1. Introduction

Throughout this paper, let ![]() $r$ be a large prime. In a recent breakthrough work of Harper [Reference Harper6], it is established that the typical size of the Dirichlet character sum

$r$ be a large prime. In a recent breakthrough work of Harper [Reference Harper6], it is established that the typical size of the Dirichlet character sum  $\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n)$ is

$\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n)$ is ![]() $o(\sqrt{x})$. Precisely, it is proved that if

$o(\sqrt{x})$. Precisely, it is proved that if ![]() $1\leqslant x\leqslant r$ with

$1\leqslant x\leqslant r$ with ![]() $\min(x,r/x)\to \infty$, then

$\min(x,r/x)\to \infty$, then

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{r-1} \sum_{\chi \bmod r} |\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n)| = o(\sqrt{x}),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{r-1} \sum_{\chi \bmod r} |\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n)| = o(\sqrt{x}),

\end{equation} which would imply that for ‘typical ![]() $\chi$’, the character sum is of size

$\chi$’, the character sum is of size ![]() $o(\sqrt{x})$. This somewhat surprising phenomenon was first proved in an earlier beautiful work of Harper [Reference Harper5] in the random model case, namely instead of for a character

$o(\sqrt{x})$. This somewhat surprising phenomenon was first proved in an earlier beautiful work of Harper [Reference Harper5] in the random model case, namely instead of for a character ![]() $\chi$, the ‘better than square-root cancellation’ phenomenon holds for a random sum

$\chi$, the ‘better than square-root cancellation’ phenomenon holds for a random sum  $\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} f(n)$, where

$\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} f(n)$, where ![]() $f(n)$ is a random multiplicative function, which can be viewed as a random model for Dirichlet characters. In order to connect the deterministic case to the random multiplicative function model, Harper used a derandomization method.

$f(n)$ is a random multiplicative function, which can be viewed as a random model for Dirichlet characters. In order to connect the deterministic case to the random multiplicative function model, Harper used a derandomization method.

The underlying reason for the ‘better than square-root cancellation’ happening is subtle, which connects to the study of critical multiplicative chaos in probability theory. It is also believed that such a structure is delicate and may easily be destroyed by some perturbation. For example, one can consider general character sums like  $\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} a(n) \chi(n)$ (see [Reference Harper6, Reference Wang and Xu15]) or random sums

$\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} a(n) \chi(n)$ (see [Reference Harper6, Reference Wang and Xu15]) or random sums  $\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} a(n)f(n)$ (see [Reference Gorodetsky and Wong4, Reference Klurman, Shkredov and Xu8, Reference Wang and Xu14]) with a twist

$\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} a(n)f(n)$ (see [Reference Gorodetsky and Wong4, Reference Klurman, Shkredov and Xu8, Reference Wang and Xu14]) with a twist ![]() $a(n)$. It is believed that for some generic coefficients

$a(n)$. It is believed that for some generic coefficients ![]() $a(n)$, such a ‘better than square-root cancellation’ would die out (see [Reference Montgomery and Vaughan9, § 1] for more discussions).

$a(n)$, such a ‘better than square-root cancellation’ would die out (see [Reference Montgomery and Vaughan9, § 1] for more discussions).

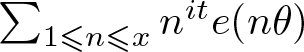

In this paper, we are interested in mixed character sums of the form  $\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta)$, featuring both an additive character

$\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta)$, featuring both an additive character ![]() $e(n\theta)$ and a multiplicative character

$e(n\theta)$ and a multiplicative character ![]() $\chi(n)$.

$\chi(n)$.

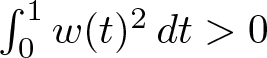

For technical reasons, it is simpler for us to work with a smooth weight ![]() $w\colon\mathbb R\to \mathbb R$. Throughout this paper, fix a smooth function

$w\colon\mathbb R\to \mathbb R$. Throughout this paper, fix a smooth function ![]() $w\colon \mathbb R\to \mathbb R$, supported on

$w\colon \mathbb R\to \mathbb R$, supported on ![]() $[0,1]$, with

$[0,1]$, with  $\int_0^1 w(t)^2\, dt \gt 0$. Note that by partial summation, (1.1) immediately implies

$\int_0^1 w(t)^2\, dt \gt 0$. Note that by partial summation, (1.1) immediately implies

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{r-1} \sum_{\chi \bmod r} |\sum_{n\geqslant 1} \chi(n) w(n/x)| = o(\sqrt{x}).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{r-1} \sum_{\chi \bmod r} |\sum_{n\geqslant 1} \chi(n) w(n/x)| = o(\sqrt{x}).

\end{equation} Similarly, it is also known that for any fixed rational number ![]() $\theta$ we have

$\theta$ we have

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{r-1} \sum_{\chi \bmod r} |\sum_{n\geqslant 1} \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x) | = o(\sqrt{x}).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{r-1} \sum_{\chi \bmod r} |\sum_{n\geqslant 1} \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x) | = o(\sqrt{x}).

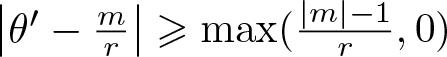

\end{equation} Our main theorem shows that the typical size will be on the square-root size when ![]() $\theta$ is not ‘too close to the rationals’. (The precise condition we impose on

$\theta$ is not ‘too close to the rationals’. (The precise condition we impose on ![]() $\theta$ is (1.4), which is satisfied for most irrational numbers, including

$\theta$ is (1.4), which is satisfied for most irrational numbers, including ![]() $\pi$,

$\pi$, ![]() $e$, and any algebraic irrational

$e$, and any algebraic irrational ![]() $\theta$.)

$\theta$.)

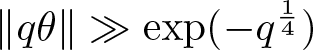

Theorem 1.1 Let ![]() $\theta$ denote an irrational real number such that for some positive constant

$\theta$ denote an irrational real number such that for some positive constant ![]() $C=C(\theta)$ and all

$C=C(\theta)$ and all ![]() $q \in {\mathbb N}$, the following holds:

$q \in {\mathbb N}$, the following holds:

\begin{equation}

\Vert q \theta \Vert := \min_{n\in {\mathbb Z}} |q\theta -n | \geqslant C \exp( - q^{\frac{1}{4}}).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\Vert q \theta \Vert := \min_{n\in {\mathbb Z}} |q\theta -n | \geqslant C \exp( - q^{\frac{1}{4}}).

\end{equation} If ![]() $x$ is sufficiently large (in terms of

$x$ is sufficiently large (in terms of ![]() $w$), then we have for all

$w$), then we have for all ![]() $ x\leqslant r$,

$ x\leqslant r$,

\begin{equation}

\sqrt{x}

\ll \frac{1}{r-1}\sum_{\chi \bmod r} | \sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x)|

\ll \sqrt{x},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sqrt{x}

\ll \frac{1}{r-1}\sum_{\chi \bmod r} | \sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x)|

\ll \sqrt{x},

\end{equation} where the implied constants are allowed to depend on ![]() $\theta$ (and

$\theta$ (and ![]() $w$).

$w$).

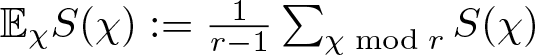

Henceforth, to simplify the notation we let  ${\mathbb E}_{\chi} S(\chi) := \frac{1}{r-1}\sum_{\chi \bmod r} S(\chi)$.

${\mathbb E}_{\chi} S(\chi) := \frac{1}{r-1}\sum_{\chi \bmod r} S(\chi)$.

We give an overview of the proof. The upper bound on the first absolute moment follows easily from the second moment computation together with the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality. Indeed, for ![]() $1\leqslant x\leqslant r$, the orthogonality relation implies that

$1\leqslant x\leqslant r$, the orthogonality relation implies that

\begin{equation}

{\mathbb E}_\chi [|\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x } \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x) |^2]

= \sum_{1\leqslant n\leqslant \min(x,r-1)} w(n/x)^2

\sim x \int_0^1 w(t)^2\, dt \asymp x,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

{\mathbb E}_\chi [|\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x } \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x) |^2]

= \sum_{1\leqslant n\leqslant \min(x,r-1)} w(n/x)^2

\sim x \int_0^1 w(t)^2\, dt \asymp x,

\end{equation} provided that ![]() $x$ is sufficiently large (in terms of

$x$ is sufficiently large (in terms of ![]() $w$).

$w$).

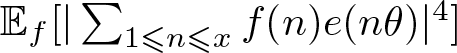

A key feature of our result is that the average size is around ![]() $\sqrt{x}$ uniformly for all

$\sqrt{x}$ uniformly for all ![]() $x\leqslant r$. However, our methods diverge around

$x\leqslant r$. However, our methods diverge around ![]() $x\asymp \sqrt{r}$. In the case

$x\asymp \sqrt{r}$. In the case ![]() $x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$, we show the bound without the weight, that is, for

$x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$, we show the bound without the weight, that is, for ![]() $x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$,

$x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$,

\begin{equation}

{\mathbb E}_\chi[|\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x } \chi(n) e(n\theta)|^{4}] \ll x^{2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

{\mathbb E}_\chi[|\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x } \chi(n) e(n\theta)|^{4}] \ll x^{2}.

\end{equation}By using partial summation, this would imply

\begin{equation}

{\mathbb E}_\chi[|\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x } \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x)|^{4}] \ll x^{2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

{\mathbb E}_\chi[|\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x } \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(n/x)|^{4}] \ll x^{2}.

\end{equation}An application of Hölder’s inequality together with (1.6) and (1.8) establishes the lower bound on the first absolute moment. By using the orthogonality, the fourth moment of the mixed character sum in (1.7) is the same as

\begin{equation}

\sum_{\substack{m_1m_2 \equiv n_1n_2 \bmod r \\ m_i, n_i \leqslant x}} e((m_1+m_2- n_1-n_2)\theta).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sum_{\substack{m_1m_2 \equiv n_1n_2 \bmod r \\ m_i, n_i \leqslant x}} e((m_1+m_2- n_1-n_2)\theta).

