1 Introduction

Defining abstractions that support both programming with and reasoning about side effects is a research question with a long and rich history. The goal is to define an abstract interface of (possibly) side-effecting operations together with equations describing their behavior, where the interface hides operational details about the operations and their side effects that are irrelevant for defining or reasoning about a program. Such encapsulation makes it easy to refactor, optimize, or even change the behavior of a program while preserving proofs, by changing the implementation of the interface.

Monads (Reference MoggiMoggi, 1989b ) have long been the preferred solution to this research question, but they lack modularity: given two computations defined in different monads, there is no canonical way to combine them that is both universally applicable and preserves modular reasoning. This presents a problem for scalability since, in practice, programs, and therefore proofs, are developed incrementally. Algebraic effects and handlers (Plotkin & Power, Reference Plotkin and Power2002; Plotkin & Pretnar, Reference Plotkin and Pretnar2009) provide a solution for this problem by defining a syntactic class of monads, which permits composition of syntax, equational theories, and proofs. Algebraic effects and handlers maintain a strict separation of syntax and semantics, where programs are only syntax, and semantics is assigned later on a per-effect basis using handlers.

Many common operations, however, cannot be expressed as syntax in this framework. Specifically, higher-order operations that take computational arguments, such as exception, catching or modifying environments in the reader monad. While it is possible to express higher-order operations by inlining handler applications within the definition of the operation itself, this effectively relinquishes key modularity benefits. The syntax, equational theories, and proofs of such inlined operations do not compose.

In this paper, we propose to address this problem by appealing to an overloading mechanism which postpones the choice of handlers to inline. As we demonstrate, this approach provides a syntax and semantics of higher-order operations with similar modularity benefits as traditional algebraic effects; namely syntax, equational theories, and proofs that compose. To realize this, we use a syntactic class of monads that supports higher-order operations (which we dub hefty trees). Algebras over this syntax (hefty algebras) let us modularly elaborate this syntax into standard algebraic effects and handlers. We show that a wide variety of higher-order operations can be defined and assigned a semantics this way. Crucially, program definitions using hefty trees enjoy the same modularity properties as programs defined with algebraic effects and handlers. Specifically, they support the composition of syntax, semantics, equational theories, and proofs. This demonstrates that overloading is not only syntactically viable but also supports the same modular reasoning as algebraic effects for programs with side effects that involve higher-order operations.

1.1 Background: Algebraic effects and handlers

To understand the modularity benefits of algebraic effects and handlers, and why this modularity breaks when defining operations that take computations as parameters, we give a brief introduction to algebraic effects. To this end, we will use informal examples using a simple calculus inspired by Pretnar’s calculus for algebraic effects (Pretnar, Reference Pretnar2015). Section 2 of this paper provides a semantics for algebraic effects and handlers in Agda which corresponds to this calculus.

1.1.1 Effect signatures

Say we want an effectful operation

![]() ${out}$

for printing output. Besides its side effect of printing output, the operation should take a string as an argument and return the unit value. Using algebraic effects, we can declare this operation using the following effect signature:

${out}$

for printing output. Besides its side effect of printing output, the operation should take a string as an argument and return the unit value. Using algebraic effects, we can declare this operation using the following effect signature:

We can use this operation in any program that has the

![]() ${Output}$

effect. For example, the following

${Output}$

effect. For example, the following

![]() ${hello}$

program:

${hello}$

program:

The type

![]() ${{()}}\mathop{!}{Output}$

indicates that

${{()}}\mathop{!}{Output}$

indicates that

![]() ${hello}$

is an effectful computation which returns a unit value, and which is allowed to call the operations in

${hello}$

is an effectful computation which returns a unit value, and which is allowed to call the operations in

![]() ${Output}$

(i.e., only the

${Output}$

(i.e., only the

![]() ${out}$

operation).

${out}$

operation).

More generally, computations of type

![]() ${A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

are allowed (but not required) to call any operation of any effect in

${A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

are allowed (but not required) to call any operation of any effect in

![]() $\Delta$

, where

$\Delta$

, where

![]() $\Delta$

is a row (i.e., unordered sequence) of effects. An effect is essentially a label associated with a set of operations. The association of labels to operations is declared using effect signatures, akin to the signature for

$\Delta$

is a row (i.e., unordered sequence) of effects. An effect is essentially a label associated with a set of operations. The association of labels to operations is declared using effect signatures, akin to the signature for

![]() ${Output}$

above.

${Output}$

above.

1.1.2 Effect theories

A crucial feature of algebraic effects and handlers is that it permits abstract reasoning about programs containing effects, such as

![]() ${hello}$

above. That is, each effect is associated with a set of laws that characterizes the behavior of its operations. Their purpose is to constrain an effect’s behavior without appealing to any specifics of the implementation of the effects. Consequently, program proofs derived from these equations remain valid for all handler implementations satisfying the laws of its equational theory.

${hello}$

above. That is, each effect is associated with a set of laws that characterizes the behavior of its operations. Their purpose is to constrain an effect’s behavior without appealing to any specifics of the implementation of the effects. Consequently, program proofs derived from these equations remain valid for all handler implementations satisfying the laws of its equational theory.

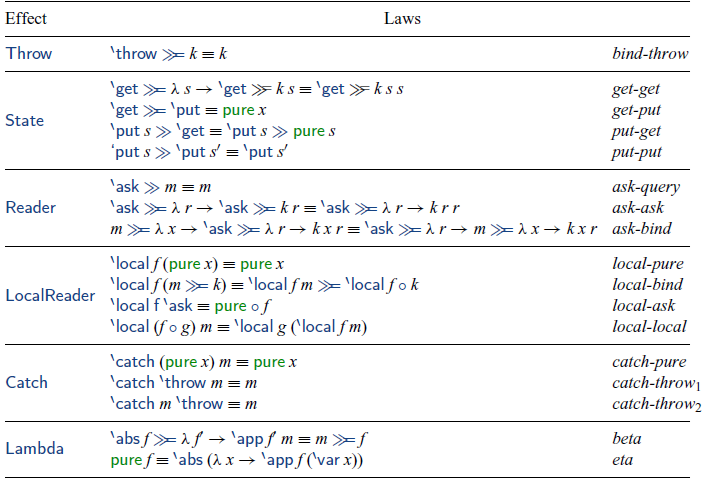

Importantly, these laws are purely syntactic, in the sense that they are part of the effect’s specification rather than representing universal truths about the behavior of effectful computation. Whether a law is “valid” depends entirely on how we handle the effects, and different handlers may satisfy different laws. Figuring out a suitable set of laws is part of the development process of (new) effects. Typically, the final specification of an effect is the result of a back-and-forth refinement between an effect’s specification and its handler implementations. This process ultimately converges to a definition that matches our intuitive understanding of what an effect should do.

For example, the

![]() ${Output}$

effect has a single law that characterizes the behavior of

${Output}$

effect has a single law that characterizes the behavior of

![]() ${out}$

:

${out}$

:

Here,

![]() $\mathrel{+\mkern-5mu+}$

is string concatenation. Using this law, we can prove that our

$\mathrel{+\mkern-5mu+}$

is string concatenation. Using this law, we can prove that our

![]() ${hello}$

program will print the string “Hello world!”. Crucially, this proof does not depend on operational implementation details of the

${hello}$

program will print the string “Hello world!”. Crucially, this proof does not depend on operational implementation details of the

![]() ${Output}$

effect. Instead, it uses the laws of the equational theory of the effect. While the program and effect discussed so far has been deliberately simple, the approach illustrates how algebraic effects let us reason about effectful programs in a way that abstracts from the concrete implementation of the underlying effects.

${Output}$

effect. Instead, it uses the laws of the equational theory of the effect. While the program and effect discussed so far has been deliberately simple, the approach illustrates how algebraic effects let us reason about effectful programs in a way that abstracts from the concrete implementation of the underlying effects.

1.1.3 Effect handlers

An alternative perspective is to view effects as interfaces that specify the parameter, return type, and laws of each operation. Implementations of such interfaces are given by effect handlers. An effect handler essentially defines how to interpret operations in the execution context they occur in. This interpretation must be consistent with the laws of the effect. (We will not dwell further on this consistency here; we return to this in Section 5.6.)

The type of an effect handler is

![]() ${A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}~\Rightarrow~{B}\mathop{!}{\Delta^\prime}$

, where

${A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}~\Rightarrow~{B}\mathop{!}{\Delta^\prime}$

, where

![]() $\Delta$

is the row of effects before applying the handler and

$\Delta$

is the row of effects before applying the handler and

![]() $\Delta^\prime$

is the row after. For example, here is a specific type of an effect handler for

$\Delta^\prime$

is the row after. For example, here is a specific type of an effect handler for

![]() ${Output}$

:Footnote

1

${Output}$

:Footnote

1

The

![]() ${Output}$

effect is being handled, so it is only present in the effect row on the left.Footnote

2

As the type suggests, this handler handles

${Output}$

effect is being handled, so it is only present in the effect row on the left.Footnote

2

As the type suggests, this handler handles

![]() ${out}$

operations by accumulating a string of output. Below is an example implementation of this handler:

${out}$

operations by accumulating a string of output. Below is an example implementation of this handler:

The

![]() $\mathbf{return}{}$

case of the handler says that, if the computation being handled terminates normally with a value x, then we return a pair of x and the empty string. The case for

$\mathbf{return}{}$

case of the handler says that, if the computation being handled terminates normally with a value x, then we return a pair of x and the empty string. The case for

![]() ${out}$

binds a variable s for the string argument of the operation, but also a variable k representing the execution context (or continuation). Invoking an operation suspends the program and its execution context up-to the nearest handler of the operation. The handler can choose to re-invoke the suspended execution context (possibly multiple times). The handler case for

${out}$

binds a variable s for the string argument of the operation, but also a variable k representing the execution context (or continuation). Invoking an operation suspends the program and its execution context up-to the nearest handler of the operation. The handler can choose to re-invoke the suspended execution context (possibly multiple times). The handler case for

![]() ${out}$

above always invokes k once. Since k represents an execution context that includes the current handler, calling k gives a pair of a value y and a string

${out}$

above always invokes k once. Since k represents an execution context that includes the current handler, calling k gives a pair of a value y and a string

![]() $s^\prime$

, representing the final value and output of the execution context. The result of handling

$s^\prime$

, representing the final value and output of the execution context. The result of handling

![]() ${out}~s$

is then y and the current output (s) plus the output of the rest of the program (

${out}~s$

is then y and the current output (s) plus the output of the rest of the program (

![]() $s^\prime$

).

$s^\prime$

).

