To alienate conclusively, definitionally, from anyone on any theoretical ground the authority to describe and name their own sexual desire is a terribly consequential seizure. In this century, in which sexuality has been made expressive of the essence of both identity and knowledge, it may represent the most intimate violence possible.

In E. M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel, he mounts an extended, if somewhat beleaguered and even despairing defense of the genre: “The intensely, stifling human quality of the novel is not to be avoided; the novel is sogged with humanity; there is no escaping the uplift or the downpour, nor can they be kept out of criticism. We may hate humanity, but if it is exorcised or even purified the novel wilts; little is left but a bunch of words” (24). Forster distinguishes between “humanity” within and without the novel, between characters and novel readers: “They are people whose secret lives are visible or might be visible: we are people whose secret lives are invisible” (64). I begin this coda on Christopher Isherwood with E. M. Forster’s writings about the novel, not merely because Isherwood admired Forster immensely and discussed the possibilities of gay fiction with him regularly, but for the fact that The Memorial (1932) makes visible the “intensely, stifling human quality” of homosexual lives in postwar England – an endeavor that Forster’s own novel of gay life would only manage after Forster’s death in 1970.

Isherwood first read the manuscript of Maurice in 1933, although Forster had begun to work on the project two decades earlier, before the start of World War I. As Isherwood writes in his memoir Christopher and His Kind, “Almost every time they met, after this, they discussed the problem: how should Maurice end? That the ending should be a happy one was taken for granted; Forster had written the novel in order to affirm that such an ending is possible for homosexuals” (127). As I hope to demonstrate, the ending of Isherwood’s novel also shows “an affirming flame” – to borrow from another of his great friends, W.H. Auden – albeit one that arises in the midst of the alienating “intimate violence” of shell shock.1 Understood by many at the time to be the paradigmatic “self-inflicted” wound – a turning of the self upon the self – shell shock was also understood to be the sort of wound that particular kinds of men were more susceptible to than others. As W. R. Houston suggests in 1917, many cases of shell shock involve “tough-fibred but still imaginative men, whom the emotional shocks of the campaign, combined with fatigue and long strain, had been able to bring to a grand hysteria” (SM3). In keeping with Houston’s disparagement of “imaginative men,” sources from the wartime and postwar years refer often to the inherent weakness of “poetic types,” period shorthand, I contend, for homosexual soldiers.

Mary A. Ward’s Wildean figures discussed in Chapter 1 invoke scorn and abased disgust – they are the “molly-coddled” un-men who conscientiously object to the fighting. That she portrays them with all of the period markings of homosexuals merely adds to the stigmatized portrait. They don’t fight as men because they are not really men in the first place. In The Memorial, Isherwood radically contests such a pernicious and limited view by presenting to us Edward Blake, a combat veteran who comes through the fighting intact, at least on the outside: “he’d done marvels in the War, in the Air Force. He’d got the D.S.O. and the Military Cross. He’d even been once recommended for the V.C. He’d shot down lots of German machines. He was a hero” (158). But the decorations that Edward wears on his uniform, and the public recognition of his heroism, stand in uneasy relation to his broken interior and transgressive sexuality. For not only does Edward suffer from shell shock, he is also homosexual – an identity that only comes fully into focus in the novel’s latter stages. His homosexuality and his shell shock function as two sides of the same coin: stigmatizing, shameful, and in key ways unspeakable.

Returning briefly to Table 1 in Neuropsychiatry, we find “Constitutional psychopathic states” – a category broken up later in the study in the following manner: “Criminalism; Emotional instability; Inadequate personality; Nomadism; Paranoid; Pathological Liar; Sexual Psychopathy; Other forms (specify); Undiagnosed” (168). In the wartime and postwar era, “Sexual psychopathy” was understood to include homosexual relations, which The Report classifies as “sexual excesses” (95) and a “predisposing cause” of shell shock.2 As Edward struggles to live in the aftermath of the war, Isherwood addresses the very same question that my introduction identifies as central to any survivor’s postwar existence: “How are we ever to live?” In The Memorial, however, the question shifts ground to account for the invisible – and indeed illegal – “secret lives” of gay combat veterans. How to live as a gay male with shell shock in a closeted world that demands a “disguise”? What ending seems possible for Edward Blake and his kind?

