How a Wunderkind Became Hungarian

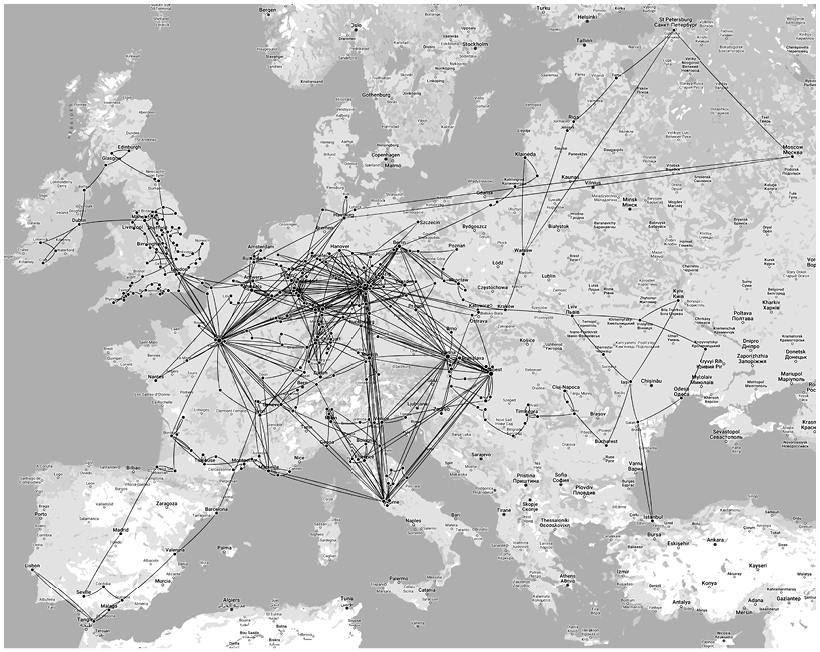

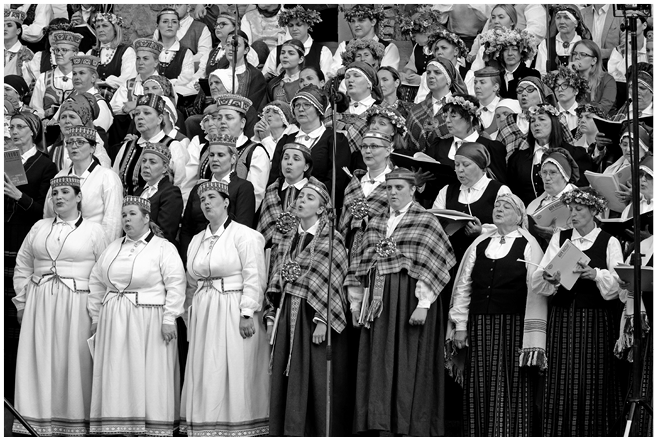

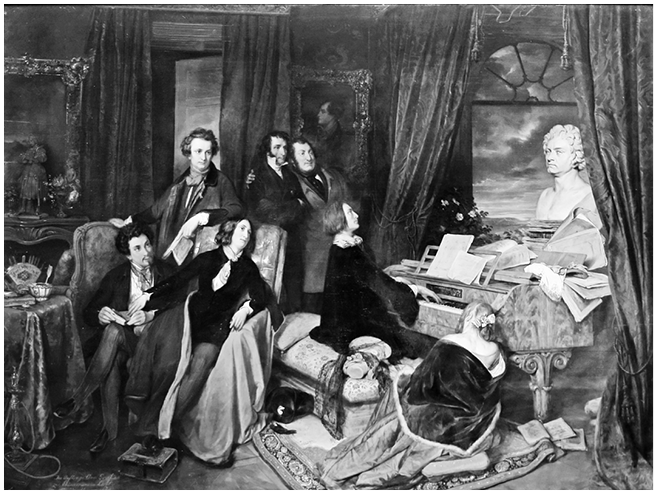

The 1840 painting in Figure 9.1 shows an imagined matinee recital by Franz Liszt. By now the imagery may appear familiar: the enraptured audience listening to an inspired performance is very close to the listeners in the roughly contemporary painting of Rouget de Lisle singing ‘La Marseillaise’ (Figure 1.3), and the transported gaze of the inspired performer, gazing upwards into the distance, resembles that we have seen in the pictures of Ossian and of the guslar (Figures 3.1 and 5.1). Liszt’s audience are the fine fleur of Parisian Romanticism at the time: swooning on her chair on the left is George Sand, seated next to Alexandre Dumas; standing behind them are fellow composers Berlioz, Paganini and Rossini, looking knowledgeable and appreciative. Reclining next to the piano, and seen from behind, is countess Marie d’Agoult, Liszt’s patron and long-term companion. (Although she and Liszt never married, they had three children together, one of whom, Cosima, would later marry Richard Wagner. D’Agoult herself wrote and published under the pen name ‘Daniel Stern’.) To add to the clear sense that we are in a locus of concentrated Romanticism, there is a bust of Beethoven on the piano, a portrait of Byron on the wall and a statue of Joan of Arc on the far left.

Figure 9.1 A Matinee Performance by Liszt (Josef Danhauser, 1840; Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin).

