1 Introduction

The passage of the Administrative Review Tribunal Act 2024 (‘ART Act’) and associated legislation provided a once-in-a-generation opportunity to redesign Australia’s federal administrative review system.Footnote 1 The reforms abolished the almost 50-year-old Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) and created the Administrative Review Tribunal (ART). Many have welcomed the move, following persistent complaints that the AAT was under-performing, over-budget and no longer ‘fit for purpose’.Footnote 2 A key complaint made of the AAT was that it was ‘beset by delays and an extraordinarily large and growing backlog of applications’.Footnote 3 This was particularly the case in the Migration and Refugee Division (MRD), which was charged with hearing appeals against the refusal or cancellation of visas allowing non-citizens to remain in Australia. In June 2024 migration cases made up 86% of the AAT's caseload and the tribunal was dealing with a backlog of over 63,000 cases.Footnote 4 The ART, which commenced operation in October 2024,Footnote 5 inherited this backlog, together with the headaches that contentious criminal deportation decisions have generated.Footnote 6

With the creation of the ART, the government aims to provide a mechanism for merits review that is fair and timely, and which improves the transparency and quality of decision-making.Footnote 7 As we examine in this article, the ART Act does not just re-create the AAT. To begin with, the rigid divisions in the AAT have been replaced with more flexible jurisdictional areas. We will argue that many of the reforms are welcome and are likely to significantly improve tribunal decision-making. The introduction of an independent merits-based appointment and re-appointment process,Footnote 8 and the abolition of the Immigration Assessment Authority (IAA) and fast-track process for certain refugee applicants,Footnote 9 are immediate examples in point. The re-establishment of the Administrative Review Council (ARC) to monitor the integrity of the new administrative review system is another positive development.Footnote 10 Our focus, however, is on the procedures that govern the tribunal’s operation – and the extent to which these do and do not apply to migration and protection decision-making. As noted, this is the field where the old AAT’s problems were most acute. It is also the area where the ART faces immediate challenges because of the inherited caseload.

A central hallmark of the ART reforms is the focus on creating simple, flexible and unified procedures for administrative decision-making across the new body. Our concern is that the decisions in migration and protection jurisdictions continue to be treated as exceptional. Of particular concern are the codification of the natural justice hearing rule and shorter, inflexible time limits for lodging applications for review. The ‘carve outs’ from the ART’s general procedures mean that many of the benefits in terms of efficiency, flexibility and adaptability of procedures set out in the ART Act do not apply to the migration and protection jurisdictions – again, where they are most needed.

In this article, we draw on data and analysis from the Kaldor Centre Data Lab to question the government’s justification for retaining separate codified procedures and other restrictive rules for the migration and protection jurisdictions.Footnote 11 Our concern is that the government appears to be doubling down on the false premise that separate, and more restrictive procedures are needed for migration and protection decision-making. When the migration tribunals were amalgamated into the AAT in 2015, the government similarly maintained relatively inflexible procedural rules for migration and protection applicants. Despite the inherent conflict this created within a body designed to harmonise procedural systems, the primary rationale has always been that codification increases efficiency and certainty in decision-making.Footnote 12 This view reflects a long-standing approach in Australian governments that fairness and efficiency are in tension, and that limiting the procedural rights of migration and protection visa applicants is required to ensure timely and efficient decision-making. Examining the history of attempts to codify and limit migration applicants’ procedural rights, and related efforts to curtail access to judicial review, we argue that there is no evidence that this approach has had its intended effect. It is time that adequate consideration is given to conducting migration and protection proceedings with the same procedural flexibility granted to other applicants in administrative appeals.

Our particular interest is in the impact codification of procedures has had at a systemic level. Merits review of migration decisions operates in the broader context of Australia’s federal administrative justice system, which includes access to judicial review.Footnote 13 We will argue assertions that restrictive procedures deliver consistency, and efficiency must be viewed in the context of judicial review rates and outcomes. If a tribunal decision is accepted, that is the end of the story. If either party is dissatisfied, Australian law – indeed the ConstitutionFootnote 14 – allows the legality of decisions to be judicially reviewed. The grounds for reviewing tribunal rulings include denial of procedural fairness, unreasonableness and failure to follow prescribed procedures. Unlike merits review, decisions by courts in judicial review proceedings result in a matter being sent back (or remitted) to the tribunal for re-hearing in accordance with the law. The remittal of a decision means the merits review process starts all over again.

The number and proportion of applications taken on judicial review directly impacts the efficiency of the system as a whole, given the time taken by the courts to finalise applications. The proportion of cases in which applicants succeed in having their matter remitted to the tribunal for redetermination also impacts the efficiency of the system. In this respect the ratio of remittals can be viewed as a proxy for certainty of decision-making. Higher rates of applicant success can indicate lower levels of consistency and higher levels of serious legal error in tribunal decision-making.Footnote 15

We draw on a novel dataset on the judicial review of migration and protection decisions over a 43-year period to show that there is no evidence that restricting procedural rights of migration applicants has either reduced the number or proportion of judicial review applications or increased the success rates of those applications for the government.

We acknowledge that caution is required when drawing inferences from descriptive statistics, particularly where decisions involve very different and variable factors including national and world events. We will attempt to identify some of the meta trends or influences on caseloads over the years. Nevertheless, we argue that the analysis reveals no evidence that the progressive and often reactive codification of procedures governing the review of migration and refugee decisions has reduced the number or proportion of cases in which judicial review has been sought of AAT rulings. Nor has it reduced the success rates of relevant judicial review applications. While our analysis does not provide causal evidence that the measures are ineffective, we argue that the onus should be on the government to explain why they believe a separate procedural code for migration cases in the ART is justified. We will propose several reasons why separate treatment may be regressive or even counterproductive.

It is important to note the analysis in this article is limited by the data which we were able to access through the Freedom of Information (FOI) process and annual reports. Access to more detailed data would open opportunities for more robust analysis in relation to whether the new system will achieve the Government’s stated policy objectives and not have unintended consequences. In this regard we argue that it is essential the ART adopt a robust approach to data collection and transparency to enable ongoing evaluation of its operation and to identify areas in need of further reform. The revival of the Administrative Review Council creates one vehicle for this oversight and review. Another would be to restore to the Department of Immigration some of its traditional research and development functions.

The article begins in Part 2 by examining the history of reforms aimed at codifying and restricting procedures for migration and protection decision-making. These are paired with related legislative attempts to curtail access to judicial review and an account of how courts responded at each step. In Part 3 we use statistical data to question the impact and effectiveness of the various measures across time. We do this by analysing statistics on the number, proportion and outcomes of judicial review of migration and refugee tribunal decisions over a 43-year period. In Part 3.5 we provide a case study focusing on the IAA. We argue that the statistical record for the IAA provides strong evidence that restrictions on procedural rights of applicants can backfire, leading to higher overturn rates at judicial review. In Part 4, we move to the present, to focus on the operation and hearing procedures of the ART. We examine procedural rules for migration and protection decision-making and their potential impact on the fairness and efficiency of decision-making. Our central argument is that historical data on the judicial review of tribunal decision making in these fields provides grounds for questioning the wisdom of (once again) adopting an exceptional approach for migration and protection visa appeals.

