Key results

-

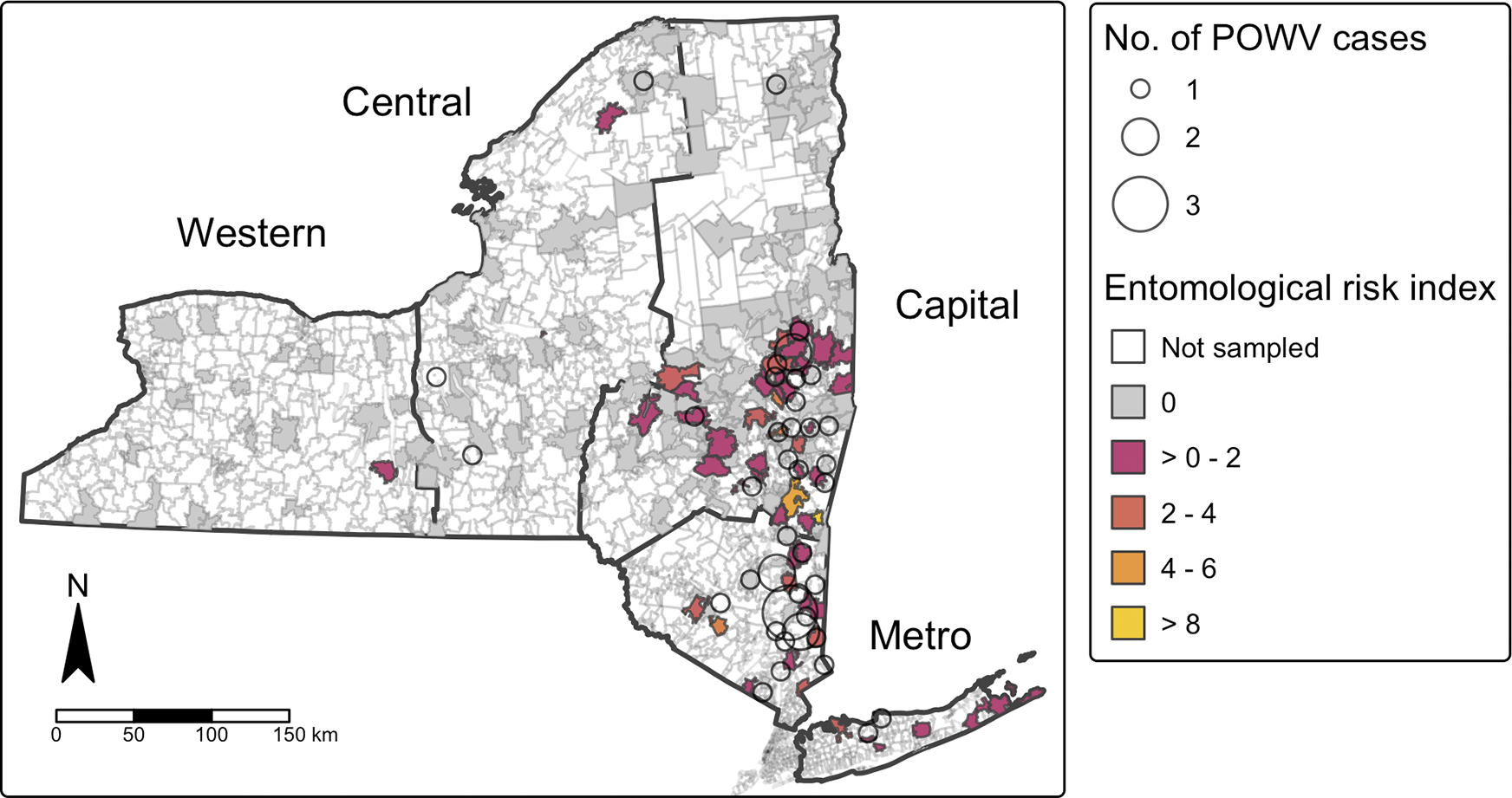

• From 2013 to 2023, POWV infection incidence in New York State was highest in southeastern counties, particularly Columbia and Putnam.

-

• The majority of reported cases occurred in White, non-Hispanic males aged ≥50 years; hospitalization was reported in 91% of cases, and 11% were fatal.

-

• Prevalence of POWV in I. scapularis populations increased over the study period statewide (p < 0.05), with the highest increases among adult ticks in the Capital Region (p < 0.002).

-

• Spatial clustering of human cases corresponded to areas with elevated Entomologic Risk Index (ERI).

-

• Adult ERI showed a significant association with human POWV incidence at the ZIP code level (p < 2.2e-16, Spearman’s p = 0.195), underscoring the importance of surveillance in identifying high-risk areas for targeted public health interventions.

Introduction

Powassan virus (POWV) is an emerging tick-borne flavivirus that causes long-term neurological sequelae in about half of reported clinical cases, and fatality in about 10 % of cases classified as neuroinvasive [Reference Ebel1–3]. First identified in Powassan, ON, Canada, POWV was isolated from the brain tissue of a paediatric patient with fatal encephalitis in 1958 [Reference McLean and Donohue4]. The first human case in the United States (US) was later identified in New Jersey in 1970 [Reference Goldfield5]. POWV is the only tick-borne flavivirus found in North America and is presently endemic to North America and Northeastern Russia [Reference McMinn6].

There are two distinct genetic lineages of POWV, which can cause infection in humans: lineage I, prototype Powassan virus (POWV-1), and lineage II, Deer Tick virus (DTV) [Reference Telford7]. While POWV-1 was isolated from the first Powassan case in North America, DTV was not identified in ticks in North America until 1995 [Reference Telford7]. The two POWV lineages, while genetically and ecologically distinct, cannot be serologically distinguished [Reference Piantadosi and Solomon8].

POWV lineage I and II each have unique enzootic cycles but are both maintained in the environment between Ixodid ticks and various vertebrate hosts. POWV-1 is principally sustained between Ixodes cookei ticks and groundhogs (Marmota monax) and mustelids. It is also cycled between Ixodes marxi ticks and arboreal squirrels [Reference Artsob and Monath9]. DTV is thought to be maintained between I. scapularis ticks and white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) [Reference Telford7, Reference Artsob and Monath9]. Recent evidence also suggests that shrews may serve as a reservoir of DTV for host-seeking I. scapularis ticks [Reference Goethert10]. I. scapularis is a generalist which feeds on a wide variety of hosts, including humans [Reference Vogels11, Reference Eisen, Eisen and Beard12]. As such, I. scapularis transmits a variety of pathogens across its geographic range and is likely the primary vector of POWV infection in humans in the US [Reference McMinn6].

Transmission of pathogens from I. scapularis ticks occurs during blood feeding [Reference Feder13]. While transmission of other pathogens from I. scapularis, such as Borrelia burgdorferi (causative agent of Lyme disease) and Babesia microti (causative agent of babesiosis), take a minimum of 36 h of tick attachment, POWV has been demonstrated experimentally to transmit in as little as 15 min of tick feeding time [Reference Ebel and Kramer14]. In humans, POWV infection has occurred after less than 6 h of tick attachment [Reference Feder13]. The shortened transmission window of POWV heightens the risk of human infection when compared with other tick-borne pathogens because feeding ticks often go unnoticed and public health messaging emphasizing “daily tick checks” may prove ineffective at preventing virus transmission.

