Introduction

Over the past decade, the field of paediatric cardiology has increasingly recognised the value of mental health care for children, adolescents, and young adults with CHD and acquired heart diseases, as well as their caregivers. In 2022, the American Heart Association released the scientific statement, Psychological Outcomes and Interventions for Individuals with CHD, Reference Kovacs, Brouillette and Ibeziako1 which highlights a critical need for integrated and embedded mental health clinicians within paediatric cardiology care teams. The need for psychological screening, referral, and intervention has also been detailed in scientific and clinical practice guidelines specific to adult CHD care, Reference Stout, Daniels and Aboulhosn2 transition and transfer care in CHD, Reference John, Jackson and Moons3,Reference Sable, Foster and Uzark4 Fontan-palliated heart disease care, Reference Rychik, Atz and Celermajer5 and palliative care in paediatric heart disease. Reference Blume, Kirsch and Cousino6

Recent national prevalence rates indicate that approximately one in six children and adolescents in the United States experience a mental health disorder, with approximately half of these youth not receiving necessary mental health treatment. Reference Whitney and Peterson7 Children with CHD experience even greater risk of mental health concerns. In a comparative, cross-sectional analysis study, it was found that children with simple CHD had a five times greater odds of treatment or diagnosis of anxiety or depression than children without CHD, while those with single ventricle CHD had seven times greater odds compared to healthy peers. Reference Gonzalez, Kimbro and Cutitta8 It has been established that two-thirds of paediatric patients with single ventricle CHD will experience a mental health condition, such as depression or anxiety, in their lifetime. Reference DeMaso, Calderon and Taylor9,Reference McCormick, Wilde and Charpie10 Notably, CHD patients of minority race and those without insurance have lesser odds of mental health diagnoses and/or treatment when compared to non-Hispanic White peers, raising concern for racial and ethnic biases related to mental health diagnosis and treatment as well as disparities in access to mental health care due to insurance barriers. Reference Gonzalez, Kimbro and Cutitta8,Reference Gonzalez, Kimbro and Shabosky11

In an international study of over 1200 patients/caregivers with paediatric heart disease, 30% of respondents indicated a desire for more access to mental health/self-care information while nearly one in four stated a need for increased access to psychology/therapy services, as well as CHD peer support groups. Reference Cousino, Pasquali and Romano12 Among a sample of both mothers and fathers of children with CHD, integrated family-based psychosocial support within cardiac care settings was identified as a top need. Reference Driscoll, Christofferson and McWhorter13

Furthermore, there is robust evidence supporting the benefits of integrated mental health care in paediatric primary care settings (i.e. mental and behavioural health care via primary care services). Mental health care access has significantly increased for young people through integrated care models, and meta-analyses highlight significantly improved behavioural health outcomes for children and adolescents via integrated care models compared to usual care. Reference Yonek, Lee, Harrison, Mangurian and Tolou-Shams14,Reference Asarnow, Rozenman, Wiblin and Zeltzer15 Subspecialty integrated mental health care provides another venue for increasing mental health care access and improving outcomes for young people with cardiac conditions, particularly given high rates of mental health burden, strong patient/family interest in these services, and frequent touch-points with the cardiology subspecialty care team. In response to the scientific statements and, most importantly, the needs and voices of patients and families, our high-surgical volume centre formally established the University of Michigan Congenital Heart Center Psychosocial and Educational (M-COPE) Program in January 2020. This paper aims to detail programme development, resource needs and allocation, outcomes, challenges, and future directions to inform and support similar programme development across other centres.

