Introduction

The quality of patient care is intricately linked to the cognitive functioning and performance of care providers. Although estimates differ by specialty, roughly 25% of healthcare is delivered by medical residents (Edwards et al. Reference Edwards, Kim, Shull, Hooker, Niederhausen and Tuepker2019). This proportion of resident-patient care is subserved by the traditional residency training model. This model is over a century old and encompasses an extended period of intense training that is accompanied by long hours and high work demands that extend beyond the clinical environment through additional educational and academic responsibilities (Gates et al. Reference Gates, Kemp and Evans2023). Recently, the rigor of contemporary training practices has been scrutinized due to decremental performance effects of trainees – specifically with respect to cognitive functioning. Research is pointing to insufficient sleep and disrupted circadian rhythms as key mechanisms responsible for decrements in cognitive function and overall performance (McEwen and Karatsoreos, Reference McEwen and Karatsoreos2015). A typical US resident often works 60–80 hours per week, with overnight or “on-call” shifts ranging from 12 to 28 hours and limited recovery time between rotations. Such schedules make chronic sleep deprivation nearly unavoidable, underscoring the importance of this discussion (ResearchGate, 2025).

Sleep insufficiency

Sleep quality and sleep/wake architectures can differentially affect cognitive functions, such as memory consolidation, problem-solving and decision-making (Newbury et al. Reference Newbury, Crowley, Rastle and Tamminen2021; Whitney et al. Reference Whitney, Kurinec and Hinson2023). When sleep is restricted or fragmented, residents experience deficits across multiple cognitive domains – including memory retention, attentional control and complex decision-making – all of which are vital in high-stakes professions such as medicine.

Sleep deprivation has profound consequences for medical residents, whose demanding schedules often result in chronic sleep insufficiency. This persistent lack of restorative sleep impairs essential cognitive functions such as decision-making, memory, attention and concentration, leading to increased medical errors and compromised learning (Bartel et al. Reference Bartel, Offermeier, Smith and Becker2004; Basner et al. Reference Basner, Dinges and Shea2017; Richardson and Malin, Reference Richardson and Malin1996; Whelehan et al. Reference Whelehan, Alexander, Connelly, McEvoy and Ridgway2021). Studies have established a strong correlation between inadequate sleep and performance errors, attributing these mistakes to diminished attention and focus (Saadat, Reference Saadat2021). For example, errors commonly involve medication dosing, diagnostic interpretation and procedural lapses during night shifts. The cumulative effects of sleep deprivation not only undermine resident education but also reduce the quality of patient care and elevate the risk of preventable errors. Addressing sleep insufficiency in residency is therefore critical for improving both clinical outcomes and patient safety. In the context of this manuscript, “sleep deprivation” refers to obtaining less than 6 hours of total sleep per 24-hour period for at least several consecutive days, whereas an “adequate amount of sleep” generally denotes 7–9 hours per 24 hours for optimal cognitive functioning.

Circadian disruption

The circadian clock, regulated by the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus, synchronizes numerous physiological processes by aligning them with external cues such as light exposure and meal timing. However, the irregular work hours and night shifts common in medical residency disrupt these signals, leading to circadian misalignment. This disruption impairs cognitive functions like attention and decision-making and increases the likelihood of medical errors, with effects comparable to those caused by fatigue or alcohol consumption (Arnedt et al. Reference Arnedt, Owens, Crouch, Stahl and Carskadon2005; Boivin et al. Reference Boivin, Boudreau and Kosmadopoulos2021; Dawson and Reid, Reference Dawson and Reid1997; Durmer and Dinges, Reference Durmer and Dinges2005).

Beyond cognitive deficits, circadian misalignment disrupts hormonal regulation, particularly cortisol secretion, which typically follows a natural rhythm – peaking in the morning and declining throughout the day. Night shifts and extended work hours dysregulate this cycle, contributing to heightened stress, emotional instability and increased burnout among medical professionals (De and Hert, 2020; Ibar et al. Reference Ibar, Fortuna and Gonzalez2021; Marques-Pinto et al. Reference Marques-Pinto, Moreira, Costa-Lopes, Zózimo and Vala2021). These disruptions exacerbate fatigue, impair learning and further increase the risk of errors, ultimately compromising both resident well-being and patient safety. Studies of other shift-working professions (e.g., nurses, airline pilots and emergency responders) similarly show that circadian misalignment decreases vigilance and reaction time, suggesting that lessons from these fields may inform medical education reforms. Addressing these challenges requires targeted interventions to mitigate circadian misalignment and support the physiological and cognitive needs of medical trainees.

