1.1 Why This Book?

Nonhuman animals, hereafter “animals,” are omnipresent in human life. They provide us with food and clothing, they are used in research, and they offer entertainment and companionship. And of course they are everywhere in the world.

This book proposes an economic analysis of animals and their welfare. But let me ask first: Is animal welfare a pertinent subject for an economist? A basic answer is to recognize that the suffering experienced by animals is often predominantly influenced by economic factors. Animal agriculture provides a good illustration. Over the past century, we have witnessed a marked intensification of industrial animal agriculture. The cause of this evolution is clear: efficiency gains. In the present day, on a global scale, over 80 percent of farmed animals find themselves in factory farms. Deprived of basic elements like sunlight, fresh air, free movement, and natural behaviors such as mating, these animals are denied what we consider essential components of a normal life. Throughout their existence, they endure a persistent state of low welfare precisely because humans get an economic benefit from that situation.

But this raises a much more general and much more difficult question: Is animal welfare an important issue? The state of the world is concerning on multiple fronts. Hundreds of millions of people still live in extreme poverty, there are wars in multiple parts of the world, and the looming threats of climate change and biodiversity loss could greatly affect future generations. The answer to this question depends on how to judge what is “important,” and in particular whether we should care about animals while there is such a huge amount of human suffering in the world. Reflecting on this judgment is very difficult and even controversial, but this is precisely one major objective of the research program on the economics of animal welfare.

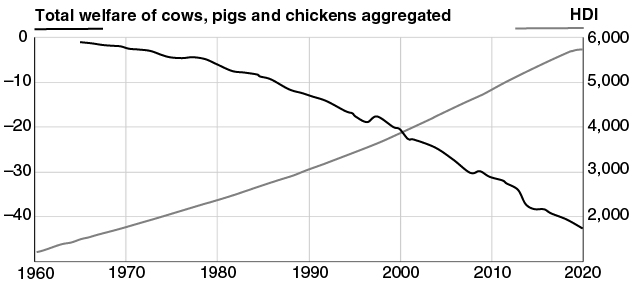

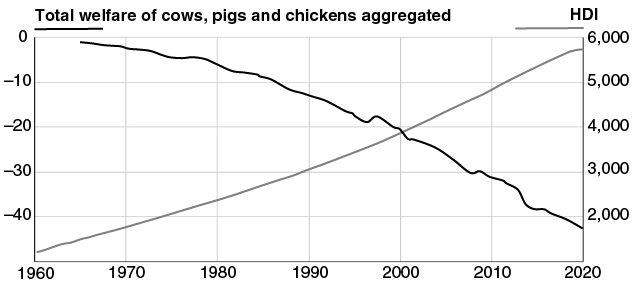

For economists, the key metric for assessing what matters is welfare. As illustrated in Figure 1.1 (black curve), the global welfare of major categories of farmed land animals – chickens, pigs, and cows – exhibits a negative trend. This figure is derived from data provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and uses a welfare assessment method that will be detailed in Chapter 10. The observed decline in animal welfare parallels the surge of industrial farming over the last sixty years. This trend reflects the changes in the number of animals raised for food. Since the early 1960s, the quantity of animal-based food production, and consequently the number of animals, has increased drastically. For instance, the average annual chicken consumption in the United States has increased from less than 10 pounds to about 70 pounds per person. This trend shows no signs of stopping. This book will extensively discuss not only the “quality” of animal lives but also the “quantity” of animal lives, namely the number of animals that we produce for food.

Figure 1.1 Global welfare of farmed animals over time (black curve) and Human Development Index (HDI) over time (gray curve).

See Chapter 10 for more information about how this figure has been created.

Figure 1.1Long Description

The image is a combination line graph with two data series. The x-axis represents time from 1960 to 2020, while the left y-axis indicates the total welfare of farmed animals from 0 to −50, and the right y-axis denotes the Human Development Index HDI from 0 to 6000. One line shows a negative trend in the welfare of cows, pigs, and chickens, starting near 0 in 1960 and decreasing to around −50 in 2020. In contrast, another line indicating HDI rises from approximately 2000 in 1960 to just over 5000 in 2020. The graph includes horizontal grid lines for improved readability.

The black curve on Figure 1.1 also highlights that overall global welfare of farmed animals is negative, based on the specific measure of welfare adopted in this book (again, more on this later). A negative welfare level essentially means that existence is worse than nonexistence, that life is not worth living. This observation thus strikingly indicates that, all else being equal, it would be better if these animals did not exist at all! This book will extensively discuss the notion of life worth living. This notion turns out to be instrumental in various theory parts. Furthermore, note on Figure 1.1 that total welfare is declining at an increasing rate, suggesting that the problem is rapidly worsening. This trend underscores a sense of urgency and calls for more policy action and more research.

For comparison, I have also included the evolution of the Human Development Index (HDI) over the same period; see the gray curve in Figure 1.1. The HDI is the most well-known index for measuring the overall development and welfare of humans, considering three main dimensions: health, education, and wealth. The figure shows the global HDI, which exhibits a consistently increasing trend. Note that regional HDI (Arab states, East Asia and the Pacific, South Asia, Europe and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa) also show increasing trends over the period. Hence, despite various catastrophic events in the world and mounting concerns on multiple fronts, human welfare has been steadily improving on average both globally and regionally. This upward trend starkly contrasts with the decreasing and concave pattern observed earlier for animal welfare. The point is that while the overall quality of life tends to improve for humans in the world, it has sharply deteriorated for animals, with human actions contributing to the decline of animal welfare.

This book will present how to model and quantify animal welfare in an economically meaningful manner, and even in a way that allows for a direct comparison with human welfare. It will make progress on the path to answer the question of the direct comparison of welfare of humans and animals, and in particular whether animal welfare concerns are important compared to human welfare. As a preview, our preliminary calculations suggest that the animal welfare costs associated with intensive animal production far exceed its economic benefits for humans, often by several orders of magnitude (Espinosa and Treich Reference Espinosa and Treich2024). In a nutshell, this research suggests that intensive animal production should essentially be phased out.

This result should not come as a surprise. When we seriously consider the welfare of animals, we confront the reality of billions and billions of animals enduring extremely low levels of well-being. At its essence, economists’ calculations thus acknowledge that the consumer surplus derived from meat consumption pales in comparison to the interests of other animals. In other words, the fleeting pleasure of consuming meat is “relatively trivial by comparison with the interests of, say, a pig in being able to move freely, mingle with other animals, and generally avoid the boredom and confinement of factory farm life” (Singer Reference Singer1980, page 333). To put it bluntly, industrial farming condemns animals to lives of boredom and suffering in exchange for saving a few cents per kilogram of meat, and thus in exchange for a trivial gain in human welfare. This means that the loss to animals seems completely disproportionate compared to the gain to humans. Of course, such a strong claim needs to be carefully explored and assessed, and this determination is precisely one of the objectives of the book. In particular, a key question is whether a compromise can be found between the interests of humans and animals.

Furthermore, note that the impact of humans on animals is not limited to farmed animals. Many human actions and policies, directly or indirectly, affect animals and their welfare. Consider climate policy, for example. Climate change affects animal habitats, migrations, and food availability, as well as potentially increasing disease and parasite transmission. Simply put, climate change profoundly affects nature in general and animals in particular (Parmesan Reference Parmesan2006, Ripple et al. Reference Ripple, Whalen and Wolf2024). It therefore seems important to consider climate impacts on both humans and animals and then explore optimal climate policy in an integrated nonanthropocentric framework (Budolfson and Spears Reference Budolfson, Spears and Portmore2020).

