The crisis of democracy and its continued resilience in the face of unprecedented challenges has been the object of much political scholarship (Reference McCaffrie and SadiyaMcCaffrie and Akram 2014; Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2013; Reference RosanvallonRosanvallon 2008; Reference TormeyTormey 2014). While the support for democratic values remains strong, trust in and satisfaction with its institutions and representatives has led to a growing distance between state and citizens (Norris 2012). Increasing autocratization in democracies is another key concern (Reference Lührmann, Seraphine F., Sandra, Nazifa, Lisa, Sebastian, Garry and Staffan I.Lührmann et al. 2020). The contemporary democracy literature has widely echoed the critiques made by citizen mobilizations over the last decade, and can be grouped into four main areas: crisis of democracy (Reference Dardot and C.Dardot and Laval 2019; Reference CrouchCrouch 2004; Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2013; Reference MairMair 2013; Reference StreeckStreeck 2011); the post-representative possibilities for democracy (Reference Feenstra and J.Feenstra & Keane 2014; Reference KeaneKeane 2009; Reference RosanvallonRosanvallon 2008; Reference TormeyTormey 2015); normative proposals on models or repertoires (deliberation, sortition, referenda, citizen assemblies), and how practices and dynamics can be improved (Reference BarberBarber, 2013; Reference FishkinFishkin 2011; Reference Serdült and M.Serdült 2018; Reference SintomerSintomer 2017; Reference Van Reybrouckvan Reybrouck 2016).

The recent and ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has presented new and urgent challenges for democracy. It has highlighted the limitations of nationalism, the nation-state and contemporary democratic countries in addressing global challenges. It has highlighted and exacerbated existing inequalities and has thrown up both manifestations of transnational solidarity and increased boundaries between “us” and “them” in imagined communities under threat. It has curtailed democratic rights and freedoms to protest and assembly, but also stimulated democratic innovation, in many cases in the form of citizen-driven responses (Reference Afsahi, Emily, Rikki, Selen A. and Jean-PaulAfsahi et al. 2020; Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2022). As democracies face the second major global crisis in little over a decade, the need for innovation becomes all the more urgent.

In this article, I argue that the literature on democratic innovation has yet to adequately interrogate the role of social movements, and more specifically the role of democratic imaginaries, in innovation, nor has it considered the specific mechanisms through which movements translate democratic imaginaries and practices into innovation (section 1). I then point to some advances in social movement studies that highlight the contributions of social movements to democratic innovation, but suggest these need to be much more developed (section 2). To this end, I offer a preliminary roadmap for methodological and conceptual innovation in our understanding of the role of social movements in democratic innovation. I present the concept of democratic innovation repertoires and offer a framework for their analysis in social movements, using examples from pro-democracy movements (PDMs) to illustrate how this might be applied (section 3). I argue that not only do we need to broaden our conceptualization and analysis of democratic innovation to encompass the role of social movements, we also need to understand how the relationship between democratic movement imaginaries and the praxis that movements develop in their quest to “save” or strengthen democracy can shape democratic innovation beyond movement arenas, after mobilizing “events” have passed (section 4), and in the face of new challenges (section 5). I illustrate this point further drawing on the case studies of how Hong Kong and Taiwan's pro-democracy movements responded to COVID-19 (section 6). I conclude by highlighting the key arguments, pointing to some challenges and limitations of the approach, and calling for greater dialogue between democratic theory and social movement studies.

Democratic Innovation

In academic debates, discussions of widespread democratic malaise and its remedies revolve around the relative merits of formal models of democracy (e.g., participatory, deliberative, strong, discursive, welfare), with proponents arguing for more or less citizen participation, expertise, and knowledge (Reference BrennanBrennan 2017; Reference CrouchCrouch 2004; Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2020; Reference Earle, C. and Z.Earle et al. 2017; Reference SchumpeterSchumpeter 1943). Minimalist definitions of democracy that focus on procedural aspects (such as electoral accountability) are dominant, and because of their realist focus on the actual features and institutions of Western contemporary politics, empirical theories of democracy are ill-equipped to capture alternative visions of democracy (Reference HeldHeld 2006: 166), such as those developed in pro-democracy movements. I understand pro-democracy movements as those movements that take democracy as a central problematic and core ideational and practical organizing principle.

Democratic innovation studies develop from the analysis of a wide range of practical, political, and theoretical responses to the critiques of contemporary democracy, the decline in citizen trust in and satisfaction with it, and attempts to regenerate it. Democratic innovation is defined in the literature as some form of improvement or change that seeks to increase, diversify, or deepen opportunities for citizen participation in governance, policy, or public administration processes (Elstub and Escobar 2017; Giessel 2012; Reference SmithSmith 2009; Reference StewartStewart 1996).

