Imagine that 2 countries, one larger and the other one smaller, are involved in a tragic event (e.g., a war or a natural disaster) where people in both countries die. Given that the population in one country is smaller than the other, is the loss of lives more tragic in that country? And if so, what is the correct proportion for sizing up these different tragedies? If, say, the population of one country is 10 times larger than the other, how many lost lives in the large country would be equivalent in tragedy to the loss of 1 life in the smaller country?

The present research investigates proportional thinking in the valuation of lives. Previous research has shown how people are sensitive to proportions in valuing victims and tragedies. Specifically, people’s judgments are sensitive to the relative size of the number of victims proportional to the population. For instance, people consider the loss of 10 lives more tragic (and they are more motivated to prevent or remedy that tragedy) when that number represents a larger proportion of the population (e.g., 10 out of 10 people dying) than when it represents a smaller proportion (e.g., 10 out of 100; Bartels, Reference Bartels2006; Erlandsson et al., Reference Erlandsson, Björklund and Bäckström2014; Fetherstonhaugh et al., Reference Fetherstonhaugh, Slovic, Johnson and Friedrich1997; Friedrich et al., Reference Friedrich, Barnes, Chapin, Dawson, Garst and Kerr1999; Jenni and Loewenstein, Reference Jenni and Loewenstein1997; Mata, Reference Mata2016). This is known as proportion dominance (Finucane et al., Reference Finucane, Peters, Slovic, Schneider and Shanteau2003; a multicausal phenomenon determined by mechanisms such as perceived impact and intuitive thinking; Erlandsson et al., Reference Erlandsson, Björklund and Bäckström2015; Mata, Reference Mata2016).

In this work, rather than testing whether people consider the proportion of 1 group of victims in relation to the population size, we consider whether people judge the loss of lives in 2 groups as a function of their different sizes. For instance, do people consider that the loss of 10 lives in a smaller group is more tragic than the loss of the same number of lives in a larger group (because 10 is a larger proportion of the smaller group)? And how far do people take this form of proportional thinking: Do they consider that the loss of 10 lives in a smaller group is as tragic as the loss of 100 lives in a group that is 10 times larger?

Our research hopes to make 3 contributions: (1) To document a novel form of proportional thinking, regarding whether a certain number of lives in a certain population is more or less valuable (or tragic, when lost) when compared with the same number of lives in another population. Moreover, we test whether this form of proportional thinking is influenced by 2 key factors: (2) Whether judgments are made with regard to individuals (e.g., whether the loss of 1 life in a smaller country is equivalent to the loss of 10 lives in a country that is 10 times as populous) or collectives (e.g., whether the loss of 1,000 lives in a smaller country is equivalent to the loss of 10,000 lives in a country with a population that is 10 times larger); and (3) Whether proportional thinking leads to favorable conclusions (i.e., when the loss of 1 life in a population that one cares about is deemed more valuable than the loss of 1 life in a larger population) or rather unfavorable conclusions (i.e., when proportional thinking renders less valuable the lives of a population that one cares about, when compared to a similar number of victims in a smaller population).

1. Individuals versus collectives

Research in various domains shows that people tend to value individuals more highly than collectives. Individual targets elicit greater affect than do collective ones: People feel more empathy for, and are more moved by, an individual than a group (Sherman et al., Reference Sherman, Beike, Ryalls, Chaiken and Trope1999; Vaz and Mata, Reference Vaz and Mata2025; Vaz et al., Reference Vaz, Mata and Critcherin press; Walker and Gilovich, Reference Walker and Gilovich2021). The same goes specifically for the valuation of lives: Research on the identified victim effect Footnote 1 (Schelling, Reference Schelling and Chase1968) shows that people respond more strongly (both emotionally and in their desire to help) to the suffering of single individuals than to collective/statistical victims (Cameron and Payne, Reference Cameron and Payne2011; Small et al., Reference Small, Loewenstein and Slovic2007, Reference Smith, Faro and Burson2013; Västfjäll et al., Reference Västfjäll, Slovic, Mayorga and Peters2014).

Thus, whether people engage in proportional thinking of the sort described above might depend on whether it refers to individuals or collectives. Specifically, we predict that when participants consider collectives, they are more likely to engage in proportional thinking than when they consider the lives of individuals. For instance, people should be more likely to agree that 1,000 lost lives from a given country are equivalent to 10 times that many lives (10,000) from a country 10 times larger, than they are to agree that 1 life from the smaller country is equivalent to 10 lives of the larger country.

2. Motivated statistical reasoning

In a way, the 2 literatures reviewed above come across as somewhat contradictory: Research on proportion dominance suggests that people are sensitive to the proportional size of the group of victims, whereas research on the identified victim effect (or, relatedly, scope insensitivity and compassion collapse) shows the lack of proportionality in people’s responses to the suffering of one versus many. Rather than seeing these phenomena as irreconcilable, we regard them as manifesting the remarkable flexibility of the human mind, such that people can engage in strikingly different modes of thinking about similar information.

