Introduction

This paper sets out to explain a dominant, curious and important pattern that emerges from our original dataFootnote 1 on financial regulation in the United States (US) and the European Union (EU)Footnote 2 between the Great Financial Crisis of 2008Footnote 3 and 2020. The two polities mostly preserved the tighter regulation that was ushered in as part of the political reactions to the crisis. The reforms are not stringent enough nor sufficient for many (Bieling, Reference Bieling2014; Rixen, Reference Rixen2013; Tsingou, Reference Tsingou2015b) and do not suggest a return to the Bretton Woods era of largely domestic finance and lower levels of international capital mobility (Helleiner, Reference Helleiner2014; Helleiner & Pagliari, Reference Helleiner and Pagliari2011; Nesvetailova & Palan, Reference Nesvetailova and Palan2010). Nevertheless, the data reveal the continuity of post‐crisis levels of regulatory stringency across a wide array of financial services.

This continuity is surprising. There was an effort across economic sectors to loosen US regulation under the Trump Administration (Belton & Graham, Reference Belton and Graham2019) – a trend that in finance would have put tremendous pressure on the EU to make a similar move. Moreover, the prolonged economic stagnation in Europe provided an incentive for politicians to boost lending and economic activity by relaxing financial rules (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Gabor and Hübner2018; K. L. Young, Reference Young2014). The pattern also poses a theoretical challenge. Finance after the crisis is one of the last sectors where leading arguments would have anticipated lasting regulatory stringency. According to the public salience logic, when attention to financial regulation quickly subsided, industry lobbies ought to have done better in bringing stringency levels down (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2011; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013b). Likewise, because the cross‐border mobility of financial entities and products continued to provide endless post‐crisis opportunities for regulatory arbitrage, business power arguments would also not expect stringency levels to have endured (Bradford, Reference Bradford2020).

The sustained stringency in the US and EU is not just puzzling. It is also important. Avoiding another meltdown of the global financial system is an international imperative. If regulation had been weakened before the pandemic's onset, the Covid‐19 economic shock might well have given rise to another financial crisis. The same can be said about Russia's invasion of Ukraine or the bank failures triggered by the central‐bankers' fight against inflation. Scholars generally agree that after the Great Financial Crisis, the US and the EU were essential to any lasting solution because transatlantic markets continued to dominate global finance (Mügge, Reference Mügge and Mügge2014, p. 14). Yet systemic financial stability, a global public good, qualifies as a hard cooperation problem. Financial regulation is intimately tied to domestic political economies (Hardie et al., Reference Hardie, Howarth, Maxfield and Verdun2013; Jackson & Deeg, Reference Jackson and Deeg2019) and the US and EU have strong incentives to support the competitiveness of their own financial industries, to attract international activity to their own money centres, and to let others bear the costs of stability with tough requirements (Singer, Reference Singer2007). What makes the finance case especially intriguing and important is that it may hold lessons for other global challenges in an era of rising multipolarity and complex interdependence.

Why and how, then, did Washington and Brussels sustain regulatory stringency? While multiple explanatory factors contribute to a satisfactory answer and each subsector will have idiosyncrasies, we emphasize the impact of an uncoordinated post‐crisis build‐up in both jurisdictions of capacities to impose steep costs on the other's firms – that is, border‐policing capacities created without a negotiated agreement. This novel explanation is rooted in theories about international economic interdependence (Farrell & Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2014, Reference Farrell and Newman2019b; Oatley, Reference Oatley2011, Reference Oatley2019), temporal process (Bach & Newman, Reference Bach and Newman2007, Reference Bach and Newman2010; Fioretos, Reference Fioretos2011; Newman, Reference Newman2008; Posner, Reference Posner2009, Reference Posner2010) and market power (Bradford, Reference Bradford2020; Drezner, Reference Drezner2007; Simmons, Reference Simmons2001). Specifically, it builds on research that conceives of market power as a product not only of large internationalized markets but also of regulatory capacities and on the insight that intergovernmental interactions can be a spillover of the international distribution of market power (e.g., hegemony vs. bipolarity vs. multipolarity) and affect internal regulatory outcomes, even in large jurisdictions, like the US and the EU (Kalyanpur & Newman, Reference Kalyanpur and Newman2019).

Our medium‐n study, combining congruence analysis (matching expectations and evidence for our explanation as well as those of others)Footnote 4 and process tracing (showing the presence of claimed causal mechanisms),Footnote 5 demonstrates the explanatory importance of interactions between two jurisdictions that had previously adopted strong border‐policing capacities. The enhancement of these capacities is a vital part of the post‐crisis financial regulatory reforms (Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018), yet it is largely unexplored by the leading accounts. The evidence reveals that over time it generated a causal mechanism – ‘joint reinforcement’ – which supports existing stringency levels because the potential penalties of one of the two jurisdictions prevent or temper the other from carrying out the typical watering down of rigorous regulation. The study finds, in sum, that the post‐crisis build‐up of roughly balanced border‐policing capacity in two jurisdictions with giant, equally dependent markets helped shore up domestic support in the other's political arena against pressure to loosen.

This article is organized as follows. The next section discusses the creation of our data, the empirical pattern that emerges from them, and why, upon consideration of leading explanations, a compelling puzzle remains. The subsequent section then develops the article's explanation and empirical expectations and is followed by a discussion of the main explanatory factor, the building up of border‐policing capacities after the Great Financial Crisis. The penultimate section reports on the findings of the congruence analysis and process tracing. Finally, after summarizing the findings, the conclusion discusses how our study pushes the limitations of qualitative research, contributes to a new generation of International Political Economy (IPE) theory attuned to holism, temporality and complexity, and feeds into debates about protecting global public goods.

Original data and puzzle

What are the dominant empirical patterns of the post‐2008 period in the two jurisdictions most responsible for setting the rules of global finance? Since there is no comprehensive set of data available on financial regulation, the first challenge was to create our own, usable for the purposes of this paper and, we hope, for further studies. The empirical material is drawn from the enormous literature of existing qualitative research – with holes filled by our original research and with coding decisions made with our combined expertise and judgment. To enhance transparency, we made these data publicly accessibleFootnote 6 and use the online Appendix to discuss the data‐creation processes, including the challenges of aggregating qualitative research, conceptualization issues, coding approaches and author positionality (Shesterinina et al., Reference Shesterinina, Pollack and Arriola2019; Soedirgo & Glas, Reference Soedirgo and Glas2020). The data provide comprehensive empirical material necessary for establishing dominant US and EU temporal patterns.