John Stewart defines democratic innovations as processes “designed to bring the informed views of ordinary citizens into the processes of local government” (Reference StewartStewart 1996: 32). Reference SmithGraham Smith (2009: 5–6) also adopts an institution-focused approach by defining democratic innovations as institutions that have been specifically designed to increase and deepen citizen participation in the political decision-making process. Stephen Elstub and Oliver Escobar argue that “participatory and deliberative democracy can and do overlap in practice, despite theoretical differences and tensions between them” (Elstub and Escobar 2017: 10). Despite the recognition of the possibility for hybridity, with few exceptions (e.g., Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2013) these definitions focus exclusively on the relationship between citizens and governance institutions processes, and explore innovations emerging from governance institutions themselves. Reference Geissel, Brigitte and K.Brigitte Geissel (2012), for example, argues that the purpose of democratic innovations is to improve the quality of democratic governance.

Although Elstub and Escobar recognize that “democratic innovations are political sites for collective action” (Reference Elstub and Oliver2017: 4), their extensive scoping review reveals that existing literature almost exclusively focuses on procedural elements of democracy and innovation, sets aside treatments of the normative and substantive concerns that motivate innovation, and adopts a top-down policy-driven focus. While the starting assumption of the literature is that democratic innovations seek to reimagine the relationship between citizens and governance processes and institutions, attention to the alternative democratic imaginaries developed in social movements and the civil sphere is left out. Given the important role of social movements in democratic innovation (Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2020; Tilly and Wood 2012), it is striking that, as Reference WarrenWarren (2009) also notes, it has been policymaking rather than politics that has dominated the field.

Unlike most scholars of democracy, democratic innovators in social movements are operating with fuzzy models of democracy and focus on specific substantive issues central to their vision of democratic ideals. It is precisely this lack of being beholden to classical models and the focus on solving specific problems and democratic deficits that potentially enables the leap of imagination necessary to effectively innovate. Their imaginaries encompass substantive (why) not just procedural (how) components, and are oriented toward solving specific democratic deficits. Forcing these fuzzy movement models of democracy into classical models risks omitting precisely those elements that may be innovative, by failing to capture innovations that transcend pre-existing formal models, such as those based on technopolitical imaginaries, which have been central in several PDMs and post-mobilization innovations (Reference GerbaudoGerbaudo 2012; Reference PostillPostill 2018; Reference Romanos and IgorRomanos and Sádaba 2015).

Furthermore, formal procedural models are not designed to explore the role of national political cultures in shaping imaginaries and innovation repertoires. Yet work on movement transnational diffusion has shown the importance of national political cultures in facilitating or impeding the adoption of new ideas and practices (Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2016; Malets and Zajak 2014; Wood 2010).

In sum, the literature on democratic innovation is dominated by top-down approaches that focus on governance institutions, which has yielded a wealth of literature. However, it has largely ignored the role of conflict, contention, and social movements in producing democratic innovation, substituting a focus on policy for a focus on politics. Because it is based on formal procedural models that measure what is already in place, it cannot adequately capture the fuzzy democratic imaginaries of social movement actors who experiment with alternatives and can serve as sources and carriers of innovation.

Insights from Social Movements: An Emerging Focus on Movements as Carriers of Innovation

For its part, the scholarship on social movements and democracy has demonstrated the role of movements as producers and carriers of innovation, but still suffers from a focus on procedural models and forms of organization and a relative lack of attention to movement imaginaries. Despite these limitations, the important role of social movements in democracy and innovation has been well established in the literature. Movements are central actors in democracy, contributing to processes of democratization (Tilly and Wood 2012). They serve a watch-dog function (e.g., exposing and monitoring corruption), bear witness against social injustices, give voice to marginalized groups, and make claims on policy makers and representatives (Reference Feenstra, S., A. and J.Feenstra et al. 2017; Reference Keane, S., J. and W.Keane 2011; Reference MelucciMelucci 1989; Reference TouraineTouraine 1988). Social movements often express and offer alternatives to democratic malaise from both progressive and regressive positions (Reference Casas-Cortés, M. and D. E.Casas-Cortés et al. 2008; Reference Della Porta and M.Della Porta and Diani 2020: Reference Della Porta and A.Della Porta and Felicetti 2017; Reference HabermasHabermas 1985; Reference Kriesi and Takis S.Kriesi and Pappas 2015), with the global wave of pro-democracy movements following the global crash of 2008 and mobilizations in response to the coronavirus crisis offering recent emblematic cases.