One potential driver of which mode of thinking operates at a given moment is motivated reasoning: What conclusions people desire to support (Kunda, Reference Kunda1990). Indeed, research shows that people can think in highly flexible ways about numbers and statistics depending on what serves their favored conclusions (e.g., Braga et al., Reference Braga, Mata, Ferreira and Sherman2017; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Gilovich and Regan2002; Ditto et al., Reference Ditto, Scepansky, Munro, Apanovitch and Lockhart1998). Of particular relevance to the present research, previous studies have shown that motivated reasoning can serve an identity-protective function (Kahan et al., Reference Kahan, Peters, Dawson and Slovic2017). In particular, people have been shown to engage in more or less proportional thinking depending on what enables them to defend conclusions that are advantageous to them and their groups (Mata et al., Reference Mata, Ferreira and Sherman2013; Mata et al., Reference Mata, Garcia-Marques, Ferreira and Mendonça2015a,b).

We predict that the same holds for the valuation of lives: People should be more likely to engage in proportional thinking in valuing lives when it results in judgments that are favorable to their ingroup than when proportions devalue the lives of their ingroup members. Using the same example/numbers as before, we predict that participants are more likely to agree that a certain number of lost lives from their countrymen is equivalent to 10 times those many lives from another country that is 10 times larger, than they are to agree that 1 life from a smaller country is equivalent to 10 lives of their countrymen.

In Study 2, we will prompt motivated proportional thinking by manipulating group membership. Typically, people value the members of an ingroup more than those of an outgroup (e.g., Balliet et al., Reference Balliet, Wu and De Dreu2014; Duclos and Barasch, Reference Duclos and Barasch2014) and favor charity work that benefits their national ingroups (Baron and Miller, Reference Baron and Miller2000; Baron et al., Reference Baron, Ritov and Greene2013; Erlandsson, Reference Erlandsson2021; Erlandsson et al., Reference Erlandsson, Lindkvist, Lundqvist, Andersson, Dickert, Slovic and Västfjäll2020; Fiedler et al., Reference Fiedler, Hellmann, Dorrough and Glöckner2018; James and Zagefka, Reference James and Zagefka2017; Levine and Thompson, Reference Levine and Thompson2004). In Study 3, motivated reasoning will be prompted not by having participants make judgments about their own group, but rather by having them make valuations of the lives of members of groups depicted as morally innocent or guilty. People value the lives of innocent victims (Erlandsson, Reference Erlandsson2021; Erlandsson et al., Reference Erlandsson, Lindkvist, Lundqvist, Andersson, Dickert, Slovic and Västfjäll2020; Fehse et al., Reference Fehse, Silveira, Elvers and Blautzik2015; Gross and Wronski, Reference Gross and Wronski2021; Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Hopkins, Carlson and Raymond2012), and thus the prediction is the same for both studies: To the extent that people care about a group—be it their own or another group—they will engage in proportional thinking when it enables favorable judgments about that group.

3. Overview

In 3 studies, we present participants with scenarios about the loss of lives in 2 regions that differ in size. If proportional thinking applies, an X number of lost lives in the smaller region will be deemed equivalent in tragedy to a greater number of lost lives in the larger region. Study 1 offers a direct test of proportional thinking, without the influence of motivational factors, and by manipulating the critical factor: The proportion of lost lives in relation to the population size. Simulating the initial scenario in this introduction, we expect participants to react more strongly to the loss of a certain number of lives in a smaller region than in a larger one, and this tendency should be clearer the larger the difference in the size of those regions. In Study 2, we manipulate whether the smaller or the larger country is described as the participants’ ingroup. We predict that participants will endorse proportional thinking when it benefits the ingroup, that is, when the ingroup is the smaller country and, thus, each life is proportionally more valuable, compared to when the ingroup is the larger country. In Study 3, we present a scenario depicting 2 countries suffering casualties of war, and manipulate whether the war was started by the larger country (i.e., the smaller country is the victim and the larger is the aggressor) or by a third country (i.e., both countries are victims). We predict that there will be more proportional thinking when the smaller country is a victim, and the larger country is the aggressor, making it easier to judge the lives of the smaller country as more valuable. Additionally, Study 3 manipulates whether the proportions are framed in terms of collectives (e.g., the lives of 1,000 people) or individuals (e.g., 1 life). We expect that, if people are averse to devaluing individual lives, there will be less proportional thinking when considering individual lives, compared to when considering collectives.

4. Study 1

In Study 1, we focus on the question that started this paper: Imagine that 2 villages, one larger and the other one smaller, are involved in a tragic event (a natural disaster) where people in both villages die. Given that the population in one village is smaller than the other, is the loss of lives more tragic in that village? To directly test proportional thinking, we varied how much smaller one village was compared to the other. Specifically, we varied whether one village was 4 or 8 times smaller than the other. If participants are sensitive to proportions, (a) they should value the lives of the smaller village over those of the larger village (even when the 2 villages differ only in size, and not in other motivationally relevant attributes), and (b) this tendency should be greater when the larger village is 8 (vs. 4) times larger than the smaller village.

The hypotheses, methods, sample size, exclusion criteria, and analysis plan of Study 1 were preregistered (https://aspredicted.org/vz2fi4.pdf).

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants and Design

Two hundred participants were recruited from Prolific. As no participant failed the preregistered attention check, all 200 participants were included in the analysis (50.5% Female, 49.5% Male, M age = 44.35, SD age = 12.89). Design: Size difference (small vs. large) was manipulated within-participants, with the order of the 2 conditions counterbalanced between-participants. A sensitivity analysis indicates this sample size has 80% power to detect a minimum d = 0.18.

