1. Introduction

A singular modulus is the j-invariant of an elliptic curve with complex multiplication. The discriminant of a singular modulus is defined to be the discriminant of the imaginary quadratic order isomorphic to the endomorphism ring of the corresponding elliptic curve. In particular, the discriminant is a negative integer. There are only finitely many singular moduli of a given discriminant and these may be computed effectively [ Reference Cox10 , section 13].

Identify

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}$

with the modular curve Y(1) via the j-invariant. A point

${\mathbb{C}}$

with the modular curve Y(1) via the j-invariant. A point

![]() $(x_1, \ldots, x_n) \in {\mathbb{C}}^n$

such that

$(x_1, \ldots, x_n) \in {\mathbb{C}}^n$

such that

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are all singular moduli is called, in the terminology of Shimura varieties, a special point of

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are all singular moduli is called, in the terminology of Shimura varieties, a special point of

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

. A special point is a zero-dimensional special subvariety of

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

. A special point is a zero-dimensional special subvariety of

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

(see [

Reference Pila24

, definition 4·10] for the general definition of a special subvariety of

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

(see [

Reference Pila24

, definition 4·10] for the general definition of a special subvariety of

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

).

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

).

The André–Oort conjecture, which was proved for

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

by Pila [

Reference Pila22

], states that a subvariety

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

by Pila [

Reference Pila22

], states that a subvariety

![]() $V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

contains only finitely many maximal special subvarieties. In particular, a subvariety V contains only finitely many special points which do not lie on the union of all the positive-dimensional special subvarieties of V. Pila’s proof of André–Oort has a strong uniformity, as illustrated by the following theorem. This result is a direct consequence of Pila’s uniform André–Oort theorem [

Reference Pila22

, theorem 13·2] and a result of Binyamini [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4]. The result is ineffective, due to the ineffectivity of Pila’s proof of André–Oort (see [

Reference Pila22

, section 13]).

$V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

contains only finitely many maximal special subvarieties. In particular, a subvariety V contains only finitely many special points which do not lie on the union of all the positive-dimensional special subvarieties of V. Pila’s proof of André–Oort has a strong uniformity, as illustrated by the following theorem. This result is a direct consequence of Pila’s uniform André–Oort theorem [

Reference Pila22

, theorem 13·2] and a result of Binyamini [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4]. The result is ineffective, due to the ineffectivity of Pila’s proof of André–Oort (see [

Reference Pila22

, section 13]).

Theorem 1·1. Let

![]() $m, n, d \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exists an ineffective constant

$m, n, d \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exists an ineffective constant

![]() $c(m, n, d) \gt 0$

with the following property:

$c(m, n, d) \gt 0$

with the following property:

Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli and write

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli and write

![]() $\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

$\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

![]() $x_i$

. If

$x_i$

. If

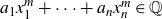

for some

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}}$

with

$b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}}$

with

then

Notably, the constant c(m, n, d) in Theorem 1·1 does not depend on the height of the coefficients

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n, b$

. In particular, given

$a_1, \ldots, a_n, b$

. In particular, given

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, there are only finitely many n-tuples

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, there are only finitely many n-tuples

![]() $(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

of pairwise distinct singular moduli

$(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

of pairwise distinct singular moduli

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

such that there exist

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

such that there exist

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

with

$b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

with

Theorem 1·1 is known effectively only when

![]() $n \leq 2$

. For

$n \leq 2$

. For

![]() $n = 1$

, this is a consequence of a result due to Goldfeld [

Reference Goldfeld14

] and Gross and Zagier [

Reference Gross and Zagier15

] (see Proposition 2·7). For

$n = 1$

, this is a consequence of a result due to Goldfeld [

Reference Goldfeld14

] and Gross and Zagier [

Reference Gross and Zagier15

] (see Proposition 2·7). For

![]() $n = 2$

, an effective version of Theorem 1·1 follows from a theorem of Kühne [

Reference Kühne17

, theorem 4] combined with the aforementioned result of Goldfeld–Gross–Zagier.

$n = 2$

, an effective version of Theorem 1·1 follows from a theorem of Kühne [

Reference Kühne17

, theorem 4] combined with the aforementioned result of Goldfeld–Gross–Zagier.

1·1. Main results

The first main result of this paper is the following effective partial version of Theorem 1·1 in the case that

![]() $d=1$

, i.e. for equations over

$d=1$

, i.e. for equations over

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}$

. Throughout this paper,

${\mathbb{Q}}$

. Throughout this paper,

![]() $K_*$

denotes a fixed imaginary quadratic field, the definition of which is given just before Proposition 2·2. Briefly,

$K_*$

denotes a fixed imaginary quadratic field, the definition of which is given just before Proposition 2·2. Briefly,

![]() $K_*$

is the single exceptional field arising from an application of Tatuzawa’s effective version [

Reference Tatuzawa29

] of Siegel’s lower bound [

Reference Siegel28

] for the class number of an imaginary quadratic field.

$K_*$

is the single exceptional field arising from an application of Tatuzawa’s effective version [

Reference Tatuzawa29

] of Siegel’s lower bound [

Reference Siegel28

] for the class number of an imaginary quadratic field.

Theorem 1·2. Let

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exists an effective constant c(m, n) with the following property:

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exists an effective constant c(m, n) with the following property:

Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli and write

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli and write

![]() $\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

$\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

![]() $x_i$

. If

$x_i$

. If

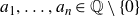

for some

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

and

$b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

and

then

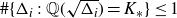

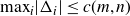

An effective bound, depending only on m, n, for all those discriminants

![]() $\Delta_i$

such that

$\Delta_i$

such that

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) \neq K_*$

is given by a result of Binyamini [

Reference Binyamini8

, theorem 1]. If there is at most one i such that

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) \neq K_*$

is given by a result of Binyamini [

Reference Binyamini8

, theorem 1]. If there is at most one i such that

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) = K_*$

, then

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) = K_*$

, then

![]() $\max \{ \lvert \Delta_1 \rvert, \ldots, \lvert \Delta_n \rvert\}$

is effectively bounded in terms of m, n by [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 1]. Our Theorem 1·2 improves on these prior results by allowing any number of the discriminants

$\max \{ \lvert \Delta_1 \rvert, \ldots, \lvert \Delta_n \rvert\}$

is effectively bounded in terms of m, n by [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 1]. Our Theorem 1·2 improves on these prior results by allowing any number of the discriminants

![]() $\Delta_1, \ldots, \Delta_n$

to be such that

$\Delta_1, \ldots, \Delta_n$

to be such that

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) = K_*$

, provided that all these exceptional

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) = K_*$

, provided that all these exceptional

![]() $\Delta_i$

are themselves equal to one another.

$\Delta_i$

are themselves equal to one another.

The second main result of this paper shows that, under a more restrictive condition on the discriminants involved, we can make the constant c(m, n) uniform in m and also write down this constant explicitly.

Theorem 1·3. Let

![]() $n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exist explicit constants

$n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exist explicit constants

![]() $c_1(n), c_2(n)$

with the following properties:

$c_1(n), c_2(n)$

with the following properties:

Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli such that

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli such that

for some

![]() $m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

and

$m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

and

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

. Write

$b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

. Write

![]() $\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

$\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

![]() $x_i$

.

$x_i$

.

-

(i) If

$k \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

is such that

$k \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

is such that

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_k}) \neq K_*$

and

then

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_k}) \neq K_*$

and

then \[ \quad \# \left \{ \Delta_i \;:\; i \in \left \{1, \ldots, n\right \} \mbox{ such that } {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_i}\right) = {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_k}\right) \right \} = 1,\]

\[ \quad \# \left \{ \Delta_i \;:\; i \in \left \{1, \ldots, n\right \} \mbox{ such that } {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_i}\right) = {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_k}\right) \right \} = 1,\]

$\lvert \Delta_k \rvert \leq c_1(n)$

.

$\lvert \Delta_k \rvert \leq c_1(n)$

.

-

(ii) If, for every

$k \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

,

then

$k \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

,

then \[ \quad \# \left \{ \Delta_i \;:\; i \in \left \{1, \ldots, n\right \} \mbox{ such that } {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_i}\right) = {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_k}\right) \right \} = 1,\]

\[ \quad \# \left \{ \Delta_i \;:\; i \in \left \{1, \ldots, n\right \} \mbox{ such that } {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_i}\right) = {\mathbb{Q}}\left(\sqrt{\Delta_k}\right) \right \} = 1,\]

$ \max \{ \lvert \Delta_i \rvert \;:\; i=1, \ldots, n\} \leq c_2(n)$

.

