Paradoxes in Organizations: The Promise and Problem of Management

In recent decades, paradox has become a core theme in organizations and management studies. In fact, some scholars say that managers’ success depends on their ability to acknowledge and address paradoxes (Schad et al., Reference Schad, Lewis and Smith2019). The notion of paradoxes in organizational studies has provided a steady stream of research since Weber, running through Simon and March (1958) and Thompson (Reference Thompson1967). In an influential review paper, Smith and Lewis (Reference Smith and Lewis2011) define the concept as “contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time” (Smith & Lewis, Reference Smith and Lewis2011:382; Lewis, Reference Lewis2000). The articles in this special issue extend the study of paradox from management studies to studies of volunteering. This introduction summarizes this approach, and also suggests a potentially useful complement to the study of paradox in volunteer-involving organizations: the “dramaturgical” methods of mid-century US scholars focus on interactions, paying attention not only to actors’ explicit and unspoken messages and assumptions, but also to how these messages carry different meanings depending on which speakers who voice them, which audiences hear them, what are the tools of communication and implementation, and the broader social scene (Burke, Reference Burke1969; Goffman, Reference Goffman1959, among others). This approach is especially useful for studying the management of volunteers, because there are so many confusing roles and audiences and moral frameworks in play all at once. Speech and action filter through them, giving suprising, paradoxical meanings to actions that managers might imagine as coherent and logical. Using the tools from the dramaturgical approach might help us see volunteer-involving organizations’ paradoxes in a more systematic way than has previously been done.

Paradox Theory in Management Studies

Management of paradoxes in organizations can be defined as an exercise in constantly living up to contradictory yet equally legitimate claims. While “dilemmas” require managers to select one option at the expense of the other, and allow managers to use an either/or approach to handle the tensions, “paradoxes” move beyond such trade offs (Fairhurst el al., Reference Fairhurst, Smith, Banghart, Lewis, Putnam, Raisch and Schad2016; Smith & Lewis, Reference Smith and Lewis2011). In a “paradox situation,” opposing claims need to be addressed simultaneously (Stoltzfus et al., Reference Stoltzfus, Stohl and Seibold2011). In March’s work (Reference March1991), managers were advised that they could not choose between exploring or exploiting, but had to choose only one (Leonard-Barton, Reference Leonard-Barton1992; Levinthal & March, Reference Levinthal and March1993; Tushman & Anderson, Reference Tushman and Anderson1986). In contrast, the contemporary paradox literature advises managers to try to cope with both exploration and exploitation, reasserting the simultaneous importance of them both in ways that would benefit the organization (Andriopoulos & Lewis, Reference Andriopoulos and Lewis2009; Raisch et al., Reference Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst and Tushman2009; Smith, Reference Smith2014; Smith & Tushman, Reference Smith and Tushman2005).

However, navigating the tensions of a paradox situation is not straightforward. Paradoxes feel uncomfortable. They can come across as a form of disorder, and therefore easily appear as threats to management and its central aspiration of order and consistency (Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016 p. 75). Instead of being paralyzed by the seemingly impossible situation, managers should, according to leading scholars, embrace the paradox by seeking an both/and approach, treating the contradictions as complementary and mutual enabling, and in doing so, fuel virtuous instead of vicious cycles (e.g., Lewis, Reference Lewis2000; Smith & Lewis, Reference Smith and Lewis2011).

Vicious cycles emerge when managers fail to give equal attention to both poles, and instead favor one pole at expense of the other, thereby creating conflict and negative tensions between the two poles (Lewis & Smith Reference Lewis and Smith2022; Lewis & Smith, Reference Lewis and Smith2022).

Since then, several studies has investigated how vicious cycles can be changed to virtuous cycles and thereby promote learning and transformation (Chen, Reference Chen2002; Edgeman et al., Reference Edgeman, Hammond, Keller and McGraw2020; Farjoun, Reference Farjoun2010; Huq et al., Reference Huq, Reay and Chreim2017; Miron-Spektor et al., Reference Miron-Spektor, Gino and Argote2011). To foster virtuous cycles, scholars call for strategies of differentiation and integration. “Differentiation” involves recognizing and conserving the distinction’s importance; “integration” means “identifying linkages” between them (Smith & Tushman, Reference Smith and Tushman2005, p. 527; Andriopoulos & Lewis, Reference Andriopoulos and Lewis2009; Lewis & Smith, Reference Lewis and Smith2022).