In general, a computation

![]() $m : {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

can only be run in a context that provides handlers for each effect in

$m : {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

can only be run in a context that provides handlers for each effect in

![]() $\Delta$

. To this end, the expression

$\Delta$

. To this end, the expression

![]() $\textbf{with}~{h}~\textbf{handle}~{m}$

represents applying the handler h to handle a subset of effects of m. For example, we can run the

$\textbf{with}~{h}~\textbf{handle}~{m}$

represents applying the handler h to handle a subset of effects of m. For example, we can run the

![]() ${hello}$

program from earlier with the handler

${hello}$

program from earlier with the handler

![]() ${hOut}$

to compute the following result:

${hOut}$

to compute the following result:

The key benefit of algebraic effects and handlers is that programs such as

![]() ${hello}$

are defined independently of how the effectful operations they use are implemented. This makes it possible to reason about programs independently of how the underlying effects are implemented and also makes it possible to refine, refactor, and optimize the semantics of operations, without having to modify the programs that use them. For example, we could refine the meaning of

${hello}$

are defined independently of how the effectful operations they use are implemented. This makes it possible to reason about programs independently of how the underlying effects are implemented and also makes it possible to refine, refactor, and optimize the semantics of operations, without having to modify the programs that use them. For example, we could refine the meaning of

![]() ${out}$

without modifying the

${out}$

without modifying the

![]() ${hello}$

program or proofs derived from equations of the

${hello}$

program or proofs derived from equations of the

![]() ${Output}$

effect, by using a different handler which prints output to the console. However, some operations are challenging to express while retaining the same modularity benefits.

${Output}$

effect, by using a different handler which prints output to the console. However, some operations are challenging to express while retaining the same modularity benefits.

1.2 The modularity problem with higher-order operations

We discuss the problem with defining higher-order operations using effect signatures (Section 1.2.1) and potential workarounds (Sections 1.2.2 and 1.2.3).

1.2.1 The problem

Say we want to declare an operation

![]() ${censor}\, f\, m$

, which applies a censoring function

${censor}\, f\, m$

, which applies a censoring function

![]() $f : {String} \to {String}$

to the side-effectful output of the computation m. We might try to declare an effect

$f : {String} \to {String}$

to the side-effectful output of the computation m. We might try to declare an effect

![]() ${Censor}$

with a

${Censor}$

with a

![]() ${censor}$

operation by the following type:

${censor}$

operation by the following type:

However, using algebraic effects, we cannot declare

![]() ${censor}$

as an operation.

${censor}$

as an operation.

The problem is that effect signatures do not offer direct support for declaring operations with computation parameters. Effect signatures have the following shape:

Here, each operation parameter type

![]() $A_i$

is going to be typed as a value. While we may pass around computations as values, passing around computations as arguments of computations is not a desirable approach to defining higher-order operations in general. We will return to this point in Section 1.2.2.

$A_i$

is going to be typed as a value. While we may pass around computations as values, passing around computations as arguments of computations is not a desirable approach to defining higher-order operations in general. We will return to this point in Section 1.2.2.

The fact that effect signatures do not directly support operations with computational arguments is also evident from how handler cases are typed (Pretnar, Reference Pretnar2015, Fig. 6):

Here, A is the argument type of an operation, and B is the return type of an operation. The term c represents the code of the handler case, which must have type

![]() $C~!~\Delta^\prime$

.

$C~!~\Delta^\prime$

.

Observe how only the continuation k that is statically known to have computation type which matches the effects of the context in which the handler is applied. While the argument type A could be instantiated with a computation type

![]() $A~!~\Delta^{\prime\prime}$

, the effects of this computation are hardcoded in the definition of the operation. Because handlers are agnostic to the row

$A~!~\Delta^{\prime\prime}$

, the effects of this computation are hardcoded in the definition of the operation. Because handlers are agnostic to the row

![]() $\Delta^\prime$

of effects that they do not handle, and since in general

$\Delta^\prime$

of effects that they do not handle, and since in general

![]() $\Delta^\prime~\neq~\Delta^{\prime\prime}$

, we are forced, in a clear violation of modularity, to hardcode the handler for

$\Delta^\prime~\neq~\Delta^{\prime\prime}$

, we are forced, in a clear violation of modularity, to hardcode the handler for

![]() $\Delta^{\prime\prime}$

as well. As a result, the only option for defining operations with computation parameters that preserves modularity is to encode them in the continuation k.

$\Delta^{\prime\prime}$

as well. As a result, the only option for defining operations with computation parameters that preserves modularity is to encode them in the continuation k.

A consequence of this observation is that we can only define and modularly handle higher-order operations whose computation parameters are continuation-like. Following Plotkin & Power (Reference Plotkin and Power2003), such operations satisfy the following law, known as the algebraicity property. For any operation

![]() ${op} : {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta} \to \cdots \to {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta} \to {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

and any

${op} : {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta} \to \cdots \to {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta} \to {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

and any

![]() $m_1,\ldots,m_n$

and k,

$m_1,\ldots,m_n$

and k,

The law says that the computation parameter values

![]() $m_1,\ldots,m_n$

are only ever run in a way that directly passes control to k. Such operations can without loss of generality or modularity be encoded as operations without computation parameters;Footnote

3

i.e., as algebraic operations that match the handler typing in (*) above.

$m_1,\ldots,m_n$

are only ever run in a way that directly passes control to k. Such operations can without loss of generality or modularity be encoded as operations without computation parameters;Footnote

3

i.e., as algebraic operations that match the handler typing in (*) above.

Some higher-order operations obey the algebraicity property; many do not. Examples that do not obey algebraicity include:

-

• Exception handling: let

${catch}~m_1~m_2$

be an operation that handles exceptions thrown during evaluation of computation

${catch}~m_1~m_2$

be an operation that handles exceptions thrown during evaluation of computation

$m_1$

by running

$m_1$

by running

$m_2$

instead, and

$m_2$

instead, and

${throw}$

be an operation that throws an exception. These operations are not algebraic. For example,

${throw}$

be an operation that throws an exception. These operations are not algebraic. For example,  \[ \mathbf{do}~({catch}~m_1~m_2); {throw}\ \not\equiv\ {catch}~(\mathbf{do}~m_1; {throw})~(\mathbf{do}~m_2; {throw}) \]

\[ \mathbf{do}~({catch}~m_1~m_2); {throw}\ \not\equiv\ {catch}~(\mathbf{do}~m_1; {throw})~(\mathbf{do}~m_2; {throw}) \]

-

• Local binding (the reader monad Jones, Reference Jones1995): let

${ask}$

be an operation that reads a local binding, and

${ask}$

be an operation that reads a local binding, and

${local}~r~m$

be an operation that makes r the current binding in computation m. Observe:

${local}~r~m$

be an operation that makes r the current binding in computation m. Observe:  \[ \mathbf{do}~({local}~r~m); {ask} \ \not\equiv\ {local}~r~(\mathbf{do}~m; {ask}) \]

\[ \mathbf{do}~({local}~r~m); {ask} \ \not\equiv\ {local}~r~(\mathbf{do}~m; {ask}) \]

-

• Logging with censoring (an extension of the writer monad Jones, Reference Jones1995): let

${out}~s$

be an operation for logging a string, and

${out}~s$

be an operation for logging a string, and

${censor}~f~m$

be an operation for post-processing the output of computation m by applying

${censor}~f~m$

be an operation for post-processing the output of computation m by applying

$f : {String} \to {String}$

.Footnote

4

Observe:

$f : {String} \to {String}$

.Footnote

4

Observe:  \[ \mathbf{do}~({censor}~f~m); {out}~s \ \not\equiv\ {censor}~f~(\mathbf{do}~m; {out}~s) \]

\[ \mathbf{do}~({censor}~f~m); {out}~s \ \not\equiv\ {censor}~f~(\mathbf{do}~m; {out}~s) \]

-

• Function abstraction as an effect: let

${abs}~x~m$

be an operation that constructs a function value binding x in computation m,

${abs}~x~m$

be an operation that constructs a function value binding x in computation m,

${app}~v~m$

be an operation that applies a function value v to an argument computation m, and

${app}~v~m$

be an operation that applies a function value v to an argument computation m, and

${var}~x$

be an operation that dereferences a bound x. Observe:

${var}~x$

be an operation that dereferences a bound x. Observe:  \[ \mathbf{do}~({abs}~x~m); {var}~x \ \not\equiv\ {abs}~x~(\mathbf{do}~m; {var}~x) \]

\[ \mathbf{do}~({abs}~x~m); {var}~x \ \not\equiv\ {abs}~x~(\mathbf{do}~m; {var}~x) \]

1.2.2 Potential workaround: Computations as arguments of operations

A tempting possible workaround to the issues summarized in Section 1.2.1 is to declare an effect signature with a parameter type

![]() $A_i$

that carries effectful computations. However, this workaround can cause operations to escape their handlers. Following Pretnar (Reference Pretnar2015), the semantics of effect handling obeys the following law.Footnote

5

If h handles operations other than

$A_i$

that carries effectful computations. However, this workaround can cause operations to escape their handlers. Following Pretnar (Reference Pretnar2015), the semantics of effect handling obeys the following law.Footnote

5

If h handles operations other than

![]() ${op}$

, then:

${op}$

, then:

This law tells us that effects in v will not be handled by h. This is problematic if h is the intended handler for one or more effects in v. The solution we describe in Section 1.3 does not suffer from this problem.