Programme development

Pre M-COPE

Prior to 2020, psychosocial care for paediatric patients and their families cared for in our centre was provided across a number of divisions, departments, and units. A total of five social workers from two distinct health system departments provided care to patients and families across inpatient and outpatient settings. Four child life specialists were dedicated to the support of cardiac patients through the hospital-based Child and Family Life Services Programme. A 1.0 full-time equivalent outpatient heart centre education liaison was hired in 2019 to support school transitions, school-based accommodations and formalised services, and liaison with schools/teachers through partnership with Child and Family Life Services. Medical school psychology faculty from the Division of Paediatric Psychology within the Department of Paediatrics supported paediatric heart transplant (part-time full-time equivalent), cardiac neurodevelopment (part-time full-time equivalent), and inpatient consultation-liaison (hospital-wide) service lines. Other outpatient cardiac psychology referrals were accepted by paediatric psychology faculty and supervised post-doctoral psychology fellows when schedules allowed. Additional hospital-based services, such as child psychiatry consultation-liaison, neuropsychology services, supportive therapies (music, art, pet, technology), chaplaincy, and palliative care were also available through respective departments and divisions.

Prior to M-COPE launch, it was acknowledged that excellent psychosocial care was being provided in many areas of the heart centre; however, some patient groups had considerably higher access to psychosocial care than others. Furthermore, psychosocial care providers worked within their own silos and units. The shared goal for reaching more patients and families through team-based, heart centre-wide psychosocial leadership and programming was the impetus for launching the M-COPE Program.

M-COPE launch

In January 2020, the M-COPE Program was formally launched with dedicated 10% full-time equivalent for programme leadership supported by the heart centre. The M-COPE Program Director was invited to participate in heart centre subspecialty director leadership meetings, cardiology faculty meetings, and regular meetings with the philanthropy/development office. In the first year, three specific goals were outlined: (1) bring together a cohesive, multidisciplinary team of psychosocial clinicians and stakeholders across divisions, departments, and units to collaborate on the mission and strategic goals for psychosocial care across the heart centre in its entirety, (2) integrate the M-COPE Program and leadership into heart centre operations and missions, and (3) conduct a heart centre-wide needs assessment to understand strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats specific to psychosocial care across the heart centre.

Reporting structures for all psychosocial clinicians providing care in the heart centre, including psychology, neuropsychology, social work, child and family life, and education liaison remained the same. Regular M-COPE team meetings were established, as well as quarterly meetings between M-COPE Program Director, psychology, social work, and child life leadership. Prior to the M-COPE Program launch, there was no single point of contact for psychosocial care in the heart centre. For example, inpatient social work operations were largely managed through unit nursing leadership, while outpatient social work operations were directed through clinic administration. Through regular M-COPE team and psychosocial leadership meetings, communication and collaboration regarding psychosocial care across the heart centre were streamlined.

Needs assessment

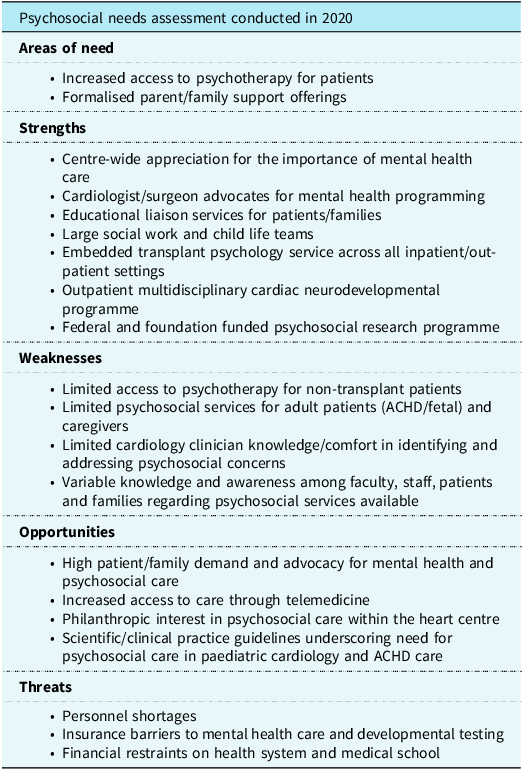

In the first year of M-COPE launch, an in-depth needs assessment was conducted. This included a total of 21 semi-structured individual and small group interviews with 30 unique heart centre psychosocial clinicians, clinic and unit medical directors, nursing and advanced practice practitioner leadership, surgical leadership, and heart centre administrative leadership. Areas of need, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to mental health care identified through the interviews are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Themes emerging from psychosocial needs assessment conducted in 2020 via group and individual semi-structured interviews among heart centre staff/faculty