Besides hinting at the importance of the salon as a hothouse for artistic and intellectual innovation, the painting also documents the flourishing of the Romantic virtuoso as a cultural and social phenomenon. The painting was commissioned by the Viennese piano manufacturer Conrad Graf, an important builder during the time when the grand piano was becoming the instrument for large-scale concerts, with expanded octave range and improved tonal power. Graf built pianos for Beethoven, Chopin and Clara Schumann, and Liszt is here shown (in what is almost a product placement) playing a Graf. Ironically, Liszt’s violently passionate performance style is said to have destroyed two Graf pianos in Vienna.1

As the piano evolved into a ‘grand’ power instrument, the virtuoso piano player became increasingly a public superstar, and Liszt was among the most celebrated of them all. Virtuosi – technically accomplished performers who would give concerts to paying audiences on tour – can be traced back to the early eighteenth century, but the child prodigy Mozart had marked a leap forward, followed by Chopin and the violinist Paganini. Between them, Mozart, Chopin and Liszt mark the onset of the heyday of musical Romanticism, with the definitive emancipation of music from the patronage of nobility and courts and its development into a public and commercially financed art form with superstar celebrities.2

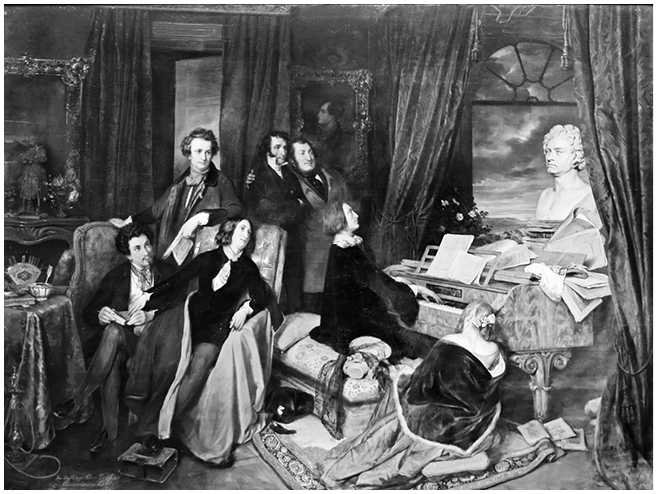

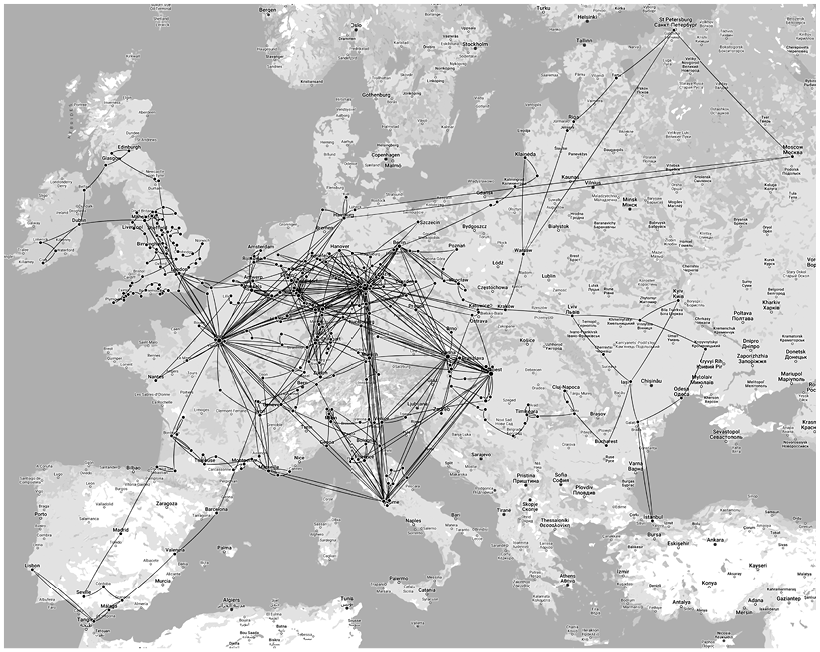

Liszt, like Mozart, had started his career as a Wunderkind. (The cult of the child prodigy was part of the Romantic fascination with art as something untaught, naturally inborn; it helped young Schubert and Chopin to fame at a very early age.) Born in 1811 near what is now the Hungarian–Austrian border, and having made an early start in Vienna, Liszt moved to Paris with his mother at the age of twelve to pursue his musical training and career. There he soon became part of a network of Romantic musicians and composers; they were of many nationalities (including Italians and Germans), gathered in what was the cultural metropolis not just of France but of much of Europe. From Paris he would undertake many concert tours. Liszt was, in other words, a wandering cosmopolitan, and the tracks of his lifelong concert tours between 1818 and 1886 enmesh all of Europe like a spider-web (Figure 9.2).

At the time when the painting of his salon performance was commissioned, Liszt had been in Italy for two years, just then parting ways temporarily from his companion Marie d’Agoult. The news of a Danube flood in Budapest had brought Hungary to mind; he travelled to Vienna to perform at a benefit concert for a flood-relief fund and from there moved, for the first time since his early boyhood, into Hungary: by way of Bratislava/Pressburg his journey led to Budapest, where he performed in early January 1840.3

The concert was a triumph. As Liszt later wrote, ‘Everywhere else I perform for an audience, however in Hungary I address the nation!’ The leading national poet Mihaly Vörösmarty dedicated a poem to him after the concert, asking him to awaken once again through his music the spirit of the ancestral tribal leader Árpád. Huge crowds, shouting Eljen! Liszt Ferenc! (‘Hail, Franz Liszt!’, calling him by his Hungarian name-form), greeted him rapturously and welcomed home the most celebrated Hungarian of his day as a long-lost son. Liszt returned the favour: the concert was full of patriotic gestures. Most significantly, Liszt performed the Rakoczi March, which, linked as it was to the rebellious nobleman of that name, had been banned by the Austrian censors. He also wore the Hungarian national costume on stage (a tight long-waisted ‘Attila’ waistcoat fastened with embroidered frogs-and-loops rather than buttons), and to top it all he was presented on-stage with a ceremonial sabre of honour.

