Volunteer travel opportunities are more plentiful than ever and are now offered worldwide, with conservation projects being an increasingly popular choice. Volunteer travelers are “tourists who volunteer in an organized way to undertake holidays” (Wearing Reference Wearing2001, p. 1). Among many projects such as alleviating the material poverty of some groups in society, community development, and research into aspects of society are projects focused on rehabilitation of endangered ecosystems and research or habitat development that contributes to long-term nature conservation goals. Lorimer (Reference Lorimer2009) identifies conservation volunteers as those people who travel from their home country to help support wildlife conservation, research, and rehabilitation projects—both in situ and ex situ. While the exact size of the international conservation volunteer market is not known, ninety percent of conservation funding originates and is spent in economically rich countries (Brooks et al. Reference Brooks, Mittermeier, da Fonseca, Gerlach, Hoffmann and Lamoreux2006), and hence one would expect these countries constitute the largest percentage of the conservation volunteer market as well. Some conclusions about the size of the Western market could drown from British and US markets. In US, in 2014, the size of the conservation volunteering market constituted only 2.6% of the total market (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014), whereas in Great Britain as Lorimer (Reference Lorimer2009) notes conservation volunteering does contribute to international conservation but “is not a panacea for comprehensive efforts to protect threatened biodiversity.”

Some of the emerging questions in this field are concerned with the effective communication of these opportunities to young people. Conservation projects are a potentially hard sell, especially when young adults are asked to pay for participation in conservation volunteering opportunities offered in remote rural areas with poor infrastructure. While these volunteers are commonly passionate about the environment and want help conserve endangered ecosystems (Schattle Reference Schattle2008; Lorimer Reference Lorimer2010), some may additionally seek emotional adventure and excitement (Alba and Williams Reference Alba and Williams2013). A better understanding of these various motives would enable organizations to create campaigns that successfully engage young adults in nature conservation projects. In response to this need, this study seeks to examine if persuasive message type is an important characteristic in appealing to the potential traveler.

While examining motivation to participate in conservation volunteer travel has been examined via a number of theoretical perspectives, the current study utilizes regulatory focus theory. The theory suggests that when using persuasive messages, it is critical to consider the state of mind a person is in (prevention/promotion) and whether the message fits that state of mind. Those in a prevention focus prefer to think about a goal with a loss/nonloss mindset. In contrast, those in a promotion focus have a gain/nongain mentality. This theory is useful in guiding the creation of persuasive campaigns for conservation volunteering because it examines the impact of both the optimistic and pessimistic messaging strategies used in environmental messaging. Moreover, it is a theory used in marketing and advertising research, thus creating a collaborative link between environmental tourism and marketing research. By adopting regulatory focus theory, we reveal yet another possibility for conservation volunteer motivations and its implications for promotional messages for conservation volunteer travel.

Precisely, we seek to learn which types of messages are more effective to market conservation volunteering travel. Will messages focusing on the self-promotion and the unique experience of conservation volunteer be more effective than those calling for the prevention environmental degradation? Will environmental attitudes affect the individual reactions to promotion messages? These questions are important for a number of reasons. First, while prevention and promotion messages have been shown to be applicable to public relations or marketing practice and research (e.g., Avnet and Higgins Reference Avnet and Higgins2006; Kareklas et al. Reference Kareklas, Carlson and Muehling2012), a gap in knowledge exists about the appeal of prevention/promotion messages to young adults and their power to engage them in travel behaviors such as conservation volunteering. Second, further explication of the impact of promotional persuasive tools on involvement in this activity is needed (e.g., Coghlan Reference Coghlan2007; Simpson Reference Simpson2004). Finally, if environmental attitudes affect reception of promotion messages concerning conservation volunteering, this needs to be taken into consideration while creating promotional campaigns for this type of travel.

We intentionally focused this study on Millennials (aging from approximately 17 to 35 years) whose exposure, personally or via media, to ecological devastation and natural disasters has become an essential part of this generation’s environmental consciousness (McKay Reference McKay2010) and turn toward more ethical consumption (Bucic et al. Reference Bucic, Harris and Arli2012). It has affected their environmental attitudes and triggered an urge to more ethical behavior (McKay Reference McKay2010; Bucic et al. Reference Bucic, Harris and Arli2012). Unlike older generations, Millennials appear to be the most environmentally conscious consumers (Smith and Miller Reference Smith and Miller2011; Vermillion and Peart Reference Vermillion and Peart2010; Bucic et al. Reference Bucic, Harris and Arli2012). This environmental consciousness is likely to trigger pro-environmental behaviors, such as participation in nature conservation projects (e.g., Stern Reference Stern2000).