In addition to heart centre-level interviews, population-specific needs were also gathered through IRB-approved survey studies with patients directly. Specifically, we surveyed youth with Fontan palliated CHD and youth with cardiac channelopathies. Among a sampling of 13 adolescents aged 13–18 years with Fontan-palliated CHD at our centre, 77% (10/13) believed access to cardiology-specific counselling/psychotherapy services would be helpful for them or their peers with CHD, while 45% expressed desire for embedded mental health care within the context of their cardiology clinic visits. The majority (62%) also stated that peer mentors with CHD would be helpful. Similarly, of the 21 patients aged 10–20 years with cardiac channelopathies surveyed at our centre, 30% believed access to cardiology-specific counselling/psychotherapy services would be helpful. Notably, 67% (14/21) of the sample were already receiving counselling services.

M-COPE mission

Informed by the multidisciplinary M-COPE team, heart centre leadership, and the needs assessment, the M-COPE mission was outlined and aimed to:

-

1. Increase access to psychosocial and mental health care for our patients and families.

-

2. Be a leading, nationally recognised programme for psychosocial research in paediatric cardiology.

-

3. Provide training to all learners in the psychosocial care of paediatric cardiology patients and families.

-

4. Collaborate, share, and advocate to enhance psychosocial and mental health care at our centre and beyond.

Current state of the M-COPE Program

Over the past five years, programmatic growth and initiatives aligned with this mission have been spearheaded across the heart centre. Importantly, areas of strength prior to M-COPE launch have continued as is. This includes the well-established Cardiac Neurodevelopmental Follow-Up Program, inpatient psychology/psychiatry consultation and liaison services, robust inpatient and outpatient social work and child life services, and outpatient education liaison services. The M-COPE team has expanded, along with the integration of services and new initiatives across the heart centre (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Team and clinical programme growth pre-post M-COPE.

M-COPE Aim 1—access to mental health care

Embedded clinic-based care

Psychology services have remained highly integrated within the heart transplant clinic and include an annual psychosocial screening programme and referral to transplant psychology outpatient services as indicated for additional follow-up. Additional embedded clinic-based psychology services have expanded through the development of the M-COPE Program, which includes a multidisciplinary single ventricle clinic, a transition clinic, and ad hoc consultation in adult CHD clinics. Within the single ventricle clinic setting, psychology team members are a standard of care during clinic visits, alongside multidisciplinary providers (e.g. cardiology, hepatology, nephrology, pulmonology, genetics). Psychology visits include brief psychological screening (i.e. mood, anxiety, attention) via patient and caregiver-report combined with clinical interviews aimed at guiding referral to additional supports as appropriate (e.g. cardiac neurodevelopmental evaluations, cardiology psychology services, school liaison). Within adult CHD clinic settings, psychology is available on an ad hoc basis, depending on clinic and provider availability. When available, the psychology provider receives a warm handoff to introduce services and completes a brief assessment to determine needs. This hybrid embedded model has resulted in a robust referral response for adult CHD mental health care.

