When the English Civil War began in 1642, London playhouses were closed down. A temporary parliamentary edict issued on 2 September 1642 proclaimed that ‘Publike Stage-playes’ were unbecoming in ‘the Seasons of Humiliation … too commonly expressing lascivious Mirth’.Footnote 1 By 1647, the ban on theatrical performance had become permanent. Yet this interdiction did not result in total suppression of dramatic activity during the Interregnum. Private performances, whether in houses or schools, continued to take place. More publicly, William Beeston tried but failed to re-establish Beeston’s Boys (a popular troupe consisting mainly of boy actors that performed from 1637 to 1642) at the Cockpit, but he succeeded in being granted title to what remained of the Salisbury Court Theatre in 1652. Meanwhile, playwrights such as Sir William Davenant circumvented the ban on stage plays by producing dramatic spectacles generically designated as ‘operas’ because they consisted of singing, declamation, and changeable scenery.Footnote 2 Indeed, Davenant gained approval from Oliver Cromwell’s government in the 1650s to produce ‘Heroick Representations’ – the most famous of which was The Siege of Rhodes (1656) – initially at his own residence Rutland House and later in the Cockpit theatre in Drury Lane.Footnote 3 Yet the formal ban on dramatic entertainment did mean that London’s public theatres could not officially reopen until 1660, when Charles II returned from his European exile and the monarchy was restored.

Shortly after assuming the throne, Charles II granted exclusive theatrical patents to his courtiers Thomas Killigrew and Sir William Davenant, establishing the theatrical duopoly controlled by the King’s Company (led by Killigrew) and the Duke’s Company (led by Davenant). The rival companies continued until 1682, when they were merged and became known as the United Company. Because theatres had been suppressed for eighteen years, few new plays were available to perform when commercial theatrical activity resumed in 1660. Necessity alone compelled the new patentees to stage the old stock drama from before the Civil War: principally, the works of Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, and Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher.

Comprised largely of veteran actors from before the closure of the theatres, the King’s Company regarded itself as the authentic successor to the pre-1642 King’s Men, the company in which Shakespeare had been sharer, playwright, and actor. On the basis of their claim for continuity in the theatrical profession, Killigrew’s company secured (or possessed by default) the rights to most of the plays earlier performed by the King’s Men, including twenty-two of Shakespeare’s plays deemed to be the most popular. The Duke’s Company, however, was made up of younger actors, including Thomas Betterton, destined to become the most important tragedian of his time. After petitioning Charles II for the right to reform or rework earlier plays, Davenant was granted rights to perform eleven plays, including nine by Shakespeare: Hamlet, Henry VIII, King Lear, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, Much Ado About Nothing, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, and Twelfth Night.Footnote 4

Initially, the two companies staged Shakespeare’s plays mostly unaltered. Othello, Henry IV, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and Hamlet were successful, but problems with other plays – especially the comedies – soon became apparent. Samuel Pepys, whose famous diary offers more eyewitness accounts of Restoration Shakespeare than any other source, noted on 1 March 1662 that Romeo and Juliet was ‘the play of itself the worst that ever I heard in my life’.Footnote 5 He was even more critical of an unrevised A Midsummer Night’s Dream which he saw on 29 September 1662: ‘I sent for some dinner … and then to the King’s Theatre, where we saw Midsummer’s Night’s Dream, which I had never seen before, nor shall ever again, for it is the most insipid ridiculous play that ever I saw in my life.’Footnote 6

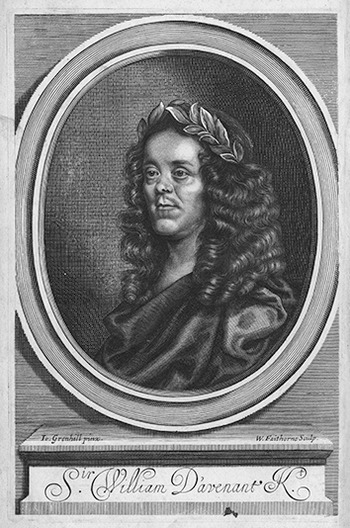

Figure 0.1 Sir William Davenant (1606–1668) by William Faithorne, after John Greenhill, published 1672

It did not take long for Davenant, whose portrait is shown in Figure 0.1, to realise that he could make a name for himself and his company by staging revised versions of Shakespeare. Under his bold and imaginative leadership, the Duke’s Company gained a reputation for staging Shakespeare’s plays with pioneering theatrical innovations. Davenant’s adaptations arose partly from necessity, because the plays given to the Duke’s Company were comparatively few in number and written in a manner deemed unsuited for the tastes of Restoration audiences. Davenant’s first adaptation, performed in 1662, was The Law against Lovers, based on Measure for Measure and Much Ado About Nothing.

