Introduction

Recent events such as floods, bushfires, and pandemics have demonstrated communities’ reliance on volunteers (Lai & Wang, Reference Lai and Wang2022; O’Halloran & Davies, Reference O’Halloran and Davies2020). From major crises to individual incidents, it is often volunteers who provide help on people’s worst days. For instance, there are 186,000 emergency responders and firefighters in Australia and 90% of them are volunteers (Productivity Commission, 2022). Furthermore, in 2018, Lifeline volunteers answered 739,481 phone calls from those who needed crisis support (Lifeline Australia, Reference Australia2019). Considering societies’ reliance on the response, recovery, and support services provided by volunteers, it is alarming to note that participation in formal volunteering (i.e. performing voluntary, unpaid work through an organisation) has been steadily declining. From 2014 to 2020, formal volunteering hours dropped by 34% in Australia (ABS, 2021). A similar declining trend has been observed in the USA (Fernandez & Alexander, Reference Fernandez and Alexander2017; Schreiner et al., Reference Schreiner, Trent and Prange2018) and Europe (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Taheri and Macintosh2016; Qvist et al., Reference Qvist, Henriksen and Fridberg2018). This decline suggests a significant fiscal cost for societies to replace unpaid labour. For organisations across various nations that rely on volunteers, it adds challenges as pressure mounts to cope with the lost workforce. As natural disasters increase in frequency and severity, it is paramount for volunteer-involving organisations to attract and sustain vital volunteer workforces.

The volunteering landscape is shifting dramatically. The COVID-19 pandemic, economic pressures, shifting employment ecosystems, and the prioritisation of lifestyle, family and work commitments are leading to an increased preference for short-term or informal volunteering (McLennan et al., Reference McLennan, Whittaker and Handmer2016). This poses significant challenges to organisations that rely on long-term volunteers. However, there are things that can be done to alleviate the pressure arising from declining numbers of regular, long-term volunteers. One way is to unpick volunteer motivation, which is fundamental for attracting and retaining volunteers. Another way is to ensure that volunteers do not stop volunteering due to issues that could have been prevented by volunteer-involving organisations, such as poor leadership (Lantz & Runefors, Reference Lantz and Runefors2020). When it comes to motivating and retaining members, there is a raft of research that highlights the essential role of leadership in the paid employment context (Cheong et al., Reference Cheong, Yammarino and Dionne2019; Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Hogan and Craig2008; Naile & Selesho, Reference Naile and Selesho2014; Tse et al., Reference Tse, Huang and Lam2013). For example, leaders can shape the work environment by fostering a culture of collaboration and trust and by providing guidance and opportunities for employee development. In turn, this can lead to positive organisational outcomes such as increased work engagement and retention (Mendes & Stander, Reference Mendes and Stander2011). However, less attention has been paid to the uniqueness of leading in ways that might motivate and sustain members who are volunteers. Leadership studies within mainstream management research mostly discuss or examine leadership on the underlying assumption that followers work to be paid, which, inarguably, does not apply to volunteers. Volunteers may not be paid, but there are immense economic implications to volunteering. The replacement costs associated with replacing volunteer labour with paid labour are immense. In Australia, volunteers contributed 489.5 million hours through organisations in 2020 (ABS, 2021), which, even at minimum wage and forging oncosts would equate to more than $9 billion. Similarly, the annual contribution is estimated to be 167 billion USD in the USA (Gui et al., Reference Gui, Tsai and Carroll2022).

The fact that volunteers are not paid, means the conventional lever of remuneration is absent from the toolboxes of leaders and managers of volunteers. This suggests that leaders of volunteers must exhibit especially nuanced leadership when managing volunteers and leading organisational success (Jaeger et al., Reference Jaeger, Kreutzer and Beyes2009). Having established our reliance on volunteers and the fact that volunteer numbers are dropping at an alarming rate, it is imperative that we take steps to better understand how leaders and managers can better attract, motivate, and retain volunteers.

Integrating the Volunteer Functions Inventory and Leadership Theories

This article distils leader behaviours that might be most effective in motivating people to engage in unpaid work. We do so by integrating extant leadership literature with the widely recognised framework, the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI, Chacón et al., Reference Chacón, Gutiérrez and Sauto2017; Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1998), which describes the internal drivers that motivate people to volunteer. Unlike reactive and spontaneous helping behaviour, volunteering is a proactive, planful and goal-directed helping behaviour (Wilson, Reference Wilson2012). Functional theorising, such as the VFI, posits that people volunteer to fulfil certain psychological functions (hereafter, volunteer motivations. Clary & Snyder, Reference Clary and Snyder1991). By using the VFI as a lens to examine leader behaviours, we can clearly illustrate how leaders can effectively leverage different volunteer motivations.

