Impact statement

Zimbabwe has been a focus of global investment in depression treatment and mental health services scale-up. The study findings, consistent with findings from many other African settings, demonstrated that Zimbabwean primary care nurses do not recognize depression when nurse recognition is compared with results on screening tools administered by a researcher. Nurses, however, documented providing social support to some patients and treating others for psychotic disorders, illustrating that they are integrating mental healthcare into their practice. We found that compared to patients without depression, many of the patients with probable depression presented with medication non-adherence or non-specific chronic pain, symptoms that could prompt a nurse to consider depression. However, many nurse participants had not had formal training in primary care–based management of depression, and they did not consider depression to be a high priority, relative to the other common conditions that they saw in their practice. We also observed that the primary care clinics are busy and understaffed, potentially leaving little time for depression management. These results highlight that depression recognition may be a barrier to treatment in primary care and, in addition, identify potential barriers to recognition. They also, however, suggest that nurses are addressing more severe mental illness in primary care, a potential success of mental health scale-up efforts.

Introduction

Depression is common and often overlooked in primary healthcare (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Abas, Broadhead, Todd and Reeler2001; Menchetti et al., Reference Menchetti, Murri, Bertakis, Bortolotti and Berardi2009). Many people with depression present to primary care with other concerns (Kapfhammer, Reference Kapfhammer2006; Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Demissie, Birhane, Medhin, Bitew, Hailemariam, Minaye, Habtamu, Milkias, Petersen, Patel, Cleare, Mayston, Thornicroft, Alem, Hanlon and Prince2022), and particularly in contexts where depression is stigmatized, patients may not bring up concerns about depression to their provider. As a result, depression can go unrecognized (Habtamu et al., Reference Habtamu, Birhane, Demissie and Fekadu2023; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Gurung, Singh, Rai, Neupane, Turner, Platt, Sun, Gautam, Luitel and Jordans2025a), a barrier to treatment.

Several meta-analyses have examined depression recognition in primary care. One global meta-analysis found that among people with depression, based on a researcher-administered diagnostic test, 47.3% had their depression recognized (Egede, Reference Egede2007; Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Demissie, Birhane, Medhin, Bitew, Hailemariam, Minaye, Habtamu, Milkias, Petersen, Patel, Cleare, Mayston, Thornicroft, Alem, Hanlon and Prince2022; Habtamu et al., Reference Habtamu, Birhane, Demissie and Fekadu2023; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vaze and Rao2009). This study, however, included primarily studies from high-income countries and excluded nurses providing primary care. A meta-analysis in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) found that 3.9% (range: 0–28%) of people with depression were recognized in primary care (Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Demissie, Birhane, Medhin, Bitew, Hailemariam, Minaye, Habtamu, Milkias, Petersen, Patel, Cleare, Mayston, Thornicroft, Alem, Hanlon and Prince2022). Six of the nine studies in this systematic review included data from at least one African country (Ogunsemi et al., Reference Ogunsemi, Oluwole, Abasiubong, Erinfolami, Amoran, Ariba, Alebiosu and Olatawura2010; Kauye et al., Reference Kauye, Jenkins and Rahman2014; Udedi, Reference Udedi2014; Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Medhin, Selamu, Giorgis, Lund, Alem, Prince and Hanlon2017; Ayinde et al., Reference Ayinde, Oladeji, Abdulmalik, Jordan, Kola and Gureje2018; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Roberts, Medhin, Murhar, Samudre, Luitel, Selohilwe, Ssebunnya, Jordans, Bhana, Petersen, Kigozi, Nakku, Lund, Fekadu and Shidhaye2018); of those, two found that primary care providers identified 0% of those with depression (Kauye et al., Reference Kauye, Jenkins and Rahman2014; Udedi, Reference Udedi2014), and two found that they identified <2% (Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Medhin, Selamu, Giorgis, Lund, Alem, Prince and Hanlon2017; Ayinde et al., Reference Ayinde, Oladeji, Abdulmalik, Jordan, Kola and Gureje2018). One study, which focused on physicians at a teaching hospital, found that the doctors identified 24.1% of people with depression (Ogunsemi et al., Reference Ogunsemi, Oluwole, Abasiubong, Erinfolami, Amoran, Ariba, Alebiosu and Olatawura2010), though this is not a standard primary care setting in much of Africa. Several interventions have been tested and shown to increase depression detection in African primary care, including a digital application to support primary care providers to identify and manage depression in Nigeria (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Ojagbemi, Luitel, Bakolis, Bello, McCrone, Taylor Salisbury, Jordans, Votruba, Carswell, Green, Gkaintatzi, Lamichhane, Elugbadebo, Kola, Lempp, Chowdhary, Dua, Gureje and Thornicroft2025b), a 5-day provider training in Malawi (Kauye et al., Reference Kauye, Jenkins and Rahman2014), provider training and implementation of routine screening in Ethiopia (Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Milkias, Birhane, Tekola, Yared, Eshetu, Getahun, Lempp, Tylee, Belina, Medhin, Habtamu, Alem, Lund, Petersen, Thornicroft, Cleare, Mayston, Assefa, Demissie, Hanlon and Prince2025) and implementation of a broader collaborative care program that included depression screening in South Africa (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019). However, these practices are not routine in most LMIC primary care settings.

Over the past several decades, there has been a growing effort to improve treatment of people with depression in LMICs (Abas et al., Reference Abas, Mbengeranwa, Chagwedera, Maramba and Broadhead2003), with major investments from the World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health, n.d.), other international funders and national governments in depression treatment (Financing Mental Health, n.d.). Zimbabwe received international support to scale up the Friendship Bench, a lay health worker-delivered psychological therapy for depression and anxiety (Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Weiss, Verhey, Simms, Munjoma, Rusakaniko, Chingono, Munetsi, Bere, Manda, Abas and Araya2016). There have been several efforts, led by both international organizations and the Ministry of Health, to train primary healthcare workers on care of mental health conditions, including depression, using the Mental Health Gap Action Programme Intervention Guide (mhGAP-IG) (WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health, n.d.). mhGAP-IG, however, does not include screening or focus on case recognition; rather, it starts at the step of differential diagnosis, once a provider has a clinical suspicion (World Health Organization, 2016).