The article concludes in Part 5 with some reflections on the expressed reasons for the creation of the ART. We point out that criticisms of maintaining special procedures for migration and protection cases have come from a variety of actors. These include former members of the AAT charged with making decisions in these and other areas. These concerns were recognised by the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee report on the ART and associated bills.Footnote 16 The majority and dissenting reports both recommend that the bills be passed. However, the majority report also recommended that the government refer the amendments to the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (Migration Act) and the matters raised in evidence to the committee ‘regarding the operation of ART in relation to migration and asylum matters’ to the re-established ARC.Footnote 17 It is our hope that our data analysis may contribute to future reviews by the ARC or other body and provide food for thought about how to maximise the effectiveness of the new tribunal going forward.

2 A brief history of the codification of migration decision-making and attempts to curtail judicial review

The idea of establishing special procedures for migrant and refugee applications at the ART is not new. The bespoke system reflects many years of ‘reactive’ law making, with particular provisions often introduced in response to one or more tribunal or court decisions. Our central argument will be that such codification of procedures has never made migration processing either more efficient or fairer. On the contrary, it has fostered a sense of combat and tribalism that has made the system increasingly inefficient.

Historically, the codification of migration decision-making has involved both the articulation of the criteria to be taken into account and the procedures that decision-makers and reviewers must follow in deciding a case. Many have documented the fact that the codification process sprang from a desire in politicians to assert their dominance over immigration policy and implementation, with the courts (through judicial review) identified as the threat to political control.Footnote 18 Codification efforts and related moves aimed at limiting judicial oversight of decision-making have been based on the assumption that limiting procedural rights of applicants will lead to fewer court actions and therefore more efficient decision-making.Footnote 19 Of course, neither litigants nor courts have taken lightly attempts to limit judicial review powers. Indeed, for the courts, immigration became the locus for an existential crisis that has led to constitutional questions about the nature and extent of the place of judges in Australia’s democracy.Footnote 20 We will turn to these matters in Part 5.

The codification of migration decision making began in 1989 with the first attempt to reduce policies and sweeping administrative discretions into regulations.Footnote 21 This is also the year in which the first statutory merits review bodies were created for migrants, styled after the Veterans Review Board.Footnote 22 The arrival of boats carrying people seeking asylum in November 1989 marked the beginning of a saga that brought political concern about irregular maritime arrival (IMA) judicial review applications to a head. Lawyers mobilisedFootnote 23 and instituted a series of actions challenging attempts to exclude the irregular arrivals and deny their protection demands. The embroglio saw the institution of the first iteration of mandatory detention alongside the first explicit attempt to prevent judicial oversight of detention.Footnote 24 There followed soon after a more comprehensive response in the Migration Reform Act 1992 (Cth) (‘Migration Reform Act’).

This legislation introduced separate procedural codes designed to articulate and limit procedural fairness obligations for primary decision makers, merits review bodies – and the courts. The aim for migration decision-making was to ‘codify [the] decision-making processes’ that officials must follow when making migration and refugee decisions.Footnote 25 The subdivision in the Migration Act was entitled: the ‘Code of procedure for dealing quickly and efficiently with visa applications’.Footnote 26 The idea was to replace common law rules of natural justice with a statutory formulation. The drafters wanted to replace procedural fairness as a common law concept with procedural ultra-vires, where the parameters of legal decision making were determined by Parliament.

The final parts of the Migration Reform Act did not come into force until 1 September 1994. These dramatically changed the system for judicial review by taking migration out of the mainstream of Australian administrative law. The Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 was amended to exclude from its remit all decisions made under the Migration Act. The Migration Act was changed to create a strangely limited form of judicial review. Part 8 made express the idea that the role of the Federal Court should be to determine the extent to which decision-makers, including merits reviewers, were complying with the letter of immigration law. The legislation provided that the Federal Court could not review migration decisions on three review grounds seen as vehicles for judicial activism: natural justice, and the consideration grounds of relevance and reasonableness.Footnote 27

The Migration Reform Act also sought to reduce judicial review by widening the scope of merits review. The Immigration Review Tribunal was reimagined as the single-tiered Migration Review Tribunal (MRT).Footnote 28 The Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) was established to provide refugee claimants with oral hearings in a ‘closed’ review process.Footnote 29 Again, the expressed explanation was that establishing the RRT as a body where applicants would have the right to an oral hearing would reduce the judicial review of refugee decisions by a factor of 75%, from a predicted 20% review rate to 5%.Footnote 30 As we will show, this is far from what occurred.Footnote 31

In fact, the 1990s saw a steady increase in applications for judicial review of migration and refugee decisions.Footnote 32 The most spectacular failure in attempts to stifle judicial review was the first Part 8 of the Migration Act. When the restrictive legislation was challenged in the High Court, a narrow majority upheld the constitutionality of the measure,Footnote 33 thereby confirming that the High Court was the only judicial body authorised to determine the legality of migration decisions. By the end of the decade, Australia’s apex court was faced with an impossible caseload of over 3,000 migration matters.Footnote 34 The response of course was to attempt to extend the restrictions on judicial review to the High Court – a measure that, again, failed spectacularly.Footnote 35

These attempts by the government to codify procedures in migration and protection decisions were met with particular resistance by the courts. In 2001, a majority of the High Court found that the code in the Migration Reform Act had not clearly and explicitly excluded common law natural justice.Footnote 36 The government responded with the Migration Legislation Amendment (Procedural Fairness) Act 2002 (Cth), inserting the now common (exhaustive) ‘codifying clauses’ into the Migration Act.Footnote 37 The expressed intent was to make it clear that the code excluded common law natural justice, in order to allow for ‘fair, efficient and legally certain decision-making processes’.Footnote 38 In fact, the amendment created substantial uncertainty for judicial review, with some Federal Court judges applying the codifying clauses strictly and others limiting its effect. The Explanatory Memorandum records that the intention was to reduce (selected) principles of the common law into statutory procedures. Some judges interpreted the statutory code as an exhaustive statement of the procedural requirements.Footnote 39 Others took the view that the statutory code did not prevent the importation of elements of the common law not mentioned in the Act.Footnote 40 When the matter seemed settled,Footnote 41 the High Court ruled that there could be instances where the code did not apply and so did not exclude the common law.Footnote 42