The VFI enumerates six functions that volunteering fills for people: values (volunteering to express personal values), understanding (volunteering to learn), career (volunteering to advance their career), social (volunteering to respond to social expectations), enhancement (volunteering to enhance self-esteem) and protective (volunteering to reduce negative feelings). It is suggested that an individual may volunteer to satisfy more than one of these functions and that multiple motivational functions may impel volunteer initiation, participation, and continuation (Stukas et al., Reference Stukas, Worth and Clary2009). For example, an individual might have initially become a volunteer to fulfil their career motivation, believing that volunteering would help them gain employment. Over time, the individual may become more actively engaged in the social side of volunteering, forming meaningful relationships with other volunteers, which would then serve to satisfy the individual’s social motivation. Regardless, understanding what leader behaviours might trigger which of the six volunteer motivations may offer some insights into the role of leadership in motivating and retaining volunteers.

There is a well-evidenced proliferation of leadership theories (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2020; Antonakis, Reference Antonakis2017; Dinh et al., Reference Dinh, Lord and Gardner2014; Meuser et al., Reference Meuser, Gardner and Dinh2016) and there is a preponderance of research focussed on understanding why people are willing to do unpaid work (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010; Ma & Konrath, Reference Ma and Konrath2018). But, until now, there has been no comprehensive look at how scholarly leadership knowledge may be applied to leading unpaid workers. Leading volunteers is an apparent paradoxical challenge. This is because the motivating effect of leadership becomes more important when there is no monetary incentive. However, the same fact that volunteers are not bound by the dependence on pay and may cease volunteering at any time can make leaders reticent to exert leadership authority (Jaeger et al., Reference Jaeger, Kreutzer and Beyes2009). Likewise, even when volunteers and paid employees are working towards the same objectives, they might perceive the workplace differently (Fallon & Rice, Reference Fallon and Rice2015). Other studies also underscored those managerial practices need to adapt to the uniqueness of volunteers in contrast to paid employees (Studer, Reference Studer2016; Vieira Da Cunha & Antunes, Reference Vieira Da Cunha and Antunes2022).