Regulatory stringency measures the relative rigor or laxity of a jurisdiction's rules. The level of regulatory stringency refers to the degree to which rules limit the discretion of companies and market participants in carrying out financial activities and organizing operations and mandate prescribed action. As a result, compliance with stringent rules tends to raise costs by requiring significant investment in resources (Drezner, Reference Drezner2007, p. 11). It should be noted that this usage does not engage in normative questions about what the regulatory goals should be, nor empirical questions about whether high or low levels of regulatory stringency achieve public policy goals, such as systemic stability or consumer protection. We use integers to classify the level of stringency, with 0 as very lax and 5 as very stringent. In making decisions for any given moment, we consider stringency levels that affect system stability, asking (i) whether a certain class of financial entity and activity is subject to public regulation; (ii) whether the rules are relatively specific and at what governance level they are set; and (iii) whether the rules allow for exemptions, involve thresholds of application, or leave room for regulatory arbitrage. We consider the EU as a whole and, hence, focus on EU rules, not national ones in the member states. This is important because in several financial services subsectors, such as hedge funds, credit rating agencies and insurance, there are instances of member states having domestic rules that are relatively stringent. Even so, if there are no EU rules, it is sometimes the case that regulation is lax (even as low as a 0 score) for the EU as a whole – when financial services companies are able to choose among European national regulations. We apply the same approach to the US for insurance where, in the absence of federal regulation, low pre‐crisis stringency scores in part reflect cross‐state variability and the resulting opportunities for regulatory arbitrage.

We created data points for 11 regulatory areas that cover a wide spectrum of financial services: accounting, auditing, banking (bank capital and liquidity, bank resolution and bank structure), derivatives (derivatives trading, clearing and central counterparties [CCPs]), securities markets (hedge funds and credit rating agencies) and insurance. Although this article focuses on explaining post‐crisis patterns, readers will find data covering four moments in time, spaced seven years apart, starting in 2000, when experts consider the EU to have joined the US as a global financial rule‐maker.

Empirical patterns

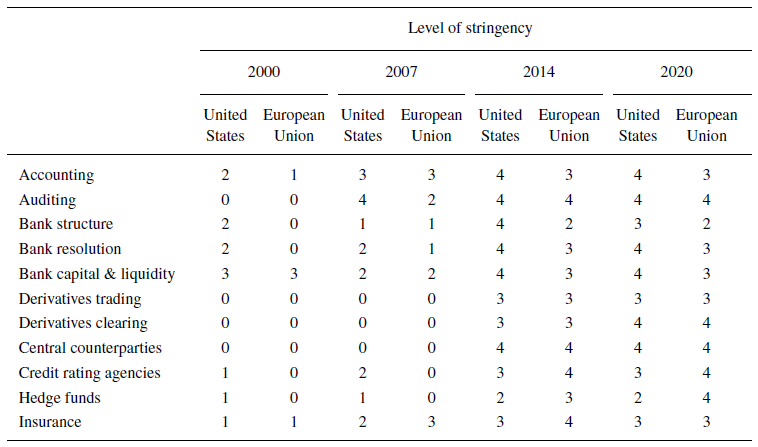

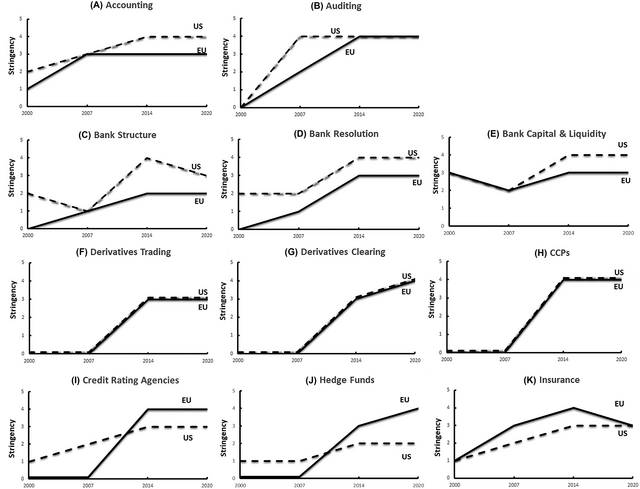

The data (compiled in Table 1) suggest a dominant post‐crisis pattern illustrated in Figures 1a–k: US and EU financial regulation generally stayed at the post‐crisis levels through 2020. The only exceptions are relatively small reversals in the regulation of bank structure in the US and insurance in the EU. Thus, we identify a 2008–2020 period of steady levels of tighter financial regulation.

Table 1. Financial regulatory stringency in the US and the EU

Figure 1a‐k. Financial Regulatory Stringency in the US and EU, by subsector.

A challenge for leading explanations for financial regulatory trends

What explains the persistent stringency of US and EU financial regulation in the dozen years following the Great Financial Crisis? We point out, in the empirical analysis below, where other explanations complement and interact with our own. However, there are good reasons to doubt, a priori, that the two leading approaches will offer satisfying explanations for the financial regulatory outcomes. The first is the well‐established public salience argument (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2011). In the aftermath of crises, when the public pays attention to financial regulation, the argument expects politicians and regulators to come under pressure to prioritize prudential considerations and financial stability and, thus, to put in place more stringent rules. Several studies on the years immediately after the crisis find strong empirical support for this proposition (Kastner, Reference Kastner2017; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013b; Woll, Reference Woll2013). Yet according to the argument's logic, as memories of the crisis faded and public salience levels decreased substantially soon after the crisis,Footnote 7 financial industry voices should have regained influence, with the result of regulatory loosening. The pattern of persistent regulatory stringency thus represents a challenge to the public salience approach.

The second explanation, featuring transnational corporations in the financial sector, can be found in a vast literature that considers multiple types of business power (McKeen‐Edwards & Porter, Reference McKeen‐Edwards and Porter2013; Porter, Reference Porter2014; for overviews of financial industry power, see Baker, Reference Baker2010) ranging from structural and infrastructural (Bell & Hindmoor, Reference Bell and Hindmoor2015; Braun, Reference Braun2020; Culpepper & Reinke, Reference Culpepper and Reinke2014) to instrumental (Young & Pagliari, Reference Young and Pagliari2017; Pagliari & Young, Reference Pagliari and Young2014; Young, Reference Young2012), ideational (Baker & Underhill, Reference Baker and Underhill2015; Tsingou, Reference Tsingou2015a) and passive (as in the power of inaction) (Woll, Reference Woll2014). The expected regulatory outcomes are similar for most of these arguments. We thus emphasize the one rooted ultimately in the global mobility of capital (Laurence, Reference Laurence2001) since high‐profile studies invoke capital mobility (i.e., ‘elasticity’ of financial services) as the primary reason why a great regulatory power (like the US or the EU) is unlikely to maintain and spread stringent regulation in the financial sector, as it is in so many other areas (such as chemicals and data protection) (Bradford, Reference Bradford2020). Because the owners of capital and financial services companies, and their activities, are said to be empowered by the ability to relocate easily across borders, this explanation expects a tendency towards regulatory arbitrage and a race to the bottom. The post‐crisis empirical pattern of persistent financial regulatory stringency is therefore a conundrum for the transnational business explanation, just as it is for the public salience argument.

