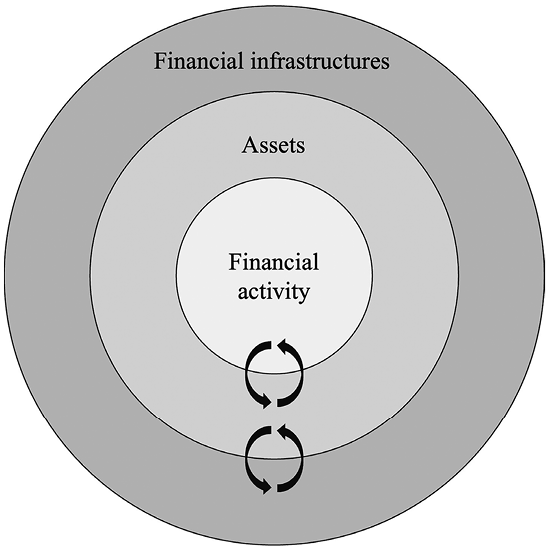

1 Introduction: Infrastructural Liquidity

Whatever one’s theory of, or political stance on the proper role of finance, it is difficult to deny that financial liquidity is crucial to the reproduction of contemporary capitalism. Capitalist states are increasingly preoccupied with maintaining flows of money, credit, and capital investment, and financial markets are crucial to that circulation. Over recent years central banks have gone to great lengths to avoid another market freeze like what happened during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008–2009. At the heart of that crisis was a collapse of liquidity (Nesvetailova, Reference Nesvetailova2010), and we can only understand ongoing state support of financial markets by studying the state’s preoccupation with maintaining liquidity (Langley, Reference Langley2015). But what exactly is liquidity, who does it serve, and why? These questions are rarely asked, although some attention has recently been paid to uneven access to liquidity and how this relates to inequality (Adkins, Cooper, and Konings, Reference Adkins, Cooper and Konings2020; Konings and Adkins, Reference Konings and Adkins2022). What is clear is that fifteen years after the GFC, and despite widespread resentment of the financial sector, that sector is more deeply entangled with capitalist economies and states than ever before. This state support is the starting point for my argument that financial markets have become infrastructural.

This state–finance–liquidity entanglement can only be understood in the context of half a century of layered financialization. Innovations in securitization (Leyshon and Thrift, Reference Leyshon and Thrift2007) and assetization (Birch and Ward, Reference Birch and Ward2022), combined with record levels of financial debt (Streeck, Reference Streeck2014), mean that financial stability has become increasingly dependent upon circulation through financial markets. Financial derivative contracts, which did not exist until the early 1970s, now constitute an enormous system of marketized financial risk management that is crucial for coping with uncertainty related to the future value of assets. They are deeply entangled with debt maintenance, portfolio management, currency exchange, and international trade, not to mention their privileged position in energy, raw material, and agricultural markets. The size of the global derivatives market is typically (and crudely) measured at five or more times the size of world gross product.1 Furthermore, marketized, short-term repurchase (repo) agreements between financial institutions, which are not derivatives but are typically coupled with derivatives trades, are now the main way central banks lend and thus influence macro-financial liquidity on a daily basis (Gabor and Ban, Reference Gabor and Ban2016) and are an important part of central banks’ pivotal role in ‘new’ state capitalism (Sokol, Reference Sokol2023). Together, these developments contribute to the widespread marketization of financial relationships across socio-economic fields. As a result, capitalist states treat financial markets as a crucial underpinning of production, circulation, and consumption, and thus as a system that must be protected from both endogenous and exogenous threats. In other words, liquid financial markets are now treated as a critical infrastructural system.

The concept of liquidity is most recognizable as a defining characteristic of money. Money is considered liquid because it can be exchanged for other things with little friction or cost. As a liquid store of value then, money is a hedge against uncertainty. But in societies where markets are the dominant mode of distributing goods and services, including the basic necessities to sustain life, liquidity can be a matter of life and death. As such, the ‘preference’ for liquidity, as Keynes (Reference Keynes1936) understood it, becomes a driving force of social organization in capitalism (Aglietta, Reference Aglietta2018). This desire for liquidity, which we might think of as the option to exchange later, is institutionalized in the financial sector, and as such is one of the basic organizing principles of post-1970s financialized capitalism (Meister, Reference Meister2021).

In the financial sector derivatives function in a similar way to money liquidity. They allow actors and institutions to put off decisions about their interest in specific commodities or assets. Meister (Reference Meister2021) calls this quality of derivatives ‘optionality’, which is the capacity to delay choices into the future, but at the same time continually calculate the costs of those delayed decisions.

On one hand then, finance capital has internalized optionality and the risk management that goes with it. But like all attempts to profit in capitalism there is an imperative to keep value – or in this case money, financial instruments, and their valuation – in motion. As such, financial market liquidity has become the sine qua non for the reproduction of contemporary capitalism, and the market freeze of the GFC was the exception that proved the rule. This is why, on the other hand, capitalist states and civil societies have developed an ‘infrastructural imaginary’ (Langenohl, Reference Langenohl2020). Because, just as risk management of individual assets has been internalized within the financial market system, the entire risk management system must, in the final instance, be backed up by the state. This chapter interrogates both the market systems that constitutes this financial infrastructure and the politics that are necessary to sustain it. In relation to the latter, the chapter asks how we might rethink politics in the age of financialization, and not least the politics of uneven access to liquidity across socio-economic classes.

The rest of the chapter is organized into four sections. Section 2 sets the scene by defining financial infrastructure in both socio-technical and political economic terms. Section 3 explores the development of financial interconnection since the 1970s, focusing on derivatives and their unique relationship with liquidity and the state. Section 4 dives deeper into the financial, temporal, and spatial functions of derivatives. Section 5 concludes the chapter by employing the concept of infrastructural inversion to rethink liquidity. It then offers an analytical path toward turning that politics of financial infrastructure on its head by questioning whether society really needs to rely so heavily on marketized optionality and liquidity.

2 Solidifying Infrastructural Politics

As this volume demonstrates, there are socio-technical (Pinzur, this volume) and political economic (Coombs, this volume) reasons that contemporary finance appears to be infrastructural. But rather than making a strong ontological argument about the infrastructural nature of financial systems, I am interested in the effects of capitalist states treating finance, and specifically financial markets, as infrastructure. While money, finance, and the state have a long history of entanglement (Muellerleile, Reference Muellerleile, Domosh, Heffernan and Withers2020), since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the USA and then to a greater extent after the 2008–2009 GFC, capitalist states have cast their infrastructural gaze upon financial markets, not least because they have become more vulnerable to breakdown. In this section I will offer three explanations of how this has happened, related to socio-technical dynamics, securitization, and state infrastructural power.

First are socio-technical dynamics that can be further sub-divided into three categories related to circulation, ordinariness, and capacity. To begin with, infrastructural systems tend to be enabling rather than directly productive, and the things they enable usually relate to movement, connectivity, and circulation through space (Larkin, Reference Larkin2013). Transportation, energy, and water systems are emblematic. Because they are connective, and, further, because they tend to connect to a wide variety of socio-economic sectors, they normally require ‘rights of way’ (O’Neill, Reference O’Neill2013) through public and private space and across territorial or jurisdictional boundaries. Consider for instance the ways railways or oil pipelines criss-cross political territory. Furthermore, even though some infrastructural systems are privatized, they almost always serve both public and private purposes. Consider transport infrastructure, for instance.

