Introduction and motivation

Political science is today a well-established and institutionalised discipline that covers large parts of the world (Norris Reference Norris, Boncourt, Engeli and Garzi2020). Political scientists are active in many countries, and their work spans a wide range of empirical contexts and topics. However, we also know from previous studies that not all countries are equally well-covered in political science studies, and that the presence of the discipline varies between national contexts (Capano and Verzichelli Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023; Wilson and Knutsen Reference Wilson and Knutsen2022). In this article, we investigate the latter variation, focusing on how the presence as well as different features of political science departments relate to the political circumstances, and more specifically the regime type, of the host country.

Political science concerns topics that politicians should and do care about (Goodin Reference Goodin2011; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2014). The primary motive of politicians might be to realise some ideological vision, such as building a well-functioning democracy or comprehensive welfare state, or it may simply be retaining office, be it through winning elections in democracies or repression or co-optation in autocracies. Regardless, political science research offers knowledge that may, in principle, be used to more effectively achieve these aims (Capano and Verzichelli Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023; Goodin Reference Goodin2011). There is also a flip side of the coin. Various political science insights – for instance, how to organise mass protests or effective opposition parties – could be used by other actors, such as civil society organisations or opposition party members, to stop politicians in office from achieving their goals. Likewise, educating large cohorts of political scientists could carry rewards and risks for governing politicians. On the one hand, a large army of well-trained (potential) bureaucrats and diplomats might make state building and effective policy implementation easier for, say, a newly elected leader of a developing democracy. On the other hand, a large reservoir of students and young graduates who have internalised the beliefs and values of normative democratic theory (Capano Reference Capano2025) and have simultaneously read up on the tactics that make street protests more effective is likely far from desirable from the viewpoint of an autocrat with the aim to hold on power. At the same time, establishing and tolerating political science departments, even in nondemocratic countries, can potentially be used to obtain legitimacy domestically and internationally. The argument is similar to the one regarding electoral authoritarianism (see, for example, Miller Reference Miller2020) in that allowing for political science departments can satisfy observers’ normative or prescriptive demands and it might promote regime survival by signalling openness to citizens.

For incumbent politicians, the relative benefits and drawbacks of promoting political science research and education – or promoting such research or education of a particular kind (for example, banning teaching in democratic theory but funding and promoting public administration research) – may well vary systematically across different state and regime contexts. If so, different political factors could shape the development and spread of political science knowledge. This would not only affect the development of the discipline but also have downstream ramifications for political developments in different countries. Similar arguments have been made regarding the expansion of higher education in general, where some scholars have suggested that access to higher education poses an inherent risk to authoritarian regimes (see, for example, Bueno de Mesquita and Downs Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Downs2005; Haass Reference Haass2025), thus incentivising them to restrict it. An alternative argument suggests that autocracies can, instead, actively support and shape the institutions and operations of higher education in ways that enable them to win the allegiance of professors and students through ‘educated acquiescence’; this, in turn, would increase regime stability (Perry Reference Perry2020). If these diverging expectations are relevant for higher education as a whole, they should be especially relevant for political science higher education, because of its focus on the state and questions of power. Thus, politics and political science could be strongly entangled.

In this paper, we focus on the relevance of regime type, and more specifically the democracy–autocracy distinction, for political science research and higher education. We develop and assess different implications of the notion that political motivations shape such research and teaching by analysing the existence and location of political science departments at universities in different countries across the world. We discuss how autocratic incumbents, in particular, may have particularly strong incentives to limit political science research and teaching. And, if they allow these activities, they might combine them with various control strategies, for instance, pertaining to where in the country and at which universities such research and teaching is located. Yet, we also point to a number of factors that should incentivise incumbents – across different regime contexts – to facilitate political science research and teaching, indicating that cross-country differences might, in fact, be limited.

Relationships of the kind that we study in this paper could have implications beyond the individual country, and even for the development of political science as an academic discipline, including the types of theoretical and empirical knowledge it produces. Political science is a global discipline, and its scholars often take aim at understanding political phenomena more generally and independently from where they happen to occur (Norris Reference Norris, Boncourt, Engeli and Garzi2020). However, previous studies have highlighted that the knowledge base of the discipline is unevenly developed in geographical terms, insofar as some countries have been studied much more frequently than others (for example, Wilson and Knutsen Reference Wilson and Knutsen2022). This geographical skew might mean that political phenomena of great relevance to millions of citizens across the world are inadequately described. Moreover, many theories and concepts used in political science are primarily extracted from the empirical knowledge that the discipline has accumulated over time, often based on a handful of cases (most notably the USA). Hence, a geographical skew in empirical knowledge of politics and policy-making may translate into theories and concepts that purport to be general, but have stronger relevance in some countries than others.

Africanists and Asianists, for example, have long highlighted these problems related to core concepts or theories of the state or international relations being developed from western experiences (see, for example, Wilson and Knutsen Reference Wilson and Knutsen2022). Generally speaking, democratic countries have received more attention from political scientists than autocratic ones. This is, for instance, reflected in the extensive focus on political phenomena that are specific to democracies (see, for example, Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2007: 9) but also in more attention being paid to analysing and explaining how phenomena that appear across regime contexts, such as welfare states (see Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2008), work in democracies. One contributing factor to this cross-country imbalance could be a ‘home-bias’ among political science researchers (Wilson and Knutsen Reference Wilson and Knutsen2022), insofar as researchers may prefer or have a better ability (in terms of access to sources or funding opportunities, knowledge of language and history, etc.) to study the countries or regions they originate from or reside in. If more political science researchers are located in democratic countries, this could lead to the knowledge of these countries’ politics being more developed than that of autocratic countries.