A Conceptual Map for Leading Volunteer Motivations

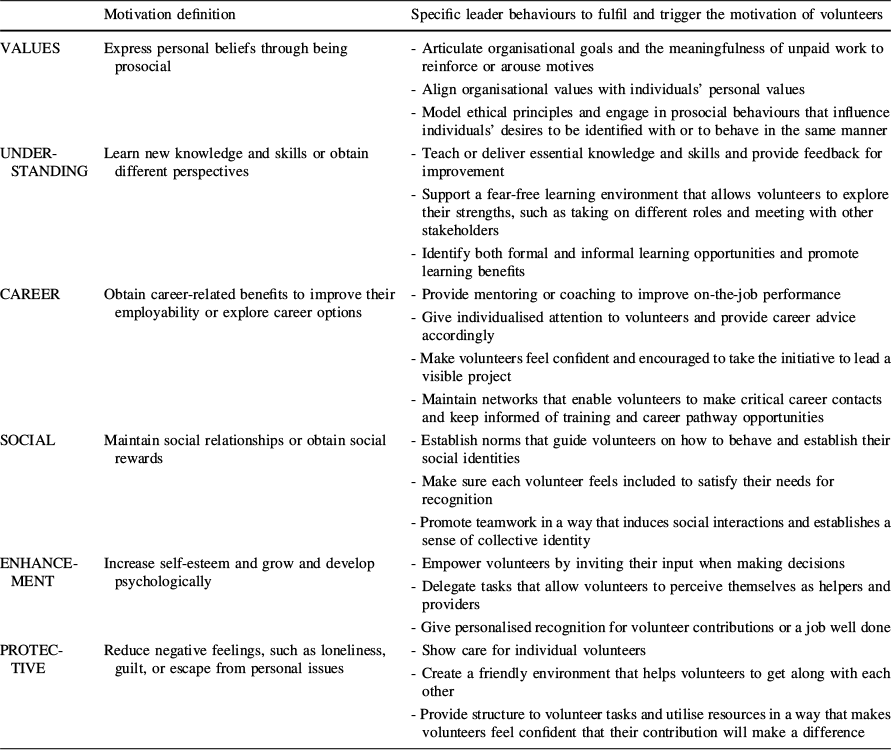

As a springboard, this article draws linkages between leader behaviours and specific volunteer motivations through a narrative review of leadership literature and volunteer literature. In each of the following six sections, we elucidate and define the distinct focus of the six VFI functions, we then identify and discuss relevant leadership theory to distil specific leader behaviours that could satisfy or trigger the corresponding motivation. The leadership theories we draw upon are considered foundational within mainstream leadership journals, which, to date, have paid little heed to the volunteering sector. The hope is that this initial integration sparks further synergies between leadership research and the unique context of volunteering organisations. The resulting framework, outlining all six motivations and corresponding leader behaviours is illustrated in Table 1. By completing this integration, this article serves as a conceptual map, providing scholars and practitioners with a novel and succinct way to navigate the plethora of leadership theories to identify discrete leader behaviours that might motivate volunteers and sustain the vital unpaid workforces we rely on. Given the increasing reliance on volunteers (Lai & Wang, Reference Lai and Wang2022) and the crucial role of good leadership in keeping volunteers volunteering (Veres et al., Reference Veres, Eva and Cavanagh2020; Vieira Da Cunha & Antunes, Reference Vieira Da Cunha and Antunes2022), we introduce a new perspective that may yield cascading contributions to both management and volunteer research. Implications for practice and avenues for future research are discussed.

Table 1 Summary of discussed motivations and suggested leader behaviours

Motivation definition |

Specific leader behaviours to fulfil and trigger the motivation of volunteers |

|

|---|---|---|

VALUES |

Express personal beliefs through being prosocial |

- Articulate organisational goals and the meaningfulness of unpaid work to reinforce or arouse motives |

- Align organisational values with individuals’ personal values |

||

- Model ethical principles and engage in prosocial behaviours that influence individuals’ desires to be identified with or to behave in the same manner |

||

UNDERSTANDING |

Learn new knowledge and skills or obtain different perspectives |

- Teach or deliver essential knowledge and skills and provide feedback for improvement |

- Support a fear-free learning environment that allows volunteers to explore their strengths, such as taking on different roles and meeting with other stakeholders |

||

- Identify both formal and informal learning opportunities and promote learning benefits |

||

CAREER |

Obtain career-related benefits to improve their employability or explore career options |

- Provide mentoring or coaching to improve on-the-job performance |

- Give individualised attention to volunteers and provide career advice accordingly |

||

- Make volunteers feel confident and encouraged to take the initiative to lead a visible project |

||

- Maintain networks that enable volunteers to make critical career contacts and keep informed of training and career pathway opportunities |

||

SOCIAL |

Maintain social relationships or obtain social rewards |

- Establish norms that guide volunteers on how to behave and establish their social identities |

- Make sure each volunteer feels included to satisfy their needs for recognition |

||

- Promote teamwork in a way that induces social interactions and establishes a sense of collective identity |

||

ENHANCEMENT |

Increase self-esteem and grow and develop psychologically |

- Empower volunteers by inviting their input when making decisions |

- Delegate tasks that allow volunteers to perceive themselves as helpers and providers |

||

- Give personalised recognition for volunteer contributions or a job well done |

||

PROTECTIVE |

Reduce negative feelings, such as loneliness, guilt, or escape from personal issues |

- Show care for individual volunteers |

- Create a friendly environment that helps volunteers to get along with each other |

||

- Provide structure to volunteer tasks and utilise resources in a way that makes volunteers feel confident that their contribution will make a difference |

Values–Expressing Oneself Through Being Prosocial

By definition, volunteer work is done for the sake of helping others (Wilson, Reference Wilson2012). The values motivation refers to people’s deep-held belief in helping others and supporting causes that are important to them (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1998). Although this motivation is often related to one’s altruistic attitude, it can also be interpreted as the opportunity for one to express themselves through being prosocial (i.e. actions that benefit others directly or indirectly through other causes, Butt et al., Reference Butt, Hou and Soomro2017). Unlike changing personality, triggering someone’s motivation to be prosocial may be achievable (Aknin et al., Reference Aknin, Van de Vondervoort and Hamlin2018). For example, the founder of the Student Volunteer Army, Sam Johnston, motivated 10,000 people to volunteer for those who were affected by the Christchurch earthquakes in 2011 (The New Zealand Herald, 2011). This could be because of his ability to arouse prosocial motivation, or because people tend to offer help when witnessing prosocial behaviours (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2019). This implies that the values motivation could be triggered by leadership. With regards to motivating others towards organisational missions that are service-oriented, transformational leadership and servant leadership are the most naturally aligned approaches (Schwarz et al., Reference Schwarz, Newman and Cooper2016; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Moynihan and Pandey2012).

Prior volunteer studies have suggested the more volunteers perceive the meaningfulness of their work, the more they are satisfied with their experience (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Bono and Snyder2013; Faletehan et al., Reference Faletehan, Van Burg and Thompson2021), which in turn, may improve their intention to remain (Chacón et al., Reference Chacón, Vecina and Dávila2007). The meaningfulness of volunteering often reflects the goals or missions of a volunteer-involving organisation. For instance, the meaningfulness of volunteering with fire and emergency services might be derived from the opportunity to protect the lives and assets of communities. Transformational leadership is known for articulating organisational goals to arouse the motives of others (Bass & Bass, Reference Bass and Bass2009). If a leader can articulate the differences volunteers can make through achieving inspiring organisational missions, it may arouse their motivation to volunteer and even attract others to join the organisation.

Unlike leaders of paid employees, leaders of volunteers may possess less legitimate power to leverage volunteers to work towards organisational goals. Servant leadership is praised for its approach of putting followers’ values ahead of organisational values and conceptualising organisational values to fit individual needs (Eva et al., Reference Eva, Robin and Sendjaya2019). If a leader helps volunteers see how the organisational values are aligned with their own, it may also motivate them to continue volunteering. Additionally, servant leadership is known for acting with ethical standards and creating a shared value through their care for others, empathy and humility, which is relevant to influencing others to act on the ethos of volunteering (Veres et al., Reference Veres, Eva and Cavanagh2020). This further highlights the potential link between leader behaviours derived from servant leadership and the values motivation.

Understanding–Learning Through Volunteering

The understanding motivation refers to people seeking to gain new knowledge through volunteering, such as learning new skills or obtaining different perspectives (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1998). Learning through volunteering may take place both formally and informally (Schugurensky & Mündel, Reference Schugurensky and Mündel2005). Formal learning refers to structured programs for members to acquire knowledge and skills (Garavan et al., Reference Garavan, Morley and Gunnigle2002). Though volunteer work is often assumed to be simple tasks, training is often provided to volunteers to help them become ‘helpful’ (Overgaard, Reference Overgaard2019). Newton et al. (Reference Newton, Becker and Bell2014) have found that volunteers who perceived more formal learning opportunities from their organisation showed higher levels of commitment and intention to stay. Informal learning refers to unplanned learning that results from experience (Garavan et al., Reference Garavan, Morley and Gunnigle2002). For example, volunteers may improve communication skills through more social interactions (Jones, Reference Jones2000) or gain a deeper understanding of social issues through volunteer service (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Myers and Higgins2009). When it comes to facilitating learning, and thus satisfying the understanding motivation, it is useful to draw in developmental leadership, a set of leader behaviours focussing on the development of organisational members (Zhang & Chen, Reference Zhang and Chen2013).

Developmental leadership is an emerging concept derived from a specific dimension of existing leadership theories, such as transformational leadership and path-goal theory, where leaders engage in behaviours that aim to improve members’ work-related knowledge (Delle & Searle, Reference Delle and Searle2022). This is because, in order to maintain organisational competitiveness, leaders are often expected to develop employees’ capabilities to innovate, adopt changes and improve performance (Gilley et al., Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011; LeBrasseur et al., Reference LeBrasseur, Whissell and Ojha2002). Extant research has suggested that this type of leadership can have a positive effect on employees’ learning and development through direct structural change and indirect influences (Ye et al., Reference Ye, Wang and Li2019; Yukl, Reference Yukl2009). For instance, leaders can help to increase the perception of psychological safety that allows employees to try new things or learn from errors. The developmental leadership model proposed by Gilley et al. (Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011) and Wallo’s (Reference Wallo2008) findings on leader behaviours that facilitate learning may help to illustrate three roles, or sets of behaviours, that a leader may engage in to fulfil or trigger a volunteer’s understanding motivation.

Firstly, leaders can act as educators, who teach how things should be done, clarify expectations (Wallo, Reference Wallo2008), and provide feedback for improvement (Gilley et al., Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011; Lopez-Cabrales et al., Reference Lopez-Cabrales, Bornay-Barrachina and Diaz-Fernandez2017). These behaviours may be relevant for volunteer tasks that require specific competencies or are potentially difficult, such as caring for elders with dementia, which as described in Tingvold and Olsvold’s (Reference Tingvold and Olsvold2018) study, was often far from one’s assumption that volunteer work would just be rewarding and simple. Secondly, leaders can act as supporters, who maintain a good learning environment (Gilley et al., Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011; Wallo, Reference Wallo2008) and create learning opportunities (Gilley et al., Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011). For example, fostering a fear-free environment where volunteers would feel encouraged to learn and try new things; allowing volunteers to explore their strengths by alternating tasks, or introducing volunteers to organisational stakeholders to improve their interpersonal skills (Schugurensky & Mündel, Reference Schugurensky and Mündel2005). Thirdly, leaders can act as motivators, who promote learning and seize opportunities for volunteer development (Gilley et al., Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011). For example, leaders may emphasise the informal learning benefits that volunteers may get from working alongside others (Eraut, Reference Eraut2004).

Career–Increasing Employability Through Volunteering

The career function motivates people to volunteer as a way to help with their career paths, such as adding experiences to their resume, exploring career options or networking (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1998). Volunteer studies have shown that career motivation was more often observed in students, people who are unemployed, and people who are preparing to compete in the job (Gage & Thapa, Reference Gage and Thapa2012). People with this motivation seek career-related benefits from volunteering to increase their employability (Van Der Sluis & Poell, Reference Van Der Sluis and Poell2003). With regards to how leaders may help volunteers to perceive their employability can be improved through volunteering, developmental leadership suggested in the previous understanding motivation is again relevant.

In the same vein, as developmental leadership helps organisational members to build their capabilities, it also improves their job-related skills. In the study of Rafferty and Griffin (Reference Rafferty and Griffin2006), they found that developmental leadership is positively related to employees’ perceived career certainty, satisfaction and commitment, in which career certainty is a concept closely related to employability. The developmental leader behaviours examined by Rafferty and Griffin (Reference Rafferty and Griffin2006) are close to mentoring and coaching, whereby leaders teach job-related skills and provide feedback to improve job performance. In the case of volunteering, if the tasks require skills or experiences that align with volunteers’ desired careers, leaders can incorporate opportunities to practice said skills or experiences into volunteering activities, therefore supporting the volunteers’ career motivation.

Developmental leadership, as expanded by other studies (e.g. Gilley et al., Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011; Larsson, Reference Larsson2006; Yukl, Reference Yukl2012), also includes providing challenging assignments and career advice. In volunteering, examples of challenging assignments can be for volunteers to organise a fundraising event or lead a project with the support of organisations, which can add achievements to their resumes. But this may first require leaders to identify volunteers’ strengths and weaknesses and give encouragement to help them feel comfortable taking up challenging roles (Larsson, Reference Larsson2006; Palanski & Vogelgesang, Reference Palanski and Vogelgesang2011). Moreover, as suggested by Gilley et al. (Reference Gilley, Shelton and Gilley2011), developmental leaders also maintain favourable external networks to help organisational members make critical contacts. This may be particularly relevant for those who are motivated to volunteer because they see volunteering as a pathway to employment. For example, leaders of volunteers can help to identify suitable training opportunities or introduce key contacts when volunteers are entering the job market. Additionally, leaders may seek to cooperate with job centres or government-supported agencies to promote volunteering as a pathway to employment (Rochester et al., Reference Rochester, Donahue and Grotz2009).

Social–Gaining Social Rewards Through Volunteering

The social motivation encompasses an individual’s concern for their relationships with others and the expectations from their social circles (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1992, Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1998). In other words, one may volunteer to strengthen their social relationships (e.g. volunteering to spend more time with friends and family) or as a result of the normative influence (e.g. volunteering to make others like them and think highly of them). Studies have shown that these social factors can make volunteers become more engaged in volunteer activities (Mcdougle et al., Reference Mcdougle, Greenspan and Handy2011) and stay within the same volunteer group longer (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Kaplan and Grese2001). In the study of Kragt et al. (Reference Kragt, Dunlop and Gagne2018) on emergency services volunteers, camaraderie or belonging to a team is one of the most common reasons for becoming a volunteer. This suggests that volunteering provides social-related rewards, such as obtaining a social identity, feeling a sense of belonging and receiving peer recognition (Jessen, Reference Jessen2010). Therefore, we suggest the aspect of team-based leadership research that focuses on team member cohesion can be relevant.