$ \max \{ \lvert \Delta_i \rvert \;:\; i=1, \ldots, n\} \leq c_2(n)$

.

An explicit form for the constant

![]() $c_1(n)$

is given in Proposition 6·2, while an explicit form for the constant

$c_1(n)$

is given in Proposition 6·2, while an explicit form for the constant

![]() $c_2(n)$

appears at the end of Section 6·2.

$c_2(n)$

appears at the end of Section 6·2.

As steps in the proofs of Theorems 1·2 and Theorem 1·3, we also prove the following two results, which may have some independent interest. The first of them is also used in the proof of Theorem 1·6.

Theorem 1·4. Let

![]() $n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

$n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli which are all of discriminant

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli which are all of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. Denote by

$\Delta$

. Denote by

![]() $h(\Delta)$

the class number of the imaginary quadratic order of discriminant

$h(\Delta)$

the class number of the imaginary quadratic order of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. Let

$\Delta$

. Let

![]() $K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. If

$K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. If

for some

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, then either

$m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, then either

or

![]() $h(\Delta) = n$

and

$h(\Delta) = n$

and

![]() $a_1 = \cdots = a_n$

.

$a_1 = \cdots = a_n$

.

The second is a result on the fields generated by linear combinations of powers of singular moduli of the same discriminant.

Theorem 1·5. Let

![]() $n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

$n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli which are all of discriminant

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli which are all of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. Let

$\Delta$

. Let

![]() $K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Then either

$K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Then either

or

for all

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

and every

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

and every

![]() $m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

.

$m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

.

We emphasise that Theorems 1·4 and 1·5 apply to all discriminants

![]() $\Delta$

, including those with

$\Delta$

, including those with

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta}) = K_*$

. Note also that Theorems 1·4 and 1·5 are uniform in the exponent m, as well as in

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta}) = K_*$

. Note also that Theorems 1·4 and 1·5 are uniform in the exponent m, as well as in

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n$

. For discussion of whether such uniformity in m may also hold in Theorem 1·1, see Section 3·1.

$a_1, \ldots, a_n$

. For discussion of whether such uniformity in m may also hold in Theorem 1·1, see Section 3·1.

The final main result of this paper is a completely explicit version of Theorem 1·1 for the case where

![]() $m= d=1$

and

$m= d=1$

and

![]() $n=3$

. The analogous result for

$n=3$

. The analogous result for

![]() $n=2$

is due to Allombert, Bilu and Pizarro–Madariaga [

Reference Allombert, Bilu and Pizarro-Madariaga1

, theorem 1·2].

$n=2$

is due to Allombert, Bilu and Pizarro–Madariaga [

Reference Allombert, Bilu and Pizarro-Madariaga1

, theorem 1·2].

Theorem 1·6. Let x, y, z be pairwise distinct singular moduli and

![]() $A, B, C \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

. Then

$A, B, C \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

. Then

if and only if (up to permuting x, y, z) one of the following holds:

-

(i)

$x, y, z \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

;

$x, y, z \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

;-

(ii) (a)

$x \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

,

$x \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

, -

(b)

${\mathbb{Q}}(y) = {\mathbb{Q}}(z)$

,

${\mathbb{Q}}(y) = {\mathbb{Q}}(z)$

, -

(c)

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

, and

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

, and -

(d)

$B/C = -(z-z')/(y-y')$

, where y′, z′ are the unique non-trivial Galois conjugates of y, z over

$B/C = -(z-z')/(y-y')$

, where y′, z′ are the unique non-trivial Galois conjugates of y, z over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

respectively;

${\mathbb{Q}}$

respectively;

-

(iii) (a)

${\mathbb{Q}}(x) = {\mathbb{Q}}(y) = {\mathbb{Q}}(z)$

,

${\mathbb{Q}}(x) = {\mathbb{Q}}(y) = {\mathbb{Q}}(z)$

, -

(b)

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(x) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

, and

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(x) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

, and -

(c) writing x′, y′, z′ for the unique non-trivial Galois conjugates over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

of x, y, z respectively, we have that

${\mathbb{Q}}$

of x, y, z respectively, we have that

\[A = -\frac{B(y-y')+C(z-z')}{x-x'};\]

\[A = -\frac{B(y-y')+C(z-z')}{x-x'};\]

-

(iv) (a)

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(x) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 3$

,

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(x) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 3$

, -

(b) x, y, z are all conjugate over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

, and

${\mathbb{Q}}$

, and -

(c)

$A= B = C$

;

$A= B = C$

;

-

(v) (a)

${\mathbb{Q}}(x) \subset {\mathbb{Q}}(y) = {\mathbb{Q}}(z)$

,

${\mathbb{Q}}(x) \subset {\mathbb{Q}}(y) = {\mathbb{Q}}(z)$

, -

(b)

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(x) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

and

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(x) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

and

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 4$

,

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(y) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = [{\mathbb{Q}}(z) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 4$

, -

(c) y, z are conjugate over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

, and

${\mathbb{Q}}$

, and -

(d) writing x′ for the unique non-trivial Galois conjugate of x over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

and v, w for the other two Galois conjugates of y, z over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

and v, w for the other two Galois conjugates of y, z over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

, we have that

${\mathbb{Q}}$

, we have that

\[\frac{A}{B} = \frac{A}{C} = - \frac{(y+z) - (v+w)}{x - x'}.\]

\[\frac{A}{B} = \frac{A}{C} = - \frac{(y+z) - (v+w)}{x - x'}.\]

-

Note that it is straightforward to compute the list of all the triples of singular moduli satisfying one of the conditions (i)–(v) in Theorem 1·6. The proof of Theorem 1·6 involves some computations in PARI [ 30 ]. These computations were carried out using a standard desktop computerFootnote 1 ; the scripts are available from: https://github.com/guyfowler/sums_of_powers.

1·2. Related results

Riffaut [

Reference Riffaut25

] and, jointly, Luca and Riffaut [

Reference Luca and Riffaut19

] proved an effective (indeed, completely explicit) version [

Reference Luca and Riffaut19

, theorem 1·3] of Theorem 1·1 in the case where

![]() $d = 1$

and

$d = 1$

and

![]() $n = 2$

. For

$n = 2$

. For

![]() $d=1$

and

$d=1$

and

![]() $n = 3$

, an explicit version of Theorem 1·1 in the special case that

$n = 3$

, an explicit version of Theorem 1·1 in the special case that

![]() $\lvert a_1 \rvert = \lvert a_2 \rvert = \lvert a_3 \rvert$

was proved by the author in a previous paper [

Reference Fowler13

, theorem 1·1].

$\lvert a_1 \rvert = \lvert a_2 \rvert = \lvert a_3 \rvert$

was proved by the author in a previous paper [

Reference Fowler13

, theorem 1·1].

Binyamini [

Reference Binyamini8

] proved a version of Theorem 1·1 which is effective, but not uniform in the height of the coefficients

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n, b$

. He proved [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4] that if

$a_1, \ldots, a_n, b$

. He proved [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4] that if

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

and

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

and

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct singular moduli of respective discriminants

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct singular moduli of respective discriminants

![]() $\Delta_1, \ldots, \Delta_n$

such that

$\Delta_1, \ldots, \Delta_n$

such that

then

where c(m, n, d, h) is an effective constant which depends only on m, n,

and also

Here

![]() $H(\!\cdot\!)$

denotes the absolute multiplicative Weil height, see e.g. [

Reference Bombieri and Gubler9

, section 1·5]. In the

$H(\!\cdot\!)$

denotes the absolute multiplicative Weil height, see e.g. [

Reference Bombieri and Gubler9

, section 1·5]. In the

![]() $m=1$

case, the same result was proved independently by Bilu and Kühne [

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, lemma 3·1], who even gave an explicit form [

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, (42)] for the constant c(1, n, d, h). The dependence of the constant c(m, n, d, h) on h means that [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4] and [

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, lemma 3·1] do not, for example, give an effective bound on the n-tuples

$m=1$

case, the same result was proved independently by Bilu and Kühne [

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, lemma 3·1], who even gave an explicit form [

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, (42)] for the constant c(1, n, d, h). The dependence of the constant c(m, n, d, h) on h means that [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4] and [

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, lemma 3·1] do not, for example, give an effective bound on the n-tuples

![]() $(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

of pairwise distinct singular moduli

$(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

of pairwise distinct singular moduli

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

which satisfy (1·1) with

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

which satisfy (1·1) with

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n, b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

.