In our empirical analysis, we focus on institutions of higher education and their departments of political science. While political science research or teaching may certainly occur in other units such as law departments or interdisciplinary research institutes, political science departments are organised clusters of people researching and teaching political science. They are thus a primary contributing factor to the coverage of political science research and teaching in a city and region (and often the wider country). Moreover, in contrast to smaller pockets of political science teaching and research in other units, having a political science department displays a higher level of commitment and institutionalisation, as department structures are harder to establish and abolish. As noted, the global distribution of political science departments is likely far from random, and we assess how political regime type relates to the existence and number of political science departments in a country, also when accounting for other relevant factors such as population size and economic development (see Almond Reference Almond, Goodin and Klingemann1998; Newton and Vallès Reference Newton and Vallès1991). We further discuss how regime type may shape not only the presence and number of political science departments but also their location geographically (focusing on distance to the capital) or at particular institutions (notably in private versus public universities). To study these relationships, we use data from the World Higher Education Database (WHED; https://www.whed.net), an authoritative dataset provided by the International Association of Universities (IAU). This provides us with information on more than 20,000 higher education institutions across the world. To briefly preview our results, we find surprisingly limited regime differences in the presence or other measurable features of political science departments, and we discuss how our results may reflect mixed political motivations and (recent) formal streamlining of political science higher education across the world.

In the following section, we summarise the literature on political science as a discipline and its development in selected countries, comprising democracies and autocracies. Thereafter, we discuss relevant insights, for instance, from the autocratic politics literature, in regard to understanding the incentives of incumbent politicians to promote or obstruct political science teaching and research in their countries, and the corresponding implications for the existence and location of political science units. The section after that contains an overview of our data and methods before we present our empirical analysis. Finally, we summarise our results and discuss their broader implications, after which we present suggestions for follow-up research.

Political science: A discipline of troublemakers or loyal agents of the state?

The origins of political science can be described in different ways, depending on the criteria that one applies to define the discipline. One widespread notion is that the ancient Greeks – especially Plato with his first typology of political systems in The Republic or Aristotle’s categorisation and empirical mapping of systems in Politics – are the founding fathers of the study of systems of government and thus political science (Almond Reference Almond, Goodin and Klingemann1998). Scholars of the Enlightenment such as Hobbes, Locke, and Montesquieu; US founding fathers such as Madison or Hamilton; and philosophers of the 18th and 19th century such as Hegel, Marx, and Comte are also commonly viewed as early contributors of relevance. However, it was the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century that saw the emergence of political science as a separate discipline, rather than an area of study within law or philosophy. During this time, the study of politics became established at, for example, Oxford and Cambridge, albeit under the label of contemporary history, and the first departments of political science came into existence towards the end of the 19th century (Almond Reference Almond, Goodin and Klingemann1998).

In the USA, several free-standing political science departments had been established by the first decade of the 20th century, and the American Political Science Association (APSA) was formed in 1903. In most Western European countries, political science developed into a self-standing discipline around the same time, albeit with specific national paths of development (for an overview, see Ilonszki and Roux Reference Ilonszki and Roux2019). In general, though, the development of political science in North America and Western Europe was tightly linked, as individuals and ideas would regularly cross borders as well as the Atlantic. This mutual influence culminated in the creation of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) in 1970 with the help of funds from the Ford Foundation (Almond Reference Almond, Goodin and Klingemann1998). Overall, one can say that political science in North America and Western Europe was, at least since 1945, institutionalised as a discipline, and this discipline was characterised by rather stable and steady growth as well as strong transatlantic links.

While the institutionalisation of political science happened first in North America and Western Europe, the discipline became more established in other countries not long after. In China, which we will elaborate on in some detail to illustrate some more general points on the role of politics in non-democratic regime contexts, the first course on politics was taught at the Capital Academy (later Peking University) as early as 1903 (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990). The Chinese Social and Political Science Association was founded in 1915, and a separate Chinese Political Science Association was established in 1932 (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990). In parallel, universities started creating separate political science departments so that, by 1949, around 40 departments existed at Chinese universities.

Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the situation for political science in China changed. With the focus of the Chinese Communist party (CCP) on controlling social knowledge, and following the example of the Soviet Union, which outlawed political science as early as in the 1920s, China abolished political science as an institutionalised discipline in 1952 (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990; Wang and Guo Reference Wang and Guo2019). However, this dynamic was not entirely new: Even during imperial times, whenever the state enjoyed a stronger hegemony over civil society, it limited the space for social science knowledge (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990). During these phases, the state would prioritise the development of technical knowledge, which was seen as a necessity for societal progress, while the development of societal knowledge remained under strict control. A similar dynamic played out during Mao’s Cultural Revolution, when most social scientists were sent to the countryside for labour, and social science research came to a standstill.

After the rise of Deng Xiaoping, science received renewed recognition in China, but the natural sciences received more autonomy than the social sciences (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990; Perry Reference Perry2020; Wang and Guo Reference Wang and Guo2019). Only after some time, and as the government realised that they could be useful in solving societal challenges, the social sciences received more space. Nonetheless, political science research and teaching remained closely monitored by the state. By 1980, the Chinese Political Science Association was (re-)established, coinciding with an opening for academic studies of policies and political institutions, foreign and domestic (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990; Wang and Guo Reference Wang and Guo2019). The realisation that China required various reforms to ensure effective state functioning and decentralised decision-making created a demand for more and better trained civil servants. This, in turn, led to a growing interest in administrative research within political science among CCP officials. In 1983/84, Fudan University and Peking University started enrolling students in political science programmes, and by 1986, more than 10 Chinese universities had set up political science programmes or departments (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990). Yet, following the Tiananmen massacre in 1989, the state ordered many universities to stop enrolment in social science programmes, and many students had to undergo ‘ideological training’ courses before they were allowed to start or continue their studies (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990).

Contemporary work on political science research in China continues to describe similar tensions. For example, research on local politics is considered less sensitive, and is thus more prevalent, than research on the central government (Reny Reference Reny2016). Similarly, there is a continuous tension between ‘westernisation’ and ‘indigenisation’ of political science in China, with debates centring on how applicable ‘western’ political science concepts and ideas are to the Chinese context, or whether a specific Chinese understanding of the discipline is more appropriate (Wang and Guo Reference Wang and Guo2019). These debates relate to the notion, suggested by Perry (Reference Perry2020), that Chinese higher education in general is characterised by ‘educated acquiescence’. This entails that higher education contributes to autocratic persistence, following the successful co-optation of academia, its structures, processes, and graduates through the state. Instead of looking at higher education as a threat, the autocratic regime can actively promote its interests through promoting higher education but then controlling, for example, the content of teaching, career paths of professors, or entry examinations. Similar arguments have been made regarding non-democratic states in general, highlighting that they may strategically use parts of the education system, including primary education, to promote core political interests (for example, Paglayan Reference Paglayan2024).

