Adverse childhood experiences, defined as victimisation, neglect, and household dysfunction prior to the age of 18 years, Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg1,Reference Cronholm, Forke and Wade2 are well-known to contribute to various poor health outcomes in adulthood, Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg1 from cardiovascular disease to obesity, likely via a combination of biological, mental health, and behavioural mechanisms. Reference Suglia, Koenen and Boynton-Jarrett3 Adverse childhood experiences have been identified as a contributing factor to health disparities, Reference Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen4 and disproportionately affect individuals from low-income and racial/ethnic minority backgrounds. Reference Giano, Wheeler and Hubach5 In recent years, a mounting body of research has shown that the deleterious health effects of adverse childhood experiences may extend across generations, such that children of parents who experience adverse childhood experiences also exhibit poorer health outcomes. For example, higher parental adverse childhood experiences have been associated with heightened risk of pregnancy complications, Reference Racine, Plamondon, Madigan, McDonald and Tough6 pre-term birth, Reference Sulaiman, Premji, Tavangar, Yim and Lebold7 perinatal complications and admission to the neonatal ICU, Reference Ciciolla, Shreffler and Tiemeyer8 early childhood developmental concerns, Reference Folger, Eismann and Stephenson9,Reference Sun, Patel, Rose-Jacobs, Frank, Black and Chilton10 infant sleep difficulties, Reference Ciciolla, Addante, Quigley, Erato and Fields11 and child emotional and behavioural problems. Reference Rowell and Neal-Barnett12–Reference Racine, Deneault and Thiemann14 Similarly, parental adverse childhood experiences have been correlated with missed child well-visits, Reference Eismann, Folger and Stephenson15 higher unanticipated healthcare reutilisation after hospital discharge, Reference Shah, Auger and Sucharew16 and greater parental coping difficulties following their child’s hospitalisation. Reference Shah, Beck and Sucharew17

To date, research on the intergenerational effects of adverse childhood experiences has focused on the general population, leaving open the question of whether—and to what extent—parental adverse childhood experiences may affect disease course for children with chronic and complex health conditions, such as single ventricle CHD. Understanding the potential impact of parental adverse childhood experiences on health outcomes for patients with single ventricle CHD is particularly relevant given their predisposition to lifelong medical complications, Reference Atz, Zak and Mahony18 as well as the longstanding disparities in CHD morbidity and mortality based on social determinants of health (e.g., poverty), which are known to be related to adverse childhood experiences. Reference Davey, Sinha, Lee, Gauthier and Flores19,Reference Suglia, Saelee and Guzmán20 According to Lisanti’s Parental Stress and Resiliency in CHD model, Reference Lisanti21 preconception factors (such as parental adverse childhood experiences) can impact child health outcomes via a complex pathway involving parental stress response, parental resiliency resources, and parents’ own health/well-being. Importantly, the impact of parental adverse childhood experiences on child outcomes may be mitigated through enhancement of protective factors (e.g., social support Reference Hatch, Swerbenski and Gray22,Reference Racine, Madigan, Plamondon, Hetherington, McDonald and Tough23 ), offering a potential path forward to improving outcomes for children with single ventricle CHD in the setting of heightened psychosocial risk.

Taken together, there is a need for study of the intergenerational impact of adverse childhood experiences for children with single ventricle CHD. The aims of the current study are threefold: (1) to describe the prevalence of parental adverse childhood experiences among young children with single ventricle CHD; (2) to examine the association between parental adverse childhood experiences and single ventricle CHD outcomes during early childhood; and (3) to evaluate the potential moderating effect of parental perceived stress and social support on the relation between parental adverse childhood experiences and single ventricle CHD outcomes to identify possible targets for intervention. By accomplishing these aims, the current study seeks to inform our understanding of factors that heighten vulnerability to poor single ventricle CHD outcomes, as well as elucidate potential targets for intervention to mitigate risk.

Materials and method

Study design

English-speaking adult caregivers of children ages 0–8 years with single ventricle CHD were recruited from an ongoing longitudinal follow-up research programme of paediatric patients who received a Society of Thoracic Surgeons benchmark CHD operation at the study site. The longitudinal follow-up programme has been following patients since 2010. The current study focused on this age range given the need for repeated surgical intervention early in life for children with single ventricle CHD, as well as prior research demonstrating associations between parental adverse childhood experiences and infant/early childhood outcomes in the general population. Participants were included in the study if >30 days had passed since their child’s discharge from their most recent benchmark surgery to reduce the likelihood of survey measures capturing acute hospital-related distress. Eligible caregivers received an initial study recruitment email with a link to complete informed consent and a self-report electronic survey via REDCap. Participants also agreed to a review of their child’s electronic medical record. If participants did not respond to the initial email contact, study staff completed additional email and telephone contact attempts. Participants received a $30 gift card for their time. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the study site.