$a_1, \ldots, a_n, b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

.

It is also worth noting that it is possible to obtain (ineffective) bounds on the number of maximal special subvarieties which are uniform across definable families of subvarieties and do not depend on (the degree of) the field of definition of the subvariety. Scanlon’s results on automatic uniformity [

Reference Scanlon27

, theorem 4·2] imply that, for every

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, there exists an ineffective constant

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, there exists an ineffective constant

![]() $c(m, n) \gt 0$

with the following property: if

$c(m, n) \gt 0$

with the following property: if

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{C}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{C}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{C}}$

, then there are at most c(m, n) distinct n-tuples

$b \in {\mathbb{C}}$

, then there are at most c(m, n) distinct n-tuples

![]() $(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

of pairwise distinct singular moduli

$(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

of pairwise distinct singular moduli

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

such that

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

such that

In the case where

![]() $m=1$

and

$m=1$

and

![]() $n=2$

, Bilu, Luca, and Masser [

Reference Bilu, Luca and Masser5

, theorem 1·1] proved that there are only (ineffectively) finitely many distinct, non-special linear subvarieties of

$n=2$

, Bilu, Luca, and Masser [

Reference Bilu, Luca and Masser5

, theorem 1·1] proved that there are only (ineffectively) finitely many distinct, non-special linear subvarieties of

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^2$

which contain at least 3 distinct special points.

${\mathbb{C}}^2$

which contain at least 3 distinct special points.

1·3. Structure of this paper

In Section 2, we recall some facts needed throughout the paper. In Section 3, we explain how Theorem 1·1 follows from the results of Pila [ Reference Pila22 ] and Binyamini [ Reference Binyamini8 ]. Theorems 1·4 and 1·5 are proved in Sections 4 and 5 respectively. The proofs of Theorems 1·2 and 1·3 are then carried out in Section 6. Section 7 contains some properties of singular moduli, which are then used for the proof of Theorem 1·6 in Section 8.

2. Preliminaries

2·1. Properties of singular moduli

We collect here some well-known properties of singular moduli which we will need throughout the paper.

Let

![]() $j \colon {\mathbb{H}} \to {\mathbb{C}}$

denote the modular j-function, where

$j \colon {\mathbb{H}} \to {\mathbb{C}}$

denote the modular j-function, where

![]() ${\mathbb{H}}$

is the complex upper half plane. A singular modulus is a complex number

${\mathbb{H}}$

is the complex upper half plane. A singular modulus is a complex number

![]() $j(\tau)$

, where

$j(\tau)$

, where

![]() $\tau \in {\mathbb{H}}$

is such that

$\tau \in {\mathbb{H}}$

is such that

![]() $[{\mathbb{Q}}(\tau) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

. The discriminant

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(\tau) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] = 2$

. The discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

of a singular modulus

$\Delta$

of a singular modulus

![]() $j(\tau)$

is given by

$j(\tau)$

is given by

![]() $\Delta = b^2-4ac$

, where

$\Delta = b^2-4ac$

, where

![]() $a, b, c \in {\mathbb{Z}}$

, not all zero, are such that

$a, b, c \in {\mathbb{Z}}$

, not all zero, are such that

![]() $a \tau^2 + b \tau + c = 0$

and

$a \tau^2 + b \tau + c = 0$

and

![]() $\gcd(a, b, c) = 1$

. In particular,

$\gcd(a, b, c) = 1$

. In particular,

![]() $\Delta \lt 0$

and

$\Delta \lt 0$

and

![]() $\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

. Hence,

$\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

. Hence,

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 3$

always.

$\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 3$

always.

Note that

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\tau) = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. The fundamental discriminant D of

${\mathbb{Q}}(\tau) = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. The fundamental discriminant D of

![]() $j(\tau)$

is defined to be the discriminant of the imaginary quadratic field

$j(\tau)$

is defined to be the discriminant of the imaginary quadratic field

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\tau) = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. One has that

${\mathbb{Q}}(\tau) = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. One has that

![]() $\Delta = f^2 D$

for some

$\Delta = f^2 D$

for some

![]() $f \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

.

$f \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

.

Write

![]() $F_j$

for the standard fundamental domain for the action (by fractional linear transformations) of

$F_j$

for the standard fundamental domain for the action (by fractional linear transformations) of

![]() ${\mathrm{SL}_2({\mathbb{Z}})}$

on

${\mathrm{SL}_2({\mathbb{Z}})}$

on

![]() ${\mathbb{H}}$

, i.e.

${\mathbb{H}}$

, i.e.

\begin{align*} {}F_j = &\left\{ z \in {\mathbb{H}} \;:\; -\frac{1}{2} \leq {\mathrm{Re}} z \lt \frac{1}{2} \mbox{ and } \lvert z \rvert \gt 1\right\}\\ {}&\cup \left\{ z \in {\mathbb{H}} \;:\; -\frac{1}{2} \leq {\mathrm{Re}} z \leq 0 \mbox{ and } \lvert z \rvert = 1\right\}.\end{align*}

\begin{align*} {}F_j = &\left\{ z \in {\mathbb{H}} \;:\; -\frac{1}{2} \leq {\mathrm{Re}} z \lt \frac{1}{2} \mbox{ and } \lvert z \rvert \gt 1\right\}\\ {}&\cup \left\{ z \in {\mathbb{H}} \;:\; -\frac{1}{2} \leq {\mathrm{Re}} z \leq 0 \mbox{ and } \lvert z \rvert = 1\right\}.\end{align*}

The j-function restricts to a bijection

![]() $F_j \to {\mathbb{C}}$

. Therefore, for

$F_j \to {\mathbb{C}}$

. Therefore, for

![]() $\Delta \lt 0$

such that

$\Delta \lt 0$

such that

![]() $\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

, the map

$\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

, the map

is a bijection between the set

and the set of singular moduli of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. For each such

$\Delta$

. For each such

![]() $\Delta$

, there exists a unique triple

$\Delta$

, there exists a unique triple

![]() $(a, b, c) \in T_\Delta$

with

$(a, b, c) \in T_\Delta$

with

![]() $a=1$

, given by

$a=1$

, given by

where

![]() $k \in \{0, 1\}$

is such that

$k \in \{0, 1\}$

is such that

![]() $k \equiv \Delta \bmod 2$

; we call the corresponding singular modulus the dominant singular modulus of discriminant

$k \equiv \Delta \bmod 2$

; we call the corresponding singular modulus the dominant singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

.

$\Delta$

.

If x is a singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

, then, see [

Reference Cox10

, lemma 9·3 and theorem 11·1], the field

$\Delta$

, then, see [

Reference Cox10

, lemma 9·3 and theorem 11·1], the field

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta}, x)$

is a Galois extension of both

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta}, x)$

is a Galois extension of both

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

and

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

and

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}$

and

${\mathbb{Q}}$

and

where

![]() ${\mathrm{cl}}(\Delta)$

denotes the class group of the unique imaginary quadratic order of discriminant

${\mathrm{cl}}(\Delta)$

denotes the class group of the unique imaginary quadratic order of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

.

$\Delta$

.

Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be all the distinct singular moduli of some discriminant

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be all the distinct singular moduli of some discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. Then, by [

Reference Cox10

, theorem 11·1 and proposition 13·2], the polynomial

$\Delta$

. Then, by [

Reference Cox10

, theorem 11·1 and proposition 13·2], the polynomial

has coefficients in

![]() ${\mathbb{Z}}$

and is irreducible over

${\mathbb{Z}}$

and is irreducible over

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}$

and over

${\mathbb{Q}}$

and over

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Hence, for every

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Hence, for every

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, we have that

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, we have that

where

![]() $h(\Delta)$

denotes the class number of the imaginary quadratic order of discriminant

$h(\Delta)$

denotes the class number of the imaginary quadratic order of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

.

$\Delta$

.

The class numbers of small discriminants may be computed straightforwardly in PARI. We will make use of the following consequence of this.