On the other hand, Wismayer (Reference Wismayer2014) stresses Millennials tendency toward self-absorption. Out for the ultimate adventure and the selfie to go with it, they are becoming synonymous with travel for the sake of saying they have been somewhere and the ability to one-up their peers (Wismayer Reference Wismayer2014). Moreover, Millennials tend to travel for extended periods, visit remote locations, seek enlightening experiences, and travel regardless of economic means (Machado Reference Machado2014). This is not to argue that Millennials would not seek volunteer travel opportunities. On the contrary, as Malone et al. (Reference Malone, McCabe and Smith2014) suggestion, a quest for positive emotions—and specifically hedonic experiences—can reinforce the informed ethical tourism choices within this group. Opportunities such as conservation volunteering may appeal to their ‘you only live once’ (‘YOLO’) mentality and can reward travelers with a tremendous amount of bragging rights. This study contributes to the better understanding of Millennial volunteer travel by exploring how they adhere to regulatory focus in reception of messages promoting conservation projects.

Regulatory Focus

Regulatory focus theory is concerned with matching goal orientation and goal achievement with psychological state (Higgins Reference Higgins1997, Reference Higgins2000). Working from self-discrepancy as a theoretical platform, regulatory focus takes into consideration a person’s idealistic desires and dutiful obligations (Higgins Reference Higgins1997). Specifically, when concerned with either seeking a goal or fulfilling an obligation, people tend to fall into a state of regulatory focus (Higgins Reference Higgins1997). More specifically, promotion focus is concerned with “gain/nongain outcomes” and prevention focus is concerned with “nonloss/loss outcomes” (Cesario et al. Reference Cesario, Grant and Higgins2004, p. 389). In the context of volunteer travel, a promotion message may focus on gaining a sense of accomplishment from helping an ecosystem. A prevention message, on the other hand, may focus on the duty of care we have toward the environment in order to avert ecological loss. The notion of regulatory fit is accomplished when people match goal orientation and goal achievement (Higgins Reference Higgins2000) and assumes people who are interested and more motivated to fulfill goals when fit is present (Higgins Reference Higgins2000; Shah et al. Reference Shah, Higgins and Friedman1998). In other words, those individuals with a prevention focus feel better about conceptualizing a goal through loss/nonloss means, whereas a promotion-focused individual prefers thinking in gain/nongain means.

When using regulatory fit in persuasive messages, it is important to consider a person’s state of mind and whether a message fits that state of mind. People with a prevention focus tend to be more negative and concerned with preventing loss (Markman et al. Reference Markman, McMullen, Elizaga and Mizoguchi2006). In contrast, people with a promotion focus tend to be more positive and concerned with idealistic achievement. Past research found messages utilizing regulatory fit resulted in people feeling better about the decisions they made with regard to the message topic (Higgins Reference Higgins2000; Vaughn et al. Reference Vaughn, O’Rourke, Schwartz, Malik, Petkova and Trudeau2005).

The mechanism of regulatory fit has been used in the processing of advertising messaging in terms of gain/loss, analytical/imagery, and cognitive/affective message attributes (Roy and Phau Reference Roy and Phau2014; Cornelis et al. Reference Cornelis, Adams and Cauberghe2012; Florack and Scarabis Reference Florack and Scarabis2006; Park and Morton Reference Park and Morton2015; Zhao and Pechmann Reference Zhao and Pechmann2007). While regulatory fit theory has been also applied within environmental marketing (Bullard and Manchanda Reference Bullard and Manchanda2013; Kareklas et al. Reference Kareklas, Carlson and Muehling2012), its usage to test environmental advertising has been limited (e.g., Ku et al. Reference Ku, Kuo, Wu and Wu2013; Roy and Phau Reference Roy and Phau2014). For instance when examining green versus non-green advertising, Ku et al. (Reference Ku, Kuo, Wu and Wu2013) found green product messages were perceived as more persuasive by those with a prevention focus than those with a promotion focus. However, in another study, green messages were perceived as more persuasive than non-green messages by both prevention- and promotion-focused individuals (Bullard and Manchanda Reference Bullard and Manchanda2013). In other words, green messages were better perceived regardless of an individual’s regulatory focus (Bullard and Manchanda Reference Bullard and Manchanda2013). Similarly, Cornelis et al (Reference Cornelis, Adams and Cauberghe2012) research delivered mixed results. Namely, in the case of a rational ad, regulatory congruence (vs. incongruence) effects were found only for prevention-focused people, whereas in the case of an emotional ad, regulatory incongruence (vs. congruence) effects were found only for promotion-focused people.