The procedural codes for departmental and merits review bodies have been amended on many occasions - ofttimes in response to particular cases – as had been the case in the 1980s.Footnote 43 While it took the High Court several years to rule that natural justice was not excluded by the procedural code, in reality the judiciary had already interpreted the code to embody common law obligations beyond those obviously incorporated. For example, the Migration Reform Act introduced ‘invitation to appear’ clauses. These were intended to provide applicants with the opportunity to put their case to the Tribunal before a decision was reached.Footnote 44 After a number of Federal Court judges interpreted the clauses to apply to procedures adopted during hearings,Footnote 45 the government amended the clauses in 1998 to more explicitly restrict their scope. Sections 360 and 425 of the Migration Act were amended to require the tribunal to give migration and protection applicants respectively the opportunity to ‘appear before the Tribunal to give evidence’ and (in the case of migration rulings) ‘present arguments relating to the issues arising in relation to the decision under review.’Footnote 46 Over the ensuing years, the Federal Court again read natural justice obligations into the legislation, finding that the code required duties such as providing applicants with a ‘real and meaningful’ opportunity to present their case,Footnote 47 the provision of an interpreter,Footnote 48 and the opportunity to respond to issues raised at hearings.Footnote 49 These expansive interpretations of the invitation to appear clause were supported by the High Court, which held that common law principles should inform the interpretation of the clause,Footnote 50 even in light of the codifying clauses.Footnote 51

Legislative changes relating to notification and time limits were also reactive to particular cases.Footnote 52 It is beyond the scope of this paper to detail every change that has been made to the various codes. It suffices merely to note that each change has been seen as a hard-fought win, mostly by departmental officials, but occasionally by Ministers particularly invested in the scheme. Minister Ruddock stands out in this context as one who was acutely reactive to individual cases. He was not shy in calling out reviewers and judges who disagreed with his interpretation of the law, describing them on one occasion as ‘ignoring […] the will of the Australian people’.Footnote 53 For present purposes, the history explains why the Department has fought so hard to retain the codes even after the officials and politicians who sponsored the changes are long retired.

The courts have interpreted broadly another aspect of the procedural code: requirements that the tribunal give applicants particulars of matters considered crucial to a decision. The Full Federal Court and High Court initially read the disclosure clauses as requiring tribunal members to provide protection visa applicants with written summaries of adverse material prior to making a final ruling.Footnote 54 In response, the government enacted the Migration Amendment (Review Provisions) Act 2007 (Cth) to provide decision-makers with greater flexibility when meeting their procedural fairness obligations.Footnote 55 While the High Court responded by relaxing its interpretation of the clause, it ultimately found that the procedural code needed to be interpreted in its context, such that a breach of the statutory code be treated similarly to a breach of common law natural justice.Footnote 56 This effectively signalled an end (of sorts) to governmental efforts to isolate its procedural code from the influence of common law and exclusively determine the procedure to be followed by decision-makers in migration and refugee matters.Footnote 57

3 Evaluating the efficiency of codified procedures

The foregoing account of the evolution of the procedural codes in the Migration Act is necessarily impressionistic. What we have shown is that ‘codification’ in particular migration appeal contexts has inspired judicial review challenges. Court rulings have inspired further statutory reforms. It is beyond the capacity of this article to assert direct connections between the procedural changes in the law we have outlined with statistical trends in judicial review applications of tribunal rulings. What we have done is to collate and analyse data on judicial review applications of migration and protection decisions made by relevant tribunals over a 43-year period. The goal was to explore the broad correlation between the codification of decision-making, and related attempts to restrict appellate procedural rights and access to judicial review, with the incidence and outcomes of relevant judicial review applications.

Before turning to the data, it is worth noting that historical variations in judicial review applications do ‘map on’ to what might be called ‘portfolio’ trends. There have been two critical areas in the migration space where the battles between the executive and the judiciary have been most fierce – in part because the stakes for applicants are so high, but also because both have been vehicles for political contest. The first has concerned IMAs and the related field of refugee law. Refugee claimants are non-citizens who seek to remain in Australia because they claim to face persecution or other forms of serious harm if returned to their country of origin.Footnote 58 The second involves the deportation and permanent exile of permanent residents convicted of serious crimes, a prime example of a body of law which has attracted its own short-hand moniker – crimmigration.Footnote 59

The first part of this analysis embraces judicial review of appellate rulings across both of these areas, as well as all other areas of migration decision-making, examining both migration and protection-oriented tribunals. Because the focus of the Kaldor Centre Data Lab is on refugees, we will use as a case study in Part 3.5 the merits review regime established to deal with a particular cohort of protection visa applicants.

3.1 Methodology

The following analysis utilises data made available through FOI requests and annual reports. The data in Table A1 on the judicial review of decisions made under the Migration Act was created by combining data from: the Department of Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs’ Annual Reports in 1990 and 1994; the Immigration Review Tribunal’s Annual Reports from 1991 to 1999; the Migration Review Tribunal’s Reports from 1999 to 2015; the Refugee Review Tribunal’s Annual Reports from 1994 to 2015; the Administrative Review Tribunal’s Annual Reports from 2016 to 2024; as well as statistics published in the Sydney Law Review by Crock in 1996.Footnote 60 From these sources, we were able to create a near-complete data set of the number of judicial review applications made in respect of decisions made under the Migration Act, the proportion of decisions subject to judicial review and the success rate of those applications, from 1981 to 2024.

For our case study on the IAA, we rely on data published by the AAT in its annual reports from 2016 to 2023. From these reports, we were able to construct a complete data set of the number and proportion of IAA decisions subject to judicial review, and the remittal and set aside rates of those decisions, from 2015 to 2024: see Table A2 and Table A3. We also rely upon data compiled by the Kaldor Centre Data Lab, which was originally obtained through a request to the AAT under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth).Footnote 61 These data sets include data points on the outcome and applicant’s country of origin for all AAT and IAA cases between 1 January 2015 and 18 May 2022. During this period, 26,036 Protection Visa decisions were made by the AAT and 10,000 decisions were made by the IAA. Using this data, we were able to compare success rates between the AAT and IAA, across each country of origin that was represented before both tribunals.

Before turning to our analysis, it is important to note certain limitations of our study. Primarily, we are limited by the lack of available data on the judicial review of migration decisions. Using the data published by the government in its annual reports, we are only able to describe broad trends in rates of judicial review. As we state above, it is beyond the nature of this article, and the available data, to provide an in-depth analysis into the relationship between specific procedural changes and rates of review. In addition, our analysis is restricted by certain gaps in government reporting of data, particularly in annual reports in the 1980s, which further restricts our ability to provide a comprehensive illustration of the influence of codified procedures on the efficiency of migration decision-making.

