene specific to Salmonella, alongside the blaTEM and blaSHV beta-lactamase genes, underscores the dual threat posed by these pathogens: they are both virulent and resistant to multiple drug classes. The invA gene is widely recognized as a virulence marker in Salmonella spp., as it contributes to the pathogen’s invasive capability in host cells (González-Acuña et al., Reference González-Acuña2021). This virulence, combined with ESBL-producing beta-lactamase genes, presents a heightened challenge for treatment since the isolates are resistant to several classes of antibiotics, including cephalosporins and carbapenems, essential for treating severe infections (Tadesse et al., Reference Tadesse, Abebe and Melesse2020). This co-occurrence of virulence and resistance factors is a concern echoed by studies that report the spread of such traits from agricultural environments to human populations, potentially resulting in infections that are difficult to treat and contain (Anyanwu et al., Reference Anyanwu, Okwori, Ogbondeminu and Nwankwo2023).

Public health implications

The findings of this study reveal significant risks associated with MDR coliform bacteria in milk, suggesting potential transmission routes to humans either through direct consumption or through environmental exposure during milk handling and distribution. Infections caused by MDR pathogens in dairy products pose a dual threat: direct infection and indirect spread, especially in regions where milk is often unpasteurized and handled under informal, often unregulated, conditions (Omore et al., Reference Omore2021). The detection of the blaTEM and blaSHV genes within these isolates reflects a broader global concern regarding AMR, where resistance genes can be transferred between bacteria through HGT, further disseminating MDR traits (Kirschke et al., Reference Kirschke, Grunert and Wiegand2022).

Conclusion and impact statement

This study highlights the critical public health risk posed by coliform contamination and MDR bacteria in milk products from Minna, Niger State, particularly in contexts where dairy farms are situated in close proximity to poultry operations. The co-location of these animal production systems creates an enabling environment for cross-contamination and potential HGT between bacterial populations. Shared resources, such as water sources, feeding areas, and handling equipment, may facilitate the movement of pathogens and resistance genes from poultry to dairy cattle and vise versa.

The detection of MDR strains such as E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and C. murliniae in milk suggests not only poor hygienic practices during milking and processing but also raises concerns about the interspecies transmission of resistance determinants. In such environments, where antimicrobial agents are frequently used in both poultry and cattle without strict regulation, the risk of developing and disseminating resistant bacterial strains is amplified.

To mitigate these risks, integrated interventions are urgently needed. These should include:

-

Improved farm biosecurity to reduce contact between poultry and dairy units, including separate housing, designated personnel, and disinfection protocols;

-

Enhanced surveillance and regulation of antimicrobial use across livestock sectors to curb unnecessary exposure and selective pressure;

-

Targeted education and training for farmers and handlers on hygienic milking, proper waste disposal, and antimicrobial stewardship;

-

Routine monitoring of microbial contamination and resistance patterns in both dairy and poultry products to inform policy and response strategies.

Addressing these interlinked issues holistically, through a One Health approach, will not only improve milk and poultry safety but also play a pivotal role in slowing the spread of AMR, thereby safeguarding both animal and human health in the region.

Recommendations

The study’s findings underline an urgent need for implementing antimicrobial stewardship programs targeting dairy and poultry sectors to mitigate AMR spread. Enhanced hygiene protocols, particularly training for milk vendors on proper handling and storage practices, could significantly reduce coliform contamination rates (Kebede et al., Reference Kebede2023). Furthermore, instituting strict regulations on antibiotic usage in animal agriculture, as recommended by global health bodies, could help curb the selective pressure that fosters MDR bacteria in food systems. Recent research has shown that controlling antimicrobial use in animal farming, combined with effective waste management, can substantially reduce the spread of resistance in agricultural settings (Musoke et al., Reference Musoke, Kansiime and Muhumuza2023).

Finally, ongoing surveillance for AMR in the dairy and poultry sectors is critical for early detection of resistance trends and could serve as a cornerstone for effective public health responses. Surveillance not only aids in assessing the efficacy of interventions but also helps in identifying emerging resistance patterns that could impact treatment protocols for foodborne infections (Anyanwu et al., Reference Anyanwu, Okwori, Ogbondeminu and Nwankwo2023). This study provides crucial insights into the public health implications of AMR in dairy production, advocating for multifaceted intervention strategies that combine education, regulation, and surveillance to protect consumers and reduce the burden of MDR pathogens in food systems.

Improved Hygiene Practices: Vendor training on milk handling, along with regulations for proper storage and vendor health checks, is essential to reduce contamination rates.