Increasing access to psychotherapy

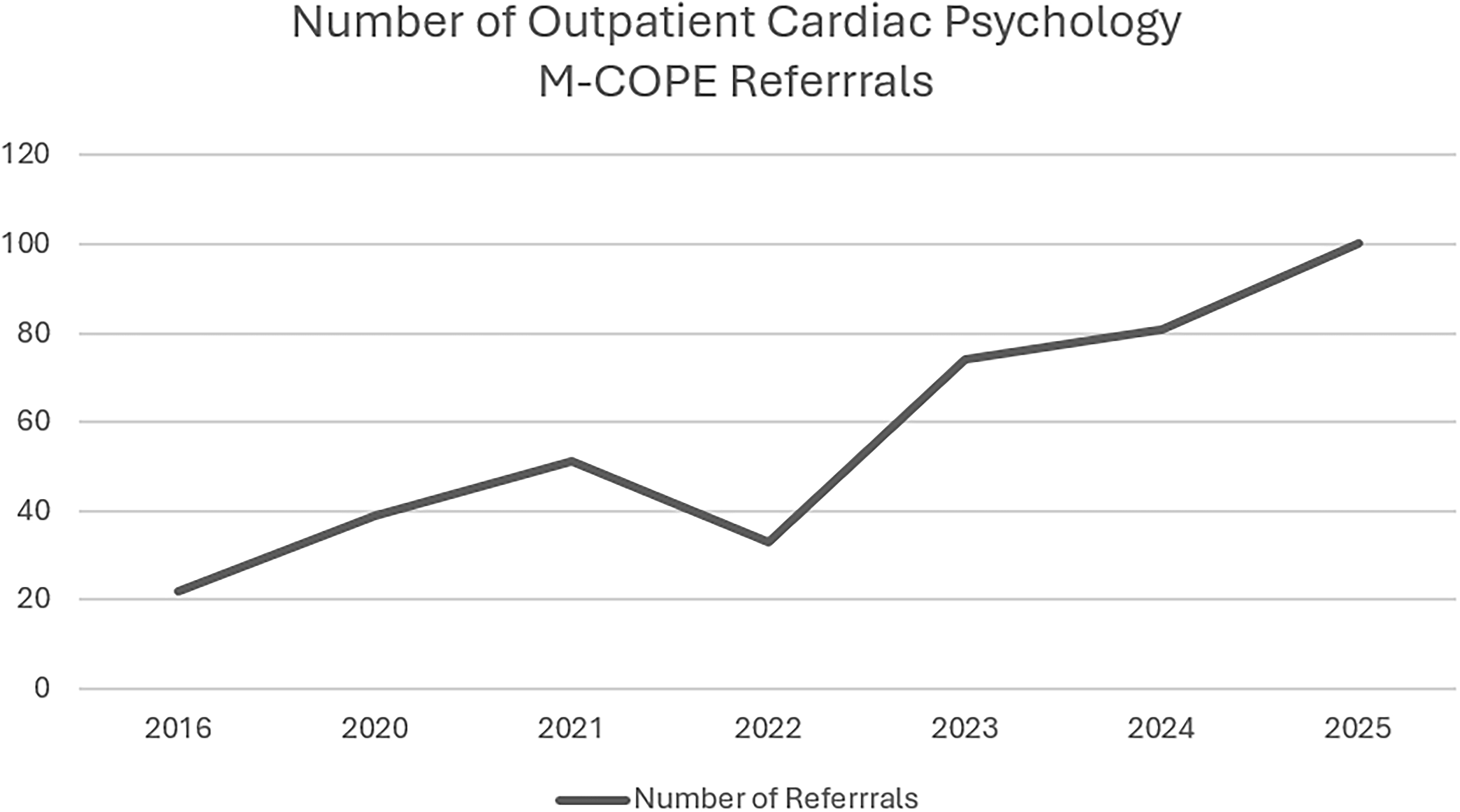

To increase access to psychotherapy heart centre-wide, two cardiac psychology fellowship positions were created, which increased the number of patients that could be seen and expanded psychotherapy services across the heart centre (see M-COPE Aim 3 section for description of fellowships). Additional cardiac psychology faculty full-time equivalent was then secured upon completion of these fellowship experiences. Overall, referral data have supported programmatic growth for heart-centre embedded psychotherapy services. For example, in 2016, prior to M-COPE launch, 22 new outpatient referrals were made for cardiac psychology psychotherapy services. Figure 2 shows the 2.5x increase in outpatient cardiac psychology referrals since the M-COPE launch in 2020. Notably, this only represents new outpatient referrals to psychology and does not account for patients first seen in the inpatient setting or those served via embedded clinic-based care by our psychology clinicians. This does not capture referrals to other M-COPE disciplines.

