1 Introduction

Will the final theory of physics be written in the language of quantum field theory (QFT)? This was the question debated by two men at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton on January 22, 1949. The two interlocutors could hardly have been more aptly chosen: In 1930, the older of the two, J. Robert Oppenheimer – now director of the institute and known around the world as the father of the atomic bomb, but back then a young postdoc in Zurich – had established that QFT was fatally flawed. He had calculated the corrected values for the spectral lines of hydrogen in the quantum field theory of electrodynamics and had found them to be infinite (Oppenheimer, Reference Oppenheimer1930). Some 20 years later, Freeman J. Dyson – a PhD student of sorts, though he never ended up graduating – had just written the definitive paper on how these infinities could be removed in a systematic procedure called renormalization, delivering a theory of quantum electrodynamics (QED) that returned sensible and empirically highly accurate predictions, in particular for the spectral lines of hydrogen (Dyson, Reference Dyson1949a). One man had led fundamental physics into two decades of soul-searching; the other had led it out again.

Neither of the two was particularly happy with renormalized quantum field theory. In a letter to his parents – our only source on the discussion with Oppenheimer (Dyson, Reference Dyson2018, p. 136) – Dyson remarked that “we are agreed that the existing methods of field theory are not satisfactory and must ultimately be scrapped in favour of a theory which is physically more intelligible and less arbitrary. We also agree that the final theory should explain why there are the various types of particles we see and no more.” However, Oppenheimer and Dyson disagreed on how and when this “final theory” would be achieved. According to Dyson, “Oppenheimer believes that the nature of the nuclear forces will itself give us enough information on which to build the new theory,” that is, he believed that the next great transformation of fundamental physics (and presumably the final one) was right around the corner and was to be found in the detailed study of nuclear physics, a scientific endeavor that the postwar United States was pursuing with unparalleled resources. Dyson, on the other hand, believed that “we shall be able to give a complete account of the nucleus on the basis of the present field theory,” that is, that a renormalized QFT for the nuclear interactions could be constructed following the example of QED and that “the discovery of a finally satisfactory theory of elementary particles will be a much deeper problem than those we are tackling at present and may very well not be achieved within the framework of microscopic physics.”

It is uncontroversial that history proved Oppenheimer wrong: less than 30 years later, the Standard Model of Particle Physics was established, encompassing quantum field theories for both the strong and weak nuclear interactions. It is, however, hard to see the events that followed the discussion in Princeton as a vindication of Dyson’s position. The program that Dyson pursued afterwards was equally a failure: he attempted to show that renormalized QED was a “complete and consistent theory” (Dyson, Reference Dyson1952, p. 631) that could thus serve as a blueprint for quantum field theories of the nuclear interactions – only to find the consistency of QED to be an elusive statement that he could neither prove nor disprove. Thus began one of the most curious stories in the history of modern physics. Quantum electrodynamics came to be hailed as the most precise theory in the history of physics, famously delivering a theoretical prediction for the

![]() -factor of the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron that has been confirmed experimentally to 5 parts in a trillion (Hanneke et al., Reference Hanneke, Hoogerheide and Gabrielse2011). Richard Feynman considered QED (which, of course, he himself had helped develop) as “the jewel of physics – our proudest possession” (Feynman, Reference Feynman1985, p. 8). Yet Dyson and those that followed him were not just unable to prove the mathematical consistency of this theory, they were equally unable to prove its inconsistency. This two-volume Element recounts the story of these attempts, of how our arguably best physical theory ended up, and remained, in mathematical limbo. It follows this story from Dyson’s first forays in the late 1940s to Kenneth Wilson’s renormalization group analysis in the mid 1960s.

-factor of the anomalous magnetic moment of the electron that has been confirmed experimentally to 5 parts in a trillion (Hanneke et al., Reference Hanneke, Hoogerheide and Gabrielse2011). Richard Feynman considered QED (which, of course, he himself had helped develop) as “the jewel of physics – our proudest possession” (Feynman, Reference Feynman1985, p. 8). Yet Dyson and those that followed him were not just unable to prove the mathematical consistency of this theory, they were equally unable to prove its inconsistency. This two-volume Element recounts the story of these attempts, of how our arguably best physical theory ended up, and remained, in mathematical limbo. It follows this story from Dyson’s first forays in the late 1940s to Kenneth Wilson’s renormalization group analysis in the mid 1960s.

Over the course of these two decades, we observe a considerable amount of variety and change: different notions of consistency, different methods for probing it, different conclusions regarding the consistency of QED. It is thus far from obvious what should be included in a history of – as promised in this Element’s title – the attempts at probing the consistency of QED. Given the fact that this is largely uncharted historiographical territory, given the technical complexity of the issues, and given the exponential growth of post-WWII high-energy physics, a certain amount of arbitrariness, idiosyncrasy, and teleology in the selection of material is likely inevitable. Still, I hope that there are clearly discernible themes running through the narrative presented here, and I will attempt to sketch them in the following.

It is easiest to begin by stating what this Element is not about. As we have seen, both Oppenheimer and Dyson were “agreed” that renormalized QED was unsatisfactory in some profound sense. This discontent was primarily due to the renormalization procedure itself and was shared to some extent by most physicists at the time. Many physicists continued to harbor such doubts for a long time, most prominently Paul Dirac, one of the founding fathers of QED. Indeed, Dirac’s last paper (published posthumously) was entitled The Inadequacies of Quantum Field Theory. But it was merely concerned with criticizing the renormalization procedure as “these rules for subtracting infinities” or “just a set of working rules, and not a complete dynamical theory at all” (Dirac, Reference Dirac, Kursunoglu and Wigner1987, p. 196). This form of criticism is widely considered to have been made obsolete by the Wilsonian interpretation of renormalization and the rise of the effective field theory paradigm, which took shape in the 1970s (Cao and Schweber, Reference Cao and Schweber1993). In any case, it is not the sort of criticism I will be discussing in this Element. Dyson, for one, acknowledged the imperfections of the renormalization procedure, but still set out to prove the consistency of the renormalized theory. The inadequacies of QFT that I will address here, such as the nonconvergence of the perturbation series discovered by Dyson, are not inadequacies of the renormalization procedure, but rather inadequacies of QED that persisted even if one took the renormalization procedure for granted. To be clear, many of the physicists discussed in this Element explicitly attempted to prove QED inconsistent and were motivated to do so by their dissatisfaction with the renormalization procedure. But these physicists – such as, most prominently, Wolfgang Pauli – attempted to undermine renormalization by proving the inconsistency of renormalized QED, not, like Dirac, by merely pooh-poohing the renormalization procedure.

Our focus will thus be on physicists who took the existing structure of QED for granted and analyzed this structure to ascertain whether it conformed to certain criteria of consistency. This excludes the attempts at abandoning the field-theoretic approach to microscopic physics altogether, such as, most notably, the autonomous S-Matrix program (Cushing, Reference Cushing1990). It also excludes the many attempts at modifying the structure of QED in order to make sure that it conforms to certain criteria of consistency. This line between analyzing existing structures and constructing new ones is not always easy to draw. We will see the emergence of new approximation methods and renormalization procedures; we will also see the construction of new toy models, explicitly designed to reproduce certain structural features of QED. We will even see early attempts at constructing an entirely new, manifestly consistent (or inconsistent), axiomatic foundation for QFT – an approach that grew into an entire subdiscipline of its own. This Element aims to showcase the impact these innovations had on the consistency question, while minimizing discussion of their wider relevance.

There is one thing that all of these varied approaches to probing the consistency of QFT had in common: they were an objective failure. No hard-and-fast inconsistency proof was obtained, nor was the consistency of QFT conclusively proven. In fact, you can win yourself one million dollars from the Clay Mathematics Institute by “producing a mathematically complete example of quantum gauge field theory in four-dimensional space-time.”Footnote 1 What, then, can we learn from this history of failure?

