Introduction

Information provision is a key aspect of lobbying. Policymakers need expert information, that is, technical information to anticipate the effectiveness of a policy proposal as well as information on public preferences to anticipate electoral consequences (Truman, Reference Truman1951; Wright, Reference Wright1996; Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2015). Consequently, information has often been seen as the ‘currency in lobbying’ (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013) or the ‘stock in trade’ (Nownes, Reference Nownes2006) and as a resource that interest groups provide to policymakers in exchange for access and influence (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002; Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). The fact that policymakers need information that interest groups have leads to an information asymmetry (Gilligan and Krehbiel, Reference Gilligan and Krehbiel1989: 460; Ainsworth, Reference Ainsworth1993: 47; Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2015) and makes information a potential source of influence for interest groups.Footnote 1 However, information gathering and transmission is costly and requires resources itself (Austen-Smith and Wright, Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1992; Wright, Reference Wright1996). Yet little is known about the costs of such information which is why the paper sets out to assess the costs of information provision. Given that advocates lobby, by and large, on specific policy proposals (Burstein, Reference Burstein2014), the information that is necessary for legislative lobbying is not necessarily off-the-shelf information. For example, an organization may have overall knowledge on the fuel emissions of cars but lacks information on the impact of auto exhaust fumes on humans. Obtaining such information requires resources such as staff, money, or research capacities.

Scholars have argued that there is a relationship between financial resources and the amount of information they supply (Klüver, Reference Klüver2012; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014), and that information provision is a function of a group’s internal capacities (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). This suggests that actors with more resources can provide more information and subsequently enhance their chances of lobbying success. However, variation in the extent to which advocates are able to provide information can cause bias and foster political inequality (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960; Schlozman and Tierney, Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986). This is problematic from a normative perspective as it favours actors that are able to pay the costs of information-gathering (Hall and Deardorff, Reference Hall and Deardorff2006: 81). Moreover, interest groups are often portrayed as transmission belts of the public (cf. Truman, Reference Truman1951; Gilens and Page, Reference Gilens and Page2014; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Carroll and Lowery2014; Lowery et al., Reference Lowery, Baumgartner, Berkhout, Berry, Halpin, Hojnacki, Klüver, Kohler-Koch, Richardson and Schlozman2015), by passing on information about public preferences to policymakers (Bevan and Rasmussen, Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2017; Eising and Spohr, Reference Eising and Spohr2017). If more resources facilitate the transmission of such information, it poses a threat to representation as it favours those that are well endowed (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960). Hence, the cost of gathering information can introduce bias and favour resourceful groups (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960) that do not only dominate in terms of sheer numbers (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960; Baumgartner and Leech, Reference Baumgartner and Leech2001) but may also provide more and better arguments. Understanding the costs of information may hence contribute to our understanding of bias in interest representation.

The paper contributes to this debate by applying a resource perspective on informational lobbying. While previous research argues that higher material resources lead to more information provision (cf. Klüver, Reference Klüver2012), interest groups have other capacities that may be valuable as well. In addition to economic resources, which are defined as an organization’s financial means, groups possess political capacities. Political capacities refer to the ability to represent the public or a constituency (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015; Daugbjerg et al., Reference Daugbjerg, Fraussen, Halpin, Xun, Howlett and Ramesh2018), to act as a mediating actor between citizens and policymakers (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Braun2017b), but also to mobilize the public and generate support (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013; Fraussen and Beyers, Reference Fraussen and Beyers2016; Daugbjerg et al., Reference Daugbjerg, Fraussen, Halpin, Xun, Howlett and Ramesh2018). The paper argues that while the provision of expert information indeed requires economic resources, information on public preferences can, above all, be acquired with a group’s political capacities rather than its economic resources. Empirically, the paper relies on new data collected within the GovLis project.Footnote 2 The dataset comprises interest group activity on 50 specific policy issues in five West European countries (Denmark, Sweden, Germany, UK, and the Netherlands) and relies on detailed media coding, expert interviews, desk research, and a survey. This research design allows for analyzing information that advocates have provided on a variety of specific policy issues and covers different systems of interest representation.

The findings indicate both similarities and differences in how resources affect the different types of information provision. While economic resources facilitate the provision of expert information, political capacities are also associated with a higher provision of expert information. This could suggest that even if groups do not have a lot of economic resources, they can still acquire expert information by using their political capacities. Political capacities also facilitate the provision of information about public preferences, while there is less evidence for economic resources. Actors drawing on their political capacities are therefore also more likely to provide both types of information. The paper adds to the literature on informational lobbying (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016; Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016) by assessing the drivers of information provision, in particular, the types of resources that are necessary for gathering information. By showing a relationship between resources and information provision, it supports research that argues that information is costly and can be used strategically (Austen-Smith and Wright, Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1992; Wright, Reference Wright1996) but adds that the costs and resources may vary depending on the type of information. Moreover, it suggests that if groups do not spend economic resources on lobbying activities (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2015; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Fisker and Pedersen2016; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016), they may have the potential to create a more level-playing field by making strategic use of other resources.

The costs of information

As mentioned, policymakers need political and expert information, which interest groups are able to provide (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). Expert information in this paper is defined as information on technical details, the effectiveness of a policy, its legal aspects as well as its economic impact. Political information is often used to pressure policymakers and will be defined in this paper as information on public preferences, referring to information on public preferences, electoral consequences, or moral concerns (ibid.: 601). Importantly, this is not restricted to general public opinion but also includes information of a specific constituency such as members or a somewhat broader constituency that will allegedly benefit from the lobbying efforts of a group. Information is often seen as a resource (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002; Dür and De Bièvre, Reference Dür and De Bièvre2007; Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2013); however, information requires resources itself, and the ability to provide different kinds of information varies across actors. Moreover, much of the scholarly work uses group type as a proxy for the type and amount of information that is available (Yackee and Yackee, Reference Yackee and Yackee2006; Coen, Reference Coen2007; Dür and De Bièvre, Reference Dür and De Bièvre2007; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014), when in fact there are no differences across different types of groups regarding information provision (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016; Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016). Others regard an interest group’s information supply as a function of its organizational capacity (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2002; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). Indeed, some have shown that financial resources affect the amount of information an organization is able to provide (cf. Klüver, Reference Klüver2012) and that interest group influence is a function of the extent to which a group is capable of acquiring and transmitting information that is demanded by policymakers (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2011: 472). Given that groups differ in the extent to which they can provide information, those with fewer resources may be disadvantaged. However, while economic resources are undoubtedly important, actors may be able to use their political capacities to collect and provide information on public preferences.