When Pepys saw The Law against Lovers on 18 February 1662, he commented: ‘I went to the Opera [i.e., Davenant’s theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields], and saw The Law against Lovers, a good play and well performed, especially the Little Girle’s (whom I never saw act before) dancing and singing.’Footnote 7 One of the ‘Little Girle’s’ whose performance Pepys so admired was Mary (‘Moll’) Davis, a member of the Duke’s Company throughout the 1660s and known particularly for her skill as a singer and dancer. Mary Davis was not the first woman that Pepys saw on the stage, because actresses were part of Restoration theatre right from the start. Indeed, the appearance of professional actresses in England is one of the defining features of the Restoration stage. For the first time, Lady Macbeth, Juliet, Ophelia, Beatrice, and Isabella were played not by boys, but by women. Nor would there be any return to past theatrical conventions, because in 1662 Charles II had issued a royal patent banning boy actors from being cast in female roles. And so, the Restoration theatre produced the first generation of professional English actresses. In addition to Mary Davis, that inaugural generation also included, Nell Gwynn (who became mistress to Charles II) and Mary Saunderson (who married Thomas Betterton). The novelty of women appearing on the London stage, along with its unembarrassed potential for erotic allure, helps to explain in part how Shakespeare was adapted in the Restoration. In revising Macbeth, for example, Davenant substantially expanded the role of Lady Macduff, partly to create a virtuous counterpoint to the villainous Lady Macbeth and partly to provide good roles for the women in the Duke’s Company. Davenant’s and Dryden’s adaptation of The Tempest created more roles for actresses – Sycorax, Caliban’s sister; Dorinda, Miranda’s sister; and Milcha, Ariel’s companion – while the new character Hippolito was performed as a ‘breeches role’, a male character played by an actress and usually in costume that explicitly displayed her figure.

As implied by Davenant’s expansion and invention of dramatic characters, Restoration versions of Shakespeare often entailed strong rewritings of the original text, frequently with a new emphasis on the mixed genre of tragicomedy and musical and scenic divertissements. Some adaptations explicitly responded to the new political reality – a once deposed but now restored monarchy – by affirming royal power and denouncing regicide and rebellion in ways that sometimes effaced the moral ambiguities of Shakespeare’s precursor texts. Thus, most of Shakespeare’s history plays and Roman tragedies were converted into political commentaries. Given the close personal and legal connections between the stage and the crown, we cannot be surprised that the English Restoration theatre effectively operated as an extension of the court.

Other alterations to Shakespeare’s texts were dictated by changing literary and poetic style. Restoration dramatists and their audiences valued direct, unadorned language much more than figurative speech. Davenant’s Macbeth refers literally to the ‘last minute of recorded time’ rather than metaphorically to the ‘last syllable’. Symmetry in dramatic structure was prized more highly than the messy subplots found in many Shakespeare plays. Thus, Davenant and Dryden created the role of Hippolito (a man who had never seen a woman) in their version of The Tempest as a counterpart to Miranda (a woman who had never seen a man). Meanwhile, Nahum Tate endorsed the royalist ethos of the Restoration stage by ensuring that both a chastened Lear and his virtuous daughter Cordelia survive in his ‘happy ending’ version of King Lear.

In terms of the two most fundamental aspects of Shakespeare in performance – the acting and the text – the Restoration theatre did not perform Shakespeare’s plays the same way that Shakespeare’s own company had performed them only decades earlier. Restoration theatre artists did not view Shakespeare’s works as immutable dramatic masterpieces but believed that they needed to be reshaped and refined before they could be properly presented on the stage. Dryden’s prologue to his version of The Tempest lauds Shakespeare as the venerable ‘Root’ out of which the Restoration stage has freshly emerged: ‘As when a Tree’s cut down, the secret Root / Lives under ground, and thence new branches shoot; / So, from old Shakespeare’s honour’d dust, this day / Springs up and buds a new reviving Play.’Footnote 8