\end{equation} The congruence condition is irrelevant if ![]() $x$ is small enough compared with

$x$ is small enough compared with ![]() $r$. In the above equation (1.9) when

$r$. In the above equation (1.9) when ![]() $x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$, the ‘

$x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$, the ‘![]() $\equiv$’ is the same as the ‘

$\equiv$’ is the same as the ‘![]() $=$’. One may view the

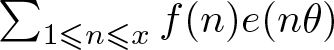

$=$’. One may view the ![]() $\chi(\cdot)$ as a random variable distributed on the unit circle. Indeed, the fourth moment above is the same as

$\chi(\cdot)$ as a random variable distributed on the unit circle. Indeed, the fourth moment above is the same as  $ {\mathbb E}_{f} [ | \sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} f(n) e(n\theta)|^{4}] $ where

$ {\mathbb E}_{f} [ | \sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} f(n) e(n\theta)|^{4}] $ where ![]() $f$ is a Steinhaus random multiplicative function. The parallel result for the random multiplicative function is known. It is proved that [Reference Wang and Xu14] for the family of

$f$ is a Steinhaus random multiplicative function. The parallel result for the random multiplicative function is known. It is proved that [Reference Wang and Xu14] for the family of ![]() $\theta$ satisfying a certain weak Diophantine condition (but stronger than our requirement in Theorem 1.1), the quantity

$\theta$ satisfying a certain weak Diophantine condition (but stronger than our requirement in Theorem 1.1), the quantity  $\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} f(n) e(n\theta)$ behaves Gaussian with variance

$\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} f(n) e(n\theta)$ behaves Gaussian with variance ![]() $x$, which as a consequence, shows that its typical size is

$x$, which as a consequence, shows that its typical size is ![]() $\sqrt{x}$. An earlier result [Reference Benatar, Nishry and Rodgers1] proved this for almost all

$\sqrt{x}$. An earlier result [Reference Benatar, Nishry and Rodgers1] proved this for almost all ![]() $\theta$ by using the method of moments. We will employ the methods in [Reference Wang and Xu14] to deduce our result in the

$\theta$ by using the method of moments. We will employ the methods in [Reference Wang and Xu14] to deduce our result in the ![]() $x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$ range in Section 2.

$x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$ range in Section 2.

The bulk of the paper focuses on the case ![]() $x\geqslant \sqrt{r}$. In this case, we do not directly compute the fourth moment. Instead, we do a Poisson summation first to study a dual problem, with

$x\geqslant \sqrt{r}$. In this case, we do not directly compute the fourth moment. Instead, we do a Poisson summation first to study a dual problem, with ![]() $r/x$ replacing

$r/x$ replacing ![]() $x$. This completes the sum over

$x$. This completes the sum over ![]() $n$ modulo

$n$ modulo ![]() $r$, leading to a new problem involving Diophantine approximation and congruences. Recently, Heap and Sahay [Reference Heap and Sahay7] also analyzed Diophantine approximations, in a different way, when bounding the fourth moment of the Hurwitz zeta function. Their work is closely tied to partial sums of the form

$r$, leading to a new problem involving Diophantine approximation and congruences. Recently, Heap and Sahay [Reference Heap and Sahay7] also analyzed Diophantine approximations, in a different way, when bounding the fourth moment of the Hurwitz zeta function. Their work is closely tied to partial sums of the form  $\sum_{1\leqslant n\leqslant x} n^{it} e(n\theta)$, featuring

$\sum_{1\leqslant n\leqslant x} n^{it} e(n\theta)$, featuring ![]() $n^{it}$ rather than

$n^{it}$ rather than ![]() $\chi(n)$.

$\chi(n)$.

Remark. A restriction like ![]() $x\leqslant r$ is necessary in Theorem 1.1. For instance, if

$x\leqslant r$ is necessary in Theorem 1.1. For instance, if ![]() $x\equiv 0\bmod{r}$, then

$x\equiv 0\bmod{r}$, then

\begin{equation*}

{\mathbb E}_{\chi} \left\vert{\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta)}\right\vert

= \frac{\left\vert{1-e((x-r)\theta)}\right\vert}{\left\vert{1-e(r\theta)}\right\vert}

{\mathbb E}_{\chi} \left\vert{\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant r} \chi(n) e(n\theta)}\right\vert

\ll \frac{1}{\left\vert{1-e(r\theta)}\right\vert} \sqrt{r},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

{\mathbb E}_{\chi} \left\vert{\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta)}\right\vert

= \frac{\left\vert{1-e((x-r)\theta)}\right\vert}{\left\vert{1-e(r\theta)}\right\vert}

{\mathbb E}_{\chi} \left\vert{\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant r} \chi(n) e(n\theta)}\right\vert

\ll \frac{1}{\left\vert{1-e(r\theta)}\right\vert} \sqrt{r},

\end{equation*} by the easy (![]() $\ll$) direction of (1.5). But if

$\ll$) direction of (1.5). But if ![]() $x/r\to \infty$, then for infinitely many primes

$x/r\to \infty$, then for infinitely many primes ![]() $r$ the right-hand side is

$r$ the right-hand side is ![]() $\ll \sqrt{r}$, not

$\ll \sqrt{r}$, not ![]() $\asymp \sqrt{x}$.

$\asymp \sqrt{x}$.

For instance, if ![]() $c\geqslant 2$ such that

$c\geqslant 2$ such that ![]() $p_n+c$ is prime for infinitely many primes

$p_n+c$ is prime for infinitely many primes ![]() $p_n$, then for some

$p_n$, then for some ![]() $r_n \in \{p_n,p_n+c\}$, we have, by the triangle inequality

$r_n \in \{p_n,p_n+c\}$, we have, by the triangle inequality

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\left\vert{1-e(r_n\theta)}\right\vert

&= \max(\left\vert{1-e(p_n\theta)}\right\vert, \left\vert{1-e((p_n+c)\theta)}\right\vert) \\

&\gg \left\vert{e(p_n\theta)-e((p_n+c)\theta)}\right\vert

= \left\vert{1-e(c\theta)}\right\vert

\gg_\theta 1.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\left\vert{1-e(r_n\theta)}\right\vert

&= \max(\left\vert{1-e(p_n\theta)}\right\vert, \left\vert{1-e((p_n+c)\theta)}\right\vert) \\

&\gg \left\vert{e(p_n\theta)-e((p_n+c)\theta)}\right\vert

= \left\vert{1-e(c\theta)}\right\vert

\gg_\theta 1.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} Our main result concerns the size of the mixed character sums for the large range where the two key parameters satisfy ![]() $x\leqslant r$. It would be nice if one could determine the distribution. In particular, we raise the following question.

$x\leqslant r$. It would be nice if one could determine the distribution. In particular, we raise the following question.

Question 1.3. For which ranges of parameters ![]() $x,r\to +\infty$ is it true that as

$x,r\to +\infty$ is it true that as ![]() $\chi$ varies uniformly over the family of Dirichlet characters mod

$\chi$ varies uniformly over the family of Dirichlet characters mod ![]() $r$, we have

$r$, we have

\begin{equation*}

\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(\sqrt{2}n) \xrightarrow{d} \mathcal{CN}(0,1)?

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant x} \chi(n) e(\sqrt{2}n) \xrightarrow{d} \mathcal{CN}(0,1)?

\end{equation*} In the above notation, ![]() $\mathcal{CN}(0,1)$ denotes standard complex Gaussian distribution. One may also ask about any

$\mathcal{CN}(0,1)$ denotes standard complex Gaussian distribution. One may also ask about any ![]() $\theta$ that is not ‘close to’ rationals; we put

$\theta$ that is not ‘close to’ rationals; we put ![]() $\theta=\sqrt{2}$ for concreteness. Originally, we conjectured that Question 1.3 should have an affirmative answer for all

$\theta=\sqrt{2}$ for concreteness. Originally, we conjectured that Question 1.3 should have an affirmative answer for all ![]() $1\leqslant x\leqslant r$. However, very recent work of Bober, Klurman, and Shala [Reference Bober, Klurman and Shala2] shows, in particular, that Question 1.3 in fact has a negative answer for

$1\leqslant x\leqslant r$. However, very recent work of Bober, Klurman, and Shala [Reference Bober, Klurman and Shala2] shows, in particular, that Question 1.3 in fact has a negative answer for ![]() $x=r$.

$x=r$.

To attack Question 1.3, starting with the method of moments is natural. For ![]() $x\leqslant r^{\epsilon}$, we have perfect orthogonality even for high moments computation, and the problem is essentially the same as replacing

$x\leqslant r^{\epsilon}$, we have perfect orthogonality even for high moments computation, and the problem is essentially the same as replacing ![]() $\chi$ with a random multiplicative function. This might be doable; for example, we refer the readers to [Reference Soundararajan and Xu13, Reference Xu16] for high moments computation on related problems. It would be even more interesting to determine the limiting distribution for the full range

$\chi$ with a random multiplicative function. This might be doable; for example, we refer the readers to [Reference Soundararajan and Xu13, Reference Xu16] for high moments computation on related problems. It would be even more interesting to determine the limiting distribution for the full range ![]() $x\leqslant r$, for which the periodicity modulo

$x\leqslant r$, for which the periodicity modulo ![]() $r$ can no longer be ignored.

$r$ can no longer be ignored.

There has been a line of nice work on studying the character sums with additive twists without averaging over characters, and we refer readers to [Reference de la Bretèche and Granville3, Reference Montgomery and Vaughan10] and references therein. We also mention that there is the dual direction of the problem, where one can average over ![]() $\theta$ but fix a multiplicative function, e.g. the Liouville function

$\theta$ but fix a multiplicative function, e.g. the Liouville function ![]() $\lambda(n)$ (see [Reference Pandey, Wang and Xu12] for the most recent development and reference therein).

$\lambda(n)$ (see [Reference Pandey, Wang and Xu12] for the most recent development and reference therein).