What resources do interest groups have?

Interest groups possess a variety of resources such as financial means, legitimacy, representativeness, knowledge, members, or the ability to mobilize the public (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016), which will be divided into economic resources and political capacities. First, all organizations have financial means which can be used on lobbying activities and fall under economic resources. This includes the material resources an interest group has spent on lobbying (Klüver, Reference Klüver2012; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016), such as expenses on lobbying staff or requesting a study. Second, groups have other resources, which will be defined as political capacities to which the literature has referred to in a number of ways. For the purpose of this paper, they are categorized as representation and mobilization capacity. Representation capacity is defined by a group’s ability to speak on behalf of its constituents (Daugbjerg et al., Reference Daugbjerg, Fraussen, Halpin, Xun, Howlett and Ramesh2018) or the public at large (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015: 99) as well as its close interactions with its members or general citizens. It also refers to the number of people who are represented by that organization as well as the knowledge of what the public thinks about an issue (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009) and a group’s ability to operate as a mediating organization that aggregates societal interests which are transmitted to the policymakers (Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Hanegraaff and Braun2017b). Mobilization capacity is defined as a group’s ability to obtain and sustain political support (Daugbjerg et al., Reference Daugbjerg, Fraussen, Halpin, Xun, Howlett and Ramesh2018) and encompasses the amount of public support a group can mobilize (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013; Fraussen and Beyers, Reference Fraussen and Beyers2016: 664). This requires communication skills, members, and support (Daugbjerg et al., Reference Daugbjerg, Fraussen, Halpin, Xun, Howlett and Ramesh2018), but not necessarily financial resources. The following section will elaborate on the underlying mechanisms of how economic resources and political capacities enable information provision, arguing that while economic resources may help with the provision of expert information, political capacities are more valuable for information on public preferences than economic resources.

A resource perspective on informational lobbying

First, economic resources allow an organization to hire staff with the necessary expertise or buy expertise for a specific issue (Schlozman and Tierney, Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986: 97; Drutman, Reference Drutman2015; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2016; Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016). Even if some – especially resourceful – organizations have (expensive) research units and in-house expertise for the overall policy area, they have to expand their portfolio and invest in research to gain information on the specificities of the issue in question. As an example, a government may want to discuss a new policy proposal regulating air quality by banning diesel cars in highly polluted areas. A car manufacturer has knowledge on fuel emissions of its cars but no evidence for the impact of auto exhaust fumes on humans. Having economic resources, the company could invest in air-pollution research conducted by external parties and use this information thereafter to provide it to policymakers. This illustrates how economic capacities allow an organization to expand its issue portfolio (Fraussen, Reference Fraussen2014) and to acquire more specific information. Undoubtedly, this type of information is difficult to access and costly to acquire. Resource-poorer groups that lack financial resources have a disadvantage in acquiring and ultimately transmitting such information in a credible manner.

However, political capacities do not necessarily require a large budget (cf. Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013) and can potentially be used to compensate lacking financial resources (Schlozman and Tierney, Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986; Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009). To understand how such capacities allow the acquisition of relevant information, it may help to think of interest groups as transmission belts. Interest groups are commonly described as intermediates between citizens and the policymaking level by organizing, aggregating, and transmitting public preferences (Truman, Reference Truman1951; Wright, Reference Wright1996; Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Carroll and Lowery2014; Eising and Spohr, Reference Eising and Spohr2017). Yet it requires certain organizational features to generate policy-relevant information and act efficiently as a transmission belt, and groups vary in their capacities to do so (Albareda, Reference Albareda2018; Albareda and Braun, Reference Albareda and Braun2018). The capacity to act as a transmission belt is thus, among other things, determined by how such groups organize their information flows, that is, how they interact with their members and supporters and how such information can be channelled to the policymaking level (ibid.). One important feature for acting as a transmission belt is therefore the capacity to accurately represent the interests of an organization’s constituents. Groups have to be responsive to their members and supporters to avoid risking that members leave the organization or withdraw their support, which would ultimately affect the group’s chance of survival. Hence, groups have to know what their constituents want and how they could benefit from a policy. The relationship between members, supporters, clients, and group leaders affects the information capacity of the organization as group leaders learn through interactions with members and supporters about their preferences (Schlozman and Tierney, Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986). This makes membership a resource which can help aggregate information (ibid.). Such interaction does not require a high budget but communication, which can take place via e-mail, newsletters, events, and social media. These interactions do not only help to generate information about what (parts of) the public want(s) but should also increase the likelihood of providing such information to policymakers, as members and supporters expect their group to use the available information, which can be used to pressure policymakers who care about electoral consequences.