To answer this question, we first need to consider what sorts of insights physicists had expected to gain from investigating the consistency of QED – had they been successful in proving either the consistency or the inconsistency of the theory. We will, of course, encounter some individual and very idiosyncratic expectations and motivations throughout this Element; but some more general observations can be made. At first glance, one might well consider either outcome of these investigations as trivial. What could a proof of mathematical consistency add to the theory’s flawless empirical track record? Conversely, how could a proof of mathematical inconsistency undermine a theory that was anyhow awaiting repeal from a theory of the nuclear forces? The modern reader may even find the entire preoccupation with inconsistency misplaced, having come to accept inconsistency in physical theories as a fact of life.Footnote 2 But we must not fall into the trap of misreading this whole debate as a purely philosophical one. As Dyson’s letter already suggests, the consistency of QED itself was not the fundamental issue; the central problem was always the construction of a theory of the strong nuclear interactions.Footnote 3

What was the role of the (in)consistency of QED in deciding this issue? The answer is rather simple: a consistency proof would have established QED as a blueprint for a theory of the strong nuclear interactions. Now, of course, QED had been used as a blueprint for theories of the nuclear interactions early on; both Fermi’s theory of beta decay and Yukawa’s meson theory had been crafted in explicit analogy to QED.Footnote 4 Fermi’s theory had long been known to exhibit perturbative divergences that were worse than those of QED (Blum, Reference Blum2017, section 1.1), and it was soon found that the methods used to renormalize QED could not be applied to it (Kamefuchi, Reference Kamefuchi1951). To a zeroth approximation, the history of the weak interactions can be read as the search for a better, renormalizable (and thus more QED-like) model, culminating in the construction of the electroweak Standard Model. That development is rather orthogonal to the focus of this Element, and the weak interaction will play little role in what follows.Footnote 5

The problem with the strong interaction was quite different. There were versions of Yukawa’s theory that were clearly renormalizable. The main difference between the strong and the electromagnetic interactions was that the former are – and this was evident long before their current name was adopted – very strong in spite of their short range, that there is an “extraordinary tendency of

![]() nuclei to react with each other as soon as direct contact is established” (Bohr, Reference Bohr1936, p. 344). But the calculations that underlay (and to this day underlie) the successful empirical predictions of QED relied on a weak coupling approximation. In fact, the entire renormalization procedure, which removed the infinities appearing in the theory, was formulated only within the framework of this perturbative approximation. One could, of course, simply ignore this difficulty and apply QED-style perturbation theory to Yukawa’s field theory of the strong interaction, but this approach did not meet with much success.Footnote 6 Probing the consistency of QED thus meant finding out whether there was actually a full-fledged theory behind this approximation scheme – something that was being approximated, a framework that could be extended beyond the case of weak coupling to describe the strong interaction and ultimately provide the language for a final theory.

nuclei to react with each other as soon as direct contact is established” (Bohr, Reference Bohr1936, p. 344). But the calculations that underlay (and to this day underlie) the successful empirical predictions of QED relied on a weak coupling approximation. In fact, the entire renormalization procedure, which removed the infinities appearing in the theory, was formulated only within the framework of this perturbative approximation. One could, of course, simply ignore this difficulty and apply QED-style perturbation theory to Yukawa’s field theory of the strong interaction, but this approach did not meet with much success.Footnote 6 Probing the consistency of QED thus meant finding out whether there was actually a full-fledged theory behind this approximation scheme – something that was being approximated, a framework that could be extended beyond the case of weak coupling to describe the strong interaction and ultimately provide the language for a final theory.

Such a framework was not found. Instead, physicists discovered a cornucopia of problems with renormalized QED, including the divergence of the perturbation series, Haag’s theorem, and the Landau pole. These issues continue to be central in discussions on QFT today. By introducing these problematic aspects of QFT not in an abstract way, but by showing how they actually arose in practice, this Element also hopes to provide some clarification regarding the foundational status of QFT – not by asserting what the real problems of QFT are, but by emphasizing what was (and is) a problem for whom trying to do what. Once readers have seen these problems in action, they will hopefully be able to form a clearer opinion of their respective significance.

None of the problems discussed in this Element amounted to a full-fledged inconsistency proof (though several claims to that effect were made), but they contributed to a widespread distrust of QFT. This distrust led to the exploration – and even the dominance – of non–field-theoretic approaches to the strong interaction beginning in the mid 1950s, such as the aforementioned S-Matrix approach. However, in probing the consistency of QED, physicists gained more than just a typology of problems. Four key insights will emerge in the course of this Element: (i) the consistency of QED was intimately connected to its short-distance behavior; (ii) at short distances, it was charge renormalization (rather than mass renormalization, i.e., self-energy) that played the critical role in assessing the consistency of QED; (iii) there were several shades of gray between the black and white of consistency and inconsistency; and (iv) on this spectrum of consistency, there was room for models that fared far better than QED, in contrast to what both Oppenheimer and Dyson had expected.

It was hardly unreasonable to expect that QED would be the optimal field theory; not only did it originate from Maxwell’s electrodynamics, the original field theory, but it had also just celebrated the splendid triumphs of the late 1940s, which earned Richard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga the Nobel Prize in 1965. This triumph was vividly depicted by Sam Schweber (Reference Schweber1994), and this Element can be considered a sequel of sorts to his QED, chronicling the decline and fall of that theory. At the same time, it presents a prehistory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the quantum field theory of the strong interactions that was adopted in the 1970s. Complementing other prehistories of QCD that trace the development of attempts to describe the strong interactions (Cao, Reference Cao2010), this Element will show how certain problematic aspects of the short-distance behavior of QFT came into the focus for theoretical physicists.

When QCD was shown to be asymptotically free in 1973, this killed two birds with one stone: it explained the presence of point-like constituents in nucleons, as observed in deep inelastic scattering experiments, and it demonstrated that the theory did not encounter the high-energy difficulties found in QED (Gross, Reference Gross, Gotsman, Ne’eman and Voronel1990, p. 101). The first aspect was the crucial one in the discovery of asymptotic freedom and probably also in the acceptance of QCD as a theory of the strong interactions. But it was the latter aspect that ultimately made QCD the theoretical gold standard in QFT – less precise in its predictions than QED, but more likely to be a consistent theory. While a rigorous mathematical existence proof is still outstanding, it is no coincidence that the aforementioned Clay Millennium Problem explicitly demands such a proof for a (QCD-style) quantum Yang–Mills theory (rather than, say, an abelian gauge theory like QED).Footnote 7

That would pretty much sum up the scope of this Element – as well as its temporal horizon, spanning from the development of renormalized QED in the late 1940s to the mid 1960s and the eve of the SLAC experiments that first hinted at asymptotic freedom – if it weren’t for one thing: what exactly is meant by this word “consistency” that I keep bandying about? Historians might worry about whether it is an analytical category, designed to lump together a variety of historically distinct debates, or a category used by the historical actors themselves. This question can be answered rather easily: the reader will frequently encounter explicit references to consistency in historical quotes throughout this Element. Not everyone liked to use the concept of consistency; but it was used frequently enough that I can confidently state that the debate chronicled in this Element was widely regarded as a debate about the consistency of QED.

Philosophers, in turn, may worry that the historical actors invoked the concept of consistency somewhat too readily. I will be generous in this regard, and in general it will be possible to reconstruct the historical arguments as genuinely concerning questions of consistency. That is not to say that there was a universal or unchanging definition of (in)consistency underlying this debate. To the contrary. The historical development provides ample opportunity to analyze the varied notions of (in)consistency that were in play, and, toward the end, to reflect on their relevance and interrelations. This final focus of the Element will ultimately take us beyond the immediate concerns of the historical debate on the consistency of QED and allow us to draw broader philosophical lessons on the mathematical and logical structuring of knowledge in modern fundamental physics – arguably the most formalized of all the sciences.

But first, we return to Dyson. In Section 2, we will see him attempting to demonstrate the consistency of renormalized QED by showing that the known approximate solutions actually approximated exact ones – and ultimately we will see him fail, because of the divergence of the perturbation series. This theme – the impossibility of proving the consistency of QED – is then continued throughout the first volume of this Element.

