Introduction

Training programmes in the research and teaching industry (RTI) primarily focus and rely upon technical competencies to improve animal welfare outcomes (Clifford et al. Reference Clifford, Melfi, Bogdanske, Johnson, Kehler and Baran2013; Weichbrod et al. Reference Weichbrod, Thompson and Norton2018). While training in technical competencies can improve knowledge-based outcomes (Howard & Gyger Reference Howard and Gyger2024), training can also be used to shift attitudes and elicit human behaviour change (HBC) to improve human-animal interactions (HAI) and animal welfare outcomes (Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Coleman and Barnett1994, Reference Hemsworth, Coleman, Barnett, Borg and Dowling2002; Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Hemsworth, Hay and Cox2000; Hemsworth Reference Hemsworth2003; Ellingsen et al. Reference Ellingsen, Coleman, Lund and Mejdell2014; Rushen & Passillé Reference Rushen and de Passillé2015; Learmonth Reference Learmonth2020). The link between HAI, HBC, and animal welfare outcomes has been acknowledged in animal welfare assessment frameworks (Rushen & Passillé Reference Rushen and de Passillé2015; Dunston-Clarke et al. Reference Dunston-Clarke, Willis, Fleming, Barnes, Miller and Collins2020; Mellor et al. Reference Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones and Wilkins2020) and animal welfare schemes (Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Barnett and Coleman2009; Dunston-Clarke et al. Reference Dunston-Clarke, Willis, Fleming, Barnes, Miller and Collins2020). Training programmes targeting attitudes extend beyond imparting knowledge and aim to support human behaviour change and improved decision-making. The few international, commercially available programmes focused on training for knowledge and changing attitudes to create behaviour change are primarily found in the livestock industries via Prohand® (dairy and pork) (Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Rea, Hall, Sawyer and Hemsworth2001; Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Coleman, Barnett, Borg and Dowling2002) and Temple Grandin’s slaughterhouse indicators and training programme (Grandin Reference Grandin2020, Reference Grandin2022). Both programmes focus on and incorporate aspects of training targeting key attitudes related to human-animal interactions with Prohand® designed specifically for augmenting HBC for better animal welfare (Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Rea, Hall, Sawyer and Hemsworth2001; Wilhelmsson et al. Reference Wilhelmsson, Hemsworth, Andersson, Yngvesson, Hemsworth and Hultgren2024).

There is some research available in the livestock (Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Coleman and Barnett1994, Reference Hemsworth, Coleman, Barnett, Borg and Dowling2002; Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Hemsworth, Hay and Cox2000; Coleman & Hemsworth Reference Coleman and Hemsworth2014; Wilhelmsson et al. Reference Wilhelmsson, Hemsworth, Andersson, Yngvesson, Hemsworth and Hultgren2024) and companion animal industries (McDonald & Clements Reference McDonald and Clements2019) regarding the benefits of training for attitudes in adults (Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Hemsworth, Hay and Cox2000; Hazel et al. Reference Hazel, O’Dwyer and Ryan2015; Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Sherwen and Coleman2018). The use of this technique appears to be implemented in some of the available primary and secondary school programme resources developed by Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA 2019) Victoria, Australia. While technical training is undertaken in the animal care and use industries (Hewson Reference Hewson2005; Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Frye, Lord, Baysinger and Edwards-Callaway2019), few programmes are designed specifically to address training targeting attitudes to change specific behaviours to promote better animal welfare outcomes. There is sparse peer-reviewed literature on the effects and/or impacts of training for attitudes in RTI teaching (Franco & Olsson Reference Franco and Olsson2014; Gaafar & Fahmy Reference Gaafar and Fahmy2018; LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020). The few studies available have explored the use of training for attitudes in rat (Rattus norvegicus) tickling (LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020) and tunnel handling of rodents with some overall positive impacts on reducing animal stress, improving animal welfare, and increasing uptake of these methods (LaFollette Reference LaFollette2020). The same studies also investigated potential differences between real-time online and face-to-face training methods and found minimal differences in training outcomes (LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020). Others have studied attitudinal and other training to embed institutional ‘Culture of Care’ programmes to improve animal care, welfare, and the 3Rs (replacement, reduction, refinement) (Franco & Olsson Reference Franco and Olsson2014; Gaafar & Fahmy Reference Gaafar and Fahmy2018; Greenough & Mazhary Reference Greenough and Mazhary2021).

Similar to other places around the world (e.g. UK, European Union [EU]) (Gyger et al. Reference Gyger, Berdoy, Dontas, Kolf-Clauw, Santos and Sjöquist2019; UK Home Office 2023), those working with animals in the Australian RTI are expected to be trained and competent in the 3Rs, animal welfare/care, legal responsibilities, and procedures involving the use of animals. However, unlike other jurisdictions such as the EU (Gyger et al. Reference Gyger, Berdoy, Dontas, Kolf-Clauw, Santos and Sjöquist2019) and the UK (UK Home Office 2023), a formal accredited or standardised training programme in the care and use of animals for scientific purposes is not nationally required nor provided in Australia. There is limited information on appropriate training content, ideal requirements, and best practice guidance for training programmes in Australia (Musk et al. Reference Musk, France and Rhodes2023). Adding to the complexity of this identified gap, the disparate nature of the Australian legislative system across each state and territory requires additional individualised content (Morton & Whittaker Reference Morton and Whittaker2022; Musk et al. Reference Musk, France and Rhodes2023).

A critical aspect and often legal requirement of maintaining good welfare and research outcomes is the identification and alleviation of pain in research animals. To alleviate pain, it is necessary to be able to reliably and accurately identify painful states. The use of validated pain scales is an important technique in identifying pain and determining if pain relief is effective (Cohen & Beths Reference Cohen and Beths2020; Mota-Rojas et al. Reference Mota-Rojas, Olmos-Hernández, Verduzco-Mendoza, Hernández, Martínez-Burnes and Whittaker2020; Evangelista et al. Reference Evangelista, Monteiro and Steagall2022). Grimace scales (GS) are one type of pain scale that have been validated across a wide range of species, conditions and contexts (Cohen & Beths Reference Cohen and Beths2020; Mogil et al. Reference Mogil, Pang, Silva Dutra and Chambers2020; Mota-Rojas et al. Reference Mota-Rojas, Olmos-Hernández, Verduzco-Mendoza, Hernández, Martínez-Burnes and Whittaker2020; Evangelista et al. Reference Evangelista, Monteiro and Steagall2022). While the GS is thought to be relatively easy and quick to train (Cohen & Beths Reference Cohen and Beths2020), there are limited training materials and courses available. Much of the information regarding training and usage of GS is secondary to developing or validating GS and primarily contained within the methods section of articles (Di Giminiani et al. Reference Di Giminiani, Brierley, Scollo, Gottardo, Malcolm, Edwards and Leach2016; Dai et al. Reference Dai, Leach, MacRae, Minero and Dalla Costa2020; Hohlbaum et al. Reference Hohlbaum, Corte, Humpenöder, Merle and Thöne-Reineke2020; Orth et al. Reference Orth, Navas González, Iglesias Pastrana, Berger, Jeune, Davis and McLean2020) or posters (NC3Rs 2022). A small number of online or face-to-face training courses in GS are intermittently available online (Flecknell & Leach Reference Flecknell and Leach2024). With the rising interest and greater research into GS, there has been more focus on inter-rater reliability and formal training in GS to ensure accurate, appropriate use in clinical, real-world, and research settings (Dai et al. Reference Dai, Leach, MacRae, Minero and Dalla Costa2020; Watanabe et al. Reference Watanabe, Doodnaught, Evangelista, Monteiro, Ruel and Steagall2020; Robinson & Steagall Reference Robinson and Steagall2024). Recently, a short, online, pictorial-based infographic training manual for feline (Felis catus) GS with a short online multiple-choice quiz has been made available via the app and website (Universite de Montreal and Steagall 2019). The horse (Equus caballus) GS app also offers users a similar very short training module (Animal Welfare Indicators Network 2015). Specifically, within Australia, GS training may be self-taught using pictorial charts and/or via reading of GS species-specific publications (S Cohen, personal communication 2025). However, none of these products, courses, apps or publications appear to formally incorporate or evaluate the use of training in GS to improve attitudes and outcomes towards the 3Rs, animal welfare, and pain management.