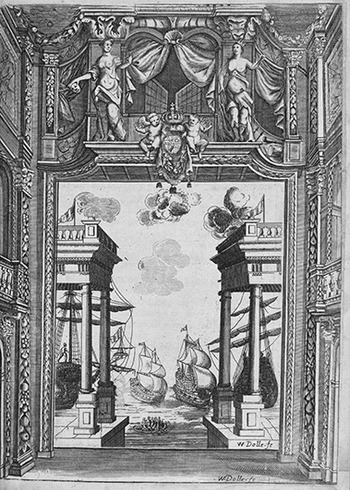

Changing theatrical tastes also meant changes in theatrical production. Because plays were now performed exclusively indoors (initially, in converted tennis courts) and because Charles II and his courtiers had grown accustomed during their exile on the continent to seeing elaborate movable scenery used in theatrical productions, the Restoration theatre was poised to make its mark through spectacle and scenic effects. Benefiting from Davenant’s work with Inigo Jones and his assistant John Webb on the final Stuart court masques performed at the Banqueting House, the Duke’s Company in the 1660s and 1670s exploited the theatre’s full potential for spectacular mise en scène, including movable painted scenery (see Figure 0.2). After the company’s move to the larger Dorset Garden Theatre in 1671, elaborate new machines enabled both people and objects to fly across the stage. The integration of music and dance with scenic and machine-based spectacle, practised previously only in court masques, was brought to the Restoration public stage with renewed vigour.

Figure 0.2 William Dolle, engraving of scenes at Dorset Garden Theatre, in Elkanah Settle’s The Empress of Morocco (1673)

Although the King’s Company eventually copied the elaborate staging introduced by their rivals, the Duke’s Company always remained more innovative. The eyewitness testimony of the spectator Samuel Pepys and the prompter John Downes offers a case in point. On 7 January 1667 Pepys saw a performance of Davenant’s adaptation of Macbeth, which expanded the roles of Macduff and Lady Macduff, introduced the new role of Duncan’s ghost, and ramped up the entertainment value with additional singing and dancing. Pepys praised Davenant’s version of Shakespeare’s tragedy as ‘a most excellent play in all respects, but especially in divertisement, though it be a deep tragedy; which is a strange perfection in a tragedy, it being most proper here and suitable’.Footnote 9 According to Pepys, the play’s divertissements – such as the witches’ comical and operatic performances – did not diminish the tragedy, but rather complemented it. Indeed, the spectacle was itself the ‘perfection’ of the tragedy, the culmination of its theatrical potential. John Downes, the long-serving prompter for the Duke’s Company, extolled the combination of visual spectacle with singing and dancing in his description of the lucrative revival of Davenant’s Macbeth (1673) at the new Dorset Garden Theatre:

[B]eing drest in all it’s Finery, as new Cloath’s, new Scenes, Machines, as flyings for the Witches; and with all the Singing and Dancing in it … it being all Excellently perform’d, being in the nature of an Opera, it Recompenc’d double the Expence; it proves still a lasting play.Footnote 10

Downes also served as prompter for Thomas Shadwell’s 1674 operatic version of Davenant and Dryden’s The Tempest, the most lavish and commercially successful production of Restoration Shakespeare. The opening stage direction, which seeks to represent the storm conjured up by Prospero, sets a high bar for multimedia performance spectacle: to the sound of a sizeable orchestral ensemble, ‘Several Spirits in horrid shapes fl[y] down amongst the Sailors, then rising and crossing in the Air.’Footnote 11 As with Macbeth, stage spectacle and box office income went hand in hand for this much revived and ‘all New’ version of The Tempest: ‘having all New in it; as Scenes, Machines … all things perform’d in it so Admirably well, that not any succeeding Opera got more Money’.Footnote 12 As musicologist Michael Burden rightly concludes, ‘scenes and machines were an intrinsic part of the nascent genre of dramatick opera’, a genre that includes some of the most vibrant, successful, and long-lived Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare.Footnote 13

Understanding Restoration Shakespeare

F. J. Furnivall’s 1892 variorum edition of The Tempest included in its appendix the full text of Shadwell’s 1674 revision of the Dryden–Davenant adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. As might be expected of the man who founded The New Shakspere Society, Furnivall included the famous Restoration version of The Tempest in his scholarly edition so that it might be despised all the more easily: ‘unless we read it, no imagination, derived from a mere description, can adequately depict its monstrosity’.Footnote 14 In so doing, he set the precedent for a century’s worth of literary scholarship that has felt free to dismiss Restoration Shakespeare as parasitic deformations of the superior original plays.

