Introduction

The bird family Meliphagidae (Honeyeaters) is a widespread taxon that has diversity centred within Australia and New Guinea (Ford Reference Ford, Higgins, Peter and Steele2001). Member species extend in an arc east of the island of Java (Indonesia) to the Northern Mariana Islands in the north, American Samoa to the west and south to below Australia and New Zealand to the subantarctic Auckland Islands (Ford Reference Ford, Higgins, Peter and Steele2001, Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Bonan, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017b). This largely insular distribution supports high numbers of single-island endemics at different taxonomic levels that pose a challenge for both phylogenetic systematics and conservation (Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet2010, Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Naikatini and Moyle2014, Joseph et al. Reference Joseph, Toon, Nyari, Longmore, Rowe, Haryoko, Trueman and Gardner2014). Particular Meliphagidae have undergone radiations to become some of the most abundant representatives of insular endemic forms in the region, for example Myzomela honeyeaters (Koopman Reference Koopman1957, Mayr and Diamond Reference Mayr and Diamond2001), whilst others are now monotypic genera restricted to single islands (e.g. Stresemannia, Meliphacator and Guadalcanaria species; Mayr Reference Mayr1932, Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Naikatini and Moyle2014). Conserving this diversity continues to be a concern given the high representation of island bird taxa amongst historic extinctions (Johnson and Stattersfield Reference Johnson and Stattersfield1990, Szabo et al. Reference Szabo, Khwaja, Garnett and Butchart2012).

Many meliphagid species remain poorly known and in particular, the two species that remain categorised as ‘Data Deficient’ on the IUCN Red List, the Tagula Honeyeater Microptilotis vicina and the White-chinned Myzomela Myzomela albigula (IUCN 2016). Clarifying the conservation status of these species is a priority given the threat of impacts from anthropogenic climate change (Sekercioglu et al. Reference Sekercioglu, Schneider, Fay and Loarie2008, Reference Sekercioglu, Primack and Wormworth2012, Goulding et al. Reference Goulding, Moss and McAlpine2016) and declines in forest extent observed in many insular locations of the south-west Pacific region (e.g. Buchanan et al. Reference Buchanan, Butchart, Dutson, Pilgrim, Steininger, Bishop and Mayaux2008, Miettinen et al. Reference Miettinen, Shi and Liew2011, Margono et al. Reference Margono, Potapov, Turubanova, Stolle and Hansen2014).

Notably, both of these ‘Data Deficient’ Meliphagidae bird species occur within the Louisiade Archipelago of Papua New Guinea (IUCN 2016). Islands of the Louisiade Archipelago comprise an important hotspot of endemism that continues to reveal hidden avian diversity (e.g. Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Shult, Cibois, Thibault, Filardi and Moyle2015, Marki et al. Reference Marki, Fjeldså, Irestedt and Jønsson2018). Consequently, although already recognised as supporting more than 10% of the Data Deficient bird species remaining globally (six of 58 species; BirdLife International 2013, IUCN 2016), this number is likely to be an underestimate. Since their discovery, determination of the conservation status of these species has remained stymied by a lack of research prioritisation and the remote and difficult access (Tristram Reference Tristram1889, Hartert Reference Hartert1898, Rothschild and Hartert Reference Rothschild and Hartert1912).

The Tagula Honeyeater has remained one of the least known members of the Meliphagidae. Previous research, prior to this study, has reported the species as a single-island endemic species known to occur only on the largest island in the archipelago, Sudest Island (Pratt and Beehler Reference Pratt and Beehler2014, Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Sharpe, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017c, BirdLife International 2018). Based upon morphology and biogeography, it has been assigned to the analoga group, one of two clades proposed for the Meliphaga genus and containing the two suspected closest relatives (the Mimic Honeyeater M. analogus and Graceful Honeyeater M. gracilis; Christidis and Schodde Reference Christidis and Schodde1993, Norman et al. Reference Norman, Rheindt, Rowe and Christidis2007). Subsequent investigations have resulted in the majority of these smaller-bodied taxa (Meliphaga spp.) being placed into the Microptilotis clade, including the Tagula Honeyeater (Schodde and Mason Reference Schodde and Mason1999, Joseph et al. Reference Joseph, Toon, Nyari, Longmore, Rowe, Haryoko, Trueman and Gardner2014, Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Sharpe, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017c). To our knowledge only one molecular investigation has included this species (see Marki et al. Reference Marki, Jønsson, Irestedt, Nguyen, Rahbek and Fjeldså2017). Unfortunately, the phylogenetic relationships of the Tagula Honeyeater and closely related Microptilotis species were not confidently determined in this study. Consequently, the taxonomic status and phylogenetic relationships of the Tagula Honeyeater have remained largely inferred from morphological measurements taken from a limited number of museum skins and the species’ known distribution. This has resulted in continuing uncertainty around its taxonomic status and even whether it should be subsumed into other closely related species such as the Mimic Honeyeater (Beehler and Pratt Reference Beehler and Pratt2016). Frustratingly, not only are the phylogenetic relationships of the Tagula Honeyeater obscure but the lack of detailed distribution information, population data and natural history information continues to hinder a conservation assessment (IUCN 2016).

Here, we aim to introduce new data to improve upon the sparse available information on this species. Specifically, we aim to provide information useful for the conservation assessment of this species. This includes: 1) a revised species’ distribution; 2) an estimate of the population size, and; 3) observations on the habitat-use, diet and vocalisations of the species. We also aim to add further morphological data from captured specimens.

Methods

Research trips were conducted between the months of October and January in the years 2012–2017 (2015 excluded). The majority of our Tagula Honeyeater observations were made during late 2016. However, opportunistic observations were also noted from other years, during which over 182 days were spent across 11 islands in the Louisiade Archipelago (11°15´S, 153°12´E). The 11 islands visited were: Sudest (67 days); Junet Island (44 days); Sabara Island (30 days); Panawina Island (13 days); Misima Island (10 days); Kimuta Island (seven days); Rossel Island (five days); Nimowa Island (four days); and, Nigahau, Hemenahei and Hesesai (less than half a day each). Furthermore, information on bird distributions was gathered for other islands, such as Piron and Kuwanak Islands, via consultation with local residents familiar with these islands.

We used both 6m and 12 m mist nets on the ground and in the canopy to capture birds in different habitats and on different islands (Lowe Reference Lowe1989, Rinehart and Kunz Reference Rinehart and Kunz2001). Tagula Honeyeaters were leg-banded using Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme (ABBBS) bands and coloured bands for individual identification. Standard morphometric measurements were taken following Lowe (Reference Lowe1989), with bill width and depth measured at mid-nares and the wing length measured adpressed. Blood samples were collected by venepuncture following Owen (Reference Owen2011). Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) methods were used to determine the sex of captured birds for morphological comparisons. We used PCR primers 2550F-5 - GTTACTGATTCGTCTACGAGA-3 and 2718R-5 - ATTGAAATGATCCAGTGCTTG-3 developed by Fridolfsson and Ellegren (Reference Fridolfsson and Ellegren1999).

Habitat use and movements

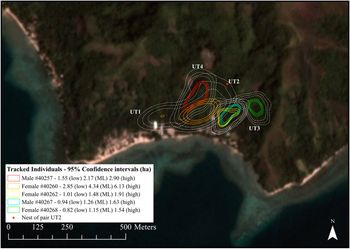

Individual Tagula Honeyeaters were captured during the breeding season on the island of Junet in November-December 2016. The study area on the south-east of Junet Island consisted of a coastal flat area and low hills surrounding the village of Bwailahine (Figure 1). Habitat types in the area were disturbed and secondary growth forest of various ages interspersed amongst food gardens and along riparian remnants. Some remnant forest patches remained on riparian strips. Scattered coconut palm Cocos nucifera plantations and sago palm Meteroxylon sagu groves occurred at low elevations.