In light of the ongoing investment in depression treatment in Zimbabwe, the aim of this study was to determine the proportion of people with probable depression who were identified and offered treatment in primary care. We hypothesized that the proportion of people who were recognized by the nurse is lower than the proportion of people who screened positive for depression. In order to better describe the broader context of mental healthcare delivery, we reviewed clinical notes for any examples of mental health treatment (Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Gurung, Singh, Rai, Neupane, Turner, Platt, Sun, Gautam, Luitel and Jordans2025a). Understanding nurse practices in depression diagnosis and mental health treatment may inform ongoing efforts to implement mental health services within primary healthcare, both in Zimbabwe and in other LMICs.

Methods

We used a cross-sectional study design to compare primary care nurse recognition of depression with the results of depression screening administered by a trained research assistant, similar to the design of depression recognition studies in other LMICs (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vaze and Rao2009; Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Medhin, Selamu, Giorgis, Lund, Alem, Prince and Hanlon2017; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019; Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Mntambo, Bachmann, Bhana, Rao, Grant, Hughes, Simoni, Weiner, Gigaba, Luvuno and Petersen2020). This cross-sectional study is reported according to the STROBE Checklist (von Elm et al., Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2007).

Setting

In Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe (population 1.5 million), primary healthcare is provided by the City of Harare Health Department, delivered primarily by nurses and funded mainly through local taxes (City Of Harare | Council Health Facilities, n.d.; Abas et al., Reference Abas, Mbengeranwa, Chagwedera, Maramba and Broadhead2003). There are 41 public clinics: 29 small to medium clinics and 12 larger polyclinics (Shumba et al., Reference Shumba, Moyo and Ndemo2025), which provide a wider range of services, including maternity care, laboratory services and occasional physician-delivered services. Based on our team’s knowledge of the healthcare system, patients presenting for primary care pay $USD 5 per visit, and those presenting for HIV care receive it for free. The clinics stock a limited supply of certain medications that nurses can prescribe. If medications are unavailable, patients must purchase them from private pharmacies.

Based on records from the Zimbabwean Ministry of Health, selected nurses in all Harare polyclinics had been exposed to the mhGAP training in the past 10 years and were supposed to be implementing mental health treatment per the mhGAP guidelines. Additional mhGAP training was going on during the study period. mhGAP trainings are typically delivered as one-time 5- to 9-day trainings, and they have been delivered by the Zimbabwean Ministry of Health, Medecins Sans Frontieres, and the WHO over the past decade (2014 to present). Primary healthcare staff from each clinic were selected to attend, with the idea that if some staff in the clinic are trained, they will pass their knowledge to the other clinic staff. The default for nurses in Zimbabwe is to use clinical judgment, not a screening tool, to assess for depression, which is consistent with WHO mhGAP-IG recommendations.

All polyclinics were implementing the Friendship Bench, which is delivered by lay health workers on a bench outside clinic buildings. Nurses can refer patients to the Friendship Bench. The lay health workers also recruit patients from the community to the Friendship Bench, typically people who approach them or who are referred by other community members.

Depression in Zimbabwe commonly presents with somatic symptoms (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Abas, Broadhead, Todd and Reeler2001) and in Zimbabwe’s primary language, Shona, there is not a word for depression. The closest idiom is kufungisisa, meaning “thinking too much” (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997), but it does not capture the full range of depressive symptoms and can describe a normal, non-pathologic level of thinking.

Sample and data collection

Patient data were collected between November 2023 and July 2024, and nurse data were collected between May and July 2024. Data collection occurred at four primary care polyclinics in Harare.

Patient sample

All people waiting for a primary care visit, including those presenting for HIV care, were handed a numbered card, and numbers were randomly selected. Those holding cards with the selected numbers were invited to participate. Individuals were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, not presenting for care (e.g., accompanying a family member), under age 18 or too acutely ill to participate. After agreeing to participate in the study, participants proceeded to their visit with the nurse.

A priori power analyses were conducted to inform the targeted sample size. We assumed that 40% (n = 80) of participants would have probable depression (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997; Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Verhey, Gibson, Munetsi, Machando, Rusakaniko, Munjoma, Araya, Weiss and Abas2016b, Reference Chibanda, Cowan, Gibson, Weiss and Lund2016a; Haas et al., Reference Haas, Kunzekwenyika, Manzero, Hossmann, Limacher, van Dijk, Manhibi, von Groote, Hobbins, Verhey and Egger2023), with ≤20% (n ≤16) having depression recognized by their clinician (Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Medhin, Selamu, Giorgis, Lund, Alem, Prince and Hanlon2017; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019; Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Mntambo, Bachmann, Bhana, Rao, Grant, Hughes, Simoni, Weiner, Gigaba, Luvuno and Petersen2020). We found that a McNemar’s test would be well-powered (power ≥0.99) to detect a significantly lower rate of recognized depression compared to the rate of probable depression. Fifty patients were sampled from each of the four clinics.

Patient data collection

The Research Assistant (RA) gave the selected participants brief information about the study and screened them for eligibility. Prior to the nurse visit, participants were not informed that the study was about depression, so as not to bias them toward reporting depression to the nurse. As they would for any patient at the clinic, nurses documented their diagnosis and treatment plan in the patient’s medical record, a paper card that the patient brings to the clinic and carries home with them.

Following the nurse visit, patients reconvened with the RA, who went through the informed consent process, which included a detailed description of the study (though not its focus on depression), its risks and benefits and patient rights. If patients consented, the RA administered a demographic questionnaire and screened them for depression. The RA then reviewed the patient’s medical record for that day and recorded the notes word-for-word. The RA administered all questions verbally and recorded responses on a tablet. Patients were compensated $USD 10 in cash for participation.

Those who screened positive for moderate to severe depression or suicidality based on the PHQ-9 were referred to further care with a nurse-in-charge of the clinic.

Nurse sample

All nurses who saw any of the patient participants were invited to complete a survey (census sample). During interviews with patients, the RA noted down names and contact details for those nurses who attended to the patients participating in the study. Nurses who were not permanently assigned to a given clinic were excluded. Nurses were blinded to the study’s focus on depression so as not to bias them toward identifying depression.