Lemma 2·1. Let x be a singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. If

$\Delta$

. If

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert \lt 15$

, then

$\lvert \Delta \rvert \lt 15$

, then

![]() $x \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

. If

$x \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

. If

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert \lt 39$

, then

$\lvert \Delta \rvert \lt 39$

, then

![]() $h(\Delta) \leq 3$

.

$h(\Delta) \leq 3$

.

We will also need the following bound on singular moduli.

Proposition 2·2. Let x be a singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

which corresponds to a triple

$\Delta$

which corresponds to a triple

![]() $(a, b, c) \in T_\Delta$

. Then

$(a, b, c) \in T_\Delta$

. Then

Proof. Let

![]() $(a, b, c) \in T_\Delta$

be the triple corresponding to x. Then

$(a, b, c) \in T_\Delta$

be the triple corresponding to x. Then

![]() $x = j(\tau)$

, where

$x = j(\tau)$

, where

The result follows immediately, since Bilu, Masser and Zannier [

Reference Bilu, Masser and Zannier7

, lemma 1] proved that if

![]() $z \in F_j$

, then

$z \in F_j$

, then

This bound has the following consequence.

Lemma 2·3. Let x, y be distinct singular moduli of the same discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. Suppose that x is dominant. Then

$\Delta$

. Suppose that x is dominant. Then

\[\lvert y \rvert \leq \frac{6 \lvert x \rvert}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}.\]

\[\lvert y \rvert \leq \frac{6 \lvert x \rvert}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}.\]

Proof. There are at least two distinct singular moduli of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

, so

$\Delta$

, so

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 15$

by Lemma 2·1. Since x is dominant, y is not dominant. Thus, Proposition 2·2 implies that

$\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 15$

by Lemma 2·1. Since x is dominant, y is not dominant. Thus, Proposition 2·2 implies that

\begin{align*} {} {}\frac{\lvert y \rvert}{\lvert x \rvert} &\leq \frac{1}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)} \frac{1 + 2079 \exp\left(\frac{-\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}{1 - 2079 \exp\left(- \pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}\right)}\\ {} {}&\leq \frac{1}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)} \frac{1 + 2079 \exp\left(\frac{-\pi \sqrt{15}}{2}\right)}{1 - 2079 \exp\left(- \pi \sqrt{15}\right)}\\ {} {}&\leq \frac{6}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}. {}\end{align*}

\begin{align*} {} {}\frac{\lvert y \rvert}{\lvert x \rvert} &\leq \frac{1}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)} \frac{1 + 2079 \exp\left(\frac{-\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}{1 - 2079 \exp\left(- \pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}\right)}\\ {} {}&\leq \frac{1}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)} \frac{1 + 2079 \exp\left(\frac{-\pi \sqrt{15}}{2}\right)}{1 - 2079 \exp\left(- \pi \sqrt{15}\right)}\\ {} {}&\leq \frac{6}{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}. {}\end{align*}

2·2. Effective bounds for the class number

A theorem of Tatuzawa [ Reference Tatuzawa29 , theorem 1] and Dirichlet’s class number formula together imply the following result. It shows that Siegel’s [ Reference Siegel28 ] ineffective lower bound for the class number of imaginary quadratic fields may be made effective, apart from at most one possible exceptional imaginary quadratic field.

Theorem 2·4 ([

Reference Tatuzawa29

, theorem 1]). Let

![]() $\epsilon \in (0, 1/2)$

. Let

$\epsilon \in (0, 1/2)$

. Let

![]() $K_1, K_2$

be imaginary quadratic fields with respective discriminants

$K_1, K_2$

be imaginary quadratic fields with respective discriminants

![]() $D_1, D_2$

. If

$D_1, D_2$

. If

then

![]() $K_1 = K_2$

.

$K_1 = K_2$

.

In other words, for a fixed

![]() $\epsilon \in (0, 1/2)$

, there is at most one imaginary quadratic field K for which the bound

$\epsilon \in (0, 1/2)$

, there is at most one imaginary quadratic field K for which the bound

is false, where D denotes the discriminant of K. It is possible (indeed, it would follow from GRH) that, for some

![]() $\epsilon \in (0, 1/2)$

, the bound (2·1) in fact holds for every imaginary quadratic field K. In such a case, the results of [

Reference Binyamini8

] would imply an effective version of Theorem 1·1.

$\epsilon \in (0, 1/2)$

, the bound (2·1) in fact holds for every imaginary quadratic field K. In such a case, the results of [

Reference Binyamini8

] would imply an effective version of Theorem 1·1.

Throughout this paper, we fix

![]() $\epsilon_* = 1/12$

and denote by

$\epsilon_* = 1/12$

and denote by

![]() $K_*$

the unique imaginary quadratic field for which the corresponding bound (2·1) is false. Denote by

$K_*$

the unique imaginary quadratic field for which the corresponding bound (2·1) is false. Denote by

![]() $D_*$

the discriminant of

$D_*$

the discriminant of

![]() $K_*$

. If no such field

$K_*$

. If no such field

![]() $K_*$

exists, then we adopt the notational convention that the inequalities

$K_*$

exists, then we adopt the notational convention that the inequalities

![]() $K \neq K_*$

and

$K \neq K_*$

and

![]() $D \neq D_*$

hold for every imaginary quadratic field K with discriminant D. We have the following consequence of Tatuzawa’s result.

$D \neq D_*$

hold for every imaginary quadratic field K with discriminant D. We have the following consequence of Tatuzawa’s result.

Proposition 2·5 ([

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, (17)]). Let

![]() $\Delta \lt 0$

be such that

$\Delta \lt 0$

be such that

![]() $\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

and let

$\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

and let

![]() $K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. If

$K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. If

![]() $K \neq K_*$

, then

$K \neq K_*$

, then

For discriminants

![]() $\Delta$

with

$\Delta$

with

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta}) = K_*$

, the known effective bounds for the class number are much weaker.

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta}) = K_*$

, the known effective bounds for the class number are much weaker.

Proposition 2·6. Let

![]() $D \lt 0$

be a fundamental discriminant. Then

$D \lt 0$

be a fundamental discriminant. Then

Proof. Oesterlé [ Reference Oesterlé20 , théorème 1 and section 5·1], building on work of Goldfeld [ Reference Goldfeld14 ] and Gross–Zagier [ Reference Gross and Zagier15 , theorem 8·1], proved that

where

and this product is taken over all the primes p which divide D except the largest. Let

![]() $\omega(D)$

denote the number of distinct prime divisors of D. So there are

$\omega(D)$

denote the number of distinct prime divisors of D. So there are

![]() $\omega(D) - 1$

terms in the product defining F(D). By the theory of genera, see e.g. [

Reference Cox10

, proposition 3·11 and theorem 6·1], we have that

$\omega(D) - 1$

terms in the product defining F(D). By the theory of genera, see e.g. [

Reference Cox10

, proposition 3·11 and theorem 6·1], we have that

In particular,

![]() $2^{\omega(D) -1} \mid h(D)$

. So

$2^{\omega(D) -1} \mid h(D)$

. So

![]() $\omega(D) - 1 \leq v_2(h(D))$

, where

$\omega(D) - 1 \leq v_2(h(D))$

, where

![]() $ v_2(h(D))$

denotes the largest integer k such that

$ v_2(h(D))$

denotes the largest integer k such that

![]() $2^k \mid h(D)$

. Hence, there are at most

$2^k \mid h(D)$

. Hence, there are at most

![]() $v_2(h(D))$

terms appearing in the product defining F(D).

$v_2(h(D))$

terms appearing in the product defining F(D).

