The relationship between the arts was central to Walter Pater’s literary criticism. In the works of the painter-poets William Blake and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Pater found an ideal corpus for thinking about form through visual analogies. However, while Rossetti plays a significant role in Appreciations (1889), Blake is a subterranean presence. Although Pater never devoted a whole essay to Blake, his name surfaces in discussions about form and style, image and meaning, and soul and mind. Artistic examples and analogies shape a comparative and complementary understanding of literature and art through exercises in appreciation and inter-artistic lines of cultural influence.

Pater made a significant number of references to Blake between 1871 and 1889, at a time when ‘this no longer unknown painter-poet … became a figure in our life of culture that it was in future impossible to ignore’, as Edmund Gosse put it.1 Blake’s Victorian position as a poet-painter was established by Alexander Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake, ‘Pictor Ignotus’ (1863), published after Gilchrist’s untimely death with a selection of Blake’s writings heavily edited by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and a catalogue by his brother William Michael. This was soon followed by Algernon Charles Swinburne’s William Blake: A Critical Essay (1868), and by two editions of Blake’s writings in 1874. Exhibitions in 1871 and 1876 were crucial to Pater’s engagement with Blake: in 1871 Blake’s tempera The Spiritual Form of Pitt featured in the second Exhibition of the Works of the Old Masters, associated with the Works of Deceased Masters of the British School at the Royal Academy. In 1876 Blake’s visual corpus was crystallised in a retrospective of 333 works at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, which also included The Spiritual Form of Nelson and The Spiritual Form of Napoleon. It is from these picture titles, rather than from Blake’s poetry, that Pater drew the concept of ‘spiritual form’, which is central to his essay ‘A Study of Dionysus: The Spiritual Form of Fire and Dew’ (1876). Tracing Pater’s explicit references brings into view Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job (1823–26), and visual modes of appreciation of verbal texts by means of an intermedial reading practice. For instance, Pater associates Sir Thomas Browne with the Soul ‘exploring the recesses of the tomb’ in Blake’s illustration to Robert Blair’s The Grave (1808) (App., 155). In addition to identifying the sensory work of visual images in shaping Pater’s acts of reading, references to Blake shed light on Pater’s tendency to turn to visual compositions to exemplify the interfusion of form and matter in literary writing. This chapter reconstructs Pater’s engagement with Blake, and examines the role that art appreciation played in developing his writing about literature. Pater’s Blake identifies a discipline of literary form that defies the separation of literature as a distinct aesthetic domain, showing how writing and reading are shaped by the multisensorial aesthetic of an inter-art critical practice.

Anachronies

Pater’s aesthetic criticism is underpinned by an ‘anachronic’ apprehension of time in which different historical moments can coexist.2 In a review of poems by William Morris (1868), Pater distinguishes his engagement with the past from ‘vain antiquarianism’, arguing for an embodied aesthetic: ‘the composite experience of all the ages is part of each one of us’. Looking back ‘we may hark back to some choice space of our own individual life’, capture a ‘more ancient life of the senses’, and experience ‘a quickened, multiplied consciousness’.3 In ‘The School of Giorgione’ (1877) Pater associates this temporal mode with ‘the highest sort of dramatic poetry’ for its capacity to create an interval, ‘a kind of profoundly significant and animated instants … which seem to absorb past and future in an intense consciousness of the present’ (Ren., 118). This composite experience of time paves the ground for Blake’s appearances in different historical moments in Pater’s writing.