A second important feature to act efficiently as a transmission belt is the ability to shift policies in a preferred direction (Albareda and Braun, Reference Albareda and Braun2018). While this requires a certain degree of professionalization and access that allow the transmission of information, groups can also rely on their mobilization capacity, which demonstrates legitimacy and may help to transmit public preferences to the policymaking level. Groups that rely on members and supporters are more likely to use their mobilization capacities to demonstrate their efforts and to satisfy their members (Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin1994). Such mobilization capacities require fewer financial resourcesFootnote 3 (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013: 664), but rather communication skills and members and supporters (Daugbjerg et al., Reference Daugbjerg, Fraussen, Halpin, Xun, Howlett and Ramesh2018). The ability to mobilize large crowds requires that groups have a loyal member and supporter base with whom they interact and whose preferences they know. A group would be unlikely to start a campaign without knowing how its members would react to it. The mobilization capacity allows group leaders to generate information about preferences (Austen-Smith and Wright, Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1992) and estimate effects and successes of grassroots campaigns (Wright, Reference Wright1996: 91). The ability to mobilize is also different from actual outside lobbying as it is about the knowledge of having the ability to mobilize, which can again be used to pressure policymakers (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). In sum, each type of resource has its advantage when providing either type of information, which results in the first two hypotheses.

H1: The effect of economic resources on the provision of expert information is stronger than the effect of political capacities. (Economic Resources Hypothesis)

H2: The effect of political capacities on the provision of information on public preferences is stronger than the effect of economic resources. (Political Capacities Hypothesis)

An alternative and competing hypothesis could argue that actors cannot use their political capacities as economic resources are key for providing information about public preferences. However, in order to judge whether one type of resource can compensate for the (potential) lack of the other it is necessary to consider the ability of groups to provide both types of information. Since policymakers usually demand both expert information and information on public preferences, interest groups should strive to offer a combination to meet these demands as this might increase their chance of lobbying success. Undoubtedly, a group may provide one type more than the other, but groups are generally able to provide a combination (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). However, groups with high economic resources may be able to also access information on public preferences, which allows for the provision of a combination of both types of information. Economic resources can be invested in polling the general public about their position on an issue or in an expensive media campaign, aimed at shaping public opinion. Especially groups that cannot make claims of broad appeal and that convey a message that is contested ‘will avoid free but potentially unflattering media coverage’ and invest in a campaign which they can control (Schlozman and Tierney, Reference Schlozman and Tierney1986: 171–172). Again, since resourceful groups can expand and adjust their portfolio, a larger budget can also help a group acquire information on public preferences, which results in a third hypothesis:

H3: Higher economic resources increase the likelihood of a group providing a combination of expert information and information on public preferences. (Persistence Hypothesis)

Research design

The model will be tested using data collected within the larger GovLis project (Rasmussen et al., Reference Rasmussen, Mäder and Reher2018). The dataset pools information on public opinion and interest group activity on 50 specific policy issues in five West European countries (Germany, Denmark, Sweden, the UK, and the Netherlands). Information provision can determine access to policymakers (Bouwen, Reference Bouwen2004; Tallberg et al., Reference Tallberg, Dellmuth, Agné and Duit2018), which is why the inclusion of different countries considers variation in the degree to which interest groups are involved in policymaking; the UK being a country in which the interest group system is characterized as pluralist while the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark experience moderate or strong degrees of corporatism (Siaroff, Reference Siaroff1999; Jahn, Reference Jahn2016).

While much of the research on informational lobbying has surveyed interest groups about general information provision in their lobbying activities (cf. Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2011; Klüver, Reference Klüver2012; Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016), this study applies a design which takes into account that information by advocates is typically provided on specific aspects of a proposal and not policymaking in general. While some interest organizations may mobilize to push general policy in a more right- or left-wing direction, most lobbying activities are targeted at specific policy proposals (Beyers et al., Reference Beyers, Dür, Marshall and Wonka2014; Berkhout et al., Reference Berkhout, Beyers, Braun, Hanegraaff and Lowery2017a). The 50 specific policy issues in the data were selected as a stratified random sample from issues that occurred in nationally representative public opinion polls. Each policy issue constitutes a concrete policy proposal, which suggests a change of the status quo. The 50 issues in the sample vary moreover with regard to salience, public support, and policy type as these aspects are likely to have an impact on lobbying activities and lobbying success. Issues in the sample concern, for example, the question whether to ban smoking in restaurants or to cut social benefits (see Online Appendix A for more information on the sampling and for a full list of the policy issues). It should be considered though that opinion polls are likely to be conducted on relatively salient policy issues. Hence, a sample based on issues that a pollster considered worth asking does not constitute a completely random sample of policy issues (Burstein, Reference Burstein2014). However, citizens should have at least somewhat informed opinions if interest groups are expected to transmit their preferences meaningfully (Gilens, Reference Gilens2012: 50–56). Moreover, the stratified sample ensures variation with regard to media saliency, which is always added as a control variable.

The final unit of analysis in this paper is an actor on an issue. Actors (or interest groups) are defined based on their observable, policy-related activities which follows a behavioural definition of interest groups (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009; Baroni et al., Reference Baroni, Carroll, Chalmers, Marquez and Rasmussen2014). Several steps were taken to identify the actors that mobilized on an issue. First, student assistants coded interest group statements on the specific policy issue in two major newspapersFootnote 4 in each country for a period of four years (Gilens, Reference Gilens2012) or until the policy changed. Second, interviews with civil servants that have worked on the issue during our observation period (82% response rate) helped to complete the list of advocates that have mobilized on the issues. Lastly, desk research of formal tools and interactions such as public hearings or consultations was conducted in order to identify more relevant actors. Although this triangulation may still have missed some actors, the interviews with civil servants should help ensure that actors who exclusively focused on less visible inside-lobbying strategies were also captured. From December 2016 through April 2017, an online survey was conducted with 1410 advocates identified as active on the specific issues. About 383 answered the questions regarding the variables relevant for the analysis in this paper (see Online Appendix B1 for full overview of response rates), which results in a response rate of 27%.