Measures

Parent and child demographics

Participants completed self-report demographic questionnaires regarding their relationship to the patient, race/ethnicity, date of birth, household income, education level, employment, marital status, and household composition. Child demographic information, including sex, date of birth, and insurance status, was obtained via electronic medical record review. Parents additionally reported on whether their child received their cardiology care at the study institution.

Child surgical history

Child surgical history, including types of surgeries completed, time since most recent benchmark surgery, and heart transplant status, was obtained via electronic medical record review.

Parental adverse childhood experiences

The 10-item self-report adverse childhood experiences questionnaire Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg1 was used to measure parents’ experiences of adverse childhood experiences, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; emotional and physical neglect; and household dysfunction (e.g., substance use, mental illness, or incarceration of a household member, parental divorce) before the age of 18 years. Participants responded yes/no to each item.

Parent perceived stress

The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein24 was used to assess respondents’ perception of their lives as overwhelmed and uncontrollable (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and ‘stressed’”?), with responses measured on a 5-point scale from “Never” to “Very Often.” Item responses were summed to create a total score.

Parent perceived social support

The 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley25 was used to assess adults’ perceived social support (e.g., “I can talk about my problems with my family.”), with responses measured on a 7-point scale from “Very Strongly Disagree” to “Very Strongly Agree.” Item responses were summed to create a total score.

Community-level risk

Neighbourhood environmental risk was assessed using the CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index. Child home addresses were collected via electronic medical record review to determine family’s census tract and the associated overall Social Vulnerability Index ranking based on 2022 national data. 26

Health-related outcomes

The following health-related outcomes were assessed: (1) Number of hospital admissions (chart review), which included any admission >24 hours during the child’s life that was visible in the child’s electronic medical record. This variable excluded emergency department visits; (2) Number of hospital admissions (parent report) was assessed by asking parents to report on their child’s total number of hospital admissions, excluding emergency department visits. Parent-reported hospital admission was collected given the possibility of a child’s admission at an outside hospital that would not be reflected in the child’s electronic medical record; (3) Total hospital length of stay (chart review) was calculated by summing the length of stay (in days) across all of the child’s hospital admissions recorded in the child’s electronic medical record; (4) Total number of missed appointments (chart review) was assessed by summing the total number of past appointments at the study institution that were classified as “no show” in the child’s electronic medical record.

Statistical analyses

Data were reported as frequency with percentage (%) for categorical variables and median with interquartile range or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables, as appropriate. Univariate associations between parental adverse childhood experiences (measured dichotomously as exposed/not exposed) and child/parent demographics, child medical/surgical history, and Social Vulnerability Index overall score were examined using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test or two-sample t-test for continuous variables. Associations between parental adverse childhood experiences and each of the child health outcomes were evaluated using negative binomial regression. Incidence rate ratio [Exp(β)] and its 95% confidence interval of adverse childhood experiences exposure from the regression were reported. To examine the potential moderating effects of parents’ perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale total score) and social support (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support total score) on the associations between parental adverse childhood experiences and each of the child health outcomes, an interaction term between parental adverse childhood experiences and either Perceived Stress Scale total score or Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support total score was included in the negative binomial regression model in addition to the main terms of the corresponding variables. Each moderation analysis accounted for time since last benchmark surgery and overall Social Vulnerability Index score in the model. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), with a significance level of 0.05 using two-sided tests.