Forster repeatedly addresses the difficulties and possibilities of endings for novels in Aspects. He caustically revolts against the “idiotic use of marriage as a finale” (38); he laments the fact that “Nearly all novels are feeble at the end” (95). In his chapter on plot, he asks, “Why need it close, as a play closes? Cannot it open out?” (96). Then, in the late chapter that explores the highest-order organisms of the novel form, “Pattern and Rhythm,” Forster once again returns to the problem of ending fictional works: “Expansion. That is the idea that the novelist must cling to. Not completion. Not rounding off but opening out” (169). My coda functions, I hope, as a Forsterian “opening out,” a way to end by suggesting additional expansions to the canon of shell-shock novels and modern cultural memories of the First World War. Isherwood’s novel looks at and remembers the wartime service and postwar survival of gay men – a consequential seizure of memorial terrain from a general populace committed to looking away and forgetting.

My analysis of Isherwood’s The Memorial pays particular attention to the novel’s ending, which itself “opens out” rather than closes. Isherwood’s novel concludes in a room with a view of Berlin in the year 1929. Eleven years beyond the Armistice, Edward Blake looks both backward and forward with a peace unimaginable one year earlier. In 1928, after wandering from the Tiergarten and among the statues lined along Sieges Allee, a blindly drunken Edward had been struck by the unexpectedness of his present position: “ten years ago I wasn’t allowed to come down this road. Now it’s allowed again. And in ten or twenty years’ time perhaps it won’t be allowed. How bloody queer. In 1919 we were going to have bombed Berlin” (54). After stumbling back to his hotel room, Edward considers his two suicide notes. He burns the one addressed to Margaret Lanwin, but keeps the other, which reads as follows:

Dear Eric,

At my Bank there is a small black metal box. Will you see that all the papers inside it are destroyed?

I am asking you to do this because you are the only person I can trust.

I am leaving you some cash for your funds. Spend it as you think best.

Edward.

Shortly after reviewing this note, he tries to kill himself. In a sense, the novel thus begins with an ending, albeit one that fails to materialize. For Edward Blake’s suicide attempt ends only in a wounding and his subsequent survival. But the note above poses numerous related mysteries that contribute to narrative tension across the remainder of the novel: Why burn the letter to Margaret? Why can he only trust Eric? What contents does his small black metal box hold? And why does Edward want them destroyed?

The nonlinear structure of the novel itself, which breaks apart into four discrete sections – 1928, 1920, 1925, and 1929 – emblematizes Edward’s fragmented postwar world and his shattered inability to pull himself together. In 1925, looking “iller than ever,” Edward admits that his shell shock troubles have gone on quite long enough: “Yes, the War’s getting to be a bit old as an excuse now, isn’t it?” (223). Everyone around Edward seems compelled to try to get him to forget the war, a dynamic that confirms critic Stan Smith’s astute recognition of the novel as an “exercise in counter-commemoration, wakening those memories a public culture would prefer forgotten” (288).3 While Smith focuses attention on The Memorial’s resistance to a process by which “the commemoration of the war dead becomes a recruiting agent for future wars” (285), I find in The Memorial’s forthright and “impure” attention to the humanity of a shell-shocked gay veteran a counter-memorial intent on making visible the suffering, solitude, and survival of a particular individual – and a particular kind of man – hitherto kept to the margins of World War I literary history.

Deferred Effects

Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press published The Memorial, Isherwood’s second novel, after the manuscript had been rejected by Jonathan Cape, the publisher of Isherwood’s first novel All the Conspirators (1928). The connection between Woolf and Isherwood seems all the more interesting in light of the fact that our contact with the story of Edward Blake begins precisely where Septimus Smith’s narrative ends in Mrs. Dalloway. Whereas Septimus famously leaps to his death in 1923, a suicide that Dr. Holmes pointedly describes in terms of cowardice, Edward botches his attempt to take his own life in 1928. Shame permeates the novel, and accrues about three interrelated nodes: the failed suicide attempt, the condition of shell shock, and Edward’s homosexuality. Isherwood’s novel refuses to acquiesce to the demands of a culture and people that send Septimus plunging down onto Mrs. Filmer’s area railings: “So he was deserted. The whole world was clamouring: Kill yourself, kill yourself for our sakes” (92). Edward Blake’s suicide scene has much in common with Woolf’s delivery of Septimus Smith’s death. Both men take the same methodical, rational approach to their respective deaths; both express the same consideration for others in the aftermath; both battle against the same weariness and fatigue; both men feel utterly deserted by humanity and alienated from the world. But, in Isherwood’s novel, Edward survives. Septimus plunges to his death, taking his treasure with him; Edward, meanwhile, lives on.

