Management Implications

Public gardens and arboreta are uniquely positioned to reduce the time, effort, and high cost surrounding invasive plant management by helping to identify problematic species well before they become established in natural areas. With their botanical expertise and constant surveillance of species within their collections, gardens can act as sentinels, watching for plants escaping cultivation to prevent their subsequent introduction more widely in the trade. Gardens have been dealing with species spreading from cultivation within their collections for decades and, in some cases, are already removing these species. Previously, such expertise and knowledge were not typically shared even within the garden community, often for fear of blame. Now, however, the Public Gardens as Sentinels against Invasive Plants (PGSIP) database and the associated guidelines enable participating gardens to share this information with one another. These data can inform garden management plans by determining which species to remove from collections to prevent spread, help gardens educate the public, and shape the development of horticultural cultivars.

This garden-based information is also being shared more widely through PGSIP Plant Alerts, presentations, and publications so that researchers, botanists, land managers, landscape architects and designers, agencies tasked with invasive plant assessment and regulation, and the horticultural industry will be more aware of spread potential for reported species. Such advance notice may also help keep potentially invasive ornamentals from initially entering the nursery trade and encourage the timely development of alternatives. Ultimately, this information will allow land managers to identify and target new arrivals and small satellite populations on their properties to minimize control costs and prevent large-scale invasions of these plants.

Introduction

One of the biggest challenges for invasive species management is to quickly and aggressively treat problematic species as early as possible to minimize detrimental impacts to the natural environment. Early detection and removal would also greatly minimize management and control costs (Diagne et al. Reference Diagne, Leroy, Vaissière, Gozlan, Roiz, Jarić, Salles, Bradshaw and Courchamp2021), estimated at more than US$190 billion from 1960 to 2020 for invasive plants in the United States alone (Fantle-Lepczyk et al. Reference Fantle-Lepczyk, Haubrock, Kramer, Cuthbert, Turbelin, Crystal-Ornelas, Diagne and Courchamp2022). If given advance warning, land managers could be on the alert for potential invaders and quickly eradicate single individuals or new satellite populations, well before they develop into large infestations (Lieurance et al. Reference Lieurance, Culley, Brant, Canavan, Daehler, Evans and Keller2024). Early notification of potential spread would also benefit state-based agencies and invasive plant councils that create regulated and educational lists (e.g., Buerger et al. Reference Buerger, Howe, Jacquart, Chandler, Culley, Evans, Kearns, Schultzi and van Riper2016). The horticultural industry could also potentially save years of wasted effort and maximize their financial investments by pivoting away from developing potential invaders and focus instead on noninvasive alternatives.

Early detection of invasive species requires a predictive approach, which by its very nature involves some uncertainty. To better predict species with a propensity to become invasive over time, scientists have scoured the literature to identify traits associated with invasion, such as biotic or wind pollination, high seed production, long-distance seed dispersal by wind or birds, growth habit, or membership in certain plant families or genera (e.g., Conser et al. Reference Conser, Seebacher, Fujino, Reichard and DiTomaso2015; Jefferson et al. Reference Jefferson, Havens and Ault2004; Kuester et al. Reference Kuester, Conner, Culley and Baucom2014; Nunez-Mir et al. Reference Nunez-Mir, Guo, Rejmánek, Iannone and Fei2019). Some countries and U.S. states have incorporated these traits to develop predictive approaches in their weed risk or invasive plant assessments (such as spread in similar growing zones) or they integrate horizon scans (Lieurance et al. Reference Lieurance, Culley, Brant, Canavan, Daehler, Evans and Keller2024). There are also predictive tools to identify locations where plants may be more likely to spread and shift their future ranges, especially under climate change (Allen and Bradley Reference Allen and Bradley2016; Evans et al. Reference Evans, Jarnevich, Beaury, Engelstad, Teich, LaRoe and Bradley2024). Several public gardens even use a formal risk assessment to evaluate non-native species before they are added to their collection or to evaluate non-natives already in the collection. However, there is always the chance that a non-native species preemptively restricted before it enters a location may never have become invasive in the first place. Alternatively, some non-native species may be assessed individually as “safe” (e.g., considered sterile or a low seed producer) but in actuality could spread under certain conditions, such as cross-pollination among genetically different cultivars (Culley Reference Culley2017), increased seed set with greater plant age (Lehrer et al. Reference Lehrer, Brand and Lubell2006; Madeja et al. Reference Madeja, Umek and Havens2012), or multiple introductions associated with commercial sale and distribution (Beaury et al. Reference Beaury, Allen, Evans, Fertakos, Pfadenhauer and Bradley2023).

Unbeknownst to most land managers and invasion biologists, many public gardens have been carefully monitoring their collections of non-native species for decades (Hulme Reference Hulme2011), sometimes even recording spread and removing those species (known as “deaccessioning”). Gardens and arboreta are conservation-based institutions that house plant collections representing much of the world’s flora, used to educate the public. Garden staff often maintain records of the provenance of each individual plant within their collection, its health over time, and information regarding its decline or removal. This may also include notes on deaccessioning if a plant spreads from cultivation through vegetative growth or if its offspring are found to escape cultivation. Some gardens and arboreta also have their own internal watch or invasive lists, which include species or cultivars being monitored for spread or those already removed because they were deemed problematic. For example, 91% of respondents in a 2016 survey of 35 gardens across North America (Dreisilker et al. Reference Dreisilker, Ryan, Culley and Arcate Schuler2019) had observed plants escaping cultivation, and 89% were already controlling non-native species spreading from cultivation. In addition, public gardens may also curate a mix of related species or cultivars of a single species, creating conditions under which cross-pollination, enhanced seed production, and subsequent spread may be more likely. However, public gardens and arboreta have not historically shared this information with one another or anyone else, often for fear of being blamed as the source of an invasive outbreak (Culley et al. Reference Culley, Dreisilker, Ryan, Arcate Schuler, Cavallin, Gettig, Havens, Landel and Shultz2022; Dreisilker et al. Reference Dreisilker, Ryan, Culley and Arcate Schuler2019; Hulme Reference Hulme2011). Yet this information collected by gardens would be invaluable in potentially identifying non-native species most at risk of invasive spread, before they actually do spread.

In 2016, an effort was begun to enhance communication among public gardens in North America and to share information regarding plants escaping cultivation. Known as Public Gardens as Sentinels against Invasive Plants (PGSIP), the network was formally launched in 2018 as a collaboration between the Midwest Invasive Plant Network (MIPN) and the Morton Arboretum. Early on, PGSIP discovered that many gardens gathered valuable data on problematic plants, but with little standardization across methods. In the initial analysis of data from seven gardens that voluntarily contributed their lists (Culley et al. Reference Culley, Dreisilker, Ryan, Arcate Schuler, Cavallin, Gettig, Havens, Landel and Shultz2022), 769 species were reported as problematic to various degrees. Eight woody species were listed by all the gardens, and several of these species were not always recognized as invasive by the states or provinces in which the gardens were found (Supplementary Data). Some gardens included species that had originated outside the garden, while others did not, and gardens often had their own unique categories of concern, making it difficult to compare across institutions. A few gardens also listed problematic cultivars, while other gardens treated all cultivars as invasive if the species itself was considered invasive, unless the cultivars themselves were demonstrated to be sterile. Of all species identified by the gardens as problematic, 77% did not appear on any state or province invasive plant list—hence the sentinel nature of the project. Even with unstandardized data, Culley et al. (Reference Culley, Dreisilker, Ryan, Arcate Schuler, Cavallin, Gettig, Havens, Landel and Shultz2022) demonstrated that when garden observations are compiled together and compared within a geographic area, patterns emerge that suggest certain species are at risk of spreading.