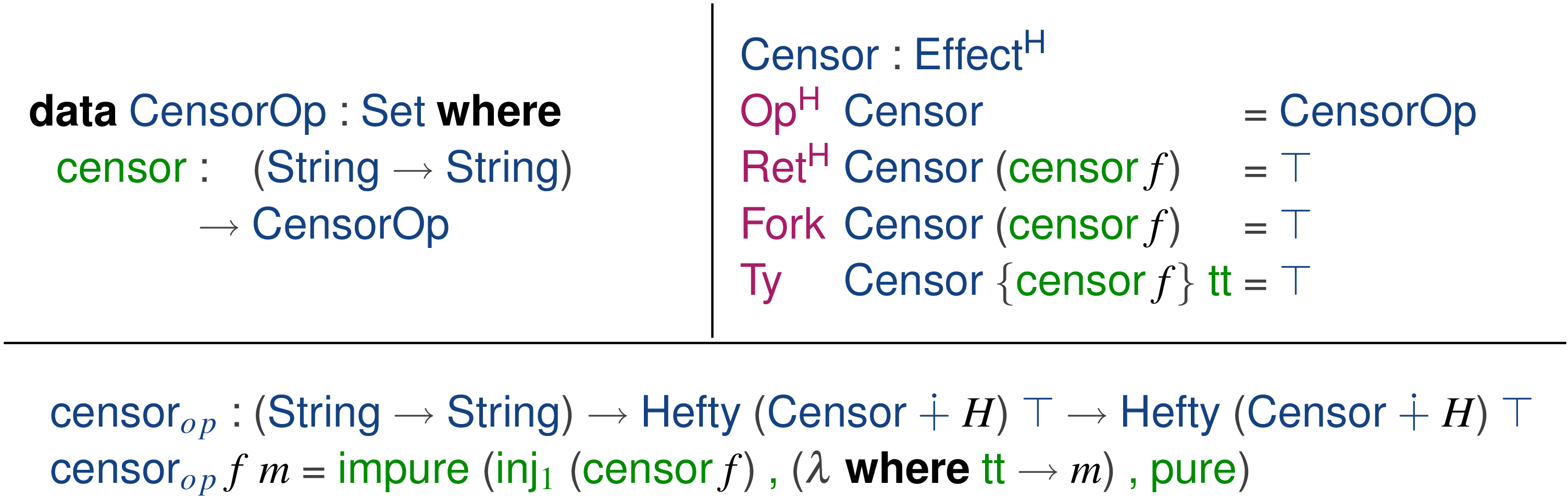

Nevertheless, for applications where it is known exactly which effects v contains, we can work around the issue by encoding computations as argument values of operations. We consider how and discuss the modularity problems that this workaround suffers from. The following

![]() ${Censor}$

effect declares the type of an operation

${Censor}$

effect declares the type of an operation

![]() ${censorOp}~(f,m)$

where f is a censoring function and m is a computation encoded as a value argument:Footnote

6

${censorOp}~(f,m)$

where f is a censoring function and m is a computation encoded as a value argument:Footnote

6

This effect can be handled as follows:

The handler case for

![]() ${censorOp}$

runs m with handlers for both the

${censorOp}$

runs m with handlers for both the

![]() ${Output}$

and

${Output}$

and

![]() ${Censor}$

effects, which yields a pair (x,s) where x represents the value returned by m, and s represents the (possibly sub-censored) output of m. We then output the result of applying the censoring function f to s, before passing x to the continuation k.

${Censor}$

effects, which yields a pair (x,s) where x represents the value returned by m, and s represents the (possibly sub-censored) output of m. We then output the result of applying the censoring function f to s, before passing x to the continuation k.

This handler lets us run programs such as the following:

Applying

![]() ${hCensor}$

and

${hCensor}$

and

![]() ${hOut}$

yields the printed output “Hello world!”, because

${hOut}$

yields the printed output “Hello world!”, because

:

As the example above illustrates, it is sometimes possible to encode higher-order effects as algebraic operations. However, encoding higher-order operations in this way suffers from a modularity problem. Say we want to extend our program with a new effect for throwing exceptions—i.e., an effect with a single operation

![]() ${throw}$

—and a new effect for catching exceptions—i.e., an effect with a single operation

${throw}$

—and a new effect for catching exceptions—i.e., an effect with a single operation

![]() ${catch}~m_1~m_2$

where exceptions thrown by

${catch}~m_1~m_2$

where exceptions thrown by

![]() $m_1$

are handled by running

$m_1$

are handled by running

![]() $m_2$

. The

$m_2$

. The

![]() ${Throw}$

effect is a plain algebraic effect, defined as follows.Footnote

7

${Throw}$

effect is a plain algebraic effect, defined as follows.Footnote

7

The

![]() ${Catch}$

effect is higher-order. We can again encode it as an operation with computations as value arguments.

${Catch}$

effect is higher-order. We can again encode it as an operation with computations as value arguments.

To support subcomputations with exception catching, we need to refine the computation type we use for

![]() ${Censor}$

. (This refinement could have been done modularly if we had used a more polymorphic type.)

${Censor}$

. (This refinement could have been done modularly if we had used a more polymorphic type.)

The modularity problem arises when we consider whether to handle

![]() ${Catch}$

or

${Catch}$

or

![]() ${Censor}$

first. If we handle

${Censor}$

first. If we handle

![]() ${Censor}$

first, then we get exactly the problem described earlier in connection with the law (†): the handler

${Censor}$

first, then we get exactly the problem described earlier in connection with the law (†): the handler

![]() ${hCensor}$

is not applied to sub-computations of

${hCensor}$

is not applied to sub-computations of

![]() ${catchOp}$

operations. Let us consider the consequences of this. Say we want to define a handler for

${catchOp}$

operations. Let us consider the consequences of this. Say we want to define a handler for

![]() ${catchOp}$

of the following type:

${catchOp}$

of the following type:

Any such handler which runs the sub-computation

![]() $m_1$

of an operation

$m_1$

of an operation

![]() ${catchOp}~m_1~m_2$

must hardcode a handler for the

${catchOp}~m_1~m_2$

must hardcode a handler for the

![]() ${Censor}$

effect. Otherwise the handler would allow effects to escape in a way that breaks the typing discipline of algebraic effects and handlers (Pretnar, Reference Pretnar2015). To illustrate why this is the case, consider the following program.

${Censor}$

effect. Otherwise the handler would allow effects to escape in a way that breaks the typing discipline of algebraic effects and handlers (Pretnar, Reference Pretnar2015). To illustrate why this is the case, consider the following program.

Per equation 12 of Pretnar (Reference Pretnar2015, Figure 7), this program is equivalent to:

Which means that

![]() ${hCatch}$

is now responsible for handling the remaining

${hCatch}$

is now responsible for handling the remaining

![]() ${Censor}$

effect in the first sub-computation of

${Censor}$

effect in the first sub-computation of

![]() ${catchOp}$

, otherwise it violates the promise of its type that the resulting computation does not have the

${catchOp}$

, otherwise it violates the promise of its type that the resulting computation does not have the

![]() ${Censor}$

effect. While for some applications it may be acceptable to hardcode handler invokations this way, it is non-modular and should not be—and, indeed, is not–necessary.

${Censor}$

effect. While for some applications it may be acceptable to hardcode handler invokations this way, it is non-modular and should not be—and, indeed, is not–necessary.

Before showing the solution, we propose which avoids this, we first consider a different workaround (Section 1.2.3) and previous solutions proposed in the literature (Section 1.2.4).

1.2.3 Potential workaround: Define higher-order operations as handlers

It is possible to define many higher-order operations in terms of algebraic effects and handlers. For example, instead of defining

![]() ${censor}$

as an operation, we could define it as a function which uses an inline handler application of

${censor}$

as an operation, we could define it as a function which uses an inline handler application of

![]() ${hOut}$

:

${hOut}$

:

Defining higher-order operations in terms of standard algebraic effects and handlers in this way is a key use case of effect handlers (Plotkin & Pretnar, Reference Plotkin and Pretnar2009). In fact, all other higher-order operations above (with the exception of function abstraction) can be defined in a similar manner.

However, it is unclear what the semantics is of composing syntax, equational theories, and proofs of programs with such functions occuring inline in programs. We address this gap by proposing notions of syntax and equational theories for programs with higher-order operations. The semantics of such programs and theories is given by elaborating them into standard algebraic effects and handlers.

1.2.4 Previous approaches to solving the modularity problem

The modularity problem of higher-order effects, summarized in Section 1.2.1, was first observed by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014) who proposed scoped effects and handlers (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014; Piróg et al., Reference Piróg, Schrijvers, Wu and Jaskelioff2018; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022) as a solution. Scoped effects and handlers work for a wide class of effects, including many higher-order effects, providing similar modularity benefits as algebraic effects and handlers when writing programs. Using parameterized algebraic theories (Lindley et al., Reference Lindley, Matache, Moss, Staton, Wu and Yang2024; Matache et al., Reference Matache, Lindley, Moss, Staton, Wu and Yang2025), it is possible reason about programs with scoped effects independently of how their effects are implemented.

Van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Schrijvers, Poulsen and Wu2021) recently observed, however, that operations that defer computation, such as evaluation strategies for

![]() $\lambda$

application or (multi-)staging (Taha & Sheard, Reference Taha and Sheard2000), are beyond the expressiveness of scoped effects. Therefore, van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Schrijvers, Poulsen and Wu2021) introduced another flavor of effects and handlers that they call latent effects and handlers. It remains an open question how to reason about latent effects and handlers independently of how effects are implemented.

$\lambda$

application or (multi-)staging (Taha & Sheard, Reference Taha and Sheard2000), are beyond the expressiveness of scoped effects. Therefore, van den Berg et al. (Reference van den Berg, Schrijvers, Poulsen and Wu2021) introduced another flavor of effects and handlers that they call latent effects and handlers. It remains an open question how to reason about latent effects and handlers independently of how effects are implemented.

In this paper, we demonstrate that an overloading-based approach provides a semantics of composition for effect theories that is comparable to standard algebraic effects and handlers, and, we expect, to parameterized algebraic theories. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the approach lets us model the syntax and semantics of key examples from the literature: optionally transactional exception catching, akin to scoped effect handlers (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014), and evaluation strategies for effectful

![]() $\lambda$

application (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Schrijvers, Poulsen and Wu2021). Formally relating the expressiveness of our approach with, e.g., scoped effects and parameterized algebraic theories, is future work.

$\lambda$

application (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Schrijvers, Poulsen and Wu2021). Formally relating the expressiveness of our approach with, e.g., scoped effects and parameterized algebraic theories, is future work.

1.3 Solution: Elaboration algebras

We propose to define operations such as

![]() ${censor}$

from Section 1.2 as modular elaborations from a syntax of higher-order effects into algebraic effects and handlers. To this end, we introduce a new type of computations with higher-order effects, which can be modularly translated into computations with only standard algebraic effects:

${censor}$

from Section 1.2 as modular elaborations from a syntax of higher-order effects into algebraic effects and handlers. To this end, we introduce a new type of computations with higher-order effects, which can be modularly translated into computations with only standard algebraic effects:

Here

![]() ${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H}$

is a computation type where A is a return type and H is a row comprising both algebraic and higher-order effects. The key idea is that the higher-order effects in the row H are modularly elaborated into a computation with effects given by the row

${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H}$

is a computation type where A is a return type and H is a row comprising both algebraic and higher-order effects. The key idea is that the higher-order effects in the row H are modularly elaborated into a computation with effects given by the row

![]() $\Delta$

. To achieve this, we define

$\Delta$

. To achieve this, we define

![]() ${elaborate}$

such that it can be modularly composed from separately defined elaboration cases, called elaboration algebras (for reasons explained in Section 3).

${elaborate}$

such that it can be modularly composed from separately defined elaboration cases, called elaboration algebras (for reasons explained in Section 3).