Observe that

if

![]() $p \geq 11$

. Hence,

$p \geq 11$

. Hence,

Since

![]() $h(D) \geq 2^{v_2(h(D))}$

by definition, we obtain that

$h(D) \geq 2^{v_2(h(D))}$

by definition, we obtain that

Proposition 2·7. Let

![]() $\Delta \lt 0$

be such that

$\Delta \lt 0$

be such that

![]() $\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

and let

$\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

and let

![]() $k \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt 0}$

. If

$k \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt 0}$

. If

![]() $h(\Delta) \leq k$

, then

$h(\Delta) \leq k$

, then

Proof. Write

![]() $\Delta = f^2 D$

, where D is the discriminant of

$\Delta = f^2 D$

, where D is the discriminant of

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Suppose that

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Suppose that

![]() $h(\Delta) \leq k$

. Assume first that

$h(\Delta) \leq k$

. Assume first that

![]() $D \notin \{-3, -4\}$

. The class number formula in [

Reference Cox10

, theorem 7·24] gives that

$D \notin \{-3, -4\}$

. The class number formula in [

Reference Cox10

, theorem 7·24] gives that

\[ h(\Delta) = h(D) f \prod_{p \mid f} \left(1 - \left(\frac{D}{p}\right)\frac{1}{p}\right),\]

\[ h(\Delta) = h(D) f \prod_{p \mid f} \left(1 - \left(\frac{D}{p}\right)\frac{1}{p}\right),\]

where

![]() $(D/p)$

denotes the Kronecker symbol. Hence,

$(D/p)$

denotes the Kronecker symbol. Hence,

![]() $h(D) \mid h(\Delta)$

and

$h(D) \mid h(\Delta)$

and

where

![]() $\varphi(\!\cdot\!)$

denotes Euler’s totient function. Hence,

$\varphi(\!\cdot\!)$

denotes Euler’s totient function. Hence,

Proposition 2·6 then implies that

while the classical bound

![]() $\varphi(\,f) \geq \sqrt{f/2}$

implies that

$\varphi(\,f) \geq \sqrt{f/2}$

implies that

![]() $f \leq 2k^2$

. Hence,

$f \leq 2k^2$

. Hence,

Now assume

![]() $D \in \{-3, -4\}$

. Then

$D \in \{-3, -4\}$

. Then

![]() $h(D) = 1$

. In this case, the class number formula from [

Reference Cox10

, theorem 7·24] implies that

$h(D) = 1$

. In this case, the class number formula from [

Reference Cox10

, theorem 7·24] implies that

Hence,

![]() $\varphi(\,f) \leq 3 k$

and so

$\varphi(\,f) \leq 3 k$

and so

![]() $f \leq 18 k^2$

. Thus, clearly,

$f \leq 18 k^2$

. Thus, clearly,

Finally, we will also need an upper bound for the class number. This bound is a straightforward consequence of Dirichlet’s class number formula.

Proposition 2·8. If

![]() $\Delta \lt 0$

is such that

$\Delta \lt 0$

is such that

![]() $\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

, then

$\Delta \equiv 0, 1 \bmod 4$

, then

![]() $h(\Delta) \leq \lvert \Delta \rvert^{2/3}$

.

$h(\Delta) \leq \lvert \Delta \rvert^{2/3}$

.

Proof. By [ Reference Paulin21 , proposition 2·2], we have that

It then suffices to note that, for every

![]() $x\gt0$

,

$x\gt0$

,

3. Deducing Theorem 1·1

In this section, we explain how Theorem 1·1 may be deduced from the results of Pila [

Reference Pila22

, theorem 13·2] and Binyamini [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4]. A direct proof of the

![]() $m = 1$

case of Theorem 1·1 was given by Pila [

Reference Pila23

, theorem 7·7].

$m = 1$

case of Theorem 1·1 was given by Pila [

Reference Pila23

, theorem 7·7].

For the definition of a special subvariety of

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

, see e.g. [

Reference Pila22

, definition 1·3], [

Reference Binyamini8

, (1·1)], or [

Reference Pila24

, definition 4·10]. For a subvariety

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

, see e.g. [

Reference Pila22

, definition 1·3], [

Reference Binyamini8

, (1·1)], or [

Reference Pila24

, definition 4·10]. For a subvariety

![]() $V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

, denote by

$V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

, denote by

![]() $V^\mathrm{sp}$

the union of all the positive-dimensional special subvarieties of V.

$V^\mathrm{sp}$

the union of all the positive-dimensional special subvarieties of V.

Let

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. For

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. For

![]() $a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in {\mathbb{C}}^n$

and

$a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in {\mathbb{C}}^n$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{C}}$

, let

$b \in {\mathbb{C}}$

, let

Lemma 3·1. Let

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli. Suppose that

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli. Suppose that

![]() $a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in ({\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

$a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in ({\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

![]() $b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}}$

are such that

$b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}}$

are such that

Then

Proof. Clearly,

Suppose that

for some positive-dimensional special subvariety S of

![]() $V_{a, b}$

. We show that this is impossible.

$V_{a, b}$

. We show that this is impossible.

The subvariety

![]() $V_{a, b}$

is, in the terminology of [

Reference Binyamini8

, definition 2], a hereditarily degree non-degenerate (hdnd) hypersurface. Hence, by [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4], the special subvariety S may be defined by equations solely of the form

$V_{a, b}$

is, in the terminology of [

Reference Binyamini8

, definition 2], a hereditarily degree non-degenerate (hdnd) hypersurface. Hence, by [

Reference Binyamini8

, corollary 4], the special subvariety S may be defined by equations solely of the form

![]() $z_i = z_k$

and

$z_i = z_k$

and

![]() $z_l = x_l$

. Since

$z_l = x_l$

. Since

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct, no non-trivial equations

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct, no non-trivial equations

![]() $z_i = z_k$

hold on S. Thus, up to reordering the coordinates,

$z_i = z_k$

hold on S. Thus, up to reordering the coordinates,

for some

![]() $k \in \{1, \ldots, n-1\}$

and

$k \in \{1, \ldots, n-1\}$

and

![]() $I \subset \{1, \ldots, n\}$

with

$I \subset \{1, \ldots, n\}$

with

![]() $\lvert I \rvert = k$

. So

$\lvert I \rvert = k$

. So

for all

![]() $z_i \in {\mathbb{C}}$

, which is clearly absurd since the

$z_i \in {\mathbb{C}}$

, which is clearly absurd since the

![]() $a_i$

are non-zero.

$a_i$

are non-zero.

Proof of Theorem

1·1. Let

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Define

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Define

![]() $V_{a, b} \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

as above. Let

$V_{a, b} \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

as above. Let

View

![]() $\mathbb{V}$

as a definable family of subvarieties of

$\mathbb{V}$

as a definable family of subvarieties of

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

with fibres

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

with fibres

![]() $V_{a, b}$

. Note that the definition of

$V_{a, b}$

. Note that the definition of

![]() $\mathbb{V}$

depends only on m, n.

$\mathbb{V}$

depends only on m, n.

By Pila’s Uniform André–Oort for

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

[

Reference Pila22

, theorem 13·2] applied to

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

[

Reference Pila22

, theorem 13·2] applied to

![]() $\mathbb{V}$

, for every

$\mathbb{V}$

, for every

![]() $d \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, there exists an ineffective constant

$d \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, there exists an ineffective constant

![]() $c(m, n, d)\gt0$

with the following property. Let

$c(m, n, d)\gt0$

with the following property. Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be singular moduli and write

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be singular moduli and write

![]() $\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

$\Delta_i$

for the discriminant of

![]() $x_i$

. Let

$x_i$

. Let

![]() $a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in ({\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

$a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in ({\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

![]() $b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. If

$b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. If

and

then

3·1. Uniformity in Theorem 1·1

Recall, from Section 2·1, that the singular moduli of a given discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

form a complete set of Galois conjugates over

$\Delta$

form a complete set of Galois conjugates over

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}$

. Moreover, by Proposition 2·7, the number of distinct singular moduli of discriminant

${\mathbb{Q}}$

. Moreover, by Proposition 2·7, the number of distinct singular moduli of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

is

$\Delta$

is

![]() $\geq c_1 (\log \lvert \Delta \rvert)^{c_2}$

for some absolute effective constants

$\geq c_1 (\log \lvert \Delta \rvert)^{c_2}$

for some absolute effective constants

![]() $c_1, c_2\gt0$

. Therefore, if m, n are fixed, then

$c_1, c_2\gt0$

. Therefore, if m, n are fixed, then

![]() $c(m, n, d) \to \infty$

as

$c(m, n, d) \to \infty$

as

![]() $d \to \infty$

, where c(m, n, d) is the constant in Theorem 1·1. Similarly, if m, d are fixed, then

$d \to \infty$

, where c(m, n, d) is the constant in Theorem 1·1. Similarly, if m, d are fixed, then

![]() $c(m, n, d) \to \infty$

as

$c(m, n, d) \to \infty$

as

![]() $n \to \infty$

.