Dependent variables

Following De Bruycker (Reference De Bruycker2016), the paper distinguishes between expert information and information on public preferences which results in two dependent variables. Information provision was measured by inquiring how often, on a 1–5 scale, an actor has used certain arguments (Online Appendix B2 provides an overview of the exact survey questions). Expert Information consists of arguments referring to facts and scientific evidence, the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed policy, the economic impact for the country as well as the compatibility with existing legislation (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016: 601). The answer categories range from 1 to 5 with 1 meaning ‘never’ and 5 ‘very often’. The values for the different arguments were added and divided by the number of items so that the final dependent variable is ordinal and ranges from 1 to 5. Cronbach’s alpha for this variable is 0.74. Information on Public Preferences consists of arguments referring to public support on the issues (ibid.) as well as fairness and moral principles (Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016). The latter has been added to ensure that not only information about general public opinion is considered but also about how a policy will affect organizations and/or certain segments of society (Burstein, Reference Burstein2014; Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016). Again, the items were added and divided by two so that the final variable ranges from 1 to 5. Cronbach’s alpha for this variable is 0.77. In addition, the paper tests whether an actor provided a combination of two types of information and therefore provides a third dependent variable. The variable Combination is a binary variable and relies on the other two dependent variables. The variable takes a 0 if actors hardly provided any information at all or if an actor provided a lot of one type of information only, that is, when an actor scores lower than 3 on both types of information or either type of information. The variable assigns a 1 if an actor scores above 3 on both information on public preferences and expert information. Online Appendix C1 provides a full overview of all variables and their distributions.

Independent variables

The main independent variables are economic resources and political capacities. The variable Economic Resources follows the logic of material resources (cf. Klüver, Reference Klüver2012; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013). However, instead of asking for the general budget or staff of the organization, it asks about the extent to which the actor agrees with having spent economic resources on lobbying activities on that issue. The advantage is that this measures resources that have been devoted to lobbying on the issue and not the financial or personnel capacity of an organization in general. This is an ordinal variable ranging from 1 to 5 with 5 indicating strong agreement. The variable Political Capacities is measured with four different survey items, which capture both the representation and mobilization capacity. Two items ask about how important it was to the actor to interact with members or relevant stakeholders on the specific issue, and about the importance of representing the public on the issue. This operationalization follows research that argues that political capacities refer to the legitimacy and representativeness a group can provide (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009; Fraussen and Beyers, Reference Fraussen and Beyers2016; Daugbjerg et al., Reference Daugbjerg, Fraussen, Halpin, Xun, Howlett and Ramesh2018). Arguably, the question is more about the importance, rather than a group’s actual capacity. The measure therefore implies that actors who considered a certain tactic as important on the specific issue also used it. While this measure is certainly not ideal, it allows for empirically approaching political capacities such as representativeness and legitimacy. Two other items ask about the extent to which an actor had public support and media attention on an issue (again, see Online Appendix B2 for exact survey questions). This operationalization follows research that argues that political capacities refer to the ability to mobilize citizens and volunteers (Kollman, Reference Kollman1998; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013: 664; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014; Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015: 99). This ability is likely to cause a lot of visibility, which will result in higher media attention and news reports. All questions range from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating strong agreement or high importance. The four measures were added and divided by four so that the final variable ranges from 1 to 5. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale is 0.62. To ensure that the relationship between political resources and information provision is not in fact a relationship between the outside activities of a group and information provision the analysis will control for that. Online Appendix C2 provides a correlation matrix, which shows that economic resources are correlated with political capacities representation at 0.37, which suggests that these resources are in fact different.

Control variables

The analyses control for the type of actor providing information as this might influence both the resources that an actor has and the type of information that is provided. The variable Interest Group Type follows the categorization of the INTERARENA project (Binderkrantz et al., Reference Binderkrantz, Christiansen and Pedersen2015) with the addition of firms and experts since these actors are similarly likely to provide information to policymakers (see Online Appendix D for an overview of the different actor types).Footnote 5 The category citizen groups includes public interest groups as well as hobby and identity groups, thus groups that represent a collective good, rely on members, organize campaigns, and typically have limited financial resources (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016). Second, trade unions and occupational groups are membership organizations which can interact a lot with their members and rely on their hands-on expertise while at the same time have a fair amount of financial resources due to membership fees (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013: 663; Rasmussen, Reference Rasmussen2015: 277). The third category includes firms and business associations, thus groups that do not rely on individual members, avoid outside activities, and are likely to be endowed with financial resources and market power (Klüver, Reference Klüver2011: 5; Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013: 663). Lastly, individual experts, think tanks, and institutional associations are assumed to be less endowed with material resources than business groups but more than citizen groups as their strength is their in-house expertise and research they can provide.

The analysis furthermore includes a control variable for Media Saliency as advocates may be more likely to provide information on public preferences on highly salient issues, whereas expert information may be more likely on less salient issues. Saliency is measured by the log of the average number of newspaper articles containing a statement on the issue per day based on the two newspapers that were used for the coding. Moreover, a variable that reports the Policy Type is included which distinguishes between redistributive, distributive, and regulatory issues (Lowi, Reference Lowi1964). Whereas expert information may be more likely on regulatory issues, information on public preferences may be more likely on redistributive issues which are likely to cause more conflicts (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013: 665). Third, a variable controlling for Outside Activities is included in the analysis to rule out that the relationship between political capacities and information provision is in fact a relationship between outside activity and informationFootnote 6 (Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2013; Hanegraaff et al., Reference Hanegraaff, Beyers and De Bruycker2016). The variable is based on two items, each of them surveying advocates about how important they considered activities such as protest or other activities mobilizing the public, or targeting the press for their work on the issue. All items were asked on a five-point scale and were added and divided by the number of items. Arguably, this variable could also be interpreted as a measure of mobilization capacity. However, it measures actual activity, whereas the mobilization capacity variables measures resources the actors could rely on.

