Introduction

The term ‘deliberative mini‐public’ was first introduced by Fung (Reference Fung2003), and has been used to refer to a variety of forums gathering together groups of citizens to deliberate on a particular political issue. Sometimes the term is used to describe forums that are open to all citizens, such as participatory budgeting. However, the focus of this article is on formats where participants are recruited through specific methods that ensure the representation of different societal groups or viewpoints. In addition, all deliberative mini‐publics share certain procedural features – most importantly, participants receive information on the issue at hand and deliberate in facilitated small groups (Dryzek & Goodin Reference Dryzek and Goodin2006; Grönlund et al. Reference Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014).

Deliberative mini‐publics can be regarded as democratic innovations – that is, institutions and practices that are expected to deepen and improve public engagement in political decision making (Smith Reference Smith2009: 1). Although deliberative mini‐publics have been increasingly used at different levels of governance in various parts of world, their policy impacts have usually been quite weak. In other words, there seems to be a problem when it comes to the macro‐political ‘uptake’ of mini‐publics (Dryzek & Goodin Reference Dryzek and Goodin2006). Mini‐publics have been organised for a variety of purposes, including civic education, consulting policy makers and, in a few cases, actually making policy decisions (for a review, see Gastil Reference Gastil, Kies and Nanz2013). Consultative mini‐publics have come under particular criticism for allowing policy makers to ‘cherry‐pick’ ideas and suggestions best fitting to their own political agenda (Smith Reference Smith2009: 93). This leads to failure in realising the epistemic benefits of mini‐public deliberation as well as frustration and disappointment among those citizens involved in the process. Overall, questions have been raised as to whether the use of mini‐publics has actually improved the quality of policy making judged by the standards of deliberative democracy (e.g., Parkinson Reference Parkinson2004; Hendriks Reference Hendriks2006, Reference Hendriks2009). More recently, mini‐publics have become subject to stronger criticism due to claims that they lack legitimacy and that they actually undermine the role of a critical civil society (Lafont Reference Lafont2015).

Despite these misgivings, this article argues in support of the expansion of the role of mini‐publics in the context of representative democracies. There are already encouraging examples of the use of mini‐publics in conjunction with direct democratic institutions such as popular initiatives and referendums. The most notable example of such a practice is the Citizens’ Initiative Review (CIR) in Oregon, where mini‐publics are used as a trusted source of information for voters (Warren & Gastil Reference Warren and Gastil2015). However, it is harder to find similarly encouraging examples on the use of mini‐publics in conjunction with representative decision making. There are recent studies exploring the possible roles of mini‐publics in deliberative democratic systems (e.g., Niemeyer Reference Niemeyer, Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014; Böker & Elstub Reference Böker and Elstub2015; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2015; Curato & Böker Reference Curato and Böker2016). In addition to the studies on CIR, there are works exploring mini‐publics in other contexts, such as in various governmental agencies (Fuji‐Johnson Reference Fuji‐Johnson2015), network governance (e.g., Hendriks Reference Hendriks2006), sub‐national government (Roberts & Escobar Reference Roberts and Escobar2015) and parliamentary decision making (e.g., Hendriks Reference Hendriks2016).

The purpose of this article is to tackle the issue of institutional design more carefully and to make some concrete proposals for designs that help strengthen deliberative mini‐publics in the context of representative decision making. The aim is to find ways in which deliberative mini‐publics could facilitate processes of justification and deliberation in representative politics. The underlying design principle is in line with Goodin's (Reference Goodin1996: 41) view that institutions should be ‘sensitive to motivational complexity’ among political actors. The article begins with an introduction of the design features of mini‐publics and the key arguments for and against their use in democratic systems. The latter part of the article explores institutional designs by which mini‐publics could enhance deliberation among representatives and, potentially, among the public at large. Mini‐publics could be better connected to representative decision making through institutional arrangements, which institutionalise their use; involve representatives in deliberations; motivate public interactions between mini‐publics and representatives; and provide opportunities for ex post scrutiny or suspensive veto powers. The prospects and problems of these measures are analysed and their applicability is discussed.

The idea of mini‐publics

Design features of mini‐publics

This section introduces the specific design features of deliberative mini‐publics and discusses how these features facilitate high‐quality deliberation. The main motivation for developing forums for citizen deliberation has been to narrow the gap between public opinion and political decision making (Crosby Reference Crosby, Renn, Webles and Wiedemann1995). The most well‐known formats of deliberative mini‐publics include citizens’ juries and planning cells (both developed in the 1970s), consensus conferences modeled by the Danish Board of Technology in the 1980s and deliberative polls designed by James Fishkin in the 1990s (for a review, see Smith Reference Smith2009; Grönlund et al. Reference Grönlund, Bächtiger and Setälä2014). The idea of deliberative polls is to create a method of measuring considered public opinion instead of opinions given ‘from the top of the head’, which is typical of traditional opinion polls (Fishkin Reference Fishkin2003). Other formats include Citizens’ Assemblies that have been used, for example, in electoral reform processes in British Columbia and elsewhere (Warren & Pearse Reference Warren and Pearse2008).

Citizens’ juries and consensus conferences are relatively small deliberative bodies consisting of tens of participants, whereas deliberative polls and some other formats include hundreds of deliberators. Small‐scale mini‐publics usually come up with written policy recommendations, whereas deliberative polls provide data on individual opinions before and after deliberation. Statistical sampling methods are applied in the recruitment of participants in deliberative polls and in other large‐scale mini‐publics, as well as in citizens’ juries. Deliberative mini‐publics have thus been regarded as a revival of the ancient democratic idea of selection by lot (sortition) (e.g., Gastil & Richards Reference Gastil and Richards2013: 263–264). The use of population samples in the recruitment of participants alleviates self‐selection biases, which are likely to occur when other recruitment methods such as open invitations are used.Footnote 1 Regardless of the use of sampling methods, the number of participants in mini‐publics is usually too small to claim that they would be a statistically representative sample of the whole population. Representativeness can, however, be improved by stratification according to certain sociodemographic variables (e.g., gender, age, education). Moreover, it has been argued that instead of providing descriptive representation of different sociodemographic groups, mini‐publics should aim for the representation of different viewpoints or discourses on the issue at hand (Brown Reference Brown2006).

The weighing of arguments by their merits is the key aspect of deliberation that distinguishes it from other forms of political action (Habermas Reference Habermas2005). Processes of group deliberation are sometimes criticised for giving rise to certain undesirable group dynamics, such as conformism and group‐think, rather than the weighing of arguments (Sunstein Reference Sunstein2002). Based on studies in cognitive science and social epistemology, it may be argued that a diversity of opinions and the encouragement of dissent are keys to the epistemic benefits of deliberation (Solomon Reference Solomon2006: 31–32). The use of random sampling in the selection of deliberators enhances a diversity of viewpoints in mini‐publics. Furthermore, the fact that deliberators are strangers to each other is likely to help avoid group‐think, which is more likely to occur when deliberators are connected through social bonds (Sunstein Reference Sunstein2003: 27–28; Solomon Reference Solomon2006: 35).

Studies on mini‐publics do not indicate group‐think, which suggests that their institutional design features help facilitate deliberative interactions. Deliberative polls, especially, provide a quasi‐experimental set‐up that allows researchers to study the dynamics of deliberation and its effects on participants’ political opinions, knowledge and attitudes (see, e.g., Luskin et al. Reference Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell2002, Reference Luskin2014; Andersen & Hansen Reference Andersen and Hansen2007). In general, the results of deliberative experiments show that participants learn about the issue, become more understanding with respect to alternative viewpoints, and that there are no clear signs of group pressures. These results lend support to the theoretical ideas presented in theories of deliberative democracy. Moreover, there is also evidence that the requirement of a written policy recommendation does not necessarily create non‐deliberative group dynamics as long as minority views are also allowed in the final statement (Setälä et al. Reference Setälä, Grönlund and Herne2010).

Possible roles of mini‐publics in democratic systems

Although many aspects of the internal functioning of mini‐publics call for further studies, there are even more critical questions when it comes to their possible roles in democratic systems. Deliberative democrats maintain that inclusive deliberation is needed to improve the epistemic and moral qualities of public decisions as well as enhance their legitimacy (Cohen Reference Cohen and Elster1998). Some deliberative democrats (e.g., Lafont Reference Lafont2015) have argued that, instead of deliberative mini‐publics, the normative idea of deliberative democratic legitimacy requires ongoing processes of public scrutiny of political arguments among the wider public. Based on an analysis of mini‐publics in various contexts, Curato and Böker (Reference Curato and Böker2016) conclude that their quality remains ‘ambivalent’ from the perspective of deliberative democracy. However, there are influential arguments as well as some evidence supporting the view that deliberative mini‐publics could help remedy insufficiencies and failures of democratic deliberation among elected representatives and the public at large.

Dahl (Reference Dahl1989) argues that current representative institutions do not provide sufficient measures in terms of information processing and communication, considering the technical and moral complexity of political problems. Decisions on issues such as nuclear energy, biotechnology and healthcare prioritisation require extensive scientific and technical expertise. As a consequence, there seem to be risks of cognitive over‐burdening among representatives and the withdrawal of citizens from collective reasoning processes. Dahl (Reference Dahl1970, Reference Dahl1989: 337–338) expresses concerns that decision‐making powers on complex issues in contemporary democracies are increasingly in the hands of technocrats rather than elected representatives. As a remedy, he suggests the use of a deliberative citizen forum (so‐called ‘mini‐populus’) in order to engage citizens in policy making on complex issues and, consequently, to counteract tendencies towards ‘quasi‐guardianship’ (Dahl Reference Dahl1989: 340–341).

Inclusive and high‐quality citizen deliberation has also been called for on the most important political decisions, such as constitutional issues, basic human rights and issues with long‐term effects (e.g., MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie, Gosseries and González‐Ricoy2016). Furthermore, Thompson (Reference Thompson, Warren and Pearse2008a) has called for deliberative citizen engagement on issues where representative actors have vested interests. This is likely to be the case in issues pertaining to the design of democratic institutions, such as electoral and parliamentary institutions, and in issues such as party and campaign financing that directly affect the interests of the key political actors. Deliberative mini‐publics could be used on such issues in order to minimise the influence of self‐interested and short‐sighted calculations by parties and individual representatives.Footnote 2 Mini‐publics could also have a role in situations where there is little scope for deliberation because voters are polarised and unwilling to understand ‘the other side’ (Luskin et al. Reference Luskin2014). In such situations, representatives may find it impossible to engage in constructive deliberations in the representative arena because they are too constrained by their constituents (Elster Reference Elster1998). Mini‐publics could be used to overcome deadlocks in polarised situations because they provide a forum for inclusive deliberation without constituency constraints.

Finally, as already indicated, mini‐publics could be used as trusted sources of information for voters. The use of mini‐publics seems especially useful for situations where citizens have particular incentives to reflect on issues – for example, because of an upcoming popular vote. Warren and Gastil (Reference Warren and Gastil2015: 568) point out that since most bodies in the political realm are promoting partial perspectives, they therefore do not facilitate good judgments among the public at large. Mini‐publics could have a role as a source of a specific type of political trust, named by Warren and Gastil (Reference Warren and Gastil2015) as ‘facilitative trust’. When accessible to the general public, reasoning processes in mini‐publics could help citizens understand arguments for and against different policy alternatives and critically reflect on them.

This is the rationale behind the CIR in Oregon, which is a citizens’ jury reviewing policy proposals submitted to popular votes. The CIR is also a good example of the institutionalisation of deliberative mini‐publics because it is regulated by the state law of Oregon as a part of the direct democratic process (Gastil & Richards Reference Gastil and Richards2013: 264). The voting recommendations and arguments formulated in the CIR process are distributed to voters, together with other voting material (Gastil & Knobloch Reference Gastil and Knobloch2011).Footnote 3 There is some evidence that a large proportion of voters in Oregon actually trust the CIR as an institution – in fact, it is more trusted than the state legislature – and take advantage of its arguments when making up their minds on ballot initiatives (Warren & Gastil Reference Warren and Gastil2015: 571). The example of the CIR already shows that the opposition between mass deliberation and mini‐publics (e.g., Lafont Reference Lafont2015) may be misplaced because mini‐publics can be used in ways that facilitate deliberation and critical evaluation among the general public.

The problems of connecting mini‐publics to representative decision making

Compared to the CIR, there do not seem to be such promising experiences on the use of mini‐publics in the context of representative decision making. This issue is analysed more in detail in this section. Certain features of representative systems, such as electoral accountability, government‐opposition divide and party discipline, seem to undermine the prospects of deliberation in representative arenas (e.g., Chambers Reference Chambers2004; Stasavage Reference Stasavage2007). Despite the fact that electoral accountability is a cornerstone of contemporary representative democracies, it may generate what Chambers (Reference Chambers2004) calls ‘plebiscitary rhetoric’, which hinders deliberation among elected representatives. Obviously, there are differences between the quality of deliberation in representative systems depending on, for example, the electoral system (majoritarian/proportional) and parliamentary rules and procedures (Steiner et al. Reference Steiner2004).

Rather than setting up new institutions like deliberative mini‐publics, a more obvious way of improving the quality of representative deliberation would be to redesign representative institutions. For example, the lack of publicity of committee work is often expected to foster deliberation among representatives, but it comes at a price because it potentially motivates bargaining instead of deliberation (cf. Vermeule Reference Vermeule2007: 205). Organising deliberative mini‐publics adds another dimension to decision making: the involvement of non‐elected ‘citizen representatives’ (Warren Reference Warren, Warren and Pearse2008). The members of mini‐publics represent different viewpoints on the issue but, unlike elected representatives, they are not accountable to particular groups of voters (Warren Reference Warren, Warren and Pearse2008: 62). For this reason, ‘citizen representatives’ could be expected to be more open to argument and more capable of finding constructive agreement than their elected counterparts.

Yet while the absence of electoral accountability makes ‘citizen representatives’ less constrained and therefore in a better position to engage in deliberative interactions, it also seems to leave them without authorisation and legitimation. This feature of mini‐publics has also been regarded as a problem by some deliberative democrats. For example, Parkinson (Reference Parkinson2006: 33) argues: ‘What is missing from such selection processes is the legitimating bonds of authorization and accountability between participants and non‐participants.’ However, it is not clear whether the problem pertains to empirical or perceived legitimacy, or to a more normative notion of legitimacy characterised in the theory of deliberative democracy. This issue will be discussed later in this article.

Deliberative democrats have also criticised practices of mini‐publics because of the possibility of their strategic use. Policy makers may organise mini‐publics in order to strengthen their own position in the eyes of the public, or to advance and legitimise policies they pursue. Deliberative mini‐publics may also undermine the role of representative institutions. Through organising mini‐publics, non‐elected officials can claim that public opinion has been taken into account in decision making and, on this basis, it becomes possible to bypass elected representatives (Hendriks Reference Hendriks2009). Other critics have argued that policy makers may use deliberative mini‐publics as ‘token’ consultations in order to silence critical voices from the civil society. In fact, deliberative democrats’ concerns that mini‐publics undermine deliberative civil society seem to materialise in such situations (e.g., Lafont Reference Lafont2015).

Apart from the CIR mentioned above, there are very few examples of the institutionalisation of mini‐publics. Typically, they have been used on an ad hoc basis whenever policy makers – either elected representatives or non‐elected officials – have experienced a need for this type of consultative citizen engagement. The use of consensus conferences was (weakly) institutionalised in Denmark during the 1980s. Subsequently, the Danish Board of Technology, at the time a parliamentary institution for technology assessment, organised several consensus conferences on complex technical and environmental issues. The statements given by consensus conferences were distributed among parliamentarians, and there is some evidence that parliamentarians found these statements useful and that they had an impact on the legislative process (Joss Reference Joss1998). However, the practice of consensus conferences came to an end in Denmark in the early 2000s.

In many ways, deliberative mini‐publics are currently perceived as types of ‘focus groups’ rather than legitimate forums of collective will‐formation (Goodin Reference Goodin2008: 25–28). Although mini‐publics are used as ‘consultative’ bodies, it often remains obscure as to how, exactly, their advice is taken into account. This allows decision makers to be selective with respect to which pieces of advice they follow and which they do not. Although mini‐publics have sometimes been used in outright manipulative ways to promote specific policy goals (see, e.g., Dryzek Reference Dryzek2015), the selective use of mini‐publics’ recommendations may also be an outcome of less conscious processes. Cognitive scientists have shown a variety of biases in people's reasoning and information processing, including the tendency to interpret evidence according to pre‐existing views (Kunda Reference Kunda1990; Mercier & Landemore Reference Mercier and Landemore2012). Such biases are likely to be at play also in the situation where policy makers familiarise themselves with the arguments made in mini‐publics.

The problem of ‘cherry‐picking’ can be identified in all contexts, as well as when other citizens or non‐elected officials deal with recommendations given by citizen forums. Yet, there are reasons to believe that these problems are more aggravated in the context of representative decision making. Partisan political competition, especially, is likely to amplify the tendency towards biased interpretations of recommendations by mini‐publics. Moreover, dissatisfaction with recommendations may lead to accusations of the manipulation of the process. In politicised contexts of representative decision making, mini‐publics are thus likely to be associated with the goals of those who initiate them and, as a consequence, the outcomes of deliberations remain contested. In this respect, various areas of public administration, where officials can define problems in more pragmatic terms, may appear to be more successful environments for the use of mini‐publics (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). In these contexts, recommendations by mini‐publics are less likely to be associated with specific partisan goals (e.g., Carson & Hart Reference Carson and Hart2005).

In sum, recommendations by mini‐publics, however well justified, are unlikely to be carefully considered by elected representatives. This is related to another problem in the interaction between mini‐publics and elected representatives – that is, the lack of incentives to consider the recommendations by mini‐publics. Compared to aggregative forms of democratic participation such as advisory referendums, deliberative mini‐publics are much weaker instruments. Representatives are usually strongly motivated to consider the opinions of the majority of voters, not least because of their own and their party's success depends on the number of votes gained in elections (Setälä Reference Setälä2011). This is obviously not the case with mini‐publics.

Connecting mini‐publics to representative decision making

This section outlines better ways of connecting deliberative mini‐publics to representative decision making, which thereby addresses at least some of the problems of mini‐publics. Using the terminology of Mansbridge et al. (Reference Mansbridge, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 22–24), the problem with current usages of mini‐publics seems to be that from the systemic perspective they are either too ‘tightly coupled’ with authorities, which leads to problems of co‐optation, or that they are ‘decoupled’, which leaves them without impact in decision making. Although the measures suggested below would strengthen the role of mini‐publics, they are based on the view that elected legislatures have a key role in representative democracies. These measures represent what Hendriks (Reference Hendriks2016) calls ‘designed coupling’, which means that there are specific institutional arrangements regulating interactions between mini‐publics and elected representatives.

The first aim is to address the problem that deliberative mini‐publics are typically used by governments on an ad hoc basis. For this purpose, alternative procedures of initiating and setting the agenda for mini‐publics are considered. The second aim is to address the problem of limited political impact, or the ‘uptake’ of mini‐public deliberations. The purpose of the suggested measures is not that policy proposals and arguments developed in mini‐publics would be adopted as such; rather, the aim is to look for measures that motivate elected representatives to reflect upon and respond to recommendations made by mini‐publics.

Procedures of initiating and agenda‐setting

Deliberative mini‐publics could be established as more or less permanent institutions with similar tasks to those of parliamentary select committees. The permanence of deliberative mini‐publics would help the public to recognise them as an institution playing a particular role in public decision‐making processes. The institutionalisation of mini‐publics would not, however, mean that they would have longstanding members. As pointed out above, from the perspective of social epistemology it may be recommendable that mini‐publics involve a group of citizens who are not bound by social bonds at the outset. In order to maintain this specific characteristic of mini‐publics, participants should be chosen through random mechanisms, and membership in mini‐publics should rotate on an issue‐by‐issue basis.Footnote 4

The big question remaining is how to decide on the use of mini‐publics and to define the issues to be dealt with – that is, the agenda for mini‐public deliberations. It may also be asked whether mini‐publics should have a role in agenda‐setting, or whether they should be instruments to weigh arguments related to pre‐defined issues. Dahl (Reference Dahl1989) suggested that there would be a specific mini‐populus defining the agenda for other mini‐populi. In Dahl's scenario, mini‐publics would be used to prioritise policy issues and influence the political agenda more generally. However, Dahl said very little about the modes of interaction between mini‐populi and elected representatives.

Because of the problems of ‘tight‐coupling’, it might not be recommendable to allow governments to decide on the use of mini‐publics. When governments decide on the use of mini‐publics on a particular issue, there is an apparent risk that they use them to achieve their own policy goals or to legitimise their own position. For this reason, it seems important to specify the situations where mini‐publics are used. In terms of the initiation and the agenda‐setting of mini‐publics, one can learn from the experience of referendums. Following the example of so‐called ‘mandatory referendums’, the use of mini‐publics could be required when parliaments are legislating on certain types of issues. These could include, for example, constitutional issues, electoral reform and party financing, and perhaps certain types of technically complex matters, which was the case in the Danish practice of consensus conferences.

The decision to organise deliberative mini‐publics could be made by political actors other than governments. Deliberative mini‐publics could be triggered, for example, by a request from a parliamentary committee. This was the case in energy‐related deliberations organised in the New South Wales parliament, where the citizen‐group discussions were part of the energy inquiry conducted by the Public Accounts Committee and were expected to complement the standard inquiry procedure (Hendriks Reference Hendriks2016: 49–50). In addition to committee‐initiated mini‐publics, there could be procedures allowing a certain number of members of parliament to initiate a mini‐public on a particular issue. These kinds of measures would strengthen the position of opposition groups. Moreover, they would enhance the inclusiveness of public deliberation on specific policy issues.

Deliberative mini‐publics could also be initiated by a certain number of citizens. In this case, mini‐publics would be a part of a procedure where new issues are placed onto the political agenda. In more concrete terms, mini‐publics could be introduced as a part of the procedure of dealing with so‐called ‘agenda’ (or ‘indirect’) initiatives. Unlike ‘full‐scale’ initiatives which lead to a popular vote, these are citizens’ initiatives dealt with by elected representatives (e.g., Setälä & Schiller Reference Setälä and Schiller2012).Footnote 5 Following the example of the CIR in Oregon, agenda initiatives could be reviewed by a deliberative mini‐public before they are discussed and voted upon by elected representatives. Alternatively, following the example of the NSW energy inquiry, mini‐publics could be used to complement committee deliberations on a particular agenda initiative. The institution of agenda initiative would be strengthened through these kinds of procedures that allow non‐elected ‘citizen representatives’, who are not constrained by party discipline or specific groups of constituents, to take a standpoint on citizens’ initiatives.

Strengthening the impact of mini‐publics

Deliberation with representatives.

In general, the political impact of mini‐publics has been highly contingent on the willingness of decision makers to take their recommendations into account. One obstacle to the influence of mini‐publics is the vagueness of their policy recommendations compared, for example, to those provided in advisory referendums. Deliberative polls, especially, do not provide any policy recommendations at all – only data on individual opinions. In order to enhance the influence of mini‐publics, the task of a mini‐public should be clearly defined at the outset; in other words, it should be expected to take a position on a particular issue. The statement given by a mini‐public could follow the example of the CIR and include a (super‐)majority position on an issue and reflections on the main arguments for and against policy alternatives.

According to Parkinson (Reference Parkinson2004), one of the problems of mini‐publics is that they do not encourage deliberation among those who actually make decisions. Involving elected representatives directly in mini‐public deliberations could be one way of remedying this problem. The main benefit of including representatives in deliberations is that it would develop their sense of ‘ownership’ of the process, which is likely to boost the impact of mini‐publics. Involving elected representatives could occur through integrating deliberative mini‐publics with committee work when the role of a mini‐public would be to consult policy making on an issue on the committee's agenda.

Another option would be to organise specific committees or assemblies that include both elected representatives and citizen representatives. This would help involve some of the representatives directly in the deliberative processes of mini‐publics. The Irish Constitutional Convention in 2013 consisted of 66 randomly selected citizens and 33 elected representatives from the Oireachtas and Northern Ireland Assembly (Farrell Reference Farrell, Ferrari and O'Dowd2014). Apart from its composition, the Convention was organised following the procedures used in deliberative mini‐publics. The task of the Convention was to give its recommendations on a list of proposals for constitutional reforms; in addition, it could propose any constitutional amendment it wished to be considered. Like many other mini‐publics, the Irish Convention was an advisory body, which means that it was up to the government to decide which of its recommendations would be submitted to constitutional referendums. The government did, however, commit itself to responding to the recommendations of the Constitutional Convention in a timely fashion, which is in line with the idea of ‘designed coupling’. Moreover, the fact that the Convention was expected to take a stand on a list of specific amendments helped it to come up with clear recommendations.

The main motivation for including both citizens and elected representatives was to minimise the risks of ‘disconnect’ between deliberating citizens and elected representatives (Farrell Reference Farrell, Ferrari and O'Dowd2014). The strategy was chosen given the evidence from processes of citizen deliberation that have failed due to a lack of commitment by those in power. Involving members of parliament in the deliberation was expected to resolve this problem. Of course, the inclusion of professional politicians alongside lay citizens entails certain risks as well. Using the terminology of Mansbridge et al. (Reference Mansbridge, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012), the biggest risk seems to be that citizen deliberation becomes too tightly ‘coupled’ with representative deliberation. Before the Irish Convention, there were concerns that politicians would dominate discussions and intimidate the deliberating citizens. According to some observations, it appears that these concerns did not materialise and the procedures used in mini‐publics helped balance discussions (Suiter et al. Reference Suiter, Farrell, Harris, Reuchamps and Suiter2016; for a somewhat different experience from a similar design, see Flinders et al. Reference Flinders2016).

In the Irish case, the proposals for constitutional amendments have to be submitted to constitutional referendums after they have received support from the government. In this respect, the government can still, to some extent, ‘cherry‐pick’ those proposals that fit its own agenda.Footnote 6 It is also notable that the Irish Convention did not exemplify a situation where deliberative mini‐publics are connected to representative decision making only. The fact that proposals are expected to be submitted to popular votes is also likely to incentivise representatives to consider the proposals by the Convention carefully and even‐handedly. If the final decisions were to be made by the majority of representatives, factors such as a government‐opposition divide and party discipline could play a bigger role.

Public interaction between mini‐publics and elected representatives.

Based on her analysis of a case of citizens’ juries organised in conjunction with a parliamentary committee in New South Wales, Hendriks (Reference Hendriks2016) discusses the ways in which deliberative mini‐publics can be coupled with representative decision making. She points out that ‘coupling’ does not need to be unidirectional, meaning that mini‐publics’ recommendations are considered by policy makers, but it could be bidirectional, meaning that policy makers also provide a justification to a mini‐public. For example, policy makers could be required to give an account of how they have responded to the mini‐public's recommendations within an agreed time‐frame. As pointed out above, this has been the practice in planning cells.

In the parliamentary context, the response could be given, for example, by a relevant committee and could entail justifications for which of the recommendations by a mini‐public will be followed and which will not. In this way, mini‐publics could be perceived as a method of enhancing deliberation among elected representatives as well as exhibiting so‐called ‘deliberative accountability’, understood as a process where representatives publicly give reasons for their policy choices (Gutmann & Thompson Reference Gutmann and Thompson1996: 128). As pointed out by cognitive scientists, the requirement of a justification helps to neutralise biases in reasoning and establish accuracy goals (Kunda Reference Kunda1990). A response by representatives should, therefore, alleviate the problem of ‘cherry‐picking’ by making representatives explain the reasons for the adoption or the rejection of specific policy recommendations by a mini‐public. Moreover, a response to a mini‐public could also lessen constituency constraints as well as those created by party discipline. It could motivate representatives to formulate and endorse such positions that can be justified to the ‘universal’ audience embodied in a mini‐public – that is, to reasonable people representing different interests and values (cf. Perelman & Olbrechts‐Tyteca Reference Perelman and Olbrechts‐Tyteca1969). However, the requirement of a justification is still a weak measure, and it seems necessary to look for further measures through which representatives could be incentivised to engage in a dialogue with mini‐publics.

The publicity of representatives’ responses could be one way of enhancing the political resonance of mini‐publics. Representatives’ responses could be put forward in a specific committee or in plenary sessions where the recommendations are publicly discussed. Ideally, representatives of mini‐publics should also have a say in these sessions. In addition to motivating representatives to react to the recommendations of a mini‐public, publicity also generates, in Elster's (Reference Elster1998) terms, consistency constraints that motivate representatives to follow their own public statements in actual decision making. Moreover, the opportunity to follow public communications between decision makers and mini‐publics could help those ‘ordinary’ citizens following the process to understand and reflect on arguments presented for and against different policy alternatives. In this respect, mini‐publics could facilitate more informed judgments among the public at large.

For example, Rehfeld (Reference Rehfeld2005) distinguishes between the sanctioning and justification dimensions of electoral accountability. Electoral mechanisms may be relatively efficient when it comes to opportunities to sanction representatives. However, the capacity of an electoral mechanism to enhance public justifications for policies may be limited and sometimes actually distorts deliberative accountability by giving rise to plebiscitary rhetoric (Chambers Reference Chambers2004). Public interactions between elected representatives and mini‐publics could potentially remedy ‘deliberative deficits’ in representative systems without undermining the sanctioning mechanisms involved in electoral accountability.

The downside of such interactions is that publicity is likely to vary across issues and, as such, it would not entirely eliminate the problem of ‘cherry‐picking’. Publicity constraints will remain contingent on a variety of factors such as the saliency of the issue, media attention and the proximity of elections. If elected representatives feel especially constrained by their own constituents, they might even use these new forms of publicity to appeal exclusively to them. Therefore, publicity may also open room for self‐serving uses of mini‐publics for politicians’ own reputation‐building. These possibilities illustrate the difficulties of reconciling the logic of democratic deliberation with the logic of contestatory politics at representative forums.

Opportunities for ex post scrutiny or suspensive veto powers.

One of the main weaknesses of deliberative mini‐publics is that they have very little influence or control over how their recommendations are interpreted in actual decision making. Therefore, it is necessary to consider ways in which mini‐publics could have formal opportunities to scrutinise those policy proposals or actual decisions to which they have contributed. Above, the opportunity of public dialogues between mini‐publics and elected representatives was discussed as a measure to enhance the role of mini‐publics. These kinds of interventions by mini‐publics could also be organised at later stages of the legislative process – for example, in conjunction with the parliamentary plenary sessions dealing with the relevant policy proposal. This procedure would allow members of a mini‐public to engage directly in the parliamentary discussions leading to a decision and provide a mini‐public with at least a say, if not actual control, on the ‘uptake’ of its recommendations. Furthermore, it would enhance the deliberative accountability of elected representatives because they would need to justify their views in the presence of a mini‐public.

The role of mini‐publics could be enhanced by providing them with suspensive veto powers – that is, powers to delay decisions made by representatives. These veto powers, like those of the House of Lords in the British parliamentary system (Parkinson Reference Parkinson2007: 380), would strongly incentivise legislators to take the deliberations of mini‐publics into account and to engage in serious dialogues with them. MacKenzie (Reference MacKenzie, Gosseries and González‐Ricoy2016) suggests the establishment of a separate, randomly selected chamber with powers to delay legislation. The chamber would be allowed to review all legislation from the perspective of whether it is in accordance with the public interest. MacKenzie argues further that design features of the randomly elected chamber are likely to enhance sensitiveness to future interests, even if it is not mandatory to consider them.

Mini‐publics with suspensive veto powers could also be required on certain types of issues, such as constitutional issues or other issues of institutional design, or they could be based on a citizens’ initiative, for example. In practice, the procedure could be the following: A deliberative mini‐public would be organised at the early stage of the legislative process when a policy proposal is drafted. After a law has been passed by a majority of elected representatives, the same mini‐public could delay the legislative process where it finds that the decision accepted by the parliamentary majority does not sufficiently reflect its deliberations or that the majority position is poorly justified.

This kind of mechanism would establish a mini‐public as an institution with rights to review legislation. It would efficiently limit ‘cherry‐picking’ because participants of would have some control in the process where its recommendations are translated into actual decisions. Allowing deliberative mini‐publics to scrutinise and suspend legislation would generate ‘iterated deliberation’, which entails rounds of revisions of policy proposals based on deliberative exchanges. Thompson (Reference Thompson2008b: 515) argues that iterated deliberation between two or more political bodies is recommended because of its corrective capacity. Moreover, when these public reasoning processes are public and there are stakes involved, they potentially foster critical judgment among the public at large. Obviously, iterative processes tend to delay decision making, which may be regarded as a problem when urgent decisions are needed.

Summary and discussion

The purpose of the discussion above has been to show some concrete ways in which mini‐publics could be better integrated into representative decision making. Deliberative mini‐publics should be regarded as one of many alternatives for institutional reform that improves the quality of public deliberation in representative systems. Moreover, the expansion of the role of mini‐publics should not rule out other institutional reforms, or the development of societal conditions facilitating critical deliberation among the general public. In this way, micro and macro political approaches of improving the quality of democratic systems should not be regarded as mutually exclusive – indeed, there may be a need for both (cf. Curato & Böker Reference Curato and Böker2016: 176, 187).

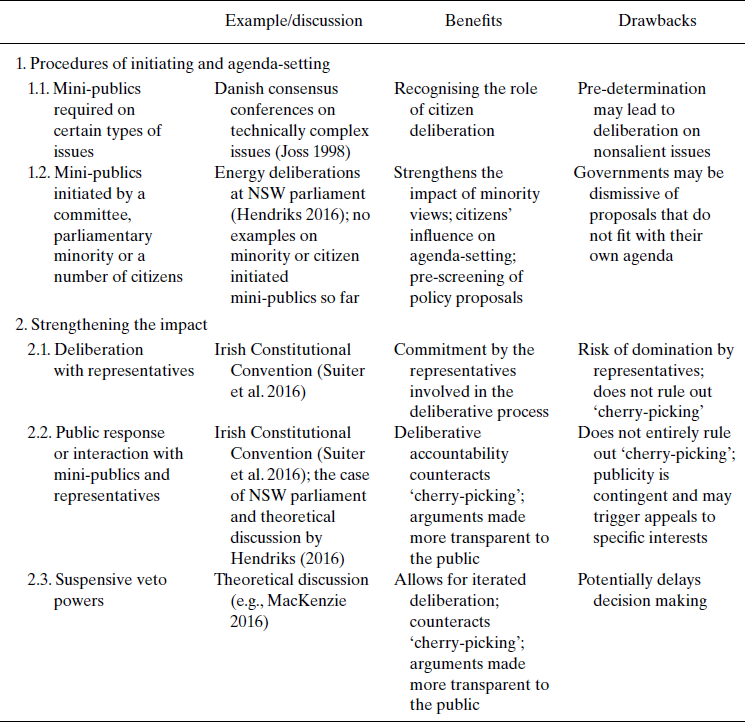

Obviously, institutional arrangements enhancing the role of mini‐publics should be combined with guarantees of the integrity of their internal proceedings – most notably, the fairness and transparency of recruitment processes, the representativeness of a citizen panel, balance in expert hearings and the impartiality of facilitation. Moreover, there may be a need to further develop some aspects of group discussion and decision procedures (for some suggestions, see Karpowitz & Raphael Reference Karpowitz and Raphael2014: 346–360). In order to maintain public trust in mini‐publics, they should be run by an independent agency or a specific body overseen by all parliamentary parties (see Roberts & Escobar Reference Roberts and Escobar2015: 242). Table 1 summarises the pros and cons of the measures suggested in the discussion.

Table 1. Measures enhancing the role of deliberative mini‐publics in representative decision making

Obviously, the suggested measures are not mutually exclusive. In particular, procedures of agenda‐setting and forms of interaction with representative actors concern different stages of the decision‐making process. Therefore, it is actually recommended that measures of both Types 1 and 2 are combined. When it comes to the prioritisation of different measures of Type 2, the measures enhancing public interaction and deliberative accountability (2.2.–2.3.) among elected representatives seem to be more recommendable because they give rise to iterative processes of public justification. Therefore, they have a potential to facilitate deliberation and critical assessment within civil society, although the effects of publicity remain contingent on the political stakes involved. Not all of the suggested measures have been tried out, and further empirical studies may be necessary in order to judge the appropriateness of different measures in the context of different representative systems.

The suggested measures are relatively cautious steps because they would not decrease the formal decision‐making powers of elected representatives. However, there are some proposals which go further. For example, Leib (Reference Leib2004) proposes the establishment of a fourth, popular branch of government based on deliberative citizen forums in the context of the American system of division of powers. In the context of parliamentary democracies, elected representatives could delegate their powers to mini‐publics for particular kinds of decisions, or mini‐publics could be established as a separate chamber with actual, not just suspensive, veto powers. However, even these suggestions do not entail that elected representative bodies would be replaced by randomly selected mini‐publics.Footnote 7

Nevertheless, further empowerment of mini‐publics would raise questions about the legitimacy of power exercised by non‐elected and non‐accountable ‘citizen representatives’. The fact that electoral authorisation is the basis of the perceived legitimacy of a representative relationship in contemporary democracies may set limits to the authorisation of mini‐publics. At the same time, it should be pointed out that randomly selected bodies, such as court juries, are already regarded as legitimate institutions in some democratic systems. Moreover, the CIR is already perceived as a trusted element of the system of direct democracy in Oregon (Warren & Gastil Reference Warren and Gastil2015). As Bohman (Reference Bohman2007, 143) argues in his book on transnational democracy: ‘In the end, formal, popular, and deliberative legitimacy should be manifested at various locations and stages of the process.’

From the normative perspective, one should remain open to the possibility that representative, randomly selected deliberative forums could be one element of a democratic system. In recent years, democratic theorists have put forward various reinterpretations of the concept of ‘democratic representation’ (e.g., Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2003; Rehfeld Reference Rehfeld2005; Bohman Reference Bohman2007; Dryzek & Niemeyer Reference Dryzek and Niemeyer2008; Urbinati & Warren Reference Urbinati and Warren2008), and many of these challenge the view that electoral representation is the only normatively defensible alternative. The predominant notion of electoral representation has also been challenged by such developments as increasing the need for transnational decision making. One might actually ask whether the types of reforms outlined in this article would be more urgent in other domains such as transnational governance than in the context of representative decision making. However, understanding motivational issues arising in representative politics helps pave the way to democratic reform also in other realms of public decision making.

Concluding remarks

In representative democracies, elected legislatures are the central arena of political contestation and deliberation, where conflicts related to political decision making are publicly articulated, but current systems of representative democracy appear to be deficient from the perspective of deliberative democracy. The use of deliberative mini‐publics could be one possible remedy to the problems of representative democracy, but the record of combining deliberative mini‐publics with representative decision making has not been particularly promising so far. It is not obvious how the epistemic benefits of mini‐publics could be reaped in the context of representative decision making. The risks of strategic uses of mini‐publics and ‘cherry‐picking’ seem especially acute in the politicised context of representative politics.

This article has outlined measures through which mini‐publics could be strengthened so that they would enhance the quality of deliberation among elected representatives. In addition, it calls for institutional designs which would, first, specify the conditions of the use of mini‐publics, and second, incentivise elected representatives to communicate with mini‐publics. Specifying the conditions of the mini‐publics would help defuse concerns of underlying strategic motivations. The rest of the suggested measures enhance the impact of mini‐public deliberation on representative decision making. These measures motivate representatives to carefully consider the recommendations of mini‐publics and enhance justification and deliberative accountability among representatives. The most obvious step in this direction would be to give a mini‐public a say, not just when policy proposals are drafted, but also at later stages when these policy proposals are discussed and voted on in parliamentary committees and at the plenary.

Acknowledgements

This research has been financially supported by the Academy of Finland (project: ‘Democratic Reasoning’, number 274305). The author wishes to acknowledge Michael MacKenzie, Hélène Landemore and other participants of the CIR Workshop at Ash Center in April 2015, as well as the anonymous reviewers of the EJPR, for their helpful comments on the earlier drafts of this article. Special thanks go to Graham Smith for great discussions on this topic.