Figure 2. Outpatient cardiac psychology psychotherapy referrals since M-COPE launch.

In addition to the rise in referrals, data also support the model of heart-centre-based cardiac psychology care in terms of reaching patients and promoting mental health follow-up. For example, in year one, the adult CHD cardiology psychology fellow received 47 referrals for outpatient therapy among patients aged 18–33 years, with 30 (64%) of these referrals completing at least one outpatient cardiac psychology visit. Furthermore, patients are staying engaged in psychological treatment, with an average of five sessions per patient. This is a high rate of mental health follow-up compared to prior reports of mental health follow-up after referral among adult cardiac patients, ranging from 2 to 36% Reference Collopy, Cosh and Tully16 .

Presenting concerns for cardiac psychology psychotherapy referral have included: anxiety, depression, coping with diagnosis and/or changes in medical status, procedural distress, pre-surgical evaluations (i.e. transplant, ventricular assist device, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator), adherence, behavioural concerns, lifestyle modifications (i.e. sleep, physical activity), parenting stress, substance use, risk assessment, increasing independence in healthcare tasks, identifying life goals, family planning, and end-of-life care support. In addition, a formalised pathway for feeding-focused therapy for infants with heart disease was implemented through partnership with the Pediatric Interdisciplinary Feeding Program within the Division of Pediatric Psychology. Intervention is provided by both feeding psychology experts and a cardiology-dedicated registered dietician.

WE BEAT group programme

The WE BEAT Wellbeing Education Group Program is a group-based psychoeducation and coping skills intervention that was initially developed to meet the rising mental health needs of our patient population during and following the COVID-19 pandemic. The programme aims to improve psychological well-being and resilience among adolescents with CHD through a 5-week curriculum developed with patient and caregiver voices and an evidence-based resilience framework. Reference Cousino, Dusing and Rea17 Participants attend five weekly 45-minute telemedicine-based sessions providing introduction and in-session practice across the following wellness topics: (1) Well-being Education, Introduction and Community Building; (2) Breathe, Mindfulness, and Relaxation-Based Skills; (3) Energise, Positive Psychology Skills; (4) Adjust, Cognitive Skills Training; and (5) Thank, Gratitude. In addition to the psychoeducation provided, participants come together amidst a group of peers with similar diagnoses, addressing patient-and family-reported gaps for additional peer-to-peer support. Preliminary data support the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of the intervention among adolescents with Fontan-palliated CHD. Programme participants have reported increased resilience and decreased depressive symptoms. Reference Cousino, Rea and Dusing18 Future iterations of WE BEAT through the M-COPE Program are being expanded to other populations and age ranges, including adult CHD, adolescents with moderate or severely complex CHD, and heart transplant.

Novel clinical initiatives

Through establishing the M-COPE Program, various emerging, novel clinical initiatives have launched in partnership with colleagues across the heart centre. For example, via collaboration with nursing and sonography, our M-COPE psychology and child life team members have helped to launch a home-based echocardiography desensitisation initiative, which includes 3D-printed echo probes, gel packs, a social story, a game board, and step-by-step instructions for practising an echocardiography scan at home to reduce fears and distress. A psychosocial screening programme with a detailed family-based mental health plan is now being implemented for all infants in the interstage period prior to hospital discharge, with parent-focused mental health care being provided by our M-COPE team perinatal psychiatrist. In the coming months, a heart centre dedicated music therapy intern will be facilitating music groups for our early childhood inpatient population. Via the formally established M-COPE structure and leadership, individuals and teams from across the heart centre and beyond with innovative ideas to improve patient and family psychosocial care have been able to more readily implement initiatives such as these.