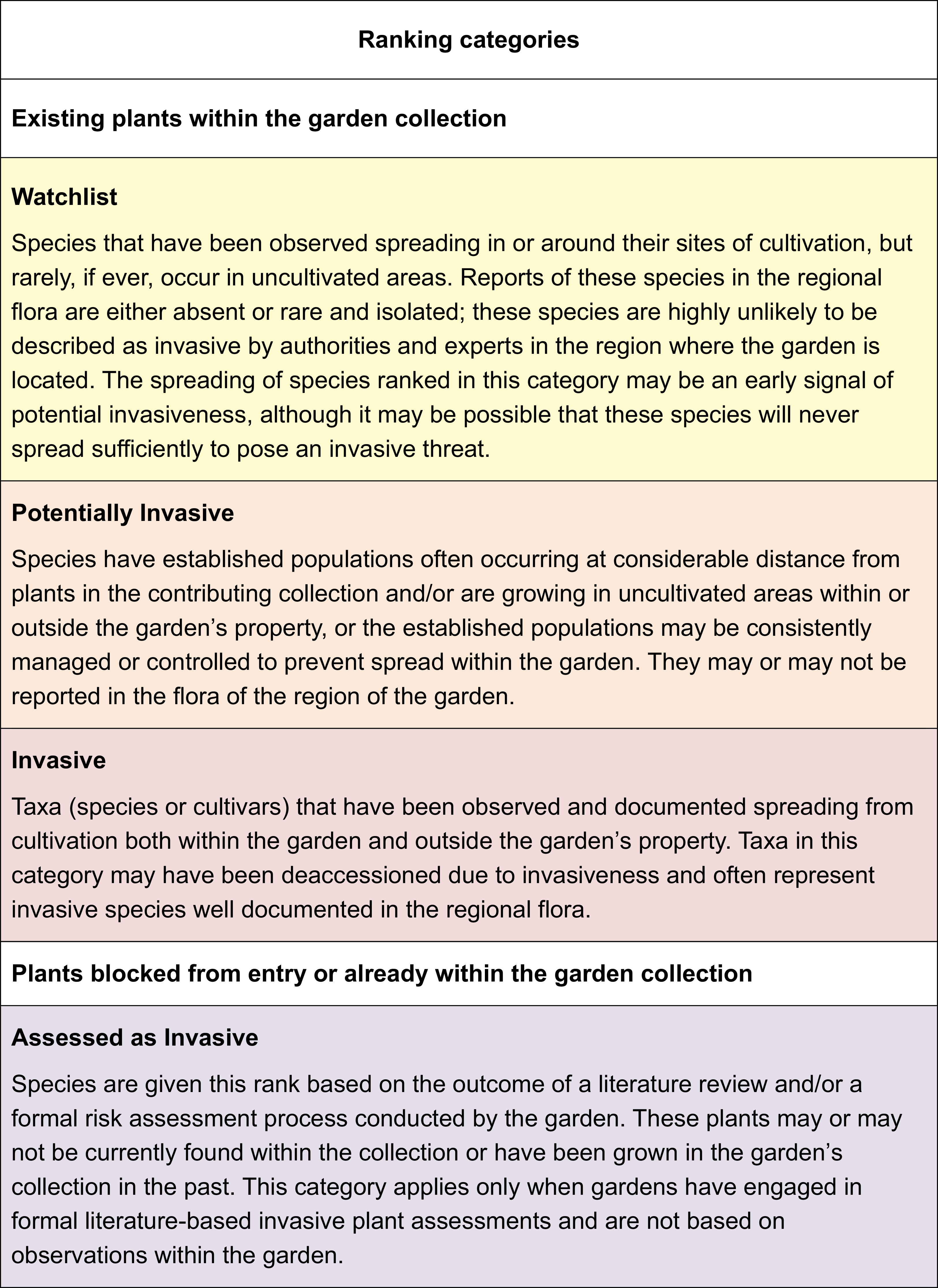

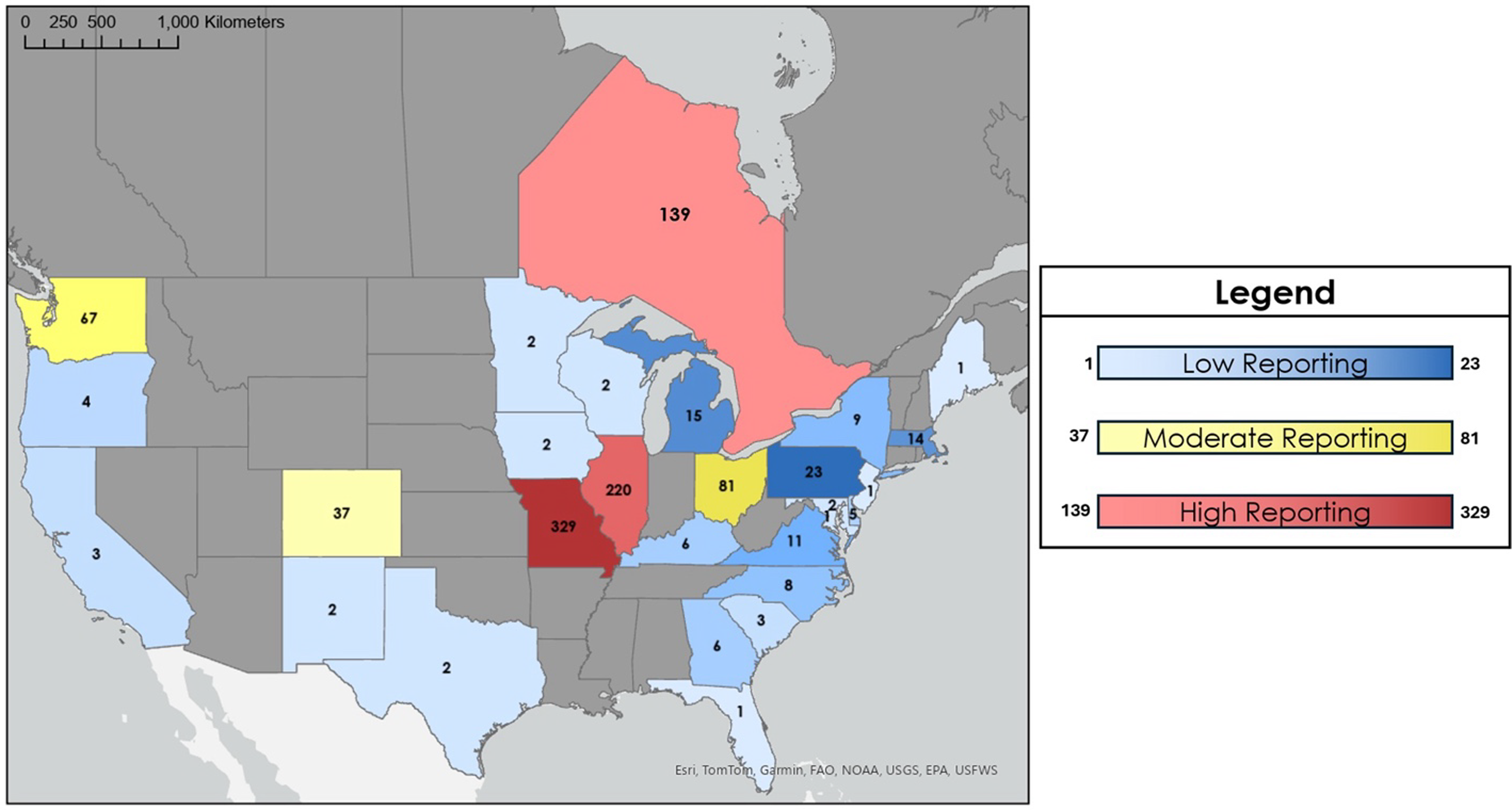

Additional gardens then became interested in contributing their own existing data, or wanted to participate but had not yet collected any information. Consequently, a shared PGSIP database was created for gardens to upload and store their data, as well as guidelines to standardize the collection and reporting of this information (Dreisilker et al. Reference Dreisilker, Ryan, Cavalin, Shultz, Culley, Landel, Gettig and Arcate Schuler2021). The guidelines directed gardens to designate their plants of concern into four categories: (1) Invasive; (2) Potentially Invasive; (3) Watchlist; and (4) Assessed as Invasive (Figure 1). Plants designated as Invasive are typically removed from the living collection and deaccessioned by the gardens. The first three categories are observation based and pertain to plant species present in the past or current living collections, while the last category also includes species blocked from entry into the garden based on an internal formal assessment. Each garden can update its records in the database with a new revised entry and ranking. Species that were never purposely planted in the gardens but migrated from elsewhere are usually not included in the database. The PGSIP effort has now grown from the initial handful of gardens in the U.S. Midwest and Canada to 53 gardens across North America as of late 2024. These sentinel gardens are located in 26 U.S. states, one U.S. District, and one Canadian province (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Categories used for ranking problematic plants by the Public Gardens as Sentinels against Invasive Plants (PGSIP) garden network.