Historically, POWV morbidity and mortality in the US has been low despite its rapid transmission rate and high case-fatality rate. However, cases of POWV infection have increased considerably across the US over the last two decades, likely due to a combination of increased disease diagnostic capacity, surveillance efforts, and increases in vector distribution and density driving disease emergence [3]. POWV human infection is also suspected to be more common than reported case data indicate, as subclinical or mild cases of POWV are rarely reported [Reference Piantadosi and Solomon8]. In the US, human POWV cases are concentrated in the Northeast and Upper Midwest [3]. New York State (NYS) is among several states with the highest number of reported cases of POWV human infection in the country, including Minnesota and Wisconsin in the Midwest, and Massachusetts in the Northeast. Reported POWV cases in these four states accounted for nearly 70% of all reported cases nationwide from 2004 to 2023 [3]. In the years from 2013 to 2023, 291 human cases of POWV were reported nationally, 15% of which were from NYS (n = 44) [3]. The goals of this study were to better describe the epidemiology of POWV infection in NYS and to potentially identify populations at increased risk of exposure to POWV. Tick-borne pathogen surveillance data from the NYS Department of Health (NYSDOH) was also analysed to assess the presence and distribution of POWV in tick populations across NYS to elucidate geospatial risk for POWV infection.

Methods

Powassan virus cases

We conducted a review of all human cases of POWV infection that were reported to the NYSDOH during 2013–2023. POWV infections and arboviral encephalitis are reportable conditions under NYS public health law [15]. Suspect cases are reported directly by medical providers and electronically through positive commercial laboratory reports. Local county health departments conduct case investigations to determine case status based on the prevailing national surveillance case definition at time of diagnosis [16]. Case data obtained from investigation efforts were entered and tracked in the NYSDOH Communicable Disease Electronic Surveillance System. Both confirmed and probable cases were included in this study. Case demographic data were summarized in Microsoft Excel version 16.93.1 using descriptive statistics, mean and SD for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for categorical variables.

Tick collection and testing

Host-seeking I. scapularis were collected from public lands across NYS from 2013 to 2023 using standardized dragging and flagging surveys as previously described [Reference Prusinski17]. Collection sites were chosen based on tick habitat suitability and potential for human exposure to ticks (e.g. presence of understory vegetation and hiking trails) or were epidemiologically linked to cases of POWV infection. I. scapularis larvae and nymphs were primarily collected during periods of peak larval (August) and nymphal (May–July) activity by dragging a 1m2 piece of white flannel through leaf litter and low brush. I. scapularis adults were primarily collected during periods of peak adult (October–November) activity by flagging a 1m2 piece of white canvas along understory vegetation up to 1 m high. Ticks were stored at 4 °C until identified using dichotomous keys and sorted into pools by collection site and date, species, and developmental stage [Reference Keirans and Clifford18]. Pools of up to ten ticks each were stored at −80 C until screened by real-time RT-PCR for the presence of POWV-1 and DTV as previously detailed [Reference Dupuis19].

Data analysis

POWV case reports meeting criteria for inclusion were analysed using SAS 9.4. POWV infection cases were mapped using RStudio 2024.04.2 + 764 and QGIS 3.34 according to ZIP code tabulation area (ZCTA) using ZIP code of patient residence and 2018 American Community Survey 5-year estimates of population and shapefile [20]. Spatial autocorrelation of POWV infection cases at the ZCTA level was determined using the global and local Moran’s I statistic. Moran’s I k-nearest neighbour value was estimated a priori as the average number of ZCTAs per county in NY (k = 29). Local Moran’s I test identified clusters of POWV as statistically significant using α of 0.05.

Tick collection and pathogen prevalence, statistical analyses, and data visualizations were achieved with Microsoft Excel, R studio 2024.04.2 + 764 and QGIS 3.34. Pathogen prevalence was calculated as the minimum infection rate, or the number of pools of I. scapularis ticks testing positive for POWV divided by the total number of ticks tested at the site level and for each of four NYS regions (Capital, Central, Metro, and Western) (Figure 1). A linear regression model was built to estimate temporal changes in pathogen prevalence in I. scapularis populations over the study period (α = 0.05). Risk of exposure to POWV was estimated using an entomologic risk index (ERI), a measure of the population density of pathogen-carrying ticks [Reference Mather21]. ERI was calculated separately for nymphal and adult ticks as the product of tick population density (ticks per 1,000 m2 sampled) and POWV prevalence at each collection site. ZCTA-level ERI was calculated as the average ERI of all sites within the ZCTA for each tick developmental stage over the study period. Correlation of POWV infection incidence and ERI over the study period was assessed at the ZCTA level using Spearman’s rank correlation.