Financial markets have many of the same circulatory characteristics. Rather than producing new economic value, they mostly assist in circulation of existing value,2 the flows of which frequently cross political borders and produce novel financial geographies. Further, even though financial exchanges are now largely private enterprises (see Petry, Reference Petry2021), they are heavily regulated by the state and endowed with quasi-public purpose, even if the vast majority of the benefits accrue to already existing wealth (Piketty, Reference Piketty2014).

Secondly, for those who have access to them infrastructural systems are often mundane and technical, typically operating in the background. As a result, at least for the everyday user, infrastructural systems tend to blend into everyday life, only drawing serious attention when they break down (Bowker and Star, Reference Bowker and Star2000). Financial systems have a similar quality. Despite the growing integration of things like payment systems into everyday life, most financial operations are obscured from public view. Even when their inner workings are on display, during a financial crisis for instance, most people struggle to make sense of them. Like most infrastructure then, finance is a field of technical expertise.

Thirdly, because infrastructure is circulatory, but also technical, it also tends to have limited capacity. Whether vehicles, people, water, energy, or data, the systems that move these things have limits, and when they are pushed beyond their capacity they lock up or break down. A seemingly sensible solution is to increase the capacity of infrastructural systems. However, in a paradox originally identified by William Stanley Jevons (Alcott, Reference Alcott2005), and what traffic engineers call induced demand, increasing the technological efficiency and thus capacity of a technical system often incentivizes more use, which, rather than enhancing resilience, may just cause more dramatic breakdowns.

Financial markets have a similar finite capacity to process transactions in an orderly or liquid fashion (Langenohl, Reference Langenohl2024). At the same time, digital technologies continue to expand the capacity of the market system to process trades. Regardless, when markets are pushed beyond their capacity, so-called fault lines can form (Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen, and Porter, Reference Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen and Porter2019, pp. 923–926) and markets can break. These socio-technical breakdowns take different form in different historical or geographic contexts. It happened during the infamous 1987 US stock market crash, where telephone lines between New York and Chicago were overloaded and traders and other market actors could not access market prices fast enough (Muellerleile, Reference Muellerleile2018). So-called flash crashes are another instance, although at an accelerated pace (Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen, and Porter, Reference Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen and Porter2019, pp. 923–926). The bottom line is that financial markets are fragile, and technologically driven efforts to speed them up make them more, not less, vulnerable.

To summarize then, the first infrastructural quality of financial markets is that they are socio-technical in nature and this helps us understand their complexity and fragility, but also their relative ordinariness for everyday life. As such, it is perhaps unsurprising that states take an interest in ensuring that they function, and an interest in repairing them when they break down. This state interest has been evident since at least the dawn of capitalism, but the relationship between financial markets and capitalist states has deepened since the early 1970s, and this brings me to the second way that financial markets are infrastructural.

Since the September 11, 2001 attacks on the USA, and intensifying during and after the GFC, financial markets have become securitized, meaning they are treated as crucial for securing socio-economic futures (de Goede, Reference de Goede and Burgess2010; Westermeier, Reference Westermeier2019). Financial security, in other words, is not only important for capitalist accumulation, but also for the basic health and reproduction of capitalist society. As the USA in particular has become more focused on preparedness for emergency and crisis, financial markets are now subject to ‘vital system security’ apparatuses similar to government approaches to other interconnected systems like energy, transportation, and water (see Collier and Lakoff, Reference Collier and Lakoff2015).

Langley (Reference Langley2015), for instance, has demonstrated that the state’s reaction to the GFC was a matter of financialized bio-politics. In the wake of a market breakdown, the state was mainly concerned with securing financialized well-being for the population, which began with rescue and repair of the financial market system. It is important to note, however, that the state chose to rescue banks, brokers, and insurance companies or, in other words, the institutionalized market system, rather than step around the market and provide direct financial assistance to the holders of mortgages who were at risk of losing their homes. The priority was restoration of circulation through the vital infrastructural system rather than direct intervention to assist the end users of that system.

The third way financial markets resemble infrastructure relates to the ways states integrate with financial institutions to exert power over and through their populations. Mann (Reference Mann1984) called this infrastructural power (see Coombs, this volume), in contrast to despotic power, which is more direct, uninhibited, and often enforced through violence. Infrastructural power, which is associated with capitalist and democratic states, explains how states depend upon infrastructural systems for the distribution of power and influence through civil society (Mann, Reference Mann1984). One example of this is the way the USA has intervened in mortgage markets to encourage single-family home ownership since the 1930s. These interventions have taken different forms, including iterative redefinition of mortgages, but with the common goal of (re)constructing a national market for mortgage finance (Ashton and Christophers, Reference Christophers2018). This exertion of state power via financial markets to encourage home ownership is not unique to the USA. While it took different forms, the basic strategy of encouraging middle-class home ownership in an effort to produce social stability was a common strategy among states in the Global North in the twentieth century (Forrest and Hirayama, Reference Forrest and Hirayama2015).

Perhaps a more profound example is the various ways that central banks depend upon private banks and financial markets to implement their policy goals and monetary governance strategies. Not unlike the USA, which began earlier in the 1970s, from the 1990s the EU attempted to develop a single, interconnected capital market system to encourage continent-wide and securitization-led capital investment (Braun, Gabor, and Hubner, Reference Braun, Gabor and Hubner2018). Technocratic reformists within the Italian state, for instance, encouraged derivatives-based arbitrage between Italian and German state debt as a way to ease Italy’s entry into the Economic and Monetary Union (Lagna, 2016). Broader efforts to construct a single capital market stalled in the wake of the GFC, but since then, the European Central Bank (ECB) has actively employed financial markets to achieve its monetary policy goals (Braun, Reference Braun2020). While post-GFC there was initially significant resistance to reintegration of a European repo market and serious proposals to implement a repo transaction tax, the banking industry successfully lobbied against this, and the repo market has rapidly expanded in size (Gabor and Ban, Reference Gabor and Ban2016). The ECB also directly assisted in the expansion of the asset-backed security market in Europe, changing its rules to accept the securities as collateral. As Braun explains (2020), all of this translates into a state–finance nexus of infrastructural power, ‘market-based central banking’, and, generally, the increasing influence of the financial sector over European economic policy.

3 Optional Entanglements

Financial derivatives have only existed since the early 1970s, and yet they now sit at the core of financial market systems. Derivatives create interdependencies between exchanges, asset classes, and national currencies, and thus contribute to the systemic or infrastructural nature of contemporary finance. In Section 4 I will explain this in more theoretical terms, but, first, in this section I offer some background on what financial derivatives are, and how they relate to risk management, marketization, and liquidity.

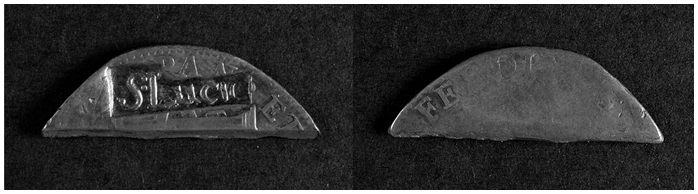

Derivatives enabled new marketized spaces long before anyone referred to financialization. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the development of agricultural futures markets (the direct ancestors of financial derivatives) in Chicago were co-constitutive with the emergence of telegraphs and railways and new semiotic systems for grading commodities (Carey, Reference Carey1992, pp. 201–230; Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2016, Reference Pinzur2021). These systems converged on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) where, after the US Civil War, the trade in grain futures contracts quickly outpaced the spot trade in physical grain. The futures market allowed the exchange of the potential costs and benefits of uncertainty related to grain before it was harvested from the soil. Whilst insurance contracts had existed for centuries by this time, this was one of the first examples of marketized risk management. In addition to allowing hedging and speculation on either side of the contract, the futures market also improved the quality of the underlying collateral for agricultural credit because it could be risk managed (Levy, Reference Levy2012). Another effect was an increase in liquidity by speeding up of the turnover time of agricultural capital (Henderson, Reference Henderson1999).