4.1.2. Procedure

Participants read about 2 villages (with fictitious names; see the Appendices). Participants were informed that both villages were involved in ‘a tragic event (e.g., a natural disaster) where people in both villages die’. In the small size difference condition, participants then learned that one of the villages was 4 times larger than the other. In the large size difference condition, participants instead learned that the larger village was 8 times larger than the smaller village. All participants went through both conditions in counterbalanced order, seeing a different pair of fictitious names in each.

After reading the instructions, participants completed 3 measures: ‘In which case do you think people in the village will suffer more from the death of ten people?’; ‘Which of these cases do you consider more tragic?’; and ‘Which of these cases do you consider to be a greater loss?’ For all 3, we further specified the options as ‘a case where ten people die in the village with [4/8] times more people, and therefore where those casualties represent a smaller proportion of the total population ([village name]) or a case where 10 people die in the village with fewer people, and therefore where those casualties represent a larger proportion of the total population ([village name])?’ Participants responded to these 3 items on a 9-point scale (1—10 people die in the village with many people; 5—both villages equally; 9—10 people die in the village with fewer people; all measures can be found in the Appendices). We counterbalanced between-participants whether the larger village was on the left or the right of the scale and adapted the questions accordingly.

Finally, participants completed an attention check: ‘In this study, you answered a question about’: (correct response: ‘Villages of different sizes’).

4.2. Results

As the 3 items were significantly correlated, for both size difference conditions (correlations > .43), we averaged them into a composite measureFootnote 2 for each condition, such that a higher rating indicates greater engagement in proportional thinking. In line with our hypothesis, most people responded on the side of the scale that valued the lives of the smaller village (69–71.5% vs. 20.5–24% who responded 5). More importantly, the preregistered one-sample t-test of each composite against the midpoint of the scale indicates that people valued the loss of lives in the smaller village more than the loss of those in the larger village—small size difference, M = 6.18, SD = 1.41, t(199) = 11.88, p < .001, d = 0.84; large size difference, M = 6.38, SD = 1.44, t(199) = 13.46, p < .001, d = 0.84. Moreover, this tendency was greater when the size difference between the 2 villages was larger, paired-samples t(199) = 3.18, p = .002, d = 0.23.

5. Study 2

Study 2 was meant to test if people are strategically flexible in their proportional versus absolute consideration of the value of lives in their country versus others.

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Participants

One hundred twenty-eight undergraduates from a large university in the United States were recruited in exchange for course credit (demographic data were not registered). A sensitivity analysis indicates that this sample size has 80% power to detect a minimum V = .25 (calculated in G*Power assuming α = .05; Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009).

5.1.2. Procedure and design

Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 conditions that differed in which countries the participants considered. In the favorable condition, participants answered a question that compared their ingroup (the Untied States) with a country that was roughly 4 times larger in population (China or India): For example, ‘Given that the population of China is 4 times larger than that of the US, how many lost Chinese lives would be equivalent in tragedy as the loss of an American life?’ We call this condition favorable, as the use of proportions implies that American lives are overall more valuable than those of the other country. Participants in the unfavorable condition read the same question, but with the United States as the larger country, and Egypt or Ethiopia as the smaller country. Finally, participants in the neutral condition considered 2 countries that did not include the United States (either the larger Ethiopia vs. the smaller Sri Lanka, or the larger Egypt vs. the smaller Syria). The complete list of questions can be found in the Appendices.

5.2. Results

We defined proportional thinking as judging 1 life from the smaller country to be equivalent to more than 1 life from the larger country. To test whether people strategically shift between proportional and absolute valuation of lives in their countries versus others, depending on what is favorable to their own country, we therefore compared the proportion of people who responded with a number greater than 1 (i.e., that 1 life in the smaller country is equivalent to more lives in the larger countryFootnote 3) in the conditions where US lives were involved. These proportions were: 29.5% in the unfavorable condition (where proportional thinking devalued US lives) versus 53.5% in the favorable condition (when proportional thinking valued US lives), χ2(1) = 5.14, p = .023, w = .24. A sensitivity analysis indicates that the sample size (n = 87) had 80% to detect a minimum effect size of φ = .30.

In addition, these proportions are significantly different (lower or higher, respectively) from the proportion of participants who engaged in proportional thinking in the neutral condition (41.5%; adjusted residuals = ±2.0, ps < .05). A linear-by-linear association test showed a significant trend of increasing proportional thinking from unfavorable to neutral to favorable conditions, χ2(1) = 5.10, p = .024, V = .20.

6. Study 3

Study 3 had several goals. First, like Study 2, it sought to test whether people engage in more or less proportional thinking depending on whether it leads to favorable conclusions, but it did so using a larger and more diversified sample. The a posteriori sensitivity analysis in Study 2 suggested that the sample size might have been too small to detect reliable effects. Study 3 uses a larger sample, making it much better powered to detect subtle effects.