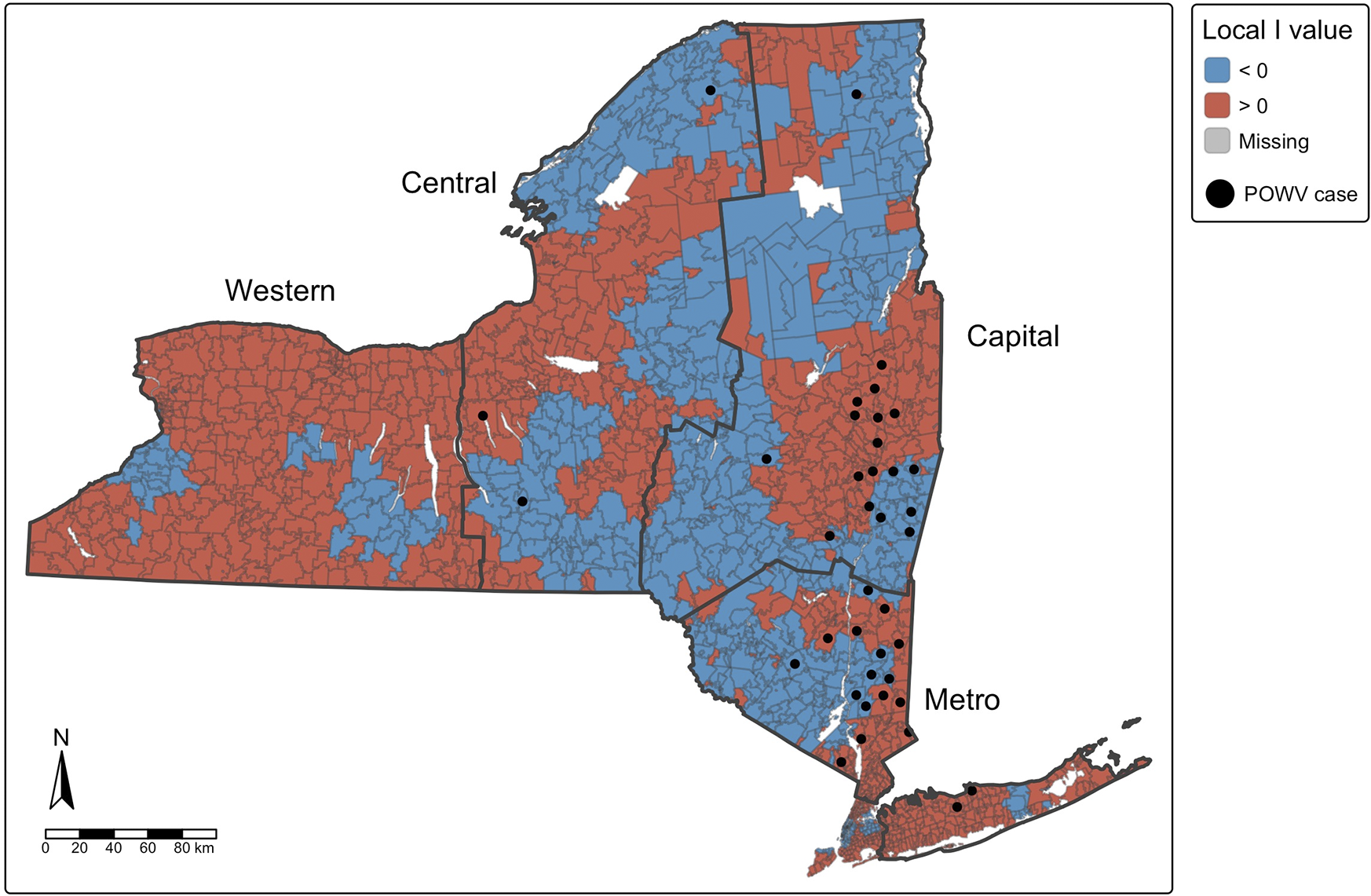

Figure 1. Spatial autocorrelation of cases of Powassan virus infection (Moran’s I), with human cases overlaid by ZIPCode Tabulation Area (ZCTA), New York State, 2013–2023. Positive values (red) indicate ZCTAs where highrisk areas are surrounded by other high-risk areas (high-high clustering), while negative values (blue) indicate ZCTAs where low-risk areas are surrounded by other low-risk areas (low-low clustering). ZCTAs where high-risk areas are adjacent to low-risk areas (or vice versa) are considered spatial outliers.