2. Short sum case

In this section, we prove the lower bound in Theorem 1.1 in the case ![]() $x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$. As discussed in the introduction, it suffices to prove an upper bound as in (1.7). Expanding the fourth moment and noticing the perfect orthogonality (thanks to

$x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$. As discussed in the introduction, it suffices to prove an upper bound as in (1.7). Expanding the fourth moment and noticing the perfect orthogonality (thanks to ![]() $x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$), it is sufficient to show the following proposition.

$x\leqslant \sqrt{r}$), it is sufficient to show the following proposition.

Proposition 2.1. Let ![]() $\theta$ satisfy the Diophantine condition (1.4). Let

$\theta$ satisfy the Diophantine condition (1.4). Let ![]() $x$ be large. Then

$x$ be large. Then

\begin{equation}

\Big| \sum_{\substack{1\leqslant m_1, m_2, n_1, n_2 \leqslant x \\ m_1 m_2= n_1 n_2 \\ \{m_1, n_1\} \neq \{m_2, n_2\} }} e((m_1+m_2- n_1-n_2)\theta) \Big| =o (x^{2}).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\Big| \sum_{\substack{1\leqslant m_1, m_2, n_1, n_2 \leqslant x \\ m_1 m_2= n_1 n_2 \\ \{m_1, n_1\} \neq \{m_2, n_2\} }} e((m_1+m_2- n_1-n_2)\theta) \Big| =o (x^{2}).

\end{equation}The proof of the Proposition closely follows the proof of [Reference Wang and Xu14, Theorem 1.6, Theorem 3.1]. Our situation is simpler, and we give a proof here for completeness. We remark that the main difference is that the exponential sum in [Reference Wang and Xu14] has multiplicative coefficients, which requires a result of Montgomery–Vaughan [Reference Pandey and Radziwiłł11]. Instead, we use the following simple estimate, which leads to the weaker Diophantine condition (1.4) and thus a better quantitative result.

A simple starting point is that

\begin{equation}

\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant y} e(n\alpha) = \frac{e(\alpha)(1-e(y\alpha))}{1-e(\alpha)} \ll \min \{y, \frac{1}{\|\alpha\|}\}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sum_{1\leqslant n \leqslant y} e(n\alpha) = \frac{e(\alpha)(1-e(y\alpha))}{1-e(\alpha)} \ll \min \{y, \frac{1}{\|\alpha\|}\}.

\end{equation}Proof of Proposition 2.1

We use the same parametrization as in [Reference Wang and Xu14], to write ![]() $m_1=ga$,

$m_1=ga$, ![]() $m_2 =hb$,

$m_2 =hb$, ![]() $n_1= gb$ and

$n_1= gb$ and ![]() $n_2=ha$. The constraints on

$n_2=ha$. The constraints on ![]() $m_1$,

$m_1$, ![]() $m_2$,

$m_2$, ![]() $n_1$,

$n_1$, ![]() $n_2$ then become

$n_2$ then become ![]() $(a,b)=1$ with

$(a,b)=1$ with ![]() $a\neq b$,

$a\neq b$, ![]() $g\neq h$, and

$g\neq h$, and ![]() $\max(a,b) \times \max(g,h)\leqslant x$. Thus the sum we wish to bound becomes

$\max(a,b) \times \max(g,h)\leqslant x$. Thus the sum we wish to bound becomes

\begin{equation}

\sum_{\substack{\max (a,b ) \times \max(g, h) \leqslant x \\ a\neq b, \ (a,b)=1 \\g\neq h}} e((g-h)(a-b) \theta).

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sum_{\substack{\max (a,b ) \times \max(g, h) \leqslant x \\ a\neq b, \ (a,b)=1 \\g\neq h}} e((g-h)(a-b) \theta).

\end{equation} Since ![]() $\max(a,b) \times \max(g,h) \leqslant x$, we may break the sum above into the cases (1) when

$\max(a,b) \times \max(g,h) \leqslant x$, we may break the sum above into the cases (1) when ![]() $\max(g,h) \leqslant \sqrt{x}$, (2) when

$\max(g,h) \leqslant \sqrt{x}$, (2) when ![]() $\max(a,b )\leqslant \sqrt{x}$, taking care to subtract the terms satisfying (3)

$\max(a,b )\leqslant \sqrt{x}$, taking care to subtract the terms satisfying (3) ![]() $\max(a,b)$ and

$\max(a,b)$ and ![]() $\max(g,h)$ both below

$\max(g,h)$ both below ![]() $\sqrt{x}$.

$\sqrt{x}$.

Before turning to these cases, we record a preliminary lemma which will be useful in our analysis.

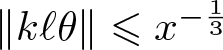

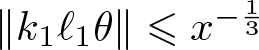

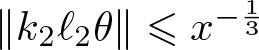

Lemma 2.2. Let ![]() $\theta$ be an irrational number satisfying the Diophantine condition (1.4). Let

$\theta$ be an irrational number satisfying the Diophantine condition (1.4). Let ![]() ${\mathcal L} = {\mathcal L}(x)$ denote the set of all integers

${\mathcal L} = {\mathcal L}(x)$ denote the set of all integers ![]() $\ell$ with

$\ell$ with ![]() $|\ell| \leqslant \sqrt{x}$ such that for some

$|\ell| \leqslant \sqrt{x}$ such that for some ![]() $k \leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon}$ one has

$k \leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon}$ one has  $\Vert k\ell \theta \Vert \leqslant x^{-\frac 13}$, where

$\Vert k\ell \theta \Vert \leqslant x^{-\frac 13}$, where ![]() $\epsilon \gt 0$ is small. Then

$\epsilon \gt 0$ is small. Then ![]() $0$ is in

$0$ is in ![]() ${\mathcal L}$, and for any two distinct elements

${\mathcal L}$, and for any two distinct elements ![]() $\ell_1$,

$\ell_1$, ![]() $\ell_2 \in {\mathcal L}$ we have

$\ell_2 \in {\mathcal L}$ we have ![]() $|\ell_1 - \ell_2| \gg (\log x)^{3/2}$.

$|\ell_1 - \ell_2| \gg (\log x)^{3/2}$.

Proof. Evidently ![]() $0$ is in

$0$ is in ![]() ${\mathcal L}$, and the main point is the spacing condition satisfied by elements of

${\mathcal L}$, and the main point is the spacing condition satisfied by elements of ![]() ${\mathcal L}$. If

${\mathcal L}$. If ![]() $\ell_1$ and

$\ell_1$ and ![]() $\ell_2$ are distinct elements of

$\ell_2$ are distinct elements of ![]() ${\mathcal L}$ then there exist

${\mathcal L}$ then there exist ![]() $k_1$,

$k_1$, ![]() $k_2 \leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon}$ with

$k_2 \leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon}$ with  $\Vert k_1 \ell_1 \theta\Vert \leqslant x^{-\frac 13}$ and

$\Vert k_1 \ell_1 \theta\Vert \leqslant x^{-\frac 13}$ and  $\Vert k_2 \ell_2 \theta \Vert \leqslant x^{-\frac 13}$. It follows that

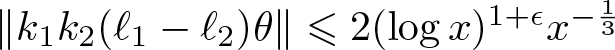

$\Vert k_2 \ell_2 \theta \Vert \leqslant x^{-\frac 13}$. It follows that  $\Vert k_1 k_2 (\ell_1 -\ell_2) \theta\Vert \leqslant 2(\log x)^{1+\epsilon} x^{-\frac 13}$. The desired bound on

$\Vert k_1 k_2 (\ell_1 -\ell_2) \theta\Vert \leqslant 2(\log x)^{1+\epsilon} x^{-\frac 13}$. The desired bound on ![]() $|\ell_1 -\ell_2|$ now follows from the Diophantine property that we required of

$|\ell_1 -\ell_2|$ now follows from the Diophantine property that we required of ![]() $\theta$, namely that

$\theta$, namely that  $\Vert q\theta \Vert \gg \exp(-q^{\frac 1{4}})$ which implies that

$\Vert q\theta \Vert \gg \exp(-q^{\frac 1{4}})$ which implies that ![]() $(\log x )^{4} \ll k_1 k_2 |\ell_1-\ell_2|$ and the desired estimate follows.

$(\log x )^{4} \ll k_1 k_2 |\ell_1-\ell_2|$ and the desired estimate follows.

Case 1: ![]() $\max (g, h )\leqslant \sqrt{x}$. Suppose that

$\max (g, h )\leqslant \sqrt{x}$. Suppose that ![]() $g$ and

$g$ and ![]() $h$ are given with

$h$ are given with ![]() $g$ and

$g$ and ![]() $h$ below

$h$ below ![]() $\sqrt{x}$ and

$\sqrt{x}$ and ![]() $g\neq h$, and consider the sum over

$g\neq h$, and consider the sum over ![]() $a$ and

$a$ and ![]() $b$ in (2.3). We distinguish two sub-cases, depending on whether

$b$ in (2.3). We distinguish two sub-cases, depending on whether ![]() $g-h$ lies in

$g-h$ lies in ![]() ${\mathcal L}$ or not. Consider first the situation when

${\mathcal L}$ or not. Consider first the situation when ![]() $g-h \not\in {\mathcal L}$. Using Möbius inversion to detect the condition that

$g-h \not\in {\mathcal L}$. Using Möbius inversion to detect the condition that ![]() $(a,b)=1$, the sums over

$(a,b)=1$, the sums over ![]() $a$ and

$a$ and ![]() $b$ may be expressed as (the

$b$ may be expressed as (the ![]() $O(1)$ error term accounts for the term

$O(1)$ error term accounts for the term ![]() $a=b=1$ which must be omitted)

$a=b=1$ which must be omitted)

\begin{align}

&\sum_{\substack{k\leqslant x/\max(g, h)\\ }} \mu(k) \sum_{\substack{t, s \leqslant x/(k\max (g,h)) \\ }} e(k(g-h)(t-s)\theta) +O(1)

\nonumber \\

&= \sum_{\substack{k\leqslant x/\max(g, h)\\ }} \mu(k) \Big|\sum_{\substack{t \leqslant x/(k\max (g,h)) \\ }} e(k(g-h)t\theta)\Big|^2 +O(1).\end{align}

\begin{align}

&\sum_{\substack{k\leqslant x/\max(g, h)\\ }} \mu(k) \sum_{\substack{t, s \leqslant x/(k\max (g,h)) \\ }} e(k(g-h)(t-s)\theta) +O(1)

\nonumber \\

&= \sum_{\substack{k\leqslant x/\max(g, h)\\ }} \mu(k) \Big|\sum_{\substack{t \leqslant x/(k\max (g,h)) \\ }} e(k(g-h)t\theta)\Big|^2 +O(1).\end{align} If ![]() $k \gt (\log x)^{1+\epsilon}$ then we bound the sum over

$k \gt (\log x)^{1+\epsilon}$ then we bound the sum over ![]() $t$ above by

$t$ above by ![]() $x/(k\max(g,h))$, and so these terms contribute to (2.4) an amount

$x/(k\max(g,h))$, and so these terms contribute to (2.4) an amount

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{k \gt (\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}} \frac{x^2}{k^2 \max(g,h)^2} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2} \max (g, h)^2}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{k \gt (\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}} \frac{x^2}{k^2 \max(g,h)^2} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2} \max (g, h)^2}.