Results

Participants

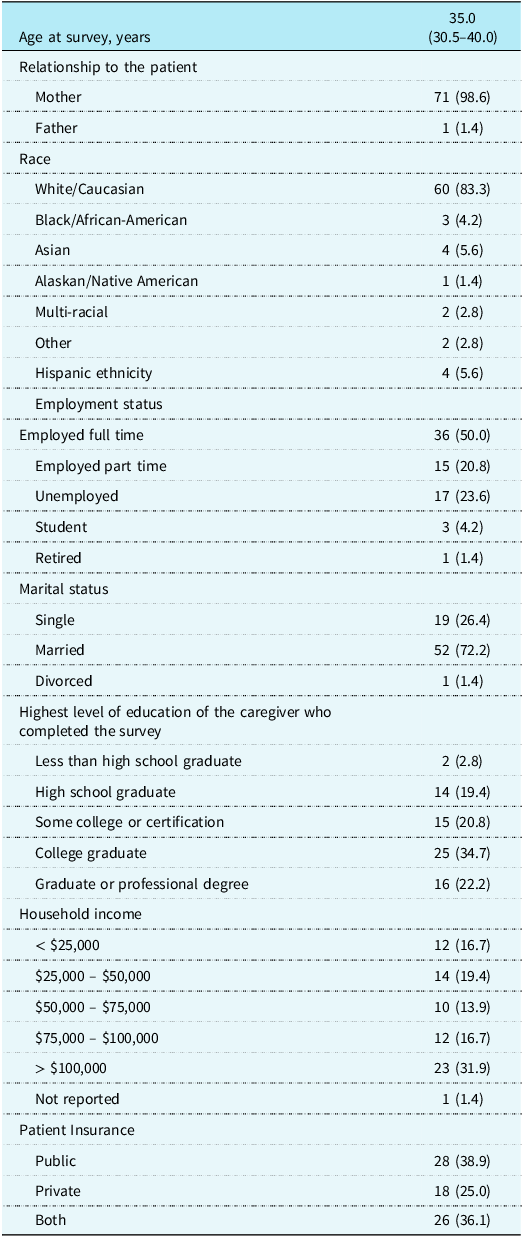

Of the 196 parents contacted, a total of 72 parents of young children with single ventricle CHD consented to study participation and completed the adverse childhood experiences questionnaire (37% participation rate). Parents were primarily White/Caucasian race (83.3%), mothers (98.6%), and married (72.2%). Nearly all parents reported a secondary caregiver at home (87.5%), most commonly a father (85.7% of those with secondary caregiver). Most participants were employed, either full- (50%) or part-time (20.8%). Demographic information is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Caregiver demographics and family/sociodemographic characteristics (N = 72)

*Data are presented as N (%) for categorical variables and Median (interquartile range) for continuous variable.

The children of participants were just over half male (56.9%), with a median age of 4.9 years (range 1.3–8.9 years). Over half (59.7%) received their cardiology care at the study institution, with the remaining children seeing an outside cardiologist for their non-surgical cardiology care. The number of cardiac surgeries for children ranged from 2 to 6 (median = 3), and the median length of time from the child’s last benchmark surgery to the survey date was 2.2 years. Two patients (2.8%) received heart transplants. Regarding health outcomes, the number of hospital admissions assessed via chart review ranged from 2 to 40, with a median of 5. Parent-report of number of hospital admissions ranged from 0 to 50, with a median of 5. Total hospital length of stay (per chart review) ranged from 19 days to 1.3 years, with a median of 2.2 months. Two-thirds of patients (66.7%) had missed at least one medical appointment during their lifetime.

Prevalence of parental adverse childhood experiences

Just over half of parents (n = 38, 52.8%) endorsed exposure to at least one adverse childhood experience, with total number of adverse childhood experiences ranging from 0 to 7. Over 1 in 10 parents (n = 9, 12.5%) endorsed exposure to 4+ adverse childhood experiences. The most frequently endorsed adverse childhood experiences were parental loss (n = 21, 29.2%), substance use in the home (n = 19, 26.4%), mental illness in the home (n = 16, 22.2%), emotional abuse (n = 10, 13.9%), emotional neglect (n = 9, 12.5%), and physical abuse (n = 8, 11.1%). Fewer participants endorsed household member incarceration (n = 7, 9.7%), sexual abuse (n = 5, 6.9%), physical neglect (n = 3, 4.2%), or domestic violence in the home (n = 3, 4.2%). Of note, parents with a history of adverse childhood experiences were more likely to be younger than parents without a history of adverse childhood experiences (median [interquartile range] 33 [30–37] years vs. 37.5[33–41] years, p = 0.01). No other significant associations between parental adverse childhood experiences and child/parent demographics, Social Vulnerability Index overall score, or child medical history were found.