A novel market power explanation rooted in border‐policing capacities

Our explanation, by contrast, belongs to the theoretical tradition featuring market power as a cause of the rules governing domestic and global economic activity (Drezner, Reference Drezner2007; Simmons, Reference Simmons2001). Market power, a political resource derived from economic interdependent relationships, is the product of large internationalized markets combined with regulatory capacities, which are ‘a jurisdiction's ability to formulate, monitor, and enforce a set of market rules’ (Bach & Newman, Reference Bach and Newman2007, p. 831). Originally employed to explain patterns in trade, market power, according to a large body of research, was a decisive factor in shaping the outcomes of prominent conflicts concerning the regulation of food and Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), data privacy, chemicals and finance (Bach & Newman, Reference Bach and Newman2010; Bradford, Reference Bradford2020; Mattli & Woods, Reference Mattli and Woods2009; Newman, Reference Newman2008; Posner, Reference Posner2009; Young, Reference Young2015). The existing work recognizes the relative abundance of US and EU market power in the early decades of the 21st century and interprets it as a cause of their rule‐making roles in the global economy and especially in global finance.Footnote 8

In the post‐crisis context, the most important market‐power development is the dramatic increase in both the US and the EU of a central element of regulatory capacities: border‐policing capacities, that is, the ability of public authorities to regulate and supervise foreign entities and transactions and to impose and enforce requirements they must meet to access domestic markets. For real‐world and theoretical reasons, political scientists, focusing on the marked increase in regulatory stringency, have not given enough thought to this market‐power development nor to the potential explanatory role of border‐policing capacities.

Border‐policing capacities stem largely from formal and informal rules and institutional arrangements that fall into two main categories (Brummer, Reference Brummer2015; Coffee, Reference Coffee2014; Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018). First are those reflecting the principle of ‘territoriality’, whereby jurisdictions regulate foreign entities and transactions within their borders. Since defining geographic borders for regulatory purposes is not always straightforward, ‘territorial proxies’ (meaning, territorial contacts) are often used (Brummer, Reference Brummer2015). For example, foreign banks, insurers or investment firms providing services (i.e., taking deposits, selling insurance policies or trading securities) in a host country are subject to its rules. In practice, that means that foreign firms are given national treatment without discrimination, or the host country applies specific rules only to alien firms. The external effects of rules based on the principle of territoriality are sometimes unintentional.

Second are rules and institutions based on the principle of ‘extraterritoriality’, whereby a host country applies regulation directly and exclusively addressed to foreign entities (Coffee, Reference Coffee2014). Examples include post‐crisis rules on foreign banks and intermediate holding companies in the US and the EU. Furthermore, even the most inconsequential contact with a country (notably, via territorial proxies, what Scott (Reference Scott2014) calls ‘territorial extension’) may trigger its regulatory power, which can also arise whenever foreign transactions have an effect on that country. After the 2008 crisis, several US and EU rules on derivatives fit into this category (Coffee, Reference Coffee2014; Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018).

Scholars disagree on the extent to which a build‐up of market power (whether from border‐policing capacities or other sources) is likely to shape the domestic regulation of great powers. Drezner's model (Reference Drezner2007) assumes that even when there are two regulatory giants, neither concerns itself with the other when developing initial preferences, and the analysis leaves little room for the impact of US‐EU interactions on the regulation of either. In keeping with recent theoretical insights about international systemic holism and complexity (Alter & Meunier, Reference Alter and Meunier2009; Farrell & Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2014, Reference Farrell and Newman2019a; Kalyanpur & Newman, Reference Kalyanpur and Newman2019; Newman & Posner, Reference Newman and Posner2018; Oatley, Reference Oatley2019), by contrast, our innovation is to stress the deeply interpenetrating effects of international spillovers from domestic build‐ups, emphasizing the potential causal impact of such international factors (system‐level variables in the International Relations (IR) literature; see Jervis, Reference Jervis1997; Oatley, Reference Oatley2011, Reference Oatley2019). Unlike under hegemony, when one jurisdiction with a great deal of market power compared to others is largely unaffected by what they do, in bipolar arenas the actions of one market power giant are said to affect the other. By this logic, even ‘great’ regulatory powers are not sealed off from forces beyond their political borders. Authorities in the US and EU adjust and base their goals and behaviour in response to what their counterparts do (or what they believe they will do) under various circumstances.

Causal mechanism and empirical expectations

How exactly might the post‐crisis introduction of strong internal border‐policing capacities in two powerful jurisdictions help prop up the relatively high levels of regulatory stringency? We envision a two‐step, temporal process predicated on a relatively balanced interdependent relationship. We argue that separate US and EU build‐ups of this kind at t 1 would affect the subsequent interactions in ways that limit reductions in stringency levels. By this logic, the specific causal mechanism ‐ ‘joint reinforcement’ – would support the status quo by undermining efforts to loosen regulation in either jurisdiction and thus add to the forces preserving levels of stringency.

Empirical expectation: Under conditions of relatively even interdependence, we would expect the simultaneous introduction of strong and even border‐policing capacities to act as a deterrent to either jurisdiction lowering its level of regulatory stringency – in effect, to help lock in the existing levels. By making it clear that a shift towards regulatory laxity would be met with penalties (in the form of extra regulatory costs to firms wanting to have access to the other polity's markets and customers), a jurisdiction would reduce the likelihood of the other's ‘defection’ from high stringency levels. In other words, authorities and others in favour of the status quo would be better armed to fend off industry efforts to loosen regulation after public salience levels subside – because of the decreased benefits of doing so. Hence, in the post‐crisis context, the expectation is, ceteris paribus, support for continuity of relatively stringent rules in both jurisdictions and evidence of US and EU signalling that they would impose penalties if the other weakened regulation.

To be clear, our claim is not to be able to explain every aspect of all cases but rather that joint reinforcement is likely to buoy stringency levels when two jurisdictions – with mutually reliant, large markets and equally stringent regulation – create roughly the same border‐policing capacities. This combination of conditions characterizes most (but not all) sectors of the post‐crisis EU–US financial regulatory relationship.