Figure 2. Distribution of 996 reports of problematic species identified within gardens within each U.S. state and Canadian province, as classified according to the Public Gardens as Sentinels against Invasive Plants (PGSIP) gardens. Increasing numbers of reports per state are indicated in blue (low), yellow (moderate), and red (high reporting).

The purpose of this paper is to examine the database and update the previous analysis (Culley et al. Reference Culley, Dreisilker, Ryan, Arcate Schuler, Cavallin, Gettig, Havens, Landel and Shultz2022), taking advantage of the new standardized data, as well as the sharp increase in the number of public gardens participating in the PGSIP network across North America. To demonstrate the utility of the PGSIP database, garden data were used to identify species that the participating gardens reported as problematic, and then to determine whether these same species have also been reported outside gardens (i.e., classified as state-listed invasive plants, noxious weeds, or regulated species). The database was also used to identify which emerging species might be at greatest risk for spreading, particularly within regions of North America, and what characteristics might be shared among these species.

Materials and Methods

Data Compilation

The dataset was derived from the PGSIP database, downloaded from the online platform (https://pgsip.mortonarb.org/Bol/pgsip) on August 19, 2024, and then revised on November 24 following contributions by several newly participating gardens and updates by one garden. Each entry in the dataset represents the submission of one observation from a garden of a single species (sometimes with a variety or cultivar name) and includes the name of the garden, the standardized ranking attributed by the garden (Invasive, Potentially Invasive, Watchlist, Assessed as Invasive), and the garden’s state or province. Because some gardens requested that their association with particular data be kept confidential, the PGSIP database is only available to staff at participating gardens.

The total dataset consisted of 996 entries uploaded by the 53 PGSIP gardens in 26 U.S. states, one Canadian province, and the District of Columbia (DC; hereafter considered a “state”) (Figure 2). To create a dataset that represented unique species and their associated rankings, we condensed multiple entries of the same species by summing the number of gardens that classified the same species into each of the four rankings. In one case, a garden had updated a previously entered ranking of the same species (elecampane [Inula helenium L.], changed from “Assessed as Invasive” to “Invasive”). In five other cases, both a species and one or more cultivars of that species were listed by the same institution, usually with the same ranking; this was collapsed into one entry per garden. For one case in which a garden listed a species and its cultivar in different problematic categories (ground elder [Aegopodium podagraria L.] was “Assessed as Invasive” but its cultivar ‘Variegatus’ was considered “Invasive”), the species was included as “Invasive” in the condensed dataset. There were also five cases in which multiple synonymous species were condensed into a single species according to USDA PLANTS database (USDA-NRCS 2024). For example, spotted knapweed was listed separately by one garden as Centaurea stoebe L. and C. biebersteinii DC., but is now considered the same species. Within the final dataset, there were also 52 species reported by gardens that were not present in the USDA PLANTS database, presumably because they were not previously reported to be present in the United States (but they do exist within garden collections). Based on these modifications, the full dataset was reduced to 597 unique species listed by gardens as of concern within their properties.

The common name and the plant family to which the species belonged were then added to the dataset using the USDA Complete PLANTS Checklist download file (https://plants.usda.gov/downloads), by matching the species name in the dataset with the USDA symbol code. In some cases, the names of some species contributed by the gardens were changed to match the nomenclature of that taxon in the USDA PLANTS database. For example, a few gardens listed Amur maple as Acer tartaricum subsp. ginnala (Maxim.) Wesm., but it is recognized by the USDA as Acer ginnala Maxim.; similarly, Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica Houtt.) was used by some gardens, but it is listed by the USDA under its older name, Polygonum cuspidatum Siebold & Zucc. If a species was not listed in the USDA PLANTS database, its common name and plant family were identified using the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF; https://www.gbif.org).

Growth habit type was also determined for each reported species as tree, shrub, subshrub, vine, forb/herb, or graminoid, using the growth habit search function in the USDA PLANTS database (https://plants.usda.gov/growth-habit-search). Each growth habit dataset was individually downloaded from USDA PLANTS on November 7, 2024, and then matched against each species in the garden dataset, based on the USDA symbol code. In some cases, a given species was listed in more than one USDA growth habit dataset; for example, sapphire-berry [Symplocos paniculata (Thunb.) Miq.] was listed as both a tree and shrub. In these cases, the species was assigned to a single growth habit based on an internet search and the expert opinion of our team. Grasses and other graminoids (including sedges and rushes) were analyzed separately from other herbs due in part to their frequent inclusion as invasive species. Because the subshrub category was considered vaguely defined (“low-growing shrub usually under 0.5 m tall, never exceeding 1 m at maturity” [PLANTS Help document]), the subshrub designation was revised to either shrub (if predominantly woody) or herb categories (primarily herbaceous growth), again based on expert opinion. Each species was then assigned to a general habit category of woody (trees and shrubs) or non-woody (herbs/forbs and graminoids). Vines were classified as either woody (e.g., Chinese wisteria [Wisteria sinensis (Sims) DC.]) or herbaceous (e.g., European swallow-wort [Cynanchum rossicum (Kleopow) Borhidi]) based on observed growth patterns.

To determine the likelihood of spread within areas of North America, each garden’s state or province was assigned to a region of North America, based on TDWG (Taxonomic Databases Working Group, also referred to as the Biodiversity Information Standards) regions designated by the International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Sciences (https://www.tdwg.org/standards/wgsrpd/). These are standard geographic units at approximately the “country” level for recording plant distributions globally. While TDWG regions encompass different habitat types and are not based on ecology, this criterion was used as a first approximation of potential geographic spread of a given taxon. For each species, the number of TDWG regions in which the species was reported by gardens as problematic was summed together. This value represents the geographic extent of any current problematic behavior. Each species was also identified as introduced or native to North America, using the USDA PLANTS database and, if necessary, the Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder website (http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/plantfinder/plantfindersearch.aspx) and GBIF (https://www.gbif.org).

As a way to better understand how often problematic species may exist within the collections of gardens more broadly, the frequency of each reported species held in collections of all public gardens in North America was calculated, using data obtained from Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) based on their Plant Search Tool (https://www.bgci.org/resources/bgci-databases/plantsearch/; BGCI 2024). In addition, we examined whether a species had been historically available through the ornamental trade by matching each taxon to the Historical Plant Sales database created by Fertakos et al. (Reference Fertakos, Beaury, Ford, Kinlock, Adams and Bradley2023) from digitized seed and nursery catalogs from 1890 to 1950. From this source, the number of times a particular species had appeared for sale in this catalog collection was extracted.

Status as Recognized Invasives

Each species in the PGSIP dataset was examined to determine whether it was already recognized as an invasive species or a noxious weed outside the garden community. The U.S. Federal Noxious Weed List (https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/weedlist.pdf) and the Canadian Regulated List (https://inspection.canada.ca/en/plant-health/invasive-species/invasive-plants/invasive-plants) were first used to identify whether species were listed as a federal noxious weed or invasive plant. To determine whether each species was included on a state- or province-based list of noxious weeds or a regulated or informational (i.e., non-regulated) list of invasive species, we used the comprehensive dataset compiled by MIPN (https://www.mipn.org/plantlist/; downloaded May 24, 2024) for the states of Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, as well as the Canadian province of Ontario. Because the PGSIP network has now expanded, we also added in 18 states containing other PGSIP gardens (California, Colorado, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Washington) by carefully reviewing the appropriate websites (Supplementary Data) and Beaury et al. (Reference Beaury, Fusco, Allen and Bradley2021a). The number of the 28 PGSIP-represented states/province that included the species on regulated or non-regulated lists was then counted per species. We also determined whether any of the 597 species had been previously reported as invasive in the scientific literature, using the Global Compendium of Invasive Plants database, constructed from peer-reviewed literature published between 1959 to 2020 (Laginhas and Bradley Reference Laginhas and Bradley2021).