3.2 The Number of cases taken on review

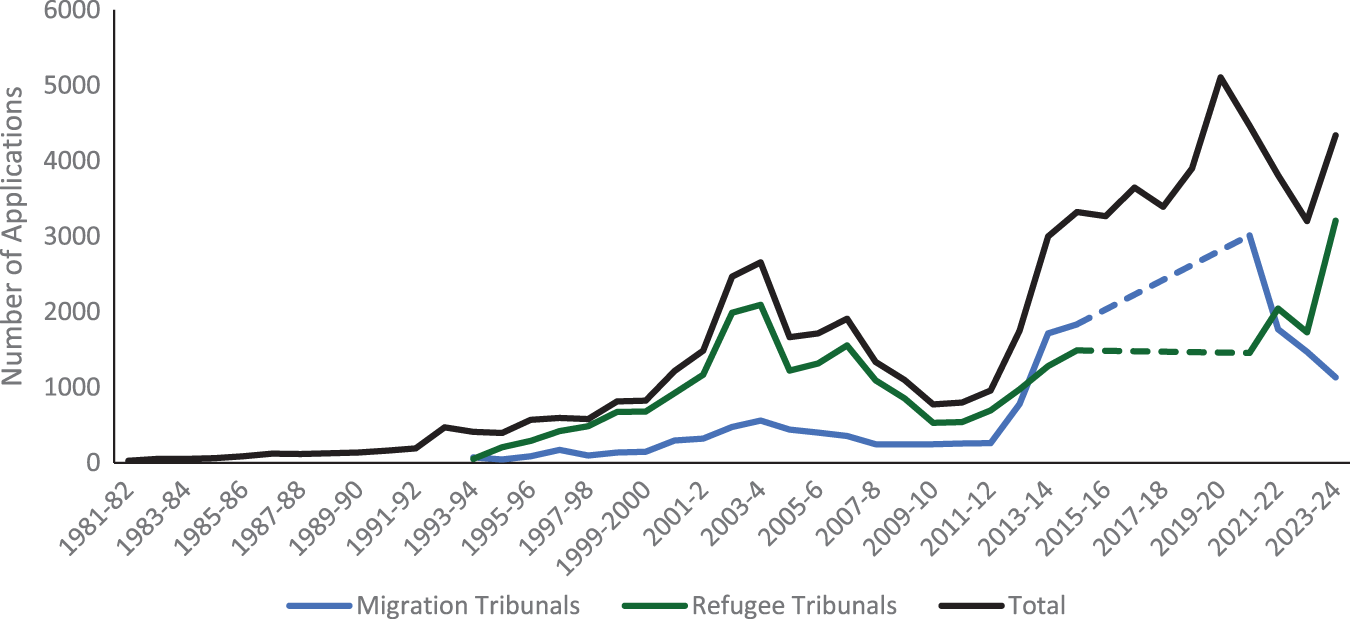

The graphs below set out data we have compiled on judicial review of migration and protection decisions in tribunals between 1981 and 2024 (see Table A1 in Appendix). First, we collected data on the number of applications for judicial review of migration and protection decisions made each year. Figure 1 shows that the number of judicial review applications increased over time, from 27 applications in 1981-82, to 568 in 1995-96 (the year after the Migration Reform Act came into force), to 4,339 applications in 2023-24. The numbers fluctuated between those years, peaking in 2003-04 at 2,653 applications, before reducing to 775 in 2009-10, and then climbing to a maximum of 4,467 in 2019-20.

Figure 1. Number of Judicial Review Applications Relating to Migration and Protection Decisions in the Federal and High Courts.

The data shows that applications for judicial review have increased over time, despite the introduction of codified tribunal procedures and restrictions on judicial review, ostensibly designed to prevent just such an occurrence. Of course, the number of migration and protection applications that the tribunals received also increased over the relevant period. At least to some extent, these increases reflect trends in the raw number of asylum claims being made.Footnote 62 The uptick in general migration appeals can also be shown to align with broader trends in the securitisation of migration law through dramatic increases in the number of visas being cancelled on grounds of character and conduct.

For example, in 1993-94, the Immigration Review Tribunal and the Refugee Review Tribunal received 1,851 and 6,984 appeals respectively.Footnote 63 By comparison, in 2019-20 (pre-COVID), the AAT MRD received 29,976 applications for review.Footnote 64 To some extent, this may explain the increase in the number of applications for judicial review of tribunal decisions.

By the same token, the data shows a sharp decline in the number of refugee appeals and applications between 2007 and 2012. As we have documented elsewhere,Footnote 65 these years saw a Labor government introduce policies to suspend for five years the processing of asylum claims made by IMA asylum seekers first from Sri Lanka and later from any country. This led to a build-up in unresolved cases which in turn prompted a Coalition government in 2013 to create the so-called ‘Fast Track’ processing system, including appeals to the IAA.Footnote 66

3.3 The proportion of cases taken on review

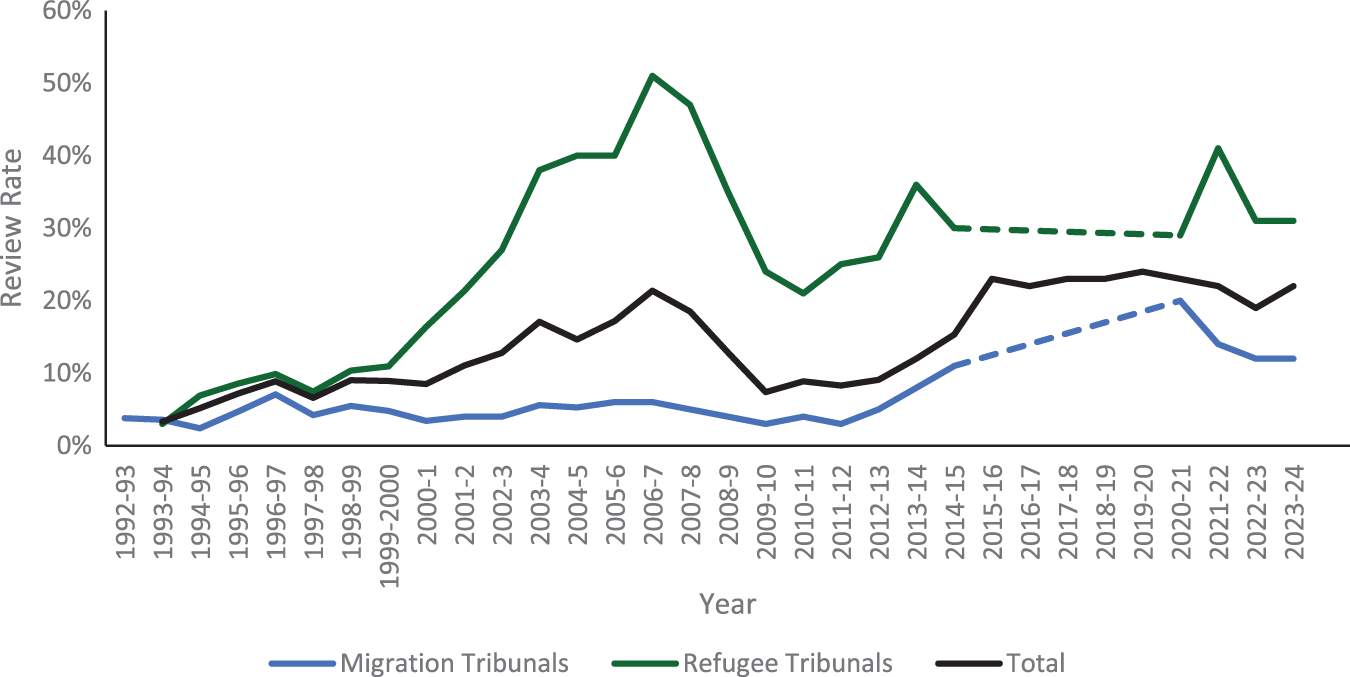

To account for the broad, overall, fluctuations in the number of migration and protection appeals made to the tribunals, we collected data on the proportion of relevant migration and protection decisions reviewed by the courts each year. Here, we found that the percentage of tribunal applicants who sought judicial review also increased over time. Figure 2 shows that 3% of tribunal applicants sought judicial review of tribunal rulings in 1993-94 (the year after the Migration Reform Act was passed). The rate of migration and refugee decisions taken to judicial review rose each year to a peak of 21% in 2006-07, before reducing to 7% in 2009-10, and then rising again to a maximum of 24% in 2019-20.