Another variable controls for the Organizational Salience, that is how important an actor considered the issue in question compared to other issues. The importance an actor attributed to an issue may both affect the amount and the type of information provided and the amount of resources invested. If an issue is not a priority for an organization, the amount of information provided can be expected to be considerably lower compared to an issue that is high on the organizational agenda. Similarly, it could be assumed that organizational salience affects the amount of resources that are spent on collecting information, that is, that an organization is willing to spend much more resources if a topic is of high importance compared to issues that are less relevant. This variable ranges from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating that the issue was much more important compared to the average issue an organization is working on. Lastly, a control for the Position of an actor has been included as some argue that actors lobby differently depending on their position on the issue (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009; Burstein, Reference Burstein2014). As such, it has been argued that those aiming to challenge the status quo need to invest more to convince policymakers to risk unforeseeable consequences (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Berry, Hojnacki, Leech and Kimball2009), which could influence the amount as well as the type of information provided. Positions were coded while identifying the actors and thus rely on manual coding based on media statements, official documents, and expert opinion.Footnote 7 If an actor’s position was missing or coded as neutral, the self-reported position based on the survey was added. Again, a full overview of all variables can be found in Online Appendix C.

Analysis

Before turning to the regression analyses, the following section will briefly explore the distribution of the main variables. Overall, actors tend to provide more expert information (mean of 3.5) than information on public preferences (mean of 3.1). Furthermore, a majority of the actors provide a combination of both types of information (60%). A visual inspection illustrates (see Online Appendix E) that economic resources as well as political capacities are positively associated with either type of information. It shows that each type of resource could compensate for the (potential) lack of the other as each resource shows a positive effect on either type of information. The following part turns to the multivariate regression analyses to test the hypotheses. All analyses are run as multilevel models with random intercepts for policy issues to account for the heterogeneity of different issues and fixed effects for countries to control for unobserved differences across countries. Since the dependent variables to test hypothesis 1 and 2 are ordinal, multilevel ordered logistic regression models are employed as displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. Multilevel ordered logistic regression models with random intercepts for policy issues and standard errors in parenthesesa

+P<0.10, * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001

a VIF scores range from 1.19 to 3.03, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a problem.

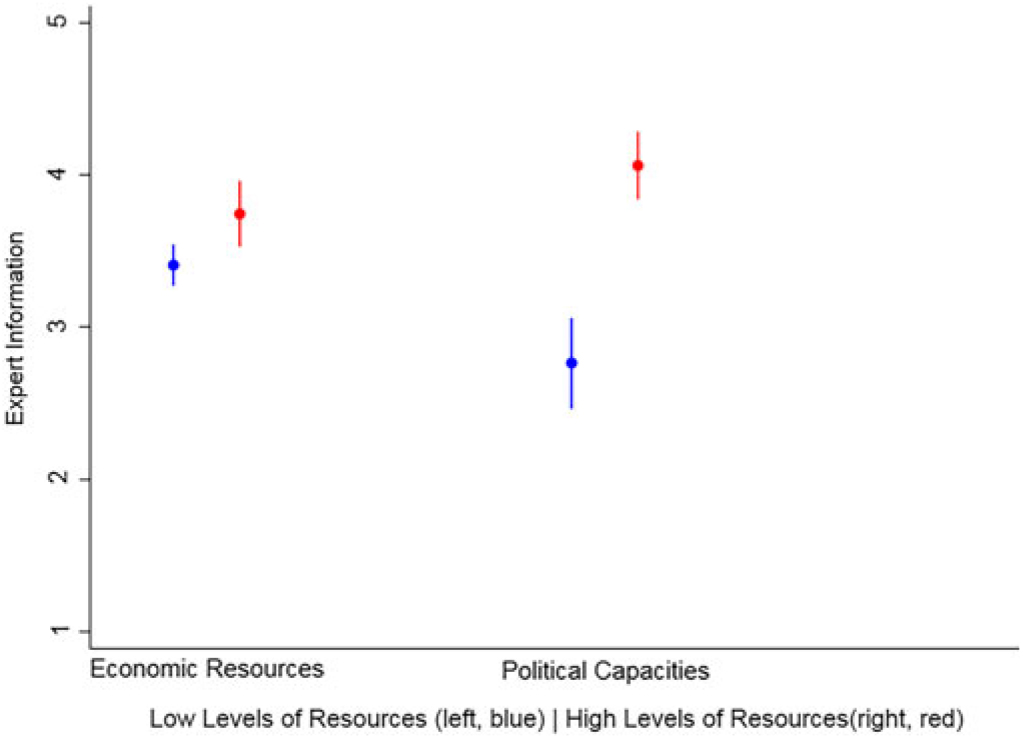

Hypothesis 1 predicts that higher economic resources result in a higher level of provided expert information. Model 1 does indeed show a positive and significant effect for economic resources (P<0.001). Model 2 adds actor and issue level controls. Although the effect size decreases and the significance drops from P<0.001 to P<0.05, the main effect remains. In line with hypothesis 1, the results show a positive association between economic resources and the provision of expert information. However, Model 2 shows that a group’s political capacities are valuable as well (P<0.001). The magnitude of the coefficients indicates that the effect of political capacities on the provision of expert information is even stronger than of economic resources, which is also supported by Figure 1.Footnote 8 The figure shows the effect of each type of resource on expert information, comparing the effects from low levels to high levels of either type of resource. While both economic resources and political capacities show a significant increase from low (blue, left) to high (red, right) levels, the increase for low to high levels of political capacities is somewhat steeper. This suggests that groups without economic resources can gather and provide expert information by relying on their political capacities. In fact, an additional analysis (not shown) run on a sample excluding actors that score 3 or higher on economic resources shows strong and significant (P<0.001) effects for political capacities. Hence, actors with no or low levels of economic resources can make use of their political capacities and still provide expert information.Footnote 9

Figure 1. (Colour online) Predicted amount of expert information for low (blue, left) and high (red, right) levels of resources with 95% confidence intervals.

