Suicide is a major public health concern that takes around 700 000 lives globally every year. 1 It is among the leading causes of death worldwide, accounting for more than one in every 100 deaths. A comprehensive and coordinated response to suicide prevention is critical to ensure that the tragedy of suicide does not continue to cost lives and affect millions through the loss of loved ones or suicide attempts.

Improved survival after cancer treatment has heightened the need for better insight into issues of cancer survivorship and quality of life. Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2 Given the unprecedented increase in the number of cancer survivors, there has been an emphasis on long-term and late psychosocial and health-related consequences among this population.

A diagnosis of cancer itself can be a stressful and life-threatening event that causes high levels of physical and psychological devastation, even in patients with early-stage and curable disease. Recent studies have suggested that new cancer diagnoses are positively associated with suicide risk, particularly in the months immediately following diagnosis; half of suicides in cancer patients occur in the first 2 years following diagnosis. Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2–Reference Hem, Loge and Haldorsen6 The overall risk is twice that of the general population and can be as much as 13 times the average suicide risk in those newly diagnosed with cancer. Reference Fang, Fall, Mittleman, Sparén, Ye and Adami3 However, despite the increasing survival rate of cancer patients, few studies have examined long-term suicide risk among this population (e.g. 5 years after cancer diagnosis), Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Hu, Ma, Jemal, Zhao, Nogueira and Ji5,Reference Henson, Brock, Charnock, Wickramasinghe, Will and Pitman7 and there has been a lack of research regarding the point at which the increased suicide risk associated with cancer diagnosis among survivors becomes similar to that of the general population. Moreover, most studies have focused on certain cancers (i.e. lung and bronchial cancer, stomach cancer, pancreatic cancer and oropharyngeal cancer); Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Saad, Gad, Al-Husseini, AlKhayat, Rachid and Alfaar4,Reference Choi and Park8 haematologic cancers, despite their unique disease trajectory and treatment burden, have been relatively understudied. Although there have been several reports of an elevated risk of suicide in patients with haematologic malignancies Reference Hem, Loge and Haldorsen6 such as Hodgkin lymphoma, Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Zaorsky, Zhang, Tuanquin, Bluethmann, Park and Chinchilli9 non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Hultcrantz, Svensson, Derolf, Kristinsson, Lindqvist and Ekbom10 multiple myeloma Reference Hultcrantz, Svensson, Derolf, Kristinsson, Lindqvist and Ekbom10 and leukaemia, Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Yu, Cai, Huang and Lyu11 the studies in question were limited in scope, lacking long-term follow-up Reference Hultcrantz, Svensson, Derolf, Kristinsson, Lindqvist and Ekbom10 or detailed stratification by cancer subtype. Reference Hem, Loge and Haldorsen6 Thus, in the present study, we aimed to assess suicide risk across different cancer types, including haematologic cancers, to identify vulnerable groups requiring targeted interventions.

Previous studies on the increased risk of suicide in cancer patients have been mostly based on standardised mortality ratios. Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Saad, Gad, Al-Husseini, AlKhayat, Rachid and Alfaar4–Reference Henson, Brock, Charnock, Wickramasinghe, Will and Pitman7,Reference Zaorsky, Zhang, Tuanquin, Bluethmann, Park and Chinchilli9,Reference Yu, Cai, Huang and Lyu11,Reference Michalek, Caetano Dos Santos, Wojciechowska and Didkowska12 However, the standardised mortality ratio between a cohort and a reference population can be biased if the cohort and population differ not only with respect to the measured exposure of interest but also with respect to other unmeasured factors that influence the outcome of interest. For instance, previous studies did not consider potential confounders such as smoking, Reference Poorolajal and Darvishi13 alcohol consumption Reference Pompili, Serafini, Innamorati, Dominici, Ferracuti and Kotzalidis14 or pre-existing psychiatric disorders, Reference Brådvik15 which can affect the risk of suicide.

In this context, we assessed the risk of suicide among cancer patients compared with age- and sex-matched controls to consider potential confounders. We investigated how suicide risk changed over time after cancer diagnosis, and, specifically, when it became similar to that of the matched controls. We also compared patterns according to cancer type.