The social licence to operate (SLO), ethical, and legal requirements for research and teaching with animals requires a high standard of animal welfare and research (Brunt Reference Brunt2022; Crook Reference Crook2023; Golledge & Richardson Reference Golledge and Richardson2024). The use of evidence-based practices and approaches to support these requirements is essential to maintain high standards of excellence in animal welfare, 3Rs, and research as well as meet legal requirements and maintain social acceptability of research. The application of training targeting attitudes is thought to be a vector to support these outcomes (Franco et al. Reference Franco2023). Current evidence suggests the use of training for both knowledge and attitudes can support positive HBC in animal care staff to improve animal welfare outcomes in the animal and livestock industries (Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Rea, Hall, Sawyer and Hemsworth2001; Hazel et al. Reference Hazel, O’Dwyer and Ryan2015; Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Frye, Lord, Baysinger and Edwards-Callaway2019; McDonald & Clements Reference McDonald and Clements2019; Wilhelmsson et al. Reference Wilhelmsson, Hemsworth, Andersson, Yngvesson, Hemsworth and Hultgren2024). However, research implementing these training methods in the RTI remains limited (Gaafar & Fahmy Reference Gaafar and Fahmy2018; LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020). Consequently, this is a gap yet to be fully explored with great potential to support excellence in animal welfare and research outcomes across the industry. The objective of this study was to compare post-training differences in the knowledge and attitudes of participants undertaking standard technical training versus attitudinal training in the Australian and New Zealand (ANZ) animal RTI. While both programmes delivered technical instructions on the use of GS, only the enhanced training programme included human behaviour change and attitudinal training. To minimise attrition rates, participants acted as their own control and were given questionnaires before and after both types of training programmes which were used to investigate their respective impacts on the knowledge and attitudes of participants.

Materials and methods

Study design

The target population sampled were those aged 18 years and older involved in the care and use of animals in the RTI across ANZ within the 24 months prior to attending a training session. Participants enrolled in undergraduate programmes of study were excluded. The target population sampled included animal ethics committee members (AEC), researchers, post graduate students, animal facility staff, animal ethics and/or compliance staff, tertiary teachers, veterinarians, and related management or executives. Participants were enrolled to undertake a single training session between September 2022–March 2023 (Table S1; Supplementary material) and received either a control or enhanced training session (Figure S1; Supplementary material). The study consisted of two questionnaires delivered before (pre-training) and after (post-training) training in GS. This study was conducted as part of a University of New South Wales funded grant to improve animal welfare and the 3Rs. All research performed was undertaken in accordance with human ethics approval from the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HREC#2022-23675-29666-5) and University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 2022/928).

Participant recruitment

Industry associations, organisations, and institutions in ANZ associated with the animal RT industry were contacted formally by email and via industry conferences from September 2022 to February 2023 (Table S1; Supplementary material). Informal networks (e.g. social media, listservs) were used to recruit organisations (Table S1; Supplementary material). To recruit institutions, a standardised template was distributed which included information on the study aims, design, and requirements. Institutions were eligible for training sessions if they could provide a suitable location with high quality projectors with a minimum of 20 and a maximum of 80 participants.

Eligible institutions were provided with standardised communication materials consisting of formal and informal invites for circulation (Figures S2, S3, S4; Supplementary material). Communication materials explained that the data collected for the study would be anonymous, and provided details on study design, purpose, and eligibility criteria for individuals. The standardised template and wording were requested to be used in any communications in relation to the study and/or training sessions. Institutions were encouraged to use a combination of emails, newsletters, listservs, and/or other similar communication methods to circulate invitations. Institutions were given additional communication materials to disseminate at their discretion (e.g. flyers). An Eventbrite (San Francisco, CA, USA) registration link was included for individual attendee registration.

Questionnaire design and pilot testing

Questions (Tables S2, S3; Supplementary material) were designed to assess the knowledge and attitudes of participants and were based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen Reference Ajzen2002; Ajzen & Schmidt Reference Ajzen and Schmidt2020). Pre- and post-training questionnaires were created to evaluate participants’ knowledge and attitudes regarding animal welfare, the 3Rs, animal monitoring, pain, pain assessment, and GS using Qualtrics XM (Windows® 10, Seattle, WA, USA). Participants were requested to complete the paper-based pre-questionnaire on arrival and the paper-based post-training questionnaire immediately after completion of the training. Delivery of the enhanced (E) training sessions was completed in 30–40 min while delivery of control (C) training sessions was completed in 20–30 min.

There was a total of 36 questions in the pre-training questionnaire with 24 questions repeated in both pre- and post-training questionnaires to ensure consistency, continued engagement, and to test for any changes pre- and post-training sessions (Tables S2, S3; Supplementary material). The post-questionnaire contained an additional eight questions (Table S3; Supplementary material) that sought qualitative feedback on the training delivered (open-ended), the trainer (Likert), participant confidence (Likert), and attitudes towards the GS (Likert). The pre- and post-questionnaires were anonymous, numerically paired, and digitised for analysis (see Data processing and analysis). Questionnaires were piloted on two human social scientists and eight animal research and teaching experts, while control and enhanced training programmes were piloted in small groups (8–15 participants) consisting of researchers, veterinarians, animal facility staff and managers at Australian institutions. The participants used for pilot testing of the questionnaire and the training programmes were not included in the study.

Design and delivery of training programmes

Training programmes were delivered in person between September 2022 and March 2023 by an experienced expert trainer (SC). Participants received one of two 90-min training programmes which included an overview of all GS available at the time of the workshops (Figure 1; Supplementary material). Both programmes (referred to as control [C] and enhanced [E]) contained more detailed technical content on GS use in mice (Mus musculus), rats, rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), sheep (Ovis aries), and pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus). For the purposes of the study, only participants in the E programme received training targeting attitudes for HBC.

