Immigration is among the most salient and consequential issues of contemporary European politics, and since at least the 2000s it has resulted in political conflict and increased Euroscepticism. A sizeable literature documents the relevance of immigration and immigration-related attitudes for a host of political outcomes, ranging from electoral behaviour (Halikiopoulou and Vlandas Reference Halikiopoulou and Vlandas2020; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2008) to welfare policy preferences (Burgoon and Rooduijn Reference Burgoon and Rooduijn2021; Cappelen and Peters Reference Cappelen and Peters2018). By contrast, the political consequences of emigration have received much less attention from political scientists, even though interdisciplinary migration studies turned to this question some time ago (Toyota et al. Reference Toyota, Yeoh and Nguyen2007).

In the European Union (EU) context, belief in the right to free movement between the member states has been widespread among the public and a cornerstone of the EU project, serving as a key mechanism of economic and political integration. Nonetheless, since the Eastern enlargements in the 2000s, flare-ups in the politicization of free movement have occurred sporadically in predominantly receiving states (i.e. as an immigration concern) (Kyriazi et al. Reference Kyriazi, Mendes, Rone and Weisskircher2023). More recently, we have witnessed episodes of politicization of the other side of the migration coin – emigration – in predominantly sending states situated in the EU’s eastern and southern belt (Kyriazi et al. Reference Kyriazi, Mendes, Rone and Weisskircher2023). Both public discourse and scholarship have refocused attention on emigration as a politically mobilizing issue, often alongside demographic concerns such as low fertility and ageing.

Despite this, the extent to which emigration has become electorally problematized and consequential remains under-researched. However, an emergent agenda has taken the first steps in filling this knowledge gap (Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Dehdari, Laitin, Marbach and Vernby2025; Kyriazi and Visconti Reference Kyriazi and Visconti2025; Lim Reference Lim2023; Sánchez-García et al. Reference Sánchez-García, Rodon and Delgado-García2025; van Leeuwen et al. Reference van Leeuwen, Halleck Vega and Hogenboom2021). This dovetails with studies on the ‘geographies of discontent’ (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Dijkstra et al. Reference Dijkstra, Poelman and Rodríguez-Pose2020), which have identified a glaring rural/urban divide in individual attitudinal and behavioural patterns. Perhaps for this reason, the literature linking emigration and depopulation more generally with political behaviour has shown a special interest in whether demographic shifts strengthen populist radical-right (PRR) parties, as these have been found to be the main beneficiaries of discontent rooted in the uneven geographic distribution of opportunity and wealth. Existing studies relying on region-level data regarding emigration/depopulation rates and voting results tend to distinguish between compositional (i.e. the divergence of the socio-demographic profiles of ‘stayers’ and ‘movers’) and attitudinal (i.e. feelings of resentment growing among those ‘left behind’) mechanisms (e.g. Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Dehdari, Laitin, Marbach and Vernby2025; van Leeuwen et al. Reference van Leeuwen, Halleck Vega and Hogenboom2021). Certainly, this tendency also reflects, in part, the scarcity of large-scale comparative surveys on emigration-related public opinion.

That said, apart from the fact that the regions from where many people emigrate share several commonalities, which cannot always be controlled for and are therefore susceptible to residual confounding, we consider such research designs conceptually problematic for at least two reasons. On the one hand, they assume that people actually perceive their circumstances in the way researchers suggest and that this perception leads them to change their political behaviour in the expected way. In our view, high rates of emigration from a locality can indeed create a political potential, but to become electorally relevant the issue needs to be made salient and problematized as a matter of public intervention – that is, politically mobilized.Footnote 1 On the other hand, such studies imply that emigration is only (or primarily) electorally relevant in localities that many people leave behind. They thus neglect the possibility that the political significance of emigration may not only depend on one’s own ‘lived’ experience, but also on broader assessments of the predicament of the state and nation; that is, sociotropic considerations – something that has been shown to matter greatly regarding immigration (Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014).

While it is reasonable to assume that the most affected locales are also those where the issue of emigration matters the most electorally, in this paper we also want to examine the possibility that increasingly high levels of emigration may become a topic of wider public debate at certain times (such as during electoral campaigns); therefore, the significance of the issue may potentially go beyond the localities directly affected by emigration – an aspect that studies relying on objective indicators do not fully capture.Footnote 2 To fill this gap, we use a cross-national comparative analysis of public attitudes related to emigration drawing on data produced in the context of an original survey (see below).

Furthermore, we aim to move beyond the somewhat narrow framing of emigration as an issue that presumably benefits anti-establishment parties, particularly PRR parties (Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Dehdari, Laitin, Marbach and Vernby2025; Lim Reference Lim2023; Otteni et al. Reference Otteni, Mendes and Herold2024; van Leeuwen et al. Reference van Leeuwen, Halleck Vega and Hogenboom2021). While we acknowledge an affinity between the emigration issue and far-right populist discourse and positions, we view emigration as a multidimensional issue that can be approached in various ways by diverse political actors (see also Roos et al. Reference Roos, Nagel, Kieschnick and Cherniak2025). Consequently, parties across the political spectrum could potentially benefit from it. At the same time, however, it is also important to consider which political parties are most harmed by public concerns over emigration. Therefore, we theorize the pathways along which these positive or negative relationships manifest. Finally, we also examine alternatives to the role of partisan ideology – in particular, the extent to which government and opposition patterns may explain some of the variation in the association between worries about emigration and voting intentions.

We test our hypotheses on original survey data collected in the context of the research project Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics: Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU post-2008 (SOLID) and fielded in 2021. The survey was conducted in 15 EU countries from all macro-regions of the EU at different levels of economic development, some of which are countries of net emigration of intra-EU mobile citizens, while others are countries of net immigration. While we make use of descriptive data to illustrate the variation in the salience of emigration across the entire sample, we only conduct our analyses for countries where emigration is an objectively important phenomenon; that is, in nine EU peripheral member states: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Spain. We ask whether – and if so, to what extent – concerns about emigration affect voting in contemporary European political systems, and we assess comparatively the impact of attitudes towards emigration on electoral competition.