Figure 2. Proportion of Migration and Refugee Decisions Reviewed by the Federal and High Courts.

The judicial review rates for protection applicants were consistently higher than migration applicants across this period. They started at 3% in 1993-94. Over the next five years they rose to 10%, and reached a maximum of 51% in 2006-07. As we have noted, this occurred in the face of government assertions that the Migration Reform Act would reduce the judicial review of protection cases and maintain a 5% review rate from the Refugee Review Tribunal.Footnote 67 Ours is a descriptive analysis: we do not attempt to claim that the government’s codification of migration decision-making caused an increase in the number and proportion of judicial review cases. Nevertheless, the data suggests that codification has not achieved its goal of reducing judicial review applications so as to improve efficiency of the decision-making process.

Whether raw numbers or proportionate rates are considered, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the introduction of the first Part 8 of the Migration Act in 1994 did more to bait applicants into seeking judicial review than it did to stifle applications. It is well to note here that the High Court’s decision in Abebe’s case in 1999 signalled to applicants that the restrictive Part 8 provisions meant that the High Court became the only court empowered to correct fundamental legal errors including denial of procedural fairness and unreasonableness.Footnote 68 By 2001 that Court faced a backlog of 3,000 migration applications, including class actions involving thousands of litigants.Footnote 69 While the Migration Act was amended to ban class actions,Footnote 70 there is again no indication that this restricted judicial review applications any more than did the introduction of a full privative clause in 2001.

3.4 Success rates

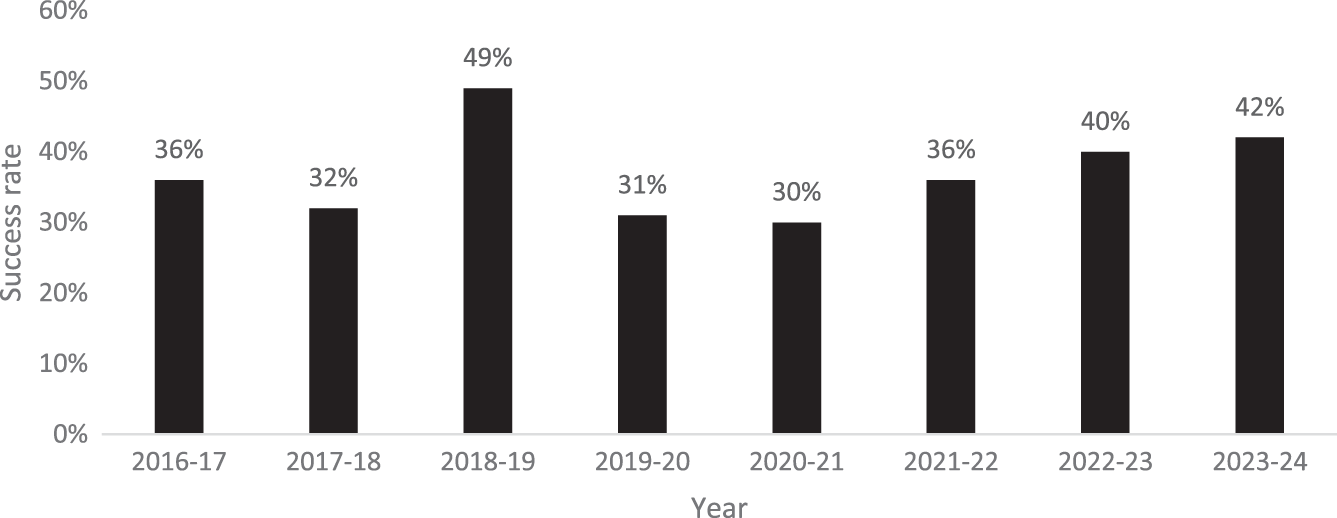

We also considered whether the government’s attempts at codification influenced the success rate of judicial review cases. Given the intention to reduce the scope of judicial review, one might expect that the success rate of court cases would decrease following the codification of decision-making. As Figure 3 shows, while there is an overall downwards trend, the percentage of migration and refugee cases which are successful before the federal courts has fluctuated over time. When key amendments to restrict procedural rights are overlaid on the graph, success rates do not display a lasting decrease following codification reforms and in some instances appear to increase, undermining any simple claim that such reforms reduce success rates over time. Accordingly, there are no clear correlations between the introduction of the Migration Reform Act and subsequent amendments, and the rates of success at judicial review.

Figure 3. Success Rates of Judicial Review of Migration and Refugee Decisions.

Again, it is important to stress the limitations of this form of descriptive statistical analysis. As the adage goes, correlation is not causation. There are a multitude of other factors beyond the codification of procedures and judicial review that may have influenced both the number of applications for judicial review and the success rate at judicial review. This includes the grounds of review relied upon, and the impact of litigation in expanding or narrowing the grounds of review available. Moreover, recent downturns in the success rates of judicial review applications need to be closely scrutinised in light of changes in the number and nature of judicial review applications, shifts in legal representation and case selection, and possible responses by judges to increased migration workloads, including evidence from other jurisdictions that heavier caseloads can be associated with lower allowance rates.Footnote 71 The proportion of migration and protection decisions taken on judicial review may also have been influenced by a variety of factors, including the complex interplay of legislative amendments with competing judicial interpretations.