![]() ${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H} \Rrightarrow {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

as the type of elaboration algebras that elaborate the higher-order effects in H to

${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H} \Rrightarrow {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

as the type of elaboration algebras that elaborate the higher-order effects in H to

![]() $\Delta$

, we can modularly compose any pair of elaboration algebras

$\Delta$

, we can modularly compose any pair of elaboration algebras

![]() $e_1 : {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{{H_1}} \Rrightarrow{} {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

and

$e_1 : {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{{H_1}} \Rrightarrow{} {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

and

![]() $e_2 : {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{{H_2}} \Rrightarrow{} {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

into an algebra

$e_2 : {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{{H_2}} \Rrightarrow{} {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

into an algebra

![]() $e_{12} : {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{{H_1,H_2}} \Rrightarrow{} {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

.Footnote

8

$e_{12} : {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{{H_1,H_2}} \Rrightarrow{} {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

.Footnote

8

Elaboration algebras are as simple to define as non-modular elaborations such as

![]() ${censor}$

(Section 1.2.3). For example, here is the elaboration algebra for the higher-order

${censor}$

(Section 1.2.3). For example, here is the elaboration algebra for the higher-order

![]() ${Censor}$

effect whose only associated operation is the higher-order operation

${Censor}$

effect whose only associated operation is the higher-order operation

![]() ${censor_{op}} : ({String} \to {String}) \to {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H} \to {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H}$

:

${censor_{op}} : ({String} \to {String}) \to {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H} \to {A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H}$

:

The implementation of

![]() ${eCensor}$

is essentially the same as

${eCensor}$

is essentially the same as

![]() ${censor}$

, with two main differences. First, elaboration happens in-context, so the value yielded by the elaboration is passed to the context (or continuation) k. Second, and most importantly, programs that use the

${censor}$

, with two main differences. First, elaboration happens in-context, so the value yielded by the elaboration is passed to the context (or continuation) k. Second, and most importantly, programs that use the

![]() ${censor_{op}}$

operation are now programmed against the interface given by

${censor_{op}}$

operation are now programmed against the interface given by

![]() ${Censor}$

, meaning programs do not (and cannot) make assumptions about how

${Censor}$

, meaning programs do not (and cannot) make assumptions about how

![]() ${censor_{op}}$

is elaborated. As a consequence, we can modularly refine the elaboration of higher-order operations such as

${censor_{op}}$

is elaborated. As a consequence, we can modularly refine the elaboration of higher-order operations such as

![]() ${censor_{op}}$

, without modifying the programs that use the operations. Similarly, we can define equational theories that constrain the behavior elaborations of higher-order operations and write proofs about programs using higher-order operations that are valid for any elaboration that satisfies these equations.

${censor_{op}}$

, without modifying the programs that use the operations. Similarly, we can define equational theories that constrain the behavior elaborations of higher-order operations and write proofs about programs using higher-order operations that are valid for any elaboration that satisfies these equations.

For example, here is again a program which censors and replaces “Hello” with “Goodbye”:Footnote 9

Say we have a handler

![]() ${hOut^\prime} : ({String} \to {String}) \to {A}\mathop{!}{{Output},\Delta} \Rightarrow {(A \times {String})}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

which handles each operation

${hOut^\prime} : ({String} \to {String}) \to {A}\mathop{!}{{Output},\Delta} \Rightarrow {(A \times {String})}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

which handles each operation

![]() ${out}~s$

by pre-applying a censor function (

${out}~s$

by pre-applying a censor function (

![]() ${String} \to {String}$

) to s before emitting it. Using this handler, we can give an alternative elaboration of

${String} \to {String}$

) to s before emitting it. Using this handler, we can give an alternative elaboration of

![]() ${censor_{op}}$

which post-processes output strings individually:

${censor_{op}}$

which post-processes output strings individually:

In contrast,

![]() ${eCensor}$

applies the censoring function (

${eCensor}$

applies the censoring function (

![]() ${String} \to {String}$

) to the batch output of the computation argument of a

${String} \to {String}$

) to the batch output of the computation argument of a

![]() ${censor_{op}}$

operation. The batch output of

${censor_{op}}$

operation. The batch output of

![]() ${hello}$

is “Hello world!” which is unequal to “Hello”, so

${hello}$

is “Hello world!” which is unequal to “Hello”, so

![]() ${eCensor}$

leaves the string unchanged. On the other hand,

${eCensor}$

leaves the string unchanged. On the other hand,

![]() ${eCensor^\prime}$

censors the individually output “Hello”:

${eCensor^\prime}$

censors the individually output “Hello”:

This gives higher-order operations the same modularity benefits as algebraic operations for defining programs. In Section 5, we show that these modularity benefits extend to program reasoning as well.

1.4 Contributions

This paper formalizes the ideas sketched in this introduction by shallowly embedding them in Agda. However, the ideas transcend Agda. Similar shallow embeddings can be implemented in other dependently typed languages, such as Idris (Reference BradyBrady, 2013a ); but also in less dependently typed languages like Haskell, OCaml, or Scala.Footnote 10 By working in a dependently typed language, we can state algebraic laws about interfaces of effectful operations, and prove that implementations of the interfaces respect the laws. We make the following technical contributions:

-

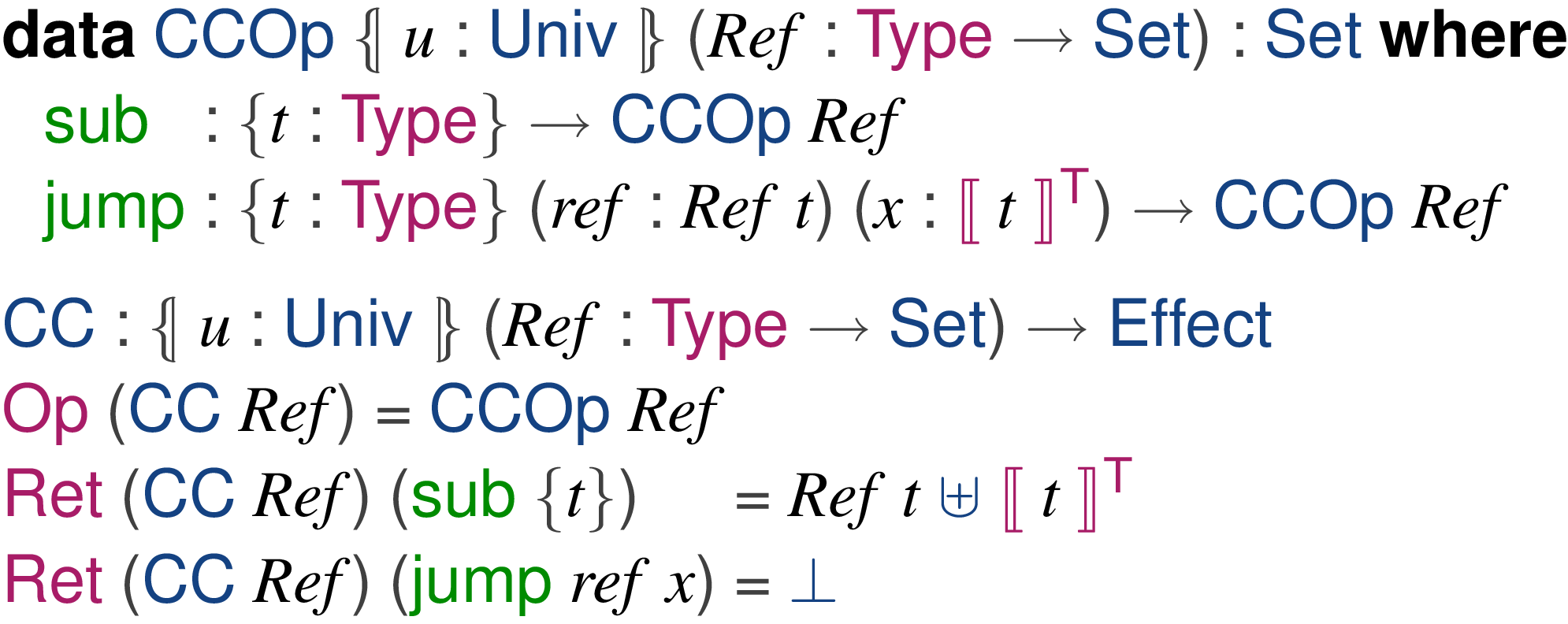

• Section 2 describes how to encode algebraic effects in Agda, revisits the modularity problem with higher-order operations, and summarizes how scoped effects and handlers address the modularity problem, for some (scoped operations) but not all higher-order operations.

-

• Section 3 presents our solution to the modularity problem with higher-order operations. Our solution is to (1) type programs as higher-order effect trees (which we dub hefty trees) and (2) build modular elaboration algebras for folding hefty trees into algebraic effect trees and handlers. The computations of type

${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H}$

discussed in Section 1.3 correspond to hefty trees, and the elaborations of type

${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H}$

discussed in Section 1.3 correspond to hefty trees, and the elaborations of type

${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H} \Rrightarrow {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

correspond to hefty algebras.

${A}\mathop{!\kern-1pt!}{H} \Rrightarrow {A}\mathop{!}{\Delta}$

correspond to hefty algebras. -

• Section 4 presents examples of how to define hefty algebras for common higher-order effects from the literature on effect handlers.

-

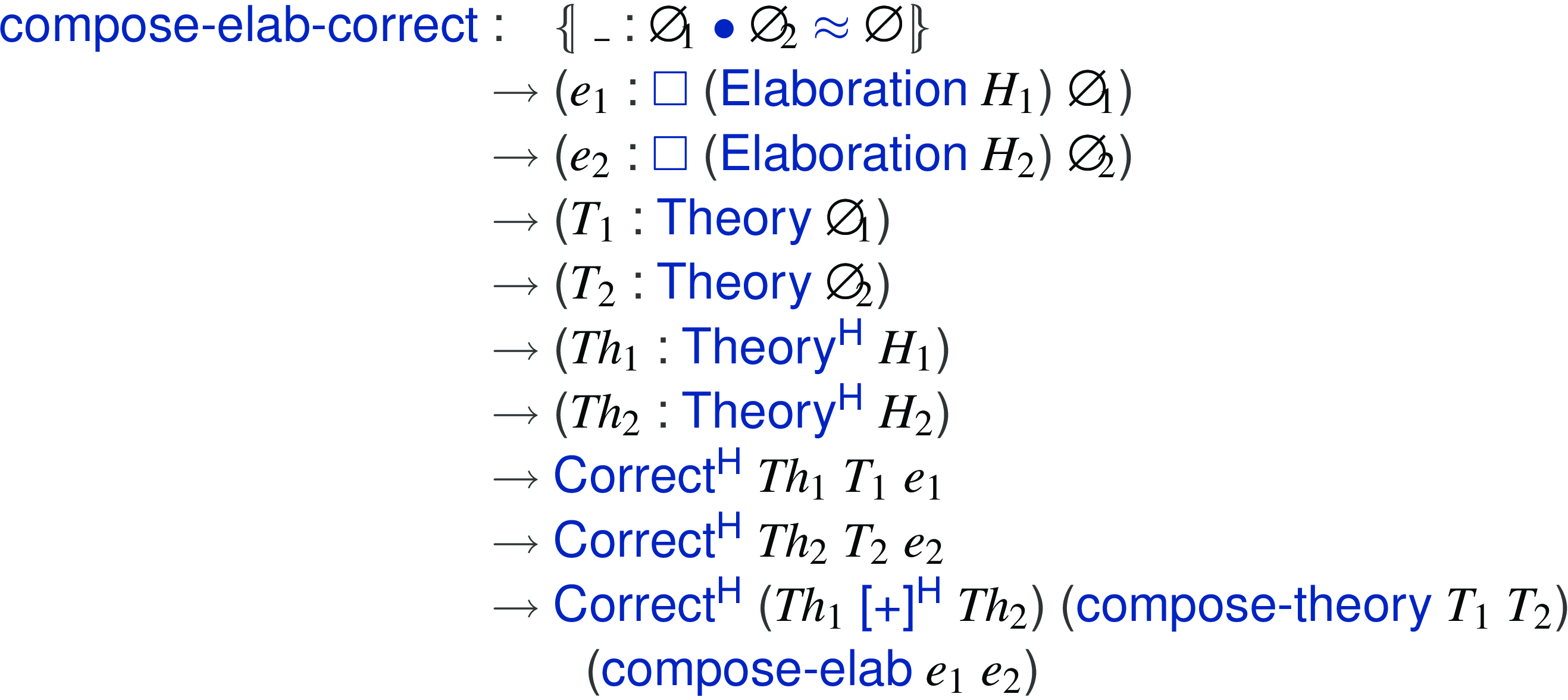

• Section 5 shows that hefty algebras support formal and modular reasoning on a par with algebraic effects and handlers, by developing reasoning infrastructure that supports verification of equational laws for higher-order effects such as exception catching. Crucially, proofs of correctness of elaborations are compositional. When composing two proven correct elaboration, correctness of the combined elaboration follows immediately without requiring further proof work.

Section 6 discusses related work and Section 7 concludes. The paper assumes a passing familiarity with dependent types. We do not assume familiarity with Agda: we explain Agda-specific syntax and features when we use them.

An artifact containing the code of the paper and a Haskell embedding of the same ideas is available online (van der Rest & Poulsen, Reference van der Rest and Poulsen2024). A subset of the contributions of this paper was previously published in a conference paper (Poulsen & van der Rest, Reference Poulsen and van der Rest2023). While that version of the paper too discusses reasoning about higher-order effects, the correctness proofs were non-modular, in that they make assumptions about the order in which the algebraic effects implementing a higher-order effect are handled. When combining elaborations, these assumptions are often incompatible, meaning that correctness proofs for the individual elaborations do not transfer to the combined elaboration. As a result, one would have to re-prove correctness for every combination of elaborations. For this extended version, we developed reasoning infrastructure to support modular reasoning about higher-order effects in Section 5 and proved that correctness of elaborations is preserved under composition of elaborations.

2 Algebraic effects and handlers in Agda

This section describes how to encode algebraic effects and handlers in Agda. We do not assume familiarity with Agda and explain Agda specific notation in footnotes. Sections 2.1 to 2.4 defines algebraic effects and handlers; Section 2.5 revisits the problem of defining higher-order effects using algebraic effects and handlers; and Section 2.6 discusses how scoped effects (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014; Piróg et al., Reference Piróg, Schrijvers, Wu and Jaskelioff2018; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022) solves the problem for scoped operations but not all higher-order operations.

2.1 Algebraic effects and the free monad

We encode algebraic effects in Agda by representing computations as an abstract syntax tree given by the free monad over an effect signature. Such effect signatures are traditionally (Swierstra, Reference Swierstra2008; Awodey, Reference Awodey2010; Kammar et al., Reference Kammar, Lindley and Oury2013; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014; Kiselyov & Ishii, Reference Kiselyov and Ishii2015) given by a functor; i.e., a type of kind

![]() together with a (lawful) mapping function.Footnote

11

In our Agda implementation, effect signature functors are defined by giving a container (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Altenkirch and Ghani2003, Reference Abbott, Altenkirch and Ghani2005). Each container corresponds to a value of type

together with a (lawful) mapping function.Footnote

11

In our Agda implementation, effect signature functors are defined by giving a container (Abbott et al., Reference Abbott, Altenkirch and Ghani2003, Reference Abbott, Altenkirch and Ghani2005). Each container corresponds to a value of type

![]() that is both strictly positive

Footnote

12

and universe consistent

Footnote

13

(Martin-Löf, Reference Martin-Löf1984), meaning they are a constructive approximation of endofunctors on

that is both strictly positive

Footnote

12

and universe consistent

Footnote

13

(Martin-Löf, Reference Martin-Löf1984), meaning they are a constructive approximation of endofunctors on

![]() . Effect signatures are given by a (dependent) record type:

Footnote 14,Footnote 15

. Effect signatures are given by a (dependent) record type:

Footnote 14,Footnote 15

Here,

![]() is the set of operations, and

is the set of operations, and

![]() defines the return type for each operation in the set

defines the return type for each operation in the set

![]() . The extension of an effect signature,

. The extension of an effect signature,

![]() $[\![\_]\!]$

, reflects its input of type

$[\![\_]\!]$

, reflects its input of type

![]() as a value of type

as a value of type

![]() :Footnote

16

:Footnote

16

The extension of an effect

![]() $\Delta$

into

$\Delta$

into

![]() is indeed a functor, as witnessed by the following function:Footnote

17

is indeed a functor, as witnessed by the following function:Footnote

17

As discussed in the introduction, computations may use multiple different effects. Effect signatures are closed under co-products:Footnote 18 ,Footnote 19

We compute the co-product of two effect signatures by taking the disjoint sum of their operations and combining the return type mappings pointwise. We use co-products to encode effect rows. For example, the effect

![]() corresponds to the row union denoted as

corresponds to the row union denoted as

![]() $\Delta_{1},\Delta_{2}$

in the introduction.

$\Delta_{1},\Delta_{2}$

in the introduction.

The syntax of computations with effects

![]() $\Delta$

is given by the free monad over

$\Delta$

is given by the free monad over

![]() $\Delta$

. We encode the free monad as follows:

$\Delta$

. We encode the free monad as follows:

Here,

![]() is a computation with no side-effects, whereas

is a computation with no side-effects, whereas

![]() is an operation whose syntax is given by the functor

is an operation whose syntax is given by the functor

![]() . By applying this functor to

. By applying this functor to

![]() , we encode an operation whose continuation may contain more effectful operations.Footnote

20

To see in what sense, let us consider an example.

, we encode an operation whose continuation may contain more effectful operations.Footnote

20

To see in what sense, let us consider an example.

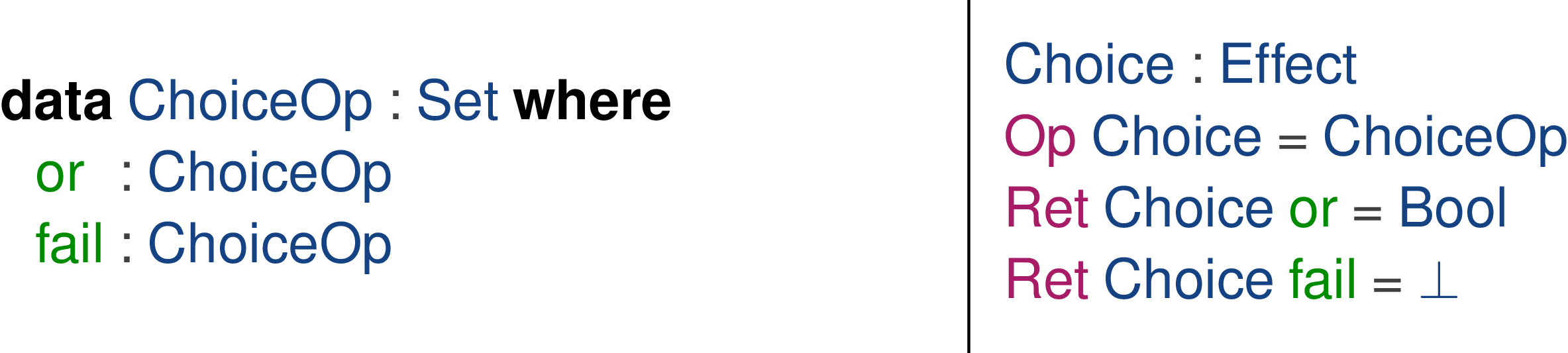

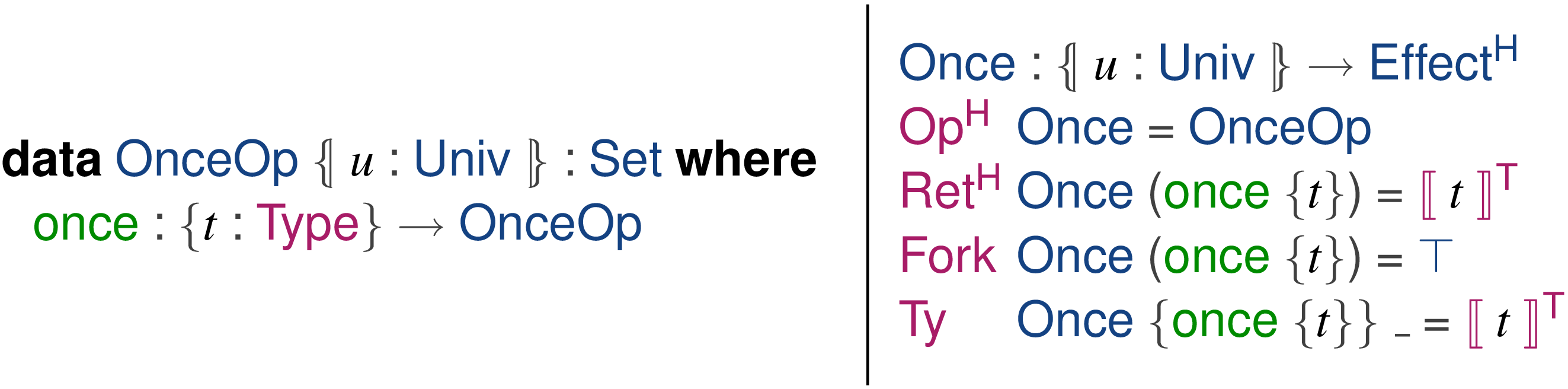

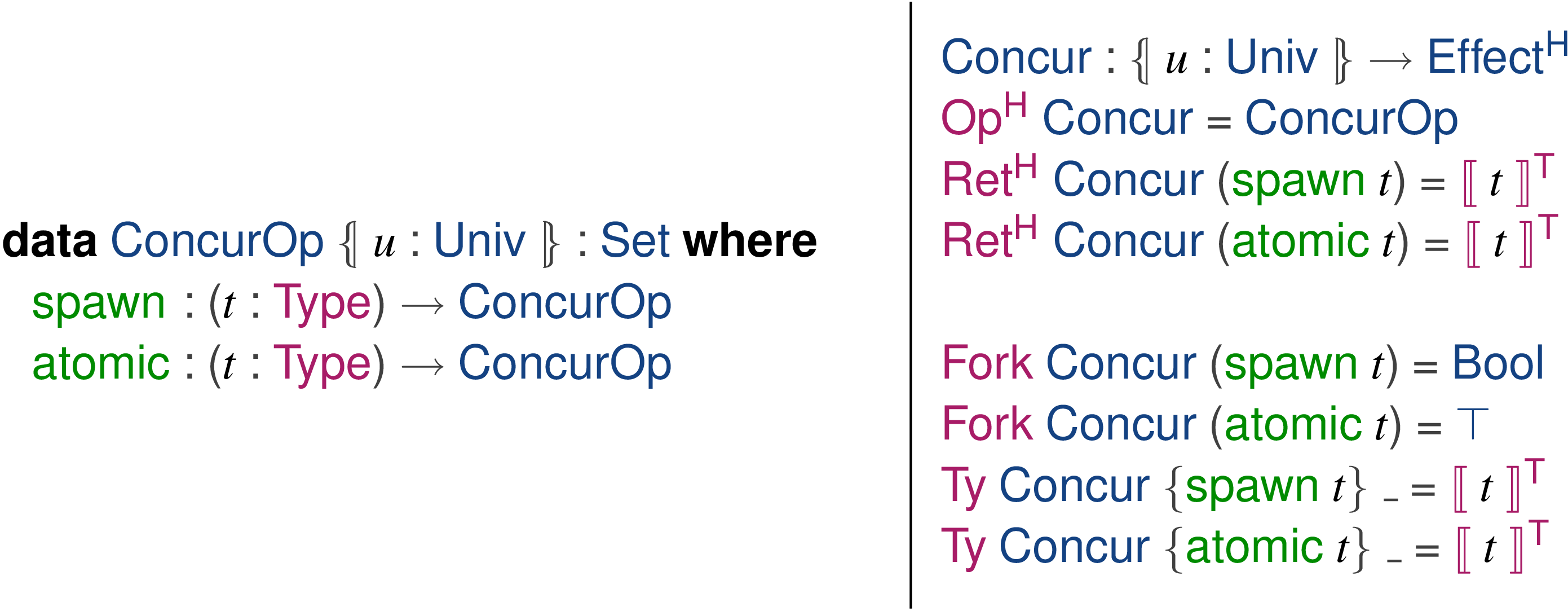

Example. The data type on the left below defines an operation for outputting a string. On the right is its corresponding effect signature.

The effect signature on the right says that

![]() returns a unit value (

returns a unit value (

![]() is the unit type). Using this, we can write a simple hello world corresponding to the

is the unit type). Using this, we can write a simple hello world corresponding to the

![]() ${hello}$

program from Section 1:

${hello}$

program from Section 1:

Section 2.1 shows how to make this program more readable by using monadic

![]() notation.

notation.

The

![]() program above makes use of just a single effect. Say we want to use another effect,

program above makes use of just a single effect. Say we want to use another effect,

![]() , with a single operation,

, with a single operation,

![]() , which represents throwing an exception (therefore having the empty type

, which represents throwing an exception (therefore having the empty type

![]() as its return type):

as its return type):

Programs that use multiple effects, such as

![]() and

and

![]() , are unnecessarily verbose. For example, consider the following program which prints two strings before throwing an exception:Footnote

21

, are unnecessarily verbose. For example, consider the following program which prints two strings before throwing an exception:Footnote

21

To reduce syntactic overhead, we use row insertions and smart constructors (Swierstra, Reference Swierstra2008).

2.2 Row insertions and smart constructors

A smart constructor constructs an effectful computation comprising a single operation. The type of this computation is polymorphic in what other effects the computation has. For example, the type of a smart constructor for the

![]() effect is

effect is

Here, the

![]() type declares the row insertion witness as an instance argument of

type declares the row insertion witness as an instance argument of

![]() . Instance arguments in Agda are conceptually similar to type class constraints in Haskell: when we call

. Instance arguments in Agda are conceptually similar to type class constraints in Haskell: when we call

![]() , Agda will attempt to automatically find a witness of the right type, and implicitly pass this as an argument.Footnote

22

Thus, calling

, Agda will attempt to automatically find a witness of the right type, and implicitly pass this as an argument.Footnote

22

Thus, calling

![]() will automatically inject the

will automatically inject the

![]() effect into some larger effect row

effect into some larger effect row

![]() $\Delta$

.

$\Delta$

.

We define the

![]() order on effect rows in terms of a different

order on effect rows in terms of a different

![]() which witnesses that any operation of

which witnesses that any operation of

![]() $\Delta$

is isomorphic to either an operation of

$\Delta$

is isomorphic to either an operation of

![]() $\Delta_{1}$

or an operation of

$\Delta_{1}$

or an operation of

![]() $\Delta_{2}$

:Footnote

23

,Footnote

24

$\Delta_{2}$

:Footnote

23

,Footnote

24

Using this, the

![]() order is defined as follows:

order is defined as follows:

It is straightforward to show that

![]() is a preorder; i.e., that it is a reflexive and transitive relation.

is a preorder; i.e., that it is a reflexive and transitive relation.

We can also define the following function, which uses a

![]() $\Delta_{1}$

$\Delta_{1}$

![]()

![]() $\Delta_{2}$

witness to coerce an operation of effect type

$\Delta_{2}$

witness to coerce an operation of effect type

![]() $\Delta_{1}$

into an operation of some larger effect type

$\Delta_{1}$

into an operation of some larger effect type

![]() $\Delta_{2}$

.Footnote

25

$\Delta_{2}$

.Footnote

25

Furthermore, we can freely coerce the operations of a computation from one effect row to a different effect row:Footnote 26 ,Footnote 27

Using this infrastructure, we can now implement a generic

![]() function which lets us define smart constructors for operations such as the

function which lets us define smart constructors for operations such as the

![]() operation discussed in the previous subsection.

operation discussed in the previous subsection.

2.3 Fold and monadic bind for

Since

![]() is a monad, we can sequence computations using monadic bind, which is naturally defined in terms of the fold over

is a monad, we can sequence computations using monadic bind, which is naturally defined in terms of the fold over

![]() .

.

Besides the input computation to be folded (last parameter), the fold is parameterized by a function

![]() (first parameter) which folds a

(first parameter) which folds a

![]() computation, and an algebra

computation, and an algebra

![]()

![]() $\Delta$

A (second parameter) which folds an

$\Delta$

A (second parameter) which folds an

![]() computation. We call the latter an algebra because it corresponds to an F-algebra (Arbib & Manes, Reference Arbib and Manes1975; Pierce, Reference Pierce1991) over the signature functor of

computation. We call the latter an algebra because it corresponds to an F-algebra (Arbib & Manes, Reference Arbib and Manes1975; Pierce, Reference Pierce1991) over the signature functor of

![]() , denoted

, denoted

![]() $F_{\Delta}$

. That is, a tuple

$F_{\Delta}$

. That is, a tuple

![]() $(A, \alpha)$

where A is an object called the carrier of the algebra, and

$(A, \alpha)$

where A is an object called the carrier of the algebra, and

![]() $\alpha$

a morphism

$\alpha$

a morphism

![]() $F_{\Delta}(A) \to A$

. Using

$F_{\Delta}(A) \to A$

. Using

![]() , monadic bind for the free monad is defined as follows:

, monadic bind for the free monad is defined as follows:

Intuitively,

![]() concatenates g to all the leaves in the computation m.

concatenates g to all the leaves in the computation m.

Example. The following defines a smart constructor for

![]() :

:

Using this and the definition of

![]() above, we can use do-notation in Agda to make the

above, we can use do-notation in Agda to make the

![]() program from Section 2.1 more readable:

program from Section 2.1 more readable:

This illustrates how we use the free monad to write effectful programs against an interface given by an effect signature. Next, we define effect handlers.

2.4 Effect handlers

An effect handler implements the interface given by an effect signature, interpreting the syntactic operations associated with an effect. Like monadic bind, effect handlers can be defined as a fold over the free monad. The following type of parameterized handlers (Leijen, Reference Leijen2017, §2.2) defines how to fold, respectively,

![]() and

and

![]() computations:Footnote

28

computations:Footnote

28

A handler of type

![]() is parameterized in the sense that it turns a computation of type

is parameterized in the sense that it turns a computation of type

![]() into a parameterized computation of type

into a parameterized computation of type

![]() . The following function does so by folding using

. The following function does so by folding using

![]() , and a

, and a

![]() function:Footnote

29

function:Footnote

29

Comparing with the syntax, we used to explain algebraic effects and handlers in the introduction, the

![]() field corresponds to the

field corresponds to the

![]() $\mathbf{return}{}$

case of the handlers from the introduction, and

$\mathbf{return}{}$

case of the handlers from the introduction, and

![]() corresponds to the cases that define how operations are handled. The parameterized handler type

corresponds to the cases that define how operations are handled. The parameterized handler type

![]() corresponds to the type

corresponds to the type

![]() ${A}\mathop{!}{\Delta,\Delta^\prime} \Rightarrow P \to {B}\mathop{!}{\Delta^\prime}$

, and

${A}\mathop{!}{\Delta,\Delta^\prime} \Rightarrow P \to {B}\mathop{!}{\Delta^\prime}$

, and

![]() h

h

![]() m corresponds to

m corresponds to

![]() $\textbf{with}~{h}~\textbf{handle}~{m}$

.

$\textbf{with}~{h}~\textbf{handle}~{m}$

.

Using this type of handler, the

![]() ${hOut}$

handler from the introduction can be defined as follows:

${hOut}$

handler from the introduction can be defined as follows:

The handler

![]() ${hOut}$

in Section 1.1 did not bind any parameters. However, since we are encoding it as a parameterized handler,

${hOut}$

in Section 1.1 did not bind any parameters. However, since we are encoding it as a parameterized handler,

![]() now binds a unit-typed parameter. Besides this difference, the handler is the same as in Section 1.1. We can use the

now binds a unit-typed parameter. Besides this difference, the handler is the same as in Section 1.1. We can use the

![]() handler to run computations. To this end, we introduce a

handler to run computations. To this end, we introduce a

![]() effect with no associated operations which we will use to indicate where an effect row ends:

effect with no associated operations which we will use to indicate where an effect row ends:

Using these, we can run a simple hello world program:Footnote 30

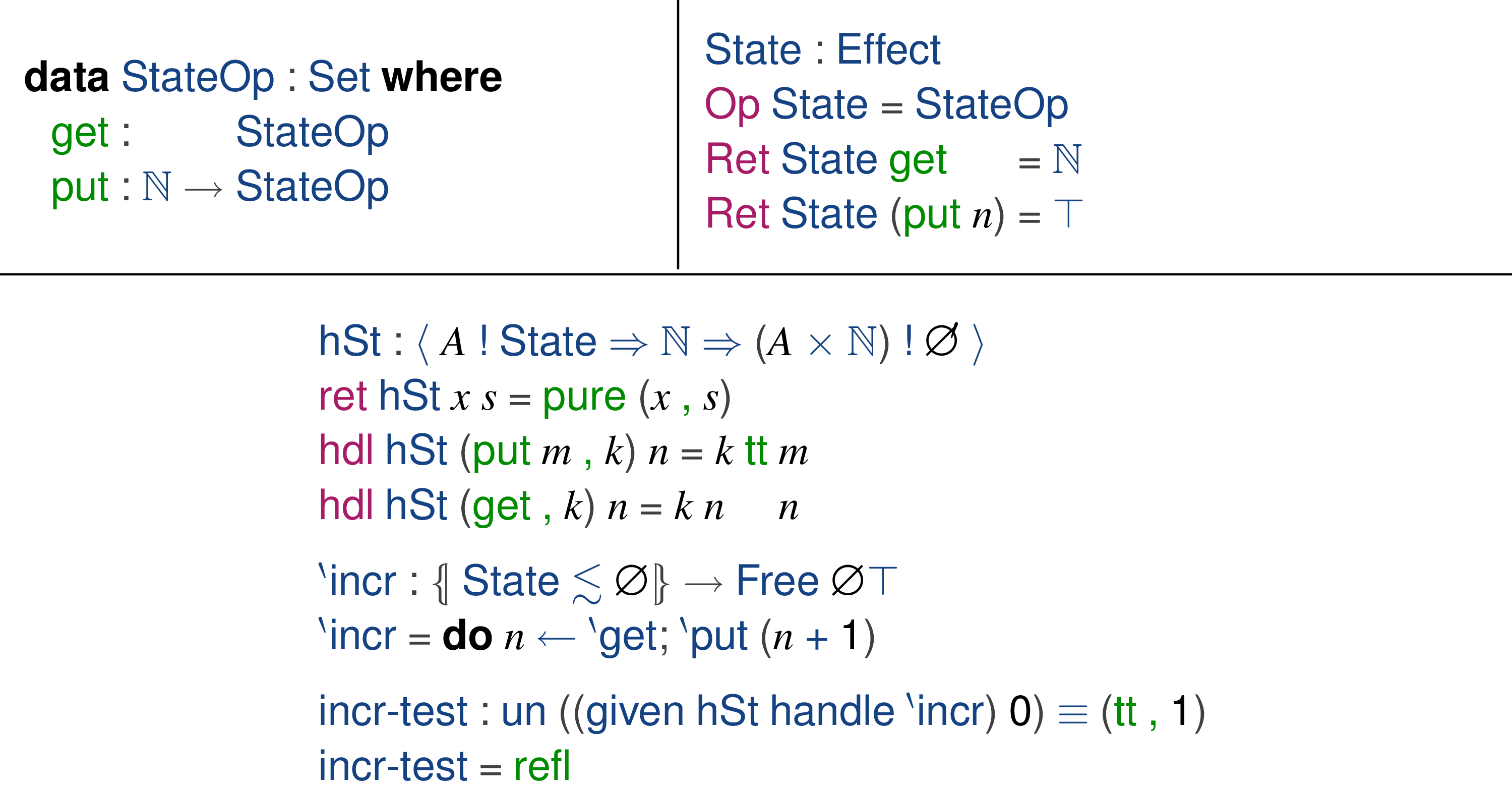

An example of parameterized (as opposed to unparameterized) handlers is the state effect. Figure 1 declares and illustrates how to handle such an effect with operations for reading (

![]() ) and changing (

) and changing (

![]() ) the state of a memory cell holding a natural number.

) the state of a memory cell holding a natural number.

Fig 1. A state effect (upper), its handler (

![]() below), and a simple test (

below), and a simple test (

![]() , also below) which uses (the elided) smart constructors for

, also below) which uses (the elided) smart constructors for

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

2.5 The modularity problem with higher-order effects, revisited

Section 1.2 described the modularity problem with higher-order effects, using a higher-order operation that interacts with output as an example. In this section, we revisit the problem, framing it in terms of the definitions introduced in the previous section. To this end, we use a different effect whose interface is summarized by the

![]() record below. The record asserts that the computation type M :

record below. The record asserts that the computation type M :

![]() has at least a higher-order operation

has at least a higher-order operation

![]() and a first-order operation

and a first-order operation

![]() :

:

The idea is that

![]() throws an exception, and

throws an exception, and

![]() m

m

![]() $_{1}$

m

$_{1}$

m

![]() $_{2}$

handles any exception thrown during evaluation of m

$_{2}$

handles any exception thrown during evaluation of m

![]() $_{1}$

by running m

$_{1}$

by running m

![]() $_{2}$

instead. The problem is that we cannot give a modular definition of operations such as

$_{2}$

instead. The problem is that we cannot give a modular definition of operations such as

![]() using algebraic effects and handlers alone. As discussed in Section 1.2, the crux of the problem is that algebraic effects and handlers provide limited support for higher-order operations. However, as also discussed in Section 1.2, we can encode

using algebraic effects and handlers alone. As discussed in Section 1.2, the crux of the problem is that algebraic effects and handlers provide limited support for higher-order operations. However, as also discussed in Section 1.2, we can encode

![]() in terms of more primitive effects and handlers, such as the following handler for the

in terms of more primitive effects and handlers, such as the following handler for the

![]() effect:

effect:

The handler modifies the return type of the computation by decorating it with a

![]() . If no exception is thrown,

. If no exception is thrown,

![]() wraps the yielded value in a

wraps the yielded value in a

![]() constructor. If an exception is thrown, the handler never invokes the continuation k and aborts the computation by returning

constructor. If an exception is thrown, the handler never invokes the continuation k and aborts the computation by returning

![]() instead. We can elaborate

instead. We can elaborate

![]() into an inline application of

into an inline application of

![]() . To do so, we make use of effect masking which lets us “weaken” the type of a computation by inserting extra effects in an effect row:

. To do so, we make use of effect masking which lets us “weaken” the type of a computation by inserting extra effects in an effect row:

Using this, the following elaboration defines a semantics for the

![]() operation:Footnote

31

,Footnote

32

operation:Footnote

31

,Footnote

32

If m

![]() $_{1}$

does not throw an exception, we return the produced value. If it does, m

$_{1}$

does not throw an exception, we return the produced value. If it does, m

![]() $_{2}$

is run.

$_{2}$

is run.

As observed by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014), programs that use elaborations such as

![]() are less modular than programs that only use plain algebraic operations. In particular, the effect row of computations no longer represents the interface of operations that we use to write programs, since the

are less modular than programs that only use plain algebraic operations. In particular, the effect row of computations no longer represents the interface of operations that we use to write programs, since the

![]() elaboration is not represented in the effect type at all. So we have to rely on different machinery if we want to refactor, optimize, or change the semantics of

elaboration is not represented in the effect type at all. So we have to rely on different machinery if we want to refactor, optimize, or change the semantics of

![]() without having to change programs that use it.

without having to change programs that use it.

In the next subsection, we describe how to define effectful operations such as

![]() modularly using scoped effects and handlers and discuss how this is not possible for, e.g., operations representing

modularly using scoped effects and handlers and discuss how this is not possible for, e.g., operations representing

![]() $\lambda$

-abstraction.

$\lambda$

-abstraction.

2.6 Scoped effects and handlers

This subsection gives an overview of scoped effects and handlers. While the rest of the paper can be read and understood without a deep understanding of scoped effects and handlers, we include this overview to facilitate comparison with the alternative solution that we introduce in Section 3.

Scoped effects extend the expressiveness of algebraic effects to support a class of higher-order operations that Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014), Piróg et al. (Reference Piróg, Schrijvers, Wu and Jaskelioff2018), Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022) call scoped operations. We illustrate how scoped effects work, using a freer monad encoding of the endofunctor algebra approach of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022). The work of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022) does not include examples of modular handlers, but the original paper on scoped effects and handlers by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014) does. We describe an adaptation of the modular handling techniques due to Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014) to the endofunctor algebra approach of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022).

2.6.1 Scoped programs

Scoped effects extend the free monad data type with an additional row for scoped operations. The

![]() and

and

![]() constructors of

constructors of

![]() below correspond to the

below correspond to the

![]() and

and

![]() constructors of the free monad, whereas

constructors of the free monad, whereas

![]() is new:

is new:

Here, the

![]() constructor represents a higher-order operation with sub-scopes; i.e., computations that themselves return computations:

constructor represents a higher-order operation with sub-scopes; i.e., computations that themselves return computations:

This type represents scoped computations in the sense that outer computations can be handled independently of inner ones, as we illustrate in sec:scoped-effect-handlers. One way to think of inner computations is as continuations (or join-points) of sub-scopes.

Using

![]() , the catch operation can be defined as a scoped operation:

, the catch operation can be defined as a scoped operation:

The effect signature indicates that

![]() has two scopes since

has two scopes since

![]() has two inhabitants. Following Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022), scoped operations are handled using a structure-preserving fold over

has two inhabitants. Following Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Paviotti, Wu, van den Berg and Schrijvers2022), scoped operations are handled using a structure-preserving fold over

![]() :

:

The first argument represents the case where we are folding a

![]() node; the second and third correspond to, respectively,

node; the second and third correspond to, respectively,

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

2.6.2 Scoped effect handlers

The following defines a type of parameterized scoped effect handlers:

A handler of type

![]() handles operations of

handles operations of

![]() $\Delta$

and

$\Delta$

and

![]() $\gamma$

simultaneously and turns a computation

$\gamma$

simultaneously and turns a computation

![]() into a parameterized computation of type

into a parameterized computation of type

![]() . The

. The

![]() and

and

![]() cases are similar to the

cases are similar to the

![]() and

and

![]() cases from sec:effect-handlers. The crucial addition that adds support for higher-order operations is the

cases from sec:effect-handlers. The crucial addition that adds support for higher-order operations is the

![]() case.

case.

The

![]() field is given by an

field is given by an

![]() case. This case takes as input a scoped operation whose outer and inner computation have been folded into a parameterized computation of type

case. This case takes as input a scoped operation whose outer and inner computation have been folded into a parameterized computation of type

![]() and returns as output an interpretation of that operation as a computation of type

and returns as output an interpretation of that operation as a computation of type

![]() . The

. The

![]() function is used for modularly weaving (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014) side effects of handlers through sub-scopes of yet-unhandled operations.

function is used for modularly weaving (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Schrijvers and Hinze2014) side effects of handlers through sub-scopes of yet-unhandled operations.

2.6.3 Weaving

To see why

![]() is needed, it is instructional to look at how the fields in the record type above are used to fold over

is needed, it is instructional to look at how the fields in the record type above are used to fold over

![]() :

:

The second to last line above shows how

![]() is used. Because

is used. Because

![]() eagerly folds the current handler over scopes (sc), there is a mismatch between the type that the continuation expects (B) and the type that the scoped computation returns (G B). The

eagerly folds the current handler over scopes (sc), there is a mismatch between the type that the continuation expects (B) and the type that the scoped computation returns (G B). The

![]() function fixes this mismatch for the particular return type modification G :

function fixes this mismatch for the particular return type modification G :

![]() of a parameterized scoped effect handler.

of a parameterized scoped effect handler.

The scoped effect handler for exception catching is thus:

The

![]() field for the

field for the

![]() operation first runs m

operation first runs m

![]() $_{1}$

. If no exception is thrown, the value produced by m

$_{1}$

. If no exception is thrown, the value produced by m

![]() $_{1}$

is forwarded to k. Otherwise, m

$_{1}$

is forwarded to k. Otherwise, m

![]() $_{2}$

is run and its value is forwarded to k, or its exception is propagated. The

$_{2}$

is run and its value is forwarded to k, or its exception is propagated. The

![]() field of

field of

![]() says that, if an unhandled exception is thrown during evaluation of a scope, the continuation is discarded and the exception is propagated; and if no exception is thrown the continuation proceeds normally.

says that, if an unhandled exception is thrown during evaluation of a scope, the continuation is discarded and the exception is propagated; and if no exception is thrown the continuation proceeds normally.

2.6.4 Discussion and limitations

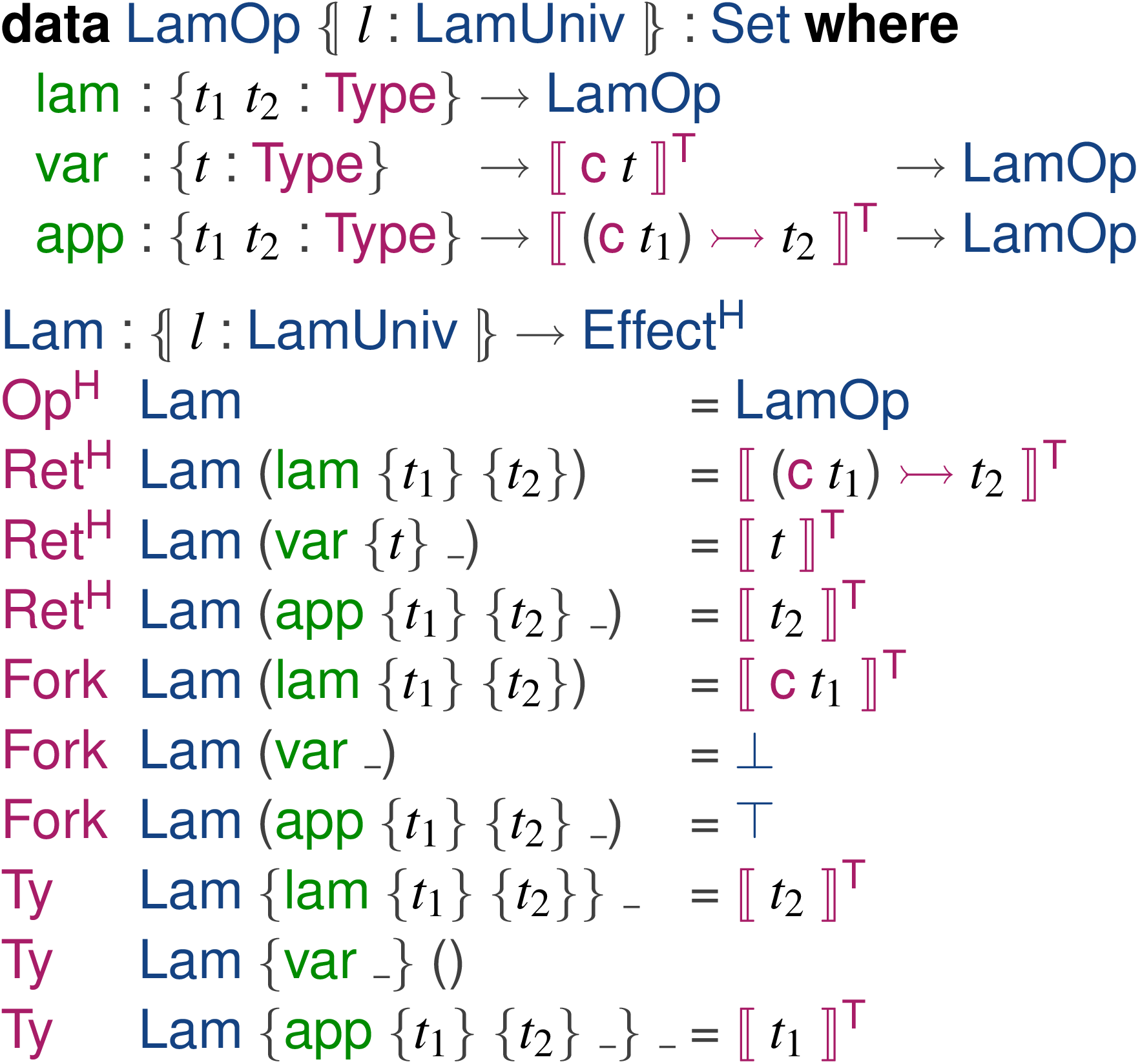

As observed by Berg et al. (2021), some higher-order effects do not correspond to scoped operations. In particular, the

![]() record shown below is not a scoped operation:

record shown below is not a scoped operation:

The

![]() field represents an operation that constructs a

field represents an operation that constructs a

![]() $\lambda$

value. The

$\lambda$

value. The

![]() field represents an operation that will apply the function value in the first parameter position to the argument computation in the second parameter position. The

field represents an operation that will apply the function value in the first parameter position to the argument computation in the second parameter position. The

![]() operation has a computation as its second parameter so that it remains compatible with different evaluation strategies.

operation has a computation as its second parameter so that it remains compatible with different evaluation strategies.

To see why the operations summarized by the

![]() record above are not scoped operations, let us revisit the

record above are not scoped operations, let us revisit the

![]() constructor of

constructor of

![]() :

:

As summarized earlier in this subsection,

![]() lets us represent higher-order operations (specifically, scoped operations), whereas

lets us represent higher-order operations (specifically, scoped operations), whereas

![]() does not (only algebraic operations). Just like we defined the computational parameters as scopes (given by the outer

does not (only algebraic operations). Just like we defined the computational parameters as scopes (given by the outer

![]() in the type of

in the type of

![]() ), we might try to define the body of a lambda as a scope in a similar way. However, whereas the

), we might try to define the body of a lambda as a scope in a similar way. However, whereas the

![]() operation always passes control to its continuation (the inner

operation always passes control to its continuation (the inner

![]() ), the

), the

![]() effect is supposed to package the body of the lambda into a value and pass this value to the continuation (the inner computation). Because the inner computation is nested within the outer computation, the only way to gain access to the inner computation (the continuation) is by first running the outer computation (the body of the lambda). This does not give us the right semantics.

effect is supposed to package the body of the lambda into a value and pass this value to the continuation (the inner computation). Because the inner computation is nested within the outer computation, the only way to gain access to the inner computation (the continuation) is by first running the outer computation (the body of the lambda). This does not give us the right semantics.

It is possible to elaborate the

![]() operations into more primitive effects and handlers, but as discussed in Sections 1.2 and 2.5, such elaborations are not modular. In the next section, we show how to make such elaborations modular.

operations into more primitive effects and handlers, but as discussed in Sections 1.2 and 2.5, such elaborations are not modular. In the next section, we show how to make such elaborations modular.

3 Hefty trees and algebras

As observed in Section 2.5, operations such as

![]() can be elaborated into more primitive effects and handlers. However, these elaborations are not modular. We solve this problem by factoring elaborations into interfaces of their own to make them modular.

can be elaborated into more primitive effects and handlers. However, these elaborations are not modular. We solve this problem by factoring elaborations into interfaces of their own to make them modular.

To this end, we first introduce a new type of abstract syntax trees (Sections 3.1–3.3) representing computations with higher-order operations, which we dub hefty trees (an acronymic pun on higher-order effects). We then define elaborations as algebras (hefty algebras; sec:hefty-algebras) over these trees. The following pipeline summarizes the idea, where H is a higher-order effect signature:

For the categorically inclined reader,

![]() conceptually corresponds to the initial algebra of the functor

conceptually corresponds to the initial algebra of the functor

![]() ${HeftyF}~H~A~R = A + H~R~(R~A)$

where

${HeftyF}~H~A~R = A + H~R~(R~A)$

where

![]() defines the signature of higher-order operations and is a higher-order functor, meaning we have both the usual functorial

defines the signature of higher-order operations and is a higher-order functor, meaning we have both the usual functorial

![]() ${map} : (X \to Y) \to H~F~X \to H~F~Y$

for any functor F as well as a function

${map} : (X \to Y) \to H~F~X \to H~F~Y$

for any functor F as well as a function

![]() ${hmap} : \mathrm{Nat}(F, G) \to \mathrm{Nat}(H~F, H~G)$

which lifts natural transformations between any F and G to a natural transformation between

${hmap} : \mathrm{Nat}(F, G) \to \mathrm{Nat}(H~F, H~G)$

which lifts natural transformations between any F and G to a natural transformation between

![]() $H~F$

and

$H~F$

and

![]() $H~G$