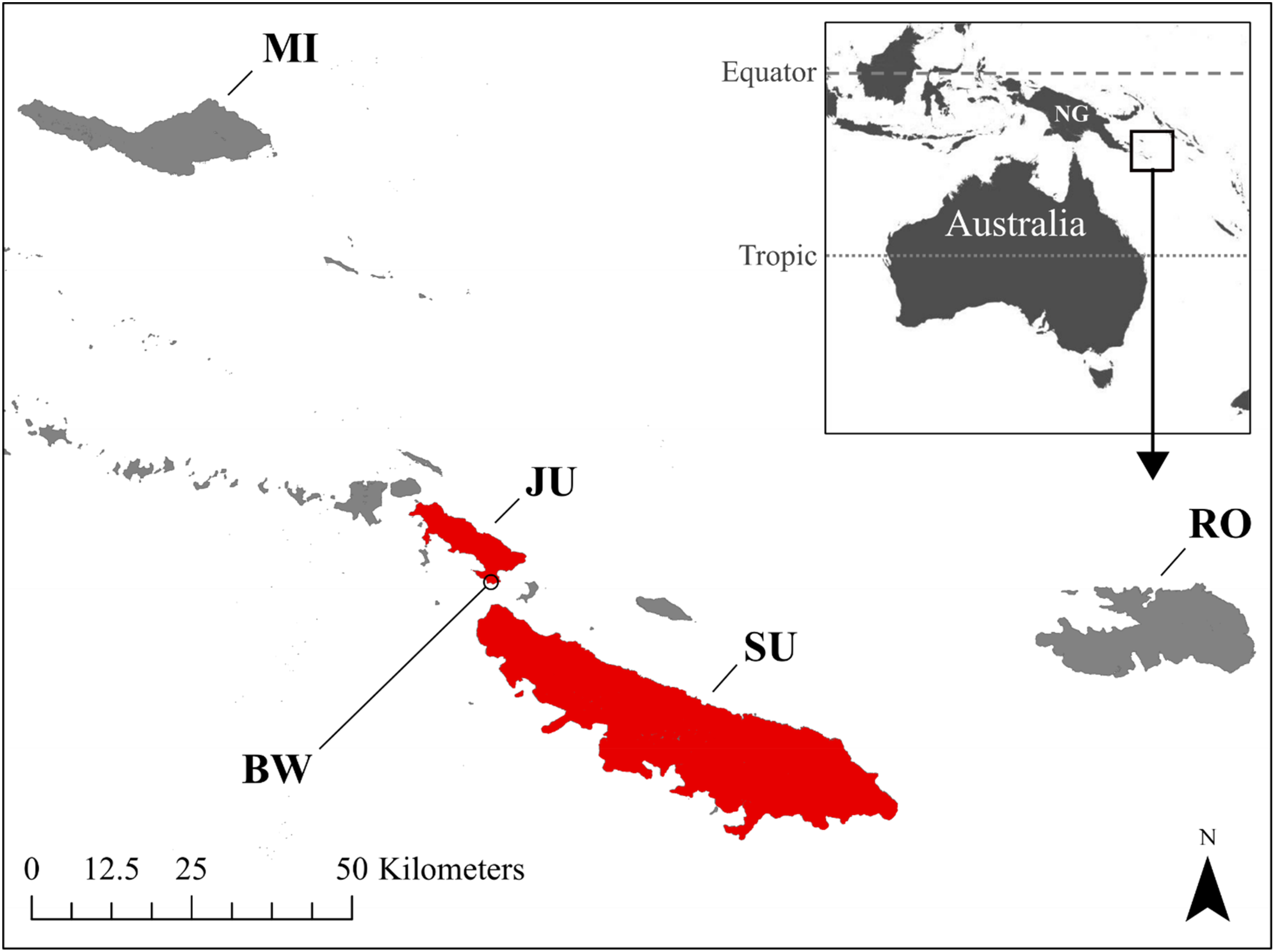

Figure 1. The distribution of Tagula Honeyeaters M. vicina in the Louisiade Archipelago of Papua New Guinea. The three largest islands are Misima (MI), Sudest (SU) and Rossel (RO). This species is restricted to Sudest Island (SU) and Junet Island (JU), as indicated in red. The location of the habitat use and home range study near the village Bwailahine is shown (BW; -11° 17ʹ S, 153° 11ʹ E).

A2414 (Advanced Telemetry Systems, MN USA) UHF transmitters were used. These were dorso-anteriorly mounted at the base of the two central tail feathers using a single thin loop of medical tape (Wilson and Wilson Reference Wilson and Wilson1989). This method was adopted due to the relatively long tail in this species that allowed rapid transmitter attachment with minimal disruption to normal flight and balance. The secure adhesion of this type of tape to itself reduced the need for overlap of tape or glues that could add weight or damage the feathers, allowing for easy removal.

We used Version 0.4.1 of CTMM package (Calabrese et al. Reference Calabrese, Fleming and Gurarie2016) in R (R Development Core Team 2017) for home-range estimation for the tracked honeyeaters. This package is based upon the use of Continuous Time Stochastic Process models (CTSPs) and can take into consideration autocorrelation (Markovian, position; non-Markovian, position and velocity), in an Autocorrelated Kernel Density Estimator (AKDE; Fleming et al. Reference Fleming, Fagan, Mueller, Olson, Leimgruber and Calabrese2015). We considered this to be the best approach for drawing inference from these fast-moving individuals that were tracked over a short time. We followed the workflow demonstrated by Calabrese et al. (Reference Calabrese, Fleming and Gurarie2016), assessing AIC values in model selection with visual assessments of model fit to semi-variance over the short, medium and long time lags.

Population census

We assessed relative density of this species through extrapolation of the home range data from radio-tracking, point count surveys and line transects. Standard point counts were trialled in the same area as the radio-tracking was conducted, to compare estimates using these two methods (Bibby et al. Reference Bibby, Burgess, Hill and Mustoe2000). The estimated detection distance for point count surveys was determined through initially searching and confirming the locations of calling individuals, prior to the survey trials beginning. Transects were opportunistically conducted by walking approximately at 4 km/hr along forest paths and bush tracks, noting any honeyeaters seen or heard. Occurrence data were combined with Global Forest Change data on forest extent for the year 2000 (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Potapov, Moore, Hancher, Turubanova, Tyukavina, Thau, Stehman, Goetz and Loveland2013) to generate an estimate of population size. Given prior observations of different habitat-use in this species, we excluded areas with less than 10% canopy cover to remove grasslands and unsuitable habitat predominantly devoid of vegetation. Forest loss has occurred since this date (e.g. Goulding et al. Reference Goulding, Perez, Moss and McAlpine2018). However, we considered even young regenerating regrowth as suitable habitat, reducing the potential for habitat overestimation due to habitat loss since the year 2000.

Vocal analyses

Calls were recorded using a Sound Devices 702 digital sound recorder (Sound Devices LLC, Wisconsin) and a Sennheiser ME 67 directional microphone. Calls were analysed using the software programs Audacity - Version 2.0.2 (Audacity Team 2012) and Raven Lite - Version 1.0 (Bioacoustics Research Program 2006, Charif et al. Reference Charif, Ponirakis and Krein2006).

Results

Local names and cultural value

Usually lumped into a generic grouping of small birds called Tiko-tiko or Kanjeje/Kajeje.

This species has little cultural value (current time), as evidenced by it being lumped with other small bird species into a broader group.

Distribution

Tagula Honeyeaters were found only on Junet and Sudest Islands (Figure 1). The species’ extent of occurrence was estimated to be 1,000 km2, which included the unsuitable and small area of water between the two islands (EOO; IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee 2017). The total area of occupancy (AOO) within this EOO was estimated to be less than 850 km2 (excluding bare areas with < 10% forest cover). Tagula Honeyeaters were commonly encountered across all elevations, from sea level to between the second highest peak (Emuwo: 711 m asl) and the summit of Mt Riu (∼800 m asl).

Home range estimates

Five honeyeaters were followed, and positions collected, for four to six and a half days following radio transmitter attachment. Position fixes were taken opportunistically throughout the day between sunrise (05h30) and sunset (18h10). One individual (female #40620) prematurely dropped the radio transmitter, limiting the number of fixes to 32 points. Location data for the remaining four individuals ranged from 42 to 57 fixes with an average of 50 fixes (Figure S1 in the online supplementary material).

Variograms for all individuals demonstrated a clear asymptote, defining a home range over the longer time lags (Figure S2). Exploratory periodograms indicated that fluctuations in several variograms over medium time lags were likely due to a pattern of missed fixes in the dataset (Calabrese et al. Reference Calabrese, Fleming and Gurarie2016). Whilst semi-variance generally conformed to the best-fit models over the short, medium and long time lags, in one individual it was not representative at the extreme short time lags (#40267). The model selection process gave the Independence and Identical Distributions (IID) model as having the best conditional AIC (AICc) but importantly (Fleming et al. Reference Fleming, Fagan, Mueller, Olson, Leimgruber and Calabrese2015), this failed to capture the change in semi-variance observed at the extreme short time lags for this individual. The Ornstein-Uhlenbeck anisotropic (OU) model was chosen because the model fit values were extremely close and this model incorporated autocorrelation. The observed changes in semi-variance at the short time lags were considered to be representative of the rapid and spanning movements that Tagula Honeyeater individuals are capable of over short time frames.