In the last decade, the research field has covered a wide spectrum of organizations and contrasting dichotomies, such as, just to name a few: rationality versus intuition in innovative companies (Calabretta et al., Reference Calabretta, Gemser and Wijnberg2017); flexibility versus efficiency in one global corporation (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Goldoftas and Levine1999); individuality versus collectivity in small musical ensembles (Murnighan and Conlon Reference Murnighan and Conlon1991); inclusion versus exclusion in trade associations (Solebello et al., Reference Solebello, Tschirhart and Leiter2016) (for overviews, see various review articles; Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2018; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016; Schad et al., Reference Schad, Lewis, Raisch and Smith2016; Fairhurst et al., Reference Fairhurst, Smith, Banghart, Lewis, Putnam, Raisch and Schad2016). The study of paradoxes in management has developed into a well established research field with its own overarching perspectives and underlying assumptions that traverse the many different empirical cases and theories.

Critiques of this perspective followed. Poole and Van de Ven (Reference Poole and Van de Ven1989, p. 563) argued, three decades ago, that the field uses the term paradoxes “loosely, as an informal umbrella for interesting and thought-provoking contradictions of all sorts.” Recent scholarship cautions that by addressing so many empirical phenomena and levels of analysis, the concept of paradox runs the danger of becoming too inclusive, either gathering almost all complex situations that have different expectations, or else becoming so general that it loses the sight of what makes paradoxical situations specific (see Schad et al., Reference Schad, Lewis, Raisch and Smith2016; Li, Reference Li2016). The concept risks turning into a vague umbrella term, at the expense of conceptual precision and detail (also noted by Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016; Smith, Reference Smith2014), thus losing its power and potentially missing critical insights (e.g., Fairhurst et al., Reference Fairhurst, Smith, Banghart, Lewis, Putnam, Raisch and Schad2016; Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016; Schad et al., Reference Schad, Lewis, Raisch and Smith2016; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Erez, Jarvenpaa, Lewis and Tracey2017).

On the other hand, scholars have claimed the opposite, namely that the research field has developed into a closed research unit with a too narrow conception of how paradoxes should be defined and how it should be embraced. Cunha and Putnam have argued that this has led to a “premature convergence on theoretical concepts, overconfidence in dominant explanations and institutionalizing labels that protect dominant logics” (Cunha & Putnam, Reference Cunha and Putnam2019, p. 96). They criticize the fields converging on both-and approaches as the most effective way to manage contradictions within organizations, instead of examining a repertoire of different types of responses to the challenge of paradoxes. They argue that to prevent this to happen, the research field has to avoid narrow theory building (see also Seidl et al., Reference Seidl, Lê and Jarzabkowski2021).

Together, the different types of criticism represent a paradox of its own, claiming that the research field should live up to two contradictory claims, by being both more closed and more open, leaving the paradox scholars in the same impossible situation as the managers they study. However, as Schad et al. note (Reference Schad, Lewis and Smith2019) both centripetal and centrifugal forces can help develop the field. This issue could be, itself, an example of this. On the one hand, it will take the established research field’s definition of paradoxes as a stepping stone, for doing new investigations. At the same time, it will introduce new theories, empirical evidence, and methods to the field of paradox studies.

Taking the established field’s definition of paradoxes as a stepping stone, this issue will show how the concept of “paradox” can be useful for studies of volunteer management. It will show that navigating through complex and ambiguous situations is not so much a matter of choosing an either/or approach, as recognizing the importance and legitimacy of both demands, and identifying situations where they can benefit from one another.

Paradoxes in Volunteer Management Research

Some researchers argue that the literature on volunteer management relies on rationalistic and instrumental forms of “management thinking (Sillah, Reference Sillah2022, Alfes et al., Reference Alfes, Antunes and Shantz2017, for comprehensive reviews see also Maier et al. Reference Maier, Meyer and Steinbereithner2016; Maier & Meyer, Reference Maier and Meyer2011; Studer & Schnurbein Reference Studer and von Schnurbein2013, Brudney & Meijs Reference Brudney and Meijs2009; Brudney et al. Reference Brudney, Meijs and van Overbeeke2019)”. Angela Marberg and her colleagues found that within the last decade there has been a remarkable increased use of vocabulary associated with managerial professionalism and measurable outcomes within the studies of management of volunteers. The central topics of this managerialist discourse are effectiveness, efficiency, resources, and strategy. It emphasizes that managers of volunteers should increase efficiency and effective accomplishment of the organization missions (Marberg et al., Reference Marberg, Korzilius and van Kranenburg2019). Some of this rationalistic research prescribes a “one size fits all” answer, while other research prescribes a more conditional approach (Meijs & Ten Hoorn Reference Meijs, Ten Hoorn and Liao-Troth2008; Macduff et al., Reference Macduff, Netting and O’Connor2009; Brudney & Meijs, Reference Brudney and Meijs2014). Both prescribe a formal and rational approach to ‘‘managing’’ volunteers (see ).

