What does it take to imagine, design, and inhabit spaces of experimentation, collaboration, and reflection together? How can situations of this kind be crafted? How do we – design educators, practitioners, change-makers – come in close proximity with each other to create togetherness?Footnote 1

7.1 Introduction

Education is how a society ensures its own future. Education has the potential to bring generations together in the common task of making a future for all. But does it currently do so? In this manifesto I call for a move away from the traditional view of education as preparation for a predictable future towards a model where education equips individuals to embrace a complex, rapidly changing world. I bring a new lens to consider a future-making education. I explore how transdisciplinarity – that is, collaboration across the sciences and arts – can move education beyond siloed thinking and practices. Such ‘compartmentalised’ ways of being, thinking and working lead to prescription and enculturation, whereas transdisciplinarity ensures education becomes more than simply preparing for a predicted future – instead, we can make it together. Making the future is a key aspect of transdisciplinary thinking and enacting, which I discuss in what follows. Transdisciplinary research integrates knowledge across academic disciplines and with non-academic stakeholders to address societal challenges. Whilst there is contested views about such bridging and merging and co-creating of new disciplines, there is broad consensus around seeking to value and integrate the knowledge from non-academic stakeholders. This implies processes of mutual learning between science and society, which embodies a mission of science with society rather than for society. So for the purpose of this manifesto, transdisciplinary is about including the diverse voices beyond the academic to consider ways of addressing the challenges of the day – including the voices of children and families.

The participation of children and young people in transdisciplinary education could be the key to achieving transformative school evolution. But what will the transformation be? Thinking, being and enacting in transdisciplinary education is about reimagining the knowledges and wisdoms that are interconnected. It is about seeing humans as part of nature, rather than separate from, or reified within, it. And it means connecting ideas and cultures and epistemologies that have been historically separated, as well as expanding our definitions of being and knowing.

It’s arguable that the modern world is changing more rapidly than at any other time in history. In education, questions continue to arise about how disciplines shape how we perceive, interact with, and respond to the world, and how we should position different types of intelligence at the centre of schooling. Do we arrange knowledge and ways of knowing into silos (e.g. English, maths, geography), or is knowledge more interwoven? Research on transdisciplinary practices challenges the notion that disciplines are separate, and calls for new approaches that transcend traditionally defined disciplinary practices. Teaching has always been a complex task; however, today, working in schools is a highly complex, sophisticated and stressful endeavour. In a fast-changing world, are our education systems and school-based practices changing at similar pace? As the production of knowledge is being destabilised and deconstructed, the classic academic divides between human, social, technical, medial and natural sciences are being disrupted. In a world in which the direction of globalisation is uncertain, and climate change is requiring greater collaboration across nations and peoples, what does this mean for domain-specific skills and knowledge, and transdisciplinary education? What does it mean for teachers and learners reimagining the world and our placed within it? How will it affect our ability to foster creative teaching and learning? Put simply, it is no longer sufficient to teach and learn in single disciplines and subject-specific domains.

7.2 From Disciplinary to Transdisciplinary

Disciplines dominate the educational landscape, and teaching and learning still exist within disciplinary boundaries. Disciplines have their own languages, relationships, materials and practical habits. And disciplinary structures and hierarchies are the focus of our curricula, whereby different skills and types of understanding are specified, sequenced and measured by standardised metrics, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment. Consider most exam syllabi, which remain wedded to the notion of subject disciplines with little thought for the interconnections possible with a transdisciplinary way of thinking. Teachers are also affected – trained in, and committed to, discrete disciplinary tropes, languages and practices.

Transdisciplinarity, on the other hand, is a practice that transgresses and transcends disciplinary boundaries, offering us the potential to respond to new demands and imperatives. It does this by decoupling discipline-specific language and knowledge and allowing both to be opened up to new ways of seeing and experiencing. This is more than simply cross-curricular learning and teaching, which has been criticised for not acknowledging the complexities within disciplines and across disciplines. Transdisciplinarity involves a deeper form of disciplinary interpenetration. For example it might involve using the language of dance (movement, flow, choreography) to explore scientific concepts (water, cycles, change, material).