In general, the continuous time movement models that produced the best fit to the honeyeater data were Ornstein-Uhlenbeck anisotropic (OU) and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck F anisotropic (OUF) models (Figure S3). These values generally differed only slightly from other model outputs, such as when compared to the more traditional (but incorrect) Kernel Density Estimates (KDE) that assume Independence and Identical Distributions (IID; Fleming et al. Reference Fleming, Fagan, Mueller, Olson, Leimgruber and Calabrese2015).

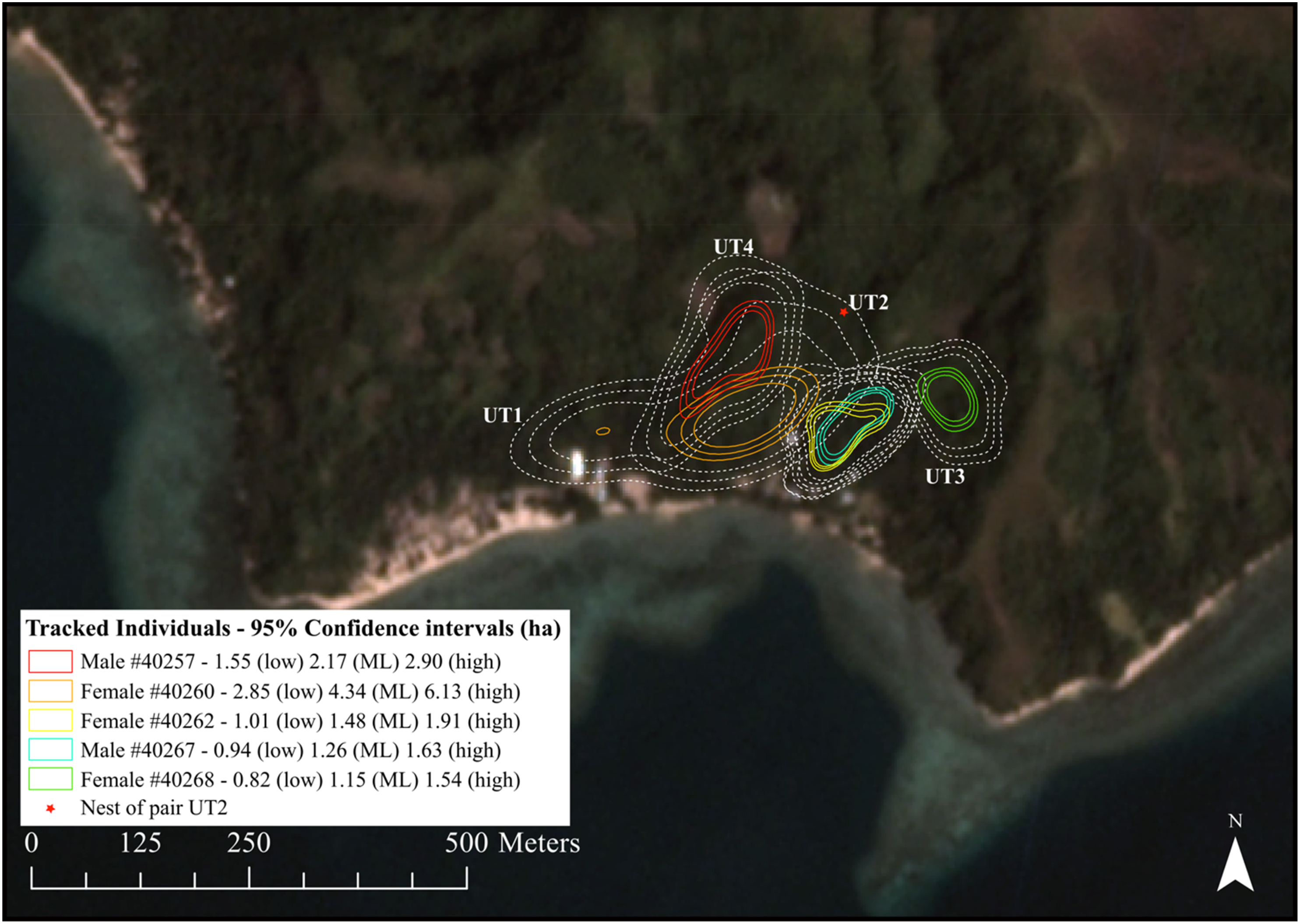

Home range estimates (AKDE) across individuals (n = 5; Figure 2; Figure S3) ranged from less than a hectare for lower 95% estimates to just over six hectares for the upper 95% home range estimate of one individual (female #40260). The mean area for the 95% (ML) home range area was 2.0 ± 0.6 (SE) hectares (n = 5). However, exclusion of female #40260, which dropped her transmitter early and for which estimates could have been inflated, lowered the average home range estimate to 1.5 ± 0.6 (SE) hectares (n = 4).

Figure 2. Configuration of the estimated home ranges for the five tracked Tagula Honeyeaters near Bwailahine on Junet Island. Different coloured sets of contours represent the 50% home range with confidence contours (core area) and dashed white contours represent their 95 % home range estimates with confidence limits. Untracked pair locations are indicated as UT1–4 and the position of the observed nest of the untracked pair UT2 displayed. Satellite imagery from the survey period (November 2016) courtesy of Planet Team (2017).

Female #40260 and her unbanded partner utilised a bimodal occupancy distribution. Regular and direct flights were observed to occur from the southern part of their core area to a large mango tree in the east, but they did not stray further into another untracked pair’s territory (UT1). This pair’s territory was thin and in an arc along the eastern edge of the 50% core area of male #40257 and his unbanded partner. Where the core areas (50%) of these two territories abut, we observed territorial conflict between these two pairs. Similarly, we observed conflict between female #40260 and partner with the pair #40262/67 on the eastern edge of their 50% core area. Conflict was also observed on the northern edge of both pairs estimated 50% home range areas with the untracked nesting pair (UT2). Furthermore, conflicts were observed just outside the estimated 50% home range area of female #40268 and an untracked pair (UT3) to the south. An untracked pair (UT4) was also observed on the northern edge of the 50% home range estimate of the pair that included male #40257 (Figure 2).

Habitat use

Tagula Honeyeaters were both captured and commonly observed between 2012 and 2016 in mangroves, around villages, established gardens, regenerating forest of different ages (∼2–20+ years), disturbed forest remnants and undisturbed forest. The species was also commonly observed across the complete elevational gradient into the montane cloud forest nearing the summit of Mount Riu on Sudest Island (∼793 m asl). Tracked individuals during the 2016 study utilised all available habitats in the study area, except for recently cleared gardens (bare areas; see Figure 2). Overall, the proportions of fixes in different habitat types were representative of the available habitat extents. The highest proportion of location fixes were in regrowth and regenerating forest habitat of different ages (49%). Coconut plantations and garden areas were also regularly used (28%), as were remnant forest patches along riparian zones (16%) and isolated trees (6%). Across these habitat types, 71% of observations were in the canopy layers (including the lower canopy and low canopy of younger regrowth) with the remaining 29% in understorey layers.

Diet

This species was observed drinking nectar from a variety of flowers, including coconut palm, Banana plants Musa spp., understorey and lower canopy vines and ground cover (e.g. Zingiberaceae; ∼1 m height). They were also observed eating fruit, for example the fruit of Macaranga involucrata (Figure 3h). Invertebrates were regularly consumed through active searching and gleaning from foliage in the canopy and understorey layers. Of clear food-consumption observations that were made during the radio-tracking, 62% were of arthropods gleaned off foliage, 29% were of nectar drinking and 9% of eating fruit (n = 35). A further 46 feeding observations of randomly encountered individuals included 23 that were consuming arthropods, 19 that were consuming nectar (especially from coconut flowers) and four instances of purplish fruit being eaten. Of interest, captured birds commonly defecated purple fruity material.