The tumultuous history of political science research and teaching in 20th-century China is a good – albeit only one – example of the complicated relationship between political science and the state, and how this relationship depends on the shifting political conditions and the perceived benefits and risks to incumbent regime elites. Similar developments can also be observed in Africa, where, following the end of colonial rule, the importance of nation building and training of a capable civil service gave a strong impetus to give political science more attention and space in several countries (Jinadu Reference Jinadu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990). However, the discipline was also perceived as subversive by leading elites, and thus in need of tighter control and limited growth. As a reaction, many countries tended to create separate programmes or departments for public administration or international relations, which were perceived as less troublesome subdisciplines (Jinadu Reference Jinadu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990).

In the last two decades, the discipline of political science has undergone a general debate about its societal and political relevance (see, for example, Capano and Verzichelli Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023; Flinders and Pal Reference Flinders and Pal2020). While there is a perception in parts of the discipline, and even among some outside observers, that political scientists could do a better job of being relevant when it comes to political or societal debates (see, for example, Ostrom Reference Ostrom2000; Putnam Reference Putnam2003), there is no hard proof that political science actually has become or is becoming less relevant (Flinders Reference Flinders2013). At the same time, political science, similar to other disciplines, has been exposed to an international impact agenda (Bandola-Gill, Flinders, and Brans Reference Bandola-Gill, Flinders, Brans, Eisfeld and Flinders2021) through the introduction of incentives to deliver demonstrable evidence of non-academic impact. This has increased the incentives for political scientists to focus on topics that matter for politics, and thus follow the notion of Gerring and Yesnowitz (Reference Gerring and Yesnowitz2006: 112) that ‘[s]ocial science is science for society’s sake’.

To be more specific, data from a large survey of European political scientists, for example, show that around 80% of respondents were engaged in some form of policy advisory activity in the past three years (Brans and Timmermans Reference Brans and Timmermans2022), and studies on the USA highlight the transfer of academics into government and think tanks as a key transmission belt for political science knowledge into government (Flinders Reference Flinders2013). So, it seems that, at the individual level, the interest of political scientists when it comes to providing knowledge that is of relevance for politics is very much present (see also Capano and Verzichelli Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that political science as a discipline produces knowledge that is intended to ‘improve politics’. Politicians, in turn, should presumably be interested in engaging with this knowledge. At the same time, political science has a moral foundation that is clearly pro-democracy (Capano and Verzichelli Reference Capano and Verzichelli2023; Flinders and Pal Reference Flinders and Pal2020). This can give rise to tensions in contexts where these values are not embedded in the current regime or shared by key political decision makers. Thus, the interest in the expertise offered by political scientists should depend on the political environment, and the framing of the issue at hand that might make it more or less compatible with existing values (Brint Reference Brint1990).

Overall, the historical development of political science reflects two general characteristics of the discipline. On the one hand, political scientists are often described as handmaidens to power and the state (Goodin Reference Goodin2011; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2014). They train bureaucrats and diplomats, act as counsellors to rulers or parties, and investigate how power is most effectively employed through a well-functioning state. Especially in situations where the state can co-opt higher education into educated acquiescence (Perry Reference Perry2020), political leaders can ensure that higher education serves their needs without encountering any regime-related risks. On the other hand, higher education, in general, and political science education, more specifically, can promote more critical stances if it is not perfectly controlled. For political science teaching, these critical stances could pertain to lectures and readings that focus on, for example, normatively good and just social arrangements (which may deviate from what students can observe in their country), why executive power should be constrained, or why marginalised voices should be heard (Capano Reference Capano2025; Goodin Reference Goodin2011; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2014). Hence, politicians might sometimes have strong reasons to be sceptical of political science being taught to young citizens in their country. At the same time, tolerating this type of critical and ‘dangerous’ academic teaching and research in nondemocratic contexts, might be used by political leaders as a signal of their openness and tolerance, potentially enhancing their legitimacy domestically and internationally.

The two, at times competing, roots of the discipline can create opposing incentives regarding government support for the institutionalisation of political science, and the relative weight of these incentives may depend on the political-regime context. Thus, when trying to hypothesise about the cross-country distribution of political science departments, existing work on the discipline points us in somewhat contradictory directions. The argument that political science helps run a more effective state suggests that any country, no matter the political regime, should have an interest in having political science departments. In contrast, the argument highlighting political science’s democratic and normative core would suggest that autocratic regimes will be more careful in establishing such departments, given that the content that is taught or researched in them could potentially undermine the regime. In the following, we will expand on this tension and develop specific hypotheses regarding how the existence and other features of political science departments relate to regime type.

Why political science may (or may not) be contingent on regime type

The empirical examples outlined in the previous section point towards a more general observation made by Newton and Vallès (Reference Newton and Vallès1991): The development of political science teaching and research requires organised settings, which, in turn, hinge on the state providing the necessary framework conditions (access to funding, absence of bans and censorship, etc.). When those governing the state are unwilling to provide these conditions, the study of politics will not flourish. However, we have already indicated that the literature offers two somewhat competing arguments about the potential gains and risks associated with the institutionalisation of political science, especially in nondemocratic contexts. Let us detail these two arguments in turn.

The first argument, which sees political science as a handmaiden of the state and a source for training effective bureaucrats and diplomats, highlights gains that come from having political science departments and which are independent of the regime type. The research and graduates produced by political science departments provide knowledge and expertise in various areas that are required for effective governance in different realms – from steering the economy to information control and domestic security to international relations – with the resulting improvement in performance potentially contributing to increased government and regime stability. Even under autocratic regimes, co-optation of higher education by the regime can create framework conditions that turn universities into anchors of authoritarian stability (Perry Reference Perry2020). Following this logic, one would expect that incumbent politicians in democracies and autocracies are interested in establishing political science departments to reap the benefits that the discipline provides, suggesting few systematic differences by regime type. In the extreme – that is, if these concerns are dominant and similar across regimes – the likelihood that universities have political science departments should be independent of regime type.