Nurse data collection

After patient data collection at the clinic was complete, nurses were contacted and invited to participate in a survey. Nurses completed the survey directly on a tablet and were compensated $USD 10 to participate.

Survey measures

Patient survey measures

In addition to a sociodemographic questionnaire that included a measure of food security (Food Security in the U.S. - Survey Tools | Economic Research Service, 2025), the RA used two tools to screen for mental health conditions:

-

1) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): The PHQ-9 is a 9-item questionnaire that is used worldwide to screen for depression (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). It asks questions about depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks, and participants are asked to state how frequently they experience a symptom (not at all, several days, more than half the days, nearly every day). Scores range from 0 to 27. The PHQ-9 has been translated into Shona, Zimbabwe’s most common language, and validated against the Structured Clinical Interview of the DSM-IV diagnosis of depression with scores ≥11 indicating probable depression (sensitivity 85%, specificity 69%) (Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Verhey, Gibson, Munetsi, Machando, Rusakaniko, Munjoma, Araya, Weiss and Abas2016b). In many settings, a PHQ-9 score of ≥10 is considered moderate to severe depression (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Medhin, Selamu, Giorgis, Lund, Alem, Prince and Hanlon2017), and this score has been used in clinical trials in Zimbabwe (Abas et al., Reference Abas, Mangezi, Nyamayaro, Jopling, Bere, McKetchnie, Goldsmith, Fitch, Saruchera, Muronzie, Gudyanga, Barrett, Chibanda, Hakim, Safren and O’Cleirigh2022). For this study, a cutoff of 11 was used for primary analyses, and sensitivity analyses were performed using a cutoff of 10.

-

2) Shona Symptom Questionnaire (SSQ-14): The SSQ-14 is a 14-item questionnaire that was developed in Zimbabwe to screen for common mental disorders, primarily depression or anxiety (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997) and validated against the Structured Clinical Interview of the DSM-IV diagnoses of depression and/or generalized anxiety disorder (Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Verhey, Gibson, Munetsi, Machando, Rusakaniko, Munjoma, Araya, Weiss and Abas2016b). The SSQ-14 asks 14 binary questions about symptoms experienced in the past week and is scored 0–14. Scores of ≥9 are considered positive.

As these are screening tools, not diagnostic instruments, we refer to a positive result as “probable depression” (PHQ-9) or “probable depression and/or anxiety” (SSQ-14).

Patients were asked why they presented to see the nurse that day and what treatment they received. Patients were also asked if they had ever been diagnosed with or treated for depression in the past and, if so, what treatment they received, excluding any treatment received that day.

Nurse survey measures

To characterize nurses, we used a questionnaire to collect sociodemographic characteristics, rank and details on prior mental health training, including WHO mhGAP training. To better understand why nurses may or may not identify and treat depression, the survey asked questions about their knowledge of mental health and the relative priority they assigned to depression in their practice. To assess knowledge, we administered the mhGAP knowledge test, a 24-question multiple choice test that is included in the training manuals for the WHO mhGAP-IG (score 0–24) (mhGAP Training Manuals, 2017). To assess clinical priorities, nurses were asked sequential sets of questions about the importance of various common health conditions in their practice, including depression. The lists of conditions were based on the Zimbabwe National Health Strategy 2021–2025 (Ministry of Health and Child Care, 2020).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the patient and nurse samples and describe nurse scores on the mhGAP knowledge test. To display how nurses prioritized health conditions, the mean ranking was calculated for each medical condition and then the conditions were ordered by mean rank.

Medical record notes and patient-reported treatment plans were reviewed by three members of the research team and separately by a Zimbabwean nurse who was not part of the research team and was unaware of the research question. The notes were categorized as “depression recognized” or “depression not recognized,” and differences were reconciled through discussion.

Consistent with prior studies in LMICs (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019), we set very broad a priori criteria for identifying recognition of depression in the medical record: any mention of depression; referral to the mental health nurse or the Friendship Bench; prescription of an antidepressant; or mention of psychosocial problems, mental health issues, stress, grief or sadness. If a medication that can be used as an antidepressant was prescribed but another indication was noted, this was not considered recognition of depression (i.e., a tricyclic antidepressant that was noted to be used for sleep or pain).

The proportion of people with clinically recognized depression (medical record results) was compared with the proportion of people with probable depression based on the PHQ-9 using McNemar’s test. In a secondary analysis, probable depression or anxiety based on SSQ-14 scores was compared with medical record results using McNemar’s test.

We described symptoms and treatment plans from medical records for people with probable depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 11) and those with PHQ-9 scores of 0 to characterize how people with and without probable depression present to primary care.

Results

Patient sample

To reach a sample size of 200, 278 people were invited to participate. Fifty declined to participate, primarily because they were too busy, and 28 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Two participants were unable to complete the medical record review, as they were called back to see the nurse for additional follow-up care. They were included in the descriptive analyses and excluded from outcome analyses.