3.5 Case study of the IAA

To deepen our analysis, in this section we use a case study to explore the data relating to discrete measures introduced for the express purpose of dealing expeditiously with a particular cohort of asylum applications. The IAA serves as an excellent vehicle for seeing how the codification and constraint of procedural rights affected judicial review rates and results.Footnote 72

As noted, the IAA was established in 2015 as part of the Coalition government’s ‘Fast Track’ system, introduced to address the claims of the ‘legacy caseload’ of over 30,000 asylum seekers who arrived in Australia by boat between 2009 and 2013.Footnote 73 If their visa applications were rejected, these asylum seekers were not allowed to seek review to the AAT. Instead, they were referred to the IAA, a specialised tribunal set up within the AATFootnote 74 with the express goal of providing efficient and fast review to combat the backlog of the legacy caseloadFootnote 75 and weed out ‘unmeritorious’ claims.Footnote 76

While applicants to the AAT’s MRD were entitled to an oral hearing, the IAA generally made its decisions ‘on the papers’, without a hearing with the applicant. Applications were required to be reduced to writing not exceeding 5 pages and could not include ‘new information’ unless exceptional circumstances could be shown.Footnote 77 ‘Excluded fast track review applicants’ were not permitted even IAA review.Footnote 78

These procedural restrictions do seem to have reduced the average time taken for the IAA to finalise decisions. However, they led to longer delays at a systemic level, with a very high proportion of cases being subject to and successful at judicial review. This, in turn, caused significant delays which are reflected in the fact that close to 20,000 IMA asylum seekers remained in Australia in May 2022 with no final decision having been made on their protection claims.Footnote 79 Three years later 7,042 individuals remained in limbo, either with ongoing matters or final refusals made through an inherently flawed process.Footnote 80 Elton, analysing a sample of 48 decisions by the IAA, found that the Authority was inherently ill-equipped to balance principles of administrative justice, including due process with efficiency.Footnote 81 The data we have collected seems to confirm that limiting procedural rights not only compromised the fairness of the decisions being made. It also created an inefficient and slow system burdened by high rates of successful appeals.

Between 2015 and 2024, the IAA made 10,589 decisions. Of these, 83% were the subject of judicial review in the federal courts.Footnote 82 On average, 38% of these applications were successful, generally resulting in the cases being remitted back to the IAA for reconsideration. Figure 4 shows the average success rates for each year, ranging from 30% to 49%.Footnote 83 On average, the judicial review process can take more than 2 years.Footnote 84 Clearly, any time saved by shortened procedures at the IAA stage were more than negated by the delays caused by the high rates of judicial review of these cases. When the system is considered holistically, the ‘fast track’ process did not led to any efficiency gains, but rather caused significant additional delays.

Figure 4. Success rates for judicial review cases of IAA decisions.

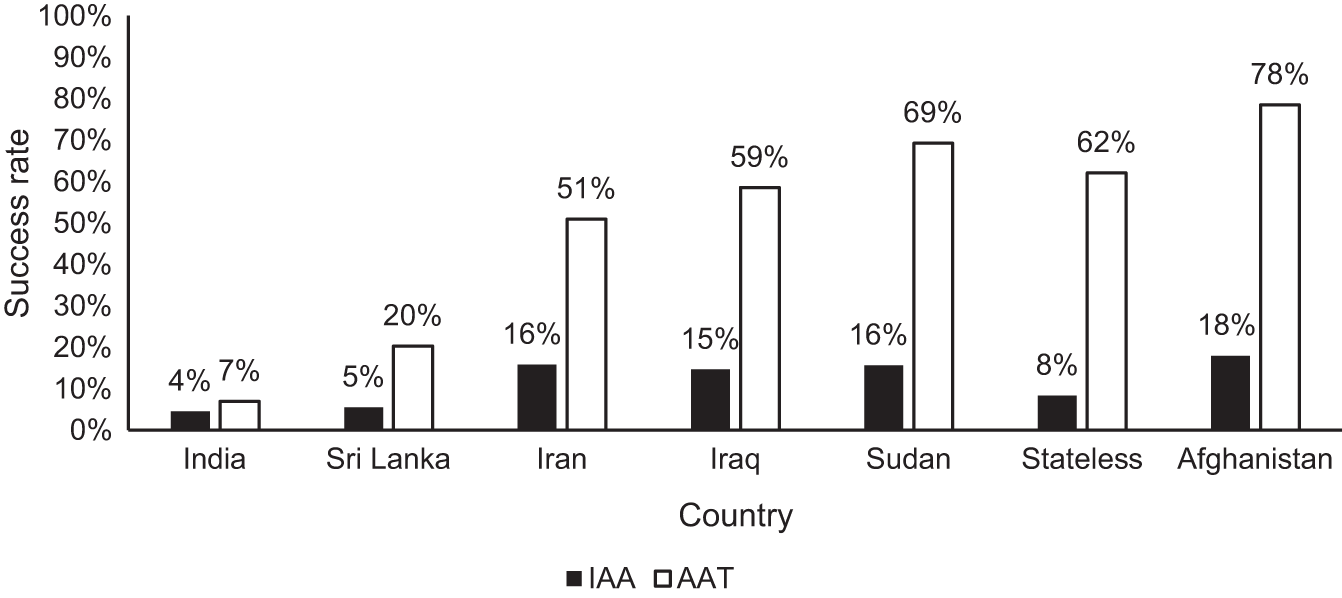

Aside from the significant rates on which IAA decisions were overturned by the courts, further data raises concerns about the quality of decision-making at the IAA, and the fact that errors may have been made because of poor procedural safeguards. Data compiled by the Kaldor Centre Data Lab in Figure 5 shows a significant variation between the success rates of cases considered by the IAA and the AAT. The AAT exhibited higher success rates in asylum claims in respect of every country with more than 20 applicants. For example, asylum seekers from Iraq were more than five times more likely to succeed at the AAT than before the IAA. Applicants from Afghanistan were more than four times more likely to succeed, and stateless applicants were more than seven times more likely to succeed before the AAT than before the IAA.

Figure 5. Comparison of IAA and AAT success rates.

This data suggests that limiting procedural rights at the IAA decreased the quality and fairness of decision-making. Applicants appearing before the IAA were less likely to succeed, when compared to applicants from the same country of origin who appeared before the AAT, who enjoyed greater procedural rights. In turn, the majority of these unsuccessful IAA cases were subject to judicial review, where the courts found high rates of decision-making errors, leading to very high remittal rates.Footnote 85 Rather than improving efficiency, the case study of the IAA supports our argument that restricting procedural rights can backfire and cause greater inefficiencies and backlogs. It should also be noted that claimants from Afghanistan have generally been permitted to lodge further claims even when their applications for judicial review of adverse tribunal rulings have failed.

4 Procedures in the ART and the impact of making exceptions in the migration and protection jurisdictions

The ART Act and Consequential Acts take some welcome steps towards establishing a more harmonised system of administrative review, including the abolition of the IAA.Footnote 86 A consistent criticism of the AAT was that the amalgamation of various specialist tribunals including those dealing with migration, refugees and social security in 2015 was not done well.Footnote 87 Before the ART changes, the review of migration decisions and refugee decisions was dealt with in four Parts of the Migration Act: Parts 5, 7, 7A and 7AA. Even across pts 5 and 7 there were numerous small variations in the treatment of similar matters, including notification methods and time limits. One positive aspect of the 2024 tribunal reforms is that provisions and procedures for migration and protection decision-making in the ART have been consolidated. The Consequential Acts amend the Migration Act to combine the review of all migration and protection decisions in one place — pt 5 of the Act. This represents a significant structural shift in migration review and a step towards a more unified approach to review across the new tribunal. Second, as the government acknowledges, the AAT, with its distinct divisions, was ‘incredibly siloed’.Footnote 88

A critical problem for the migration and refugee division was that it was excluded altogether from pt 4 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 (Cth). It was pt 4 that gave the AAT most flexibility in conducting hearings and remitting matters by consent so as to achieve timely outcomes. The ART reforms give members in the migration and protection jurisdictions more options than AAT members were relevantly given. For example, ART reviewers in all jurisdictions can conduct direction hearings and conferences.Footnote 89 They can summarily dismiss cases and the President can issue Practice Directions. The legislation allows for the convening of a special panel of members to settle contentious matters, in order to establish a tribunal-wide approach to particular issues. The broad harmonisation and simplification aim to ‘reduce the duplication and complexity of provisions in the Migration Act, streamlining review by the Tribunal’.Footnote 90

Despite these (positive) developments, the Consequential Acts retain several features of review that are specific to the migration and protection jurisdictions. The government justifies these features as ‘essential given the volume, distinct nature (including the importance of certainty of a person’s visa status) and complexity of visa-related decisions’.Footnote 91 The areas subject to bespoke codes are worth articulating, if only because it is not easy to determine where immigration parts company with the regime that governs the ART more generally. As we showed in Part 2, these areas align with a sequence of amendments made to the Migration Act over time in response to particular controversies — oftentimes particular cases.

4.1 Procedures and hearing rules

The Consequential Acts preserve s 357A of the Migration Act, which codifies the natural justice hearing rules for certain ‘critical’ matters in the migration and protection jurisdictions. The provisions are designed to supplant common law rules of procedural fairness and exhaustively state procedures that must be observed for a decision in the migration and protection jurisdictions to be valid.Footnote 92 The reforms insert ss 357A(2A)–(2D) to maintain a series of ‘carve outs’ that apply only in the migration and protection jurisdictions. The ART provisions that are subject to express override are those that give ART members: discretion in relation to procedure;Footnote 93 the ability to act informally;Footnote 94 and the ability to control the scope of the decision.Footnote 95 Section 357A(2A)(d) also excludes the application of s 55 of the ART Act which sets out rather detailed rules about the entitlement of applicants to be given a fair opportunity to present their case, including being given access to relevant information. The Consequential Acts give priority to the whole of div 7 of the Migration Act as they relate to the pt 5 procedural code.Footnote 96

One critical area where the reforms preserve the codification of natural justice is the ‘adverse information’ provision in s 359A. This section requires the Tribunal to provide the applicant with the particulars of materials that form part of its reason for affirming the decision under review, except for certain categories of information under s 359A(4). The Tribunal is not required to give the applicant information included or referred to in the written statement of the decision under review, as ‘it is reasonable that they are aware of its contents’.Footnote 97 This is particularly concerning, given the numerous barriers that many migration and protection applicants face in the review process, including accessing legal advice and interpreting written decisions that are only provided in English.Footnote 98 Amendments to s 359A(4) allow the Minister to make regulations to further restrict the types of adverse information that needs to be put to the applicant.Footnote 99 This continues and perpetuates the process of regressive and reactive law making that attacks the procedural rights of applicants discussed in Part 2.

The Consequential Acts also preserve the codification of natural justice as it applies to the notification of documents to an applicant. The new div 7 of pt 5 of the Migration Act provides a legislative framework for how the ART gives documents to migration and protection applicants. In particular, the division provides that, where the framework is followed, an applicant will be ‘deemed’ to have received documents, even where they have not actually been notified.Footnote 100 Again, the government argues that this is necessary for the efficient conduct of reviews.Footnote 101 In the context of the new tribunal the restriction on applicants’ notification rights underscores the inferior status of migration and refugee applicants.

4.2 Timeframes to Apply for Review

The other area where the Department of Home Affairs prevailed relates to the imposition of shorter and less flexible timeframes for lodging applications for review of migration decisions. In short, the existing constraints continue to apply. These include the seven- and nine-day constraints on applications to review decisions for persons taken into immigration detentionFootnote 102 and those appealing character rulings.Footnote 103 While the government’s justification for such timeframes is that they can ‘resolve the status of the applicant as quickly as possible’,Footnote 104 these continue to be ‘wholly insufficient timeframe[s]’ for applicants to read and understand the contents of the decision and the appeal process, and to have meaningful access to legal assistance.Footnote 105 This is particularly the case for applicants in immigration detention, who face significant disadvantages in accessing legal information and advice.Footnote 106

One particularly regressive aspect of the changes made by the Consequential Acts is removing the flexibility given to ART members under s 19 of the ART Act to extend time periods for review in the case of reviewable migration and protection decisions.Footnote 107 This means migrant applicants cannot seek an extension of time to apply for a review. This lack of flexibility is very concerning given the barriers that these visa applicants may face in meeting strict deadlines. These include ‘insecure housing, limited employment opportunities, complex mental and physical health issues and limited English fluency’.Footnote 108 The inflexibility undermines the ART’s ability to deliver effective and efficient justice, and risks significant harm to applicants if wrongly returned to situations of danger.Footnote 109

4.3 Providing documents to review applicants

Section 27 of the ART Act requires decision-makers to provide applicants with copies of relevant documents,Footnote 110 fulfilling an ‘important aspect of procedural fairness’: that applicants have access to the same information as the Tribunal.Footnote 111 Again, the Consequential Acts remove this requirement for migration and refugee applicants. Instead, applicants in the migration and protection jurisdictions may request that the Department of Home Affairs provide them with access to relevant documents which must then be supplied.Footnote 112 The legislation does not oblige the Department to respond in a timely manner. This is concerning given extensive wait times for FOI requests.Footnote 113 Despite the government’s argument that an ‘appropriate balance’ has been struck for the efficient management of the large migration and protection caseload,Footnote 114 it is not obvious why migration and protection applicants should be singled out for more onerous procedures compared with other applicants.Footnote 115

5 Towards the future: Reflections on the worth of procedural codes

In light of the data we have collected and analysed in this piece, we welcome the creation of a new generalist body tasked with the review of Federal administrative decisions, including those involving immigration and protection matters. The abolition of the IAA is particularly welcome. The aging AAT was beset with a variety of problems that are worth revisiting as we turn in conclusion to reflect on how the ART has been constructed going forward.

In his press release on 16 December 2022 the Attorney General complained that the previous government had ‘irreversibly damaged’ the public standing of the tribunal by appointing a great many poorly qualified individuals with political connections without any merit-based selection process, thus undermining the Tribunal’s ‘independence and erod[ing] the quality and efficiency of its decision making’.Footnote 116 This view is supported by a longitudinal analysis of AAT decisions undertaken by the Kaldor Centre Data Lab on the impact of the politicisation of appointment on decision-making outcomes.Footnote 117

Another problem with the AAT was that attempts to create a generalist tribunal in 2015, amalgamating specialist bodies dealing with social security, migration, protection issues and other matters, was poorly executed. The patching in of the IAA into the mix further complicated an already confusing and messy mix of procedural systems. The point to be made here is that where procedures for a central tribunal are set out in separate cognate Acts such as the Migration Act, it is much easier for bureaucrats and Ministers to change the legislation in response to a particular decision or series of decisions. This is demonstrated clearly in the reactive changes made to the Migration Act over time in areas such as notification of decisionsFootnote 118 and criminal deportation generally.Footnote 119 Far fewer changes have been made to the AAT Act over the timeframe of our study than have been made to the Migration Act.