Figure 1. Comparison of favourable responses to questions pre- and post-grimace scale training for enhanced and control cohorts. For questions 1–7, (knowledge-based) this represents the percent responding ‘yes’ and questions 8–24 (attitude-based), this represents the percent responding ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’. The 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the model of the estimated marginal means.

The first group of participants trained received the E training programme. Thereafter, C training sessions were delivered until an approximate equal number of participants matched the first E training session that was delivered. Subsequently, alternating cycles of C and E training sessions were delivered to ensure an approximately equal number of participants in each cohort. Cohorts were blinded to the type of training programme received. Control training programmes were designed to reflect those typically utilised in Australian certificate IV methods for competency and assessment (Australian Government Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency 2022). Enhanced training programmes provided a greater focus on attitudes (behavioural beliefs) along with a greater depth and breadth of knowledge (knowledge) (Uchendu et al. Reference Uchendu, Desmenu and Owoaje2020). These sessions also used training methods which addressed cognitive, affective, and psychomotor learning (Adams Reference Adams2015) as well as techniques from the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen Reference Ajzen2002; Fishbein & Ajzen Reference Fishbein and Ajzen2011; Ajzen & Schmidt Reference Ajzen and Schmidt2020).

Data processing and analysis

Information from questionnaires were entered into an Excel® spreadsheet (Windows 10®, Microsoft® Redmond, WA, USA). Data entry sessions were approximately 1–2 h in duration. Entries were double checked by a second person after entry for accuracy every 3–5 questionnaires. Descriptive, quantitative, and semi-quantitative statistical analyses were undertaken using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria). A descriptive analysis of demographic data was performed to outline the profile of participants that completed C and E training sessions. Questions number 3, 4, 16, and 21 were not analysed beyond descriptive analysis due to an unusually high number of missing data that could not be successfully imputed.

The effects of training and the type of training method on participant questionnaire responses pre- and post-training were analysed using cumulative-link mixed models, with the response variables having either 7 or 3 ordinal outcomes. The corresponding numbers for the Likert scales were: 1 = strongly agree; 2 = agree; 3 = somewhat agree; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = somewhat disagree; 6 = disagree; 7 = strongly disagree; and mv = missing values. For the Yes/No/Unsure questions, ‘Unsure’ was a category between ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. The independent variables were training method (C and E), time (pre- and post-training) and the interaction between training method and time. A random intercept for participant was included to account for baseline differences for each participant. For each response, the interactions were tested using a likelihood ratio test. The P-value results were adjusted for multiple comparisons for the both the effect of training and effect of E vs C training. A permutation-based procedure to account for correlated tests was used as questions were expected to be correlated (Westfall & Young Reference Westfall and Young1993). This type of analysis permutes the labels of the training methods to estimate the joint distribution of the test statistics under the null distribution (of no effect of training method) and allows the selection of a threshold for a family-wise error rate of 5%.

The ‘estimated average difference’, across training methods, between pre- and post-questionnaires, per question, were calculated from the models using the ‘R’ package ‘emmeans’ for estimated marginal means. Log-odds coefficients and odds ratios with confidence intervals set to two standard errors were calculated. Questions with differences (P < 0.05) between pre- and post-questionnaires for training (E and C cohorts) or in E and C training methods were analysed to determine if demographic factors exerted any effects.

The datasets were further analysed to determine if there were significant differences (P < 0.05) in participants’ responses (pooled E and C datasets) post-training and/or any differences between E versus C training. The mice package (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn Reference van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011) with the ‘cart’ method of multiple imputation was used to impute missing data (found mostly in the C group’s pre-surveys) as this method assigns missing values from the available (non-missing) values of the datasets (Burgette & Reiter Reference Burgette and Reiter2010; Li et al. Reference Li, Stuart and Allison2015). Effect sizes across imputations were pooled using Rubin’s rule (Rubin Reference Rubin2004).

Only the post-training questionnaire had open-ended qualitative questions for participants to offer feedback on improvements or changes to future training sessions. All comments were transcribed, collated, and tabulated in Excel® and then transferred into Word® tables (Microsoft®, Redmond, WA, USA). A qualitative thematic open-coding approach to analysis was used to identify initial themes (Table S8; Supplementary material). Each time a potential theme was identified from these qualitative questions it was tabulated and allocated to the respective C or E training cohort. A reiterative approach was used to further consolidate initial themes identified into the final themes presented (Glaser et al. Reference Glaser, Bailyn, Fernandez, Holton and Levina2013; Clarke & Braun Reference Clarke and Braun2017).

Results

Participants and demographic analysis

Eight training programmes (5C: 3E) were delivered across three Australian states in four different cities and in one major city in New Zealand. Training was also delivered at the 2022 annual Australian and New Zealand Laboratory Animal (ANZLAA) conference. Attendance in each session ranged from 22 to 80 participants and participants were blinded to the type of training received (enhanced or control). A total of 232 participants attended the training programmes with 111 attending the enhanced and 121 attending the control sessions (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of participants (n) by demographic recruited into enhanced (E), control (C), training sessions for grimace scales. Animal ethics committee (AEC) member category and their associated industry role were combined. Demographics of participants did not differ between control and enhanced cohorts (all P >0.05)

Participant demographics in each cohort were overall similar for questions that demonstrated evidence of impacts on attitudes and knowledge pre- and post-training (P > 0.05) (Table S10; Supplementary material). Nearly two-thirds of participants (148/232) were formally trained or educated from an accredited institution with less than 10% not formally trained or educated. Most participants were trained in animal welfare monitoring (81.0%) and assessment (70.7%) but not in GS (73.7%). The most common research discipline (multiple selections permitted) amongst all participants (C and E cohorts) was biomedical research (56.0%) followed by teaching or training (11.6%), and veterinary research (10.3%). Participants most often worked (multiple selections permitted) with rodents (89.2%), small ruminants (19.4%), and guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) or rabbits (17.2%). Participants were typically over the age of 25 (25 to 40 [50.9%] or 40 to 55 [25.0%]), were either animal care staff (52.2%), researchers (25.4%), or graduate researchers (8.6%) that had been in the industry anywhere from less than 12 months to over 20 years (12.1–15.5%).

Pre-training knowledge and attitudes

The pre-training questionnaire was descriptively summarised to provide a baseline of knowledge and attitudes of all participants (cohorts C and E) (Tables 2, 3 and S9; Supplementary material). The 3Rs was the most well-known concept (93.5%) followed by the Five Freedoms (59.9%) and the Five Domains (40%). Most participants knew of the GS (82.3%) but were not confident in their use (65.1%). Almost all participants considered it important to identify and treat animal welfare issues (97.7%), treat pain (98.7%), and to provide training in identifying animal welfare issues (90.9%) and pain (91.8%) in animals. Participants often believed the average person in the RT industry could identify animal welfare issues (69.8%) and pain (64.1%) but thought they could do better (animal welfare issues [79.3%] and pain [80.2%]). Few participants thought lay people could identify animal welfare issues (22.9%) and pain (20.7%).