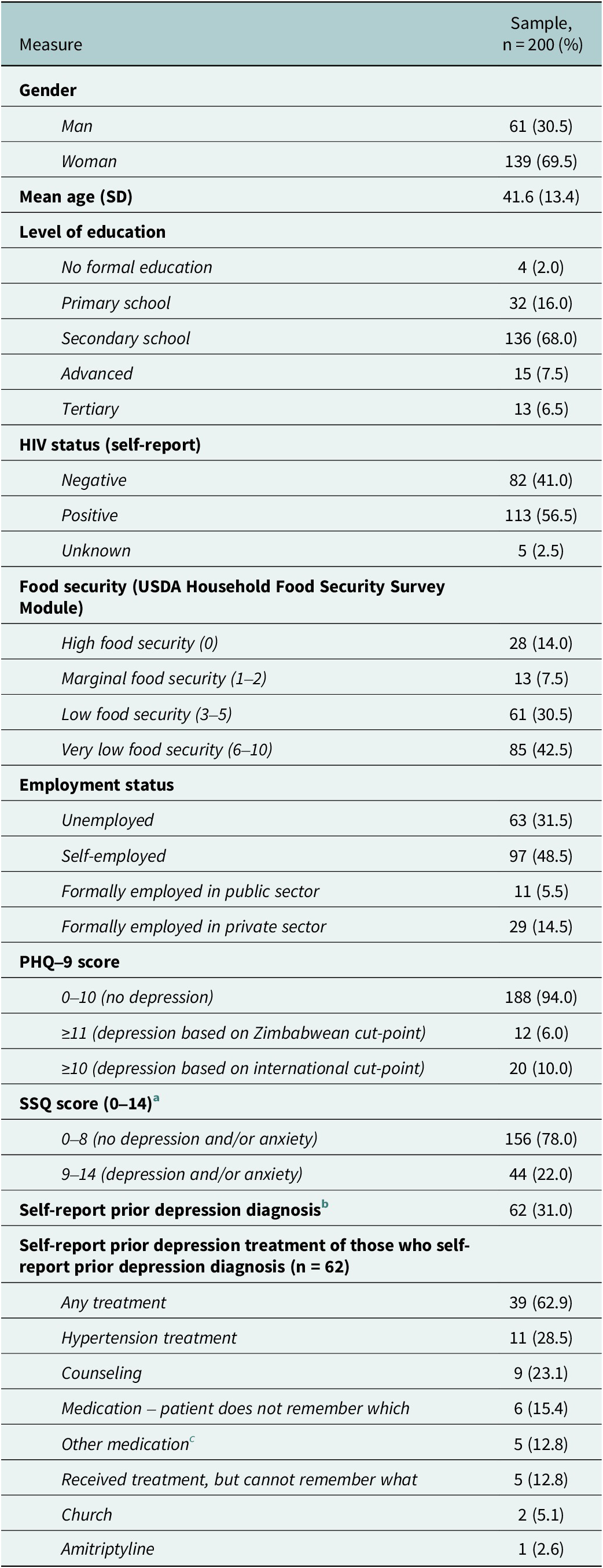

The patient sample was primarily female (69.5%). 56.5% self-reported living with HIV. 73% self-reported low to very low household food security. Patient sociodemographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the patient sample

a A single patient was missing a response to one of the 14 SSQ-14 questions, which was assumed to be negative; records were otherwise complete.

b Question was phrased “Have you ever been told that you have depression?”

c Other medications included pyridoxine, “sleeping tablets,” doxycycline, paracetamol and antihistamines.

Nurse identification of depression

Nurses identified two patients as having depression, one of whom was presenting for review of known depression. The other was presenting with joint pain, headache and insomnia and was given amitriptyline for 7 days, an NSAID, magnesium trisilicate and counseling; no specific diagnosis was written, but given that both counseling and amitriptyline were provided, depression was assumed, erring on the side of broader inclusion. Neither of these patients screened positive based on the SSQ-14 or PHQ-9.

Researcher identification of probable depression

Based on researcher-administered screening, 6% of the patient sample screened positive for probable depression using the PHQ-9 (cutoff of ≥11). If the international cutoff of ≥10 was used, 10% screened positive. Twenty-two percent screened positive for probable depression and/or anxiety using the SSQ-14.

Comparison of nurse and researcher identification

None of the patients who screened positive for depression based on the PHQ-9 with Zimbabwean cut-point or PHQ-9 with international cut-point, nor any of those who screened positive for depression and/or anxiety based on the SSQ-14 were identified by the nurse. The proportion of patients diagnosed with depression by the nurse was lower than the proportion of people who screened positive on the PHQ-9 with the Zimbabwean cut-point (score ≥11) (χ 2 = 7.14 p < 0.01), the PHQ-9 with the international cut-point (score ≥10) (χ 2 = 14.73, p < 0.01), or the SSQ-14 (χ 2 = 37.36, p < 0.01).

Notably, reviewing medical notes, researchers disagreed on how to classify nurse recognition of two cases of probable depression. In both, medical notes described specific social challenges (i.e., “has risks at home” or “came late because had a child in hospital and also lost her aunt”), but the diagnoses and treatment were unrelated to mental health (i.e., prescribed HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis or the nurse did antiretroviral therapy adherence counseling). Through discussion, the study team decided that none were consistent with a depression diagnosis, as this captured life events and indicated no action toward diagnosis or treatment. The team also discussed several cases in which nurses provided antiretroviral therapy adherence counseling and concluded that this did not qualify as a diagnosis of depression, as adherence counseling is a distinct service that Zimbabwean polyclinics provide.