Univariate associations between parental adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes

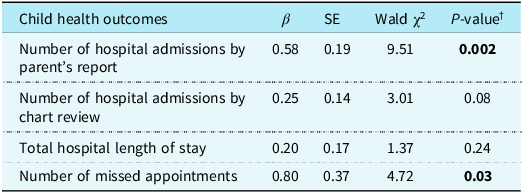

There was a significant positive association between parental adverse childhood experiences and parent’s report of their child’s number of hospital admissions in univariate analysis (Table 2). Specifically, parents with a history of adverse childhood experiences were 1.78 times as likely to endorse more hospital admissions for their child compared with those without a history of adverse childhood experiences (Exp[β] = 1.78, 95% confidence interval = 1.23-2.58, p = 0.002). Similarly, there was a trending positive association between parental adverse childhood experiences and the child’s number of hospital admissions measured via chart review, such that parents with a history of adverse childhood experiences were 1.28 times as likely to endorse more hospital admissions for their child (Exp[β] = 1.28, 95% confidence interval = 0.97–1.70, p = 0.08). No significant associations were found between parental adverse childhood experiences and the child’s total length of stay across all hospital admissions (Exp[β] = 1.22, 95% confidence interval = 0.88–1.69, p = 0.24). Finally, parental adverse childhood experiences were significantly associated with the child’s number of missed appointments (Exp[β] = 2.22, 95% confidence interval = 1.08–4.56, p = 0.03), such that children of parents with adverse childhood experiences exposure were 2.22 times as likely to have missed more appointments compared to those without a history of adverse childhood experiences.

Table 2. (Univariate) associations between parental ACEs and child health outcomes

β = parameter estimate; SE = standard error.

† P-value from (univariate) negative binomial regression.

Moderation by perceived stress and social support

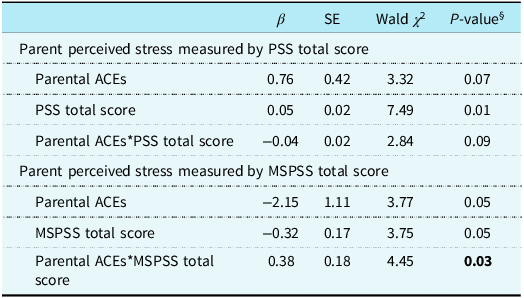

Parents’ perceived social support measured by Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support total score significantly moderated the relationship between parental adverse childhood experiences and total hospital length of stay (p = 0.03). Specifically, as one unit increased in Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support total score, parents with a history of adverse childhood experiences were likely to have an 83% reduction (Exp[–2.15 + 0.38] = 0.17) in their child’s hospital length of stay compared to those without a history of adverse childhood experiences (Table 3). Similarly, parents’ perceived stress measured by Perceived Stress Scale total score showed a trend towards moderation effect on the association between parental adverse childhood experiences and total hospital length of stay (p = 0.08), such that parents with a history of adverse childhood experiences were 2.05 times (Exp[0.76–0.04] = 2.05) as likely to have increases in hospital length of stay for their child as one unit increased in Perceived Stress Scale total score. No other significant moderation effects by parents’ perceived stress and social support were found in the relationship between parental adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes.

Table 3. Moderating effects of parent perceived stress and support on the association of parental ACEs and their child’s total hospital length of stay

All moderation analyses accounted for overall SVI score and time since last benchmark surgery.

β = parameter estimate; SE = standard error.

§ P-value from multivariable negative binomial regression including the main terms of time since surgery, SVI overall score, parental ACEs, PSS total score or MSPSS total score, and an interaction term between parental ACEs and either PSS total score or MSPSS total score.

Discussion

The current study provides an initial estimation of the prevalence of parental adverse childhood experiences among young children with single ventricle CHD and their association with child health outcomes among a single-centre sample. Approximately half of parents endorsed a personal history of childhood adversity, with 12.5% of parents reporting high exposure to adversity (4+ adverse childhood experiences). Prevalences of parental adverse childhood experiences in this study were slightly lower than nationally representative samples of adults, which estimate that 63.9% of U.S. adults have experienced at least one adverse childhood experience and 17.5% have experienced 4+ adverse childhood experiences. Reference Swedo27 This may be due, in part, to parents’ underreporting of sensitive personal information, though it may also reflect the demographic differences (e.g., race/ethnicity, income level) between our study sample and nationally representative samples. Reference Swedo27