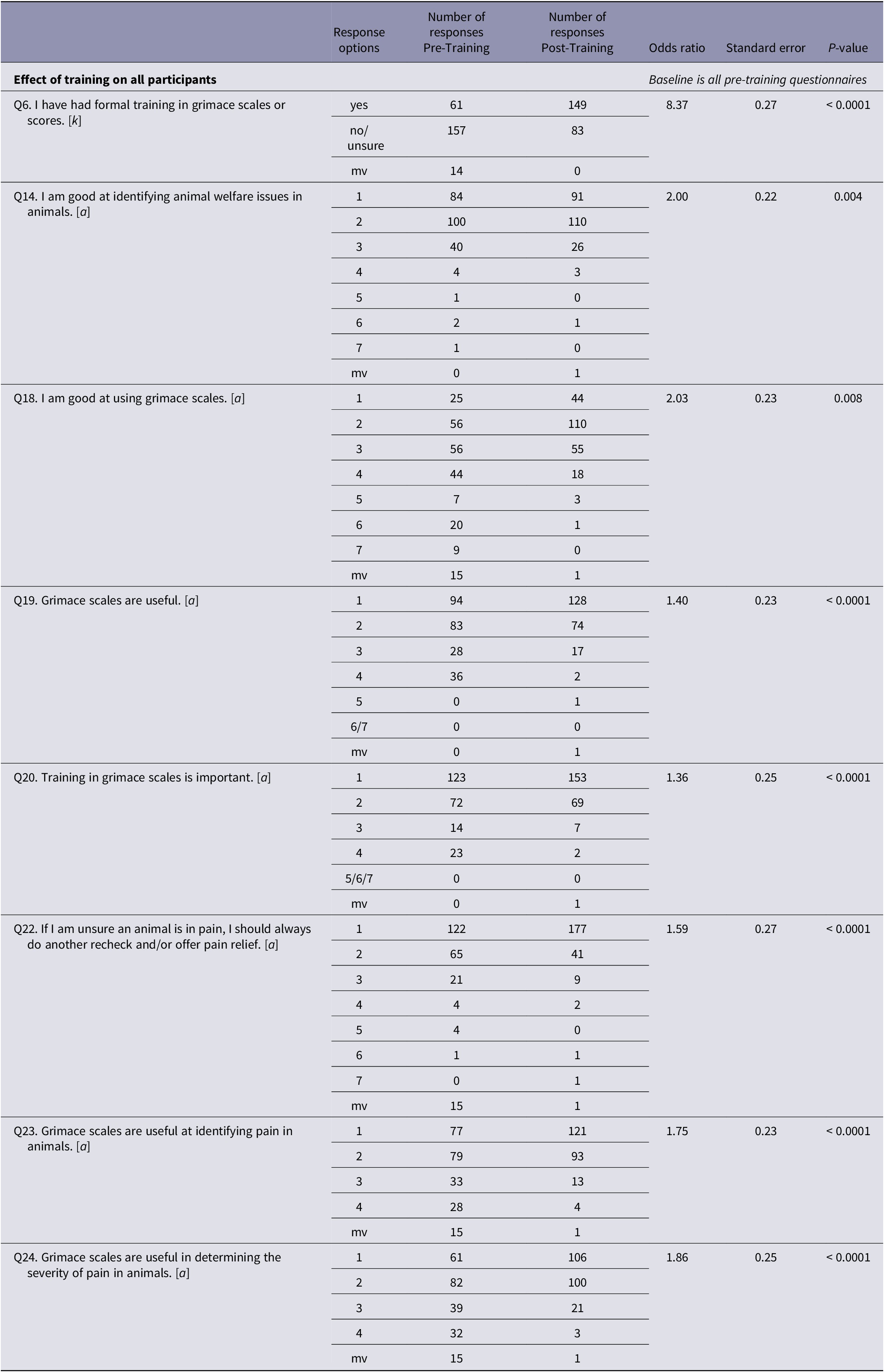

Table 2. Effects of training (either control or enhanced) on post-questionnaire responses for questions demonstrating statistically significant differences. Odds ratios represent the relative likelihood of improved responses post-training compared with pre-training questionnaire. Questions on attitudes (a) were scored using a Likert scale (with 1 equal to strongly agree to 7, strongly disagree) and knowledge (k) were scored as yes, no or unsure. There were a total of 232 participants and missing values (mv) were included