Peer support

The M-COPE peer mentoring programme is facilitated by our social work team and the hospital’s Office of Patient Experience. Hospital-trained peer mentors provide in-hospital and virtual peer mentoring services to both patients and families. The M-COPE Heart-to-Heart Caregiver Connection group was launched in 2020. Monthly virtual caregiver/parent meet-ups are facilitated by a parent peer mentor. The group regularly has ∼6–10 participants attending the monthly sessions. Over the past two years, through heart centre and philanthropic funding support, weekly caregiver coffee and/or pizza gatherings on our cardiology inpatient floors have been arranged and facilitated by our social work, child life, and peer mentoring teams.

M-COPE Aim 2—psychosocial research

Research and grant funding

Clinical research on the psychosocial aspects of paediatric heart disease is foundational to the M-COPE Program. In collaboration with the heart centre’s research core, the M-COPE team has led both small-scale, single-centre studies, as well as multi-centre clinical trials. Our research has been funded by small internal grants, as well as multi-million dollar federal and foundational grants. Examples of ongoing research projects led by our M-COPE team include: a federally funded multi-centre clinical trial of the WE BEAT Program in adolescent CHD, a society-funded qualitative methods crowd-sourcing study of the lived experiences of young people with CHD transitioning into adulthood, a multi-centre foundation and philanthropically-funded machine learning prospective study of physical and emotional health in Fontan palliated heart disease, and an institutionally funded pilot study of a patient-centred programme aiming to reduce procedural distress and need for sedation during echocardiograms.

In addition, the M-COPE team and leadership have supported the research efforts of colleagues and trainees across disciplines, including cardiology, nursing, and cardiac surgery, with scientific endeavours of their own that include psychosocial aims, measures, and/or outcomes. This has enabled colleagues across the heart centre to include psychosocially oriented aims and/or measures into their own projects with the mentorship and support of the M-COPE team’s expertise. Examples of cardiology-fellow-led projects include a study of disease-specific anxiety in paediatric heart transplantation, Reference McCormick, Schumacher and Zamberlan19 and an investigation of caregiver/patient educational needs in post-transplant care. Reference Goldart, McCormick and Lim20 Since launching the M-COPE Program in 2020, our M-COPE team has provided mentorship and scientific oversight to at least one cardiology fellow’s scholarly project annually. Via team-based science and mentoring across disciplines, this has resulted in tremendous research output and grant funding success related to psychosocial care in paediatric heart disease from our centre.

M-COPE Aim 3—psychosocial education

Cardiac psychology fellowship and internship rotations

Dedicated cardiology psychology fellowship and internship training experiences were developed to train the next generation of cardiology psychologists in supporting patients and families with heart conditions across the lifespan. Cardiology psychology fellowship training was tailored to the identified centre’s needs and fellows’ interests, which included training experiences across the lifespan. Two unique fellowship training experiences were developed: (1) early childhood and neurodevelopmental care and (2) transition and adult CHD cardiology care. Clinical activities specific to the early childhood and neurodevelopmental care-focused fellowship included a general cardiology outpatient psychotherapy clinic with a focus on early childhood populations, an outpatient infant/early childhood neurodevelopmental evaluation clinic, and training in best practices for infant/early childhood inpatient neurodevelopmental care (e.g. developmental rounds, feeding psychology, consult-based care). The transition and adult CHD-focused fellowship experience included an outpatient clinic for adolescents and young adults aged 18 to 30 years, solid organ transplant multidisciplinary transition clinic rotation, and inpatient consultation and liaison across both paediatric and adult cardiac care units. Given the potential for broader clinical intervention targets with the expanded age range of patients seen (e.g. family planning associated with parental CHD diagnoses, substance use), a co-supervision model was developed in which the transition/adult CHD-focused fellow received supervision from both a paediatric psychologist and an adult health psychologist. Both fellowships included general cardiology outpatient therapy caseloads, additional outpatient cases across other chronic illness conditions (i.e. oncology, kidney disease, cystic fibrosis), screening/evaluation in embedded cardiology clinics, and inpatient consultation, allowing for a breadth of training across settings, age ranges, and diagnoses. Both cardiac psychology fellows exceeded clinical billing targets during fellowship training years and transitioned into cardiac psychology faculty positions within the M-COPE Program, demonstrating a scalable model of programmatic growth through a training pathway.