Figure 3. Features of the Tagula Honeyeater include grey lores and forehead region, yellow posteriorly-rounded ear-spots with less-distinct thin, yellow rictal streaks. Rictal streaks lead from the dark yellow to orange gape flange (obscured by the lores) toward the ear spots (but do not meet). The iris is slate-blue to grey in mature birds (a-b). Individuals may also have yellow tint to the orbital skin (b) and yellow digital pads (c). The breast and underwing coverts (particularly toward the leading edge) are washed yellow in colour (d). The two nests observed were constructed of similar materials and suspended in a fork with spider webs (e-g). The diet of the species includes fruit of the rainforest pioneer Macaranga involucrata (verified Vidiro Gei, personal communication 2017; h).

Population census

We estimated the detection range of Tagula Honeyeater contact calls to be most reliable up to 50 m. Beyond this and depending on the terrain, vocalisations were more difficult to hear and accurately locate or estimate location. The results of initial scoping trials with traditional five-minute point count methods raised serious concerns regarding the application of the method for this species (n = 16; Bibby et al. Reference Bibby, Burgess, Hill and Mustoe2000). We suspected the rapid and continuous movements of this vocal species inflated density estimates through repeated detections of the same individuals. These point counts at low elevations gave estimates of 3.0 ± 0.2 (SE) individuals per hectare on Sudest Island (n = 11) and more than double at 7.9 ± 1.2 (SE) individuals per hectare on Junet Island (n = 5; same area as radio-tracking, below). However, transects totalling 4.12 km through intact forest on Sudest Island reduced duplicate detections with estimates of 1.0 individual per hectare (0–150 m asl). Transects on the north-west of Sudest Island (Badia village) through heavily disturbed coastal vegetation of gardens and mangroves enclosed by grasslands, gave lower estimates of 0.64 individuals per ha (2.21 km).

By comparison, radio-tracking data in the same locality that point counts were trialled on Junet Island (see above) revealed much lower and more accurate population density estimates. The collective area encapsulated within the upper 95% confidence intervals for the tracked individuals was 8.98 ha. The overlapping territories in the pair #40262/67, in addition to observations and behaviour of single unbanded birds in the company of the other banded/tracked birds, indicated that each tracked bird had a partner at this time of year. Consequently, up to 10 birds (5 pairs) occupied this collective area or 1.1 individuals per hectare. However, the territory of female #40260 and her partner (6.13 ha) offer support that density could potentially be lower in some situations, for example, 0.33 individuals per hectare.

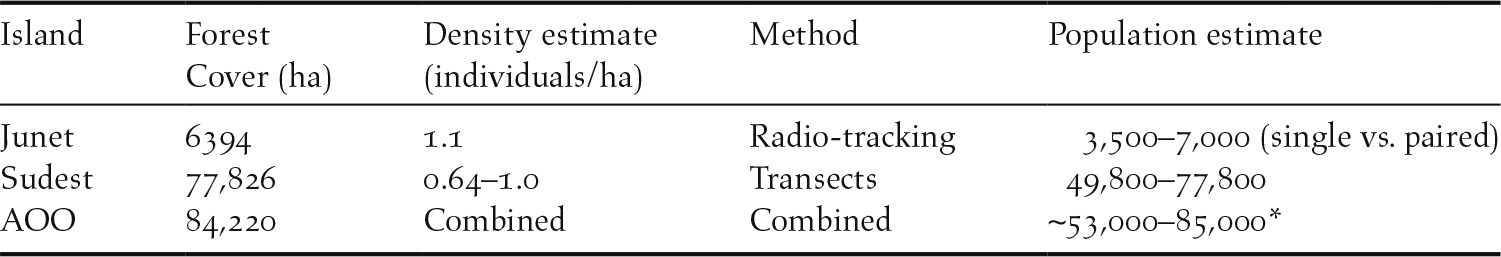

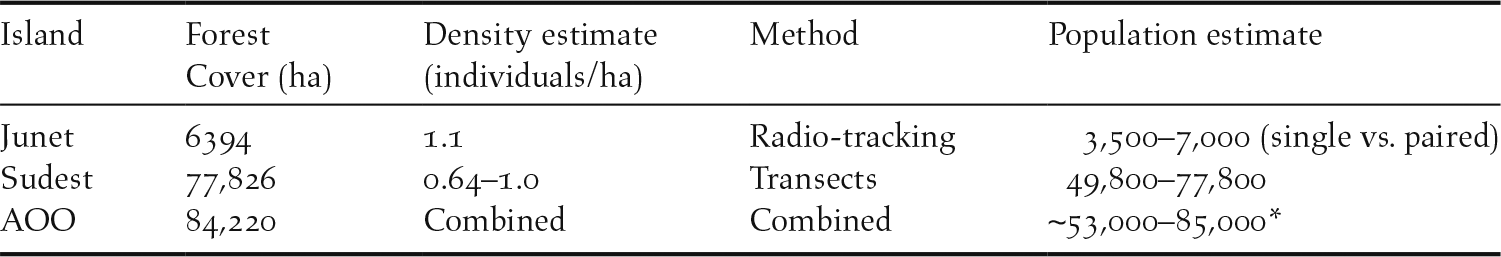

The global forest change data for the year 2000 revealed over 84,000 hectares (842 km2) across the EOO of this species had > 10% canopy cover (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Potapov, Moore, Hancher, Turubanova, Tyukavina, Thau, Stehman, Goetz and Loveland2013). The estimated populations that could be supported across this area of occupancy (AOO) are presented in Table 1. However, the total global population estimate at the lower end of this scale would be considered the most prudent (∼50,000 individuals), given the potential for lower population densities in particular circumstances/areas (e.g. indicated by the lower density of 0.64/ha on Sudest), and for unpaired individuals that could occur with a sex bias towards males.

Table 1. Population estimates for each island and the total area of occupancy (AOO) using density estimates from radio-tracking and transects.

* The lower population estimate would be the most judicious given the evidence for bias in the sex ratio toward males (see capture data), and the potential for lower densities observed on the largest island, Sudest (IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee 2017).

Movements

Tagula Honeyeaters are highly energetic birds, incessantly moving and calling throughout the day. During radio-tracking, it was not uncommon for followed individuals to move from one side of their home range/territory to the other within a single flight. Whilst such movements were typically through vegetation cover, a previous observation was made of an individual crossing a grassland gap of approximately 100 m to a small patch of regrowth on Sudest Island in 2013. However, this species was not amongst the species observed crossing water (2013–2016). Observations of several colour-banded birds around the village of Araetha (Sudest Island) a year after banding (2014) in the vicinity of the banding location, suggest Tagula Honeyeaters are residents. This is corroborated by the resighting of a banded bird in the study area on Junet Island in 2016, which was banded in a previous year (2013–2014).

Nest

We made the first observations of nests of this species during the visit to these islands in 2016. Both nests consisted of simple cups hung by the rim with spider webs in distally located branch forks. One recently disused nest (monitored) was destroyed on retrieval from an outer fork approximately 7–8 m up a 15 m tree. However, inspection of the torn nest revealed it was constructed of materials in agreement with the following. The second nest was located in the ultimate fork of an understorey tree overhanging a riparian embankment. Thick canopy sheltered the nest site from above. The nest was 3 m above the steep riparian embankment. The diameter of the measured nest was 52 mm (internal) to 72.6 mm (external) with a depth of 45 mm (internal) to 84.6 mm (external). In both nests, the internal lining was composed entirely of fine white plant seed comas laid into a cup of predominantly palm fibres with some fine grass. These were laid in an outside layer that was constructed from dead brown leaves joined with spider webs. Nests were further adorned with many green spider egg casings, creating a well-camouflaged appearance. The two nests were encountered in December. One had recently fledged chicks and one was found two days before fledging and subsequently measured when vacated (Figure 3e-g).

Breeding observations and fecundity

The observed active nest contained two nestlings past the pin-break stage, which fledged two days after observations. The adult male of this pair did not have a brood patch, supporting female only incubation. Both adults were observed feeding the nestlings. Observations of three different pairs feeding recently fledged chicks all involved only a single fledgling. Two of these were in December on Sudest Island in 2013 and one was in November 2014 on Junet Island.