Method

Data source and study setting

The National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) in Korea is the single and mandatory universal health insurance system, covering about 97% of the Korean population; the Medical Aid programme, a public assistance programme funded by government subsidies, covers the remaining 3% with the lowest income. The NHIS recommends at least biennial health screening for all insured individuals. This consists of a self-report questionnaire on medical history, current medications and health behaviours, along with anthropometric measurements and laboratory testing. Reference Shin, Cho, Park and Cho16 In addition to health screening results, the NHIS retains an extensive data-set for the entire Korean population, which includes demographic information, medical treatments and procedures, and disease diagnoses according to the ICD-10. We studied a customised NHIS database cohort that included 40% of the Korean population. Participants were selected via stratified random sampling to ensure that the sample represented the Korean population well.

Study population

In this retrospective administrative data study, we identified a total of 171 474 individuals aged ≥20 years and newly diagnosed with cancer between 2009 and 2017. ICD-10 codes C00–96 were used to identify cancers (detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10384), as well as registration in the critical illness co-payment reduction programme for cancer (V193). In Korea, the NHIS provides the critical illness co-payment reduction programme to enhance health coverage and relieve the financial burden on patients with serious and rare diseases. For example, cancer patients pay only 5% of the total medical bills incurred for cancer-related medical care. As enrolment in this programme requires a medical certificate from a physician, the cancer diagnosis was considered to be sufficiently reliable for purposes of our study, as in previous studies. Reference Lee, Kim, Han, Kim, Park and Lee17,Reference Jeon, Shin, Han, Kim, Yoo and Jeong18 The control cohort (n = 857 370) was selected by 1:5 matching based on age and sex of individuals not diagnosed with cancer.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human participants were approved by institutional review board of Soongsil University (No. SSU-202007-HR-236-01). The requirement for written informed consent was waived because anonymous and de-identified information was used for analysis.

Outcomes and follow-up

The end-point of the study was suicide. Follow-up information for vital status and death was ascertained by routine matching of incident cases to the national death registration database from the Korean National Statistical Office. The Korean National Statistical Office also provides detailed guidance on death certification, and around 90% of records are based on death certificates completed by medical doctors. Reference Shin, Ahn, Kim, Park, Kim and Yun19 The national death registration data include date, cause and place of death; age at death; and sociodemographic information. Reference Shin, Ahn, Kim, Park, Kim and Yun19 Suicide was identified by confirmation of an ICD-10 diagnostic code of X60–84, as has been widely used in epidemiologic studies. Reference Kim, Jung, Han and Jeon20,Reference Lee, Shin, Han and Kawachi21 The study population was followed from the health screening date and censored at the date of suicide or at last follow-up (31 December 2021), whichever occurred first.

Covariates

Potential confounders were considered, including age, sex, income level and residential area. In addition, the following comorbidities were included: hypertension (I10–11 with antihypertensive medication or blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg), diabetes mellitus (E10–14 with antidiabetic medication or fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dL), dyslipidaemia (E78 with lipid-lowering agent or total cholesterol level ≥240 mg/dL), cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction (I21–22) and stroke (I63–34)), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J40–47), end-stage renal disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate of <15 ml/min/1.73 m2) and depression (F32–33).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or n (%). The incidence rate of primary outcomes was calculated by dividing the number of incident cases by the total follow-up duration (person-years). Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for suicide were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models to compare cancer patients with age- and sex-matched controls. A multivariable-adjusted proportional hazards model was applied, adjusted for income, place of residence, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, end-stage renal disease and depression. For site-specific cancer analyses, hazard ratios for each cancer type were calculated relative to the same control group used in the overall analysis; thus, age and sex were included as covariates to account for potential residual confounding. Landmark analyses were performed to examine the effects of assuming lag periods of 1, 2 and 5 years (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, potential effect modification by age, sex and depression was evaluated using stratified analysis and interaction testing with a likelihood-ratio test.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA; https://www.sas.com), and a P -value <0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics

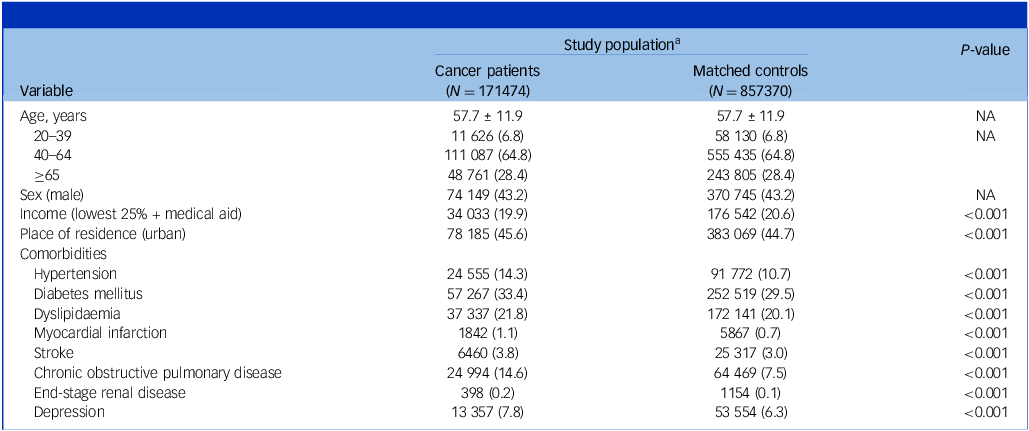

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study participants. The mean age was 57.7 (s.d. 11.9) years, and male individuals accounted for 43.2%. Compared with matched controls, cancer patients were more likely to have higher income, live in an urban area, and have more comorbidities including depression.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of study population

NA, not applicable.

a. Data are expressed as the mean ± s.d. or n (%).