Results

Powassan virus epidemiology

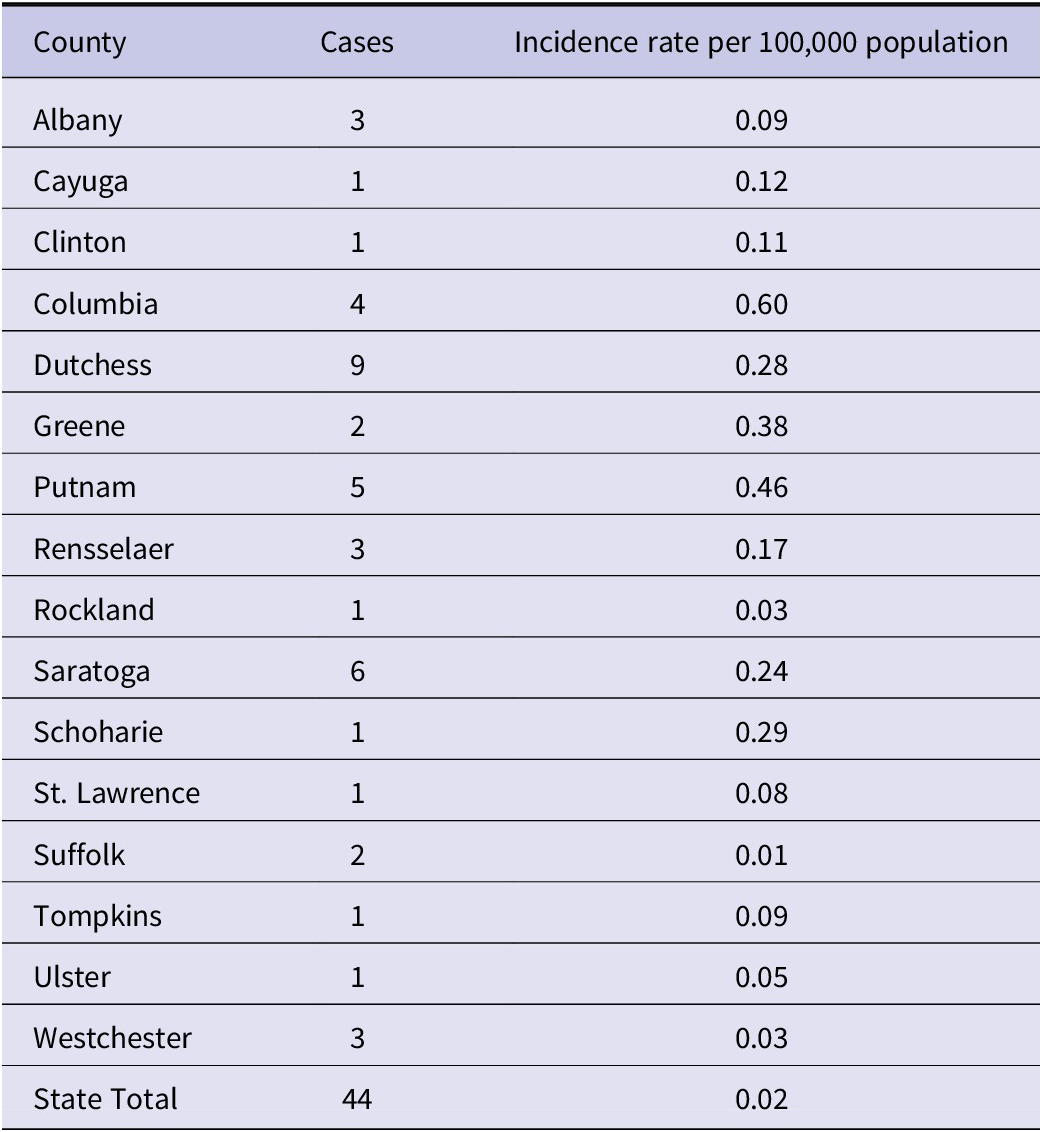

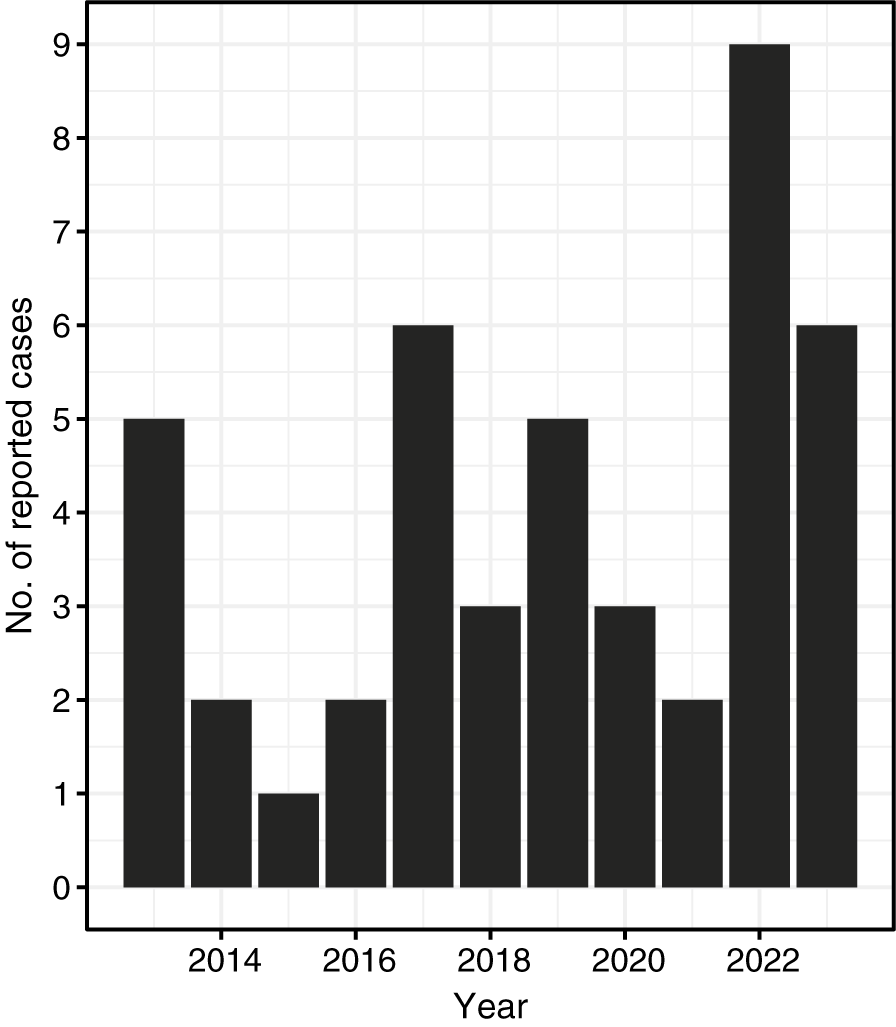

A total of 44 cases of POWV were reported in NYS from 2013 to 2023, excluding data from New York City, which conducts independent jurisdictional vector and epidemiological surveillance and reporting for the 5 New York City boroughs. Over the study period, a median of three cases/year were reported across NYS (range: 1–9 cases/year) (Table 1). County-level incidence rates over the 11-year study period were highest in two counties in southeastern NYS: Columbia County (0.59 cases/100,000 person-years at risk) and Putnam County (0.46 cases/100,000 person-years at risk) (Table 2). The statewide incidence was 0.02 cases/100,000 person-years at risk over the study period.

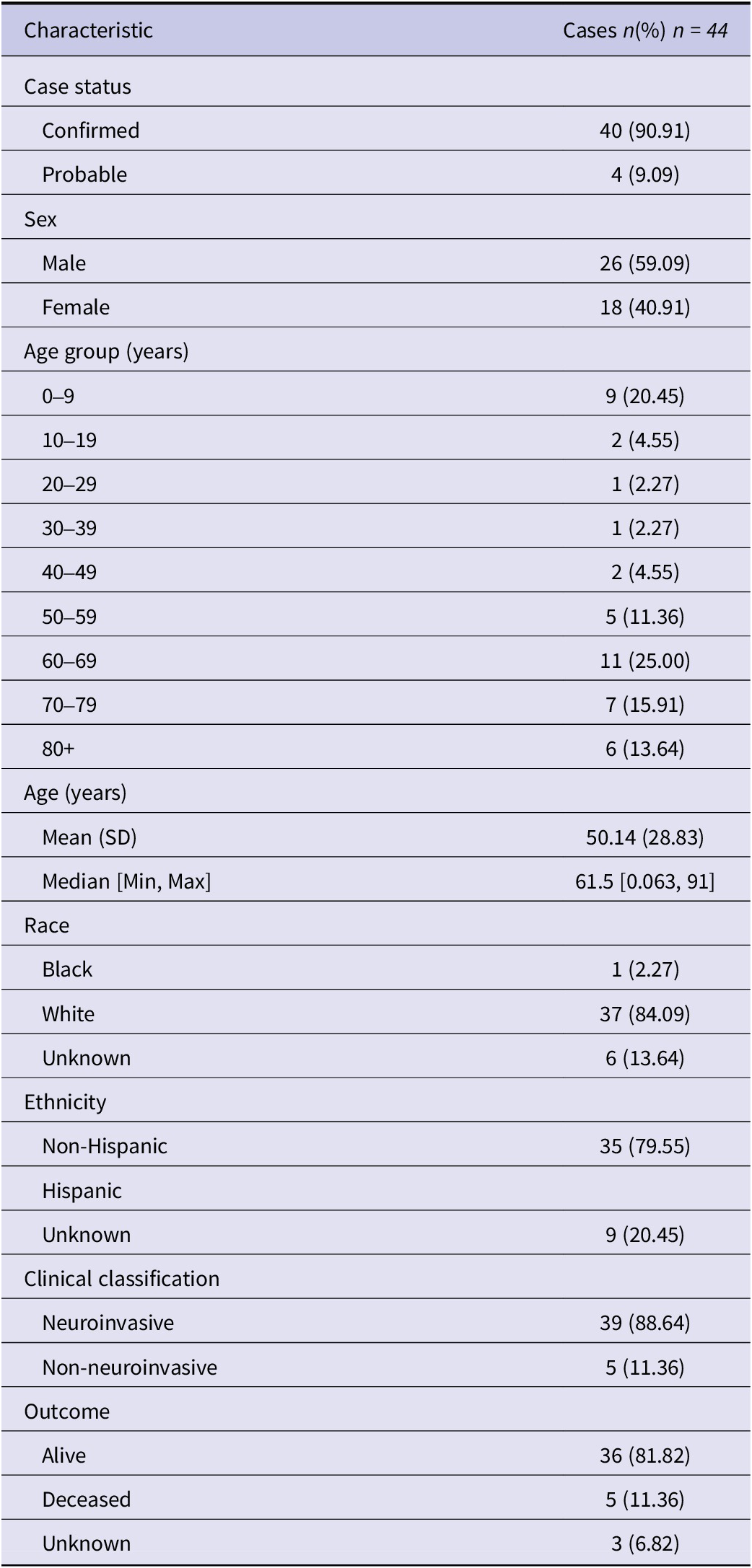

Table 1. Demographic and epidemiological characteristics of reported cases of Powassan virus infection in New York State, 2013–2023

Table 2. Number of reported cases of Powassan virus infection and incidence rates per 100,000 population by county, New York, 2013–2023