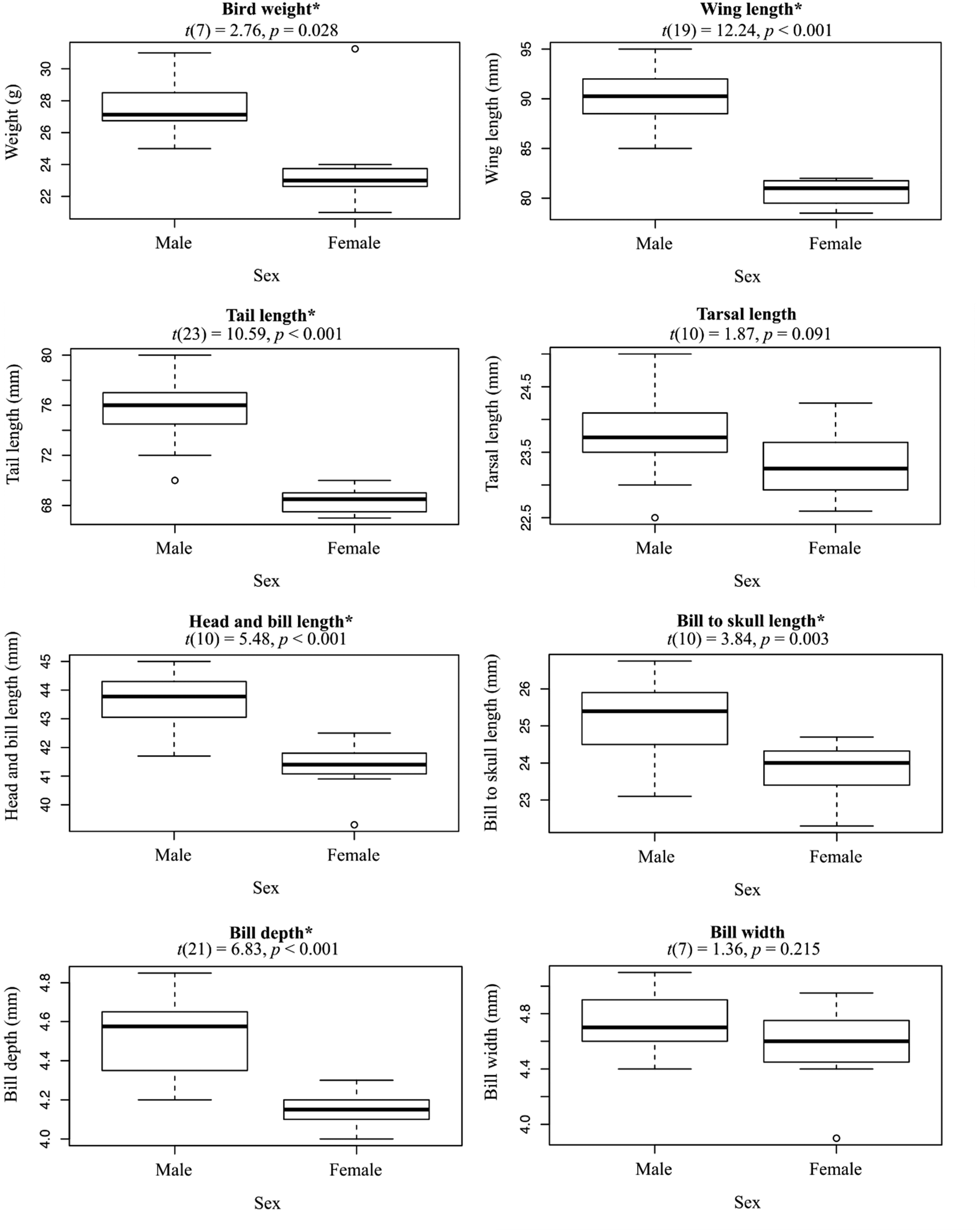

Morphology and external features

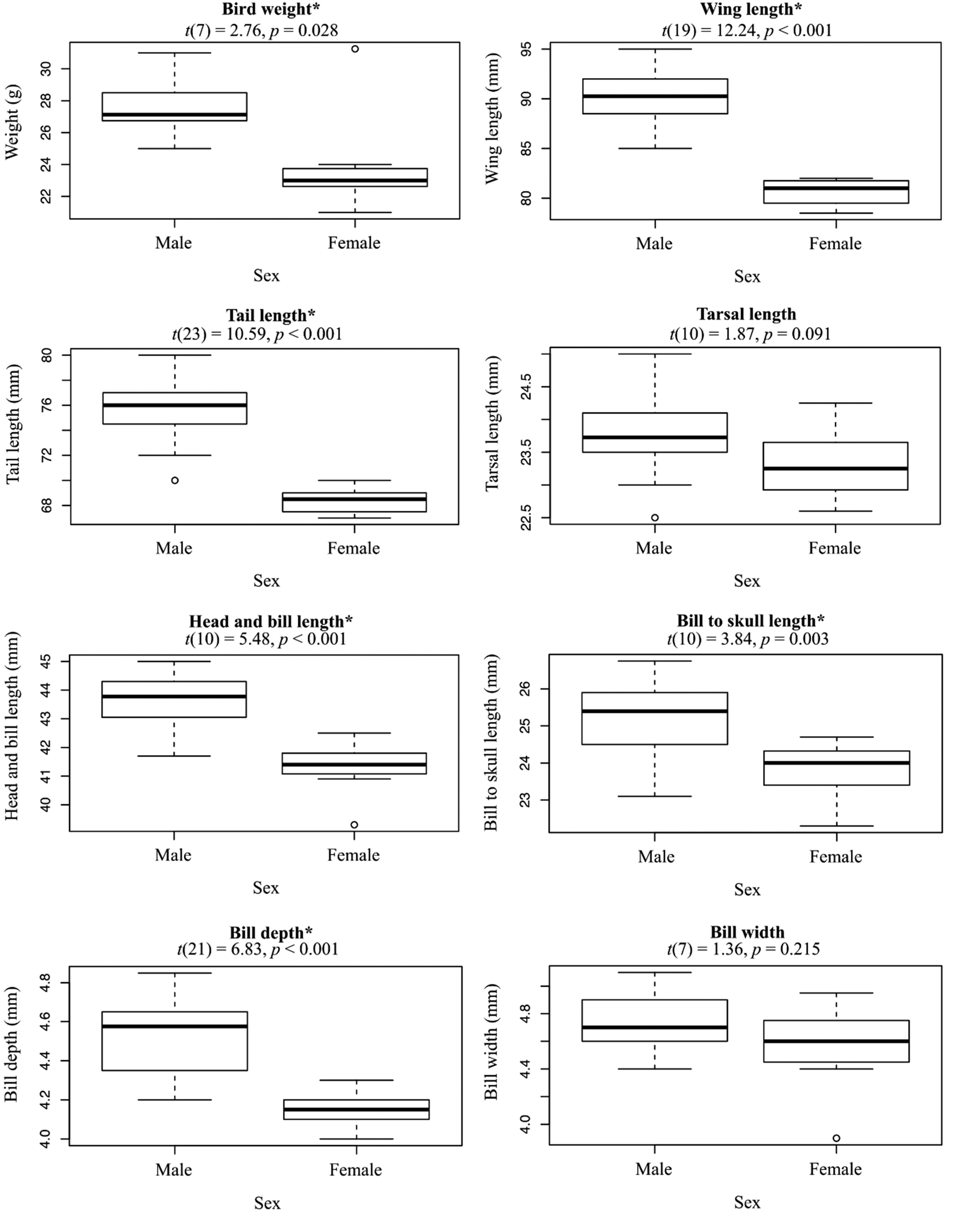

We captured (n = 37) and sexed (n = 29) Tagula Honeyeaters across the two islands comprising the distribution of the species (Sudest and Junet Islands). More males (n = 22) than females (n = 7) were caught. Diagnostic features of this relatively large-bodied species included the slender, elongated bill (dark-horn coloured), grey forehead and lores and the rounded yellow auricular patches that fail to meet the indistinct rictal streaks. Individuals also have a yellow wash to underwing coverts and breast plumage (Figure 3). Observations of recently fledged birds suggested they had darker eyes and lighter bills than adults (n = 5). Differences between the sexes in these particular features could not be determined. However, Welch’s T-tests supported males were significantly larger than females in all morphometric measures, with the exception of bill width and tarsal length (Figure 4). To aid in analyses of metapopulation processes, we excluded females from a comparison of standard morphological features between the two island populations in the distribution. T-tests did not support a difference in male morphometric measurements between the two island populations (Table S1). Moult of the remiges and rectrices were observed in 19 of 33 inspected individuals, two of the moulting individuals were in late November and the remaining 17 in December. Of the moulting individuals, 11 were in late stage moulting, replacing the primary flight feathers 7 to 10.