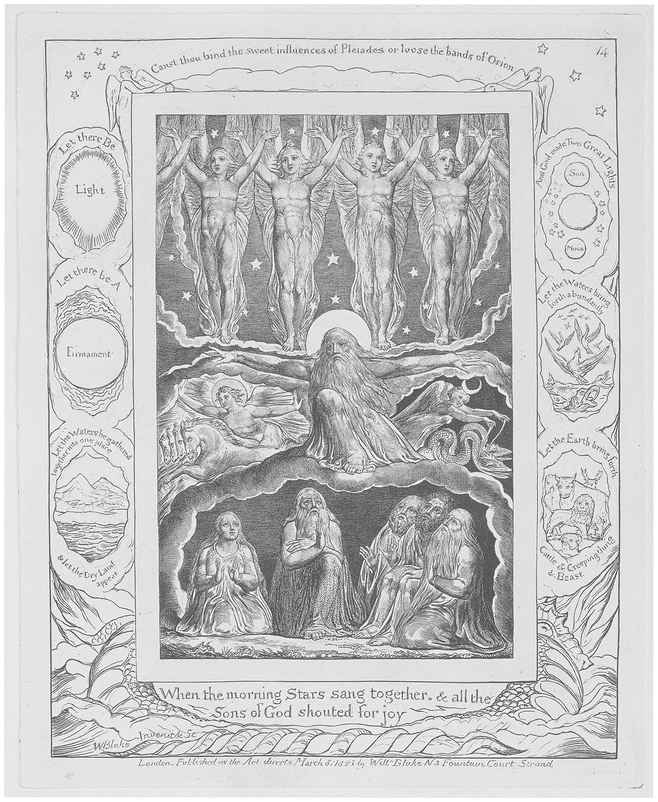

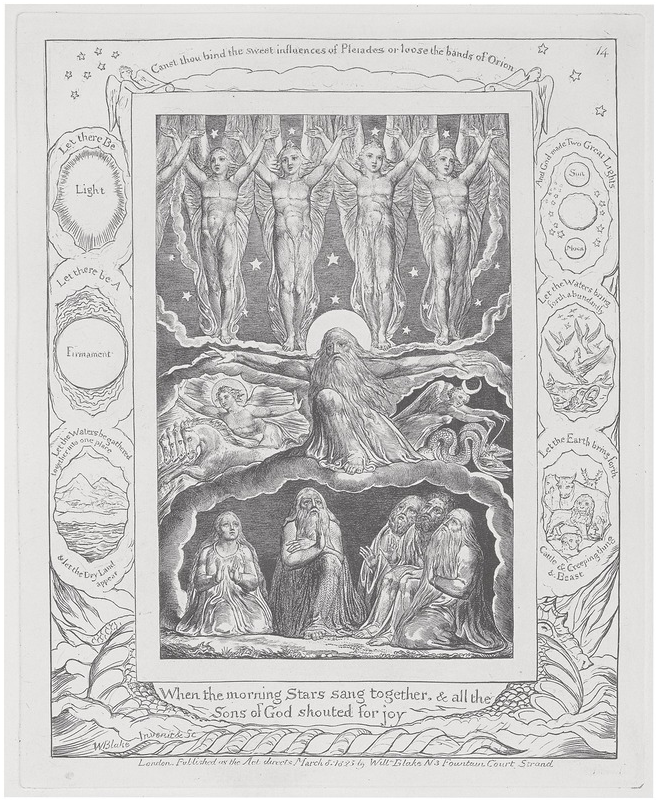

Blake’s name first surfaces on the initial page of Pater’s essay on ‘The Poetry of Michelangelo’, published in the Fortnightly Review in 1871, where Pater identifies the appeal of Michelangelo’s ‘sweetness and strength’ in terms of ‘strangeness’, a key element of ‘all true works of art’ (Ren., 57). ‘Strange’ is also a recurrent keyword in Swinburne’s Blake essay.4 Instead of a composed classical ideal, Pater appreciates in Michelangelo ‘the presence of a convulsive energy’, which is ‘the whole character of medieval art’ (57). Yet the medievalism that Pater finds in Michelangelo has a nineteenth-century ring, evoking the contortions of the swan’s neck in a poem that Baudelaire dedicated to Hugo,5 the first modern poet to be named on the opening page of the essay as a point of comparison. Then Pater refers to Leonardo and Blake to illuminate a contrast: ‘The world of natural things has almost no existence’ for Michelangelo; ‘He has traced … nothing like the fretwork of wings and flames in which Blake frames his most startling conceptions’ (58). These words allude to an engraving from Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job captioned ‘When the morning Stars sang together, & all the Sons of God shouted for joy’, which is a recurring image in Pater’s aesthetic thinking. While Blake’s composition might in itself exemplify ‘convulsive energy’, its function here is to foreground what is not found in Michelangelo’s ‘blank ranges of rock, and dim vegetable forms’ (58). However, as Pater locates these forms in ‘a world before the creation of the first five days’ (58), his explanation paradoxically brings Michelangelo closer to the Blake illustration used as a benchmark for thinking about such energy, since in Blake’s ‘When the morning Stars sang together’ ‘the fretwork of wings’ captures angels singing at the dawn of creation.

Pater’s appreciation is informed by a physiological aesthetic. Reworking Winckelmann’s classical ideal, he redefines the embodied relationship between surface and depth:

Beneath the Platonic calm of the sonnets there is latent a deep delight in carnal form and colour … The interest of Michelangelo’s poems is that they make us spectators of … the struggle of a desolating passion.

‘Carnal form’ surfaces through glimpses and an indirect play of allusions:

That strange interfusion of sweetness and strength is not to be found in those who claimed to be his followers; but it is found in many of those who worked before him, and in many others down to our own time, in William Blake, for instance, and Victor Hugo, who, though not of his school, and unaware, are his true sons, and help us to understand him, as he in turn interprets and justifies them. Perhaps this is the chief use in studying old masters.

Pater’s choice of words reveals a dialogue with Swinburne’s essay about Blake, celebrated for his ‘mixed work’ in which ‘text and design … so coalesce or overlap as to become inextricably interfused’.6 By echoing Swinburne’s critical account of Blake in his appreciation of Michelangelo, Pater’s writing evokes the intermingling and inextricable twofold nature of the hermaphrodite, and thus translates the concept of carnal form into an emblem for the fusion of the arts. Their ‘strange interfusion’ functions as a token for a hermaphroditic inter-art community in which Pater’s Michelangelo identifies Blake in the company of Swinburne and Rossetti, Gautier and Baudelaire.7 Perception generates anachronic, reciprocal ways of seeing: ‘studying old masters’ requires a practice of appreciation in which the reader understands Michelangelo through Blake and Hugo, and interprets and justifies Blake and Hugo through Michelangelo. Their simultaneous coexistence in the act of perception revokes the distance established by historical thinking.