Furnivall’s condemnation also set narrow terms for future critical enquiry, defining Restoration Shakespeare as a purely literary object, more or less ignoring its life on the stage. As evident in G. C. D. Odell’s Shakespeare from Betterton to Irving (1920) and Montagu Summers’s Shakespeare Adaptations (1922), the result of this constrained perception was that scholars focused overwhelmingly on textual adaptation, explaining how Restoration versions deviated from their Shakespearean originals (e.g., in plot, structure, character, and imagery) and how those deviations could often be read as veiled pro-royalist commentary. Literary bias still operates in recent – and valuable – scholarship, including Sandra Clark’s 1997 edition of Restoration Shakespeare and Barbara Murray’s meticulous play-by-play analysis in Restoration Shakespeare: Viewing the Voice (2001).Footnote 15 While there have been important studies of the general performance aspects of Restoration drama, especially Peter Holland’s The Ornament of Action (1979), Jocelyn Powell’s Restoration Theatre Production (1984), and Timothy Keenan’s Restoration Staging, 1660–74 (2017), the core performance aspects of Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare have been systematically overlooked ever since scholars such as Judith Milhous documented their synthesis of script, song, and music.Footnote 16

Accordingly, a principal historiographical aim of this volume is to rebalance scholarship by interrogating how Restoration Shakespeare operated as a complex theatrical experience and not merely as a dramatic text, let alone a dramatic text presumed inferior to its precursor. Overturning the longstanding literary emphasis in scholarship, this volume constitutes the first edited collection that investigates Restoration Shakespeare from multiple material, critical, and performative perspectives. As such, it promises to increase our understanding of Restoration Shakespeare by investigating how the plays were – and continue to be – the basis for performances that integrate acting, singing, music, and dance within an overall dramatic narrative. The present volume does not seek to replicate previous studies of Restoration Shakespeare from the perspectives of textual revision, political context, or original staging conditions (including scenery).Footnote 17 Instead, all the contributors to this volume share a commitment to studying Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare not as relics of a theatrical past but as vehicles for performance that can transcend their printed texts and their original political and material staging conditions.

Performance as Research

The inspiration for this volume arises from the international research project ‘Performing Restoration Shakespeare’ – generously funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council in the United Kingdom between 2017 and 2020 – for which the editors of this volume were Principal Investigator (Schoch), Co-Investigator (Eubanks Winkler), and Research Fellow (Fretz). In partnership with the Folger Shakespeare Library and in collaboration with Shakespeare’s Globe, the project brought together scholars and practitioners in theatre and music to investigate how and why Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays succeeded in performance in their own time and how and why they can succeed in performance today.

This volume’s contributors are drawn from the research teams assembled for the project’s various scholarly and performance events, with each contributor having participated in at least one of the project’s core activities. The project’s first event was an open workshop on Shadwell’s operatic version of The Tempest (1674) held in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe (London, July 2017).Footnote 18 Throughout the week-long workshop, a research community of academics and artists reflected on and performed three scenes from the play that richly blend drama and music: the frightening ‘Masque of Devils’ (2.4), the charming duet ‘Go thy way’ between Ferdinand and Ariel (3.4), and the stately ‘Masque of Neptune’ (5.2). We learned a great deal in that inaugural workshop, not just about the performance aspects of Restoration Shakespeare but also, and equally importantly, about how to find a common language for scholars and artists in the rehearsal room.Footnote 19

Profiting from that initial experience, we then undertook a more ambitious task by partnering with the Folger Shakespeare Library, Folger Theatre, and the early modern music ensemble Folger Consort to mount a full professional production of Davenant’s Macbeth (c. 1664), with participating scholars actively contributing to the creative process throughout rehearsals. Directed by Robert Richmond, the production of Restoration Macbeth ran at the Folger Theatre in Washington, DC, from 6 to 23 September 2018.Footnote 20 Adopting a play-within-a-play concept, the production was set in St Mary Bethlehem Hospital (‘Bedlam’) in London, two weeks after the Great Fire of London in September 1666. Recalling Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade, the Bedlam inmates perform Davenant’s Macbeth and use the performance to murder the hospital’s warden (cast as Duncan in the play) and then to take over the institution where they had been held as virtual prisoners. Yet this framing device did not prevent the production from actively embracing the distinctive aspects of Davenant’s Macbeth, most especially the musical set pieces sung by the three witches, for which we used Amanda Eubanks Winkler’s edition of John Eccles’s late seventeenth-century score.Footnote 21 Reflecting the appeal that Restoration Shakespeare can have for audiences today, the entire run was sold out before the first preview performance.Footnote 22