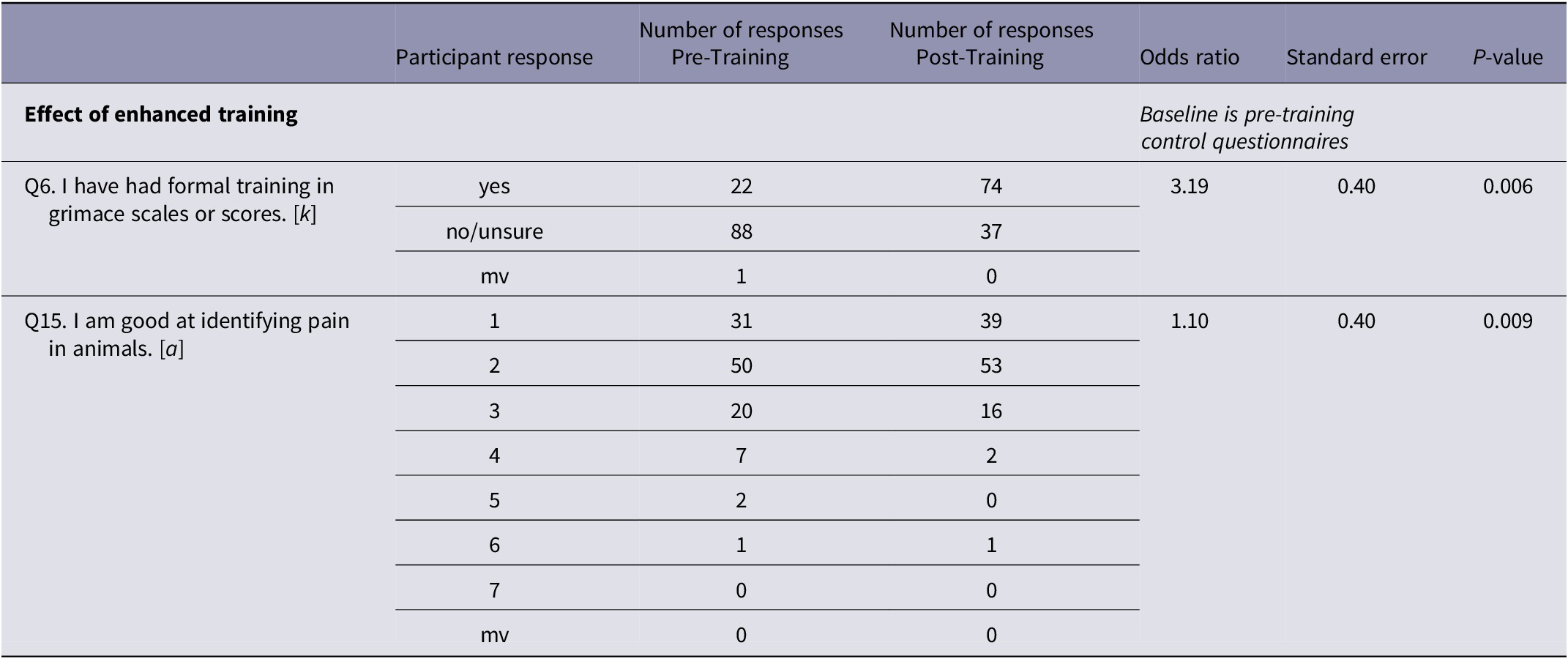

Table 3. Effect of receiving enhanced training on post-questionnaire responses for questions demonstrating statistically significant differences. Odds ratios represent the relative likelihood of improved responses post-training compared with pre-training questionnaire. Questions on attitudes (a) were scored using a Likert scale (with 1 equal to strongly agree to 7 strongly disagree) and knowledge (k) were scored as yes, no or unsure. There were a total of 232 participants and missing values (mv) were included

Training effects on knowledge and attitudes

Effect of training

For all questions (Q1–Q24), post-training responses demonstrated either no change or positive change (Figure 1). There was no evidence of participant knowledge regarding the Five Domains model (5D) (Mellor et al. Reference Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones and Wilkins2020), the Five Freedoms (5F) (Farm Animal Welfare Council 1979), and the likelihood of selecting ‘yes’ to receiving training in animal welfare assessment or in the monitoring of animals being affected by any type of GS training, including E training (Table 4). Post-training (Figure 1), more E and C trained participants positively agreed they had received formal training in GS (Q6), felt they were better at using GS (Q18), that GS were useful (Q19), specific for identifying pain (Q23), and the severity of pain (Q24).

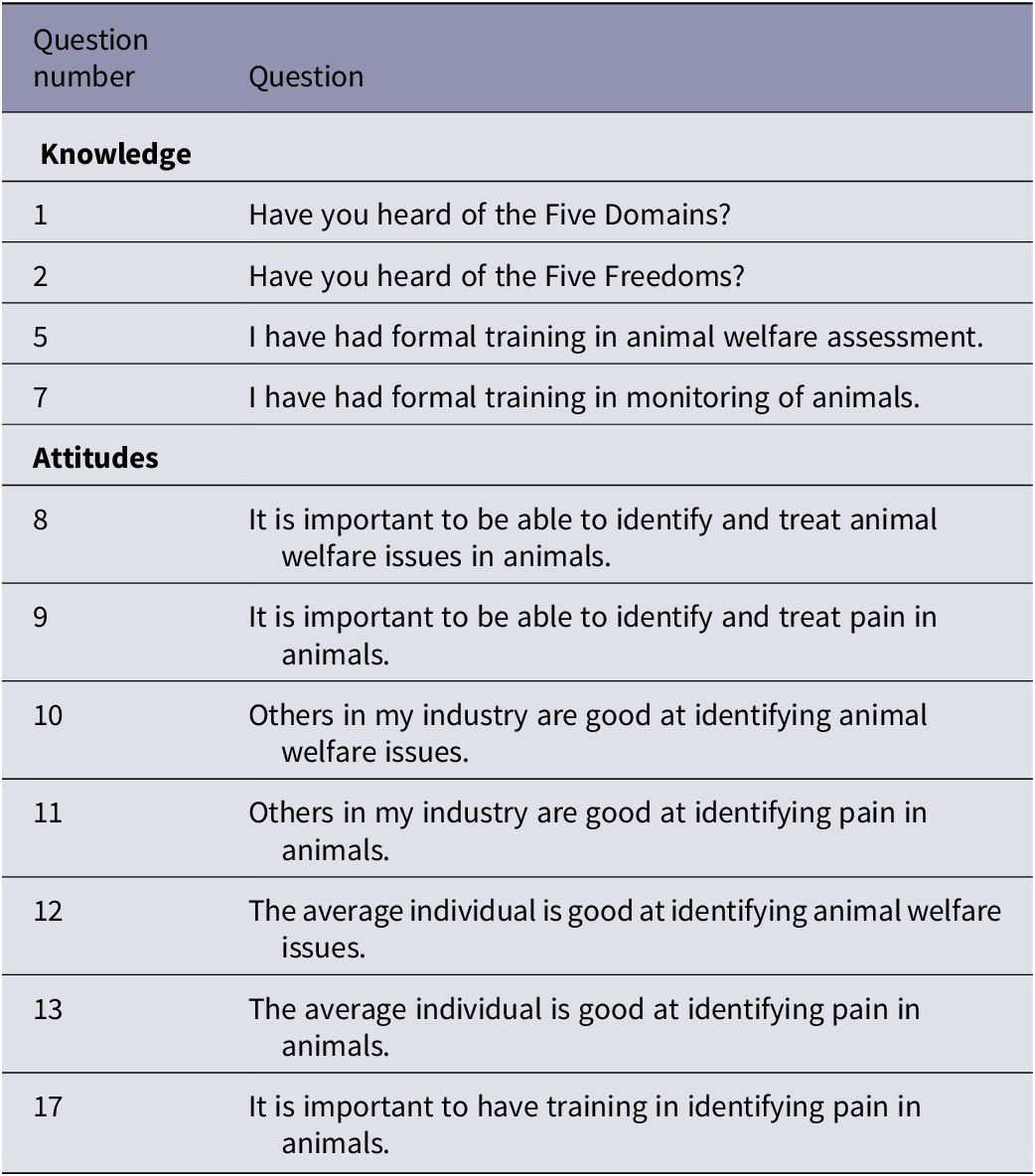

Table 4. A list of knowledge-based and attitude-based questions that were answered by participants but were unaffected (P > 0.05) by any type of training in grimace scales. Questions 3, 4,16, and 21 were not analysed due to insufficient data

The odds ratio (OR) for responses to some knowledge (k) and attitudes (a) questions (Q) positively increased (P < 0.05) from pre- to post-training (Table 2). Following training (C and E cohorts), participants had 8.4 times greater odds of indicating they had received formal training in GS compared to pre-training responses (Table 3; Q6k). When compared to untrained pre-training responses, post-training participants from both cohorts (C and E) were more confident in their ability to identify animal welfare issues (OR 2.00; Q14a), their use of GS (OR 2.03; Q18a), and were more likely to recheck or offer pain relief for animals that might be in pain (OR 1.59; Q22a). Trained (C and E cohorts) versus untrained participants were also more likely to believe that GS were useful (OR 1.4) (Q19a), important (OR 1.36) (Q20a), specific for identifying pain (OR 1.75) (Q23a), and useful in determining the severity of pain (OR 1.86) (Q24a).