Blake stands out of time in Pater’s ‘Preface’ to Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873). Against the historical impulse to identify the workmen embodying ‘the genius, the sentiment of the period’, Pater uses Blake to critique periodisation: ‘“The ages are all equal,” says William Blake, “but genius is always above its age”’ (Ren., xxi). 8 This aphorism from Blake’s marginalia to Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Royal Academy Discourses was excerpted in Gilchrist’s Life:

With strong reprobation our annotator breaks forth when Sir Joshua quotes Vasari to the effect that Albert Dürer ‘would have been one of the finest painters of his age, if,’ &c. ‘Albert Dürer is not “would have been!” Besides, let them look at Gothic figures and Gothic buildings, and not talk of “Dark Ages,” or of any “Ages!” Ages are all equal, but genius is always above its Age’.9

Blake’s criticism of periodisations that close off the past as past helps Pater to articulate the function of aesthetic criticism: to revitalise the past by identifying ‘the virtue, the active principle’ or ‘unique, incommunicable faculty, that strange, mystical sense of a life in natural things’ (Ren., xxii). In the ‘Conclusion’ to The Renaissance, reworked from his review of Morris, Pater advocates an enhanced aesthetic practice to capture fleeting impressions, ‘exquisite intervals’, ‘momentary acts of sight and passion and thought’ through ‘constant and eager observation’. ‘Every moment some form grows perfect in hand or face … for that moment only’; hence the need to ‘grasp at any exquisite passion, or any contribution to knowledge that seems by a lifted horizon to set the spirit free for a moment’ (186, 187, 188, 189). In what follows I will explore how this poetics of the moment informs Pater’s encounter with Blake.

When the Stars Sing Together

Blake’s anachronic appearances in ‘momentary acts of sight’ revitalise glimpses of a utopian past in essays associated with the plan for Dionysus and Other Studies, and published posthumously in Greek Studies in 1895. In an essay on Demeter and Persephone, published in the Fortnightly Review in January 1876, Pater discusses Blake in association with Edward Burne-Jones:

If some painter of our own time has conceived the image of The Day so intensely, that we hardly think of distinguishing between the image, with its girdle of dissolving morning mist, and the meaning of the image; if William Blake, to our so great delight, makes the morning stars literally ‘sing together’10 – these fruits of individual genius are in part also a ‘survival’ from a different age, with the whole mood of which this mode of expression was more congruous than it is with ours. But there are traces of the old temper in the man of to-day also.

Pater’s visual references flesh out an experience of erotic revelation surfacing in moments of vision that disappear in the rhythm of Pater’s syntax, concealed within an accumulation of hypothetical clauses, which move so fast as to limit or pre-empt the translation of words into images. First, a ‘girdle of dissolving morning mist’ promises to bring into full view not a landscape, but the genitalia of a handsome naked man in Burne-Jones’s painting Day (1870).11 His identity as a personification of Day is crystallised in a quatrain composed by William Morris inscribed on a fictive label in the threshold of the doorway, beneath the figure’s feet:

The ‘dissolving mist’ in this painting can be compared to the falling drapery revealing male genitalia in Burne-Jones’s Phyllis and Demophoön, a picture that he withdrew from the exhibition of the Society of Painters in Water-Colours in 1870. Burne-Jones painted Day for his patron Frederick Leyland, who had also bought Phyllis and Demophoön. The Illustrated London News compared Phyllis and Demophoön to ‘the amatory poetry of the Swinburne school’.13

A Swinburnian way of reading clarifies Pater’s juxtaposition of Burne-Jones with Blake. Pater’s ‘dissolving morning mist’ evokes the prophetic imagery that Swinburne associates with Blake, the ‘oracular vapour’ of work ‘made up of mist and fire’.14 In his essay on Blake Swinburne developed a hermaphroditic myth of origin in his reading of Blake’s emblem book The Gates of Paradise (1793, 1818), supplementing the ‘keys’ that Blake had provided ‘for the sexes’ in later printings. Swinburne could read Blake’s key to plate 5 in Gilchrist’s Life:

In Blake’s reasoning and self-doubting Swinburne registers the fall into division, turning Blake’s emblems into an expanded myth of origin in which man is: ‘“a dark hermaphrodite,” enlightened by the light within him, which is darkness – the light of reason and morality; evil and good, who was neither good nor evil in the eternal life before this generated existence; male and female, who from of old was neither female nor male, but perfect man without division of flesh, until the setting of sex against sex by the malignity of animal creation. Round the new-created man revolves the flaming sword of Law, burning and dividing in the hand of the angel, servant of the cruelty of God, who drives into exile and debars from paradise the fallen spiritual man upon earth’.16 Swinburne returned to his hermaphroditic aesthetics to capture the ‘double-natured genius’ and ‘double-gifted nature’ of the artist as poet and painter in his review of Rossetti’s poetry in 1870.17 His critical idiom resonates in Pater’s writings as a cipher for an intergenerational aesthetic community, opening the door to queer readings of Blake, which help to make sense of Pater’s critical juxtaposition of Blake with Burne-Jones.