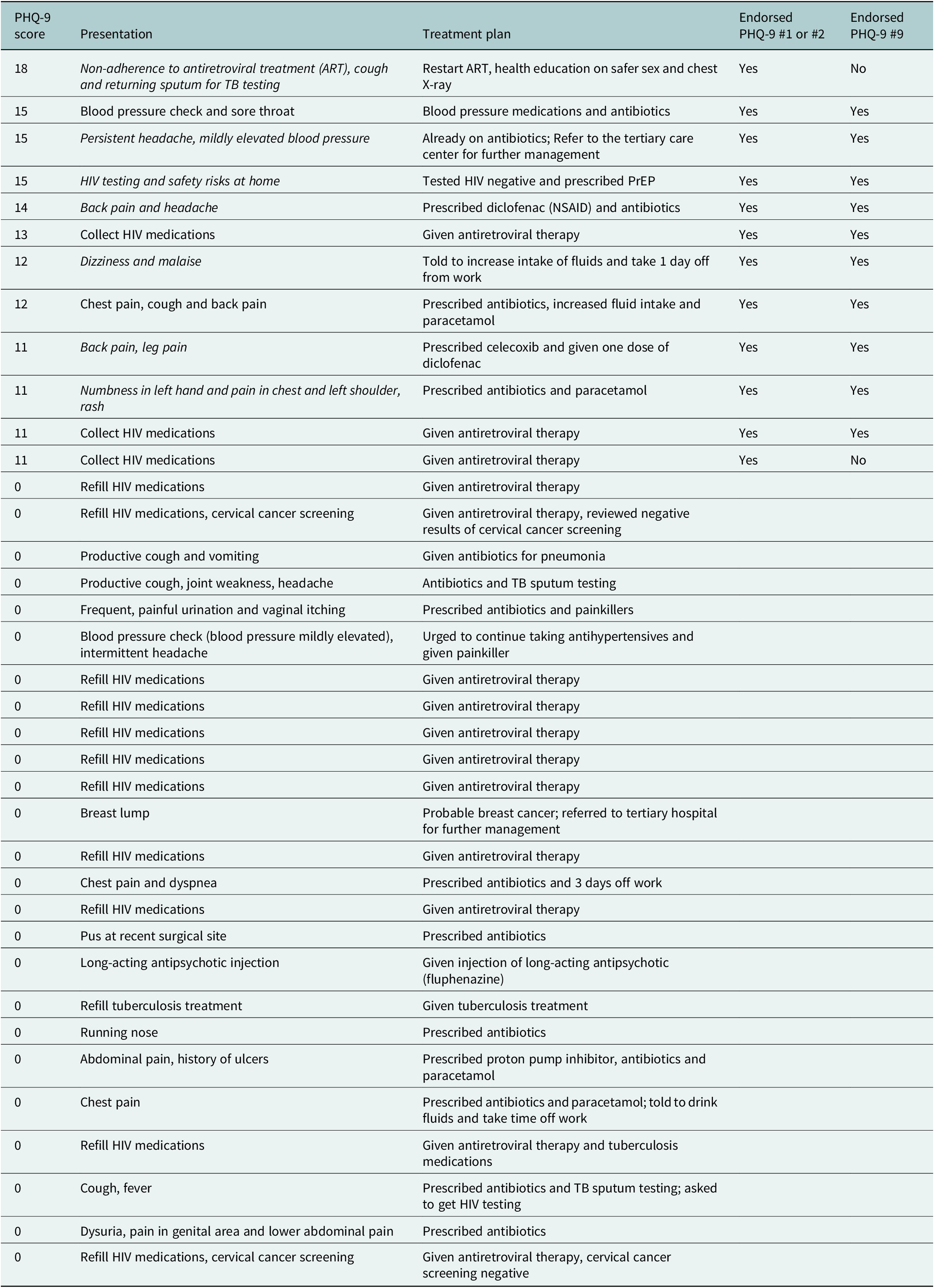

A summary of the reasons for presentation and treatment plan of patients with a PHQ-9 score ≥11 and those with a PHQ-9 score of 0 is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2. Reason for presentation and treatment plan for patients with low and high PHQ-9 scores. Italicized indicates a clinical presentation that could prompt clinical suspicion for depression

Patient-reported diagnosis and treatment

One patient with a PHQ-9 score of 10 (positive based on international cut-point) and SSQ-14 score of 9 (positive) reported that she was referred to counseling at a church and given sleeping pills. The nurse recorded that she was prescribed medication to prevent opportunistic infections and did not mention depression, counseling or sleeping pills. No other patients who screened positive based on either tool reported receiving a diagnosis of or treatment for depression that day.

Of the 62 people (31.0%) who reported that they had previously been diagnosed with depression, 62.9% reported that they previously received treatment, most commonly counseling (23.1%) or treatment with antihypertensive medications (28.5%).

Additional mental healthcare documented

Medical notes documented that the nurses provided some mental healthcare. As described above, one patient who screened negative on both PHQ-9 and SSQ-14 came for depression review, and the nurse refilled amitriptyline. Amitriptyline was also prescribed to several people for the management of chronic or neuropathic pain. Three people presented for review of a presumed psychotic disorder (notes did not specify a diagnosis). Two received a fluphenazine injection alone, and the other received refills of amitriptyline, haloperidol, chlorpromazine and benzhexol, and was given a fluphenazine injection. All screened negative on both the PHQ-9 and the SSQ-14.