Rankings

For each species, the number of gardens that ranked that species was summed to indicate the total number of PGSIP gardens that reported that species. Because multiple gardens sometimes assigned different rankings for the same species, an overall Index of Invasiveness was calculated for each species as the sum of the weighted number of entries for each ranking, whereby each ranking was weighted by a severity score of 1 to 4, with 4 being most severe; this value was then divided by the number of gardens that reported that species.

$$\eqalign{& {\rm Invasive \; Index} = [(n \; {\rm Invasive \; rankings})(4) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Potential \; Invasive \; rankings})(3) + (n \; {\rm Watchlist \; rankings})(2) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Assessed \; as \; Invasive \; rankings})(4)]/N \; {\rm reporting \; gardens}}$$

$$\eqalign{& {\rm Invasive \; Index} = [(n \; {\rm Invasive \; rankings})(4) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Potential \; Invasive \; rankings})(3) + (n \; {\rm Watchlist \; rankings})(2) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Assessed \; as \; Invasive \; rankings})(4)]/N \; {\rm reporting \; gardens}}$$

To capture species more likely to be overlooked or in earlier stages of spread within the sentinel PGSIP gardens, a second index was created for each species that places more relative weight on plants within the Watchlist category:

$$\eqalign{& {\rm Emerging \; Plant \; of \; Concern \; Index } = [(n \; {\rm Invasive \; rankings})(2) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Potential \; Invasive \; rankings})(3) + (n \; {\rm Watchlist \; rankings})(4) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Assessed \; as \; Invasive \; rankings})(2)]/N \; {\rm reporting \; gardens}}$$

$$\eqalign{& {\rm Emerging \; Plant \; of \; Concern \; Index } = [(n \; {\rm Invasive \; rankings})(2) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Potential \; Invasive \; rankings})(3) + (n \; {\rm Watchlist \; rankings})(4) \cr& + (n \; {\rm Assessed \; as \; Invasive \; rankings})(2)]/N \; {\rm reporting \; gardens}}$$

The ability of PGSIP gardens to accurately identify problematic species and, more importantly, to detect species in the earliest stages of spread was examined by comparing each index separately to (1) the number of states or provinces listing the reported species as invasive, noxious, or otherwise problematic; (2) the number of TDWG regions occupied by reporting gardens; and (3) the number of gardens themselves reporting the species. Using R v. 4.4.2 (R Core Team 2024), the relationship between each index and each of the three variables was then separately computed using a Spearman rank correlation, due to the nonnormally distributed data, as determined by a Shapiro-Wilk test.

The full dataset is provided in the Supplementary Data, anonymized by the contributing PGSIP gardens.