Figure 4. Differences between sexes in the morphometrics of Tagula Honeyeaters M. vicina, showing variation between males (n = 22) and females (n = 7). The results of Welch’s T-tests for differences between the sexes in each morphometric are displayed above each box plot. Asterisks (*) are used to denote support for significant difference in the means (α = 0.05).

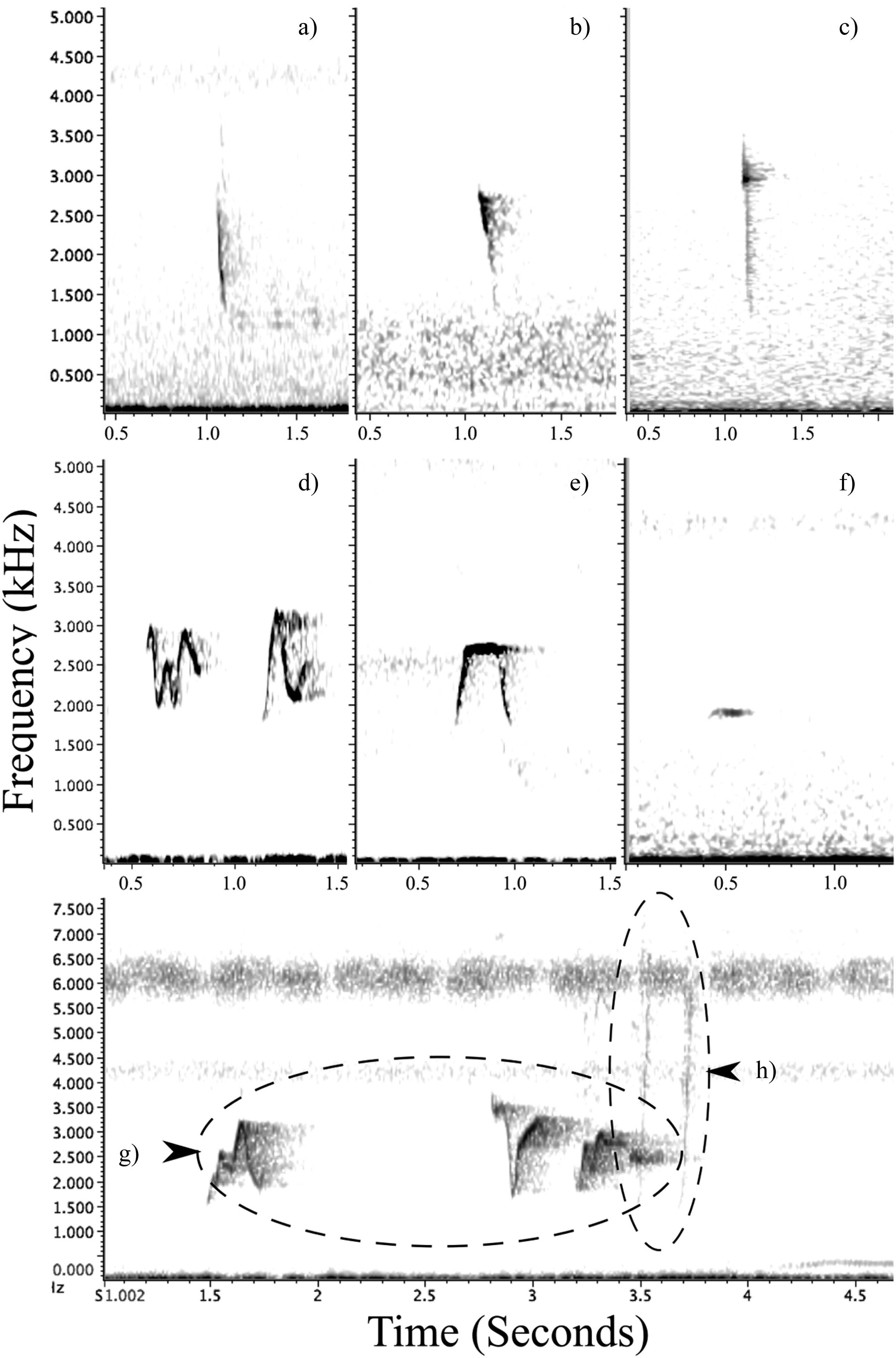

Vocal behaviour

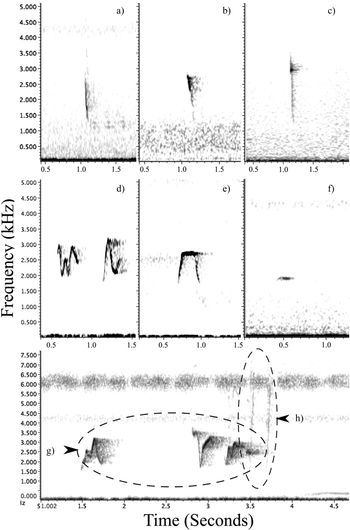

Members of this species are prolific callers and pairs maintained contact by calling throughout the day. It could not be determined whether the different calls were linked to the sex of the individuals. Observations of calling birds indicated that one of the pair often had a deeper-pitched call. This species had a variety of vocalisations used in different situations. Those noted during this study ranged from: a “chip/plick” call similar to what has been observed in congeners (Figure 5a-c); the distinctive “where are you” contact call, also likened to “cheerio” (Pratt and Beehler Reference Pratt and Beehler2014; Figure 5d, e, g); a quiet, short monotonic whistle (Figure 5f); and a sharp high-pitched “wit-wit” conflict call often given continuously when chasing conspecifics (Figure 5h). Contact calls were the most numerous vocalisation heard and were a clear whistle comprised of short and fast undulations of one to six inflections, usually fewer. The initiating contact call and the response by a partner often differed in length and undulations, for example, the typical three syllables used in an initiating call (“where-are-you”) versus a two-syllable response (a repeat of the end; “are-you”). Contact calls were characteristically between 1,250 and 3,583 Hz with average maximum frequency (Fmax.) of 3,036 ± 72 SE Hz and minimum frequency (Fmin.) of 1,551 ± 47 SE Hz (n = 15 individuals). The mean duration of contact calls was 0.31 ± 0.01 seconds that ranged over 1,485 ± 62 SE Hz (n = 15 individuals).

Figure 5. The Tagula Honeyeater produces a range of different vocalisations, amongst these is the typical “chip/plick” vocalisation heard in other Microptilotis species (top row); a = M. vicina (Sudest Island, Author), b = M. cinereifrons (Central Province, Gregory 2013), c = M. analogus (Alotau, Author). The most prominent vocalisations are whistling contact calls, which range in complexity from those that are made up of a single inflection to those typically containing up to six (labelled as d, e and g). The species also emits a more subtle and short monotonic whistle, “pu” (labelled as f), as well as a double sharp “wit-wit” vocalisation during intraspecific chasing/competition, such as occurs at territorial boundaries (the faint vocalisation labelled as h).

Threats

This species was found to be tolerant of habitat disturbance, possessing a robust population across the two islands. No immediate threats to the species were identified during the study. Natural predators such as birds (e.g. Variable Goshawk Accipiter hiogaster and Spangled Drongo Dicrurus bracteatus) and the Brown Tree Snake (Boiga irregularis) occur on these islands, as do introduced mammals such as rodents, cats and dogs. However, the distribution, which is limited to two close island populations, makes this species more vulnerable to stochastic environmental events and the cumulative impacts of change.

Discussion

The Tagula Honeyeater is endemic to Junet and Sudest Islands (∼84,000 ha). On these islands, it is a commonly encountered species in a diversity of disturbed and natural habitats, where it forages for arthropods, fruit and nectar in the canopy and understorey layers. This study reports on the first investigation of a Microptilotis or Meliphaga species home range using radio-telemetry, elevating it to one of the better-known species in the genus, with regard to spatial use. Individuals were range residents and pairs were estimated to occupy an average territory size of 2 ha at this time of year. Population estimates in 2016 based on the observed density were between 53,000 and 84,000 individuals across the two islands but a cautionary approach to the likelihood of variable densities and sex bias would support an estimate nearer to or below 50,000 individuals. The distinctive morphology and newly described vocalisations support the species-level recognition. Localised impacts from extreme environmental events or rapid forest cover change remain a threat given the species has a very restricted global distribution limited to only two small islands.