All of this led to a significant increase in speculative trading at the CBOT and other formal futures markets, and it was an important part of transforming the city of Chicago, along with its vast agricultural hinterland, into a capitalist commodification engine (Cronon, Reference Cronon1991). Along with the railways and telegraphs, the futures markets became crucial nineteenth-century infrastructure for an increasingly interconnected agro-capitalist national economy.

For the next hundred years formal derivatives trading was isolated within the agricultural, raw material, and energy sectors. But with the delinking of the US dollar from gold in 1971 the various market technologies and state regulatory apparatuses that were originally developed to trade agricultural derivatives were applied to financial instruments (Muellerleile, Reference Muellerleile2015). As the relatively ‘integrated monetary world space’ of Bretton Woods fell apart (Swyngedouw, Reference Swyngedouw, Danies and Lever1996, p. 150), banks and corporations found it more difficult to predict the future value of money. Increasing financial uncertainty then produced new demand for risk management instruments, and new opportunities for innovators who might develop them. During the 1970s and 1980s markets were developed for derivatives trading on foreign currencies, corporate and government debt, and corporate share indexes, to name just a few.

In 1975 the US Congress mandated that that the US stock market regulatory agency, the Securities and Exchange Commission, develop a ‘National Market System’ for the trading of securities. While there were competing motivations for the legislation in Congress and competing visions of the end product, almost everyone involved agreed that the securities markets were crucial for the ongoing development of the US economy, and that a key goal should be widening access to these markets for a broader array of American consumer-investors. Pardo-Guerra (Reference Pardo-Guerra2019, p. 268) characterizes this legislative-turned-socio-technical attempt to develop a national market society as infrastructural. In his telling, it was an attempt to construct a national scale ‘form of financialized kinship that established relations through a common infrastructure of participation’. Crucially though, this infrastructural market-making project was not limited to stock and bond markets, but soon included derivatives.

Derivatives markets differ in several ways from markets for underlying assets. The most obvious is that unlike asset markets, derivatives allow investors to realize gains and losses based on the fluctuating value of an asset without taking ownership of that asset. More importantly for this discussion, derivatives can usually be traded with much higher levels of leverage than the underlying assets. Whereas one is able to buy many financial securities, such as equities or highly rated bonds, with an initial investment of 50%, it is common in derivatives markets to be allowed to hedge or speculate on the same assets by investing only 5% of their value (Muellerleile, Reference Muellerleile2015). This was the case in the 1980s when Chicagoans developed futures markets on corporate share indexes that were mainly traded on New York ‘spot’ markets. There was an extended regulatory struggle over the amount of leverage allowed in these early financial derivatives markets, but the high leverage argument won the day, as it did in most early derivative markets.

In October of 1987 the US equity markets dramatically crashed and much of the blame was directed at the highly leveraged derivatives markets in Chicago. While this was strongly contested by the Chicago derivatives traders, there is not space here to examine this in detail. I have argued elsewhere (Muellerleile, Reference Muellerleile2018), however, that the metaphor of roads and traffic, as an infrastructural system, is a useful way to understand how the highly leveraged Chicago-based derivatives markets built at first slow and clunky telephone connections to the New York securities spot markets in the early 1980s. In the aftermath of the crash – the markets were repaired with expanded capacity for information exchange between the two, in no small part as a result of direct intervention by US government regulators. Where there was once two separate but related markets, the rebuilding of those connections with the aid of much faster ‘info-structures’ (see Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen, and Porter, Reference Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen and Porter2019) created a newly integrated market system with an aggregate higher rate of leverage. As a result, this system become more, rather than less, dependent on maintaining market liquidity. This process of repair after 1987 was heavily influenced by the ongoing attempt to construct the US national market system.

Over the next twenty years, financial innovators developed both bespoke and standardized exchange-traded derivatives contracts on an endless assortment of financial assets. Not all of these developed into highly liquid markets, but what they all have in common is the capacity to draw risk management instruments, which are usually leveraged at a much higher rate, into direct relation with underlying asset markets.

The 2007–2009 GFC can be explained in many ways, but an important part of that explanation is the construction of new financial and informational interconnections based on turning relatively illiquid assets (homes) into liquid securities (Gotham, Reference Gotham2009). Through this came the production of new socio-technical time-spaces highly reliant upon the complicated but nevertheless systematic securitization of mortgages, derivatives on those mortgages, and derivatives of derivatives on those mortgages. The causal chain that led to the breakdown is not easily parsed, but a significant factor was the unsustainable amount of leverage produced in a now deeply interconnected system of layered and marketized optionality, all of which was based on an illusion that money and market liquidity would never run dry (Nesvetailova, Reference Nesvetailova2010).

This is not the place for a deep analysis of the GFC or the many fixes that were implemented in its wake. But it is worth considering that, similar to 1987, much of the discourse that framed the ‘problem’ of the GFC was one of liquidity, its lack, and its restoration (Langley Reference Langley2015). More radical solutions (e.g., prohibitions on derivatives) were pre-selected out because the terms of the debate were designed around restoring the techno-economic order of financial capitalist circulation and risk management. Put differently, the crisis was framed as a ‘socio-technical accident’, the solutions to which contributed to the ‘subordination of political calculation to financial power’ (Engelen et al, Reference Engelen, Ertürk, Froud, Johal, Leaver, Moran, Nilsson and Williams2011, p. 228). As such, the solution to the socio-technical problem was to repair the infrastructural breakdown, rather than ask if the infrastructure was actually serving the purposes it might have in a more equitable and less marketized world.

4 Risky Prices

A deeper understanding of the relationship between liquidity, economic interdependency, and derivatives requires separating the core functionality of derivatives from the process of derivatives trading.3 In the simplest terms, a derivative contract enables the transfer of risk between parties. Futures, options, and swaps set up a contractual obligation, usually to exchange a commodity or asset, or the difference in value of an asset over time, at an agreed date and price in the future.4 Buyers and sellers of derivatives may or may not have an interest in the underlying asset, and they may be attempting to hedge an existing risk or speculating by taking on more risk. Whatever the circumstance, in this basic form derivatives contracts have become an important part of risk management processes for both financial and non-financial actors and institutions. But this is only the beginning.

Derivatives have a second, more dynamic function related to their exchange, or when they enter into circulation. Because derivatives are based on the future value of an underlying asset, the prices that derivatives exchange at allow financial modellers to imply the present value of that underlying asset. The exchange of a derivative contract always includes an element of guesswork about an uncertain future. As such, when a derivative price is agreed upon in a trade, this price becomes new information about the value of the underlying asset. In other words, it makes a difference in the future market value of an asset, and thus it also makes a difference in the present (Ayache, Reference Ayache2010). Financiers and economists call this effect price ‘discovery’, and it is often cited as one of the main benefits of derivatives trading. In effect, what derivatives trading does is isolate and codify the uncertainty over the future value of an underlying asset. It formalizes this uncertainty, converts it to quantifiable risk, and enables its exchange independently of the asset itself. The capacity to use derivatives prices to evaluate underlying assets is one of the basic implications of the Black–Scholes derivatives pricing model developed in the early 1970s, and it is no coincidence that the popularity of derivatives expanded rapidly in its wake (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2006).