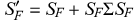

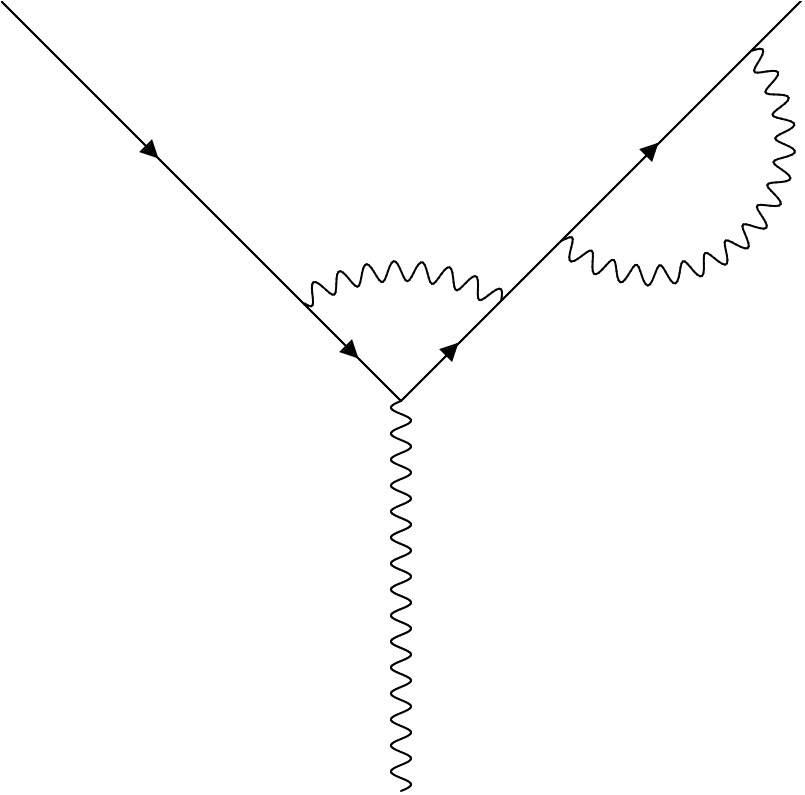

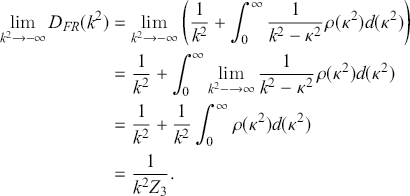

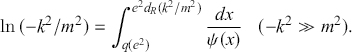

After Dyson’s failed attempt, it was clear that one had to go beyond perturbation theory in order to investigate the consistency of QED. In Section 3, I will look at the attempts to construct exact solutions in QED nonperturbatively. As we shall see, this goal ultimately became elusive, as the traditional dynamical equations of quantum theories (Schrödinger equation or Heisenberg equations of motion) were replaced in QFT by an infinite set of coupled integro-differential equations – the Schwinger–Dyson equations. At best one could investigate whether hypothetical nonperturbative solutions still contained the infinities that were removed through renormalization in the perturbative framework. In Section 4, we will discuss Gunnar Källén’s proof that at least one of the renormalization constants was infinite also nonperturbatively. This issue was then connected to the finiteness of QED for short distances (or, equivalently, high – “ultraviolet” – energies) through the renormalization group methods developed by Murray Gell-Mann and Francis Low. With a construction of exact solutions to the Schwinger–Dyson equations out of the question, several physicists in the mid 1950s attempted to address the question of consistency on a different level by exploring the axiomatic foundations of QFT. I will discuss this approach in Section 5, focusing on the emergence of one of the central challenges for axiomatic QFT, Haag’s theorem.

The second volume of this Element to be published in this series, is primarily concerned with the discovery of actual – though ultimately inconclusive – inconsistencies. At first such inconsistencies were discovered in simpler model QFTs, where exact solutions (of the Schrödinger equation) could still, in principle, be constructed. The discovery of pathological solutions in one such model QFT, the Lee Model, is the subject of Section 1 (of the second volume). Exact solutions for QED remained out of reach, but similar pathologies were discovered in approximate (though nonperturbative) solutions to the Schwinger–Dyson equations. This so-called Landau pole is discussed in Section 2.

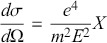

By the late 1950s, a handful of central difficulties in proving the consistency of QED had thus been established: the divergence of the perturbation series, ultraviolet finiteness, Haag’s theorem, and the Landau pole. However, the fundamental status of these difficulties remained disputed. We will look more closely at the ensuing debates, on the Landau pole (Section 3) and on ultraviolet finiteness (Section 4). In both cases, a consensus emerged that the original claims by Landau and Källén, respectively, had probably been overstated. Nonetheless, a final attempt in the mid 1960s by Kenneth Johnson, Marshall Baker, and Raymond Willey to prove the consistency of QED also ended in failure. Quantum electrodynamics appeared to be a lost cause; but it became clear through these investigations that there might actually be QFTs that fared better than QED, in particular with regard to their short-distance behavior. Kenneth Wilson’s first explorations of this possibility will be examined in Section 5. We will see how Wilson formalized the study of the ultraviolet (UV) behavior of QFTs by introducing the concept of a running coupling constant, thereby setting the stage for the subsequent discovery of asymptotic freedom. Having thus reached the end of the story, Section 6 will present my reflections on the continued relevance of the consistency debate and the diverse attitudes toward inconsistency that we will encounter throughout this Element.

To arrive at these conclusions, we must venture deep into the quagmire that is the formalism of QFT, widely regarded as complex and recalcitrant; indeed, that complexity and recalcitrance is largely what this Element is about! I have aimed to make this Element accessible to readers who have attended an introductory course in QFT, have seen a field operator and the derivation of the Feynman rules. In fact, I even hope that this Element can also serve as an introduction of sorts to those more problematic aspects of QFT that are not usually addressed in introductory courses. And with that final disclaimer, we return to where this introduction began, the year 1949 and the brave new world of renormalized QED.

2 The Divergence of the Perturbation Series

2.1 Inconsistency in QED before Renormalization

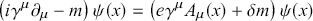

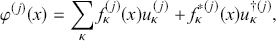

Quantum electrodynamics is the relativistically invariant theory of electrons and positrons (represented by a fermionic Dirac field

![]() ) interacting with the electromagnetic field (represented by the four-vector potential

) interacting with the electromagnetic field (represented by the four-vector potential

![]() ).Footnote 8 The foundational equations of QED – the Lagrangian and the field commutation relations – were first written down in the late 1920s by Werner Heisenberg and Wolfgang Pauli, in the immediate aftermath of the development of quantum mechanics (Heisenberg and Pauli, Reference Heisenberg and Pauli1929). Quantum mechanics primarily dealt with the energy levels of material systems, such as atoms; QED was supposed to extend it into a theory that could also treat transitions from one level to another, and the accompanying emission or absorption of electromagnetic radiation, in a fully dynamical manner.Footnote 9 Quantum electrodynamics fulfilled these expectations well enough to first order in perturbation theory, that is, for the first term in a series expansion in powers of the fine structure constant

).Footnote 8 The foundational equations of QED – the Lagrangian and the field commutation relations – were first written down in the late 1920s by Werner Heisenberg and Wolfgang Pauli, in the immediate aftermath of the development of quantum mechanics (Heisenberg and Pauli, Reference Heisenberg and Pauli1929). Quantum mechanics primarily dealt with the energy levels of material systems, such as atoms; QED was supposed to extend it into a theory that could also treat transitions from one level to another, and the accompanying emission or absorption of electromagnetic radiation, in a fully dynamical manner.Footnote 9 Quantum electrodynamics fulfilled these expectations well enough to first order in perturbation theory, that is, for the first term in a series expansion in powers of the fine structure constant

![]() .

.

This first-order approximation was sufficient for most problems, in particular for calculating the probability amplitude for an atom to perform a transition. Second-order perturbation theory, in addition to providing small corrections to the results of first-order calculations, also introduced an effect of the radiation field on the energy levels of the atom itself. Here things started to go wrong. Quantum mechanics by itself provided very accurate predictions for the hydrogen spectrum and its fine structure. Instead of predicting small, hitherto unobserved displacements in this spectrum, calculations in QED predicted displacements of infinite magnitude (Oppenheimer, Reference Oppenheimer1930).