Other domains are also worth investigating. In biomedical research, the use of animals raises ethical questions about their treatment and whether the expected benefits to human health outweigh the costs in terms of animal welfare. Is it acceptable that animals are used in research for some relatively “minor” human health issues, such as alopecia (hair loss) in aging men? Should we stop animal research on a specific disease if it has not proven effective for decades, or if the probability of discovery is ex ante very small? These are difficult questions. The tradeoff becomes particularly challenging when considering alternative methods, such as in vitro testing or computer simulations, which can reduce or eliminate animal suffering but are not yet fully capable of replicating the complexity of living organisms.

As another example, consider conservation policies that involve culling invasive species to restore native ecosystems. Animal welfare is typically an overlooked aspect of these policies. Killing animals in the name of conservation is morally problematic because the life of any individual animal matters morally. The evaluation of these policies should thus consider the tradeoff between the benefits to biodiversity and the negative impact on the welfare of the affected animals.

Overall, the impact of human activities on animal welfare is immense, yet it remains significantly overlooked. This oversight extends not only to the field of economics but also to many other domains. For instance, it is particularly concerning to see major environmental frameworks, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the Earth System Boundaries literature, pay almost no attention to the issue of animal welfare. These initiatives aim to address global sustainability, yet they fail to account for the welfare of billions of sentient beings affected by human actions. That is, they fail from a moral viewpoint.

One major difficulty though is that we currently do not have the tools to quantify our impacts on animal welfare (Budolfson et al. Reference Budolfson, Fischer and Scovronick2023, Reference Budolfson, Espinosa, Fischer and Treich2024, Sunstein Reference Sunstein2024). This makes it difficult to assess and compare the welfare impacts of policies on animals and humans on a common scale, and thus to make informed and transparent tradeoffs. This perhaps also contributes to the source of the problem. When something is not counted, it eventually does not count. There is thus a need for the development of novel methods to integrate animal welfare into decision analyses. This integration would enable policymakers and various stakeholders to make more informed and ethical decisions that consider the welfare of both humans and animals.

More fundamentally, there is also a need to explore how existing economic theory can address the conceptual issues raised by accounting for animal welfare. Whether animal welfare is considered an externality, a public good, a merit good, or another economic concept, I will show how to apply or adapt standard economics principles to better understand animal welfare issues and, in particular, to design optimal policies. There is no need to start from scratch. It is essential to understand how existing tools, particularly those already employed in public economics and environmental economics, can be harnessed to advance our understanding of animal welfare. This theoretical aspect is likely the main contribution of this book to economics. It includes developing a simple model of animal consumption – what I call the “canonical model” – which is adapted several times to fit different economic concepts.

Another crucial aspect for economic research concerns the lack of understanding of how humans exactly care about animals. Opinion polls and survey studies often suggest that citizens care a lot about animals in general. However, the situation is complex. According to Faunalytics, only about one-quarter of United States donors donate to animal causes (https://faunalytics.org/giving-to-animals-new-data-who-how/). Moreover, donations to animal-related organizations are mainly directed toward companion animal shelters and protection, with much less attention given to noncompanion animals. Research by Animal Charity Evaluators indicates that farmed animals receive less than 1 percent of total donations to animal charities, despite representing more than 99 percent of domesticated animals globally (https://animalcharityevaluators.org/donation-advice/why-farmed-animals/). Why do people seem to care about some animals and not others?

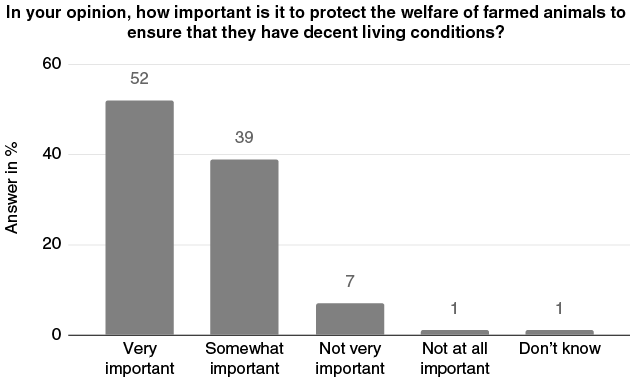

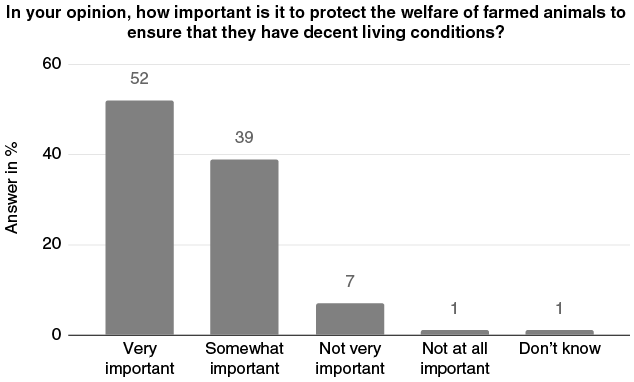

Even for a specific category of animals such as farmed animals, people’s behavior is not easy to decipher. Consider, for instance, the opinion survey based on more than 20,000 participants in the European Union: A large majority of Europeans (91 percent) agree that it is important to protect the welfare of farmed animals (Eurobarometer 2023) (see Figure 1.2). However, market data often provide a very different picture. Typically, the demand for animal-friendly products in food markets is very limited. Overall, the “gap” between public opinion and market demand when it comes to animal welfare is a complex issue that likely involves a variety of psychological, social, political, and economic factors. Further research, in particular research in behavioral economics, is needed to better understand these factors and develop strategies to bridge this gap and improve animal welfare.

Figure 1.2 European citizens’ agreement about the importance of protecting farmed animals.

Figure 1.2Long Description

The image presents a vertical bar graph with a horizontal axis labeled with response categories related to the welfare of farmed animals and a vertical axis indicating percentage values from 0% to 60%. The tallest bar, representing “Very important,” reaches up to 52%, followed by “Somewhat important” at 39%. The bars for “Not very important,” “Not at all important,” and “Don’t know” are smaller, at 7%, 1%, and 1% respectively. The graph highlights survey results about attitudes toward animal welfare.

Presently, the economic literature on animal welfare is scarce, and essentially limited to studies on the willingness to pay (WTP) for animal welfare and on the production cost to improve animal welfare (Bennett Reference Bennett1997, Lagerkvist and Hess Reference Lagerkvist and Hess2010, Norwood and Lusk Reference Norwood and Lusk2011, Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Kehlbacher and Balcombe2012, Grethe Reference Grethe2017). This literature is published in field journals in agricultural or environmental economics. In the “top- 30” journals in economics, only three papers contain “animal welfare” or “animal well-being” in the title or abstract (i.e., Blackorby and Donaldson Reference Blackorby and Donaldson1992, Fleurbaey and van der Linden Reference Fleurbaey and Van der Linden2021, Mechtenberg et al. Reference Mechtenberg, Perino, Treich, Tyran and Wang2024), and not a single paper contains basic keywords such as “vegetarian,” “vegan,” “sentience,” “anthropocentrism,” or “speciesism” (based on a search at https://econ-paper-search.streamlit.app/ in December 2024). Other fields, such as animal ethics and animal rights law, are already well developed in philosophy and law, respectively. A similar trend should follow at some point in economics. The inclusion in 2023 of new entries K38 (Animal Rights Law) or Q18 (Animal Welfare Policy) in the Journal of Economic Literature classification is an indication that the economics profession is becoming increasingly interested in this area.

The existing literature on animal welfare, predominantly found in philosophy, law, and animal sciences, has undoubtedly generated a vast repository of valuable knowledge. However, it often lacks in terms of economic arguments, despite economics being at the very core of the problem, as argued earlier. This point was eloquently made sixty years ago by Ruth Harrison, a pioneer and visionary of the farm animal movement, in her seminal book Animal Machines (Harrison Reference Harrison1964, cited in Bollard Reference Bollard2023): “if one person is unkind to an animal it is considered to be cruelty, but where a lot of people are unkind to animals, especially in the name of commerce, the cruelty is condoned and, once large sums of money are at stake, will be defended to the last by otherwise intelligent people.”