Team leadership studies emphasise the main task of a team leader is to maintain or improve the outcome of teamwork, rather than the sum of individual work outcomes (Zaccaro et al., Reference Zaccaro, Heinen and Shuffler2008). A team leader can do so through various functions, one of which is to maintain team cohesion (Hill, Reference Hill and Northouse2019). Improved team cohesion creates more opportunities for members to receive social rewards (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Hu and Hempel2021), and it may grow their willingness to engage in helping behaviours (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Shih and Chiang2015), which directly supports the fulfilment of the social motivation in volunteering. A team leader may improve team cohesion by establishing team norms, or clear guidelines and standards for behaviours, such as being fair and consistent (Hill, Reference Hill and Northouse2019; Zaccaro et al., Reference Zaccaro, Rittman and Marks2001). When applied to volunteer settings, these team norms can help volunteers from diverse backgrounds with different perspectives understand how to behave agreeably within their group. According to Hill’s (Reference Hill and Northouse2019) team leadership model, it is also suggested that leaders should support individual members who have difficulty blending in with others. This is in line with fulfilling the social motivation by removing the barriers for volunteers to strengthen their social relationships.

Leaders can also promote teamwork to create opportunities for volunteers to establish their social identity and receive peer recognition, thereby satisfying the social motivation. This is because teamwork naturally creates more interactions between members, and a common goal can allow group members to perceive a sense of collective identity and obligation (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Hu and Hempel2021; Salas et al., Reference Salas, Burke and Cannon-Bowers2000). This is in line with the study of Haski-Leventhal and Cnaan (Reference Haski-Leventhal and Cnaan2009) on the role of the group process in promoting volunteerism, in which they suggested that collective identity allows volunteers to feel a sense of belonging and receive peer recognition (Haski-Leventhal & Cnaan, Reference Haski-Leventhal and Cnaan2009).

Protective–Dealing with Negative Feelings Through Volunteering

The protective motivation refers to the need for one to keep themselves from negative feelings, and volunteering work can serve as a remedy for personal issues, loneliness, guilt, or feeling incompetent (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1998). Studies have shown that volunteering helped widows feel less lonely (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Kail and Matz-Costa2017) and improved the well-being of elders (Chi et al., Reference Chi, Almeida and Charles2021). Studies on conservation stewardship suggested that volunteering helped volunteers to relieve their sense of guilt from the problems that humans have caused to the environment (Asah & Blahna, Reference Asah and Blahna2012). With regards to helping volunteers address their adverse feeling through volunteering, we suggest both supportive leadership and task-oriented leadership can be helpful.

Leaders may set the tone and co-create a desirable environment with others through what they say and do (Kaiser et al., Reference Kaiser, Hogan and Craig2008). Supportive leadership describes when leaders attend to the well-being and needs of an individual member, make the work environment pleasant, and build quality relationships (Yukl, Reference Yukl2012). Khalid et al. (Reference Khalid, Zafar and Zafar2012) have found that supportive leadership helps to reduce stress, anxiety or other negative attributes of employees. This suggests that supportive leadership may be suitable for enhancing the protective mechanism that one may be seeking from volunteering. An environment where volunteers can feel welcomed, supported, and safe to share their concerns may help those who are coping with loneliness or negative feelings. In the volunteer study of Waikayi et al. (Reference Waikayi, Fearon and Morris2012), they also suggested that leaders’ supporting behaviours may contribute to volunteer retention.

Task-oriented leadership refers to when leaders’ main focus is on achieving organisational goals, in which leaders engage in behaviours such as providing structure, facilitating training to improve members’ competencies and aligning members’ roles with their skills (Yukl et al., Reference Yukl, Gordon and Taber2002). The relevance between task-oriented leadership and the protective motivation is put forward according to the findings of Zievinger and Swint (Reference Zievinger and Swint2018), which suggested the possibility that the more volunteers receive directions and training, the more they could distract themselves from their personal issues. This implies that task-oriented leader behaviours are likely to enhance the protective mechanism of volunteering. Additionally, task-oriented leadership is also shown to have a positive effect on members’ perceived group efficacy and work outcome (Tabernero et al., Reference Tabernero, Chambel and Curral2009). In the case where volunteers care deeply about helping the disadvantaged or environmental conservation, task-oriented behaviours may help them feel confident that the organisation is effectively utilising their contribution.