When he comes to consciousness, he realizes first that his “eyelids were sticky” (59). Like the residue of sticky blood that impairs his vision, Edward himself sticks around, an embodiment of the residual effects of the war on the shell shocked. “O Christ, thought Edward, I’ve mucked it” (59) – he repeats this again and again as he throws up, tries to move about, and works his way, eventually, to a mirror. The sight that he and we confront is both alarming and suggestive: “There was a smear of blood on his cheek and a stain running down from the corner of his mouth. And his mouth was pulled rather sideways. He looked as if he’d swallowed a dose of some nasty medicine” (60). The bullet that he attempts to swallow functions as a nasty cure for his condition: a way to bring an end forever to his pain, confusion, and loneliness.

Isherwood’s decision to stage a suicide attempt and the subsequent survival of the veteran involved offers up an intriguing extension of Woolf’s moving thesis concerning the shell shocked and their suffering. Maisie Johnson’s brief and random contact with the Smiths early in Mrs. Dalloway registers repeatedly her impression of them as odd outsiders: “Both seemed queer, Maisie Johnson thought. Everything seemed very queer” (26). Later, at Clarissa’s dinner party, Septimus’s doctor, Sir William Bradshaw, discusses with Richard Dalloway “some case” that has a bearing on a Bill concerned with the “deferred effects of shell shock” (183). We get no further details, but rather shift away to the indirect commentary of Lady Bradshaw: “just as we were starting, my husband was called up on the telephone, a very sad case. A young man (that is what Sir William is telling Mr. Dalloway) had killed himself. He had been in the army” (183). Septimus’s anguished death arrives at the party with the Bradshaws and quickly dissolves into hushed platitudes about legislative provisions. Though Clarissa herself feels the impact of Septimus’s death – feels that his death “was her disaster – her disgrace” (185) – the party rolls on about her, and Septimus, meanwhile, like a shilling thrown into the Serpentine, drops out of sight.

In Isherwood’s novel, quite conversely, his suicidal protagonist refuses – or is refused – any such disappearance. Edward Blake remains, right through to the novel’s final page, a distressing and disturbing center of attention. Isherwood examines closely the aftermath of shell shock’s wounds, as well as the manner in which veterans and civilians alike try to move on after the war. In Isherwood, however, the “cure” offered is complicated by the unspoken and unexplained aspects of Edward’s postwar life. For what is he doing in Berlin after the war? Why has he been seeing a psychiatrist? Is Edward in Berlin merely for help with his shell shock, or does he also seek a “cure” for his homosexuality?

In Tender Is the Night, a despairing aristocrat hires Dr. Diver to consult on the case of a homosexual son. For the father, his scion is a degenerate riddled with vice: “My son is corrupt. He was corrupt at Harrow, he was corrupt at King’s College, Cambridge. He’s incorrigibly corrupt. Now that there is this drinking it is more and more obvious how he is and there is continual scandal” (227). The father tells Dick about his efforts to convert his son from gay to straight using a variety of means, including trips to brothels and injections of “cantharides” (227). When such measures fail to stay the repeatedly “corrupt” behaviors of his son, Señor Pardo y Ciudad Real resorts to violence: “I made Francisco strip to the waist and lashed him with a whip” (227). The son, meanwhile, tells Dick that while he is “unhappy” with his life, he feels that nothing can be done about the situation: “It’s hopeless. At King’s I was known as the Queen of Chile” (228). On the one hand, Dick responds to the “courageous grace which this lost young man brought to a drab old story” (229); on the other hand, Dick continues to classify the “abnormality” of Francisco from the “pathological angle” (228). His homosexual acts seem to Dick to be “outrages” perpetrated, rather than human relations. Dick advises Francisco that any change to his behavior would only come about via repression and avoidance: “You’ll spend your life on it, and its consequences, and you won’t have time or energy for any other decent or social act. If you want to face the world you’ll have to begin by controlling your sensuality – and, first of all, the drinking that provokes it” (228).