Effects of enhanced training

Enhanced and C training cohort responses to questions post-training were also compared (Table 3). Participants in the E training cohort had 3.2 times greater odds of agreeing they received training in GS (Q6k) compared to C training cohorts. Additionally, only participants in E training sessions, in contrast to C training sessions, indicated they were ‘good at identifying pain in animals’ (OR 1.10) (Q15a).

Qualitative results

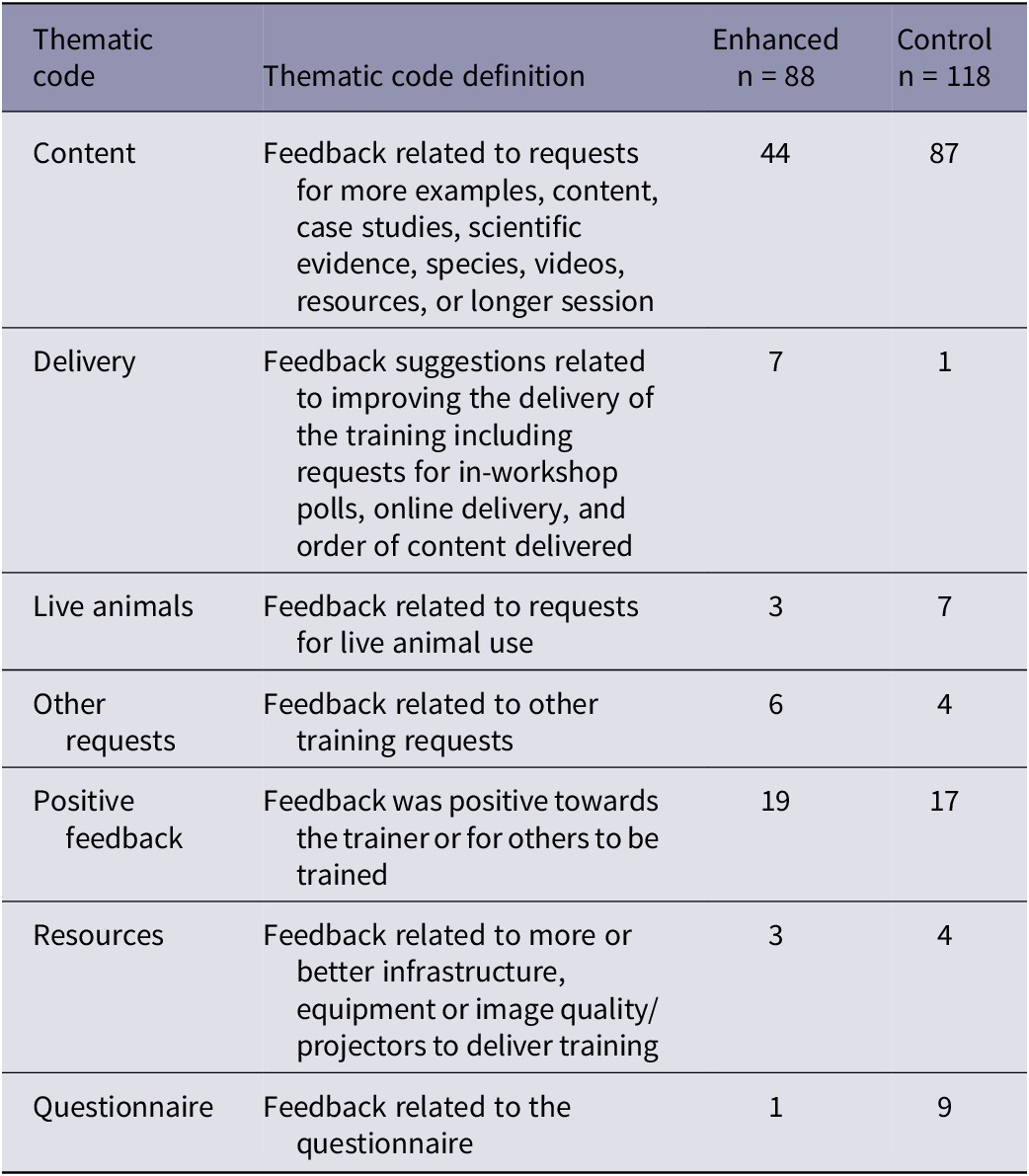

Thirty-three themes were initially found across E (19) and C training (14) cohorts (Table S8; Supplementary material). Themes were reiteratively condensed down to a total of seven relevant themes related to the delivery of training sessions: resources, content, delivery, live animals, positive feedback, other requests, and questionnaire (Table 5).

Table 5. Total number (n) and percent (%) of comments by theme as provided from participants after either enhanced (E) or control (C) grimace scale training sessions. Initial themes* were extracted using an open-coding method, defined, and consolidated

Control training had a greater number of participant feedback responses (118) than E training (88). A common theme for participants in both E (50%) and C (73.7%) training was requests for more training content. Positive feedback was more common in E (22.0%) versus C sessions (9.4%). Suggestions to improve the delivery of the content were also more frequent in E (8.0%) in comparison to C cohorts (0.9%). Participants in C training groups offered more feedback relating to the questionnaire (7.6%) and had more requests for live animal use (5.9%) versus E cohorts (1.1%: 3.4%, respectively). Requests for more resources or other requests unrelated to the GS training across E (3.4%: 6.8%, respectively) and C cohorts (3.4%: 3.4%, each) were similar.

Representative quotes of interest from participants for Q39 include: “I would like to have had more formal training in grimace scales earlier in [sic] my industry [E]” and “I would like to have had more animal welfare training and the training about pain identification [E]”.

Discussion

Training and attitudes

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to use training to target attitudes towards animal welfare via improving the use of GS and encouraging better pain management. This research demonstrates that the delivery and development of high-quality training, especially training with a focus on training targeting attitudes (E cohort), positively impacts participant knowledge and attitudes. Participants in E and C cohorts were up to 2–4 times more likely to demonstrate changes in their skills and attitudes towards the GS, pain identification, and pain management. The use of E training provided even greater and further unique benefits. As per the Theory of Planned Behaviour Change (Ajzen & Schmidt Reference Ajzen and Schmidt2020) and other studies, these changes have the likely potential to improve animal welfare, 3Rs, and research outcomes in the ANZ RTI. Additionally, for the first time, baseline information on knowledge and attitudes towards the 3Rs, animal welfare, GS, and pain management were identified within Australia. Such information could be used to inform and enable targeted national research training programmes to improve the 3Rs, animal welfare, and research practices. The use of qualitative questions in the survey offered further support towards these outcomes and produced further insights for refinements and considerations when delivering and developing training programmes. While training is not a panacea for animal welfare, pain management, or 3Rs’ issues, this work demonstrates these techniques may be a practical and valuable method in the animal care and use industry to improve knowledge and attitudes.

The outcomes from this research align with other studies that have used different training methods to improve knowledge and attitudes around livestock handling (Coleman & Hemsworth Reference Coleman and Hemsworth2014; Wilhelmsson et al. Reference Wilhelmsson, Hemsworth, Andersson, Yngvesson, Hemsworth and Hultgren2024), livestock management (Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Hemsworth, Hay and Cox2000; Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Coleman, Barnett, Borg and Dowling2002; Coleman & Hemsworth Reference Coleman and Hemsworth2014; Hazel et al. Reference Hazel, O’Dwyer and Ryan2015), in livestock abattoirs (Descovich et al. Reference Descovich, Li, Sinclair, Wang and Phillips2019) and in laboratory research and safety practices (Gaafar & Fahmy Reference Gaafar and Fahmy2018; Uchendu et al. Reference Uchendu, Desmenu and Owoaje2020). This work has highlighted that training (especially E training), can also elicit positive changes to participant confidence and beliefs in these specific areas which is likely to influence human behaviours (Fishbein & Ajzen Reference Fishbein and Ajzen2011; Ajzen & Schmidt Reference Ajzen and Schmidt2020) and human animal-interactions (Coleman & Hemsworth Reference Coleman and Hemsworth2014; Descovich et al. Reference Descovich, Li, Sinclair, Wang and Phillips2019; LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020) to benefit to the GS, animal welfare, and the 3Rs. We also found participants in the E cohort had unique benefits which included assigning a greater post-training value and benefit to training in GS versus pre-training responses.

3Rs, animal welfare, and pain management

Appropriate pain relief can be a professional (veterinary), legal, ethical, and experimental hallmark of good animal welfare and research outcomes. Best veterinary practice supports the use of validated pain assessments to identify pain and ensure adequate analgesia after the administration of pain relief (Mathews et al. Reference Mathews, Kronen, Lascelles, Nolan, Robertson, Steagall, Wright and Yamashita2015; Gruen et al. Reference Gruen, Lascelles, Colleran, Gottlieb, Johnson, Lotsikas, Marcellin-Little and Wright2022; Monteiro et al. Reference Monteiro, Lascelles, Murrell, Robertson, Steagall and Wright2023). While animal welfare and pain assessment are important for maintaining good animal welfare and research outcomes, in this study participant attitudes on the treatment and assessment of animal welfare issues and pain did not appear to change post-training. Training of any type (C or E) also did not appear to shift participants’ attitudes towards rechecking animals post-administration of pain relief and similarly E training when compared to C training did not markedly shift participants’ attitudes towards overall identification of pain in animals. However, pre-training attitudes of participants exhibited high levels of agreement (agree to strongly agree) with these questions. It is possible that scores for these questions reflected that these participants had a previously good understanding and positive attitudes towards these topics or that perhaps this type of training in GS is less effective in shifting participant attitudes. In contrast, trained participants (C and E cohorts) indicated they were more likely to offer pain relief to animals or to recheck animals if they were unsure an animal was in pain. Enhanced training cohorts (compared to C cohorts) also displayed further changes to their attitudes. Enhanced participants were more than twice as confident in identifying pain in animals and three times more likely to agree they had received formal training in GS post-training. These results align with the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen & Schmidt Reference Ajzen and Schmidt2020). This theory has been shown to suggest that human attitudes (salient beliefs) are the best predicator of volitional human behaviour. As such, training that targets the beliefs that underlie specific behaviours can result in human behaviour change. Consequently, while training to competency is important, and can be useful, cognitive-behavioural training (e.g. Prohand©) targets the attitudes that underlie key behaviours that can improve animal welfare outcomes (Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Coleman and Barnett1994, Reference Hemsworth, Coleman, Barnett, Borg and Dowling2002; Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Hemsworth, Hay and Cox2000). This offers a vital opportunity to modify attitudes (e.g. more positive attitudes towards specific pro-social behaviours) to increase the performance of specific pro-social behaviours that can result in better animal welfare, pain management, and the 3Rs (LaFollette Reference LaFollette2020; LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020). More research is needed to determine which factors (e.g. content, delivery, methods) may be most effective in eliciting positive changes in attitudes and if these results are replicable across other animal care industries and animal care/welfare techniques.

From the pre-training questionnaire (baseline) results, the majority of participants were aware of the 3Rs (oldest framework) which has had an ongoing focus within the international RTI since 1959 (Russell et al. Reference Russell, Burch and Hume1959; Franco & Olsson Reference Franco and Olsson2014; Tannenbaum & Bennett Reference Tannenbaum and Bennett2015; National Health and Medical Research Council 2019) and aligns with the prior survey research from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council determining awareness of the 3Rs in the ANZ RTI (National Health and Medical Research Council 2019). The next most commonly known framework identified was the 5F and then the 5D. Although many participants worked with livestock, approximately half were unfamiliar with the 5F which was formalised in the 1970s in response to livestock management (Farm Animal Welfare Council 2009). Similarly, the 5D was published over 25 years ago and has been used by animal ethics committees and many others around the world to assess the welfare of animals (Mellor & Reid Reference Mellor and Reid1994; Mellor Reference Mellor2016; Mellor et al. Reference Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones and Wilkins2020; Kells Reference Kells2022; Beausoleil et al. Reference Beausoleil, Swanson, McKeegan and Croney2023; Wilkins et al. Reference Wilkins, McGreevy, Cosh, Henshall, Jones, Lykins and Billingsley2024). However, more than half of the participants were unaware of this framework. Given this newly identified gap, future training should consider formal inclusion of modern animal welfare assessment frameworks (e.g. 5D) that focus on promoting positive animal welfare experiences rather than simply avoiding negative experiences (Mellor Reference Mellor2016).

The reporting of mixed methods quantitative-qualitative information in surveys to support refinements for better practices seems to be used less frequently in animal care training when compared to other disciplines (Rosenberg et al. Reference Rosenberg, Kamin, Glicken and Jones2011; Shearer et al. Reference Shearer, Ng, Dunford and Kuo2018; Maltby et al. Reference Maltby, Mahadevan, Spratt, Garcia-Esperon, Kluge, Paul, Kleinig, Levi and Walker2024) (e.g. medicine, education, pharmacy). However, this study has shown there to be potential additional qualitative insights from cognitive behavioural training and similar methods that have been used (e.g. in livestock), that may further support the use of targeted training for attitudes to improve the welfare and management of research (Gaafar & Fahmy Reference Gaafar and Fahmy2018; LaFollette Reference LaFollette2020; LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020) and livestock animals (Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Hemsworth, Hay and Cox2000; Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Coleman, Barnett, Borg and Dowling2002; Coleman & Hemsworth Reference Coleman and Hemsworth2014; Hazel et al. Reference Hazel, O’Dwyer and Ryan2015; Descovich et al. Reference Descovich, Li, Sinclair, Wang and Phillips2019; Wilhelmsson et al. Reference Wilhelmsson, Hemsworth, Andersson, Yngvesson, Hemsworth and Hultgren2024). For example, qualitative differences between C and E cohorts provided additional support for the results and topics explored in the quantitative study outcomes including but not limited to potentially more positive engagement with training and 3Rs benefits. Additionally, E cohorts exhibited a greater frequency of positive and constructive comments towards improving training delivery with fewer requests for live animal usage. This contrasts with the C cohort, which offered more feedback more frequently focused on the questionnaire and a greater number of requests for the use of ‘live’ animals. This could have been related to the lower engagement with the training materials within the C cohort which may have precipitated in more participants requesting live animals to supplement C training sessions. Further exploration into this trend could be important in validating high-quality training for attitudes and knowledge could encourage more engagement with training content and support better animal welfare and 3Rs uptake (i.e. replacement and/or reduction). Offering the opportunity for participants to submit qualitative feedback for analysis may in future studies continue to provide additional insights and opportunities to improve training and/or avenues for further research.