The formalization and marketization of uncertainty with derivatives is important for several reasons. First, increasingly more assets are held in institutional investment portfolios, and are thus subject to formal and continual evaluation and risk management processes. Derivatives allow portfolio managers to more effectively manage risk, and as such they enable portfolios to hold more risky assets. Secondly, by codifying and pricing risk, derivatives have made collateral (that which secures a loan) more liquid. There is a hierarchy of collateral with cash at the top because it is the most liquid asset. For non-cash collateral further down the hierarchy, a key measurement of quality is the option to sell it quickly at a known price (Krarup, Reference Krarup2019). Assets that have associated derivatives markets thus make for better collateral because liquid derivative contracts both allow for direct risk management through trading, and also continually provide real-time information about the value of the asset.

Mirowski (Reference Mirowski2010) argues that the emergence of marketized financial derivatives has facilitated the construction of a system of market computation. The interconnected system of financial markets reduces the complexity of individual instances of uncertainty into legibly priced and tradable securities and derivatives contracts. The problem is that at the collective level these markets are dissipative systems, meaning that they enhance entropy or create irreversible complexity. Crucially, this is not a problem as long as the markets consistently function as price mechanisms. However, if for any reason the market system overwhelms the computational capacity of any particular market mechanism and that market suddenly loses its capacity to price risk, the entire market system loses its capacity to translate – or compute – the messy complexities of its financialized subjects into prices. In other words, the highly complex system of contemporary financial markets are subject to what Mirowski calls inherent vice, or, like most other infrastructural systems, the inherent tendency to fall apart. Left unrepaired, they leave economic worlds more uncertain and complicated than they were to begin with. This is not to say these worlds could not be made less liquid or de-financialized, but that is rarely considered in any serious way by state technocrats. Rather, the solution to breakdown, or the threat of breakdown, is almost always to increase the capacity of the system, to enable faster circulation, to make it more liquid.

Of course, price is only one kind of information that is crucial to financial markets. Financial modellers constantly seek new information about the qualities of assets and to predict future value. The production, transmission, and consumption of that information is complex, contingent, and reliant on ‘long chains’ of information that are vulnerable to breaking down and in constant need of translation (Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen, and Porter, Reference Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen and Porter2019). Making this more complicated, access to prices and other market-related information, as well as humans and machines that can translate data and information between contexts, is a field of intense capitalist competition (Grote and Zook, Reference Grote and Zook2017; Grindsted, Reference Grindsted2022).

This competition becomes more consequential when we consider that at the same time that financial markets are in a constant state of calculation, price-making, breakdown, and repair, so is financialized time-space itself. Put differently, capitalist competition in the financial sphere both maps onto existing urban, regional, national, and international spaces, and produces new financialized time-space (Pryke, Reference Pryke, Martin and Pollard2017). Financial markets produce these new relational spaces, even though they are difficult to ‘see’. In fact, given the ‘unpredictable, intertwined, and relational’ nature of these space-times (Pryke, Reference Pryke, Martin and Pollard2017, p. 108), they often only become legible when they break down or when financial crisis hits (French, Leyshon, and Thrift, Reference French, Leyshon and Thrift2009). But when the market transactions that are an integral part of this circulation slow down or stop, the interconnections begin to change. In 2007, when US housing prices began to slump, the supply of mortgage-backed securities slowed and the future became more uncertain. The derivatives markets that were entangled with mortgage markets became more volatile, and eventually it became more difficult if not impossible to model the most complex contracts. Market liquidity then dried up. At that point, rather than a global space of capital flows, liquidity, risk management, and accumulation, these connections transformed into relations of localized place, illiquidity, incommensurability, foreclosure, and bankruptcy. This is how a group of small towns in northern Norway, who, under advisement of an Oslo-based firm, had invested (and lost) USD 78 million in a highly complex, New York-based mortgage securitization fund, could suddenly find itself unable to build the school and nursing home it planned because indebted home owners in Florida or Nevada could no longer make their mortgage payments (Aalbers, Reference Aalbers2009).

I am quickly skimming over the surface of highly complex relationships. Perhaps the town councils of northern Norway were defrauded. Perhaps they should have known better. The point I am making is that these global connections were enabled by the search for profit in the financial sector as well as the capacity of an integrated market system to simplify highly contingent and complicated economic relationships into relatively simple matters of prices, profits – and, eventually, losses. Making sense of this infrastructural system of finance, and ultimately developing alternative ways of organizing a post-financial capitalist economy, requires that we look closely at the socio-technical details of these systems, but it also requires a critical political economic lens, because what is increasingly apparent is that the ‘politics of liquidity is … at the core of how capitalist finance works’ (Konings and Adkins, Reference Konings and Adkins2022, p. 52).

5 Inverting Liquidity

So far I have explained how the circulation of financial derivatives has engendered interconnection in the financial market system, and how this has contributed to capitalist states turning their infrastructural gaze towards the financial sector, especially at times of breakdown. In this final section I turn to a more radical way to understand liquidity, and its absence, in financial markets and socio-economic relations more broadly. This begins by turning liquidity on its head. It begins with the assumption that financial markets are always in a state of disrepair, or put differently, always in a state of illiquidity. In other words, it begins by appreciating that the interconnection both within the financial market system, and between it and the broader capitalist economy, is perpetually wavering. If this is the starting point, it is easier to see that the socio-technical maintenance of the financial market system is not the exception, but the rule.

While not specifically concerned with finance, Bowker and Star (Reference Bowker and Star2000, pp. 33–50) referred to this kind of approach as ‘infrastructural inversion’. To invert infrastructure is to attend to the politics or economics of the opacity and technicity of infrastructure. It is to ask how the technical operation or mundanity of an infrastructural system is itself consequential. It is to take seriously the flaws of the infrastructural imaginary, or the assumption that infrastructural systems are by nature functionally neutral and fully operable for all of society, which, as many have pointed out, is rarely the case. The inversion foregrounds how infrastructure capitalizes on ‘porousness, incompleteness, and uneven accessibility’ (Langenohl, Reference Langenohl2020, p. 15), and in the process obscures inequality built into the infrastructure from the start.

Returning to liquidity in finance, to invert is to appreciate that financial markets mainly benefit the financial sector and the investor class, even if the credit the financial system distributes is crucial for social reproduction across class divides. It is to invert the idea that liquidity is the normal, stability-producing, ‘functional’ state of a financial market system, that liquidity is a technical prerequisite for the functioning of markets, and finally that illiquidity is a state of disrepair that should always be corrected by the state. In the words of Meister, it is to ‘transform the concept of financial market liquidity from an assumed precondition of capitalism to an object of political contestation’ (2021, p. x).

In a financial market, one key measure of liquidity or ‘market depth’ is the relationship between offers to buy and sell. This is the spread between the bid and ask prices. The most liquid or ‘deepest’ markets have the smallest spreads, the most pending orders awaiting execution, and the smallest price changes in the face of (large) buy or sell orders. In other words, liquid and deep markets are relatively orderly and stable in the face of changes to supply or demand, while illiquid and shallow markets are more volatile. But while liquidity implies relative stability, dealers, market makers, and other market intermediaries benefit from spreads because they constitute opportunities for arbitrage (buying at one price and simultaneously selling at another, and taking the difference as profit), or opportunities to appropriate a bit of the spread by facilitating an exchange between two other parties. As such, who benefits from the spread in various markets is an object of intense competition in finance.

Put differently, the spread represents the very necessity of the market to begin with. If there was no spread, supply and demand would be in equilibrium, there would be no need for negotiation, and no need for market makers. A condition of absolute liquidity is nonsensical in capitalism, as, amongst other things, it would mean that prices do not change over time or space, which implies zero market volatility and thus zero uncertainty. In this abstract condition there would be no need for derivatives because there would be no uncertainty regarding volatility or changing prices in the future.5

The more practical point is that liquidity is relative and relational, or in other words, market liquidity only matters in relation to market illiquidity. Market liquidity only matters in relation to what is exchanged, by whom, and at what speed. In terms of access to money, liquidity only matters in relation to a future where money can be exchanged for something less liquid.

Algorithmic and high-frequency trading (HFT) offer an extreme, but nevertheless helpful, example of this symbiosis of (il)liquidity. HFT is basically a method of high-speed arbitrage. Algorithms search for tiny spreads both within and between markets (e.g., a derivative and its underlying asset) and trade both sides to profit on the difference (see Grindsted, Reference Grindsted2022). Space is an important dynamic in HFT strategies. Trading firms invest capital to position their hardware at optimal locations in proximity to market order-book computers to gain nanosecond advantages. One result is that HFT deepens markets by adding a large number of bid and ask orders, and it increases liquidity by narrowing spreads through constant arbitrage. At the same time, HFT is so fast that it can jump the queue by reading the order book of waiting trades and executing in advance of slower traders (perhaps everyday investors) who then suffer a higher or lower price than expected (Grindsted, Reference Grindsted2022).

As such, HFT puts pressure on the capacity of the market system to process trades, which in the mundane can result in higher volatility and larger spreads, and in the extreme can result in a ‘flash crash’ like what happened in May of 2010 when the New York securities markets experienced about a 9% drop and recovery in value over a period of thirty minutes. Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen, and Porter (Reference Campbell-Verduyn, Goguen and Porter2019) explain this and other related crashes in terms of pressure on the capacity, and subsequent breakdown, of chains of information transmission, which is undoubtedly true. But we must also consider that the informational interconnection of financial actors, firms, and markets exemplified by HFT is part of a broader set of ‘relational spatial strategies’ that ‘convert distance and speed into trading advantage’ (Grindsted, Reference Grindsted2022, pp. 1391, 1393). In other words, there are incentives and rewards in the financial market system for interrupting market liquidity and/or producing relative illiquidity. This was true in the age of face-to-face trading, the age of telegraphs, and now in the digital age.

The point of discussing HFT is to demonstrate that access to liquidity is itself subject to the competitive dynamics of capital. Another way to think about this is that the dominant mode of managing uncertainty in contemporary capitalism is by accessing money liquidity and derivative risk management, but access to this ‘service’ is itself a profit-seeking dynamic of financialized capitalism (Konings and Adkins, Reference Konings and Adkins2022). The highly technical system of interconnected markets that is necessary to reproduce both risk management services as well as financial sector profitability, is, as the capitalist state sees it, infrastructure. And when the state repairs this vital system, it necessarily repairs marketized finance capital, including its capacity to reproduce socio-economic inequality.

This helps explain ongoing efforts to develop global-scale market infrastructures to manage climate-related uncertainty by converting it to financial risk (Bracking, Reference Bracking2019). The effects of climate change translate into a kind of radical uncertainty that modern institutions, including states, struggle to cope with. Within the bounds of capitalist ideology, the existing financial infrastructure is perhaps the only system capable of converting this climate-related uncertainty into both manageable risk as well as a profit-making opportunity. But again, for financial calculation to function as an effective climate-risk coping mechanism will rely on maintaining (il)liquidity, which is unlikely to succeed without significant state support for finance capital writ large.

Despite what may appear as an argument of inevitability, it does not need to be this way. And it is worth examining by way of a brief conclusion what would be necessary to disentangle state support for truly vital systems from state support for finance capital. The more precise question in my view is what would be necessary for a situation where the state could allow the financial markets to crash and some significant portion of financial capital to be destroyed without also destroying the lives of millions if not billions of common people?

The answer is implied in the first question – disentanglement – or more precisely de-financialization. Specifically, it would require removing or separating the crucial commodities of basic, everyday life from finance capital. The most obvious example is houses, but similar arguments could be made for health care, education fees, not to mention many of the objects of more conventional infrastructure like the provision of water and public transportation. Currently, at least in the USA and UK, many of these things are only available to most people via massive quantities of private and public debt. Servicing of this debt requires access to liquidity, which has become, in the words of Minsky, a basic ‘survival constraint’ (see Konings and Adkins, Reference Konings and Adkins2022). But if we learned anything from the GFC, capitalist states are rarely inclined to rescue indebted homeowners even when they are subject to predatory lending by finance capital. Rather than offering a liquidity rescue to individual borrowers, the state preferred to repair the financial infrastructure, perhaps in the flawed hope that the infrastructure would serve everyone equally.

Other than the accumulation of financial profit, what, after all, is the purpose of creating a market infrastructure of derivative optionality for homes? These are big questions, and there are no easy answers. Certainly, the politics of de-financialization will be messy to say the least. But if a larger proportion of homes, welfare services, and ‘real’ infrastructural systems like energy provision were ‘de-assetized’ and publicly owned, not only would there be less need for the perpetual option to convert them into cash, the financial sector would also shrink dramatically, making it less powerful and less dependent upon the state. Democratic society ought to have the power to provide some level of certainty for itself – a different kind of optionality – without relying on a financial sector that is both technically flawed and (infra)structurally dependent upon the state.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust and the Geography Department at Swansea University for funding the research included in this chapter. Thank you also to Andreas Langenohl for helpful suggestions on an earlier draft, and last but not least, Barbara Brandl, Malcolm Campbell-Verduyn, and Carola Westermeier for helpful suggestions, editorial guidance, and for organising several conference sessions where earlier drafts of this paper were presented. Any mistakes or omissions are my responsibility.

Since at least the pioneering work of Michel Callon in the 1990s, social scientists have attempted to understand markets as emerging from hybrid, socio-material processes. A vast body of work, using concepts such as actor-networks, socio-material assemblages, market devices, and market agencements has utilized a Callonian framework. Recently, another term with roots in science and technology studies (though not only in STS – see Coombs’ chapter, this volume) has found favour in the study of markets: infrastructure. Scholars use the term to refer to socio-technical ‘systems through which basic but crucial enabling functions are carried out, but that tend to be taken for granted and assumed’ (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019, p. 776). The concept has been applied to an array of elements – evidenced in the breadth of this volume – from barcode scanners and warehouses, to electronic order books and clearinghouses, payment systems and accounting schemes (Genito, Reference Genito2019; Kjellberg, Hagberg, and Cochoy, Reference Kjellberg, Hagberg, Cochoy, Kornberger, Bowker, Elyachar, Mennicken, Miller, Nucho and Pollock2019; Pardo-Guerra, Reference Pardo-Guerra2019; Banoub and Martin, Reference Banoub and Martin2020; Martinez, Pflueger, and Palermo, Reference Martinez, Pflueger and Palermo2022; Brandl and Dieterich, Reference Brandl and Dieterich2023).

Given their common roots in STS it is unsurprising to see similarities between the market infrastructure perspective and the Callonian view. Infrastructures, like devices and agencements, are held to be socio-materially hybrid assemblages or ecologies, featuring both ‘hardware’ and ‘software’: not just physical technologies, but organizational protocols, regulatory standards, and cultural ideas (Edwards, Reference Edwards, Misa, Brey and Feenberg2003). Also, they are similarly understood to ‘emerge’ or ‘occur’ through ongoing practice rather than to simply ‘exist’ as simple objects (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019). Finally, like agencements, infrastructures format the character and agency of the people and things that they encounter in the market (Pardo-Guerra, Reference Pardo-Guerra2019; Çalışkan, Reference Çalışkan2020). In the STS-inflected view, infrastructure, like agencement, is socio-material, performative, and locates ontology in a hybrid network.

These points of commonality have usefully allowed Callonian and infrastructural perspectives to develop in concert. But they have also made it possible to delay engagement with their differences. Beginning this engagement is the aim of this chapter. The chapter asks: Where does infrastructure sit in the Callonian framework on markets? How does scholarship on infrastructures prompt us to re-evaluate actor-network theory (ANT)-inspired work on market agencements? Does the Callonian perspective encompass market infrastructures and, if so, what is gained from an approach that pulls them out for special attention?

I argue that the focus on infrastructure highlights a pragmatically and phenomenologically important boundary elided in the Callonian perspective between components of an agencement that are physically and cognitively present to actors and those which – though critical to action – are not. This boundary in terms of presence is occasionally recognized, but never explicitly theorized, in Callon’s framework. Incorporating this boundary into a theoretical perspective on markets has two major benefits. First, it helps us to see a distinct form of ‘infrastructural power’ (Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2021) at work within market agencements. This power stems from the asymmetric relations of dependency and discretion that exist between the operators of infrastructures and their users. This asymmetry produces unequal dynamics around the alignment of framings in a market agencement that remain unspecified in Callon’s flat perspective. Secondly, this division draws attention to the unique features of the ‘boundary objects’ (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989) that flexibly connect components of agencements. These boundary objects, being vaguely structured at a general level yet adaptable to the particularities of local settings, help to resolve the ongoing struggle of holding together market agencements whose components are pulled in different directions. This concept, I argue, handles the problem of ‘multi-framing’ (Callon, Reference Callon2021) better than the established duality of framing and overflowing (Callon, Reference Callon1998a). By recognizing the boundary between infrastructures and other elements of agencements we thus become aware of underexplored dynamics within Callon’s perspective and gain tools with which to conceptualize these.

1 Callon and the Sociomaterial Turn in the Sociology of Markets

Use of actor-network theory to study markets heralded a sea change in economic sociology. Prior sociological work had conceptualized markets as institutionalized spaces featuring actors ‘embedded’ within, shaped, and constrained by a social context of laws and regulations, organizational rules, relationally enforced norms, and status hierarchies. By contrast, Callon, inspired by work on distributed cognition and action (Hutchins, Reference Hutchins1995), asked not how markets and economic actors were constrained, but how they were composed. The goal of his analysis was not ‘giving a soul back’ to Homo economicus (Callon, Reference Callon1998b, p. 51) by situating economic behaviour within a social context, but rather de-naturalizing the individual and the market, tracing how both took form through coordinated, distributed, materially mediated practices.

Key to this analysis have been the concepts of market devices and market agencements. The language of devices, defined as ‘material and discursive assemblages that intervene in the construction of markets’ (Muniesa, Millo, and Callon, Reference Muniesa, Millo and Callon2007, p. 2), featured in the earliest ANT-style economic analyses. The concept enabled scholars to look at the impact of distributed physical technologies and economic representations on market actors’ day-to-day work. More recently Callon and others have favoured the closely related term agencement (Çalışkan and Callon, Reference Çalışkan and Callon2010; Callon, Reference Callon2021). The move is more about emphasis than conceptual divergence. As opposed to the notion of a device with its suggestion of a thing to be picked up and used by a person, each distinct and whole, agencement emphasizes the ways that humans and material objects form unique, agentic networks. This highlights what Callon and others see as the ontological character of distributed action and cognition: distinct agencements do not just equip actors differently, they create hybrids with different loci and degrees of agency. It is in this sense that we can meaningfully talk about market actors that are individual, collective (‘the firm’s employees’), or even anonymous (‘market forces’), which operate with different forms of calculativeness (Callon, Reference Callon, Pinch and Swedberg2008).

Critically, market agencements do not form simply by accident: they are formulated with the precise goal of orienting collective action towards bilateral transactions (Callon, Reference Callon2021). Agencements organize five different ‘framings’ – producing active agencies, producing passive objects, arranging encounters between buyers and sellers, establishing prices, and maintaining the market – which together structure and coordinate economic action (Çalışkan and Callon, Reference Çalışkan and Callon2010; Callon, Reference Callon2021). These framings are themselves performative outcomes of materially mediated, distributed procedures variously described as qualification, singularization, pacification, and activization (Callon, Méadel, and Rabeharisoa, Reference Callon, Méadel and Rabeharisoa2002; Callon and Muniesa, Reference Callon and Muniesa2005). They are the constitutive, socio-material processes by which markets and economic actors are built up across networked environments.

A market agencement thus consists of networked humans and non-humans enacting the five framings that underpin bilateral transactions. While these framings in pursuit of a strategic goal allow us to define and delimit agencements conceptually, doing so empirically is more challenging. The breadth of individuals, technologies, and texts involved in these five framings is extraordinary. Just consider how many are involved in a single piece of any one framing, for example, the creation of advertisements that attach consumers to goods, the construction of industry standards that establish a legible price, the regulation of consumer safety by the state, and so on. But, more significantly for the topic at hand, agencements have depth. Çalışkan and Callon (Reference Çalışkan and Callon2010, p. 9) claim that ‘agencements denote socio-technical arrangements from the point view of their capacity to act’. But any given socio-technical arrangement’s ‘capacity to act’ is wrapped up in and dependent on further socio-technical arrangements: a trading desk in an investment bank, for example, operates in conjunction with organizational rules and processes, international law, undersea cables, and so on. Any single actor (human or non-human) making a trade is designated and empowered to act by virtue of their position within a agencement that includes screens displaying prices, analyses drafted and circulated within an organization, computer programs that synthesize massive amounts of data, statistical networks that produce this data in the first place, and so on. It is in this sense, quite true that ‘nothing is left outside agencements’ (Çalışkan and Callon, Reference Çalışkan and Callon2010, p. 9).

This capaciousness helpfully demonstrates the massive effort behind every market transaction. But it also tends to efface an important pragmatic and phenomenological boundary between those actors, devices, and representations actively invoked, referenced, or manipulated in the everyday conduct of market action and those that – while crucial to the success of the agencement – remain hidden, inaccessible, and unmanipulated. This distinction and boundary, though unnamed and unspecified, is clear in prior ANT-inspired work. On one hand we see devices that gain value precisely through their components materially intervening in the strategy, calculation, and perception of transacting parties. Such devices are often appended with the particular actions they enhance or contribute to: they are ‘optical devices’ or ‘evaluative devices’ (Beunza and Stark, Reference Beunza and Stark2004), ‘calculative device[s]’ (Callon and Muniesa, Reference Callon and Muniesa2005). They are actively and creatively engaged by individuals as aids in the market (Knorr Cetina, Reference Knorr Cetina2003; Preda, Reference Preda2006). On the other hand are devices that support or prepare the ground for these: not the FICO (Fair Isaac Corporation) score, but the ‘scorecard’ that brings together the relevant data points; not the marketing materials, but the focus group that generates knowledge of consumers; not the derivative instrument, but the regulatory distinctions and accounting techniques that permit its construction (Muniesa, Millo, and Callon, Reference Muniesa, Millo and Callon2007). These devices (which some scholars might later call infrastructures) come to matter in their ability to produce a taken-for-granted baseline from which actors can use another ready-to-hand set of objects to calculate, act, and trade. While Callon would certainly recognize that market actors relate to these objects and processes in different ways – some with intense focus, others as a taken-for-granted background – the notion of agencement offers no way to theorize the importance of this difference. Conversely, this distinction is precisely what infrastructure makes visible and theorizes.

2 Infrastructure as Absence

I describe the distinction between the infrastructural and non-infrastructural components of an agencement as a difference in ‘presence’. Viewed phenomenologically from the angle of a transaction, infrastructures matter in a different way than ready-to-hand devices like screens, reports, or analytics: they are neither present nor accessible, cannot be manipulated, are not active and lively intervening components. Rather than remaining at the surface of action, they become deeply embedded in organizational routines and bureaucracies. Functioning infrastructures tend towards invisibility; they ‘seamlessly fade into the background as if natural elements of our human environments’ (Pardo-Guerra, Reference Pardo-Guerra2019, p. 7). This backgroundedness – the possibility of forgetting that these technologies, organized practices, and rules even exist at all – is precisely what makes market infrastructures useful (Guseva and Rona-Tas, Reference Guseva and Rona-Tas2014). They allow actors to marshal ready-to-hand devices in pursuit of profit on the assumption that most, if not all, of the other components of a market agencement are properly aligned. Infrastructure’s cognitive absence to market actors is a crucial ingredient in producing a calculable and actionable environment.

The cognitive presence or absence of devices is often accompanied by their physical presence or absence as well. Those devices that are actively manipulated for calculation tend to be more contained in space and time, assembled by an organization for its own distinct purposes, affording market actors a greater plasticity. For instance, new market analyses are produced daily using proprietary software and trading algorithms are tweaked constantly over the course of their short lives to reflect and accommodate changing market circumstances (Beunza and Stark, Reference Beunza and Stark2012; Borch and Lange, Reference Borch and Lange2017). Similarly, the customizability of trading desks – with more or fewer screens, displaying different types of information – demonstrates the value of this device as a physical aid to local, embodied calculation and action (Beunza and Stark, Reference Beunza and Stark2004; Beunza, Hardie, and MacKenzie, Reference Beunza, Hardie and MacKenzie2006). The aim is precisely for these devices to differ from those being used by competitors, so as to manufacture unique profit-making opportunities (Erturk et al., Reference Erturk, Froud, Johal, Leaver and Williams2013; Hardin and Rottinghaus, Reference Hardin and Rottinghaus2015).

By contrast, infrastructures tend to span multiple sites or events (Edwards, Reference Edwards, Misa, Brey and Feenberg2003; Silvast and Virtanen, Reference Silvast and Virtanen2019). This can be a physical spanning of distance via information and communication technologies (e.g., sub-marine cables or satellite networks) or an administrative harmonization via standards, classifications, and protocols (Bowker and Star, Reference Bowker and Star2000; Guseva and Rona-Tas, Reference Guseva and Rona-Tas2014; Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2016). This broader scope coordinates action across distant settings, creating a situation where ‘local practices are afforded by a larger-scale technology’ (Star and Ruhleder, Reference Star and Ruhleder1996, p. 114). The politics and uneven impacts of this relation between the global and local is why payment, settlement, and clearing systems have attracted so much attention from infrastructural scholars. Infrastructures including the European interbank payment system (Jeffs, Reference Jeffs2008), the European Union’s Target 2 securities settlement infrastructure (Krarup, this volume), and the SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) financial messaging system (Robinson, Dörry, and Derudder, this volume) all show the tricky questions and tough relationships that characterize infrastructures that span these scales.

3 Issues at the Boundary

Summing up the previous section, we see that scholarship on market infrastructures distinguishes within market agencements between elements that are physically and cognitively present to actors and those that – while critical to action – are not. This distinction is elided in Callon’s presentation of market agencements. But why does this boundary matter? What does it help us to see or understand more clearly?

The following sections argue that this boundary helps us to recognize and theorize two important, understudied dynamics within agencements. First, this boundary aligns with an asymmetry in market agencements: local, ready-to-hand devices depend on the smooth operation of broader infrastructures, but the opposite is not true. That is, the impact of infrastructures in (mis)aligning the components of an agencement far exceeds that of local devices. This asymmetry translates into a distinct form of ‘infrastructural power’ (Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2021) accruing to actors with discretion to enable or disrupt everyday routines for a wide swathe of the market. Secondly, this boundary draws attention to a different view of how to maintain cohesive agencements despite the inevitably multiple ways in which objects and activities are framed by distinct actors. Where Callon sees this ‘multi-framing’ as an ever-present source of overflowing to be contained and reframed, infrastructural scholarship suggests a more flexible approach. The concept of ‘boundary objects’ (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989) – artefacts, concepts, or methods that simultaneously retain a general, shared form and can be adapted to divergent particular applications – offers a tool with which to rethink the nature of alignment and misalignment, making ubiquitous multi-framing less of a threat to market action.

4 Asymmetry, Discretion, and Infrastructural Power

As discussed, Callon argues that market agencements are held together through the alignment of framings across actors and environments, collectively organizing action towards the single goal of bilateral transactions. In treating these myriad framings at the level of the collective (i.e., what matters is that the whole agencement stays aligned) Callon does not discuss the differential roles that individual acts of framing might play. But, in fact, when we consider the divide between local devices and global infrastructures – the components that are cognitively and physically ready to hand in everyday action versus those that support action, but are not present in the same way – it becomes clear that not all framings performed by every component of an agencement are equal. In fact, the framings accomplished by infrastructures are asymmetrically more important.

This, of course, is not to say that changes or struggles over smaller components of an agencement are necessarily inconsequential. Any set of framings that breaks out of line – whether related to a focus group, a stock index, a computer screen, or any other market device – initiates a struggle to re-establish alignment. The result may be bringing the offending framing back in line or it may lead other components of an agencement to change themselves. Donald MacKenzie’s analysis of high-frequency trading offers a fascinating version of just such an analysis. MacKenzie traces the back-and-forth development across the fields of trading, exchange, regulation, and politics, where alterations of the market agencement in one area (e.g., new rules around Nasdaq’s Small Order Execution System) provoke responses in another (e.g., development of ATD’s (Automated Trading Desk’s) trading algorithms or Island’s open order book), which redound on yet another (e.g., moving from fixed role to all-to-all markets), and so on (MacKenzie et al., Reference MacKenzie, Beunza, Millo and Pardo-Guerra2012; MacKenzie and Pardo-Guerra, Reference MacKenzie and Pardo-Guerra2014; MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2018, Reference MacKenzie2021). This is a history of local instances of bricolage, innovation, and opportunism: a large-scale shift in agencement built up from successive breakdowns and realignments of framings.

But the case of HFT also shows us the limits of this symmetrical analysis. MacKenzie (Reference MacKenzie2018) notes that the most important ongoing relation in this case is the mutuality established between exchanges and trading firms. Today the most important alterations in framing involve exchanges developing HFT-friendly infrastructures – for example, co-location, ultrafast matching engines, rebates for market makers – in an effort to attract liquidity. There is a feedback effect: exchanges that offer the most enticing infrastructures attract more trading, which makes them more liquid, which makes them even more appealing sites for trading. The competition among exchanges to provide infrastructure has become the core of their business, extending beyond HFT to the provision of indexes, clearing services, trading platforms, and more (Petry, this volume). Critically, while exchanges and firms both rely on each other, this dynamic is not symmetrical. As access to top-notch infrastructure becomes a necessity for firms – both for the liquidity and the competitive advantage it provides – global exchange groups grow larger, wealthier, and more influential.

Drawing a distinction between infrastructures and ready-to-hand devices highlights an important divide in how alignment translates into power and influence. There is an asymmetry in dependency – devices need infrastructures to work, but not the other way around – which translates into an imbalance in the scale of disruption that would result from any changes to framings or stoppages of work. How many devices, or components of an agencement, would become inoperable – and thus quite radically ‘unaligned’ – if a particular infrastructure was not working as usual? How many things would become impossible to do or think as a result? Because of their global scope, their general invisibility, and their efficient handling of basic functions, infrastructures become enmeshed in and critical to vast numbers of market processes. A change in or breakdown of infrastructure thus means an immediate and profound misalignment across myriad market actors. This asymmetric interdependency offers a mechanism by which infrastructural actors, through their discretion to upset alignments of many framings at once, can exert outsized power and influence.