Results and Discussion

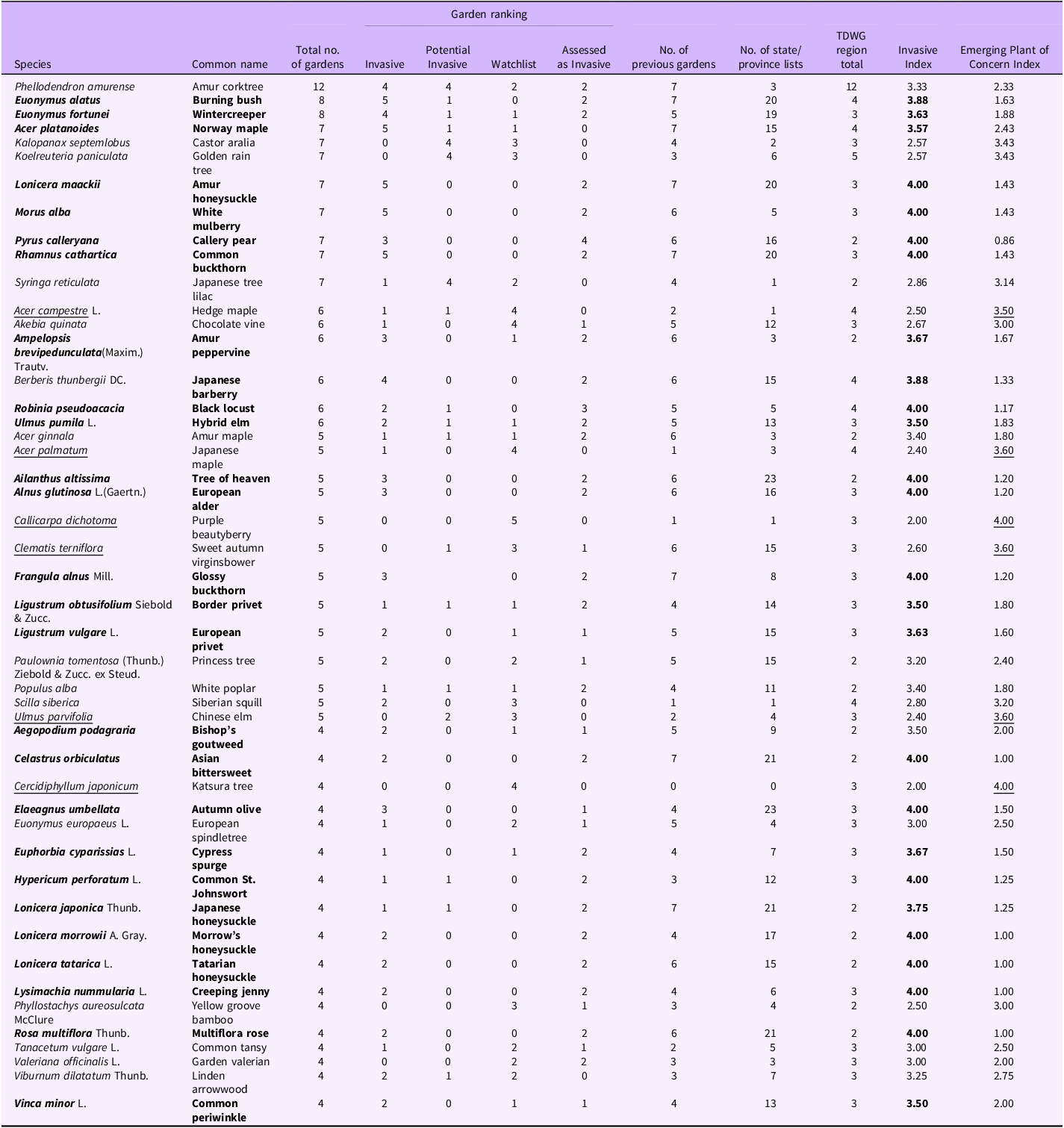

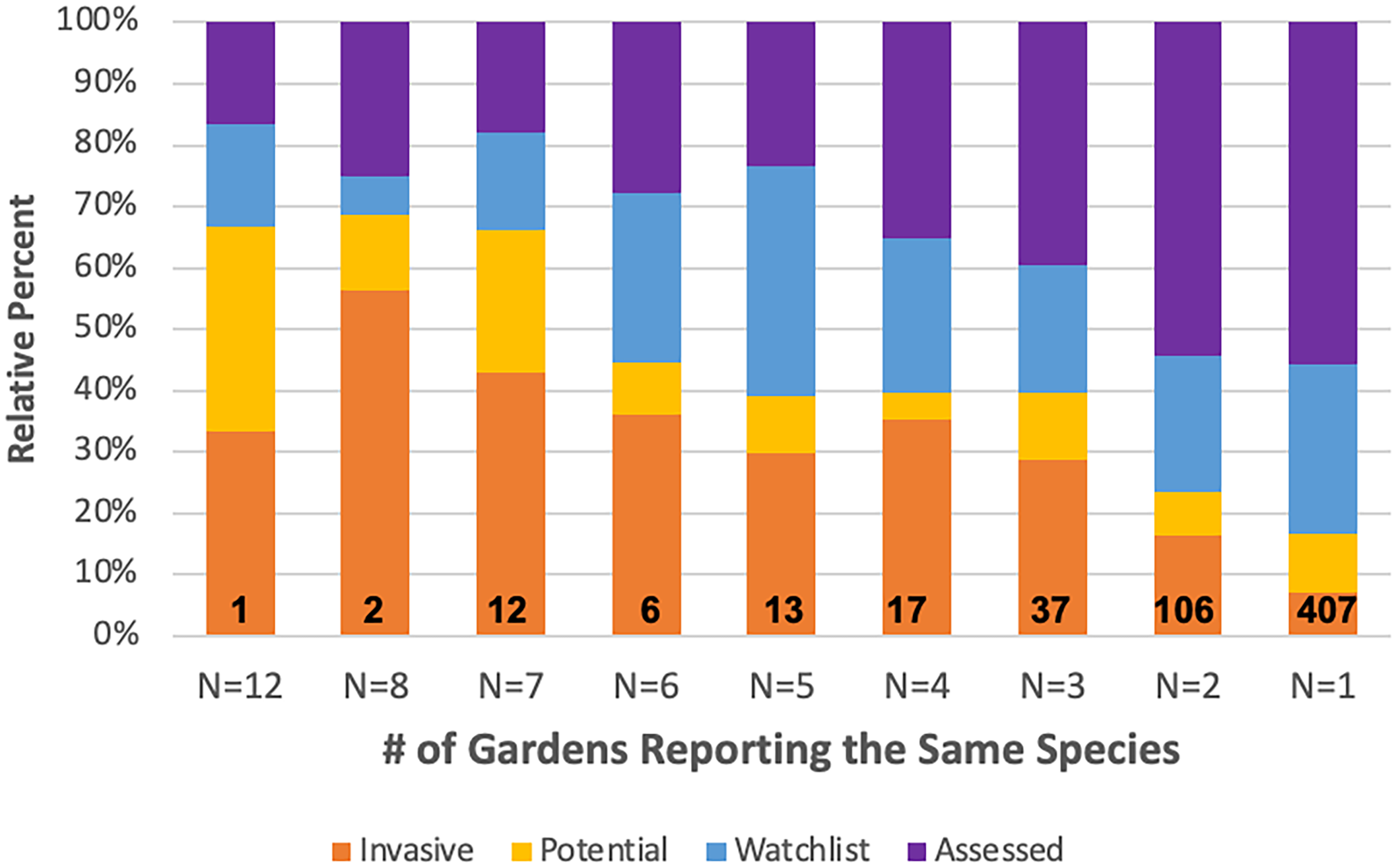

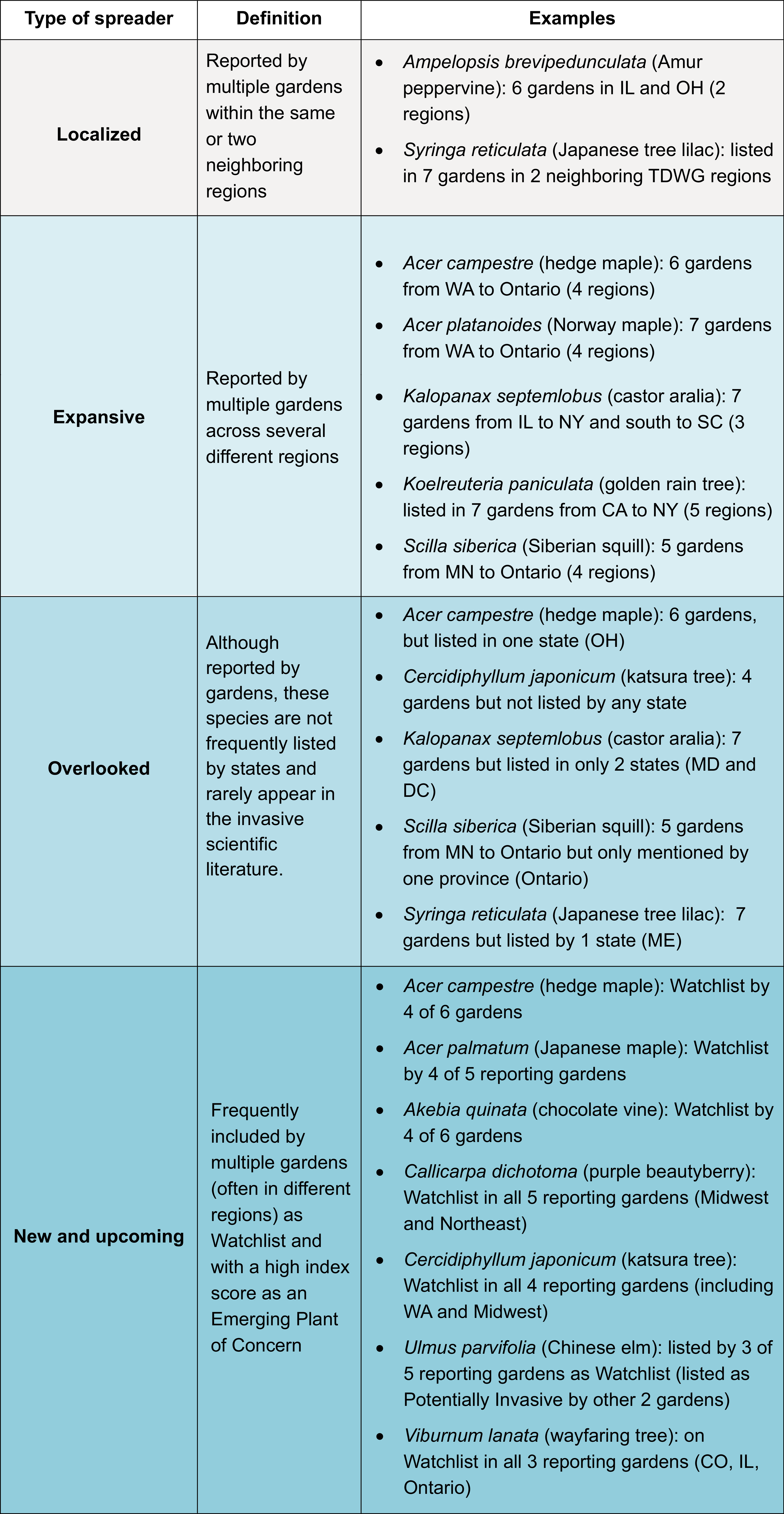

With their constant surveillance during routine maintenance, their botanical expertise, and the presence of many non-native species in their collections, public gardens and arboreta are uniquely positioned to act as sentinels, watching for plants escaping cultivation as harbingers of invasion. In many cases, multiple gardens had independently identified the same plant species (Table 1) already spreading from cultivation or are carefully watching the species’ behavior for possible escape within the living collection. For example, 32% (190 of 597) of species in the PGSIP database had been reported by more than one garden. The majority of these species (70%; n = 134) were reported as a combination of Invasive, Potentially Invasive, and/or Watchlist ranking categories (Figure 3). Plant species reported across multiple PGSIP gardens were also more likely to be recognized as Invasive or Noxious on state-based lists, albeit to varying degrees. For example, the most commonly listed species was Amur corktree (Phellodendron amurense Rupr.), reported by 12 gardens as Invasive (n = 4 gardens), Potentially Invasive (4), Watchlist (2), or Assessed as Invasive (2) (Table 1); but this species was only listed by 3 of 28 states and provinces. In contrast, wintercreeper [Euonymus fortunei (Turcz.) Hand.-Max.] and burning bush [Euonymus alatus (Thunb.) Siebold] were each reported by 8 gardens but were already recognized as invasive by 19 and 20 states, respectively.

Table 1. Species most often listed as problematic by at least four or more of Public Gardens as Sentinels against Invasive Plants (PGSIP) gardens as of November 2024 using the standardized guidelines. a

a Species are ranked according to the total number of gardens listing the same species. Shown are the number of reporting gardens that ranked each species in the four categories, the number of gardens that reported the species in 2022 (based on seven participating gardens), the number of states or province that lists the species as invasive, and the number of TDWG (Taxonomic Databases Working Group, also referred to as the Biodiversity Information Standards) regions in which the reporting gardens are found. Species with an Invasive Index of 3.50 or above are in bold, and species with an Emerging Plant of Concern Index of 3.50 or above are underlined.

Figure 3. The relative distribution of rankings assigned to species reported by multiple gardens, ranging from 12 gardens down to a single garden. Rankings were Invasive, Potentially Invasive, Watchlist, and Assessed as Invasive, based on the 996 garden reports. The numbers at the base of each column indicate the number of species within each garden category. For example, only a single species was reported by 12 gardens, with 4 gardens ranking the species as Invasive, 4 gardens as Potentially Invasive, 2 gardens as Watchlist, and 2 gardens as Assessed as Invasive.

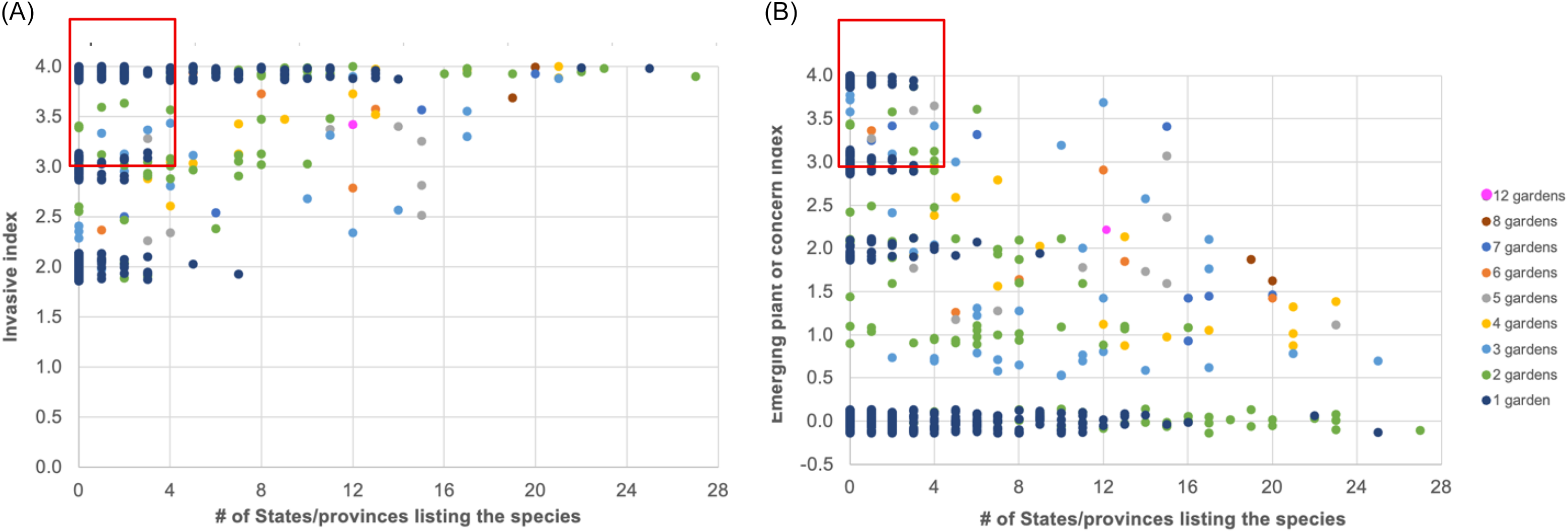

Of the 33 species reported by more than a single garden as Invasive, all were listed by at least six states or provinces as being invasive or noxious, with only three exceptions: common hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna Jacq.), I. helenium, and Siberian squill (Scilla siberica Andrews). Other species ranked by gardens as Invasive are already considered invasive or noxious outside the gardens, such as tree of heaven [Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle], autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb.), and round-leaved bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus Thunb.). In fact, the Invasive Index and the number of listing states was correlated (r = 0.44, P < 0.0001; Figure 4), even given the number of states and provinces listing species with the same index value (e.g., 4.0). This correlation could potentially have been even higher, except for the inconsistency and reactive nature of state listing (Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Beaury, Fusco, Munro, Brown-Lima, Coville, Kesler, Olmstead and Parker2022) and the reluctance of states to list or regulate certain species, especially if viewed as economically valuable in the horticultural or agricultural industry. The significant correlation may also indicate some gardens are making greater efforts to evaluate their collections in light of existing regulatory lists. The association between garden reports and external state and province listings for many individual species validates the ability of gardens to detect largely established invasive species and also justifies their effectiveness in identifying problematic species within the larger landscape.

Figure 4. The relationship between the (A) Invasive Index or (B) Emerging Plant of Concern Index for each reported plant species according to the number of states/provinces that publicly list the species (as invasive, noxious, etc.). Each point on the graph represents a single species, which is color-coded according to the number of public gardens that reported it as problematic. To prevent points from overlapping, their individual locations were slightly jittered. There was a significant positive correlation for the Invasive Index (r = 0.44, P < 0.0001) and a negative correlation for the Emerging Plant of Concern Index (r = −0.41, P < 0.0001) with the number of listing states. The red box indicates the species of most concern; i.e., those that are often reported by the gardens as problematic (especially those reported by multiple gardens), but that have not risen yet to level of public concern.

An alternative way to examine the PGSIP database is to consolidate all rankings across gardens into a single Invasive Index for each species. In this case, those species with a higher index tended to be reported by larger numbers of gardens (Table 1), although across all species, there was no correlation between the Invasive Index and the number of reporting gardens (r = −0.03, P = 0.508). Species with the highest Invasive Index values were the midwestern invasive species Amur honeysuckle [Lonicera maackii (Rupr.) Herder], common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica L.), and white mulberry (Morus alba L.), each identified as Invasive in five gardens and already recognized outside gardens as invasive.

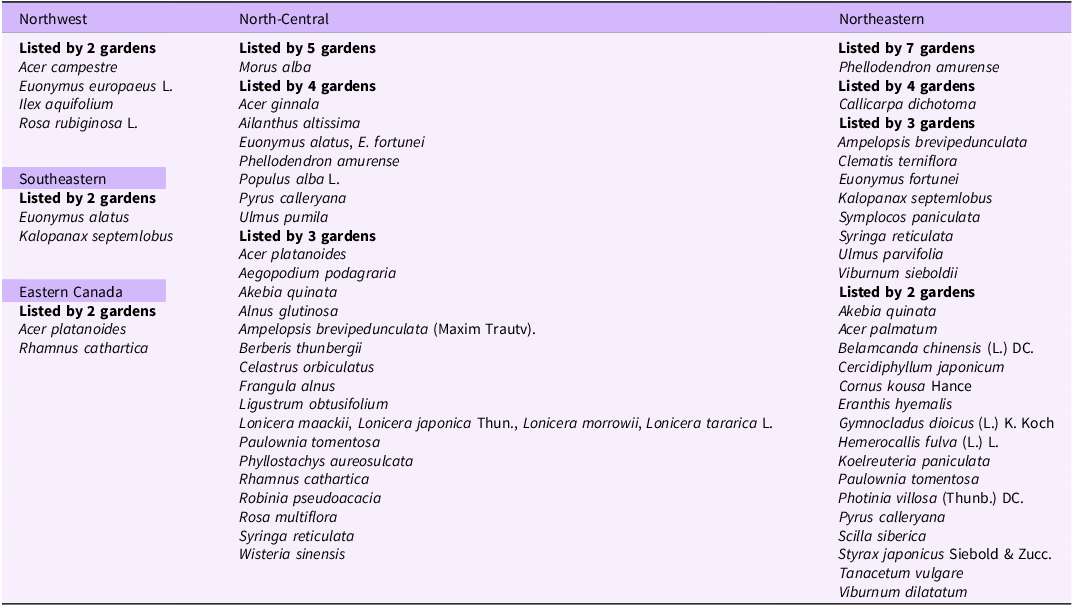

The extent of spread for individual species within North America is likely influenced by different climatic regimes (Table 2) in addition to time. Forty-four species (7%) were individually reported by gardens across three or more TDWG regions and are examples of expansive spread potential (Figure 5). Most species were identified within the northeastern or midwestern areas of North America (Supplementary Figure S1), where most PGSIP gardens are located, including three gardens that contributed one-third of all submitted records. Within the North-Central and Northeast regions, the top species were P. amurense (reported by seven gardens) and M. alba (five gardens). Many species reported within a region were also reported within a neighboring region (Supplementary Data). For example, Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana Decne.), chocolate vine [Akebia quinata (Houtt.) Decne.], and Japanese tree lilac [Syringa reticulata (Blume) H. Hara] were reported in adjoining North-Central and Northwestern regions; castor aralia [Kalopanax septemlobus (Thunb.) Koidz] was noted in the Southeastern and Northeastern regions; and Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.) was reported in Eastern Canada and the North-Central regions. In contrast, some species reported by multiple gardens were only found within a single region, exemplifying localized spread potential (Figure 5); these included winter aconite [Eranthis hyemalis (L.) Salisb.] (Northeastern), common holly (Ilex aquifolium L.) (Northwest), Siebold’s viburnum (Viburnum sieboldii Miq.) (Northeastern), and W. sinensis (North-Central). In the South-Central and Southwestern regions, no species were reported in more than a single garden, likely due to the few sentinel gardens in those areas.