While it is neither clear nor conclusive why results vary when applying regulatory focus to an environmental context, the overall evidence suggests that promotion-focused individuals should respond better to the messages promoting pro-environmental behaviors. We proposed that for promoting conservation volunteer travel, persons in a promotion focus will better receive of a promotion-based message. In this case, a message touting the benefits of biodiversity, empowering communities, and self-fulfillment should be received better by those in a promotion focus. Thus it is predicted:

H1

For the promotion-focused experimental group, the promotion message will be perceived as (a) more persuasive, (b) less threatening, and (c) increase behavioral intentions compared to the prevention message.

In terms of conservation volunteer travel, persuasive messages focusing on the preventing environmental damage, and biodiversity preservation should work better on those in a prevention focus. Given the inconsistent results from environmental advertising research, the proposed hypothesis is derived directly from the theory rather than from the past studies. Thus, it is predicted:

H2

For the prevention-focused experimental group, the prevention message will be perceived as (a) more persuasive, (b) less threatening, and (c) increase behavioral intentions compared to the promotion message.

Conservation Volunteering

Regulatory focus theory provides an interesting and previously untested framework to examine Millenials’ responses to persuasive conservation volunteering messages designed to match prevention/promotion focus. While theoretical guidance is useful to understand values and beliefs underlying Millenials motivations to volunteer, past studies identified various types of volunteer motives simply by asking volunteers. This approach resulted in a few competing classifications of volunteers. Callanan and Thomas (Reference Callanan, Thomas and Novelli2005), for example, distinguished between shallow (in pursuit of personal interests), intermediate, and deep volunteers based on location, project duration, focus (self-interest/altruistic), qualifications, active/passive participation, and contribution to local community. In an attempt to further clarify volunteers’ motivations, (Benson and Seibert Reference Benson and Seibert2011) pointed out five essential drives: experience of something different/new, meeting international volunteers, learning about countries/cultures, living experience in another country, and mind-opening experience. This distinction between shallow, intermediate, and deep volunteers (Callanan and Thomas Reference Callanan, Thomas and Novelli2005) is of interest to organizations coordinating volunteer travel. Smillie (Reference Smillie1995) for instance found that for-profit organizations prefer to engage with shallow volunteers, while non-profits favor deep volunteers. Continuing this line of reasoning, Wymer et al. (Reference Wymer, Self and Findley2010) distinguished two major contemporary volunteer target markets for these organizations: volunteers who are considerate of the community they visit and sensation-seeking volunteer tourists who focus on their own experiences. In an attempt to increase the understanding of the specific factors linked to participation in conservation volunteerism, Eagles and Higgins (Reference Eagles, Higgins, Lindberg, Wood and Engeldrum1998) proposed that environmental attitudes affect individual’s willingness to engage in nature through conservation volunteering.

One of the first and the most influential environmental theories focused on environmental attitudes is the new environmental paradigm (NEP) (Dunlap and Van Liere Reference Dunlap and Van Liere1978). It posits people to hold a multitude of views about their rights to control nature, capability to affect it, and planetary boundaries. These views are changing as people learn more about nature (Dunlap and Van Liere Reference Dunlap and Van Liere1978; Dunlap et al. Reference Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig and Jones2000). In order to measure these changing attitudes, Dunlap and Van Liere (Reference Dunlap and Van Liere1978) developed the NEP scale.

Past research has applied the NEP scale mainly to predict various pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., Eagles and Higgins Reference Eagles, Higgins, Lindberg, Wood and Engeldrum1998; Luo and Jinyang Reference Luo and Jinyang2008; Sampaio et al. Reference Sampaio, Rhodri and Font2012). For instance, Eagles and Higgins (Reference Eagles, Higgins, Lindberg, Wood and Engeldrum1998) demonstrated positive association between pro-environmental attitudes and one’s engagement in pro-environmental behaviors. In a business context, Sampaio et al. (Reference Sampaio, Rhodri and Font2012) examined how environmental attitudes affect a business organizations’ commitment to environmental solutions. Notably, environmental attitudes appear to affect businesses’ selection of practices and sensitivity to environmental issues.

In one of the first studies employing the NEP theory to tourism and recreation field, Dunlap and Heffernan (Reference Dunlap and Heffernan1975) looked at links between type of recreational activity and individual environmental attitudes. They found that those who partake in outdoors recreation are likely to be more concerned about the natural environment. Later, Teisl and O’Brien (Reference Teisl and O’Brien2003) added that those who participate in an appreciative recreation activity such as wildlife watching are also more likely to show other environmentally friendly behaviors. This hypothetical link between these types of recreational activities and pro-environmental behavior is precisely why Wearing et al. (Reference Wearing, Cynn, Ponting and McDonald2002) examined eco-friendly tourism consumption in a greater detail. Their study confirms a positive correlation between pro-environmental attitudes and more environmentally friendly recreation and tourism. In conclusion, much of the past research suggests that environmental attitudes affect people’s intentions to participate in pro-environmental activities; more precisely, these attitudes affect individual’s choice of travel and recreation.