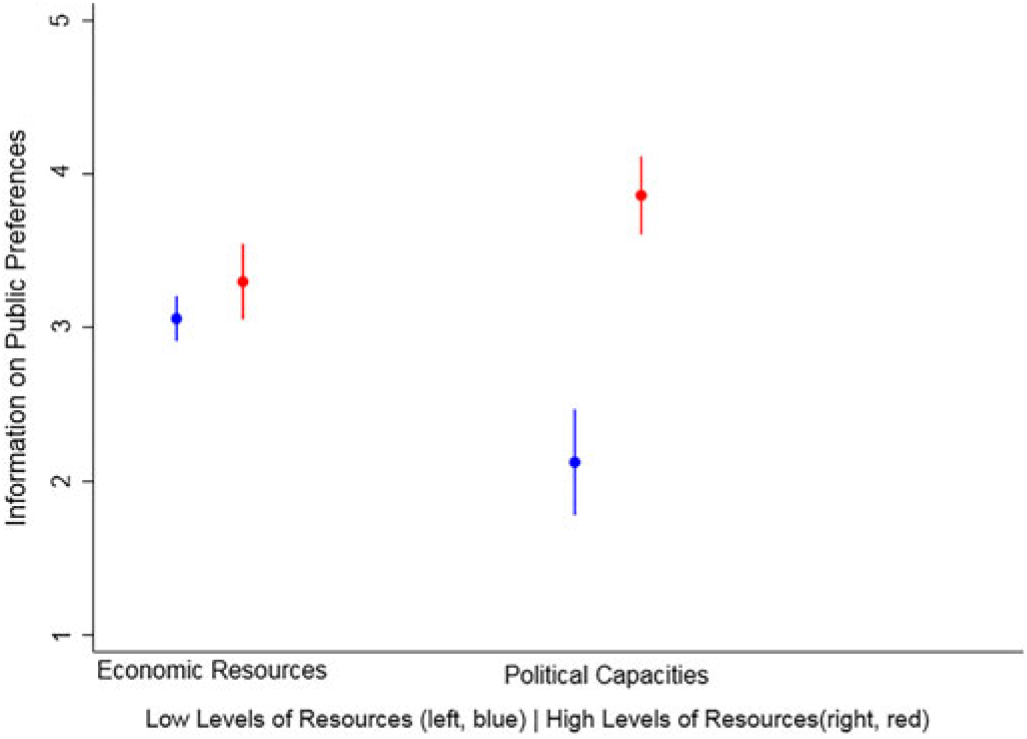

Models 3 and 4 test hypothesis 2, that is, whether an actor’s political capacities are related to the provision of information about public preferences, the idea being that groups learn through interactions with members and constituents about their preferences. Model 3 shows a significant and positive effect for political capacities (P<0.001) as well as economic resources (P<0.05). However, adding actor and issue-level controls in Model 4, the effect for economic resources decreases and the significance drops to P<0.1, while the effect for political capacities stays significant (P<0.001). Figure 2 illustrates that the increase from low (blue, left) to high (red, right) levels of economic resources is marginal, while higher levels of political capacities are associated with more information on public preferences. Hence in line with hypothesis 2, the analysis shows a positive relationship between an actor’s political capacities and the level of provided information about public preferences.

Figure 2. (Colour online) Predicted amount of information on public preferences for low (blue, left) and high (red, right) levels of resources with 95% confidence intervals.

With regard to the added control variables, Model 2 shows that the different types of actors do not differ from citizen groups with regard to the amount of expert information they provide. Only experts are more likely to provide expert information compared to citizen groups (P<0.01), which does not come as a surprise. According to Model 4, business groups provide significantly less information on public preferences than citizen groups (P<0.01). Thus, those that typically have more interactions with members and the public, that is, citizen groups, are more likely to provide information on public preferences. Running the models without controlling for actor types reveals similar results, whereby the effect of economic resources on information on public preferences even fails to achieve significance at the 0.1 level (not shown). This demonstrates that it is more important what kind of resources a group has, irrespective of the type of organization. For both types of information the effect of outside activities is positive and highly significant (P<0.001). While the inclusion of this variable does not take away the effect of political capacities, it is an important independent factor. The correlation between Outside Activities and Political Capacities is quite high (0.63, see also Online Appendix C2); however, the VIF test suggests that correlation between the variables does not introduce problematic multicollinearity to the model. Nevertheless, the analysis has been run excluding the variable outside activities (see Online Appendix F). The effects for economic resources and political capacities on expert information remain unchanged (Model F1). However, the effect for economic resources on information about public preferences becomes significant at P<0.05 (instead of P<0.1), while the effect of political capacities stays the same (Model F2). This could suggest that economic resources are quite important for outside activities such as big campaigns and events, yet less so for acquiring more politicized information. Furthermore, the more an actor considers an issue to be relevant, the more expert information the actor provides (P<0.01). Surprisingly, more information on public preferences is provided on regulatory issues than on distributive issues (P<0.05). However, this could also be caused by the types of issues that made it into the sample, which is why this finding should be interpreted with caution. The same holds for the finding that information on public preferences is more likely in the Netherlands compared to Germany (P<0.05) and that expert information is more likely in the UK than in Germany (P<0.05).

The analyses only test for effects of two types of resources on, firstly, expert information and, secondly, information about public preferences. It does not allow for making any inferences as to whether one resource is more valuable for one type of information than the other type of information. That is, the analysis does not test whether economic resources are more important for expert information than for information about public preferences, nor whether political capacities have stronger effects on information about public preferences than on expert information. Online Appendix J provides an analysis of such an alternative way of approaching this question. It shows that political capacities are more important for information about public preferences than for expert information. Furthermore, economic resources are more important for expert information, yet the differences are not significant. While this additional analysis compares the effect for one resource across different types of information, the main hypotheses intend to compare the effect of two types of resources on either type of information.