There has been a fair amount of historical scholarship on this early period of quantum field theory up to and including the development of renormalization methods. My detailed historical reconstruction will thus only begin after the first successes of renormalized QED, around 1948. In this first section, I will instead take more of a bird’s-eye view, addressing how the problem of the consistency of QFT was viewed in its first two decades. In this, I will refrain from making overly general statements about inconsistency in physical theory. Peter Vickers (Reference Vickers2013, p. 15) has cogently argued that “some of the things we call ‘theories’ will have different characteristics, such that inconsistency means something different in each case.” His method of analyzing inconsistency in science is not to engage with the structure of theories as a whole, but to identify a set of propositions relevant to the claimed inconsistency. Such a set of propositions can be equivalent to the entire theory, but it doesn’t have to be. For QED, writing down such a relevant set of propositions is deceptively simple: it consists of (

![]() ) the basic tenets of quantum mechanics (as would have been found at the time in the textbooks by Dirac [Reference Dirac1930] or von Neumann [Reference von Neumann1932]) combined with (

) the basic tenets of quantum mechanics (as would have been found at the time in the textbooks by Dirac [Reference Dirac1930] or von Neumann [Reference von Neumann1932]) combined with (

![]() ) the specific dynamical variables of QED and the dynamical equations they obey. In the Heisenberg picture, these were given byFootnote 10

) the specific dynamical variables of QED and the dynamical equations they obey. In the Heisenberg picture, these were given byFootnote 10

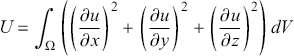

(1)

(1)

From these propositions, Oppenheimer’s result of infinite frequencies for the spectral lines could be deduced, along with similarly infinite results for other observable quantities. Alexander Rueger (Reference Rueger1992) has mapped out several “Attitudes towards Infinities” adopted by physicists in the 1930s. He points toward Heisenberg’s attempts at providing a physical interpretation of the infinities. But apart from these unsuccessful and unpublished attempts of the mid 1930s, there was a general consensus among physicists that the appearance of infinities in QED directly implied the theory’s inconsistency.

Let us try to spell out the inference from the calculated infinities to the inconsistency of QED more explicitly. One might simply interpret it as an inconsistency between QED and empirical facts – after all, the frequencies of the spectral lines of hydrogen had been measured with definite, finite values. In this case, the inconsistency referred to by the historical actors would amount to nothing more than empirical inadequacy. However, the real problem was not that the infinities predicted by QED did not reproduce the observed spectra, but that they could not. A spectral line of infinite frequency was considered a contradiction in and of itself, without recourse to the frequency actually measured.Footnote 11 Physicists were thus implicitly invoking a more general meta-theoretical criterion that did not rely on empirical facts.

What should we take this implicit criterion to be? A first attempt might be to add the claim (

![]() ) “observable quantities do not take infinite values” to the initial set of propositions. But this seems a bit too specific and tailored to the situation at hand. Instead, I suggest that, in order to spell out the argument for inconsistency, we should add the more general proposition (

) “observable quantities do not take infinite values” to the initial set of propositions. But this seems a bit too specific and tailored to the situation at hand. Instead, I suggest that, in order to spell out the argument for inconsistency, we should add the more general proposition (

![]() ) “the dynamical equations have solutions” to our original set.Footnote 12 Consider two points: (i) the solutions obtained to the dynamical equations of QED did not simply diverge for certain values of parameters, for high energies, say (a domain that will become important later on) – rather one obtained results that were universally infinite; (ii) there was no obvious way to use these infinities to make QED predict arbitrary values, for example, for the radiative corrections to the hydrogen spectrum. Instead, QED very specifically predicted infinite corrections. It thus seems fair to say that the dynamical equations of QED simply had no solutions at all, just as we would say that the following set of algebraic equations

) “the dynamical equations have solutions” to our original set.Footnote 12 Consider two points: (i) the solutions obtained to the dynamical equations of QED did not simply diverge for certain values of parameters, for high energies, say (a domain that will become important later on) – rather one obtained results that were universally infinite; (ii) there was no obvious way to use these infinities to make QED predict arbitrary values, for example, for the radiative corrections to the hydrogen spectrum. Instead, QED very specifically predicted infinite corrections. It thus seems fair to say that the dynamical equations of QED simply had no solutions at all, just as we would say that the following set of algebraic equations

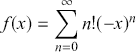

(2)

(2)

has no solutions and is thus inconsistent – even though

![]() is a solution of sorts. Adding a proposition such as (

is a solution of sorts. Adding a proposition such as (

![]() ) when evaluating the consistency of physical theories is not unprecedented. In his exploratory attempts at an axiomatization of mechanics, David Hilbert – arguably the authority on questions of mathematical consistency in the early twentieth century – implicitly used the existence of solutions to the dynamical equations as a consistency criterion (Majer, Reference Majer, Rédei and Stoelzner2001, p. 23). Proposition (

) when evaluating the consistency of physical theories is not unprecedented. In his exploratory attempts at an axiomatization of mechanics, David Hilbert – arguably the authority on questions of mathematical consistency in the early twentieth century – implicitly used the existence of solutions to the dynamical equations as a consistency criterion (Majer, Reference Majer, Rédei and Stoelzner2001, p. 23). Proposition (

![]() ) also seems in keeping with the practice of physics, which is far more concerned with solving equations than with logical deduction, ever since Leonhard Euler, in his reformulation of Newtonian mechanics, introduced “a new style of mathematical physics in which fundamental equations take the place of fundamental principles” (Darrigol, Reference Darrigol2005, p. 25).Footnote 13 And we will see later on that the existence of solutions remained the relevant criterion when Dyson began to investigate the consistency of renormalized QED.

) also seems in keeping with the practice of physics, which is far more concerned with solving equations than with logical deduction, ever since Leonhard Euler, in his reformulation of Newtonian mechanics, introduced “a new style of mathematical physics in which fundamental equations take the place of fundamental principles” (Darrigol, Reference Darrigol2005, p. 25).Footnote 13 And we will see later on that the existence of solutions remained the relevant criterion when Dyson began to investigate the consistency of renormalized QED.

But how robust was the claim that the equations of QED have no solutions? So much is made and has been made of the infinities that appeared in early QED that it seems important to point out that these infinities merely appeared in the higher orders of a specific approximation method – perturbation theory. Why did physicists in the 1930s equate the breakdown of an approximation method with the breakdown of the entire theory? A prominent explanation was given by Niels Bohr:

Their [Heisenberg and Pauli’s] formalism leads, in fact, to consequences inconsistent with

![]() the small coupling between atoms and electromagnetic radiation fields, on which rests the interpretation of the empirical evidence regarding spectra, based on the idea of stationary states. Under these circumstances, we are strongly reminded that the whole attack on atomic problems leaning on the correspondence argument is an essentially approximative procedure made possible only by the smallness of the ratio between the square of the elementary unit of electric charge and the product of the velocity of light and the quantum of action which allows us to a large extent to avoid the difficulties of relativistic quantum mechanics in considering the behavior of extra-nuclear electrons.

the small coupling between atoms and electromagnetic radiation fields, on which rests the interpretation of the empirical evidence regarding spectra, based on the idea of stationary states. Under these circumstances, we are strongly reminded that the whole attack on atomic problems leaning on the correspondence argument is an essentially approximative procedure made possible only by the smallness of the ratio between the square of the elementary unit of electric charge and the product of the velocity of light and the quantum of action which allows us to a large extent to avoid the difficulties of relativistic quantum mechanics in considering the behavior of extra-nuclear electrons.

![]() This is a non-dimensional constant fundamental for our whole picture of atomic phenomena, the theoretical derivation of which has been the object of much interesting speculation. Although we must expect that the determination of these constants will be an integral part of a general consistent theory in which the existence of the elementary electric particles and the existence of the quantum of action are both naturally incorporated, these problems would appear to be out of reach of the present formalism of quantum theory, in which the complete independence of these two fundamental aspects of atomicity is an essential assumption.