The distribution of Tagula Honeyeaters is perplexing given it does not extend to nearby and adjoining islands that support similar habitat. The generalist behaviour and wide distribution across different habitats suggest the species could be in the early stages of insular evolution and should be dispersive (Wilson Reference Wilson1961, Ricklefs and Bermingham Reference Ricklefs and Bermingham2002, Jønsson et al. Reference Jønsson, Irestedt, Christidis, Clegg, Holt and Fjeldså2014). This species is also expected to be both mobile and adaptable, due to their presence in areas regularly subject to clearing for gardens that would drive ongoing adjustment of individual territories. Despite not being among the species commonly observed crossing water gaps, it was observed crossing forest gaps and possesses many of the broad characteristics that indicate individuals could potentially cross the narrow distances between close islands (Diamond Reference Diamond1970, Mayr and Diamond Reference Mayr and Diamond2001).

These observations support that the limited distribution is likely due to other factors restricting establishment on these islands. One possible explanation is that resource bottlenecks occur on the smaller islands during extreme weather events. Droughts are typically associated with El Niño events in the south-west Pacific (Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology 2017) and rainfall patterns are thought to be strong determinants of new growth, nectar, fruit and insect abundance in tropical forests (e.g. van Schaik et al. 1993, Novotny and Basset Reference Novotny and Basset1998, Williams and Middleton Reference Williams and Middleton2008, Butt et al. Reference Butt, Seabrook, Maron, Law, Dawson, Syktus and McAlpine2015). Consequently, rainfall restriction during drought years can create resource bottlenecks that are thought to limit the abundance and population size of tropical rainforest birds (Williams and Middleton Reference Williams and Middleton2008). Secondly, cyclones can also directly reduce island bird populations (e.g. McCallum et al. Reference McCallum, Kikkawa and Catterall2000) and can dramatically reduce important nectar and fruit supplies for birds (Wiley and Wunderle Reference Wiley and Wunderle1993, Wunderle Reference Wunderle1995, Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Pias and Vinson2008). They are also likely to cause an immediate reduction (albeit potentially short-lived) in insect abundance through mortality (Schowalter Reference Schowalter2012). Both cyclones and droughts are regular occurrences on the islands of the Louisiade Archipelago (Goulding et al. Reference Goulding, Moss and McAlpine2016). Furthermore, the extensive use of fire during drought periods can affect a greater proportion of smaller, more disturbed islands (e.g. Johns Reference Johns1989). Only the two larger islands might have sufficient resource reserves to sustain viable populations of this species through such events; especially for such an active tropical lowland species that would be expected to have a high basal metabolic rate and high energy requirements (McNab Reference McNab1994, Reference McNab2016). A further consideration is that Junet Island is the smallest island on which this species was found, supporting an estimated population between ∼3,500 and 7,000. This could be the minimum viable population size for the species, precluding it from long-term persistence on smaller nearby islands (T. Pratt pers. comm. 2018). Further evidence of persistent absence from Nimoa and Grass Islands is needed, given the species’ potential mobility and the proximity of these small islands to Junet and Sudest Islands.

It is unlikely that competitors or predators are restricting factors on these islands (unless their impacts are density related) because the bird diversity is comprised of subsets of those species found on Sudest Island. However, potential variation in vector and parasite assemblages across these islands could be a restricting factor. Wide variation in host-parasite assemblages and prevalence has been noted elsewhere amongst nearby islands in archipelagos (Fallon et al. Reference Fallon, Bermingham and Ricklefs2003, Levin et al. Reference Levin, Zwiers, Deem, Geest, Higashiguchi, Iezhova, Jiménez-Uzcátegui, Kim, Morton, Perlut, Renfrew, Sari, Valkiunas and Parker2013, Olsson-Pons et al. Reference Olsson-Pons, Clark, Ishtiaq and Clegg2015). Consequently, different parasite burdens could be further constraining the establishment of other island populations of the Tagula Honeyeater.

The observations of territorial conflict between pairs of honeyeaters near estimated home range boundaries support that the estimates were representative. However, these field observations indicate the AKDE modelling may have in fact inflated the 95% estimates for some individuals with closer to 50% home ranges seeming more representative, particularly for individual #40260. This is likely due to the lower number of location fixes which were collected over a short time before this individual dropped the radio-transmitter. The smaller home ranges were also supported by the non-overlapping 50% home range estimates of the separate pairs. However, it was considered prudent to use the 95% home range estimates in the population census to give a conservative estimate and allow for variation in population density that may occur across the two islands and across time. It is important to note that the observed territories may not be representative of spatial use at other times of the year and may in fact represent more temporary breeding territories (cf. home ranges).

Sympatric species occur on the main island of New Guinea and Australia and this has resulted in both direct competition between congeners and the division of the habitats used amongst species, either with elevation or microhabitat use (Christidis and Schodde Reference Christidis and Schodde1993, Pratt and Beehler Reference Pratt and Beehler2014). As the only representative of the genus on these islands (Pratt and Beehler Reference Pratt and Beehler2014, pers. obs.), this species appears to have been able to broaden micro-habitat use in the absence of other closely related species and with fewer competitors. Consistent with ecological theory relating to bird densities on islands (Crowell Reference Crowell1962, Blondel Reference Blondel2000), this diverse habitat and resource use has allowed high population densities, conferring a level of resilience to the species. Overall, the broad diet of the species is similar to other widespread Meliphagidae spp. with invertebrates forming a large portion of a diet that is supplemented with nectar and fruit resources (Ford Reference Ford, Higgins, Peter and Steele2001, Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Bonan, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017b).

Whilst only two Tagula Honeyeater nests were found, they were identical in the materials used and construction. Nest architecture has been be used to inform phylogenetic relationships (Sheldon and Winkler Reference Sheldon and Winkler1999, Zyskowski and Prum Reference Zyskowski and Prum1999, Irestedt et al. Reference Irestedt, Fjeldså and Ericson2006) but the nest of the suspected close relative, the Mimic Honeyeater, has yet to be described (although see Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017a). However, all the described nests of other species within the clade are similar in placement, materials and architecture to the observed Tagula Honeyeater nests (Beruldsen Reference Beruldsen1980, Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Peter and Steele2001), in particular in the use of the white plant seed comas as lining (e.g. Campbell and Barnard Reference Campbell and Barnard1917, Campbell Reference Campbell1920). Variation in materials might be expected with the variation in available nest materials in different habitats but the overall similarities between species support the close nesting relationships in this group.

Although not observed directly, the limited observations of nests and fledglings suggest a clutch size of one or more likely two eggs. This is the typical clutch size for most Meliphagids, which can range from only one in old island endemic species (e.g. Gymnomyza species; Stirnemann et al. Reference Stirnemann, Potter, Butler and Minot2016) to occasionally up to three or four in relatively closely related species such as the Lewin’s Honeyeater M. lewinii (Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Peter and Steele2001, Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Bonan, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017b). Though a small clutch size might be expected for an old island endemic species (Blondel Reference Blondel2000, Covas Reference Covas2012), supporting a slow life history and the threat of protracted extinction lags (Sæther et al. Reference Sæther, Engen, Møller, Weimerskirch, Visser, Fiedler, Matthysen, Lambrechts, Badyaev, Becker, Brommer, Bukacinski, Bukacinska, Christensen, Dickinson, Du Feu, Gehlbach, Heg, Hotker, Merila, Nielsen, Rendell, Robertson, Thomson, Torok and Van Hecke2004, Reference Sæther, Engen, Møller, Visser, Matthysen, Fiedler, Lambrechts, Becker, Brommer, Dickinson, Du Feu, Gehlbach, Merila, Rendell, Robertson, Thomson and Torok2005, Covas Reference Covas2012); the clutch size of this species does not indicate a deep history of insular evolution. This might be expected for the species, given it occurs on what are nearly land-bridge islands that are likely to have been very close to the main island of New Guinea during past glacial maxima (e.g. Reeves et al. Reference Reeves, Bostok, Ayliffe, Barrows, De Deckker, Devriendt, Dunbar, Drysdale, Fitzsimmons, Gagan and Griffiths2013). However, further data on clutch sizes and survival rates are needed to confirm the potential threats associated with low fecundity or survival rates.