We argue that concerns over emigration can be electorally consequential: they are expected to increase support for radical-left and radical-right parties while disadvantaging governing parties and creating opportunities for challengers. Unlike much of the existing scholarship, we do not find a systematic link between emigration concerns and support for PRR parties at the aggregate level, although country-level analyses suggest that such an association may emerge in specific contexts. Moreover, the negative relationship between emigration concerns and support for governing parties proves to be conditional: it is particularly pronounced among individuals with high levels of political trust. In sum, emigration has the potential to become a politically mobilizing issue, yet its behavioural effects are contingent on party-system dynamics and the moderating role of political trust.

The electoral consequences of emigration attitudes

Paradoxes of free movement in the EU

The EU is a particularly relevant context in which to examine the political consequences of emigration, as it facilitates mobility across its member states by ensuring that EU citizens (with some preconditions) enjoy equal treatment with nationals in all member states regarding access to employment, working conditions and all other social and tax advantages (Schelkle Reference Schelkle2017). While Europeans move for many reasons, the primary motivation for intra-EU migration is to seek employment (Meardi Reference Meardi2013). According to the latest available data for the year 2023, 10.1 million working-age EU citizens and 13.9 million citizens of all ages reside in an EU country that is not the same as their country of citizenship (European Commission 2025: 13). Moreover, given the large differences in the levels of economic development and terms of employment, mobility patterns are heavily skewed, taking place largely from South to North and from East to West and South (European Commission 2025).

This system holds many potential benefits for individual migrants as it gives them a chance to improve their living and working circumstances significantly by migrating to a different EU member state,Footnote 3 and for net receiving member states whose economies seem to profit from mobility overall (see Meardi Reference Meardi2013 and the references therein). However, the balance of costs and benefits for sending states and regions is more mixed, because although emigration creates some gains from remittances sent home by migrants and alleviates unemployment rates, it also produces human capital flight, skill shortages and fiscal gaps (Alcidi and Gros Reference Alcidi and Gros2019). Ultimately, therefore, freedom of movement constitutes a regressive channel of redistribution within some European regions (Schelkle Reference Schelkle2017).

Intra-EU mobility rates picked up after the 2004 and 2007 Eastern enlargements, especially once the transitional controls on the employment of workers put in place by most ‘old’ member states were lifted in the early 2010s (Ruhs Reference Ruhs2015). Southern European countries registered a sharp increase in emigration rates in the aftermath of the euro area crisis, and high levels of emigration have persisted even in the post-crisis years (Lafleur et al. Reference Lafleur, Stanek and Veira2017). High rates of emigration further exacerbate population decline owing to persistently low levels of fertility, which are especially pronounced in net emigration countries. Thus, even though freedom of movement in general has enjoyed very strong support in the southern and eastern member states, more recently there have also been flare-ups in the politicization of the emigration issue across these regions, in the form of citizen protests or during electoral campaigns in certain countries, while some governments have introduced policies seeking to attract emigrants back home (Kyriazi et al. Reference Kyriazi, Mendes, Rone and Weisskircher2023).

Just how extensive the politicization of the emigration issue has been across countries and over time, however, is hard to ascertain due to the lack of systematic data. Cross-national surveys (such as Eurobarometer or the European Social Survey) that are suitable for large-scale comparisons rarely, if ever, ask people about their opinions on emigration. Those which have done so have found high levels of concern in countries where emigration is an objectively important phenomenon (Kustov Reference Kustov2022; Rice-Oxley and Rankin Reference Rice-Oxley and Rankin2019). Our original public opinion survey conducted in the context of the SOLID project also contributes to filling this knowledge gap, by measuring respondents’ levels of concern about emigration in several European countries.

Before proceeding, however, we shall answer the following question: why would emigration-related attitudes be linked to voting behaviour and in what way?

Mechanisms linking emigration (concerns) and voting behaviour

Practically ubiquitous in the literature is a distinction made between two mechanisms through which it is assumed that emigration influences elections in sending countries (e.g. Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Dehdari, Laitin, Marbach and Vernby2025; Lim Reference Lim2023; Otteni et al. Reference Otteni, Mendes and Herold2024). First, a compositional mechanism links emigration and voting outcomes, because ‘stayers’ and ‘movers’ systematically differ in certain politically relevant attributes: those who emigrate tend to be on average younger, better educated and politically more progressive than those who are left behind.Footnote 4 Second, emigration is thought to affect the opinions and attitudes of the ‘stayers’. Studies from various disciplines hint at the psycho-social processes that underlie the predominantly negative downstream effects of emigration on those left behind, including worries about the sustainability of traditional values and local communities and/or feelings of abandonment and a sense of cultural loss (Marchetti‐Mercer Reference Marchetti‐Mercer2012).

Furthermore, emigration contributes to ‘sorting’; that is, it makes social networks less heterogeneous in general and (re)produces traditional attitudes in particular as people lose opportunities to interact with diverse, presumably more cosmopolitan and open, views (Lim Reference Lim2023). Finally, due to emigration, the quality of life in certain locales may deteriorate, as the public services that often require a critical mass of users to sustain them (educational and cultural institutions, public transport, etc.) decline. Residents may interpret this as a symptom of a more general abandonment and neglect of their plight by the political elites (Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Dehdari, Laitin, Marbach and Vernby2025).Footnote 5

It is generally conjectured that all these attitudinal changes increase the electoral appeal of PRR parties because of the latter’s twin appeals to both anti-establishment sentiment and traditional nationalist values. Rafaela Dancygier et al. (Reference Dancygier, Dehdari, Laitin, Marbach and Vernby2025) and Junghyun Lim (Reference Lim2023) have found this to be the case in Sweden and in seven central and eastern European countries, respectively. However, the question is far from settled, as other case studies complicate this picture. Eveline van Leeuwen et al. (Reference van Leeuwen, Halleck Vega and Hogenboom2021), for example, do not find evidence of a ‘populist voting markup’ in areas of (expected) population decline in the Netherlands; and Álvaro Sánchez-García et al. (Reference Sánchez-García, Rodon and Delgado-García2025) find that in Spain, depopulation has benefited mainstream parties as much as PRR parties and, indeed, they document increased support for the Spanish Conservatives in left-behind regions. A more nuanced analysis leads these authors to conclude that depopulation has heterogeneous effects across regions and over time and is also strongly related to municipality size (Sánchez-García et al. Reference Sánchez-García, Rodon and Delgado-García2025; van Leeuwen et al. Reference van Leeuwen, Halleck Vega and Hogenboom2021).