This is a non-dimensional constant fundamental for our whole picture of atomic phenomena, the theoretical derivation of which has been the object of much interesting speculation. Although we must expect that the determination of these constants will be an integral part of a general consistent theory in which the existence of the elementary electric particles and the existence of the quantum of action are both naturally incorporated, these problems would appear to be out of reach of the present formalism of quantum theory, in which the complete independence of these two fundamental aspects of atomicity is an essential assumption.

From Bohr’s characteristic verbosity we can extract the following argument: it is not at all surprising that QED breaks down at second order in perturbation theory. First-order perturbation theory, based on the “small coupling between atoms and electromagnetic radiation fields,” is not just some arbitrary approximation – it is an essential foundation that we rely on every time we calculate the energy of a stationary state without worrying about radiation.

To better understand this perspective, let us look back all the way to Bohr’s atomic model. It makes two claims about radiation: (a) electrons in a stationary state do not emit radiation, and (b) monochromatic radiation is emitted in discrete quantum jumps from one stationary state to another. In hindsight, these are not really fundamental postulates of quantum theory. Rather, they are statements about the validity of first-order perturbation theory. Claim (a) simply states that energy levels are not corrected until second order in perturbation theory, while (b) just states that transitions in first-order perturbation theory only involve one electromagnetic field operator, and thus only one photon with a single radiation frequency. This did not change in quantum mechanics, where Bohr’s second postulate was replaced by Fermi’s golden rule, which can be obtained directly from first-order perturbation theory.

Bohr’s view was that all of quantum mechanics was an “essentially approximative procedure,” a fact that was made manifest by the divergences appearing in second-order perturbative QED. This would only be resolved within a “general consistent theory,” in which one would be able to predict the value of the fine structure constant and thereby relate the elementary unit of charge

![]() to Planck’s constant.Footnote 14

to Planck’s constant.Footnote 14

In Bohr’s view, there was thus no point in looking for nonperturbative solutions. Quantum electrodynamics was built on quantum mechanics and quantum mechanics was built on perturbation theory; perturbation theory was thus hard-wired into the structure of QED. The breakdown of QED perturbation theory at second order thus implied the breakdown of QED tout court. In fact, it even implied the breakdown of quantum mechanics itself.

Alexei Kojevnikov has emphasized that attitudes toward theory change in the early 1930s were shaped (one might also say: distorted) by the radical developments of the preceding decades, and that physicists thus eagerly anticipated yet another conceptual revolution (Kojevnikov likens this to Trotsky’s notion of “permanent revolution”), rather than looking for more immediate solutions to the theoretical anomalies they encountered.Footnote 15 A similar point was made by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker in his reflections on his mentor Heisenberg:

In 1912, Bohr’s fundamental insight had been that explaining the stability of atoms would require not just a new atomic model, but new fundamental laws of physics. In 1925, Heisenberg had, at age 23, given these laws – under the name of quantum mechanics – their final shape, which they have kept to this day. On the level of philosophical reflection, this became for him the paradigmatic example of the idea that fundamental theoretical physics does not proceed in the steady accumulation of knowledge, but rather in a sequence of closed theories. Neither he nor Bohr then considered quantum mechanics to be the last fundamental theory; they expected imminent advances beyond this step. Heisenberg could never bear the thought that his youthful work should have been the last great inspiration of his life.

And Alexander Rueger (Reference Rueger1992, p. 315) remarks that “the strong emphasis on deficiencies pointed to the framework of expectations in which the authors worked.” It thus seems fair to say that many of the protagonists of early QFT were overly quick to accept the conclusion that QED was inconsistent, because they anticipated, from the start, that some “future final theory” (Heisenberg and Pauli, Reference Heisenberg and Pauli1929, p. 3) would replace it – and all of quantum mechanics along with it.

However, one did not need to hold such strong views on the future development of physics in order to equate the breakdown of perturbation theory with the inconsistency of QED. Based on a power series expansion in a very small parameter, perturbation theory was prima facie a very good approximation, as emphasized by the Swedish physicist Ivar Waller (Reference Waller1930, p. 675):

This calculation of course leaves open the possibility that the mistake is in the approximation method. But our method of solution seems to conform to the spirit of the theory, since the charge could in principle be taken to be arbitrarily small. More generally, a different method of solution hardly seems possible.

We can see here how quick physicists were to move from the in-practice unsolvability, as seen in the divergences arising in perturbation theory, to asserting in-principle unsolvability. But this was a crucial step. In-practice unsolvability would have been nothing new in physics. A famous example is hydrodynamics: proving that the Navier–Stokes equation has exact solutions ranks alongside the existence of Yang–Mills theory as one of the Clay Institute Millennium Problems. Yet, despite the longstanding difficulties involved in solving the dynamical equations of hydrodynamics, these were never viewed as implying the inconsistency of theoretical hydrodynamics. Although Leonhard Euler “deplored the difficulties of solving his [hydrodynamical] equations” (Darrigol, Reference Darrigol2005, p. 25), he stated his conviction that

If it is not permitted to us to penetrate to a complete knowledge concerning the motion of fluids, it is not to mechanics, or to the insufficiency of the known principles of motion, that we must attribute the cause. It is analysis itself which abandons us here since all the theory of the motion of fluids has just been reduced to the solution of analytic formulas.

This sentiment – that the unsolvability of the equations of hydrodynamics was a mathematical difficulty that did not affect the evaluation of hydrodynamics as a physical theory – was frequently echoed over the decades.Footnote 17 Indeed, outside the immediate context of hydrodynamics, one can rather observe the reverse argument: namely, that the physical cogency of an equation guarantees its solvability. This was notably emphasized by the French mathematician Jacques Hadamard:Footnote 18

It is remarkable

![]() that a sure guide is found in physical interpretation: an analytical problem always being correctly set, in our use of the phrase, [Footnote 19] when it is the translation of some mechanical or physical question.

that a sure guide is found in physical interpretation: an analytical problem always being correctly set, in our use of the phrase, [Footnote 19] when it is the translation of some mechanical or physical question.

Physicists in the 1930s did not have this sort of confidence when it came to QED. I argue that this was because, rather than having physical reasons to expect the existence of solutions, they had a ready physical interpretation for the unsolvability of QED – an interpretation also put forward by Bohr in his previously cited Faraday lecture:

The scope of the quantum mechanical symbolism is essentially confined, however, to problems where the intrinsic stability of the elementary electrical particles can be left out of consideration in a similar way as in the classical electron theory. In this connexion, it must not be forgotten that the existence of the electron even in classical theory imposes an essential limitation on the applicability of the mechanical and electromagnetic concepts.

![]() The difficulties inherent in any symbolism resting on the idealisation of the electron as a charged material point appear also most instructively in the recent attempt of Heisenberg and Pauli to build up a theory of electromagnetic fields on the lines of quantum mechanics.

The difficulties inherent in any symbolism resting on the idealisation of the electron as a charged material point appear also most instructively in the recent attempt of Heisenberg and Pauli to build up a theory of electromagnetic fields on the lines of quantum mechanics.

Bohr thus argued that the inconsistency observed in QED was a result of transgressing the theory’s domain of applicability – a domain of applicability it had largely inherited from classical electron theory, the result of an idealized description of charged matter as point particles. In classical electron theory, the domain of applicability was defined by the negligibility of radiation reaction, that is, the force experienced by an electron due to the field it generates itself.Footnote 20 As soon as radiation reaction had to be taken into account – e.g., for relativistic electrons or electrons in a synchrotron – one also needed to take into account the structure of the electron. However, no viable models of the structure of the electron were known: point particles led to infinitely large field energies close to the particle, while extended particles could not be kept stable, as there was no way of reconciling the necessary cohesive forces with special relativity.

In the classical theory, these difficulties could be avoided by simply neglecting the radiation reaction. All one had to do was eliminate the electron’s interaction with its self-field from the Lorentz force equation. The electron could then be treated as an idealized point charge. The price one had to pay was that one, more or less voluntarily, brought in a new form of inconsistency: energy is not conserved, because the field that appears in Maxwell’s equations (the total field) was not identical to the field that appears in the equations of motion of the electron (the external field, with the electron’s self-field neglected). This is the “inconsistency of classical electrodynamics” highlighted by Mathias Frisch (Reference Frisch2005).