Receiving this sabre symbolically inducted Liszt into the Hungarian nobility, and that meant a great deal. At the time, Hungary was still an almost feudal class society with the nobility enjoying and insisting upon its ancient established privileges, not least of which was the ‘right to bear arms’, symbolized by sword or sabre (still the marker of difference between commissioned officers/gentlemen and the enlisted rank and file). The Hungarian úriember (a ‘true/fine gentleman’ with dignity, bravado and poise) cultivated a sense of aristocratic honour, which during these years began to overlap with a sense of national pride: Hungarian Romantic nationalism was Byronic, chivalric, based on a sense of nobility rather than on (civic) virtue. This affect was powerfully expressed in the great popularity of the sport of fencing, still a ‘national sport’ among Hungarians, and feeding into that national symbolism was the sabre conferred upon Liszt.4

When Liszt gave a speech of thanks – significantly, in French, since his command of Hungarian was insufficient – he showed himself keenly aware of the symbolic import of the moment. He pointed out that of old it had been the warriors and military officers who had buttressed the nation; in these modern days, he suggested, that role was also taken up by the likes of himself, by the arts, literature and science. Even so, he concluded, if the need arose he would be willing to let the sabre ‘be drawn again from the scabbard’, in readiness to ‘let our blood be shed to the last drop for freedom, king and country’.

Pathos and grandstanding; but no doubt sincerely felt both by the audience and by Liszt himself, Romantics one and all. Liszt now placed his art in the service of his rediscovered fatherland and felt that this artistic nationalism was the equivalent of doing battle in arms. Liszt wore the sabre on numerous occasions, but not in 1848, when Hungary was actually rising in arms to assert its independence from the Habsburg crown. The sword that significantly failed to be drawn from the scabbard earned Liszt a withering piece of sarcasm from Heinrich Heine and often featured on caricatures of the performing virtuoso.5

But Liszt did henceforth place his art in the service of his country. He did wear the sabre as a symbolic gesture when he performed his Funérailles elegy in 1849, turning that piece of musical lyricism into a political statement. The work’s subtitle, October 1849, referred not only to Chopin’s death that month but also to the execution of thirteen Hungarian insurrection leaders. What is more, the piece used the ‘gypsy scale’ (with augmented seconds) as a marker endorsing Hungarian nationality. Liszt’s turn to composing nationally Hungarian music (most prominently, of course, the Hungarian Rhapsodies), was deeply inspired by that remarkable aspect of Hungarian cultural life, the popularity of ‘gypsy’ music played by bands of Romany performers. Their musical style, with its augmented seconds and fourths and its sprung rhythms and syncopations, lay outside the established, conservatoire-taught classical palette. By incorporating it into his own compositions, Liszt emphasized his national rootedness and at the same time expanded the horizons of his composing technique.6

‘Gypsies’, Rhapsodies and the National Turn

Liszt in fact used the trip (and later return trips) to do fieldwork among Romany musicians, many of whom were employed as occasional providers of entertainment or were (as such) part of the retinue of noblemen. The results of this are noticeable in his later, nationally Hungarian compositions. And he even reflected on this in an extensive essay that was published in book form in 1859, in what was still his primary language: French. The title was Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie. In it, Liszt tackled the odd circumstance that Hungarian national music was in fact from outside the Magyar cultural tradition, belonging as it did to those wandering Romany communities known variously at the time as Tziganes, Gypsies, Zigeuner or Bohemians.Footnote * As Liszt argued, it was only in Hungary that such Romany musicians could enjoy the steady patronage of the sedentary Magyar population, and as a result Hungarian music culture was bicultural, born of the happy integration of Romany music into Magyar society. There is some fond Romanticization in this, and what is also plain is that Liszt personally identifies with his ‘bohémiens’. He credits them with temperamental attributes that also apply to himself as a Romantic. He himself was a nomad, only lately adopted by his fellow Magyars. He lived the ‘bohemian’ lifestyle, spurning the niceties and social conventions of the settled bourgeoisie, living hand-to-mouth, dedicating himself to his own inspiration and wayward emotions. As ‘gypsies’ were becoming a projection screen for middle-class wanderlust and anti-conformism (to live in a caravan, outside the norms of societies, on a lifelong road trip, hippies avant la lettre), Liszt with his bohémiens established the link between the allure of cultural exoticism and the Romantic notion of the bohemian artist. (The downside of this idyllic idealization of Romany culture is a strident note of anti-Semitism: wandering and non-territorial like the Romany, and in those respects their counterparts, Jews are, in Liszt’s book, culturally noxious, living a life of dour legal observances rather than passionate freedom.7)

Liszt fitted his ‘gypsy’ interest into the philological stadialism of his day and age (see Chapter 4). He saw performative Romany culture as something that had not yet crystallized into a proper self-aware and self-reflecting culture, as yet abiding in the preliminary developmental stages of finding its own cultural voice. Like the guslars of the Balkans, the Romany were ‘rhapsodes’: those wandering pre-Homeric poet-performers whose fragmentary lays required a Homer to be given durable shape and form. This, in short, is what Liszt proposed to do with Romany melodies: his compositions would weld and structure them into a coherent corpus, consolidate them into a robust foundation for a future cultural presence. The use of the word ‘rhapsody’ is anything but fortuitous: it was deliberately chosen by Liszt in full awareness of the philological implications and the discussions of the literary roots of national self-articulation, involving the Homeric Question and the guslars of the Balkans:

Under the pleasant Grecian sky, wandering rhapsodes gathered around them the inhabitants of towns and hamlets to make them listen to the stories of vanquished nations and toppled kingdoms, or adventurous voyages. Their chants, once collected into a homogeneous work by old Homer, formed an inimitably perfect monument

After Liszt, the rhapsody emerges as a new musical form. If anything, it is a formless form, a free succession of melodic themes and elaborations – much more fluid than the structured classical forms of concerto, sonata or symphony. In exploring this new, loose and more lyrical musical form, Liszt followed the example of Chopin with his nocturnes, mazurkas and polonaises. Chopin had also used these formal innovations to accommodate the vernacular ‘folk’ traditions of his homeland: the polonaise was a fast, cheerful Polish dance, and the name of the mazurka echoed its region of origin around the Mazurean Lakes. Following Liszt, the rhapsody would become the premier form for the expression of a sense of nationality in lyrical–musical form. A list of more than ninety of such rhapsodies is included in the Appendix at the end of this chapter (Tables 9.1a, 9.1b and 9.1c), ranging from Aragonese and Armenian to Umbrian and Welsh, and from 1846 (Liszt’s prototypical Hungarian ones) to 1940.8

The rhapsody was the genre that spearheaded a general ‘national turn’ in classical music. Much as in academic painting, music had gravitated towards a ‘classical’ standardization of forms and instruments in the course of the eighteenth century. Gluck aimed for a musical style that would appeal to audiences everywhere ‘so as to abolish the ridiculous difference between nations’.9 Although some national inflection persisted in England and France in the wake of Purcell and Lully, the universal standard became Italian, as we can see from the still prevailing use of Italian for music’s technical vocabulary, from meno piano and coda to allegro moderato and da capo. From this Italian standard, a Viennese–German tradition branched off from Mozart on; between Beethoven and Brahms, German became the new default for ‘classical’ music (though less so for opera than for symphonic genres and chamber music). With Chopin and Liszt, we begin to notice a trend where composers seek their inspiration outside the Italo-German classical bandwidth, notably in the vernacular cultures of their native countries. That national turn was often a matter more of presentation than of substance: titles and narrative themes rather than melodic lines or harmonic chord progressions. At best we see a nod to the use of rustic instruments, dance rhythms or the occasional parallel fifth or drone bass. But as with spices in cookery, small doses go a long way to give music a ‘national’ flavour. The trend persisted and intensified throughout the second half of the century, and affected all of Europe: from Albéniz in Spain to the ‘mighty handful’ in Russia (Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin), from Elgar in England to Enescu in Romania, from Grieg, Nielsen and Sibelius in the north to Smetana and Dvořák in the centre. Vaughan Williams and Tchaikovsky drew on native stylistic elements from Anglican and Orthodox plainchant respectively. Others turned to folk music, its modal or pentatonic scales, drone bass and sprung rhythms.10

These were all inflections and tentative expansions on the conventions of conservatoire-taught classical music as performed on the established symphonic instruments; but towards the end of the nineteenth-century composers such as Manuel De Falla, Igor Stravinsky and Béla Bartók would go further by using folk elements for avant-garde experimentation. By 1934, Vaughan Williams, in his treatise National Music, asserted the need to ‘cultivate a sense of musical citizenship. Why should not the musician be the servant of the state and build national monuments like the painter, the writer, or the architect?’11

What is remarkable is, here as elsewhere, the universal spread of national particularism. Much as in the Europe-wide genre painting of young peasant women (depicted in standard poses and techniques, and nationalized through the accessories of clothing or background and the painting’s title; more on this in Chapter 10), so too music used a fairly common reservoir of ‘vernacular’ stylistic elements to go national. Here as in history painting, the extent to which ‘nationality’ can be a generic additive is illustrated by the fact that it often goes in tandem with oriental exoticism: anything ‘colourful’ from outside the Italo-German classical style is exploited. Grieg inserts a sultry oriental ‘Anitra’s Dance’ in the middle of his Peer Gynt suite; Rimsky-Korsakov composed, amidst his more Slavic-style works, a ‘Capriccio Espagnol’. The Hispanicism of Ravel is more entangled between exoticism and self-identification: he hailed from the French Basque country, and his Basque mother had grown up in Madrid. National music becoming transnationally entangled is best illustrated by Antonin Dvořák’s stint in New York (1892–1895), where he was initially commissioned to write a national American opera. A theme that offered itself for such a work was the Hiawatha poem by H. W. Longfellow. As has been mentioned (Chapter 5), Hiawatha revolves around the legendary and imperfectly understood Iroquois leader of that name and also drew on Ojibwe traditions as collected by Henry and Jane Schoolcraft. But Dvořák, thanks to his New York encounter with the African-American composer Harry Burleigh, was more deeply inspired by the musical style of spirituals as sung by enslaved Black plantation workers. In the event, the opera never materialized, and Dvořák recycled various ‘national’ American materials in his ninth symphony From the New World (1893).12

The metropolitan traditions that had little or no distinct vernacular palette to make use of relied on thematic ‘framing’ to nationalize their work; one can also think of the Flemish cantatas of Benoît Peeters and the symphony To My Fatherland (1888–1890) of the Dutch Wagnerite Bernard Zweers, with its four movements entitled ‘In the Forests of the Netherlands’, ‘In the Countryside’, ‘At the Beach and at Sea’ and ‘To the Capital’. Such explicit titles are characteristic of ‘programme music’, where the composer in programme notes furnishes an explicit guide to what the music is intended to convey and how it is to be listened to. That programme often explicitly imposes a concrete, national frame of reference on abstract melodic lines, harmonic patterns and evolving structure. Smetana programmatically subtitled his famous ‘Vltava’, a movement of the suite Ma vlast, ‘My Country’, to evoke the course of Bohemia’s Vltava (Moldau) river as its bubbles up from its two springs, eddies through picturesque forests and along idyllic meadowlands, elf-haunted at night, foaming through rapids and majestically welcomed to Prague as it flows past the hallowed haunt of the legendary Libuše, the Vyšehrad hill (see Chapter 7).13