Typically, disciplines are expressed and understood through language. Even the ‘highest’ form of knowledge – the university doctorate – is realised through a long piece of text. However, movement and bodily senses are essential to transdisciplinarity and the development of new forms of relationalities (Bennett, Reference Bennett2010). So, instead of thinking with only language, we can also think about the body and embodying knowledge. Think of a five-year-old child; they are constantly moving – touching, jumping, jiggling, talking, disrupting, falling and so on – and they experience the world through their bodies, not purely in or through language. The problem with our language-focused education is that words have ‘become “numbed” or seem to have “lost touch” with life’ (Bennett, Reference Bennett2010, p. 54). Educational practices usually assume that children learn best about a subject without being in touch (literally) with the real world. However, all things – humans and non-humans, including materials and objects – are in complex and dynamic relational entanglements. When we bring the body to the fore with children, we literally ‘stick together’ and the learning is ‘felt’ differently on the skin (Barad, Reference Barad2007). When we bring a group of ten-year-olds to experience what it might be like in the trenches in the First World War, they have an embodied experience – the knowledge is felt: they smell the damp Earth, they can use their intuition to empathise with those soldiers far away from home, they can imagine the living conditions. It is a different experience to a teacher setting a task to ‘write a letter about being in the trenches’. This body-focused process is amplified through transdisciplinarity. For example, when we bring the sciences and arts together, and we bring scientists and artists together, classic discipline boundaries are transgressed and transcended; new and shared language evolves, and education moves beyond siloed practices of prescription and enculturation.

At the root of transdisciplinarity is the idea that knowledge, understanding and intelligence come in many forms (see Burnard and Loughrey, Reference Burnard and Loughrey2022). Creativity, imagination, play, making, culture, thinking and so on are not fixed and clearly defined. And hegemonic and hierarchical traditions of creativity (usually Western, heroic, individual, exceptional, male and white) can and ought to be challenged. To teach for diverse creativities – transgressing and transcending disciplinary boundaries – the teacher has to consider which creativity is being developed.

What do these transdisciplinary creativities look like? And how might they stimulate new ways of thinking, as well as foster closer collaborations between teachers and students? In the next section, I focus on the sciences and the arts: exploring how can they connect and stimulating different forms of logic, rationality and affect – constituting a form of an inquiry that is rooted firmly in the world, not just the school or classroom (Burnard and Colucci-Gray, Reference Burnard and Colucci-Gray2020; Burnard and Loughrey, Reference Burnard and Loughrey2022).

7.3 The Possibilities of Transdisciplinary Creativities Education

To understand the overlaps between the sciences and the arts is – by definition – to question existing subject silos. We must find new ways of understanding disciplines – not simply as vehicles for acquiring specific knowledge and skills but also as spaces to explore multiple subjects in a shared and collaborative fashion (Burnard et al., Reference Burnard, Colucci-Gray and Cooke2022). This is a creative act. We must depart from the traditional view of ‘siloed’ education to engage in a creative process of destruction and co-construction. We must imagine a transdisciplinary form of education in which students and teachers collaborate in knowledge production.

I propose a post-human transdisciplinary manifesto. Post-humanism recognises the value of non-human objects, and it posits that human and non-human agents and objects cannot be understood separately but rather are entangled. A post-human transdisciplinary way of thinking could act as a catalyst, expanding our educational values and practices and leading us towards truly holistic learning. I suggest that we push against the conventional divisions: sciences ‘versus’ arts, human ‘versus’ non-human and culture ‘versus’ nature. A commitment to a post-human view of the world challenges human exceptionalism and sees ‘culture’ and ‘nature’ as inseparable. We, too, are dirt made flesh; iron made blood; water made tears, sweat and urine.