Enhancement–Feeling of Increased Self-esteem and Empowerment

The enhancement motivation pertains to one’s desire for psychological growth (Clary & Snyder, Reference Clary and Snyder1999), whereby volunteering can contribute to self-development and self-esteem and fulfil the desire to feel important and needed (Clary et al., Reference Clary, Snyder and Ridge1998). Contrary to people with the protective motivation, who seek to feel ‘better from the negatives’, those with the enhancement motivation strive to feel ‘good about themselves’. Studies have found that the enhancement motivation is positively related to volunteer satisfaction (Dwyer et al., Reference Dwyer, Bono and Snyder2013) and intention to keep volunteering (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Becker and Bell2014), which implies that triggering the enhancement motivation could keep volunteers volunteering. Several outcomes derived from volunteering can fulfil one’s enhancement motivation, such as feelings of autonomy, a sense of achievement, finding value in voluntary service, being asked to help, and being recognised for their contribution (Vecina et al., Reference Vecina, Chacón and Marzana2013). Many of the above are closely related to the concept of empowerment, which refers to “the perception by members that they have the opportunity to help determine work roles, accomplish meaningful work, and influence important decisions” (Yukl & Becker, Reference Yukl and Becker2006: 210). Amongst the various leadership styles that previous leadership research has established, participative leadership is the style that is most often thought to be a major source of empowerment (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Iun and Liu2010).

Participative leadership is seen when leaders invite members’ suggestions before making decisions and share responsibilities (Arnold et al., Reference Arnold, Arad and Rhoades2000). These behaviours can thus make the members feel empowered through feeling a sense of control and competency, especially when the collective decision has led to a positive result (Yukl & Becker, Reference Yukl and Becker2006). It is also suggested that participative leader behaviours can help provide clarity to members about the goals to be achieved when the tasks are unstructured (House, Reference House1996). In the case of volunteering, the empowering effect of participative leader behaviours can be illustrated by the study of Gilbert et al. (Reference Gilbert, Chauvenet and Sheppard2020), in which a community garden leader gave young volunteers the responsibility to take the produce to other elderlies, thereby allowing the young volunteers to perceive themselves as helpers and providers. As a result, it can bring a positive effect on volunteers’ self-esteem and sense of purpose.

Leaders may also fulfil the enhancement motivation of volunteers by simply recognising their contribution or a job well done. Recognition allows one to feel appreciated, honoured and, therefore, esteemed (Bailey, Reference Bailey2003). The fact that leaders are willing to spend time to give personalised recognition may also add value to the receivers (Luthans, Reference Luthans2000). In Esmond’s (Reference Esmond2009) study on emergency services volunteers, she suggested that recognition often serves as a powerful underlying force that keeps volunteers going when they feel like quitting.

Discussion

By examining the six main volunteer motivations, we have distilled precise leader behaviours from extant literature that might be effective in triggering the corresponding motivation. This integration of the functional approach to volunteer motivation and leadership theories can be useful for managers of volunteers to better understand why volunteers start and keep volunteering, and also, help them to discern which leader behaviour are most likely to result in more sustainable volunteer workforces. This is especially important for organisations that rely on long-term volunteers to deliver essential services. We suggest, as presented in Table 1, that there are certain behaviours derived from the decades of leadership research that can be adopted to help volunteers to express personal values, learn, advance careers, obtain social rewards, enhance self-esteem and deal with negative feelings.

People can be attracted to volunteer and become more committed to volunteer service when there is a match between the benefits provided by volunteering and their needs and motives (Stukas et al., Reference Stukas, Worth and Clary2009). Without the monetary incentives and the fact that volunteers can come and go at will, attention should be on how organisations can fulfil the existing needs underlying the motivation to work for no pay. Our interest has been in the role of leadership in this process. Attacking this question from a starting point of one existing leadership theory is futile. For one, participants in an unpaid workforce are varied in the expectations they have for volunteering (Neely et al., Reference Neely, Lengnick-Hall and Evans2021) and therefore require different leadership models to satisfy them. Through our narrative review on how specific leader behaviours can effectively address various volunteer motivations, we respond to the calls for more leadership scholars’ attention to volunteering (Vieira Da Cunha & Antunes, Reference Vieira Da Cunha and Antunes2022) and the calls for more volunteer scholars’ attention to leadership (Posner, Reference Posner2015). Given the increasing reliance on volunteers against the backdrop of declining volunteer numbers, this article can benefit volunteer practitioners, providing them with a succinct way to navigate the plethora of leadership theories to identify discrete leader behaviours that might be effective for motivating volunteers.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

As the motivation for this article stems from the limited work that comprehensively examined the linkage between volunteering and leadership, providing emerging, novel insights from recent leadership research was not our intention. Although this is a significant limitation, we believe that the connections we have proposed between each functional motivation and leadership theory can enrich the conversation surrounding volunteer leadership. Future work is required to examine if the listed behaviours are indeed preferred by volunteers with the corresponding motivation or if they can successfully fulfil or trigger the related motivation. Moreover, as we positioned this article as a conceptual exploration of the topic, the propositions we made should not be regarded as definitive conclusions. Rather, we hope that they guide future conceptual and empirical investigations into the relationships between leader behaviour and volunteers’ motivations to continue volunteering.