$n \to \infty$

.

On the other hand, if n, d are fixed, then it is not obvious what happens to the constant c(m, n, d) as

![]() $m \to \infty$

. Since singular moduli are algebraic, one cannot bound the discriminants associated to a special point lying on a general hypersurface in

$m \to \infty$

. Since singular moduli are algebraic, one cannot bound the discriminants associated to a special point lying on a general hypersurface in

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

solely in terms of n and the minimal degree of a field of definition of the hypersurface. However, it may be possible to obtain bounds that are uniform in m for the specific family of hypersurfaces considered in Theorem 1·1, i.e. those defined by equations of the form

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

solely in terms of n and the minimal degree of a field of definition of the hypersurface. However, it may be possible to obtain bounds that are uniform in m for the specific family of hypersurfaces considered in Theorem 1·1, i.e. those defined by equations of the form

Indeed, the constant c(m, n, d) in Theorem 1·1 may be taken to be uniform in m if either

![]() $n = 1$

or

$n = 1$

or

![]() $(d, n) = (1, 2)$

. If x is a singular modulus of discriminant

$(d, n) = (1, 2)$

. If x is a singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

such that

$\Delta$

such that

for some

![]() $a, b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a, b \in {\overline{\mathbb{Q}}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, then

$m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, then

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert$

may be bounded solely in terms of

$\lvert \Delta \rvert$

may be bounded solely in terms of

![]() $[{\mathbb{Q}}(a, b) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]$

, thanks to Proposition 2·7 and the fact [

Reference Riffaut25

, lemma 2·6] that

$[{\mathbb{Q}}(a, b) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]$

, thanks to Proposition 2·7 and the fact [

Reference Riffaut25

, lemma 2·6] that

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(x^m) = {\mathbb{Q}}(x)$

. If

${\mathbb{Q}}(x^m) = {\mathbb{Q}}(x)$

. If

![]() $x_1, x_2$

are distinct singular moduli of respective discriminants

$x_1, x_2$

are distinct singular moduli of respective discriminants

![]() $\Delta_1, \Delta_2$

such that

$\Delta_1, \Delta_2$

such that

for some

![]() $a_1, a_2 \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, a_2 \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $m_1, m_2 \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, then

$m_1, m_2 \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, then

![]() $\max \{\lvert \Delta_1 \rvert, \lvert \Delta_2 \rvert \} \leq 427$

by [

Reference Luca and Riffaut19

, theorem 1·3] (see also [

Reference Riffaut25

, theorem 1·5]). For

$\max \{\lvert \Delta_1 \rvert, \lvert \Delta_2 \rvert \} \leq 427$

by [

Reference Luca and Riffaut19

, theorem 1·3] (see also [

Reference Riffaut25

, theorem 1·5]). For

![]() $n = 3$

, we have the previous result of the author [

Reference Fowler13

, theorem 1·1]: if

$n = 3$

, we have the previous result of the author [

Reference Fowler13

, theorem 1·1]: if

![]() $x_1, x_2, x_3$

are pairwise distinct singular moduli of respective discriminants

$x_1, x_2, x_3$

are pairwise distinct singular moduli of respective discriminants

![]() $\Delta_1, \Delta_2, \Delta_3$

such that

$\Delta_1, \Delta_2, \Delta_3$

such that

for some

![]() $m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

and

$m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

and

![]() $a_1, a_2, a_3 \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

with

$a_1, a_2, a_3 \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

with

![]() $\lvert a_1 \rvert = \lvert a_2 \rvert = \lvert a_3 \rvert$

, then

$\lvert a_1 \rvert = \lvert a_2 \rvert = \lvert a_3 \rvert$

, then

![]() $\max \{\lvert \Delta_1 \rvert, \lvert \Delta_2 \rvert, \lvert \Delta_3 \rvert \} \leq 907$

.

$\max \{\lvert \Delta_1 \rvert, \lvert \Delta_2 \rvert, \lvert \Delta_3 \rvert \} \leq 907$

.

4. Equations in singular moduli of the same discriminant

In this section, we prove Theorem 1·4.

Proof of Theorem

1·4. Let

![]() $n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

$n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli of discriminant

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. In particular,

$\Delta$

. In particular,

![]() $h(\Delta) \geq n$

. Write

$h(\Delta) \geq n$

. Write

![]() $K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Suppose that

$K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Suppose that

for some

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

,

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

,

![]() $b \in K$

, and

$b \in K$

, and

![]() $m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

.

$m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

.

Suppose first that

![]() $h(\Delta) \geq n+1$

. The singular moduli of discriminant

$h(\Delta) \geq n+1$

. The singular moduli of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

form a complete set of Galois conjugates over K. Hence, there must exist K-conjugates

$\Delta$

form a complete set of Galois conjugates over K. Hence, there must exist K-conjugates

of

![]() $(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

, where

$(x_1, \ldots, x_n)$

, where

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n+1\}$

, with the property that:

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n+1\}$

, with the property that:

Note that

for every

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n+1\}$

. Therefore,

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n+1\}$

. Therefore,

\begin{align*} {}\begin{vmatrix} {} {}1 & \cdots & 1\\ {} {}x_{1, 1}^m & \cdots & x_{1, n+1}^m\\ {} {}\vdots & & \vdots\\ {} {}x_{n, 1}^m & \cdots & x_{n, n+1}^m {}\end{vmatrix} {}=0.\end{align*}

\begin{align*} {}\begin{vmatrix} {} {}1 & \cdots & 1\\ {} {}x_{1, 1}^m & \cdots & x_{1, n+1}^m\\ {} {}\vdots & & \vdots\\ {} {}x_{n, 1}^m & \cdots & x_{n, n+1}^m {}\end{vmatrix} {}=0.\end{align*}

Expanding this determinant, we have that

Let

![]() $\tau$

be the unique element of

$\tau$

be the unique element of

![]() $S_{n+1}$

such that

$S_{n+1}$

such that

![]() $\tau(i+1) = i$

for every

$\tau(i+1) = i$

for every

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

. Then

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

. Then

\begin{align} {}\lvert x_{1, 1} \cdots x_{n, n} \rvert^m = \left \lvert \sum_{\sigma \in S_{n+1} \setminus \{ \tau\}} \mathrm{sgn}(\sigma) (x_{1, \sigma(2)} \cdots x_{n, \sigma(n+1)})^m \right\rvert.\end{align}

\begin{align} {}\lvert x_{1, 1} \cdots x_{n, n} \rvert^m = \left \lvert \sum_{\sigma \in S_{n+1} \setminus \{ \tau\}} \mathrm{sgn}(\sigma) (x_{1, \sigma(2)} \cdots x_{n, \sigma(n+1)})^m \right\rvert.\end{align}

Note that

since

![]() $x_{i, i}$

is the unique dominant singular modulus of discriminant

$x_{i, i}$

is the unique dominant singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

for every

$\Delta$

for every

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

. Observe also that if

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

. Observe also that if

![]() $\sigma \in S_{n+1} \setminus \{ \tau\}$

, then

$\sigma \in S_{n+1} \setminus \{ \tau\}$

, then

![]() $\sigma(i+1) \neq i$

for some

$\sigma(i+1) \neq i$

for some

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

and hence at least one of

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

and hence at least one of

is not dominant. Therefore, by Lemma 2·3,

\begin{align} {}&\left\lvert {}\sum_{\sigma \in S_{n+1} \setminus \{ \tau\}} \mathrm{sgn}(\sigma) (x_{1, \sigma(2)} \cdots x_{n, \sigma(n+1)})^m \right\rvert \nonumber\\ {}&\quad \leq (n+1)! \left(\frac{6 }{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right) } \right)^m\lvert x_{1, 1} \rvert^{mn}.\end{align}

\begin{align} {}&\left\lvert {}\sum_{\sigma \in S_{n+1} \setminus \{ \tau\}} \mathrm{sgn}(\sigma) (x_{1, \sigma(2)} \cdots x_{n, \sigma(n+1)})^m \right\rvert \nonumber\\ {}&\quad \leq (n+1)! \left(\frac{6 }{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right) } \right)^m\lvert x_{1, 1} \rvert^{mn}.\end{align}

Then (4·1) and (4·2) together imply that

\[\left(\frac{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}{6}\right)^m \leq (n+1)!\]

\[\left(\frac{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}{6}\right)^m \leq (n+1)!\]