The divergence difficulties of QED appeared to be analogous to the classical situation, because higher orders of perturbation theory could be physically interpreted as radiation reaction. The shift in energy levels and spectral lines due to radiative corrections clearly seemed to be the result of the electron’s interaction with its self-field. Unlike the classical case, however, that self-field was not to be identified with radiation actually emitted, but was instead purely “virtual.” This problematic aspect of the analogy did lead some physicists to view the inconsistency of QED as a genuine quantum phenomenon, arising from the presence of a continuous infinity of virtual states (Blum, Reference Blum2017, pp. 27–28, 41–42). But, by and large, the analogy between the divergences of QED and the classical problem of radiation reaction was accepted.

The analogy was extended by equating the local interactions of QED – that is, the evaluation of all fields in the dynamical equations at the same space-time point – with the assumption of point-like electrons in the classical theory.Footnote 21 The divergences resulting from the local interactions could be avoided by introducing a high-energy cutoff into QED. This was the analog of using an extended electron in the classical theory. But both of these solutions appeared impossible to reconcile with special relativity (Blum, Reference Blum2017, section 1.1).

What, then, was the quantum analog of the classical procedure of simply neglecting radiation reaction? In quantum theory one could achieve essentially the same thing by restricting oneself to leading-order perturbation theory. And with this restriction, QED was actually rather successful empirically, providing good quantitative descriptions of processes such as the emission and absorption of radiation (Dirac, Reference Dirac1927b), optical dispersion (Dirac, Reference Dirac1927a), or Compton scattering (Klein and Nishina, Reference Klein and Nishina1929). And if one simply ignored the infinities, the Dirac equation – unmodified by any QED corrections – gave excellent predictions for the fine structure of hydrogen (Dirac,Reference Dirac1928a,Reference Dirac1928b). For a time, some physicists endorsed such an approach to radiation phenomena, labeling it the “correspondence” approach because it preserved the close formal connection to classical theory that had been so essential in the construction of quantum mechanics. This idea was first proposed by Heisenberg (Reference Heisenberg1931), but, ultimately, it did not catch on.Footnote 22 In an interview with Thomas Kuhn and John Heilbron,Footnote 23 Léon Rosenfeld recalled the strong resistance this approach encountered:

I gave a paper on that at the congress in Rome [in 1931 (Rosenfeld, Reference Rosenfeld1932)], but it fell completely flat. People started saying, “Yes, but this is no theory,” or asking questions, “You have the Hamiltonian; why do you forbid us to handle the Hamiltonian according to the recipes?”

![]() I said then finally, ‘Yes, but what I intended to show is that by a simple correspondence prescription one can get all safe results

I said then finally, ‘Yes, but what I intended to show is that by a simple correspondence prescription one can get all safe results

![]() and the suggestion is that the only way one can work with this formalism is by not considering it a closed formal scheme.” Then Fermi, who was in the chair, just to close the discussion, said, “Yes, we have understood that, but that is not the usual conception one has of physical theories.” That was the general feeling.

and the suggestion is that the only way one can work with this formalism is by not considering it a closed formal scheme.” Then Fermi, who was in the chair, just to close the discussion, said, “Yes, we have understood that, but that is not the usual conception one has of physical theories.” That was the general feeling.

Just as in the classical theory, radiation reaction could only be removed by introducing a new kind of inconsistency. The original dynamical equations of QED (equation 1) were a “closed formal scheme”: the goal was to find (operators)

![]() and

and

![]() that, when inserted into the respective right-hand sides, yielded equations whose solutions were again the

that, when inserted into the respective right-hand sides, yielded equations whose solutions were again the

![]() and

and

![]() one started out with.Footnote 24 Aborting the approximation meant breaking this closed structure: the expressions one inserted no longer had to be exactly the expressions one got out. And physicists did not consider this option more attractive than the divergences of higher-order perturbation theory. As Rosenfeld went on to remark in the aforementioned interview with Kuhn and Heilbron, the correspondence approach was viewed as “the extreme position of defeat.”

one started out with.Footnote 24 Aborting the approximation meant breaking this closed structure: the expressions one inserted no longer had to be exactly the expressions one got out. And physicists did not consider this option more attractive than the divergences of higher-order perturbation theory. As Rosenfeld went on to remark in the aforementioned interview with Kuhn and Heilbron, the correspondence approach was viewed as “the extreme position of defeat.”

In the 1930s, the status of QED was thus fundamentally unclear. There were actual textbooks written on the subject in the 1930s and 1940s, but they included disclaimers such as the following:

At first it seemed that

![]() a consistent quantum theory of the electromagnetic field could not be found.

a consistent quantum theory of the electromagnetic field could not be found.

![]() It seems now that there is a certain limited field within which the present quantum electrodynamics is correct

It seems now that there is a certain limited field within which the present quantum electrodynamics is correct

![]() The present theory can be correctly applied to the interaction of light with elementary particles in the first approximation. The difficulties which occur, especially in the higher approximations to this interaction,

The present theory can be correctly applied to the interaction of light with elementary particles in the first approximation. The difficulties which occur, especially in the higher approximations to this interaction,

![]() show the limits within which the theory is valid.

show the limits within which the theory is valid.

![]() If the application of the theory is confined within these limits, it will be seen in this book that the theory gives – qualitatively and quantitatively – a full account of the experimental facts within a large field

If the application of the theory is confined within these limits, it will be seen in this book that the theory gives – qualitatively and quantitatively – a full account of the experimental facts within a large field

![]() Thus it seems that the theory is well enough developed, and the limits of application well enough marked, for a summary to be given.Footnote 25

Thus it seems that the theory is well enough developed, and the limits of application well enough marked, for a summary to be given.Footnote 25

As long as QED, aborted after the first approximation, gave perfect predictions within its very own domain (the emission and absorption of spectral radiation), the inconsistencies remained strangely inconsequential. This changed only when high-precision measurements indicated that the second approximation might be physically relevant after all.

2.2 Oppenheimer and Dyson

The first discrepancies started to appear in the late 1930s, but remained controversial. It was not until 1947 that Willis Lamb, building on his experience with WWII microwave radar technology, observed for the first time induced transitions from the

![]() to the

to the

![]() levels of hydrogen and found the transition frequency to be about 1 GHz smaller than expected. This “Lamb shift” soon came to be understood as the result of radiative QED corrections, implying that these corrections were neither infinite nor zero, but rather measurable and small. This led, almost immediately, to the development of renormalization methods, enabling the calculation of these corrections, and putting QED on track toward becoming the ultra-high precision theory it is now celebrated as.Footnote 26

levels of hydrogen and found the transition frequency to be about 1 GHz smaller than expected. This “Lamb shift” soon came to be understood as the result of radiative QED corrections, implying that these corrections were neither infinite nor zero, but rather measurable and small. This led, almost immediately, to the development of renormalization methods, enabling the calculation of these corrections, and putting QED on track toward becoming the ultra-high precision theory it is now celebrated as.Footnote 26

In the early years, these renormalization methods were very much in flux and far from standardized. Paul Matthews and Abdus Salam famously remarked that in renormalization theory, “[t]he difficulty [

![]() ] is to find a notation which is both concise and intelligible to at least two people of whom one may be the author” (Matthews and Salam, Reference Matthews and Salam1951, p. 314). Throughout this Element, I will homogenize conventions from the historical sources to keep the ideas we are interested in from being drowned in elaborations on notational differences and historical minutiae.Footnote 27 I have thus chosen to base my very brief sketch of renormalization theory, which primarily serves to introduce terms and conventions that will reappear throughout the Element, on a somewhat later review article by Matthews and Salam (Reference Matthews and Salam1954). This article already contains elements not found in Schwinger’s and Feynman’s original tool kits of the late 1940s. Nonetheless, I believe that it is close enough to the spirit of these early works, while simultaneously highlighting novel aspects that will become important only in later sections.