Table 2 finally presents the models to test hypothesis 3, which argues that economic resources are likely to affect the provision of a combination of both types of information. Given that the dependent variable to test hypothesis 3 is binary, multilevel logistic regression analysis is employed.

Table 2. Multilevel logistic regression models with random intercepts for policy issues and standard errors in parentheses

+P<0.10, * P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001

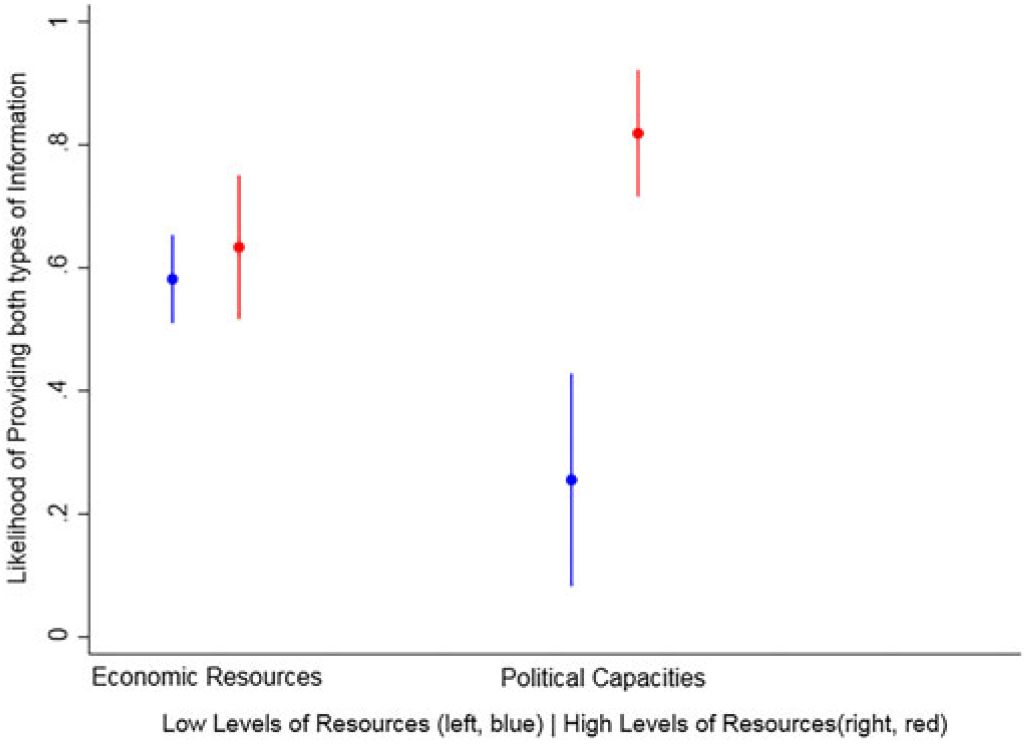

Model 5 shows the effects for providing a combination of information. Surprisingly, yet in line with the previous results, political capacities have a positive and significant effect on providing a combination of information (P<0.001), which does not change after adding actor and issue-level controls. Hence, contrary to what was expected in H3, economic resources have no effect and do not result in providing both types of information. In contrast, more political capacities allow for the provision of a combination of information as shown in Figure 3. The predicted probability of providing a combination of information types increases from 58% to 63% for the observed range of economic resources and from 26% to 82% across the observed range of political capacities.

Figure 3. (Colour online) Predicted probabilities of an actor providing a combination of information at low (blue, left) and high (red, right) levels of resources with 95% confidence intervals.

The control variables for these models show that citizen groups are more likely to provide a combination than business groups (P<0.05). Again, organizational salience and outside activities have a positive and significant effect on the provision of a combination (P<0.05 and P<0.001).

Summarizing the findings for the hypotheses, the paper shows that while economic resources are arguably valuable for information provision (cf. Klüver, Reference Klüver2012), it depends on the type of information and, moreover, that other resources are valuable as well. It confirms the argument by Dür and Mateo (Reference Dür and Mateo2013) on strategies: Not all interest group activity requires a high budget, and the interaction with members and supporters generates information and knowledge as well (ibid.). This also speaks to a line of research that looks more at the internal organization of groups and how they interact with their members. Groups that want to transmit the preferences of their members and constituents to policymakers have to be attentive to their members’ preferences (Albareda, Reference Albareda2018). This, however, requires certain organizational features that facilitate the alignment of preferences with members (Kohler-Koch, Reference Kohler-Koch2010) such as consultations, internal surveys, plenary discussions, meetings, and working groups (Albareda, Reference Albareda2018). These types of interactions allow group leaders to learn about their members’ preferences. Importantly, these interactions also allow groups to learn more about technical aspects of a policy proposal as many members may have hands-on experience (Wright, Reference Wright1996: 94).

This also supports the idea that political capacities may help compensating potentially lacking economic resources when providing expert information, which becomes even more obvious in the last model that considers when actors provide both types of information. The results for the effect of resources on providing both types of information show that it is not actors with economic resources that persist but that the knowledge and information gained through political capacities may help groups provide information. Moreover, the few differences across actor type suggest that the mechanism works via the resources a group has, irrespective of the type of group. This would also mean that group type cannot necessarily be used as a proxy for the types of information a group possesses (cf. Dür and Mateo, Reference Dür and Mateo2014) and explain why empirical studies have not found differences across group types with regard to expert information (De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016; Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016).