Suicide in cancer patients

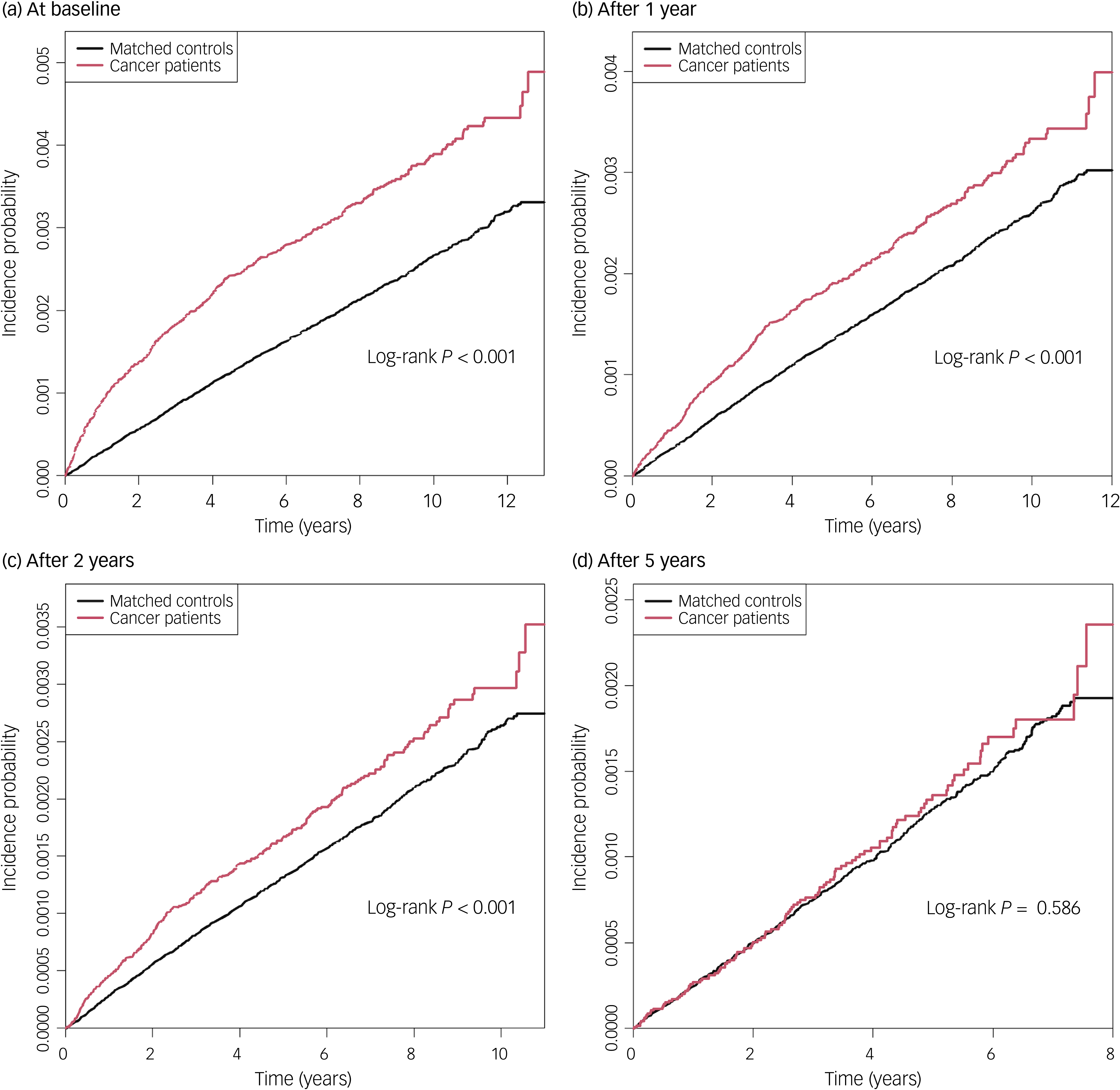

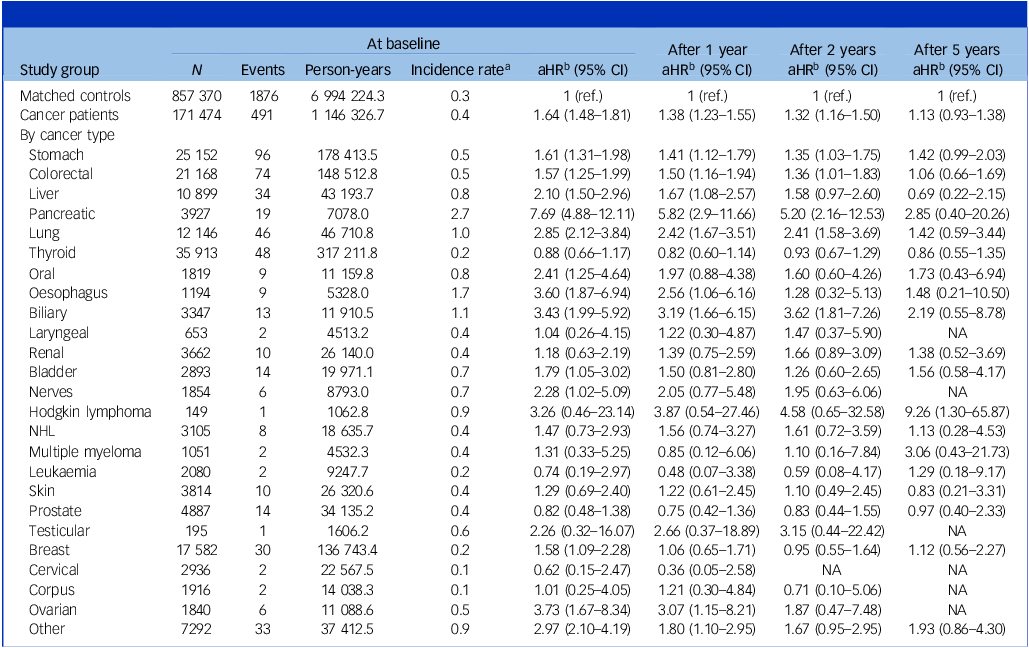

The mean follow-up durations were 6.7 (s.d. 3.7) years and 8.2 (s.d. 2.7) years for cancer patients and matched controls, respectively. In total, 0.3% of cancer patents (491 of 171 474) and 0.2% of matched controls (1876 of 857 370) died by suicide during follow-up, with incidence rates of 0.4 and 0.3 per 1000 person-years, respectively (Table 2). Kaplan–Meier curves showed that the incidence probability of suicide in cancer patients was higher than in matched controls (log-rank P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Cancer patients had a higher risk of suicide (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 1.64, 95% CI 1.48–1.81) compared with matched controls.

Fig. 1 Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of the incidence of suicide in cancer patients compared with matched controls.