Later, the father begs Dick to take his son on as a patient: “Can’t you cure my only son? I believe in you – you can take him with you, cure him” (231). Despite the forcefulness of the father’s pleadings, Dick refuses to help; however, the emphasis on the desire for a cure resonates with widespread cultural imperatives to view the homosexual subject as a diseased and corrupted entity, a subhuman in need of radical alteration and fixing. As Ward’s anathematized “conchies” in the wartime novels make clear, to be homosexual in a time of total warfare is to remain illegible and outside the pale. But how to function after war when troubled both by shell shock and by the heteronormative dictates of the culture at large?

The day previous to his suicide attempt, Edward reaches out to a well-regarded German doctor: “The psycho-analyst. Somebody had talked about him at a party at Mary’s. He was wonderful. The best man in Europe. Had had great success with cases of shell-shock. Edward had thought: Perhaps he could make me sleep. But, of course, it had been just like all the others. A darkened room. A man in cuffs. Questions about early childhood” (56–7). The fact that Edward seeks medical attention at all suggests the extent of his despair, as well as his internal resourcefulness. As we have seen in previous chapters, men such as Christopher Tietjens, Frederic Henry, and Aaron George – all suffering from traumas – do not find their ways to medical professionals. All Edward seems to desire is an ability to sleep – a rest from all that troubles him. However, the treatment that Edward encounters in the office once again echoes with the obtuse dismissiveness that Septimus confronts in both Holmes and Bradshaw. Edward’s doctor hopefully and confidently assesses matters: “a perfectly plain case” (57). Isherwood’s novel suggests, I argue, that survival beyond the war, for Edward, means more than a “perfectly plain” reckoning with how to put the dead and the past to rest. Edward’s postwar present – indeed his entire future – involves constant negotiating of the contested matter of how to conduct a legible life, how to enjoy an intelligible love, and how to find a permanent place in the memories of those who follow.

Living People Are Better than Dead Ones

In Isherwood’s autobiographical novel about his postwar growing-up and early novel-writing activities, Lions and Shadows: An Education in the Twenties (1938), he introduces us to “Lester,” a troubled veteran on a full pension whose condition of “nervousness” is certainly shell shock (253). He comes to consider Lester as “the ghost of the War” (257). Isherwood had lost his father in the war and had long struggled with his feelings and memories about the ghost in his own family. The Memorial, in fact, opens with a dedication to Frank Isherwood, who did not survive the war to share any stories about it with his son. It is Lester’s war stories – and postwar suffering – that seem to have had a lasting impact on Isherwood: “With his puzzled air of arrested boyishness, he belongs for ever, like an unhappy Peter Pan, to the nightmare Never-Never-Land of the War. He had no business here, alive, in post-war England. His place was elsewhere, was with the dead” (257). In fact, his contact with Lester provides part of the impulse to write a second novel: “The novel was to be called A War Memorial, The War Memorial, or perhaps simply The Memorial. It was to be about war: not the War itself, but the effect of the idea of ‘War’ on my generation” (296).

Isherwood’s father went missing with the York and Lancaster Regiment in Ypres in early May of 1915. Christopher Isherwood was eleven years old at the time. The diary entries of his mother, Kathleen Isherwood – which Isherwood published in 1971 as Kathleen and Frank – reveal the painful torments of weeks of waiting for news from the front of her husband’s fate: “May 22. No news. It seems an everlasting silence” (465). Visits to the war office, letters from commandants, and inquiries with officers yield no reliable information about Frank. After receiving numerous conflicting reports of Frank’s wounding and hospitalization, all of which turn out to be impossible to corroborate, Kathleen eventually comes to hope that he is in German hands: “It would be so terrible for him to be taken prisoner, and yet what else is there to hope for” (467).