M-COPE curriculum

The M-COPE Curriculum was co-designed by paediatric cardiology fellowship programme leadership and M-COPE Program leadership to provide mental health-specific education to paediatric cardiology fellows as well as heart centre faculty and staff. Approximately five M-COPE Curriculum lectures are held annually with a range of didactic topics and expert speakers. Topics have included: clinic-based screening/referral for mental health concerns, delirium management, psychopharmacological considerations in CHD, substance use in advanced heart disease, trauma-informed care, transition care, and more. This curriculum is now in its fourth year, and pre-and post-curriculum results have demonstrated improved cardiologist knowledge and comfort as it relates to psychosocial care. Reference McCormick, Owens and Lim21 A shareable slide deck of the M-COPE Curriculum for paediatric cardiology fellows has been created and made available to other heart centres with interest in this curriculum.

Patient-and family-focused education

Importantly, our needs assessment identified gaps in faculty, staff, and patient/family knowledge and awareness of the available psychosocial supports throughout the heart centre. As a result, quarterly M-COPE team presentations are now made at heart-centre-wide meetings to highlight programme offerings and detail referral pathways. Patient-and family-facing postcards, fliers, and a trifold pamphlet were developed. Webinars on specific topics (i.e. transition, school liaison services) are conducted to share additional information about M-COPE programming, as well as external psychosocial support offerings (i.e. national support groups, webinars), with our patients and families. M-COPE team members regularly participate in the heart centre’s Patient and Family Advisory Council monthly meetings for ongoing engagement with patients and families on our programmatic offerings and education materials.

M-COPE Aim 4—share and advocate

Over the past five years, we have worked closely with five other heart centres to date via onsite visits and follow-up meetings to support their centre’s psychosocial programme development. This has included meetings with their leadership and sharing of our own benchmarking data, financials, referral numbers, job descriptions, and more to support their own advocacy and strategic efforts. Our team has been actively engaged at the institutional, national, and international levels with approximately 5–15 presentations annually on psychosocial care in paediatric heart disease. In addition, team members contributed to scientific guidelines and key statements regarding psychosocial care in paediatric heart disease. At the local level, M-COPE team members have been regular presenters for a programme aimed at inspiring young people from lower-resourced communities to pursue careers in psychology and mental health care.

Discussion

Mental health is now recognised as a foundational component of paediatric and adult CHD heart care. There are many exemplary psychosocial and mental health-focused programmes embedded within heart centres throughout the United States and the World. This manuscript details our centre’s experience in expanding and building a robust psychosocial support and research programme within a high-volume paediatric heart centre. This programme has now grown to 20+ psychosocial clinicians with dedicated effort within our heart centre. Our M-COPE team members represent various disciplines, including social work, child life, psychology, neuropsychology, adult psychiatry, education/school liaison, music therapy, and patient/family advisors.

Factors critical to success

Throughout M-COPE development, a few key factors have been critical to our programme-building success. First and most importantly, integrated and embedded psychosocial care is highly valued by heart centre leaders, faculty, and staff. Psychosocial clinicians, regardless of their home department/division, are viewed as critical members of the heart centre team. The M-COPE Program director is co-located with cardiology and cardiac surgery offices. M-COPE team members across all disciplines are supported to attend and present at conferences, enabling their own career advancements. Heart centre resources, such as research coordination and support, administrative assistance, and philanthropy, have been made available to support M-COPE initiatives and growth. This partnership and integration within the heart centre at large also directly impacts patient/family uptake of services. Cardiology clinicians highly value the work of the psychosocial team, know the M-COPE team personally as teammates and partners, and regularly discuss psychosocial care as part of cardiac care in our heart centre.