The origins and evolution of border‐policing capacities in the US and the EU

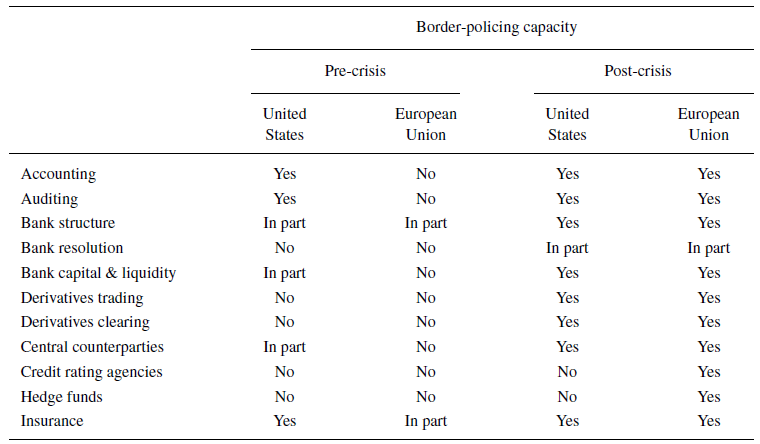

Prior to the Great Financial Crisis, the US and, especially, the EU, had limited formal border‐policing capacities, often because existing territorial rules were accompanied by exemptions. After the crisis, with a few exceptions, the US and the EU developed more‐or‐less equal border‐policing capacities. We first use Table 2 to outline this overall pattern visually and then give a more detailed description of the origins and post‐crisis strengthening of border‐policing capacities in the US and the EU.

Table 2. US and EU border‐policing capacity pre‐ and post‐crisis

We derived the table's data and the detailed description, below, from US and EU legislation and other rules as well as the secondary literature. References and more detailed narrative explanations for each coding decision are publicly available and are stored here (https://doi.org/10.5064/F6QR17WM) in the Qualitative Data Repository (Posner & Quaglia, Reference Posner and Quaglia2023).

Table 2 classifies border‐policing rules as ‘yes’ (strong rules), ‘in part’ (weak, incomplete or uneven rules) or ‘no’ (no rules). A few further points of elaboration are in order. We have compiled the data primarily from legislation and existing studies (mostly, by legal scholars) but are aware that examining the legal rules does not account for the unwritten powers of regulatory agencies. Nor does it include the willingness of regulators to use available legal powers. Nonetheless, in our judgement, the data in Table 2 capture the post‐crisis empirical evolution of border‐policing capacities and are consistent with other research (Brummer, Reference Brummer2015; Coffee, Reference Coffee2014; Davies, Reference Davies, Cremona and Scott2019; Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018; Scott, Reference Scott2014).

Before the crisis

US federal authorities before the crisis had border‐policing capacities in some financial subsectors. These stemmed in part from the agencies’ mission, independence and resources, sometimes dating back many decades. For instance, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) had the authority to limit negative externalities for the US securities market by controlling foreign firm access and forging memoranda of understanding with foreign officials (Bach & Newman, Reference Bach and Newman2010). This power was manifest, for example, in the SEC's requirement that foreign public companies, wanting to raise funds from US markets, had to use (or reconcile financial statements with) the US Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (Posner, Reference Posner2009, pp. 26–27). The border‐policing capacities of US authorities also derived from specific provisions in security laws, notably, language that at times required extraterritorial reach (Newman & Posner, Reference Newman and Posner2018). Under the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board's mandate to carry out direct public regulation of public company auditors included the power to inspect the foreign auditor of a US‐listed company, even when the former is operating in a foreign jurisdiction (Posner, Reference Posner2010).

US laws also empowered banking authorities with border‐policing capacities. The Foreign Bank Supervision Enhancement Act of 1991 gave the Federal Reserve the authority to assess home‐country supervisors of foreign banks and request the consolidated supervision of the foreign–parent companies of US banking operations. Yet these powers were often not employed or were overshadowed by a liberal use of exemptions and exceptions. The latter was especially notable with the Federal Reserve's use of exemptions following the Financial Services Modernization Act (also known as Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act) of 1999. In insurance, despite the absence of a federal regulatory regime, the consistency of state laws gave state officials and, by extension the US as a whole, border‐policing capacity. These laws had specific provisions for ‘alien’ (i.e., third country) reinsurers that required the firms to operate through a US subsidiary (and be treated as a national reinsurer) or to post collateral for the value of their commitments in the markets (US states) where they conducted business (Singer, Reference Singer2007, pp. 96–113). Finally, in several financial services areas – including derivatives, credit rating agencies and hedge funds – the US did not have border‐policing capacities. In these subsectors, characterized by private industry self‐governance and not subject to direct public regulation (Lockwood, Reference Lockwood, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2012; Woll, Reference Woll2013), authorities only had a limited need to police foreign‐firm compliance.

Until 2000, EU border‐policing capacities were almost non‐existent. In that year, the relative centralization of regulatory processes in Brussels and the harmonization of rules across the EU sped up (Grossman & Leblond, Reference Grossman and Leblond2011; Mügge, Reference Mügge2010), and the EU began experimenting with some border‐policing capacities with the aim of ensuring foreign‐firm compliance. These took the form of provisions in legislation requiring ‘third country equivalence’.Footnote 9 However, in the pre‐crisis period, the language was relatively weak, delegating few independent powers to EU‐level bodies and, thus, allowing firms to play one national regulator off another across the EU (as apparently happened in the case of financial conglomerates, when UK authorities accepted as equivalent relatively lax US rules) (Posner, Reference Posner2009, fn 113).

After the crisis

Following the Great Financial Crisis, both the US and the EU greatly enhanced border‐policing capacities. Some of these were rooted in new laws that formalized the powers of regulatory authorities, increasing their ability to police foreign compliance with domestic rules and decreasing their latitude to extend exemptions and exceptions. This trend was towards stronger territorial rules governing foreign companies that had previously been granted more liberal terms of access. Other new capacities derived from laws that created or clarified the principle of extraterritoriality. Indeed, the period saw a general proliferation of new rules in both the US and EU covering foreign entities and transactions that only partly or tangentially took place within their respective territory or had arguably indirect effects on it (Brummer, Reference Brummer2014; Coffee, Reference Coffee2014; Scott, Reference Scott2014).

Although this study is an investigation into the effects, not the causes, of the capacities build‐up, we note some contributing factors. In several instances, Brussels and Washington created the new capacities in reaction to the other's extraterritorial bid to foist its rules on firms and markets domiciled on the other side of the Atlantic (Brummer, Reference Brummer2014; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013a). Sometimes such reactions sought to ensure a level playing field for domestic companies. As a whole, however, the roughly simultaneous build‐up of comparable capacities on both sides of the Atlantic reflected similar, internally generated responses to financial regulatory failure (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2014; Ryan & Ziegler, Reference Ryan, Ziegler and Mayntz2015; Ziegler & Woolley, Reference Ziegler and Woolley2016). While the research has mostly focused on crisis‐induced increases in regulatory stringency, the new prioritization of financial stability and prudential concerns also prompted US and EU legislators to strengthen border‐policing capacities. In a nutshell, these capacities were perceived as tools commensurate with the challenges of implementing the post‐crisis prudential regulatory agenda in highly internationalized financial markets (Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018, p. 83). The strengthened capacities were to help close regulatory loopholes that cross‐border firms had successfully exploited in the pre‐crisis years and to make sure the other polity's regulatory laxity did not leave home firms at a disadvantage. Specifically, border‐policing capacities were to achieve these goals by better controlling foreign firm access to domestic markets and deploying home regulation and supervisory influence beyond domestic borders (Brummer, Reference Brummer2014; Scott, Reference Scott2014).