His death in combat gets confirmed, however, on June 24, 1915, in a letter from the British Red Cross and Order of St. John. Weeks later, additional texts begin to arrive:

“September 8. In the paper today under ‘previously officially reported missing now unofficially reported killed’ is Frank’s name. I think I miss him more every day and life seems harder and harder”; “September 9. Telegram of condolence from the King and Queen”; “September 26. Unpacked My Dear’s things, unspeakably sad to see the dear familiar things and the green valise Bell and I made at Limerick, nearly everything has come back except his watch and a luminous torch”; “September 27. In the evening I received from the War Office the disc bearing my Husband’s name – very polished up and torn from its string. It didn’t seem real somehow”

Kathleen Isherwood’s intimate physical contact with the “dear familiar things” echoes with the return of Desmond Mannering’s personal effects in Ward’s Elizabeth’s Campaign. In Ward, a father spreads the contents out on the floor: “Desmond’s kit, his clothes, his few books, a stained uniform, a writing-case, with a few other miscellaneous things” (319). With his son deceased, Squire Mannering can be comforted only by the things his son once carried. Likewise, in Lee’s River George, Aaron’s mother takes hold of the bloodied “voodoo cha’m” that hangs about the neck of her lynched son. These remnants strike up intimate reconnections, while confirming at the same time the total absence of the men who will remain forever missing. The George family’s Jim Crow–era status as second-class citizens will all too likely result in private mourning matched by public obscurity. The grave of Aaron George will be legible and recognized only in the African American community. The Mannerings, meanwhile, can rely on the public memorializing functions of the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) to mark and salute their son’s death. Desmond Mannering’s place will be marked by an official place; his name etched in stone will be visible for all to see.

Isherwood notes that his father’s name was initially left off the Menin Gate – dedicated in Ypres on July 25, 1927 – and put on a different Flanders memorial. His mother protested, encountered bureaucratic resistance on the part of the IWGC, and railed about mismanagement. She eventually convinced the authorities to have his name added to the Menin Gate, which Isherwood skewers in a manner evoking Sassoon: “They had put Frank on the Ploegsteert list because he had belonged officially to the Second Battalion of the regiment. The fact that he had commanded the First Battalion and died on its battleground was seemingly of no significance to these bureaucrats! (And besides, the Menin Gate was the memorial to be on; who cared about unpronounceable Ploegsteert – these Flemish names were almost as hideous as German ones!)” (486; italics in original).

The sanctifying memorialization practices of the state emerge in Isherwood’s memoir and, especially, in The Memorial, less as comforts to the living than as self-serving obsessions with the dead. In order to pay homage to the memory of his best friend Richard Vernon, who had been killed in action, Edward Blake attends the 1920 dedication of a village Memorial Cross. The last time that Edward had seen him during the war, Richard gave Edward a gift: “He was busy knitting. He offered Edward a pair of mittens. And Edward had been wearing them when he crashed. They must have been cut off him at the hospital with his other clothes and thrown away or burnt. It was a pity, because he had nothing, absolutely nothing to remind him of Richard as he used to be, as he was when he died” (140). The Memorial Cross itself offers nothing – “absolutely nothing” – to Edward in the place of his friend; the hand-made mittens, cut away and destroyed, emblematize for Edward the measure of love lost and intimacy thrown away forever.

Richard’s widow, Lily, considers Edward’s oppressive appearance at the ceremony: “And he looked so tired and ill – no wonder, after the terrible things he’d been through in the War. After his flying accident, when for months, she’d heard, he’d been quite insane. Even now he’d a strange way of looking at you that was sometimes a little frightening. Lily felt glad that she hadn’t to entertain him at the Hall. But poor Edward Blake, she told herself, forcing down her dislike of his presence, how terribly he must have suffered” (100). She knows that Edward was in love with her husband; she knows that he has always hated her for marrying Richard. As they stand together – but apart – listening to the Bishop talk about “sacrifice,” “heroism,” and the “Inspiration” of the dead, the grief of Richard’s sister, Mary, meanwhile gives way to sardonic resentment: “she was very bored with this service. Why couldn’t they have had something much shorter? … All this cult of dead people is only snobbery. I’m afraid I believe that. So much so, that the attitude which we’re all subscribing to, at the moment seems to me not only false but, yes, actually wicked. Living people are better than dead ones. And we’ve got to get on with life” (112–3).