Cognitive functioning in medical residents

The cognitive and emotional demands during medical residency are intense, and the prolonged work hours and work-scheduled irregularities exacerbate these demands. The consequences of sleep deprivation on cognitive functioning and performance in medical residents cannot be overstated. They impact one’s decision-making, memory, attention, concentration and emotional regulation – a combination that can be detrimental to patient care. The situations residents often face demand prompt and accurate clinical judgments. Sleep loss impairs executive functions governed by the prefrontal cortex, which are crucial for integrating and responding to clinical information. Research indicates major shortcomings in the residents’ decision-making when they are deprived of sleep, which can lead to a heightened number of medical mistakes (Comondore et al. Reference Comondore, Wenner and Ayas2008). Sleep deprivation compromises the brain’s ability to process the risks and rewards associated with choices, further leading to impaired decision-making (Khan et al. 2023).

Evidence shows that sleep-deprived individuals experience slower reaction times, reduced focus and impaired judgment, which compromise their ability to perform tasks that demand high levels of cognitive engagement. Steele et al. (Reference Steele, Ma, Watson, Thomas and Muelleman1999) demonstrated that emergency medicine residents, often working under conditions of chronic sleep loss, faced an elevated risk of motor vehicle collisions due to diminished attention and response capabilities. Similarly, Mak et al. further identified a higher incidence of car accidents involving residents following on-call shifts, linking poor sleep to critical lapses in concentration and situational awareness. These findings underscore how inadequate rest disrupts the cognitive and emotional processes essential for safe driving, emphasizing the broader consequences of sleep deprivation in high-stakes environments.

An adequate amount of sleep is fundamental not only to overall learning but also to memory retention. Sleep serves a vital, if still incompletely understood, function in the consolidation of both declarative memory (e.g., lab interpretation, disease presentation, diagnostic criteria) and procedural memory (e.g., performing a physical exam, suturing, intubation). Research studies have shown that a lack of adequate sleep leads to marked impairments in the retention and retrieval of knowledge (Newbury et al. Reference Newbury, Crowley, Rastle and Tamminen2021). Furthermore, memory consolidation and the ability to learn new medical procedures along with the capacity to retain factual knowledge are significantly impaired by the interruption of rapid eye movement sleep and slow wave sleep (Purim et al. Reference Purim, Guimarães, Titski and Leite2016).

Sleep deprivation impairs the ability to focus and sustain attention on cognitive tasks, with extended wakefulness further exacerbating these deficits. A medical resident who is not getting enough sleep is at risk for attentional lapses in settings such as protracted surgical procedures or in the relatively stable, patient-monitored context of the intensive care unit. Prolonged wakefulness has been shown to impair not just the ability to pay attention but also the sustained attention needed for a number of operations that one would generally perform in the context of cognitive load (Whelehan et al. Reference Whelehan, Alexander, Connelly, McEvoy and Ridgway2021).

In addition, the overall performance of medical residents depends a great deal on how well they sleep (Jaradat et al. Reference Jaradat, Lahlouh, Aldabbour, Saadeh and Mustafa2022; Philibert, Reference Philibert2005). They are prone to cognitive dysfunction when their sleep quality is poor, which elevates the frequency with which they make medical errors and the overall efficiency with which they perform clinical tasks, such as interpreting imaging and lab results, patient assessments and surgical procedures (Jaradat et al. Reference Jaradat, Lahlouh, Aldabbour, Saadeh and Mustafa2022).

Emotional regulation and stress are also influenced by a lack of sleep. The way in which we manage moods and control emotions is closely tethered to how well we sleep. Sleep deprivation increases one’s irritability and frequency of mood swings and even exacerbates symptoms of depression and anxiety (Tomaso et al. Reference Tomaso, Johnson and Nelson2020).

The current body of literature demonstrates that being fatigued and having poor sleep quality affect many cognitive dimensions of a medical resident’s life and optimal functioning. The cumulative effects of poor sleep quality and sleep and circadian disruptions compromise decision-making, memory, attention, concentration and emotional regulation, which are all necessary dimensions of safe and successful medical practice and effective residency training. Moreover, early-career physicians appear especially vulnerable to these deficits compared with more experienced clinicians, as suggested by data showing that less-experienced physicians demonstrate steeper declines in performance following extended wakefulness. Whether we are looking at system changes or individual changes that we can make as residents, the future effect of sleep health on residency performance is an important issue to address. We next turn to potential mitigating strategies.

Practical implications for medical education and patient care

Sleep deprivation in medical residents is well documented, with grueling work schedules often preventing adequate, restorative sleep (Basner et al. Reference Basner, Dinges and Shea2017; Saadat, Reference Saadat2021; Walker, Reference Walker2018). While work-life balance is crucial, sleep frequently becomes a casualty of scheduling conflicts, despite its vital role in cognitive function, emotional stability and overall well-being. To address these challenges, medical institutions must implement structured, evidence-based policies that promote sleep health and reduce fatigue-related errors.

One essential strategy is the implementation of protected sleep times, ensuring residents have designated, uninterrupted periods for rest. Studies have shown that these measures improve alertness and cognitive performance and significantly reduce medical errors (Rodziewicz et al. Reference Rodziewicz, Houseman, Vaqar and Hipskind2024). Strategic napping during long shifts is another effective intervention that helps counteract cognitive deficits associated with extended wakefulness (Durmer and Dinges, Reference Durmer and Dinges2005). Additionally, limiting shift lengths, promoting flexible scheduling and monitoring sleep quality and cognitive performance can help institutions assess and refine their policies for resident well-being (Rodziewicz et al. Reference Rodziewicz, Houseman, Vaqar and Hipskind2024).

However, despite growing evidence, barriers to implementing these changes persist. Common obstacles include staffing shortages, institutional resistance to altering long-standing training structures and concerns about reduced clinical exposure. Surveys of residents and attending physicians reveal mixed attitudes – while many residents favor shorter shifts and protected sleep time, some supervisors express concern that such changes may limit continuity of care or slow professional growth. Addressing these attitudes will be essential for achieving meaningful reform.

The European Working Time Directive (EWTD), implemented in 2003 and refined thereafter, provides a comparative framework. It limits physicians in training to an average of 48 working hours per week, mandates a minimum rest period and sets requirements for continuous time off between shifts. The EWTD serves as a successful model, demonstrating how regulated work hours can reduce fatigue-related errors and enhance resident well-being (Walker, Reference Walker2018). The long-term consequences of chronic sleep deprivation, including cognitive impairment, burnout, depression and anxiety, may extend into physicians’ post-training years and negatively impact patient care (Walker, Reference Walker2018). Given these risks, addressing sleep health at both institutional and regulatory levels is critical to ensuring the long-term success of medical professionals and the safety of their patients. Implementing structured sleep management strategies will improve residency training outcomes and support the sustainability of the healthcare workforce.

Next steps

The next steps in addressing the impacts of sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment on medical residents should build on the existing research (Basner et al. Reference Basner, Dinges and Shea2017; Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Reed and Arora2011). A key focus must be the development and testing of interventions that address the limitations of current work hour regulations. While the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) work hour reforms were intended to improve resident well-being, it has been found that although these regulations reduced weekly work hours, they did not completely eliminate extended shifts, night shifts or sleep deprivation (Fletcher et al. Reference Fletcher, Reed and Arora2011). At that time, the ACGME limited residents to an average of 80 work hours per week, with a maximum of 24 consecutive hours of in-hospital duty, mandatory one day off in seven and ten hours off between shifts. These rules have since evolved but continue to face compliance challenges.

It is essential to conduct longitudinal studies to evaluate the total impact of sleep deprivation on medical trainees throughout their careers. These research projects should systematically track the effects of sleep loss and circadian desynchrony on cognitive performance, burnout rates, mental health and job satisfaction. In addition, monitoring patient safety outcomes of residents in programs that have adopted new schedules – those that allow for more sleep and fewer consecutive nights of being on call – compared to those in traditional, more demanding programs, is essential to inform best practices in training. The work done in these studies will be crucial not just for understanding the toll that sleep deprivation takes on the minds and bodies of residents but also for comprehending the implications for the care of their patients.

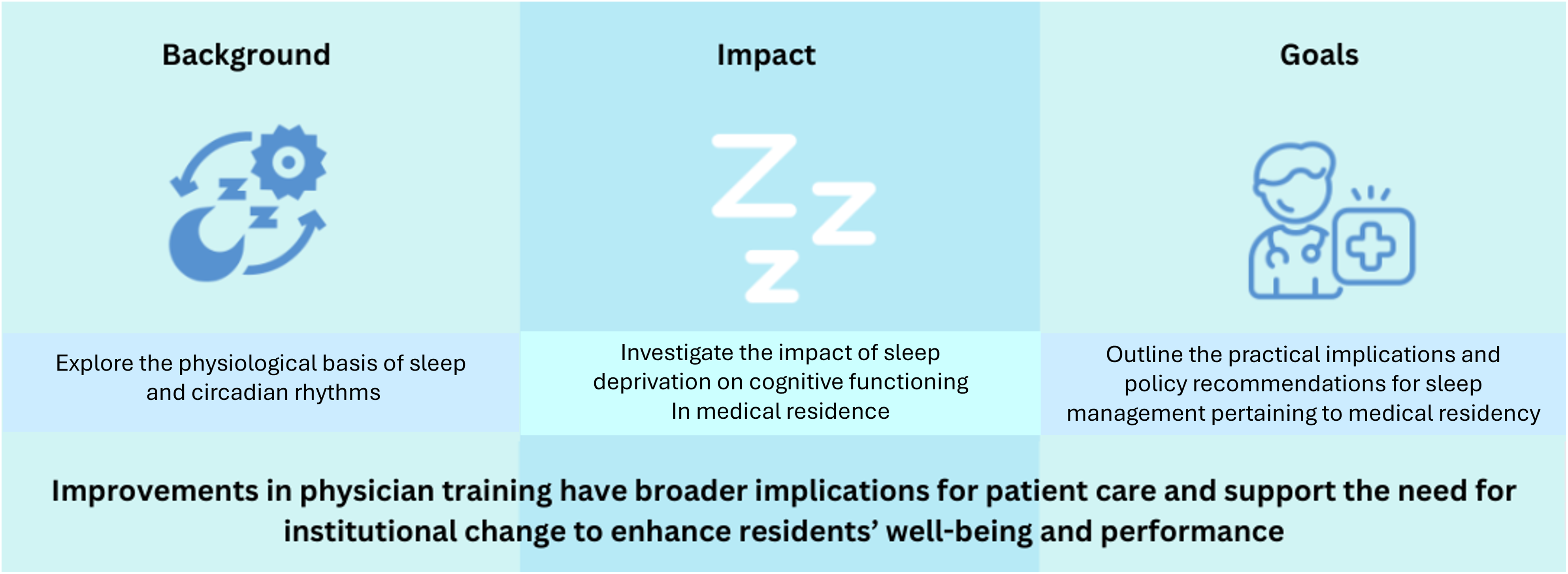

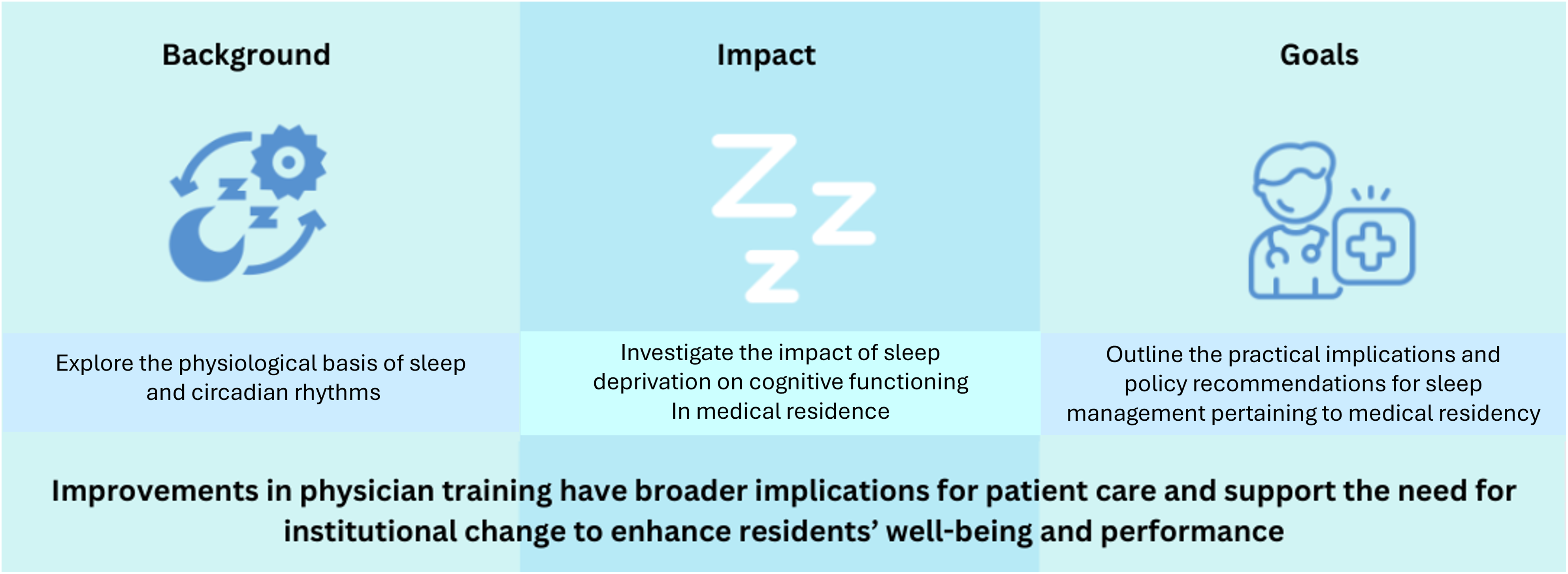

One major area of concentration is increasing the number of safety nets for residents. As illustrated in Figure 1, the physiological basis of sleep and its cognitive impact highlights why such protections are essential. The ACGME’s push for duty hour reforms was an important first step, but it is not enough. As Fletcher et al. (Reference Fletcher, Reed and Arora2011) pointed out, residents are still overloaded and overworked. We’ve yet to reach the point of fully understanding how day-to-day life in residency can wear down one’s mental health, even if it doesn’t rise to the level of morbidities we might cover in any number of medical specialties.

Figure 1. Graphical abstract depicting the physiological basis of sleep, its impact on residents’ cognitive function and policy recommendations for better sleep management in medical training.

