Introduction

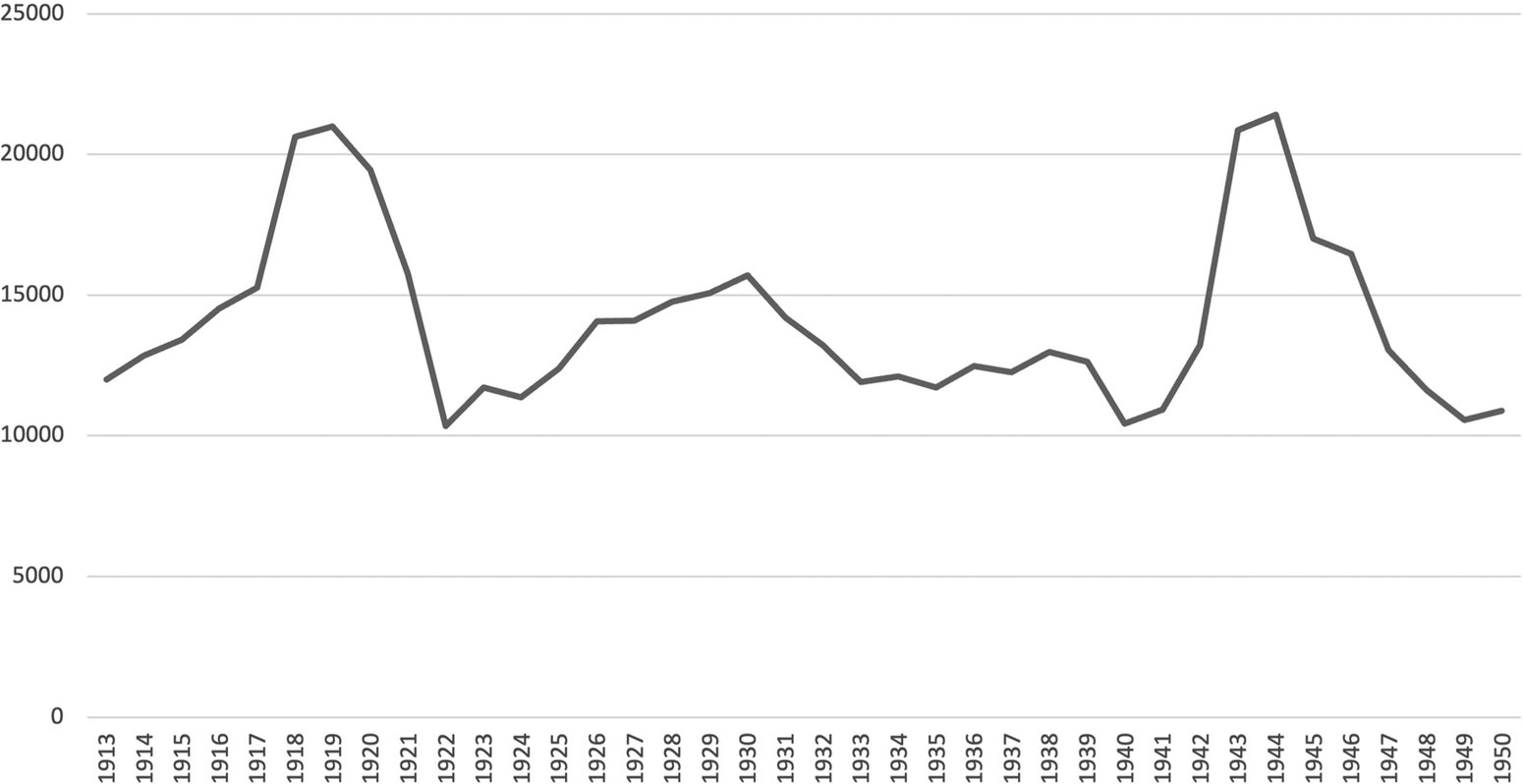

Recent historical research on the business and commercial aspects of condoms has significantly expanded our understanding of how people accessed and learned about protection against pregnancy and venereal disease.Footnote 1 Several scholars have highlighted the increase in condom manufacturing and consumption during World War II as a key moment in the mass consumption of contraceptives. Yet the specific ways in which the war reshaped the market for condoms remain underexplored.Footnote 2 For example, Claire L. Jones notes that birth control use in Britain rose from about 9 percent in 1930 to 18 percent in 1949.Footnote 3 While Jones briefly links this increase to anti-venereal disease campaigns during the war, her analysis primarily attributes the growth to a long-term increase in demand for fertility control, overlooking the specific impact that the war might have had on the market.Footnote 4 In Sweden, despite the country’s neutrality during the war, similar patterns of increased condom consumption can be observed. Condom imports rose from 4.75 million in 1938 to 14.4 million by 1950,Footnote 5 while venereal disease rates spiked from 12,991 cases in 1938 to 21,417 by 1944.Footnote 6 This raises important questions about how wartime conditions, particularly the rise in venereal diseases—syphilis and gonorrhea—and the relationship between state-led public health initiatives and commercial marketing influenced the condom market in both belligerent and non-belligerent countries.

While various “protective products”—such as chemical spermicides (tablets, gels, powders, and liquids), douches, and diaphragms—were available in Sweden during the early twentieth century, the condom came to dominate the market from World War II onwards. As I will argue in this article, this shift was largely driven by rising venereal disease rates and changes in public health policy. Accordingly, the article examines not only a key moment in the growth of the condom market but also how the war years marked a shift in the consumption of protective products, narrowing a diverse range of options into one centered on condom use.

Although World War II has been widely studied, the commercial landscape during the war, particularly in non-belligerent countries like Sweden, remains, with a few exceptions, largely underexamined. While wartime conditions led to rationing and frugal consumption, the advertising industry worked hard to maintain influence, using strategic messaging to shape public behavior even in times of crisis.Footnote 7 In Sweden, businesses used advertising not only to encourage appropriate consumption but also to cultivate “responsible” consumers as part of the home front.Footnote 8 Economic historian Klara Arnberg and colleagues have, for example, shown that advertisements in the Swedish press encouraged consumption as part of the defense of the home front, framing consumer behavior as a form of civil resistance.Footnote 9 Similarly, historian David Clampin has shown that British advertising contributed to the mobilization of the home front and that the commercial message was focused on mediating a longing for peace and normality as well as maintaining brand awareness.Footnote 10 Historian Tawnya Adkins Covert and other scholars have also highlighted the role of advertising in boosting wartime morale.Footnote 11 Taken together, these research contributions suggest that, regardless of wartime involvement, businesses across nations engaged in consumer engineering, shaping consumer attitudes and behaviors through advertising during World War II. In Sweden, this expanded into the marketing of condoms as this article will show.