We also recognise that our chosen approach to volunteer motivation and our interpretations of each motivation affect the choices we made on which leadership literature to draw from. Likewise, contextual factors such as followers’ characteristics, organisational capabilities and culture, and contingencies should also be considered in examining the links between leader behaviours and outcomes (Behrendt et al., Reference Behrendt, Matz and Göritz2017). The interplay between leadership, motivation and contextual factors is deeply complex. We urge future research to consider the multifaceted nature of volunteer leadership, the diversities of volunteering contexts, and the pressing issue of volunteer retention.

Under-researched Areas and Recommendations for Volunteer Recruitment

The six VFI motivations also represent the psychological functions that anyone may seek to fulfil regardless of the context (Lavelle, 2010). This has led to our discovery of areas where leadership research has paid less attention to. For example, how leaders could adequately enhance the protective mechanism of work activities for those who wish to escape from their personal negative feelings; how leaders may increase the opportunities for employees to receive social rewards. Additionally, we suggest that in order to tackle the problem of declining volunteering, it is equally important for leaders to effectively recruit volunteers. Though leadership has been associated with charisma that attracts people to follow (Corcoran & Wellman, Reference Corcoran and Wellman2016), there was less attention on how leaders may attract new followers from outside the organisation (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Engemann and Williams2017). Future research may consider how leaders can attract outsiders to become volunteers. Some recommendations derived from the volunteering literature that are relevant to each of the six motivations are illustrated as follows.

Based on our discussion on the values motivation, a leader can communicate organisational goals clearly in a way that helps volunteers internalise the goals and become advocators of the organisation themselves, which may help to attract others to join the organisation (Linda & Welty Peachey, Reference Linda and Welty Peachey2012). For the understanding and career motivations, a leader should explicitly promote the informal learning benefits and the benefit of applying soft skills gained from volunteering to formal workplaces (Schugurensky & Mündel, Reference Schugurensky and Mündel2005). Based on the concept of social influence, a leader can adopt a word-of-mouth recruitment strategy (Freeman, Reference Freeman1997; Neumann, Reference Neumann2010) as well as target specific demographic groups or promote the organisational culture, since people tend to be attracted to others who share similar social identities (Machin, Reference Machin2007) or similar values (Hudon, Reference Hudon2008; Wilson, Reference Wilson2001). Drawing from the concept of protective motivation, a leader can consider message framing when recruiting. For example, they can emphasise to potential volunteers the negative consequences if no one is willing to help, while also highlighting their ability to help those in need (Lindenmeier, Reference Lindenmeier2008). How leaders can attract new volunteers while setting the right expectations to sustain their participation is an interesting phenomenon that can be further explored (Dunlop et al., Reference Dunlop, Holtrop and Kragt2022), where instead of the hiree being assessed by the organisation, the organisation is assessed by them.

Conclusion

Volunteering is of huge economic and practical value to society. The decline in people’s propensities to volunteer through organisations could weaken our ability to handle the impact of increasing natural disasters and societal demands. Our goal in this article is to identify links between volunteer motivations and leadership theories by using a well-established volunteer motivation model to pinpoint discrete leader behaviours that might trigger various motivations to volunteer. Our aim is to contribute to scholars and practitioners in understanding how leadership may be applied to volunteering. It appears plausible that there are connections between discrete leader behaviours, rather than holistic leadership styles, that are capable of triggering and fulfilling volunteer motivations. Future research can be designed to map this connectivity and to identify those behaviours with precision where they exist. Such knowledge can assist organisations and leaders to use or hone their behaviours as the trigger to attract more volunteers and keep them volunteering longer. We anticipate that the cumulative knowledge of leadership scholarship is well-positioned to contribute to building a sustainable pipeline of volunteers. Going forward, because we expect increasing calls for volunteers to support essential services where the government is short of supply, we hope this work will introduce new perspectives and inspire an array of much needed volunteer leadership research.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Allan Branch for providing critical comments as a volunteer practitioner on the first full draft of the manuscript and for his mentorship of Amber Tsai.

Author Contributions

ACYT and TN contributed to the study conception. ACYT conducted the literature review, conceptualised and wrote the first full draft of the manuscript. TN and GL provided commentary and revision to the previous versions of the manuscript. TN, GL and S-HC supervised the study as part of Amber Tsai’s dissertation and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.