Since

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 3$

for every discriminant

$\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 3$

for every discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

, we have that

$\Delta$

, we have that

\[ \exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right) \geq \exp\left(\frac{\pi \sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = 15.190\ldots \gt 6.\]

\[ \exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right) \geq \exp\left(\frac{\pi \sqrt{3}}{2}\right) = 15.190\ldots \gt 6.\]

Thus,

\[\frac{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}{6} \leq (n+1)!\]

\[\frac{\exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}{6} \leq (n+1)!\]

For every

![]() $k \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, Stirling’s formula [

Reference Robbins26

, (1), (2)] implies that

$k \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

, Stirling’s formula [

Reference Robbins26

, (1), (2)] implies that

Hence,

\begin{align*} {}\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} &\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left((2n+3) \log(n+1) -2(n+1) +\log(72 \pi) + \frac{1}{6}\right)\\ {}&\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left(\left(2n+3\right) \log\left(n+1\right) -2n +4\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*} {}\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} &\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left((2n+3) \log(n+1) -2(n+1) +\log(72 \pi) + \frac{1}{6}\right)\\ {}&\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left(\left(2n+3\right) \log\left(n+1\right) -2n +4\right).\end{align*}

Now suppose that

![]() $h(\Delta) = n$

. So

$h(\Delta) = n$

. So

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are a complete set of Galois conjugates over K. Newton’s identities thus imply that

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are a complete set of Galois conjugates over K. Newton’s identities thus imply that

Hence,

If

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n$

are not all equal, then

$a_1, \ldots, a_n$

are not all equal, then

![]() $a_i \neq a_1$

for some

$a_i \neq a_1$

for some

![]() $i \in \{2, \ldots, n\}$

. Let

$i \in \{2, \ldots, n\}$

. Let

Since

![]() $l \lt n$

, we have that

$l \lt n$

, we have that

![]() $h(\Delta) \geq l+1$

. We may then apply, for l singular moduli, the already proved case of the theorem to obtain that

$h(\Delta) \geq l+1$

. We may then apply, for l singular moduli, the already proved case of the theorem to obtain that

\begin{align*} {}\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} &\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left((2l+3) \log(l+1) -2l +4\right)\\ {}&\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left((2n+3) \log(n+1) -2n +4\right).\end{align*}

\begin{align*} {}\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} &\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left((2l+3) \log(l+1) -2l +4\right)\\ {}&\leq \frac{1}{\pi} \left((2n+3) \log(n+1) -2n +4\right).\end{align*}

Remark 4·1. In the proof of Theorem 1·4, it is crucial that every singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

is conjugate over K to the dominant singular modulus of discriminant

$\Delta$

is conjugate over K to the dominant singular modulus of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. Thus, the above proof does not extend to equations over an arbitrary number field L. In contrast, the deduction, in the next two sections, of Theorem 1·5 and then Theorem 1·2 from Theorem 1·4 would go through over a general number field L.

$\Delta$

. Thus, the above proof does not extend to equations over an arbitrary number field L. In contrast, the deduction, in the next two sections, of Theorem 1·5 and then Theorem 1·2 from Theorem 1·4 would go through over a general number field L.

5. Fields generated by singular moduli

Theorem 1·5 may be deduced from Theorem 1·4, as we now show.

Proof of Theorem

1·5. Let

![]() $n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

$n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli of the same discriminant

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

be pairwise distinct singular moduli of the same discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

. Let

$\Delta$

. Let

![]() $K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Suppose that

$K = {\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta})$

. Suppose that

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in K \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

are such that

$m \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

are such that

We will show that the desired bound holds on

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert$

.

$\lvert \Delta \rvert$

.

Recall that

![]() $K(x_1) / K$

is a Galois extension. In particular,

$K(x_1) / K$

is a Galois extension. In particular,

since

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are all conjugate over K. Let

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are all conjugate over K. Let

![]() $G = {\mathrm{Gal}}(K(x_1) / K)$

and let

$G = {\mathrm{Gal}}(K(x_1) / K)$

and let

So

by assumption. In particular, there exists some

![]() $\sigma \in H$

such that

$\sigma \in H$

such that

Since

![]() $\sigma$

fixes

$\sigma$

fixes

![]() $K(a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_n x_n^m)$

, we have that

$K(a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_n x_n^m)$

, we have that

The

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct and the

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct and the

![]() $\sigma(x_1), \ldots, \sigma(x_n)$

are pairwise distinct too. Cancelling terms as necessary, there must exist some

$\sigma(x_1), \ldots, \sigma(x_n)$

are pairwise distinct too. Cancelling terms as necessary, there must exist some

![]() $k \in \{2, \ldots, 2n\}$

and pairwise distinct singular moduli

$k \in \{2, \ldots, 2n\}$

and pairwise distinct singular moduli

![]() $y_1, \ldots, y_k$

of discriminant

$y_1, \ldots, y_k$

of discriminant

![]() $\Delta$

such that

$\Delta$

such that

for some

![]() $b_1, \ldots, b_k \in K \setminus \{0\}$

. Here we used that

$b_1, \ldots, b_k \in K \setminus \{0\}$

. Here we used that

![]() $\sigma(x_1) \notin \{x_1, \ldots, x_n\}$

. Hence, by Theorem 1·4, either:

$\sigma(x_1) \notin \{x_1, \ldots, x_n\}$

. Hence, by Theorem 1·4, either:

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} \leq c_1(k)$

and so certainly

$\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} \leq c_1(k)$

and so certainly

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} \leq c_1(2n)$

as desired (where

$\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} \leq c_1(2n)$

as desired (where

![]() $c_1(\!\cdot\!)$

denotes the constant from Theorem 1·4), or:

$c_1(\!\cdot\!)$

denotes the constant from Theorem 1·4), or:

![]() $h(\Delta) = k$

and

$h(\Delta) = k$

and

![]() $b_1 = \cdots = b_k$

.

$b_1 = \cdots = b_k$

.

Suppose then that

![]() $h(\Delta) = k$

and

$h(\Delta) = k$

and

![]() $b_1 = \cdots = b_k$

. Re-indexing the

$b_1 = \cdots = b_k$

. Re-indexing the

![]() $y_i$

as necessary, we may assume that

$y_i$

as necessary, we may assume that

![]() $y_1$

is dominant. Note also that

$y_1$

is dominant. Note also that

![]() $y_1 \neq 0$

and

$y_1 \neq 0$

and

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 15$

, by Lemma 2·1 since

$\lvert \Delta \rvert \geq 15$

, by Lemma 2·1 since

![]() $k \geq 2$

. Then, by Lemma 2·3 and Proposition 2·8,

$k \geq 2$

. Then, by Lemma 2·3 and Proposition 2·8,

\begin{align*} {}&\lvert b_1 y_1^m + \cdots + b_k y_k^m \rvert\\ & \quad \geq \left\lvert b_1 \right\rvert \left( \left\lvert y_1 \right\rvert^m - \left( \left\lvert y_2 \right\rvert^m + \cdots + \left\rvert y_k \right\rvert^m \right) \right) \\ & \quad {}\geq \left\lvert b_1 \right \rvert \left \lvert y_1 \right\rvert^m \left(1- \frac{\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} (2 + \log \lvert \Delta \rvert)}{\pi}\left(\frac{6}{ \exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}\right)^m\right)\\ {} & \quad \geq \left\lvert b_1 \right \rvert \left \lvert y_1 \right\rvert^m \left(1- \frac{6 \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} (2 + \log \lvert \Delta \rvert) }{ \pi \exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}\right)\\ {} & \quad \gt0,\end{align*}

\begin{align*} {}&\lvert b_1 y_1^m + \cdots + b_k y_k^m \rvert\\ & \quad \geq \left\lvert b_1 \right\rvert \left( \left\lvert y_1 \right\rvert^m - \left( \left\lvert y_2 \right\rvert^m + \cdots + \left\rvert y_k \right\rvert^m \right) \right) \\ & \quad {}\geq \left\lvert b_1 \right \rvert \left \lvert y_1 \right\rvert^m \left(1- \frac{\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} (2 + \log \lvert \Delta \rvert)}{\pi}\left(\frac{6}{ \exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}\right)^m\right)\\ {} & \quad \geq \left\lvert b_1 \right \rvert \left \lvert y_1 \right\rvert^m \left(1- \frac{6 \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} (2 + \log \lvert \Delta \rvert) }{ \pi \exp\left(\frac{\pi \lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2}}{2}\right)}\right)\\ {} & \quad \gt0,\end{align*}

which is a contradiction. So we must have that

![]() $\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} \leq c_1(2n)$

.

$\lvert \Delta \rvert^{1/2} \leq c_1(2n)$

.

6. The proof of Theorems 1·2 and 1·3

6·1. Completing the proof of Theorem 1·2

In this section, we complete the proof of Theorem 1·2. We start by recalling Binyamini’s [

Reference Binyamini8

] “almost” effective André–Oort result for

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

. For the definition of a special subvariety of

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

. For the definition of a special subvariety of

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n$

, see e.g. [

Reference Binyamini8

, (1·1)] or [

Reference Pila24

, definition 4·10]. For a subvariety

${\mathbb{C}}^n$

, see e.g. [

Reference Binyamini8

, (1·1)] or [

Reference Pila24

, definition 4·10]. For a subvariety

![]() $V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

, we denote by

$V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

, we denote by

![]() $\deg V$

the degree of V with respect to the projective embedding

$\deg V$

the degree of V with respect to the projective embedding

![]() ${\mathbb{C}}^n \subset \mathbb{P}^n$

. Binyamini proved the following theoremFootnote

2

. (Recall that

${\mathbb{C}}^n \subset \mathbb{P}^n$

. Binyamini proved the following theoremFootnote

2

. (Recall that

![]() $K_*$

denotes the exceptional imaginary quadratic field that was defined above Proposition 2·5.)

$K_*$

denotes the exceptional imaginary quadratic field that was defined above Proposition 2·5.)

Theorem 6·1 ([

Reference Binyamini8

, theorem 1]). Let

![]() $n, d, l \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exists an effective constant

$n, d, l \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. There exists an effective constant

![]() $c(n, d, l)\gt0$

with the following property:

$c(n, d, l)\gt0$

with the following property:

Let

![]() $V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

be a subvariety defined over some number field L with

$V \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

be a subvariety defined over some number field L with

![]() $[L \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] \leq d$

and

$[L \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}] \leq d$

and

![]() $\deg V \leq l$

. Denote by

$\deg V \leq l$

. Denote by

![]() $V^\mathrm{sp}$

the union of all the positive-dimensional special subvarieties of V. If

$V^\mathrm{sp}$

the union of all the positive-dimensional special subvarieties of V. If

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are singular moduli with respective discriminants

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are singular moduli with respective discriminants

![]() $\Delta_1, \ldots, \Delta_n$

such that

$\Delta_1, \ldots, \Delta_n$

such that

then, for every

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, either

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, either

or

Let

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. For

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. For

![]() $a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in ({\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

$a = (a_1, \ldots, a_n) \in ({\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

, let

$b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

, let

Since the

![]() $V_{a, b}$

are all defined over

$V_{a, b}$

are all defined over

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}$

and have degree m, the constant in Theorem 6·1 is uniform (for the given m, n) across the

${\mathbb{Q}}$

and have degree m, the constant in Theorem 6·1 is uniform (for the given m, n) across the

![]() $V_{a, b}$

.

$V_{a, b}$

.

Proof of Theorem

1·2. Let

![]() $m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

$m, n \in {\mathbb{Z}}_{\gt0}$

. Let

![]() $c_1(m, n)\gt0$

be the effective constant given by Theorem 6·1 applied to the family of linear subvarieties

$c_1(m, n)\gt0$

be the effective constant given by Theorem 6·1 applied to the family of linear subvarieties

![]() $V_{a, b} \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

, where

$V_{a, b} \subset {\mathbb{C}}^n$

, where

![]() $a \in ({\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

$a \in ({\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\})^n$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

(i.e.

$b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

(i.e.

![]() $c_1(m, n) = c(n, 1, m)$

for the constant c(n, d, l) in the statement of Theorem 6·1).

$c_1(m, n) = c(n, 1, m)$

for the constant c(n, d, l) in the statement of Theorem 6·1).

Suppose that

![]() $x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct singular moduli such that

$x_1, \ldots, x_n$

are pairwise distinct singular moduli such that

for some

![]() $a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

$a_1, \ldots, a_n \in {\mathbb{Q}} \setminus \{0\}$

and

![]() $b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

. Then, by Lemma 3·1,

$b \in {\mathbb{Q}}$

. Then, by Lemma 3·1,

Hence, by Theorem 6·1, for every

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, either

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, either

or

If there is no i such that

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) = K_*$

, then we are done. We may thus assume that there exists a discriminant

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) = K_*$

, then we are done. We may thus assume that there exists a discriminant

![]() $\Delta_*$

such that

$\Delta_*$

such that

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_*}) = K_*$

and, for every

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_*}) = K_*$

and, for every

![]() $i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, either

$i \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

, either

![]() $\Delta_i = \Delta_*$

or

$\Delta_i = \Delta_*$

or

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) \neq K_*$

. Relabelling as necessary, we may assume that there exists some

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) \neq K_*$

. Relabelling as necessary, we may assume that there exists some

![]() $k \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

such that

$k \in \{1, \ldots, n\}$

such that

In particular, if

![]() $k+1 \leq i \leq n$

, then

$k+1 \leq i \leq n$

, then

![]() ${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) \neq K_*$

and so

${\mathbb{Q}}(\sqrt{\Delta_i}) \neq K_*$

and so

Observe that

\[ \sum_{i=1}^k a_i x_i^m = b - \sum_{i = k+1}^n a_i x_i^m,\]

\[ \sum_{i=1}^k a_i x_i^m = b - \sum_{i = k+1}^n a_i x_i^m,\]

where the sum on the right-hand side may be empty. Hence,

Since the

![]() $\lvert \Delta_i \rvert$

are effectively bounded (solely in terms of m, n) for

$\lvert \Delta_i \rvert$

are effectively bounded (solely in terms of m, n) for

![]() $i \geq k+1$

, there exists, by Proposition 2·8, an effective constant

$i \geq k+1$

, there exists, by Proposition 2·8, an effective constant

![]() $c_2(m, n)\gt0$

such that

$c_2(m, n)\gt0$

such that

Hence,

Since

![]() $\Delta_1 = \cdots = \Delta_k = \Delta_*$

, we may apply Theorem 1·5 to see that there exists an effective constant

$\Delta_1 = \cdots = \Delta_k = \Delta_*$

, we may apply Theorem 1·5 to see that there exists an effective constant

![]() $c_3(n)\gt0$

such that either

$c_3(n)\gt0$

such that either

or

In the first case, we are done. So assume then that

Then

\begin{align*} {}h(\Delta_*) &= {}[{\mathbb{Q}}(x_1) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]\\ {}&\leq [{\mathbb{Q}}(x_1, a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]\\ {}&= [{\mathbb{Q}}(x_1, a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}(a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m)]\\ {}&\quad \times [{\mathbb{Q}}(a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]\\ {}&\leq 2n c_2(m, n).\end{align*}

\begin{align*} {}h(\Delta_*) &= {}[{\mathbb{Q}}(x_1) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]\\ {}&\leq [{\mathbb{Q}}(x_1, a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]\\ {}&= [{\mathbb{Q}}(x_1, a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}(a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m)]\\ {}&\quad \times [{\mathbb{Q}}(a_1 x_1^m + \cdots + a_k x_k^m) \;:\; {\mathbb{Q}}]\\ {}&\leq 2n c_2(m, n).\end{align*}

Thus, by Proposition 2·7, there exists an effective constant

![]() $c_4(m, n) \gt 0$

, which depends only on m, n, such that

$c_4(m, n) \gt 0$

, which depends only on m, n, such that

![]() $\lvert \Delta_* \rvert \leq c_4(m, n)$

.

$\lvert \Delta_* \rvert \leq c_4(m, n)$

.

6·2. The proof of Theorem 1·3

The first part of Theorem 1·3 (i.e. the existence of the constant

![]() $c_1(n)$

) is given by the following proposition. It follows from Theorem 1·5 by an argument of Bilu and Kühne [

Reference Bilu and Kühne4

, section 3, step 4], which in turn relies on an earlier result of Kühne [