Table 2 Risk of suicide in cancer patients according to years since cancer diagnosis

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

a. Per 1000 person-years.

b. Adjusted for income, place of residence, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, end-stage renal disease and depression. Age and sex were matched for overall comparisons and further adjusted for in site-specific models.

Time since cancer diagnosis

In analyses with lag periods, suicide risk remained higher among cancer patients compared with matched controls even with a 1- or 2-year lag period from cancer diagnosis (aHR 1.38, 95% CI 1.23–1.55 and aHR 1.32, 95% CI 1.16–1.50, respectively). After 5 years, there was a downward trend suggesting a gradual decline in suicide risk over time, although this was not statistically significant (aHR 1.13, 95% CI 0.93–1.38).

Cancer type

The risk of suicide was significantly increased in patients with pancreas (aHR 7.69, 95% CI 4.88–12.11), ovary (aHR 3.73, 95% CI 1.67–8.34), oesophagus (aHR 3.60, 95% CI 1.87–6.94), biliary (aHR 3.43, 95% CI 1.99–5.92), lung (aHR 2.85, 95% CI 2.12–3.84), oral cavity (aHR 2.41, 95% CI 1.25–4.64), nerve (aHR 2.28, 95% CI 1.02–5.09), liver (aHR 2.10, 95% CI 1.50–2.96), bladder (aHR 1.79, 95% CI 1.05–3.02), stomach (aHR 1.61, 95% CI 1.31–1.98), breast (aHR 1.58, 95% CI 1.09–2.28) and colorectal (aHR 1.57, 95% CI 1.25–1.99) cancers compared with matched controls. For most solid cancers, including cancers of the head and neck, oesophagus, stomach, colorectal, liver, pancreas and lung, the increased suicide risk was highest shortly after diagnosis and declined over time.

For haematologic cancers, although the difference was not statistically significant, patients with Hodgkin lymphoma exhibited an approximately three-fold elevated risk of suicide (aHR 3.87, 95% CI 0.54–27.46), with a progressive increase over time, reaching a nearly nine-fold elevation beyond 5 years post-diagnosis (aHR 9.26, 95% CI 1.30–65.87; absolute risk difference 1.76 per 1000 person-years, 95% CI 0.06–13.82; Supplementary Table 2). A similar, albeit non-significant, upward trend in suicide risk over time was observed in patients with multiple myeloma and leukaemia. By contrast, no such temporal trend was evident among patients with NHL.

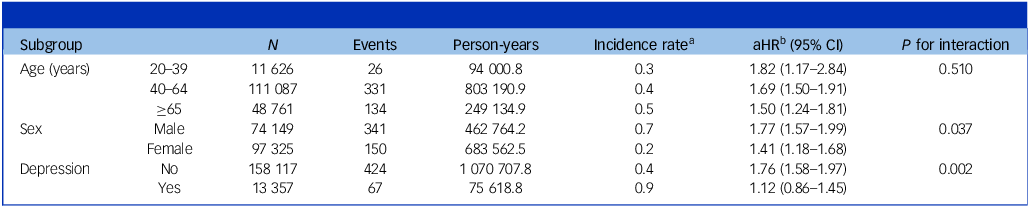

Subgroup analysis

Table 3 shows the results of the analyses stratified by age, sex and baseline depression. Cancer diagnosis remained predictive of higher incidence of suicide in all subgroups compared with matched controls. The association was more prominent in males (P for interaction: 0.037) and those without baseline depression (P for interaction: 0.002).

Table 3 Risk of suicide in cancer patients according to age, sex and depression history

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio.

a. Per 1000 person-years.

b. Adjusted for age, sex, income, place of residence, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, end-stage renal disease and depression, except for the variable used to define each subgroup.

Discussion

The present study revealed that cancer patients had a 1.6-fold higher risk of suicide than matched controls. This elevated suicide risk was consistent with a 1- or 2-year lag period from cancer diagnosis, but the risk also decreased over time and became similar to that of matched controls after 5 years. For patients with solid cancers, the risk of suicide consistently decreased over time, but for those with haematologic cancers, it increased over time. Cancer patients were at higher risk of suicide than matched controls even after various stratifications.