The high number of individuals undergoing late stage-moult during late November and December indicate the peak breeding period to be drawing to a close at this time of year, given post-breeding moult would be expected in the species (Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Peter and Steele2001, Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Bonan, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017b). This would indicate Tagula Honeyeaters follow a protracted breeding season similar to elsewhere in the lowland tropics of the Australo-Papuan region, but one that is expected to be primarily between August and January (Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Peter and Steele2001).

This species’ unique morphology supports that it is distinct from the closely related Graceful and Mimic Honeyeaters. The limited information supports that Tagula Honeyeaters are larger than Mimic Honeyeaters, as indicated by wing lengths (Salomonsen Reference Salomonsen1966, Coates and Peckover Reference Coates and Peckover2001) but similar to the nominate race in bird weights (Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017a). They are also much larger than Graceful Honeyeaters in all standard measures (Rothschild and Hartert Reference Rothschild and Hartert1912, Hardy and van Gessel 1994, Fisher and Fisher Reference Fisher and Fisher1996).

It is interesting that unique morphological features such as the obvious grey forehead in addition to the lores, which obscure the gape, have not been given greater attention since the description of the species (Rothschild and Hartert Reference Rothschild and Hartert1912). These features appear quite distinct from congeners (Rand Reference Rand1936).

Vocal characteristics of the Tagula Honeyeater are also quite distinct. Few similarities exist beyond the typical “chip/plick” call (Figure 5a-c) which is noted in many Meliphaga and Microptilotis species, including the suspected closely related species in the clade (Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Peter and Steele2001, Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Bonan, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017b, xeno-canto 2017). Available information on the Mimic Honeyeater do not support close similarities in vocal characteristics between these two suspected closely related species, although the described disyllabic vocalisation deserves investigation (Pratt and Beehler Reference Pratt and Beehler2014, Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Christidis, Ford, Del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and De Juana2017a). Further supporting evidence for the affinities and the variety of vocalisations are needed for many of these poorly known New Guinean species. Remarkably, a divergent member of the clade, the White-lined Honeyeater M. albilineata (Christidis and Schodde Reference Christidis and Schodde1993, Norman et al. Reference Norman, Rheindt, Rowe and Christidis2007, Joseph et al. Reference Joseph, Toon, Nyari, Longmore, Rowe, Haryoko, Trueman and Gardner2014), has vocal qualities and call characteristics extremely similar to those of the Tagula Honeyeater (Higgins et al. Reference Higgins, Peter and Steele2001, Miller and Wagner Reference Miller and Wagner2014).

Both climate change and habitat change have the potential to facilitate changes in species distributions, including invasive species, vectors, parasites and pathogens (Lafferty Reference Lafferty2009, Sekercioglu et al. Reference Sekercioglu, Primack and Wormworth2012, Sehgal Reference Sehgal2015). Several invasive bird species are already established in parts of Melanesia and Australia. Species such as the invasive House Sparrow Passer domesticus, the Indian Myna Acridotheres tristis and the European Starling Sturnus vulgaris are spreading in the Australasian region (Dutson Reference Dutson2011, Pratt and Beehler Reference Pratt and Beehler2014). The House Sparrow is already present in the nearby town of Alotau, on the main island of New Guinea (pers. obs.). There has also been a single unverified report of the Indian Myna from this location (Pratt and Beehler Reference Pratt and Beehler2014). These species thrive in disturbed habitats and undoubtedly will arrive on the larger Louisiade Islands at some time in the future. Of concern is the potential for these species to not only compete with the local avifauna but also deleteriously alter the dynamics of host-parasite relationships of birds in these islands, to the detriment of species such as the Tagula Honeyeater (Marzal et al. Reference Marzal, Ricklefs, Valkiunas, Albayrak, Arriero, Bonneaud, Czirják, Ewen, Hellgren, Horáková, Iezhova, Jensen, Krizanauskiene, Lima, De Lope, Magnussen, Martin, Møller, Palinauskas, Pap, Perez-Tris, Sehgal, Soler, Szöllösi, Westerdahl, Zetindjiev and Bensch2011, Clark et al. Reference Clark, Olsson-Pons, Ishtiaq and Clegg2015).

This study allows a cautious assessment of this ‘Data Deficient’ species. A change of status to ‘Least Concern’ (LC) is suggested based upon the new information presented. Knowledge of the species does not indicate that it is undergoing a rapid reduction in population size that would meet the thresholds for inclusion in a threatened category under criteria A1-4 (subcriteria a-e). The species’ EOO and AOO do meet the geographical range criteria (B1and B2) for inclusion in a threatened category. However, the species’ broad habitat use and apparent tolerance of habitat disturbance, do not show that it meets the condition of being impacted by severely fragmented habitat or it being threatened by a very low number of locations (condition a). Whilst it is likely that there will be a further slow deterioration in the quality of habitat (condition b[iii]), there is little support for the other conditions of the geographical range criteria for inclusion in a threatened category. Furthermore, the relatively high population estimate for the species does not support inclusion based upon criteria C and D (relating to small population size). Monitoring of this species is advisable given the potential for change in these islands. However, the available knowledge of current threatening processes across the island distribution of this species does not support that it is close to qualifying or likely to qualify in the near future for a threatened category (IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee 2017).

Limitations

A comparatively low number of Tagula Honeyeaters were tracked in a single location in this study. Although not ideal, these difficult to obtain observations were enough to elevate this species to one of the better-known species in the genus with regard to spatial habitat use. However, we believe a greater number of observations would improve the accuracy of the continuous time movement models. Furthermore, more observations and surveys would improve the value of our findings, particularly with regard to time of year and changes over the temporal scale. This is particularly pertinent for determining whether the species is territorial outside the breeding season or whether spatial use becomes more relaxed over larger home ranges. However, given the paucity of knowledge of this species, we consider the information presented to be robust enough to form a valuable baseline for this hitherto unknown species.

Conclusion

The observed acoustic characteristics and morphology of the Tagula Honeyeater support its current recognition at the species level. The information presented includes the first description of calls for this species and the first nest description for the Tagula Honeyeater. It also includes the first assessment of the distribution, population size, habitat use, diet and movements of this species. All of the above are important for determining the conservation status of this endemic species.

Overall, the observations indicate that the Tagula Honeyeater is a robust species most threatened by its restricted distribution subject to stochastic events. Destructive events such as droughts and cyclones are a regular occurrence in these islands, and their impacts are exacerbated by forest loss. However, since 1974, habitat loss on Sudest and Junet Islands has proceeded at a relatively slow rate, concentrated in low elevation areas of accessible forest (Goulding et al. Reference Goulding, Perez, Moss and McAlpine2018). The forests of Junet Island are under greater pressure than those on Sudest Island, with almost double the annual loss of forest cover occurring on Junet Island between 2000 and 2014 (-0.24% versus -0.12%, respectively; Goulding et al. Reference Goulding, Perez, Moss and McAlpine2018). Whilst it is a positive sign for the species that it occurs at relatively high densities and is tolerant of disturbed habitat, the ongoing loss and degradation of the forest cover on Junet Island is a conservation concern. This is likely to place greater pressure on this island population, particularly in conjunction with resource bottlenecks associated with increasingly extreme weather events and anthropogenic climate change.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095927091900025X

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Georgia Kaipu of the PNG National Research Institute (NRI), Jim Anamiato of the PNG National Museum and Art Gallery for project support and Misah Lionel and Lulu Osembo of the Milne Bay Provincial Government for project approvals. We would also like to thank the kind residents of Sudest and Junet Islands, particularly chief Peter Donney, Ralph (Poli) Adrian and the Buluge family. However, we are grateful to all the residents of the villages Hatowai, Badia, Bwailahine and Araetha, whom happily accepted us and offered support during the project. We would also like to acknowledge the support of Craig Morrison of Advanced Telemetry Systems, Ross Dwyer (UQ) for movement data analyses advice and Heather Janetzki (Queensland Museum) for collection access and advice. We would particularly like to thank T. Pratt and S. Bryant for helpful advice on an earlier version. Research was conducted with the support of The Rufford Foundation (W.G., grant numbers 14054-1, 18034-2); the Club300 Bird Protection Fund (W.G.); UQ SEES HDR Support Fund (W.G.); and Pozible project supporters (W.G., project number 181214).