The second image that Pater evokes is plate 14 from Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job, captioned ‘When the morning Stars sang together, & all the Sons of God shouted for joy’, a quotation from Job 38:7 (Figure 1). This work had great impact among the Pre-Raphaelites. Rossetti rephrased its caption in his poem ‘The Blessed Damozel’ (1850): ‘and then she spake, as when / The stars sang in their spheres’; in 1870, he added a variation: ‘Her voice was like the voice the stars / Had when they sang together.’18 In the entry on Blake’s Job inventions, which Rossetti contributed to Gilchrist’s Life, the engraving is praised as ‘a design which never has been surpassed in the whole range of Christian art’ (ii. 286–7). The framing roundels depicting the days of creation in Blake’s engraving inspired roundel decorations for the frames that Rossetti designed for his paintings Beata Beatrix (1864–70) and The Blessed Damozel (1875–79) to mark the threshold of experiences of mystic incarnation.19

Figure 1 William Blake (1757–1827), ‘When the morning Stars sang together, & all the Sons of God shouted for joy’, Illustrations of the Book of Job (1825), plate 14, 40.6 × 27.3 cm, Yale Center for British Art, Gift of J. T. Johnston Coe in memory of Henry E. Coe, Yale BA 1878, Henry E. Coe Jr., Yale BA 1917, and Henry E. Coe III, Yale BA 1946 (B2005.16.15).

In Pater’s writing, Blake’s illustration of Job demonstrates the visionary potential of aesthetic criticism. Blake’s engraving captures the speech with which ‘the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind’ (Job 38:1). The Biblical text addresses the reader in the second person: ‘gird up now thy loins like a man’ (38:3). Although this line is not reproduced in Blake’s engraving, it helps us to understand Pater’s incongruous association of the scene with the girdle of mist and the erotic promise of frontal revelation in Burne-Jones’s painting. While the Lord speaking in the whirlwind harshly questions where Job was at the moment of creation (38:4), suggesting that he was not there when ‘all the sons of God shouted for joy’ (38:7), this negative element is not featured in Blake’s selective quotation of ‘When the morning Stars sang together’. Both Blake and Burne-Jones open up that experience through a form of vicarious participation and re-enactment. In Pater’s prose the morning stars ‘sing together’ with Burne-Jones’s Day, offering a glimpse of utopian promise, perhaps announcing a new day of sexual freedom.

Most readers of the Fortnightly would hardly have visualised or remembered Burne-Jones’s painting, let alone grasped such a reference to an ‘image’ that is so intense that ‘we hardly think of distinguishing between the image … and the meaning of the image’ (‘The Myth of Demeter and Persephone’, GS, 99; CW, viii. 68). If Pater’s reference meant to evoke an experience of erotic incarnation, it was not for all to see. Unlike Blake’s Job illustration, which was printed in multiple copies, Burne-Jones’s Day is a unique art work produced for the dining room of Leyland’s home;20 it was not exhibited until two years after the publication of Pater’s essay.21 Burne-Jones’s withdrawal from the Water Colour Society exhibitions after 1870 indicates the boundaries of social decorum: the visual revelation of the male nude could only be shared within a restricted aesthetic community.22 Can prose evoke what painting cannot show? Pater’s later essay ‘Style’ argues that ‘the figure, the accessory form or colour or reference, is rarely content to die to thought precisely at the right moment, but will inevitably linger awhile, stirring a long “brain-wave” behind it of perhaps quite alien associations’ (App., 18). What defines the writer is a ‘tact of omission’, but also a tactic that activates the utopian possibility of images glimpsed in an ecstatic interval, ‘singing together’ for a moment, before disappearing in the rhythm of Pater’s prose.

Pater’s anachronic practice draws on an anthropological concept from E. B. Tylor’s influential Primitive Culture (1871). Like Michelangelo, who ‘lingers on; a revenant, as the French say, a ghost out of another age’ (Ren., 71),23 Blake and Burne-Jones are a ‘“survival” from a different age’. Tylor defines ‘survivals’ as ‘processes, customs, opinions … carried on by force of habit into a new state of society different from that in which they had their original home, and they thus remain as proofs and examples of an older condition of culture’.24 Pater applies this concept to the ‘spiritual life’ of nature in Wordsworth’s writing, a ‘“survival” … of that primitive condition, … that mood in which the old Greek gods were first begotten, and which had many strange aftergrowths’ (App., 46–8). While Pater’s Wordsworth reveals the survival of the primitive moods of nature in the present, his classical criticism finds modern counterparts in the past.