In contrast, the second argument, which highlights the democratic and normative roots of political science, would lead one to expect differences across regimes. More specifically, without democratic freedoms – notably free speech and academic freedom to select topics of study without political interference – organised political science units may find it hard to thrive. Studies of higher education in general find that some illiberal regimes reduce access to universities especially in humanities and social sciences (Schofer, Lerch, and Meyer Reference Schofer, Lerch and Meyer2022). Political science may be especially prone to such limitations: ‘Perhaps more than any other academic social science, political science is a threat to anti-democratic regimes, which invariably react by trying to close it down’ (Newton and Vallès Reference Newton and Vallès1991: 227). Examples mentioned in the prior section such as China under Mao or Stalin’s Soviet Union are cases in point. The logic of the argument is straightforward: Political science may be seen as a dangerous subject – in terms of questioning regime legitimacy or otherwise destabilising the current regime – by regime elites in undemocratic societies.Footnote 1 The costs of restricting funding or even banning the discipline may thus be viewed as lower than the expected gains from, for example, having well-trained bureaucrats. Since institutionalising a discipline by dedicating a department to it presupposes the (at least tacit) support of public authorities, any ideological aversion against the discipline will likely lead to resistance to its institutionalisation. In particular, the discipline’s history of playing a key role in legitimising democracy after successful transitions from authoritarian rule, as, for example, in Germany (Blum and Jungblut Reference Blum, Jungblut, Brans and Timmermans2022; Newton and Vallès Reference Newton and Vallès1991), further contributes to its ‘image problem’ among many non-democratic governments. Hence, one might expect that universities are more likely to have political science departments in more democratic countries.

The argument above notwithstanding, limiting political science as an institutionalised discipline (to ensure regime stability) does come with costs and trade-offs for the regime, even in non-democratic contexts. As alluded to in the first argument above, the discipline potentially plays important roles in training civil servants and diplomats and delivering knowledge about the functioning of the state and international relations. These outcomes may benefit also authoritarian governments (Fu Reference Fu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990; Jinadu Reference Jinadu, Easton, Gunnell and Graziano1990). Insofar as the latter concerns are deemed as more important by at least several authoritarian governments, we may expect the difference between democracies and autocracies to be relatively small. This could especially be the case if authoritarian governments adopt various other strategies that allow them to have (and thus reap most of the benefits of) political science departments while at the same time mitigating their political risks. Some such strategies could pertain to influencing where political science departments are located, and in the following we discuss different locational aspects of relevance.

One relevant feature is the spatial location of political science departments. Autocratic regimes could locate political science departments strategically within their territories to mitigate the above-described trade-off and profit from the benefits of having some form of institutionalised political science education and research while trying to limit the threat to regime stability. Studies on autocratic systems highlight that leaders often put a high price on recruiting loyalists to bureaucratic positions, even when these loyalists are less competent (for example, Zakharov Reference Zakharov2016). Loyalists may be distributed unevenly across the territory, for instance, being concentrated in the capital area (in part because autocrats have strong incentives to relocate their capitals to cities populated by loyalists, with correspondingly lower risks of coups and revolutions, see Knutsen, Morgenbesser, and Wig Reference Knutsen, Morgenbesser and Wig2024). Indeed, the capital area may be particularly advantageous for locating the training of political science students also for other reasons than recruitment of loyalists into the bureaucracy and diplomacy: Insofar as security agencies and secret services that perform key monitoring and repression tasks for the regime are concentrated in the capital, this may help the regime in screening and constraining potentially dangerous political science students or faculty members tempted to teach ‘dangerous’ ideas in the classroom. Hence, we might expect that political science departments, all else equal, would be located closer to the capital of the country in autocracies than in democracies.

Yet, we discussed above how these concerns related to political scientists being opportunistic troublemakers may be far less relevant to many governments, including those presiding over very autocratic regimes, than the potential governance benefits accompanying the research and teaching of political science. Insofar as political science is primarily viewed by politicians – democratic and autocratic ones alike – as a handmaiden of the state and a discipline that is mainly useful for supporting the effective exercise of power, institutions that provide political science research and education should be located close to the centre of political power. In other words, we should expect that universities with political science departments would be located closer to the capital of the country than universities without political science departments, and this relationship should be visible (and fairly similar) regardless of regime type.

Another locational aspect of political science departments pertains to the type of university rather than geography. More specifically, who owns and operates the university could be relevant in terms of incentives to facilitate the existence of a political science department. If politicians perceive political science predominantly as a discipline that serves as a handmaiden of the state, one might expect that – independent of regime type – governments would have an interest in offering political science mainly in public universities. This would enable the state to have a more direct say about the curriculum as well as the focus of political science research so that it fits state demands. If so, we should observe, in autocracies and democracies alike, that public universities are more likely than private universities to have a political science department.

However, if political science is perceived, at least by many autocratic leaders, mainly as a ‘dangerous’ discipline in need of control, then public universities, which are directly linked to the state, should be even more likely to have political science departments (compared with private universities) in autocracies. In addition to using loyalty signals as recruitment mechanisms for students and academics, and thus limiting the risks from public universities (Haass Reference Haass2025), public ownership, funding, and management of education bodies may enable better control over curricular content and indoctrination efforts (see, for example, Neundorf, Nazrullaeva, Northmore-Ball et al. Reference Neundorf, Nazrullaeva, Northmore-Ball, Tertytchnaya and Kim2024). Additionally, several western universities have expanded their operations into authoritarian countries with the conviction that: ‘Private universities are one of the counter-majoritarian institutions that helps keep people free’ (Ignatieff Reference Ignatieff2024: 196). While allowing these private universities to operate in an autocratic context might hold several advantages for the regime, including better access to well-trained graduates, their greater independence from state control might make the regime less willing to tolerate political science education in these institutions. Therefore, it would be reasonable to anticipate that the (positive) difference in the likelihood of having a political science department between public and private universities would be larger in autocracies than in democracies. In the following section, we will present the data and operationalisation of our key variables before we proceed to test the various expectations outlined above.