Second, this study used a motivation other than ingroup favoritism. The motivation to favor the lives of one’s countrymen above those of people in other countries poses 2 obstacles to test motivated reasoning: (1) countries and their citizens differ in ingroup favoritism (i.e., not all participants are equally motivated to value the lives of their countrymen over those of others); and (2) it is likely that there are fairness constraints to valuing the lives of some people more than others simply because they are from different countries, with no further reason to devalue them. In this study, we sought to circumvent these constraints by asking people to make judgments about fictitious countries, and by depicting one country as clearly immoral and more dislikeable than the other. Specifically, in the critical condition of this study, participants made judgments about the lives of people from 2 countries at war, a larger aggressor country and a smaller victim country. The hypothesis was that proportional thinking (i.e., that a life of the smaller country is worth more lives of the larger country) would be more endorsed in this condition, compared to a control condition where the 2 countries were equally moral/victims.

Third, this study tests whether proportionality judgments differ depending on whether they refer to individuals (is 1 life in the smaller country equivalent to 4 lives in a country with a population 4 times larger?) or to collectives (are 1,000 lives in the smaller country equivalent to 4,000 lives in the larger one?). The results of Study 2 were suggestive, but they might be clearer still if collectives are considered instead of individuals (because there are constraints to devaluing individual lives, as discussed in the Introduction). We expect that proportional thinking is more prevalent when focusing on collectives versus individuals.

Fourth, because this individual–collective manipulation is implemented within-subjects, with the order of conditions manipulated between-subjects, it is possible to explore order effects. Here, we do not put forward a strong prediction. It could be that comparing individuals first (which might discourage proportional thinking) might then reduce proportional thinking when making an equivalent judgment for collectives (consistent with unit asking effects; Hsee et al., Reference Hsee, Zhang, Lu and Xu2013). Conversely, thinking of collectives first might then encourage proportional thinking for individuals.

Fifth, Study 2 used a free-response method, whereby participants could generate any number for the larger country that they deemed equivalent to 1 life in the smaller country. This method has its advantages (e.g., it shows that not all proportional responses are perfectly proportional: Some responses set the equivalence level at more than 1 but less than 4—see General Discussion). Still, it allows for extreme outliers. In order to prevent this, in Study 3, proportional statements were presented to participants (e.g., is 1 life in the smaller country equivalent to 4 lives in the larger country?), who expressed their (dis)agreement with them.

Finally, we tested whether proportional thinking is more prevalent when assessed via measures that prompt more objective calculation (the loss of a life in one country is equivalent to the loss of a life in another country) versus more subjective feeling-based judgments (the loss of a life in one country is as tragic as the loss of a life in another country).

6.1. Method

6.1.1. Participants and Design

Two hundred participants were recruited from Prolific, aiming for 100 participants per condition (202 ended up participating). Nineteen participants failed the attention checks and were excluded from the analyses, resulting in a final sample of 183 participants (58.5% Female, 39.3% Male, 1.6% Nonbinary, 0.5% Genderqueer, M age = 38.26, SD age = 13.05). Design was a 2 (comparison: individual vs. collective) X 2 (order: individual first vs. collective first) X 2 (motivation: control vs. motivated), with the latter 2 factors manipulated between-subjects. A sensitivity analysis indicates this sample size has 80% power to detect a minimum η p2 = .02.

6.1.2. Procedure

Participants read about 2 target countries (with fictitious names; see the Appendices) of differing population sizes that were involved in a war. Participants were split into 1 of 2 conditions, depending on whether both countries were victims of a third country (control condition) or instead the larger country was the aggressor (motivated condition). Those in the motivated condition may have read:

These 2 countries are neighbors and, throughout the years, Ponalose has frequently and violently attacked the people of Gosefer, sometimes causing cruel and violent deaths. After years of Gosefer suffering at the hands of Ponalose, the 2 countries engaged in a large battle where many lives were lost.

Participants in the control condition read instead that a third country was the aggressor of both target countries and the one who escalated the aggression. Then, participants in both conditions were reminded that the large country was 4 times larger than the small country and indicated their agreement with a series of statements that reflected proportional thinking. We manipulated within-participants the attribute being measured (tragic vs. equivalent) and the ratio of the comparison (1:1 vs. 1:4). For example, the equivalent-1:4 measure read: ‘The loss of 1 life from Gosefer is equivalent to the loss of 4 times those many lives (i.e., 4) in Ponalose’ (1—Totally disagree, 5—Neither agree nor disagree, 9—Totally agree; all measures can be found in the Appendices). All participants first answered the tragic and equivalent measures of the 1:1 ratio, followed by the same measures in the 1:4 ratio. After completing all 4 measures, participants again read and indicated their agreement with the statements, but this time the statements were framed so as to refer to collectives—rather than considering one versus 4 lives, participants considered 1,000 and 4,000 lives. Thus, one could read ‘The loss of 1,000 lives from Gosefer is equivalent to the loss of 4 times those many lives (i.e., 4,000) in Ponalose’. We counterbalanced between-participants whether the individual or collective measures were answered first.

At the end, participants completed an attention check where they had to indicate what the questions they answered were about (correct response: ‘The population of certain countries’) and identify the name of the country described as having the larger population (out of the 2 countries). Participants who failed one or both of these checks were excluded from the analyses.

