Introduction

Even before the current surge of scholarly interest (Philpott, Reference Philpott2009), social scientists were acutely aware that religion can be a powerful political force. Students of public opinion and mass political participation, in particular, have a long‐standing interest in the effects of religious faith, membership and practice on political attitudes and political behaviour. But only recently have they recognised the importance of secular attitudes.

This is not to say that scholars have been blind to the waning of religion in some parts of the world – on the contrary. In what is probably the most prominent treatise on religion's role in the modern political world, Norris and Inglehart (Reference Norris and Inglehart2011) carefully document the long‐term decline of religion in some areas such as Western Europe. However, their perspective is the traditional view of secularisation as a decline of interest in religion (Sommerville, Reference Sommerville1998). Hence, they treat secularism at the micro‐level, chiefly as the absence of religion measured on three dimensions: believing, behaviour and belonging (membership).

A more recent strand of research, however, stresses that a growing number of citizens are not just non‐religious but have a secular identity (e.g. Beard et al., Reference Beard, Ekelund, Ford, Gaskins and Tollison2013; Baker & Smith, Reference Baker and Smith2015; Clements & Gries, Reference Clements and Gries2016; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Layman, Green and Sumaktoyo2018; Layman et al., Reference Layman, Campbell, Green and Sumaktoyo2021) and express secular views and beliefs (Layman et al., Reference Layman, Campbell, Green and Sumaktoyo2021, p. 80). These include, but are not limited to humanism, the rejection of dogma, and a commitment to science (Layman et al., Reference Layman, Campbell, Green and Sumaktoyo2021, pp. 81–82).

Like religion, secularism has several facets, one of which is political secularism.Footnote 1 Politically secular citizens demand strict limits on the ‘role of religious beliefs in political life’ (Beard et al., Reference Beard, Ekelund, Ford, Gaskins and Tollison2013, p. 758). As an attitude, political secularism is hence the micro‐level expression of secularism as a political principle, which holds that the state should be neutral and should not grant any privileges to religious groups and their members (Cliteur & Ellian, Reference Cliteur and Ellian2020).

Conceptually, secular citizens differ from three other, partially overlapping, groups that have recently come under scientific scrutiny. The ‘nones' (Baker & Smith, Reference Baker and Smith2009, p. 720) are citizens who explicitly identify as having no religion. Although this implies that they score as non‐religious on the belonging dimension, some of them, the ‘unchurched’, still hold on to religious beliefs (Baker & Smith, Reference Baker and Smith2009, p. 721). Conversely, atheists and agnostics score low on belief, but some may still belong to religious communities and may even practice (Baker & Smith, Reference Baker and Smith2009, p. 721).

It stands to reason that most atheists also subscribe to secularism, but the same is not necessarily true for agnostics and the unchurched. Contrarily, even religious citizens may embrace political secularism, which makes studying the roots of political secularism all the more important.

Scientific interest in secularism is currently growing because of its political consequences. More specifically, political secularism is closely tied to morality politics, which encompasses a whole host of contested and often polarising issues including assisted reproductive technology (ART), euthanasia, physician‐assisted suicide, same‐sex marriage and, most prominently, abortion. While there is some scientific debate over what exactly constitutes and delineates morality policies and while a recent review identifies at least four different (yet partially overlapping) strands of research within the field, the same review also points out one important commonality: morality policies are defined by their ‘entanglement with religion’ (Mourão Permoser, Reference Mourão Permoser2019, p. 322).

In West European countries, (political) secularism has strong effects on policy preferences across the whole ART domain and related fields, on citizens’ views on abortion and on support for marriage and adoption rights for same‐sex couples (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2020a, Reference Arzheimer2020b; Di Marco et al., Reference Di Marco, Hichy and Sciacca2020, Reference Di Marco, Hichy, Coen and Rodriguez‐Espartal2018; Hichy et al., Reference Hichy, Sciacca, Di Marco and De Pasquale2020, Reference Hichy, Gerges, Platania and Santisi2015; Magelssen et al., Reference Magelssen, Le and Supphellen2019). Similarly, Layman et al. demonstrate that in the United States, secularism is strongly linked to positive views on same‐sex relationships and homosexuals, to ‘support for science and scientific approaches to societal issues’ and to other attitudes that can be labelled as liberal in the American context (Layman et al. Reference Layman, Campbell, Green and Sumaktoyo2021, p. 91; see also Beard et al. Reference Beard, Ekelund, Ford, Gaskins and Tollison2013, p. 760).