Our project’s final public event took us back to the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, where we held a Restoration Shakespeare showcase in July 2019 for a mixed audience of the general public, theatre and music professionals, and scholars in Shakespeare studies, theatre history, and musicology. The showcase included reprised performances of the duet ‘Go thy way’ from the Dryden-Davenant version of The Tempest and two scenes from Davenant’s Macbeth, with Kate Eastwood Norris recreating her performance as Lady Macbeth from the 2018 Folger Theatre production. The afternoon concluded with a roundtable discussion on the challenges and rewards of performing Restoration Shakespeare today with Will Tosh from Shakespeare’s Globe and Robert Richmond and Robert Eisenstein, who were, respectively, stage director and music director for our production of Restoration Macbeth. Norris and Eisenstein are both contributors to this volume.

‘Performing Restoration Shakespeare’ is hardly the first research project that brings together academics and artists to study historical performance. In recent decades, scholars in Shakespeare studies and musicology have repeatedly collaborated with artists to recreate as best they can original performance styles or playing conditions. Within Shakespeare studies, such approaches – sometimes referred to as ‘Original Practices’ – are prominent in practice-based research and published scholarship that creates and reflects upon productions at Shakespeare’s Globe (including the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse) and the reconstructed Blackfriars Playhouse at the American Shakespeare Center. Many valuable insights have been gained from those pioneering efforts. Yet the historical authenticity paradigm underpinning such research has itself been challenged on historicist grounds: contemporary performance practice cannot forsake its own here-and-now reality to retrieve past experiences; the impulse to recover ‘original’ styles arises from modernist values about purity of artistic form; and original early modern performances were created through improvisations that by definition cannot be precisely recovered or even fully known.Footnote 23 Others argue that the claim of ‘restorative’ artistic practice to approximate composer or authorial intention is itself anti-theatrical, precisely because it denies performance its own hermeneutic agency, reducing it to a messenger on its creator’s behalf.Footnote 24

Mindful of these critiques, ‘Performing Restoration Shakespeare’ explicitly did not adopt the paradigm of ‘Original Practices’, nor did it make any claims whatsoever to historical authenticity. The very nature of Restoration Shakespeare reminds us that the vitality of theatre lies in innovation, not replication. Instead of reinstating what it presumed to be an authentic or authoritative version of Shakespeare’s plays, the English Restoration theatre – the first generation to do Shakespeare ‘after’ Shakespeare – changed absolutely everything: the script, the performers, the music, the mise en scène, the location and layout of the theatres, and the composition of the audience. And so our project, in its public performances of scenes from The Tempest and in its full production of Macbeth, has sought to turn the insights of performance studies back onto performance itself, enacting the principle that historical performance genres are intelligible only in a dialectical sense: that is, historical sources and scholarly expertise are not abandoned but transformed into new events for new audiences, with the past and present existing in creative tension.

This volume reflects two of the core principles of our research project on Restoration Shakespeare: first, that published scholarship and research-led theatre and music practice are complementary activities, each enriching the other; and second, that Restoration Shakespeare is best understood as a performance event that embraces and integrates drama, music, dance, and scenic spectacle, rather than simply as a dramatic text. Accordingly, the contributions to this volume take a multidisciplinary and a multi-modal approach, with contributions from theatre historians, musicologists and literary critics, as well as leading theatre and music practitioners. Far from reducing Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare to simply being topical versions of the original plays, the ten chapters in this volume attempt to do full justice to this distinctive but under-studied historical performance genre.