Data and methods

To study the global distribution of political science departments, we draw on the WHED, which has been created and updated by the IAU in collaboration with United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) since the 1950s (IAU 2023). The WHED is the most comprehensive and authoritative dataset on universities worldwide. The data provided are only for the most recent year (2022 for our study) and thus only allow for cross-sectional analyses. This creates limitations for our study, as it prevents us from observing temporal dynamics, visible, for example, in the openings or closures of departments that could be linked to processes of democratisation or autocratisation. This also means that we cannot say with certainty how recent a phenomenon the global distribution of political science that we observe is, besides that it is the status quo in 2022. The original dataset comprises information on more than 20,000 higher education institutions, which have more than 500,000 divisions (for example, departments or schools), in total. The information is provided to the IAU by official public sources as well as the universities themselves, and it is subsequently quality-controlled by IAU staff.

To identify political science departments, we relied on earlier coding efforts by Weidmann and Rulis (Reference Weidmann and Rulis2025). The university divisions in the WHED include a subject field, where divisions are assigned 1 of around 700 subjects. Weidmann and Rulis (Reference Weidmann and Rulis2025) assigned these subjects to 26 narrow fields, following where possible the UNESCO International Standard Classification of Education (UNESCO 2013) (although the WHED categories are slightly different). From these 26 fields, we considered the following eight disciplines as ‘political science’: civics, comparative politics, government, human rights, international relations and diplomacy, international studies, peace and disarmament, and political sciences. This is a conservative measure since we excluded departments that had a more general social science denomination and included political science. For example, the University of Luxembourg has a Department of Social Science that has a dedicated ‘Institute for Political Science’, but since the department itself has a more general label, it was not counted as a political science department. Similarly, the Sultan Qaboos University in Oman has a College of Economics and Political Science that was also not counted because of its more interdisciplinary structure. Therefore, we provide analyses with variations of this measure below. To account for the possibility that university-specific differences in the ways in which universities are organised influence the likelihood of having a registered political science department, we controlled for (log) number of all divisions at the institutions as well as its age in the different regressions.

Of the 531,389 divisions in the dataset, 9096 (1.7%) were coded as political science departments, following the operationalisation laid out above. For each higher education institution in our sample, we coded a binary variable registering whether (1) or not (0) it had a political science department. After removing micro-states and institutions outside the borders of states, we ended up with 19,428 institutions, of which 25% had a political science department. From the WHED, we also obtained information about whether a higher education institution was a public or private organisation. To measure the distance from the capital, each institution’s city was geolocated using the GeoNames database (https://geonames.org). The distance was then computed as a straight line on the spherical earth from the country’s capital, the coordinates of which were obtained from the CShapes 2.0 dataset (Schvitz, Girardin, Rüegger et al. Reference Schvitz, Girardin, Rüegger, Weidmann, Cederman and Gleditsch2022). Since countries have vastly different sizes, we rank-transformed the distance by country so that institutions located in the national capital were assigned the lowest value (0) and those farthest away from the capital the highest value (1).

We measured regime type by drawing on data from Version 14 of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset (Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Angiolillo, Bernhard, Borella, Cornell, Fish, Fox, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, God, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Neundorf, Paxton, Pemstein, Ryden, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2024). For our cross-country analysis, we used the continuous Electoral Democracy Index (or Polyarchy), which ranges theoretically from 0 to 1 (highest level of democracy). This index focuses on the existence of multiparty elections and extension of voting rights but also the protection of certain rights and other conditions (for example, absence of violence or voter fraud) that enable these elections to be free and fair. More specifically, the index is composed of five subindices pertaining to, respectively, key officials being elected, the integrity of these elections, suffrage, freedom of speech and access to alternative information, and freedom of association.

We added several control variables to our models. Ansell (Reference Ansell2008; Reference Ansell2010) argues that, beyond a country’s regime type, its economic situation influences policy preferences regarding education. More specifically, countries that are better integrated in the global economy and have higher levels of economic development have a greater need for highly educated citizens to sustain their economic performance. This makes such countries more likely to increase access to education, which in autocracies is especially focused on higher education, inter alia because these regimes try to target education spending more to the elites (Ansell Reference Ansell2010). There are also other studies indicating that political science education flourishes in more affluent societies with wider access to higher education (Almond Reference Almond, Goodin and Klingemann1998; Newton and Vallès Reference Newton and Vallès1991). On the basis of these arguments, we added GDP per capita (in current USD, log-transformed) as a control variable to our cross-national models, using data obtained from the World Bank (World Bank 2025). To account for differences in country size affecting the likelihood of having political science departments, we also controlled for the (log-transformed) population of the country in these models.

Our benchmark specifications were ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with standard errors clustered by country. In analyses that focus on within-country variation, we always included country-fixed effects to account for unmeasured country-specific confounding factors (including level of development, population level and settlement patterns, national educational cultures, and so forth) that may simultaneously influence the propensity for universities to have a political science department and the explanatory factors of interest (for example, public versus private university or distance of the university from the capital). Insofar as we hypothesised differences across democratic and autocratic regimes, we ran all within-country analysis on split samples. Rather than relying on a categorical definition of regimes, we distinguished between autocratic countries, hybrid regimes, and democracies by assigning countries to the first, second, and third tercile of the distribution of V-Dem’s Polyarchy index. This mirrors the strategy proposed by Hainmueller, Mummolo, and Xu (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019) for testing for nonlinear interaction effects, which potentially also exist in our data. While less efficient than a standard interaction specification, this approach allows us to test interaction effects with a moderator (level of democracy) at the country-level, while retaining country-fixed effects in our models.

Results

To provide an initial impression of the global distribution of political science departments, the map in Figure 1 depicts the location of higher education institutions with such departments across the world in 2022. It clearly shows that political science is currently a global discipline with dedicated departments on all continents and in most regions of the world. At the same time, political science departments were not evenly distributed across countries. There were, for example, higher concentrations of political science departments in North America and Europe, but also in South and South-East Asia.

Figure 1. Map of institutions with political science departments.