Antimicrobial Stewardship: Reducing antibiotic use in poultry through alternative practices, such as probiotics, can limit the spread of MDR bacteria.

Surveillance Programs: Establishing surveillance for AMR in both dairy and poultry sectors is critical for early detection and response to emerging MDR pathogens.

Data availability statement

The raw data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to institutional and ethical restrictions. However, they can be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Africa Centre of Excellence for Mycotoxins and Food Safety, Niger State Government, and supporting institutions.

Author contributions

Contributions of Authors

Aliyu Evuti Haruna

Role: Principal Investigator

Contributions: Led the research design and methodology, coordinated the overall project, conducted data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Responsible for overseeing the research team and ensuring compliance with ethical standards.

Nasiru Usman Adabara

Role: Co-Investigator

Contributions: Assisted in the development of research protocols, contributed to data collection, and performed preliminary analyses. Actively participated in the interpretation of results and provided critical feedback on the manuscript.

Nma Bida Alhaji

Role: Research Assistant

Contributions: Conducted fieldwork and data collection, including surveys and experiments. Assisted in data entry and management, and provided logistical support during the research process.

Hajara Usman Sadiq

Role: Literature Review Specialist

Contributions: Conducted a comprehensive literature review, identifying relevant studies and summarizing findings. Assisted in framing the research questions and contextualizing the study within existing literature.

John Yisa Adama

Role: Quality Control Supervisor

Contributions: Ensured the accuracy and reliability of data collection processes. Reviewed data for inconsistencies and provided feedback to the research team to enhance data quality.

Hadiza Lami Muhammed

Role: Laboratory Technician

Contributions: Performed laboratory analyses related to the research, including sample preparation and testing. Assisted in maintaining laboratory equipment and ensuring compliance with safety protocols.

Hussaini Anthony Makun

Role: Research Collaborator

Contributions: Provided expertise in the specific subject matter of the research. Contributed to the discussion of results and helped refine the manuscript’s arguments and conclusions.

Financial support

This work was funded by the Africa Centre of Excellence for Mycotoxins and Food Safety, The Company of Biologists and the TETFund institution-based research fund at the Federal University of Technology, Minna.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethics approval (approval number MLF/2024/026) from the Committee on Animal Use and Care of the Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries in Niger State, Nigeria. Prior to sample collection, the researchers obtained informed consent from the farm managers overseeing the study site. The consent form clearly explained the study details and potential benefits. The farm managers voluntarily signed the form, agreeing to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant Institutional Review Boards, and informed consent was gathered from all vendors and farm owners participating in this study.

Author Biography

Dr. Aliyu Evuti Haruna is a veterinary epidemiologist/one-health researcher. He is affiliated with the Africa Centre of Excellence for Mycotoxin and Food Safety, Federal University of Technology, Minna (ACEMFS, FUTMinn). He also works with the Livestock Productivity and Resilience Support (L-PRES) Project, Niger State, Nigeria. According to his LinkedIn, he studied/is studying in veterinary epidemiology. On the Global One Health Community site: he earned a DVM from Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria; got a MacArthur Foundation Scholarship for a Master’s in Veterinary Epidemiology; and has experience in disease outbreak investigations and reporting. On ResearchGate: his work includes antimicrobial resistance, pesticide residues, and One Health.

Nma Bida Alhaji (DVM, PhD) works at ACEMFS, FUTMinna. According to ResearchGate, her research interests include molecular & field epidemiology of infectious diseases, antimicrobial resistance, zoonoses, One Health, and animal health economics. On a CBPP (contagious bovine pleuropneumonia) flyer/document, she is listed as “Dr. Nma Bida Alhaji (DVM, PhD) FCVSN” from ACEMFS, pointing to her role in field epidemiology.

Hajara Usman Sadiq is affiliated with Africa Centre of Excellence for Mycotoxin and Food Safety, FUTMinna.

John Yisa Adama is affiliated with ACEMFS, FUTMinna.

Hadiza Lami Muhammed is affiliated with ACEMFS, FUTMinna. In ACEMFS’s “About Us” page, Prof. H. L. Muhammed appears as the Deputy Centre Leader of the centre. This suggests she is senior in research and leadership in mycotoxin/food safety at FUTMinna.

Hussaini Anthony Makun is affiliated with ACEMFS, FUTMinna. From ACEMFS website: Prof. Hussaini Anthony Makun is the Centre Leader of the Africa Centre of Excellence for Mycotoxin and Food Safety. Per ACEMFS, he is a Professor (Biochemistry/Toxicology) and leads the centre.

Comments

No accompanying comment.