Our concern is that the ART Act and Consequential Acts double down on the false premise that separate, and more restrictive procedures are needed in the migration and protection jurisdictions to increase efficiency. Our analysis suggests that, historically, the increased codification of procedures and other restrictive procedures has not increased either efficiency or fairness. Accordingly, it is our view that the maintenance of bespoke procedures is unlikely to serve the new tribunal’s objectives. This approach may in fact have the opposite effect, contributing to both inefficiencies and unfairness for applicants. The retention of stricter, shorter deadlines and the exclusion of common law natural justice may perpetuate many of the issues that were faced by the MRD of the AAT.

We are not alone in believing that the codification of tribunal procedures in the Migration Act has done little to increase the supposed efficiency and certainty of decision-making.Footnote 120 As we have shown, historical attempts at codification have often been rendered ineffective by judicial interpretation. It has been said that the codification of both decision-making procedures and judicial review in the Migration Act has been ‘undermined’,Footnote 121 ‘weakened’Footnote 122 and ‘outlived [its] usefulness’.Footnote 123

It has also been argued that the introduction of the procedural code complicated the relationship between the courts and the legislature by heightening the tension between their respective roles.Footnote 124 This has led to complex litigation and extended delays, ‘causing enormous difficulties’ for decision-makers, applicants and the courts.Footnote 125 In SZEEU v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs Weinberg J expressed his discontent with the procedural code in the following terms: ‘codification in this area can lead to complexity, and a degree of confusion, resulting in unnecessary and unwarranted delay and expense…. The cake may not be worth the candle’.Footnote 126

In addition to commentators and the courts, critique of the procedural code has come from the migration and refugee tribunals themselves. In 2009, Denis O’Brien, the Principal Member of the MRT and RRT called for the repeal of the separate procedural code as ‘the source of much unproductive and unnecessary litigation.’Footnote 127 In a joint submission to the 2012 Administrative Review Council review into federal judicial review in Australia, the MRT and RRT argued that the code had not improved the quality of decision-making, stating:

The experience in the migration jurisdiction has been that codification aimed at supplanting the natural justice hearing rule has distinct limitations. Although the codification of procedure may have the advantage of setting out a framework for the parties, experience shows that it leads to unexpected interpretation, uncertainty and extensive litigation. […] The amount of litigation surrounding the procedural codes in the migration context demonstrates that codification far from ensures certainty and the Tribunals’ experience is that the codes do not necessarily guarantee procedural fairness. Statutory codes of procedure, whilst providing a framework for the parties, cannot replicate the adaptiveness of common law procedural fairness.Footnote 128

In 2022, AAT Deputy President Jan Redfern expressed similar views of the resource and efficiency implications of the codified natural justice hearing rule for migration and protection visa matters.Footnote 129

The codification of judicial review in Part 8 of the Migration Act has also been criticised for adding to the complexity of litigation, and there have long been calls for its repeal.Footnote 130 In 1996, two years after the Migration Reform Act came into force, Crock called the restrictions on judicial review a ‘retrograde step’Footnote 131 that was ‘not justified by the available (hard) evidence.’Footnote 132 In 2009, Robyn Bicket, Chief Lawyer Department of Immigration and Citizenship, acknowledged that the migration reforms had ‘largely been unsuccessful’ and ‘controlling the volume of immigration litigation will be a continuing battle.’Footnote 133 Fifteen years later, commentators continue to highlight that the effect of codification in the Migration Act had been widespread uncertainty and increased litigation.Footnote 134

Our analysis suggests that there is no evidence that restrictions on procedural rights at the tribunal level increase either efficiency or certainty in decision-making. This is particularly the case when data is viewed in the broader context of the federal judicial review system. On the contrary, separate procedural codes seem to undermine the fairness and certainty of decision-making. They may be contributing to delays in the system.

A foundational element of Australia’s constitutional design is the separation of powers between the federal courts, and the legislature and executive. This is complemented by the constitutionally entrenched right to access to judicial review of government decision-making.Footnote 135 The federal courts have rightly taken a strict approach to ensuring that migration and protection visa applicants have access to procedural fairness and have an adequate opportunity to put forward their case and respond to adverse information. In light of these checks and balances, legislative attempts to achieve efficiency through restrictions and codification of procedural rights have and will likely continue to fail. Our findings in this regard align with the broader theoretical literature on civil litigation, which argues that fairness and efficiency must be pursued in balance with one another.Footnote 136 Numerous studies from Australia and abroad have shown that the best way of enhancing efficiency, particularly in the context of refugee cases, is through robust procedural safeguards that ensure applicants are supported in being able to put forward and articulate their claims for protection.Footnote 137 The best way to achieve this in the Australian context is to unify hearing mechanisms across the ART, removing separate procedural codes in cognate Acts such as the Migration Act.

Our concluding point is this: if our analysis in this article is impressionistic, it is because we have limited availability to relevant data. If poor data is so often an issue for researchers, the Department of Home Affairs has access to data needed for a more targeted and robust study of cause and effect in decision making. In this regard we echo the Law Council of Australia’s recommendation that the Department ‘provide a stronger justification for the proposed retention […] of a codified natural justice procedure in the Migration Act, with specific regard to the ART Act’s reform objectives of fairness, efficiency and accessibility’.Footnote 138 With recent developments of computational approaches, we live now in an age where it is possible to automate the collection and analysis of large and complex data sets.Footnote 139 Given the human and resource implications of tribunal decisions in migration and protection jurisdictions, we believe that the onus is on government to show why it makes any sense to maintain immigration as an area of exception. We cannot see that it does.

Appendix

Table A1. Judicial review of decisions made under the Migration Act

a Department of Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs, Annual Report 1989-90, 232; Department of Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs, Annual Report 1992-93, 283-4. b Mary Crock, ‘Judicial Review and Part 8 of the Migration Act: Necessary Reform or Overkill?’ (1996) 18(3) Sydney Law Review 267, 289. All other data is taken from the Immigration Review Tribunal, Migration Review Tribunal, Refugee Review Tribunal and Administrative Review Tribunal Annual Reports.

* Refers to applications from the Refugee Review Tribunal between 1993-4 and 2014-15, and Refugee cases within the AAT MRD between 2015-16 and 2023-24.

** Refers to applications from the Immigration Review Tribunal between 1992-93 and 1998-99, the Migration Review Tribunal between 1998-99 and 2014-15, and the Migration cases within the AAT MRD between 2015-16 and 2023-24.

Table A2. Remittal and set aside rates for judicial review cases of IAA decisions

All data is taken from the Administrative Review Tribunal Annual Reports.

Table A3. Proportion of IAA decisions lodged for judicial review

All data is taken from the Administrative Review Tribunal Annual Reports.