Physical memorials to the fallen fall under consistently scathing and irreverent attack in Isherwood’s novel. In the 1925 section, several college students steal a road-sign and attempt to haul it into their lodgings. Maurice, Mary’s son and the ringleader of the escapade, lost his father in the War; so too did his cousin Eric, the son of Richard Vernon. Too young to fight in the war, these young men nonetheless live always in its shadow. They struggle with their own lack of service, as well as with the ineradicable sacrifice of their fathers. Put differently, they struggle not with “the War itself, but the effect of the idea of ‘War’” (296). As Maurice and his friends drunkenly wrestle with the unwieldy sign, carelessly wrapped up in rugs, Eric asks them about what they are carrying. Maurice replies, “It’s the Unknown Warrior. Don’t tell the Vice-Chancellor, will you, lovey?” (198). Even more precious to collective British memories of the war than the Cenotaph, the Unknown Warrior memorial resonates in almost all period accounts with solemnity, reverence, and unwavering respect. Even Woolf’s representation of Westminster Abbey, where Miss Kilman takes shelter in Mrs. Dalloway, grudgingly acknowledges the centrality of the memorial in British consciousness: “New worshippers came in from the street to replace the strollers, and still, as people gazed round and shuffled past the tomb of the Unknown Warrior, still she barred her eyes with her fingers and tried in this double darkness, for the light in the Abbey was bodiless, to aspire above the vanities, the desires, the commodities, to rid herself both of hatred and of love” (133–4). But where Woolf depicts a constant stream of “new worshippers” shuffling slowly and reverentially past the Abbey memorial, Isherwood offers only an uprooted and unreadable sign, covered in carpets, and ignominiously likened to the most sacred of anonymous bodies.

Without Disguise

In Christopher and His Kind, Isherwood lightly recalls the reception of his novel in 1932: “I remember how one reviewer remarked that he had at first thought the novel contained a disproportionately large number of homosexual characters but had decided, on further reflection, that there were a lot more homosexuals about, nowadays” (89). If the sexuality of Maurice and Eric remains something of an “unreadable” open secret throughout the novel, Isherwood eventually removes the veil entirely from Edward Blake, who has for many years been involved in a complicated relationship with Margaret Lanwin. They are treated by friends at parties as a “married pair” (268), they live together at home and abroad for great stretches of time, and they constantly split up and reunite. Along the way, and in between Edward’s documented relationships with various men, he and Margaret joke about and then actually try to have sex: “I might cure you,” Margaret suggests to Edward. Although the episode is a comedic failure – “quite hopeless” (269) – a current of despair, especially on Margaret’s part, nonetheless courses through it: “I sometimes wonder if all this is workable. The way we live” (273).

By the close of the novel, Edward has clearly abandoned the unworkable way that he and Margaret live. We find him in Berlin during Christmas 1929. This time around, he is not in a hotel room on a mission to kill himself, but rather in a flat that he has rented. The shift in lodging suggests, I argue, a permanent move and substantial change in mindset on Edward’s part. He seems no longer in search of a “cure,” either for his shell shock or his homosexuality; rather, he peacefully gazes out on the city that he now calls home: “Edward sat at the table by the window of his room, overlooking the trees and the black canal and the trams clanging round the great cold fountain in the Lützowplatz” (289). As Edward next turns to notes from Margaret and Eric, Isherwood offers also a reverse parallelism involving letters in both scenes. Where once he composed suicide notes and sought to hide away and destroy his past, he now reads letters from those who care about him – and who accept and love him without qualification. In Margaret’s letter, which we read in full, she discusses how she tells Mary “without disguise” all about Edward: “I remarked: You know what Edward is, and she agreed that we all knew what you were” (289). In the case of Septimus Smith, his suffering becomes intelligible only upon his death – and then only to the witness of his helpless widow: “Rezia ran to the window, she saw; she understood” (149). In contrast, Edward’s friends see and understand him for what he is and has always been.

In The Trauma Question, Roger Luckhurst echoes neatly back to Cathy Caruth’s mid-1990s characterization of traumatic memory as a radical disruption to expected continuities: “Trauma is a piercing or breach of a border that puts inside and outside into a strange communication. Trauma violently opens passageways between systems that were once discrete, making unforeseen connections that distress or confound” (3). Margaret’s letter to Edward, reiterated in the novel’s final pages, puts into writing the previously unspoken and yet utterly human nature of his sexuality. Her words, much like the novel itself, stand as a shocking “piercing or breach of a border.” Hitherto inside the closet, this “strange communication” reveals the walls to have been made of glass all along. Everyone who matters to Edward knows “what Edward is”; everyone has always known. And they agree that this does not matter; that is, they accept his homosexuality as an intrinsic part of his human makeup. They write to him and he takes the time to read the letters. The correspondence links him to others, but also helps him to feel that he has a place in the world, that he “corresponds.” Like messages exchanged between the Just of Auden’s poem, Isherwood reminds us by his novel’s end that Edward, too, “composed like them / Of Eros and of dust,” has an open passageway toward the future. Edward expects to continue.4