Elsewhere (Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2021) I have referred to this as ‘infrastructural power’ (drawing out its connections to, but possibly also confusing with, the tradition from political economy, see Coombs, this volume). This outsized power is held by actors with discretion to disturb the smooth functioning of a market infrastructure, in the process provoking leveraged misalignments with a large number of local, device-mediated calculations and actions. For instance, nineteenth-century American commodity exchanges used their positions within key infrastructural processes to exert influence over the form of crop-statistic and price-quotation networks – core aspects of the five framings (Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2021). In other instances, we see that power comes from the discretion to control access to an infrastructure. This is the power of the global exchange group wielding exclusive control over a set of goods and services whose absence would cause a crisis of misalignment for traders (Petry, this volume). It is also the power, exceptionally applied, of saboteurs (e.g., protesters clogging the streets of Frankfurt to keep bank employees from reaching their desks) or natural disasters (e.g., Hurricane Sandy knocking out elements of global financial infrastructure) (Folkers, Reference Folkers2017).

As discussed, though Callon recognizes the diversity of relations between market actors and the various components of market agencements – for example, that focus groups are core work for marketers but simply one bit of information for executives planning a branding campaign – he does not theorize these distinct types of relations. This leaves his view of an undifferentiated, flat agencement ill-equipped to account for shifting scales of alignment and the imbalances of power these asymmetries create. By contrast, recognizing the boundary between hidden infrastructures and ready-to-hand devices highlights the unique form of ‘infrastructural power’ and leveraged misalignment that exist within a single market agencement.

5 Alignment, Multi-framing, and Boundary Objects

The previous section considered the issue of how to align multiple components – objects, practices, discourses, people – within a single agencement. But Callon also notes the additional challenge that any single component may become entangled in several, distinct framings or agencements at once: Callon calls this being ‘multi-framed’ (Callon, Reference Callon2021, p. 366). This multi-framing creates a local tension – keeping an agencement aligned even when many of its components are pulled in several directions at once – for which Callon, admittedly, has no general solution. I argue that an infrastructural perspective using the concept of ‘boundary objects’ (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989) offers traction on this issue.

Multi-framing occurs in settings where multiple agencements overlap. Take, for example, a university’s scientific research laboratories. In such an environment components may simultaneously be framed with a market agencement (e.g., making genetic material patentable intellectual property that can be bought and sold), a scientific agencement (e.g., making genetic material a resource to be made widely available for basic research through collaborative networks), or even a religious agencement (e.g., making genetic material a divine substance that ought not be manipulated). The economic challenge of a multi-framed object is ensuring that it is not pulled so far out of its framing within a market agencement that it becomes untradeable or disorders collective action in the market. For example, regulators can influence the format and framing of credit scores (e.g., banning the use of particular types of personal information), but only if they do not disturb the score’s role within the market agencement that promotes and sustains lending. This produces conflicts over framing that must be resolved locally.

Callon cautions against thinking that such conflicts are rare. Given the inherent openness of agencements and their components, multi-framing is, in fact, widespread. While we can certainly associate components to a market agencement by their participation in the five framings, ‘we should not forget that each site and activity is also caught up, at the same time, in other collective actions, in other types of agencements’ (Callon, Reference Callon2021, p. 366). In each of their components and sites, market agencements grapple with other modes of agencement. In fact, multi-framing is so pervasive that the work of ensuring objects, people, and activities maintain their roles in markets despite being caught up in various non-market agencements is the core of market maintenance. And yet, despite the near ubiquity of this phenomenon, how this resolution occurs is a mystery. In response to the question of how these opposed tendencies are made compatible, Callon admits that ‘there is, as far as I know, no satisfying answer to this question’ (Callon, Reference Callon2021, p. 368, emphasis added).

I suggest that Callon and other economic sociologists can find one ‘satisfying answer’ in the literature on infrastructure, particularly in the concept of ‘boundary objects’ (Bowker et al., Reference Bowker, Timmermans, Clarke and Balka2016). In contrast to Star’s concept of infrastructures, which has been eagerly adopted in the study of markets, this popular and closely related notion has not yet been taken up. The key feature of a boundary object is that it spans multiple groups and environments, both enabling collaboration and coordination across these and being adaptable to dissimilar uses in their various settings. Their defining feature is their ‘interpretive flexibility’, the ability to toggle between being vaguely structured at the general level and precisely structured in particular settings (Star, Reference Star2010). Boundary objects ‘are both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and the constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites. … They have different meanings in different social worlds but their structure is common enough to more than one world to make them recognizable, a means of translation’ (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989, p. 393). They can take multiple forms: artefacts (e.g., repositories, indexes), concepts (e.g., ideal types, classes), or methods (e.g., standardized forms) (Star, Reference Star2010). For instance, Star and Griesemer (Reference Star and Griesemer1989) show that animal and plant specimens, field notes, and maps served as boundary objects in the scientific practice of a natural history museum, allowing collaboration among academics, volunteer trackers, animal trappers, and donors despite their divergent concerns, practices, and conceptions.

While research on markets has not invoked boundary objects explicitly (Millo and MacKenzie, Reference Millo and MacKenzie2009, is an exception), I would argue that prior research has used the concept implicitly. Consider, for example, work on derivative-trading investment banks and clearinghouses, two organizations whose actions must be aligned so as to promote transactions, yet which frame these transactions’ elements in starkly different ways. Scholars have identified several boundary objects at work in this coordination. The first of these is the derivative itself. While the derivative maintains a single, general identity in both environments (i.e., actors can agree on its identity, differentiate it from other derivatives), at the level of practice banks and clearinghouses decompose the same complex derivative transaction differently to suit their own local needs and purposes (Millo et al., Reference Millo, Muniesa, Panourgias and Scott2005; Genito, Reference Genito2019). Financial risk-management techniques are another boundary object, enabling communication and coordination among trading firms, clearinghouses, and regulatory bodies, yet being differentially incorporated into their particular workings. Financial theories operate as ‘a “plastic” medium … able to accommodate different practices while allowing awareness about the common elements of the practices to evolve and strengthen the connections among the actors’ (Millo and MacKenzie, Reference Millo and MacKenzie2009, p. 651). This sort of relation between infrastructures, devices, and boundary objects can even be seen within investment banks. Front-office and back-office divisions may treat a given security as a single, general object in their communication with one another, yet handle it in dissimilar and sometimes incompatible ways in their day-to-day work (Muniesa et al., Reference Muniesa, Chabert, Ducrocq-Grondin and Scott2011). These boundary objects, sitting at the interface of different components within an agencement, enable distinct groups pursuing divergent concerns to nonetheless collaborate in pursuit of an overarching goal.

Boundary objects thus offer a way of understanding how cohesively aligned market agencements can be maintained despite the (possibly conflicting) multi-framings of their various components. Notably, the concept also offers greater flexibility than the pairing of framing and overflowing, the current means by which Callon attempts to understand components’ entanglement in different agencements. Framing and overflowing are metaphors of containment, struggle, and rigidity: one must ensure that one’s own framings are not overflowed, prevent key elements of one’s environment from being co-opted into other frames, and force alignment across the multiple components of a market agencement (Callon, Reference Callon1998a). Boundary objects, by contrast, suggest a dynamic of flexible cooperation, where important elements are able not only to exist simultaneously within multiple framings but to be simultaneously aligned with multiple framings. Boundary objects thus are not only multi-framed, but can be ‘multi-aligned’.