Introduction

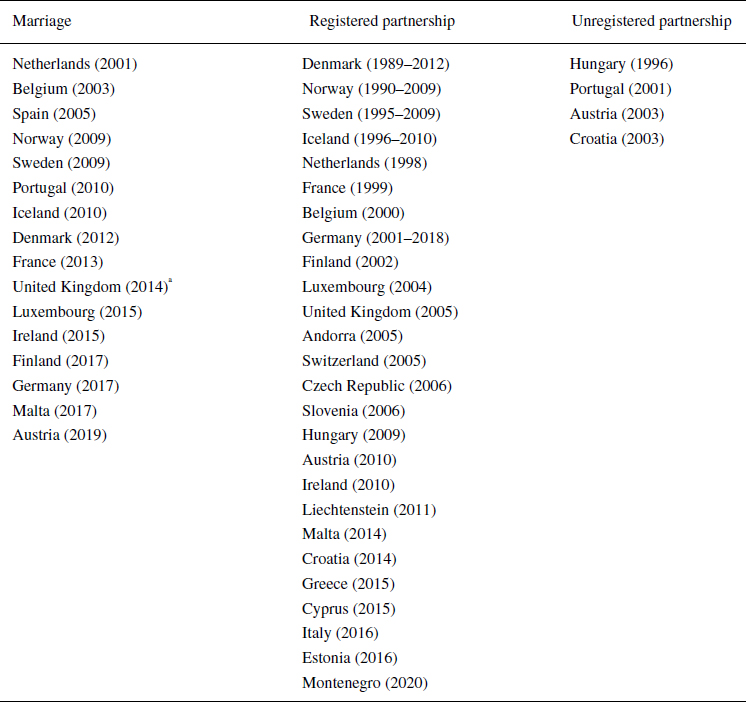

Since the 1990s, Europe has gained and promoted a reputation for being on the vanguard of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI)Footnote 1 rights expansion. This reputation, for the most part, is well deserved. Today no European state has a legal prohibition against same‐sex sexual acts, and most offer legal protections against sexual orientation discrimination, in part because the former is prohibited by the region's human rights body, the Council of Europe, and the latter protections are guaranteed by European Union (EU) law (see Table 1). Although European institutions have yet to mandate that their member states open marriage to same‐sex couples, over half the countries in the world that recognise same‐sex marriage are in Europe (Ayoub & Paternotte Reference Ayoub, Paternotte, Bosia, McEvoy and Rahman2020).Footnote 2

Table 1. Anti‐discrimination (sexual orientation) protections in Europe since 1980Footnote a

Sources: Søland (Reference Søland1998); Waaldijk (Reference Waaldijk2000; Reference Waaldijk, Wintemute and Andenaes2001); Mendos (Reference Mendos2019).

Table 1. Years in brackets represent the dates that anti‐discrimination measures were adopted. Generally, protections increased with each new legal measure.

This trend towards the recognition of LGBTI rights by European states, however, is relatively recent and masks diversity both in how these states historically have regulated same‐sex sexuality and how they have expanded the rights of LGBTI‐identified people since the 1980s. In the high‐profile area of relationship recognition rights, for example, just over half of the 44 countries in the wider European region recognise same‐sex couples in law, and only 16 allow these couples to marry (Mendos Reference Mendos2019).

Many seminal studies of LGBTI politics highlight the role that modernisation has played in fostering the expansion of rights in early adopting countries (D'Emilio Reference D'Emilio, Abelove, Halperin and Aina Barale1993; Adam et al. Reference Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel1999; Frank et al. Reference Frank, Camp and Boutcher2010). Indeed, the idea that rich countries with high levels of economic development are more likely to have liberal LGBTI policies than less developed countries is often treated as a truism in the contemporary literature. Despite broad acceptance, the relationship between rights expansion and socio‐economic development is often not fully specified in the literature or even a central focus of empirical analysis in many recent studies. Much of the contemporary literature incorporates measures of economic development or wealth into the analysis as a control variable or as one of many factors posited to expand such rights (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Camp and Boutcher2010; Asal et al. Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013; Fernandez & Lutter Reference Fernández and Lutter2013). Few studies have examined how other processes associated with socio‐economic development influence the liberalisation of LGBTI rights. This association of modernisation with narrow measures of economic development has persisted in the work of LGBTI rights scholars even though in recent years all sorts of states, including ones relatively underdeveloped in terms of wealth, have become leaders on LGBTI rights expansion.

In this paper, we draw on classic works of both modernisation theory and LGBTI history to better explicate how modernisation leads to policy change and to highlight an aspect of modernisation that has been less explored in the contemporary LGBTI rights literature, namely urbanisation. Urbanisation has long been associated with the rise of interest group politics as well as gay and lesbian activism (Weber Reference Weber and Runciman1978; D'Emilio Reference D'Emilio, Abelove, Halperin and Aina Barale1993). As many historians of LGBTI movements highlight, cities played – and continue to play – a crucial role in the creation of gay and lesbian movements in Western countries by providing spaces for sexual communities and identities to form (Haeberle Reference Haeberle1996).

In addition, but perhaps less recognised in contemporary politics literatures, sociological research has found that cities enhance the effectiveness of civil society organisations by increasing their visibility, placing them in proximity to political elites, fostering tolerance across diverse groups living in densely populated areas and, as more recent work has highlighted, by facilitating access to the resources of transnational activist networks through their connections to global cities (Lerner Reference Lerner1958; Sassen Reference Sassen2004). Put more simply, urbanisation facilitates the formation and effectiveness of associational life. Indeed, early modernisation scholars often emphasised the political consequences of the rise of urban centres over the political consequences of wealth accumulation (Anthony Reference Anthony2014).

The divergent patterns and effects of urbanisation on contemporary political developments in Europe – the focus of this paper – are particularly interesting. In the decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the transition to capitalist democracies in the 1990s, Eastern Europe was one of the few global regions in which rates of urbanisation slowed and, in several countries, declined (Tosics Reference Tosics, Hamilton, Dimitrowska‐Andrews and Pichler‐Milanovic2005). In contrast to Western Europe, which plays host to a growing number of global cities, the region has seen its major urban centres stagnate over the past two decades (Restrepo Cadavid et al. Reference Restrepo Cadavid, Cineas, Quintero and Zhukova2017).

We use the insights of these literatures to argue that the nature of European states’ urban systems has shaped how these societies engage with LGBTI rights claims. Specifically, we posit that higher levels of urbanisation both hasten the formation of national sexuality movements and enhance the effectiveness of LGBTI rights activism. If the first of these urban influences has long been recognised by LGBTI movement – although not policy – scholars, the second has been almost wholly overlooked in this literature. We thus seek to open the black box of modernisation theory to better pinpoint the precise and multiple mechanisms by which socio‐economic development fosters LGBTI rights expansion. We see urbanisation as a complementary mechanism to wealth accumulation that has an independent – and potentially as strong or even stronger – effect on policy change.

We test the propositions outlined above by examining the extent to which levels of urbanisation explain the speed with which European states have adopted anti‐discrimination and same‐sex union (SSU) laws – two prominent but distinct rights issues – since 1980. To test our hypotheses, we use event history analysis (1980–2015) and an original dataset that contains measures for institutional, cultural, economic and movement variables, as well as measures of our key independent variable (IV), levels of urbanisation, in 44 states of the broader European region, including the member states of the European Union. To our knowledge, this is the first dataset of this scope: combining the multitude of these indicators in the wider region of Europe, a region that has been central to the expansion of LGBTI rights. Our findings support the contention that urbanisation facilitates both the creation of LGBTI movements as well as has a significant effect on the propensity of and speed with which European states expand LGBTI rights. The relationship between urbanisation and rights expansion persists even after controlling for a country's level of wealth, religious adherence and the influence of European institutions and norms.

The uneven expansion of LGBTI rights in Europe

Historically, European states have regulated same‐sex sexuality in different ways. Tudor England adopted, enforced and eventually spread ‘anti‐buggery’ laws to the rest of the United Kingdom, and later to its far‐flung colonies, from as early as the 16th century (Asal et al. Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013; Han & O'Mahoney Reference Han and O'Mahoney2014). The revolutionary government in France left a different legacy by de‐criminalising sexual activity between men in 1791 and diffusing this legal inheritance to southern Europe via the Napoleonic Code (Waaldijk Reference Waaldijk2000; Kollman Reference Kollman2013). Most other countries in Europe outlawed homosexuality until the 20th century and reformed such laws at different rates after 1950 (Mendos Reference Mendos2019). In 1981, the European Court of Human Rights for the first time mandated that a member state decriminalise homosexuality in its Dudgeon v UK ruling and helped accelerate decriminalisation in the rest of Western, as well as Eastern, Europe after 1990.

European states, however, did not begin to offer their LGBTI citizens positive legal protections or recognition until the 1980s (see Table 1). Relatively narrow anti‐discrimination laws were adopted in the Nordic countries and in France during this decade. A handful of other West European countries such as Finland, the Netherlands and Spain followed their example in the 1990s (Waaldijk Reference Waaldijk1994). With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the re‐writing of legal codes in Eastern Europe, several states in the region including the Czech Republic, Poland, Estonia and Romania incorporated sexual orientation into more far‐reaching anti‐discrimination legislation from the late 1990s (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016). The European Union consolidated the legal gains made by LGBTI movements in 2003 by mandating that its member states ban sexual orientation discrimination in employment law. In many countries, particularly in Western Europe, the EU legislation led to wider reforms that made such discrimination illegal in the provision of goods and services, welfare benefits and/or inheritance law (Mendos Reference Mendos2019).

Over the past two decades, European countries in both the East and West have continued to expand anti‐discrimination protections to an increasing number of domains and by including protections for gender identity and transgender individuals. At the beginning of 2019, only three European countries had no anti‐discrimination laws for sexual orientation or gender identity of any kind at the national level: Belarus, Russia and Turkey (Mendos Reference Mendos2019). Although there has been a clear trend towards greater legal protections, there remains considerable diversity in this legislation with certain countries adopting more comprehensive anti‐discrimination legislation earlier than their peers.

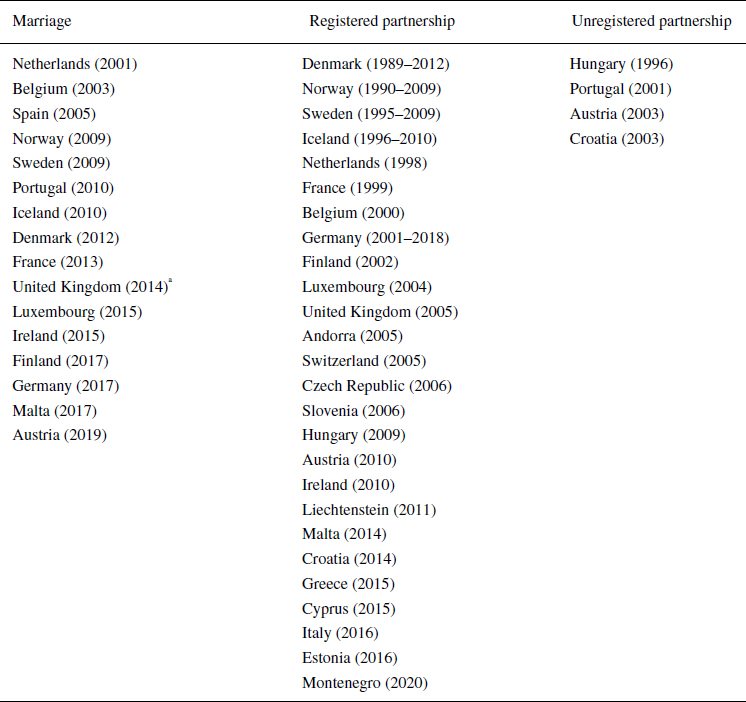

In contrast to the role that European institutions have played in promoting anti‐discrimination standards, neither the EU nor the European Court of Human Rights mandated that a member state must recognise the relationships of same‐sex couples until 2015 and there continue to be no mandates to open marriage to same‐sex couples and transgender individuals at the European level.Footnote 3 No state recognised same‐sex couples in law until Denmark implemented the world's first SSU policy in the form of a registered partnership (RP) in 1989. This RP law granted same‐sex couples many of the welfare and tax benefits associated with civil marriage, but withheld rights such as the ability jointly to adopt children as well as the right to call their relationship a marriage (Søland Reference Søland1998). Several West European countries, including Sweden, Norway, France, Iceland and the Netherlands, adopted such RP laws with varying levels of rights and duties throughout the 1990s. It took until 2001, however, for a government to open marriage to same‐sex couples when the Netherlands became the first country to do so (Kollman Reference Kollman2017). Since 2001, 15 additional West European countries including Spain, Portugal and Malta in Southern Europe have extended marriage rights to same‐sex couples.Footnote 4 Despite this trend, several countries in the region have adopted or retained RP laws: Switzerland, Greece and Italy (Mendos Reference Mendos2019). The latter implemented an RP law in 2016 after the European Court of Human Rights for the first time condemned a member state for failing to legally recognise same‐sex couples in the 2015 Oliari and others v Italy ruling (see Table 2).

Table 2. National SSU legislation in Europe since 1980

Sources: Mendos (Reference Mendos2019); Savage (Reference Savage2020). Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-montenegro-lgbt-lawmaking-trfn/montenegro-legalises-same-sex-civil-partnerships-idUSKBN24271A.

Table 2. Northern Ireland first allowed same‐sex couples to marry in 2019.

The spread of SSU policies in Central and Eastern Europe began later than in Western Europe and remains more uneven. Hungary adopted a limited domestic partnership law as early as 1996. But it was not until 2006 that the Czech Republic became the first country in the region to implement a more comprehensive RP law. Since then four other East European countries have adopted similar RP laws: Slovenia (2006), Hungary (2009), Croatia (2014) and Estonia (2016). Four of the region's EU member states still have no form of recognition for same‐sex couples: Lithuania, Latvia, Poland and Slovakia (Mendos Reference Mendos2019). In addition, apart from Estonia no former member of the Soviet Union has implemented an SSU (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016). In contrast to Western Europe, no East European country has opened marriage to same‐sex couples. Indeed, the issue of marriage equality has become particularly contentious in the region. Thirteen East European states have adopted constitutional amendments that define marriage as being between one man and one women, thus prohibiting the opening of the institution to same‐sex couples (Mendos Reference Mendos2019). As such, LGBTI rights and marriage equality in particular have become part of the ongoing tensions between Eastern and Western Europe as well as a flash point between more liberal and nationalist visions of Europe's future (Slootmaeckers et al. Reference Slootmaeckers, Touquet and Vermeersch2016).

Modernisation, urbanisation and LGBTI rights expansion

Why has Europe seen the rapid but uneven expansion of LGBTI rights since 1980? A well‐established body of scholarship has shown that processes of Europeanisation and the growing strength of global LGBTI movements have helped to propel rights expansion onto the agendas of European states (Fernández & Lutter Reference Fernández and Lutter2013; Kollman Reference Kollman2013; Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016). As outlined above, however, governments in the region have not implemented these legal mandates or soft law norms for greater rights at the same speed or in the same manner.

Scholars have often linked variable LGBTI rights outcomes to individual countries’ levels of modernisation (Adam et al. Reference Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel1999; Badgett et al. Reference Badgett, Waaldijk and Van der Meulen Rodgers2019; Hildebrandt et al. Reference Hildebrandt, Trüdinger and Wyss2019). Defined as an inter‐related set of processes by which societies develop, modernisation encompasses a broad range of structural, economic and cultural changes that include urbanisation, industrialisation, wealth accumulation and mass education (Wucherpfennig & Deutsch Reference Wucherpfennig and Deutsch2009). Together these socio‐economic processes have long been associated with political transformation, democratisation (Lipset Reference Lipset1959) and social policy innovation (Wilensky & Lebeaux Reference Wilensky and Lebeaux1958). These arguments about political change are premised on the idea that industrial, and now post‐industrial, societies have greater needs for bureaucratic state intervention, a class structure that supports liberal and social democracy as well as the resources necessary to carry out political and policy innovation (Lipset Reference Lipset1959; Skocpol et al. Reference Skocpol, Abend‐Wein, Howard and Goodrich Lehmann1993).

Some scholars have argued that modernisation leads to political transformation via the mechanism of cultural change. Greater economic and educational resources are posited to promote certain values such as tolerance, freedom of expression and participatory norms that create a demand for democracy (Almond & Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963; Inglehart & Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Welzel Reference Welzel2013). In their wide‐ranging work on the linkages between development, value change and democratisation, Inglehart and Welzel (Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005) conceptualise modernisation as an ongoing process and distinguish between the effects of industrialisation and post‐industrialism on mass values. While industrialisation affected Western societies through secularisation and a move away from traditional religious values, Inglehart famously has associated post‐industrialisation with post‐materialist values and a focus on individual autonomy, personal choice and self‐expression (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990; Inglehart & Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005).

Scholars of LGBTI politics have drawn on these logics to argue that richer and more developed states will be more likely to liberalise LGBTI rights than their less developed counterparts (Adam et al. Reference Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel1999; Corrales Reference Corrales2017; Badgett et al. Reference Badgett, Waaldijk and Van der Meulen Rodgers2019). Variants of this argument draw on the work of scholars like Inglehart and Welzel to illustrate that wealth leads to rights recognition by increasing levels of tolerance towards homosexuality (Hildebrandt et al. Reference Hildebrandt, Trüdinger and Wyss2019). Indeed, many first mover states on LGBTI rights were relatively wealthy. Much of the recent literature on LGBTI rights expansion, however, has largely taken this relationship for granted and not dissected the precise mechanisms by which socio‐economic development brings about policy change. Due to their focus on other important variables, many studies have treated economic development as a control variable or as one of several factors that lead to rights expansion (Frank et al. Reference Frank, Camp and Boutcher2010; Asal et al. Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013).

As a result, more recent literature has tended inadvertently to reduce modernisation to economic development in empirical analysis. Many studies utilise either national levels of wealth or slightly broader measures of economic development such as the human development index as proxies for these complex processes of socio‐economic change (Velasco Reference Velasco2018; Sommer & Asal Reference Sommer and Asal2014; Fernandez & Lutter Reference Fernández and Lutter2013). This emphasis on economic development, either with or without the linkage to value change, has persisted even though several recent studies suggest the effects of wealth on LGBTI rights adoption are weaker once you look at more contemporary waves of rights adoption or examine rights expansion below the global level within different world regions (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2015; Díez Reference Díez2015; Velasco Reference Velasco2018).

Urbanisation and LGBTI politics

Very little contemporary literature on LGBTI rights highlights the multi‐dimensional nature of modernisation or examines mechanisms of policy change that are not directly linked to economic factors. Perhaps most conspicuously neglected within this literature is the role that urbanisation has played in facilitating the expansion of LGBTI rights. Despite its recent neglect, urbanisation featured prominently in both early modernisation theory as well as in the historical accounts of lesbian and gay activism in Western societies.Footnote 5 Historians, starting (at least) with Foucault (Reference Foucault1978), have argued that the creation of modern homosexual identities is tied to the rise of industrial capitalism and the concomitant development of urban centres. This dramatic transformation of socio‐economic structures led to two important changes that made gay and lesbian identities possible. First, an increasing number of people became embedded in waged labour, which decoupled the family from economic production. Second, and crucially, industrial production meant a move to urban centres for these waged labourers, which further disrupted traditional kinship ties and community‐based familial relations. These changes allowed for more personal autonomy and greater choice over sexual partners and spouses (D'Emilio Reference D'Emilio, Abelove, Halperin and Aina Barale1993; Adam et al. Reference Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel1999).

It was in these new urban settings that many historians argue ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’ communities and identities – as opposed to same‐sex sexual acts – first took hold and became visible in Europe and North America (D'Emilio Reference D'Emilio, Abelove, Halperin and Aina Barale1993; Adam et al. Reference Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel1999). For example, when charting the personal biography of an early gay rights activist, the German Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, historian Robert Beachy recounts:

Ulrichs had a special motive, however, for coming to Berlin … Clearly this sexual awakening [experienced on a study‐stay in Berlin] jolted the young Ulrichs, but it also underscored the loneliness he felt in Göttingen. As far as he could see, there was no one else there like himself (Beachy Reference Beachy2014: 9).

Most biographical explanations surrounding the politicisation of the first gay rights activists, and the many that followed, rest on their move to the city, where encounters with like people ‘jolted’ them into political action. Having a degree of distance from family structures and discovering others that share their desires and proclivities helped to establish a language for LGBTI identities and rights among Ulrichs and his successors. Furthermore, unlike many other marginalised groups, LGBTI people have to seek each other out to learn of their history and to politicise the personal. Their history is rarely socialised and passed down within the family unit.

Chauncey (Reference Chauncey1994) makes a similar observation for the role of New York and other US coastal cities in the Post‐WWII period, where queer sailors from rural states developed new identities while on tour. It is no coincidence that many of the key waves of LGBTI movement history had their critical junctures in urban centres: the pre‐WWI influence of Berlin (Beachy Reference Beachy2014), followed by the Homophile Movement's reliance on activism in Amsterdam (Rupp Reference Rupp2011), and then the activists in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles and San Francisco with the birth of Gay Liberation (Weeks Reference Weeks, Paternotte and Tremblay2015). Urban centres continue to provide spaces for LGBTI movement organisations to emerge from relevant sub‐cultures and to create common political agendas.

Less noted in the literature is the role that cities have played in enhancing the political effectiveness of LGBTI activism. Although now only rarely highlighted by politics scholars, the classic sociological works on modernisation emphasised the link between urbanisation and the creation of interest group politics and participant societies (Weber Reference Weber and Runciman1978; Lerner Reference Lerner1958). The population density of urban centres helps to enhance the visibility of organised interest groups to a greater proportion of the population. Cities also increase movements’ proximity to political and social elites who influence political outcomes. Such visibility is important for all social movements, but it has been seen as particularly vital for LGBTI activism, whose members historically have lived less open lives because their relationships lack social legitimacy (Wald et al. Reference Wald, Button and Rienzo1996; Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016). More broadly, modernisation scholars have argued that urbanisation helps to create the political mechanisms and norms necessary to resolve conflicts created by increasingly interdependent and differentiated groups of people living in close quarters. In other words, urbanisation historically has been linked to the creation and effectiveness of interest group politics in modern societies in ways that wealth and economic development alone cannot explain (Anthony Reference Anthony2014; Glaeser & Steinberg Reference Glaeser and Steinberg2017).

Although urbanisation in Europe is often associated with the processes of industrialisation that occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries, urban centres in the region have continued to grow and evolve in differentiated ways in recent decades. The global cities literature highlights the continued relevance of urbanisation for explaining political outcomes in the 21st century. This literature illustrates the role that large, often wealthy cities have played in processes of economic and political globalisation. While much of the early literature focused on how global cities have facilitated cross‐border economic integration, more recent research has highlighted how such cities foster global civil society through inter‐urban networks (Sassen Reference Sassen2004; Brenner & Keil Reference Brenner and Keil2014). These urban centres, many of which saw significant population growth after 1980, have the necessary mix of ‘creative’ people, communications technology and connections to other global metropolises to build transnational activist networks (Florida Reference Florida2005). Global cities thus have become the venues through which the not insignificant resources of global LGBTI movements flow and have influence. National activists located within these urban centres are more likely to have access to these resources and to be able to apply them to national political campaigns and discourses. Although scholars have highlighted the role that transnational activist networks have played in the successful expansion of LGBTI rights in European countries, they have largely failed to incorporate the insights of the global cities literature into their analysis (Altman Reference Altman2002; Kollman & Waites Reference Kollman and Waites2009; Ayoub Reference Ayoub2013).

Recent urbanisation trends in Europe have been both significant and uneven (UN Department of Economic & Social Affairs 2018). While urbanisation rates since the 1980s have continued to increase across the European region as whole, levels of urbanisation in many East European countries stagnated after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and have only recently begun to rise again. Certain countries in the region even experienced a decline in urban population in the decades following the transition from single‐party communist rule (Tosics Reference Tosics, Hamilton, Dimitrowska‐Andrews and Pichler‐Milanovic2005). This trend has resulted in greater levels of urbanisation in Western than in Eastern Europe and a divergence in the development of cities in the two regions just as the global LGBTI movement was growing in strength at the beginning of the 1990s (UN Department of Economic & Social Affairs 2018).

Based on these trends and literature, we hypothesise that national levels of urbanisation will affect the speed with which European countries adopt laws that expand the rights of LGBTI people. Specifically, we argue that both the percentage of people living in cities as well as the movement of people in European countries from rural to urban centres will facilitate rights adoption by strengthening national LGBTI movements, increasing their visibility to the public and elites, facilitating tolerance across diverse groups living in densely populated areas and by increasing the access national activists have to the resources of global LGBTI movements.Footnote 6

Hypothesis 1: Countries with higher levels of urbanisation will hasten the adoption of national SSU and anti‐discrimination laws.

Hypothesis 2: Countries with higher levels of urbanisation will hasten the formation of strong national LGBTI movements that advocate for (and have been shown to facilitate) the adoption of SSU laws and anti‐discrimination laws.

Alternative hypotheses

Although we posit that urbanisation has a strong effect on LGBTI movements and rights expansion, the literature has charted a number of important alternative explanations that we seek to control for in our models. As outlined above, much of the contemporary LGBTI politics literature has highlighted the role that wealth plays in fostering tolerance of homosexuality and rights expansion. We include it in our models alongside urbanisation.

In addition to wealth, scholars have highlighted the role that a country's religious traditions play in the adoption of LGBTI rights (Adam et al. Reference Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel1999). Most contemporary LGBTI movements in European societies (and beyond) have had to contend with religiously based counter‐movements that seek to define intimate relationships and marriage in traditional and heterosexual terms. Orthodox and Catholic Churches in Europe have mobilised extensively against SSU policies (Ramet Reference Ramet, Katzenstein and Byrnes2006). As such, we take the number of Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox or Muslim religious adherents in a country into consideration in our models.

The success of LGBTI activism in democracies is also likely to be affected by the nature of the political institutions in these countries. Within European democracies, particular parties have been seen to be more favourably disposed to the rights claims of LGBTI movements than others. In particular, social democratic and other centre‐left parties in Europe traditionally have been more supportive of gender and LGBTI rights than the parties of the centre‐right such as the Christian Democratic parties that seek to uphold more traditionalist values (Engeli et al. Reference Engeli, Green‐Pedersen and Larsen2012; Badgett Reference Badgett2009). While findings on this indicator are mixed (Siegel & Wang Reference Siegel and Wang2018; Budde et al. Reference Budde, Heichel, Hurka and Knill2018), we assume that countries where centre‐left parties have been in government more often will be more likely to expand LGBTI rights.

Some literature suggests that the legacy of a communist past may hinder the adoption of post‐material values like LGBTI rights. These explanations are rooted in the idea that post‐communist states inherited sticky path‐dependent institutions, and that Soviet influence bankrupted their civil societies (Jowitt Reference Jowitt1992). While many have rightly challenged the determinism of the legacy argument, because we do observe variation on LGBTI rights within this group of states – the aforementioned general differences between Western and Eastern Europe on this issue (Asal et al. Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2013) – we test this association.

Finally, numerous scholars have argued that the recent adoption of LGBTI rights by European countries has been spurred by processes of international harmonisation and socialisation (Fernández & Lutter Reference Fernández and Lutter2013; Paternotte & Kollman Reference Paternotte and Kollman2013). Most variants of this argument look at the influence of ties to global society and regional institutions such as memberships in international and non‐governmental organisations, cross‐border communication and levels of international travel (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher, Gaston and Martens2008). We thus control for both length of membership in the EU, which as outlined above, should directly affect anti‐discrimination legislation as well as for the number of SSU policies that have been adopted in Europe and globally in each year. The latter we posit will affect the normative pressure states feel to adopt relationship recognition policies.

Data and methods

We test the impact of urbanisation by analysing an original dataset on the introduction of SSU and anti‐discrimination policies in the 44 states of the broader European region.Footnote 7 Examining data from 1980 to 2015, our dataset tracks the passage of LGBTI rights policies (the dependent variable, DV), with other state‐level institutional, cultural, economic and social movement variables. We collected data for the IV by utilising organisational membership lists and a variety of existing datasets related to state‐level conditions across Europe.

The dataset begins in 1980, the earliest year for which we have data for all our variables. It was in this decade that the Danish parliament introduced the first partnership bill (1984) and adopted their path‐breaking Registered Partnership law in 1989 (Søland Reference Søland1998). It was also in the 1980s that France first adopted anti‐discrimination protections in 1985 (Mendos Reference Mendos2019). The dataset ends in 2015, the year the European Court of Human Rights made its Oliari v Italy ruling and began to create harder mandates for same‐sex relationship recognition, although not for the opening of marriage.

Dependent variable

Different forms of LGBTI rights policies have spread rapidly across the globe over the past three decades. To track this legislative momentum, the dataset includes two key measures of LGBTI rights: SSU partnership in general (including RP, civil unions and marriage policies) and anti‐discrimination policies. We have chosen these two policy areas because they represent the most prominent LGBTI rights issues on the agendas of European states in the time period examined. Their use also increases the robustness of our results by examining urbanisation's effects on two types of equality issues. Marriage equality and relationship recognition represent a status issue, while anti‐discrimination legislation is a class‐based or economic issue (Annesley et al. Reference Annesley, Engeli and Gains2015).Footnote 8

Our variable SSU partnership measures the introduction of a partnership policy – broadly conceived – by any state: for example, Denmark scores ‘1’ beginning in 1989. We have also run the analysis with a DV that captures only ‘marriage’ equality – for example, the Netherlands scores ‘1’ beginning in 2001. Marriage equality is arguably the most salient right demanded by LGBTI movements in the last two decades. The ‘SSU partnership’ and ‘marriage’ variables are highly related and produce similar results. For the purposes of this paper, we mainly report the findings around SSU partnerships generally, the most holistic indicator of LGBTI partnership rights. We do however report models with ‘marriage’ as the DV in Table 3 and Table A3 (in the Online Appendix).

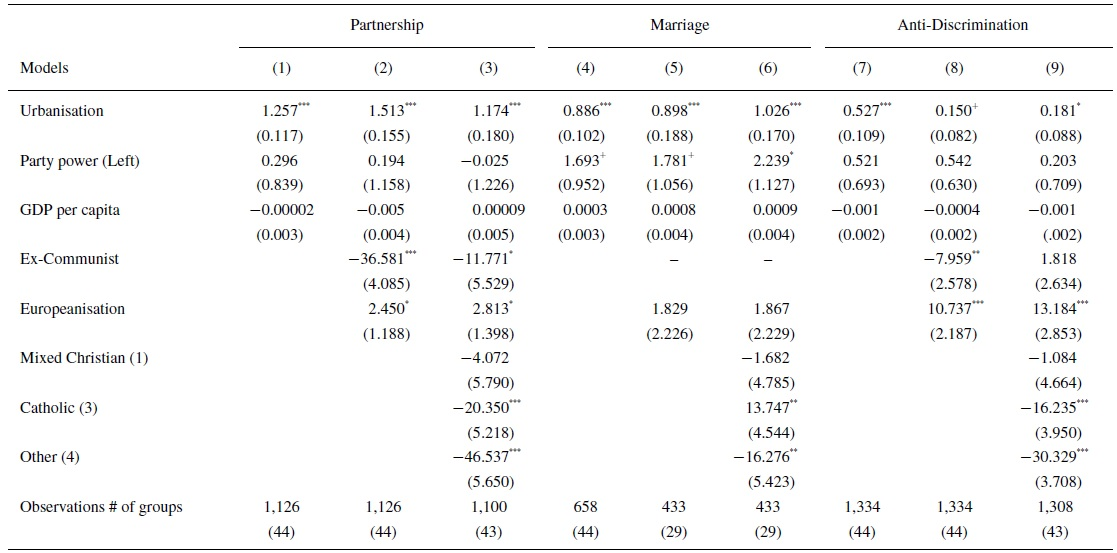

Table 3. Logit regression estimates predicting adoption of LGBTI rights policies in Europe, 1980–2015

Note: Controls for year dummies not shown; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1.

The binary measure of anti‐discrimination policy is measured in the same way, capturing any single law that protects persons on the grounds of sexual orientation and/or gender identity. The variable signifies the passage of any one piece of LGBTI anti‐discrimination legislation in the areas of employment, housing, public accommodation or education. Our DV provides a measure with which to understand LGBTI recognition across time and place. Furthermore, it can shed light on the conditions for legal success and cultural change. The DV is measured as a binary ‘0’ or ‘1’ dummy variable: ‘0’ indicating that no (SSU, marriage or anti‐discrimination) policy had passed in the country/state in any given year, and ‘1’ indicating that a policy is in place within the country/state beginning with the year of passage onward.

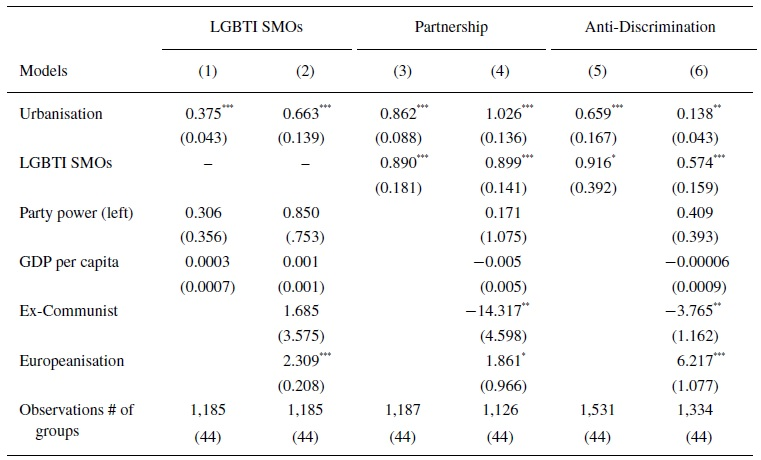

An additional DV captures the role of urbanisation in influencing the formation of the social movement organisations (SMOs) that advocate for LGBTI rights. In order to track the number of LGBTI SMOs across European countries, we utilised the membership lists from the archives of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA). The lists track what year the organisation joined ILGA. While this source is among the most detailed in systematically capturing social movement activity cross‐nationally, it is important to note that operationalising LGBTI SMOs is notoriously difficult and our measure remains imperfect. Measures deriving from ILGA archives privilege organisations that choose to be listed, which requires a certain level of organisation, political orientation, visibility and awareness of/connection to the international LGBTI movement. Smaller and more loosely organised local organisations are less likely to be captured. With this important caveat in mind, we measure the number of LGBTI SMOs – also embedded in ILGA – in each country over the 35‐year period analysed.Footnote 9 Beyond looking at SMOs as an outcome of urbanisation, we also test their independent effect on SSU and anti‐discrimination rights in Table 4.

Table 4. Logit regression estimates predicting LGBTI movements and policy in Europe, 1980–2015

Note: Controls for year dummies not shown; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.1.

Independent variables

Our core IV tests the proposition that as domestic populations become more urban, states will become more likely to adopt an LGBTI rights policy. Our measure for urbanisation comes from the World Bank and captures the percentage of the country's population living in urban areas (see Table A2 in the Online Appendix). We find this measure of urbanisation particularly useful theoretically, as it captures a key notion in theorising by scholars that highlights access to urban areas as expedient for establishing LGBTI identities, movement organisations and the ability of these movements to promote the rights that come with them. It also taps into differences across countries and within countries across time.Footnote 10

Additional variables capture the state‐level conditions across European countries. In order to track the relative resonance within each domestic realm, we include variables on levels of state wealth, political alignment and religious context. State wealth associated with more post‐material values – another facilitator of tolerance of LGBTI people – is captured by the per capita GDP of the country. Political alignment is measured with a governance variable that captures the party colour of government on a left to right spectrum (either right, centre or left). Next, we include a measure of dominant state religion. Dominant religion is coded as (1) Mixed Christian, (2) Protestant (reference group), (3) Catholic and (4) Other (Orthodox and/or Muslim) states. These religions qualify as dominant if at least 70 per cent of all adherents identified as a member (Andersen & Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008; Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Kurian and Johnson2001).

Finally, we include two measures of Europeanisation, one for our anti‐discrimination models and one for our SSU models. These measures capture the idea that European countries are influenced by the norms and legal standards promoted by European institutions and other countries in the region. Since scholars have noted the EU's soft‐law socialising effect for the introduction of SSUs globally (Kollman Reference Kollman2013), we have a measure that tracks the prevalence of (as a count) SSUs in Europe and globally.Footnote 11 For anti‐discrimination, we follow scholars that note the effect of the EU's norm promotion by including sexual orientation as part of their anti‐discrimination directive. We thus include a dummy variable for EU accession that tracks the year when a state joins the EU (or not) (cf. Table A2 for a detailed description of how Europeanisation is measure in each model). We also include unreported dummy variables for each year in the analysis to control for time trends.Footnote 12 Tables A1 and A2 of the Online Appendix offer descriptive statistics and describe our coding decisions in further detail.

Method

In Tables 3 and 4, we analyse the dataset with a discrete time event analysis using logistic random‐intercept models. This type of model aids a researcher in exploring change within states that occur at discrete points in time (Box‐Steffensmeier & Jones Reference Box‐Steffensmeier and Jones1997; Lektzian & Souva Reference Lektzian and Souva2001). Event history models are useful for analysing a question of differential adoption of policies across time and states and have been used, for example, to examine related questions concerning the decriminalisation of sodomy laws and the introduction of hate crime legislation in the United States (Kane Reference Kane2003; Soule & Earl Reference Soule and Earl2001). In our case, the units of analysis are European countries, time measured in years and the passage of SSUs or marriage or anti‐discrimination policies specifically. In Table A3 of the Online Appendix, we further test the relationship between urbanisation and policy introduction using a Cox regression technique for time‐to‐event analysis. This estimation allows us to calculate a hazard rate or the likelihood that an event occurs at a particular time. When a state introduces such a policy – for example, an SSU – it drops out of the hazard set because it is no longer at risk for introducing SSU legislation.

Results

In this section, we explore the relationship between urbanisation and policy change and report the results of the logistic discrete time event history analysis described above. In this analysis, we report the coefficients linked to the likelihood of an SSU, marriage or anti‐discrimination policy being adopted by European countries. In Table 3, models 1–3 report the trimmed and full results for SSU (partnership policies generally), models 4–6 report the results for marriage equality policies specifically and models 7–9 report the results for anti‐discrimination policies in Europe. As theorised and demonstrated in Table 3 (and Table A3 in the Online Appendix), urbanisation has a significant and positive affect on the introduction of both partnership and anti‐discrimination legislation in European countries.Footnote 13 The coefficient estimates are the logged odds of adopting SSU, marriage and anti‐discrimination policies.

Our findings thus provide strong support for our main theoretical proposition. With a one‐unit increase in urbanisation, states are on average 1.257 (3.51 times in model 1) to 1.174 (3.23 times in model 3) more likely adopt an SSU policy. This spans from the trimmed model 1, holding party power and GDP per capita constant, to the full model 3, holding constant ex‐communist legacy, Europeanisation and religion (with Protestant as the reference group). Models 4–6 show a similar positive relationship between urbanisation and marriage equality, where states are 0.886 (2.42 times more likely), 0.898 (2.45 times more likely), and 1.026 (2.79 times more likely) to adopt an LGBTI marriage policy, respectively. In the anti‐discrimination models 7–9, we find that states are 0.527 (1.69 more likely), 0.150 (1.16 times more likely) and 0.181 (1.20 times more likely) to adopt anti‐discrimination policies, respectively, holding other variables constant. Given that urbanisation is measured on a 1–100 scale (ranging from 33 to 98 in Europe), this is a substantial effect on policy outcomes, and one that is also more consistent than most other variables. The fact that urbanisation has a slightly stronger impact on SSUs is logical given the lack of European mandates in that policy area and the strong effect that the Europeanisation variable has in the anti‐discrimination models. In sum, although the size of the impact varies to some degree across our models, urbanisation has a consistently positive and significant relationship with LGBTI rights policy adoption in Europe.

The control variables largely act as predicted. Europeanisation, both the demonstration effect of early LGBTI‐rights adopting states in the region in the SSU models and EU membership in the anti‐discrimination models, has a positive and significant effect on policy adoption. In line with previous literature, international examples influence states to adopt SSUs (models 2 and 3). That said, models 5 and 6 on marriage do not reach significance on Europeanisation. This could be in part because the demonstration effect of Europeanisation can often lead to a civil union compromise – for example, Ireland's popular vote on marriage leading to Greece and Italy ushering in civil unions shortly afterwards. This outcome is not captured in the DV used in models 5 and 6 (while it is captured in models 2 and 3). The fact that Europeanisation in the form of EU accession has a strong effect on anti‐discrimination policy is also not surprising (models 8 and 9), given that the EU's Amsterdam Treaty of 1999 included a clause calling for EU member states to ban discrimination in employment on the basis of sexual orientation; this clause was translated into binding legislation in 2003. Both effects have been shown in earlier studies (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016).

Our variable ‘ex‐communist state’ has a negative and significant relationship with the introduction of partnership rights (models 2 and 3) but mixed results as it relates to anti‐discrimination policy in models 8 and 9. It is omitted in models 5 and 6 because no ex‐communist states have a marriage policy, meaning it predicts failure perfectly. These findings suggest that ex‐communist states are less likely to adopt partnership rights policies. This is not surprising given the high moral salience of partnership rights in the region, as opposed to the less salient anti‐discrimination policies, which were readily worked into the legal codes in many ex‐communist states ahead of their accession applications to the EU.

Left parties are positively correlated to the introduction of marriage equality rights in models 4–6, but these results should be interpreted cautiously given that twice they are only significant at the p < 0.1 level. Finally, when compared to the baseline category of Protestant states, Orthodox and Muslim majority states (category ‘other’) have a negative and significant effect on all indicators of LGBTI rights adoption, thus impeding the adoption of such policies. On average, Catholic majority states also have a negative and significant effect on SSU and anti‐discrimination adoption (as compared to Protestant states). Yet, they have a positive relationship with marriage equality (compared to Protestant states), which may be picking up the early movement of the three pioneer states on full marriage in Europe, the Netherlands (mixed‐Christian, yet with Catholic influence as its largest group), Belgium (Catholic) and Spain (Catholic). The other indicators, notably wealth and left parties in government, fail to reach significance in their relationship to the introduction of LGBTI policies, with the exception of the left parties variable (discussed above) in the marriage models.

Social movement organisations

Table 4 uses the same statistical technique to incorporate our theorising around LGBTI SMOs.Footnote 14 As predicted by our theory of how urbanisation affects rights expansion, models 1 and 2 in Table 4 show that urbanisation hastens the formation of internationally networked LGBTI SMOs in any given state (measured as a 0,1 dummy variable in these first two models).Footnote 15 Next, as shown in much of the literature, and by models 3–6, LGBTI SMOs also hasten the adoption of LGBTI rights independently, alongside urbanisation. For example, one additional LGBTI movement organisation in the country is predicted to increase the likelihood of the adoption of SSU laws by 0.89 (2.4 times more likely) and the introduction of anti‐discrimination laws by 0.57 (1.8 times more likely), holding all other variables constant. The finding is consistent with the hypothesis, which suggests more organised, visible and intense activism on LGBTI rights tends to facilitate the adoption of SSU laws and anti‐discrimination policies. While not the focus of this study, the finding provides support for both the idea that movements can help to usher in policy, as well as the existing finding that umbrella groups aid in the process by diffusing international norms governing LGBTI rights through the transnational networks they provide (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2013; Kollman Reference Kollman2013; Velasco Reference Velasco2018). The positive and significant relationship between urbanisation and LGBTI policy holds, as does the effect of Europeanisation. Communist legacy again has a negative and significant relationship with rights introduction, though produces null results in relation to having formal LGBTI organisations (model 2). This is not surprising, given the proliferation of LGBTI SMOs in Central and Eastern Europe – beginning with Slovene groups in the mid‐1980s – as well as the focus of transnational INGOs like ILGA and funders like the Open Society Foundations on such states during this period. Overall, this analysis shows that urbanisation facilitates both LGBTI movement formation and rights expansion.

Discussion and conclusions

Although it is widely accepted that modernity and economic development are important factors in the success of LGBTI activism, scholars have paid surprisingly little attention to the precise mechanisms by which modernisation facilitates rights expansion. Few studies seek to untangle the effects that the different processes associated with modernisation have on policy change. Of particular note is the relative neglect of urbanisation in the recent work on LGBTI rights expansion. Reducing modernisation to wealth and economic development, as many contemporary empirical studies have done, ignores the emphasis that early modernisation and LGBTI scholars placed on the connections between urban centres and political change.

In this paper, we have sought to add to the literature on modernisation and LGBTI politics by putting the spotlight back on urbanisation and examining how this process has influenced rights expansion in Europe, a continent that has seen the rapid but also uneven implementation of laws that recognise the rights of LGBTI people. Our findings support the contention that urbanisation facilitates both the formation of LGBTI movements and the implementation of policies that expand LGBTI rights. The strong effect remains even after controlling for key alternative factors including levels of GDP per capita, which did not have a significant effect on the adoption of LGBTI rights policies in our analysis. In regions such as Europe where levels of economic development do not vary as starkly as they do globally, national wealth may well not be as important as urbanisation when we consider how modernisation affects policy outcomes and the liberalisation of LGBTI rights. The results highlight the important role that socio‐political conditions such as urbanisation play in building movements for reform and translating such activism into policy change. In keeping with our argument about the importance of movements, our findings also support what much of the literature has posited about the role that strong national LGBTI movement organisations play in spurring policy change.

Given the many posited linkages that exist in the literature between a country's urban systems, LGBTI activism and political change, these outcomes should not surprise us. Cities create the social spaces necessary for LGBTI identities to form as well as the proximity needed to facilitate political mobilisation (Haeberle Reference Haeberle1996; Adam et al. Reference Adam, Duyvendak and Krouwel1999). These urban centres also promote the effectiveness of LGBTI activism by increasing the movement's visibility to wider groups of people, fostering tolerance of diverse lifestyles and placing activists near to social and political elites (Anthony Reference Anthony2014). Finally, the presence of large, globally connected cities within a country can help link national LGBTI activists to the growing resources generated by transnational LGBTI movements and supportive international organisations (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016; Velasco Reference Velasco2018; Sassen Reference Sassen2004). For these reasons, the steady and continued growth of urban centres in Western Europe during the 1990s and 2000s helped to facilitate the increasingly visible rights claims of LGBTI activists. In Central and Eastern Europe, by contrast, the difficult transition to capitalism from planned economies resulted in a stagnation of urban centres just as LGBTI movements gained strength and began to establish a global profile. These differential patterns of urbanisation appear to have hindered the effectiveness of LGBTI movements as well as the resonance of their calls for policy change in certain East European countries.

These results point to several potentially fruitful future lines of enquiry. First, more research is needed on the effects that national levels of urbanisation have on the propensity of countries to expand LGBTI rights. Our findings indicate that urbanisation has strongly influenced LGBTI rights adoption in Europe. More research should examine the effect of national urban systems in other parts of the world where absolute levels of urbanisation tend to be lower but rates of change more rapid. Such research can help flesh out the relative importance that different modernisation processes – most obviously urbanisation and wealth accumulation – play in fostering rights expansion outside of Europe where levels of wealth vary more dramatically.

Future research could also help to better establish the precise mechanisms by which the concentration and movement of people into urban areas facilitates LGBTI rights expansion. As highlighted throughout this paper, the linkages between movements, policy change and cities are manifold and complex. Cities have often been posited to facilitate the political mobilisation of LGBTI communities and activism within the literature. But as outlined by classic modernisation scholars, cities can also increase the effectiveness of LGBTI activism through greater visibility and proximity to sympathetic populations as well as help these movements to gain access to the potent resources of transnational LGBTI rights movements. Which of these mechanisms matter most, in which time periods and combinations and under what circumstances is not entirely clear. More qualitative or mixed methods research may be necessary to uncover the different ways in which urbanisation leads to greater LGBTI rights expansion.

The paper's findings also have implications beyond the study of LGBTI politics. These findings remind us that urbanisation is central to ongoing processes of modernisation and is perhaps as important for understanding contemporary political change as economic development. Rates of urbanisation are higher than they ever have been in the Global South. How these processes affect politics, political change and the prospects for political liberalisation have received much less attention by politics scholars than the effects of economic development. Similarly, in Western countries, changing patterns of urban development have received scant attention by political researchers even though differences in rural and urban worldviews appear to be linked to growing political polarisation. In light of these developments, politics scholars may need to take urbanisation as seriously as early modernisation theorists to gain a better understanding of how movement to and concentrations of people in large metropolitan areas shape contemporary civil society and political engagement.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for the insightful feedback and support received from Lauren Bauman, Chris Claassen, Ana Langer, Anja Neundorf, Douglas Page, Sergi Pardos‐Prado, Karen Siegel, Karen Wright and Jade Wu. We would also like to thank the participants at the 2019 European Conference on Politics and Gender Biannual Meeting in Amsterdam, the Netherlands as well as the September 2019 meeting of the Comparative Politics Research Cluster at Glasgow University.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

Table A1a. Descriptive Statistics

Table A1b. Correlations

Table A2. Variables Summarised

Table A3. Cox Regression Estimates for Predicting Adoption of Gay Rights Policies in Europe, 1980–2015