In the US, the Dodd–Frank Act strengthened previous capacities and added new ones, sometimes by removing exemptions and thus bolstering the territorial principle (Brummer, Reference Brummer2014; Zaring, Reference Zaring2020), other times by giving regulatory agencies powers to enforce stringent new rules beyond US borders. In the latter instances, agencies sometimes interpreted the provisions in ways that gave them maximum extraterritorial reach (Coffee, Reference Coffee2014; Ryan & Ziegler, Reference Ryan, Ziegler and Mayntz2015). In banking, the Dodd–Frank Act's Volcker rule had this type of extraterritorial scope and the Collins Amendment removed an exemption granted by the Federal Reserve to foreign banks in 2001, together contributing to border‐policing capacity across banking subsectors. A similar broad enhancement occurred when prudential banking regulators (the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) issued new rules for foreign banks with $100 billion or more in US assets (Coffee, Reference Coffee2014). In addition, US capacities were strengthened by the implementation of the specific Dodd–Frank provisions concerning the resolution of banks and, in particular, the requirement of a single point of entry resolution strategy plan (Ziegler & Woolley, Reference Ziegler and Woolley2016). Yet because of the complexities of resolving large international banks, foreign or domestic, we consider this enhancement to be relatively modest.

The strengthening of border‐policing capacities in the derivatives subsectors was even more pronounced. In implementing Dodd–Frank Act provisions on derivatives trading, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) adopted an expansive extraterritorial definition of a US person (Marjosola, Reference Marjosola2016; Ryan & Ziegler, Reference Ryan, Ziegler and Mayntz2015) and an equally broad interpretation of which foreign trading venues would fall under US rules and, therefore, needed to register with the CFTC (Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018). The CFTC also issued rules on derivatives clearing that applied to financial and non‐financial counterparties, even when a non‐US counterparty was involved, and required CCPs wishing to clear derivatives for US market participants to register in the US and set specific requirements. The Dodd–Frank Act granted the CFTC the authority to exempt third‐country CCPs from registration if they were subject to ‘comparable, comprehensive supervision and regulation’ (Coffee, Reference Coffee2014). However, for several years, the CFTC issued only targeted exemptions on a transitional basis (Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018).

In three subsectors, the US did not strengthen border‐policing capacities in the post‐crisis period. US firms dominated the hedge fund and credit rating agency markets. Hence, the US legislators and authorities appear to have felt little need to increase capacities in these sectors as relatively few foreign firms operated under their jurisdiction. It was a situation of asymmetrical interdependence, which may have contributed to a relative lack of concern about negative externalities from European regulation. Finally, in insurance, US border‐policing capacities, developed before the crisis (see above), remained more or less the same, despite the Dodd–Frank Act reforms (which introduced a role for the US Treasury Department to represent the US in international negotiations) and the 2017 US and EU Covered Agreement (which addressed areas where state insurance laws treated US insurers differently from non‐US insurers; Stubbe, Reference Stubbe2019).

In the EU, the build‐up of border‐policing capacities was more comprehensive than in the US. All the major post‐crisis financial regulatory reform packages included equivalence provisions that were more consistent than in the pre‐crisis period and centralized more delegated power to EU‐level bodies (Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013a; Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2015; Scott, Reference Scott2014). The pre‐crisis equivalence experiment (specifically, provisions in the Financial Conglomerates Directive) became the template for post‐crisis legislation.

In accounting and auditing, EU capacities emerged from the creation of new equivalence regimes. In both subsectors, the process began with the implementation in 2008 of legislation adopted before the crisisFootnote 10 and was strengthened with the passage of subsequent pieces of legislation.Footnote 11 Concerning bank structure, capital and liquidity requirements and resolution, the Capital Requirements Directive V (2019) and the Capital Requirements Regulation II (2019) strengthened border‐policing capacities by mandating large non‐EU (‘third country’) banks to establish an EU ‘intermediate holding company’ subject to capital, liquidity and leverage rules on a consolidated basis (James & Quaglia, Reference James and Quaglia2020). We emphasize the relatively late date of this capacity enhancement, May 2019, as it becomes important in the empirical analysis. Moreover, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (2014) empowered EU resolution authorities to recognize third‐country resolution actions. In other words, the EU could decide to grant this recognition (Art. 94) but could also refuse to do so (Art. 95). The EU could likewise stipulate resolution cooperation agreements with third countries (Art. 93) but decided not to do so. As in the US case, the EU capacity to police foreign banks in the area of resolution planning is somewhat weaker than in the other banking subsectors.

As for derivatives trading, the new EU capacities were rooted in the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II, which set obligations to trade derivatives on organized venues. Moreover, the European Market Infrastructure Regulation set clearing obligations also for third‐country (non‐EU) counterparties when Union counterparties traded with entities established outside the EU, or two entities established outside the EU traded together, with a direct, substantial and foreseeable impact on EU markets (Buxbaum, Reference Buxbaum2016; Marjosola, Reference Marjosola2016). Finally, the Regulation set rules for CCPs (for instance, on margins, default funds and liquidity) as well as equivalence provisions designed to allow foreign CCPs to provide their services to EU counterparties on the basis of their home country regulation (Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013a).

Unlike the US, the EU built border‐policing capacities after the crisis in the areas of credit rating agencies and hedge funds. The regulation on Credit Rating Agencies (CRAs) prescribed two ways that credit ratings issued outside the EU could be used in the EU for the regulatory purposes of calculating bank capital requirements (Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013a). Likewise, the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive issued in 2011 enabled the EU to develop capacity in the hedge fund subsector, introducing equivalence provisions for non‐EU alternative investment funds and fund managers (Scott, Reference Scott2014), and in 2017, the EU took additional steps to strengthen rules regarding third (i.e., non‐EU) countries. Finally, in insurance, the Solvency II directive (2009) enhanced EU border‐policing capacity on insurers as it contained rules on third countries. These provisions stipulated that the supervisory authorities must verify whether third‐country insurance and reinsurance companies were subject to home country supervision that was equivalent to that provided for in Solvency II (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2014).