Despite a number of studies concerning volunteers’ motivations (e.g., Galley and Clifton Reference Galley and Clifton2004; Brown and Lehto Reference Brown and Lehto2005; Campbell and Smith Reference Campbell and Smith2006), a gap in knowledge remains about the relationships between environmental attitudes and participation in conservation volunteering. Support from Millenials is a necessity, and knowing how this generation responds to persuasive marketing messages is key issue. In an attempt to increase the understanding of the effects of promotion/prevention-focused persuasive messages promoting conservation volunteering, this study seeks to answer the following research question:

RQ1

Will existing environmental attitudes influence promotion versus prevention message reception?

Ethical consumption in tourism is another pertinent and yet understudied issue in contemporary travel and tourism extensively discussed by Malone et al. (Reference Malone, McCabe and Smith2014), who argue that emotional travel experiences inspire consumers to making more ethical travel choices. While this is consistent with earlier findings about travelers’ desires to enhance their own personal wellbeing through engagement in volunteering (e.g., Brown and Lehto Reference Brown and Lehto2005; Campbell & Smith Reference Campbell and Smith2006; Lepp Reference Lepp, Lyons and Wearing2008; Rehberg Reference Rehberg2005; Andereck et al. Reference Andereck, McGehee, Lee and Clemmons2012), Malone et al. (Reference Malone, McCabe and Smith2014) additionally emphasize hedonic experiences generate emotional responses that reinforce ethical types of tourism. Their approach is derived from Holbrook and Hirschman (Reference Holbrook and Hirschman1982) framework for hedonic experiences—“multisensory, fantasy, and emotive aspects of one’s experience with products” (p. 92). Holbrook and Hirschman (Reference Holbrook and Hirschman1982) make several propositions regarding hedonic consumption: emotional desires may dominate consumer choice; consumers ascribe a subjective meaning to products; hedonic consumption is linked to imaginative constructions of reality; and seeking sensory-emotive stimulation and seeking cognitive information are two independent dimensions.

Finding the hedonic value may also tap into the potential for promotion-focused messaging to work better compared to prevention-focused messaging. Prevention-focused environmental messages tend to focus on what we may lose with the destruction of ecosystems, while promotion-focused environmental messages can focus on what individuals can gain from conservation volunteering. It is theorized that, regardless of personal regulatory focus, promotion-focused messaging may work better because it captures the hedonic value sought by Millenials. In an attempt to increase the understanding effect of regulatory focus on perceived hedonic value of conservation volunteering, we ask the following research question:

RQ2

How will prevention versus promotion messages influence perceptions of hedonic and utility value?

Methods

Participants

Participants (n = 330) were drawn from a convenience sample recruited via social media and from students at a large southwestern university. Facebook and Twitter platforms were used to promote the online data collection link; data were collected via a snowball convenience sample. Both participant pools were used to diversify the data. In terms of ethnicity, 17.5% were Black, 4.8% Asian, 1.3% Native American, 62.7% white, and 13.8% mixed/other. Of those, 21% reported to be Hispanic/Latino. The average age was 22 years. Of the participants, 67% have traveled outside of the U.S., and 18% have lived outside the U.S. Of the participants, 29% were male and 71% female.Footnote 1

Variables

Message Evaluation

The messages were evaluated based on perceived persuasiveness and perceived threat from the message. The perceived persuasiveness measure, derived from Dillard et al. (Reference Dillard, Kinney and Cruz1996) cognitive appraisal scale, used 7-point Likert-type scale items (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Items included evaluations of message quality, accuracy, relevance, and importance. Reliability was excellent (α = .925, M = 4.07, SD = 1.16). The perceived threat measure, derived from Dillard and Shen’s (Reference Dillard and Shen2005) scale of perceived threat, used 7-point Likert-type scale items (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Items consisted of the message threatened my freedom to choose, the message tried to manipulate me, the message tried to make a decision for me, and the message tried to pressure me. Reliability was very good (α = .871, M = 2.71, SD = 1.37).

Behavior Intention Inventory

To measure intentions to participate in environmental volunteer tourism behaviors, an inventory was adapted from previous tourism (Sparks Reference Sparks2007) and consumer (Zaichkowsky Reference Zaichkowsky1985) behavior inventory measures. Similar behavior measures have been used also in previous environmental studies (e.g., Kormos and Gifford Reference Kormos and Gifford2014). The current measure was modified to address potential environmental volunteer tourism behavior. Items included intention to participate in environmental volunteer tourism, learn more about ecovoluntourism, participate in work or school sponsored trips, and explore opportunities on social media. To gauge likely participation in tourism, the measure utilized a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly unlikely, 7 = strongly likely) to predict potential behavior. Reliability was good (α = .915, M = 4.03, SD = 1.07).

