Introduction

A basic feature of language is the ability to refer to entities in the surrounding world. When selecting a referring expression, speakers often make a distinction between reference to entities that are new in a given context and entities that have already been mentioned before. For example, in English, speakers tend to introduce new entities in a context by using a lexical noun phrase (Anthony, in 1) and refer to a previously mentioned entity by using a pronoun (he, in 1).

(1) While Anthony is at the park, he is feeding the ducks.

Speakers show some degree of variability in the selection of referential expressions when they speak (e.g., Arnold, Reference Arnold2010, for a review). Relative to speakers who use one language in their daily lives, adult speakers of more than one language may demonstrate variability in the nondominant language, even if they are highly proficient in that language (e.g., Contemori et al., submitted; Filiaci & Sorace, 2006; Montrul, Reference Montrul2004, Reference Montrul, Slabakova, Montrul and Prévost2006, Reference Montrul2018; Quesada & Lozano, Reference Quesada and Lozano2020; Tsimpli et al., Reference Tsimpli, Sorace, Heycock and Filiaci2004). Several factors might explain bilinguals’ variable references, including (i) reduced exposure to reference use in each language, (ii) fewer available cognitive resources when processing referential expressions in the second language (L2), and (iii) cross-linguistic influence (e.g., Sorace, Reference Sorace2011). In the present study, we examine the role of cross-linguistic influence and high proficiency for reference production in the L2 of Spanish-English and Dutch-English bilinguals.

The selection of referential expressions is influenced by several linguistic and extra-linguistic factors. One such factor is the grammatical role of the antecedents: Referents in singular subject position are more likely than referents in singular object position to be mentioned again using less specific referential forms, such as overt pronouns in English and null pronouns in Spanish. Other relevant factors are the number of antecedents and the antecedents’ gender. For instance, Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) showed that English speakers are more likely to use a noun phrase to refer to the first-mentioned/subject antecedent when there are two characters than when there is only one. Concerning the gender of the characters, Arnold and Griffin (Reference Arnold and Griffin2007) demonstrated that English speakers produce more explicit references (i.e., noun phrases) when the gender of the two characters is the same than when it is different, a result known as the gender effect. The gender effect arises because the production of an underspecified form such as a pronoun in a context where two characters share the same gender may create potential ambiguity (e.g., in the sentence “Mary met Janet when she was in high school,” it is unclear who was in high school). Nevertheless, English speakers are more likely to use noun phrases than pronouns even when two characters have different genders (e.g., Mickey Mouse and Daisy Duck), even though the use of a pronoun (he/she) would disambiguate the referents. This effect has been attributed to competition created by two similar entities in the speaker’s discourse model (Arnold & Griffin, Reference Arnold and Griffin2007).

An effect of the number and gender of the antecedents on noun phrase production has also been observed in other languages (e.g., Mexican Spanish and Italian: Contemori & Di Domenico, Reference Contemori and Di Domenico2021). Unlike English, languages such as Spanish (known as null-subject languages) use null pronouns, in addition to overt pronouns and noun phrases, as illustrated in (2). Null pronouns are usually used to maintain reference, for example, in (2) to refer to “Pedro,” the accessible antecedent that is in subject/agent position. For the variety of Spanish under investigation here (Mexican Spanish from northern Mexico), overt pronouns can be used by monolingual speakers to signal a topic shift and to maintain a topic in contexts where one or two antecedents that are the same or different in gender are presented in the discourse, as shown in (3) (Contemori & Di Domenico, Reference Contemori and Di Domenico2021). Noun phrases are also attested in similar contexts, as illustrated in (4).

(2) Pedroi platicaba mientras Ø i cruzaba la calle

[Pedro was talking while he was crossing the street]

(3) Pedroi platicaba con Ricardo mientras él i cruzaba la calle

[Pedro was talking to Ricardo while he was crossing the street]

(4) Pedroi platicaba con Ricardo mientras Pedro/Ricardo cruzaba la calle

[Pedro was talking to Ricardo while Pedro/Ricardo was crossing the street]

The role of cross-linguistic influence and high proficiency on bilingual referential choice

Cross-linguistic influence refers to the effects that the mental representation and processing of one language can have on another in multilingual speakers. The patterns of such transfer may be facilitative, neutral, or disruptive (Sharwood Smith, 2021). A type of cross-linguistic influence is cross-linguistic interference, referring specifically to negative influence, where transfer results in communication problems, ungrammaticality, or processing difficulty. Here, we use the term cross-linguistic influence to characterize transfer effects, without assuming a negative outcome. Cross-linguistic influence may arise when the languages of bilingual speakers have different sets of referring expressions and production biases. For example, Spanish-English bilinguals tend to produce more pronouns in L2 English in comparison to monolingual English speakers (a difference of approximately 15%–20% in two-referent contexts in Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016; see also Contemori & Ivanova, Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021; Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023). The higher pronoun production was observed even when the preceding discourse contained two characters of the same gender, so using a pronoun can create ambiguity (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016; Contemori & Ivanova, Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021). This difference could at least in part be due to cross-linguistic influence: Bilinguals may produce more pronouns in English under the assumption from their L1 (Spanish) that an overt pronoun is explicit enough compared to the default Spanish null form (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016). Following this logic, less cross-language influence may be expected between typologically similar languages (e.g., between two null-subject or two non-null-subject languages)—predicting that L2 reference production would be similar to that in the first language (L1) and to monolingual production. However, inconsistent with this prediction, proficient bilingual speakers of two null-subject languages still used more overt pronouns in contexts where monolingual speakers preferred to produce null-subject pronouns (L2 speakers of Spanish, with L1 Greek or Italian, and L2 speakers of Italian, with L1 Greek: Bini, Reference Bini and Liceras1993; Di Domenico & Baroncini, Reference Di Domenico and Baroncini2019; Lozano, Reference Lozano2018; Margaza & Bel, Reference Margaza, Bel, O’Brien, Shea and Archibald2006). This pattern was observed when two characters were introduced in the discourse or in contexts of topic maintenance where the use of a null pronoun would be more felicitous (e.g., Di Domenico et al., Reference Di Domenico, Baroncini and Capotorti2020; Margaza & Bel, Reference Margaza, Bel, O’Brien, Shea and Archibald2006). These results suggest that the differences in L2 and L1 reference production when the two languages are typologically similar cannot be solely due to cross-linguistic influence and could hence be due to other causes, such as added cognitive load (e.g., Sorace, Reference Sorace2016).

However, this evidence is not conclusive about the role of cross-linguistic influence for L2 speakers’ patterns of reference production. This is because null-subject languages can still differ among each other in the use of null and overt pronouns (Italian vs. Spanish: Contemori & Di Domenico, Reference Contemori and Di Domenico2021; Filiaci et al., Reference Filiaci, Sorace and Carreiras2014; Italian vs. Greek: Di Domenico et al., Reference Di Domenico, Baroncini and Capotorti2020). For instance, comparative research has shown that Italian speakers use null pronouns more consistently in reference to subject antecedents than Mexican Spanish speakers (Contemori & Di Domenico, Reference Contemori and Di Domenico2021). That is, while null-subject languages share the same set of referential expressions (null and overt pronouns; noun phrases), they do not always obey the same constraints on production, resulting in different frequency of occurrence and patterns of use across languages. Thus, it is possible that cross-linguistic influence arises even between two languages that are both null subject. To put the cross-linguistic influence hypothesis to a stronger test, it is necessary to examine the referential choices of bilinguals of two languages in which reference options are also used in similar ways in the contexts under investigation. For this reason, we examine here the L2 referential choices of Dutch-English bilinguals (which we compare to those of Spanish-English bilinguals and functional English monolinguals). In Dutch, like in English, full noun phrases can introduce a new referent in the context or can refer to a less accessible antecedent as shown in (5), while personal pronouns (e.g., hij ‘he’) are used to refer to an accessible antecedent, as shown in (6) (e.g., Hendriks et al., Reference Hendriks, Koster and Hoeks2014; Vogels et al., 2014). We note, however, that Dutch also allows the use of demonstrative pronouns (e.g., die ‘that’), as illustrated in (7). Personal and demonstrative pronouns in Dutch differ in their referential preferences: While Dutch speakers prefer to interpret personal pronouns as referring to a preceding subject, they prefer to interpret demonstrative pronouns as referring to less accessible antecedents such as objects (e.g., Kaiser, Reference Kaiser2011).

(5) Peteri praatte met Richardj terwijl Richardj de straat overstak

[Peter was talking to Richard while Richard was crossing the street]

(6) Peteri praatte met Richardj terwijl hij i de straat overstak

[Peter was talking to Richard while Peter was crossing the street]

(7) Peteri praatte met Richardj terwijl die j de straat overstak

[Peter was talking to Richard while Richard was crossing the street]

Previous research looking at bilingual adults who speak two non-null-subject languages such as Dutch and German has focused on the interpretation of personal and demonstrative pronouns in comparison to monolingual speakers of the language. This research has shown patterns in bilinguals’ pronoun interpretation that are not explained by the cross-linguistic similarity in the available set of referential expressions. Specifically, bilinguals overextend the demonstrative (perhaps similarly to overextension of overt pronouns by bilinguals of null-subject languages in other studies), although to a lesser extent at more proficient and balanced stages of bilingualism (e.g., Dutch-German: Ellert, 2011; German-Dutch: Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Gullberg and Indefrey2008; English-German: Wilson, Reference Wilson2009; see also Juvonen, 1992, for Finnish-Swedish). However, we note that these studies investigated anaphora interpretation preferences (i.e., comprehension), which may pattern very differently from referential choice (i.e., production; see Contemori & Di Domenico, Reference Contemori and Di Domenico2021, Reference Contemori and Di Domenico2023; Medina Fetterman et al., Reference Medina Fetterman, Vazquez and Arnold2022; Vogelzang et al., Reference Vogelzang, Foppolo, Guasti, van Rijn and Hendriks2020)Footnote 1 .

In view of such evidence, we report a pilot study in Appendix A, which compares referential choice during production in Dutch and English speakers, the current topic. Of most interest here, in this pilot study, Dutch and English speakers showed comparable personal pronoun production in a context of reference maintenance where two characters have been introduced, which we know can be more vulnerable in bilingual speakers (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016; Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023). We take this as evidence supporting our assumptions of greater similarity of pronoun repertoire and use between Dutch and English than between Spanish and English. We also note that, in previous research on bilingual referential choice, the similarity in the use of referential expressions in the L1 and L2 of bilingual speakers was only assumed but not demonstrated (e.g., Bini, Reference Bini and Liceras1993; Lozano, Reference Lozano2018; Serratrice et al., Reference Serratrice, Sorace, Filiaci and Baldo2009).

We next turn to referential choice in L2 English (non-null subject) in speakers whose first language is Spanish (null subject), the second group under investigation here (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016; Contemori & Ivanova, Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021; Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023). Contemori and Dussias (Reference Contemori and Dussias2016) examined the use of pronouns and noun phrases to maintain coherence in discourse in Spanish L1 speakers who are highly proficient speakers of English (L2). Using two picture-description tasks, Contemori and Dussias found that bilingual speakers produced significantly more underspecified references (pronouns) in English when maintaining reference to a referent that was introduced in the discourse—even with same-gender referents when that led to ambiguity—relative to a group of monolingual English speakers (though a proficiency effect for the L2 group was not detected). Contemori and Ivanova (Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021) found a similar difference between Spanish-English bilinguals and English monolinguals. In addition, a marginally significant effect of proficiency emerged, showing that bilinguals with higher English proficiency produced fewer pronouns than bilinguals with lower English proficiency. In a recent study by Contemori et al. (Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023), a group of bilinguals was tested on the production of referential expressions in English and Spanish, and their performance was compared to a group of monolingual speakers of each language. For English, the results demonstrated that bilingual participants produced more underspecified referential expressions (i.e., pronouns) than monolingual speakers. An analysis of bilinguals’ language dominance further revealed that English-dominant participants produced fewer pronouns than Spanish-dominant participants in contexts of reference maintenance when two referents had been introduced in the context.

Taken together, these studies reveal a similar pattern of underspecification in referential choice in English (L2) of Spanish-English bilinguals. However, the evidence regarding the role of proficiency and language dominance is mixed, demonstrating that, even at the highest levels of proficiency, Spanish-English bilinguals may show a different pattern of production than monolingual English speakers (e.g., Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016). Thus, it is an open question whether Spanish-English bilinguals can use referential expressions in a way comparable to monolingual speakers.

A relevant question is whether such patterns are shown exclusively by Spanish-English bilinguals or are a more general phenomenon occurring for different language combinations. Indeed, previous research has documented the elevated use of pronouns among bilingual speakers across different age groups and language combinations. Studies with bilingual children (e.g., Haznedar, Reference Haznedar2010; Serratrice, Reference Serratrice2007) and bilingual adults (e.g., Otwinowska et al., 2021; Polinsky & Scontras, Reference Polinsky and Scontras2020) consistently report increased production of overt pronouns compared to monolingual use when the language under analysis is a null-subject language (e.g., Italian, Turkish, Polish, etc.) and the other language of bilingual speakers is a non-null-subject language (e.g., English). On the basis of such evidence, we can conclude that elevated pronoun use is a manifestation of the variability associated with bilingual referential use.

We wish to make clear that we completely agree with the current shift of the field away from treating monolingual usage as normative (e.g., Rothman et al., Reference Rothman, Bayram and DeLuca2023). However, we consider the question of similarities of usage patterns of speakers with different language profiles to be of theoretical interest. Indeed, various theoretical approaches account for the optionality observed in bilingual pronoun choice, suggesting that bilingual populations display large variability with these structures (e.g., Interface Hypothesis, Sorace, Reference Sorace2011; Vulnerability Hypothesis, Prada Pérez, Reference Prada Pérez2019). For example, the Interface Hypothesis proposes that bilingual populations are particularly susceptible to variability in resource-demanding structures that involve the interaction between syntax and pragmatics, like choosing and interpreting referring expressions (Sorace, Reference Sorace2011). This account would explain the differences observed between Spanish-English bilinguals and monolinguals but predicts that such differences would be eliminated or attenuated with higher proficiency (consistent with some recent studies). The Vulnerability Hypothesis proposes that bilinguals’ vulnerability with referential expressions in the nondominant language is observed when the distribution of referential expressions is more variable in the target language, leading to cross-linguistic influence effects. For example, Spanish allows both null and overt pronouns depending on the discourse context. According to the Vulnerability Hypothesis, the more variable system in Spanish can pose greater challenges for bilinguals when the dominant language is English (Prada Pérez, Reference Prada Pérez2019). In the present study, we address the role of cross-linguistic influence and language proficiency by testing two groups of bilinguals who are highly proficient in the L2, comparing them to a group of functional English monolinguals.

The present study

In the present study, we compare the performance of bilingual speakers of Dutch (non-null subject) and English (non-null subject) with that of bilingual speakers of Spanish (null subject) and English (non-null subject). The latter are known to produce more pronouns in their L2 English than English monolinguals (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016). Because previous studies have revealed a role of language proficiency and dominance for bilinguals’ referential choice, all bilinguals were tested in their L2 English, and the groups were matched on L2 proficiency level. We also compare the performance of both bilingual groups to that of English monolinguals.

The present study thus aims to answer the following research questions: (i) Is higher variability and a higher rate of pronoun production a feature of the referential behavior of bilinguals who speak specific language pairs, or is it the default usage observed also in languages that are maximally similar in both their referential expressions and use? (ii) Can bilinguals with high L2 proficiency approximate monolingual patterns in L2 referential production preferences?

To this aim, bilinguals described pictures in English after viewing context pictures presenting two characters with either the same or different genders. We measured the number of pronouns produced by bilinguals and monolinguals to refer to the subject antecedent. In previous studies, Spanish-English bilinguals produced more pronouns (i.e., fewer explicit references) than English monolingual speakers (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016; Contemori & Ivanova, Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021; Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023). However, in previous research, bilinguals had lower and/or more variable proficiency in the L2 than the Spanish-English bilinguals tested in the present study. Thus, it may be possible that a selected group of highly proficient bilinguals may not show fundamental differences in referential choice compared to monolingual speakers.

In the experimental task, we included a condition in which the first antecedent is the grammatical subject and the second antecedent is in an object position (more likely to elicit pronouns), similar to previous studies on bilingual referential choice. In addition, we included a condition not tested before, where both antecedents are presented in a coordinate phrase in subject position (less likely to elicit pronouns). Adopting Cunnings’ (Reference Cunnings2017) approach, it is possible that maintaining reference can be a source of indeterminacy because bilingual speakers may be more prone to experiencing interference during memory retrieval. As bilingual speakers build a model of the discourse and keep the information about the referents active in their working memory, the susceptibility to interference may lead to difficulty calculating the accessibility of the referents, resulting in high production of underspecified references. In our study, the condition where two referents are in a coordinated unit involves similar accessibility of the two referents, while in the standardly presented condition, a subject antecedent is more accessible than an object antecedent. The aim is to observe if underspecification is found when two referents have a similar degree of accessibility and activation. Thus, this condition controls for an alternative explanation of bilingual referential choice, namely, that it is driven by decay of referents’ activation due to interference. In such a case, bilinguals should produce more pronouns in the coordinated condition than in the subject–object condition. On the other hand, it is possible that this difference is visible in both antecedent conditions (subject–object and coordinated), if bilinguals experience interference in referent activation in the discourse model (e.g., Cunnings, Reference Cunnings2017).

The question about cross-linguistic influence will be informed by the performance of the Dutch-English group. If it is cross-linguistic influence that ostensibly affects bilinguals’ referential choice, Dutch-English bilinguals in L2 English should perform differently from proficiency-matched Spanish-English bilinguals in L2 English. This would be because Dutch and English are similar in pronoun use when two referents are presented in a context and should give no rise to influence. However, if factors other than cross-language influence (such as difficulty assessing the prominence of antecedents and or cognitive load) underlie the variability and optionality in L2 pronoun use, then Dutch-English bilinguals should be more likely to produce pronouns in contexts where English monolinguals prefer to produce a noun phrase. It is an open question in which contexts the underspecificity may emerge: only in those contexts that are known to be vulnerable for bilinguals, that is, in maintained reference situations where two referents are in subject versus object position (e.g., Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016; Contemori & Ivanova, Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021; Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023), or also when referents are presented in a coordinated structure. On the other hand, it is possible that high proficiency can lead to monolingual-like patterns of referential production. In this case, we expect that bilingual speakers of either language background will perform similarly to monolingual speakers of English. While current theoretical models do not exclude that differences in the type and use of referring expressions across languages may result in a conflict for bilingual speakers (e.g., Prada Pérez, Reference Prada Pérez2019; Sorace, Reference Sorace2011), our results will contribute to shedding light on how cross-linguistic influence interacts with proficiency in referential choice.

Method

Participants

Thirty-one Dutch-English bilinguals (mean age: 22; SD: 6; 25 females, 6 males) were recruited at the University of [removed for review] in the Netherlands and received compensation for their participation (15€). Dutch speakers are exposed to Dutch at birth in the family, and they are exposed to English at an early age through media and classroom instruction. These bilinguals typically attain high proficiency in English even though Dutch is the main language of the community. Thirty Spanish-English bilinguals (mean age: 23; SD: 6; 23 females, 8 males) and 30 English functional monolinguals (mean age: 23; SD: 7; 24 females, 6 males) from the University of [removed for review] in the USA participated for course credit. A priori, the sample size was chosen to be comparable to previous similar studies (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016). A power analysis for an F test with G*Power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009), conducted after the experiment was completed, showed that a design with 3 groups and 4 measurements required 78 participants to detect a smallish effect (f = .15) for a within–between interaction. In the current study, we included 91 participants.

[removed for review] is a community on the US–Mexican border, where both Spanish and English are used. Spanish-English bilinguals are exposed to Spanish from birth in the family, learn English in kindergarten or school, and typically become literate only in English. Monolingual participants were recruited in the community, where Spanish-English bilingual speakers were recruited. While some exposure to Spanish is the norm in this region, the monolingual speakers did not report high proficiency, frequent use, or childhood exposure to Spanish. The data of five additional Dutch-English and four Spanish-English bilinguals were excluded from analyses because of a coding error.

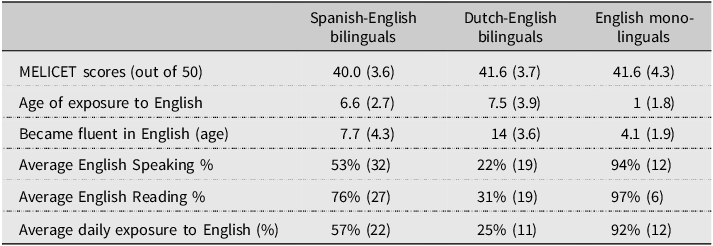

Participants’ language history characteristics are reported in Table 1. All participants completed a language history questionnaire. In addition, participants’ English proficiency was assessed with an objective proficiency measure, the Michigan English Language Institute College English Test (MELICET), which is a 50-question multiple-choice and cloze test with grammar and vocabulary sections. Participants who scored below 35/50 on the MELICET were replaced to ensure that participants were proficient enough in English to complete the referential choice task. A one-way ANOVA showed no significant differences among the proficiency scores of the three groups (F(2,91) = 1.432, p = .1). We conducted additional analyses to compare the demographic information of the two groups of bilingual speakers, using independent-sample t-tests. Spanish-English bilinguals had a significantly lower age of fluency than Dutch-English bilinguals (t(59) = −6.09, p < 0.001). In addition, Spanish-English bilinguals reported significantly higher ratings for English speaking (t(59) = −1.10, p < 0.001), English reading (t(59) = 7.57, p < 0.001), and English exposure (t(59) = 7.01, p < 0.001) than Dutch-English bilinguals. Age of acquisition did not differ significantly between the two groups (t(59) = 7.57, p = .2).

Table 1. Participant information: Mean (SD)

Materials and procedure

The experiment was administered on Zoom by a Spanish-English bilingual experimenter. Participants first saw a context picture and read aloud two context sentences that described it. The context pictures depicted actions performed by two characters (either photographs of humans, as in Figure 1 (Panel A), created by Vogels et al., Reference Vogels, Krahmer and Maes2015, or cartoon characters from Mickey Mouse, adapted from Arnold & Griffin, Reference Arnold and Griffin2007, by Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016). Then, on the following screen, participants saw and orally described a second picture, in which the first-mentioned character engaged in an action, starting the description with “Subsequently….” The pictures were presented with Microsoft PowerPoint. Four practice trials were presented at the beginning of the task to familiarize participants with the experimental procedure.

Figure 1. Example of the picture-description task (materials developed by Vogels et al., Reference Vogels, Krahmer and Maes2015). Panel A: Context picture and sentences. Panel B: Target picture.

There were 32 experimental items. In half of them, one character was presented as the grammatical subject and the other character as the indirect object (example i, Figure 1). In the other half, the sentence describing the first context picture presented the two characters as the grammatical subject in a coordinated phrase (example ii, Figure 1). The two characters had the same gender in half of the items and different genders in the other half, counterbalancing female–male and male–female across items. The condition where one character was the grammatical subject and the other character was the indirect object was used to replicate previous results from earlier studies where underspecification was observed in Spanish-English bilinguals (e.g., Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016) and additionally to test cross-linguistic effects by adding a comparison to Dutch-English bilinguals. Four counterbalanced lists were created with eight items per condition. Thirty-five filler sentences were included with a variable number of characters (one to four). An example of a filler with only one character is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of a filler from the picture-description task (materials developed by Vogels et al., Reference Vogels, Krahmer and Maes2015). Panel A: Context picture and sentence. Panel B: Target picture.

Coding and data analysis

We analyzed references to the first-mentioned antecedent. Analyses excluded descriptions that did not contain either a full noun phrase or a pronoun that referred to the first-mentioned character (i.e., those containing ellipsis, plural pronouns, referents other than the characters presented, coordinated noun phrases, reference to the second character, naming errors, unintelligible productions). Five hundred and eleven productions were discarded (monolinguals: 167/960; Spanish-English bilinguals: 151/960; Dutch-English bilinguals: 193/992).

The data (pronouns, coded as 1, noun phrases, coded as 0) were analyzed with Bayesian models assuming a binomial distribution in the brms R package (Bürkner, Reference Bürkner2017). The models had the default weakly informative priors with center 0 and scale 2.5 (Gelman, Jakulin, Pittau, & Su, Reference Gelman, Jakulin, Pittau and Su2008). We fitted the model with maximal random structure justified by design first and then compared it with less complex models using leave-one-out cross-validation. We report the maximal models because they had the best fit. We report the estimated mean, estimated error, and 95% credible interval (CrI) of the posterior distribution in log odds. The 95% CrI represents a 95% probability that the outcome lies within this interval (Van de Schoot et al., Reference Van de Schoot, Kaplan, Denissen, Asendorpf, Neyer and Van Aken2014). An interval that is either positive or negative (i.e., does not span zero) is considered equivalent to a significant effect in the frequentist approach. The models were fitted using four chains, each with iterations of 5000, of which the first 2000 are warmup to calibrate the sampler, resulting in 12,000 posterior examples.

There were two models. The first compared the two bilingual groups together to the monolingual group, with the sum-coded fixed predictors Language group (bilinguals = −0.25, monolinguals = 0.5), Antecedent grammatical role (subject–object antecedents = −0.5, coordinated antecedents = 0.5), Antecedent gender (different gender = −0.5, same gender = 0.5), and their interactions. The second model compared the two bilingual groups to each other and had the same fixed predictors, except the Language group predictor was replaced with the Bilingual group (Dutch-English bilinguals, coded as −0.5, Spanish-English bilinguals, coded as 0.5).

Trial-level data are publicly available at https://osf.io/erbn5/.

Results

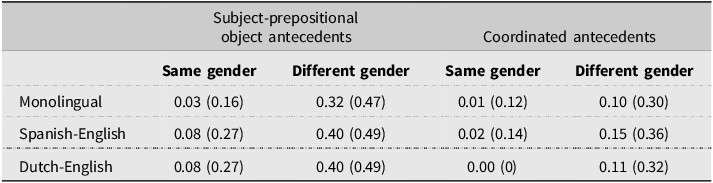

Table 2 shows the proportions of pronouns produced by the three groups of participants in the four conditions, out of the total amount of noun phrases and pronouns included in the scoring. The statistical models are reported in Table 3.

Table 2. By-subject average proportion of pronouns produced by English monolinguals, Dutch-English bilinguals, and Spanish-English bilinguals

Note: Standard deviations are provided in parentheses.

Table 3. Bayesian model results

Note: Shaded rows mark 95% credible intervals (CrI) that do not contain zero (equivalent to significance in frequentist statistics). Model specifications are provided in Appendix B.

aThis model had a simplified fixed-effects structure (the Antecedent grammatical role × Antecedent gender interaction was removed) because the full model was overfitting. This was likely due to the fact that the Dutch-English bilinguals did not produce any pronouns in the same gender, coordinated antecedents condition (i.e., there was one condition with only zeros).

As predicted, both models revealed main effects of Antecedent gender condition, demonstrating that participants produced fewer pronouns when the gender of the antecedents was the same (.04), in comparison to when the gender was different (.26). Also as predicted, an effect of Antecedent grammatical role condition revealed that participants produced fewer pronouns when the antecedents were in a coordinated phrase (.07) than when they were in different grammatical positions (.23).

Most relevant for the current purposes, there was no evidence in either model for an effect of Language group or interactions between Language group and the Antecedent gender or Antecedent grammatical role conditions. We interpret these results as a lack of meaningful differences among the three groups and hence as reasonable that the three populations sampled here are likely to make similar referential choices across the conditions included in our study.

Discussion

This study investigated the role of cross-language influence and high proficiency for referential choice in an L2. To this aim, we compared the rates of pronoun production in a picture-description task of English functional monolinguals to those of two bilingual groups who spoke English as an L2 and whose other language was either similar to or different from English in the use of referential expressions (Dutch and Spanish). We did not find conclusive evidence for differences in pronoun rates either between the monolinguals and the two bilingual groups or between the Dutch-English and the Spanish-English bilinguals. Thus, the results indicate that the two groups of bilinguals are not likely to experience cross-linguistic influence or difficulties assessing the prominence of antecedents. Of note, Spanish-English bilinguals in the present study did not show a higher rate of pronoun production relative to monolinguals, unlike in previous research conducted with the exact same or similar Spanish-English bilingual and English monolingual populations as used here (e.g., Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016; Contemori & Ivanova, Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021; Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023). The results thus suggest that regardless of whether the set of referring expressions and their use is similar or different between two languages, bilingual speakers who are highly proficient in the L2 are likely to use them similarly to English speakers who are functionally monolingual (i.e., use one language on a daily basis and are unable to communicate in another language).

Our results are in principle compatible with the predictions of the Interface Hypothesis (Sorace, Reference Sorace2016). The hypothesis is that the residual indeterminacy in bilingual referential choice might be due to an inconsistency in the recruitment of the cognitive resources necessary to integrate and update contextual information at the syntax-discourse interface (Sorace, Reference Sorace2011). But such inconsistency could well be shown by monolingual speakers too (consider monolingual variation in the Position of Antecedent Strategy in null-subject languages, e.g., Carminati 2002, 2005). Examining the variability in our results (standard deviations in Table 2), we see evidence for more variable performance of the two bilingual groups than the monolingual group in the same gender, subject–object antecedent condition, but similar variability among participant groups in all other conditions. We reason that, at high levels of proficiency, bilinguals have more available cognitive resources and thus may recruit them with greater consistency to guide their referential choices. Importantly, the Interface Hypothesis does not predict differences between bilinguals and monolinguals across the board, and this is why our results are consistent with it.

Our findings are also in principle consistent with the Vulnerability Hypothesis (Prada Pérez, Reference Prada Pérez2019). This hypothesis is that the interpretation and production of referential expressions could be affected to a greater extent by cross-linguistic influence if the use in the target language is highly variable. Within this approach, importance is given to contextual factors such as ambiguity of verbal morphology and verb semantics that make the use of referential expressions less predictable and therefore more challenging to learn—thus more prone to cross-linguistic influence. However, extensive exposure to the L2, such as that of our bilingual groups, could lead to more consistent referential choices, leading to more similar referential patterns among the different bilingual and monolingual groups. We note that the current findings do not allow us to decisively favor either the Interface Hypothesis or the Vulnerability Hypothesis, as aspects of our findings are compatible with both approaches. We also do not see the two hypotheses as mutually exclusive but rather as addressing different aspects of bilingual processing.

So far, we have attributed the similar likelihood of pronoun production among the three groups to the high proficiency of the bilingual groups (comparable to that of the monolingual group). In fact, the bilingual groups also differed in age of fluency in L2 and L2 daily exposure, speaking, and reading. Thus, at face value, it could be that an effect of cross-linguistic influence in the Spanish-English bilinguals (which would have increased pronoun production) was compensated for by their greater experience with the language (reducing pronoun production). In other words, the opposing influences of cross-linguistic influence and exposure could have contributed to Spanish-English bilinguals’ referential choices being comparable to those of the Dutch-English bilinguals, who had fewer years of experience with English but no comparable effects of cross-linguistic influence. We cannot completely discard such an explanation (Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023). However, a strong influence of age of acquisition and exposure in the current dataset is undermined by the fact that our monolingual group also differed from the Spanish-English bilingual group in age of fluency in English and English daily exposure. If these factors were strong drivers of the referential patterns observed here, we would expect the monolinguals to actually differ from both bilingual groups, but this is not what we found. In any case, we highlight the need for our field to continue to investigate the specific influences of proficiency, age of acquisition, and daily exposure and use on bilingual referential choice. We also note that the present findings should be interpreted with caution, given the differences between the bilingual groups in age of acquisition and exposure.

We further note that our monolingual group was recruited in a community on the US–Mexico border, where both Spanish and English are used. Recent research has reported that passive exposure in multilingual communities can change monolingual speakers’ brain responses when learning words in a new language (e.g., Bice & Kroll, Reference Bice and Kroll2019). That being the case, to our knowledge, naturalistic exposure to other languages is not known to affect the acquisition of discourse at the behavioral level. In fact, referential choice is generally considered a late-acquired ability in language development (for child learners, Serratrice & Allen, Reference Serratrice and Allen2015). We also note that here we failed to find differences between groups sampled from the exact same (Contemori & Ivanova, Reference Contemori and Ivanova2021; Contemori et al., Reference Contemori, Tsuboi and Armendariz2023) or similar populations (Contemori & Dussias, Reference Contemori and Dussias2016) to studies that detected such differences. More broadly, “pure” monolinguals are something of an oddity (Castro et al., Reference Castro, Wodniecka and Timmer2022); we therefore see merit in working with populations that are more representative of the linguistic variability experienced by speakers worldwide.

To reconcile the results of the present study on Spanish-English bilinguals and the results of previous research showing some underspecification in referential choice, we speculate that cross-linguistic influence may contribute to the learning trajectory of referential expressions and is more likely when the set of referring expressions and production biases are different across the two languages (e.g., Spanish and English). Bilingual speakers can in principle demonstrate underspecification (e.g., production of pronouns when it leads to ambiguity) as part of increased variability in their referential choices, but the choices become more consistent with high proficiency.

Our results have further implications for understanding how speakers make referential choices. First, we replicated previous production results showing a gender effect (more explicit references with same-gender than with different-gender antecedents), due to the potential ambiguity that can arise from using a pronoun when the two antecedents share the same gender (Arnold & Griffin, Reference Arnold and Griffin2007). Furthermore, we found an effect of antecedent position: Participants produced significantly more explicit references when they referred to a first-mentioned antecedent in a coordinate phrase in subject position than a single first-mentioned antecedent in subject position. This result is an effect of the decreased prominence of the antecedent that shares subjecthood with the second-mentioned antecedent in a coordinated phrase (or alternatively, an increased accessibility of the second-mentioned antecedent). This suggests that the first-mention/subject bias observed in English may not be purely related to the grammatical function and position of the antecedent but also to the difference in prominence between this antecedent and competing referents. Such an effect of relative prominence was also found by Long et al. (Reference Long, Rohde, Oraa Ali and Rubio-Fernandez2024), who manipulated prominence at the discourse level rather than the sentence level. They found that adding a second sentence with a pronoun referring to the subject, which reincreased the relative prominence of the subject referent compared to competitor referents, increased the number of pronouns used in the next sentence. Both findings are in line with the idea that linguistic prominence results from a competition among referents for limited attentional resources (Arnold & Griffin, Reference Arnold and Griffin2007).

To conclude, we compared pronoun production in a group of English monolinguals and two groups of L2 speakers of English, namely, Spanish-English and Dutch-English bilinguals. The present study is the first to rule out residual optionality in the referential choice of highly proficient L2 English speakers with different language backgrounds, demonstrating comparable use of referential expressions as monolingual English speakers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716425100398.

Replication package

Trial-level data are publicly available at https://osf.io/erbn5/.