Study limitations

This study is reflective of the ANZ RTI population, but like many opt-in studies, it is susceptible to self-selection bias (Elston Reference Elston2021). Institutions and individuals that do not desire to be professionally active in the RTI industry would have been unlikely to be on industry listservs and/or not respond to requests for participants via industry newsletters, emails, or conferences. In addition, to maintain participant anonymity, we were unable to delve deeply into potential impacts or effects of some participant demographics such as location, institution, details on research discipline, and/or species due to the small size of the ANZ RTI. Although demographic factors did not appear (P > 0.05) to influence training outcomes overall, the literature continues to be conflicted regarding the role of demographics. Some studies have shown gender or age may affect attitudes to training in animal welfare/care (Descovich et al. Reference Descovich, Li, Sinclair, Wang and Phillips2019) while others have not (LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020; Wilhelmsson et al. Reference Wilhelmsson, Hemsworth, Andersson, Yngvesson, Hemsworth and Hultgren2024). In this study, most (205) participants were animal care staff, researchers, or graduate students. There was also a wide range of diversity in species, but most participants worked with rodents, sheep, rabbits, and/or guinea pigs. While this is likely to be a reflective composition of the ANZ RTI, it may overlook participants from less common industry roles (e.g. animal ethics committees) or those working with other species (e.g. fish). It would have been ideal to have also secured more than one session in New Zealand, the session included participants from multiple institutions and in a location with the largest concentration of those working with animals in RT. The use of qualitative interviews could have provided further insights into the reasons behind participants choice of responses. For example, approximately one-third of participants selected that they did not feel they had received formal training in GS in post-training questionnaires. It is possible participants did not feel they had been formally trained in the workshop due to the lack of formal competency assessment, the lack of a certificate, and/or did not understand the context of the term ‘formal’. Additionally, it would be very important in future studies to identify practices and methods to minimise missing data. As a result, these limitations may or may not have affected or reduced the potential discovery of other findings from this research.

Future directions and recommendations

While training and training targeting attitudes is not a panacea to mitigate all identified gaps in animal welfare, pain management, and/or 3Rs, we have demonstrated it can be a potentially important and invaluable tool to foster better human-animal interactions and human behaviour change. Similar to research in other animal use industries (LaFollette et al. Reference LaFollette, Cloutier, Brady, O’Haire and Gaskill2020; Grandin et al. Reference Grandin, Lanier and Deesing2021; Robinson & Steagall Reference Robinson and Steagall2024; Wilhelmsson et al. Reference Wilhelmsson, Hemsworth, Andersson, Yngvesson, Hemsworth and Hultgren2024), both the qualitative and quantitative results from this research demonstrated training improved participant knowledge and attitudes. In alignment with the Theory of Planned Behaviour, changing attitudes and behavioural beliefs (predicators of human behaviour) can improve the quality of human-animal interactions and subsequent animal care and welfare. Based on these results it is recommended that appropriate high-quality training targeting key attitudes should be undertaken by those working with animals in the RTI. Implementing a more uniform and consistent approach to training can also offer tangible benefits to the ANZ RTI and parallel other international RTI requirements (e.g. UK, EU) (Gyger et al. Reference Gyger, Berdoy, Dontas, Kolf-Clauw, Santos and Sjöquist2019; UK Home Office 2023) with the benefit of meeting regulatory obligations and SLO. Similarly, the addition of competency assessments could be included in revisions to research and training frameworks to ensure participants are trained to competency to provide formal assurance of positive animal welfare outcomes.

Further studies should focus upon standardising, refining and determining the future impacts of training for attitudes to improve animal welfare, pain management, and 3Rs practices in the ANZ RTI. The use of longitudinal studies and application of these methods to other types of training in this industry are possible areas for future direction. Future trials could include follow-up via post-training interviews or surveys and/or observation of participant behaviour. Another area for exploration in training for attitudes in GS (and other techniques) would be to determine whether the delivery method (e.g. online real-time or pre-recorded) and use of technologies (e.g. apps, software) may impact outcomes. In addition, it would be ideal to better understand if and how demographics may or may not play a role in attitudinal training outcomes potential. Additionally, the use of these techniques could be applied to help support a ‘Culture of Care’ within ANZ RTI. As training is one of the foundational elements of this framework (Greenough & Mazhary Reference Greenough and Mazhary2021), the use of training for attitudes could be a preferred choice when developing institutional training programmes (frameworks) to promote more positive attitudes towards animal welfare, the 3Rs, and a ‘Culture of Care’. More broadly, this type of training can be further applied to other types of animal management and/or other human-animal interactions or activities (e.g. wildlife, aquatic animals) to support better animal care and welfare.

Animal welfare implications

In conclusion, effective training is a technique that can be used to elevate animal welfare and care practices by improving the knowledge and attitudes of those working with animals. Institutions and the broader animal care and use industry have the potential to improve human-animal interactions and positively change beliefs and behaviours by implementing training with attitudes. More specifically, the implementation of quality formal training in the GS improves knowledge and attitudes towards pain management, animal welfare, and the 3Rs. However, to maximise animal welfare, 3Rs, and pain management training outcomes, training for attitudes should be incorporated to offer additional benefits, including being more confident in GS use, better attitudes towards pain management, greater engagement with training materials, and fewer requests for the use of live animals in teaching. The results from this research support recommendations for formal standardised and/or accredited training with attitudes should be required by the research and teaching industry, funding bodies (e.g. National Health and Medical Research Council), regulators and for licencing/regulatory requirements, AECs, and all institutions prior to staff working with animals to promote better animal welfare, 3Rs, and research outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/awf.2026.10064.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the organisation, institutions, and individuals for their time and enthusiasm in partaking of our study.

Competing interests

This research was undertaken from a University of New South Wales 3Rs grant and University of Sydney graduate research training programme scholarship. The funders did not play a role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, or the decision to submit to Animal Welfare. All authors are associated with a research and teaching institutions and use animals in their research and/or teaching. SC has intermittently worked with government and animal industries as an employee and/or consultant at various stages of this research project and development of the manuscript.