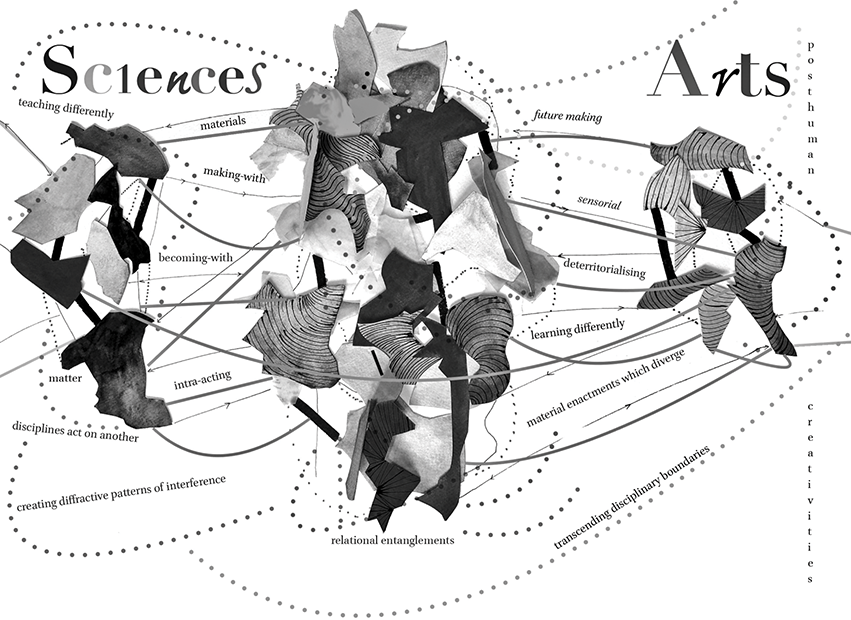

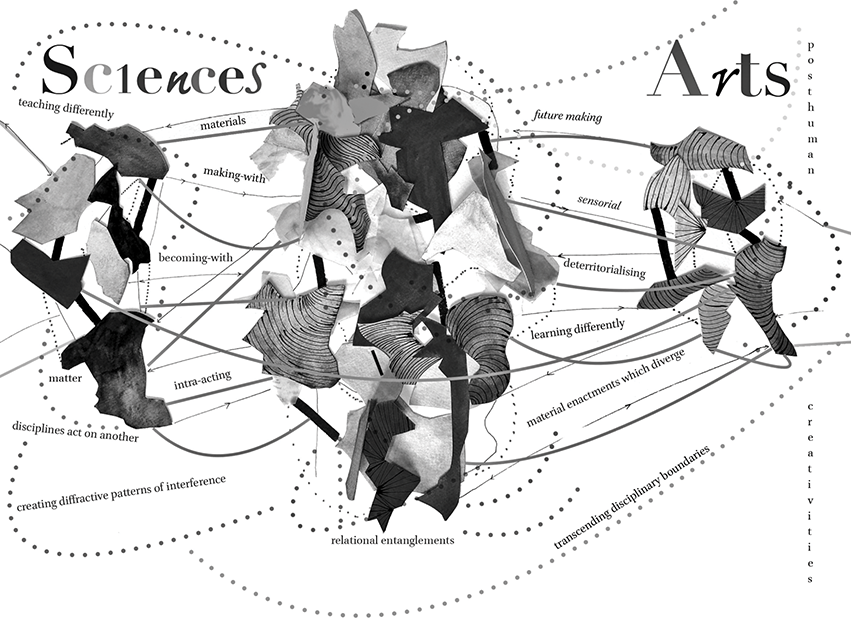

In Figure 7.1, I present a different way of seeing the relationship between the sciences and the arts. It is what Anna Hickey-Moody (Reference Hickey-Moody, Hickey-Moody and Page2016, pp. 173–174) calls rhizomatics – or a network of relations – which, she says, ‘draw on multiple fields and … piece together multiple practices … and practical arrangements that initiate change’. To make a rhizome is to generate questions, pull things apart to see how they work and put them together again in a different way to see what else they can produce or how they might generate inspiration. This ‘rhizomatic of transdisciplinary practice’ or a ‘manifesto poem’ is intended to inspire, to invite curiosity; it is an example of science–arts boundary crossing. Enacting new transdisciplinary combinations and/or pairings of subject disciplines, creating new paths and new ‘rhizomatics’ of practice, involves professional collaboration. As Tim Ingold (Reference Ingold, Burnard and Colucci-Gray2020, p. 438) asks, ‘What knowledge do we need for future-making education? … Such education, rather than teaching us about the world, allows us to be taught by it.’ Some of these knowledge-making practices and material enactments are featured in Figure 7.1 as ‘lines of flight’. These lines interfere and show the complexities between subjects, just as there is complexity between humans and environments.

Figure 7.1 A rhizomatic of transdisciplinary practice. A non-linear, boundary-crossing constellation of routes into transdisciplinary practice is depicted as intersecting lines of flight that are co-produced in and through matter and where all things (humans and non-humans, including materials and objects) are experienced in complex and dynamic relational entanglements.