6.2. Results

Given that the 4 different items that result from the combination of both attribute and ratio loaded on a single factor (all loadings > .59), we standardized the responses to each item and averaged them into a single composite. A higher rate of agreement indicates a greater valuation of the lives of the smaller country and, therefore, greater engagement in proportional thinking. We ran a repeated-measures ANOVA with comparison, order, motivation, and all higher-order interactions as predictors of the agreement ratings (see the Appendices for exploratory analyses including effects of attribute and ratio). We found evidence of motivated proportional thinking: When the larger country was described as the aggressor and the smaller country as the victim, participants expressed more agreement with a proportional valuation of the lives lost (M = 0.22, SE = 0.06) than when both countries were victims (M = −0.22, SE = 0.05), F(1, 179) = 18.04, p < .001, η p2 = 0.09. Additionally, participants displayed more proportional reasoning when thinking about collective lives (M = 0.08, SE = 0.06) than when thinking about individual lives (M = −0.08, SE = 0.05), F(1, 179) = 19.58, p < .001, η p2 = 0.10, regardless of how the countries were described (comparison X motivation, F(1, 179) = 0.07, p = .791, η p2 < .001). We found no significant main effect of order nor its interactions, Fs < 3.70, ps > .056.

7. General discussion

We assessed whether people engage in proportional thinking when valuing the lives of people in different regions, in particular, whether people judge a certain number of lives in a region as more valuable than the same number in another region with a larger population. Results show that a substantial number of people engage in this form of proportional thinking (Study 1), and that this tendency to engage in proportional thinking is modulated by the predicted factors: It is greater when it leads to desirable conclusions (valuing the lives of a cherished group above those of another group; Studies 2–3), and when it refers to collectives versus individuals (Study 3). These studies hope to contribute to different areas of psychology on how people value lives, including proportional thinking, motivated reasoning, and judgments of individuals versus collectives, which we shall now discuss.

Results show that a sizeable fraction of participants engaged in proportional thinking, considering a certain number of lives in a certain region to be of greater or lower value (e.g., more or less tragic, when lost) relative to the number of lives in other regions of different sizes. This is by no means a universal tendency. For instance, the results of Study 2 show that only 41.5% of participants in the neutral condition engaged in proportional thinking. Still, this is a considerable number, far from negligible. And in Study 1, which offers a more direct test of proportional thinking, this percentage was a clear majority (69–71.5%).

Moreover, we collected participants’ final responses, and not their intuitive or impulsive response tendencies. It is possible that some participants had a tendency to engage in proportional thinking, which they then corrected because they deemed it inappropriate (Mata, Reference Mata2016). Supporting this hypothesis that people are somewhat conflicted about whether proportional thinking of this sort is acceptable, the results of Study 2 show that not all participants who engaged in proportional thinking (i.e., who defended that 1 life in the smaller group is equivalent to a greater number of lives in a larger group) set this greater number at the exact equivalence (i.e., if the larger country is 4 times as populous as the smaller one, then 1 life in the latter equals 4 lives in the former). Indeed, the average number generated by participants was slightly below the proportional equivalence (several participants chose a number above 1 but below 4). Likewise, in Study 3, agreement rates with proportional logic were far from high, which also suggests some degree of decisional conflict. Future studies might try to dissociate people’s final responses (and the corrective efforts that they underwent) from people’s intuitive response tendencies, in order to test the automaticity of this form of proportional thinking, and measure decisional conflict (Mata, Reference Mata2019, Reference Mata2020; Simão and Mata, Reference Simão and Mata2023) in proportional thinking.

Among other factors, whether people spontaneously think in proportions is likely to depend on whether the lives at stake are those of individuals or collectives. The rate of proportional thinking that we noted above (the 41.5% observed in the neutral condition of Study 2) was observed when participants made judgments about individual lives. Presumably, the rate of proportional thinking would be higher still if collective lives were at stake, as we observed in Study 1 (or if motives were involved, as in some conditions of Studies 2–3). Indeed, in Study 3, participants expressed less agreement with proportional thinking when it referred to individuals (i.e., 1 life in one country is equivalent to 4 lives in a larger country) than when it pertained to a collective (i.e., 1,000 lives in one country are equivalent to 4,000 lives in a larger country). Thus, judgments of individuals seem to be less sensitive to proportional considerations. Similarly, participants also revealed less proportional thinking when comparing lives 1 to 1 (i.e., 1 life in one country is equivalent to 1 life in a larger country), than when comparing them 1 to 4 (i.e., 1 life in one country is equivalent to 4 lives in a larger country; see the Appendices)—again, participants were less willing to engage in proportional thinking when considering individual lives.

It is noteworthy that, in Study 3, the same participants who opposed proportional judgments about individuals were nevertheless more endorsing of those judgments for collectives. One might expect that they would be constrained to show different standards for similar judgments (whether the lives of some are of different worth than the lives of others) and similar proportions. Still, at least some participants changed their judgments when considering collectives versus individuals. It is possible that, under less constraining circumstances (e.g., in a study with a between-subjects design), the rate of proportional thinking for collectives would be higher still.

Study 3 also bears relevance to whether different measures and different comparisons prompt different reactions: Participants endorsed proportional thinking more strongly when judging equivalence (vs. tragedy) and comparing 1 against 4 (vs. 1 against 1; see the Appendices). The effect of the attribute is worth discussing further. People are sensitive to proportionality when asked to make a more quantitative/analytical judgment, such as whether one magnitude of loss is equivalent to another, but more qualitative/emotional attributes, such as how tragic a loss is, do not seem to allow for comparisons or mathematical considerations. This suggests that different questions may reveal quite different judgments, with some being much more sensitive to proportionality than others. Moreover, this ties with results from other areas of research in which similar dissociations can be observed depending on whether measures are more quantitative/objective versus qualitative/subjective (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Vogel, Grüning and Mata2023; Persson et al., Reference Persson, Erlandsson, Slovic, Västfjäll and Tinghög2022; Walco and Risen, Reference Walco and Risen2017).