Unlike previous studies that used standardised mortality ratios, Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Saad, Gad, Al-Husseini, AlKhayat, Rachid and Alfaar4–Reference Henson, Brock, Charnock, Wickramasinghe, Will and Pitman7,Reference Michalek, Caetano Dos Santos, Wojciechowska and Didkowska12 our study employed aHRs to account for individual-level confounders, enabling more precise assessment of the independent effect of cancer on suicide risk. Whereas prior research primarily focused on short-term risk (e.g. 6–12 months post-diagnosis) Reference Fang, Fall, Mittleman, Sparén, Ye and Adami3,Reference Saad, Gad, Al-Husseini, AlKhayat, Rachid and Alfaar4 and often did not provide detailed stratification by cancer type, Reference Fang, Fall, Mittleman, Sparén, Ye and Adami3,Reference Saad, Gad, Al-Husseini, AlKhayat, Rachid and Alfaar4,Reference Hem, Loge and Haldorsen6,Reference Choi and Park8 our study incorporated 1-, 2- and 5-year lag analyses, and we conducted cancer-type-specific risk assessments. This approach allowed us to capture the evolving suicide risk trajectory over time and identify long-term elevated suicide risk in patients with specific cancer subtypes, such as haematologic cancers, a pattern that has been relatively overlooked in previous research. In addition, by incorporating absolute risk differences, our study provides more actionable metrics for clinicians and policy makers to evaluate the long-term burden of suicide among cancer survivors.

Previous studies have suggested that the first year after a cancer diagnosis is highly stressful for cancer patients, particularly during the first months. Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2–Reference Saad, Gad, Al-Husseini, AlKhayat, Rachid and Alfaar4 In the present study, we also found that those who were newly diagnosed with cancer were at markedly increased risk of suicide within the first year after diagnosis. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies suggesting that the emotional stress evoked by a cancer diagnosis Reference Fang, Fall, Mittleman, Sparén, Ye and Adami3 and impairment of physical and social functioning caused by treatment Reference Wefel, Lenzi, Theriault, Davis and Meyers22 elevate the immediate risk of suicide.

We found that the increased risk of suicide in cancer patients decreased over time, but the risk remained higher in cancer patients than matched controls for several years. This transition from active cancer treatment into survivorship (12–18 months after diagnosis) is known as the re-entry period. During this period, cancer patients adjust to life after cancer but are commonly distressed about persisting physical and psychosocial sequelae of diagnosis and treatment, changes in previous roles and decreased interpersonal support. Reference Stanton23 A longitudinal study found that survivors experienced more distress upon completion of treatment than at the time of diagnosis. Reference Keesing, Rosenwax and McNamara24 In addition, a second peak in suicide has been reported to occur 12–14 months after cancer diagnosis, due in part to treatment failure or intolerance of treatment leading to distressing emotional responses. Reference Dormer, McCaul and Kristjanson25 These patients feel excluded and abandoned by the healthcare system owing to a lack of treatment, which also increases the risk of suicide.

The suicide risk for cancer patients and matched controls was similar 5 years after cancer diagnosis. A previous study also reported that suicide risk in the cancer cohort decreased with time since cancer diagnosis and was even slightly lower than that of the general population 5 years after diagnosis. Reference Hu, Ma, Jemal, Zhao, Nogueira and Ji5 Although anxiety or depression are most commonly brought to mind when the psychological effects of cancer are considered, late or long-term psychological effects may also include positive responses to cancer diagnosis and treatment. Reference Stein, Syrjala and Andrykowski26 These include enhanced self-esteem, greater life appreciation and meaning, heightened spirituality, and greater feelings of peace and purposefulness. Reference Stein, Syrjala and Andrykowski26 These positive long-term or late effects, further reinforced by a cure diagnosis (typically received 5 years after cancer diagnosis), may have contributed to the decrease in the suicide risk to the level of that of matched controls after 5 years.

Our findings also suggest a higher risk of suicide among patients with potentially aggressive cancer types. Patients with cancer types with a high symptom burden (e.g. cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx, oesophagus, stomach, brain and/or nervous system, pancreas, and lung and bronchus) Reference van den Beuken-van Everdingen, de Rijke, Kessels, Schouten, van Kleef and Patijn27 had a higher risk of suicide at baseline, and the risk decreased with time after diagnosis, consistent with the findings of prior studies. Reference Misono, Weiss, Fann, Redman and Yueh2,Reference Hu, Ma, Jemal, Zhao, Nogueira and Ji5,Reference Henson, Brock, Charnock, Wickramasinghe, Will and Pitman7 On the other hand, suicide risk was not increased in patients with cancers with better prognosis, such as thyroid cancer and prostate cancer. Thyroid and prostate cancers are representative example of overdiagnosis by inadvertent cancer screening in Korea. Reference Ahn, Kim and Welch28

Interestingly, those with haematologic cancers showed an increasing risk of suicide with time since diagnosis and had a higher risk of suicide even 5 years after diagnosis. Although the small number of events for specific haematologic cancer subtypes, such as Hodgkin lymphoma and multiple myeloma, resulted in wide confidence intervals, limiting statistical robustness, suicide risk remained significantly elevated in haematologic cancer patients even 5 years after diagnosis.

Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma had the highest suicide risk among haematologic cancer patients after a 5-year lag period, consistent with recent studies identifying individuals with Hodgkin lymphoma as having the highest suicide rate among cancer patients. Reference Zaorsky, Zhang, Tuanquin, Bluethmann, Park and Chinchilli9 Hodgkin lymphoma is typically diagnosed in early adulthood, particularly in males in their 20s, and is considered to be highly curable with multi-agent chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with cure rates of up to 90% achieved in younger patients. Nevertheless, diagnosis and treatment can be physically and psychologically burdensome, disrupting education, career and long-term life planning. Reference Yang, Zhang and Hou29 Even beyond 5 years, survivors often remain at a life stage at which career and family formation are still in progress, while treatment-related impacts on sexual function and fertility persist. Reference Zaorsky, Zhang, Tuanquin, Bluethmann, Park and Chinchilli9,Reference Yang, Zhang and Hou29 These factors are likely to contribute to the sustained elevation in suicide risk observed in Hodgkin lymphoma patients throughout the follow-up period.

By contrast, although suicide risk among patients with NHL increased over time after diagnosis, it became comparable with that of matched controls by 5 years post-diagnosis. In Korea, extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) is the second most common NHL subtype after diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, accounting for approximately 20% of cases. MALT lymphoma generally has a favourable prognosis, with a 10-year survival rate of 99% for gastric MALT lymphoma, Reference Kim, Park, Lee, Ahn, Kang and Yang30 compared with a 5-year survival rate of 50–60% for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Reference Lee, Park, Park, Ju, Oh and Kong31 The favourable long-term prognosis for a substantial proportion of NHL survivors may explain why suicide risk among NHL patients aligned with that of matched controls beyond 5 years.

An upward trend in suicide risk over time was observed in patients with multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma, an incurable malignancy, places patients at continuous risk of relapse, even after remission. Most patients experience debilitating bone lesions and pain and undergo multiple lines of combination therapy, which result in cumulative toxicities, including neuropathy, haematologic complications and gastrointestinal side-effects, often requiring transfusions and supportive care. Reference Ahmed and Killeen32 In addition, the high doses of corticosteroids included in most multiple myeloma treatment regimens can induce depression and psychosis, further enhancing the risk of suicide. Reference Fardet, Petersen and Nazareth33 Patients with advanced or relapsed multiple myeloma have common complications including renal impairment, immunosuppression and pathologic fractures. Reference Ahmed and Killeen32 These persistent physical and treatment-related burdens may contribute to the observed increase in suicide risk over time following a multiple myeloma diagnosis.

In patients with leukaemia, suicide risk was initially lower than that of matched controls but gradually increased over time. This early reduction may have been due to intensive in-patient care and close medical supervision during initial chemotherapy, along with temporary optimism related to remission. In patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia, for instance, early treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors often induces a rapid clinical response, reducing initial psychological distress. However, as treatment progresses, patients with acute myeloid leukaemia, the most common subtype in Korea, experience high relapse rates and uncertain prognoses, contributing to a sustained emotional burden and social isolation due to immunosuppression. Reference Yu, Cai, Huang and Lyu11 In patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia, the prolonged need for tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy leads to chronic side-effects and diminished quality of life, and the perception of incurability and cumulative treatment-related distress may elevate suicide risk. Reference Shi, Li, Li and Jiang34 Furthermore, the low remission rates for some leukaemia subtypes impose considerable economic and psychological burdens, and factors such as discrimination, feelings of inferiority and depression may increase suicide risk among these patients. Reference Yu, Cai, Huang and Lyu11

Cancer patients were at increased risk of suicide even after various stratifications. As in the general population, Reference Suominen, Isometsä, Suokas, Haukka, Achte and Lönnqvist35 these associations were more prominent in males than in females. Both male and female cancer patients are likely to experience similar problems with respect to quality of life, coping, symptom control and psychological distress, but females may be less inclined to react through self-directed violence. Reference Hawton36 In addition, according to the literature on gender and suicide, male suicide rates can be explained in terms of traditional gender roles. Male gender roles tend to emphasise greater levels of strength, independence, risk-taking behaviour, economic status and individualism. Reference Payne, Swami and Stanistreet37 In Korean culture, males are expected to be the head of their family; thus, disability or unemployment might impose more pressure on males than females. Reinforcement of this gender role often prevents males from seeking help for suicidal feelings and depression. These findings underscore the need for a multifaceted approach that integrates oncology, psychology and social support services to address the heightened suicide risk among male cancer patients. Notably, in this study, patients without baseline depression, who were considered to have a low risk of suicide, had a higher risk of suicide than those with baseline depression. Thus, even among cancer patients without a history of psychiatric illness, attention must be paid to the prevention of suicide.

This study has important implications for both early and long-term cancer survivorship care. Suicide risk increases in the years following cancer diagnosis and may remain elevated even after 5 years, depending on the cancer type. These findings underscore the need to integrate suicide screening and prevention into both acute and long-term survivorship care. Structured mental health assessments, stronger oncology–psychiatry collaboration, and improved access to psycho-oncology resources can be key strategies. For example, the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Canada has successfully implemented the Distress Assessment and Response Tool, an electronic system that screens for distress and suicidal ideation and links patients to triaged psychosocial interventions, leading to improved psychosocial care and reduced suicide mortality. Reference Li, Macedo, Crawford, Bagha, Leung and Zimmermann38,Reference Gascon, Leung, Espin-Garcia, Rodin, Chu and Li39 A similar electronic screening system has also been introduced at cancer centres in Korea, reflecting growing recognition of the need to integrate mental health services into routine cancer care globally.

Our study had several limitations. First, because we used administrative data, we did not have sufficient clinical information on caner stage, histology, treatment modality and intent, or cancer recurrence, which could act as confounders. Second, some suicides may have been misclassified as accidental deaths or deaths of undetermined intent. However, most suicides (more than 70%) are correctly classified; Reference Chan, Caine, Chang, Lee, Cha and Yip40 thus, potential bias from misidentified suicide cases was unlikely to have directly affected the results of this study. Third, although we included baseline depression as a covariate, we did not account for other psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, owing to data limitations. These conditions may contribute to suicide risk, leading to residual confounding. Fourth, although our study quantitatively assessed suicide risk among cancer patients, further qualitative research is needed to explore the lived experiences, psychosocial stressors and coping mechanisms that may contribute to suicide risk. Last, we included only Korean participants; thus, the findings may not be generalisable to other countries or ethnic groups. Further studies in diverse populations would help to assess the broader applicability of these findings.

In this cohort study of cancer patients and matched controls, we found that suicide risk was higher among patients than among matched controls. Suicide risk in cancer patients tended to decrease over time but remained higher than that of matched controls 2 years after cancer diagnosis. Moreover, those with haematologic cancers faced a higher suicide risk than matched controls even 5 years after diagnosis. Screening and tailored social and psycho-oncologic interventions are needed for suicide prevention in this vulnerable population.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.10384

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were assessed under licence for the current study and so are not publicly available. Data are available at https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr/bd/ay/bdaya001iv.do with the permission of the Korean NHIS.

Author contributions

J.E.Y., K.H. and D.W.S. contributed to the conception and design of the work; J.E.Y., J.H.J., K.H. and D.W.S. contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; J.E.Y. and D.W.S. drafted the manuscript, and J.E.Y., W.J., J.H.J., S.E.Y., J.H.A., K.H. and D.W.S. critically revised it. All authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.