Spiritual Form

The most striking use of Blake occurs in ‘A Study of Dionysus: The Spiritual Form of Fire and Dew’, first published in the Fortnightly Review in December 1876, subsequently collected in Greek Studies in 1895. In this essay, Pater tracks the emergence of Dionysus as ‘the spiritual form of the vine, … of the highest human type’, ‘the reflexion, in sacred image or ideal’ of ‘the mystical body of the earth’, ‘the vine-growers’ god’ (GS, 15, 25, 28; CW, viii. 94, 99, 100). Religion emerges as a process of knowing by making, ‘shadowing forth, in each pause of the process, an intervening person—what is to us but the secret chemistry of nature being to them the mediation of living spirits’, a ‘fantastic system of tree-worship’ (GS, 13, 14; CW, viii. 93). For Pater the ‘office of the imagination’ (GS, 32; CW, viii. 102) is to capture this evanescent form refracted through different arts: remnants of ‘primitive tree-worship … found almost everywhere in the earlier stages of civilisation, enshrined in legend or custom’ show that the ancient ‘fancy of the worshipper’ persists in modern ‘poetical reverie’. For instance, in Percy Shelley’s Sensitive Plant the spiritual metamorphosis of plants ‘may still float about a mind full of modern lights, the feeling we too have of a life in the green world, always ready to assert its claim over our sympathetic fancies’ (GS, 11; CW, viii. 92). Sculpture can ‘condense the impressions of natural things into human form; … retain that early mystical sense of water, or wind, or light, in the moulding of eye and brow; … arrest it, or rather… set it free’ (GS, 32–3; CW, viii. 102). Human form offers a mould for ‘the spiritual flesh allying itself happily to mystical meanings’, but this human limitation is precarious, always in ‘danger of an escape from them of the free spirit of air, and light, and sky’ (GS, 34; CW, viii. 103). Pater’s search for the primitive mystical union of the spirit with nature, working against the divided condition of the modern mind, is close to Blake’s embodied enthusiasm.

The notion of ‘spiritual form’ derives from Emanuel Swedenborg’s account of human perfection seen from an angelic point of view and underpinned by a dualist distinction between the human body’s earthly and spiritual form.25 Emblematic of this ‘divided imperfect life’ is the ‘spiritual philosophy’ of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (App., 71, 82), whose poetry Pater compares to Blake’s visionary ability to see spirits in the everyday, ‘that whole episode of the re-inspiriting of the ship’s crew in The Ancient Mariner being comparable to Blake’s well-known design of the “Morning Stars singing together”’ (App., 97). The difference between the painter-poet and the philosopher-poet indicates ‘a change of temper in regard to the supernatural which has passed over the whole modern mind, and of which the true measure is the influence of the writings of Swedenborg’ (98). Access to a supernatural sense requires an altered state, or a visionary work of art that exhibits a moment of revelation and ‘re-inspirits’ the reach of words through a complementary appeal to the senses, which can heal the division between spirit and matter, subject and form.

In Pater’s writing, the concept of ‘spiritual form’ signals a paradox; so too does its attribution to Blake two-thirds of the way into the Dionysus essay:

Well,— the mythical conception, projected at last, in drama or sculpture, is the name, the instrument of the identification, of the given matter, — of its unity in variety, its outline or definition in mystery; its spiritual form, to use again the expression I have borrowed from William Blake—form, with hands, and lips, and opened eyelids—spiritual, as conveying to us, in that, the soul of rain, or of a Greek river, or of swiftness, or purity.

The term ‘spiritual form’ appears only once in Blake’s poetical corpus. While Blake uses the expression ‘spiritual body’ in the Swedenborgian sense in an illustration for ‘To Tirzah (‘It is raised a spiritual body’) and in Night VIII of Vala or the Four Zoas, 26 in Jerusalem, the ‘spiritual forms’ in Luvah’s sepulchre will ‘wither’ without a veil. An apocalyptic weaving of bodies is required to protect humanity from its state of splitting and separation in order to restore the original unity of the eternals.27 In other words, Blake uses the word ‘spiritual’ to describe a fallen state of separation that emphasises the paradoxical contradiction inherent in the concept of ‘spiritual form’. The tension between ideal, dystopian, and parodic is active in William Michael Rossetti’s ‘Prefatory Memoir’ to the Aldine edition of Blake’s works in 1874. After discussing Blake’s ‘spiritual sense’ and ‘spiritual eye’, he alludes to the ‘spiritual visitants’ that Blake captured in his visionary heads, and wonders whether Blake will approve of ‘the present re-issue of the Poetical Sketches’, a ‘portrait’ that is ‘a reflex of his “spiritual form”’.28 Will the edition capture Blake’s corpus or a divided image, a caricatural distortion like his visionary heads? The ambiguous possibilities of this statement register Blake’s own ambivalent relationship with Swedenborg.

The Blakean source for Pater’s concept of ‘spiritual form’ is a pictorial title: The Spiritual Form of Pitt is the only Blake painting entered in the Royal Academy’s Old Masters exhibition in 1871, but the English politician is joined by the ‘Spiritual Forms’ of Nelson and Napoleon in the Burlington Fine Arts Club Blake retrospective in 1876.29 In the ‘Introductory Remarks’ to the catalogue, William Bell Scott argues that ‘the Spiritual Form of Pitt’ is a puzzle, ‘among the most difficult to decipher’.30 A review of the 1876 exhibition recalls the public’s reaction to the painting at the Old Masters exhibition in 1871: ‘a stout segment of Respectability who looked at the picture, solemnly read to his companion the title, The spiritual form of William Pitt guiding Behemoth, looked again, shook his head’.31 Yet what the review cites is the title as it appears in the catalogue of 1876.32 The catalogue entry in 1871 reads:

William Pitt

‘The spiritual form of Pitt guiding Behemoth. He is that angel who, pleased to perform the Almighty’s orders, rides in the whirlwind, directing the storms of war. He is commanding the Reaper to reap the vine of the earth, and the ploughman to plough up the cities and towers.’ —.

In 1871 comparing the catalogue entry with the tempera hanging on the wall produced an experience of double vision. The title, ‘William Pitt’, raised the expectation for a historical portrait, but it was subverted by the grotesque revelation of a nude and a demonic Dionysian counterpart. Blake’s visionary portraiture exploits the possibilities of allegory as a satirical yoking of opposites, which is closer to Samuel Johnson’s denunciation of metaphysical wit, than to an ideal of style in which form and meaning coalesce in ways that cannot be separated.

The dialectical tension between visionary allegory and historical portraiture in The Spiritual Form of Pitt undermines the Swedenborgian framing of Blake in the Burlington Fine Arts Club catalogue of 1876. In his ‘Introductory Remarks’, Scott quotes from the Swedenborgian John Garth Wilkinson’s preface to Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1839): ‘if it leads one reader to think that all Reality for him, in the long run, lies out of the limits of Space and Time; and that Spirits, and not bodies, and still less garments, are men … it will have done its work in its little day’.34 Still drawing on Wilkinson, Scott goes on to detail Blake’s objection to nature – ‘natural objects did and do weaken, deaden, and obliterate imagination in me’ – to articulate an alternative form of ‘determinate vision’, which does not mean that ‘the object is visible to the eye, but that it is apparent to the mental vision, by interior light’.35 Scott cites Wilkinson announcing that Songs of Innocence represent ‘the New Spiritualism which is now’, in 1839, ‘dawning on the world’ (9). This Swedenborgian reception of Blake can find some corroboration in Blake’s ambivalent return to Swedenborg in the late 1800s, probably under the influence of Charles Augustus Tulk, whose copy of Songs provided the basis of Wilkinson’s edition.36 However, Scott’s claim that Blake was ‘sympathetic’ to Swedenborg (10) goes against the evidence of Blake’s ‘objurgatory’ marginalia to a copy of Swedenborg’s Angelic Wisdom, which was brought to the Burlington Fine Arts Club at the time of the exhibition. W. M. Rossetti’s review of Scott’s catalogue reminds the reader of Blake’s critical denunciation of Swedenborg in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, where he claimed that ‘any man of mechanical talents may, from the writings of Paracelsus or Jacob Behmen, produce ten thousand volumes of equal value with Swedenborg’s’.37 In the context of the exhibition Pater’s incongruous association between Dionysus as a celebration of nature and Blake’s dystopian pictorial title is puzzling. The strong language that shapes Pater’s attribution of ‘spiritual form’ to Blake as an example of ‘unity in variety’ suggests something more than meets the eye.

Both Blake and Pater think about form through a relationship with Greek sculpture and Greek gods. Blake first exhibited his spiritual form paintings in 1809 and discussed them in A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures, Poetical and Historical Inventions, reprinted in Gilchrist’s Life: ‘The two Pictures of Nelson and Pitt are compositions of a mythological cast, similar to those Apotheoses of Persian, Hindoo, and Egyptian Antiquity … wonderful originals … from which the Greeks and Hetrurians copied Hercules Farnese, Venus of Medici, Apollo Belvidere, and all the grand works of ancient art.’38 In the next catalogue entry on Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims, also exhibited in 1876, Blake uses classical sculptural prototypes to capture ‘characters repeated again and again, in animals, vegetables, minerals, and in men … physiognomies or lineaments of universal human life’.39 Such were, for Blake, the ‘Grecian gods’, ‘visions of eternal attributes, or divine names, which, when erected into gods, become destructive to humanity’.40 Blake develops his negative account of the effects of apotheosis in his entry about The Spiritual Preceptor, an experiment Picture, a subject

taken from the Visions of Emanuel Swedenborg. Universal Theology, No. 623 … corporeal demons have gained a predominance; who the leaders of these are, will be shown below. Unworthy Men, who gain fame among Men, continue to govern mankind after death, and, in their spiritual bodies, oppose the spirits of those who worthily are famous.41

Here ‘spiritual’ stands for an antithetical destructive power of division.

Pater repurposes Blake’s dystopian image through an intermedial act of criticism that exemplifies the practice of misquotation, misrepresentation, or deliberate appropriation discussed by Christopher Ricks.42 Pater’s intervention discards the negative associations of ‘spiritual form’ as an instrument of political imposition. It is Blakean in spirit, if not in the letter, because to repurpose the concept of ‘spiritual form’ means to release the utopian potential of the ‘human form divine’ and restore the eternal body that Blake sought to heal in his prophetic writings.

Style: ‘Soul and Body Reunited’

Blake’s visual inventions come to Pater’s mind when he explores forms that cannot be captured through logical processes of reasoning structured around distinctions or boundaries between the arts. In ‘The School of Giorgione’ Pater argues for the incommunicable, ‘untranslatable sensuous charm’ peculiar to each art (Ren., 102). Building on Lessing’s Laocoon, Pater argues that ‘[o]ne of the functions of aesthetic criticism is to define these limitations; to estimate the degree in which a given work of art fulfils its responsibilities to its special material’ (102). Yet as the artist produces form out of matter, ‘in its special mode of handling its given material, each art may be observed to pass into the condition of some other art, by what German critics term an Anders-streben —a partial alienation from its own limitations’ (105). This does not mean that they can replace each other or turn into music, following the progression from more material to more spiritual forms set out in Hegel’s Aesthetics, but that they ‘reciprocally … lend each other new forces’ in the ‘constant effort … to obliterate’ the distinction between matter and form (105, 106). Since Pater argues that poetry needs to find ‘guidance from the other arts’ (105), what ‘guidance’ do Blake’s visual compositions provide in Pater’s search for literary form?

At the level of composition, in Blake’s Chaucer’s Pilgrims and the Spiritual Form of Pitt Pater finds visual approaches to the revelation of eternal characters resurfacing in different times, a type of recognition that Pater explored in different writing genres, from classical criticism to the Imaginary Portraits. The ‘Grecian gods’ that Blake sees in Chaucer’s Pilgrims may well have prompted Pater’s association of Chaucer with the Marbles of Aegina, discussed in Chapter 2, while Blake’s Dionysian Pitt offers a model for developing literary character in his ‘quaint legend’ ‘Denis L’Auxerrois’ (IP, 47; CW, iii. 81).

Blake’s art helps define form in literary writing by means of analogy, through visionary moments of aesthetic plenitude. While ‘poetry … works with words addressed in the first instance to the pure intelligence’ (Ren., 107), in Blake Pater finds art informed by artistic spirit that can heal the modern dissociation of mind and soul: ‘meaning reaches us through ways not distinctly traceable by the understanding, as in some of the most imaginative compositions of William Blake’ (Ren., 108). Visual associations complement words, enhancing their reach by appealing to the senses and supplementing the limitations of the understanding.

In ‘Style’, after defining the pleasure of ‘conscious artistic structure’, Pater turns to the literary artist’s mode of communication by means of soul as opposed to mind and finds in Blake ‘an instance of preponderating soul, embarrassed, at a loss, in an era of preponderating mind’ (App., 24, 25). Consider Pater’s wording against J. Comyns Carr’s introduction to Blake for T. H. Ward’s English Poets (1880), which sums up a nineteenth-century tradition around Blake’s insanity:

he possessed only in the most imperfect and rudimentary form the faculty which distinguishes the functions of art and literature; and when his imagination was exercised upon any but the simplest material, his logical powers became altogether unequal to the labour of logical and consequent expression. … If Blake had never committed himself to literature we should scarcely be aware of the morbid tendency of his mind. It is only in turning from his design to his verse that we are forced to recognize the imperfect balance of his faculties.43

Blake’s appeal to Pater is in stark contrast to Comyns Carr’s indictment of his ‘imperfect balance’ of faculties. On the contrary, Pater reaches out to Blake to rebalance the division of the faculties; against Comyns Carr’s separation of the artist from the poet, Pater seeks in the artist the complement of sense that is needed to ‘inspirit’ poetry.

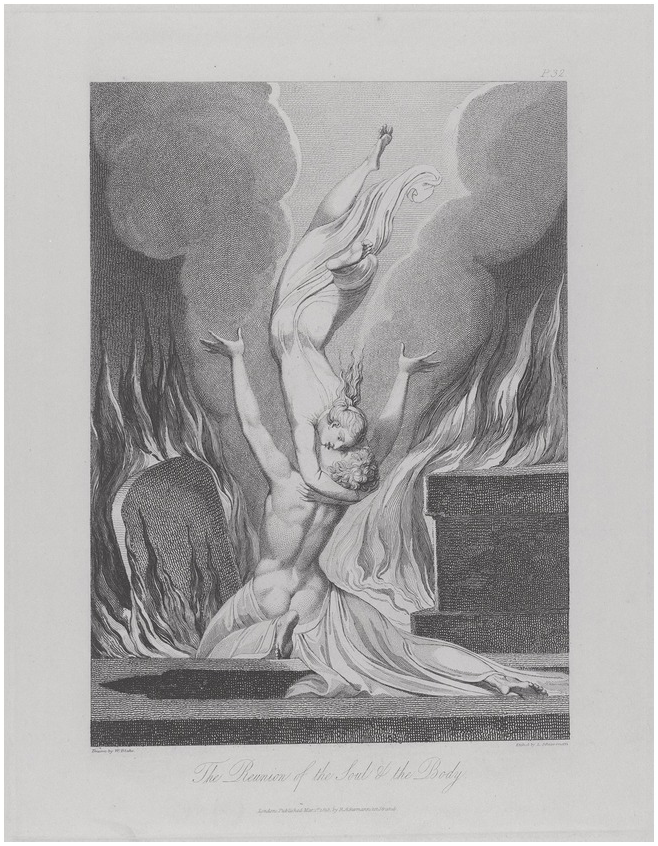

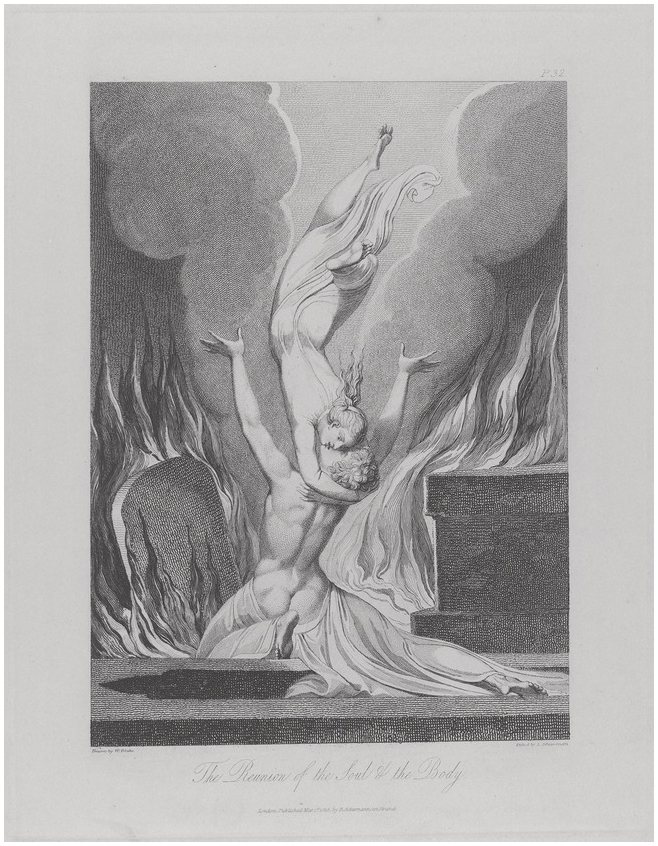

Blake’s visionary art articulates an aesthetic politics for modern literature, which is neither objective, nor ‘legible to all; by soul, he reaches us, somewhat capriciously perhaps, one and not another, through vagrant sympathy and a kind of immediate contact’ (‘Style’, App., 25). This formula activates an experience of aesthetic embodiment that traverses Pater’s critical idiom, from the early formulation of ‘carnal form’ to ‘spiritual form’. Pater goes on to discuss ‘soul’ operating through ‘unconscious literary tact’ and ‘immediate sympathetic contact’ (26) in terms of religious literature and the ‘plenary substance’ of ‘what can never be uttered’ (27), then shifts to the ‘martyr of literary style’, Gustave Flaubert, and returns to Blake to illustrate his ‘adaptation’ between thought and language, ‘meeting each other with the readiness of “soul and body reunited,” in Blake’s rapturous design’ (27, 30, Figure 2). This reference to Blake ironically recentres the passion for style that Flaubert advocates in a passage from his correspondence with Madame X quoted in the essay. As a tangible image of what is left unsaid, Blake’s illustration to Robert Blair’s The Grave becomes an emblem of the complementarity of text and image, showing how visual allusion integrates writing by addressing the senses and pointing to an experience of embodiment in which thought and language coalesce in ways that words alone fail to express.

Figure 2 Louis Schiavonetti (1765–1810), after William Blake (1757–1827), ‘The Reunion of the Soul & the Body’, illustration to The Grave, A Poem. By Robert Blair. Illustrated By Twelve Etchings Executed From Original Designs. To Which Is Added A Life Of The Author, London, Published Mar. 1st 1813, by R. Ackermann, 101 Strand, sheet 38.1 × 28.9 cm, plate 29.8 × 22.9 cm, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection (B1974.8.6).