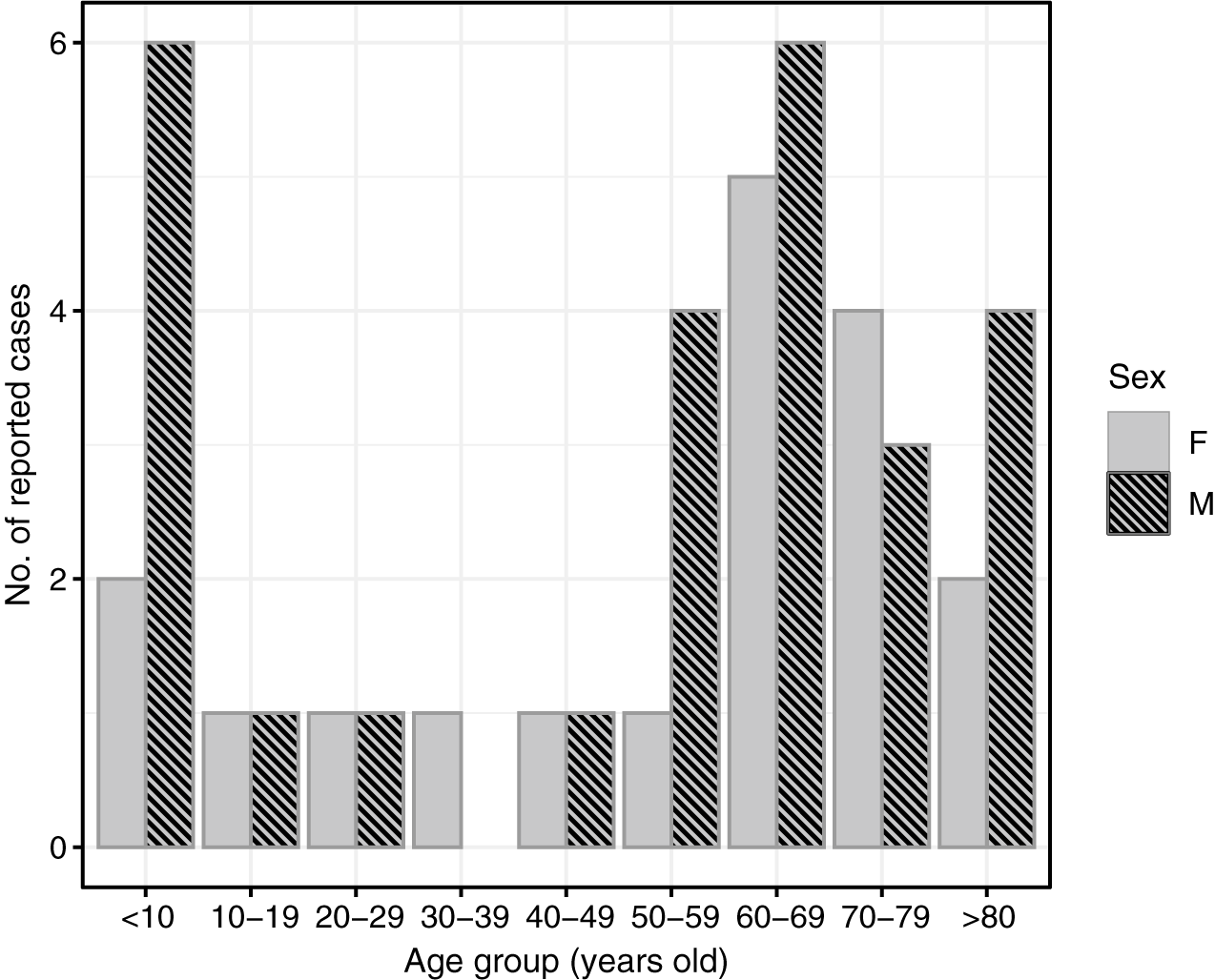

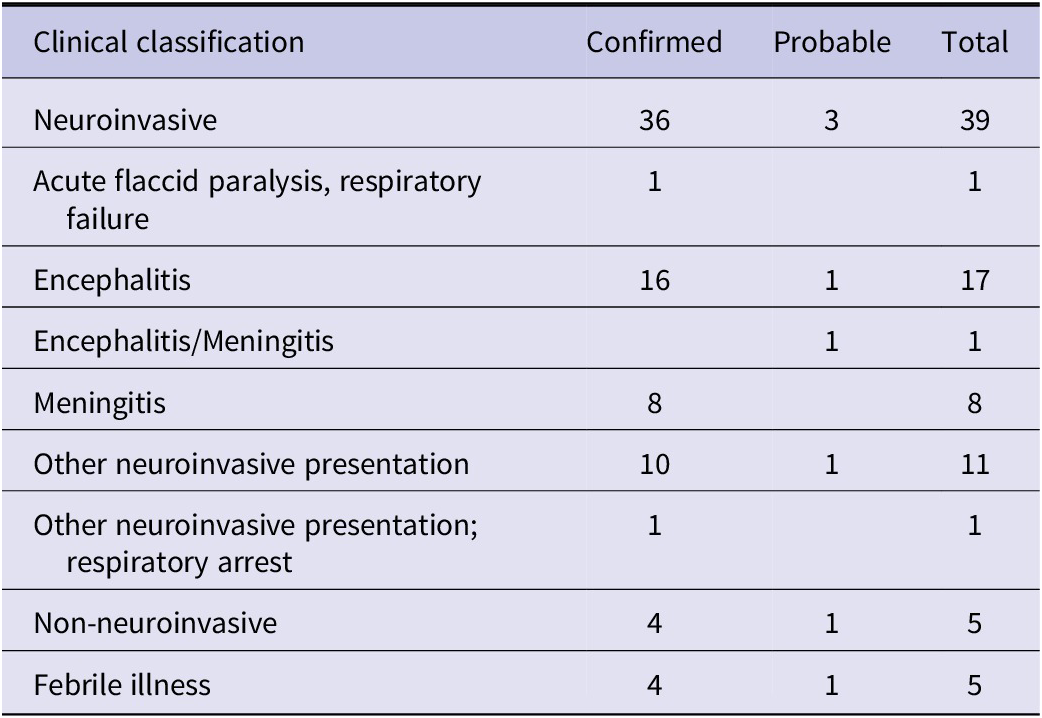

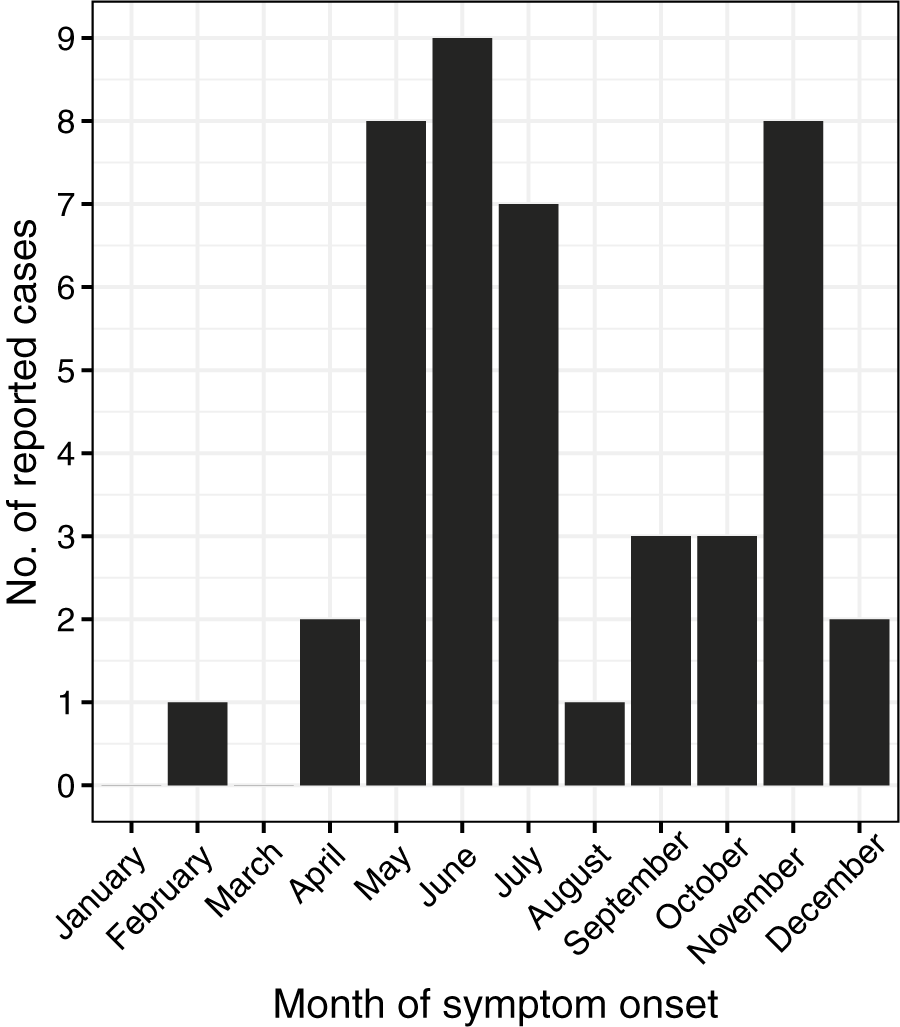

Cases of POWV infection were most common among males and those who identified as White and non-Hispanic (Table 1). Patients over the age of 50 accounted for 65.9% of cases, while those under age ten accounted for 20.5% of cases (Figure 2). Notably, two cases were infants, one aged 1 month, and the other 23 days old. Of the 44 patients diagnosed with confirmed or probable POWV infection, 90.9% were hospitalized. Five (11.4%) patients died and the outcome for three patients (6.8%) is unknown. The most common clinical symptom among patients with neuroinvasive POWV infection was encephalitis, followed by a broad range of other neuroinvasive symptoms and meningitis (Table 3). Acute flaccid paralysis and respiratory failure were the least common clinical syndromes among reported cases. All (100%) patients with non-neuroinvasive POWV infection reported symptoms of febrile illness. Symptom onset occurred most often in patients between May–July and in November (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Number of reported cases of Powassan virus infection by age group and sex, New York, 2013–2023 (N = 44).

Table 3. Reported clinical signs and symptoms among 44 persons with Powassan virus infection, New York, 2013–2023

Note: Likely incomplete symptomologies. Includes all available information provided by the NYSDOH Communicable Disease Electronic Surveillance System.

Figure 3. Number of reported cases of Powassan virus infection by month of symptom onset, New York, 2013–2023 (N = 44).

Ecological prevalence of Powassan virus

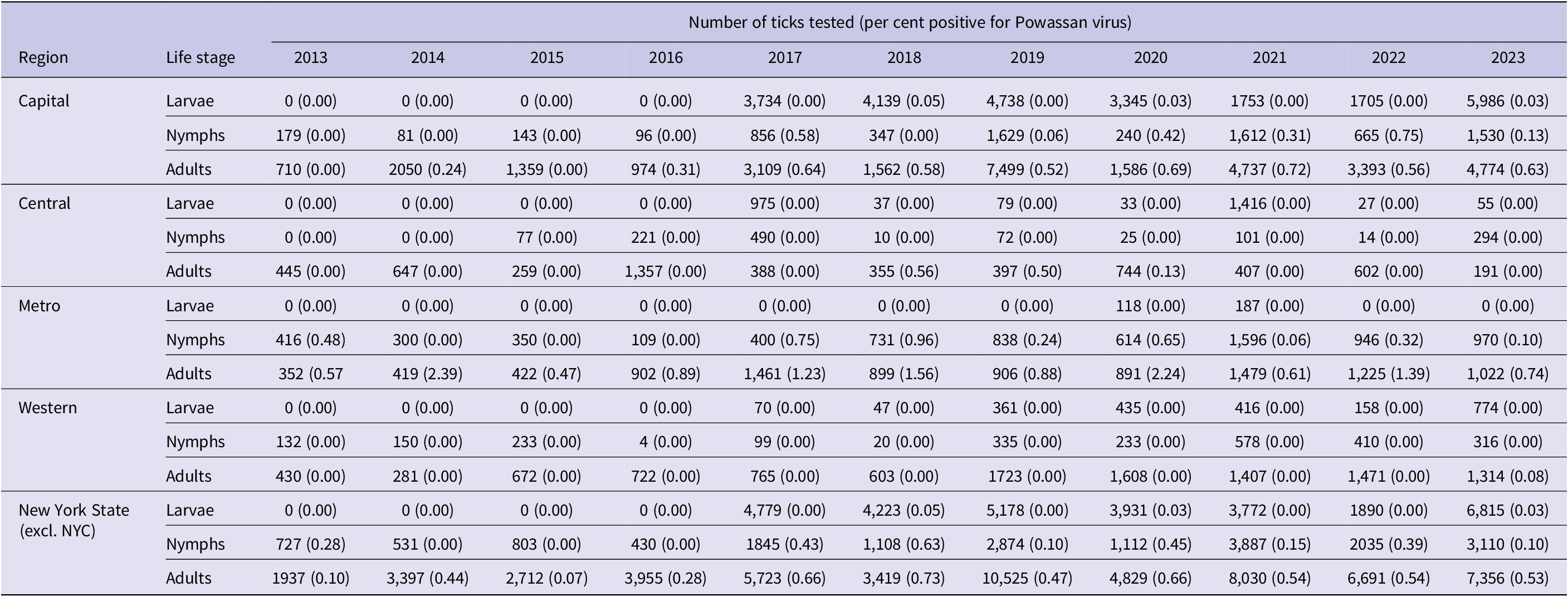

A total of 58,574 adult, 18,462 nymphal, and 30,588 larval I. scapularis were tested in pools for the presence of POWV (POW-1 and DTV) from 2013 to 2023. A total of 292 adult pools (0.50%), 42 nymphal pools (0.23%), and five larval pools (0.02%) tested positive for POWV. Statewide prevalence of POWV increased in larval, nymphal, and adult I. scapularis populations over the study period (Table 4). POWV prevalence in larval I. scapularis increased in only the Capital Region, with an overall statewide increase from 0.00% in 2013 to 0.03% in 2023. POWV prevalence in nymphal I. scapularis increased in both the Capital and Metropolitan regions, with an average yearly statewide increase of 0.0156% over the study period. A linear regression analysis showed that POWV prevalence in adult I. scapularis increased significantly (p < 0.05) statewide over the study period, with increases in prevalence in the Capital, Central, and Western regions. In the Capital Region, linear regression revealed a statistically significant (p < 0.002) increase in POWV prevalence in adult I. scapularis, from 0.00% in 2013 to 0.63% in 2023. Site-level ERI ranged from 0 to 8 in nymphs and from 0 to 22.2 in adult I. scapularis.

Table 4. Prevalence of Powassan virus in larvae, nymph, and adult Ixodes scapularis by New York State region, 2013–2023

Spatial analysis

Spatial analyses were conducted at the ZCTA level, which provides sufficient geographic detail for Moran’s I analyses given the small number of POWV infection cases. Regions are included in spatial figures to summarize broader geographic trends across NYS. Counties were not included in spatial analyses and are presented solely for descriptive purposes when reporting incidence rates (Table 2).

Global Moran’s I analysis identified statistically significant positive spatial autocorrelation among cases of human POWV infection across NYS ZCTAs (Moran’s I = 0.0618, standard deviation = 10.95, p < 2.2 × 10−16), indicating that POWV cases tended to cluster geographically. Local Moran’s I analysis further demonstrated distinct spatial patterns, particularly in the Capital and Metropolitan regions (Figure 1). Out of 1,793 ZCTAs in NYS, 103 (5.7%) had statistically significant local Moran’s I values (p < 0.05), supporting evidence of spatial clustering.

While statistical significance at the local level was limited due to minimal data and low number of POWV cases, clear spatial trends are apparent. When overlaid with entomological surveillance data, the spatial distribution of human cases corresponded closely with areas of elevated adult tick entomological risk index (ERI) (Figure 4). Most human cases occurred in ZCTAs where ERI values fell within the range of 2–4 or > 4. Adult ERI was significantly associated with the incidence of POWV infection at the ZCTA level over the study period (p < 2.2e-16), suggesting that entomological surveillance may be a useful predictor of human POWV infection risk, although the correlation coefficient (Spearman’s p = 0.195) indicates a modest effect size.

Figure 4. Powassan virus encephalitis cases by zip code tabulation area and Ixodes scapularis entomologic risk index (ERI).

Discussion

The basic epidemiological characteristics of POWV infections in NYS are consistent with national POWV infection reports, and comparable to other tick-borne diseases transmitted by I. scapularis. POWV infection, like Lyme disease, babesiosis, and anaplasmosis, disproportionately affects White individuals and males, likely due to differences in behaviour and exposure risk rather than regional population composition [Reference Schwartz22–Reference Gray and Herwaldt24]. Both the hospitalization and case fatality rates of POWV infection in NYS over the study period were slightly lower (90.9% and 11.4%, respectively) than the national rate (92.1% and 13.4%, respectively) over the same time period [25].

The age distribution of POWV infection is bimodal, with peaks occurring in those under ten and over 60 years of age [25]. The higher risk for individuals under ten may be attributed to factors such as increased time spent in grassy or wooded tick habitats as well as reliance on others for tick-checks. Those aged over 60 may face greater risk of symptomatic POWV infection due to decreased immunocompetence and increased likelihood of engagement in outdoor leisure activities like gardening and dog walking [Reference Wilson26]. Like POWV infection, Lyme disease also shows a bimodal age distribution, with peaks in those aged 5–9 and 50–55 years. In contrast, anaplasmosis and babesiosis show unimodal peaks in older adults, likely due to subclinical or asymptomatic expression of these diseases in paediatric populations [Reference Schwartz22–Reference Gray and Herwaldt24].

POWV infection is the only encephalitic tick-borne disease endemic in North America, thus, its symptoms differ from those of other nationally endemic tick-borne diseases [Reference McMinn6]. Encephalitis is the most commonly reported clinical syndrome in patients with neuroinvasive POWV infection, a manifestation seen in less than 1 % of Lyme disease cases and not typically reported in cases of babesiosis or anaplasmosis [20–Reference Schwartz22]. Both the hospitalization and case fatality rates for POWV infection in NYS (90.9% and 11.36%, respectively) are greater than those of anaplasmosis (35.2% and 0.5%, respectively) [Reference Russell23]. National and NY POWV infection fatality rates are higher than national fatality rates for babesiosis [Reference Gray and Herwaldt24,Reference Bloch27].

POWV infection incidence peaks in the summer months (May–July) and in November. The summertime peak of POWV infection aligns with other tick-borne disease, as I. scapularis nymphs, the developmental stage responsible for most cases of anaplasmosis, Lyme disease, and babesiosis, are most active during the summer months [Reference Schwartz22–Reference Gray and Herwaldt24, Reference Lin28]. This finding can be attributed to the difficulty of finding and removing nymphal ticks during the period of ≥12–48 h it takes to transmit Anaplasma phagocytophilum, B. burgdorferi, and Babesia microti, and to increased time spent outdoors in tick habitat [Reference Lin28, Reference Eisen29]. While there are minor seasonal peaks in the incidence of other tick-borne pathogens, such as A. phagocytophilum, in the fall when adult I. scapularis are most active, these pathogens typically require longer attachment times for transmission. In contrast, POWV can be transmitted in as little as 15 min, which reduces the opportunity for tick removal before viral transmission occurs [Reference Feder13, Reference Ebel and Kramer14]. As a result, adult ticks contribute less to the transmission of most other tick-borne diseases as they are larger, easier to detect, and often removed before infection can occur [30]. The November peak in POWV incidence is thus distinct due to its rapid transmission time, reflecting the virus’s unique transmission dynamics compared with other pathogens.

Over the study period, two of the 44 reported cases of human POWV infection were recorded in infants of just 23 days and 1 month old. Cases of infant POWV infection are speculated to have occurred through contact with a tick carried indoors by a household member, pet, or another potential vehicle. Human contact with cats, dogs, and other household pets is known to increase human tick-borne disease risk [Reference Rabinowitz, Gordon and Odofin31]. Pet ownership has been shown to significantly increase the risk of finding ticks crawling on or attached to household members when compared to households with no pets [Reference Jones32]. Pet owners should conduct regular and thorough tick checks on all household members, including pets, to minimize risk of infection.

Higher POWV infection case numbers typically occurred in odd-numbered years over the study period, apart from 2022, during which the peak number of infections across the study period occurred (Figure 5). I. scapularis populations are typically lower across NYS in even-numbered years compared with odd-numbered years due to an I. scapularis population crash in 2010 [33]. This biennial pattern is attributable to the 2-year long-life cycle of I. scapularis ticks. Possible explanations for the heightened POWV infection incidence in 2022 include the general upward trend of POWV infection incidence in NYS, as well as other environmental and ecological factors that may have bolstered I. scapularis populations that year. Notably, precipitation levels across NYS from January to June of 2022 were elevated compared to prior years [34]. Increased early season rainfall may have resulted in favourable conditions for I. scapularis survival and questing activity by increasing humidity, maintaining moist leaf litter, and promoting denser vegetation cover [Reference Leal35]. Further, the growing use of commercial tick-testing panels by healthcare providers, which detect antibodies to multiple tick-borne pathogens including POWV, may result in incidental identification of infections. Such cases may occur in individuals who are asymptomatic for POWV or whose symptoms are attributable to coinfection with another I. scapularis–associated illness presenting with overlapping generalized symptoms [Reference Klontz, Chowdhury and Branda36, Reference Tokarz37]. These incidental detections suggest that a proportion of POWV exposures may be subclinical. Additionally, milder cases of POWV without neurologic involvement may be identified more frequently due to the increased capacity of testing platforms and laboratories performing serologic assays.

Figure 5. Number of reported cases of Powassan virus infection by year of illness onset, New York, 2013–2023 (N = 44).