Nurse sample

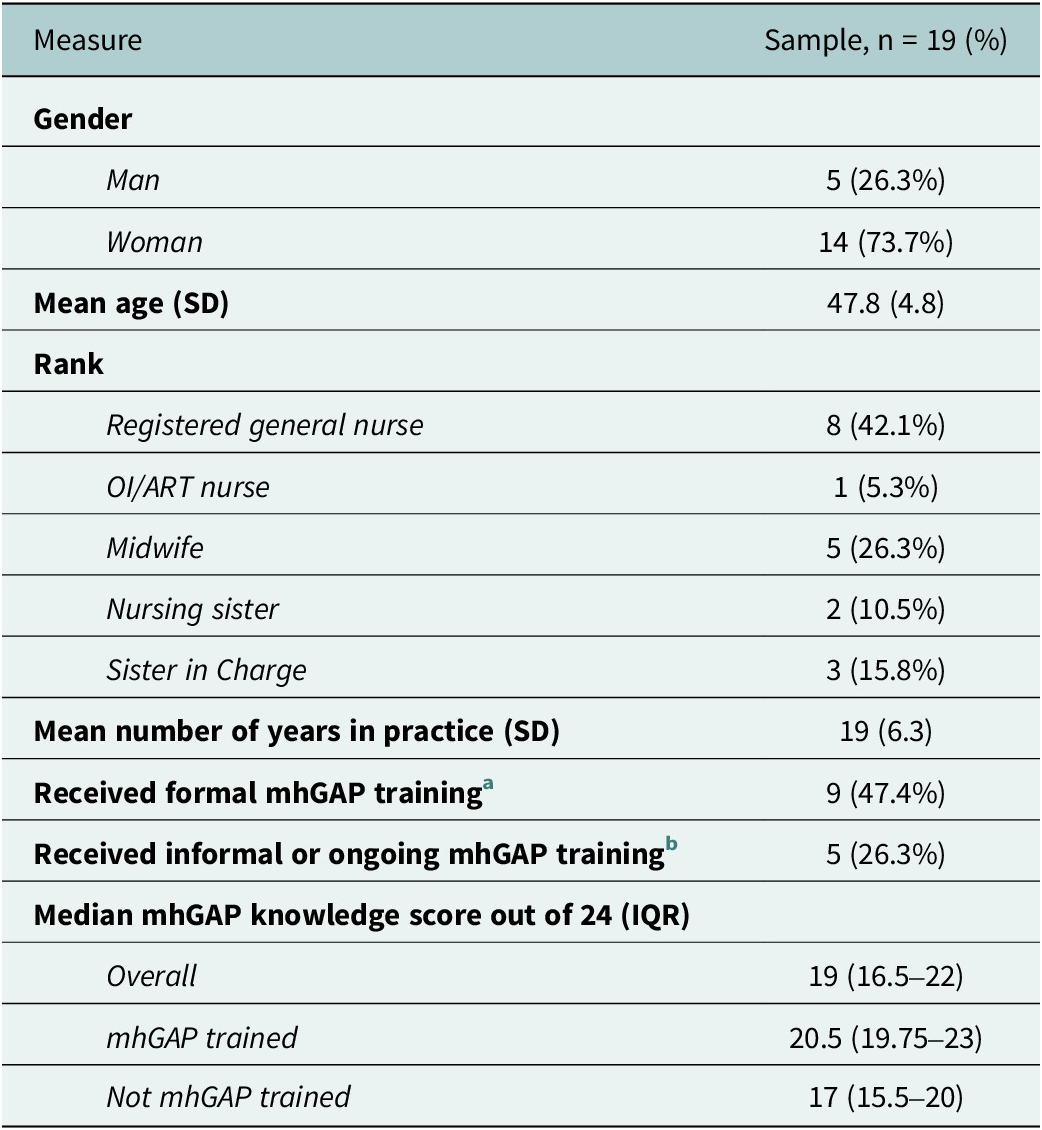

Twenty-three nurses saw patients in the sample, of whom four were excluded due to not being permanently assigned to the clinic or not being able to be reached. Nineteen nurses participated in the survey (Table 3). Seventy-four percent of the nurse participants were women, with a mean age of 48 years. Three had most recently completed mhGAP training between 2015 and 2017, and five most recently completed mhGAP training in 2024, after patient data collection had taken place at their clinic.

Table 3. Characteristics of nurse sample

a Training took place in 2016, 2017 and 2024 and was delivered by Medecins Sans Frontiers, Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization. If nurses were trained in mhGAP more than once, the latest training date is listed here. Five nurses reported most recent mhGAP training dates that occurred after patient data collection had begun at their clinic.

b Only nurses who reported receiving formal mhGAP training reported receiving any informal or ongoing mhGAP training.

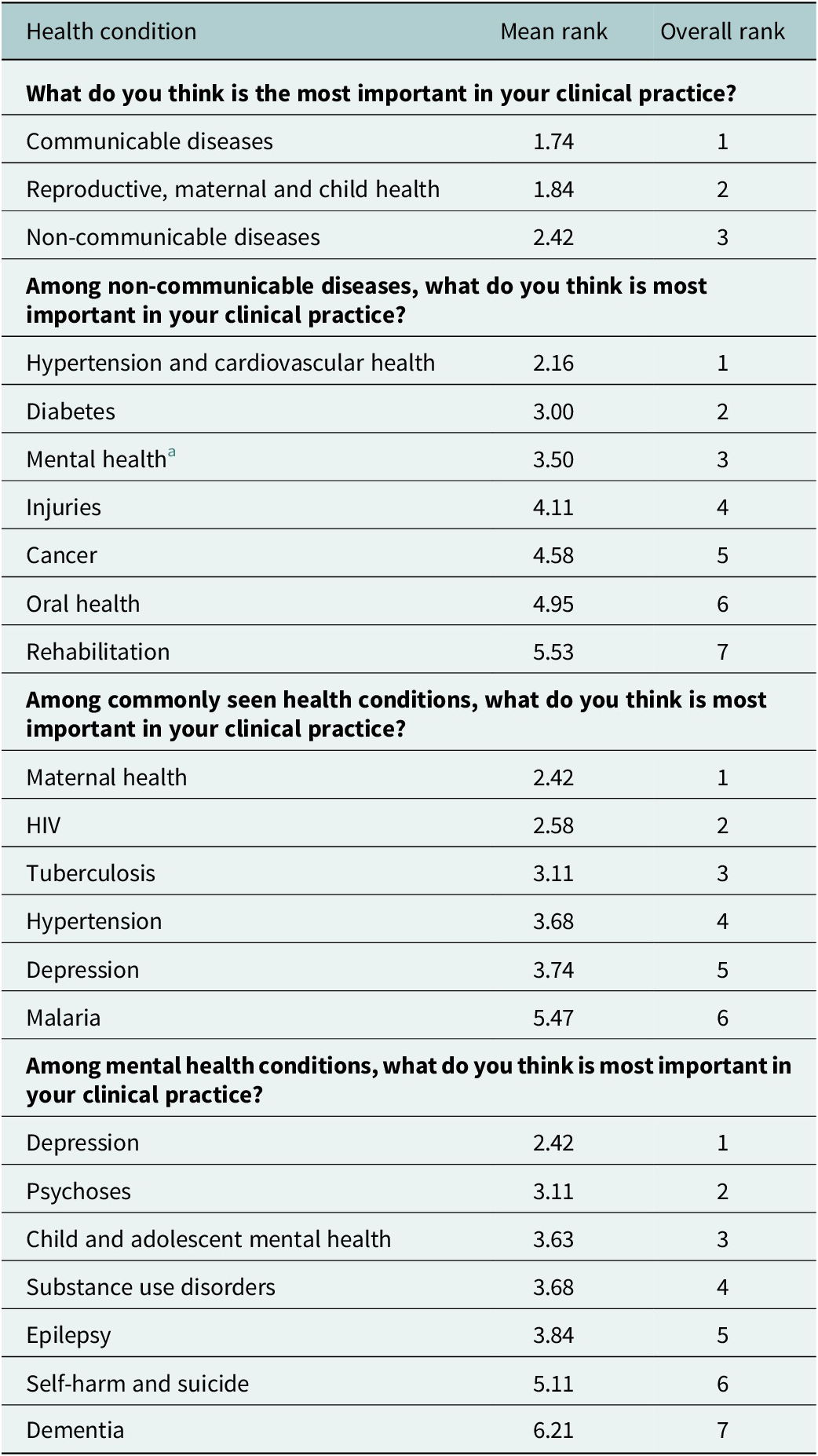

The median score on the mhGAP knowledge test was 19/24 for all nurses, 20.5/24 for those who had previously been trained in mhGAP, and 17/24 for those who had not previously been trained. Prioritization of medical conditions within their practice is displayed in Table 4. Communicable diseases were a higher priority than non-communicable diseases or reproductive, maternal and child health. Among non-communicable diseases, mental health was ranked third of seven, and depression was the highest priority mental health condition.