Robustness

The effects have also been tested with different model specifications. First, the ordinal models have been run as multilevel OLS regression models (see Online Appendix G). The effects for both resources on expert information stay the same. While the effect for political capacities on information on public preferences also stays the same, the significance for the effect of economic resources fails to reach significance (Model G2). As an alternative operationalization of economic resources, Online Appendix H provides models that use a logged version of an organization’s staff size on the issue. This variable was measured with a survey question asking about staff efforts in full-time equivalents that only received 226 answers. In line with the results, the effect for organizational staff is significant for expert information but not for information on public preferences or a combination of information. Moreover, in spite of the missing data the effects for political capacities on political and expert information are similar. Lastly, the two ordinal dependent variables have been recoded into binary variables (see Online Appendix I). Values above 3.5 were coded as 1, indicating that this type of information was provided often and values below were coded as 0, indicating that this information has rarely been provided. Again, the results show a positive and significant effect of economic resources and political capacities on expert information (Model I1), yet only a positive and significant effect for political resources and not economic resources in a model testing for the provision of information on public preferences (Model I2). In sum, the different analyses show robust results for the strong positive effect of political capacities on the provision of information on public preferences. Furthermore, there is evidence that economic resources increase the level of provided expert information. There is also quite robust evidence that political capacities are relevant for the provision of expert information. This could suggest that even when advocates have only low economic resources, they could draw on their political capacities and still provide expert information. Moreover, political resources are relevant for providing information on public preferences as well as a combination of information, rejecting the idea that economic resources are key for informational lobbying.

Conclusion

This paper started out to explore the resources that are necessary for an interest group to provide information to policymakers as it argued that information is not only a resource when lobbying policymakers, but requires resources in itself. While much of the academic literature has highlighted the importance of economic resources and the power of financially well-endowed groups, the paper argued that different information types may require different types of resources. The paper puts forward predictions arguing that political capacities are more important for information on public preferences than economic resources while economic resources are more relevant for expert information than political capacities. Furthermore, it hypothesized that financially well-endowed actors can use their financial resources to nevertheless access information on public preferences. The predictions were tested using a novel dataset on interest group activity on 50 specific policy issues in five West European countries.

The results show a positive relationship between economic resources and the provision of expert information as well as between political capacities and the provision of information on public preferences. Interestingly, the availability of political capacities also seems to enable groups to provide expert information. These findings suggest that groups can use political capacities to access expert information even if they do not have high levels of economic resources. This also explains why groups with political capacities are able to provide a combination of both types of information, which, ultimately, may allow more efficient lobbying through the provision of different types of information. A potential explanation is that groups do not only learn about preferences when they interact with their members and supporters but also gather policy relevant expert information (Wright, Reference Wright1996; Johansson and Lee, Reference Johansson and Lee2014; Albareda, Reference Albareda2018). Hence, close interactions with citizens and knowledge on public preferences seem to be valuable resources for an interest group that can be used for providing information to policymakers. Such interactions do not necessarily require a budget to be spent on hiring expertise or conducting a study but are relatively easily accessible.

Thus, even though the present study illustrates that information provision is costly (Austen-Smith and Wright, Reference Austen-Smith and Wright1992; Wright, Reference Wright1996), the costs vary and are not only of a financial nature which means that informational lobbying does not necessarily favour economically well-endowed groups (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960). Moreover, assuming that interest groups act as transmission belts by transmitting information to policymakers (Bevan and Rasmussen, Reference Bevan and Rasmussen2017; Eising and Spohr, Reference Eising and Spohr2017), the paper illustrates the ability of interest groups to work as a transmission belt, independent of the financial resources they have.

Arguably, there are limits as to how much one can generalize based on a sample of five West European countries and 50 policy issues. However, relying on issues that represent a broad range of topics and vary with regard to media salience, public support, and policy type should at least increase the likelihood of generalizability to a broader set of issues. It is important to bear in mind, though, that the issues in the sample may be more salient than an average issue given that they were sampled from opinion polls. This could mean that access to information – especially information on public preferences – may have been somewhat easier and therefore less costly than on less salient issues. A potential next step would be to look more closely at how organizations acquire their information and also when they do so to see how and whether this is determined by the issue context. Moreover, although the paper does not offer direct proof that the findings are generalizable to other countries, the theoretical mechanisms outlined in the paper should also apply to other European democracies. Nevertheless, a future contribution could look at informational lobbying in younger democracies in which interest groups may be less involved in policymaking. Another caveat is that the study only includes interest groups that have mobilized on the issue, which means these groups had some resources that allowed them to mobilize and provide information. This could suggest that the findings underestimate potential biases introduced by information transmission and the resources that are necessary to do so. Future research could analyse the internal information flows of an organization with a more qualitative approach to uncover the causal pathways of information. Lastly, the present study only sheds light on the supply side of information. Given that policymakers need both types of information and that interest groups should be more effective in lobbying if they provide a combination of information types, the findings indicate that at least with regard to the information they provide, it is not only those with a high budget that are able to inform policymakers. Yet we also know from the literature that interest groups predominantly provide expert information (Burstein, Reference Burstein2014; De Bruycker, Reference De Bruycker2016; Nownes and Newmark, Reference Nownes and Newmark2016). This may be because they consider this the most important and efficient type of information, in which case economically well-endowed groups are similarly well equipped. Future research could thus go one step further and test what type of information policymakers actually want and, ultimately, consider the most, that is, what type of information is most influential.

Author ORCIDs

Linda Flöthe, 0000-0003-1610-5993

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773919000055

Acknowledgements

The research received financial support from the Sapere Aude Grant 0602-02642B from the Danish Council for Independent Research and VIDI Grant 452-12-008 from the Dutch NWO. The author would like to thank Anne Rasmussen, Wiebke Marie Junk, Jeroen Romeijn, and Dimiter Toshkov for their valuable advice and support. The author is also very grateful for the extensive feedback from the participants of the workshop ‘The Citizens’ Voice’ at the ECPR Joint Sessions in Cyprus and the Politicologenetmaal 2018 in Leiden as well as from Adrià Albareda, Ellis Aizenberg, Moritz Müller, Patrick Statsch, and Jens van der Ploeg. Finally, the author wishes to thank several GovLis student assistants for their contributions to the data collection and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback.