Introduction

Antipathy between supporters of different political factions, or affective polarization, is a concern that sits high on the academic and political agenda. The primary concern is not so much with affective polarization itself but rather its potentially destructive consequences, such as the erosion of social cohesion and democratic norms, political gridlock and possibly even violence among citizens (e.g., Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021; McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018). This array of potential consequences can be sorted along two main axes: one horizontal (how citizens view and approach others across political and non‐political settings) and one vertical axis (how citizens view and relate to the political system). In this paper, we focus on the horizontal axis and attempt to unravel the connection – on the level of citizens’ attitudes – between affective polarization and inter‐citizen consequences of a more severe nature. While virtually all previous studies have focused on the United States, we assess the extent and correlates of such more severe consequences in two European countries: Norway and the United Kingdom. This allows us to test a general framework across two societies that score (respectively) low and high on affective polarization (Wagner, Reference Wagner2021).

Our study thus takes a reverse approach to most previous political behaviour studies on this issue by treating affective polarization as an independent rather than dependent variable. We zoom in on three key alleged inter‐citizen consequences at the individual and attitudinal level: (1) intentions to avoid members of the opposing side in everyday life (avoidance), (2) willingness to curtail the other side's political rights (intolerance) and – at its most extreme – (3) supporting violence against them (support for violence). These three follow a gradation in terms of how detrimental they can be to the fabric of society and functioning of democracies. Therefore, the prohibitive strength of the normative barriers against them also ramps up in intensity, ranging from low for avoidance, intermediate for intolerance and extreme in the case of violence (e.g., Decety & Cowell, Reference Decety and Cowell2018; Gavrilets & Richerson, Reference Gavrilets and Richerson2017). Breaking these barriers, therefore, entails a successive escalation in the normative sense. We field measures of these three forms of norm‐breaking escalation in two large representative samples, assess their relation to the ‘go‐to’ measure of affective polarization (the so‐called feeling thermometer) and formulate and test theoretical expectations about the drivers of avoidance, intolerance and support for violence.

Two key findings bear highlighting. First, we find that avoidance, intolerance and (to a very limited degree) support for violence exist in European societies. However, outgroup dislike as measured through feeling thermometers does a progressively worse job at predicting these inter‐citizen consequences as they increase in severity. Disliking members of the other side correlates somewhat with avoiding them, but much less so with intolerance and not at all with support for violence. This holds in both the United Kingdom and Norway, suggesting that there is no monocausal and unambiguous relationship between affective polarization as it is traditionally measured and more severe negative inter‐citizen consequences. This has important methodological as well as theoretical implications. There are limits to inferring norm breaking, escalating polarization from mere feeling thermometers alone, suggesting it pays off for scholars and practitioners to measure these phenomena directly.

Second, our findings move us closer to understanding why some citizens do tend towards avoiding, not tolerating, or even condoning violence against political opponents. This is our primary theoretical contribution. We do so by positing and testing expectations derived from the literature on intergroup emotions and political radicalization, which have both grappled with similar questions. In line with the literature on intergroup emotions, we argue and show that citizens’ willingness to escalate hinges on the specific emotional response that the political outgroup elicits (Mackie et al., Reference Mackie, Smith and Ray2008; Stephan, & Stephan, Reference Stephan, Stephan, Kim and McKay‐Semmler2017). While levels of fear and anger (traditionally associated with, respectively, avoiding or approaching) play a role, disgust turns out to be the strongest emotional predictor for moving beyond merely disliking outgroup partisans in our study. On its part, the literature on political radicalization posits that certain predispositions and traits can facilitate the process of violating social norms – even those that inhibit intolerance and violence (Borum, Reference Borum2011; McCauley & Moskalenko, Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2008). Supporting this, we find that a Manichean mindset (black‐and‐white thinking), generalized relative deprivation (an amorphous sense of belonging to a group that is treated unjustly) and dark personality traits (here psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism) each play an important role in predicting negative inter‐citizen consequences. Their predictive power is often sizeable: while very few across the board condone violence, those exhibiting higher dark personality scores are many times more likely to do so.

The substantive lesson that can be drawn from our study is that disliking a political outgroup does not equal avoiding, not tolerating them, or wishing them harm. This is in line with the intergroup emotions and radicalization literature but has important implications for our interpretation of affective polarization and its consequences as well as for the way we study polarization empirically. While our findings fit within a general framework of escalation, it is one with increasingly inhibitive ‘costs’. Under present conditions, those that are likely to escalate ‘furthest’ in the sense of breaking even the strongest normative barriers, such as the taboo against violence, are a minority exhibiting extreme personality traits. When trying to understand just how far people may escalate beyond affective polarization in the narrow sense of antipathy towards outgroup partisans, other factors besides dislike must enter into the equation. The feeling thermometer has great value in measuring affective polarization comparatively but caution is needed to extrapolate from it to other forms of negative inter‐citizen relations. Importantly, our cross‐sectional study does not test the causal nature of the relationship between these concepts. Rather, our aim is to establish whether phenomena that have been argued to follow in the wake of affective polarization indeed strongly correlate with it or whether additional explanations are required. Our study provides evidence for the latter.

In this paper, we will proceed in the following manner. We begin with an overview of the literature on affective polarization and its consequences, the three negative inter‐citizen attitudes under scrutiny and the lessons we can draw from studies of intergroup emotions and political radicalization. This is followed by a brief overview of our data, as well as sections devoted to a description and cross‐validation of the measures, the correlation between each of three main concepts of interest and the feeling thermometer and a set of regression models aiming to identify their alternative predictors. In the concluding discussion, we sketch a tentative general model of escalating polarization deduced from the findings, outline the normative implications these findings have and finally elaborate on the methodological lessons to be learned.

Affective polarization and its consequences

There has been a long, ongoing academic debate in the field of political behaviour about whether citizens are becoming more politically polarized, especially in the United States (e.g., Abramowitz & Saunders, Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Fiorina & Abrams, Reference Fiorina and Abrams2008). Iyengar and colleagues (Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012) shifted the focus from ideological divergence and alignment to the affective distance between citizens, for which they coined the term affective polarization. In so doing, they revitalized a social‐psychological approach to polarization as an instance of intergroup conflict and laid the foundations for what has become a new research agenda. While this kind of polarization entails crucial meso‐ and macro‐level dynamics, the political behaviour literature usually defines and operationalizes affective polarization on the individual level. Initially defined in the United States context as ‘the tendency of people identifying as Republicans or Democrats to view opposing partisans negatively and co‐partisans positively’ (Iyengar & Westwood, Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015, p. 691), partisan antipathy towards adherents of other political factions is thought to be the key component leading to other, detrimental consequences (Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021, p. 29). This is also what the current study focuses on citizens’ negative evaluations of political outgroups. We leave it open as an empirical question to what extent these are in turn associated with ingroup attachment.

Another point of debate in the political behaviour literature concerns the scope of affective polarization. Some scholars have included avoidance of political outgroups in their operationalization of affective polarization itself (e.g., Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2020), whereas others have argued against equating the two (Druckman & Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019). In a maximalist approach, even intolerance and violence might be considered part of ‘outgroup derogation’ and hence affective polarization itself. We instead take a minimalist approach and restrict the term affective polarization to political outgroup antipathy; that is, ‘mere’ dislike. For the sake of analytical clarity, this leaves everything else to the realm of possible correlates, of which the relation to disliking out partisans is open for theoretical and empirical scrutiny.

Studying possible consequences in their own right is important. Studies in the United States have shown worrying evidence for intolerance and discrimination towards (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019) and dehumanization of, political opponents (Martherus et al., Reference Martherus, Martinez, Piff and Theodoridis2021) support for political violence (Kalmoe & Mason, Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022) and the eroding of democratic norms (Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021). In many instances, these have been shown to correlate with outgroup dislike. In comparison, our understanding of affective polarization in Europe and other regions outside the United States has so far been mostly restricted to ‘feeling thermometers’ – a survey measure originating in the US election studies tradition that asks respondents to what extent they feel ‘cold’ or ‘warm’ towards, or ‘dislike’ or ‘like’, certain political groups (e.g., Reiljan, Reference Reiljan2020; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021).

Given their strength in operationalizing a general form of antipathy between political camps, it is understandable that feeling thermometers – or adaptations thereof – have become the field's instrument of choice. These studies provide important information about the large spatial and temporal variation in affective polarization but offer less insight in terms of implications. What perhaps evolved out of convenience, not least due to its longstanding inclusion in longitudinal and comparative survey projects, may hamper the field's further progression to understand which consequences might follow from such generalized antipathy.

In line with the political behaviour literature, we study alleged consequences on the individual level. While many concerns have been expressed regarding outcomes on a group or system level (such as societal cohesion or democratic health), these arguably involve individual‐level mechanisms as well – that is, citizens changing their views or behaviour. Within the array of potential negative individual‐level consequences mentioned in the literature, we can make a heuristic distinction between those that pertain to how citizens view and approach each other (‘horizontally’) and those that pertain to how citizens view and approach the political system (‘vertically’), corresponding to two separate axes.

Examples of alleged ‘vertical’, system‐oriented consequences include (but are not limited to) an unwillingness to accept political compromise and support for elite transgression (e.g., Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022; Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021). Examples of ‘horizontal’, negative interpersonal consequences include the previously mentioned desire to avoid supporters of the opposing side in everyday life or to wish them harm. Some evaluations, norms and behaviours also cut across these two main axes – for instance, when intolerance in everyday life extends to supporting laws enshrining such practices, or when support for violence against fellow citizens spills over to attacks against representatives of the state (or vice versa).

The ‘horizontal’ consequences are the focus of this study. In particular, this study explores three key domains of inter‐citizen consequences that we expect to be important in the European context too: avoidance, intolerance and support for violence. As we will discuss later, the prohibitive strength of the norms against these ramps up in intensity (e.g., Decety & Cowell, Reference Decety and Cowell2018; Gavrilets & Richerson, Reference Gavrilets and Richerson2017).

Two preliminary caveats are in order. First, we study these issues at an attitudinal level, rather than through actual behaviour. This is in line with most of the current literature in the sub‐field of affective polarization, but we should be cautious about drawing conclusions from survey responses to claims about behaviour, which requires further study in its own right. Second, while these are generally understood as potential consequences and treated in this manner here, we do not exclude that they (to varying degrees) in turn also foster affective polarization – that is, their relation is possibly endogenous. This is particularly plausible for avoidance, given that the absence of meaningful contact can further entrench outgroup bias (Allport, Reference Allport1954; Wojcieszak & Warner, Reference Wojcieszak and Warner2020). It is beyond our cross‐sectional study to dissect the causal effect in each direction. However, seeing how these phenomena have repeatedly been proposed in the literature as consequences, it is a crucial step to establish to what extent they are indeed linked to affective polarization.

We introduce each concept in turn below. After that, we turn to the question of what alternative explanations might explain these phenomena, beyond (or even instead of) affective polarization.

Avoidance

Avoidance refers to the motivation and intention to stay away from political outgroups. Avoidance is related to social distance, or ‘the grade and degrees of understanding and intimacy which characterizes personal and social relations generally’ (Park, Reference Park1924, p. 339). As noted earlier, this phenomenon has sometimes been utilized to gauge affective polarization itself (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; for a critique, see Druckman & Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019), but here we make an analytical distinction between the affective component of antipathy (dislike, anger, etc.) and such intentions. Social distance is an intergroup phenomenon and has previously been applied to, among others, ethnic, racial, class or national groups. Socially distant groups do not mix or do not want to mix, regularly or voluntarily. Affective polarization increases the costs of interacting with political outgroup members, and it is, therefore, plausible that it results in increasing avoidance. Indeed, Americans of the opposing political camps have been reported to avoid each other as (among others) dating partners and family members (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012) or friends (Bakshy et al., Reference Bakshy, Messing and Adamic2015). It might even motivate them to form segregated neighbourhoods (Gimpel & Hui, Reference Gimpel and Hui2015). Prolonged social distance between political camps results in an entrenchment of political differences in the social fabric itself, as the opposing camps will segregate into different social circles, neighbourhoods, sport clubs, media environments, etc., all to avoid each other.

Intolerance

At some point, outgroup antipathy might undermine political tolerance, or ‘the extent to which people extend civil liberties and rights to groups or individuals with whom they disagree’ (Crawford & Pilanski, Reference Crawford and Pilanski2014, p. 841). In Western democracies, support for such rights and liberties is almost universal in the abstract, but less so when citizens are presented with concrete cases. Political intolerance might be principled and thus guided by some objective exclusion criterion. Alternatively, it can be strategic, when intolerance is applied only to ideological opponents without consistently applying a principle (Lindner & Nosek, Reference Lindner and Nosek2009). Levitsky and Ziblatt (Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018) demonstrate through the use of historical accounts that it is counterintuitive to sustain political tolerance for opponents. On the more extreme end, citizens might question their opponents’ right to vote (having relinquished this by their abject political choices), but more often this involves questioning or obstructing rights such as those of expression or demonstration, often in concrete everyday situations. Some legitimate claims to limit these rights do exist (and most societies do set legal boundaries), for instance, in the case of extremist movements. Our argument here pertains to intolerance towards supporters of movements that arguably remain within democratic boundaries. We expect tolerance is harder to sustain to the extent that political outgroups are vehemently disliked.

Support for political violence

Support for violence sits among the most dramatic and potentially detrimental consequences of outgroup antipathy. Political violence can be described as particularly ‘anathema’ to the ‘spirit and substance’ of democracy (e.g., Keane, Reference Keane2004, p. 1). Physical violence between partisans is not a mass phenomenon in contemporary European democracies such as the United Kingdom and Norway, and the number of deadly attacks committed by, for instance, right‐wing extremists has remained stable at a relatively low level over the last two decades (e.g., Ravndal et al., Reference Ravndal, Tandberg, Jupskås and Thorstensen2022). Nevertheless, just one instance of political violence can have tremendous repercussions (e.g., 22, July 2011, terrorist attacks in Norway; Berntzen, Reference Berntzen2020; Solheim & Jupskås, Reference Solheim and Jupskås2021).

As Kalmoe and Mason (Reference Kalmoe and Mason2019) note for the American context, the study of political violence at the mass level used to occupy itself with historical examples but is now increasingly employed to study contemporaneous society. They show that a non‐negligible share of Americans (up to half) claims to have positive associations with forms of harm against political opponents, and up to one‐tenth of the population might even endorse it. On the other hand, Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022) argue that public support for political violence tends to get overestimated (among others because survey items are often abstract). Regardless, support for political violence obviously constitutes a very extreme and almost universally rejected form of norm‐breaking escalation, but its ongoing occurrence shows it is not completely beyond the pale in established democracies. Hate speech, harassment and bullying can also be said to constitute a form of non‐physical violence, something which has become more visible in online spaces. Arguably, extreme levels of affective polarization make it more palatable to condone or even use (non‐)physical violence against those politically opposed to us. If so, high levels of affective polarization would constitute a grave danger. For our purposes, we see support for political violence as encompassing all stages from online harassment to physical violence. We have therefore incorporated both general and specific measures regarding both the threat or use of physical violence against outgroup partisans (elaborated on in the Data and Measures section below).

Explaining avoidance, intolerance and support for political violence

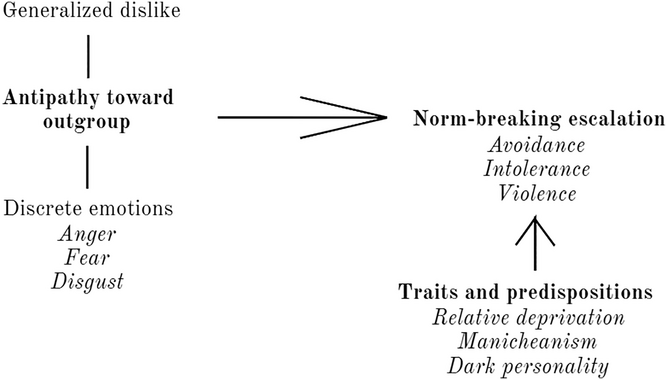

The relationship between the aforementioned phenomena and affective polarization is plausible. Yet, at the same time, not all affectively polarized citizens in our societies are avoiding each other, intolerant or supportive of violence. Below, we argue why these alleged outcomes – to varying extents prohibited by social or legal norms – require more than mere dislike to emerge. We turn to the literature on intergroup emotions and political radicalization to theorize which other factors might shape norm‐breaking escalation directed towards other citizens. Figure 1 visualizes the relation between antipathy towards the outgroup; traits and predispositions that facilitate norm breaking; and the three instances of norm‐breaking escalation under study.

Figure 1. Elements of escalating polarization: from affect to norm breaking.

Note: Terms in bold font represent broader constructs, whilst italicized items are components of these.

As the visualization suggests, we expect antipathy (and its more discrete components) to play a role in norm‐breaking escalation, alongside and in conjunction with key traits and predispositions that are otherwise unrelated to outgroup perceptions as such. The figure is intended as a heuristic and does not show presumed relationships between sub‐components. Instead, we elaborate on the individual expectations in the subsequent sections. Not visualized in the figure (because we do not further theorize it) is the possibility that the outcomes might in turn foster affective polarization (which, as noted, is particularly plausible for avoidance). In addition, we do not make any prior assumptions about the internal relationship between the three norm‐breaking dimensions other than noting that the inhibitive barriers that society imposes against them are lowest for avoidance, which primarily relates to aspects of courteousness, and social congeniality, and highest for violence, codified in the penal system.

The role of emotions

Implied in the adjective ‘affective’ to the noun ‘polarization’ is that citizens experience negative emotional responses towards outgroup members. What these emotions entail usually remains implicit, and operationalizations are usually restricted to a generalized ‘dislike’ or ‘cold feelings’. Insights drawn from the literature on intergroup relations let us unpack the full range of antipathy beyond the valence‐based approach of either ‘liking’ or ‘disliking’ political groups, indicating we ought to turn our attention to differentiated emotional responses (e.g., Mackie & Smith, Reference Mackie and Smith2016; Maitner et al., Reference Maitner, Smith, MacKie, Sibley and Barlow2016) to understand the escalation from mere intergroup comparison to intergroup hostility (Brewer, Reference Brewer, Ashmore, Jussim and Wilder2001, p. 32). Drawing insight from both intergroup and appraisal theories of emotion, we can formulate clear expectations of when ‘dislike’ may well escalate to avoidance, intolerance and support for violence.

Negative emotions arise in response to both intergroup anxiety and perceptions of ‘realistic’ and ‘symbolic’ threats posed by an outgroup (see, Riek et al., Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006; Stephan et al., Reference Stephan, Renfro, Davis, Wagner, Tropp, Finchilescu and Tredoux2008; Stephan, & Stephan, Reference Stephan, Stephan, Kim and McKay‐Semmler2017). These emotions invite different responses, and the resulting ‘action tendency’ – either approach or avoidance – depends heavily on the particular type of negative affect experienced (Mackie et al., Reference Mackie, Smith and Ray2008). Within the parameters of affective polarization, which emotive responses to political outgroups might lead to avoidance downstream? Fear pushes people away from ‘offensive’ action and encourages risk aversion (Lerner & Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2000). It is often groups with limited power that experience fear in response to physical – or realistic – threats and, consequently, seek to avoid hostile out‐group members (Kamans et al., Reference Kamans, Otten and Gordijn2011). Similar to fear, disgust promotes avoidance (Shook et al., Reference Shook, Thomas and Ford2019) by bolstering the desire to move away from an outgroup (Mackie et al., Reference Mackie, Devos and Smith2000). Thus, we expect both fear and disgust (rather than anger) felt in response to outgroup citizens to predict avoidance.

Expectation 1a: Citizens who experience higher levels of fear and disgust are more likely to practice avoidance.

At the same time, disgust can also bolster protectionist responses. For example, disgust experienced in response to an outgroup threatening the values of the ingroup results in the drive to protect those values and interests (Matthews & Levin, Reference Matthews and Levin2012). Similarly, disgust sensitivity alone has been found to increase support for protectionist policies across a wide variety of domains (Kam & Estes, Reference Kam and Estes2016). Given that our conception of political intolerance involves restricting the rights and liberties of political opponents, feelings of disgust towards those very opponents likely spur support for limiting their democratic rights, as a means of protection.

Expectation 1b: Citizens who experience higher levels of disgust are more politically intolerant.

Anger is recognized as a mobilizing emotion, both in terms of positive participation, and potentially more hostile confrontational outcomes. Whilst anger in response to campaigning can boost political participation (Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011), in the context of intergroup competition it could increase support for political violence. Angry individuals are more likely to adopt approach tendencies, or offensive, rather than avoidant orientations. Anger also promotes optimistic risk evaluations, resulting in greater risk‐taking (Lerner & Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2000), thus it is perhaps unsurprising anger increases the desire to argue, confront or attack the opposing group(s) (Crisp et al., Reference Crisp, Heuston, Farr and Turner2007). Taken together, we expect that

Expectation 1c: Citizens who experience higher levels of anger are more likely to condone violence.

The role of traits and predispositions

A second set of expectations can be derived from the literature on political radicalization. This field has grappled with many of the same key issues as the literature of affective polarization (see Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019, p. 143). This becomes immediately apparent from one of the most used definitions of political radicalization as an ‘increased preparation for and commitment to intergroup conflict’ (McCauley & Moskalenko, Reference McCauley and Moskalenko2008, p. 416). While the field is not united in agreement over a particular radicalization model, some components are nevertheless common across different models. In particular, most view radicalization as a process, and most models present this process in terms of a chronology with steps, stages and phases (e.g., Borum, Reference Borum2011). While our study does not aim to describe the longitudinal dynamics of polarization, this insight does encourage us to conceptually distinguish dislike (and its accompanying discrete negative emotions) from their possible consequences. In addition, the literature on radicalization indicates that some people are far more likely to ‘advance’ to more extreme stages than others. This seems to be strongly contingent on individual predispositions and personality traits. For instance, the psychological profile of those that commit violence deviates from the general population, especially for the so‐called lone‐actor terrorists (Corner & Gill, Reference Corner and Gill2015).

What does this imply for understanding escalating, norm‐breaking polarization? Under most circumstances, except those where we already have a complete breakdown of the social and political mores of society (i.e., anomie) or a reversal of social norms (such as when society is in a state of war), the increasing prohibitive strength of the norms against avoidance, intolerance and support for violence ought to preclude most people from developing or expressing views in violation of them. Certain individuals’ predispositions might push them, however, to overcome these normative hurdles. Concretely, we expect relative deprivation, Manicheanism, and ‘dark’ personality traits to ease citizens’ progress into the most severe kinds of norm‐breaking escalation.

First, relative deprivation has been noted as an important contributing factor to action‐oriented behaviours and attitudes towards others in an extensive range of studies. Initially identified by the sociologist Samuel Stouffer in his survey studies of soldiers during WWII (1949), relative deprivation concerns an individual's perception of deprivation as opposed to being physically deprived in the traditional sense. A relevant distinction is found between the perception of being personally deprived in comparison to others versus perceiving that the group one identifies with is deprived (Runciman, Reference Runciman1966). The latter, described as group relative deprivation, contains a built‐in, generalized sense of injustice on behalf of the ingroup and the part of the opposing side, malevolence. It is particularly this kind of relative deprivation that has been found to increase peoples’ susceptibility to prejudice, and crucially, motivate collective action and support for violent measures against outgroups (e.g., Kunst & Obaidi, Reference Kunst and Obaidi2020; Pettigrew et al., Reference Pettigrew, Christ, Wagner, Meertens, Van Dick and Zick2008). Based on this, we expect that those who strongly identified as belonging to an unjustly deprived group are, in turn, more willing to deprive outgroup partisans of their rights and condone the use of violence against them.

Expectation 2: Citizens scoring higher on relative deprivation are more likely to condone intolerance and political violence.

Additionally, we expect more escalation among those who experience politics in strongly moralized black‐and‐white, or Manichean, terms. More specifically, we expect citizens with a Manichean outlook on politics to more readily condone intolerance and support violence. As noted, there exists a social norm that disagreements, however deep, have a rightful place in a democracy, precluding intolerance and violence. At the same time, some views are deemed morally prohibited. The more politics is seen in absolute moral terms, the stronger the moral imperative to prevent political opponents with abject views from scoring political victories. The term ‘Manicheanism’ has been employed most recently in the context of populism (Hawkins et al., 2019), which revolves around a moral distinction between ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. However, a strongly moralizing approach to politics is not restricted to populists. For instance, it also develops among populists’ opponents as they perceive populist parties to cross moral boundaries (Blinder et al., Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013; Meléndez & Kaltwasser, Reference Meléndez and Kaltwasser2021). We expect that those who see politics in moral imperative terms, whatever their political allegiance, are more likely to move to intolerance and support for political violence.

Expectation 3: Citizens scoring higher on Manicheanism are more likely to condone intolerance and political violence.

Finally, we expect that the most extreme form of norm‐breaking escalation is more likely among those with a ‘dark’ personality. Personality traits have been found to be heritable and relatively stable once a person enters adulthood (Vukasović & Bratko, Reference Vukasović and Bratko2015). Recent work suggests that people exhibiting high levels of Machiavellianism, psychopathy and narcissism (described as the ‘dark’ triad) are more prone to support and engage in malevolent acts against others, including violence (Pailing et al., Reference Pailing, Boon and Egan2014). In one of the first political science studies to incorporate such measures, it was shown that US citizens became more supportive of political violence if they were highly partisan, but only if they also had a callous, manipulative personality (Gøtzsche‐Astrup, Reference Gøtzsche‐Astrup2021). The general explanation for why few people do not go further is the strength of the taboo against violence, whilst the explanation for those that go beyond is possibly found in their extreme (dark) personality. These are individuals who are inclined to circumvent and, in some cases, rebel against the violence taboo (see, e.g., Berntzen & Ravndal, Reference Berntzen and Ravndal2021). This leads to our final expectation.

Expectation 4: Citizens scoring higher on dark personality are more likely to condone violence.

Cases: The United Kingdom and Norway

We field our measures and test our hypotheses in two contexts: Norway and the United Kingdom. Both are comparatively wealthy, industrialized and stable democracies in which political identity can be expected to be an important identity marker (e.g., Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021; Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Iyengar, Walgrave, Leonisio, Miller and Strijbis2018). When delving down, however, Norway and the United Kingdom represent contrasting levels of affective polarization within the subset of European countries, ranking among the least and most polarized, respectively (Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). Hence, the selection of these two countries allows us to observe whether these new measures (which we expect to be a priori relevant in European systems at large) have merit at different points of the empirical distribution of affective polarization (our crucial independent variable). In other words, do the items still yield variation in a context of less polarization (Norway) as well as in a more polarized polity (the United Kingdom)? While these two cases secure pivotal variation on the independent variable of concern, other cases could have been selected that fit the same criterion. For cases with lower affective polarization scores, Norway is comparable to countries such as Finland, Lithuania, and the Netherlands, while the United Kingdom has similar levels of polarization as France, Italy and Poland (Wagner, Reference Wagner2021).

Because of differences in sampling strategies, and some divergence in question wording, we are careful not to make exact comparisons of the levels of escalating polarization we find in the two contexts. The most substantial difference is that the feeling thermometer (the indicator of affective polarization) refers to the parties in the United Kingdom but to the supporters of these parties in Norway. Responses towards these two types of items are clearly correlated (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021) but citizens tend to report more dislike towards elites than voters (Druckman & Levendusky, Reference Druckman and Levendusky2019), hence possibly inflating the observed level of affective polarization in the United Kingdom. For the other items, most of which were equivalently worded, comparisons of aggregate patterns are less problematic, although point estimates should still be interpreted with caution given differences in sampling strategies (which is an opt‐in sample in the case of the United Kingdom, albeit a stratified and weighted one).

Our study does not aim to isolate the origin of any differences between the two countries, which, aside from the aforementioned sampling strategies, might stem from factors such as the timing of the survey, critical events and external shocks, the supply side (the parties on offer), or cultural or language differences affecting item responses. For instance, the survey in the United Kingdom coincided with the lead‐up to Brexit, which led to the formation of new political identities that partially crosscut the more traditional party affiliations and existing patterns of affective polarization (Hobolt et al., Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021). In terms of other critical events, the terrorist attacks in Norway on 22 July 2011 continue to reverberate within the nation's collective consciousness. The assailant, once affiliated with the Progress Party, invoked elements of the anti‐Islamic discourse that the Progress Party had brought into the mainstream to justify his attacks, thereby amplifying existing partisan tensions with some on the opposing side arguing that the Progress Party was morally or otherwise responsible in some way (Berntzen, Reference Berntzen2020).

Hence, our objective is not to draw direct comparisons between cases. Instead, we view any convergence in patterns between the two cases as an indication that, plausibly, similar patterns may exist in other European societies as well. Lastly, we do not make any assumptions about generalizability in cross‐country construct convergence to non‐democracies or societies where factors such as ethnic identity might take precedence over political identity.

Data and measures

Data

The measures were first fielded among 1133 Norwegian citizens as part of wave 18 (May 2020) of the Norwegian Citizen Panel (NCP).Footnote 1 This is a population‐representative survey panel conducted by the DIGSSCORE facility of the University of Bergen. We then re‐fielded the survey among a sample of 1600 nationally representative and politically weighted UK residents (excluding Northern Ireland) in December 2020 by YouGov in their Political Omnibus panel section. Because more space was available in the latter survey, the set of items was expanded. Most importantly, in the United Kingdom, we aimed to increase reliability and variation by fielding multi‐item batteries for the main concepts of avoidance, intolerance and support for political violence. These differences in measurement might yield differences in point estimates and correlations. In relation to the former, we only explicitly compare questions that use the same wording. In relation to the latter (as well as in response to the comparability issues discussed above), we refrain from interpreting differences in correlations in substantive terms. All replication materials are available at https://osf.io/mv5bf/.

Measures

In this section, we briefly discuss our operationalization choices. Appendix A (online) provides the complete wording of all measures. Most items mention an explicit political outgroup, derived from a question asking which political group of party supporters the respondent ‘[feels] furthest from’. All follow‐up items refer to the supporters of the particular party respondents singled out as the one they felt furthest from. For example, Norwegian respondents indicating they feel furthest from the Progress Party (FrP) are asked about their emotions, intention to avoid, intolerance, etc. towards ‘supporters of the Progress Party’, whilst those who indicated they felt furthest from the Labour Party (Ap) would be asked the same questions, but in relation to Labour Party supporters.

The feeling thermometer was measured on a 1–7 scale, ranging from ‘intensely dislike’ to ‘intensely like’. This departs from most previous studies that employed either a 1 (dislike) to 10 (like) or a 0 (cold) to 100 (warm) scale. This was necessary to be compatible with existing thermometer batteries in the NCP, and the UK questionnaire was fielded with the same scale for reasons of consistency. To still yield as much variation as possible, the end points were stretched to a more extreme wording than ‘merely’ disliking or feeling cold. Still, the lower available range of the scale likely downplays correlations with other constructs, especially those measured in a fine‐grained manner. However, this does not prevent us from comparing how strongly the thermometer correlates with different constructs. In the United Kingdom, this feeling thermometer was asked in the same wave and refers to the ‘voters’ of a party, whereas in Norway it was included in the preceding wave and refers to the ‘party’ rather than its ‘voters’. As noted, the latter is somewhat more remote from our ‘horizontal’ understanding of affective polarization, but widely used elsewhere (Wagner, Reference Wagner2021) and correlated with such ‘horizontal’ evaluations (Harteveld, Reference Harteveld2021). These differences in timing and wording likely suppress correlations in Norway compared to the United Kingdom, but again do not preclude comparisons between constructs.

Discrete emotions were measured using a battery asking respondents to indicate ‘how people that support [furthest away party] make you feel’, asking them to rate the three emotions of ‘angry’, ‘afraid’ and ‘disgusted’ on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extreme).

Avoidance was measured in Norway using an item about whether one would feel upset at obtaining a political opponent as a son‐ or daughter‐in‐law (going back to Bogardus Reference Bogardus1926, and later applied by Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012), whereas the UK survey additionally included items about avoiding conversations with, and events attended by, out partisans. These ask the respondent to reflect on behavioural intentions and hence are more consequential. Intolerance was measured using a standard approach adapted to political outgroups. Respondents indicated whether out partisans were allowed to rent a meeting venue, campaign or (in the United Kingdom only) to become a teacher in the respondents’ local area.

Political violence was originally measured with items in Norway about the acceptability of either threatening with or using violence. This turned out to yield (even) less variation than anticipated, so in the United Kingdom we partly replaced these with items proposing more concrete scenarios, such as using violence when the opposing party were to enter government or interrupt an in‐party meeting. We also included a form of non‐physical violence: targeting out partisans online in a way that makes them feel unsafe. As noted by Westwood et al. (Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022), inattentive respondents especially might overstate their support for violence. Because our main goal is to assess correlations rather than point estimates, this is less problematic for our purposes.

The measure of Manicheanism was based on Hawkins et al. (Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2019) and consists of items such as ‘our society is at a crossroads and there is only one correct way to go’. (Generalized) relative deprivation is measured using items such as ‘When compared to others, people like me do not get what we deserve’. Dark personality is measured using the so‐called Dark Triad Dirty Dozen Personality Trait Index (Jonason & Webster, Reference Jonason and Webster2010).

Validation

To investigate whether the items measure their intended constructs, online Appendix C presents confirmatory factor analysis models performed on both datasets. First, we loaded all emotion, avoidance, intolerance and political violence items on a single latent construct. If a single trait would underpin these various negative outgroup evaluation items, we should find this model to have a good fit. However, the model fit turns out to be unsatisfactory (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] of 0.29 [UK] and 0.35 [NO]). In the second step, we loaded all items on their respective intended latent construct while allowing correlations between the latent constructs. This second model does show a good fit (RMSEA < 0.05).Footnote 2 This model also outperforms models that combine latent constructs of highly residually correlated items. Hence, we conclude there is merit in our operationalization of the separate concepts. We continue our main analysis with scale scores for each concept (calculated as the unweighted average), with the exception of the emotions (as we expect different patterns per discrete emotion).

Analysis: Predicting norm‐breaking escalation

Below, we start with the descriptives of the individual items, before moving to analyses pertaining to the two goals of this study. First, we assess whether indicators of the alleged consequences of affective polarization correlate strongly with the feeling thermometer. Second, we test a broader set of expectations regarding the predictors of avoidance, intolerance and political violence.

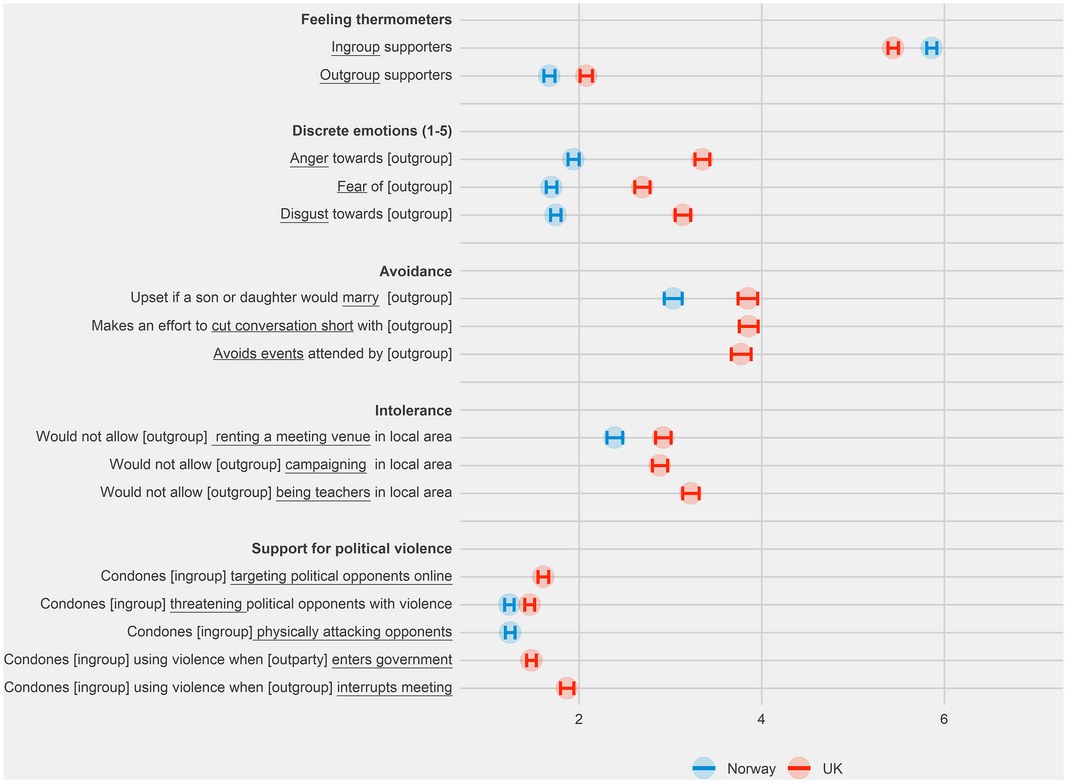

Descriptives

We first turn to the descriptives of the original items. Figure 2 provides the mean scores per item (online Appendix D provides the full distributions). While (as noted) comparisons in point estimates between the two cases should be interpreted with the utmost caution, it is nonetheless striking that the estimates are in several cases substantially higher in the United Kingdom than in Norway (which, as noted, would dovetail with country differences in feeling thermometers). Crucially, this is also the case for several items that were asked using exactly the same items across the two samples. That is, whereas a majority of Norwegians report very low anger, fear or disgust towards those supporting a party they dislike, around a quarter of British respondents report ‘extreme’ anger and disgust and one in five reports being ‘extremely’ afraid. A majority of British respondents report moderate or extreme distress at the prospect of obtaining a family member supporting a disliked party, while in Norway less than a third reports a similar avoidance. On the shared items regarding intolerance and acceptance of violence, differences between the descriptive scores (which appear slightly higher among the British) are too small to make inferences. At any rate, it should be noted that a vast majority in both countries disapprove of any violence. Still, while only around 7 per cent of British respondents find any of the forms of violence to some degree acceptable, it is notable that an additional 7 per cent claims to find at least one form of violence ‘neither acceptable nor unacceptable’, which is arguably already a potentially worrying response.

Figure 2. Mean scores on main variables, Norway and the United Kingdom. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: With 95 per cent confidence interval.

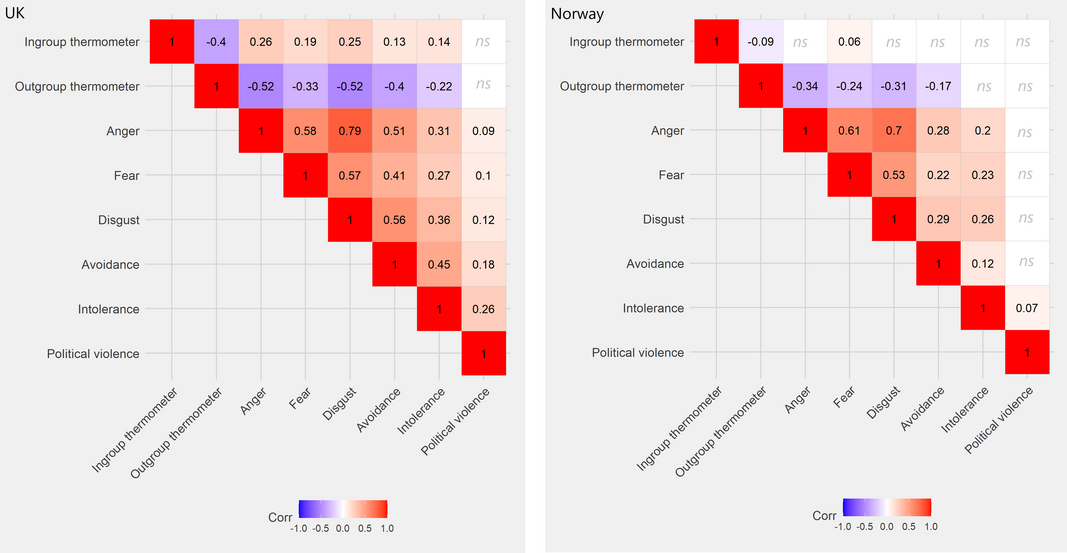

Correlation matrix: Do consequences correlate with the feeling thermometer?

In the remainder of this section, we discuss two questions. First, to what extent are emotions, avoidance, intolerance and support for political violence associated with the go‐to measure of the feeling thermometer? Second, what alternative predictors are associated with these outcomes? To gauge the first question, Figure 2 provides the correlation matrix for both samples (using the scale scores). Although our main interest lies with the correlations between the outgroup thermometer and the three alleged consequences, for comparison we also include the other main constructs. When comparing the correlation between the outgroup thermometer (second row) with avoidance, intolerance and support for violence, it becomes clear that associations with the outgroup feeling thermometer become progressively weaker for more extreme consequences. Warmer feelings towards outgroups (i.e., higher scores on the feeling thermometer) show a rather weak correlation with avoidance: −0.4 in the UK and −0.17 in Norway. It is again weaker (or even absent) for intolerance (−0.22 in the United Kingdom, insignificant in Norway). Neither country sample shows a significant correlation between the feeling thermometer and support for violence. These rapidly descending correlations remain striking. These patterns show that there are limits to the extent that scholars of polarization can rely on feeling thermometers to infer avoidance and in particular intolerance or political violence.

Before moving to a multivariate test of the predictors of avoidance, intolerance and support for violence, it is worthwhile looking at Figure 3 and noting that – in almost all cases – discrete emotions correlate more strongly with these outcomes than the feeling thermometer. It is also striking that these distinct emotions are themselves only moderately correlated with the thermometer (between −0.31 and −0.52, more so with anger and disgust than with fear). This is noteworthy since the feeling thermometer has long been argued to capture a general affective response. This divergence might explain some of the limits of the generic feeling thermometer in explaining all alleged consequences. We now turn to a systematic test of this broader picture.

Figure 3. Bivariate correlations between (scale) scores. Left, United Kingdom; right, Norway. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: ‘ns’ denotes a non‐significant effect at the 95 per cent level.

Multivariate regression: What predicts avoidance, intolerance and support for violence?

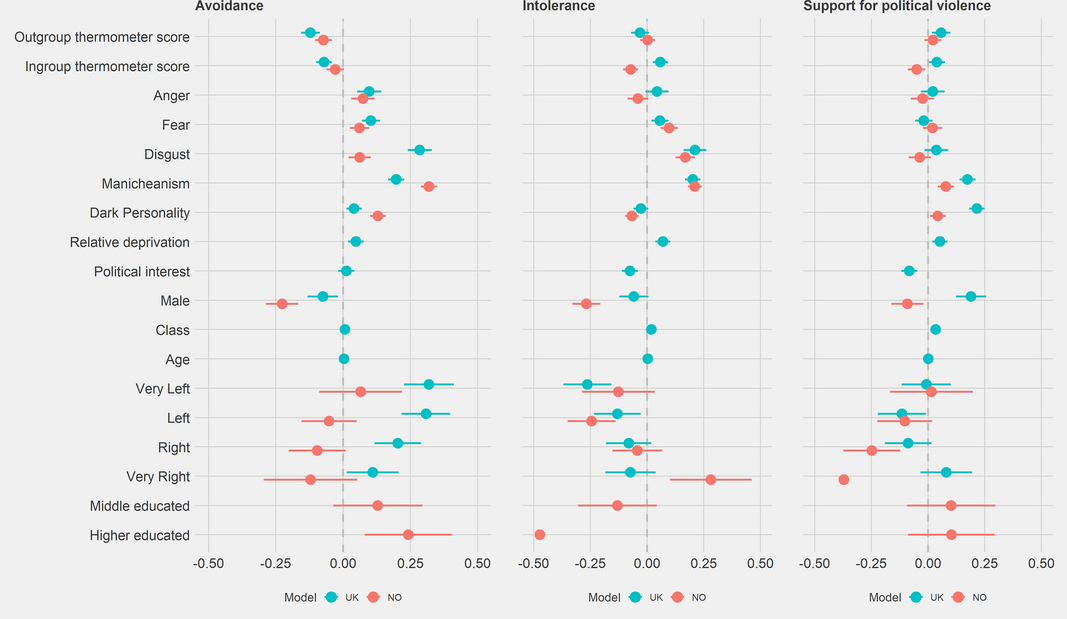

Given the moderate correlations with feeling thermometers reported above, what other factors might predict citizens’ avoidance and (especially) intolerance and support for political violence? Earlier, we expected the latter two of these outcomes, in particular, to depend on, first, the nature of the discrete emotion and, second, traits and predispositions. Figure 4 presents coefficient plots of separate regression models for the three outcomes. Full models are reported in online Appendix D. In each case, the outcome is predicted by the explanatory variables just mentioned, and a set of socio‐demographic and political control variables. We also include the feeling thermometer score towards the ingroup and the thermometer score towards the outgroup, to assess the role of the strength of identification with the political group and any residual (i.e., not captured by the distinct emotions) ‘generalized’ dislike of the outgroup. All continuous variables were standardized to ease a comparison of effect sizes.

Figure 4. Predictors of avoidance, intolerance and support for political violence. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: With 95 per cent confidence interval. UK, United Kingdoml NO, Norway.

The coefficients of the thermometer score variables replicate the main takeaway of the correlation matrix: reported sympathy towards the political outgroup (i.e., outgroup thermometer score) has only a modest negative relation with avoidance, and (controlling for other variables) hardly any residual association with intolerance or support for political violence. One might argue that a specification including both the generic feeling thermometer and specific discrete emotions is overdetermined. However, we note that the correlation between the thermometer and the discrete emotion items is far from perfect (between −0.24 and −0.52), and that the weak effect of the thermometer on avoidance replicates the bivariate correlation reported in Figure 3. In fact, in the case of support for political violence, the coefficients of outgroup warmth are even closer to being positive – that is, political violence is condoned by those relatively mild towards opponents. Even allowing for the difficulties involved in measuring support for violence (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022), this pattern shows that the low sympathy scores reported in cross‐national surveys cannot automatically be extrapolated to indicate more nefarious forms of escalation. In the Discussion section, we reflect on the implications this has for attempts to operationalize affective polarization.

The discrete negative emotions of anger, fear and disgust do a better job than feeling thermometers at predicting avoidance and intolerance. They too, however, have little predictive power when it comes to support for political violence. In terms of each individual discrete emotion, we do find some evidence of a pattern of engaging versus disengaging, although the picture is more complex. We expected that avoidance would be predicted by the disengaging emotions of fear and disgust (Expectation 1A), and this is confirmed for both these discrete emotions. In the United Kingdom, disgust is even the second strongest predictor of all included variables. At the same time, the engaging emotion of anger also predicts avoidance to a similar degree. In the case of intolerance, we expected disgust to be the key emotive predictor (1B). This is confirmed by the model. Disgust is one of the strongest predictors of intolerance in both samples, outperforming fear and anger. In fact, in the Norwegian sample anger is even associated with less intolerance. In the case of political violence, none of the discrete emotions shows a significant relation. All of this points to limits of relying on notions and measures of ‘generalized’ dislike. While affective polarization is often equated to stand for hate and anger in both academic prose and everyday examples, anger is not the most consistent predictor here – for instance, in the case of intolerance, disgust might be a more consistent motivation. This paints a very different picture of polarized citizens’ experiences, and – as we discuss in the concluding section – calls for rethinking the generic theoretical notion of affective polarization itself.

Next to refining dislike, we argued that citizens’ traits and dispositions should have an important independent association with intolerance and support for political violence. Figure 4 confirms that such effects are present for all three constructs under study, including avoidance (despite involving breaching a weaker societal norm). Of the three traits and dispositions, Manicheanism is consistently among the strongest predictors (or even the single strongest predictor) of each consequence. Seeing the world in moral black‐and‐white terms strongly predicts avoidance, intolerance as well as – and this is especially striking, given the consistent null‐findings so far – support for political violence (Expectation 3). Moving from dislike to (already) avoiding and other outcomes hence requires looking at politics through a moral lens. Perceived relative deprivation, included only in the United Kingdom, is a steady, albeit moderately strong predictor, as noted also extending to avoidance (Expectation 2). Finally, dark personality was expected to predict support for political violence, which it does in both samples and to an especially large degree in the United Kingdom. In fact, it is the single largest predictor of support for political violence in the United Kingdom. It should be noted that we find these consistent associations in models controlling for arguably more proximate variables such as thermometer scores; hence, underlining these traits and dispositions has an important independent predictive power (including for avoidance). As we will discuss in the concluding section, this should urge the field not to focus only on directly ‘political’ variables, but also include traits and dispositions, when trying to understand polarization and its consequences.

Before moving to a broader discussion of all these findings, we note several interesting patterns among the control variables. First, the higher educated are more likely to avoid political outgroup members, but less likely to be intolerant or condone political violence. This might reflect their greater involvement in and importance attached to politics (creating an urge to separate themselves socially from outgroups) but perhaps also a greater awareness of social taboos concerning intolerance and violence. Indeed, political interest is associated with less intolerance and support for political violence, even though it is generally associated with more affective polarization (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012). The coefficients for ideology provide diverging patterns too: avoidance is associated with the left, intolerance with the right, and support for political violence with the far left and far right (and, interestingly, centrists). Hence, ideology and extremity can work in different directions depending on the outcome. Effect sizes are similarly mixed for gender. Men are much more likely to condone political violence in the United Kingdom but less likely to be avoiding or intolerant. The fact that effects often go in opposite directions depending on the outcome of interest (affective polarization proper, avoidance, intolerance, or support for political violence) should urge caution when extrapolating insights from individual‐level correlates to a range of polarized outcomes. After all, the ‘usual suspects’ to signal – say – intolerance or political violence are different from those that are affectively polarized or avoid political opponents.