Empirical analysis

Having discussed the origins and evolution of border‐policing capacities in the US and the EU, we use congruence analysis and process tracing to assess the extent to which the post‐crisis configuration of these capacities generated the expected causal mechanism and, thereby, served as a primary explanatory factor behind the sustained levels of regulatory stringency. We also consider the empirical leverage of other explanations.

Congruence analysis

The logic of congruence is an informative first‐cut analysis to evaluate empirical expectations against the data (Beach & Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2016, pp. 269–300). As noted above, the mismatch between empirical expectations and outcomes raises serious doubts about the adequacy of public salience and transnational business power explanations. Does ours, featuring market power, border‐policing capacities and the joint reinforcement mechanism, do better?

The Great Financial Crisis ushered in a sustained period of tighter US and EU regulation that had remained for more than a decade by 2020.Footnote 12 In seven of the 11 subsectors, the empirical record is tightly congruent with our joint reinforcement expectation that when both the US and the EU have strong border‐policing capacities, the potentially high penalties in the form of access costs to the market of the other major jurisdiction would diminish the anticipated benefits of watering down domestic regulation and, thus, deter such action. Juxtaposing the US loosening of stringency levels (Figure 1c) and the relative parity in capacities (Table 2), the bank structure cases are incongruent on the surface. Yet, as elaborated in the process‐tracing sections, these cases – like the other banking ones – display strong evidence of the joint‐reinforcement mechanism, as they show how EU threats helped to prevent the Trump Administration and transnational financial lobbies from dismantling the main pillars of the post‐crisis Dodd–Frank Act.

Another subsector, insurance, appears only partially congruent, exhibiting EU regulatory loosening to US levels, despite border‐policing capacities in both jurisdictions. Observing the timing of events is helpful. The EU's lowering of stringency levels occurred at about the same time as the 2017 Covered Agreement. The evidence for the insurance subsector is thus consistent with the joint reinforcement mechanism until the signing of the agreement. Then, more cooperative EU–US interactions set in, leading to a multifaceted agreement reflecting mutual accommodation and a newfound acceptance of deference as a regulatory principle. Again, we explore these cases in more detail below.

Finally, two subsectors (CRAs and hedge funds) exhibited sustained stringency but lacked symmetry in border‐policing capacities as well as core characteristics present in the other cases (i.e., balanced interdependence). As might be expected, the result is a process quite different from the joint reinforcement mechanism. In fact, we suspect a dynamic similar to the one Drezner (Reference Drezner2007) depicts, whereby neither of the regulatory giants has much leverage over what the other does. As explained in the previous section, the US authorities did not appear to see a need for border‐policing capacity. Threats to punish foreign firms would have had little purpose as almost all CRAs and the vast majority of hedge funds were based in the US (Fioretos, Reference Fioretos2010; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2012). By contrast, the EU, a host jurisdiction reliant on these US financial services firms, deliberately beefed up its capacity to ensure that the firms, when operating in Europe, meet high EU stringency rules (Woll, Reference Woll2013) – even though Brussels had little leverage over US regulations, which never increased to EU levels.

Process tracing

Delving deeper than the correlational logic of congruence analysis, we process trace to see whether the outcomes were generated via the ascribed causal mechanism. While including all 11 regulatory areas would be beyond this paper's scope, process tracing within the derivatives and banking cases offers substantial additional support for our explanation.

We begin with derivatives because of their sheer importance (Helleiner et al., Reference Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018). As the world's largest markets, derivatives are critical cases in the sense that an explanation's usefulness would be much reduced if it could not account for them. In addition, they are ‘least‐likely’ cases for the study's puzzling outcome concerning the persistence of stringency levels. In fact, the derivatives industry's early backlash against post‐crisis regulatory reforms was arguably fiercer than in other subsectors (Brush & Schmidt, Reference Brush and Schmidt2013); thus, one might have expected successful watering down of the new direct public regulatory regime. Furthermore, for years, both the US and EU officials stubbornly and acrimoniously insisted on foreign firm compliance with their respective homegrown templates, generating several transatlantic regulatory disputes (Coffee, Reference Coffee2014; Farrell & Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2014; Knaack, Reference Knaack2015). Yet, by 2020 it was clear that the US and the EU had preserved high levels of stringency. Process tracing enables us with a high degree of confidence to attribute this surprising outcome to the joint reinforcement causal mechanism.

As indicated in the above analysis, the derivatives cases exhibit the building up of strong, roughly equal post‐crisis border‐policing capacities in both the US and the EU. Specifically, the cases display new rules that created enhanced capacities for making conformity with host regulation the price of market entry for foreign firms as well as for creating extraterritorial extension of home regulation (for instance, concerning derivatives transactions taking place outside the US, but involving a US person). As outlined in the preceding section, in the US these powers derive from a combination of provisions in Title VII of the 2010 Dodd–Frank Act and the CFTC's expansive interpretation of them (Newman & Posner, Reference Newman and Posner2018, pp. 141–152). In the EU, the new powers stem from the equivalence provisions of the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (2012) and the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (II) (2014) (Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018, pp. 95–99).

There is congruence between the presence of these strong capacities and the empirical expectations that such a configuration would lead to persistent stringency levels. In fact, it is striking the extent to which US–EU interactions by 2020 centred on the relative stringency of US and EU rules, and specifically, on concerns among regulatory authorities about whether the other jurisdiction's regulation was governing CCPs and trading venues as stringently as domestic rules (for instance, one‐sided or dual‐sided derivatives trade reporting, the size of CCP's default funds, the collection of margins on net or gross basis, etc). Although both the US and the EU tightened the domestic regulation of derivatives after the crisis, their respective rules were not identical and important differences remained. Whenever this was the case, the jurisdiction with the more stringent provisions, be it the US or the EU, put pressure on the other jurisdiction to tighten its domestic regulation in order to pave the way to the recognition of each other's rules (Davies, Reference Davies, Cremona and Scott2019, p. 8).

Is there evidence – ‘mechanistic evidence’ in Beach and Pedersen's parlance (Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, pp. 4, 155–194) – showing that enhanced regulatory capacities generated these outcomes via the mechanism expected in the joint reinforcement empirical expectation? We looked for – and found – evidence of the US and EU signalling that they would impose costly penalties if the other loosened regulation. On the US side, the lead derivatives authority made it abundantly and publicly clear that US extraterritorial policies were being driven by suspicions that the EU (and, especially, London) would revert to lower levels of regulatory stringency. The Chairman of the CFTC, Gary Gensler, warned against London's light‐touch regulation in public speeches and in Congressional testimony beseeched lawmakers to insert extraterritorial provisions in the Dodd–Frank Act (Newman & Posner, Reference Newman and Posner2018, pp. 146–147; Gensler, Reference Gensler2009).