In addition, utilizing tools such as smart wristbands that monitor sleep can give residents information about their sleep optimization opportunities. Devices that offer this kind of service can mitigate potential crisis situations by preemptively identifying residents who might be at risk for a significant sleep deficit. Another strategy worth exploring is the “night-float” system, where residents rotate exclusively on overnight duty for a limited period. While this model reduces excessively long shifts, it continues to disrupt circadian rhythms, highlighting the need for future innovations that better balance workload with physiological demands.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings presented above underline the critical need for a reformation of policies surrounding the ACGME. Although the 2003 duty hour regulations did aim to enhance the well-being of residents and the safety of patients, it appears that they fell short – that is, the regulations did not fully counteract the problems tied to extended work hours, night work and insufficient sleep. Further policy changes could substantially reduce the cognitive impairments and medical errors associated with sleep deprivation, leading to improved patient outcomes and enhanced resident well-being. Balancing reforms with the realities of patient-care continuity and training sufficiency will be crucial, as both residents and faculty must adapt to new structures that protect sleep without compromising education. Advocating for these reforms both at the institutional and at the regulatory level is crucial to sustaining long-term improvements in the health of residents and the quality of care delivered to patients.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

K. A. VanBockern: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft/review and editing, Funding acquisition (if from ESFCOM). C.J. Davis: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval and consent are not relevant to this article type.

Comments

No accompanying comment.