Table 4. Nurse priorities within clinical practice (Ministry of Health and Child Care, 2020)

a Missing one response.

Discussion

We assessed depression recognition by primary care nurses in the context of a decade of ongoing efforts to scale up mental healthcare in primary healthcare in Zimbabwe. We found that nurses did not record diagnosis or treatment of depression for any of those who screened positive for depression based on either the PHQ-9 or the SSQ-14. Prevalence of depression in the sample, however, was lower than anticipated, and most of the nurses had never received formal mhGAP training. Based on review of medical notes and patient-reported treatment plans, we identified several instances in which mental healthcare was documented, including referral to counseling at a church and refills of existing psychotropic medications, which suggests an important success of mental health integration into primary care.

There are several reasons why nurses may not have recognized people with probable depression. First, primary care nurses face many competing demands and have limited staffing. Many nurses have left Zimbabwe due to poor working conditions and inadequate salaries, leaving unfilled roles in primary care. There were both cholera and dysentery outbreaks during the study period, which pulled staff away from the clinic. Lack of time is cited as a barrier to depression recognition in studies in both LMICs and high-income countries (Cepoiu et al., Reference Cepoiu, McCusker, Cole, Sewitch, Belzile and Ciampi2008; Zimba et al., Reference Zimba, Malava, Mbota, Matewere, Akello, Akiba, Landrum, Morrison, Go, Hosseinipour, Gaynes, Udedi, Masiye and Pence2025), and nurses in Zimbabwe face extreme time constraints, with about 55% of nurses taking less than 10 minutes with each patient (Chikanda, Reference Chikanda2005). Due to the lack of time, nurses likely had to prioritize what issues they addressed for each patient. Even if they had the clinical skills to recognize depression, they may have chosen not to due to competing priorities. The nurses in this study reported that depression is not a high priority, ranking it fifth of six in terms of importance among commonly seen conditions in primary care, below maternal health, HIV, tuberculosis and hypertension, all of which were very common based on our review of medical records. Additionally, nurses may not have had adequate training on how to identify depression. Very few nurses had been formally trained in mhGAP prior to patient data collection, even though all clinics had been included in prior trainings. The low proportion of nurses trained is likely due to high nurse turnover in public sector clinics. Finally, nurses may have normalized depressive symptoms in the challenging context in which they work: the African cultural idiom “Upenyu mutoro,” translated to “life is a burden,” frames kufungisisa (thinking too much or depression) as normal, potentially causing nurses to accept depressive symptoms as the norm amidst the general challenges many of their patients face (Ngwenya, Reference Ngwenya2020).

There was, however, clear evidence that nurses were incorporating mental health into their practice. Three patients received refills of medications for a presumed psychotic disorder, and another received an antidepressant refill and had recovered from depression based on screening results. Nearly one-third of patient participants reported having previously been diagnosed with depression, and 23.1% of those reported having received counseling. The plurality of those with prior treatment (28.5%), however, stated that they had received treatment for hypertension. This is consistent with prior research in Zimbabwe showing that depression and hypertension are seen as synonymous (Kidia et al., Reference Kidia, Machando, Dzoro, Chibanda, Abas, Manda, Mutengerere, Nyandoro, Chawarika, Majichi, van Dijk and Jack2024), both as manifestations of stress. This makes it challenging to interpret what a prior diagnosis of depression means to patient participants, and it is likely not all were diagnosed with depression as understood in a Western medicine context.

Examination of the presentations of patients with PHQ-9 scores consistent with probable depression shows that many people presented with chronic, non-specific pain or dizziness or with medication non-adherence. None of the patients with PHQ-9 scores of 0 presented this way. Depression would conceivably be on the differential diagnosis for patients with these presentations, given that somatic manifestations of depression (Caballero et al., Reference Caballero, Aragonès, García-Campayo, Rodríguez-Artalejo, Ayuso-Mateos, Polavieja, Gómez-Utrero, Romera and Gilaberte2008) are common in Zimbabwe, and HIV medication non-adherence has also been associated with depression in several prior studies (Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Kinyanda, Chishinga, Prince and Patel2012; Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., Reference Nakimuli-Mpungu, Bass, Alexandre, Mills, Musisi, Ram, Katabira and Nachega2012).

The prevalence of depression in this study was lower than we anticipated. Other studies in Zimbabwean primary care have found very high prevalence of depression (up to 70%) (Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Verhey, Gibson, Munetsi, Machando, Rusakaniko, Munjoma, Araya, Weiss and Abas2016b; Verhey et al., Reference Verhey, Gibson, Brakarsh, Chibanda and Seedat2018; Velloza et al., Reference Velloza, Hosek, Donnell, Anderson, Chirenje, Mgodi, Bekker, Delany-Moretlwe and Celum2021), markedly higher than many global and regional estimates (GBD, 2019; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019). Within Zimbabwe, prevalence estimates in primary care, HIV care and community settings have varied considerably (Mebrahtu et al., Reference Mebrahtu, Sherr, Simms, Weiss, Chingono, Rehman, Ndlovu and Cowan2020), with many in community settings and several in HIV or TB care finding a prevalence of <20% (Abas and Broadhead, Reference Abas and Broadhead1997; Sebit et al., Reference Sebit, Chandiwana, Latif, Gomo, Acuda, Makoni and Vushe2002; Haney et al., Reference Haney, Singh, Nyamukapa, Gregson, Robertson, Sherr and Halpern2014; Chin et al., Reference Chin, Rylance, Makumbirofa, Meffert, Vu, Clayton, Mason, Woodruff and Metcalfe2019; Machisa and Shamu, Reference Machisa and Shamu2022). Variation in whether a screening or diagnostic tool was used and what tool was used may explain some of these differences. The prevalence that we found – 6% prevalence of probable depression with PHQ-9 and 22% prevalence of probable depression or anxiety with SSQ-14 – aligns with the lower end of Zimbabwean estimates (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Simunyu, Gwanzura, Lewis and Mann1997; Sebit et al., Reference Sebit, Tombe, Siziya, Balus, Nkomo and Maramba2003; Chibanda et al., Reference Chibanda, Verhey, Gibson, Munetsi, Machando, Rusakaniko, Munjoma, Araya, Weiss and Abas2016b; Haas et al., Reference Haas, Kunzekwenyika, Manzero, Hossmann, Limacher, van Dijk, Manhibi, von Groote, Hobbins, Verhey and Egger2023) and most global and regional estimates (GBD, 2019).