In addition, the effect of the ratio in Study 3 is also noteworthy: People show less proportional thinking for 1-to-1 comparisons (comparing 1 life from the smaller country against 1 life from the larger country) than for 1-to-4 comparisons (comparing 1 life from the smaller country against 4 lives from the larger country). In a way, 1-to-4 comparisons can be regarded as being halfway between judgments about individuals and judgments about collectives, and thus, this result also supports that there is more proportional thinking for collectives.

With regard to motivated reasoning, the present studies manipulated the desire to value one country over another one in different ways: In Study 2, participants in the critical conditions compared the lives of their countrymen against those of people in another country. The motivation here was ingroup favoritism: The tendency to value the lives of one’s group about those of other groups. And indeed, results show that people are more likely to attend to a country’s relative size when this favors the lives of their ingroup than when it places more value on the lives of the outgroup. In Study 3, we again showed differential sensitivity to the countries’ relative sizes, which again favored the smaller country over a larger one, but this time as a function of whether one country was a victim and the other one an aggressor. These results support Erlandsson et al.’s (2021) analysis, which identifies group membership and innocence as 2 predictive features of the valuation of lives.

These studies bear relevance to how people form their judgments about conflicts (e.g., the current wars in Ukraine and in the Middle East) and the casualties of lives in the different countries involved. In the mathematics of lives involved in wars, proportional facts abound. For instance, in the current Israeli–Palestinian conflict, there were reported hostage exchanges where one Israeli prisoner was exchanged for 300 Palestinian prisoners. As another example, many more Palestinian lives than Israeli lives have been lost since the war began, prompting discussions about proportionality. It is likely that people’s use of proportional thinking when considering these numbers depends to a large extent on where they stand in this conflict and which sides they see as the aggressor and the victim. Whereas previous studies in motivated judgments about dilemmas depicting human lives have been criticized (Bauman et al., Reference Bauman, McGraw, Bartels and Warren2014) for using artificial scenarios (e.g., considering the sacrifice of a loved one, like a close relative, or, on the opposite end, of an evil person, like a terrorist or a serial killer; Mata et al., Reference Mata, Vaz and Mendonça2022; Vega et al., Reference Vega, Mata, Ferreira and Vaz2021), these studies might speak to more realistic and consequential dilemmas. But of course, that remains to be shown in future research.

Indeed, these studies leave unanswered several questions, which future research might investigate. For one, future studies might assess key moderators of whether people value the lives of their countrymen more than those of people in other countries, including national identity and political orientation. For instance, among American participants, conservatives are more likely than liberals to support sacrificing a greater number of people in another country in order to save the lives of their countrymen (Slovic et al., Reference Slovic, Mertz, Markowitz, Quist and Västfjäll2020). It is likely that the results of Study 2 would be qualified by participants’ political leanings. Moreover, in Study 3, where participants tended to judge the lives of victims as more valuable than the lives of aggressors, it is not clear whether this tendency to engage in proportional thinking was due to a desire to protect/value the lives of victims or to punish/devalue the aggressor (to be clear, these motives are not mutually exclusive).

Moreover, the present studies investigated how motivated reasoning can prompt proportional thinking. However, future research could explore the reverse causal logic: How proportional thinking can facilitate motivated reasoning. For instance, participants might feel constrained to state that 1 life of a certain group (e.g., their country or some other cherished group) is worth more than 1 life of another group. However, the disproportion in group sizes might facilitate making that motivated judgment. Future studies might compare whether motivated reasoning (e.g., valuing the lives of one’s countrymen over those of others) is more clearly observed when the difference in group sizes is presented (as in the present studies) versus when this information is absent, thus potentially hindering proportional thinking.

8. Conclusions

In sum, people engage in proportional thinking when comparing the value of the lives of people in different groups. Specifically, they consider that the loss of a certain number of lives in a smaller group is equivalent to the loss of a greater number of lives in a larger group. Moreover, this form of proportional thinking is shaped by motivated reasoning: People show more of it when it benefits their ingroup (vs. the outgroup) or a victim group (vs. an aggressor group). Finally, this form of proportional thinking is more frequent when thinking about the lives of collectives versus individuals.

These results have implications for how to frame statistics in order to influence judgments about human lives. Our studies join others in suggesting that the same number of lives can be valued more or less depending on various factors—in particular, whether they represent a larger proportion in comparison to a reference group, whether those lives belong to people in one’s group (or any other group one cares about), and whether they refer to individuals rather than collectives.

Data availability statement

Materials, data, and analyses code can be accessed online: https://osf.io/af2vs/?view_only=1db7ff09e7d94bb58a102f2bbd22c566.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Appendices

Appendix A: Study 1 measures

The full list of statements presented in Study 1 is as follows:

1:4 A. ‘In which case do you think people in the village will suffer more from the death of ten people: a case where ten people die in the village with four times more people, and therefore where those casualties represent a smaller proportion of the total population ([large village]) or a case where ten people die in the village with fewer people, and therefore where those casualties represent a larger proportion of the total population ([small village])?’