Perceived Hedonic Value

The measure, derived from Babin et al. (Reference Babin, Darden and Griffin1994), used 7-point Likert-type scale items (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The one-dimensional scale consisted of 12 items aimed at depicting respondents’ consumption perceptions of ecovoluntourism. The scale included items gauging whether environmental volunteer tourism looks like a joy, looks truly enjoyable compared to other vacation options, looks exciting, excited at the thought of participating, seems like an escape, enjoy being immersed, enjoy for its own sake not just for skills I gain, seems like a meaningful use of my time, allows me to forget about everyday problems, seems like an adventure, and would be a good time. Reliability was excellent (α = .947, M = 4.77, SD = 1.27).

NEP

The NEP scale has been employed a number of times to assess environmental attitudes in several countries as well as people from different social categories (e.g., Schultz and Zelezny Reference Schultz and Zelezny1999), to report the awareness of the environmental consequences (Widegren Reference Widegren1998). The scale consists of items asking general environmental topics, measuring the overall relationship between humans and the environment. The scale consisted of 15 items on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) pertaining to different environmental views. Reliability was excellent (α = .912, M = 4.59, SD = .63).

Procedure

This study utilized a 2 (regulatory focus induction: prevention/promotion) × 2 (promotion/prevention message) factorial experimental design. The survey used the online data collection service Qualtrics. The study followed ethical requirements under Institutional Review Board regulations.

Participants first completed a consent form before proceeding to the survey. Participants were asked about environmental attitudes NEP before being randomly assigned to an experimental condition, either prevention induction or promotion induction. As prescribed by Higgins et al. (Reference Higgins, Friedman, Harlow, Idson, Ayduk and Taylor2001), participants were randomly induced into a promotion or prevention focus by either writing about something they ideally wanted to achieve (promotion focus) or writing about an obligation they could not fail to keep (prevention focus).

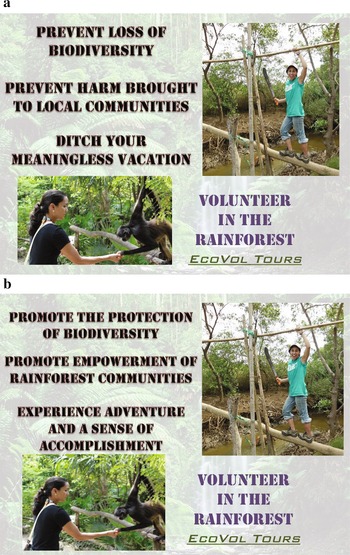

The survey then presented condition messages in the form of two ads that participants were randomly assigned to view. Experimental advertising messages were created to mimic those that might be used in a social media campaign. The messages utilized the same design, font, and imagery in order to maintain visual continuity. The promotion messages included positive statements focusing on the promotion of an ecological and personal gain from the volunteering experience (Fig. 1a). Conversely, the prevention messages used more dire language focusing on the prevention of ecological loss (Fig. 1b). Message creation was guided by regulatory focus induction language (Higgins et al Reference Higgins, Friedman, Harlow, Idson, Ayduk and Taylor2001) to create promotion and prevention tones; they were pilot tested prior to data collection to ensure that the messages were clear. Following the messages, participants answered questions about perceptions of the ad in terms of persuasiveness, reactance, utility, hedonic value, and potential behavior. Demographic information was then collected.

Fig. 1 a Prevention-focused message b Promotion-focused message

Analysis and Results

The overall analysis strategy aimed to examine all the variables in one omnibus analysis and then subsequently parse out planned comparisons. A multivariate analysis of variance strategy was adopted to compare the experimental groups, account for the covariate, and analyze the complete set of dependent variables in order to reduce error. We first examined the omnibus multivariate model to assess the overall variable interaction and to address research questions one and two. Two separate factorial MANOVAs were run to assess hypothesis one and two.

To examine the main effects and interaction of the regulation manipulation and message type, an omnibus MANCOVA was run. The covariate of environmental attitudes was included. Box’s M (56.69) was not significant (p = .143). There was not a significant multivariate main effect for regulation manipulation, Wilks λ = .991, F(5, 325) = .610, p = .692, partial η 2 = .009. The interaction between regulation manipulation and message type was not significant, Wilks λ = .982, F(5, 325) = 1.19, p = .311, partial η 2 = .018.

RQ1

Research question one inquired about how existing environmental attitudes would influence promotion versus prevention message reception. The covariate was significant: environmental attitudes (Wilks λ = .893, F(5, 325) = .82, p < .001, partial η 2 = .107). There were significant main effects on perceived persuasiveness [F(1, 15.79) = 11.39, p < .001, partial η 2 = .033], hedonic value [F(1, 37.15) = 25.27, p < .001, partial η 2 = .071], and behavioral intention [F(1, 23.67) = 10.94, p < .001, partial η 2 = .032].