These findings have several implications for practitioners and policymakers. First, routine screening for depression is one strategy for improving depression detection, and screening has been used successfully in a limited number of other African settings, often when tied with broader efforts to support mental health treatment within primary care (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Bhana, Fairall, Selohilwe, Kathree, Baron, Rathod and Lund2019; Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Milkias, Birhane, Tekola, Yared, Eshetu, Getahun, Lempp, Tylee, Belina, Medhin, Habtamu, Alem, Lund, Petersen, Thornicroft, Cleare, Mayston, Assefa, Demissie, Hanlon and Prince2025). Since this study was conducted, the Zimbabwean Ministry of Health has begun encouraging universal screening with the PHQ-9. However, it is not yet clear if screening is acceptable, feasible or appropriate in Zimbabwe (Oladeji et al., Reference Oladeji, Kola, Abiona, Montgomery, Araya and Gureje2015; Reynolds and Patel, Reference Reynolds and Patel2017; Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Milkias, Birhane, Tekola, Yared, Eshetu, Getahun, Lempp, Tylee, Belina, Medhin, Habtamu, Alem, Lund, Petersen, Thornicroft, Cleare, Mayston, Assefa, Demissie, Hanlon and Prince2025). Second, neither nurses who had been trained in mhGAP nor those who had not been trained in mhGAP recognized depression, and both groups had relatively high scores on the mhGAP knowledge test. This suggests that many nurses may have the clinical knowledge of how to treat depression, but they do not know how to identify it or do not prioritize identifying it within their practice. Future interventions could incorporate greater emphasis on case recognition into both training and ongoing supervision, and highlight common presenting symptoms in the Zimbabwean cultural context for which depression should be on the differential diagnosis, such as chronic pain, headaches or medication non-adherence (Table 2). To prioritize depression in the resource-limited Zimbabwean context, nurses may need more well-staffed clinics and additional support to address the many other urgent priorities they see. Finally, we found a very high prevalence of food insecurity and informal employment or unemployment. Particularly in light of the challenging economic and political situation in Zimbabwe, the bidirectional relationship between poverty and depression should be considered in efforts to scale up depression screening and treatment (Lund and Cois, Reference Lund and Cois2018; Ridley et al., Reference Ridley, Rao, Schilbach and Patel2020; Califf et al., Reference Califf, Wong, Doraiswamy, Hong, Miller and Mega2022; Lund et al., Reference Lund, Jordans, Garman, Araya, Avendano, Bauer, Bahure, Dua, Eleftheriou, Evans-Lacko, García Rodríguez, Gautam, Gevonden, Hessel, Kohrt, Krabbendam, Luitel, Roy, Seifert Bonifaz, Singh, Sinichi, Sorsdahl, Thornicroft, Tol, Trujillo, van der Merwe, Wahid and Yarrow2023).

This study has several limitations. First, we used screening tools, not diagnostic interviews, to determine cases of probable depression, a feature shared by most studies of depression identification in Africa (Fekadu et al., Reference Fekadu, Demissie, Birhane, Medhin, Bitew, Hailemariam, Minaye, Habtamu, Milkias, Petersen, Patel, Cleare, Mayston, Thornicroft, Alem, Hanlon and Prince2022; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Gurung, Singh, Rai, Neupane, Turner, Platt, Sun, Gautam, Luitel and Jordans2025a). However, we chose a higher cut-point (11) to reduce the risk of false positives and conducted additional analyses using a locally developed, cross-diagnostic tool (SSQ-14). Second, medical notes may not capture everything that happened in a visit, particularly in a busy primary care clinic and for a highly stigmatized condition. Nurses may have provided counseling or treatment for depression without recording it in the medical record (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vaze and Rao2009), perhaps due to stigma. Third, we cannot draw any conclusions about a specific mhGAP training or about mhGAP broadly, particularly as most nurses had not been exposed to formal mhGAP training, and repeat training was ongoing. Rather, we examined current practices in a real-world environment that has been exposed to multiple efforts to improve mental healthcare. Fourth, we sampled a relatively small number of patients with depression across four primary care clinics. Depression recognition may differ in other parts of the country. Fifth, the nurse survey used international, standardized tools to assess mental health knowledge, so it was not able to assess local idioms or understandings of depression and used the word “depression” rather than the local language word kufungisisa.

Conclusion

Despite multiple efforts to increase depression treatment in Zimbabwe, nurses documented no recognized cases of depression among those who screened positive based on a researcher-administered screening tool. In Zimbabwe, recognition is a barrier to depression treatment. Routine screening in primary care or additional focus on depression diagnosis and management in primary care during medical and nursing school may help increase recognition. Future research should examine the acceptability, feasibility and effectiveness of different types of nurse training on depression recognition and management, and should examine strategies for patient screening, including self-administered screening, targeted screening for high-risk groups and routine screening for all patients.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2026.10130.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Sebias Ndebele for his assistance with this study.

Author contributions

Sakios Muduma: methodology, investigation, validation, data curation, visualization, writing – original draft. Malinda Kaiyo-Utete: conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, funding acquisition, writing – review and editing. Zoë Senter: data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing – review and editing. Debra Machando: writing – review and editing. Kevin Hallgren: methodology, software, validation, supervision, writing – review and editing. Emily Williams: methodology, supervision, writing – review and editing. Dixon Chibanda: conceptualization, writing – review and editing. Melanie Abas: supervision, writing – review and editing. Patience Mavunganidze: writing – review and editing. Graham Thornicroft: conceptualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. Helen Jack: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, supervision, funding acquisition.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (HEJ, K23MH129420) and the African Mental Health Research Initiative II (MKU, Del-22-004). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Zimbabwe Joint Research Ethics Committee (JREC/113/2023), the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/3046), the Research Council of Zimbabwe (No. 04920), City of Harare Health Department and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (STUDY00019921). Participation in the study was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from participants prior to data collection.

Comments

No accompanying comment.