To assess whether differences in political regime type contribute to the cross-country variation indicated by Figure 1, we considered the cross-country relationship between degree of democracy and the presence of political science departments in a country’s universities. We started by plotting all countries in Figure 2, where the x-axis describes the country’s score on V-Dem’s Polyarchy index, while the y-axis displays the share of universities in the country that have a political science department. The figure shows that organised political science does exist in democracies and autocracies and the overlaid nonparametric, smoothed, best-fit line indicates that the share of institutions with political science departments does not correlate strongly with regime type. Globally, there were only six (mostly small) countries in our sample without any registered political science department, following our operationalisation (Oman, Djibouti, the Solomon Islands, the Comoros, Chad, and Luxembourg).

Figure 2. Share of institutions with political science departments by country, with countries ordered by their level of liberal democracy (left: autocratic; right: democratic). Nonparametric smoothing has been applied in blue. Countries with a share of 1.0 are those with only a single university that has a political science department. Countries with a share of 0.0 do not have any political science division. Abbreviations in the figure: GM = The Gambia, GQ = Equatorial Guinea, LU = Luxembourg, SB = Solomon Islands, TD = Chad.

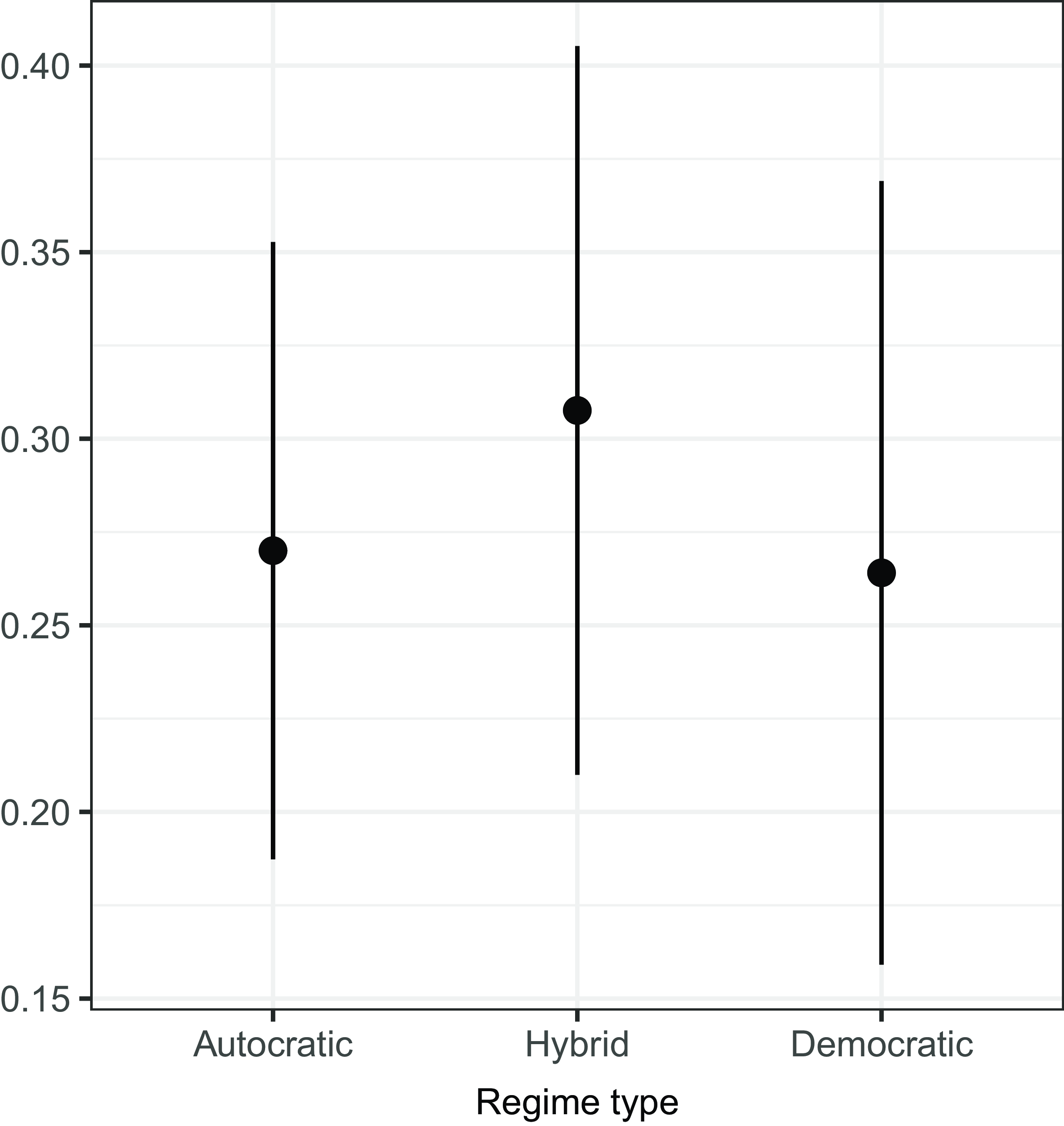

To unpack this relationship further and take a closer look at the previously formulated expectations, we estimated linear probability models according to the specifications described in the prior section, using higher education institutions as the unit of observation. The dependent variable was whether an institution had a political science division (0/1). Figure 3 displays the results of our specification controlling for number of divisions at the university, GDP per capita, and country population (all logged). When using our three-fold regime type classification, we did not find any significant differences between the three categories of regimes. It seems, based on our data and specifications, that there was no systematic relationship between regime type and the likelihood that a university had a political science department. The results displayed in Figure 3 are in line with the findings shown in Figure 2. Taken together, these patterns in the data provide indicative support of the argument highlighting political science’s perceived role as a handmaiden of the state, regardless of regime type. We might speculate, on the basis of these results, that the mere presence of political science departments is not perceived as a severe threat to regime stability by most autocratic regimes or that autocratic regimes have found ways to shape (Perry Reference Perry2020) or control political science teaching and research so that their perceived benefits outweigh the remaining risks.

Figure 3. Predicted values of the probability that an institution has a political science department (0/1), by regime type. Plot based on Model 2 in Table A1 (online Appendix).