RQ2

There was a significant multivariate main effect for message type, Wilks λ = .915, F(5, 325) = 6.05, p < .001, partial η 2 = .085. The univariate main effects were significant for perceived persuasiveness [F(1, 15.46) = 11.16, p < .001, partial η 2 = .033], perceived threat [F(1, 25.55) = 13.41, p < .001, partial η 2 = .039], and perceived hedonic value [F(1, 5.71) = 4.32, p = .05, partial η 2 = .012]. This analysis sheds light on research question two, which inquired about how prevention versus promotion messages influence perceptions of hedonic and utilitarian value.

H1

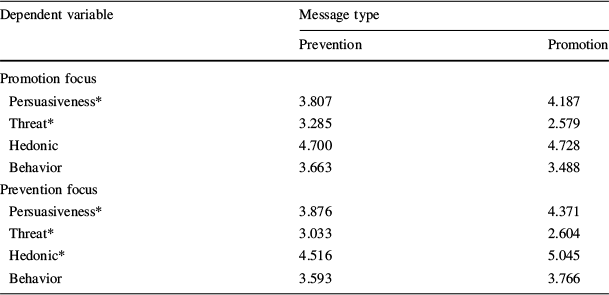

To further isolate and examine the influence of regulation manipulation on message type, two factorial MANOVAs were run to examine hypothesis one and two. Hypothesis one predicted for the promotion-focused experimental group, the promotion message would be perceived as (a) more persuasive, (b) less threatening, and (c) increase behavioral intentions compared to the prevention message. To examine the promotion focus manipulation, a subset of the data was selected and analyzed. A one-way MANOVA was run examining message type on the dependent variables. There was a significant multivariate main effect for message type, Wilks λ = .912, F(5, 164) = 3.179, p = .009, partial η 2 = .088 (Box’s M = 16.49, p=.384). The univariate main effects were significant for perceived persuasiveness [F(1, 6.15) = 4.09, p=.045, partial η 2 = .024] and perceived threat [F(1, 21.72) = 10.33, p = .002, partial η 2 = .058].

In a promotion focus, the promotion message was seen a more persuasive (M = 4.187) compared to the prevention message (M = 3.807). Moreover, in a promotion focus, the promotion message was seen as less threatening (M = 2.579) compared to the prevention message (M = 3.285). The univariate main effects were not significant for hedonic and behavioral intention. In the promotion focus, the promotion message was not perceived as having significantly higher hedonic value (M = 4.728) compared to the prevention message (M = 4.701). Moreover, the promotion message did not inspire potential behavior (M = 3.488) significantly more than the prevention message (M = 3.663).

H2

Hypothesis two predicted for the prevention-focused experimental group, the prevention message would be perceived as (a) more persuasive, (b) less threatening, and (c) increase behavioral intentions compared to the promotion message. To examine the prevention focus manipulation, a subset of the data was selected and analyzed. A one-way MANOVA was run examining message type on the dependent variables. There was a significant multivariate main effect for message type, Wilks λ = .896, F(5, 160) = 3.727, p = .003, partial η 2 = .104 (Box’s M = 25.27, p = .06).

The univariate main effects were significant for perceived persuasiveness (F(1, 10.17) = 7.52, p = .007, partial η 2 = .044), perceived threat [F(1, 7.64) = 4.30, p = .04, partial η 2 = .026], and perceived hedonic value [F(1, 11.61) = 7.87, p = .006, partial η 2 = .046]. In the prevention focus, the promotion message was perceived as significantly more persuasive (M = 4.371) compared to the prevention message (M=3.876). Moreover, in the prevention focus, the promotion message was perceived as significantly less threatening (M = 2.604) compared to the prevention message (M = 3.033). In terms of perceived hedonic value while in a prevention focus, the promotion message was perceived to have higher hedonic value (M = 5.045) compared to the prevention message (M = 4.516). The univariate main effect was not, however, significant for behavioral intention. In the prevention focus, the promotion message was not perceived as inspiring significantly higher behavioral intention (M = 3.766) compared to the prevention message (M = 3.593).

Discussion

A growing number of young people are making informed choices and contributing to the well being of the natural environment through conservation volunteering (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2010; McDougle et al. Reference McDougle, Greenspan and Handy2011). Conservation volunteering travel is an increasingly popular way for Millenials, who are currently the most environmentally conscious consumers (Smith and Miller Reference Smith and Miller2011; Vermillion and Peart Reference Vermillion and Peart2010), to engage in global citizenship (Lorimer Reference Lorimer2010; McDougle et al. Reference McDougle, Greenspan and Handy2011). However, as experts want a typically consistent multiple-year increase in these forms of civic engagement, organizations must continuously reinforce the importance of young adults pursuing environmental and conservation activities (Eisner Reference Eisner2005).