In contrast to this trend, a growing body of research has focused on the uniqueness of volunteers’ positions in voluntary organizations (Englert & Helmig, Reference Englert and Helmig2018; Studer, Reference Studer2016). The volunteer is neither employee nor private person; neither professional nor amateur; neither inside the organization nor entirely out of it. This all challenges any fixed models for solving dilemmas, since dilemmas are built into the very position itself (Ashcraft & Kedrowicz, Reference Ashcraft and Kedrowicz2002; Ganesh & McAllum, Reference Ganesh and McAllum2012; Kramer, Reference Kramer2011; Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Meisenbach and Hansen2013; McNamee & Peterson, Reference McNamee and Peterson2014).

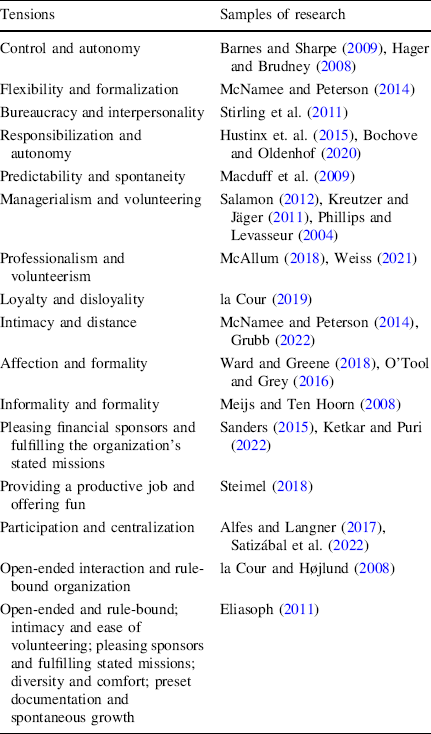

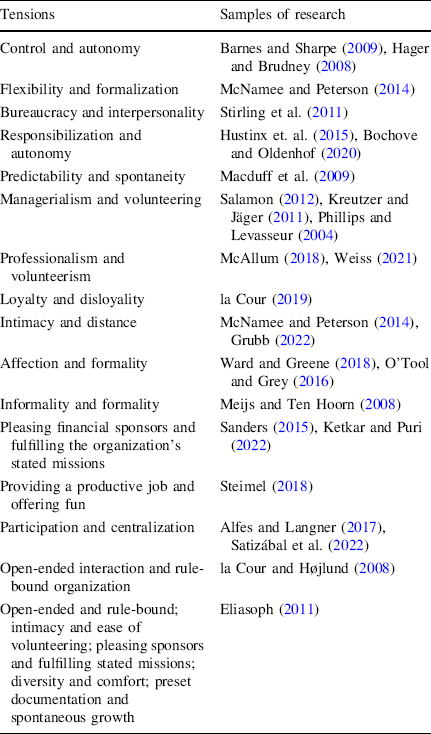

Indeed, already three decades ago, Ilsley saw the volunteers’ nebulous position in organizations, saying that balancing between professional procedures and respect for volunteers’ spontaneity is a central challenge (Ilsley Reference Ilsley1990, p. 89, see also Pearce, Reference Pearce1993). Since then, a great deal of research has focused on tensions and contradictions that are specific for the organization of volunteers, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Common tensions in volunteer management literature

Tensions |

Samples of research |

|---|---|

Control and autonomy |

Barnes and Sharpe (Reference Barnes and Sharpe2009), Hager and Brudney (Reference Hager, Brudney and Liao-Troth2008) |

Flexibility and formalization |

McNamee and Peterson (Reference McNamee and Peterson2014) |

Bureaucracy and interpersonality |

Stirling et al. (Reference Stirling, Kilpatrick and Orpin2011) |

Responsibilization and autonomy |

Hustinx et. al. (Reference Hustinx, De Waele and Delcour2015), Bochove and Oldenhof (Reference van Bochove and Oldenhof2020) |

Predictability and spontaneity |

Macduff et al. (Reference Macduff, Netting and O’Connor2009) |

Managerialism and volunteering |

Salamon (Reference Salamon2012), Kreutzer and Jäger (Reference Kreutzer and Jäger2011), Phillips and Levasseur (Reference Phillips and Levasseur2004) |

Professionalism and volunteerism |

McAllum (Reference McAllum2018), Weiss (Reference Weiss2021) |

Loyalty and disloyality |

la Cour (Reference Cour2019) |

Intimacy and distance |

McNamee and Peterson (Reference McNamee and Peterson2014), Grubb (Reference Grubb2022) |