On the EU side, the evidence is clearest in the CCP's case, in which Brussels’ distrust of US regulation emerged in its refusal to accept Washington's regulation as equivalent (Gravelle & Pagliari, Reference Gravelle, Pagliari, Helleiner, Pagliari and Spagna2018). For instance, a senior European Commission official, Patrick Pearson, noted that to operate in the US, European CCPs had to register with the CFTC and comply with US rules:

While you may be only facing four or five dual registered CCPs in that country [the US], I can guarantee you within 48 months that country will have to regulate two or three handfuls of CCPs. To do that they are going to need money and staff, and looking at the budgets of regulators around the world, we are not too sure the money is going to be there to do that job. (Pearson, in Parsons, Reference Parsons2014)

This evidence supports our argument attributing the persistence of high levels of stringency to the equally enhanced capacities and a mutual understanding of the potential costs of lowering regulatory stringency.

The joint reinforcement explanation's usefulness would also be much diminished if it could not account for the banking subsectors, which, like derivatives, are central to global finance and displayed general congruence between the presence of border‐policing capacities and the empirical expectations that such a configuration would support sustained stringency levels. As in derivatives, there is substantial evidence of US and EU signalling that they would respond to regulatory weakening with penalties. The most important evidence is the unvarnished EU response to the 2017 Trump Administration's plans to reduce regulatory stringency by dismantling the 2010 Dodd–Frank Act, with the banking subsectors as a main target (Protess, Reference Protess2017). Multiple factors combined to frustrate this effort and, instead, produce the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief and Consumer Protection Act of 2018, which sustained regulatory stringency for systemically important banks, even though it lowered levels for smaller, mostly local, banks. Yet the EU threats played a big part, suggested by the fact that the 2018 regulatory changes avoided loosening standards for US‐based Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs) with large European operations (over which Brussels had leverage) and modified rules that the EU had long considered unfair.

In 2017, the EU warned the Trump Administration that relaxing rules for large SIFIs would cross a red line. Valdis Dombrovskis (Reference Dombrovskis2017), vice president of the European Commission, threatened to lock out US banks from European markets if Washington repealed rules adopted in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis. ‘We [the EU] are sensitive to talk of unpicking financial legislation which applies carefully negotiated international standards and rules…Lax regulation in one country can create conditions for inadequate regulation and contagion throughout the world’ (Dombrovskis, Reference Dombrovskis2017). He noted that the EU allowed financial firms from the US to operate in the single market because US home rules were deemed to be ‘equivalent’ or as strict as the EU's. Thus, if US rules changed, the EU would have to reassess the situation (Dombrovskis, Reference Dombrovskis2017). In the end, these potential retaliatory costs were important elements in US legislators’ calculations to limit the parts of the Dodd–Frank Act targeted by the 2018 law and provide strong evidence showcasing the joint reinforcement mechanism at play.

Moreover, of the few areas of ‘successful’ US loosening, two of the main ones were actually ‘level‐playing‐field’ bank structure issues, favoured by Brussels officials and banks, which had long claimed that the US rules had unfairly disadvantaged European competitors. To begin with, the Volcker rule was ‘adjusted’ in 2019. From the moment the original Rule was adopted in 2012, it had elicited a negative response from European banks and policymakers, who fiercely criticized the extraterritorial effects. In a letter to the Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Ben Bernanke, Michael Barnier (Reference Barnier2012), the European Commissioner in charge of the single market, argued that the Volcker rule should focus only on trading activities that occurred in the US. It is notable that this perception of the rule as an unfair, extraterritorial overreach was shared by policymakers from France, Germany, Canada, Japan and other countries which coordinated their responses with the EU (Lavelle, Reference Lavelle and Porter2014).

The other issue concerned the narrowing of requirements for foreign banks operating in the US. This change acknowledged the legitimacy of the EU's rejection of claims frequently made by the Obama Administration's leading US banking regulator, Federal Reserve Board Governor, Daniel Tarullo (Reference Tarullo2014), that the new requirements would bring US regulation into line with longstanding EU practice. Pushing back, European policymakers and banks operating in the US, such as Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas and Barclays, complained that the requirements put them at a competitive disadvantage vis‐à‐vis American banks that operated overseas (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2013). Barnier (Reference Barnier2013), in a letter to Bernanke, argued that

to avoid unnecessary administrative burdens and duplicative regulatory costs of foreign institutions active in the EU, the EU framework exempts foreign banking subsidiaries from certain requirements…provided, in their home jurisdiction, they are subject to a regulatory and supervisory framework equivalent to that of the EU. I would hope that the same approach is implemented also by all other jurisdictions.

He concluded that the US rules on foreign banking organizations ‘could spark a protectionist reaction from other jurisdictions’ (Barnier, Reference Barnier2013).

Other explanations

In addition to supplying strong evidence in support of our argument, congruence analysis and process tracing illuminate the inadequacies and contributions of other explanations. The changes to the Volker rule and foreign bank requirements are examples. While small victories for European banks, these episodes point to limited and extreme conditions that appear necessary for banking lobbies to have the kind of influence envisioned in the transnational business power argument (Porter, Reference Porter2014; Young & Pagliari, Reference Young and Pagliari2017; Pagliari & Young, Reference Pagliari and Young2014; Young, Reference Young2012). In this narrow case, the latter argument correctly anticipates massive post‐crisis mobilization of the transnational financial industries on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet the primary winner in the 2018 US Act was the small and regional bank lobby, not the transnational one. Moreover, across our cases, during the years under study, the lobbying amounted to little more than ironing out transatlantic financial disputes. And when it did so, as in the bank structure and derivatives cases, the outcomes without fail preserved the high levels of stringency, typically a second‐best solution from the perspective of the industry. In the main, the business power explanation underappreciates the extent to which the dynamics between ‘like‐minded’ regulatory giants can limit mobility and serve as a buoy against lobbying from industry.

Similarly, the public salience argument (Culpepper, Reference Culpepper2011; Kastner, Reference Kastner2017; Pagliari, Reference Pagliari2013b) correctly accounts for the ratcheting up of financial regulation in both the US and the EU in the wake of the 2008 crisis. However, unless post‐crisis public salience levels are higher than we (and other scholars) estimate (see note 7), the argument simply cannot explain the persistent level of stringency. The post‐crisis deregulatory faction – spearheaded by transnational financial services providers – ought to have been more successful in loosening regulation than in the few level‐playing‐field bank structure instances.

Lastly, we return to the intriguing empirical finding that, in some cases, towards the end of the period under study, institutionalized cooperation emerges as an important contributor to sustained stringency. Until 2017, the insurance cases fit well with the joint reinforcement mechanism. Even after the US and the EU announced the Covered Agreement, some stakeholders interpreted the deal as a continuation of authorities using potential penalties to maintain regulatory stringency in the other's jurisdiction. For instance, Ted Nickel, President of the National Association of Insurance Commissions, worried that the agreement was a ‘backdoor to force foreign regulations on US companies’ (reported in Dentons, 2017). In fact, the Covered Agreement employs deference arrangements as an additional way to preserve stringency. The slight EU reduction in insurance stringency levels reflects a context in which harmonization helped to make reciprocal trust in the other's regulation possible. According to Michael McRaith, director of the Federal Insurance Office within the US Treasury, the agreement is ‘a critical step towards levelling the playing field for American insurers and reinsurers’ (reported in Dentons, 2017).

The derivatives cases followed similar sequences. After years and years of disputes over regulatory differences (despite similar levels of stringency) in which both sides made ample use of threats to the other's firms, the CFTC and the European Commission agreed to a ‘Common Approach for Transatlantic CCPs’ in 2016 (CFTC, 2016) and in 2017 devised a ‘Common Approach on Certain Derivatives Trading Venues’ (CFTC, 2017). At about the same time, they acted as pace‐setters (Quaglia, Reference Quaglia2020) in the development of standards issued by international standard setting bodies, such as the Financial Stability Board (2017, 2019) and the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures–International Organization of Securities Commissions (2017a, 2017b). As in the insurance cases, in derivatives, the development of institutionalized regulatory cooperation contributed to sustained stringency.

Conclusion

At the heart of this investigation is a real‐world puzzle about the post‐crisis continuity of stringency levels in US and EU financial regulation. A rich literature of qualitative research covers many of our cases and offers a range of explanatory factors. However, it took our medium‐n, multi‐year view to reveal the importance of the distribution of market power across subsectors and over time. Of particular importance was the development of border‐policing capacities after the Great Financial Crisis. The build‐up triggered a cross‐border interaction – joint reinforcement – that, across cases, raised the costs of watering down the new stringent regulation.

A problem‐driven, explanation‐oriented study like this one will have well‐known limitations. Even so, our evidence suggests it could have substantial explanatory power as well as implications for theory and real‐world challenges. First, our response to the contextually circumscribed explanatory power of a study of this kind has been to increase the number of data points beyond what has become the outer boundary in qualitative research. The task created an opportunity that we believe takes this investigation to the forefront of efforts to balance the many growing demands on qualitative research (Checkel, Reference Checkel, Pevehouse and Seabrooke2021). We sought to accumulate knowledge, mostly siloed in the qualitative studies of several subfields; to preserve the strengths derived from the qualitative researcher's case familiarity; to conduct rigorous analysis by drawing widely from the qualitative methods toolkit; and to meet the increased research transparency demands. The enterprise gave rise to a cooperative, expert‐reliant technique for constructing new data as well as experimentation with an online Appendix (Shesterinina et al., Reference Shesterinina, Pollack and Arriola2019) and data accessibility and with openness towards and reflection on author positionality and judgment (Soedirgo & Glas, Reference Soedirgo and Glas2020).

Second, even with an explanatory focus, the study is not ad hoc and contributes to theory, largely by advancing the third‐wave IPE research program on ‘complex interdependence’.Footnote 13 One general takeaway is that theories that assume away external causes of phenomena internal to great regulatory powers are seriously flawed (Oatley, Reference Oatley2011; Newman & Posner, Reference Newman and Posner2018, pp. 119–155). In the first decades of the 21st century, even the US was not cut off from forces beyond its borders. Brussels’ regulation deeply affected Washington's. Another takeaway is the value of including temporal processes in theoretical models (Farrell & Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2014; Fioretos, Reference Fioretos2011; Posner, Reference Posner2010). The main causal mechanism featured in this study is an international feedback that arose from internal US and EU developments (Farrell & Newman, Reference Farrell and Newman2019a, Reference Farrell and Newman2019b; Newman & Posner, Reference Newman and Posner2018). We hypothesize (with an eye to future research), moreover, that the later‐stage rise of institutionalized cooperation (as another source of stringency lock‐in) may, in fact, be a subsequent effect of the same causal process. Do the costs of having two distinct sets of rigorous rules, buoyed by parity in border‐policing capacities, eventually and paradoxically pressure the two jurisdictions to make mutual adjustments and to agree to deference arrangements? Our theoretical framework thus speaks to the benefits of embracing theoretical holism and the complexities of the global political economy and to the advantages of temporal analysis.

Lastly, in terms of this study's real‐world relevance, much remains unknown as the distribution and evolution of market power continue to undergo change. In finance, there are questions about the diminished post‐Brexit EU and the effects of the United Kingdom's emergence as an independent global financial actor in its own right. Moreover, China has signalled its intention to be an international rule‐maker, and the Russia–Ukraine war prompts questions about whether Beijing will speed up financial internationalization (or not). Would the presence of three or four, instead of two, alter the prospects for sustained stringent financial regulation? Beyond finance, the war renews questions about the viability of economic interdependence between democracies and autocracies.

Nonetheless, even with these and other uncertainties, this study may still hold insights about future possibilities for creating and protecting international financial system stability. Based on the dozen years when there were two deeply tied regulatory giants, the wherewithal to penalize the firms of the other spawned incentives and dynamics that preserved stringent rules. Following an uncoordinated build‐up of capacities, the two jurisdictions managed to constrain capital mobility and regulatory arbitrage. Evidence even suggests that the development catalyzed other jurisdictions to stick with similarly rigorous rules (Jones & Zeitz, Reference Jones and Zeitz2019). Is there reason to be optimistic about other sectors with similar configurations of border‐policing capacities? Perhaps under the right conditions, power can be at the service of purpose.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this article were presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association in September 2020, the Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association in April 2021, the 17th European Union Studies Association Biennial Conference in May 2022, the Conference of the Standing Group on the European Union of the European Consortium for Political Research in June 2022 and the Conference of the Council for European Studies in June 2022. We thank the discussants, fellow panelists and audiences for their comments and reactions. We are particularly grateful to Mark Cassell, Orfeo Fioretos, Erik Jones, Scott James, Manuela Moschella, Abraham Newman, Aneta Spendzharova, Amy Verdun, Nicolas Véron, Gillian Weiss and Jonathan Zeitlin. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and the journal editors for their thoughtful and constructive comments, Vito Ruggiero for invaluable research assistance and Dessislava Kirilova for expert guidance through the steps at the Qualitative Data Repository where the datasets for this article are stored. Finally, since this collaboration began during his 2018–2019 sabbatical, Elliot Posner acknowledges the generous support of IMÉRA Institute for Advanced Study at the Aix‐Marseille Université and Case Western Reserve University.

Data Availability Statement

All replication materials are available here https://doi.org/10.5064/F6QR17WM in the Qualitative Data Repository.

[Correction added on 7th of August 2023, after first online publication: Data availability statement has been added in this version.]

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: