1.1 Introduction

Any study of the experiences of women in the contemporary MENA region has to consider both the volatile history of this part of the world and the cultural characteristics of the countries in which the Emiratis, Omanis and Saudis who are featured in this book live and work. This chapter begins with a brief description of a period of time that has often been called the ‘Golden Age’ of Arabic civilisation during the Abbasid Caliphate of 762–1258 CE. This provides a bleak contrast with the economic, political and social challenges that confront the entire MENA region today. Section 1.3 describes these in some detail and also considers the impact of the 2011 Arab Spring on the MENA region and the emergence of fundamentalist Islamic groups such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS). Drawing on recent reports by the United Nations, the World Bank, the World Economic Forum and the world’s leading consulting companies, it also examines the economic, political and social status of women in countries in the MENA region. Section 1.4 explores the practical implications of this book for public- and private-sector organisations in the region and describes the economic and business case for improving the economic participation of women in regional labour markets – an issue we return to in greater depth in Chapter 8. It also outlines the broader potential implications of this transformation for the medium- to long-term development of all the national economies of this deeply troubled part of the world.

1.2 The MENA Region in the Past

We Arabs used to be at the centre of world culture. We invented mathematics. We were the scholars and scientists. The world used to turn to Arabia for its knowledge and books. And now look at us. We are the poorest people in the world, backwards, tribal and illiterate. Why? Because we have let ourselves be led around like dogs by our leaders, by thieves. Now, with our revolution, we are saying no. We are saying we are dignified. We are proud.

Today, the MENA region consists of nineteen countries, stretching from Morocco on the Atlantic coast of Africa to the borders of India and Pakistan in the East. In 2016, it was home to approximately 350 million people (more than three times the population in 1970) and contained about 20 per cent of the global Islamic population of approximately one billion people. Within this region we find Arabia which was, between the eighth and thirteenth centuries, part of one of the most extensive and advanced civilisations in the world: the Abbasid Caliphate. In 1000 CE, the cities of Baghdad, Cairo and Damascus were major hubs of free trade and international commerce, open markets, technological and industrial innovation and major centres of intellectual enquiry and learning. This region was, by the standards of the time, home to one of the most affluent civilisations in the world, the other being China (Morris, Reference Morris2011: 331–384). In the words of one scholar of Islamic science:

Proximity to Indian trade routes, a vibrant multi-ethnic culture and safe distance from the traditional military dangers posed by the Byzantine Greeks helped establish Baghdad for centuries as the world’s most prosperous nexus of trade, commerce, and intellectual and scientific exchange … Urban merchants and traders generated the surpluses of cash and leisure time that made the scholarly life possible in the first place. In the division of labour that characterised Arab city life, there was ample room for the thinker, the teacher and the writer

What is arguably the oldest multi-faculty higher education institution in the world was founded in the ninth century at Fez in Morocco, and between the ninth and thirteenth centuries the Bayt al-Hikma in Baghdad (or, as some Islamic scholars call it, the Medinat al-Hikma – ‘City of Wisdom’) was not only the epicentre of scholarship and research in the Muslim world; it was the leading centre of learning for the entire occidental world at this time. It was supported by generous financial endowments from a succession of Abbasid caliphs and ‘it came to comprise a translation bureau, a library and book repository, and an academy of scholars and intellectuals from across the empire’ (Lyons, Reference Lyons2010: 63). Here and at other scholarly centres and schools, such as those at the Al Azhar mosque complex in Cairo and at Al Andalus in Spain, many theoretical advances and practical innovations were made in architecture, agriculture and horticulture, algebra, anatomy and medicine, astronomy, cartography, ceramics and glass making, chemistry, economic theory, engineering, mathematics, numerology and optics (including the first known camera obscura, later used by Roger Bacon to study solar eclipses) and in psychology and psychotherapy, by the scholars who worked together in what was, by the standards of that time, a generally tolerant, liberal, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic environment.

While Europeans struggled until at least the twelfth century with the most rudimentary mathematical and philosophical concepts, the Abbasid caliphs who reigned from the eighth to the thirteenth century promoted and encouraged an open, enquiring and more rationalistic version of Islam. The ideas of earlier Persian, Roman, Egyptian and Hindu scholars (particularly their numerical system which we know today as ‘Arabic’ numerals), as well as the works of Aristotle, Archimedes, Euclid, Galen, Hippocrates, Plato, Ptolemy, Pythagoras and many others were retrieved, recorded, studied and further developed by the Islamic and Nestorian Christian ulama 1 who worked at the Bayt al-Hikma, while Europe endured the Dark Ages following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the fifth century CE. Muslim scientists, such as Avicenna and Averroes, were mapping the heavens and wondering about the origins of the cosmos, while their European contemporaries could only gaze at the complex movements of the solar system and the stars with little more than baffled bewilderment. More than 100 of the most visible stars in the night sky owe their names to astronomers from this time.

Astronomy is just one example of the enormous debt that Europe owed to Islamic proto-science. Many scientific and mathematical words that we now take for granted can be traced back to this time, including alchemy, algebra, alcohol, alkali, azimuth, elixir, sine, zenith and zero (al-Khalili, Reference al-Khalili2012: 241). The dissemination of this knowledge was increased exponentially by using a revolutionary new writing material called paper – invented by the Chinese between the second and third centuries BCE. Without the dissemination of the accumulated knowledge of the Bayt al-Hikma, as several scholars have recently demonstrated, the later innovative work of luminaries such as Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler or Galileo might never have happened, and there may have been no European Renaissance (‘rebirth’) during the sixteenth century and, later, an industrial revolution in England in the mid- to late eighteenth century (al-Khalili, Reference al-Khalili2012; Lyons, Reference Lyons2010; Masood, Reference Masood2009; Saliba, Reference Saliba2007).

The destruction of Baghdad and the Bayt al-Hikma in 1258 by the Mongol warlord Hulagu Khan marked the end of what is now widely recognised as the Golden Period of the Arabic civilisation and Islamic proto-science, and as increasingly conservative and otherworldly rulers and imams came to dominate the different regions of the Caliphate, support and sponsorship for scholarly and scientific pursuits declined markedly during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. However, the knowledge generated at the Bayt al-Hikma and other centres of learning in the Caliphate would soon find fertile ground in which to germinate and grow in Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, particularly after the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (Diner, Reference Diner2009: 71–95). The eventual triumph of the more strict and doctrinaire caliphs that superseded the Abbasid rulers of the thirteenth century meant that very few rulers in the MENA region re-embraced the proto-science their predecessors had pioneered and simply ignored many of the new technologies generated by the first industrial revolution in Europe during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries until it was too late (al-Hassan, Reference al-Hassan1996; al-Khalili, Reference al-Khalili2012). Furthermore, even in the extensive and long-lasting Ottoman Empire, its rulers failed to understand the economic and military threat posed by the new European powers that began to emerge during the eighteenth century until it had become far too late to counter their global military and economic expansion during the nineteenth century; as a result, the Ottoman Empire was ‘gradually overtaken by the dynamism of Europe’ (Rogan, Reference Rogan2015: xviii).

Hence, when Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, ‘he might almost have come from Mars’, so great was the economic and technological gulf between the emerging European powers and the countries of the MENA region; and ‘by the time that Sadik Rifat Pasha, the Ottoman ambassador to Vienna warned that the Europeans were flourishing thanks to a combination of science, technology and, “the necessary rights of freedom”, it was already too late’ (Ferris, Reference Ferris2010: 268). By 1920, all of the MENA region was either directly controlled or encircled by European imperial powers, and by the middle of the twentieth century, the discovery of oil in several locations ensured that many of those would be drawn into the political and military affairs of the region from that time to the present day (Diner, Reference Diner2009; Saliba, Reference Saliba2007).2 And, as Ferris has observed, those states that possessed oil (and gas) wealth were transformed from small fishing, herding and trading communities ‘into economically more vertical societies where the few who controlled the oil became rich and the rest stayed poor. Such inequities were offensive to Islam – which, like Christianity had originated a religion centred on the poor and devoted to social justice – but the attempts of Muslim leaders to redress them by resorting to wealth distribution through state socialism failed’ (Ferris, Reference Ferris2010: 269).

It would be fairer to say that this strategy has ‘largely failed’, because while it has led to rapid GDP growth, extensive infrastructure development and some economic diversification over the past thirty years, we will see in subsequent chapters that it is no longer a sustainable medium- to long-term strategy for any country in the Gulf States and the broader MENA region. We return to look at the lessons that can be learned from this ‘Golden Age’ of Arabic trade, culture and learning for the future of the region and the prospects for the millions of women who live there at the end of Chapter 9 and in the Postscript to the book.

1.3 The Economic, Political and Social Challenges Facing the MENA Region Today

The problem of modern Islam, in a nutshell, is that we are totally dependent on the West – for our dishwashers, our clothes, our cars, our education, everything. It is humiliating and every Muslim feels it. We were once the most sophisticated civilisation in the world. Now we are backward. We can’t even fight our wars without using our enemies’ weapons.

Making the leap from the thirteenth century to the second decade of the current century, we find that the MENA region, overall, lags behind most of the rest of the world on many key metrics and indicators of economic, political, social, scientific and educational development, even though many countries in this region have benefitted greatly from the wealth derived from their oil and gas industries over the past half century. These metrics and indicators include:

The low average per-capita income growth for the citizens of most countries in the MENA region over the past five decades, combined with a marked concentration of wealth among the ruling political elites of all countries in the region (The Economist, 2016e, 2014a and 2013; United Nations, 2015a, 2009, 2005 and 2004).

Endemic national, civil, ethnic and religious conflicts in every Muslim country in the MENA region. In 2016, the most notable examples of this were Iraq, Syria, Libya and Yemen, with growing civil unrest in several other countries such as Lebanon, Oman and even the KSA. Some 10 million people have been rendered homeless by these conflicts and more than 230,000 have been killed (including at least 30,000 children). About two million people have fled these conflict zones, and this, in turn, has led to a major refugee crisis in several North African countries and the European Union.

The prevalence of autocratic governments and non-democratic political systems across the entire MENA region. Countries in this region are also characterised by the lowest political freedom scores of any region of the world, as measured by the existence of participative and open political processes, accountable and equitable legal systems, freedom of speech and expression of thought, independent news media and unrestricted Internet access, and established political rights and freedoms such as the right to vote in transparent democratic elections and the freedom to take part in civil activism (Freedom House, 2016b; Human Rights Watch, 2015; United Nations, 2009, 2005 and 2004).

A notable lack of legal accountability, transparency and governance standards among the ruling political and business elites of many countries in the MENA region, as well as high levels of corruption and fraud. For example, of the 19 countries in the MENA region just 2 were ranked in the top 50 ‘least corrupt’ countries in the world in 2016 (Bahrain and the UAE), and 84 per cent were ranked in the top 50 of 175 countries in Transparency International’s 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index. Only six countries in the region had scores above 50/100; anything below this score and corruption is deemed to be ‘a serious problem’ (Transparency International, 2016).

Even the most stable countries in the region – primarily those that have benefitted greatly from an abundance of oil and gas, such as the UAE, Oman, the KSA, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain – have not yet built economies or stable political and civic institutions that would survive for long if their natural resource pipelines were switched off tomorrow. It is true, however, that the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have all made efforts to use their resource wealth to begin the long process of building more diversified, knowledge-based economies, and a handful of their largest companies are internationally competitive (Hertog, Reference Hertog2010a; Hvidt, Reference Hvidt2013).

Other indicators of regional under-development include the comparatively low amount of capital spent on research and development (R&D) in both basic and applied scientific research in the region. In 2013, the fifty-seven member countries of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference invested just 0.81 per cent of their combined annual GDPs on R&D. The Muslim world as a whole spends less than 0.5 per cent of their cumulative GDP on R&D, compared to an average of about 5 per cent in countries affiliated with the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). In the MENA region, Israel is the clear leader, spending about 4.4 per cent of its GDP on R&D and invests a significant proportion of this in research at its national universities. In addition, countries in the MENA region have fewer than 10 scientists, engineers and technicians per 1,000 people, compared to an average of 40 in emerging economies and 140 per 1,000 in the industrialised world (The Economist, 2014a and 2014b; al-Khalili, Reference al-Khalili2012: 283). There are a few signs of increased spending on scientific research in a few countries, albeit from a very low base. Qatar, for example, increased annual funding on R&D from 0.8 per cent of GDP to 2.8 per cent in the early 2010s. Turkey, which is not part of the MENA region but is a predominantly Islamic country, increased its funding by an average of 10 per cent a year from 2005 to 2010, and its output of scientific papers rose from 5,000 to 22,000 a year between 2002 and 2009. Moreover, countries in the MENA region register very few scientific or industrial patents – approximately one per million of their population each year. In 2013, the ratio was 77.6 per million in Canada and 123.2 per million in Singapore (The Economist, 2014a and 2013b).

The 2005 United Nations Arab Human Development Report (AHDR) had noted that the entire MENA region imported fewer scientific and academic books than the United Kingdom alone imported in 2004, and Cambridge University Press published more academic books that year than the entire MENA region (United Nations 2005: 34). In 2012, Harvard University alone produced more scientific papers than the combined output of all the universities in seventeen Muslim countries in this region (The Economist, 2013b); a situation that was largely unchanged from both the early 2000s (The Economist, 2002) and the mid-1990s (Segal, Reference Segal1996). Between them, universities in the MENA region – excluding Israel – contribute less than 1 per cent of the world’s published scientific papers (The Economist, 2014a: 9). Furthermore, while the MENA region has produced just 3 Nobel Laureates in Science since 1901 there have been 193 Jewish Nobel Laureates (out of a total of 855 honourees) and a single Cambridge College (Trinity) has produced 32 Nobel Laureates during this period of time (Jewish Virtual Library, 2015).

It is also evident that there are very few elite, world-class universities in the MENA region. There were, for example, only five universities in the entire MENA region ranked in the Times Higher Education and Webometrics top 500 global universities in 2016 and 2015, and four of those were in Israel (Times Higher Education, 2016 and 2015; Webometrics, 2015). An examination of the distribution of world-class universities by country of origin reveals a similar picture: the United States has 142 universities ranked in the top 500, followed by China and Germany with 40 each, the United Kingdom with 34, Spain with 27, Canada with 24 and Australia with 16. The nineteen countries of the MENA region, excluding Israel, had just one university ranked in the global top 500 in 2016 and 2015. There are more than 1,000 universities in the MENA region, with the highest-ranked ones being the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv University, and both are in the Times Higher Education and Webometrics top 300. Israel is also the highest-ranked regional nation-state, with four universities ranked in the top 500. Saudi Arabia, with approximately fifty accredited universities and colleges of further education, was the only Arabic country that had a university ranked in either the Times Higher Education or the Webometrics top 500 global universities in 2016 and 2015, the King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (Times Higher Education, 2016 and 2015; Webometrics, 2015). However, with this single exception, the higher education (HE) sector of the predominantly Muslim countries of the MENA region is notable primarily for the absence of world-class universities

In addition to these metrics and indicators, the low economic, political, educational and legal status (EPELS) of women in MENA countries has been extensively documented. Globally, only Sub-Saharan Africa countries have a lower EPELS score than Middle Eastern countries on measures of the participation of women in political, economic, professional and social activities and their legal and social rights. These gaps have been and remain particularly acute for millions of uneducated women in the region (Kelly and Breslin, Reference Kelly and Breslin2014; United Nations, 2016 and 2015a: 107–116; United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, 2014a; World Economic Forum, 2015b). In the political domain, for example, even in those countries that have held political ‘elections’ of some description over the past twenty years, less than 10 per cent of those elected were women. ‘Women in power’, the United Nations AHDR noted in 2005, ‘are often selected from the ranks of the elite or appointed from the ruling party as window-dressing for the ruling regime.’ And efforts to address this deficit ‘have often been limited to cosmetic empowerment in the sense of enabling notable women to occupy leadership positions in the structure of the existing regime without extending empowerment to the broad base of women; a process that automatically entails the empowerment of all citizens’ (United Nations, 2005: 9 and 51). This report also noted that:

The traditional view that the man is the breadwinner blocks the employment of women and contributes to an increase in women’s employment relative to men. Women thus encounter significant obstacles outside family life that reduce their potential. Most limiting of these are the terms and conditions of work: women do not enjoy equality of opportunity with men in job opportunities, conditions, or wages; yet alone in promotion to decision-making positions

While there are considerable variations in the EPELS of women in individual countries in the MENA region, the average rate of participation by women in paid employment is lower than any other region of the world, including Sub-Saharan Africa, and the overall gender gap between the participation rates of men and women in the labour markets of this region is very wide when compared to almost every other part of the world. For example, the participation rate of women in the 19 national labour markets of the MENA region in 2005 was 33 per cent, compared to an OECD average of 55.6 per cent and more than 70 per cent in Nordic countries such as Norway and Sweden (United Nations, 2005: 8 and 88). This, as we will see in later chapters, has not changed significantly in most countries in the MENA region over the last decade (United Nations, 2015a: 107–116; World Economic Forum, 2015b).

One of the small number of studies that has looked at the attitudes of men towards women’s right to work in Islamic societies found what can only be described as ‘mixed’ viewpoints about this (Telhami, Reference Telhami2013). This study summarised the findings of national opinion polls from Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, as well as polls of those of Middle Eastern origin resident in the United States; and Israeli Arab and Palestinian opinion polls from 2003–2012. It found that one fifth of Arabs believed that women should ‘never have the right to work outside the house’, whereas around one third believed that ‘women should always have the right to work outside the home.’ However, the largest group felt that ‘women should have the right to work only when economically needed.’ Between 40 and 50 per cent of respondents in five countries and, perhaps surprisingly, 70 per cent in the UAE agreed with this statement (Telhami, Reference Telhami2013: 167 and 168). A survey of 1,450 women and men in Egypt, Morocco and the KSA in 2012 revealed that 80 per cent of men believed that women should be limited to housekeeping and childcare roles, rising to 97 per cent in the KSA. However, suggesting something of a generational shift in attitudes, this fell to 59 per cent among men aged 15–24 and to 22 per cent among the young women in this group (Shediac et al, Reference Shediac, Bohsali and Samman2012: 27). In Chapters 2 through 7 we will look at the foundations of these beliefs and the cultural, attitudinal and structural barriers that continue to inhibit the full participation of women in the national labour markets of the Gulf States and the broader MENA region.

Female enrolment in education, particularly in the Gulf States, has increased exponentially over the past twenty years, and they generally perform better than males do at the secondary and tertiary levels. However, if they are allowed by their fathers or husbands to attend university, they are still concentrated in fields such as education, literature, languages, human resource management and the social sciences. Very few Arab women study for degrees in computer science and information technology (CSIT) and women in the MENA region are noticeably under-represented in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) professions (Forster and al-Marzouqi, Reference Forster and al-Marzouqi2011; Kelly and Breslin, Reference Kelly and Breslin2014; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2014). Many young Arab women continue to avoid educational, career or entrepreneurial opportunities in CSIT, and most of the handful of Arab women who first graduated with science doctorates in the late 1990s and early 2000s chose to work at Western universities (Kandaswamy, Reference Kandaswamy2003). Women in the MENA region are also much more likely to work in the public sector than in wealth-generating private-sector businesses, and few are entrepreneurs and small business owners, and the reasons for these structural imbalances are explained in Chapters 2 through 7 (United Nations, 2004: 80–84 and 108; World Economic Forum, 2015b).

Last, but not least, is the well-documented dearth of women’s legal rights in the MENA region, including the restrictions imposed by the ‘male guardianship’ rules in most MENA countries, the absence of equal legal rights in both the public and private domain and a lack of protection against violence by men. The 2005 UN AHDR noted that ‘the forms of violence practiced against women confirm that Arab legislators and government, together with Arab social movements, face a large task in achieving security and development in its comprehensive sense. The mere discussion of violence against women arouses strong resistance in some Arab countries’ (United Nations, 2005: 10). In fact, as several female Islamic scholars have noted, ‘strong resistance’ to such discussions occurs in all Arab countries particularly in those that have fallen prey to the most virulent forms of Islamic ‘purification’ in, for example, Afghanistan in the 1990s, Sudan in the 1990s and 2000s or the ISIS-controlled areas of Iraq and Syria during the 2000s and 2010s. Such forms of violence include ‘honour’ killings, forced female circumcisions, acid attacks on young girls who attend school and the stoning of alleged ‘adulterers’ and women who have been the victims of rape, domestic violence and so forth (Ali, Reference Ali2015; Reference Ali2010 and Reference Ali2007; Bennoune, Reference Bennoune2013; Eltahawy, 2005). This is not to imply that acts of violence against women, either in the domestic sphere or as part of more systemic atrocities committed against women during civil, sectarian or national wars (e.g. gang rapes, forced marriages and so forth), are unique to the MENA region. Such abuses have been perpetrated by men against women in every culture throughout human history.

The popular uprisings in Morocco, Libya, Iran, Tunisia, Bahrain, Egypt and Syria during the Arab Spring were clear evidence that these systemic and endemic economic, political and social problems (and, of course, the relatively low status of women) had not been addressed or resolved by the autocratic governments of these countries. As one Arabic commentator has observed:

The uprisings were in the first place about karamah [dignity] and about ending a pervasive sense of humiliation. The dignity they hoped to restore was not simply in the relationship between rulers and ruled, but also in their relationship between their nations and the outside world … Fundamentally, most Arab citizens across the region were hungry for freedom, economic opportunity, dignity and individual rights and liberty

Many women became involved in these political protests, taking to the streets, being arrested and sometimes being beaten up or suffering humiliating sexual abuse by the police and army (as occurred in Egypt with the military’s disgraceful ‘virginity tests’ in 2013 and in Sudan during 2011) (Khalil, Reference Khalil2011). These protests provided them with an opportunity to demand greater legal, economic, social and human rights and to also show their opposition to the growing tide of Islamic fundamentalism in the MENA region (Bennoune, Reference Bennoune2013; Cole, Reference Cole2014: 271–272). The bravery and resilience of these women were recognised, at least symbolically, when Tawakkol Karman, a Yemeni political activist, was awarded one of three 2011 Nobel Peace Prizes and the Pakistani teenager Malala Yousafzai received the 2014 International Children’s Peace Prize. Predictably, both were quickly denounced as ‘pawns of the Great Satan’ and ‘whores’ on several fundamentalist Islamic websites (Muhanna-Matar, Reference Muhanna-Matar2014). We will see in Chapters 2 through 7 that similar hopes and aspirations were expressed by many of the women and men who are featured in this study; above all else, their desire for karamah.2

The wave of protests in the region in the late 2000s and early 2010s did lead to the overthrow of one set of dictators in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen and to growing demands for fundamental reforms in several other countries such as Iraq, Bahrain, the UAE, Oman and the KSA. However, despite the hopes of many people in the MENA region and elsewhere, the Arab Spring had stalled by the end of 2013, and there were few signs that a systemic process of political and social change was likely to occur. In a review of the situation in the MENA region in early 2016, The Economist concluded that:

Arabs have rarely lived in bleaker times. The hopes raised by the Arab Spring – for more inclusive politics and more responsive government, for more jobs and fewer presidential cronies carving up the economy – have been dashed. The wells of despair are overflowing … Rent-seeking remains rampant and standards in both public education and the administration of justice are still dismal. Economic growth is slow or stagnant; the hand of the security forces weigh heavier than ever, more or less everywhere. Sectarian divisions and class rivalries have deepened, providing fertile ground for radicals who posit their own brutal visions of Islamic Utopia as the only solution

Moreover, it soon became clear that these protests and uprisings had not led to greater freedoms and rights for women in the region. In fact, in those MENA countries characterised by civil, sectarian, tribal and religious conflicts, the situation for women became noticeably worse during 2012–2016. This prompted The Economist to ask, in a lead editorial article in July 2014, ‘Why Arab countries have so miserably failed to create democracy, happiness or (aside from the windfall of oil) wealth for its 350 million people is one of the great questions of our time. What makes Arab society so susceptible to vile regimes and fanatics bent on destroying them and their perceived allies in the West?’ (The Economist, 2014a: 9). While detailed answers to that question are beyond the scope of this book and this topic has been addressed by many commentators in recent times, a summary of some of the main reasons that have been presented to account for the economic, political and social problems facing the MENA region is necessary. This is because these define the sociological contexts in which the women and men who are the primary focus of this study live and help us better understand how they make sense of their societies and their lives in Chapters 2 through 7. Although there are considerable variations given to their relative significance and importance, all commentators on the MENA region claim that the endemic instability of the region today has a number of interrelated causes. These include:

The long-term residual effects of the arbitrary ‘carve-up’ of the MENA region and the Ottoman Empire as a result of the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916. The national frontiers created at this time did not reflect the ethnic, cultural and religious make-up of this region; merely the strategic whims of the imperialist powers that created these. This coincided with the installation in power of privileged ‘Westernised’ ruling elites by European colonial powers after World War I in most MENA countries, which also happened in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia after World War II (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012; Rogan, Reference Rogan2015).

The creation of a Jewish state in Palestine in 1948 and the largely unconditional support given to this country by the United States and many of its allies since, combined with regular military incursions by the USA in the MENA region in furtherance of its global military, strategic and energy interests and its support of a succession of autocratic and repressive regimes in the region over the last seven decades. It is probable that the invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003, engineered by Bush, Cheney, Wolfowitz, Abrams, Libby and the former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, will be judged by future historians as one of the most poorly thought-out, ineptly executed and expensive debacles in military history (Bugliosi, Reference Bugliosi2008).

A notable lack of legal accountability, transparency and governance standards among the ruling political and business elites of many countries in the MENA region, as well as high levels of corruption and fraud. For example, of the 19 countries in the MENA region just 2 were ranked in the top 50 ‘least corrupt’ countries in the world in 2016 (Bahrain and the UAE), and 84 per cent were ranked in the top 50 of 175 countries in Transparency International’s 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index. Only six countries in the region had scores above 50/100; anything below this score and corruption is deemed to be ‘a serious problem’ (Transparency International, 2016).

The deeply tribal and patriarchal cultures of the entire region, in which deference and loyalty to one’s dynastic elders, family, clan and tribe (sabiyya qabaliyya), and to local concerns and personal connections (wasta), are still paramount. These loyalties may often be at odds with national economic, political and social interests (Diner, Reference Diner2009).

The significant economic and social pressures generated by the rapid growth of the populations of all MENA countries during the 1990s and 2000s and very high average youth unemployment levels of between 25 and 40 per cent (and more than 50 per cent, on average, for young women in the region)(International Labour Organisation, 2015; United Nations, 2009, 2005 and 2004).

The failure of almost all countries in the MENA region to develop the societal and institutional prerequisites for stable nation-states including representative and non-corrupt political institutions and administrative systems, transparent and inclusive electoral processes, independent legal systems, free and independent news and media organisations, protection for religious and cultural minorities, independent, high-quality schools and universities teaching modern non-Islamic curricula, autonomous civic associations and trade unions and the unwillingness of any country in the MENA region to separate ‘mosque and state’

Almost all Western and some Arabic commentators believe that the pervasive influence of Islam (or, to be more accurate, how this is interpreted and practiced by many Muslims) is one of the principal reasons this region is still characterised by so many endemic and deep-seated problems. The distinction that exists in many non-Islamic countries between religion and the state has no provenance in Islamic theology and law, and so many adherents believe not only that spiritual and secular authority are inseparable but that the latter must – in all circumstances and at all times – be subservient to the former. This means that there can be no separation of religion from the state (fasl al-dinn wa al-dawla), and in every Arabic country this means Islam (Ali, Reference Ali2015; Zakaria, Reference Zakaria2004: 119–160). As Ali has observed:

The leading Muslim clerics have come to the consensus that Islam is more than a mere religion, but rather the one and only comprehensive system that embraces, explains, integrates, and dictates all aspects of human life: personal, cultural, political, as well as religious. In short, Islam handles everything. Any cleric who advocates the separation of mosque and state is instantly anathematized. He is declared a heretic and his work is removed from the bookshelves. This is what makes Islam fundamentally different from other twenty first-century monotheistic religions … It is not simply that the boundaries between religion and politics are porous. There scarcely are any boundaries … In countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran, or within mounting insurgent movements such as Islamic State and Boko Haram, the boundaries between religion and politics do not exist at all

It is this largely unquestioned religious hegemony that has prevented the development of modern secular political and civic institutions in almost all MENA countries in contrast to, for example, the protracted and difficult process of political change and secularisation experienced by Europe and North America during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. All countries in those regions witnessed, among other significant societal changes, the gradual separation of church and state, the dismantling of the ‘divine right’ of monarchs and the power of the landed aristocracy, the industrial and scientific revolutions, the spread of democracy, universal suffrage and greater governmental accountability, the gradual acceptance of the principle of religious diversity and tolerance, the establishment of the right of habeas corpus, protection of intellectual freedom and expression of ideas and, more recently, the principal of legal equality for women, ethnic minority and gay and lesbian groups. Furthermore, as many writers have demonstrated, none of these societal, cultural and social transformations would have been possible unless the hegemony of institutionalised religion in Europe and North America had been progressively challenged and then dismantled during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In contrast, the predominantly Islamic countries of the MENA region have barely started to even discuss these existential political, cultural and social issues (Ali, Reference Ali2015; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2006; Diner, Reference Diner2009; Morris, Reference Morris2011; Stark, Reference Stark2014).

There is also little disagreement among commentators on the MENA region that an increasing number of alienated younger Muslims are advocating more fanatical interpretations of Islam. This trend was first identified during the early 2000s (Burgot, Reference Burgot2003; Fadl, Reference Fadl2005; Kepel, Reference Kepel2004), and a more recent report by the Tony Blair Faith Foundation has described the very close relationship between Islamic beliefs and jihadist ideology (Badawy et al, Reference Badawy, Comerford and Welby2015). The endemic instability of the MENA region has led to the emergence of revolutionary Sunni and Shiite jihadist groups, such as the militant ISIS (also known as ISIL – the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant – and Daesh). In early 2014, this group declared that its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was the Caliph of all Muslims and that its intention was to wage a holy war on all ‘non-believers’ (which, of course, included all Muslims who did not accept his legitimacy). Its long-term goal is to destroy the al-Saud dynasty in the KSA and create a modern-day Caliphate that will – they believe – eventually encompass a region stretching from Spain in the West, all of the MENA region, two thirds of India, the western region of China and all of Malaysia and Indonesia (The Economist, 2014a and b).3 Concurrently, the bloody suppression by President Assad of Syria (a member of the minority Sunni Alawite sect), a similar crackdown by Nuri Al-Maliki on Sunnis in Iraq, the abuses perpetrated against members of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt during 2013–2015 and the repression of Shia Muslims in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain during 2012–2016 were all symptomatic of escalating national, ethnic, religious and tribal tensions in the MENA region during the present decade (The Economist, 2016e, l and m).

These continuing and apparently irreconcilable conflicts, combined with the absence of what can broadly be described as ‘liberal’, strong and independent political and civil institutions in all MENA countries, has meant that very few of them have been able to build modern, diversified, internationally competitive economies. Even the most stable countries in the region – primarily those that have benefitted greatly from bonanzas of oil and gas, such as Bahrain, the KSA, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and the UAE – have not yet built economies or stable political and civic institutions that would survive for more than a few months if their oil and gas pipelines were switched off tomorrow. While all of these countries have made some efforts to diversify their economies, two reports on the economic and political future of the MENA region have noted that:

Without deep economic change, the MENA region will be unable to realize the benefits that come from having a young, energetic and aspiring population. The current demographic bulge (in which more than half the population is younger than 25) means that the Middle-East will need to create millions of jobs just to stand still … Prosperity depends on having a reinforcing virtuous circle in which economic growth, robust and relevant education and creative opportunities come together

The effects of the recent global economic crisis were all-pervasive and have demonstrated that no economy is safe from destabilising external events. Resource-dependent countries with their narrow base of economic activity, are particularly vulnerable … Not only must countries’ GDP be balanced among sectors, but key elements of its economy must be varied, flexible, and readily applicable to a variety of economic opportunities, and areas of over-concentration must be continually identified and mitigated. Policymakers should work to achieve greater economic diversification, in order to reduce the impact of external events and foster more robust, resilient growth over the long-term … For resource rich developing nations, sector diversification is still the first priority; a failure to achieve this first step in diversification will undermine these countries’ strong growth potential

This is sensible advice, but there are three reasons all countries in the MENA region will struggle to build stable and diversified economies in the future, including the three that are the primary focus of this study. First, they are all characterised either by widespread economic, political and social instability or – at best – a repressive stability, maintained and supported by oil and gas wealth. Second, they are not what are described by political economists as ‘inclusive states’, where the use and distribution of the resources and state revenues of each country are subject to independent scrutiny and accountability and are, at least nominally, ‘owned’ by the people through their elected representatives. Rather, they are predominantly ‘extractive’, ‘rentier’ or ‘clientilist’ societies, ruled over by intransigent and often repressive oligarchies. Third, they still exclude many of their female citizens and ethnic/religious minorities from active and equal participation in their political systems and do not allow these groups equal access to civic society, to their labour markets and to all occupations and professions, particularly at the most senior levels (Beblawi, Reference Beblawi, Beblawi and Giacomo1990; Diner, Reference Diner2009: 11–37; Hertog, Reference Hertog2010a: 9–10, 37–38 and 264–275; Wenar, Reference Wenar2016). As The Economist has remarked:

All too many of the Arab world’s 350 million people are caught between rotten governments and often violent oppositions. Its would-be-reformers have retreated to the conditions described by the late Syrian playwright Saadallah Wannous as ‘condemned to hope’, trapped either in stagnant repression or cycles of strife they are unable to make progress. This stasis has heightened long-standing concerns that Arab countries are in some fundamental way unsuited to the modern world, concerns which have spawned a gaggle of grand theories. But, it is a particular pattern of twentieth-century modernisation, rather than its absence, that lies behind the region’s political failure … It takes openness for society to progress. Closed politics may be tempered by an openness to ideas and to an open economy, as in China. Open politics can make up for poverty and a paucity of human resources too. But to have closed politics and closed minds together is a recipe for disaster; for proof, consider the current fate of all the Arab states

This report and other recent studies that have documented the progress being made towards economic diversification during the 2010s indicate that all countries in the MENA region are confronted with several major challenges. These include the need to develop more open regional markets to increase trade – while protecting national sovereignty, balancing internal political stability with the economic openness and institutional accountability required to build internationally competitive ‘post-oil’ national economies and reducing the economic distortions caused by lavish government spending on subsidies for energy, food, education, healthcare and so forth. In 2014, these amounted to approximately $150 billion or 12.8 per cent of the GCC’s total GDP according to The Economist (2014b: 21).4 Other challenges include coping with the privatisation of subsidised and protected nationalised industries, creating inclusive economies that benefit all citizens – not just the region’s elites – improving educational provision at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels, building their middle-classes and encouraging more women into their labour markets (Hvidt, Reference Hvidt2013). As one study has noted, ‘by providing policy stability governments can unleash the region’s considerable human promise: its increasingly educated and ambitious youth, its budding middle-class, and its aspiring women’ ( Shediac et al: 1). However, despite some improvements in their fortunes in recent times in some countries in the region, women are still the largest of the excluded, repressed and ‘condemned to hope’ groups in all MENA countries.

Globally, economically excluded women constitute a group that the consulting company Price Waterhouse Coopers has called ‘the Third Billion’, the first and second billion being the people of India and China (Aguirre et al, Reference Aguirre, Hoteit and Sabbagh2013). Citing data from the United Nations International Labour Organisation, Aguirre and her colleagues noted that:

Roughly 865 million women will be of working age (20–65) by 2020, yet will still lack the fundamental prerequisites to contribute to their national economies. Either they don’t have the necessary education and training to work, or – more frequently – they simply can’t work, owing to legal, familial, logistical and financial constraints. Of these 865 million people, 812 million live in emerging and developing nations. We call this group the Third Billion, because their economic impact will be just as significant as that of the billion plus populations of China and India. Yet the women of the Third Billion have been largely overlooked in many countries, and actively held back in others

An earlier report on women in the MENA region by another team of consultants at Booz&Co suggested that:

These women have the potential to become middle-class entrepreneurs, employees and consumers, but whose economic lives have previously been stunted, underleveraged or suppressed. As they enter the economic mainstream, they will have a huge impact around the world. This will probably affect the Middle-East dramatically, especially given its high levels of female education. For example, women in Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia constitute 67 per cent, 63 per cent, and 57 per cent respectively, of university graduates. Yet, in many countries, only a minority of women participate in the labour force, and comparatively few in the private sector. Bringing educated women and properly skilled youth into the economy will fuel growth, enterprise creation, and employment. Ultimately, that will provide the bedrock of stability that the MENA region has lacked: a stable middle-class

In the UAE, Oman and the KSA, the first generation of university-educated women began to enter the labour market in large numbers during the 2000s. Most young university-educated Emirati, Omani and Saudi women now pursue some kind of professional career, and a small but growing number are creating their own businesses. Consequently, their disposable wealth and economic power are growing. If, as other research data indicates, men are now lagging well behind women in educational attainment at both secondary and tertiary levels in these three countries, it is probable that they will lose out to well-educated, highly motivated and ambitious women in the future. For example, a study by the Dubai Women Centre found that 93 per cent of Emirati women described themselves as ‘very ambitious’, and 75 per cent aspired to senior positions in their chosen careers (Dubai Women Centre, 2008); and 52 per cent of Arabic women surveyed by the UAE recruitment and job search agency Bayt.com in 2010 believed that they were ‘much more ambitious than their male counterparts’ (Bayt.com, 2010). This shift in the self-belief and self-confidence of women has the potential – if actively supported and encouraged – to create a transformative growth engine that will assist in the lengthy process of creating stable and growing economies in the region. They also have the potential to have profound effects on the status and economic power of women in both the Gulf States and the broader MENA region in the future. Whether the countries of this region will embrace this opportunity is, of course, a question we will address in later chapters.

1.4 The Practical Implications of This Book

This book has three objectives. The first, as noted in the Preface, is to explain why the Islamic countries of the Gulf States and the broader MENA region cannot hope to build stable and internationally competitive economies in the future unless a much greater number of women are allowed to participate in their national economies. Second, to demonstrate that the medium- to long-term commercial success of many of the indigenous companies that operate in this region will depend on how well they deal with the issue of women’s participation in their workforces during the 2020s and beyond. Third, to present the compelling economic rationale and business case for encouraging a much higher level of participation by women in the labour markets of the MENA region in the future. Although we look at these propositions in greater depth in Chapters 8 and 9, a few examples of the general impact of equal opportunities on the bottom-line results of companies and national economic performance are presented here.

For example, the evidence compiled by the 1995 United States Federal Glass Ceiling Commission showed that the average annual return on investment of those companies that did not discriminate against women was more than double that of companies with poor records of hiring and promoting women (Federal Glass Ceiling Commission, 1995). In 2000, Alan Greenspan, the former United States Federal Reserve Chairman, argued that discrimination was bad for both business profitability and national economic performance, and he also suggested that ending discrimination against women and ethnic minorities had to be achieved immediately, not at some indeterminate point in the future: ‘By removing the non-economic distortions that arise as a result of discrimination, we can generate higher returns on both human and physical capital. Discrimination is against the interest of business. Yet, business people often practice it. In the end the costs are higher, less real output is produced and the nation’s wealth-accumulation is reduced’ (Greenspan, Reference Greenspan2000).

Several subsequent studies have indicated that parity between men and women is also likely to contribute to the bottom-line results of companies. For example, one study rated the performance of the Standard and Poor’s 500 companies on equal-opportunity factors, including the recruitment and promotion of women and minorities and the companies’ policies on discrimination. It found that companies rated in the bottom 100 for equal opportunities had an average of 8 per cent return on investment. Companies ranked in the top 100 had an average return of 18 per cent (Sussmuth-Dykerhoff et al, Reference Sussmuth-Dykerhoff, Wang and Chen2012). Furthermore, research on ‘high-performance’ companies and ‘employers of choice’ during the 1990s and 2000s showed that many of these had made early commitments to gender (and ethnic) diversity and to promoting women into senior management positions. These were and are among the most visionary, successful, resilient, adaptable and profitable companies in the world (see, for example, Collins, Reference Collins2001; Corporate Leadership Council, 2004; Katzenbach, Reference Katzenbach2000; Martel, Reference Martel2002; O’Reilly and Pfeffer, Reference O’Reilly and Pfeffer2000). And, while there has been no research by business and management scholars on the direct impact of female employees on the bottom-line performance of companies in the MENA region, a survey by McKinsey in 2010 reported that 34 per cent of companies in the Middle East who had made genuine efforts to empower female employees ‘reported increased profits; and 38 per cent said that they expected to see improved profits as a result of these initiatives’ (Barta et al, Reference Barsh, Devillard and Wang2012).

A 2011 Booz&Co report, citing data from the World Bank, indicated that some countries in the MENA region could improve their annual GDPs by an average of 34 per cent if women were employed in their national labour markets at the same rates as men are (Hoteit et al, Reference Hoteit, Abdulkader, Shehadi and Tarazi2011). A more recent comprehensive global report by the McKinsey Global Institute has examined how economic, legal and social gender inequality is distributed across the world and the impact of this on national economic growth and development Using fifteen standardised gender-parity indicators across ninety-five countries that are home to 93 per cent of the world’s female population, McKinsey analysts found that North America and Oceania had the highest average equality score of 0.74 and Western Europe 0.71 (a score of 1 represents perfect economic, legal and social parity between men and women). They noted that the MENA region had an overall score of 0.48, South Asia (excluding India) had the lowest score of 0.44 and the UAE, Oman and the KSA were three of the twenty-one countries that had ‘high’ or ‘extremely high’ gender equality gaps ( Dobbs et al, Reference Dobbs, Woetzel, Madgavkar, Elingrud, Labaye, Devillard, Kutcher, Manyika and Krishnan2015 ix, 9 and 15). They also estimated the loss of national economic output that accompanies large gender inequalities. Globally, the world economy could be $28 trillion (26%) richer, if the gaps in labour-force participation, hours worked and productivity of women and men were bridged. Even reducing these gender gaps to the level of the most gender-egalitarian countries in each region would add $12 trillion to global output by 2025. India could add more than 55 per cent a year to its GDP, South Asia nearly 50 per cent, Latin America 38 per cent, East and South East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa more than 30 per cent, and the MENA region could add more than 50 per cent to its cumulative annual GDP. Their report also noted that ‘In India and the MENA region, boosting female labour-force participation would contribute 90 and 85 per cent, respectively, to the total additional economic opportunity’, or $2.7 trillion in total GDP by 2025 (Dobbs et al., Reference Dobbs, Woetzel, Madgavkar, Elingrud, Labaye, Devillard, Kutcher, Manyika and Krishnan2015: 4).

The message from these and other similar studies that are reviewed in Chapter 8 is very clear: to be more competitive, now and in the future, organisations in this part of the world must utilise the full range of talents of all their staff, regardless of their gender (or, indeed, national and cultural backgrounds), and robust gender diversity policies make very good business sense (Ellis et al, Reference Ellis, Marcati and Sperling2015; Hunt et al, Reference Hunt, Layton and Prince2015; International Finance Corporation, 2013b). There are many reasons to believe that this has to – eventually – happen in public- and private-sector organisations in the MENA region, if these countries are to transform the rhetoric of creating competitive economies into a reality in the future.

Consequently, there are three principal reasons the ideas presented in this book may be of interest to business and political leaders in this part of the world. First, the unrest in many MENA countries during the 2000s and early 2010s was and is a reaction to US military incursions in the region, autocratic and repressive dictatorships, corruption, inequality, poverty and dwindling economic opportunities for the rapidly growing number of indigenous young people in this region of the world. This unrest, as noted earlier, was also characterised by the active participation of tens of thousands of women, demanding greater economic, political and social rights (Bennoune, Reference Bennoune2013; Coleman, Reference Coleman2010). Second, there is a growing realisation – at least among more liberal, educated and well-informed groups in the MENA region – that their countries have to come to terms with an inescapable economic reality (even those with substantial oil and gas reserves): there are no examples of advanced, diversified, industrial economies in which a substantial proportion of women are not economically active in their labour markets and where barriers to their entry into all professions and occupations have been dismantled over the last 30 to 40 years (Aguirre et al, Reference Aguirre, Hoteit and Sabbagh2013; Dobbs et al, Reference Dobbs, Woetzel, Madgavkar, Elingrud, Labaye, Devillard, Kutcher, Manyika and Krishnan2015; Saddi et al, Reference Saddi, Sabbagh and Shediac2012; Shediac et al, Reference Shediac, Moujales, Najjar and Ghaleb2011).

These are, as we will see, inescapable economic realities, and if the nation-states of the MENA region are to rise from their generally low ranking among the world’s leading economies and on other many other indexes of national development, can they continue to hold back the dreams, aspirations and ambitions of women in this region for much longer? Of course, similar arguments have been made repeatedly by The Economist (2016e; 2016c; 2016b; 2015e; 2015c; 2014b; 2014a and 2002), by the United Nations in all of its reports on the MENA region and in the other studies cited in this chapter. For example, in his foreword to the 2005 AHDR, the Chairman of the United Nations Development Program observed that:

The situation for women in Arab countries has been changing over time, often for the better, yet many continue to struggle for fair treatment. Compared to their sisters elsewhere in the world, they enjoy the least political participation. Conservative authorities, discriminatory laws, chauvinist male peers and tradition-minded kinsfolk watchfully regulate their aspirations, activities and conduct. Employers limit their access to income and independence. In the majority of cases, poverty shackles the development and use of women’s potential. High rates of illiteracy and the world’s lowest levels of labour participation are compounding to create serious challenges. Although a growing number of individual women, supported by men, have succeeded in achieving greater equality in society, and more reciprocity in their family and personal relationships, many remain victims of legalized discrimination and enshrined male dominance.

This year’s report presents a compelling argument as to why realising the full potential of Arab women is an indispensable prerequisite for development in all Arab states. It argues persuasively that the long hoped-for Arab ‘renaissance’ cannot and will not be accomplished unless the obstacles preventing women from enjoying their human rights and contributing more fully to development are eliminated and replaced with greater access to the tools of development [and by] placing Arab women firmly at the centre of social, economic and political development in the entire region

Third, as documented earlier, on almost every metric of economic development most countries in the MENA region lag behind the leading economies of the world and, with the notable exception of their oil and gas sectors, they have very few world-class companies. Consequently, as noted in the Preface, if real change is to occur in the most conservative countries of this region, such as the KSA, the main impetus for this will probably not come from their political or religious leaders. Rather, it will come from their business leaders, because they know (or, at least, they should know) what will happen to economic growth and living standards in their countries if they do not use their remaining oil and gas wealth to develop their economies and to reform their commercial, educational, civic and governmental institutions over the next two decades. This belief is supported by numerous reports and studies published between 2000 and 2016 which have also argued that there is and will continue to be a direct causal link between the economic development of all nation-states in the MENA region and the emancipation of women in these countries. Indeed, as this book will endeavour to show, neither can come to pass without the other. The recent reports by the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, the United Nations, McKinsey, Booz&Co and others cited in this chapter have all highlighted the need for countries in the MENA region to improve educational opportunities for women – particularly at the tertiary level – increase the participation of women in regional labour markets and in all professions and occupations and create legal and regulatory frameworks that can promote equal-opportunity principles. Implicitly, these reports also indicate that the cultural, attitudinal and structural barriers that prevent women from playing a much fuller role in public- and private-sector organisations must be challenged and dismantled. If they are not, the long-term economic and political future of most countries in the MENA region looks bleak. The fact that all Arab countries had, by 2010, signed the United Nations Convention on all Forms of Discrimination against Women signifies very little unless they can initiate the long and complex process of implementing its many key recommendations and policies.

A few countries in this region have already woken up to these realities. For example, even before the UAE experienced the sobering economic downturn of the late 2000s and early 2010s, this small country was already facing a variety of economic, social and environmental challenges. The UAE government’s 2015 and 2008 national strategic plans had both made it clear that the country had to continue to focus on industrial and business development in order to safeguard the country’s economic growth and prosperity in the future, an issue that we return to look at in Chapters 2 and 3 (Dubai Strategic Plan 2015; United Arab Emirates Government, 2008). Similar challenges confront all countries in the Gulf States and the broader MENA region. The KSA, for example, has one significant advantage and one significant disadvantage when compared to the UAE. Its advantage is that the country has oil reserves that may last for another 20 to 30 years at current and anticipated rates of consumption. Its great disadvantage is that, on all measures and metrics of economic, social and political advancement for women, it now lags at least fifteen years behind the UAE and decades behind the leading industrial economies of the OECD. Oman is in a similar position to the UAE because, while its oil and gas revenues are declining year by year, it does have a more liberal approach to both women’s education and their employment rights when compared to the KSA.

As noted in the Preface, this book also describes how public- and private-sector organisations in this part of the world can create a level playing-field for women and also ensure that their best female employees are given the opportunity to rise to leadership positions in the future. These processes have been documented in an extensive academic and practitioner literature that has described the introduction of equal-opportunity policies in many Western public- and private-sector organisations during the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s. Many of these have already been implemented, to varying degrees, in almost all businesses operating in North America, Europe, Oceania and other regions of the world. A question that will, of course, be asked is ‘Can these be implemented in an Arabic/Islamic context?’, and we will address this in Chapter 9 and also describe other policy initiatives that could be implemented at the national level in MENA countries in order to promote the interests of women employees in their national labour markets.

Over time, these initiatives could create an environment that will encourage more women into professional, business and management roles and to become entrepreneurs and small business owners. In turn, if encouraged, these women could make a significant contribution to the lengthy process of building the economies that will be required to sustain the countries of the MENA region – with much larger populations – during the 2020s and beyond. Furthermore, companies operating in this part of the world do not have to wait for legislative changes to be enacted by national governments to make these changes. Providing they do not violate existing shari’a laws, indigenous companies can introduce policies and practices that will encourage talented and ambitious women to work for them. They can create working environments and organisational cultures in which women employees are judged on competence, character and performance, not their gender, and are empowered to rise to leadership positions in the future.

They could be implemented – with a high level of commitment and adequate resources – by any group of senior managers in companies that can see the need for change and who are committed to the transformation that would be required in the operational cultures of their companies, in their recruitment and employment practices and in the career and promotion opportunities they provide for female employees. They can learn how to do this from best-practice examples of ‘women-friendly’ companies in the West, which have made this a strategic human resource management (HRM) priority over the last ten to fifteen years. They can also benefit from advice about the implementation of strategic equal-opportunity policies and how to create working cultures and HRM policies that support the interests of their women employees within generally conservative Islamic contexts. The well-established equal-opportunity principles described in Chapter 9 are now integral elements of business and management practices in many countries, and we will see that these ideas and principles are now beginning to gain some traction in a few companies that operate in the Gulf States and the broader MENA region. These would benefit any companies that are concerned about their long-term futures, winning the local and global ‘war for talent’, maximizing their growth prospects and enhancing their competitive abilities in the MENA region and globally in the future.

1.5 Conclusion

It is possible that some readers of this book may believe that it is not appropriate for a Western man to write about these issues or suggest what countries in the MENA region ‘should do’ vis-à-vis their womenfolk, while others may suggest that it is yet another example of a Western-centric interpretation of a part of the world that only Arabs can truly understand (al-Barwani, Reference al-Barwani, Sadiqi and Ennaji2011). While these concerns are understandable, it can also be said that enhancing the economic and legal rights of women in this region is, as all of the female and some of the male interviewees in this book believed, consistent with the teachings of the Prophet. It is also in harmony with Islamic teachings which emphasise the intrinsic worth and dignity of all human beings and the principle of hisbah (doing good). It is consistent with the Islamic principles of hadith – of being true to the teachings of the Prophet and his belief that improving our knowledge about the world was a noble activity in itself – and also ijtihad, the need to reinterpret Islamic teachings and laws in the light of changes and developments in Islamic societies, a principle endorsed by all of the Arab women and men who contributed to the first United Nations AHDR in 2005 (United Nations, 2005: 147, 222–223). It is also consistent with the core principles and recommendations laid down in the Convention on all Forms of Discrimination Against Women which, as noted earlier, all countries in the MENA region are now signatories to (even if they have done this, in all cases, with significant qualifications). And, in the words of one very brave female Saudi Arabian activist, writer and journalist:

The rigid interpretations of Islamic law by hard-liners no longer provide solutions to the problems facing the Arabic world today … we cannot continue to allow only one legal authority on the interpretation of shari’a laws or recognize only one absolute judgement on judicial issues … fundamentalists must understand that no one has absolute authority on the truth … We need to make better judgments and formulate new legislation on issues related to the status of women, Muslim lifestyles, Islamic economies, the situation of Muslims in non-Muslim societies, the relationships between Muslims and the West, and so on

Moreover, this book is essentially a narrative account of university-educated, professional Emiratis, Omanis and Saudis describing their experiences (good and bad) of the societies they have grown up in, the roles of women and men in their societies and workplaces and, most importantly, their hopes and fears for their countries and their dreams and aspirations for their children’s and grandchildren’s futures. It is their story and one that their rulers may wish to listen to. Readers of this book will also know that history is littered with examples of what has invariably happened to human societies when their political and religious leaders have been unable to relinquish and share power, who have failed to adapt to new circumstances and challenges and have lost touch with their citizens. In every case, they have struggled to survive and most of them have ceased to exist (Acemoglu and Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2012, Beinhocker, Reference Beinhocker2007; Diamond, Reference Diamond2005; Morris, Reference Morris2011; Tainter, Reference Tainter2006).

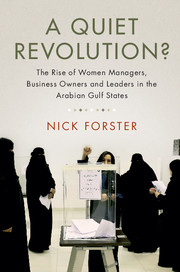

Hence, although it may not be easy for some readers of this book to accept this proposition, the people and governments of the entire MENA region are confronted with a range of existential economic, political and social challenges, including one that I now consider to be an irreversible ‘quiet revolution’ in the aspirations and hopes of a rapidly growing number of educated, ambitious and increasingly independent women in the UAE, Oman and the KSA. The potential of this demographic and social change is enormous and, if nurtured and encouraged, could have many beneficial and transformational effects both within and beyond the borders of these three countries in the future. While the challenge of transforming entrenched conservative social attitudes and overcoming institutional inertia to allow women to become more equal partners in the political systems and economies of the MENA region is formidable, I hope that the political and business leaders of all countries in the MENA region might respond in a positive way to the ideas and recommendations contained in this book. They may also resonate with anyone who has an interest in the future of the MENA region, because if the many challenges that confront this part of the world are not resolved soon, this will have a direct impact on all of us in the future.