The centrality of economic aspects to the problem of animal welfare can be disheartening for the admirable animal advocacy community, which is often guided by moral arguments rather than economic logic. As some have argued, the actions of this community may have had only a modest and diffuse impact compared to the powerful influence of long-term economic and demographic trends (Weisskircher Reference Weisskircher2024). These trends include the rise of industrial farming, driven by the demand for affordable meat and animal products, the globalization of food markets, and the economic incentives that prioritize efficiency and profit over animal welfare. Despite the passionate efforts and moral convictions of animal advocates, their influence is frequently overshadowed by these larger economic forces, which shape industry practices and consumer behavior on a global scale. Consequently, achieving significant improvements in animal welfare requires addressing these underlying economic drivers and integrating animal welfare considerations into a broader economic framework.

In their influential book Zoopolis, Donaldson and Kymlicka (Reference Donaldson and Kymlicka2011) argue that traditional animal advocacy has been largely ineffective. They propose a new societal organization based on a redefined relationship with animals, including granting citizenship status to domesticated animals, sovereignty to wild animals, and denizenship to liminal animals (i.e., animals that live in and around human settlements). However, their visionary framework may sound quite unrealistic within the current societal structure. One critical oversight in their work is the economic feasibility of their model. Transitioning to a system where animals are granted various forms of citizenship and legal rights would require substantial financial resources, infrastructural changes, and ongoing maintenance.

The bottom line is this: Incorporating economic analyses and tools could make moral or political proposals more practical and actionable, ensuring that the changes envisioned are not only ethically sound but also economically viable. This approach is exemplified by the success of cage-free campaigns, which target producers instead of politicians, leveraging market forces to drive change. Overall, I contend that more research in economics is needed to better understand our attitude toward animals and our impacts on their welfare. There is currently a lack of cohesive integration between the literature in social, political, and human sciences and the literature in life sciences on animal welfare. It thus seems useful to establish a comprehensive and unified framework that encompasses the concepts developed in philosophy and other sciences in the humanities with the insights derived from animal welfare and cognitive sciences. Economics can play a pivotal role in achieving this synthesis.

Here is an illustration of this claim. In the canonical model of this book, I propose a simple normative model that encompasses parameters addressing the degree of antispeciesism (as discussed in the philosophy literature, see Chapter 2), another parameter that evaluates the relative weight of a species based on specific cognitive capacities (as explored in animal cognition, cognitive ethology, and comparative psychology), and an additional parameter that measures levels of animal welfare (as studied in the animal welfare sciences literature). This model can be calibrated and ultimately yields a monetary value for animal welfare that can be compared to other monetized costs or benefits for humans. As a result, various decisions or policies that affect animal welfare can then be quantitatively evaluated in a benefit-cost analysis. Moreover, the assumptions can be varied, and uncertainty may be introduced, to check the robustness of the evaluation.

The primary purpose of this book is thus to introduce economic concepts pertinent to the study of animal welfare, with the aim of accelerating the production of theoretical and empirical methods that incorporate animal welfare into economic analyses. I hope that this book will facilitate the creation and development of a novel field within economics, while fostering a more ethical approach to policymaking that considers the welfare of both humans and animals. This book aims to inspire economists, especially young scholars, by encouraging them to think about the role of animals in the economy and, for some, to pursue research on animals and their welfare. By doing so, it may contribute to nurturing a new generation of experts capable of addressing the intricate challenges arising from animal welfare in our present and future world.

Finally, I believe that the book also holds broader relevance for social and behavioral scientists as well as scholars in fields such as environmental, biological, or animal sciences who wish to gain insights into some economic aspects of the subject. This interdisciplinary approach not only enriches our understanding of animal welfare issues but also fosters collaboration among experts from various fields, ultimately advancing the objective of creating more effective and economically sound policies. In sum, it seeks to promote the use of economic methods in policy analysis, to identify gaps in current analyses and to encourage interdisciplinary collaboration to advance this objective.

1.2 Anthropocentrism in Economics

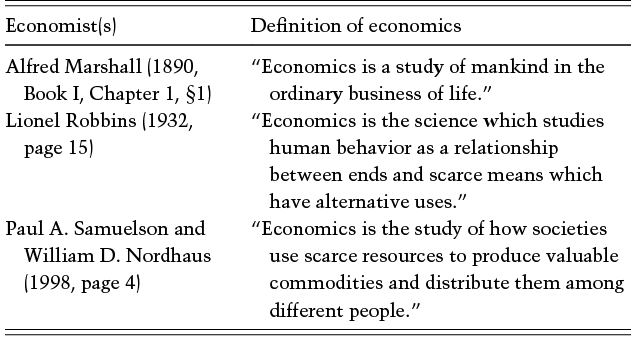

Economists study humans’ actions, humans’ beliefs, humans’ exchanges, humans’ strategic interactions, and so on. Buchanan (Reference Buchanan1964), for instance, defined economics as the study of exchange activities among human societies. Other well-known definitions, as listed in Table 1.1, are also explicitly human centered. But the key point is that economics is also centered on the welfare of humans. The complete citation from Marshall (Reference Marshall1890, Book I, Chapter 1, §1), which serves as the opening sentence of his classic work, highlights this focus on welfare: “Political Economy or economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment, and with the use of the material requisites of wellbeing.” To give another example, Angus Deaton, the 2015 Nobel laureate in economics, wrote in an op-ed that the proper basis of the economics discipline is “the study of human welfare” (Deaton Reference Deaton2022).

| Economist(s) | Definition of economics |

|---|---|

| Alfred Marshall (Reference Marshall1890, Book I, Chapter 1, §1) | “Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life.” |

| Lionel Robbins (Reference Robbins1932, page 15) | “Economics is the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” |

| Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus (Reference Samuelson and Nordhaus1998, page 4) | “Economics is the study of how societies use scarce resources to produce valuable commodities and distribute them among different people.” |

Hence, what matters in economics is a better understanding of human societies, and what matters normatively is human welfare. In short, economics is the study of humans, “for” humans. Economic studies consider humans as the sole wellspring of welfare, a phenomenon often referred to as anthropocentrism. Indeed, anthropocentrism means that humans alone possess moral value. Economists typically consider that humans, all humans, and only humans have moral value.

The assumption of anthropocentrism is almost universal in economics. One might think this assumption can be justified since economics primarily deals with issues unrelated to animals, allowing their welfare to be safely ignored in economic analyses. On the surface, this seems reasonable. What is the problem after all if research in finance or industrial organization, say, ignores animal welfare? Note however that many industries rely directly on animals (e.g., industries in food, clothing, and health), warranting some caution. Moreover, considering all the indirect impacts of human actions, as through the use of natural resources such as land, the impacts on animals seem potentially huge in many cases. Overall, the direct and indirect impacts on animals of human activities may be substantial. Actually, a recurrent theme in this book is that animals are often invisible (or rendered invisible), and the consequences of human actions on them are not even considered.

Perhaps more problematic is the fact that anthropocentrism is also the rule in other fields in economics such as environmental economics or agricultural economics, where animals are explicitly considered part of the research subject. For example, in economic studies of biodiversity, animals are usually viewed as protected species. However, in these studies the welfare of individuals in these species does not usually matter. At best, animal welfare only matters as a byproduct of biodiversity preservation. Similarly, farmed animals are simply inputs that contribute to agricultural production. In these fields, animals are perceived as mere “objects”: They are viewed as food, resources, or commodities. They are not acknowledged as individuals or sentient beings. In other words, the capacity of animals to experience pain or pleasure is simply ignored. Animal welfare is largely disregarded in environmental and agricultural economics.