Collection Overview

Reflecting its interdisciplinary approach to studying Restoration Shakespeare, this volume is organised by methodology and materiality rather than by chronology, dramatic genre, or elements of performance practice. The first three chapters investigate some of the archival sources, intellectual contexts, and processes of revision that together reveal the distinctiveness of Restoration Shakespeare. Examining the transmission of Shakespeare’s songs into the Restoration period, Sarah Ledwidge argues that the popularity of music in Restoration Shakespeare can be partly explained by the hitherto unacknowledged circulation of Shakespeare’s songs in print and manuscript during the Interregnum. Situating Davenant’s adaptation of Macbeth within the broader context of his playmaking career, Stephen Watkins highlights the connections and discrepancies between Macbeth and the heroic operas and plays that Davenant himself wrote and produced in the 1650s and 1660s. In so doing, Watkins demonstrates how the dramaturgical alterations made to Macbeth conform to Davenant’s particular authorial style. Finally, Silas Wollston examines ‘The Rare Theatrical’ compositions of Matthew Locke, showing that many of them date from the same time as the Macbeth productions mounted by the Duke’s Company in 1664 and 1667. Wollston further contends that these compositions enable us to reconstruct Locke’s instrumental music for Macbeth, which encompassed the first and second music performed before the play commenced, a curtain tune, and act tunes.

Chapters 4 to 7 outline the enduring theatrical life of Restoration Shakespeare, beginning in the 1660s but extending (for some plays) into the nineteenth century. They also consider some of the performances created in recent years by the research project ‘Performing Restoration Shakespeare’ in partnership with the Folger Shakespeare Library. Fiona Ritchie explores how the Restoration convention of the ‘breeches role’ – a male character played by a female actor dressed in male attire – was influenced by the first appearances of professional women actors on the English stage in the early 1660s. Investigating the appeal of Restoration Shakespeare for later generations of actor-managers, James Harriman-Smith discusses how David Garrick used Nahum Tate’s King Lear – more than half a century after it was written – as an intermediary between himself and Shakespeare’s original play. Harriman-Smith’s chapter is followed by structured interviews with two performing artists, both of whom were involved in the 2018 Folger Theatre production of Davenant’s Macbeth. Louis Butelli, who played Duncan, reflects on the complexity of finding the right acting style for a contemporary performance of Restoration Shakespeare, the challenges posed to an actor by Davenant’s language, and the benefits of having scholars and artists working side by side. Robert Eisenstein draws on his experience as musical director for the Folger Consort to articulate the creative tension between musicians who are committed to historically informed practice and stage directors who are less motivated by historicist concerns. Reflecting on the challenges of staging historical performance genres today, he proposes a range of solutions to satisfy musicians, actors, directors, and audiences alike.

Following on from Eisenstein’s account of contemporary music and theatre performances, Chapters 8–10 reflect on how the scholar-artist collaborations in the research project ‘Performing Restoration Shakespeare’ can articulate a new model for the practice-based study of historical performance. In so doing, these concluding chapters seek to advance methodological debates in theatre studies and musicology by advocating an alternative to performance practices aimed at reviving ‘original’ styles or conventions. Collectively, they articulate a dialectical process that understands historical performances on their own artistic and contextual terms, but then uses that understanding to reanimate them for audiences today. Drawing on her observation of rehearsals for Macbeth at the Folger in 2018 and also on her later experience of devising scholar-artist workshops with actors from Lazarus Theatre in London, Sara Reimers explores the under-appreciated radical potential of Davenant’s Lady Macduff. Kate Eastwood Norris, who played Lady Macbeth in the Folger production, explains the logistical and creative parameters of her undertaking, details how she collaborated with the production’s scholarly team, and argues that the essential creativity of both scholarship and performance can help academics and artists to forge a productive alliance. In the final chapter, Amanda Eubanks Winkler and Richard Schoch offer a first-hand account of how scenes from the Shadwell-Dryden-Davenant adaptation of The Tempest were developed through scholar-artist collaboration and performed in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse in 2017. This practice-based experiment reveals how the present necessarily reconfigures the past, such that the performance of any historical work is inevitably shaped by present-day actualities, whether the bodies of the actors, the performance space itself, or the expectations of both artists and audiences.

As revealed by the content and focus of its various chapters, this volume has two main goals, one about scholarly substance and one about scholarly method. With respect to the substance of scholarship, we hope that this volume, the first devoted to Restoration Shakespeare in performance, will encourage scholars from multiple disciplines to discard any notion they might have that Restoration Shakespeare is at best an inferior form of dramatic poetry or at worst a deformation of Shakespeare’s theatrical genius. With respect to the methods of scholarship, we hope that our collective experience of working in a fully sustained way with actors and musicians on Restoration versions of The Tempest and Macbeth will encourage other scholars and other performing artists to take up this neglected but theatrically compelling repertoire to create yet further performances nourished by a dialogue between the archive and the rehearsal room, enriched by the union of scholarly creativity and artistic imagination.