Social movements and other civil society actors can also serve as important sources of democratic innovation (Reference CastellsCastells 1997; Reference MansbridgeMansbridge 1983; Reference PollettaPolletta 2012). They can “strengthen the normative foundation of democracy . . . by empowering citizens, channelling social demands and defusing violence” (Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2020: 145). They can enrich the public sphere, initiating and influencing political debate (Reference Kriesi, D., S. and H.Kriesi 2004), raising citizen awareness of key issues, increasing citizen ability to make considered judgements, and organizing mechanisms of direct democracy that increase citizen participation. Reference Della Porta and A.Della Porta and Felicetti (2017: 128) argue that movements enhance democracy by “promoting internal practices of democracy” and by “introducing democratic innovation into existing institutions.” Yet we should expand our understanding of movement innovation even further: Activists innovate beyond movements by also creating new organizations, such as movement-parties, socially transformative enterprises, or citizen projects that innovate in democratic participation, monitoring, or whistleblowing practices. We also still know very little about the precise relation between movement democratic innovation repertoires developed within movements during periods of mobilization and experimentation, and democratic innovation that stems from those processes in non-movement arenas (e.g., governance institutions) and after periods of mobilization or in new periods of mobilization. Activists are known to be “carriers” of movement innovations (new imaginaries, ideational frameworks, knowledge, tools, and practices) into different non-movement arenas—such as political parties, governance institutions, and social enterprise organizations—post-mobilization. Social movements are also known to have positive impacts on democracy (Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2020: Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2020; Reference Tilly and L. J.Tilly and Wood 2012), yet we still understand little about how, why, or what pro-democracy movements contribute to democratic innovation post-mobilization and with what challenges or effects. What is more, despite the explicit expression of democratic malaise across pro-democracy movements, and strong claims that this global wave has led to the emergence of a new global democratic imaginary (Reference TormeyTormey 2015), we are still lacking a systematic exploration of the understandings of democracy that participants mobilized in these movements and how these varied across sites. This knowledge is notably absent from existing comparative democracy indices, but is necessary for a robust understanding of how social movements impact democratic innovation. V-Dem (Reference Lührmann, Seraphine F., Sandra, Nazifa, Lisa, Sebastian, Garry and Staffan I.Lührmann et al. 2020), a major global democracy index, for example, distinguishes between two forms of pro-democracy activism: that which resists the dismantling of democracy (democratic countries), and that which seeks to establish democratic institutions (autocratic countries). This distinction fails to recognize and capture pro-democracy activism and innovation in democratic regimes that goes beyond the defense of a liberal democratic status quo and instead pushes for “real democracy” or a strengthening of existing democratic institutions.

Periods of crisis can create opportunities for democratic innovation by social movements because political institutions become destabilized and more permeable to critique, and because public demand for remedies for their grievances makes them receptive to alternative approaches to the status quo (Flesher Fominaya 2021; Reference GoldstoneGoldstone 1980; Reference Kriesi, D., M., D. and C.Kriesi and Wisler 1999; Reference LangmanLangman 2013). Mobilization during times of crisis can represent a “critical juncture” (Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2018) in which protests pass from routine to exceptional events that spur long term major changes in institutional politics, culture, and society (Reference TarrowTarrow 2017). Yet because social movement outcomes (i.e., consequences and impacts) are notoriously challenging to study (Reference GiugniGiugni 2008), the precise ways that social movements impact democratic innovation are difficult to capture. This is largely due to the internal complexity of social movements, their diffuse and ongoing effects, and the difficulty of analytically delimiting them in time and space. Yet capturing progressive movements’ democratic innovations is necessary in order to address pressing challenges facing contemporary democracy, and current predominant frameworks in the literature on democratic innovation theory and social movement scholarship do not provide adequate tools to do so.

Existing scholarship has yet to adequately interrogate the role of movement democratic imaginaries in innovation nor the specific mechanisms through which movements translate democratic imaginaries and practices into innovation. If indeed PDMs provide a possible source of regeneration for democracies in crisis, then we need to design research able to capture and interrogate the movement imaginaries of democracy and citizenship that inspire innovative practices, precisely the “imaginary” element of democratic innovation that is included in scholarly definitions but rarely interrogated. Failing to do so risks eliminating a priori precisely those aspects of innovation that can potentially serve to regenerate democracy.

What might such an approach look like? In what follows I will sketch out a framework for capturing democratic innovation repertoires within social movements, before suggesting avenues for research on movement democratic innovation beyond social movements, and in the face of new crises, using examples from three pro-democracy movements: in Spain, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

Capturing “Democratic Innovation Repertoires” within Social Movements: An Analytical Framework

Scholarship on progressive and “new social movements” has emphasized the central concern with democracy as internal practice and primary demand across a broad range of movements and geographies (Reference Braungart and M.Braungart and Braungart 1990; Reference CastellsCastells 1997; Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009; Reference MelucciMelucci 1989,). Deep treatments that also capture the democratic imaginaries and prefigurative practices of social movements have produced rich qualitative data but have tended to focus on single case studies (Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2020); analyses of the internal dynamics of social movements (Reference BreinesBreines 1989; Freeman [1970] Reference Freeman2013; Reference KatsiaficasKatsiaficas 2006; Reference MansbridgeMansbridge 1983; Reference PollettaPolletta 2012;); and periods of contentious mobilization (Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009; Reference McKayMcKay 1998).

Much literature on social movements understandably focuses on repertoires of contention, and on the conflictual aspects of mobilization (Reference CrossleyCrossley 2002; Reference McAdam, Sidney and CharlesMcAdam et al 2001). But movements do not just focus on contention and protest; a great amount of energy goes into prefigurative experimentation and producing new knowledge (Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009; Reference MelucciMelucci 1989,). Prefigurative experimentation was a core characteristic of the global wave of PDMs, facilitated by the organizational form of occupation camps that were fixed in space and persisted across time, enabling new social relations and synergies to develop (Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2020; Reference McCurdy, Anna and FabianMcCurdy et al 2016). Prefigurative politics in social movements refers to direct social action that develops and practices alternatives that embody the ends the movement is striving to realize in the wider society in the future (Reference GraeberGraeber 2002; Reference Leach, David A., Donatella, Bert and DougLeach 2013; Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009, Reference Maeckelbergh2011; Reference van de SandeVan de Sande 2013; Reference YatesYates 2015). As self-directed action rather than opponent-oriented conflict, prefiguration is left out of most contentious politics approaches in the field.

Prefiguration is crucial for pro-democracy movements that seek to align their internal practices with their political goals (Reference BleeBlee 2012; Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009; Reference PollettaPolletta 2012) such as those under discussion here. These movements are laboratories of democratic experimentation in which shared critical and alternative understandings of democracy develop, as activists explore what “good” or “real” democracy might look like, and what is required for it to work (Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2020; Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009).

Scholars also recognize that democracy in social movements has a constructed and contested meaning that poses a challenge to liberal representative democracy (Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2020; Maecklebergh 2009), yet the substance of those meanings is rarely explored systematically or in depth (but see Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009).

Many PDMs, for example, are motivated by democratic imaginaries stemming from movement traditions (e.g., technopolitical, feminist, autonomous) that existing formal models (i.e., participatory, deliberative) are poorly equipped to capture. Instead, I propose starting with an analysis of ideational frameworks. Movements engage in micro-political or cultural interventions that generate “know how” or the cognitive praxis that informs social activity (Reference Casas-Cortés, M. and D. E.Casas-Cortés et al. 2008). Activists’ ideational frameworks link democratic imaginaries to specific prefigurative movement practices (such as organizing nonhierarchically), and to specific demands and proposals outside movements (e.g., reforming or creating new institutions in wider society). They are also oriented toward addressing defined democratic deficits (e.g., corruption, insufficient citizen input, information disorders, gender inequality). This nexus comprises the ideational frameworks of PDMs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Ideational Frameworks

Democratic ideational frameworks in PDMs combine imaginaries with diagnostic frames that encompass problem definition, causal attributions, and attributions of responsibility/blame (adversarial framing), prognostic frames designed to solve defined problems, and collective action frames that legitimize and inspire social movement campaigns and motivate by-standers to act (Reference Benford and D. A.Benford and Snow 2000; Reference Snow, R., A. and C.Snow and Benford 1992; Reference Snow, R., P., David A., Hanspeter and Sarah A.Snow et al. 2019). To explore cutting-edge democratic innovation from below, therefore, we need to move beyond existing models and generate new typologies that integrate movement-generated democratic ideational frameworks.

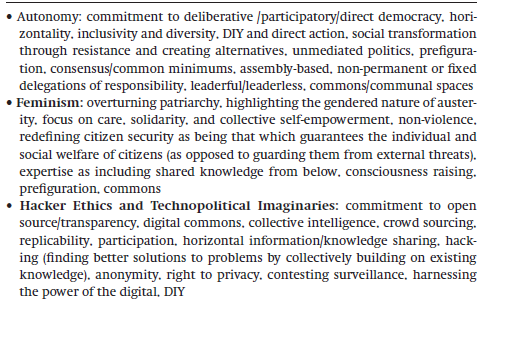

Delineating movement ideational frameworks is not an easy and neat process, as movements are heterogeneous actors that draw on multiple traditions and influences. When these frameworks interact synergistically, they can draw in a wide range of actors and develop master frames that orient collective action. These can then influence movement culture (including praxis and ideologies) and collective identity—or the sense of collective belonging and shared vision. In Spain's 15-M movement, for example, participants’ understanding of democracy encompassed at least three core ideational frameworks that merged to forge a new movement culture known as quincemayismo or 15-Mism (these core ideational frameworks are delineated in Table 1 below).Footnote 1

Table 1 Core Ideational frameworks of 15-M (reproduced from Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2020: 130)

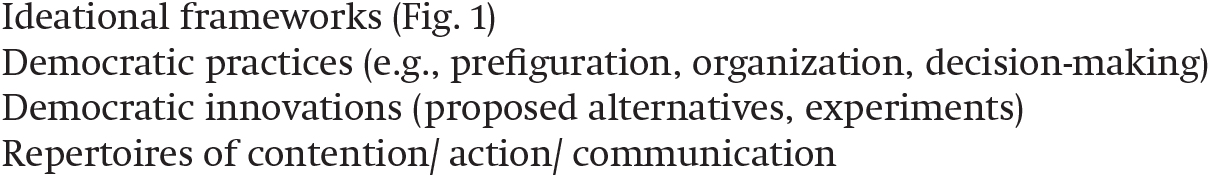

Ideational frameworks therefore play a crucial role in shaping what I term “democratic innovation repertoires” (see Figure 2). Democratic innovation repertoires encompass core ideational frameworks, democratic practices (e.g., prefiguration, organization, decision-making), democratic innovations (proposed alternatives), and repertoires of contention, action, and communication.

Figure 2 Democratic Innovation Repertoires

Introducing a more complex understanding of democracy within movements will enable us to capture the role of ideational frameworks and prefigurative practices in shaping innovation in movements and beyond (see Figure 2).

Within PDMs, activists are socialized into prefigurative democratic practices, are imbued with new imaginaries that are collectively generated through participation, build new social bonds of trust and solidarity, and develop expertise and skills in democratic innovation (Reference DianiDiani 1997; Reference MaeckelberghMaeckelbergh 2009; Reference Van Dyke and M.Van Dyke and Dixon 2013). PDMs engage in democratic innovation not only by producing new imaginaries and practices, but also new norms, expectations, skills, and practical knowledge oriented toward emancipatory social transformation and democratic regeneration (Reference Benford and D. A.Benford and Snow 2000; Reference Eyerman and A.Eyerman and Jamison 1991; Reference Cox and FlesherCox and Flesher Fominaya 2009; Reference MelucciMelucci 1996). Yet effective translation beyond movements is not a given: there has been widespread skepticism about the enduring positive effects of PDMs (Reference van de Sandevan de Sande 2013) and many of these movements appear to have faded away once the squares were emptied (Reference TufekciTufekci 2017).

Analyzing positive cases, therefore, is one way to begin to flesh out the role of movement imaginaries in producing innovative effects beyond the movement milieus (e.g., occupy camps, social centers) in which they are developed.

Capturing Movement Innovation Beyond Movement Arenas: From Movement to Institutions

Political institutions have often been considered as almost beyond the reach of social movements because they are designed to withstand change by challengers, maintain stability, and be self-perpetuating (Reference Kriesi, D., M., D. and C.Kriesi and Wisler 1999). Yet the decline of legitimacy in political institutions in times of crisis opens opportunities for movement innovators (Reference Wagner-PacificiWagner-Pacifici 2017; Reference BeissingerBeissinger 2002). Social movements can engage in “democracy-driven governance,” by which social movements attempt to “invent new, and reclaim and transform existing, spaces of participatory governance and shape them to respond to citizens’ demands” (Bua and Bussu 2020: 716).

Progressive pro-democracy movements can impact democracy by experimenting with and modelling new forms of democratic participation, incubating new democratic imaginaries, and proposing changes in political institutions to regenerate democracy. Their influence becomes more explicit and direct when activists successfully enter electoral politics. With the entrance of social movement actors into governance institutions following the global wave of PDM mobilization, there has been a resurgence of interest in new movement parties, the relation between social movements and new municipal governments, and the capacity of social movements to “save democracy” through democratic innovation in governance institutions (Reference Della PortaDella Porta 2013, Reference Della Porta2020; Reference Della Porta, J., H. and L.Della Porta et al 2017; Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2020; Font and García-Espin 2019; Reference TarrowTarrow 2021). In Spain, following the 15-M mobilizations, many activists participated in the new municipalism for change, a series of movement-based coalitions that ended up governing Madrid, Barcelona, and other Spanish cities in 2015. As carriers of movement innovation, the types of ideational frameworks activists subscribe to are likely to have an impact on post-mobilization innovation. Research by Reference Romanos and IgorRomanos and Sádaba (2015) has suggested that an affinity for digitally-enabled democratic frameworks and a belief in the power of digital tools for democratic innovation in Spain's 15-M Indignados movement facilitated the transition from movement to movement-party for many activists when they supported the hybrid party Podemos and the new municipalist movement coalitions. In earlier work (Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2020), I have shown how the integration of movement imaginaries into party “promises” enabled movement support for newcomer party Podemos in Spain following widespread post-2008 anti-austerity mobilizations, illustrating movement influence on party innovation in its early stages.

The democratic innovation introduced by 15-M activists into the institutional arena in Spain's major cities through Barcelona en Comú (Barcelona) and Ahora Madrid coalitions is well documented, and includes participatory budgets and experimentation with citizens’ assemblies based on random selection that is designed to put forward proposals and to intervene in designing public policies (Reference Calleja, J. and L.Calleja and Toret 2019; Reference Font, P., Cristina and RamónFont and García-Espín 2020; Reference Ganuza and A.Ganuza and Mendiharat 2020; Nez and Ganuza 2020). But only focusing on the procedural aspects of innovation misses the deeper influence of imaginaries on democratic innovation. The technopolitical imaginaries of 15-M strongly influenced Barcelona en Comú's and Ahora Madrid's policy agenda (Reference Barandiaran, L., A. and A.Barandiaran 2019; Reference Calleja, J. and L.Calleja and Toret 2019). The influence of Spain's pro-democracy movement on the new municipalism was also encompassed in the much broader desire to create “democratic cities” (Reference Roth, A. and A.Roth, Monterde, and Calleja-López 2019)—a goal in which multiple democratic imaginaries were given reign. The 15-M movement's strong ideological and practical commitment to “the commons” that formed a core element of their democratic imaginaries (see Table 1) also deeply influenced the discourse and policies of so-called radical municipalism when former activists in the movement assumed the leadership of governing coalitions across Spain in 2015. Although more attention has been paid to procedural (organs and processes) innovations such as the participatory mechanisms of Decidim Barcelona or Decide Madrid (Reference Barandiaran, A., A., P., J., C. and A.Barandiaran et al. 2017; Reference Peña-LópezPeña-López 2017), the shift toward commons thinking (i.e., prioritizing citizen welfare over private interests) as the criteria against which policies can be evaluated can also be seen as a fundamental democratic innovation. Barcelona en Comú adopted policies that attempted to foster co-operative business models and the solidarity economy (Reference Bua and S.Bua and Bussu 2020; Reference Roth, A. and A.Roth, Monterde, and Calleja-López 2019;). The movement commitment to feminism as a crucial component of a radical democratic imaginary, which was explicitly adopted as a core policy criterion (i.e., a core democratic principle), is another example of how movement imaginaries can lead to democratic innovation beyond movement arenas (Reference Cruells, E., L., A. and A.Cruells and Alfama 2019; Reference Roth, L., Ciudades, L., A. and A.Roth and Rosich 2019). The “feminization” of politics within progressive electoral political spaces, (which I have suggested elsewhere is more accurately termed the feminist-ization of politics, Fominaya 2020) has led to a profound shift in how politics and democracy are defined, including a change in the understanding of good leadership (e.g., a positive promotion of collective leadership, leadership based on effectiveness rather than knowledge or opinion, and leadership based on the ability to coordinate and bring together), and a reprioritization of the common good and care for the most vulnerable (Fominaya 2020; Reference Roth, L., Ciudades, L., A. and A.Roth and Rosich 2019).

Capturing the Influence of Social Movements on Democratic Innovation in the Face of New Challenges

The difficulties in capturing the impact of social movements (Reference Giugni, D. and C.Giugni et al. 1999; Reference Passy, G.-A., D., S., H. and H.Passy and Monsch 2019) become greater the farther we move away from periods of visible mobilization. The afterlives of social movements are relatively “invisible” compared to periods of mobilization, yet sustained and influential movements continue to exert myriad effects on politics, society, and culture long after mobilization has waned (Ross 2008). Scholars agree on the crucial importance of understanding the afterlives of movements yet they tend to shy away from the significant methodological and conceptual challenges it presents (Reference Giugni, D. and C.Giugni et al. 1999; Reference Tilly, M., D. and C.Tilly 1999). Most work has focused on the more easily measured short-term policy or legislative impacts of social movements, rather than their broader, more diffuse, and longer term political, social, cultural, and biographical impacts (Reference GiugniGiugni 2008). This is why genealogical approaches to the afterlives of movements is important. One area that is rich for exploration is the impact of prefiguration in democratic innovation post-mobilization and beyond movement arenas.

Prefiguration has been extensively studied as a social movement practice, but curiously, despite its emphasis on future oriented action, there has been no work done on whether or how prefigurative practices have affected movement outcomes post-mobilization, either in new non-movement arenas of action or during new periods of mobilization. Because prefigurative practice involves experimentation with alternative social and organizational forms, it is therefore an important potential source of democratic innovation. There is evidence that movements do draw on the skills and problem-solving approaches developed in their laboratories to address new challenges and democratic deficits. I briefly turn to two examples now, drawing on research addressing mobilization during the coronavirus pandemic, to illustrate how future research could use the framework of movement democratic innovation repertoires to develop our understanding of the role of social movements in democratic innovation in times of crisis, whether addressing democratic deficits from below or directly engaging with governing institutions and actors.

Hong Kong and Taiwan: Pro-Democracy Movements Address COVID-19

One example of how pro-democracy movements’ afterlives can innovate post original mobilization comes from Hong Kong's citizen response to the democratic deficit shown by leadership in the face of the coronavirus pandemic arrival in early 2020.Footnote 2 In this case Hong Kong's leaders were slow to react, or to put in place effective containment strategies, jeopardizing citizen health and safety. In response, veterans of the pro-democracy movements that formed part of the long global wave of protests following the global financial crash of 2008 used the innovative tools and resources they had developed during their pro-democracy protest activity in 2019 to respond to the new crisis. Activists in the Umbrella movement had developed strategies of coordination with one another on matters including supply reallocation “and frontline defense through network infrastructures (online collaboration tools and peer-to-peer messaging)” as well as extensive and highly coordinated voluntarism (Reference Cheng and W.-Y.Cheng and Chan 2017: 234).

In the face of the new crisis, they transferred their pro-democracy demands for accountability and their commitment to civil disobedience and collective self-organization to a new challenge. In the face of the pandemic, they used digital maps to track and trace the spread of the virus and mobilized their communication networks to keep citizens informed with the latest WHO information. Citizen volunteers were organized to distribute masks and hand sanitizers in open defiance of the government's ban on masks (Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2022; Tufecki 2020). They were able to address these challenges even in a repressive environment in which there is little space available for democratic expression. The response to the crisis from both leadership and activists was entwined with the struggle over democratic freedoms. Hong Kong had outlawed the wearing of face masks before the eruption of the coronavirus pandemic in 2019, because pro-democracy protesters had used them to avoid surveillance, arrest, and retribution (Reference Hartley and D.Hartley and Jarvis 2020). Hong Kong's chief executive's refusal to wear a mask and directive for the executive to also refrain was not simply a statement about the science of mask wearing as a preventive measure, but a political statement. When the people of Hong Kong responded by wearing masks almost wholesale, they too were making a political statement and representing their desire for greater democratic freedoms. The pro-democracy activists involved in initiating and coordinating these actions were drawing on their movement practices, inspired by democratic imaginaries, to address a new challenge and a new manifestation of governmental democratic deficit (Reference ChengCheng 2020; Reference ChowChow 2020; Reference Hartley and D.Hartley and Jarvis 2020; Tufecki 2020). Democratic innovation involves not only providing new alternatives but also effectively addressing democratic deficits.

In contrast to the oppositional case of Hong Kong's PDM activists, the case of Taiwan demonstrated how the afterlives of mobilization can lead to a transfer of democratic imaginaries and practices that directly influence government policy and response. In this case, an important precursor was the Sunflower Movement, which started with the protest occupation of Taiwan's national legislature in 2014, involved “creative collaboration by dispersed, but experienced activists” (Ho 2017: 189) to try to prevent the ruling party's free trade agreement with China, and eventually evolved into a mass movement associated with a longer standing struggle for democracy. Taiwan's success story of responding to the COVID-19 pandemic owes much to the rapid response and sustained input of the g0v (gov zero) civic tech activist community that mobilized in the Sunflower Movement in 2014, and the leadership of the Minister for Digital Affairs, Audrey Tang (an activist in the movement), and her team.Footnote 3 Their digitally-enabled, networked democratic innovation repertoires were repurposed to face a new challenge. Together they warned the government about the risk of the virus before the WHO made any announcement. They used numerous platforms, tools, and protocols to inform citizens, ensure effective distribution of masks, and develop effective digital strategies to combat misinformation about the virus and increase citizen trust in the authorities and compliance with health and safety containment measures (Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2022). G0v builds open-source tools and civic-tech services to facilitate a flow of ideas and information between civil society and government. The result has been increased public trust, compliance, and collaboration, and an efficient and effective response to the challenges posed by the pandemic (Reference Lee, S.-C., T.-Y., C.-M. and C.Lee et al., 2020; Reference LeonardLeonard 2020; Reference TangTang 2020; Reference TworekTworek 2020).

Taiwan's response to the pandemic is another demonstration of how the democratic imaginaries and practices of the Sunflower Movement—democratic means (decentralized, participatory, networked, self-organized collaboration) harnessed for democratic ends (a robust democracy that meets the needs of its citizens)—and the activist civic tech communities that nourished and were nourished by the movement can live on beyond the original context and arena of the origin mobilization “event” and can go on to develop democratic innovations in the face of new challenges. Crucial to the response was the deep belief in and propagation of democratic ideals and actively combatting threats to democracy: an informed citizenry combatting disinformation, open government, participatory mechanisms, safeguarding citizen welfare, coordinating action for effective and transparent responses to the pandemic, ensuring the most vulnerable are cared for, etc.

Conclusion: Reconceptualizing Democratic Innovation through the Lens of Social Movements

Democratic innovation is mostly conceptualized as an institution-driven top-down process in which actors and governing institutions attempt to close the gap between institutions and citizens to strengthen some aspect of democracy. In this article, I have argued that such a top-down approach radically limits our ability to understand the sources, natures, and dynamics of democratic innovation. Instead, I have argued that more attention needs to be paid to the crucial role social movements can play in democratic innovation during and beyond mobilization, and have offered a framework for exploring democratic innovation repertoires in social movements and their afterlives. Movements are not self-contained phenomena. Their influence extends across space and time. Peak periods of mobilization create spillover effects (Reference Meyer and N.Meyer and Whittier 1994) not only through their influence on other movements, but also their influence on non-movement actors and arenas. Activists are carriers of innovation: they develop experience, skills, and imaginaries that they then carry into other arenas of society, including, but not limited to, government institutions.

In this article, I have first highlighted the lack of attention to social movements’ imaginaries, ideational frameworks, and democratic innovation repertoires in the study of democratic innovation, which has been dominated by a policy and procedural focus. I have also called attention to the surprisingly understudied nature of the afterlives of prefiguration in social movement studies. While my focus here has been on the relation between social movements and democratic innovation in times of crisis, the call for more attention to the long-term impacts of prefiguration extends beyond this specific focus.

In response to these lacunae, I have called for an awareness and study of the crucial role of prefiguration and imaginaries in non-formally organized movements as potentially important sources of democratic innovation that live on beyond mobilization events and movement arenas. I have introduced the concept and analytical framework of democratic innovation repertoires as a means of capturing the interplay between imaginaries, ideational frameworks, and praxis and their role in innovation in pro-democracy movements specifically, although the same approach can be used to capture and analyze innovation in other arenas of movement action.

Second, I have argued that, in contrast to the imposition of classical and formal procedural models of democracy on the heterogeneous nature of most progressive and autonomous social movements, we should pay attention to their focus on substantive conceptions and fuzzy models. This includes an awareness of their problem-solving orientations and their diagnoses of key democratic deficits.

Adopting this approach is not without significant challenges and requires alternative methods such as ethnography and discourse analysis, and an awareness of the synthesis and contradictions between diverse movement traditions and ideational frameworks and forms of praxis. I have offered an example of what this approach might look like, and what elements might be interrogated, drawing on my research into Spain's 15-M movement (see Figures 1 and 2).

Finally, as we saw in the case of the movement responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong and Taiwan, we must extend our understanding of the outcomes of social movements beyond policy arenas and beyond the immediate context of mobilization. We need to better understand how movement imaginaries and innovation repertoires travel and evolve across time and space. Adopting genealogical approaches that capture continuities between different periods of mobilization and process-tracing that enables an understanding of the origin stories and influences of innovation are two key methodological approaches that will enable a much more robust and nuanced understanding of the role of social movements in democratic innovation, and of democratic innovation more broadly. As these two examples reveal, it is not just a question of movements “pivoting” and using their skills, resources and techniques to tackle new problems or deficits, such as in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is that these movements frame and understand their activity within an understanding of the need for democratic innovation and regeneration: they draw on their democratic imaginaries and visions to address these challenges in new ways. While these two examples are positive ones, it is by no means a given that movements will generate afterlives that lead to democratic innovation, or indeed that attempts at innovation will be successful. Documenting movement influence on democratic innovation is not the same as evaluating the success of innovation. For their part, governmental COVID-19 responses (and government responses to all crises) are intrinsically tied to indicators of democratic health (Reference Afsahi, Emily, Rikki, Selen A. and Jean-PaulAfsahi et al. 2020; Reference Flesher FominayaFlesher Fominaya 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic has unleashed a cascading series of crises whose effects will be with us for a very long time (Reference Robinson, Jeremy, Christopher, Cara, Matías, Jessica and Kuo-TingRobinson et al. 2021). It is my hope that these insights will prompt a better understanding of how social movements can contribute to democratic innovation in these times of crisis, and a greater dialogue between democratic theory and social movement studies.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Ramón Feenstra and Martin King for pointing me to some of the literature cited in this article. Thanks also to Aidan McGarry, Ruth Kinna, and Pierre Monforte for feedback on earlier versions of some sections of this article.