With the goal of applying regulatory focus theory, this study sought to illuminate the effects of persuasive message for promoting the conservation volunteering experience to a Millennial audience. The first hypothesis pertained to the usefulness of a promotion focus induction mixed with a promotion-focused message, while the hypothesis two pertained to the usefulness of a prevention focus induction mixed with a prevention-focused message. Moreover, research question one pertained to the effect of environmental attitudes on reception of promotion/prevention persuasive messages. Research question two pertained to the effect of these messages on perceived hedonic value of conservation volunteering.

Parsing out prevention and promotion induction conditions revealed interesting trends. Namely, regulatory induction was not significant, meaning that response to promotion/prevention messages is not affected by individual’s regulatory focus. On the contrary, the promotion message worked better for both groups (prevention- or promotion-focused individuals), meaning it was perceived as more persuasive. It also had higher hedonic value and produced less reactant attitudes. Respondents thought the positive message involved more enjoyable options and held less negative thoughts about the message. It evoked the primal desires of adventure and excitement about the type of experiences who can enjoy by participating in conservation projects. The results suggest promotion messages are better received (more persuasive) because they induce expectations in line with general view of conservation volunteering as a hedonic experience (Malone et al. Reference Malone, McCabe and Smith2014).

These results fall in line with some past research presenting conservation volunteering travel as a primarily emotional hedonic experience (e.g., Alba and Williams Reference Alba and Williams2013) or studies of propensity to engage in pro-environmental activities among visitors to wildlife areas (Lemelin et al. Reference Lemelin, Fennell and Smale2008). In this, light conventional tourism stands for more traditional consumer values of material possessions or personal wealth (Fournier and Richins Reference Fournier and Richins1991) leading to convenience, variety, quality, or low price seeking behavior, while travel for conservation volunteering is associated with positive emotions and emotional desires. These positive emotional desires translate into a person’s need for pleasurable and interesting experiences (Pearce Reference Pearce2009; Alba and Williams Reference Alba and Williams2013; Malone et al. Reference Malone, McCabe and Smith2014).

Lemelin et al. (Reference Lemelin, Fennell and Smale2008) suggested that research has made a faulty assumption that visitors to wildlife areas share positive environmental ethics, biocentric values, and intrinsic motives (e.g., Acott et al. Reference Acott, La Trobe and Howard1998; Honey Reference Honey1999). They found differences in the propensity to engage in pro-environmental behavior for the wildlife tourism specialization groups with connoisseurs and enthusiasts scoring significantly higher than novices (Lemelin et al. Reference Lemelin, Fennell and Smale2008). It could be concluded that visitation to wildlife areas may not necessarily be motivated by willingness to engage in pro-environmental behavior, but instead is motivated by a desire of adventure and hedonic experiences. Moreover, Lemelin et al. (Reference Lemelin, Fennell and Smale2008) suggest specialization of a visitor to wildlife area that may reflect conspicuous consumption (i.e., inspirational overbuying or social status) rather than ‘commitment to or involvement in an activity’ (e.g., McIntyre and Pigram 1992; 4 in Lemelin et al. (Reference Lemelin, Fennell and Smale2008)). This corresponds with our findings where conservation volunteers demonstrated desire of hedonic experience rather than commitment to nature conservation.

Reflecting on previous regulatory focus research in a context of environmental communication, this study produced both congruent and incongruent results. While Bullard and Manchanda (Reference Bullard and Manchanda2013) argue sustainable marketing makes people more prevention focused and they prefer prevention messages; our research contradicts their findings as we found prevention-focused people considered the promotion message to be more persuasive, generating less perceived threat, and having higher hedonic value.

Finally, with regard to the question concerning the relationship between environmental attitudes and perception of conservation volunteering messages, we found that these attitudes do affect the perception of message persuasiveness, the perception of hedonic value of this type of volunteering, as well as behavioral intention to participate in this pro-environmental activity. While the character of this relationship needs to be further explored in future, our study is the first one of its kind to show this important effect of environmental attitudes on individuals’ responses to conservation volunteering messages. This could further be tested, for example, in terms of different groups of volunteers categorized according to expressed environmental attitudes or relationship between different attitudes and participation in conservation volunteering. This part of our research was guided by studies of the relationship between environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviors which employed the NEP theory and our findings are in line with this past research (e.g., Eagles and Higgins Reference Eagles, Higgins, Lindberg, Wood and Engeldrum1998; Luo and Jinyang Reference Luo and Jinyang2008; Sampaio et al. Reference Sampaio, Rhodri and Font2012). Moreover, not only does it contribute to the explanation of what factors affect reception of pro-environmental promotional messages, but also it provokes further discussion of the relevance of environmental attitudes, and hedonic desires.