Affection and formality |

Ward and Greene (Reference Ward and Greene2018), O’Tool and Grey (Reference O’Toole and Grey2016) |

Informality and formality |

Meijs and Ten Hoorn (Reference Meijs, Ten Hoorn and Liao-Troth2008) |

Pleasing financial sponsors and fulfilling the organization’s stated missions |

Sanders (Reference Sanders2015), Ketkar and Puri (Reference Ketkar and Puri2022) |

Providing a productive job and offering fun |

Steimel (Reference Steimel2018) |

Participation and centralization |

Alfes and Langner (Reference Alfes and Langner2017), Satizábal et al. (Reference Satizábal, Cornes, Zurita and Cook2022) |

Open-ended interaction and rule-bound organization |

la Cour and Højlund (Reference Cour and Højlund2008) |

Open-ended and rule-bound; intimacy and ease of volunteering; pleasing sponsors and fulfilling stated missions; diversity and comfort; preset documentation and spontaneous growth |

Eliasoph (Reference Eliasoph2011) |

This (inevitably incomplete) overview of a broad repertoire of different tensions, investigated through multiple theories and multiple methods, paints a rich picture of complexity. Even though the literature appears fragmented and without any central paradoxes to lead the research, it illustrates that a tension-centered perspective has been developed and applied to a broad range of volunteer studies. These various tensions show diverse ambiguities involved in attempts to organize and manage volunteers. Together and individually, these studies challenge the prevailing dogma of rational managerialism: not only does rational management neglect complexity, complexity is often a result of the very attempt to manage volunteers through formality and rationality. Thus, some studies argue that managers should “turn down the volume” on rational management discourse (Barnes & Sharpe, Reference Barnes and Sharpe2009). Or management should “filter” rational management practices so they respect the autonomy of the volunteers (Stirling et al., Reference Stirling, Kilpatrick and Orpin2011) and contribute to volunteers’ experience of self-determination (van Schie et al., Reference van Schie, Güntert and Wehner2014). Others try to address one of the observed poles (Macduff et al., Reference Macduff, Netting and O’Connor2009), or emphasize the need for the management to develop a “listen and learn” attitude, to navigate the poles on a daily basis (Eliasoph, Reference Eliasoph2011; la Cour, Reference Cour2019; Satizábal et al., Reference Satizábal, Cornes, Zurita and Cook2022). This issue’s aim is to stimulate research in this direction partly by introducing to the general research field of paradox studies and presenting articles that explore how different paradoxes emerge through the attempt to manage volunteers. By showing various paradoxical situations’ different, and often contradictory, expectations that exist simultaneously and consistently over time, this issue’s articles thereby examine “paradoxical situations,” according to the standard definition of the term.

Although existing research already provides some insight in how voluntary organizations often develop styles for “navigating” the described tensions without resolving them (Eliasoph, Reference Eliasoph2011; Glaser et al., Reference Glaser, Lo and Eliasoph2020; la Cour, Reference Cour2019), embedding these tension-focused studies in paradox theory will deepen our understanding of the intrinsically paradoxical nature of managing volunteers. While some of the above mentioned studies already go beyond an “either/or”-perspective, paradox theory pushes for a more rigorous analysis of contradictory and mutually exclusive aspects of organizational demands.

A Dramaturgical Approach to Paradox

Paradoxes do not just arise out of thin air. Several studies show that paradoxes owe their origin to an increasingly complex organizational environment (Schad et al., Reference Schad, Lewis, Raisch and Smith2016; Smith & Lewis, Reference Smith and Lewis2011). Some refer to the increasing global competition, which requires organizations to operate on both a global and local scene at the same time (Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009). Others point at the fact that paradoxes stem from the increasing variety of stakeholders, that raise competing yet equally important demands (Scherer et al., Reference Scherer, Palazzo and Seidl2013). Others argue that paradoxes stem from the complexity and multiplicity of different working process and designs (Besharov & Smith, Reference Besharov and Smith2014), or from discordant roles that must be performed simultaneously (Michaud & Andebraud, Reference Michaud and Audebrand2022). These studies, and many others, show that numerous circumstances can trigger paradoxes. We miss, however, a more systematic approach for understand the relations between paradoxes and their circumstances.