Table 2. Top problematic species within TDWG (Taxonomic Databases Working Group, also referred to as the Biodiversity Information Standards) regions, reported by at least two gardens. a

a Species are presented in alphabetical order under the number of gardens within each region. Due to space, 75 species listed by two gardens are not shown for the North-Central region, and the Southwest and South-Central regions only had species listed by single gardens.

Figure 5. General types of spreading species based on reports from the Public Gardens as Sentinels against Invasive Plants (PGSIP), based on the number and location of gardens reporting the species as problematic according to the TDWG (Taxonomic Databases Working Group, also referred to as the Biodiversity Information Standards) regions designated by the International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Sciences (https://www.tdwg.org/standards/wgsrpd/). Example species for each generalized spreader type are provided.

Compared with the large proportion of species listed by multiple gardens as Invasive, Potentially Invasive, or Watchlist (Figure 3), more than half of species listed by only one to two gardens were ranked as Assessed as Invasive. In contrast to the other observation-based rankings, the Assessed as Invasive category pertains only to species that go through a garden’s own formal risk assessment process to protect the collection from “bad actors” either already in the collection or before their entry. Only some of the largest PGSIP gardens incorporate this approach, but they had a large effect on the overall results, with 44% of all species listed as Assessed as Invasive (35 species each listed by two gardens, and 227 species by one garden). At least one of these gardens has already assessed all U.S. federally noxious weeds, resulting in the large number of non-ornamental Prosopis species in the database.

Sentinel Function of Public Gardens

The value of the PGSIP garden network and database resides in its sentinel function, revealed when a species recorded by gardens is rarely, if at all, listed by states as invasive or noxious (Table 1). Of the 597 species reported by PGSIP gardens, 35.7% (n = 213) were not listed at all by any state or province; most of these species were only reported by a single garden (many as Watchlist; Supplementary Data). Of species reported by two or more gardens, 14.2% (27 of 190 species) were not listed by any state or province; only 12 species (6.3%) were listed by a single state/province—and not always in the same state in which reporting gardens were located (Table 1). For example, S. reticulata was reported by seven gardens in the Midwest (Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio, and New York), but only listed by the State of Maine. These species can be considered overlooked spreaders (Figure 5).

Another indicator of potential invasiveness of a garden species is the combination of reports across regions and the Emerging Plant of Concern Index. In fact, there was a significant correlation between the number of TDWG regions inhabited by reporting gardens and the Emerging Plant of Concern Index (r = 0.21, P < 0.0001), a relationship stronger than for the Invasive Index (r = −0.09, P = 0.031). For example, the top species with the highest Emerging Plants of Concern Index values were reported across three or more TDWG regions (Table 1); these included katsura tree (Cercidiphyllum japonicum Siebold & Zucc.), purple beautyberry [Callicarpa dichotoma (Lour.) K. Koch], and sweet autumn virginsbower (Clematis terniflora DC.). These species are considered new and upcoming spreaders (Figure 5).

The sentinel nature of the PGSIP database is further supported by the negative correlation between the Emerging Plant of Concern Index and the number of states and provinces that listed each species (r = −0.41, P < 0.0001; Figure 4). For example, the top seven species with the highest Emerging Plant of Concern Index appeared on fewer than four state and province lists (Table 1). Although it may appear that the Emerging Plant of Concern Index generally increased as the number of gardens reporting the same species decreased, this is partly a methodological result, because the index weights the Watchlist category, and the majority of species reported by a single garden were categorized as Watchlist. But it also reveals just how common it is for gardens across North America to observe a unique species escaping cultivation. The negative correlation between the index and the number of reporting states also indicates that political entities may not yet be noticing taxa the gardens are reporting as problematic, further emphasizing the sentinel value of garden data. Consequently, the gardens are effective in identifying plants that have not yet garnered popular notice, but can be problematic on a large scale, especially when reported by multiple gardens.

Despite the lack of recognition on the state level, many species reported by the gardens as problematic have not completely escaped detection. Within the scientific literature, 339 of the 597 reported garden species (56.8%) had been referred to as invasive in one or more peer-reviewed papers from 1959 to 2020. Of the 84 species reported by three or more gardens, the majority (n = 71, or 84.5%) had already been referred to in the literature as invasive. Exceptions of species without any reference in the literature included K. septemlobus and S. reticulata (detected in seven gardens), and C. dichotoma, S. siberica, and Chinese elm (Ulmus parvifolia Jacq.) (in five gardens). Plants reported by multiple gardens but not yet documented in the scientific literature are further examples of the value of public gardens as sentinels of plant invasion, highlighting the need for additional scientific research.

Characteristics of Problematic Species in Gardens

Many of the species listed by multiple gardens tended to be woody (Figure 6), consisting of trees, shrubs, and woody vines, but many species listed by fewer gardens (especially as Watchlist) were herbaceous. In fact, the majority of reported species overall were herbs (49%), with trees (15%) and shrubs (15%) being the next most common growth habits, followed by graminoids (11%) and vines (6%; Figure 6A); most problematic vines were woody (22 of 37 vines, or 59.5%). Although there has historically been an emphasis on invasive woody species in the literature (e.g., Reichard and Hamilton Reference Reichard and Hamilton1997; Reichard and White Reference Reichard and White2001), the data here suggest that herbaceous species, including graminoids, may be important in future invasions in North America.

Figure 6. The distribution of growth habit (trees, shrubs, vines, herbs, and graminoids) in the 597 unique species reported by Public Gardens as Sentinels against Invasive Plants (PGSIP) gardens as (A) across all gardens and (B) according to the number of gardens reporting the same species. The number at the base of each bar in (B) indicates the number of species reported by that number of gardens.

Problematic species reported by gardens belonged to 112 taxonomic families, most frequently Rosaceae, Fabaceae, Poaceae, and Asteraceae (Supplementary Table 1). There were 361 genera also represented (Supplementary Table 2); the most commonly reported genera were Acer, Lonicera, Allium, Clematis, Viburnum, Berberis, Prunus, and Sedum. These are of frequent and popular ornamental use. The genera Prosopis, Solanum, Centaurea, and Pennisetum were also listed, but only because species within these genera were typically Assessed as Invasive.

Although invasive species are usually defined as being non-native (Clinton Reference Clinton1999; Obama Reference Obama2016), several gardens did include species considered native to North America. Of the 597 individual species reported by gardens, 12% (71 species) were native within some area of North America, including 41 species native to both the United States and Canada, two species native only to Canada, and 28 species native only to the United States. Inclusion of native species as problematic within gardens may seem counterintuitive, but gardens were only asked to report species on their property that “are not part of the native flora of the garden’s immediate region” [emphasis added]. In fact, sentinel gardens located across North America may exist within or outside some species’ natural ranges. For example, black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) was noted as of concern by gardens in Illinois and Massachusetts (largely outside its natural range) and in Ontario (where it is considered introduced). In another example, swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata L. ‘Cinderella’) was listed as Potentially Invasive by one garden in the Northwest, which is outside the native range of this species in North America. However, this same species is considered a very effective native host plant for the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) in the U.S. Midwest, where planting is encouraged for monarch conservation. Thus, a species may be viewed as “problematic” in gardens regardless of its native status within broader North America.

There was also a distinct link between the top problematic plants reported by gardens and use in the nursery industry. Of the 84 species each listed by three or more gardens, all but one species (Japanese stiltgrass [Microstegium vimineum (Trin.) A. Camus]) had been sold in seed and nursery catalogs in the past (Fertakos et al. Reference Fertakos, Beaury, Ford, Kinlock, Adams and Bradley2023); this species was purportedly introduced by accident from Asia (Fairbrothers and Gray Reference Fairbrothers and Gray1972). The number of times a species was advertised in a catalog ranged from only a handful of times (e.g., four for yellow groove bamboo [Phyllostachys aureosulcata McClure]) to several thousand (e.g., 5,780 times for guelder-rose [Viburnum opulus L.]). Of the 180 species reported by only one garden as escaping cultivation, 39 were never mentioned in these seed catalogs, 28 were mentioned 1 to 10 times, 55 appeared more than 500 times, and 37 were listed more than 1,000 times (Fertakos et al. Reference Fertakos, Beaury, Ford, Kinlock, Adams and Bradley2023; Supplementary Data). Some plants reported by single gardens also had the highest possible value for the Emerging Plant of Concern index, such as chameleon plant (Houttuynia cordata Thunb.) and Taiwanese snowball (Styrax formosanus Matsum.). The species reported in common by the highest number of gardens are almost all woody, and many ornamental plants are already recognized as invasive in state and province lists. For example, 82% to 86% (Culley and Feldman Reference Culley and Feldman2023; Reichard Reference Reichard1994) of woody invasive species in the U.S. Midwest are associated with past or current horticultural use. Thus, the PGSIP database can be particularly effective, because it can capture previously unrecorded spreading behavior of ornamental plants spreading from cultivation, well before they might be released and sold more widely.