Audience, Participation, Festivals

Libuše herself was the title heroine of the Czech national opera par excellence, also by Smetana (1872); its culminating aria was the princess’s prophecy of the future glories of Prague. The opera was used to inaugurate Prague’s new National Theatre in 1888. As this case indicates, the most strongly programmatic music, with the greatest nation-building potential, was opera with its libretto. In Hungary, Ferenc Erkel evoked the kingdom’s past heroes (Hunyadi László, 1844; Bánk bán, 1861). In Russia, Glinka (A Life for the Tsar, 1836) and Mussorgsky (Boris Godunov, 1874, after Pushkin), thematized episodes from the ‘Time of Troubles’ around 1600; Borodin’s Prince Igor (1890) set the ancient national epic rediscovered around 1800 to music.14 French, Italian and German audiences were given operas on strongly national themes by the likes of Giacomo Meyerbeer (Les Huguenots, 1836) Giuseppe Verdi (I Lombardi, 1843) and Richard Wagner (Die Meistersinger, 1868; the Ring cycle, 1869–1876).15 Such grand operas were society events. Audiences could actively intervene in the performance (outside the reverential high-mindedness of Wagner’s Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, that is) and in some instances even exploded into national demonstrations. The performance of Auber/Scribe’s La muette de Portici, with its aria ‘Amour sacré de la patrie’, sparked off anti-Dutch clashes in Brussels and, ultimately, the Belgian Revolution of 1830. The rejection of Wagner’s Tannhäuser by Parisian audiences in 1861 was a nail in the coffin of French–German relations.

The case of Verdi deserves special mention. As a composer, his name is linked to the Risorgimento period, when his work was the figurehead of Italian culture before the unification of a sovereign Italy. The ‘Va Pensiero’ chorus of his Nabucco (describing the home-yearnings of the enslaved people of Israel in their Babylonian captivity) became a transnational hymn symbolizing the plight of oppressed people and diasporas everywhere. In 2013, when the opera was performed as a ‘national classic’ for the 150th-anniversary festivities of the Italian state, the chorus met with frenzied acclaim from the audience, to the extent that director Muti granted an encore, which he prefaced with a speech denouncing the Berlusconi government. During the encore, the audience threw down a confetti of shredded paper from the balconies; that gesture was overtly reminiscent of Visconti’s film Senso (1954), in which a Verdi opera in Habsburg-dominated Venice becomes the occasion of insurrectionary pamphlets being thrown from the upper balconies.Footnote *

This indicates that music was not just the mystical, trance-like affair that the Liszt painting shown at the beginning of this chapter evoked. Certainly in the case of operas, the audience did not sit spellbound as in a séance or religious service, but engaged actively; audience favourites were encored, sung along with; the sheet music was marketed for private or convivial performance. For this was also the great century of amateur music, of parlour and chamber music, and above all the century of the choir. Music was also something that was performed collectively, and the collectivity of the performance created a shared affect and sense of togetherness – often a national one; and as such, music played into the century’s festival culture, as outlined further on in this chapter and Chapter 10. In the growth of Hungarian nationalism, the national-historical operas of Ferenc Erkel exercised greater mobilizing power than even the concerts of Liszt.16

Convivial singing emerged from religious and pedagogical practices around 1800, in and around churches, masonic lodges and student fraternities.Footnote ** Two prototypes were the French-style orphéon and the German-style Gesangverein or Liedertafel. From Wales to Catalonia and from the Basque Country to the Balkans choirs proliferated as part of religious, educational, agricultural, civic or industrial sociability. The spread was ‘reticular’: local models and activities, usually in towns and cities, inspiring similar ones, franchise-style, in other towns/cities. Choirs were spawned not just by the social conditions of the time but also by each other, by following the example of other choirs, and in turn setting the example for other ones again. In contrast to this ‘reticular’ spread, with separate, locally distinct but mutually inspired associations and initiatives being sparked off across the map, the repertoire was diffused nationwide: sheet music was available throughout the country as a single, locally undifferentiated corpus.17

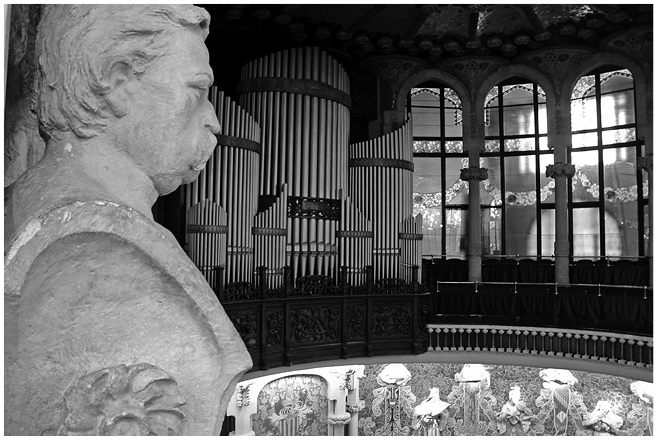

Patriotic choruses became popular in France after 1789, with composers such as Méhul (‘Chant du départ’, 1794), Gossec, and Louis Bocquillon (known mainly under his soubriquet ‘Wilhem’). In 1806, Bocquillon introduced choral singing as an educational method; the support of the popular songster Béranger allowed him to propagate it as the ‘Méthode Wilhem’ from the 1820s on. Concert performances by school pupils followed as a matter of course. In 1833 these solidified into a Paris-based performance organization called L’Orphéon. From there, choral societies multiplied across France and the name ‘Orphéon’ became a generic label for a society of musical amateurs. From the late 1830s onwards, local choirs would also give concerts further afield. The Chanteurs montagnards of Bagnères-de-Bigorre first scored successes in Paris and then went on a tour including Alexandria, Istanbul and Moscow. Orphéons manifested themselves in public life on civic occasions and with festivals. A large international festival was held in Asnières in 1850. (Its ‘international’ nature was exclusively owing to the participation of choirs from Belgium.) By the end of the 1850s, there were 700 orphéon associations in France. Provincial festivals proliferated and concerts raised great numbers of spectators; a crowd of 50,000 assembled on the Place de l’Opéra for an open-air concert by a Spanish tuna in 1878. In these years, the repertoire seems to have become markedly more French and patriotic; staples were Méhul’s old ‘Chant du départ’ and a composition by Ambroise Thomas entitled ‘France! France!’ The movement also spread south of the Pyrenees: markedly so in Catalonia (thanks also to the important work by Josep Clavè, Figure 9.3) and Galicia, but also in other parts of Spain, where by 1910 more than twenty orfeones were active. English pedagogues translated the Méthode Wilhem into English (1841). Although choral singing in that country had a different origin and social base (Anglican parishes and, later in the century in the industrial areas, trade unions), there was some influence from the French model when it came to the organization of festivals: 137 orphéons, with a total of 3,000 members, gave a concert in London’s Crystal Palace in 1860.18

Figure 9.3 Bust of the choral conductor and composer Josep Clavè in the art nouveau Palace of Catalan Music, Barcelona.

Meanwhile, in a parallel development, a no less powerful choral movement had sprung up in Germany. Its reticulating proliferation emanated from two hubs: the bourgeois cultural sociability of 1808 Berlin and the patriotic Protestantism of 1810 Zurich. In the north, the prototype was the private Liedertafel established in Berlin in 1808 by Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832), friend of Goethe, musician and instigator of the German Bach revival. Zelter’s Liedertafel was copied within Berlin and in other Prussian and north German cities, as well as in the Prussian Rhineland. In the south, the first such initiative, by the composer and music publisher Hans-Georg Nägeli in Zurich in 1810, prompted widespread dissemination. Like his French counterpart Wilhem, Nägeli was also a musical pedagogue; his educational use of music was inspired directly by Pestalozzi, for whom he published a Gesangbildungslehre nach Pestalozzischen Grundsätzen in 1810. Nägeli visited Stuttgart on a lecture tour in 1819–1820, during which he promoted the male choir as the ideal interface between popular sociability (Volksleben) and aesthetic education. The choir established in Stuttgart in response to Nägeli’s model became a prototype for similar choral societies (initially male-only) in Germany’s southern parts, replicating rapidly and widely in the 1820s–1840s. As of the late 1820s the two types began to overlap (especially in Franconia and the Rhineland) and merge. Their success may in part be explained by the fact that they could draw, for their membership, on university alumni who had been introduced to convivial singing as part of the culture of student fraternities (Burschenschaften).19

The reticulating spread in Germany was two-tiered, involving first a regional and then a federal level. An association between the choirs of Hanover and Bremen formed the nucleus of the League of United North German Choirs in 1831; it attracted other local choirs and organized a series of regional festivals; these intensified in the 1830s–1850s. Similar patterns were at work in Bavaria, Thuringia and Franconia; and these federations in turn entered into a nationwide meta-federative league in 1860. Pan-German festivals were regularly held from the mid-1840s onwards, and officially as Bundessängerfeste, for example in Nuremberg in 1860 and in Breslau/Wrocław in 1907. Thus the organizational history of these choirs in a sense offered a template of Germany’s political unification. As the choral movement became pan-German, so did, with some delay, Germany itself.

What was also pan-German was the repertoire. The sheet music was printed and sold across all German-speaking lands and states and created a culturally continuous ambience among them. As with students’ songbook anthologies (Commersbücher), much of the repertoire was nationalistic, expressing patriotic sentiments that at the time were seen as uncontentiously inspirational and uplifting. A Commersbuch would contain songs celebrating merry conviviality, nature (including the joys of hiking or hunting), the winsome daughters of innkeepers here, there, and everywhere, and also the higher virtue of patriotic feeling. Those registers could be spliced together: many a song celebrating the communal quaffing of Rhine wine would extol the German fatherlandish qualities of the Rhine region and its vineyards. The song ‘Der Jäger Abschied’ (‘The Huntsmen’s Farewell’, also known as the ‘Waldhymne’ or Forest Hymn), by Mendelssohn, had words by Eichendorff and followed that poet’s characteristic lyricism, combining religious awe and love of nature; there were few or no overt nationalist connotations. But it was one of the highlights of the 1846 Cologne Song Festival, a fervently nationally minded occasion held in the aftermath of the Rhine Crisis (1840) and the looming of the First Schleswig-Holstein War.Footnote * In this context the ‘Huntsmen in the Forest’ hymn (directed by Mendelssohn himself, who had been engaged for the occasion) became a figure of Germanity. The song was included in a songbook published 1848 with the telling title ‘Germania: A Garland of Liberty Songs for German Singers of All Estates’.20

In the years of the Napoleonic hegemony, songs had become a political weapon. Arndt’s song ‘Was ist des Deutschen Vaterland’ and Körner’s ‘Männer und Buben’, effective propaganda in 1813, had become politically suspect in the reactionary 1820s (with Arndt himself dismissed from his university post in Bonn for ‘demagoguish’ tendencies). It was in this period that the students of the 1814 cohort, after graduating, withdrew into the family life of solid citizenry that would in course become the main recruiting ground for choirs and gymnastic clubs.21

The patriotic songs of more radical times were kept alive and ultimately gained new respectability as they entered the repertoire of the German choirs after the Rhine Crisis of 1840; alongside old classics by erstwhile radicals such as Arndt and Maßmann (‘Ich hab’ mich ergeben’, ‘I have Dedicated Myself [to the Fatherland]’) new patriotic songs were included, such as Die Wacht am Rhein, by now familiar to the reader. Nicolaus Becker’s ‘Der Deutsche Rhein’, with its defiant verses (‘No, never shall they have it, the free, the German Rhine; even though like greedy ravens they hoarsely clamour for it’) inspired what was to become the Flemish national anthem, ‘The Flemish Lion’ (1847, by Van Peene and Miry): ‘No, never shall they tame him, the proud Flemish lion, even though they assail his freedom with fetters and with jeers.’ Such songs were meant to be sung together, in a rousing chorus and preferably (‘All together now!’) with the audience joining in.

Composers of note would occasionally throw their weight behind this wave of patriotic song, also as directors. Mendelssohn conducted choral festivals both in the Rhineland and in his second homeland, England. The Bernard Zweers whose name we have encountered as the composer of a symphony ‘To the Fatherland’ also aided in the production of a Dutch national song-book, Kun je nog zingen, zing dan mee! (‘If You Can Sing, Then Sing Along!’); its songs celebrated the coastal landscape, the can-do spirit of the great mariners of the seventeenth-century glory days and of the seafaring colonizers, and the stalwart ethnic brethren, the beleaguered Boers in Southern Africa.

The lyrics of those songs, Dutch, German or otherwise, were usually by B-list versifiers: Maßmann, Geibel, Felix Dahn. Their sentiments were hackneyed and combined stridency with the commonplace. As a result such songs could either be anodyne and ‘unpolitical’ or else fervently nationalistic. The Rhine songs of Schneckenburger and Becker remained on the repertoire long after the subsidence of the Rhine Crisis that had provoked them in 1840. At the National Song Festival of Nuremberg (1861), during a relatively peaceful period, the memories of 1813 (Arndt!) and 1840 (Becker! Schneckenburger!) were channelled when the massed German choirs roared fortissimo ‘And if the foe approaches, then a united Germany will march to the Rhine, to do battle for the Fatherland!’ The chorus line ‘Hurrah! We Germans, we march to the Rhine!’ was drowned in loud acclamations. The Franco-Prussian War was as yet ten years in the future; but it was foreshadowed and primed in the field of culture through this self-stoking, self-amplifying choral flag-waving.22

In Breslau in 1907, another Bundessängerfest of the German League of Choral Societies was held. The singers were welcomed by the pan-Germanist poet–professor Felix Dahn with a poem that, in English translation, runs like this:

Dahn’s verse was aimed at middle-class, middle-aged, suburban or small-town German males who once a week indulged in their leisure pursuit of choral singing with a glass or two of beer afterwards. But the self-image that it articulates and celebrates was far less anodyne: it addresses its audience as a convivial Bildungsbürger with a slumbering readiness to go berserk for the noble cause of the Fatherland. More importantly, the performativity (and, to be sure, a cheerful and merry performativity it was) rendered these songs uniquely memorable. Great art they were not, but they stuck in the mind. In 1848 Arndt’s song ‘Was ist des Deutschen Vaterland’ earned him, thirty-five years after its composition, a vote of thanks-by-acclamation in the Frankfurt National Assembly.24 This scene is remarkable not only for the importance of Romantic cultural enthusiasm in the assembly’s political deliberations, but also for the total, unargued and self-evident obviousness with which everyone was familiar with Arndt as, first and foremost, the composer of a song that was universally recognized and acknowledged as a potent force in public life. This, it should be noted, was wholly due to its informal popularity at grass-roots level: a bit like ‘Auld Lang Syne’ or ‘O Tannenbaum’.Footnote *

A century later again, in another parliament, this time in Bonn, the assembled delegates had at their fingertips another patriotic song that they could use as an impromptu national anthem. By 1949, Hoffmann von Fallersleben’s ‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’ had become compromised and even been proscribed; but the delegates, gentlemen with student backgrounds one and all, had learned from their Commersbücher Maßmann’s ‘Ich hab mich ergeben’, and that was intoned, as part of an ingrained national repertoire, in the first parliamentary meeting of the new Federal Republic.

The point is not to single out Germany as a uniquely nationalistic special case. Charting the omnipresence of ‘La Marseillaise’ in French history, or ‘The Flemish Lion’ in Flanders, or ‘A Nation Once Again’ in Ireland, or ‘Dabrowski’s Mazurka’ in Poland, would offer an instructive counterweight. And in England, there was the Last Night of the Proms. By 1895 it was felt that English musicianship had at last caught up with that of the Continent and that the general public should profit from its achievements; and to that end a series of informal concerts was established in the newly constructed Albert Hall, the so-called Promenade concerts or Proms. The direction was entrusted to the organist/composer Henry Wood, who had previously produced Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. His patriotic Fantasia on British Sea Songs (1905; a medley of traditional shanties arranged orchestrally to celebrate the centenary of the Battle of Trafalgar) became an early fixture of the popular Last Night, which gradually also incorporated other national classics, from Arne’s older ‘Rule Britannia’ to Elgar’s ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ march (‘Land of Hope and Glory’). By 1918 the repertoire of nationally inspired and nationally inspiring songs also included ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’ and Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ as set to music by Hubert Parry, and Cecil Spring-Rice’s ‘I Vow to Thee, My Country’, staple of royals weddings and funerals. The melody is so appealing that the lyrics, written at the close of the Great War, become secondary, mere syllables to carry the tune, commonplace phrases intoning an ambient patriotic piety.Footnote * Yet in all their unpolitical unobtrusiveness they are worth noting for their strident fanaticism, which breathes the same fey battle-readiness we saw in the German case of Felix Dahn.

It is this repertoire that has turned each ‘Last Night of the Proms’ into a massive, festive flag-waving occasion. Flag-waving, literally: at first, Union Jacks were brandished and waved around (with what degree of national earnestness or cheerful irony, it is impossible to tell); during the Brexit debates, a minority of European flags was in evidence (which sparked comments and debates). The point is that convivial cheer can cloak national fervour in good-humoured pleasantry and provides nationalism with the pretext, or antidote, of irony; this makes the Last Night of the Proms a good interpretive lens for viewing the German Sängerfeste of the nineteenth century.

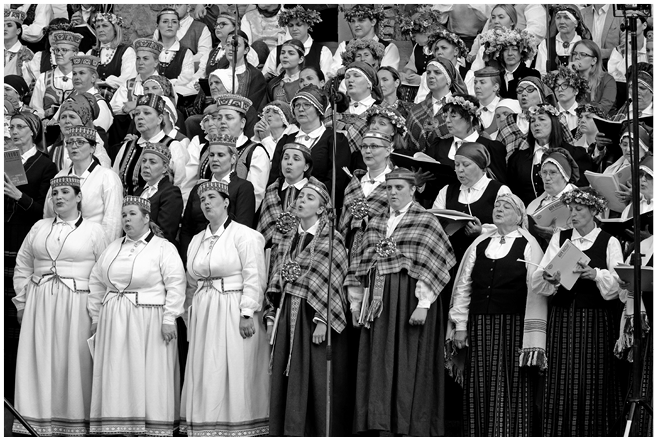

The most intriguing cultural transfer in this field occurred in the ethnically mixed territories of Central Europe, especially in the Baltic area. Here, cities with a strong German presence had their choral societies as a matter of course: Königsberg, Breslau/Wrocław, Budapest. In Prague, a Liedertafel der deutschen Studenten was established at the Charles University in 1844. All these sparked off competitive imitations from the non-German (Hungarian, Slavic, Baltic) co-inhabitants of those cities. The most extraordinary repercussions took place in the Baltic provinces. Although they had come under Russian rule, city life in Riga, Reval/Tallinn and Dorpat/Tartu was still dominated by German townspeople, their culture and sociability. In 1851, German-style choirs (possibly inspired by the one in Königsberg) were founded in these three cities. The model of cultural-performative conviviality and the ‘embodied community’ proved ideally suited to the vernacular culture of the Estonian and Latvian populations, among whom consciousness-raising and nation-building processes were just beginning to emerge at that time. A first all-Estonian song festival was held in Tartu in 1869 to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Livonian peasant emancipation, with 845 singers and an audience of 10,000–15,000. The movement gathered in strength with further festivals held in 1879, 1880, 1891, 1894 and 1896; and from 1873 the cue was taken up by Latvians as well. The Baltic Germans had delivered the inspiration, the organizational design and the community-bonding and nation-mobilizing function; the native populations fitted these made-in-Germany vehicles with their own ethnic (Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian) payload (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 Participants in the Latvian national song festival in traditional dress, 2023.

Since then, these choral festivals have become huge, drawing thousands of choral singers, dressed in traditional costume, into enormous stadiums, and they have remained a powerful platform for the proclamation of national identity. They can draw on a widespread and deeply rooted cultural praxis: choral singing and the nationwide availability of a shared repertoire have become solidly entrenched in public life. At the end of the Soviet period, such gatherings fulfilled an important role in mobilizing anti-Russian national sentiment and popular resistance, their mobilizing power being so strong that this probably forestalled an armed intervention by Soviet forces in 1989. This ‘singing revolution’ is now commemorated as the moment when the Baltic republics seized their freedom from Soviet rule. The national character of these festivals is heightened by the wearing of traditional dress (Figure 9.4), by the homeland-celebrating repertoire and by the sheer performative power of joining so many voices into a huge choral whole, an ‘embodied community’.26

Thus we have traced the power of music from the prestigious ambience of the symphonic concert hall to the grass-roots celebrations of mass festivals. Music was a powerful amplifier of affect, for the audiences both of Liszt and of Nabucco, and for the convivially singing performers and participants in Nuremberg, Tartu and the Albert Hall. The power of music can even penetrate into the very fibre of the individual’s emotions, as we saw when we discussed the effects of ‘Die Wacht am Rhein’ and ‘La Marseillaise’ in Chapter 1: it can make love of the nation overflow, not just among but also within people.

With that, we turn from the Romantic (early to mid nineteenth century) production of knowledge and culture into the mass-entertainment leisure-time culture of the next century. Choral festivals were not a unique phenomenon: as we shall see in Chapter 10, they arose concurrently with literary festivals (the eisteddfod in Wales, the jocs florals in Barcelona) and with sports and athletics festivals, and all of these profited, in drawing the necessary crowds, from increased mobility – railways, a tourism infrastructure. And the nation became not just an inspirational presence but also the enabling ambience and feel-good factor for modern leisure-time entertainment.