Discussion and conclusion

The academic study of affective polarization is a young enterprise that has made substantive advancements within a short amount of time. Whereas concerns that affective polarization may have dire consequences is a consistent backdrop in this literature, it had long been treated as a sort of Pandora's box, postulated to cause a great many harmful outcomes without further inquiry. It is only recently that scholars of affective polarization have begun to investigate this in earnest. Thus far, this has predominantly happened in a piecemeal manner with studies limiting themselves to specific outcomes such as social distancing (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2020), support for violence (Kalmoe & Mason, Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022) or democratic norms (Kingzette et al., Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021), and virtually all these studies are restricted to the United States, which is in many ways a peculiar case. We build upon these earlier studies by further integrating the study of affective polarization with other domains of social scientific knowledge – that of intergroup emotions and political extremism – and advance the conceptual development and understanding of the possible downstream, norm‐breaking consequences of avoidance, intolerance and support for violence against the other side.

Our attempt to measure these constructs in the low‐polarization context of Norway and the high‐polarization context of the United Kingdom shows they can be measured validly and (except for support for violence) yield substantive variation. In both cases, one thing that stands out is that the correlation between the feeling thermometer (i.e., ‘disliking’ the political outgroup) and the consequences becomes weaker as they ramp up in intensity. Large swaths of society appear to experience dislike – and even anger, fear and/or disgust – without practicing avoidance or intolerance towards their political opponents or wishing them harm. Some do so, however. Our results show that citizens experiencing disgust towards the outgroup are more likely to signal avoidant, intolerant or violent tendencies, as are those with a Manichean outlook on politics and (to a somewhat lesser degree) those who report experiencing relative deprivation. Citizens with dark personality traits are likely to avoid and support violence directed towards their opponents, yet they are not necessarily intolerant. The important takeaway is that not all citizens ‘escalate’ beyond negative affect in either the general or specific sense: there are distinct characteristics held by some which make them prone to accept the violation of moral codes which govern social cohesion, and these differ from the usual explanations for ‘mere’ outgroup dislike.

These findings have theoretical, normative and methodological implications for the study of affective polarization and its consequences. First, on the theoretical level, it points to a tentative general model where the core component associated with affective polarization (negative outgroup affect) can be placed at a relatively early level. While our cross‐sectional study does not allow for assertions about causality, this claim is made plausible by the finding that low thermometer scores are empirically distinct from more severe forms of outgroup derogation and that the latter have their own distinct predictors. This does not mean that outgroup dislike is unimportant. Rather, we argue that it is part of a broader understanding where some individuals combine ‘merely’ disliking with stronger emotional reactions and some advance from there to adopting increasingly extreme positions towards adherents of the opposing political faction(s). Hence, as a heuristic, one might think of escalating polarization as a sort of ‘stepping ladder’, where exogenous factors push some citizens from one step to the next. The last step on the ladder includes the (arguably harmful) three main concepts that were the object of this study. These are grounded in previous steps, but not perfectly so. In the first step, citizens begin to develop a political‐social identity. And as this strengthens, a subgroup of those citizens develops antipathy towards the outgroup through intergroup comparative processes, and these might be exacerbated by perceptions of injustice, or relative deprivation. Our findings suggest that whether citizens advance further and adopt intolerant and pro‐violent positions is largely dependent on their individual predispositions and personality. Whilst this model of escalating polarization is certainly not exhaustive, future research on affective polarization might benefit from starting such escalation models suggested by the political radicalization literature and gauging the temporal and causal order of these relations.

Second, these findings have important implications for our normative assessment of affective polarization. Depending on one's appreciation of the scope and nature of conflict in democratic societies, it remains open to discussion whether strong antipathy between citizens is inherently problematic. Affective polarization might even signal a (re)energization of politics that counters the general decline in partisan purpose and the concomitant rise in apathy, often identified as one of the most pressing ailments in Western democracies not too long ago (e.g., Mair, Reference Mair2013). When it comes to the normative assessment of affective polarization's consequences, our study certainly gives way to a more nuanced understanding. We observe that many citizens hold antipathy towards their political opponents without reporting a strong inclination towards avoiding them, being intolerant or condoning political violence (for other studies also nuancing the view of affective polarization as exclusively negative; see, e.g., Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022; Mélendez & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Meléndez and Kaltwasser2021). Speaking to this meta‐debate on polarization, the challenge for democracies then is to allow for the constructive existence of the former (partisanship) without giving rise to the latter (segregation, intolerance and violence). Such a ‘middle‐of‐the‐road’ approach might be more fruitful than attempts to eliminate affective polarization per se.

Third, our findings have crucial methodological implications for the way we study affective polarization – particularly our reliance on feeling thermometers and related generalized measures. Thermometers have been enormously successful in measuring the negative affect on political outgroups and expanding our knowledge of individual and societal variation therein. But such patterns cannot be unambiguously extrapolated to verdicts about the way society and democracy are impacted. Scholars interested in intolerance and violence – and other plausibly related phenomena – might want to explicitly measure these constructs. In addition, we show that the thermometer picks up on a mix of different discrete emotions and imperfectly so. Unpacking 'dislike’ is important because we show that discrete emotions are relevant when considering the implications of partisan hostility. What is particularly striking is that although scholars of affective polarization have alluded to ‘anger’ likely being the driving emotion beneath the ‘negative affect’ between partisan groups (e.g., Mason, Reference Mason2013), in our results disgust (and in some cases fear) appears pivotal in understanding escalating polarization. Put simply, what may have performed sufficiently to study affective polarization as a dependent variable may not provide enough insight into the concept's nuance once it is treated as an independent variable.

There are limitations to the present study. Starting off, measuring support for violence while securing sufficient variation proves challenging. Whilst it is certainly positive that few people indicate they support violence, attention should continue to be paid to developing valid and reliable measures of the concept, addressing social desirability bias (Westwood et al., Reference Westwood, Grimmer, Tyler and Nall2022). In addition, the measurement of the discrete emotions was likely hampered by the reliance on single‐item indicators, which might have created pollution by generalized affect (Rhodes‐Purdy et al., Reference Rhodes‐Purdy, Navarre and Utych2020) which would artificially increase their correlation, leading to an underestimation of their distinct effects. Future studies which aim to unravel the ‘affect’ of affective polarization ought to explore more comprehensive emotional assessments. Moreover, our cross‐sectional data has limits in establishing the causal relation between constructs, and the field would benefit from more experimental research testing the causal link between affective polarization and presumed downstream effects (see, e.g., Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Westwood2022).

Finally, and perhaps most prominently, while being the first to systematically study the impact of affective polarization on European societies, this study has only addressed the 'horizontal’ consequences of affective polarization – that is, interpersonal relations. Open questions remain about the 'vertical’ consequences: how is affective polarization impacting European citizens’ relation to democratic norms and political elites, and which factors lead to escalation on that account? Answering this question is crucial to know if the oft‐expressed worries about polarization harming democracies are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the anonymous reviewers for their excellent comments. Earlier versions of this manuscript were presented at the ECPR General Conference, the Nordic Conference on Violent Extremism, the DIGSSCORE seminar and the Dutch‐Flemish Political Science conference and we thank all those who provided feedback on those occasions. This research was supported by the Research Council of Norway (grant 275308), the Swedish Research Council (grant 2018‐01468) and the Dutch Research Council (grant 016.Veni.195.159).

Data Availability Statement

All data files and scripts are available in the OSF repository at https://osf.io/mv5bf/.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix A Question wording

Appendix B Confirmatory factor analysis

Appendix C Distribution of main items

Appendix D Regression models