In essence, the widely prevalent welfarist approach in economics, frequently advanced as a substantial normative asset of the discipline and the cornerstone of significant economic domains such as growth, optimal taxation, and climate or agricultural policy, harbors a critical flaw: It exclusively considers human welfare. Some readers may perceive this section as overly critical, assertive, or even unfair toward the discipline of economics. I understand that. However, I see this flaw as a major normative limitation within the discipline of economics. I believe it is important to emphasize this limitation forcefully because it has been the norm in the discipline.

I believe that a change is needed. It is not just a theoretical or conceptual problem. As the book will argue in some empirical parts (see, for instance, the computation of so-called animal welfare levies in Chapters 7 and 10), the policies that usual anthropocentric economic analysis recommends are often very far from maximizing total welfare precisely because they adopt this restricted view of welfare. Sometimes, a change in the policy modestly affecting the welfare of humans would drastically improve the welfare of animals. It is important to identify those policy changes that can really make a difference.

Animal welfare, in its own right, has thus not received proper attention in economics (Johansson-Stenman Reference Johansson-Stenman2018). At best, economists focus on how improving animal welfare can enhance consumer surplus, thus assigning instrumental value to animal welfare. The intrinsic value of animals has been overlooked in environmental valuation, which primarily relies on humans’ WTP and is thus rooted in anthropocentrism. It is important to note here that human preferences for animals may poorly align with the actual welfare of animals (Budolfson et al. Reference Budolfson, Espinosa, Fischer and Treich2024, Espinosa Reference Espinosa2024), undermining the effectiveness of an instrumental approach in improving animal welfare. Even attempts in environmental valuation to go beyond altruistic preferences, such as discussions on existence value, still remain entrenched in anthropocentrism by relying on human preferences regarding the existence of animals or other species.

The spectrum of normative considerations about which species hold intrinsic value essentially hinges on where we place the moral dividing line. But where should that line be drawn? Within an anthropocentric framework, this line is typically placed between humans on one side and everything else – animals, plants, and inanimate objects – on the other. For sure, humans are not always treated equally under certain systems, but they are generally accorded at least some moral value. However, the common division between humans and all the rest appears rather arbitrary when we consider that animals, like humans, possess a brain and nervous system, and often can experience positive and negative welfare. Biologically, animals are much closer to humans than they are to plants, let alone inanimate objects.

In this book, I extend moral consideration to animals, but not to plants. I will justify this choice. Animals, including humans, have complex organ systems such as nervous, circulatory, respiratory, and digestive systems. These systems perform similar functions across various animal species. In contrast, plants have fundamentally different structures and systems, such as xylem and phloem for nutrient and water transport, and lack complex organs like brains or hearts. Cellular complexity is also very different between animals and plants. Plants undergo different biological processes such as photosynthesis, different modes of reproduction (like flowering and seed production), and growth patterns (like phototropism and gravitropism). Plants and animals have evolved separately for at least 600 million years. The bottom line is that, given the relative biological continuities between humans and animals, it appears difficult to justify a moral discontinuity that assigns moral value solely to humans and puts all other animals and plants in the same category located outside the moral community.

The anthropocentric position adopted in economics can be viewed as a corner moral case. There is little doubt that this position is morally dubious. For instance, Fleurbaey and Leppanen (Reference Fleurbaey and Leppanen2021, page 258) forcefully argue that “anthropocentrism in normative concepts is suspect, unfounded, ominously similar to the old religious and racist doctrines that gave the White Christian Man the right to own the Earth, and apparently too weak as a normative compass to fight pervasive destruction in the age of mass extinction.” Some critics would characterize the anthropocentric position as “speciesist” (Singer Reference Singer1975), which refers to the unjustified and biased treatment of beings based on their species membership (or more precisely to “anthropocentric speciesism”; see Horta Reference Horta2010).

Now, this raises another question: Why have economists consistently ignored animal welfare? This is a difficult question, and I am not aware of any research on this. I conjecture that the main explanation is a simple one: Like most people, economists are “speciesist.” By this, I mean our instinctive moral intuitions that consistently prioritize our own species. As advanced by Jaquet (Reference Jaquet2021), the notion that only humans hold moral importance may be primarily influenced by “tribalism,” namely our inclination to prioritize ingroup members over outgroup members. In essence, I am saying that economists may naturally lean toward human-centric perspectives simply because economists are humans.

But there is an additional problem. Economists are not only anthropocentric, but they also seldom acknowledge the existence of this anthropocentric approach as an important hypothesis, let alone engage in discussions justifying it as a reasonable standpoint. It seems that economists are not even aware of this bias. As an example, consider the working paper of my esteemed colleague at Toulouse School of Economics Jean Tirole titled “Assumptions in economics” (Tirole Reference Tirole2019). In this paper, anthropocentrism is not even mentioned among the assumptions. Jean Tirole, the 2014 Nobel laureate in economics, is one of the most prominent and respected economists worldwide. He has produced various seminal papers in many fields of economics and has contributed several major textbooks. His capacity to contemplate crucial aspects of our discipline is beyond dispute. Nonetheless, I regard this omission as rather ordinary, as it merely mirrors the prevailing conventional mindset within the field of economics. It exemplifies the deeply ingrained nature of the speciesist bias, highlighting how it tends to persist in the background, largely unchallenged and not even mentioned in our discipline. When a problem is not acknowledged, it is difficult to go forward and to change the status quo.

This omission is particularly disturbing in the works in economics that attempt to reflect on equity issues. Let me take a couple of examples to illustrate. In the domain of welfare economics, a pivotal concept is the “veil of ignorance” proposed by John Rawls and John Harsanyi. This concept is built upon a thought experiment wherein individuals tasked with making political decisions must imagine themselves devoid of knowledge about their own identity. This exercise is designed to help them transcend their self-serving biases and, in turn, foster moral impartiality. Within this framework, various examples are provided in the economics literature, where people are asked to envision themselves without knowledge of their gender, ethnic background, economic status, class, abilities, or talents. They are sometimes encouraged to consider extreme scenarios where they could be slaves, physically handicapped, mentally challenged, and more. Yet, strikingly, I have never seen any example prompted to consider themselves as animals. Thus, while this thought experiment induced by the veil of ignorance effectively surmounts numerous mental barriers, it notably falls short when it comes to overcoming species-based biases. The veil of ignorance concept, as it is usually presented in economics, thus exhibits anthropocentric speciesism. In animal ethics, Rowlands (Reference Rowlands1997) notably advocates for the moral consideration of animals within a contractarian framework by utilizing the concept of the veil of ignorance.

A related concept is that of Adam Smith’s “impartial spectator.” The impartial spectator represents an imagined observer or judge who is able to view situations from a neutral and unbiased perspective. Bowles and Halliday (Reference Bowles and Halliday2022, page 255) refer to the concept repeatedly in their excellent textbook to introduce the social welfare function used in economic models. They give the example of fishermen imposing externalities on each other, and emphasize that the solution is given by the impartial spectator wishing “to determine fishing time and distribute fish so as to maximize a social welfare function.” The point here is the same as earlier. The impartial spectator is not really impartial but rather speciesist, only considering the welfare of fishermen and ignoring that of fish. Interestingly, Bowles and Halliday mention animals in several places in the book, emphasizing for instance that “our physical capacities are hardly remarkable compared to other animals” (page 19). The authors even correct Adam Smith who suggested that only humans can exchange goods, emphasizing that “species of fish exchange services in what are termed ‘biological markets’” (page 344). Still, the normative approach in their book inevitably remains anthropocentric.

As a final example, consider Tony Atkinson (Reference Atkinson2015)’s classic book “Inequality.” This book, cited thousands of times on GoogleScholar, and authored by a scholar who has significantly shaped the field of economic analysis of inequality for the past half century, is undoubtedly a reference on the topic. As usual however, the book is all about inequality among humans. Well, when introducing the topic of income distribution, the author writes (page 37): “Barbara Wootton, an English economist and social campaigner, wrote that one of the incidents that led her to write The Social Foundations of Wage Policy was the discovery that the elephant giving rides at Whipsnade Zoo earned the same amount as she did as a senior university teacher.” Although Atkinson recognizes that he has wondered about the relevance of the comparison, I find it interesting that he nevertheless introduces the topic using this anecdote. This is interesting because inequality is obviously not solely confined to income matters here; it also revolves around the treatment of a sentient being as a slave (and who does not actually “earn” the money). This highlights the often unnoticed or seemingly inconsequential treatment of animals in our world, a phenomenon that may elude even those with high expertise in matters of fairness and ethics.

In my paper with Alexis Carlier (Carlier and Treich Reference Carlier and Treich2020, page 2), we start with the following classical storyline of the invasion of Earth by a superior species.

Imagine that a super-intelligent species invades Earth. The superior intelligence of these aliens allows them to take over political power. Current living humans cannot make sense of their technology, knowledge, art or culture, nor can they comprehend their moral rules and legal obligations. Alien society is wealthy, egalitarian, and to a large extent much better than existing human societies. Some aliens are economists who study how to allocate resources and design incentives. In particular, welfare economists have designed and applied sophisticated fairness concepts, but these concepts only concern aliens, not humans. Alien environmental economists study how to preserve the environment and humans and (nonhuman) animals from extinction, and their studies thus contribute to maintaining biodiversity on Earth. Aliens only police their society. If animals commit violence towards humans in the natural environment, aliens do not interfere. Aliens like to eat humans but they care about human welfare to some extent. For instance, while most humans raised for food live inside big production factories, some are free-range, which is better for their welfare but increases the price of human meat.

The point with our story is simple. It is to propose a reversal of perspective. This is a standard technique used in science fiction books or movies (e.g., The Planet of the Apes). Our objective is to stimulate a reflection on our anthropocentric speciesism, and in particular about the induced research bias in economics. On rare occasions however, there is an attempt to justify the anthropocentric approach. Most often, human exceptionalism is the only justification. However, as I will argue more in detail later on, this justification is problematic. Even if we were to acknowledge our exceptional status, as I have already said, there exist biological continuities between humans and animals that do not warrant a “moral discontinuity,” conferring exclusive moral value solely upon humans. Humans may count more than other animals, even much more; but they cannot count infinitely more.

Consider for instance the recent Review by Partha Dasgupta on the economics of biodiversity (Dasgupta Reference Dasgupta2021). Interestingly, the Review specifically defends its anthropocentric take. However, as I argue elsewhere (Treich Reference Treich2022), the defense is problematic. For instance, the Review says (page 49):

…there are nevertheless good reasons for concentrating on what one may call the instrumental value of biodiversity. One reason is that there are innumerable systems of thought that go beyond an anthropocentric perspective. Many people argue that life itself has intrinsic value, never mind that only a few among the 8 to 20 million species (of eukaryotes) on Earth are known to feel, never mind to have self-awareness. There are also many systems of belief – alas, all too readily overridden by cosmopolitan society – in which objects that to the cosmopolitan are inanimate, are sacred. They may house life, but they are not life; nevertheless, they are sacred. Uluru in Australia is a famous example. It is sacred to the Pitjantjatjara, the Aboriginal people of the area surrounding it. And there is the river Ganges, sacred to Hindus (Box 2.8). But the narratives underlying their sacredness differ.

I find several issues with this defense. First, it is acknowledged that there are “innumerable systems of thought” or “many systems of belief,” implying the existence of a multitude of worldviews. I concur with that. However, this does not inherently justify dismissing all alternative perspectives and exclusively favoring the anthropocentric view. Why not also consider certain nonanthropocentric viewpoints that may hold particular relevance? Second, the argument that only a few species “are known to feel” or “have self-awareness” is turned on its head here. These “few” species include at least mammals, birds, and fish (more on this later). This concerns a large range of species and, in turn, billions and billions of animals. Third, as I have argued before, putting animals, plants, and inanimate objects (such as the stone of Uluru or the river of the Ganges) in the same category is problematic. Only animals have, like us, a brain and a nervous system. Finally, this emphasis on what is “sacred” or “sacredness” as a possible alternative to anthropocentrism is in fact symptomatic of an anthropocentric view of the world (since people decide what is sacred); this actually illustrates the underlying resistance to depart from this view. Again, this emphasizes that even our leading scholars in (environmental) economics struggle to think outside of anthropocentrism.

There might of course exist many other factors that explain anthropocentrism in economics and beyond. So far, I have discussed the speciesist bias. Another important factor is politics for instance. The influence of political forces driven by human concerns skews our research agenda and research outcomes, perpetuating a human-centered approach. I have heard so many times that animals cannot be a research priority given all the problems humans face in the world. Essentially, it is all about pushing back that research agenda to a time that will never come. This political influence seems likely in the domains of agricultural and resource economics where limited funds have been allocated historically to the study of the welfare of farmed animals per se compared to other aspects such as animal productivity, animal health, or even the perception of animal welfare by consumers and farmers. As a researcher working for the French National Research Institute on Agriculture, Food and Environment, I know quite well from my personal experience that the research in this area is not fully independent from agricultural politics.

As another factor explaining anthropocentrism, there is the difficulty of the research effort. I quite like the following post by Dani Rodrik in September 2023: “the Economics profession under-invests in imperfectly identified analyses of big/important/relevant questions relative to well-identified but comparatively uninteresting questions.” Indeed, my impression is that the economics profession tends to allocate few resources toward exploring “imperfectly identified” analyses. I believe that complexity aversion may play a significant role here. It is very complex to study the well-being of other species, and to integrate this well-being into economic analyses. There is in particular a persistent belief that animal mental states are inscrutable, akin to a black box impervious to scientific inquiry, or inconsequential in explaining behavior. The research topic is not even well defined. It is not clear a priori how the problem of animal welfare can be approached from an economic perspective, and what it can give in terms of interesting economic insights.

1.3 Direct versus Indirect Approach

Let me go back to the initial question about the importance of the topic of animal welfare. There are essentially two reasons why animal welfare matters: for the people who care about animals, and for the animals themselves. It turns out that these two reasons are conceptually very different, and necessitate different approaches. Moreover, there is a pedagogical advantage in studying them separately, as it helps to avoid conflating different aspects of the issue. Since this distinction drives the whole organization of the book and the methods used, it is important to explain it in detail.

Part II focuses on the direct approach, meaning that this is the “for the animals themselves” part, while Part III focuses on the indirect approach, meaning that this is the “for the people who care about animals” part. These parts are largely independent and can be read separately or even in reverse order. Actually, since Part III uses a more conventional anthropocentric perspective, it might be considered a more accessible starting point for some readers, in particular economists. I chose to start with the nonanthropocentric part since this follows a long philosophical tradition. Also, this perspective represents a significant methodological advancement in economics, and is one of the key novelties of this book, perhaps deserving primacy.

Conceptually, this distinction between the direct and indirect approaches is related to debates on future generations, particularly within the climate discounting literature (Gollier Reference Gollier2012, Millner and Heal Reference Millner and Heal2023). The direct, or social discounting approach, argues that we should discount the future based on the normative belief that the welfare of future generations should be directly weighed. This approach was famously propounded by Ramsey (Reference Ramsey1928). It assumes that future generations have an intrinsic moral worth. In contrast, the indirect approach suggests that the welfare of future generations is considered only insofar as it affects the welfare of current generations, typically through parental altruism. Hence, this provides two conceptually different reasons for accounting for future generations, one based on general normative principles, the other on humans’ preferences. This is akin to the direct and indirect approach adopted here. As an example of well-known investigation, Farhi and Werning (Reference Farhi and Werning2007) contrast and explore both approaches in their study of intergenerational insurance and savings problems.

The distinction between the direct and indirect approaches is not entirely new in policy evaluation works. For instance, Sunstein (Reference Sunstein2024) argues that regulators should account for the value of animals, and interestingly, he draws a parallel between the challenges of valuing animals and those of valuing children. Specifically, he highlights that while one could use the parents’ WTP for their child as an indirect valuation tool, it may also be important to consider the child’s own welfare. We thus retrieve here the direct and indirect approaches. Sunstein further notes an additional complication: children, like animals, do not possess financial resources, which makes it difficult to apply the direct approach using traditional WTP methods.

Part II proceeds as follows. First, I explain why I favor sentientism as an alternative to anthropocentrism. Perhaps, the reader has already encountered the terms “sentientism,” “sentience,” or “sentient.” In short, sentientism is the moral consideration of all (and only) sentient species, namely those species who can “feel.” I then discuss the attempts for estimating welfare for sentient species, followed by the fundamental difficulty of comparing these utilities across different species. Undoubtedly, this is a very challenging objective. I then study how to aggregate these scores through a multispecies social welfare function. Finally, I will be in a position to present some theoretical and empirical nonanthropocentric economic approaches, and discuss issues regarding the ethics of animal populations. It is worth noting here that my normative assumptions can also be approached in a more descriptive manner. Indeed, the formal model includes the anthropocentric approach as a special case, allowing me to systematically compare both anthropocentric and nonanthropocentric outcomes.

To repeat, the key point is that the direct approach acknowledges the intrinsic value of animal welfare. This aligns with the philosophical tradition. This approach entails the direct inclusion of animals in the social welfare function. Under this approach, animals are regarded as individuals, and they have an intrinsic value. The impact of human actions on animals can then be perceived as an “externality,” where an externality refers to a cost or benefit imposed on a third party who did not consent to it. Implicitly, economists view externalities as effects on individuals who are worthy of moral consideration. Hence, if animals are worthy of moral consideration, actions impacting their welfare can be seen as externalities in the same way.

However, this direct nonanthropocentric approach presents several conceptual challenges, with a major issue being the assessment of welfare. The conventional approach, based on humans’ WTP, is inherently anthropocentric; it assumes that human choices can be used to estimate preferences, making it unsuitable for assessing the intrinsic value of animals. Moreover, using animals’ WTP presents significant complexity: Animals do not have income, and using other goods like food or energy as metrics introduces additional challenges since animals do not engage in market transactions of these goods. Thus, the standard economic methods for welfare assessment must be adapted. At its core, the direct approach grapples with the complex issue of interspecies comparison. While comparing human welfare among humans is already very difficult, attempting to compare the welfare of humans and animals or even among different animal species presents immense challenges.

Besides, if one views impacts on animals as externalities, and if policies affect their number, we run into population ethics issues. When actions or policies affect the number of morally relevant individuals, it is not even clear what efficiency means. How can we normatively compare the welfare of 100 individuals with a good quality of life to that of 50 individuals with a better quality of life? In economics, we usually avoid such comparisons as we typically compare situations with the same population size and even the same individuals. In the analysis of the canonical model and subsequent chapters, I will explore how to adapt and reinterpret conventional models of externalities, as well as policy interventions such as Pigouvian taxation, when the externalities involve animals, and thus when the policy issue raises a population ethics problem.

At this juncture, it is important to emphasize that the book aligns with the utilitarian tradition, grounding itself in a consequentialist and welfarist perspective. In short, I assume that only the impacts on the well-being of the individuals involved hold significance. This reflects the normative view that nothing can be good for society unless the members of the moral community (being humans or animals) are themselves benefitting from it. These impacts are then typically aggregated through a sum of utilities of these individuals. I will often coin this consequentialist/welfarist/utilitarian approach the “utilitarian approach.” Utilitarianism has been a cornerstone of ethical discourse for over two centuries, originating from Bentham’s seminal works. While many contemporary moral philosophers may diverge from utilitarianism, utilitarianism continues to wield a leading influence beyond philosophy, notably in fields such as welfare economics and legal scholarship (Adler Reference Adler2019). Interestingly, early utilitarians also made central contributions in animal ethics, as we will see. See Sebo (Reference Sebo2022) for a concise discussion and comparison of consequentialist and non-consequentialist approaches in animal ethics and Varner (Reference Varner2012) for an ethics that combines the two.

Let me stress now an important problem with the direct approach. I would call this problem the “fundamental political objection.” This objection can be presented as follows. Given that humans hold the predominant political power on Earth, it becomes unclear how animals can have practical significance based on this nonanthropocentric approach. The point is that, in terms of immediate policy or political implications, the direct approach seems to lack substantial traction. This is exemplified in our legal system where animals have traditionally been characterized as “things,” and thus are subject to the legal regime of goods, not that of “persons.” The legal approach remains inevitably anthropocentric, favoring the interests of humans and where animals only have an instrumental value.

To illustrate the political objection, consider the following argument by the famous legal scholar and judge Richard Posner (Reference Posner, Sunstein and Nussbaum2004) (cited in Stawasz Reference Stawasz2024):

[T]o the extent that courts are outside the normal political processes, [an animal-rights] approach is deeply undemocratic. There are more animals in the United States than people; if the animals are given capacious rights by judges who do not conceive themselves to be representatives of the people – indeed, who use a methodology that owes nothing to popular opinion or democratic preference – the de facto weight of the animal population in the society’s political choices will approach or even exceed that of the human population. Judges will become the virtual representatives of the animals, casting in effect millions of votes to override the democratic choices of the human population.

In a nutshell, Posner contends that it is “undemocratic” to grant rights to animals. Of course, one may argue that this rests on a speciesist definition of a democracy. But, in any case, this fundamental political objection may be viewed as a serious drawback of the direct approach. One may wonder: What is the point then of discussing an approach that can hardly be implemented for political reasons? This is a very difficult question to answer. Perhaps, one may think that the direct approach serves as a thought experiment that describes what we could or even should do morally. This thought experiment might be viewed as interesting in itself. It may also spark stimulating conceptual considerations. Moreover, one cannot completely exclude that these considerations might perhaps gradually permeate society and potentially have some impacts. After all, the moral beliefs of people may matter in our society. Note that this also offers connections to other political debates surrounding issues such as the interests of future generations or the historical debates on slavery.

This being said, the political objection provides a justification for developing an alternative approach, that is, the indirect approach. This alternative approach assumes that animals do not have intrinsic value but they matter insofar as they matter for humans. Under this approach, animals are indirectly incorporated into the social welfare function through human preferences, such as altruistic preferences toward animals. While the anthropocentric approach is problematic from a moral perspective, it corresponds to the existing economic approach to animal welfare. It is of course much more realistic politically, and it can hardly be deemed as undemocratic. Although this indirect approach is more conventional than the direct approach, it is also full of challenges and thus very stimulating, as we will see.

The existing literature in economics using this indirect approach is mostly based on studies about the WTP for animal welfare. These studies reveal that many people are willing to pay a significant amount for animal welfare, and that their income, age, and access to information are important factors that explain the level of WTP. However, there is still much to learn about how humans exactly care about animals. WTP studies are useful, but only offer a partial and limited view about humans’ proanimal concerns, as they focus on specific decision-making contexts, and focus on pricing. It is thus essential to conduct more research to understand how proanimal concerns manifest in people and society. Moreover, as the indirect approach is rooted in the notion that humans care about animals, the underlying theme is fundamentally behavioral. A purely “homo economicus” approach, which assumes purely self-interested decision-making, would be inadequate in this context. It simply fails to account for the interests of animals in human decisions.

This indirect approach is primarily motivated by a puzzle related to the apparent “gap” between public opinion and market demand when it comes to animal welfare. While opinion polls and surveys often indicate that citizens care about animals, market data suggest that concerns for animal welfare are very limited globally. As a case in point, the expansion of intensive farming units in modern animal agriculture indicates that consumers seem to care little about animals. In a 2008 referendum, about two-thirds of Californians voted in favor of banning battery cages, despite the limited demand for cage-free eggs in the state, which held only about 10 percent of the market share at that time (Norwood and Lusk Reference Norwood and Lusk2011). To paraphrase Norwood and Lusk, this “California egg paradox” raises the question of why people do not seem to shop like they vote. They call it the vote–buy gap. Further research is thus needed to better understand the psychological, social, political, and in particular the economic factors that contribute to the gap between public opinion and market demand for animal welfare, and to develop strategies to bridge this gap and improve animal welfare.

To conclude this section, I would like to briefly address a potential objection to the differentiation between the direct and indirect approaches. This objection posits that attributing an intrinsic value to animal welfare is essentially another manifestation of human preference, albeit of a different nature. In a broader sense, this objection questions the feasibility of a nonanthropocentric evaluation, given that it is conducted by humans, and in turn questions the separability of the direct and indirect approaches. Some may argue for instance that, since moral reasoning is a distinctive capability of humans, there would be no moral suffering if there were no humans.

I disagree with this objection, although I admit that this is a tricky issue. My view is the following. The direct nonanthropocentric approach builds on a normative foundation that defines what should be the social objective. This normative foundation depends on general normative principles, but does not depend a priori on human preferences toward animals. It is, however, important to acknowledge that only humans (philosophers, social choice experts, mathematicians, etc.) reflect on those normative principles and ultimately conduct this evaluation. Therefore, it is possible, and even unavoidable I would say, that some degree of “human bias” is present in the process. But, again, this is not really about human preferences toward animals, and this does not equate to an inherently anthropocentric bias. While humans do the evaluation, its purpose is not (at least in principle) to do it for human benefit. In sum, the evaluation is inevitably made by humans, but not “for” humans. It thus remains nonanthropocentric according to the very definition of the term.

1.4 Putting the Book into Perspective

Existing discussions on animal welfare often highlight moral, cultural, or ideological perspectives. However, economics, which plays a vital role in shaping human behavior and societal structures, is often neglected in these discussions. Occasionally, when economics is considered in some discussions, it is done so as a sweeping critique of capitalism and of the market economy. Yet such critiques are often broad and quite imprecise, and thus not very constructive. What, specifically, is the problem with capitalism in relation to animal welfare? Are there viable alternative systems, and how would they function in practice? Is there evidence that nonmarket economies have treated animals better?

Let me be clear from the outset: This book is not intended as a direct critique of the capitalist system. There are several reasons for this. First, the relationship between capitalism and animal welfare is a fascinating but highly complex topic, perhaps too ambitious to tackle comprehensively within the scope of a book this size. For insightful perspectives on this issue, see McMullen (Reference McMullen2016) and Nibert (Reference Nibert2017). Second, a central message of this book is that the root problem is not really capitalism itself, but speciesism. Capitalism, if one views it as a system based on private ownership and individual freedom, would take on a very different form in a non-speciesist society. In such a society, animals would be recognized as individuals, and thus neither be treated as property nor deprived of their freedom. As a result, most issues explored in this book would simply not exist even in such a capitalist system.

The book’s primary focus is on examining the potential problems and solutions to issues regarding animal welfare that can arise within the current dominant economic system, namely a market economy. In line with conventional economic analysis, the approach here largely centers on identifying and addressing “market failures,” with a particular emphasis on externalities and public good problems affecting animals. Additionally, the book concludes with discussions on broader topics, such as the morality of markets and political aspects, offering further insights directly tied to the issue of the impact of the economic and political system on animal welfare in general.

More precisely, the canonical model presented in this book pictures a market economy with human consumers and producers of animal products. In this model, animals are third parties affected by market transactions. In other words, humans generate externalities on animals. A precursor to this model is that of Blackorby and Donaldson (Reference Blackorby and Donaldson1992). In that outstanding paper, a social planner chooses the optimal level of meat consumption given that both humans and animals’ welfare matter, and this level is compared to the equilibrium outcome. Following conventional economic thinking in the management of externalities, I show that it is possible to introduce a levy on animal products so that humans internalize the externalities of their actions on animals (Espinosa and Treich Reference Espinosa and Treich2024). This is the standard Pigouvian correction to externalities. Hence, the approach illustrates how to adjust the functioning of the existing economic system to better take into account animals.

Although conventional, this approach requires dealing with specific difficulties related to the fact that the affected parties are animals. One key difficulty (already mentioned earlier) is the following: Altering the price of animal products directly impacts the number of animals consumed and produced, consequently influencing the overall animal population. This poses a well known ethical dilemma because one must compare different population sizes, and in particular one must compare life to nonexistence. The concept of “life worth living” becomes central in this context, and a dedicated chapter on population ethics explores various normative approaches to address this complex issue. Different approaches are presented to tackle this challenge and determine how to evaluate and compare animal populations of different sizes.

Another specific difficulty, also mentioned earlier, concerns the calculation of the externality on animals. This calculation is needed to calibrate the appropriate levy to apply to meat consumption to account for the externalities of meat consumption on animals. How to translate animal welfare into the unit of the tax, namely monetary units? Practically, the evaluation of the externality requires the assessment of animal well-being. This assessment cannot in principle resort to the observation of market prices, as they are controlled by humans. Nor can it resort to humans’ WTP approach as I have already stated. Therefore, the difficulty of measuring animal well-being and comparing it to human well-being must be confronted.

I present in this book a step-by-step method to assess animal welfare (Budolfson and Spears Reference Budolfson, Spears and Portmore2020, Espinosa Reference Espinosa2024, Espinosa and Treich Reference Espinosa and Treich2024). This can be viewed as an introduction to the topic, since the development of methods to assess animal welfare constitutes a research program on its own, and we are just at the beginning of this program. The proposed approach’s advantage is its breakdown of this very complex problem into several simpler components. One component involves calculating an “animal welfare score,” which can be understood as a utility level at a specific point in time and aggregated to represent lifetime utility. Another component focuses on comparing this utility level across different species, referred to as “utility potential.” Additionally, a philosophical foundation is provided to represent and aggregate the individual welfare of different species within the social objective, or social welfare function. Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, the book can then formulate specific policy-making insights using a social objective that captures the quantified interests of both humans and animals in society.

A central theme explored in this book revolves around the distinction between quantity and quality. By “quantity,” I refer to the quantity of animal lives, that is the number of animals (and possibly the duration of their lives). By “quality,” I refer to the quality of animal lives, namely their level of welfare. Various human actions such as food choices, animal testing, or biodiversity preservation can impact either the quantity or the quality of animal lives, and most often both. The book extensively explains why unregulated markets often fail to achieve socially optimal outcomes in terms of both quantity and quality, making regulation essential. It turns out that it is fruitful to separate quantity and quality here, as routinely done in other domains in economics but rarely explicitly done in the works on animal welfare in other disciplines.