In additional models presented in Table A1 (online Appendix), we show that our results are robust to controlling for supply-side effects related to the discipline’s history and institutionalisation in a country that may contribute to the prevalence of political science divisions across the institutions in the country. More specifically, we controlled for the existence of a national political science association (Model 3) or the membership of this organisation in the International Political Science Association (Model 4).Footnote 2 Furthermore, we observed almost no changes in our results when applying variations of what ‘political science’ should include. The first model in Table A2 (online Appendix) used a very narrow definition and included only divisions labelled as ‘political sciences’ or ‘comparative politics’. The second model focused specifically on ‘government’ and ‘international relations’ departments, which our arguments suggest might be perceived as less controversial in autocratic regimes (compared with political theory or comparative politics teaching, focused, for example, on democracy). The third model isolated departments that could be particularly contested in autocracies (‘civics’, ‘human rights’ and ‘peace and disarmament’). This is the only subcategory which, according to our results, was less frequent in autocracies (the coefficient for the democracy dummy was positive and significant). Finally, we note that we found comparable results for neighbouring disciplines as for political science. More specifically, Model 4 in Table A2 shows clear regime differences for a similar measure registering sociology or cultural studies departments.

In Table A3, we tested alternative, continuous outcome measures such as the share of universities with political science departments (Model 1), and the share of political science divisions across all divisions in the country (Model 2) in an analysis at the country level. Again, we found no discernible differences between regimes. Finally, although we believe that linear probability models constitute a more conservative and robust estimation approach (Timoneda Reference Timoneda2021), in Table A4 we repeated Models 1 and 2 from our main analysis when using a logit-estimator for the binary outcomes. Our results were robust to the choice of estimator.

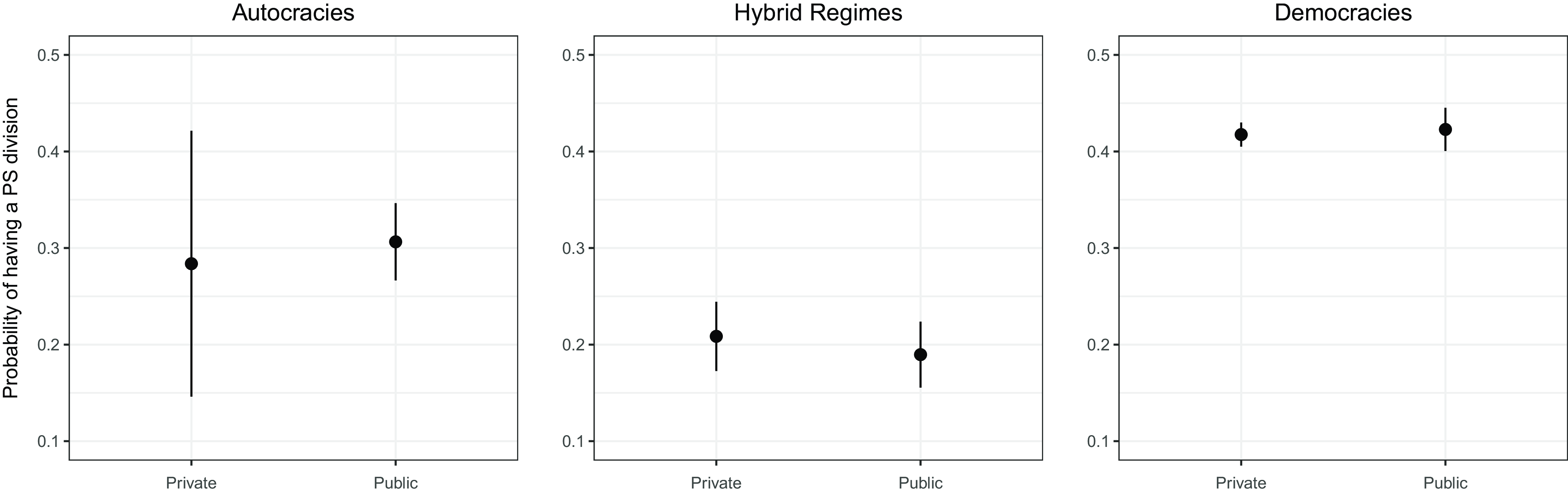

Next, we turn to the two strategies that we discussed for how regimes may reap the benefits while controlling the potential risks of having political science departments. We did so by investigating two university-level predictors (geographic location and public ownership) of the university having a political science department or not. For each of our three regime categories, we ran complete models that included all university-level predictors at once (Table A5 in the online Appendix) alongside country-fixed effects. We visualise the respective coefficients in Figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4. Relationship between relative distance to the capital and the probability of a university having a political science department (0/1), for autocratic, hybrid, and democratic regimes. Plot based on Models 1–3 in Table A5.

Figure 5. Marginal effect of public institution on an institution having a political science department (0/1), by level of democracy. Plot based on Models 1–3 in Table A5.

First, we examined whether there was variation in the geographical placement of political science departments relative to a state’s capital across regime types. Figure 4 shows that a university’s distance to the capital (rank-ordered by country) was negatively related to having a political science department in all three regime categories. In other words, political science departments tend to be placed in universities that are located closer to the capital. However, the effect was strongest (more negative) in democracies, followed by autocracies. In both regime types, the relationship was statistically significant at the 5% level. In hybrid regimes, the controlled correlation was indistinguishable from zero. The results for democracies and autocracies thus provide further indicative support for the argument that considers political science as a handmaiden to the state. The spatial proximity of political science departments to centres of government might reflect the discussed links between political science research and teaching, on the one hand, and governmental or public sector work, on the other.Footnote 3

Finally, we turn to the second proposed strategy that political elites might employ to better control the benefits and potential risks associated with having political science departments. Figure 5 visualises the predicted probabilities of public versus privately owned higher education institutions having political science departments (see online Appendix Table A5 for the regression results). The plot shows that the relationship between the ownership of a university and political science was weak across regime types: While public institutions seemed to have a slightly higher probability of having a political science division in autocracies, there was no difference in democracies, and a slightly lower probability in hybrid regimes. However, the differences remained insignificant at conventional levels for all three types of regimes. Hence, there does not seem to be any clear patterns linking university ownership, types of regime, and the probability of having a political science department. One factor here could be that western universities have expanded ambitiously into authoritarian countries and that some of these institutions also include political science units (for example, New York University [NYU] Abu Dhabi; Ignatieff Reference Ignatieff2024). But this potential relationship demands further, more-detailed investigation.

We once again re-ran the analysis after using different operational definitions of what a ‘political science’ division is. Tables A6 and A7 in the appendix show that the placement closer to the national capital held when using a narrow definition of ‘political science’ and when focusing on ‘government’ and ‘international relations’ divisions, but not for ‘civics’ and ‘human rights’ divisions in autocracies (see Table A8). While it may be tempting to give a substantial explanation of the latter finding, one likely, methodological explanation is simply that there are very few such divisions. Also for the alternative definitions of political science, private or public ownership did not seem to make a difference. One exception was that ‘government’ and ‘international relations’ divisions were more likely to be affiliated with private institutions in democratic countries. Finally, we re-ran our benchmark models with binary outcomes, but using a logit estimator instead of OLS. We found no difference from our main results (see Table A9).Footnote 4

The lack of clear regime differences is, once again, consistent with the political-science-as-handmaiden-of-the-state argument, but the overall similarity between private and public universities is not; based on this argument, we anticipated political science departments to be more frequently found in public universities. One possible explanation for the latter pattern could simply be that we overestimated the importance of ownership for state actors when it comes to employing various mechanisms of control. Even if private higher education might emerge from initiatives outside of a national government, states can and do create regulatory frames for private and public higher education institutions and use them to steer both (Levy Reference Levy2011). Thus, even if private institutions might be slightly more distanced from direct control by a ministry, the broader regulatory toolkit containing, for example, quality assurance systems, degree recognition, or financial support (or threats of withdrawal of such) may often be strong enough to make ownership matter less when it comes to ensuring political control over universities, including political science departments and their activities.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have addressed the complicated relationship between politics and political science. More specifically, we highlighted the mixed incentives that governing elites may have when it comes to creating organised environments for research and teaching in this discipline. In doing so, we specifically focused on regime differences along the democracy–autocracy dimension. On the one hand, political science knowledge and graduates may be viewed as helpful and important by incumbent elites in democracies and autocracies alike, insofar as they provide useful insights for governing and help staff bureaucracies and diplomatic corps. Contrary to this handmaiden-of-the-state perspective, another perspective highlights the potential dangers – from the viewpoint of governing elites, especially in autocracies – of facilitating political science teaching and research. The spread of ideas and norms from normative democratic theory or graduates who have been taught about the effectiveness of nonviolent protests or the organisation of effective opposition parties may be perceived as running contrary to core interests of autocratic elites. Whereas the first perspective suggests that political science research and teaching should be prevalent in different regime contexts, the second political-scientists-as-troublemakers perspective implies that it should be relatively more prevalent in democracies.

The results presented in this paper, based on data from about 20,000 universities worldwide, provide indicative support of the first perspective and less support for the second one: We found no substantial and clear regime differences when it came to the prevalence of political science departments. Political science seems to be a truly global disciplines (as of 2022) with organised teaching and research environments on all continents. Only six countries in our sample did not have a political science department, according to our operationalisation, of which at least two had political science units as part of broader social science departments. While we, strictly speaking, only can say something about the current spread of political science departments based on our data, we suspect that it has come about from a recent expansion in many countries. Similar patterns have been described with regard to higher education in general, insofar as the university as a knowledge organisation is experiencing unprecedented levels of spread and expansion – recently, more countries around the world have educated more students in more subjects (Frank and Meyer Reference Frank and Meyer2020). It seems plausible to believe that political science is part of this development. What is more, we do not find that autocracies make more use of observable measures proxying for ‘control strategies’ such as locating political science departments closer to the capital or in public rather than private universities, when compared with democracies. These findings are somewhat surprising, not only when viewed in light of the political-scientists-as-troublemakers perspective but also in light of observed restrictions and curtailment of political science, historically, in prominent autocracies such as China or the Soviet Union. One explanation could be that autocratic countries’ quest for international and domestic legitimacy, which has been described as one factor linked to the rise of electoral authoritarianism (see, for example, Miller Reference Miller2020), could also be at play here, and that gains in legitimacy in combination with the gains from having well-trained civil servants outweigh the risk of allowing departments of political science.

The latter point may speak to the dangers of overgeneralising from prominent cases, but it may also speak to the shifting nature of political science teaching and education across the world, as our data reflect the situation in 2022. Following the more general notion of ‘educated acquiescence’ by Perry (Reference Perry2020), it might be that political science research and teaching have been structured and shaped, more subtly, in such ways that many current autocrats not only tolerate political science departments but also reap benefits from and promote them. Recent discussions in China about ‘western’ political science concepts and their appropriateness to Chinese society versus employing more specific Chinese understandings of the discipline (Wang and Guo Reference Wang and Guo2019) could be an example of how the discipline becomes localised. This process could then open up the possibility for autocratic regimes of filtering out aspects of the discipline that potentially present a threat to their survival.

However, the latter point remains a conjecture. As we have already discussed, the cross-sectional nature of the data creates certain limitations for this analysis. Unfortunately, the WHED does not make time-series data available that would allow for observing temporal dynamics, such as openings or closures of departments that could be linked to processes of democratisation or autocratisation. Future research should, either through detailed country-case studies or the use of other data sources, unpack this temporal aspect to get a better understanding whether the global spread of political science is a recent phenomenon and to what extent regime dynamics can be linked to expansion or contraction of the discipline over time. Additionally, more systematic research, using more fine-grained data on teaching activities (for example, course profiles) or research activities (for example, topics of publications) taking place within political science departments – preferably with extensive time series – would be needed to evaluate whether our results and accompanying interpretations are valid descriptions of historical developments, recent trends, and current realities.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1682098326100241.

Data availability statement

Replication data and coding for this article are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UYQB61. The data on the institutions were included without identifying information since it was taken from the WHED. Access to this database was purchased by the authors and does not include the right to redistribute the data. Using the replication material, it is possible to replicate all statistical results and figures in the article and the supplementary material, with the exception of the map in Figure 1.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 863486). Jens Jungblut would like to thank Neil Ketchley for his comments and feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.