\end{equation*} Now consider ![]() $k\leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}$. Since

$k\leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}$. Since ![]() $g-h \not \in {\mathcal L}$ by assumption, it follows that

$g-h \not \in {\mathcal L}$ by assumption, it follows that ![]() $\Vert k(g-h) \theta \Vert \gt x^{-1/3} $. An application of (2.2) shows that the sum over

$\Vert k(g-h) \theta \Vert \gt x^{-1/3} $. An application of (2.2) shows that the sum over ![]() $t$ in (2.4) is

$t$ in (2.4) is ![]() $\leqslant x^{1/3}$. Thus the terms

$\leqslant x^{1/3}$. Thus the terms ![]() $k \leqslant(\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}$ contribute to (2.4) an amount bounded by

$k \leqslant(\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}$ contribute to (2.4) an amount bounded by

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{k\leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}}x^{2/3} = O(x^{2/3 + \epsilon}).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{k\leqslant (\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2}}x^{2/3} = O(x^{2/3 + \epsilon}).

\end{equation*} Summing this overall ![]() $g$,

$g$, ![]() $h \leqslant \sqrt{x}$, we conclude that the contribution of terms with

$h \leqslant \sqrt{x}$, we conclude that the contribution of terms with ![]() $\max(g,h)\leqslant \sqrt{x}$ and

$\max(g,h)\leqslant \sqrt{x}$ and ![]() $g-h \not\in {\mathcal L}$ to (2.3) is

$g-h \not\in {\mathcal L}$ to (2.3) is

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{g, h \leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2} \max(g,h)^2} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{\epsilon}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{g, h \leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1+\epsilon/2} \max(g,h)^2} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{\epsilon}}.

\end{equation*} Now consider the contribution of the terms ![]() $\max(g,h)\leqslant \sqrt{x}$ where

$\max(g,h)\leqslant \sqrt{x}$ where ![]() $g-h$ lies in

$g-h$ lies in ![]() ${\mathcal L}$ with

${\mathcal L}$ with ![]() $g-h \neq 0$. Bounding the sum over

$g-h \neq 0$. Bounding the sum over ![]() $a$ and

$a$ and ![]() $b$ trivially by

$b$ trivially by ![]() $\leqslant (x/\max(g,h))^2$, we see that the contribution of these terms is

$\leqslant (x/\max(g,h))^2$, we see that the contribution of these terms is

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{\substack{g \neq h \leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ g- h \in {\mathcal L}}} \frac{x^2}{\max(g,h)^2} \ll \sum_{g\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{g^2} \sum_{\substack{h \lt g\\ g-h \in {\mathcal L}}} 1

\ll \sum_{g\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{g^2} \frac{g}{(\log x)^{3/2}} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1/2}},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{\substack{g \neq h \leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ g- h \in {\mathcal L}}} \frac{x^2}{\max(g,h)^2} \ll \sum_{g\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{g^2} \sum_{\substack{h \lt g\\ g-h \in {\mathcal L}}} 1

\ll \sum_{g\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{g^2} \frac{g}{(\log x)^{3/2}} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1/2}},

\end{equation*} where we used Lemma 2.2 to bound the sum over ![]() $h$.

$h$.

We conclude that the contribution of terms with ![]() $\max(g,h)\leqslant \sqrt{x}$ to (2.3) is

$\max(g,h)\leqslant \sqrt{x}$ to (2.3) is ![]() $\ll x^2/(\log x)^{1/2}$, completing our discussion of this case.

$\ll x^2/(\log x)^{1/2}$, completing our discussion of this case.

Case 2: ![]() $\max\{a, b\}\leqslant \sqrt{x}$. We first consider the contribution in the case that

$\max\{a, b\}\leqslant \sqrt{x}$. We first consider the contribution in the case that ![]() $g=h$. Then the contribution in this case is

$g=h$. Then the contribution in this case is

\begin{equation}

\ll \sum_{a, b\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \sum_{g \leqslant x/\max\{a, b\}}1 \ll x^{3/2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\ll \sum_{a, b\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \sum_{g \leqslant x/\max\{a, b\}}1 \ll x^{3/2}.

\end{equation} From now on, we allow ![]() $g=h$, and thus we must bound

$g=h$, and thus we must bound

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{a\neq b \leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ (a, b)=1}} \Big| \sum_{\substack{g\leqslant x/\max(a,b) \\ } } e(g(a-b)\theta)\Big|^2.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{a\neq b \leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ (a, b)=1}} \Big| \sum_{\substack{g\leqslant x/\max(a,b) \\ } } e(g(a-b)\theta)\Big|^2.

\end{equation*} Again we distinguish the cases when ![]() $a-b\in{\mathcal L}$, and when

$a-b\in{\mathcal L}$, and when ![]() $a-b \not \in {\mathcal L}$. In the first case, we bound the sum over

$a-b \not \in {\mathcal L}$. In the first case, we bound the sum over ![]() $g$ above trivially by

$g$ above trivially by ![]() $\leqslant x/\max(a,b)$, and thus these terms contribute (using Lemma 2.2)

$\leqslant x/\max(a,b)$, and thus these terms contribute (using Lemma 2.2)

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{a\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{a^2} \sum_{\substack{b \lt a \\ a-b\in {\mathcal L}}} 1 \ll \sum_{a\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{a^2} \frac{a}{(\log x)^{3/2}} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1/2}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{a\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{a^2} \sum_{\substack{b \lt a \\ a-b\in {\mathcal L}}} 1 \ll \sum_{a\leqslant \sqrt{x}} \frac{x^2}{a^2} \frac{a}{(\log x)^{3/2}} \ll \frac{x^2}{(\log x)^{1/2}}.

\end{equation*} Now consider the case when ![]() $a-b\not\in {\mathcal L}$. Again, since

$a-b\not\in {\mathcal L}$. Again, since ![]() $a-b\not \in {\mathcal L}$, it follows that

$a-b\not \in {\mathcal L}$, it follows that ![]() $\Vert (a-b)\theta \Vert \gt x^{-1/3}$ and an application of (2.2) gives

$\Vert (a-b)\theta \Vert \gt x^{-1/3}$ and an application of (2.2) gives

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{g\leqslant x/\max(a,b) \\ }} e(g(a-b)\theta) \ll x^{1/3}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{g\leqslant x/\max(a,b) \\ }} e(g(a-b)\theta) \ll x^{1/3}.

\end{equation*} Thus the contribution of the terms with ![]() $a-b\not \in {\mathcal L}$ is

$a-b\not \in {\mathcal L}$ is

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{a, b\leqslant \sqrt{x}} x^{2/3} \ll x^{5/3}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\ll \sum_{a, b\leqslant \sqrt{x}} x^{2/3} \ll x^{5/3}.

\end{equation*} Thus the contribution to (2.3) from the Case 2 terms is ![]() $\ll x^2/(\log x)^{1/2}$.

$\ll x^2/(\log x)^{1/2}$.

Case 3: ![]() $\max(a,b)$ and

$\max(a,b)$ and ![]() $\max(g,h) \leqslant \sqrt{x}$. Similarly, we first bound the contribution from the case

$\max(g,h) \leqslant \sqrt{x}$. Similarly, we first bound the contribution from the case ![]() $g=h$ as in (2.5). From now on, we allow

$g=h$ as in (2.5). From now on, we allow ![]() $g=h$, and thus we must bound

$g=h$, and thus we must bound

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{a\neq b \leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ (a, b)=1}} \Big| \sum_{\substack{g\leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ } } e(g(a-b)\theta)\Big|^2,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{a\neq b \leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ (a, b)=1}} \Big| \sum_{\substack{g\leqslant \sqrt{x} \\ } } e(g(a-b)\theta)\Big|^2,

\end{equation*} and our argument in Case 2 above furnishes the bound ![]() $\ll x^2/(\log x)^{1/2}$.

$\ll x^2/(\log x)^{1/2}$.

3. Reduction to a counting problem

In this section, we consider the case ![]() $\sqrt{r}\leqslant x \leqslant r$ and reduce (1.8) to a counting problem for a quadratic Diophantine equation involving a pair of integers

$\sqrt{r}\leqslant x \leqslant r$ and reduce (1.8) to a counting problem for a quadratic Diophantine equation involving a pair of integers ![]() $(k, r)$ with

$(k, r)$ with  $\theta \approx \frac{k}{r}$. In the next section, we will use the pigeonhole principle to show that this equation does not have too many solutions, provided the Diophantine condition (1.4) holds.

$\theta \approx \frac{k}{r}$. In the next section, we will use the pigeonhole principle to show that this equation does not have too many solutions, provided the Diophantine condition (1.4) holds.

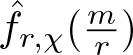

The starting point is to apply the Poisson summation formula to flip the character summation in (1.8) from ‘up to ![]() $x$’ to ‘up to

$x$’ to ‘up to ![]() $r/x$’. Let

$r/x$’. Let ![]() $k=\rfloor{r\theta}$. Write

$k=\rfloor{r\theta}$. Write ![]() $\theta = k/r + \theta'$ where

$\theta = k/r + \theta'$ where ![]() $0\leqslant \theta' \lt 1/r$. This is a pragmatic rational approximation of

$0\leqslant \theta' \lt 1/r$. This is a pragmatic rational approximation of ![]() $\theta$ that will prevent an increase in the ‘conductor’

$\theta$ that will prevent an increase in the ‘conductor’ ![]() $r$ for the problem at hand. We define

$r$ for the problem at hand. We define

\begin{equation*}f_{r,\chi}(n):= \chi(n)e(\frac{kn}{r}),

\quad f_{\infty}(n) := w(\frac{n}{x}) e(n\theta'). \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}f_{r,\chi}(n):= \chi(n)e(\frac{kn}{r}),

\quad f_{\infty}(n) := w(\frac{n}{x}) e(n\theta'). \end{equation*} Then since ![]() $w(n/x) = 0$ for all integers

$w(n/x) = 0$ for all integers ![]() $n\leqslant 0$ and

$n\leqslant 0$ and ![]() $n\geqslant x$, we have

$n\geqslant x$, we have

\begin{equation}

\sum_{1\leqslant n\leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(\frac{n}{x})

= \sum_{n\in \mathbb Z} f_{r,\chi}(n)f_{\infty}(n)

= \sum_{m\in \mathbb Z} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sum_{1\leqslant n\leqslant x} \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(\frac{n}{x})

= \sum_{n\in \mathbb Z} f_{r,\chi}(n)f_{\infty}(n)

= \sum_{m\in \mathbb Z} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\end{equation} by Poisson summation in ![]() $(\mathbb Z/r\mathbb Z) \times \mathbb R$, where

$(\mathbb Z/r\mathbb Z) \times \mathbb R$, where

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) = \frac{1}{r}\sum_{t\in \mathbb Z/r\mathbb Z}\chi(t) e\left(\frac{(k+m)t}{r}\right) \end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) = \frac{1}{r}\sum_{t\in \mathbb Z/r\mathbb Z}\chi(t) e\left(\frac{(k+m)t}{r}\right) \end{equation*}and

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r}) = \int_{\mathbb R} w(\frac{t}{x}) e( (\theta'-\frac{m}{r})t ) dt. \end{equation*}

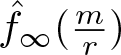

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r}) = \int_{\mathbb R} w(\frac{t}{x}) e( (\theta'-\frac{m}{r})t ) dt. \end{equation*} We now estimate the Fourier coefficients  $\hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r})$ and

$\hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r})$ and  $\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})$. For a fixed

$\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})$. For a fixed ![]() $m$, if

$m$, if ![]() $k+m \not\equiv 0 \bmod{r}$ then by applying standard properties of Gauss sums,

$k+m \not\equiv 0 \bmod{r}$ then by applying standard properties of Gauss sums,

\begin{equation}

\hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) = \chi(k+m)^{-1} \frac{C(\chi)}{r^{1/2}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) = \chi(k+m)^{-1} \frac{C(\chi)}{r^{1/2}},

\end{equation} where ![]() $\left\vert{C(\chi)}\right\vert \leqslant 1$ and

$\left\vert{C(\chi)}\right\vert \leqslant 1$ and ![]() $C(\chi)$ depends only on

$C(\chi)$ depends only on ![]() $\chi$. Next, we turn to

$\chi$. Next, we turn to ![]() $\hat{f}_\infty$.

$\hat{f}_\infty$.

Lemma 3.1. (Fourier bounds)

For all ![]() $A\geqslant 0$ we have

$A\geqslant 0$ we have

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r}) \ll_A x \big(1+\frac{x\max(\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1,0)}{r}\big)^{-A}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r}) \ll_A x \big(1+\frac{x\max(\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1,0)}{r}\big)^{-A}.\end{equation*}Proof. Integrating by parts over ![]() $t$, and recalling that

$t$, and recalling that ![]() $w$ is smooth on

$w$ is smooth on ![]() $\mathbb R$ and supported on

$\mathbb R$ and supported on ![]() $[0,1]$, we get

$[0,1]$, we get

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\ll_B \int_0^x x^{-B} \left\vert{\theta'-\frac{m}{r}}\right\vert^{-B}\, dt\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\ll_B \int_0^x x^{-B} \left\vert{\theta'-\frac{m}{r}}\right\vert^{-B}\, dt\end{equation*} for all ![]() $B\geqslant 0$. Moreover,

$B\geqslant 0$. Moreover,  $\left\vert{\theta'-\frac{m}{r}}\right\vert \geqslant \max(\frac{\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1}{r}, 0)$, since

$\left\vert{\theta'-\frac{m}{r}}\right\vert \geqslant \max(\frac{\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1}{r}, 0)$, since  $\left\vert{\theta'}\right\vert \leqslant \frac1r$. Thus

$\left\vert{\theta'}\right\vert \leqslant \frac1r$. Thus

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\ll_B x \big(x\max(\frac{\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1}{r}, 0)\big)^{-B}.\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\ll_B x \big(x\max(\frac{\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1}{r}, 0)\big)^{-B}.\end{equation*} Optimizing this bound over ![]() $B\in \{0,A\}$ gives the desired result.

$B\in \{0,A\}$ gives the desired result.

We first discuss the pesky terms in (3.1) with ![]() $m\equiv -k\bmod{r}$. We have

$m\equiv -k\bmod{r}$. We have

\begin{equation*}1+\frac{x\max(\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1,0)}{r} \gg \frac{x\max(\left\vert{m}\right\vert,r)}{r}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}1+\frac{x\max(\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1,0)}{r} \gg \frac{x\max(\left\vert{m}\right\vert,r)}{r}\end{equation*} for all ![]() $m\equiv -k\bmod{r}$, because

$m\equiv -k\bmod{r}$, because ![]() $k\sim \theta r$ and we may assume

$k\sim \theta r$ and we may assume ![]() $0 \lt \theta \lt 1$. Therefore,

$0 \lt \theta \lt 1$. Therefore,

\begin{equation}

\sum_{m\equiv -k\bmod{r}} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

= \frac{\boldsymbol{1}_{\chi=\chi_0}}{r-1} \sum_{m\equiv -k\bmod{r}} \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\ll \frac{x^{1-A}}{r-1}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sum_{m\equiv -k\bmod{r}} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

= \frac{\boldsymbol{1}_{\chi=\chi_0}}{r-1} \sum_{m\equiv -k\bmod{r}} \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})

\ll \frac{x^{1-A}}{r-1}

\end{equation} by Lemma 3.1, provided ![]() $A \gt 1$.

$A \gt 1$.

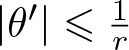

Before expanding the fourth moment of (3.1), we first reduce to the case where the variables all lie in the same range. Write  $\sum_{m\in \mathbb Z} = \sum_{j\geqslant 0} \sum_{m\in I_j}$, where

$\sum_{m\in \mathbb Z} = \sum_{j\geqslant 0} \sum_{m\in I_j}$, where

and

\begin{equation*}I_j = \{\left\vert{m}\right\vert \in (2^{j-1} (2+r/x), 2^j (2+r/x)]\}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}I_j = \{\left\vert{m}\right\vert \in (2^{j-1} (2+r/x), 2^j (2+r/x)]\}\end{equation*} for ![]() $j\geqslant 1$. In view of Lemma 3.1, the ranges

$j\geqslant 1$. In view of Lemma 3.1, the ranges ![]() $j\ll 1$ will morally dominate. Let

$j\ll 1$ will morally dominate. Let ![]() $W_j = 2^{-j\delta}$ for some small

$W_j = 2^{-j\delta}$ for some small ![]() $\delta \gt 0$ to be chosen. Hölder’s inequality over

$\delta \gt 0$ to be chosen. Hölder’s inequality over ![]() $j$ gives the inequality

$j$ gives the inequality

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&\left\vert{\sum_{m\in \mathbb Z} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4 \\

&\ll \!\left\vert{\sum_{m\equiv -k \bmod{r}} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4

\!+\! \mathcal{W} \sum_{j\geqslant 0} W_j^{-3}

\left\vert{\sum_{\substack{m\in I_j \\ m\not\equiv -k \bmod{r}}}\! \frac{\chi(k+m)^{-1}}{r^{1/2}}

\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

&\left\vert{\sum_{m\in \mathbb Z} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4 \\

&\ll \!\left\vert{\sum_{m\equiv -k \bmod{r}} \hat{f}_{r,\chi}(\frac{m}{r}) \hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4

\!+\! \mathcal{W} \sum_{j\geqslant 0} W_j^{-3}

\left\vert{\sum_{\substack{m\in I_j \\ m\not\equiv -k \bmod{r}}}\! \frac{\chi(k+m)^{-1}}{r^{1/2}}

\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4

\end{aligned}

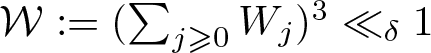

\end{equation} by (3.2), where  $\mathcal{W} := (\sum_{j\geqslant 0} W_j)^3 \ll_\delta 1$. The first term will be negligible by (3.3).

$\mathcal{W} := (\sum_{j\geqslant 0} W_j)^3 \ll_\delta 1$. The first term will be negligible by (3.3).

Let ![]() $T_j:= 2^j(2+r/x)$. In particular, if

$T_j:= 2^j(2+r/x)$. In particular, if ![]() $j\geqslant 1$, then

$j\geqslant 1$, then ![]() $\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1 \asymp T_j$ for all

$\left\vert{m}\right\vert-1 \asymp T_j$ for all ![]() $m\in I_j$. By orthogonality and Lemma 3.1, we have

$m\in I_j$. By orthogonality and Lemma 3.1, we have

\begin{equation*}

{\mathbb E}_\chi

\left\vert{\sum_{\substack{m\in I_j \\ m\not\equiv -k \bmod{r}}} \frac{\chi(k+m)^{-1}}{r^{1/2}}

\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4

\ll

\left(\frac{x}{1 + (T_jx/r)^A \boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}}\right)^4 \frac{1}{r^2} \mathcal{N}_4(I_j),

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

{\mathbb E}_\chi

\left\vert{\sum_{\substack{m\in I_j \\ m\not\equiv -k \bmod{r}}} \frac{\chi(k+m)^{-1}}{r^{1/2}}

\hat{f}_{\infty}(\frac{m}{r})}\right\vert^4

\ll

\left(\frac{x}{1 + (T_jx/r)^A \boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}}\right)^4 \frac{1}{r^2} \mathcal{N}_4(I_j),

\end{equation*} where ![]() $\mathcal{N}_4(I_j)$ is the number of solutions

$\mathcal{N}_4(I_j)$ is the number of solutions ![]() $(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2)\in \{m\in I_j: m\not\equiv -k\bmod{r}\}^4$ to

$(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2)\in \{m\in I_j: m\not\equiv -k\bmod{r}\}^4$ to ![]() $(k+m_1)(k+m_2) \equiv (k+n_1)(k+n_2) \bmod{r}$, or equivalently to

$(k+m_1)(k+m_2) \equiv (k+n_1)(k+n_2) \bmod{r}$, or equivalently to

We write ![]() $S= m_1+m_2-n_1-n_2$ and

$S= m_1+m_2-n_1-n_2$ and ![]() $P= n_1n_2-m_1m_2$. We have

$P= n_1n_2-m_1m_2$. We have ![]() $kS \equiv P \bmod{r}$.

$kS \equiv P \bmod{r}$.

Lemma 3.2. (Injection)

For ![]() $(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2)\in \mathbb Z^4$, let

$(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2)\in \mathbb Z^4$, let

Let ![]() $S,P\in \mathbb Z$. Then

$S,P\in \mathbb Z$. Then ![]() $\Phi$ maps the set

$\Phi$ maps the set ![]() $\mathcal{A}$ injectively into the set

$\mathcal{A}$ injectively into the set ![]() $\mathcal{B}$, where

$\mathcal{B}$, where

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\mathcal{A} &:= \{(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2)\in \mathbb Z^4: m_1+m_2-n_1-n_2=S,\quad n_1n_2-m_1m_2=P\}, \\

\mathcal{B} &:= \{(a,b,c)\in \mathbb Z^3: ab+2cS = S^2-4P\}.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\mathcal{A} &:= \{(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2)\in \mathbb Z^4: m_1+m_2-n_1-n_2=S,\quad n_1n_2-m_1m_2=P\}, \\

\mathcal{B} &:= \{(a,b,c)\in \mathbb Z^3: ab+2cS = S^2-4P\}.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}Proof. Let ![]() $a,b,c$ be the linear forms in

$a,b,c$ be the linear forms in ![]() $m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2$ such that

$m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2$ such that ![]() $\Phi(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2) = (a,b,c)$. Then the following polynomial identity holds:

$\Phi(m_1,m_2,n_1,n_2) = (a,b,c)$. Then the following polynomial identity holds:

Therefore, ![]() $\Phi$ maps

$\Phi$ maps ![]() $\mathcal{A}$ into

$\mathcal{A}$ into ![]() $\mathcal{B}$. Moreover, this map is injective, because the linear forms

$\mathcal{B}$. Moreover, this map is injective, because the linear forms ![]() $a,b,c,S$ are linearly independent over

$a,b,c,S$ are linearly independent over ![]() $\mathbb Q$.

$\mathbb Q$.

4. Point counting

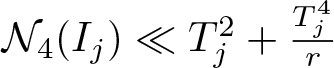

We would like to bound ![]() $\mathcal{N}_4(I_j)$ defined in (3.5). By Lemma 3.2, we have

$\mathcal{N}_4(I_j)$ defined in (3.5). By Lemma 3.2, we have

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{N}_4(I_j)\leqslant

\sum_{\substack{S\ll T_j,\; P\ll T_j^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

N_{S,P}(T_j)

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{N}_4(I_j)\leqslant

\sum_{\substack{S\ll T_j,\; P\ll T_j^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

N_{S,P}(T_j)

\end{equation}where

\begin{equation}

N_{S,P}(T) := \#\{a,b,c\ll T: ab+2cS = S^2-4P\}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

N_{S,P}(T) := \#\{a,b,c\ll T: ab+2cS = S^2-4P\}.

\end{equation} It will follow from Theorem 4.4 that  $\mathcal{N}_4(I_j) \ll T_j^2 + \frac{T_j^4}{r}$.

$\mathcal{N}_4(I_j) \ll T_j^2 + \frac{T_j^4}{r}$.

We note that the equation ![]() $ab+2cS = S^2-4P$ implies that for

$ab+2cS = S^2-4P$ implies that for ![]() $S\ll T$,

$S\ll T$,

Therefore,

\begin{equation*}

N_{S,P}(T)

\leqslant \sum_{a,b\ll T} \boldsymbol{1}_{S\mid ab+4P} \boldsymbol{1}_{ab+4P \ll TS}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

N_{S,P}(T)

\leqslant \sum_{a,b\ll T} \boldsymbol{1}_{S\mid ab+4P} \boldsymbol{1}_{ab+4P \ll TS}.

\end{equation*}Lemma 4.1. Suppose ![]() $1\leqslant u,v\leqslant S\ll T$. Then

$1\leqslant u,v\leqslant S\ll T$. Then

\begin{equation*}\sum_{\substack{a,b\ll T \\ (a,b)\equiv (u,v)\bmod{S}}} \boldsymbol{1}_{ab+4P \ll TS}

\ll \frac{T}{S} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{S}\right).\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\sum_{\substack{a,b\ll T \\ (a,b)\equiv (u,v)\bmod{S}}} \boldsymbol{1}_{ab+4P \ll TS}

\ll \frac{T}{S} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{S}\right).\end{equation*}Proof. There are ![]() $O(1)$ choices for

$O(1)$ choices for ![]() $\left\vert{a}\right\vert\leqslant S$ with

$\left\vert{a}\right\vert\leqslant S$ with ![]() $a\equiv u\bmod{S}$. Thus the total contribution from

$a\equiv u\bmod{S}$. Thus the total contribution from ![]() $\left\vert{a}\right\vert\leqslant S$ is

$\left\vert{a}\right\vert\leqslant S$ is

On the other hand, if ![]() $A\geqslant S$, then there are

$A\geqslant S$, then there are ![]() $O(A/S)$ choices for

$O(A/S)$ choices for ![]() $\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A]$ with

$\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A]$ with ![]() $a\equiv u\bmod{S}$, so the total contribution from the dyadic interval

$a\equiv u\bmod{S}$, so the total contribution from the dyadic interval ![]() $\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A]$ is

$\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A]$ is

\begin{equation*}\ll \sum_{\substack{\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A] \\ a\equiv u\bmod{S}}} \#\{b\equiv v\bmod{S}: ab+4P\ll TS\}

\ll \sum_{\substack{\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A] \\ a\equiv u\bmod{S}}} (1 + \frac{TS}{\left\vert{aS}\right\vert})

\ll \frac{A}{S} (1 + \frac{T}{A}).\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\ll \sum_{\substack{\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A] \\ a\equiv u\bmod{S}}} \#\{b\equiv v\bmod{S}: ab+4P\ll TS\}

\ll \sum_{\substack{\left\vert{a}\right\vert\in (A,2A] \\ a\equiv u\bmod{S}}} (1 + \frac{TS}{\left\vert{aS}\right\vert})

\ll \frac{A}{S} (1 + \frac{T}{A}).\end{equation*} On summing over ![]() $A\in \{1,2,4,8,\ldots\}$ with

$A\in \{1,2,4,8,\ldots\}$ with ![]() $S\leqslant A\ll T$, we get a total bound of

$S\leqslant A\ll T$, we get a total bound of

\begin{equation*}\ll \frac{T}{S} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{S}\right),\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\ll \frac{T}{S} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{S}\right),\end{equation*}as desired.

For any ![]() $S\ll T$ and

$S\ll T$ and ![]() $P\ll T^2$ with

$P\ll T^2$ with ![]() $S\ne 0$, we have

$S\ne 0$, we have

\begin{equation}

N_{S,P}(T)

\leqslant \sum_{a,b\ll T} \boldsymbol{1}_{S\mid ab+4P} \boldsymbol{1}_{ab+4P \ll TS}

\ll \frac{T}{S} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{S}\right) N(-4P,S),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

N_{S,P}(T)

\leqslant \sum_{a,b\ll T} \boldsymbol{1}_{S\mid ab+4P} \boldsymbol{1}_{ab+4P \ll TS}

\ll \frac{T}{S} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{S}\right) N(-4P,S),

\end{equation}by Lemma 4.1, where

Lemma 4.2. (Point counting)

Let ![]() $d,q\in \mathbb Z$ with

$d,q\in \mathbb Z$ with ![]() $q\geqslant 1$. Then

$q\geqslant 1$. Then ![]() $N(d,q)\leqslant \tau(\operatorname{gcd}(d,q)) q$, where

$N(d,q)\leqslant \tau(\operatorname{gcd}(d,q)) q$, where ![]() $\tau(\cdot)$ is the divisor function.

$\tau(\cdot)$ is the divisor function.

Proof. If ![]() $\operatorname{gcd}(q_1,q_2)=1$, then

$\operatorname{gcd}(q_1,q_2)=1$, then ![]() $N(d,q_1q_2) = N(d,q_1)N(d,q_2)$ by the Chinese remainder theorem. Therefore, it suffices to prove the lemma when

$N(d,q_1q_2) = N(d,q_1)N(d,q_2)$ by the Chinese remainder theorem. Therefore, it suffices to prove the lemma when ![]() $q$ is a prime power. Say

$q$ is a prime power. Say ![]() $q = p^t$ and

$q = p^t$ and ![]() $\operatorname{gcd}(d,q) = p^m$. Then clearly

$\operatorname{gcd}(d,q) = p^m$. Then clearly ![]() $t\geqslant m\geqslant 0$. If

$t\geqslant m\geqslant 0$. If ![]() $m=0$, then

$m=0$, then ![]() $N(d,q) = \phi(q) \leqslant q$. If

$N(d,q) = \phi(q) \leqslant q$. If ![]() $m=1$, then

$m=1$, then ![]() $N(d,q) = 2\phi(q) + \boldsymbol{1}_{t=1} \leqslant 2q$. If

$N(d,q) = 2\phi(q) + \boldsymbol{1}_{t=1} \leqslant 2q$. If ![]() $m\geqslant 2$, then

$m\geqslant 2$, then ![]() $N(d,q) = 2\phi(q) + p^2 N(d/p^2,q/p^2)$. By induction on

$N(d,q) = 2\phi(q) + p^2 N(d/p^2,q/p^2)$. By induction on ![]() $m$, it follows that

$m$, it follows that ![]() $N(d,q) \leqslant (m+1)q$, as desired.

$N(d,q) \leqslant (m+1)q$, as desired.

We next count the number of solutions ![]() $(S, P)$ to the equation

$(S, P)$ to the equation ![]() $kS \equiv P \bmod{r}$ by exploring the Diophantine approximation property of

$kS \equiv P \bmod{r}$ by exploring the Diophantine approximation property of ![]() $\theta$.

$\theta$.

Lemma 4.3. (Pigeonhole argument)

Assume ![]() $\left\vert{q\theta-a}\right\vert \gg \Upsilon(q)$ for all

$\left\vert{q\theta-a}\right\vert \gg \Upsilon(q)$ for all ![]() $(a,q)\in \mathbb Z\times \mathbb N$, where

$(a,q)\in \mathbb Z\times \mathbb N$, where ![]() $\Upsilon$ is a decreasing, nonnegative function. For any integer

$\Upsilon$ is a decreasing, nonnegative function. For any integer ![]() $r$, let

$r$, let ![]() $k=\rfloor{r\theta}$. Then for any

$k=\rfloor{r\theta}$. Then for any ![]() $M,N\in \mathbb R$ with

$M,N\in \mathbb R$ with

we have

\begin{equation}

\Upsilon{\left(\frac{N}{\#\{(S,P)\in [1,N]\times [-M,M]: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}}\right)}

\ll \frac{M}{r}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\Upsilon{\left(\frac{N}{\#\{(S,P)\in [1,N]\times [-M,M]: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}}\right)}

\ll \frac{M}{r}.

\end{equation} For example, if ![]() $\Upsilon(q) = \exp(-q^c)$, for some constant

$\Upsilon(q) = \exp(-q^c)$, for some constant ![]() $c \gt 0$, then

$c \gt 0$, then

\begin{equation}

\left(\frac{N}{\#\{(S,P)\in [1,N]\times [-M,M]: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}}\right)^c

\gg \log{\left(\frac{r}{M}\right)} - O(1),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\left(\frac{N}{\#\{(S,P)\in [1,N]\times [-M,M]: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}}\right)^c

\gg \log{\left(\frac{r}{M}\right)} - O(1),

\end{equation}so

\begin{equation}

\#\{S\ll N,\; P\ll M: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}

\ll \frac{N}{(\log(2+r/M))^{1/c}}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\#\{S\ll N,\; P\ll M: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}

\ll \frac{N}{(\log(2+r/M))^{1/c}}.

\end{equation}Proof. By the pigeonhole principle, there exists ![]() $(q,d)\in [1,N]\times [-2M,2M]$ such that

$(q,d)\in [1,N]\times [-2M,2M]$ such that

\begin{equation*}

kq\equiv d\bmod{r},

\qquad

q\leqslant \frac{N}{\#\{(S,P)\in [1,N]\times [-M,M]: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

kq\equiv d\bmod{r},

\qquad

q\leqslant \frac{N}{\#\{(S,P)\in [1,N]\times [-M,M]: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}}.

\end{equation*} For such a pair ![]() $(q,d)$, we have

$(q,d)$, we have ![]() $kq = d+ra$ for some

$kq = d+ra$ for some ![]() $a\in \mathbb Z$. But by definition of

$a\in \mathbb Z$. But by definition of ![]() $k$, we have

$k$, we have ![]() $\left\vert{r\theta-k}\right\vert \lt 1$. Therefore,

$\left\vert{r\theta-k}\right\vert \lt 1$. Therefore,

whence ![]() $\left\vert{q\theta-a}\right\vert \leqslant 3M/r$. Yet by assumption,

$\left\vert{q\theta-a}\right\vert \leqslant 3M/r$. Yet by assumption, ![]() $\left\vert{q\theta-a}\right\vert \gg \Upsilon(q)$. Since

$\left\vert{q\theta-a}\right\vert \gg \Upsilon(q)$. Since ![]() $\Upsilon(q)$ is decreasing, we immediately deduce (4.4). Now (4.5) follows from (4.4). Next, (4.6) follows from (4.5) if

$\Upsilon(q)$ is decreasing, we immediately deduce (4.4). Now (4.5) follows from (4.4). Next, (4.6) follows from (4.5) if ![]() $r/M$ is sufficiently large. On the other hand, (4.6) is trivial if

$r/M$ is sufficiently large. On the other hand, (4.6) is trivial if ![]() $r\ll M$.

$r\ll M$.

Theorem 4.4 Assume ![]() $T\gg 1$ and let

$T\gg 1$ and let ![]() $N_{S, P}(T)$ be defined as in (4.2). Then

$N_{S, P}(T)$ be defined as in (4.2). Then

\begin{equation}

\sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

N_{S,P}(T)

\ll T^2 + \frac{T^4}{r}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

N_{S,P}(T)

\ll T^2 + \frac{T^4}{r}.

\end{equation}Proof. Since ![]() $N_{0,0}(T) \ll T^2$ and

$N_{0,0}(T) \ll T^2$ and ![]() $N_{0,P}(T) \ll T\left\vert{P}\right\vert^\varepsilon$ if

$N_{0,P}(T) \ll T\left\vert{P}\right\vert^\varepsilon$ if ![]() $P\ne 0$, we have

$P\ne 0$, we have

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{P\ll T^2 \\ P \equiv 0 \bmod{r}}}

N_{0,P}(T)

\ll_\varepsilon T^2 + \frac{T^2}{r} T^{1+2\varepsilon}.

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{\substack{P\ll T^2 \\ P \equiv 0 \bmod{r}}}

N_{0,P}(T)

\ll_\varepsilon T^2 + \frac{T^2}{r} T^{1+2\varepsilon}.

\end{equation*} We may henceforth restrict attention to ![]() $S\ne 0$. By (4.3) and Lemma 4.2, we have

$S\ne 0$. By (4.3) and Lemma 4.2, we have

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\heartsuit

:= \sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

N_{S,P}(T)

&\ll \sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

\frac{T}{\left\vert{S}\right\vert} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{S}\right\vert}\right) N(-4P,S) \\

&\ll \sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

T \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{S}\right\vert}\right) \tau(\operatorname{gcd}(P,S)),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\heartsuit

:= \sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

N_{S,P}(T)

&\ll \sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

\frac{T}{\left\vert{S}\right\vert} \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{S}\right\vert}\right) N(-4P,S) \\

&\ll \sum_{\substack{S\ll T,\; P\ll T^2 \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

T \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{S}\right\vert}\right) \tau(\operatorname{gcd}(P,S)),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} where in the last step we use the sub-multiplicativity property ![]() $\tau(mn)\leqslant \tau(m)\tau(n)$ with

$\tau(mn)\leqslant \tau(m)\tau(n)$ with ![]() $m=4$. Upon writing

$m=4$. Upon writing ![]() $(S,P) = (gS',gP')$ with

$(S,P) = (gS',gP')$ with ![]() $g = \operatorname{gcd}(S,P)\geqslant 1$, and summing

$g = \operatorname{gcd}(S,P)\geqslant 1$, and summing ![]() $\tau(g)$ over dyadic intervals

$\tau(g)$ over dyadic intervals ![]() $[G/2,G)$, we get

$[G/2,G)$, we get

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\heartsuit

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

\sum_{\substack{S\ll T/G,\; P\ll T^2/G \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

T \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{GS}\right\vert}\right) (G\log{G}) \\

&+\sum_{\substack{G\in \{2r,4r,8r,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

\sum_{S\ll T/G,\; P\ll T^2/G}

T \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{GS}\right\vert}\right) \tau(r) (\frac{G}{r}\log{\frac{G}{r}}),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\heartsuit

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

\sum_{\substack{S\ll T/G,\; P\ll T^2/G \\ kS \equiv P \bmod{r}}}

T \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{GS}\right\vert}\right) (G\log{G}) \\

&+\sum_{\substack{G\in \{2r,4r,8r,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

\sum_{S\ll T/G,\; P\ll T^2/G}

T \log\left(2 + \frac{T}{\left\vert{GS}\right\vert}\right) \tau(r) (\frac{G}{r}\log{\frac{G}{r}}),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} where the last line accounts for the contribution from ![]() $g\equiv 0\bmod{r}$. The last line is

$g\equiv 0\bmod{r}$. The last line is

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2r,4r,8r,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

\sum_{S\ll T/G,\; P\ll T^2/G}

T (\frac{T}{\left\vert{GS}\right\vert})^{0.1} \tau(r) (\frac{G}{r})^{1.1} \\

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2r,4r,8r,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

T (T/G) (T^2/G) \tau(r) (\frac{G}{r})^{1.1} \\

&\ll T (T/r) (T^2/r) \tau(r)

\ll \frac{T^4}{r}.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2r,4r,8r,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

\sum_{S\ll T/G,\; P\ll T^2/G}

T (\frac{T}{\left\vert{GS}\right\vert})^{0.1} \tau(r) (\frac{G}{r})^{1.1} \\

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2r,4r,8r,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

T (T/G) (T^2/G) \tau(r) (\frac{G}{r})^{1.1} \\

&\ll T (T/r) (T^2/r) \tau(r)

\ll \frac{T^4}{r}.

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} Let ![]() $\mathcal{S}\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\}$ with

$\mathcal{S}\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\}$ with ![]() $\mathcal{S}\ll T/G$. If

$\mathcal{S}\ll T/G$. If ![]() $T^2/G\gg r$, then trivially

$T^2/G\gg r$, then trivially

\begin{equation}

\#\{S\asymp \mathcal{S},\; P\ll T^2/G: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}

\ll \mathcal{S} \frac{T^2/G}{r},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\#\{S\asymp \mathcal{S},\; P\ll T^2/G: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}

\ll \mathcal{S} \frac{T^2/G}{r},

\end{equation} and otherwise, by Lemma 4.3 with ![]() $c=1/3$ we have

$c=1/3$ we have

\begin{equation}

\#\{S\asymp \mathcal{S},\; P\ll T^2/G: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}

\ll \frac{\mathcal{S}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\#\{S\asymp \mathcal{S},\; P\ll T^2/G: kS \equiv P \bmod{r}\}

\ll \frac{\mathcal{S}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3}.

\end{equation} Upon summing over all possible choices for ![]() $\mathcal{S}$, we conclude that the first line of (4.8) is

$\mathcal{S}$, we conclude that the first line of (4.8) is

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G,\mathcal{S}\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ \mathcal{S}G\ll T}}

T\left(\frac{T}{\left\vert{G\mathcal{S}}\right\vert}\right)^{0.1} (G\log{G})

\mathcal{S} \left(\frac{T^2}{rG}

+ \frac{\boldsymbol{1}_{G\gg T^2/r}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3}\right) \\

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

T^2 (\log{G})

\left(\frac{T^2}{rG}

+ \frac{\boldsymbol{1}_{G\gg T^2/r}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3}\right) \\

&\ll \frac{T^4}{r} + T^2

\sum_{\substack{G\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ G\gg T^2/r}}

\frac{\log{G}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3} \\

&\ll \frac{T^4}{r} + T^2 \log\left(2+\frac{T^2}{r}\right),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G,\mathcal{S}\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ \mathcal{S}G\ll T}}

T\left(\frac{T}{\left\vert{G\mathcal{S}}\right\vert}\right)^{0.1} (G\log{G})

\mathcal{S} \left(\frac{T^2}{rG}

+ \frac{\boldsymbol{1}_{G\gg T^2/r}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3}\right) \\

&\ll \sum_{\substack{G\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ G\ll T}}

T^2 (\log{G})

\left(\frac{T^2}{rG}

+ \frac{\boldsymbol{1}_{G\gg T^2/r}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3}\right) \\

&\ll \frac{T^4}{r} + T^2

\sum_{\substack{G\in \{2,4,8,\ldots\} \\ G\gg T^2/r}}

\frac{\log{G}}{(\log(2+rG/T^2))^3} \\

&\ll \frac{T^4}{r} + T^2 \log\left(2+\frac{T^2}{r}\right),

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*} by Lemma 4.5 below, applied with ![]() $G=2^j$ and

$G=2^j$ and ![]() $2^s\asymp T^2/r$. But

$2^s\asymp T^2/r$. But  $\log\left(2+\frac{T^2}{r}\right) \ll 2+\frac{T^2}{r}$, so Theorem 4.4 follows.

$\log\left(2+\frac{T^2}{r}\right) \ll 2+\frac{T^2}{r}$, so Theorem 4.4 follows.

Lemma 4.5. For any ![]() $s\in \mathbb Z$, we have

$s\in \mathbb Z$, we have

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{D}(s) :=

\sum_{j\geqslant \max(1,s)} \frac{j}{\max(1,j-s)^3}

\ll \max(1,s).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{D}(s) :=

\sum_{j\geqslant \max(1,s)} \frac{j}{\max(1,j-s)^3}

\ll \max(1,s).

\end{equation*}Proof. If ![]() $s\leqslant 1$, then

$s\leqslant 1$, then

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{D}(s)

\leqslant \sum_{j\geqslant 1} \frac{j}{\max(1,j-1)^3}

\ll 1

= \max(1,s).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{D}(s)

\leqslant \sum_{j\geqslant 1} \frac{j}{\max(1,j-1)^3}

\ll 1

= \max(1,s).

\end{equation*} If ![]() $s\geqslant 1$, then a change of variables

$s\geqslant 1$, then a change of variables ![]() $j\mapsto j+s$ gives

$j\mapsto j+s$ gives

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{D}(s)

= \sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{j+s}{\max(1,j)^3}

\ll 1+s

\ll \max(1,s).

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\mathcal{D}(s)

= \sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{j+s}{\max(1,j)^3}

\ll 1+s

\ll \max(1,s).

\end{equation*}Each case is satisfactory.

Finally, we complete the proof of the lower bound of Theorem 1.1 in the case ![]() $\sqrt{r}\leqslant x\leqslant r$. By (3.4), (3.3), and Theorem 4.4, we have

$\sqrt{r}\leqslant x\leqslant r$. By (3.4), (3.3), and Theorem 4.4, we have

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{M}_4:= {\mathbb E}_\chi \left\vert{\sum_{n\in \mathbb Z } \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(\frac{n}{x})}\right\vert^4\!

\ll\!\! (x^{1-A})^4 + \frac{x^4}{r^2}\! \sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{2^{3j\delta}}

{1 + (T_jx/r)^{4A}\boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}}\!

\left(T_j^2 \!+\! \frac{T_j^4}{r}\right)\!,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{M}_4:= {\mathbb E}_\chi \left\vert{\sum_{n\in \mathbb Z } \chi(n) e(n\theta) w(\frac{n}{x})}\right\vert^4\!

\ll\!\! (x^{1-A})^4 + \frac{x^4}{r^2}\! \sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{2^{3j\delta}}

{1 + (T_jx/r)^{4A}\boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}}\!

\left(T_j^2 \!+\! \frac{T_j^4}{r}\right)\!,

\end{equation} where ![]() $T_j=2^j(2+r/x)$. Note that

$T_j=2^j(2+r/x)$. Note that

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{2^{3j\delta}}{1 + (T_jx/r)^{4A}\boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}} T_j^2

\ll T_0^2 + \frac{1}{(T_1x/r)^{4A}} T_1^2

\ll (2+r/x)^2,

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{2^{3j\delta}}{1 + (T_jx/r)^{4A}\boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}} T_j^2

\ll T_0^2 + \frac{1}{(T_1x/r)^{4A}} T_1^2

\ll (2+r/x)^2,

\end{equation*} assuming ![]() $3\delta+2 \lt 4A$. On the other hand,

$3\delta+2 \lt 4A$. On the other hand,

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{2^{3j\delta}}{1 + (T_jx/r)^{4A}\boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}} \frac{T_j^4}{r}

\ll \frac{T_0^4}{r} + \frac{1}{(T_1x/r)^{4A}} \frac{T_1^4}{r}

\ll \frac{(2+r/x)^4}{r},

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\sum_{j\geqslant 0} \frac{2^{3j\delta}}{1 + (T_jx/r)^{4A}\boldsymbol{1}_{j\geqslant 1}} \frac{T_j^4}{r}

\ll \frac{T_0^4}{r} + \frac{1}{(T_1x/r)^{4A}} \frac{T_1^4}{r}

\ll \frac{(2+r/x)^4}{r},

\end{equation*} assuming ![]() $3\delta+4 \lt 4A$. It follows that if

$3\delta+4 \lt 4A$. It follows that if ![]() $A \gt 1+3\delta/4$, then

$A \gt 1+3\delta/4$, then

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{M}_4

\ll \frac{x^4}{r^2} (2+r/x)^2

\left(1 + \frac{(2+r/x)^2}{r}\right)

\ll x^2(1+2x/r)^2,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathcal{M}_4

\ll \frac{x^4}{r^2} (2+r/x)^2

\left(1 + \frac{(2+r/x)^2}{r}\right)

\ll x^2(1+2x/r)^2,

\end{equation} since ![]() $\frac{x}{r}(2+r/x) = 1+2x/r$ and

$\frac{x}{r}(2+r/x) = 1+2x/r$ and ![]() $2+r/x \ll r^{1/2}$. Since

$2+r/x \ll r^{1/2}$. Since ![]() $x\leqslant r$, it follows that

$x\leqslant r$, it follows that ![]() $\mathcal{M}_4 \ll x^2$. This completes our analysis of the case

$\mathcal{M}_4 \ll x^2$. This completes our analysis of the case ![]() $x\geqslant \sqrt{r}$ in (1.8).

$x\geqslant \sqrt{r}$ in (1.8).

Acknowledgement

We thank Ofir Gorodetsky, Andrew Granville, Adam Harper, Youness Lamzouri, Kannan Soundararajan, Ping Xi, and Matt Young for their interest, helpful discussions, and comments. Special thanks are due to Jonathan Bober, Oleksiy Klurman, and Besfort Shala for sending us a letter about Question 1.3, and to Hung Bui for informing us of [Reference Heap and Sahay7]. V.W. thanks Stanford University for its hospitality and is supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska–Curie Grant Agreement No. 101034413. M.X. is supported by a Simons Junior Fellowship from the Simons Society of Fellows at the Simons Foundation.