Conclusion

With declining public funding to support nature conservation, building continuous commitment to nature through volunteering is key to addressing a range of societal environmental priorities such as enhancing biodiversity and building sustainable communities (e.g., Anheier and Salomon Reference Anheier and Salomon1999; Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Taber, Daszak, Sukumar, Valladares-Padua and Padua2007; Wearing and McGehee Reference Wearing and McGehee2013). Numerous studies have explored volunteering from a tourism perspective (Callanan and Thomas Reference Callanan, Thomas and Novelli2005; Raymond and Hall Reference Raymond and Hall2008; Soderman and Snead Reference Soderman, Snead, Lyons and Wearing2008; Wickens Reference Wickens and Benson2011), and yet the majority focused predominantly on the values of the volunteer and how these values translate into motives (e.g., Brown and Lehto Reference Brown and Lehto2005; Campbell & Smith Reference Campbell and Smith2006; Wearing Reference Wearing2001). In this line of reasoning, we explored the effects of person’s regulatory focus on their perception of persuasive messages. We found positive messages are perceived as more persuasive regardless of the respondent’s regulatory focus and that preexisting environmental attitudes affect how messages promoting conservation volunteering are received.

These results are of importance to scholars because they challenge how we traditionally think prevention and promotion focus works in marketing messages. Namely, individual regulatory focus is not a factor driving response to messages promoting conservation volunteering. For Millennials, environmental attitudes and desires for hedonic experience appear to be affecting their response to messages. These findings could inform organizations which strive to attract committed individuals who are also willing to pay for the experience.

These results are also of importance to organizations marketing campaigns because environmental messages tend to be framed as prevention messages which is the contrary to what this study’s results suggest to do. Namely, communications that focus on natural disasters or environmental apocalypse (i.e., ice caps melting or animals becoming extinct) appear to be less persuasive than positively framed messages focused on self-promotion, adventure as well as the support to those. Concentrating on positive aspects would be strategically beneficial.

Finally, this study points out that Millenials are hedonistic in their lifestyle choices which has some important implications in terms of conservation volunteering. It is plausible that conservation volunteering is seen as a form of ethical form of tourism or ethical leisure as proposed by Malone et al. (Reference Malone, McCabe and Smith2014). This could be an indication of how eco-awareness influences Millennials travel choices This finding also supports Lorimer’s (Reference Lorimer2009) argument concerning limited impact of conservation volunteering on international conservation in general, suggesting that this is mainly due to volunteer travelers being more interested in remote and unique and therefore attractive ecosystems rather than domestic conservation projects. Consuming ecosystems through volunteering in conservation projects internationally satisfies Millenials who needs to explore, remote, and exotic places and simultaneously contributing to their need to participate in conservation of endangered ecosystems and species.

Limitations

Although this study is the first to look at prevention/promotion focus and message reception in the context of conservation volunteering, it is not without limitations. First, this study utilized self-reporting of intentions to participate in conservation volunteering. While this type of measure has previously been used in environmental context (e.g., Kormos and Gifford Reference Kormos and Gifford2014), future research can attempt to track actual ethical tourism behaviors such as conservation volunteering and the individual characteristics such as self-efficacy (Bandura Reference Bandura1977) that may affect it, or examine the nuance between ecological stewardship versus perceived consumer hedonic value in the context of conservation volunteering.

Second, this study presumed greater environmental consciousness among Millenials. However, research on eco-awareness of Millennials is rather scarce, and no global surveys results are available at this point of time. We acknowledged this as the limitation of the study and possible future research. Third, a convenience sample was used via social media (Facebook and Twitter promotion) in addition to student participants. While the experimental design and random assignment to condition improve the internal validity, convenience samples are a limitation to the external validity. Future should seek additional participant selection techniques like professional recruitment services (e.g., Qualtrics panels).

Appendix

See Table 1.

Table 1 Promotion and prevention focus

|

Dependent variable |

Message type |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Prevention |

Promotion |

|

|

Promotion focus |

||

|

Persuasiveness* |

3.807 |

4.187 |

|

Threat* |

3.285 |

2.579 |

|

Hedonic |

4.700 |

4.728 |

|

Behavior |

3.663 |

3.488 |

|

Prevention focus |

||

|

Persuasiveness* |

3.876 |

4.371 |

|

Threat* |

3.033 |

2.604 |

|

Hedonic* |

4.516 |

5.045 |

|

Behavior |

3.593 |

3.766 |

* p = .05