Secondly, a strong partnership with the hospital’s development office has been key. Through the formalised launch of the M-COPE Program, opportunities for philanthropic gifting and support have been coordinated and shared with those interested. Notably, psychosocial support for patients and families is a tangible, visible, and meaningful way to give to the heart centre and those that we serve. Even smaller gifts have been utilised for a big impact through the M-COPE Program. For example, philanthropic gifts have been used to bolster the peer mentoring programme with funding for coffee/pizza hours, as well as a snack cart for peer mentoring hospital visits. Larger philanthropic gifts have been used to grow our M-COPE team with training fellowships, as well as dedicated time for faculty and staff hires.

Third, programmatic data tracking has been instrumental to M-COPE growth and advocacy. Key outcome metrics, including patient/family-focused outcomes (i.e. parent stress, satisfaction), as well as quality metrics (i.e. length of stay, time in clinic, referral follow-up) are captured for all M-COPE clinical initiatives. Importantly, outcome and quality metrics are uniquely captured, specific to the initiative or patient population of interest. For example, we have recently added a family psychosocial screening survey, the Psychosocial Assessment Tool, Reference Kazak, Schneider, Didonato and Pai22,Reference Kazak, Hwang and Chen23 to the pre-discharge process for our Interstage population. We are using this data to ensure appropriate home-based psychosocial supports are in place and to investigate the impact of this new programme on hospital re-admissions. Overall, programme-specific data are used to support continued philanthropic, research, and institutional endeavours.

Challenges and opportunities

Despite significant progress and expansion, the M-COPE Program has faced ongoing challenges related to the complex financial realities of delivering integrated psychosocial care in today’s healthcare climate. Billing and reimbursement for psychosocial and mental health services remain inconsistent, varying by discipline, insurance payor, and the nature of the interventions provided. This can make sustainable revenue generation challenging, as not all psychosocial services are billable, and reimbursement rates often do not fully reflect the time, expertise, and resources invested. At the same time, there are opportunities to diversify funding streams: our centre has leveraged philanthropic support and actively seeks grant funding to bridge financial gaps and enable programme growth. Cardiology clinicians, including cardiac surgery leadership, regularly utilise their resources to further bolster financial support for the psychosocial arms of our heart centre operations. As the healthcare landscape continues to evolve with increased recognition of mental health as critical to overall outcomes, there is potential for advocacy at institutional and policy levels to improve billing structures and pathways for revenue generation. Ongoing efforts to capture programmatic data and demonstrate the impact of psychosocial interventions are not only essential for quality improvement but also serve as valuable tools in justifying investment and securing alternative funding sources. Ultimately, aligning patient care value with sustainable economic models remains a central opportunity for advancing comprehensive heart centre psychosocial programmes. This advocacy will be most successful via a strong partnership between psychosocial clinicians, cardiac clinicians, hospital/institutional administration, and patient/family advocates.

Conclusions

In its first five years, the M-COPE Program has expanded access to care for patients/families in our centre by increasing the number of psychosocial clinicians, embedding psychology/perinatal psychiatry in select cardiology clinics, and developing novel modes of service delivery through collaborative efforts across our multidisciplinary psychosocial team and heart centre faculty/staff. The M-COPE Program has become foundational to our heart centre. Continued study of the programmatic offerings and impact will be ongoing with key metrics including referral patterns, patient/family outcomes, impact on health-related outcomes (i.e. length of stay, hospital readmission), and external referral generation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the entire M-COPE team, past and present, and those who have supported our mission, from philanthropic donors to hospital leadership, for their tremendous contributions to the M-COPE Program. We are most indebted to the patient and family voices who have been the catalysts for programme growth and support.

Author contributions

Drs. Cousino, Rea, and Dusing conceptualised and designed the study, collected data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Financial support

The needs assessment research reported in this manuscript received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation (Belmont Report) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and have been approved by the institutional committees at the University of Michigan Medical School IRB.