To better understand the emergence and distribution of POWV in NYS, it is important to consider the broader ecological and environmental factors influencing its transmission and dispersal. The distribution of I. scapularis is associated with the availability of suitable habitat as well as the abundance of preferred hosts such as the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) [Reference Vogels11, Reference Spielman38]. During the 1800s, deforestation and decreases in white-tailed deer populations reduced populations of I. scapularis in the Northeastern US [Reference Spielman38, Reference Lee39]. The subsequent rise in POWV disease in the northeastern US, like other I. scapularis-borne infections, likely followed the re-establishment of I. scapularis ticks after reforestation and the rebound of white-tailed deer populations in the 1900s [Reference Eisen, Eisen and Beard12, Reference Spielman38]. These ecological changes may have also increased contact between hosts and the canonical POWV vectors I. cookei and I. marxi. Overall, vector population growth in NYS has mirrored trends in the Northeast, with substantial increases in I. scapularis nymph populations over time, particularly in the southeastern portion of the state [33, Reference Tran40].

Spatial assessment of the emergence of POWV indicates that the rise in POWV infections as well as prevalence of POWV in tick populations is not occurring uniformly across NYS. Instead, spatial clustering of cases and elevated ERI values demonstrate areas of high-risk in both the Capital and Metropolitan regions of NYS (Figure 4). Like POWV, the emergence of anaplasmosis and babesiosis in NYS have also been focalized, with anaplasmosis occurring primarily in the Capital region and babesiosis primarily in the Metropolitan region [Reference Russell23, Reference O’Connor41]. These patterns of emergence are also consistent with the early geographic expansion of Lyme disease, whose early focal area was the southeastern portion of NYS [Reference Chen42].

Even in the absence of strong local statistical significance, the observed spatial clustering of POWV infection cases in the Capital and Metropolitan regions of NYS likely reflect underlying ecological factors and virus transmission dynamics. However, specific factors driving localized emergence of POWV remain poorly defined, highlighting a gap in our understanding of the ecological and environmental factors which sustain POWV.

Additionally, the transmission dynamics of POWV are complex, involving horizontal transmission between ticks and hosts, as well as vertical transmission between adult ticks and their offspring, and co-feeding transmission, where infected ticks feed near uninfected ticks on the same host [Reference Lange43]. These transmission mechanisms can sustain and amplify POWV in localized tick populations, potentially leading to focal areas of high infection prevalence. Explorations of the dispersal history of POWV and its transmission foci suggest that POWV is maintained in highly localized transmission foci, which could in part explain spatial clustering of high ERI values and human POWV infections in NYS [Reference Vogels11, Reference Robich44]. While the relatively low number of confirmed human cases of POWV infection limits statistical power for analyses like the local Moran’s I, spatial clustering can still be investigated. The observed number of cases in ecologically suitable areas suggest predictable patterns of virus transmission. These are likely shaped by focal tick infection dynamics, host availability, and additional landscape factors that facilitate human exposure to I. scapularis ticks in the Capital and Metropolitan regions of NYS.

Notable limitations in our methodology include host-seeking tick sampling differences by location, differences in vector surveillance activities across NYS regions, repeated sampling at some sites while not at others, and an overall increase in surveillance over the study period. A subset of tick collection sites was also selected based on reported POWV cases, which may introduce bias in local ERI values and observed spatial clustering. While most sites were selected independently based on tick-habitat suitability, we note this as a potential limitation in interpreting spatial clustering results. Additional limitations include the likely underestimation of the incidence of POWV infection due to subclinical and asymptomatic cases which may have been unreported over the study period. The level of awareness of tick-borne disease among health care providers and in the general public likely varies across NYS. Differences in behaviour, diagnosis, and reporting make accurately estimating the burden of POWV infection challenging. The lack of awareness surrounding emerging tick-borne diseases like POWV infection allows for the neglect of co-infection testing by healthcare providers, as well as the potential for undiagnosed cases. This contributes to less accurate case counts and difficulty elucidating the true incidence of POWV infection across NYS.

The assessment of POWV infection epidemiology along with POWV surveillance efforts allows us to identify high-risk populations and anticipate future risk of POWV infection. This enables public health efforts, such as educational messaging, to be targeted toward populations who are at the highest risk. Educational messaging stressing the use of permethrin-treated clothing and gear, appropriate repellent use, carefully checking pets for ticks, and avoidance of tick habitat for those engaging in outdoor activities or living in high-risk areas can help to reduce the risk of POWV infection. Furthermore, messaging can be targeted toward healthcare providers to increase awareness surrounding tick-borne diseases like POWV, with an emphasis on testing for co-infections in patients presenting with tick-borne disease symptoms. This can help us to better understand the overall burden of tick-borne diseases, including POWV infection, and their changing trends in incidence over time.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, the New York State Department of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, and county, town and village park managers for granting us use of lands to conduct this research. We extend gratitude to the following individuals and groups for their assistance in collection, identification, and/or preparation of tick samples for molecular testing: Lee Ann Sporn and the students of Paul Smith’s College, Jake Sporn and the boat launch stewards of the Adirondack Watershed Institute, NYSDOH employees Alexis Russell, Elyse Banker, JoAnne Oliver, John Howard, James Sherwood, Rich Falco, Vanessa Vinci, Ashley Hodge, Dowd Naik, Tela Zembsch, Jamie Haight, Nicholas Piedmonte and Marly Katz, and student interns: Sarah Smolinski, Elizabeth Kincaid, Anna Perry, Rachel Reichel, Sandra Beebe, Donald Rice, Thomas Mistretta, R.C. Rizzitello and many others, Melissa Fierke and associates with the State University of New York (SUNY) College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Claire Hartl and others from SUNY Brockport, Niagara County DOH, Suffolk County DOH and Suffolk County Vector Control. The first author is grateful to the mentors and staff at NYSDOH for their guidance and collaboration throughout the internship. We would also like to thank Amy B. Dean and Rene C. Hull for their contributions to POWV diagnostic testing in the Virology Laboratory at the New York State Department of Health, Wadsworth Center, and Jamie Sommer for compilation and cleaning of epidemiological data.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: A.R.V., M.A.P., J.W.; Formal analysis: A.R.V., C.O.; Investigation: A.R.V., M.A.P., C.O., J.G.M., L.T., J.S., A.F.P., A.P.D., A.T.C., K.C., L.A.J., K.H., W.T.L., J.W.; Resources: M.A.P., A.F.P., A.P.D., A.T.C., K.C., L.A.J., K.H., W.T.L., J.W.; Supervision: M.A.P.; Visualization: A.R.V., C.O.; Writing –original draft: A.R.V.; Writing – review & editing: M.A.P., C.O., J.G.M., L.T., J.S., A.F.P., A.P.D., A.T.C., K.C., L.A.J., K.H., W.T.L., J.W.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Funding statement

Funding was provided by the Association of Public Health Laboratories Internship Subaward Program to the NYSDOH Wadsworth Center from US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Cooperative Agreement #NU60OE000104). The article processing charge (APC) was supported by Northeastern University. Active tick surveillance was supported by the NYSDOH, the National Institutes of Health (grants AI097137 and AI142572) and the CDC (award U01CK000509) and the CDC Emerging Infections Program TickNET (Cooperative Agreement NU50CK000486). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.