1:4 B. ‘Which of these cases do you consider more tragic: a case where ten people die in the village with four times more people, and therefore where those casualties represent a smaller proportion of the total population ([large village]) or a case where ten people die in the village with fewer people, and therefore where those casualties represent a larger proportion of the total population ([small village])?’

1:4 C. ‘Which of these cases do you consider to be a greater loss: a case where ten people die in the village with four times more people, and therefore where those casualties represent a smaller proportion of the total population ([large village]) or a case where ten people die in the village with fewer people, and therefore where those casualties represent a larger proportion of the total population ([small village])?’

1:8 A. ‘In which case do you think people in the village will suffer more from the death of ten people: a case where ten people die in the village with eight times more people, and therefore where those casualties represent a smaller proportion of the total population ([large village]) or a case where ten people die in the village with fewer people, and therefore where those casualties represent a larger proportion of the total population ([small village])?’

1:8 B. ‘Which of these cases do you consider more tragic: a case where ten people die in the village with eight times more people, and therefore where those casualties represent a smaller proportion of the total population ([large village]) or a case where ten people die in the village with fewer people, and therefore where those casualties represent a larger proportion of the total population ([small village])?’

1:8 C. ‘Which of these cases do you consider to be a greater loss: a case where ten people die in the village with eight times more people, and therefore where those casualties represent a smaller proportion of the total population ([large village]) or a case where ten people die in the village with fewer people, and therefore where those casualties represent a larger proportion of the total population ([small village])?’

Appendix B: List of fictitious locations (Studies 1 and 3)

In Studies 1 and 3, the fictitious names assigned to each village (Study 1) or country (Study 3) were sampled from the following list: Begalif, Birasin, Dimasat, Gosefer, Katigal, Kirikod, Pevanaf, Ponalose, Tereben, and Timifos.

Appendix C: Study 2 measures

The full list of statements presented in Study 2 is as follows:

Favorable condition. ‘Given that the population of [China/India] is 4 times larger than that of the US, how many lost [Chinese / Indian] lives would be equivalent in tragedy as the loss of an American life?’

Neutral condition. ‘Given that the population of Ethiopia is 4 times larger than that of Sri Lanka, how many lost Ethiopian lives would be equivalent in tragedy as the loss of a Sri Lankan life?’ or ‘Given that the population of Egypt is 4 times larger than that of Syria, how many lost Egyptian lives would be equivalent in tragedy as the loss of a Syrian life?’

Unfavorable condition. ‘Given that the population of the US is 4 times larger than that of [Egypt/Ethiopia], how many lost American lives would be equivalent in tragedy as the loss of an [Egyptian/Ethiopian] life?’

Appendix D: Study 3 measures

The full list of statements presented in Study 3 is as follows:

Individual-Tragic-1:1. ‘The loss of a life from [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country) is as tragic as the loss of a life from [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country)’.

Individual-Equivalent-1:1. ‘The loss of a life in [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country) is equivalent to the loss of a life in [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country)’.

Individual-Tragic-1:4. ‘The loss of 1 life from [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country) is four times more tragic than the loss of 1 life from [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country)’.

Individual-Equivalent-1:4. ‘The loss of 1 life in [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country) is equivalent to the loss of four times those many lives (i.e., 4) in [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country)’.

Collective-Tragic-1:1. ‘The loss of 1,000 lives from [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country) is as tragic as the loss of 1,000 lives from [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country)’.

Collective-Equivalent-1:1. ‘The loss of 1,000 lives in [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country) is equivalent to the loss of 1,000 lives in [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country)’.

Collective-Tragic-1:4. ‘The loss of 1,000 lives from [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country) is four times more tragic than the loss of 1,000 lives from [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country)’.

Collective-Equivalent-1:4. ‘The loss of 1,000 lives in [small country] (the smaller[, attacked] country) is equivalent to the loss of four times those many lives (i.e., 4,000) in [large country] (the larger[, aggressor] country)’.

All the 1:1 items were reverse-coded such that higher values indicated higher agreement with proportional thinking.