In the novel’s final pages, a young German arrives at Edward’s hotel room and asks about Edward’s scar. Edward tells the truth about his suicide attempt, but Franz doesn’t believe him; he insists that it must have happened in the War – and Edward agrees: “Yes, if you like” (294). Franz states that the War “must have been terrible” and, again, Edward agrees: “It was awful” (294). Franz grabs Edward by the throat and mock-kills him; then, he turns serious, and the novel ends: “that War … it ought never to have happened” (294). The exchange between these men suggests a host of possibilities, including their status as both friends and lovers. They seem comfortable around each other; their interactions seem at once casual and tense, innocent and yet intimate. What will the future yield up for them?

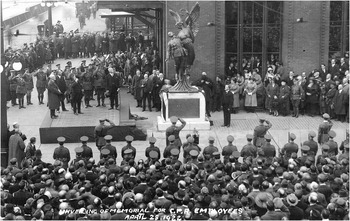

A curiosity in the room shared by Edward and Franz suggests possibilities. For perched atop the stove we find “a metal angel holding a wreath” (289). A mere Christmas decoration, perhaps, the metal angel nonetheless also functions as a telling memorial figure. In contrast to the “metal box” that holds and hides away Edward’s secret papers at the bank, the metal angel holds out a wreath. Angels holding wreaths mark the iconography of World War I memorials of many combatant countries. For instance, copies of Coeur de Lion’s “Angel of Victory” (Figure C.1) mark the memorial landscapes of Vancouver, Winnipeg, and Montreal. These magnificent bronze statues – dedicated in 1922 to the 1,115 employees of the Canadian Pacific Railway who died in the war – depict an angel ascending with the body of a deceased infantryman. In her left hand, the angel holds aloft a wreath, which might be taken for a crown or halo. These significant public monuments, much like the state sponsored memorials that specifically mark Isherwood’s writing – the local Memorial Cross, Westminster Abbey’s Unknown Warrior, the Menin Gate in Ypres – starkly contrast with the miniature scale and private, domestic setting of The Memorial’s closing scene. But what does the metal angel in Edward’s flat “offer”?

Figure C.1 Dedication Ceremony of Canadian Pacific Railway Memorial, “The Angel of Victory,” April 28, 1922, Vancouver, Canada. Image Number: AM54-S4-: Mon P100.

The metal angel keeps watch and waits until Edward has company – and then watches more. Sanctifying the humanity of the homosexual pair, this memorial totem keeps the War in the present but also holds it at bay; a talisman akin to Frederic Henry’s St. Anthony, except that here it does not go missing. The wreath-holding metal angel offers a visibly redemptive ending to an otherwise impossible and illegible life back in England. Like the wreaths left anonymously on the steps of the Chattri Memorial, like the wreaths carried by German veterans in Tender Is the Night, Isherwood places his wreath here in Berlin, in the company of men who remember and who must be remembered.

For compared with Septimus, who looks out the open window and jumps to his death, Edward offers up a survivorship account. He opens the window, looks down, and hears a human voice – a male voice. It is Franz. And what does Edward do? He drops him down the key. In the place of a body falling, we have a device that will open up the door – a welcome and an invitation. A device that will unlock the room that Edward is in; he will not be alone, he will share human contact. In Mrs. Dalloway, it is the predatory Dr. Holmes who charges up the stairs to “heal” Septimus, and who eventually forces him out the window. Here, in Isherwood’s formulation, a friend, a lover arrives and the wounds of the past – the scarred and sticky residue of the war, his suicide attempt, and his shell shock – register momentarily on the page only to fall away again in the presence of human love and possibility. Edward finds at last a place for the truths of his normal heart. To borrow further from Auden, Isherwood’s great friend and colleague, shell shock novelists “undo the folded lie” of trauma, foster understanding by way of remembrance, and insist upon our transition from “the conservative dark / Into the ethical life” (79; 67–8). Christopher and his kind – including Ward, Ford, Hemingway, Lee, Anand, and Fitzgerald – document and do battle with shell shock, and leave behind an illuminating army of novels well worth remembering.