In short, political secularism is an important attitude, because it affects citizens' positions on a host of questions that involve matters of identity and morality. These issues are characterised by often passionate conflicts over first principles that can involve large segments of the population and can therefore be highly disruptive (Mooney, Reference Mooney and Mooney2001, pp. 7–15). A further decline of religion will likely lead to higher levels of political secularism in many rich countries, which somewhat paradoxically may in turn lead to an increasing polarisation between secular and religious actors and even more intense conflicts over the political role of religion (Pickel, Reference Pickel2017, pp. 260–261).

Relatively little is known about the roots of secularism and particularly about its relationship with other fundamental orientations. In the remainder of this research note, I briefly summarise the extant knowledge on the correlates of political secularism and show how basic human values can further contribute to understanding its sources. Using survey data from Germany, I then demonstrate that political secularism is related to socio‐demographics and the main facets of religion in a way that is in line with expectations and broadly resembles the patterns found in studies from the United States. However, even after controlling for these variables, basic human values exert theoretically plausible, substantial and independent effects on secularism.

Political secularism, religion and values

For Europe and North America, the variation of religion along the lines of gender, education and age/cohorts is well‐documented. The latter division is particularly interesting because it points to a putative mechanism (loss of intergenerational transmission) behind the decline of religion in Europe (Voas, Reference Voas2009).

Conversely, secularism is a relatively new field of study, and comparatively little is known about its sources and correlates. Beard et al. (Reference Beard, Ekelund, Ford, Gaskins and Tollison2013) sketch what is perhaps the most detailed picture of political secularism's antecedents in the United States. Using data from 2007, they show that political secularismFootnote 2 is more prevalent amongst White, male, younger, and better educated voters. Even controlling for these variables, growing up in households that were not very religious and living in the Northeastern and Western regions of the United States further contributes to being politically secular. For Europe, Ribberink et al. (Reference Ribberink, Achterberg and Houtman2018) show – based on ISSP data from 16 countries collected in 1998 and 2008 – that individual ‘anti‐religiosity'Footnote 3 is more pronounced amongst men, non‐believers, and people who do not go to church. Net of these variables, anti‐religiosity was also higher in countries with high levels of societal secularisation. Education has no significant effect.

In sum, the existing evidence suggests that political secularism is related to individual religion on the one hand and socio‐demographics (which can be understood as proxies for socialisation) on the other. Moreover, the differences between countries (in Europe) and census regions (in the United States) suggest that one's wider political‐cultural environment also plays a relevant role. What is not clear, however, is whether and how political secularism – a rather specific attitude – is affected by more abstract basic human values.

This gap in the literature should be addressed for two interrelated reasons. First, scientific interest in political secularism largely stems from its link to the field of morality politics, which in turn is routinely assumed to be connected to fundamental values (see, e.g., Mooney, Reference Mooney and Mooney2001). But while the link between political secularism and morality policy preferences is by now firmly established, the putative connection between values and secularism has rarely been investigated. Second, past research has shown that certain basic human values are associated with religion. However, political secularism is conceptually different from an absence of religion. It is therefore not clear how this difference is reflected in its empirical relationships with basic human values and whether basic human values matter at all for political secularism once its relationship with religion is controlled for.

Basic human values and political secularism

Values are a central concept in politics. For decades, their study in political science was shaped by the work of Ronald Inglehart on post‐materialism. But more recently, the concept of basic human values (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012), which originated in cross‐cultural psychology, has risen to prominence across all social sciences. While Schwartz has made some modifications to his theory over the years, its core claims remain the same. Basic human values are supposed to be universal in a double sense: they apply in all domains of human life, and their structure is the same across all cultures.

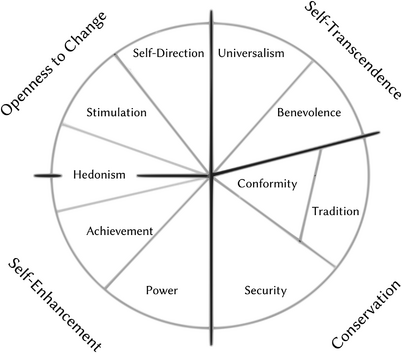

Basic human values are far more general than ordinary attitudes and beliefs. They motivate human behaviour and serve as criteria for selecting amongst alternative courses of action (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012, pp. 3–4). While some values are closely related (e.g. achievement and power), others are directly opposed to each other (e.g. power and universalism), requiring humans to choose one over the other. This led Schwartz to postulate a circular structure (see Figure 1) from which four domains can be derived that form two higher order dimensions: ‘openness to change’ vs ‘conservation’, on the one hand, and ‘self‐enhancement’ versus ‘self‐transcendence’ on the other (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012, pp, 8–10).

Figure 1. The structure of basic human values.

Empirical patterns akin to this structure have emerged in data from dozens of countries and cultures. Moreover, comparative and single‐country studies show that basic values have plausible and substantial effects on various policy preferences and other political attitudes (Goren et al., Reference Goren, Schoen, Reifler, Scotto and Chittick2016) and, indirectly, on voting (Caprara et al., Reference Caprara, Vecchione, Schwartz, Schoen, Bain, Silvester, Cieciuch, Pavlopoulos, Bianchi, Kirmanoglu, Baslevent, Mamali, Manzi, Katayama, Posnova, Tabernero, Torres, Verkasalo, Lönnqvist, Vondráková and Caprara2017) and other forms of political behaviour (Vecchione et al., Reference Vecchione, Schwartz, Caprara, Schoen, Cieciuch, Silvester, Bain, Bianchi, Kirmanoglu, Baslevent, Mamali, Manzi, Pavlopoulos, Posnova, Torres, Verkasalo, Lönnqvist, Vondräkovä, Welzel and Alessandri2014).

Beginning with Schwartz's own work in the 1990s, researchers have also demonstrated links between basic human values and various facets of religion. Schwartz originally argued that transcendence is at the heart of most religious systems. Therefore, values in the self‐transcendence (as opposed to self‐enhancement) domain should have a strong association with religion, especially with religious belief. Moreover, religion should also be associated with values in the conservation domain (Schwartz & Huismans, Reference Schwartz and Huismans1995, pp. 91–94).

While the size of the effects varies somewhat across cultures, religions, and denominations, a meta‐analysis and two large comparative surveys show that the latter relationship does hold around the globe (Saroglou et al., Reference Saroglou, Delpierre and Dernelle2004; Saroglou & Craninx, Reference Saroglou and Craninx2021). However, the same data also show that in the self‐enhancement and self‐transcendence domain, only hedonism and benevolence consistently display the expected associations with religion and that these effects are rather weak. Crucially, universalism is unrelated to religion (Saroglou et al., Reference Saroglou, Delpierre and Dernelle2004, p. 727).

Because political secularism has so far been rarely analysed at the individual level, little is known about the effect of basic human values on this attitude. To date, there are only two empirical studies. Di Marco, Hichy and their colleagues analyse the relationship between human values and their subjects’ views on pre‐implantation genetic diagnosis (Di Marco et al., Reference Di Marco, Hichy, Coen and Rodriguez‐Espartal2018) and same‐sex marriage (Di Marco et al., Reference Di Marco, Hichy and Sciacca2020), treating secularismFootnote 4 as a potential mediator. Within this framework, they find a positive correlation of secularism with the self‐transcendence domain and a negative correlation with the conservation domain.

Yet, these analyses do not include any control variables (not even religion) and rely on two small samples of Spanish university students. Moreover, Di Marco, Hichy and colleagues focus on the higher order dimensions and give little consideration to the underlying basic values themselves, whereas the bulk of the literature on basic values and politics/religion takes a disaggregated view to study the effects of individual values.

However, deriving hypotheses from the existing body of theoretical and empirical work on basic human values is straightforward. Because (political) secularism is not concerned with religion's personal dimension but with the role that religion should play in public, Schwartz's original argument does not apply, i.e there is no theoretical reason to assume a relationship between political secularism and the conflict between self‐enhancement and self‐transcendence. This rules out effects of universalism, benevolence, achievement and power.

Conversely, values aligned with the openness to change versus conservation dimension should be strongly associated with one's views on the proper role of religion in politics. More specifically, in the openness to change domain, self‐direction, i.e. a desire for ‘independent thought’, ‘autonomy’, ‘creativity, freedom’ (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012, p. 5) is most obviously akin to political secularism. Hypothesis 1 is therefore: Self‐direction is linked to higher levels of political secularism (H1). A relationship with either hedonism or stimulation is much less plausible.

In the conservation domain, tradition, i.e. ‘respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that one's culture or religion provide’ (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012, p. 5) is directly opposed to political secularism. This leads to hypothesis 2: Tradition is linked to lower levels of political secularism (H2). Conformity (restraint to ‘violate social expectations or norms’; (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012, p. 6)) is closely related to tradition. But once a society becomes more secular, social norms are first being contested and then may change so that it may be unclear with whose and which expectations one should conform. Similarly, Schwartz links security (‘safety, harmony, and stability of society, of relationships, and of self’ (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012, p. 6)) to religion (Schwartz & Huismans, Reference Schwartz and Huismans1995, p. 92).Footnote 5 Secularism could thus be seen as a threat to security, but once the role of religion becomes controversial in a society, an effect of security on political secularism is much less plausible than that of tradition.

The circular structure of the values and the in‐person centring of the answers (see note 8) create collinearity amongst the indicators. Following Schwartz's recommendation to limit the number of values that enter a model as regressors and to select these values a priori on theoretical grounds, the analysis will focus on the respective roles of self‐direction and tradition.

Because tradition (and to a lesser degree self‐direction) correlates with religion, which is in turn strongly related to secularism, any effects of basic human values on political secularism should be estimated while holding religion constant. Moreover, the literature reviewed in the previous section suggests that gender, age and education should also be controlled for. Finally, the findings by Beard et al. and Ribberink et al. point to the effect of political‐cultural differences on political secularism. This last point is particularly relevant for the analysis at hand. The data introduced in the next section were collected in Germany, where the country's post‐war division resulted in a ‘natural experiment in religious history’ (Stolz et al., Reference Stolz, Pollack and De Graaf2020, p. 627). Therefore, region (east vs. west) is a final crucial control.

Case selection: Germany

Germany is particularly well suited for studying the relationship between religion, political secularism and basic human values. On the one hand, it mirrors Western Europe's general trend of a decline in (organised) religion. Church membership, which was near universal in the 1950s, was down to about 50 per cent in the early 2020sFootnote 6 and is set to fall further.

On the other hand, Germany is by no means a completely secularised country. State‐religion relations have been contentious ever since the reformation and the subsequent struggle between Catholic and Protestant territories. In postwar Western Germany, the denominational conflict eventually transformed into a broader secular‐religious cleavage that is represented by a strong Christian Democratic party to the present day (Raymond, Reference Raymond2011), making the Federal Republic a textbook case of a ‘religious‐world country’ (Engeli et al., Reference Engeli, Green‐Pedersen, Larsen, Engeli, Green‐Pedersen and Larsen2012, p. 18) where morality issues are often politicised.

In line with the Weimar tradition, West Germany's constitution (which became the constitution of unified Germany in 1990) approached organised religion with ‘benevolent neutrality’ (Cremer, Reference Cremer2021) and encouraged close cooperation between the churches and the state. While the system has recently been opened to smaller Christian and non‐Christian organisations, the Catholic Church and the federation of mainstream protestant churches (Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland or EKD for short) are still the main beneficiaries of this arrangement. They enjoy a multitude of financial advantages and legal privileges, act as major contractors for the provision of publicly funded care services, and play a constitutionally enshrined role in the state education system.

Conversely, any involvement with religion was strongly discouraged in Eastern Germany (Stolz et al., Reference Stolz, Pollack and De Graaf2020, p. 627). The regime successfully disrupted intergenerational religious transmission (Stolz et al., Reference Stolz, Pollack and De Graaf2020, pp. 628–629), causing an ‘accelerated … secular transition’ (Stolz et al., Reference Stolz, Pollack and De Graaf2020, p. 626). At the time of unification in 1990, 82.5 per cent of Westerners but only 28.6 of Easterners belonged to one of the mainstream churches, although both regions had started out at very similar levels in 1950 (Stolz et al., Reference Stolz, Pollack and De Graaf2020, p. 629). Since then, membership has further declined in the East, and disaffiliation began to speed up in the West. Even so, the constitutional position of the churches remains entrenched, and religious interests remain overrepresented in parliament (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2020b).

In a nutshell, Germany's complicated political‐religious history and its resulting ‘religious‐world’ status mean that attitudes on political secularism should be politically relevant, salient and heterogeneous. At the same time, while Germany is an interesting country‐case in its own right, findings should generalise fairly well to other European countries, particularly to those that also fall into the ‘religious‐world’ category.

Data and methods

The data analysed here were collected for ‘Problems of Representation in the Domain of Biopolitics’ (PRDB) project and are freely available from the author's dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Z8VYBK. The sample is representative of the German population in 2016 and encompasses a host of measures on political attitudes. Crucially, the survey includes both a validated scale for political secularism (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2022)Footnote 7 and an abridged version of the Schwartz Portraits Values Questionnaire (PVQ) with single‐item measures for both tradition and self‐direction.Footnote 8

The survey also contains four indicators that tap into three different facets of religion: belonging to a religion or churchFootnote 9, praying outside of services and frequency of church attendanceFootnote 10 (behaviour) and self‐assessed religiosity (belief or internal commitment).Footnote 11 To account for potential age or cohort differences, respondents were divided into broad age groups (18–35, 36–65, 66 and older). The wide spectrum of qualifications in Germany was recoded to three levels of educational attainment: low (less than 10 years of schooling), intermediate (10 years of schooling) and high (more than 10 years of schooling). Finally, two more dichotomous variables were included to control for gender and region (east vs. west).

The literature on religion and basic human values is generally silent as to their causal order and focuses on their zero‐order and partial correlations. This seems appropriate, because both religious belief and relative importance of human values are very general orientations that may mutually influence each other. The same applies to values and the behaviour/belonging facets: while value priorities are bound to play a role in the decision to become, or remain as, a member of a religious organisation and take part in its rituals, membership and collective practice will in turn shape one's values through socialisation.

The situation is somewhat more clear‐cut for the nexus between basic human values and political secularism. The latter is a very specific attitude: a view of the proper role of religion in political life. Conversely, the former represents very general guiding principles that can inform a broad range of choices in politics and life. Hence, values should be causally prior to secularism. Similarly, secularism can be understood as the result of the socialisation experiences that are proxied by gender, age and education, but not vice versa.

The nature of the relationship between religion and political secularism is more ambiguous. Does the appeal of political secularism undermine the strength of religious belief and attachment? Or does one become politically secular because one's religion is more a matter of habit and cultural identity than of religious zeal?

Since most Europeans seem to acquire (or not) religion very early in life through socialisation (Voas, Reference Voas2009), prima facie a causal effect of religion on political secularism is highly plausible. Yet recent research shows that processes of political socialisation may set in at pre‐school age, much earlier than previously thought (van Deth et al., Reference Deth, Abendschön and Vollmar2011) and may last well into the third decade of life (Neundorf & Smets, Reference Neundorf and Smets2017). Therefore, a causal effect of political secularism on religion cannot be ruled out.

Because the aim of the analysis is largely descriptive and because there are no panel or experimental data available for separating the two possible mechanisms, political secularism is treated as the dependent variable in a multivariate linear regression model. Independent variables are added to the model in three steps: M1 includes only the socio‐demographics, M2 additionally takes the three facets of religion into account and M3 on top of that also includes tradition and self‐direction.

Findings

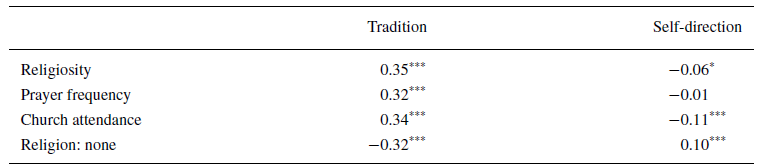

Before turning to political secularism, it is worthwhile to briefly investigate the relationships between religion and the two basic human values. Table 1 shows the results. Although they are each measured only by single items, tradition and self‐direction display correlations in the expected direction with all four indicators. While these are somewhat weaker than those in the meta‐analysis by Saroglou et al. (Reference Saroglou, Delpierre and Dernelle2004), their respective sizes are well within the confidence intervals reported by these authors. This suggests that the data are well‐suited to investigate the relationships between religion, basic human values, and political secularism and points once more to the close association between religion and tradition.

Table 1. Zero‐order correlations between tradition, self‐direction, and four facets of religion

N= 1938–1973. *

![]() $p<0.05$, **

$p<0.05$, **

![]() $p<0.01$, ***

$p<0.01$, ***

![]() $p<0.001$

$p<0.001$

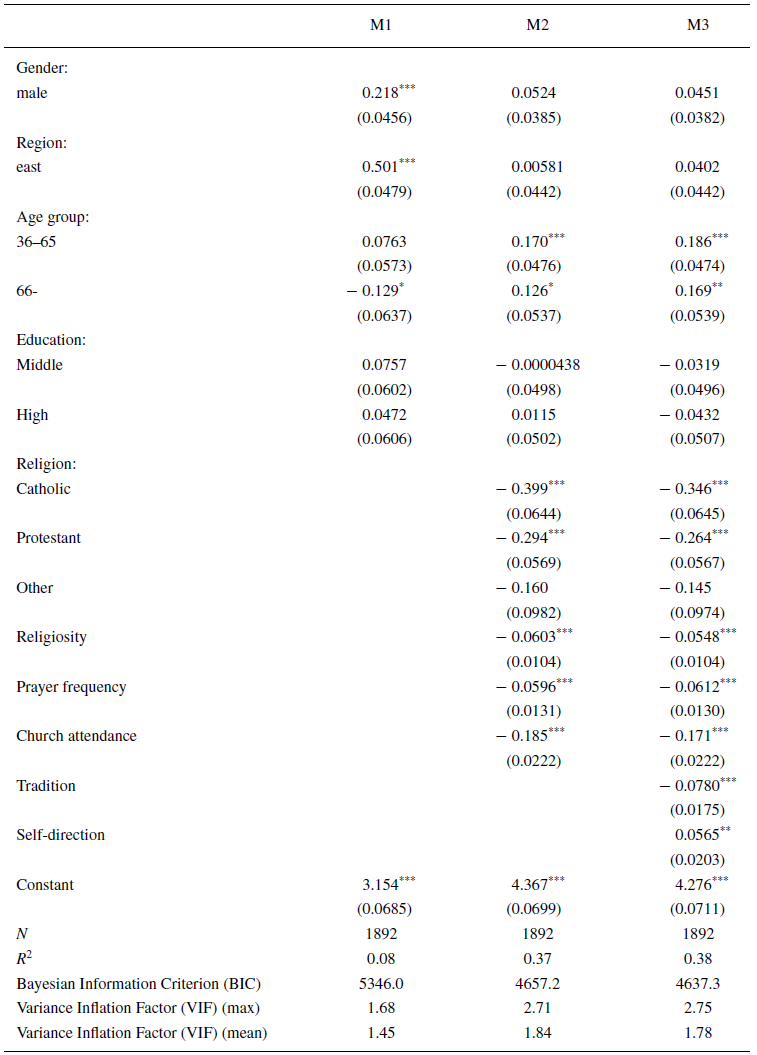

Next, Table 2 shows the estimates for models M1–3. In the first model, the biggest difference between groups is associated with the region. On average, respondents from the eastern states score half a point higher on the secularism scale than their western compatriots. Given the scale's limited range (1–5), this is a very strong effect. Moreover, men are significantly more politically secular than women, and older respondents (above the age of 65) are significantly less secular than both younger and middle‐aged respondents. Education has no discernible effect.

Table 2. Regression of political secularism on religion, basic human values and socio‐demographics

Note: Standard errors in are given in parentheses *

![]() $p<0.05$, **

$p<0.05$, **

![]() $p<0.01$, ***

$p<0.01$, ***

![]() $p<0.001$

$p<0.001$

However, gender, region and age/cohort are all closely associated with religion. Accordingly, the effects of gender and region virtually disappear once the facets of religion are controlled for (M2). This suggests that the role of gender is mediated through women's higher levels of religiosity and that there are no contextual effects on political secularism beyond the lower levels of religion in the East, at least not at this level of aggregation.

Conversely, the effect for the middle‐aged group becomes slightly more pronounced, and the effect for the oldest group changes its sign. While this is unexpected, the pattern has a clear interpretation: older respondents are somewhat more secular than one would expect from their comparatively high levels of religion alone.

The effects of all facets of religion are strong. Mere membership in the EKD is associated with a considerably lower (−0.29) level of political secularism compared to the ‘nones’, and this effect is even stronger for Catholics. Private prayer and self‐assessed religiosity are also associated with significantly lower levels of political secularism. Given the width of their scales and the broad interquartile ranges (4 points for prayer and 6 points for religiosity), this amounts to considerable differences between large segments of the electorate. Finally, the coefficient for church attendance is the biggest. This makes sense, as church attendance brings adherents in direct contact with their organisations, which still claim a political role for themselves. Moreover, church attendance is so rare now (less than 10 per cent of church members attend regularly) that it could be construed as a public statement. However, because of this low attendance rate, the interquartile range is just two scale points (‘never’ and ‘only on special holidays'), which limits the practical relevance of the effect.

Including religion in the model leads to a much better fit: R 2 more than quadruples, and the massive drop in the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) indicates that the increased model complexity is well‐warranted. Although the four indicators for religion correlate (as they should), multicollinearity is not a problem. Both maximal and mean variance inflation factors remain well below the conventional thresholds.

Including tradition and self‐direction in the model (M3) does neither increase multicollinearity nor does it substantially change the estimates for the relationships between political secularism on the one hand and religion and the socio‐demographics on the other hand. Although the model fit improves only marginally, the BIC drops by a further 20 points. Collectively, this suggests that basic human values play an independent role in political secularism.

Both tradition and self‐direction do indeed display the expected effects, thus confirming Hypotheses 1 and 2. While the effects are smaller than those of religion, they are by no means negligible. Going from the lower (−0.20) to the upper (1) quartile of self‐direction would lead to an expected increase of 0.07 points in political secularism. Conversely, moving from the lower (−0.70) to the upper (0.89) quartile of tradition would reduce the expected level of political secularism by 0.12 points. This is roughly half the effect of private prayer. It is also worth pointing out that the negative effect of tradition is in line with the findings by Di Marco et al. (Reference Di Marco, Hichy, Coen and Rodriguez‐Espartal2018), who report a negative effect of conservation (of which tradition is a component).

Conclusion

While scholarly interest in politically secular attitudes has grown recently, relatively little is known about their correlates and antecedents, partly because political secularism (as opposed to the absence of religion) is rarely adequately measured. Making use of data collected in Germany, a typical ‘religious‐world’ country, the analysis presented here shows that political secularism is inversely related to all facets of religion. This has important ramifications. If the generational decline of religion in Europe continues, more and more citizens will not just lose (or never develop an) interest in religion: they will actively oppose the continuing role of churches and other religious groups in political life.

Once religion is controlled for, the differences between men and women, between educational levels, and even between the eastern and the western regions of Germany disappear. However, even when religion is held constant, the basic human values of tradition and self‐direction still exert non‐trivial effects on political secularism. This is important for two reasons. First, it points to another prospective mechanism apart from a decline in religion through which political secularism could spread: while aggregated value preferences within countries are relatively stable over time, a possible future decline of tradition and/or a rise of self‐determination through processes of modernisation would further undermine the political role of religion. Second, and more generally, the findings demonstrate once again the impact of basic human values on all areas of political life.

Acknowledgement

The collection of the data was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), grant number AR 369/5.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest or other ethical issues to report.

Data availability statement

Data and replication scripts are available through the author's dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Z8VYBK.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Data S1