Because our database relies on the expertise of garden staff who carefully monitor and document their collections, we are able to recognize that some species may be escaping within the garden in certain circumstances. For example, Japanese maple (Acer palmatum Thunb.) was listed as Invasive in one garden and on the Watchlist in four additional gardens. However, as anecdotally reported by one garden, the species is only problematic when cultivated as a collection of many different cultivars. In yet another example, P. amurense is dioecious, but seeds and seedlings can still persist within a collection even if female trees are removed. Because garden records detailed the sex and reproductive output of trees over time, we now know that reportedly male trees are able to occasionally produce berries along one or more branches. This understudied reproductive mechanism involving sexual lability may explain the dense occurrence of P. amurense seedlings and saplings in natural areas of some gardens surrounding their formal collections, despite removal of female trees.

Current Status of the PGSIP Database and Future Directions

The power of the PGSIP database is in identifying up-and-coming, potentially invasive species. It now allows us to identify species of rising concern (Figure 5), including species that demonstrate potential for expansive or localized spread, and those that may need to be considered further for listing by states and provinces. Approximately one-third of the species reported by PGSIP gardens were not listed by any state or province, indicating there are many potentially problematic species that need to be monitored and are not advised for development for the horticultural trade. Watchlist species are critical in the sentinel aspect of gardens, because they may not be widely used yet in the horticulture industry or widely cultivated within botanic gardens and arboreta. In fact, more than half of the species with the highest Emerging Plant of Concern Index are on few, if any, state- or province-based lists, even though they were reported in gardens across several regions. Detecting up-and-coming species in this way illustrates the usefulness of the garden database, because otherwise the early potential for spread might go undetected, except within the individual gardens where they are cultivated. Sharing this information more broadly allows PGSIP garden staff to detect larger patterns and keep a watchful eye on these species going forward. These data can also proactively guide the horticultural development of any species well before release for commercial trade—thus preventing subsequent detrimental impacts within natural areas.

The strength of the sentinel network is not only in the ability of gardens to directly share reports of problematic taxa with one another, but also to better understand past and ongoing spread. Because gardens can track provenance information and management regarding past escape or current spread, we can use that information to track past behavior of a species over time. In addition, the PGSIP database is a “living document” in which gardens are able to update their individual rankings, especially if a species becomes more problematic through time. Thus, a particular species can also be tracked going forward within a given location. This temporal aspect can be another of the multiple dimensions affecting spread, such as geographic range size and local abundance, which are already being used to understand invasion processes (Fristoe et al. Reference Fristoe, Chytry, Dawson, Essl, Heleno, Holger Kreft, Noëlie Maurel, Pergl, Pyšek, Seebens, Weigelt, Vargas, Yang, Attorre and Bergmeier2021). Furthermore, PGSIP data can serve to validate existing geographic models of estimated spread due to changing climatic conditions.

The current PGSIP database is not without limitations. First, gardens are only asked to submit reports of species that are problematic within their properties (i.e., presence data), and not reports of species that do not show any signs of spread (absence data). Consequently, while we can suggest which species might be a problem in a region of North America, we cannot conclusively say that that the species is not a problem in a different region. In other words, it would be helpful to know what proportion of gardens have species not spreading from cultivation. The database also requires the taxonomic identification of a species, which might not always be known—and therefore potentially valuable reports might be excluded from the database. This is especially true for offspring of plants within a collection that do not closely resemble either parent and can also revert to a different native phenotype (such as spurs appearing on P. calleryana offspring). For example, several gardens with natural areas have recently noted an aggressive crabapple that often keys out to Siebold’s crabapple (Malus toringo; syn.: Malus sieboldii Rehder) but appears to be a possible hybrid of multiple Malus species. This plant is likely underreported due to taxonomic confusion about its identity, although the Dawes Arboretum is now conducting a genetic study to fill this gap (D Brabdenburg, personal communication). This plant had not been reported in the PGSIP database (nor have any Malus species), because the portal originally did not allow for submission of an unknown species. Consequently, many gardens were unable to share their reports regarding this aggressive plant, and others do not know to look for it within their properties. Given the popularity of crabapple species within the gardening public and for landscaping [Malus sylvestris (L.) Mill., Malus baccata (L.) Borkh., etc.; Beaury et al. Reference Beaury, Patrick and Bradley2021b], it is urgent to understand its relatively sudden invasive behavior.

The species appearing on the garden list of problematic plants also reflect the current number and geographic locations of sentinel gardens in North America, especially in the Midwest, where the PGSIP network originated (Figure 2). Based on the BGCI global botanical garden database, most problematic species identified by PGSIP gardens are still cultivated in gardens continent-wide. For example, A. palmatum is present in the living collections of 235 North American gardens and golden rain tree (Koelreuteria paniculata Laxm.) occurs in 104 gardens. This suggests that additional gardens could effectively contribute to the effort to track behavior of these species across multiple growing zones. As more gardens join the PGSIP program, we anticipate that the sentinel network will expand into new areas such as western Canada and Mexico and strengthen within existing locations. This will bolster the effectiveness and accuracy of the communication platform, enhancing detection of species spreading from cultivation, and it will also inform our understanding of regionality to better track and predict projected range shifts associated with climate change (Allen and Bradley Reference Allen and Bradley2016; Beaury et al. Reference Beaury, Allen, Evans, Fertakos, Pfadenhauer and Bradley2023; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Wilcove and Oppenheimer2010, Reference Bradley, Beaury, Gallardo, Jarnevich, Morelli, Sofaer, Sorte and Vilà2024; Roy et al. Reference Roy, Peyton, Aldridge, Bantock, Blackburn, Britton, Clark, Cook, Dehnen-Schmutz, Dines, Dobson, Edwards, Harrower, Harvey and Minchin2014).

While access to the PGSIP database is limited to participating gardens, information is now being shared more widely, such as through PGSIP Plant Alerts. The first alert on P. amurense was released in September 2023 (https://pgsip.mortonarb.org/Bol/Content/Projects/pgsip/Resources/Plant_Alert_Amur_Corktree.pdf), and new alerts will be released as data become available. This is in addition to the public-facing PGSIP dashboard (https://pgsip.mortonarb.org//Bol/pgsip/Data), where top plants of concern are displayed within a user-defined state or region. Home gardeners, landscape architects, and nursery suppliers and distributors can use this dashboard to check for plants that gardens may have flagged as problematic. Upon request, the PGSIP Working Group also provides information to state-based agencies on species assessed for regulation, such as the number of gardens reporting the species and their rankings.

As sentinels of plant invasion, public gardens and arboreta now offer a unique opportunity to help predict which introduced plant species may have the propensity to escape cultivation and become invasive in the near future. Based on our standardized guidelines and the participation of 53 gardens, the PGSIP database reveals that certain ornamental species in North America now warrant monitoring by land managers in the field, and possibly their pre-emptive removal, given their propensity to spread. The ability to reduce management costs by detecting early plant invasions through this garden network will improve with the addition of more gardens across North America, contributing their own data in additional regions and growing zones. We now invite invasive species councils, state agencies, and other entities tasked with invasive plant assessment and/or regulation to consider the problematic species identified here by the sentinel gardens within their regions.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2025.10035

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ed Hedborn from the Morton Arboretum for reviewing the nomenclature of the plant lists, Sai Ravichandran for implementing software coding changes to the PGSIP platform, Evelyn Beaury for helpful conversations, staff from the Botanical Garden Conservation International for sharing their data, and anonymous reviewers for their input on this paper.

Funding statement

This work is supported by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Crop Protection and Pest Management Program through the North Central IPM Center (2014-700006-22486 and 2022-70006-38001).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.