Historically, wartime has been associated with increased infection rates of venereal diseases, prompting governments to launch large-scale public health campaigns promoting protective practices. Historian Allan M. Brandt highlights that US public health campaigns during World War II significantly shifted societal perceptions of condoms to a more permissive attitude.Footnote 12 Several belligerent countries, such as France, Germany, Spain, and the United States, chose to distribute free condoms to their armed forces in order to decrease the spread of venereal diseases.Footnote 13 Yet since the late nineteenth century, venereal diseases have symbolized a morally corrupt society, a stigma that has extended to the very existence of prophylactic products, which have often been viewed as encouraging promiscuity and immoral behavior.Footnote 14 It was therefore not without reluctance that these policies were introduced. Historian Andrea Tone describes this as a pragmatic response to the high costs of treating venereal diseases, acknowledging that attempts to enforce abstinence were unrealistic given soldiers’ sexual behaviors. The mentality “men will be men” preceded attempts to encourage soldiers to abstain.Footnote 15 In the postwar period, however, official positions became more restrictive, with the aim of restoring prewar moral norms. Women returned from their war work to the home, and the more liberal attitudes toward condom use were pushed back to prewar notions.Footnote 16

In condom marketing, the commercial viability of advertising specific aspects of sexuality has varied across different countries, reflecting broader cultural attitudes toward contraception, prophylactics, and sexual behaviors.Footnote 17 In the United States, a court ruling in 1930 made it legal to advertise condoms as prophylactics but prohibited their promotion as a method of fertility control.Footnote 18 In contrast, Britain allowed the promotion of condoms, diaphragms, and spermicides as a means of preventing pregnancy.Footnote 19 However, advertising condoms as protection against venereal diseases was not accepted in the United Kingdom until the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.Footnote 20 This invites an examination of how especially condoms were marketed in Sweden, particularly during wartime, when shifts in sexual behavior and rising public health concerns, such as venereal diseases, influenced consumer demand and marketing strategies.

Although Sweden remained neutral during World War II, the government introduced a range of policies during the “years of preparedness” [beredskapsåren] 1939–1945 that significantly reshaped both the economy and society, with marked effects on consumer markets and behavior.Footnote 21 Information, propaganda, and advertising became important parts of preparedness in Sweden. New authorities were set up to develop information campaigns and advertising in order to lead consumers to frugal consumption during the crisis years, and to educate about the special conditions brought by the war.Footnote 22 Scholars of media history have examined the long-term consequences of this expansion in public information efforts, arguing that postwar Nordic welfare states adopted an increasingly interventionist approach aimed at shaping citizen behavior through information as a form of social governance.Footnote 23 This article expands on that research by shifting the focus to the war years, adding to the research on how public propaganda during this period laid the groundwork for later developments in state–citizen communication and behavioral regulation.

Between 1939 and 1945, Sweden underwent an extensive militarization, with more than one million men conscripted into military service. This military mobilization led to a significant portion of the population relocating to new areas and starting new sexual relationships.Footnote 24 Unlike the situation in warring countries, condoms were not distributed for free to military personnel in Sweden. However, researchers have noted that the government spread public health campaigns promoting protective practices.Footnote 25 This is further supported by Elisabet Björklund’s thesis on sex education films, where she suggests that a parallel war was being fought on the home front—a “war against venereal diseases.”Footnote 26 By depicting sickness as a threat to both the body and the nation, citizens were urged to fight illness as a part of the preparedness on the home front.Footnote 27

Building on Nancy Tomes’s argument that businesses have tended to position their advertising as an educational force alongside state-led health campaigns, this article explores the relationship between government authorities and condom retailers. Tomes highlights that the boundaries between official public health messages and commercial advertising were often blurred.Footnote 28 As this article will show, similar dynamics played out in Sweden during World War II, where public health campaigns against venereal diseases and commercial marketing for condoms were deeply interconnected. To analyze this relationship, this article employs the concepts of social engineering and consumer engineering. Social engineering refers to state-led efforts to shape citizens’ behavior through often technocratic and scientifically grounded planning and policy.Footnote 29 In contrast, consumer engineering focuses on how businesses use strategic messaging to influence consumer preferences.Footnote 30 Several scholars have noted that wartime public health campaigns influenced attitudes toward condom use but that postwar societies reverted to prewar moral standards.Footnote 31 To address this, I examine how wartime conditions shaped the Swedish case as well as the postwar attitudes toward condoms.

In this article, I demonstrate how wartime conditions, including infection rates and state-led public health campaigns, had a significant impact on condom marketing practices in Sweden. These factors led to a market selection in which condoms emerged as the primary “protective product,” surpassing alternatives such as chemical spermicides and diaphragms. I further argue that unlike in the United States and the United Kingdom, Swedish authorities did not revert to prewar moral standards; instead, they continued to promote infection control in the immediate postwar years. By examining marketing practices during and immediately after the war, this study highlights how wartime conditions catalyzed shifts in both public health messaging and commercial marketing, leaving a lasting impact on Sweden’s condom market.

Sources and Methodology

In this article, I examine public health campaigns and commercial advertisements for condoms in newspapers and brochures. These advertisements are valuable sources for investigating cultural, rhetorical, and ideological dimensions used to construct attitudes toward prophylactics and contraceptive use.Footnote 32 In total, I have studied sixty-four brochures from four dominant Swedish condom retailers, as well as newspaper advertisements, mostly in daily press but also in military press, from 1939 to 1950. The time frame captures both the immediate effects of wartime policies and the transitional period into postwar conditions, providing a lens to assess how marketing strategies evolved in relation to shifting public health concerns and societal norms. The majority of these brochures were aimed at consumers and distributed through advertisements and mail, while a smaller share of them were addressed to retailers. The brochures, often ranging from ten to forty pages, offer unique insight into how companies articulated their strategies in response to wartime conditions, providing a platform to engage with consumers privately in their homes, which was especially important given the controversial character of condoms.

Many, but far from all, of the official health campaigns have been saved in the archives of the Swedish Board of Medicine [Medicinalstyrelsen]. In these archives, I have been able to identify posters, pamphlets, brochures, flyers, and articles for daily and weekly papers, as well as manuscripts for radio lectures and films shown in cinemas. However, the daily press sources contained several advertisements and articles that refer to campaigns that were distributed throughout the country, but which I have not been able to find in any archives. To acknowledge and fill in these archival gaps, I have used the national digitized newspaper archive to search for relevant articles and advertisements to supplement the gaps. Additionally, legal texts, government reports, and documents from the Swedish Board of Medicine are analyzed to examine how Swedish authorities framed and managed issues related to contraception and prophylactics. These sources are essential for understanding condom marketing practices, especially as authorities became more strategically involved in the commercial sphere due to the war. Finally, both textual and visual sources are analyzed with a content analysis to identify recurring themes, such as appeals to hygiene or national defense, as well as rhetorical strategies that framed condom use as both a personal and civic responsibility. This analysis allows for a nuanced understanding of how companies and authorities employed, adapted, or resisted wartime discourses on health protection.

The empirical section of the article is organized into four parts. The first provides a historical overview of the marketing of contraceptives and prophylactics in Sweden, contextualizing how legal and societal constraints shaped advertising from 1910 to 1938. The second section analyzes state-led propaganda campaigns against venereal diseases during World War II, while the third focuses on how condom retailers adapted their marketing strategies to wartime conditions. The fourth and final section explores how these developments influenced postwar advertising practices, demonstrating the war’s long-term impact on condom marketing practices. Together, these sections trace how World War II contributed to lasting changes in the marketing and consumption of condoms, offering broader insights into the development of Swedish consumer culture in general.

The Early Marketing of Condoms in Sweden 1910–1938

In the early 1900s, condoms, diaphragms, and chemical spermicides were primarily viewed as a means to limit the number of children, posing a significant challenge to the conservative government as fertility rates were declining rapidly. The use of contraceptives also had the potential to remove the consequences of sex, which conservatives and Christians saw as a threat to the institution of marriage.Footnote 33 To address these issues, several countries, including Sweden, introduced restrictive regulations controlling the sales and advertising of contraceptives. These restrictions changed over time, but were in place in Sweden between 1910 and 1970.Footnote 34

Prior to World War II, advertising condoms was illegal but not uncommon. Between 1910 and 1938, Sweden’s Contraceptive Law [Preventivlagen]—an addition to the obscenity clause in the penal code—prohibited the public display and advertisement of contraceptives, their outdoor sale, and the dissemination of related information. Based on the political debate and motives behind the law, several historians have concluded that it failed to achieve its intended purpose of limiting public access to information on condoms.Footnote 35 Paradoxically, sales and advertising became more widespread after the law was introduced, especially with the emergence of new retailers—so-called health care shops [sjukvårdsaffärer]—established in the 1910s and 1920s that specialized in selling condoms, diaphragms, and chemical spermicides.Footnote 36 In 1933, the National Association for Sexual Education [Riksförbundet för sexuell upplysning] (RFSU) was founded, alongside its affiliated company Sexual Hygiene [Sexualhygien u.p.a.], which sold contraceptives. While RFSU played a key role in promoting sex education, its commercial operations remained relatively modest until the 1950s. These profit-driven companies offered a wide range of goods, but their main revenue came from selling contraceptives and prophylactics. In addition to retail, health care shops also acted as the primary importers and advertisers of condoms.Footnote 37 By the early 1940s, roughly 4,000 legal contraceptive vendors were operating in Sweden.Footnote 38 As I have shown in previous research, the physical market was concentrated in larger urban areas; however, the popularity of mail-order sales extended consumer access well beyond city centers.Footnote 39

Although condom advertisements appeared in the Swedish press as early as the 1890s, their prevalence increased sharply only after the introduction of the advertising ban in 1910. Advertisements were published daily in many of the major newspapers as well as in weekly magazines and union press publications, and could even be found in the Police Authority’s union paper.Footnote 40 To avoid prosecution, newspaper advertisements were often discreet, relying on euphemisms such as “rubber” and never specifying the product’s intended use—a strategy also observed in the United States and the United Kingdom.Footnote 41 Internationally, businesses appear to have developed similar tactics to circumvent legal restrictions on contraceptive advertising in the press. Commercial brochures were, on the other hand, more explicit, often providing detailed instructions for the use of diaphragms, both in writing and through illustrations. It was also common for brochures to include lengthy comments on social issues such as poverty, gender issues, foreign affairs, and national politics.Footnote 42 Perhaps most importantly, these brochures served as a crucial source of information about reproduction and birth control at a time when such knowledge was scarce or difficult to access through official channels. Readers were encouraged to take control of their sexuality, to enjoy sex, and were even cautioned that sexual abstinence actually could pose health risks. Whereas opponents condemned condoms as morally corrosive, businesses framed them as emancipatory commodities.Footnote 43

During World War I, the government reported that venereal diseases had reached epidemic levels, increasing the demand for public knowledge about personal hygiene and prophylactics.Footnote 44 In 1919, Sweden’s first universal infection control legislation, Lex Veneris, was enforced, transforming a previously private medical matter into a public health concern. The law required individuals diagnosed with venereal diseases, such as gonorrhea or syphilis, to receive free treatment in exchange for disclosing the identity of the person who had transmitted the disease.Footnote 45 As spreading information about condoms was officially illegal, authorities and physicians could not publicly provide guidance on condoms as a means of disease prevention without risking fines or imprisonment.Footnote 46 Both physicians and patients appear to have been reluctant to discuss private sexual matters during medical consultations, though some likely did.Footnote 47 Consequently, information on condoms, diaphragms, and chemical spermicides was primarily spread by political activists and commercial vendors willing to risk legal sanctions. Nevertheless, the government and medical authorities began to recognize the need to inform the public more freely about prophylactics and disease prevention.

Since Sweden lacked domestic production of condoms during World War I, the retail trade was dependent on a steady flow of imports. This was particularly important as, before latex was introduced into manufacturing in the 1930s, condoms were perishable goods and could only be stored for up to three months after the date of manufacture, compared to latex condoms, which could be stored for up to five years.Footnote 48 Trade blockades, combined with the short shelf life of condoms, created an international shortage during World War I.Footnote 49 It was therefore only during World War II that the material conditions allowed for the purchase of larger stocks, ensuring a more reliable supply of condoms over time. In terms of marketing, this meant that health care shops promoted other types of products during World War I to maintain brand awareness and sales, but were able to advertise condoms and take advantage of their prophylactic qualities during World War II.

By 1938, the Contraceptive Law was revoked and replaced in 1939 by the Ordinance on Trade in Contraceptives [Förordning om handel med preventivmedel], establishing new institutional frameworks for companies selling and advertising condoms. Disseminating information about condoms was legalized, thus lifting the ban on advertising. The ordinance aimed to regulate the commercial aspects of the market for condoms, diaphragms, and chemical spermicides in greater detail, granting authorities control over how these products were marketed and sold. Sellers and advertisers were required to obtain a permit and to submit examples of their planned advertisements for approval. Advertisements were assessed based on the new law, which stipulated that they should not be intrusive or distributed in inappropriate contexts. Products were likewise not permitted to be displayed or demonstrated improperly. Finally, advertisements were prohibited if they were deemed harmful to public morality.Footnote 50

When World War II erupted in September that same year, both businesses and authorities were still adjusting to the new legislation. The guidelines for evaluating advertisements were vague and loosely defined. As long as an advertisement was not deemed offensive to public morality, most forms of expression were permitted.

Public Propaganda Against Venereal Diseases During World War II

During World War II, infection rates of venereal diseases increased significantly (see Appendix, Figure A1). As mentioned, authorities’ and physicians’ attitudes toward condoms had begun to shift during World War I. With the legalization of information on contraceptives and prophylactics in 1939, authorities could for the first time in twenty-eight years publicly promote condoms as protection against venereal diseases. Consequently, when the war erupted, authorities were able to swiftly initiate proactive efforts to prevent the spread of infection, marking the beginning of Sweden’s first public propaganda against venereal diseases.

Figure 1. Poster “Remember that every casual sexual encounter involves the risk of venereal disease,” 1944.

Source: TNA, Medicinalstyrelsens’ archive, Hälsovårdsbyrån, Extra föredraganden i könssjukvården, 1944–1947, vol. E 24:3, “Tänk på,” Stockholm City Health Board, 1944.

The infrastructure for managing venereal diseases during the war years was based on two pillars: information and treatment. Extensive information campaigns were conducted to educate the public about the spread and prevention of venereal diseases, as well as the availability of treatment. Posters were prominently displayed in public urinals, restaurant bathrooms, and on street poles, educational films were shown in cinemas, and the Board of Medicine disseminated information on prophylactics through various media outlets such as radio, daily newspapers, weekly magazines, and trade press.Footnote 51 This deliberate use of targeted information reflects how authorities, especially the Board of Medicine, aimed to reshape societal attitudes toward sexual behavior and public health during a period of crisis. To ensure efficient treatment, the Board of Medicine established new health care clinics throughout the country. Treatment for venereal diseases was provided free of charge but was also compulsory. Individuals who refused treatment risked being sentenced to forced labor, a point frequently emphasized in public health campaigns.Footnote 52 Among women, however, only those who were fertile qualified for free care, suggesting that the policy aimed to secure healthy babies rather than to promote the health of women or citizens more broadly. Despite the government’s efforts, there was a significant increase in the number of infections during the first half of the 1940s (see Appendix, Figure A1). The rise in venereal diseases has been attributed, in part, to the mobilization efforts during the preparedness period, which led to large population movements and the formation of new sexual relationships.Footnote 53 As Lundberg has shown, the majority of individuals registered as infected between 1919 and 1945 were young, conscripted men.Footnote 54 However, this overrepresentation of men in the statistics may reflect a bias in the population being tested, as the military conducted thorough examinations of conscripted men. Nonetheless, rising infection rates put pressure on authorities to disseminate information about prophylactics and protective practices.

To whom, then, were these public health campaigns directed? And how did they influence the marketing of condoms? The campaigns explicitly targeted men––particularly conscripted men, as well as those who consumed alcohol or paid for sex.Footnote 55 No campaigns targeting women exclusively during the war years have been identified in the collected sources. However, women were frequently depicted or referenced. An example of this is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows a silhouette of a man approaching a silhouette of a woman under streetlights. The image is accompanied by the text, “Remember that any casual encounter involves the risk of venereal disease.” By alluding to the image of a man approaching “a woman of the streets,” men were encouraged to consider the potential risk of infection. Another poster stated bluntly: “Women who allow sexual intercourse with different or unknown men are often afflicted with such a [venereal] disease. This is especially the case with such women who engage in professional sexual intercourse.”Footnote 56 By depicting women as carriers and men as captives to their sexuality, the campaigns reinforced a stereotype of men’s uncontrolled sexual urges and of women as dangerous and contagious. Similar narratives were also common in belligerent countries’ campaigns, including those in the United States, Norway, and Denmark, where women were publicly blamed for the spread of infection.Footnote 57

The campaigns presented a mix of messages: while promoting abstinence and monogamy as ideals, they also acknowledged that some men would not follow these norms.Footnote 58 Conscripts, especially those on leave, were explicitly advised to use condoms, though these were described as offering only “fairly good protection.”Footnote 59 Women, in contrast, were told that there were “no reliable means to protect themselves from infection,” which likely reinforced their image as carriers.Footnote 60 Condoms were never presented as providing mutual protection in the collected material. In The Air Forces’ Magazine [Luftvärnets tidning], conscripts were encouraged to participate in sports or educational activities rather than pursue casual sexual encounters. The guidance emphasized disease prevention, advising those who did engage in risky behavior to promptly consult their military unit’s physician.Footnote 61 This messaging highlights the dual strategy of promoting moral behavior while pragmatically acknowledging both the inevitability of sexual activity and the need for condoms.

Ambivalence about condoms recurred in several campaigns by the Swedish Board of Medicine. At times, they were promoted as the most effective form of protection, while at other times, they were portrayed as unreliable and unsafe.Footnote 62 These contradictions nevertheless reveal the government’s effort to engineer sexual behavior—steering citizens toward protective practices such as abstinence, monogamy, or condom use. Crucially, by promoting condoms as a prophylactic against venereal disease, authorities implicitly acknowledged that sex occurred outside of marriage and independently of reproductive purposes. This pragmatic stance, while focused on disease prevention, had broader cultural implications by legitimizing practices that separated sex from reproduction, thereby marking a significant deviation from established sexual norms.

In contrast to belligerent countries, Swedish authorities did not discuss condoms in detail or provide user instructions. This lack of specific information led to a minor debate in the daily press in 1944, where authorities were criticized for failing to inform citizens about condom use.Footnote 63 However, detailed guidance was available through commercial advertisements.

Regarding the campaigns’ influence on condom marketing, the public discussion of disease prevention attracted new consumers to health care shops. Some campaigns explicitly urged readers to purchase condoms from health care shops, pharmacies, or the military’s health department.Footnote 64 However, pharmacies accounted for only 0.7 percent of total condom sales in Sweden at the time, and many military facilities did not sell condoms.Footnote 65 In essence, the campaigns primarily directed consumers to health care shops, which effectively received free advertising from the authorities, thereby gaining legitimacy for their line of business. Karin Adamsson, one of the leading businesswomen in the condom retail industry, wrote in her memoirs: “It is only now, during the Second World War, that the general perception of protective products [preventivmedel] changed when authorities began to promote the use of what we call ‘rubbers.’”Footnote 66 The impact on sales was significant. Sölve Adamsson, Karin’s son and business partner, noted in 1944 that condom sales had increased considerably during the war due to official propaganda against venereal diseases.Footnote 67

Overall, the public health campaigns demonstrate a form of social engineering: authorities sought to shape sexual behavior, particularly men’s, toward safer protective practices. A side effect of these campaigns was that they increased public awareness of condoms and, indirectly, lent legitimacy to retailers previously considered controversial. Rising infection rates prompted a shift in condom marketing practices, positioning them as the primary choice due to their dual function as the only commercially available protection against both venereal diseases and pregnancy—a status they still hold today.Footnote 68

Commercial Advertising in Wartime

During the war years, the number of condom advertisements in newspapers declined, according to searches in the digitized press. It is unclear if this trend also applied to brochures and flyers, as these sources have not been archived as extensively. While newspaper advertisements rarely used the war as a sales argument, they often noted that the war affected the domestic supply and quality of condoms. This was especially prominent in brochures, where companies provided detailed explanations of the war’s impact on import routes and the manufacturing of condoms.

Unlike prewar condom advertisements, where birth control was the main sales argument, wartime advertisements urged readers to buy condoms as a “responsible” means of protection against venereal diseases. In an advertising brochure from 1942, retailer Carl R. Larsson warned that condom imports could cease at any moment due to the war, as had happened during World War I. He noted that factories had already begun rationing deliveries and that “inferior smelly crisis goods of replacement material” had entered the market.Footnote 69 Larsson’s statement can be read both as a warning and as practical advice to hoard condoms, or at least to buy a small supply. A recurring selling point emphasized by Larsson was that wartime condom consumption was facilitated by the introduction of latex in manufacturing, which allowed condoms to be stored for up to five years. Given these material conditions, there was no reason to delay purchases.

Similarly, Ernst Lönn, retailer and owner of Sweden’s largest condom import company, frequently addressed the issue of shortages and poor-quality condoms in his brochures. He cautioned both consumers and retailers about the risks of “crisis goods,” which he described as having a kerosene-like smell and causing health issues.Footnote 70 Lönn assured retailers that he still had “peace quality” condoms in stock and urged them to choose his products over those of competitors.Footnote 71 While advertisements often labelled rival products as “inferior” even in peacetime, the war brought a stronger emphasis on educating customers about the health risks associated with these so-called crisis products. Prewar advertisements typically focused on offering high-quality goods to prevent unwanted pregnancies and, to some extent, infections. In contrast, wartime advertisements emphasized the market’s responsibility to avoid products that could cause health risks. This shift reflects an emphasis on maintaining the legitimacy of the condom business at a time when product quality was compromised. Moreover, by informing readers about difficulties in the supply chain, companies tried to portray the consumption of condoms as a necessary consumption.

The newspaper advertisements that did mention the war utilized the increase in venereal diseases as a justification for purchasing condoms, framing them as essential tools in the defense against venereal diseases. This narrative not only aligned with military rhetoric about safety against external threats but also made connections to the public health campaigns aimed at decreasing infection rates. While companies had mentioned the infection-preventing properties of condoms since the 1920s, this argument became even more pronounced during World War II, with a stronger emphasis on the word “protection.” This term shifted during the war, from previously primarily referring to protection against pregnancy, to now focusing on protection against diseases. In this context, sales arguments on fertility control were largely replaced by anti-infection messages. An advertisement from the company HEA, entitled “The Venereal Diseases and the War,” exemplifies this shift.

The war has brought about an unprecedented increase in venereal diseases and efforts have been made everywhere to combat this. In line with these efforts, it may be appropriate to recall the means that exist, but which for various reasons have become synonymous with birth control. Those means are condoms. Through our nationwide organization, we have come to the conclusion that these protective means are not considered as a protection against venereal diseases. An increased knowledge of their great importance would certainly give a quick result.Footnote 72

The advertisement thus positioned the condom not only as a method of birth control but also as a means of preventing infection. This reflects the changing perception of condoms during the war and demonstrates how companies aimed to reframe their intended use. The advertisement also showcases how the company HEA justified its advertising efforts as a way to contribute to the collective, national battle against venereal diseases. Additionally, the advertisement declared that customers could visit their shops to consult “expert staff” on any medical questions, suggesting that commercial actors were trying to establish themselves as intermediaries of medical and hygienic knowledge. This was further emphasized by their use of symbols such as the medical cross in advertisements and shop windows, as well as the instructions to employees to wear white lab coats.Footnote 73

As the public health campaigns proved to be highly successful for the condom business, several companies began mimicking the phrases used by authorities, portraying venereal diseases as a national threat that the entire population needed to combat. In doing so, the companies positioned themselves on the front line of defense, presenting condoms as the only available preventive tool. Advertisements featured headlines such as “Venereal diseases and the war,” “Lower the [infection] curve with protective means!,” “Adamsson’s advice in the fight against venereal diseases,” “Act with responsibility,” and “Do not take any risks!”Footnote 74 This rhetoric emphasized the notion of consumer responsibility and framed the purchase of condoms as a civic duty. Products were described as “reliable,” “genuine,” and often advertised as being of “peace quality.” Many advertisements also used terms like “safety” and “security” to describe the goods.Footnote 75 For instance, in Figure 2, an advertisement from Nils Adamsson’s health care shop portrayed a man in a lab coat pointing a warning finger alongside the headline “An Obligation to Yourself and Society.” While arguments alluding to responsibility and duty were not new in condom advertising, the combination of imagery and authoritative language created a serious tone in which the reader was being admonished by an authoritative figure to take condom use seriously.

Figure 2. “An Obligation to Yourself and Society,” Newspaper advertisement from Nils Adamssons sjukvårdsaffär in Dagens Nyheter, July 12, 1945.

In this context, the condom business positioned itself as part of the mobilization of the home front in the war against venereal diseases. By aligning their marketing strategies with the rhetoric of the military and public health campaigns, companies engineered condom consumers as not only responsible for one’s individual health but also as vital actors in the collective effort to combat the spread of disease. For an industry viewed—at the time—as dubious, unethical, and on the verge of illegality, this alignment with state messages and medical science helped legitimize both the advertising and the sales of contraceptives and prophylactics in general, and specifically of the condom. The serious tone in these advertisements during the war underscores how businesses sought to demonstrate their commitment to the home front’s preparedness during a time of crisis.

In Sickness and in Health, In Wartime and in Peace: Postwar Marketing of Condoms

Venereal infection is a serious public danger. As is often the case during and after a war, it has also been possible to note the increase in venereal diseases in our country this time as well. Even though we escaped the war, we have had extensive military conscription, which brought with it increased casual sexual encounters. […] The venereal disease casts a shadow over the present and the future, which is why all good forces must unite in the fight against it.Footnote 76

The quote comes from an article published in the newspaper The Work [Arbetet] in 1947 and clearly illustrates that although the war ended in 1945, the battle against venereal diseases continued throughout the 1940s. The postwar period in Sweden, often referred to as “the record years,” was marked by rapid economic growth and a significant increase in consumer activity.Footnote 77 In the immediate postwar years, consumption increased, and by 1947, most citizens achieved or exceeded prewar standards of living.Footnote 78 As disposable income rose, the entertainment industry thrived, with dances and restaurants becoming popular social venues. According to media reports, these gatherings fueled an increase in casual sexual relations, contributing to the spread of venereal diseases.Footnote 79 To counter the continued high rates of infection, Stockholm Municipality initiated a large campaign against venereal diseases by the end of the war, targeting the entire country.

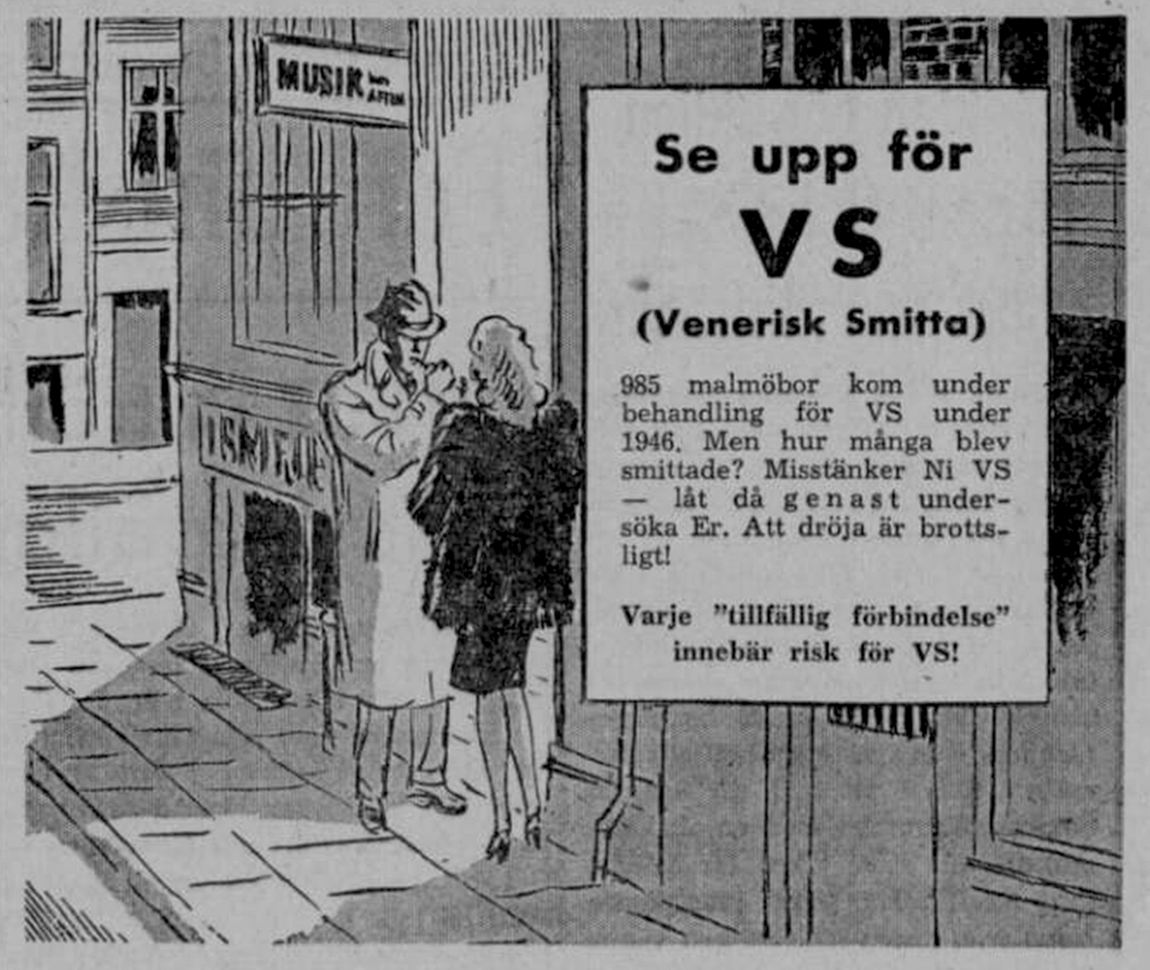

In 1946, “his” and “her” brochures with the titles I Didn’t Think That About Him and I Didn’t Think That About Her were distributed across the country from the Stockholm municipal board to pharmacies, workplaces, and health care shops. The municipality also invested heavily in newspaper advertising, in which they told readers to be aware of venereal diseases. These advertisements had illustrations of men engaging in conversation with what seems to be prostitutes (Figure 3), or of young men and women dancing and kissing at parties (Figure 4), and had headlines such as: “Watch out for Venereal Infection,” “It was dangerous!” and “Venereal disease is ravaging the country, and the risk of infection is high.”Footnote 80 In contrast to wartime campaigns, postwar campaigns targeted both men and women, urging them to stay sober, avoid casual sexual relations, and trust no one. Men were also frequently encouraged to visit public clinics immediately after sexual encounters. These campaigns persisted throughout the 1940s, contributing to an ongoing public discourse that framed sexual safety and security as civic responsibilities, which the condom business could take advantage of.

Figure 3. “Watch out for Venereal Infection,” Newspaper advertisement from Stockholm Municipality in Arbetet, March 11, 1947.

Figure 4. “Watch out for Venereal Infection,” Newspaper advertisement from Stockholm Municipality in Arbetet, March 31, 1947.

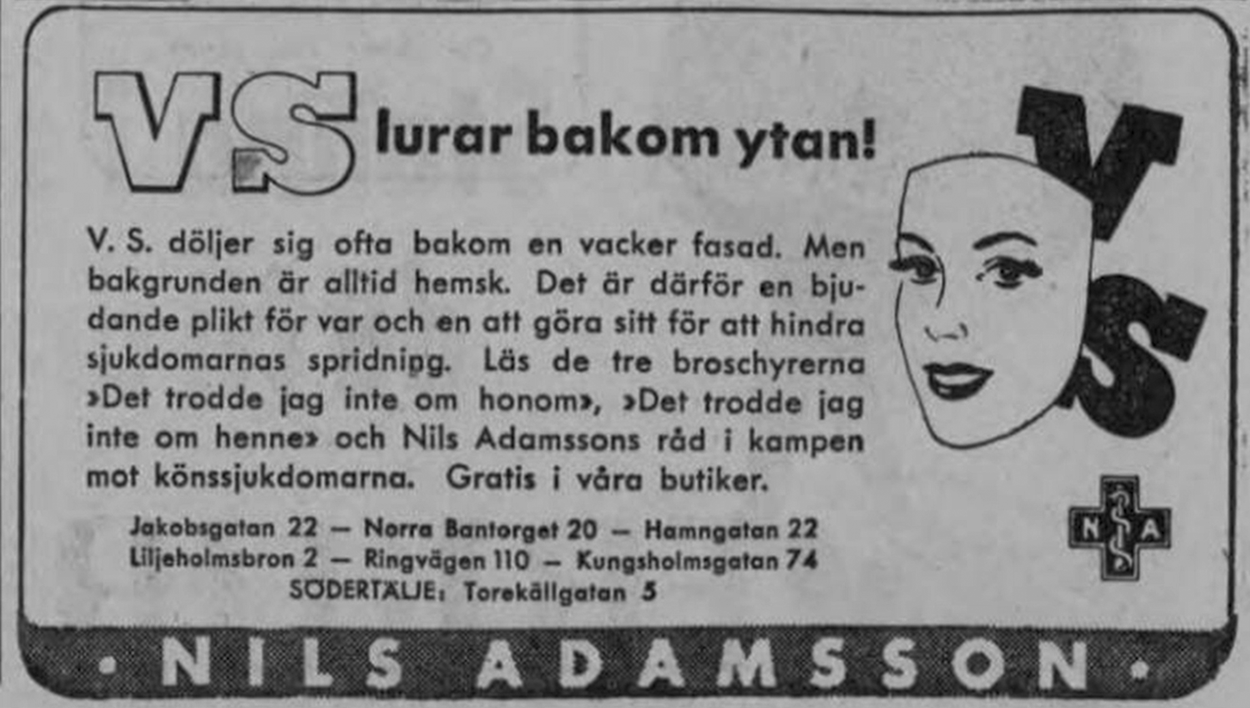

Against this backdrop, Nils Adamsson’s health care shop published several advertisements with messages that lectured readers on their responsibility to use condoms. One ad, titled “VI [Venereal Infection] Are Lurking Beneath the Surface!” depicted a mask, suggesting that beauty can be deceptive and that infections may hide beneath the surface. It also included a warning: “V.I. are often hiding behind a beautiful facade. But the background is always horrible. It is therefore an imperative duty for everyone to do their part to prevent the spread of diseases” (Figure 5). The advertisement implied that even the most attractive women could be carriers of venereal diseases, reinforcing the narrative of wartime public health campaigns: that men risked infection from women if they were not vigilant. Additionally, there is a notable similarity in the graphic profiles of the commercial advertisements and the public health campaigns (see Figures 3–5), which illustrate how Adamsson’s health care shop continued to adapt to the authorities’ imagery and language.

Figure 5. “VI [Venereal Infections] are Lurking Beneath the Surface,” Newspaper advertisement from Nils Adamssons sjukvårdsaffär in Dagens Nyheter, October 31, 1946.

By 1950, condom imports to Sweden had increased from approximately 4.75 million in 1938 to 14.4 million in 1950.Footnote 81 As Andrea Tone has argued in relation to the US case, contraceptive companies did not create the desire to control fertility or avoid infection; rather, they capitalized on people’s fears in order to boost profits.Footnote 82 A prominent strategy in both commercial advertisements and public health campaigns was to remind the public of the severe consequences of venereal diseases. While earlier commercial brochures focused on technological advances and new scientific findings related to reproduction and disease prevention, postwar brochures provided more detailed descriptions of illnesses and their treatments. In line with Tone’s argument, these brochures warned readers about the dangers of gonorrhea, including scarring, infertility, and “violent pains,” while emphasizing that condoms were the only reliable form of protection available.Footnote 83

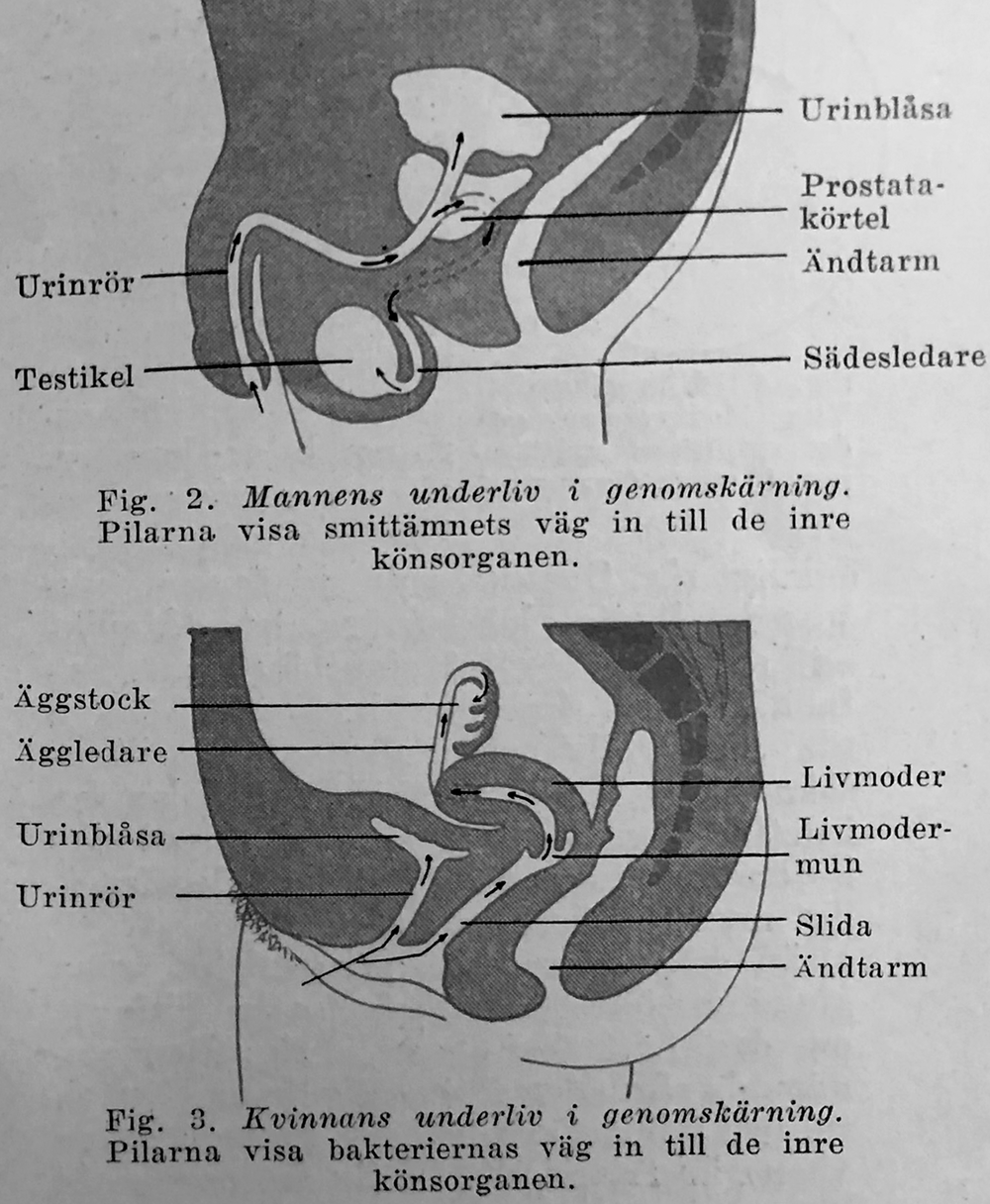

In 1946 and 1947, several commercial brochures were released that provided extensive information on the spread of venereal diseases. Notably, Nils Adamsson’s health care shop published multiple editions of a brochure titled Adamsson’s Advice in the Fight Against Venereal Diseases in 1946. The title itself suggests that the battle against venereal diseases was framed not only as a public health effort but also as an area in which the company sought to establish authority. The brochure provided detailed written information on disease transmission, accompanied by illustrations in which arrows depicted how bacteria traveled and infected the genitals (Figure 6). This highly medicalized language and imagery exemplifies how representations of venereal disease became integrated into condom advertisements.

Figure 6. Cross-section illustration of bacteria spreading in the genitals.

Source: Nils Adamssons sjukvårdsaffär, Adamssons råd i kampen mot könssjukdomarna, 1946.

The advancements in antibacterial treatments during World War II had heightened public awareness of bacteria, which was reflected in condom advertising. Some condoms were even marketed as “antibacterial” during the war, further amplifying fears of infection.Footnote 84 Advertisements enhanced fears, not only for the diseases themselves but also for the treatment. Readers were encouraged to quickly seek medical attention or to self-administer treatments, injecting albargin solution into the urethra and applying mercurial salve to the genitals—a painful treatment method that was used before penicillin.Footnote 85 Brochures emphasized the pain and horrors of illness through detailed descriptions of treatments. However, they consistently concluded with the message that condoms were the most effective means of protection. Surprisingly, these discussions neglected to mention penicillin, despite its newly found revolutionary impact on the treatment of venereal diseases.

As historian Andrew M. Francis has noted, the American health care system introduced penicillin for treating venereal diseases during World War II.Footnote 86 In Sweden, the pharmaceutical company Astra began producing penicillin in 1944, and by 1946, it was described as widely used to treat venereal diseases.Footnote 87 While recognizing penicillin’s effectiveness, the Board of Medicine cautioned the public against overreliance on the new treatment. In 1945, articles with alarming headlines such as “Excessive Faith in Penicillin Increases Venereal Diseases” and “Penicillin Does Not Always Cure Venereal Diseases” reflected concerns that the new treatment might encourage riskier sexual behavior.Footnote 88 In 1946, the author Herbert Connor argued that this was already the case—that penicillin had led to a decline in condom use among young people who believed they could now rely on a quick, painless cure.Footnote 89 This shift in behavior risked a decline in condom use and an increase in public health care costs since treatments were financially covered by the government. In light of this, the condom retailers’ detailed descriptions of diseases and previous treatment methods, combined with the lack of information about penicillin, can be interpreted as a strategic effort to scare readers into continuing to buy condoms.

Postwar newspaper advertisements continued to emphasize safety and quality. Companies like Nils Adamsson’s and Carl R. Larsson’s health care shops promoted “peace quality” goods well into the 1950s. This emphasis on quality can be understood within the broader context of the era, which was marked by a shift from a wartime economy characterized by scarcity and rationing to a peacetime economy where consumers sought to restore a sense of normality and security. During the war, many products suffered from lower quality due to material shortages, leading to complaints about condoms being unpleasant and ineffective.Footnote 90 For condom retailers, promoting “peace quality” goods was a way to reassure consumers about the safety and effectiveness of their products, while also positioning these commodities as a return to prewar standards. This was particularly evident when companies began advertising “the return of American goods” in 1945 and onwards.Footnote 91

Furthermore, the concept of quality gained heightened significance in the field of public health. The lingering fears of wartime diseases and the ongoing threat of venereal infections made consumers especially aware of the necessity for reliable and effective protection. Advertisements that emphasized the superior quality of condoms played into these anxieties, suggesting that only the best products could provide the necessary protection. The use of phrases like “unmatched in strength and reliability” emphasized that quality was not just a matter of consumer preference; it was a crucial aspect of personal safety and public health.Footnote 92 By invoking arguments on quality, condom retailers were able to tap into the postwar desire for security and trustworthiness, ensuring that their products remained essential in the eyes of consumers.

Additionally, the government had an interest in ensuring that products were efficient, which led to the introduction of quality control and standardization for diaphragms and condoms sold in pharmacies in 1951.Footnote 93 By 1959, the regulations extended to the entire market.Footnote 94 In other words, the heightened need for safe protection during World War II led to a permanent change in the marketing of condoms in Sweden. Similar to what historian Frank Trentmann has argued, the Swedish market for condoms also exemplifies how wartime pressures fostered new expertise in managing and understanding consumption, which continued to shape policy making and marketing in the postwar era.Footnote 95

From the mid-1950s onward, Sweden became known for its radical sexual policies, not least because it was the first country to introduce mandatory sex education in elementary schools in 1955.Footnote 96 This education emphasized protective practices against venereal disease but did not necessarily promote birth control, echoing wartime and postwar public health campaigns that prioritized public health issues over individual reproductive choice.Footnote 97 As several scholars have noted, the introduction of compulsory school sex education was a result of a larger process that had made sexuality a political concern in Sweden.Footnote 98 This article, however, argues that the war years marked a critical turning point in the state’s approach to sexuality. Faced with rising infection rates, the Swedish government began promoting condoms as legitimate prophylactics, contributing to the decoupling of sex from reproduction in public discourse. This shift contributed to establishing a more secular and pragmatic approach to issues of sexual regulation and health that endured well beyond the war years. Rather than reverting to prewar moral frameworks, postwar policies upheld a public health rationale, paving the way for later reforms such as the standardization of diaphragms and condoms, and mandatory sex education in the 1950s. In this sense, wartime health campaigns and commercial condom advertising did more than address a medical crisis—they also contributed to reshaping the boundaries of legitimate sexuality in Sweden’s emerging welfare state.

Conclusion and Discussion

This article has demonstrated how wartime conditions, specifically infection rates and government interventions, influenced the marketing practices for condoms in Sweden. By analyzing public health campaigns and advertising strategies from the preparedness years through the immediate postwar period, it becomes evident that both the state and businesses contributed to transforming condoms from a birth control method into a key tool for disease prevention. Retailers shifted their focus from highlighting a range of different products to mainly emphasizing the condom, and particularly as a protection for men. This narrative cemented the condom’s status as the only commercial protection against venereal diseases—a status it holds to this day. This shift, driven by the rise in venereal diseases during World War II, redefined condom use as a matter of public health and a civic responsibility.

The relationship between social engineering, aimed at reducing infection rates, and consumer engineering, driven by the goal of increasing sales, created a unique dynamic. Wartime campaigns sought to engineer citizens’ sexual behavior, while businesses strategically aligned their messaging with government propaganda. This convergence was instrumental in positioning condoms as essential tools for public health, effectively bridging state-led public health efforts with commercial objectives.

Unlike in the United States, where wartime tolerance for condom use gave way to restrictive policies after the war, Sweden’s technocratic state maintained a supportive stance. While scholars such as Brandt and Jones have observed that public health campaigns may have influenced condom use in the United States and United Kingdom during the war, this article demonstrates that health campaigns in Sweden persisted after the war, signaling a broader shift toward a more permissive attitude regarding condoms. Additionally, government agencies had an interest in encouraging the consumption of condoms, as this was both a public health measure and a cost-saving strategy, given that the government was financially responsible for venereal disease treatments. The legalization of contraceptive information in 1939 was also crucial, as it allowed government authorities and businesses to openly promote condom use. However, it was the war itself that served as a catalyst for this rapid change. Military mobilization created new sexual dynamics, including an increased prevalence of venereal diseases and a more integrated approach to public health and condom marketing.

Public health campaigns during the war framed monogamy, abstinence, and condom use as the primary protections against venereal diseases, transforming sickness from a private issue into a public health priority. These efforts exemplify social engineering by authorities, such as the Board of Medicine, which engaged in constructing behavioral templates for “good citizenship” in infection prevention. Lex Veneris, which had criminalized the spread of venereal diseases since 1919, gained new significance during the war, as it became entwined with propaganda efforts to redefine exemplary sexual behavior. This change in attitude toward condoms, driven by both necessity and opportunity, laid important groundwork for the broader cultural transformations that followed in the postwar era, including the more open discourse on sexuality that gained momentum in the 1960s.

Through militarized and medicalized messaging in advertisements, businesses framed condom use as both a personal and civic responsibility. This finding expands upon the work of Clampin as well as Arnberg et al., who argue that consumption in wartime was framed as a civic duty. Condom retailers advanced this notion further by positioning themselves as part of the home-front defense in the battle against venereal diseases. Moreover, the success of advertising condoms as the primary “protective product” was twofold: it not only encouraged men and women to use protection against venereal diseases but also created a sustainable consumer base for commercially produced contraceptives, reducing reliance on non-commercial methods such as withdrawal. By aligning themselves with public health initiatives, businesses strengthened their legitimacy and deepened their relationship with the state, contributing to a notable increase in condom consumption between 1938 and 1950. This finding further indicates that the rise in contraceptive consumption cannot be explained solely by an increased demand for fertility control, as emphasized by Jones, but should also be interpreted in light of condoms’ disease-preventive function.

Postwar public health priorities sustained the influence of venereal diseases on condom marketing, and advertisements maintained the language of wartime campaigns, emphasizing safety and reliability. Fear-based tactics warned consumers about the dangers of venereal diseases and the discomfort of treatments. Meanwhile, advertisements avoided mentioning the introduction of penicillin, a painless treatment for venereal diseases, likely due to its threat to condom sales. By playing into fears of illness and painful treatments, advertisements kept condom use relevant, and by doing so ensured its continued place in public health discourse.

Quality control measures for condoms and diaphragms, introduced in pharmacies in 1951 and expanded to the entire market in 1959, represented another enduring outcome of wartime transformations. These measures, combined with postwar demands for safety and trust, further solidified the condom’s role as a reliable product for both personal and public health. This regulatory development highlights how wartime conditions influenced state attitudes toward condoms, illustrating that these changes were not temporary but foundational to the ongoing transformation of societal norms surrounding sex and reproduction.

In conclusion, World War II and the rise in venereal diseases had a transformative impact on marketing practices and societal perception of condoms in Sweden. The alignment of state-led public health initiatives with commercial strategies reshaped attitudes toward condoms, positioning them as essential tools for both individual and public responsibility. These shifts had lasting effects, setting the stage for Sweden’s progressive sexual politics from the 1950s onward and offering valuable insights into the intersections of state policy, commercial strategy, and societal change. While much of the existing literature has focused on the United States and United Kingdom, this study has shown that Sweden’s technocratic state sustained and adapted wartime policies in ways that diverged from more restrictive postwar shifts elsewhere, illustrating a distinctive alignment of public health and market strategies.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Klara Arnberg, Nikolas Glover, and the Marketing History Workshop at Uppsala University for insightful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Funding statement

The publication is part of the project The Defense of Consumption: Advertising, Gender and Citizenship in Sweden during World War II, funded by the Swedish Research Council (2018–01457).

Appendix

Figure A1. Number of reported cases of venereal disease in Sweden, 1913–1950.

Note: Compiled by the author.

Source: Information on the number of registered persons with venereal diseases 1913–1919 is published in Wallerström, Vad vi veta, 1926, 95; Information on the number of registered persons with venereal diseases 1919–1950 is published in Statistisk årsbok för Sverige, 1924–1951.