It is interesting to examine the literature on animal welfare in food and agriculture sciences versus that in environmental sciences with the quantity/quality distinction in mind. Indeed, the food and agricultural literature on animal welfare is predominantly preoccupied with issues regarding the quality of animal lives, namely the welfare of farmed animals in a specific husbandry system. In contrast, environmental sciences are primarily focused on quantity concerns, such as the preservation of some wild animal populations rather than their welfare levels.

Currently, animal welfare regulations in most countries primarily rely on legislative tools such as norms and guidelines. In the food industry or in medical research, existing regulations focus on the quality aspect alone and are designed to establish a practical and economically manageable minimum level of animal welfare. The research presented in this book is able to compute precisely the tradeoff between the economic cost for humans and the benefit for animals of a regulation improving quality. However, one important message of the book is that the quantity of animal lives must also be regulated, typically by choosing the number of animals produced that is socially optimal. Hence, the book also emphasizes the significance of incorporating instruments that address quantity, such as meat taxation, as part of a comprehensive animal welfare regulation.

Another central market failure in the context of animal welfare is the public good problem arising from the free-rider issue faced by consumers. Consumers may not properly consider that the impact of their proanimal actions also increases the welfare of other consumers who care about animals too, thus leading to underprovision of animal welfare by the market. While this is a recurring theme in economics, it may not have been adequately addressed in animal welfare regulation. Again, in the realm of food consumption, some commentators emphasize the importance of consumers’ freedom of choice, and advocate for increased transparency through information schemes, such as labels indicating animal welfare standards. However, it is essential to recognize that such information initiatives alone cannot effectively resolve the public good problem at hand. A fiscal instrument may seem appropriate in a first approximation to deal with this public good problem, following the longstanding literature on Pigouvian taxation.

The book also moves beyond standard market failures such as externalities and public goods as it also extensively discusses “behavioral failures.” In particular, it documents the various misperceptions or even misconceptions of humans regarding animals. For instance, people may underestimate animal suffering in industrial farming conditions, and overconsume meat as a result. I show then that animal welfare may then be viewed as a merit good, and that applying a levy on meat may also properly restore optimality under simple conditions.

I extensively discuss the literature on the psychological conflict that arises in individuals who consume meat while also being aware of the moral concerns related to animal welfare. This conflict is coined the “meat paradox.” I present an economic approach to this paradox highlighting the effectiveness of meat taxation as a means to make consumers more realistic about the impact of their consumption on animals, which, in turn, reinforces the usual economic impact of taxation. Additionally, the book explains for instance that the commodification of animals in various industries can lead to an erosion of morality. By examining these diverse behavioral failures or problems, the book aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issues involved in animal welfare within the context of a market economy. It also identifies gaps in current studies, and ideas for future research.

The book also discusses the links between proanimal and prosocial aspects. There is indeed a large literature in psychology and economics on prosociality that may be relevant. For instance, recent studies have identified an interesting pattern: “moral universalism.” This pattern characterizes the extent to which people account for the interests of strangers relative to those of ingroup members. Indeed, two clusters typically emerge: Some people support redistribution, health care, environmental protection, affirmative action, and foreign aid, while others support military spending, law enforcement, and border protection (Enke et al. Reference Enke, Rodríguez-Padilla and Zimmermann2023). Younger and poorer people, women and less religious people in almost all countries are more universalist in the sense that they more likely to belong to the former group (Cappelen et al. Reference Cappelen, Enke and Tungodden2024).

Although it remains an open question whether animals are part of this universalism pattern, it would not be a surprise. Studies in psychology have shown that individuals who tend to devalue other human groups (e.g., racism, sexism, homophobia) also tend to devalue animals (speciesism) (Caviola et al. Reference Caviola, Everett and Faber2019). Evidence suggests that animals are often viewed as the “outgroup,” potentially making them targets of prejudice and discrimination possibly stemming from ancestral tribalistic tendencies. On the other hand, empathy toward humans may extend to animals, suggesting potential parallels between proanimal and prosocial findings. Adding to this complexity is the challenge of gauging the well-being of animals from a human perspective. Assessing human welfare is often feasible, since we can rely on introspection to understand what brings happiness and suffering in others and can directly ask people how they feel. However, the issue becomes considerably more intricate when it comes to animals, particularly those who are distant from us in evolutionary terms. This can typically give rise to two opposite biases: anthropomorphism, attributing human characteristics to animals (akin to projection bias), and conversely anthropodenial, denying such traits to animals.

A word now on the method used in this book. Although most content is nontechnical, several chapters in this book employ mathematical models. In particular, I use a so-called canonical model and adapt it in several chapters to discuss various economic approaches to animal welfare. I acknowledge that this technicality may be perceived as a barrier to some readers. The main justification for using these models is the usual one: rigor and precision. Mathematics indeed permits us to explore rigorously the implications of a set of assumptions. It also permits the precise definition of certain concepts. Consider for instance the concept of antispeciesism. This concept is central in animal ethics and more generally in the literature on animal welfare, but the term is often used colloquially. In this book, I will formally characterize antispeciesism as a moral concept. This allows us to reduce the scope for misunderstanding, and to explore the implications of antispeciesism in a meaningful manner. This also, of course, makes it easier to see the limitation of that characterization, and perhaps make progress toward a better characterization. Additionally, the use of mathematics also permits the generation of quantitative estimates through the calibration or estimation of formal models. For instance, I leverage the theoretical model’s outcomes to compute the optimal levy in monetary terms that could be applied to meat consumption.

I want to add, however, that the mathematical language employed in this book is basic and consistent throughout, primarily focused on defining an objective to maximize, identifying optimal solutions, and conducting comparative statics analysis (i.e., exploring how the solutions vary with the model’s parameters). The computations are straightforward and usually necessitate only one or two lines of mathematical calculus. I overlook some mathematical difficulties that bring little to the depth of the analysis, such as the analysis of second order conditions or of corner solutions. Thus, the book does not contain many technicalities. Only a basic knowledge of mathematics is necessary, and readers can find the essential mathematical concepts in various basic microeconomics textbooks. Furthermore, I strive to provide intuitive explanations throughout the book, ensuring that the implications of the theory are understandable to a broad audience. In some chapters, I even separate the formal analysis from a qualitative discussion of the important aspects. On the other hand, readers who are mathematically inclined will find backup for the main text in the cited sources.

As a minor remark, I have chosen not to include footnotes in this book. It is a departure from my usual practice, and also from the usual practice of the profession. While footnotes are undoubtedly valuable, they can also be somewhat addictive. Once you start adding footnotes, there is often a temptation to include even more, whether it is for additional explanations, side remarks, or extra references. Personally, I find myself relying on footnotes quite heavily in my research papers. Therefore, the decision to ban footnotes serves as a commitment device to focus on essential content and avoid distractions and endless additions. This decision is costly but, hopefully, it will enhance the flow of the text and optimize readability. Let me also mention that I will frequently use verbatim citations, particularly in the literature survey sections (such as 2.4 and 2.5). Often, there is no need to rephrase something that has already been expressed with perfect clarity. Moreover, this practice allows me to give due credit to the original authors.

As I said earlier, the primary audience for this book is undoubtedly economists, or more broadly people interested in the research in economics. Indeed, one central objective of this book is to develop and accelerate the development of the research in economics on animals and their welfare. However, the content may surprise some of these readers, particularly agricultural economists, as it significantly diverges from the existing discussions on animal welfare in their field. Indeed, the book does not devote a lot of space discussing the production costs associated with animal welfare or consumers’ WTP for more animal-friendly products. Although these aspects are undeniably essential, they have already been explored in other works such as in the seminal book by Norwood and Lusk (Reference Norwood and Lusk2011). Moreover, these works largely rely on established and conventional economic approaches. They typically consider animal welfare as an “attribute” of a product and essentially study how this attribute affects demand and cost functions. Hence, I do not add much to this conventional approach in this book.