Notably, parental adverse childhood experiences did show a significant association with some child health outcomes, including missed appointments and number of hospital admissions (as reported by the parent). These findings are consistent with prior research showing higher rates of missed child well-visits Reference Eismann, Folger and Stephenson15 and unanticipated healthcare reutilization Reference Shah, Auger and Sucharew16 for children of parents with adverse childhood experiences exposure in the general population. The heightened risk of missed visits is of particular concern for children with single ventricle CHD, as early identification and management of Fontan-related complications and heart failure are critical to avoid clinical instability or missing the window for advanced cardiac therapies. Reference Chen, Shezad and Lorts28 While examination of factors underlying these associations was beyond the scope of the current study, prior research suggests that the intergenerational impact of adverse childhood experiences may occur via a complex combination of psychological/behavioural, neurobiological, and social mechanisms. Reference Zhang, Mersky, Gruber and Kim29 Continued research elucidating these indirect pathways is critical to inform targeted intervention efforts to promote child health.

Despite the concerning associations between parental adverse childhood experiences and child health, results also suggest avenues for supporting positive health outcomes in the setting of heightened intergenerational risk. Specifically, results showed that parents’ perception of higher social support was associated with an 83% reduction in total hospital length of stay for children whose parents had been exposed to adverse childhood experiences, highlighting a potential buffering effect of social support. Social support has been identified as an important component of parents’ coping with a child’s CHD, Reference Lumsden, Smith and Wittkowski30 with parents utilising diverse sources of support, including partners, CHD support groups, and medical professionals. Formal hospital-based services, such as early palliative care involvement Reference Hancock, Pituch and Uzark31 and psychology-led psychosocial intervention during the prenatal period, Reference Sood, Nees and Srivastava32 have also shown promise in increasing parents’ sense of social support and related outcomes, though continued gaps exist in meeting parents’ desire for psychosocial supports early in their child’s life. Reference Kasparian, Kan, Sood, Wray, Pincus and Newburger33–Reference Driscoll, Christofferson and McWhorter35 Our results suggest that such practices may be especially beneficial for children of families at heightened risk for poor outcomes. Furthermore, it is likely that the efficacy of these programmes can be enhanced by infusing a trauma-informed approach, both given the prevalence of trauma history and adversity among parents (over 50% in our cohort) and the high incidences of posttraumatic stress symptoms among parents of children with critical CHD. Reference Woolf-King, Anger, Arnold, Weiss and Teitel36 Adaptations of existing trauma-informed, evidence-based interventions for parents in the general population may be a cost-effective and expedient way to increase social support for parents of children with CHD, particularly those with histories of psychosocial adversity. Reference Sood, Lisanti and Woolf-King37 Though additional research is needed, findings from the current study reinforce the importance of developing expanded models of care that advance parent and family psychosocial well-being, as highlighted by a recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Reference Kovacs, Brouillette and Ibeziako38

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

Using a multimethod approach, the current study provided novel insights regarding the associations between parents’ early adversity and the health outcomes of their children with single ventricle CHD, along with potential targets for intervention to support optimal health in the setting of pre-existing psychosocial risk. However, study findings must be interpreted in light of study limitations. First, the study included a single-centre, relatively small sample, limiting generalizability of the findings and precluding more sophisticated statistical modelling with relevant covariates. The participants predominately identified as White, female, married, and employed, thereby limiting generalizability of results to others, while also potentially providing an under-report of parental adverse childhood experiences in single ventricle CHD at large. Self-selection bias may also have impacted representativeness of the sample and should be considered when interpreting the findings. Our sample size required that parental adverse childhood experiences were analysed in a dichotomous fashion (i.e., exposed/not exposed) and did not allow for estimation of the dose-response effects of adverse childhood experiences on child health outcomes. Further, the current study examined intergenerational associations at a single time point in a cohort of young children (≤8 years). It is unclear whether the observed associations would remain stable if assessed at a different developmental time point or assessed longitudinally. Finally, approximately 40% of the children in our cohort were followed by cardiologists outside of the hospital system, and it is possible that they had additional medical appointments or admissions that were not reflected in the study site’s electronic medical record, biasing measurement of these variables.

Taken together, future research should focus on replicating results with a larger sample, elucidating potential mechanisms and confounding variables influencing these effects, and identifying modifiable factors that can serve as targets for intervention. In doing so, future work can expand upon and strengthen our initial findings, with the ultimate goal of optimising health outcomes for children with single ventricle CHD.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Blake Armstrong for his role as study coordinator and Ray Lowery for his work as data manager.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of Michigan Medical School Pandemic Research Recovery grant.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.