Figure 7.1Long description

There is a collection of different scraps of fabric in the middle. To the left is a smaller pile of fabric scraps labelled ‘Sciences’. Various lines, some dotted, some arrows, some thicker, connect and encircle the piles of fabric. Some of the lines are labelled, in no particular order, with annotations: teaching differently, materials, making-with, becoming-with, matter, intra-acting, disciplines act on another, creating diffractive patterns of interference. To the right is a smaller pile of fabric scraps labelled ‘Arts’. Various lines, some dotted, some arrows, some thicker, connect and encircle the piles of fabric. Some of the lines are labelled, in no particular order, with annotations: future making, sensorial, deterritorialising, learning differently, material enactments which diverge, transcending disciplinary boundaries. In the middle is the annotation: relational entanglements. To the right of the Arts pile is the vertical label: posthuman creativities.

Rhizomatics are an invitation for you to think, act and read differently. Readers are invited to reimagine, rethink and review what happens in the classroom, in learning and between adults and children. Rhizomatics invite the reader also to engage in (re-)viewing, (re-)framing and (re-)doing transdisciplinary practice that breaks away from traditional practices of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) or STEAM education (where the A represents the arts), to create new paths and new practices, using diverse creativities to achieve ‘new normal’ in learning and teaching in the twenty-first century. The reader could start by asking themselves, What knowledges are being taught? How are they being taught? What is the learning journey and what are the reasons for choosing this particular journey? Where is the knowledge siloed and where can it/they be disrupted? This is an invitation to you to think, act and read immersively. How? Readers can read with a certain sense of resistance but also an openness to departures from conventional practice. It is an invitation to think, act and read reflexively by shifting attention to new pedagogies by decoupling the language of a discipline from its original context. My proposal is that in thinking differently about knowledge and transdisciplinary knowledges, we transcend our previous assumptions, views, attitudes and ways of life to consider the new – towards future-making mindsets that ask, ‘What if?’

7.4 Stimulating New Thinking and Practices of Future-Making through Transdisciplinary Education

This manifesto was written against a background of global environmental and political turmoil. Daily reports on the impact of climate change on soils, on biodiversity and on sea levels are challenging what is known and assumed to be good and true about the world. In this manifesto, I am concerned with how education across the arts and sciences can move beyond ideas of prescription (where education is viewed as preparing for a future which may be predicted or expected). Future-making in education is what fuels this manifesto – enabling people and communities to respond resourcefully and creatively to ongoing changes. In this context, transdisciplinarity is not a site of disciplinary multiplication – that is, making new disciplines – but rather a practice which transgresses disciplinary habits, learnt responses and defined boundaries; a relational space in which humans and non-humans (materials, environments) are inter-reliant with each other, neither being more important than the other but entangled in practices of discovery and making.

This transdisciplinary manifesto pays particular attention to three interrelated concepts: (1) making-with, (2) materiality and (3) enacting learning differently. I take each in turn. Making-with engages humans and non-humans in intra-action with material objects. The term making-with was coined by Donna Haraway (Reference Haraway2016, p. 58). It is a pedagogical construct for enacting transdisciplinary practices, involving diverse materials, objects, bodies, instruments, tools, technologies and environments (Barad, Reference Barad2007). This is different from ‘learning about’. It is about connecting with others, about physically making and being aware of the complexities of learning in the same way as Figure 7.1 shows the complex relationships between two subject disciplines. The second is materiality. This refers to the materials that matter in learning. The term materiality can also refer to objects and things and also applies to the materiality of a person, of laughter, of an object and of an environment. Materiality includes ‘the capacity of things – edibles, commodities, storms, metals … to act as quasi agents or forces with trajectories, propensities, or tendencies of their own … to articulate a vibrant materiality that runs alongside and inside humans’ (Bennett, Reference Bennett2010, p. viii). These forces are a source of action that can be either human or non-human. Thinking in a material way brings out practices that are not easily codified into view (Sorensen, Reference Sorensen2009). Thirdly, enacting learning in a material way provides the possibility for viewing learning differently and for challenging as well as complementing, established forms of learning, as for multiple creativities. It disrupts teachers and student by creating conditions for new ways of being, thinking, and enacting (Aberton, Reference Aberton2012). Recognising that our relationship with the physical world, and how we engage with it, impacts how we learn. All of this opens up a new way of knowing, being and doing future-making education that displaces acquired habits and perceptions and enables our students to seek new insights into the nature of a world that continually changes.

The sense of making is an important one. By making-with, we recognise that nothing makes itself – we are in a constant state of ‘becoming’ with materials, environments, bodies and constructs. This is countercultural in a world that seeks security and definitive answers. Making-with requires a process of ‘re-seeing’ ourselves not only with(in) the world, but in the making of educational futures. Being open to the world’s aliveness – literally being in touch with its material and affective configurations and reconfigurations – invites material enactments: our using and remaking of materials, resources, people and so on through teaching and learning. If this seems obvious, consider how much making takes place in most classrooms, relative to how much time is spent speaking, writing and thinking. More material enactments could allow for new thinking about the way we construct knowledge.

I am suggesting that we move away from the idea that meaning is exclusively made with the symbols of verbal and written language. Could a doctorate involve a performance of new science knowledge rather than the presentation of 80,000 words of text, for example? Transdisciplinary education brings the material back to the forefront of knowing and knowledge, making the case that the material world and the thinking (or symbolic) world are inextricably entangled, as are sciences and arts. For example, in a Scottish project called ‘STEAM gardens’ (Gray, Colucci-Gray and Robertson, Reference Gray, Colucci-Gray, Robertson, Burnard and Loughrey2022, p. 146), ‘STEAM’ refers to the synergies that can be created from ‘the dialogue and interpenetration amongst previously distinct subjects’. The authors draw on the particular nature of the garden as both art and science, ‘thus affording the opportunity for a plurality of educational experiences supporting an array of diverse creativities’. They go on to say that ‘a garden can be known scientifically through the classification of plant and animal species and their particular properties and behaviours. However, the garden can also be known qualitatively for its artistic aspects, recognising that colour, pattern and design are integral dimensions of the garden’s own creative way of responding to the environment in which it takes its own form’ (p. 159). The meaning we make of the world is created through our relational material enactments, or the ‘doing’ of learning. This demands a shift from ‘knowing’ as the acquisition of specialised knowledge, to ‘knowing’ through the mutual relationships – relationships between the child and the material of the garden, between the living and non-living material of the garden, and between the garden as a whole and the gardener.

By extension, we need to stop regarding the arts and sciences as separate or even separable endeavours. They are connected in the complex ways I demonstrate in Figure 7.1. The material enactment (or doing learning) – in this case, merging or intra-connecting the arts and sciences – is made possible through transdisciplinary dialogue between human and non-human.

7.5 So, How Can We Co-Author the Bringing Together of Sciences and Arts?

Political, social, environmental, human and personal certainties have been disrupted in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a growing sense of helplessness and cynicism across the globe. Within professional learning communities, this transdisciplinary manifesto is a call for experimentation, imagination and transformation: a call to think differently, immersively and reflexively. To do this, we need to believe in the potential of multiple creativities – and particularly transdisciplinary creativities – to shape how we conceive curricula, teacher training and development. While I appreciate the usefulness of established rules – the norms and conventions of our fields and disciplines – we have to destabilise the boundaries between the sciences and the arts and, in so doing, enrich them both.

As I end this manifesto, I will resist giving statements about what to do – to define the disciplines. Rather, I ask questions to bring further disruption. How can leaders model transdisciplinarity? How do they show uncertainties and vulnerabilities? How do they respond to challenges and changes? Where are the opportunities to ask questions about the purpose of schools, and how do schools navigate the choppy waters of government policy? At a systems level, how do teachers and school leaders imagine new languages for their work? Is there a documented and shared choreography of a school development plan? What would this involve? Where can we teach collaboratively across disciplines? Finally, at an individual level, how do we all empower ourselves to reimagine anew? Again and again?

There is a vulnerability in leaping forward into the unknown, but such leaps are full of potential, whether they end up in failure or a tentative grasping of something genuinely new. This requires some unlearning. This demands courage. Transdisciplinary education draws its very strength from not knowing in advance. Boundaries do not sit still.

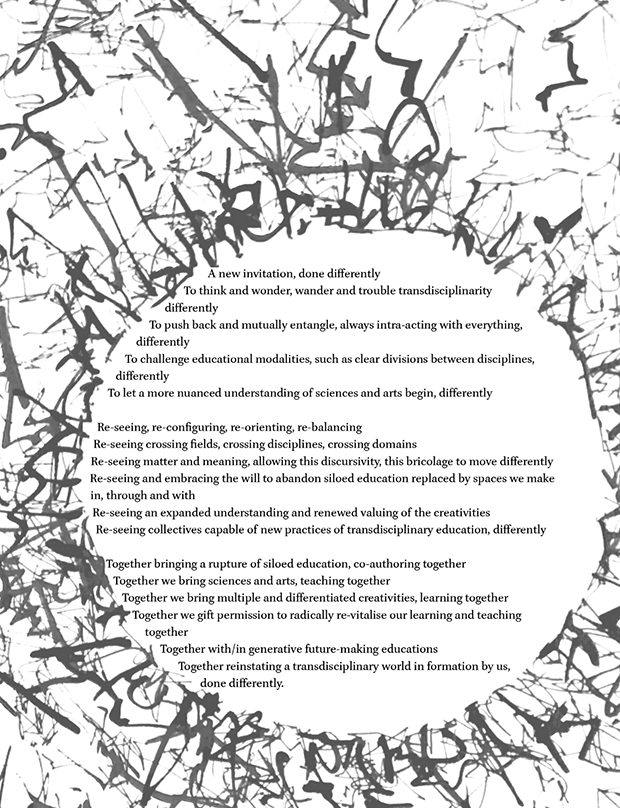

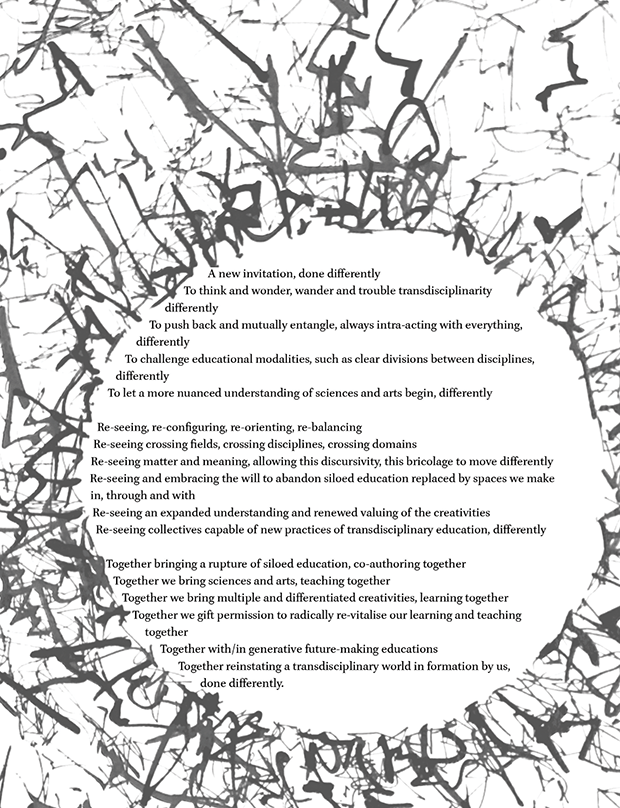

In ending with a manifesto poem, I take the lead from Tim Ingold (Reference Ingold, Burnard and Colucci-Gray2020, p. 124), who argues for educating creativities that move away from the consumerist focus on novelty and final products, as well as internal and intellectualist notions of creativity, to one in which ‘the wellsprings of creativity lie … in their attending upon a world in formation’. So, what this manifesto heralds anew is given in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.2Long description

A manifesto poem for re-visioning transdisciplinary future-making education

A new invitation, done differently

To think and wonder, wander and trouble transdisciplinarity differently

To push back and mutually entangle, always intra-acting with everything, differently

To challenge educational modalities, such as clear divisions between disciplines, differently

To let a more nuanced understanding of sciences and arts begin, differently

Re-seeing, re-configuring, re-orienting, re-balancing

Re-seeing crossing fields, crossing disciplines, crossing domains

Re-seeing matter and meaning, allowing this discursivity, this bricolage to move differently

Re-seeing and embracing the will to abandon siloed education replaced by spaces we make in, through and with

Re-seeing an expanded understanding and renewed valuing of the creativities

Re-seeing collectives capable of new practices of transdisciplinary education, differently

Together bringing a rupture of siloed education, co-authoring together

Together we bring sciences and arts, teaching together

Together we bring multiple and differentiated creativities, learning together

Together we gift permission to radically re-vitalise our learning and teaching together

Together with or in generative future-making educations

Together reinstating a transdisciplinary world in formation by us, done differently.