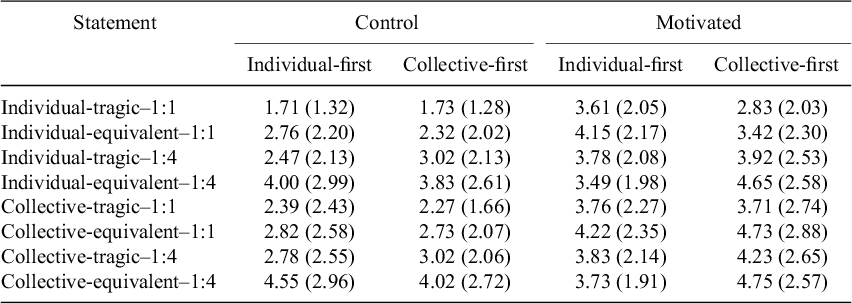

Table E1 Study 3 exploratory results

Appendix E: Study 3 exploratory analyses

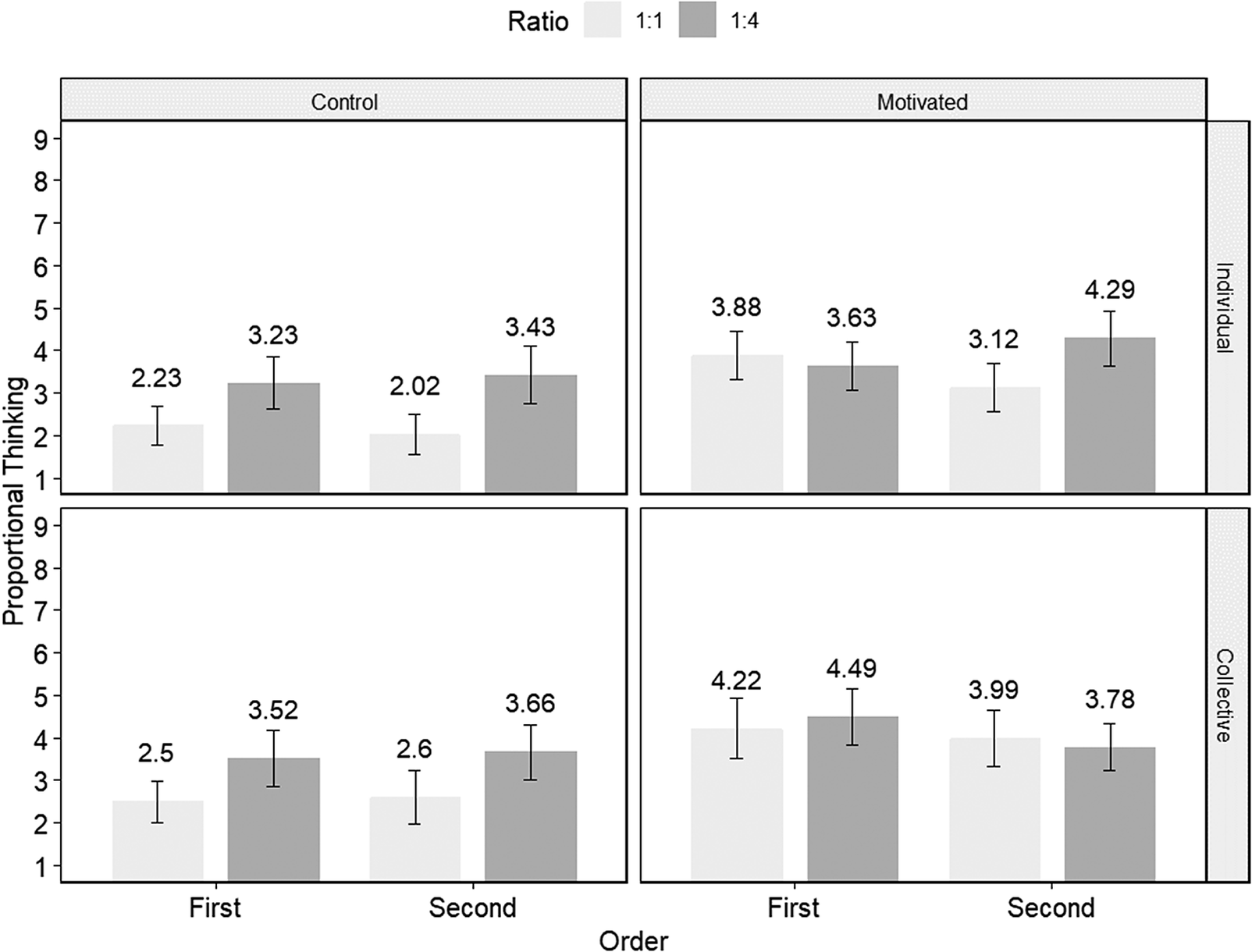

For exploratory purposes, we entered all 4 measures of agreement with proportional thinking into a repeated-measures ANOVA that included as predictors attribute and ratio, as well as comparison, order, motivation, and all possible interactions as predictors. We found main effects of both attribute, F(1, 179) = 49.22, p < .001, η p2 = 0.22, and ratio, F(1, 179) = 25.30, p < .001, η p2 = 0.12 (see Table E1 for full results), such that participants endorsed proportional thinking more strongly when judging equivalence (M = 3.79, SE = 0.09; vs. tragedy: M = 3.07, SE = 0.09) and comparing 1 against 4 (M = 3.78, SE = 0.09; vs. 1 against 1: M = 3.08, SE = 0.09). Moreover, motivation significantly interacted with both attribute, F(1, 179) = 6.89, p = .009, η p2 = 0.04 (Figure E1), and ratio, F(1, 179) = 10.40, p = .001, η p2 = .05 (Figure E2), such that our manipulation was stronger for the tragedy and for the 1:1 items, respectively. Agreement ratings for all statements across comparison, motivation, and order can be found in Table E2.

Table E2 Mean (standard deviation) agreement with each statement, by comparison, motivation, and order (Study 3)

Note: Agreement ratings for all 1:1 statements are reverse-coded such that a higher value indicates higher agreement with proportional thinking.

Figure E1 Mean agreement with proportional thinking (and 95% CIs) by attribute, order, motivation, and comparison (Study 3).

Figure E2 Mean agreement with proportional thinking (and 95% CIs) by ratio, order, motivation, and comparison (Study 3).