] is to find a notation which is both concise and intelligible to at least two people of whom one may be the author” (Matthews and Salam, Reference Matthews and Salam1951, p. 314). Throughout this Element, I will homogenize conventions from the historical sources to keep the ideas we are interested in from being drowned in elaborations on notational differences and historical minutiae.Footnote 27 I have thus chosen to base my very brief sketch of renormalization theory, which primarily serves to introduce terms and conventions that will reappear throughout the Element, on a somewhat later review article by Matthews and Salam (Reference Matthews and Salam1954). This article already contains elements not found in Schwinger’s and Feynman’s original tool kits of the late 1940s. Nonetheless, I believe that it is close enough to the spirit of these early works, while simultaneously highlighting novel aspects that will become important only in later sections.

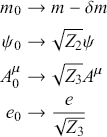

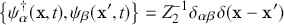

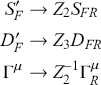

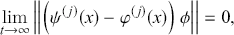

The first step in renormalization was to brand the fields and parameters that appear in the original (now: unrenormalized) QED field equations as unobservable “bare” fields and parameters, earning them a zero subscript as in

![]() for the bare mass.Footnote 28 One then performed a transformation from these unrenormalized quantities to the (observable) renormalized fields and parameters, which were denoted by the original symbols, without a subscript. The transformation to the renormalized field equations (and to the associated equal-time commutation relations) involved the following four substitutions:Footnote 29

for the bare mass.Footnote 28 One then performed a transformation from these unrenormalized quantities to the (observable) renormalized fields and parameters, which were denoted by the original symbols, without a subscript. The transformation to the renormalized field equations (and to the associated equal-time commutation relations) involved the following four substitutions:Footnote 29

Here,

![]() is the mass renormalization constant,

is the mass renormalization constant,

![]() the (electron) wave function renormalization constant, and

the (electron) wave function renormalization constant, and

![]() the charge (or photon wave function) renormalization constant. These constants can be chosen so as to cancel, term by term, the divergences that appear when perturbatively constructing scattering amplitudes from the field equations.Footnote 30 The renormalized fields and parameters were then entirely free of divergences and were identified with the particles and constants actually measured in experiment – the “physical” particles and constants, as they came to be called, in contradistinction to their “bare” counterparts. And that was it – pretty simple in theory, but rather complicated in practice, especially at higher orders of perturbation theory.

the charge (or photon wave function) renormalization constant. These constants can be chosen so as to cancel, term by term, the divergences that appear when perturbatively constructing scattering amplitudes from the field equations.Footnote 30 The renormalized fields and parameters were then entirely free of divergences and were identified with the particles and constants actually measured in experiment – the “physical” particles and constants, as they came to be called, in contradistinction to their “bare” counterparts. And that was it – pretty simple in theory, but rather complicated in practice, especially at higher orders of perturbation theory.

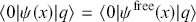

By the summer of 1948, it was clear that the results of the new precision measurements could be reproduced using renormalized QED. At the Eighth Solvay Conference in Brussels, in the fall of 1948 (several months before his debate with Dyson), Oppenheimer (Reference Oppenheimer1950) delivered a report on “Electron Theory,” in which he outlined the current status of QED.Footnote 31 He expressed his conviction that renormalization had not turned QED into a “completed consistent theory” (p. 272) – almost, but not quite. Renormalization only served to “isolate, recognize and postpone the consideration of those quantities

![]() for which the present theory gives infinite results” (p. 273). This “absence of complete closure” (p. 273) could no longer be blamed on the neglect of radiation reaction, which had, after all, become observable and calculable in the Lamb shift. Instead, Oppenheimer connected it with the neglect of the nuclear interactions, which had emerged as the new frontier of fundamental physics over the preceding two decades:

for which the present theory gives infinite results” (p. 273). This “absence of complete closure” (p. 273) could no longer be blamed on the neglect of radiation reaction, which had, after all, become observable and calculable in the Lamb shift. Instead, Oppenheimer connected it with the neglect of the nuclear interactions, which had emerged as the new frontier of fundamental physics over the preceding two decades:

[F]or mesons and nucleons generally, we are in a quite new world, where the special features of almost complete closure that characterizes electrodynamics is quite absent. That electrodynamics is

![]() not quite closed is indicated, not alone by the fact that for finite

not quite closed is indicated, not alone by the fact that for finite

![]() the present theory is not after all-consistent [sic], but equally by the existence of those small interactions with other forms of matter to which we must in the end look for a clue, both for consistency, and for the actual value of the electron’s charge (p. 281).Footnote 32

the present theory is not after all-consistent [sic], but equally by the existence of those small interactions with other forms of matter to which we must in the end look for a clue, both for consistency, and for the actual value of the electron’s charge (p. 281).Footnote 32

As opposed to radiation reaction, the nuclear interactions were not something that QED could in any way be considered responsible for. There was thus no point in looking to QED for further insights: “[T]he structure of the theory itself gives no indication of a field strength, a maximum frequency or minimal length, beyond which it can no longer consistently be supposed to apply” (p. 272). Oppenheimer therefore looked to the experimental study of the nuclear interactions for entirely novel theoretical insights, independent of the theoretical structure of QED.

He was aware that this was not the only option. The idea that QED might serve as an inspiration, a blueprint even, for a theory of the nuclear interactions had first been introduced by Hideki Yukawa in the mid-1930s and had never really gone away. In the discussion after his talk, Oppenheimer acknowledged that he himself had “at one time believed” that “the real importance” of renormalization “lay in the fact that one had an entirely new way of dealing with the Maxwell–Yukawa analogy” (p. 284). And while he now appeared to believe that “this analogy is rubbish,” he conceded that a more in-depth understanding of renormalized QED might be worth pursuing. Not in order to see “whether one can calculate to one part to

![]() th [sic], the Lamb shift,” but in order to explore whether a theory of the nuclear interactions could be modeled after QED, “even if one thinks the results would be negative” (p. 284).

th [sic], the Lamb shift,” but in order to explore whether a theory of the nuclear interactions could be modeled after QED, “even if one thinks the results would be negative” (p. 284).

When Oppenheimer returned from Europe to the IAS after the Solvay conference, Dyson had already begun his one-year fellowship at the institute. Dyson had just submitted a major paper on QED, in which he showed that the various covariant approaches to QED and renormalization, by Julian Schwinger, Richard Feynman, and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, were, in fact, equivalent (Dyson, Reference Dyson1949a). But, as we have seen, Oppenheimer was not particularly invested in the further development of renormalized QED. When approached by Dyson, he simply handed him a copy of the Solvay talk. In response, Dyson drafted a short memorandum outlining his views on QFT, which he sent (apparently by mail!) to Oppenheimer on October 18, 1948 and in which he asserted:Footnote 33

I do not see any reason for supposing the Feynman method to be less applicable to meson theory than to electrodynamics. In particular I find the argument about “open” and “closed” systems of fields irrelevant.

Dyson’s program stood in stark contrast to Oppenheimer’s – QED was supposed to act as a role model for future field theories of the nuclear interactions. And Dyson knew what the next step needed to be in order to show – and convince Oppenheimer – that this was indeed a viable approach:

What annoyed me in Oppenheimer’s initial lethargy was not that my finished work was unappreciated, but that he was making it difficult for me or anybody else to go ahead with it. What I want to do now is to get some large-scale calculations done to apply the theory to nuclear problems, and this is too big a job for me to tackle alone. So I had to begin by selling the theory to him. As soon as he understands and believes in it, he will certainly have a great deal of useful advice and experience to offer us in applying it. Also he may be able to help me decide what I should do next, though I am fairly determined already on a thoroughgoing attempt to prove the whole theory consistent.Footnote 34

Over the next couple of years, Dyson thus made it his mission to show that QED was a consistent theory and could serve as a a starting point for the study of the nucleus. Within the next couple of months, he famously proved that the S-Matrix in QED could be made finite to all orders of perturbation theory through renormalization (Dyson, Reference Dyson1949b). This achievement sufficiently softened Oppenheimer’s stance, allowing the two men to amicably agree to disagree at the January 1949 meeting that opened this book.

2.3 Investigating the Consistency of Renormalized QED

Dyson spent the rest of his year in Princeton enjoying the acclaim brought by his renormalizability proof and meeting his first wife, the Swiss mathematician Verena Haefeli, whom he married the following year. In the fall of 1949, he returned to England, where he spent the next two years at the University of Birmingham with Rudolf Peierls. During his first year at Birmingham, Dyson “was always dividing [his] time between five or six problems and never sat down and concentrated upon one thing long enough to finish it.”Footnote 35 It was not until December 1950, after another extended stay at the IAS, that he finally wrote a paper in which he laid out the steps still required to show that “quantum electrodynamics, in spite of its inherent divergences, constitutes a consistent and meaningful theory” (Dyson,Reference Dyson1951a, p. 428).

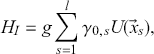

The two-step program Dyson laid out conforms with the suggested reading of “consistency” as “existence of solutions to the dynamical equations.” The first step was to extend his renormalizability proof beyond the S-Matrix. While some physicists had conjectured that relativistic quantum theory merely consisted in determining the S-Matrix,Footnote 36 it was generally viewed as a derived quantity. The immediate solutions to the dynamical equations of QED (eq. 1) were the field operators

![]() and

and

![]() . Dyson thus aimed to show that renormalization methods could also be applied to the (Heisenberg picture) field operators, thereby explicitly delivering solutions to the dynamical equations, solutions that were finite to all orders of perturbation theory. Dyson resolved the first point quickly and successfully, and we shall not discuss it much further. I will only mention that the methods he developed for this purpose turned out to be not as widely useful as his diagrammatic method for proving the renormalizability of the S-Matrix had been. This was a great disappointment to Dyson, who had hoped that investigating the consistency of QED would directly inform a QFT treatment of the nuclear interactions. As he later remarked in an interview with Sam Schweber: “This was not philosophically driven at all: it was intended as a practical tool” (Schweber, Reference Schweber1994, Section 9.16).

. Dyson thus aimed to show that renormalization methods could also be applied to the (Heisenberg picture) field operators, thereby explicitly delivering solutions to the dynamical equations, solutions that were finite to all orders of perturbation theory. Dyson resolved the first point quickly and successfully, and we shall not discuss it much further. I will only mention that the methods he developed for this purpose turned out to be not as widely useful as his diagrammatic method for proving the renormalizability of the S-Matrix had been. This was a great disappointment to Dyson, who had hoped that investigating the consistency of QED would directly inform a QFT treatment of the nuclear interactions. As he later remarked in an interview with Sam Schweber: “This was not philosophically driven at all: it was intended as a practical tool” (Schweber, Reference Schweber1994, Section 9.16).

The second step, which we will now discuss in more detail, was to lift the restriction to perturbation theory. After all, not only were all attempts at finding solutions to QED still based on perturbation theory, the entire renormalization procedure itself relied on removing infinities term by term from a perturbation series. In December 1950, Dyson sent a copy of his new paper to Wolfgang Pauli, whom he regarded as “the one member of the ‘old gang’ who takes the trouble to thoroughly understand the new methods.”Footnote 37 Pauli immediately seized on the restriction to perturbation theory as the central challenge for Dyson’s program:

I have no doubt that your good swimming belt will also be sufficient to drive you until the

![]() th approximation regarding the renormalization of the fields as it is announced by you. It is only after this step that things will get interesting.

th approximation regarding the renormalization of the fields as it is announced by you. It is only after this step that things will get interesting.

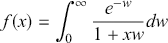

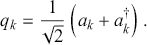

You stirred the curiosity of the reader by your remark “incidentally it will appear” (that is a really nice way to put it) “that our methods provide a basis for removing defect (i) (namely the expansion of everything in power [sic] of the coupling constant

![]() ) also from the analysis”.

) also from the analysis”.

Everything depends on whether you will get farer [sic] than Nr. II of the “series”. This would be a really new step which seems to me in any case beyond the reach of your present swimming belt.Footnote 38

This marked the beginning of a discussion on what it would actually mean to remove the restriction to perturbation theory. Dyson hoped to demonstrate the convergence of the perturbation series, which would then show that the approximative solutions one worked with corresponded to exact solutions of the dynamical equations of QED. Pauli, however, found this to be insufficient for two reasons: (i) “it would be practically useless in the case of a strong coupling (high values of the coupling constant)” (as might be expected for the nuclear interactions), and (ii) even a converging perturbation series provided little “physical enlightenment.”Footnote 39 Pauli would later speak of the “veil of the perturbation series.”

In his reply, Dyson reiterated the standpoint he had already defended with Oppenheimer two years earlier – proving the consistency of QED was not about gaining foundational insight, but about making immediate progress with quantum field theories of the nuclear interactions:

The test which I wish to be applied to my methods is “Do they enable us to decide definitely the correctness or incorrectness of meson theories by a quantitative comparison with experiment?” If they can do this, I shall be very well satisfied.

You are asking “Do the new methods give us any new theoretical insight into the foundations of physics?” This question I am content to answer in the negative.

Of course, I too would like to escape altogether from series expansions, if I could do it. But I believe the idea of renormalization is linked in a very complete way, perhaps inseparably, with the series expansion.Footnote 40

However, Pauli felt that a proof of consistency that was based on a perturbation expansion was not worth all that much. In his reply on February 18, 1951, he consequently objected:

That “the idea of renormalization is linked in a very complete way, perhaps inseparably with the (power) series expansion” is just the point which makes me feel rather critically to the present quantized field-theory (Even if this power series is mathematically convergent and its convergence can be proved and in spite of the practical successes of the new quantum electrodynamics)

![]() Even apart from practical questions of computation I have the definite impression that (also in electrodynamics) a final form of a fundamental law of nature should not be formulated in such a way that a power series development is essential to get the very logical (mathematical) meaning (definition) of this law.Footnote 41

Even apart from practical questions of computation I have the definite impression that (also in electrodynamics) a final form of a fundamental law of nature should not be formulated in such a way that a power series development is essential to get the very logical (mathematical) meaning (definition) of this law.Footnote 41

It is important to note that Pauli was not merely pitting his desire for physical insight against Dyson’s mathematical rigor. He associated Dyson’s perturbative approach with a specific mathematical tradition that he rejected, while simultaneously emphasizing, in the postscript to the letter cited earlier, that the two of them shared a much closer relationship with mathematics than most physicists. After all, Dyson had majored in mathematics as an undergraduate at Cambridge and had written several papers on number theory:

P.S. I hope to have once a chat with you on the general relation of mathematics and physics. In your present age I believed that my talent is lying in a very mathematical direction, although in a kind of “applied mathematics,” because my interest for the laws of nature was always very prominent. But then I fell into this spectroscopic “term-zoology” where my knowledge of the theory of complex analytic functions could not be used.

The development of the big mathematical edifice of quantum-mechanics was done by others, but anyhow I could apply my knowledge of Cayley and F. Klein with this “spinors” [

![]() ] By the way, F. Klein was always very much against the overemphasizing of the power series (Weierstrass).

] By the way, F. Klein was always very much against the overemphasizing of the power series (Weierstrass).

Mathematically, Pauli thus saw Dyson in the tradition of the nineteenth-century German mathematician Karl Weierstrass. In Felix Klein’s “Vorlesungen über die Entwicklung der Mathematik im 19. Jahrhundert” (Lectures on the Development of Mathematics in the 19th Century), Klein had portrayed Weierstrass as the proponent of the brute-force application of power series, remarking, for example, that Weierstrass had calculated series coefficients “up to the 20th order with all of the, downright uncanny, numerical factors” Reference Klein1926: [p. 280]. Klein contrasted Weierstrass with Riemann, for whom power series had been merely “an occasional resource for the elaboration of his thoughts,” while for Weierstrass they had been “the foundational principle” (Klein, Reference Klein1926, p. 254). Pauli repeated his characterization in a letter to his PhD student Armin Thellung:Footnote 42

Since you were last in Zurich, I had some quite interesting correspondence with him [Dyson]. It seems to me, however, after this exchange that after all he has not done what is needed, because he focused too strongly on convergence proofs for power series (which is why I often jokingly refer to him as the “Weierstrass” of theoretical physics). For him it remains the fact that

![]() renormalization is only definable through power series of the coupling constant