Inspired by, but modifying, the American literary theorist Kenneth Burke’s (1897–1993) “pentad” of five elements (agent, act, scene, purpose, and agency) we will tease out one possibly way of systematizing the seemingly infinite paradoxes that studies have shown:

To understand parodoxes, researchers need to ask not only “What are the organization’s mandates, stated missions, and unspoken expectations—not only “why” they take form, but also, how they take form: “Who” is invoking the expectations in any specific moment? And for what audience? And with what instruments? With what historical and institutional background—what broader “scene”—in mind? By anchoring paradoxes in these different types of embodied expectations and ways of materializing, this special issue’s six articles offer a systematic way of understanding of how a polyphony of different expectations can give rise to specific forms of paradoxes.

If you are familiar with Burke’s work, you will notice that we added “audience” and subtracted "purpose” from his pentad. Why did we add “audience?” He formulated his influential “pentad” primarily to analyze public speeches. It is also often used to analyze films, novels, and other performances, so they do not include the audience in their analysis of the show. But to analyze interaction, we absolutely need to include the listener in the interaction. Why did we subtract “purpose?” We want to limit ourselves to observable phenomena, and we also want to recognize that people often have many layers of crisscrossed, contradictory purposes. Still, we start with Burke’s idea of a pentad (it is still “five,” since we subtracted “purpose” and added “audience”), because it offers a potential to systematize large numbers of organizations’ paradoxes in ways that other dramaturgical approaches do not.

In his approach, as in ours, the interesting action is in the relationships between the five elements. When paradoxes arise, they often arise when, for example, the “speaker (the “who”) does not match the expected message (the “what”) from a person who is playing that role.

The “actor”—the “who”—refers to roles within the organization: volunteer, manager, or recipient of volunteers’ aid, for example. It also can spotlight visible and/or audible demographic features of these actors, to which listeners might filter the roles: woman, teenager, African American, Chinese speaker, for example. Moving beyond manager-centered understandings, it can also include broader institutional actors, such as elite framers of missions. The reason it is important to separate our observations of the actor from the action and speech is that the same words and actions carry different meanings to listeners, depending on who is speaking or acting. The articles observe that listeners often further differentiate within categories that might all look like “manager,” for example, such as: between unpaid volunteer managers, paid volunteer managers, elected leaders who manage volunteers, and, paid social workers, and paid or unpaid health care professionals, all of whom might be work with the same group of volunteers (Eliasoph, Reference Eliasoph2011).

The “audience”—the “where”—in our addition to Burke, can be inside the organization, or they can be external audiences, such as funding agencies, voters who pay for the organization, schools and religious organizations that send volunteers, or other volunteer-involving and/or professional organizations. Even if an actor consistently says and does the same thing to different audiences, varied audiences may well hear different messages.

The “scene” refers to the broader institutions, both inside and outside the organization, that legitimate its work. Actors may or may not be fully conscious of any efforts at legitimation, but if a researcher observes that they (consciously or not) orient themselves toward some institution that affects their action, then the institution becomes relevant for the study.

The ”instruments”—the “how”—refers to whatever material objects go with the human action. Some examples include quantitative assessments of the organization, furniture, telephones, and screens. The instruments that matter here are not just “used” by actors; they shape the action. One prominent tool in highly professionalized settings is spatiotemporal in nature, whereby potential conflicts between professionals and volunteers are prevented by a consecutive temporal work organization of paid professionals and volunteers.

The pentad is not something that gets in the way of volunteer organizations; the pentad is the way. Our point is that, when taken together, the pentad is part of what defines the normative and political dimensions of volunteer-involving organizations, in a way that is similar to the ways that “street-level bureaucrats” help define their organizations’ mission, whatever the policies on paper may be (Garfinkel, Reference Garfinkel1967; Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010).

Introducing the Six Articles

Our collection spans different types of organizations and sectors (social work, health care, timebanks, and music festivals), as well as historical periods (different phases in welfare state development).

The first three articles take the broader “scene,” the (Western European) welfare state, as the main entry point, centering on voluntarism in the provision of public services within highly professionalized organizational contexts.

In “Moral elites and the de-paradoxification of Danish social policy between civil society and state (1849–2022)”, Anders Sevelsted remarkably shows how actors’ ways of trying to settle the paradoxes of one era turn into the paradoxes of the next era. In his historical analysis across a 150-year period of the role of moral elites in settling paradoxes within Danish social policy, Sevelstad shows how the “scene” affects action and vice versa. He identifies, from the beginnings of Western welfare states onwards, a fundamental “social policy paradox” between philanthropic relief based on a logic of benevolence and state-administered relief based on a social rights logic. This paradox comes from vacillations, over time, of stigmatizing public or private relief. To legitimize particular social configurations, moral elites tried to create “paradox-free” social policies through acts of classification, categorizing some groups as deserving of benefits and assigning responsibility to the family, state, or market. Sevelsted meticulously unfolds the complex and shifting dynamics of managing paradoxes between 1) different moral elite groups (“actor”), 2) changing public perceptions of deservingness (“audience”), and 3) changing views of the sectors and their role in welfare provision (“scene”). The empirical analysis reveals three historical classification orders in the Danish context: Traditional Moral Elites and the Help to Self-help Classification (1849–1891); Specialists and Rights Classification (1891–1976); Economists and Workfare Classification (1976–present). He shows that the relationship between deservingness and sector provider is historically contingent. This goes against a common assumption that the more “deserving” a group is defined as being in any historical moment, the more the state gets involved. In Jeffrey Alexander’s (2006) model of civil and noncivil spheres, a society’s “binary code” treats some people and actions as “included or excluded, pure or impure, carrying stigma or not, being civil or noncivil, just or unjust pure or impure, deserving or not,” as Sevelsted paraphrases (p. 4). Sevelstad adds an important layer to this model, saying that a society’s binary code also stigmatizes or valorizes sectors’ roles in providing aid, as well as classifying individuals and groups as pure and deserving or not, and the two classification systems work together differently in different epochs.

In “Towards a new typology of professional and voluntary care”, Anders La Cour zeroes in on the increased reliance on voluntary care in relation to professional care in the contemporary welfare mix. La Cour says that recent scholarship tends to theorize each sector’s care as distinct, each with its own essence, resulting in common understandings of professional care as “devoted to standards, accountability, equality, and bureaucracy” and voluntary care as “flexible, authentic, and individual”, or more generally between “formal” and “relational” types of care. Managers see effective collaboration between professional and voluntary care providers as complementary, with volunteers in ancillary roles vis-à-vis professionals expert roles. This growing professionalization and responsibilization of volunteers is part of wider tendencies toward performance and accountability in public welfare provision, through which formal care criteria also increasingly applies to voluntary care. Managers’ treatment of this boundary helps create conflict between professionals and volunteers. In dramaturgical terms, it is a mismatch between the actors and the action. Critical scholarship also points to the effortful “boundary-work” that maintains the difference in values and identities between the groups. La Cour, however, discerns a common yet questionable underlying core assumption in these various approaches, namely that two essentially different and pure care logics build on distinct (and even incompatible) care principles, and that tension arises from the boundary crossing between professional and voluntary care in actual care practices. The problem is that this eternally reproduces the basic logic of complementarity. To move beyond this analytical deadlock, La Cour argues that both formal and relational forms of care are intrinsic to both professional and voluntary care. Based on this foundation, researchers can examine both types of care at a more fine-grained level, by examining differences in professional and voluntary forms of care’s varied relations to the principles of both formal and relational care. La Cour shows how each form of care represents its own unique and paradoxical ways of combining formal and relational care principles. Instead of continuing to study paradoxes at the level of managing collaboration between volunteers and professionals, a more fruitful approach is to explore how they constitute their own paradoxical forms of care.

In a third paper titled “Together Yet Apart: Remedies for Tensions Between Volunteers and Health Care Professionals in Inter-professional Collaboration”, Georg von Schnurbein, Eva Hollenstein, Nicholas Arnold, and Florian Liberatore investigate the collaboration between volunteers and health care professionals in the health care institutions in Switzerland. As in other settings of public welfare provision, health care volunteers have become vital, but their inclusion in formal, highly professionalized settings also leads to tensions. Introducing the concept of interprofessional collaboration (IPC), the authors construct a new framework for scrutinizing different types of tensions, and their antecedents between volunteers and health professionals. The authors argue that the role of volunteers in IPC research has, so far, been largely neglected, despite their essential, complementary role in providing high-quality health care services. To get a subtle understanding of possible tensions, Schnurbein and colleagues analytically distinguish between four types of tensions: status conflict, process conflict, task conflict, and relationship conflict, each with specific antecedents. For instance, an unclear or unfair task division can result in status conflicts at the individual or professional group level. In addition to unraveling the complexity behind the general notion of tension between volunteers and professionals, the study also approaches these tensions from a dyadic perspective, assessing the expectations and experiences of both volunteer managers and volunteers (the authors note that by not including health professionals in their study, the more informal experience of tension in actual IPC may not have been fully captured). Overall, the volunteer managers who responded to the authors’ survey reported more tensions compared to the volunteers. In health care settings, they reported more frequent conflicts related to processes, tasks, and relationships than those related to status. The fact that they less frequently reported status conflicts might be due to volunteers’ mostly doing complementary tasks that do not interfere with the specialized professionals’ work. To put it in dramaturgical terms, the actions fit the actors. Volunteers indeed preferred minimum role overlap and clear task division. One element of the pentad that made this possible was “the material instruments:” Volunteers and paid staff’s tasks rarely took place simultaneously. Time and space became useful “instruments” for keeping action meaningful. The authors derive from these findings a paradox in IPC itself: while IPC is aimed at more effective and high-quality health care by stimulating more collaboration among various actors, the most preferred and conflict-reducing way of working is by clearly dividing and compartmentalizing professional and volunteer roles and tasks. Schnurbein et al. conclude that rather than pushing for more collaboration, managers should aim for a looser structure of “coaction”.

With the final three research papers in our special issue, we travel to a different “scene,” namely the borderland between voluntary association and market organization.

Two articles explore these borders in the “social economy” and “social enterprise”. Policy makers and publics in general imagine that volunteering in these value-based, community-oriented alternative collectivities is in competition or tension with “traditional volunteering.” This creates paradoxes for volunteer managers.

In “Paradoxes in the Management of Timebanks in the UK’s Voluntary Sector: Discursive Bricolage and its Limits”, Jason Glynos, Konstantinos Roussos, Savvas Voutyras, and Rebecca Warren coin the notion of a “timebank/traditional volunteering ‘doublet’.” While timebanking (defined as a community economy in which people exchange tasks or “services” using labor time as currency, Seyfang, Reference Seyfang2002) is considered a form of volunteering, time bank advocates eagerly distinguish it from traditional volunteering. Time banking, they say, has an ethos of reciprocity, whereas traditional volunteering is unidirectional, other-oriented helping. This tension, the authors argue, creates a “performance paradox” for managers of timebank volunteers: a challenge in promoting timebanking and recruiting timebank volunteers is to explain its distinct and innovative nature, that is, “to bring something new into being, a practice and experience that many people are not (yet) familiar with” (p. 7, emphasis in original). This need for explanation poses a paradox for volunteer management “because the (rhetorical) performance of the manager brings into existence what s/he purportedly is supposed to manage” (p. 2). Theoretically, the authors introduce two innovations into our thinking about paradox in (volunteer) management. First, while Smith and Lewis’ seminal definition of paradox only addresses contradictory dualities that already exist in organizations, Glynos and colleagues show how paradox is also “constructed in the interval between being and becoming, the space between reality and possibility” (p. 2—emphasis added). Second, they formulate paradox in discursive terms, thus reconceiving the role of timebank volunteer managers as “discursive bricoleurs” who must use various rhetorical devices to legitimize the particular form of volunteering that is the object of their management practices in opposition/alignment with a set of wider discursive structures. Drawing on political discourse theory and method, Glynos and colleagues present a highly original empirical analysis of the volunteer managers “practices of articulation,” by dissecting the performance paradox in two “offshoots”. First, the “Everywhere (in name) but Nowhere (in substance)” paradox implies that by the need to align timebank volunteering not only with the dominant frame of traditional volunteering, but also with funding imperatives of increasing the number of volunteers and activities. Thus, managers downplay the intrinsic values of timebanking (reciprocity, community building), by portraying it to various audiences as a more convenient “plug-in” way (Eliasoph, Reference Eliasoph2011) of doing traditional volunteering. In a second paradox, the formal features of a future ideal case scenario of timebanking (such as registration of time credits) would no longer be needed because the underlying values have become natural parts of a healthy community life. This is already present in managers’ experience of once active timebank members who stop registering what they do after they have befriended their comembers. Their continued reciprocal exchanges have become part of informal ties, which is perfectly compatible, as the authors note, with privatization tendencies in policy. Reinscribing it into (one-to-one) friendship furthermore tends to selectively promote some values of timebanking while marginalizing others, especially the creation of an alternative economy. In sum, volunteer managers have to position themselves constantly in relation to dominant structures and logics, ultimately navigating between “logics of cooptation” and “logics of progressive transformation”, with the present case-study mainly a story of cooptation (p. 9).

In “Professional volunteerism: Interwoven paradoxes in the management of Roskilde Festival”, Jonas Hedegaard delves into the context of a world-class music festival that primarily relies on volunteers, yet also needs to live up to highest professional and performance standards. It operates as a social enterprise, being value-based yet also requiring commercially viability. Here, volunteering takes the form of “professional volunteerism”, which Hedegaard approaches as a “locus of paradoxical tensions”. While the general tension between two poles—“volunteerism” and “professionalism”—has been well-documented in existing literature, Hedegaard sees more-than one axis. Responding to more process-oriented and practice-theoretical approaches to paradoxes and their managerial responses, he explores “knotted and bundled tensions” (Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016), “unfolding in relation to each other in a dynamic interplay between the actions of individuals and larger organizational and societal structures” (p. 4). This requires not only a “both-and” but also a “more-than” logic to fully grasp managerial responses to paradoxes. Based on a 9-months “insider action research project” covering different top and middle management teams of the festival, consisting of both volunteers and employees, hence having access to multiple actors and audiences across units and levels over a longer period, Hedegaard uncovers three pairs of paradoxical tensions: (1) Tensions between alignment and autonomy; (2) Tensions between commitment and empowerment; and (3) Tensions between performance and well-being. He describes managers’ responses to these paradoxes, showing how these can influence and activate other interwoven tensions. Resolving a paradox in one situation, often merely meant moving tensions to another place or time. Hedegaard concludes that by accepting the paradox and utilizing a “more-than” response, volunteer managers find a constructive way forward in dealing with the tensions at play.

In “Volunteers’ Discursive Strategies for Navigating the Market/Mission Tension”, Consuelo Vásquez, Frédérique Routhier, and Emmanuelle Brindamour, focus on the major fundraising campaign of the Canadian Cancer Society, as a case of nonprofit marketization’s intensification of the tension between market-based and volunteer logics. Examining communicative practices of volunteers in their everyday interactions, the authors’ focus on interaction, in contrast with the dominant literature’s focus on individual sensemaking. Discourse is here understood as “little’d’ discourses” (Alvesson and Kärreman, Reference Alvesson and Karreman2000), that is, “constellations of language, logic, and texts rooted in day-to-day actions and interactions (Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Fairhurst and Banghart2016; cited in Vásquez et al., Reference Vásquez, Routhier and Brindamour2022, p. 4).” Using conversation analysis, the authors zoom in on a specific moment in one organizing committee’s meeting, showing tension between market and volunteer orientations, the authors reveal six main approaches to navigating paradoxes, grouped under three broader categories: (1) Either-or approaches: selecting and segmenting; (2) Both-and approaches: integrating and balancing; (3) More-than approaches: reframing and transcending. They construct a processual model for navigating oppositions in interaction, which starts from varying ways of problematizing the oppositions, and moves through different discursive navigation strategies. The authors conclude that even thought the market/mission paradox is central to many present-day NPOs, it is seldom expressed directly in everyday volunteer interactions. It rather manifests itself in more subtle and varied ways around practical concerns regarding volunteer work and a common search for compromise.

Conclusion

This special issue has only provided a glimse of the many avenues that are left to explore with the help of a lens for paradoxes. We hope that this special issue will stimulate further challenges to the dominating linear and rational management literature with in the field, to make room for understanding that tensions and ambiguities are not problem to be solved, but are conditions to manage, in which the right approach can fuel excitement, creativity and development. We encourage the research field of management of volunteers to sharpen its focus on tensions and ambiguities, and to develop a paradox lens, to explain paradoxes and to develop insights into how people navigate them.

Many scholars predict that paradox theory will become a new paradigm, that replaces perceptions of organizations as linear and rational. Instead of presenting tensions and ambiguity as things that can and should be avoided, paradox studies explore how organizations can focus on competing and contradictory demands, to enable learning and creativity, foster resilience, and unleash human potential (Smith & Lewis, Reference Smith and Lewis2011; Tsoukas & Cunha Reference Tsoukas and Cunha2017; Lewis & Smith, Reference Lewis and Smith2022). The indeterminacy can be fruitful, as Lewis says. We could call this a “win–win” situation: while we lose coherence and linearity in our theory (and they never were there, in organizations’ practice) we “win” a new set of questions, with a new approach to organizations.

Our effort at bringing together the field of paradox studies in general management studies to the research field of volunteer management and the concept of “the pentad” from dramaturgical studies, arrive at two insights, each of which comes with suggestions:

First, we suggest that paradoxes do not only exist external to management, but are often a result of management. To say that is not to oppose managerialism, but the articles within this issue will describe how management is a participant in the paradoxical situation, creating and responding to indeterminancy. The seeming harmonization or resolution of paradoxes simply creates more paradoxes.

From this comes our second suggestion: to Smith and Lewis’ focus on the fruitfulness of embracing paradox, we add that paradoxes are not in the way. They are the way. That is, they are not in the way of organizations’ missions; rather, in practice, paradoxes are the way that organizations have missions. The pentad helps us understand organizations in the holistic, processual, and interdependence perspectives that paradox studies suggests.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Royal Danish Library.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no moral conflicts that have to be addressed in relation to this paper.