As is evident from this overview, existing studies typically focus on the impact of emigration at the local level. We also test the extent to which emigration is a meaningful predictor of political behaviour along a scale of first-hand experience or affectedness: at the country level, we would expect the link between emigration-related worries and voting intention to be stronger in contexts in which emigration is an objectively sizeable phenomenon; within countries, it could be the case that the electoral relevance of emigration concerns is stronger in rural areas – from where many people tend to emigrate – than in urban zones, where people tend to concentrate instead.

But we also want to make the case that the electoral significance of emigration-related attitudes can scale up to the national level. After all, people can form their attitudes through second-hand experiences, based on mediated accounts and portrayals. Even for those personally affected by emigration, it is questionable whether this fact alone is a sufficient driver of their attitudes and behaviour: it is more likely that citizens rely to a lesser or greater extent on some form of sense-making process that attaches meaning to a problem, rendering it potentially actionable. Various factors, such as focusing events (Kingdon Reference Kingdon2014), can shape perceptions of an issue; for instance, the publication of a noteworthy report or a (series of) protest actions. Emigration-related narratives (defined as generalizable, constructed and selective depictions of reality) are then fabricated and diffused, setting the terms of the ensuing policy debate (Dennison Reference Dennison2021).

Who benefits and who loses out when emigration is salient?

Societal trends influence both public issue salience – that is, the extent to which people are concerned about certain issues – and the party system issue agenda, ultimately shaping the vote share of parties (Dennison and Kriesi Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023). In plain terms, in places where emigration is a sizeable phenomenon, voters are likely to attach particular importance to the issue, measured as having relatively high salience. Politicians in part follow voters, and in part they react to the same societal trends as voters, by also taking up the issue of emigration and adopting policy positions on it. However, emigration is a peculiar issue, in that the space for taking different positions on it is small.

While emigration could be framed positively – whether as the departure of an ‘unwanted’ minority, as a source of economic benefit through increased remittances, or as an opportunity for cosmopolitan experiences – it is rarely (if ever) presented this way by political parties in the current European context. Most cast it as an economic and/or cultural loss resulting from social injustice and hence symbolizing failure. Further, the extent to which a political party can benefit or lose out from the demand-side salience of any issue depends on issue ownership broadly defined. This derives from differences in the importance attached to the issue (as indicated by the extent to which a party talks about it); different ways of framing the question and the extent to which problem diagnoses resonate; and the perceived competence of a party to tackle the issue (see Dennison and Kriesi Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023).

The public salience of immigration has been linked to the increased vote share of the radical right and a reduction in that of conservative, social democratic and radical-left parties (Dennison and Kriesi Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023: 2). Empirical results are, however, still inconclusive when it comes to the issue of emigration. At a very basic level, we confront the problem of the lack of data: objective indicators (such as the emigration rate) are available for measuring societal trends, and our original public opinion survey captures demand-side salience, but not specifically perceptions of the competence of parties. More problematically, we have no systematic evidence regarding parties’ programmatic offers and issue ownership on emigration, as data sets such as the Manifesto Project and the Chapel Hill expert surveys focus solely on immigration and do not track parties’ positions on emigration.

We are therefore unable to directly match the demand and supply sides. However, we can theorize the potential ways in which political supply can meet demand. To do so, we draw on evidence from country case studies and small-N comparisons, as detailed in the next section. Individually, these case studies provide high internal validity, and taken together, they also point to more general patterns that extend beyond idiosyncrasies.

Uniquely in the literature, Christof Roos et al. (Reference Roos, Nagel, Kieschnick and Cherniak2025) provide a systematic classification of how political parties frame the issue of emigration along two main axes of political conflict: socio-economic and cultural. Nonetheless, here we focus more directly on theorizing the link between party framing, positions and electoral appeal. The units of our analysis are party families (Radical-left, Green, Socialist, Liberal, Conservative, and Radical-right) which group parties according to their ideological profiles. These profiles reflect configurations of policy positions across three core dimensions: economic distribution, political and social governance, and polity membership status, as outlined by Herbert Kitschelt (Reference Kitschelt2018). Parties’ stances on emigration are expected to vary depending on both their ideological orientation and whether their electoral appeal is broad or niche.

Below, we consider which families could benefit or lose out from the salience of the emigration issue. In thinking this through, we challenge the assumption that emigration can only play into the hands of PRR parties and consider broader possibilities.

How parties engage with emigration: hypotheses

Emigration is a multidimensional issue, but one possibility is to cast it as a primarily socio-economic matter, which potentially benefits left-wing parties. From this perspective, emigration is denounced as a symptom of weak welfare states and a lack of opportunities in one’s country, driven by unemployment, precarity and the lack of a social safety net. Emigration becomes integrated into the repertoire of social problems that the left seeks to solve with increased redistribution and a socially sensitive agenda. The available qualitative evidence suggests that this is a fairly characteristic way of seeing emigration on the left, as the following quote by a Spanish PSOE Member of Parliament (MP) demonstrates:

These are young people who are disenchanted and who live with the agony of not seeing any alternative. No alternative but that of exile in order to have a professional future. […] This is a generation that moves in a trilogy: unemployment, precarious employment and economic exile. (Cited in Mendes Reference Mendes and Vorländer2021b: 174)

A further distinction between centre-left, social democratic and radical-left parties is warranted. Despite the quote above, social democrats are generally unlikely to ‘own’ the issue of emigration or devote significant attention to it, as it may get lost in their wide-ranging policy agenda. Additionally, these parties tend to support freedom of movement, multiculturalism and European integration, and commitment to these liberal principles may obfuscate their emigration-related messaging. On the radical left, however, a similar but more far-reaching critique can be offered more authentically in response to these worries about emigration, as the focus here is more on inequality both within and among states at the European level, and less on individual freedoms, the advantages of mobility and a cosmopolitan outlook. The example here is from Mera25, a Greek radical-left party:

Greece has expelled its children many times in our history, pushing them to emigrate. Today, after some decades when we had believed that this flow had stopped, the Debt Serfdom regime is driving hordes of young people abroad, contributing to the desertification of the country. (Mera25 2019, translated by the authors)

The politicization of emigration is also potentially more effective on the far-right side of the political spectrum, which embraces nationalism and traditional values and decries cultural change. Framed as a cultural issue, emigration may be interpreted as a threat to the values and continued existence of the nation, an understanding whereby emigration may also be linked to immigration and even to worries about demographic replacement. For example, in its 2014 party programme, the Polish national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party stated:

Among all the challenges facing Poland in the next decade, the most important one is to avoid the collapse of civilization caused by the depopulation of our country. (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS) 2014: 107)

The big advantage of the PRR parties is their ability to fuse the issue of emigration with another key issue they already ‘own’, namely immigration. Furthermore, they can integrate cultural and socio-economic components too, advocating both a more generous social policy and cultural closure (analogously to the welfare chauvinistic impulse).

Like social democrats, conservative parties may also find it more difficult to address the issue of emigration effectively. Given their general support of market freedoms, EU integration and individual autonomy, such parties have a limited repertoire of arguments at their disposal. Focusing on utilitarian, pragmatic aspects such as the cost of human capital flight is a way to square the circle, as the following quote from the Polish Civic Platform (PO) suggests: ‘Poland must cease to be a “factory” of specialists for other countries’ (PO 2019: 56, cited in Roos et al. Reference Roos, Nagel, Kieschnick and Cherniak2025: 172). At the same time, taking the analogy of immigration, the conservatives in most places are probably not perceived as the most competent and credible party to tackle the issue of emigration (see Dennison and Kriesi Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023), which can arguably get lost in their broader economic and social agenda. These parties are more likely to be catch-all ones, meaning that they have a wide programmatic offer in which emigration (which is already a relatively niche issue in most contexts) is unlikely to stand out from their agenda.

Finally, according to our reconstruction, liberal and green parties will be the least able to benefit from emigration-related worries, and we expect the effect of emigration concerns on their electoral support to be either null or negative, given these parties’ support for economic and cultural liberalism, respectively, along with a muted inclination for economic redistribution. Unlike the moderate right and left, such parties make niche appeals, but the issue of emigration is not typically part of these.

We also consider the possibility that concerns about emigration could be linked to general voter disaffection with the performance of a country, triggering lower political trust and greater dissatisfaction, which in turn may result in a higher probability of abstention among those with high levels of concern (Grönlund and Setälä Reference Grönlund and Setälä2007).

Hypothesis 1: Voters concerned about emigration are more likely to vote for radical-left and radical-right parties and/or have a higher probability of abstention.

Hypothesis 2: Voters concerned about emigration are less likely to vote for green, social democratic, liberal or conservative parties.

The hypothesis regarding abstention brings us to a second, related but distinct line of inquiry, which examines how emigration concerns are associated with support for governing versus opposition parties. We could expect emigration concerns to feed into a broader dissatisfaction with parties in government, irrespective of their partisan colour. Emigration within the EU can be seen as a powerful signal of government failure because individuals are choosing to leave their homes and communities in search of better opportunities elsewhere, suggesting that their needs are not being met by their home state (Moses Reference Moses2017).

This is all the more plausible because Europeans from Central Europe primarily migrate for economic reasons, such as seeking higher incomes and better working conditions, unlike western Europeans, who often move due to lifestyle factors. Dissatisfaction with wages, job security and weak social protections in new EU member states drives migration, with countries that have poorer welfare systems experiencing the highest outflows (Kureková Reference Kureková2013; Meardi Reference Meardi2013). Even more obviously, the crisis migrations from the South were spurred by difficult economic conditions, including rampant youth unemployment (Lafleur et al. Reference Lafleur, Stanek and Veira2017; López-Sala Reference López-Sala, Glorius and Domínguez Mújica2017; Mendes Reference Mendes and Vorländer2021a, Reference Mendes and Vorländer2021b). Voters’ worries about the exit of citizens from their country of origin to other EU member states could negatively impact the evaluation of government performance and perceptions of the competence of the governing party, as voters hold the latter responsible for failing to accomplish the task that is widely considered the most basic of all: to provide the conditions for people to build their lives in the country where they were born. Evidence that emigration concerns increase support for welfare spending suggests that citizens interpret large-scale exit as a signal of collective vulnerability and institutional insufficiency (Kyriazi and Visconti Reference Kyriazi and Visconti2025), which may in turn feed into electoral punishment of incumbents.

Existing case studies provide a variety of examples of opposition parties using ‘emigration as a blaming tool’ (Mendes Reference Mendes and Vorländer2021a: 140), and such criticism can be levelled from across the political spectrum. Illustrative examples can be drawn from a left-wing MP in Hungary and from Giorgia Meloni, currently the Prime Minister of Italy and at the time an MP of Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy):

You know, fellow Members of Parliament, […] children are born in countries where it is good to live. Where it is not good to live, no children are born […] The declining birth rate shows this, and so do the embarrassing emigration figures. 600,000 people, 600,000 adults of childbearing age went abroad from Hungary because they do not see the possibilities of having children or making a living at home. (Hungarian National Assembly, Plenary Session, June 4, 2018, cited in Kyriazi Reference Kyriazi and Vorländer2021: 91)

The Italian governments have clearly shown that they do not care that Italians are leaving their country. They can replace Italians with immigrants anyway. (Giorgia Meloni, cited in de Ghantuz Cubbe Reference de Ghantuz Cubbe and Vorländer2021: 112).

Governing parties, in turn, are constrained in dealing with the issue of emigration: intra-EU emigrant populations present a set of complex challenges for incumbent governments, and policymakers have struggled to respond effectively to them (Waterbury Reference Waterbury2018). They face limitations when it comes to implementing policies that opposition parties may freely advocate (such as emigration controls): governments cannot legally stop people from leaving, nor can they compel them to return. Some governments have resorted to programmes incentivizing return, which are both limited and targeted (at high-skilled emigrants or young people, for example), and whose effectiveness is unclear but probably minimal (Kyriazi et al. Reference Kyriazi, Mendes, Rone and Weisskircher2023).

In some instances, executives have even committed blunders, such as in late 2012 in Spain when the then Secretary-General of Immigration and Emigration in Mariano Rajoy’s PP government, Marina del Corral, insisted that emigration should be seen as something ‘essentially positive’, as qualified Spanish workers ‘have finally stopped being local’ (cited in Mendes Reference Mendes and Vorländer2021b: 173) – a claim that sparked both heated debate and critical commentary. The awkwardness with which governments address the issue of emigration was also evident in the 2020 Romanian parliamentary election. The Romanian government has shown persistent ambivalence towards emigration, and there was a widespread perception of disrespect towards emigrants, especially during the pandemic. This ultimately undermined support for the government and benefited the far right in those elections, primarily through the mobilization of the diasporic vote (Ulceluse Reference Ulceluse2020).

In confronting a policy problem for which there are no easy solutions, governments may find it most beneficial to depoliticize emigration altogether, downplaying the issue and not treating the absence of emigrants as something to be rectified. However, this opens governments up to another type of criticism: inaction and indifference (see López-Sala Reference López-Sala, Glorius and Domínguez Mújica2017). Even when they are compelled to react, their solutions are partial and probably ineffective. People worried about emigration may therefore punish governing parties (including junior coalition partners) for this perceived lack of competence and failure to improve a country’s socio-economic conditions, irrespective of partisan colour.

Hypothesis 3: Voters concerned about emigration are less likely to vote for parties in government.

Data and methods

The analyses are based on survey data collected within the SOLID project. The survey was conducted by Gallup in the summer of 2021 in Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain and Sweden. We limit our analysis to the nine countries of emigration in the South and East. For each country, about 1,000 respondents were interviewed based on quotas for gender, age, education and area of residence. More information about the survey is available in the Supplementary Material online.

Dependent variables

We test our hypotheses through two different dependent variables built starting from the voting intention of respondents. The latter is based upon the typical survey question: ‘If there were a general election held tomorrow, for which party would you be most likely to vote?’ Respondents could choose among the most important available parties or could specify another party of their choice. Finally, they could choose between the following options: ‘I will vote blank/null’, ‘I would not vote’, ‘I prefer not to say’ and ‘Don’t know’.

The first dependent variable consists of a binary item tracking whether a survey respondent expressed the intention to vote for a party in government at the time of the fielding of the survey (or not), while for the second one, the voting declarations of survey respondents for national parties that contested elections in nine sample countries were grouped into seven party families: Radical-left, Green, Socialist, Liberal, Conservative, Radical-right and no family (the residual category). The status and party family of parties are classified based on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022) and the ParlGov Database (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2021). The full list of parties included in the survey along with their government status and family is available in Table A1 in the Supplementary Material.

Independent variables

The main independent variable is the survey respondents’ level of concern with emigration (demand-side salience), as measured through the following question: ‘Now think about the freedom of movement in the EU. How concerned are you about [NATIONALITY] citizens who emigrate to other EU countries’? Answers are given on a 0–10 scale ranging from ‘0 – not concerned at all’ to ‘10 – extremely concerned’. This measurement strategy presents two main problems. First, even though our measure is closer to indicating individual salience rather than a preference for migration policy, ultimately it does not allow us to explicitly differentiate between intensity and preference, which could have different causes and consequences (Dennison and Geddes Reference Dennison and Geddes2019; Hatton Reference Hatton2021). However, as previously mentioned, unlike with immigration, the variance in policy positions on emigration is relatively limited, since most voters and politicians consider it to be a negative phenomenon to be curtailed. Second, because respondents do not have to pick the issue of emigration from a list of issues, we are likewise unable to gauge its salience relative to other potentially important matters (see Dennison and Kriesi Reference Dennison and Kriesi2023).

Having established these caveats, we now turn to our descriptive results. Figure 1 plots the density estimates for each separate country for concerns about emigration along with the country average (vertical dotted line). We find that, on average, respondents are somewhat worried about people emigrating to other EU countries, though there are large regional differences. On average, respondents in western and especially northern European countries worry far less about emigration than those in eastern and southern European countries. Hence, we limit our analysis to nine countries of emigration on the periphery of the EU where individual issue salience is relatively high. The one exception is Ireland, where the average level of concern is on a par with that of France and the Netherlands, but where actual emigration rates are still comparatively high.Footnote 6

Figure 1. Distribution of Concerns about Emigration by Country

Limiting the set of countries is conceptually warranted for at least two reasons: on the one hand, by excluding western European states we reduce heterogeneity in our sample at the level of the party system, especially given that the basic structures of party competition in the East and West are fundamentally different (De La Cerda and Gunderson Reference De La Cerda and Gunderson2024; Marks et al. Reference Marks, Hooghe, Nelson and Edwards2006); on the other hand, respondents who express a higher level of worry in contexts where emigration is not an objectively sizeable phenomenon are presumably using this question as a proxy for wider dissatisfaction with human mobility in its various forms and/or the EU mobility regime writ large. Their inclusion in the analyses may therefore introduce systematic bias in the results.

Control variables

We explore the association of concerns over emigration in our sample countries through multivariate regressions controlling for other predictors of voting intention. In particular, we evaluate the association between concerns over emigration and voting behaviour net of gender (female = 1; male = 0); age (18–34; 35–54; 55+); education (low; middle; high); employment status (0 = not unemployed; 1 = unemployed); type of residence (urban = 0; rural = 1); economic insecurity (0 = not difficult to cope on household income; 1 = difficult to cope on household income); sociotropic evaluation of the economy (0 = improved/the same; 1 = worsened); an index of political trust built using three items rating trust in the country’s legal system, politicians and political parties (rescaled to range between 0 and 1); left-right self-placement recoded into six categories (left = 0, 1; centre-left = 2, 3; centre = 4, 5, 6; centre-right = 7, 8; right = 9, 10; not located = ‘Doesn’t know/Refuse to locate’) and support for more EU integration (0–10). The empirical analyses are run on the data set pooling the nine sample countries together; country dummies are therefore included (with the reference category being Italy) to control for country-specific time-invariant effects.

Results

The empirical analyses demonstrate that, in 2021, concerns over co-nationals emigrating to another EU country were significantly associated with voting choices. Overall, the extent to which voting intentions are related to worries about emigration only partially aligns with our expectations.

Party family

We first present results related to voting for a specific party family. Given the categorical nature of the dependent variable – the party family respondents declared themselves willing to vote for in the next national elections – the analyses are based on a multinomial regression model in which respondents’ voting intention is regressed on the main explanatory variable – concerns about emigration – and controls. The model has the Conservative party family as the reference category.

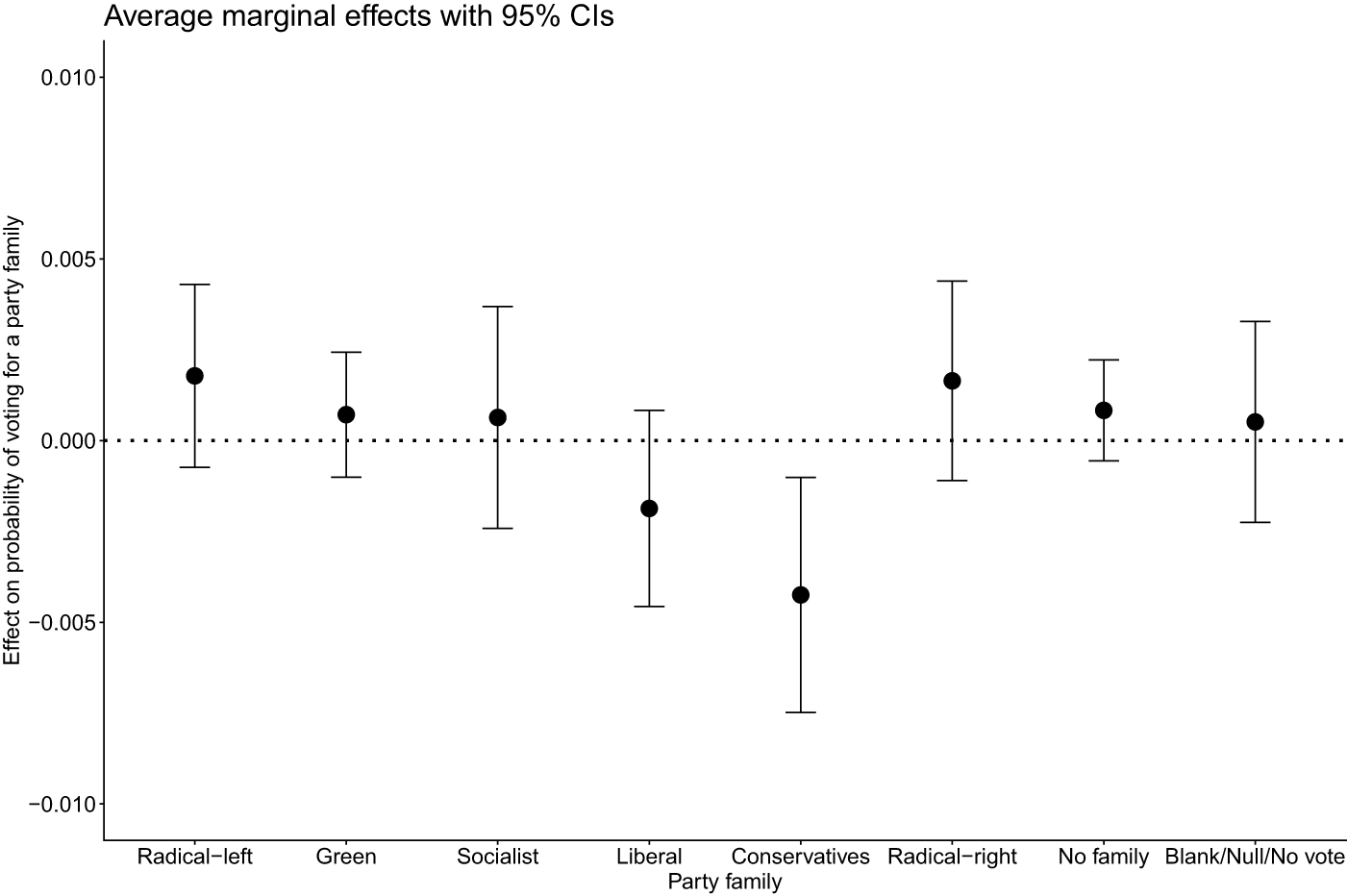

Figure 2 shows the main results in the form of a graph plotting the change in the predicted probability of voting for different party families resulting from a one-unit change in the main independent variable – concern over emigration – while controlling for the effect of all the control variables. Positive values, found above the horizontal zero line, indicate that greater worries about emigration are associated with an increase in respondents’ propensity to vote for a specific party family, while negative values, below the horizontal zero line, indicate that increased worries about emigration decrease respondents’ propensity to vote for a party family. The figure displays the 95% confidence intervals. Readers interested in the multinomial regression coefficients should refer to Table A3 in the Supplementary Material online, which provides full estimates of the voting choice for different party families at changing values of all the covariates included in the model.

Figure 2. Average Marginal Effects of Concerns about Emigration on Voting for a Party Family

We argued that concerns about emigration should be associated with increased support for radical-left or radical-right parties, given that social democratic, conservative, liberal and green parties generally favour freedom of movement and are less likely to ‘own’ the migration issue, hence their voters should be less concerned about emigration. The empirical results lend only partial support to our hypothesis. A one-unit increase in concerns about emigration (0–10 scale) is significantly associated with a lower predicted probability of voting for a party belonging to the Conservative party family. Overall, then, concerns over emigration particularly penalize those parties that are in favour not only of freedom of movement but also of a European integration that is market-making rather than market-correcting. Conservative parties often promote market liberalization, austerity and privatization – policies that may fuel a brain drain – leading voters who feel left behind to penalize them at the ballot box. No significant association emerges when looking instead at the average marginal association with being inclined to vote for parties belonging to the PRR family. Also, concerns about emigration do not appear to signal general voter disaffection, given that they are not associated with a higher probability of abstention or a blank or null vote.

Subsequently, we look at whether there is heterogeneity across different countries in the association between concerns over emigration and voting intention. To do so, in Table 1 we present the average marginal effects within each of the nine countries considered, based on the values of the regressors. To facilitate interpretation, the table only reports estimates that are statistically significant at the 10% level (with those which are significant at the 5% level in bold). The country-level results are less robust due to the low (or null in some instances) number of observations for some party families (see Table A2 in the Supplementary Material for an overview of the total number of respondents by party family and country).

Table 1. Country-specific Average Marginal Effects of Concerns over Emigration

Note: Estimates in bold are significant at the 5% level. Full regression coefficients of the country-specific models are available in Table A4 of the Supplementary Material.

Nevertheless, we found more significant results in line with our expectations. Indeed, concerns about emigration are associated positively with a greater propensity to vote for parties belonging to the Radical-right family in four countries: Greece (Golden Dawn), Poland (Kukiz’15), Ireland (AON) and Hungary (Jobbik and MHM). Emigration-related concerns are negatively associated with voting for the Hungarian Fidesz party. Note, however, that this is classified as a radical-right party based on its ideological profile. Notwithstanding, it has been in government since 2010, presiding over considerable emigration of citizens to other EU countries. We also find a positive association with support for the Italian Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S), which combines an anti-establishment identity with an elusive positioning on the issues of citizenship and migration (Mosca and Tronconi Reference Mosca, Tronconi, Caiani and Graziano2021).

Intention to vote for the Radical-left family, however, is not positively associated with emigration concerns in any of the countries studied, except Poland (Lewica). In Greece, concerns about emigration are associated with an increased probability of voting for the radical-left SYRIZA or with a decrease in electoral participation, which is in line with our first hypothesis. The opposite is true for Romania, where being concerned about emigration decreases the probability of abstention, blank or null. This may reflect the particular moment in which our survey was fielded, half a year after the 2020 elections, when emigration had emerged as an important issue (Ulceluse Reference Ulceluse2020). The Conservative party family is associated negatively with concerns over emigration in Portugal (CDS-PP), and fears over the exit of citizens to other EU countries are linked with an increased probability of voting for a Socialist-led party alliance (MSZP-Párbeszéd-LMP) or Liberals (Együtt) in Hungary.

Overall, the most consistent finding is that PRR parties are the best placed to benefit from emigration-related concerns, yet it is possible that the demand-side salience of emigration can benefit parties from across the ideological spectrum. Concerns over emigration certainly do not work to the advantage of centrist parties with mass appeal in any of the countries studied: it is always smaller, niche parties that benefit from it. Our results suggest that the association with country-specific party systems should be studied in greater depth and that the electoral relevance of emigration should be examined on a case-by-case basis.

Voting for parties in government

Table 2 presents the results from three logistic regression models predicting the likelihood of voting for a governing party, with a focus on the role of concern over emigration. Models 1 and 2 differ because the latter includes political trust as a confounder. While Model 1 shows that concern over emigration has no significant association with voting for the incumbent, once political trust is introduced in Model 2, the log-odds coefficient for being concerned about people moving to other EU countries is statistically significant and negative (−0.03). This means that a one-unit change in worries about emigration reduces the probability of voting for a party in government by 0.03. Including political trust markedly improves the model fit, as seen in the reduction in AIC and RMSE values.

Table 2. Coefficients (And Standard Errors) from Logistic Regression on Voting for a Party in Government

+ Note: p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

The comparison between Models 1 and 2 highlights the need to further explore how concern about emigration and political trust jointly influence support for governing parties. Model 3 addresses this by introducing an interaction between the two variables, which reveals a significant negative association (coefficient = −0.173, p < 0.01), suggesting that concern about emigration harms support for parties in government only for voters with higher levels of political trust. In substantive terms, concern about emigration constrains the electoral returns of trust: individuals who are more worried about emigration are less likely to translate high trust into support for the incumbent. While political trust generally enhances support for cabinet parties, this effect is significantly weakened in contexts where emigration is a salient issue, particularly among the most concerned.

As can be seen in the predicted probability plot (Figure 3), individuals with low political trust show consistently low and stable support for governing parties, regardless of their emigration concerns. In contrast, among those with moderate or high trust, support declines markedly as concern over emigration rises. Notably, individuals with high trust initially display the greatest likelihood of supporting the incumbent, but this support drops by approximately 15 percentage points from the lowest to the highest level of concern. These findings underscore a conditional association of concern over emigration, in which the level of trust in the national government moderates the otherwise negative association between concern over emigration and electoral support for governing parties.

Figure 3. Predicted Probability of Voting for a Party in Government over Concerns about Emigration by Levels of Political Trust

To test for heterogeneous effects across countries, Figure 4 displays the predicted probability of voting for a governing party across levels of concern over emigration, differentiated by levels of political trust (low = 0.25, high = 0.75) for each of the nine countries in which emigration is a more salient issue (full regression results are available in Table A5 in the Supplementary Material).

Figure 4. Predicted Probabilities of Voting for a Party in Government over Levels of Concern about Emigration by Levels of Political Trust by Country

The results show notable cross-national heterogeneity in the interaction between concern over emigration and political trust. In most countries, a higher level of concern over emigration tends to decrease the likelihood of supporting governing parties, particularly among individuals with high political trust. This negative association is most pronounced in Hungary, Latvia, Romania and Spain, where trust typically boosts incumbent support, but this effect is significantly weakened as concern about emigration increases. In Ireland, a distinct pattern emerges: while low-trust individuals exhibit a positive relationship between concern over emigration and incumbent support, high-trust individuals display a slightly declining trend, suggesting an even more pronounced moderation. In contrast, in Italy, Poland and Portugal, the predicted probabilities for high- and low-trust individuals do not significantly diverge as concern over emigration increases. Overall, these results reveal that the electoral pay-off of concern over emigration is conditioned by voters’ political trust. In several national contexts, emigration concerns appear to undermine the political returns of trust, highlighting its salience as a politicized issue and potential source of dissatisfaction with governing elites.

The clearest example in our analysis of this tendency is Hungary. The five statistically significant effects we saw in Table 1 show concerns over emigration being associated with a decreased probability of voting for the long-time incumbent, FIDESZ-KDNP, and a positive association not only with the country’s two radical-right parties, Jobbik and its splinter even further to the right, Our Homeland Movement (MHM), but also with the liberal Együtt and a left-wing party alliance led by the Socialists (MSZP) that was formed for the 2020 elections.

As Anna Kyriazi (Reference Kyriazi and Vorländer2021) documents, emigration has indeed become a politically salient and emotionally charged issue in Hungary, particularly since 2010, when outward mobility accelerated sharply. Parliamentary records show a marked increase between 2010 and 2019 in references to emigration, especially by Jobbik MPs, who used the issue to attack the Fidesz-led government for driving young and skilled citizens out of the country. Less frequently, but still relevantly, left-leaning parties such as MSZP and the green-liberal Politics Can Be Different (LMP – now LMP Hungary’s Green Party) also took up the emigration issue, framing it as a symptom of socio-economic failure and often linking it to low wages, a declining welfare state and a lack of prospects for the younger generation (Kyriazi Reference Kyriazi and Vorländer2021). Fidesz’s response has largely been to downplay emigration, avoiding direct engagement with the issue and instead shifting public attention towards the alleged threat of immigration (Kyriazi Reference Kyriazi and Vorländer2021).

These findings complicate the argument that emigration, enabled by the EU’s free movement regime, has strengthened Hungary’s increasingly authoritarian government (Kelemen Reference Kelemen2021). They indicate that, at the national level, compositional and attitudinal mechanisms may operate in opposing directions. On the one hand, as the incumbent fails to meet public expectations, some dissatisfied citizens choose to emigrate, potentially removing critics of the ruling elites and thereby reinforcing their grip on power. On the other hand, the citizens ‘left behind’ may interpret this emigration as a sign of failure and hence become disillusioned with the government: the exit of the dissatisfied generates dissatisfaction over their exit. All else being equal, this dynamic could benefit opposition parties.

Controls

Turning to the control variables, the results are broadly consistent across the models. Older individuals, particularly those aged 55 and above, are significantly more likely to vote for a governing party than younger respondents are. Gender and levels of education do not show any consistent association. Unemployed respondents are less likely to support incumbents in Model 1, but the effect weakens when political trust is included. Political orientation has a strong and consistent effect: individuals identifying as centre-right or right are significantly more likely to support governing parties than centrists are, while those not placing themselves on the ideological scale are less likely to do so. In line with previous works, distrust tends to channel votes towards protest or opposition parties.

In our analysis, support for further EU integration significantly predicts voting for governing parties only in Model 1, but loses significance once political trust is introduced, suggesting that Eurosceptic attitudes are closely linked to broader political dissatisfaction and declining trust in institutions. Retrospective evaluations of the national economy are also highly significant, with negative assessments associated with reduced support for the incumbent. Neither urban nor rural residence has a significant effect, indicating that concerns about emigration are shared broadly across the country – not just in areas with higher rates of out-migration. Finally, all country dummies are negative and significant, confirming that support for governing parties is generally lower outside the reference category of Italy – probably due to the fact that at the time the survey was fielded in Italy, Prime Minister Mario Draghi’s technocratic government was supported by basically all parties with the exception of Fratelli d’Italia.

Conclusion

The present article investigated whether voters’ concerns about emigration by their co-nationals to other EU countries are associated with voting intentions in nine European member states. The first takeaway point from the analysis is that concerns over emigration constitute a predictor of voting choice, alongside the socio-economic and attitudinal profile of European voters. Empirical analyses conducted using original public opinion data show a significant negative association with voting intention for the Conservative party family. Further, voters concerned about emigration are more likely to favour opposition parties out of government, depending on the level of political trust. This is generally in line with existing research on the supply side (Mendes Reference Mendes and Vorländer2021a, Reference Mendes and Vorländer2021b; Roos et al. Reference Roos, Nagel, Kieschnick and Cherniak2025): opposition parties on both the left and right pick up the issue of emigration, integrating it into a broader government critique. Melle Scholten (Reference Scholten2025), however, shows that emigration can also bolster governments by enlarging the elderly electorate and incentivizing pension-oriented welfare expansion. Together, these perspectives underscore a key tension: emigration may help incumbents consolidate power through redistribution, yet it can also trigger dissatisfaction and electoral punishment when concerns are politicized and fail to be met.

Analyses at the country level lend credence to the argument that emigration benefits PRR parties, again in line with some previous studies (Dancygier et al. Reference Dancygier, Dehdari, Laitin, Marbach and Vernby2025; Otteni et al. Reference Otteni, Mendes and Herold2024), although our results are quite heterogeneous overall. This suggests that the politicization of the emigration issue can benefit parties across the political spectrum, but that it depends on the temporal and geographic context.

The narrow sample of countries available, along with the limits of the survey data, undermines the generalizability of the results. Future work should expand on this theme more systematically by analysing not only the association between concerns but also preferences and voting behaviour over time and across different electoral contests and countries. Moreover, studies aligning voting intentions with data on parties’ emigration positions (sourced from political manifestos and/or media) that manage to account for the changing salience of emigration between elections, for example, would significantly advance this line of research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2025.10031.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 2023 ECPR General Conference and at the 2023 Conference of Europeanists. We are very grateful to all participants as well as to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Financial support

Our research was supported by the European Research Council under the Synergy Grant ERC_SYG_2018 number 810,356, for the project Policy Crisis and Crisis Politics: Sovereignty, Solidarity and Identity in the EU post-2008 (SOLID).

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.