Introduction

Employees’ compensation has been one of the fundamental pillars of business management, given its direct influence on employee motivation, performance, and satisfaction (Fulmer, Gerhart & Kim, Reference Fulmer, Gerhart and Kim2023). Employee compensation is part of an integrated reward system with two main dimensions: financial pay (such as salaries, incentives, and benefits) and non-financial pay, which include extrinsic aspects as recognition or favorable work conditions, and intrinsic ones derived from personal fulfillment, such as satisfaction, autonomy, and opportunities for growth or learning (Almadana Abón, Molina Gómez, Mercadé Melé & Núñez Sánchez, Reference Almadana Abón, Molina Gómez, Mercadé Melé and Núñez Sánchez2024). Although in this study we focus mainly on the financial component of compensation, we also take the other non-financial components into account.

Companies devote significant resources to providing satisfactory pay to their employees. A satisfactory pay system makes it possible to adequately reward employees’ efforts and competencies, in addition to contributing to talent retention and strengthening the organizational culture (Alterman et al., Reference Alterman, Bamberger, Wang, Koopmann, Belogolovsky and Shi2021; Gerhart & Fang, Reference Gerhart and Fang2015). Given its importance, it is not surprising that fields related to human resource management and organizational behavior have devoted considerable interest to analyzing employees’ pay satisfaction, particularly its antecedents and consequences.

However, the large volume of research in this field, along with the diversity of theoretical and practical approaches in organizations and the evolution of the concept over time, makes it necessary to review the existing literature in order to summarize the main conclusions and identify potential research gaps that warrant further attention (Öztürk, Kocaman & Kanbach, Reference Öztürk, Kocaman and Kanbach2024). Over time, the study of pay satisfaction has evolved from isolated theoretical formulations to a multifaceted field that reflects broader economic, social, and organizational transformations. The construct now encompasses not only individual attitudes toward compensation but also the strategic role of pay in shaping organizational culture, equity perceptions, and employee well-being. This evolution underscores the need to integrate dispersed findings and to understand how different contexts and methodological approaches have shaped current knowledge on the topic.

For this reason, this paper presents a bibliometric study with the following aims: (1) to assess productivity within this line of research by identifying the most influential agents (documents, authors, journals, countries, and affiliations); (2) to provide a comprehensive overview of how pay satisfaction has been addressed in the academic literature by analyzing publication trends in the field; and (3) to explore the social and conceptual structure of the field in order to reveal its evolutionary development.

Furthermore, by identifying trends and gaps in the existing research, this article aims to offer a roadmap for future investigations, highlighting the need to develop new approaches and practices that respond to the changing demands of today’s labor environment (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Yoon, Bamberger, Gerhart, Gupta, Nyberg and Sturman2015).

Literature review

Understanding how pay motivates employees has traditionally received great attention from academic research. In this sense, research examining how pay motivates employees has drawn on expectancy theory, which proposes that individuals, based on their previous experiences, are likely to engage in certain behaviors when they expect to receive something of value in return (Vroom, Reference Vroom1964). However, it remained unclear how experience influenced future behavior. Studies on satisfaction with pay introduced an intermediary variable – pay satisfaction (PS) – to explain the relationship between pay experiences and subsequent behavioral outcomes. During the following decades, various theoretical and methodological approaches enriched its analysis.

The earliest approaches to the study of PS can be found in the work of Klein and Maher (Reference Klein and Maher1966), who analyzed the dynamics involved in the relationship between education and PS. Models such as those proposed by Adams (Reference Adams1963, Reference Adams1965) and Lawler (Reference Lawler1971), offered a deeper understanding of the antecedents of PS, while the development of the Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ) by Heneman III and Schwab (Reference Heneman III and Schwab1985) marked a milestone in measuring this construct. Research based on the PSQ dominated academic discussions from the mid-eighties to the nineties, exploring not only the determinants of PS but also its implications for performance and organizational behavior (e.g. Judge, Reference Judge1993; Judge & Welbourne, Reference Judge and Welbourne1994). This transformed the way companies managed their human capital, paying greater attention to performance and productivity (Welbourne, Johnson & Erez, Reference Welbourne, Johnson and Erez1998).

Subsequent empirical evidence has linked PS to a wide variety of organizational attitudes and behaviors. For example, PS has been shown to be essential for job satisfaction and employee well-being (Clark, Kristensen & Westergård‐Nielsen, Reference Clark, Kristensen and Westergård‐Nielsen2009; Shaw, Duffy, Mitra, Lockhart & Bowler, Reference Shaw, Duffy, Mitra, Lockhart and Bowler2003), highlighting its importance in specific contexts such as the healthcare sector (Lum, Kervin, Clark, Reid & Sirola, Reference Lum, Kervin, Clark, Reid and Sirola1998) or accounting (Lynn, Cao & Horn, Reference Lynn, Cao and Horn1996). PS has also been shown to influence motivation (Igalens & Roussel, Reference Igalens and Roussel1999), sustainable innovation, and job performance (De Gieter & Hofmans, Reference De Gieter and Hofmans2015; Delmas & Pekovic, Reference Delmas and Pekovic2018; Williams, McDaniel & Nguyen, Reference Williams, McDaniel and Nguyen2006). It significantly contributes to reducing turnover and turnover intentions (DeConinck & Stilwell, Reference DeConinck and Stilwell2004; Weiner, Reference Weiner1980; Williams, Brower, Ford, Williams & Carraher, Reference Williams, Brower, Ford, Williams and Carraher2008; Williams et al., Reference Williams, McDaniel and Nguyen2006), increases organizational commitment (DeConinck, Reference DeConinck2009; Kulikowski, Reference Kulikowski2018), and encourages employees to take on leadership roles as well as both in-role and extra-role behaviors at work, due to a greater sense of value and commitment to the firm (Harold, Hu & Koopman, Reference Harold, Hu and Koopman2022).

At the start of the new century, the financial crisis led to an economic slowdown and, consequently, a global recession that affected labor relations, organizational changes, and an increase in unemployment (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Allan, England, Blustein, Autin, Douglass and Santos2017). Until the disruptions caused by COVID-19, in the context of globalization, studies on this type of satisfaction focused on increasing the efficiency of human resources to allow companies to obtain maximum business benefits under normal circumstances (e.g., Gibbs, Merchant, Stede & Vargus, Reference Gibbs, Merchant, Stede and Vargus2004; Schneider, Hanges, Smith & Salvaggio, Reference Schneider, Hanges, Smith and Salvaggio2003; Welbourne et al., Reference Welbourne, Johnson and Erez1998), as well as on managing business risks in high uncertainty and measuring whether working conditions met the standards ensuring suitable, fair work (e.g., Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Allan, England, Blustein, Autin, Douglass and Santos2017; Judge, Piccolo, Podsakoff, Shaw & Rich, Reference Judge, Piccolo, Podsakoff, Shaw and Rich2010; Kolodinsky, Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, Reference Kolodinsky, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz2008). After COVID-19, with the massive adoption of telework, companies adjusted their compensation policies due to pay reductions, inflation, and the challenges of accelerated digitalization.

Even though current research on PS has generated an impressive array of literature, the field remains fragmented in terms of theoretical approaches, methodological designs, and contextual applications. This dispersion makes it difficult to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the intellectual structure and evolution of the topic over time. Therefore, a bibliometric analysis is particularly valuable, as it allows for the systematic identification of research trends, influential works, and emerging themes, providing an integrated perspective on how the study of PS has developed and where future research efforts could be directed.

Methodology

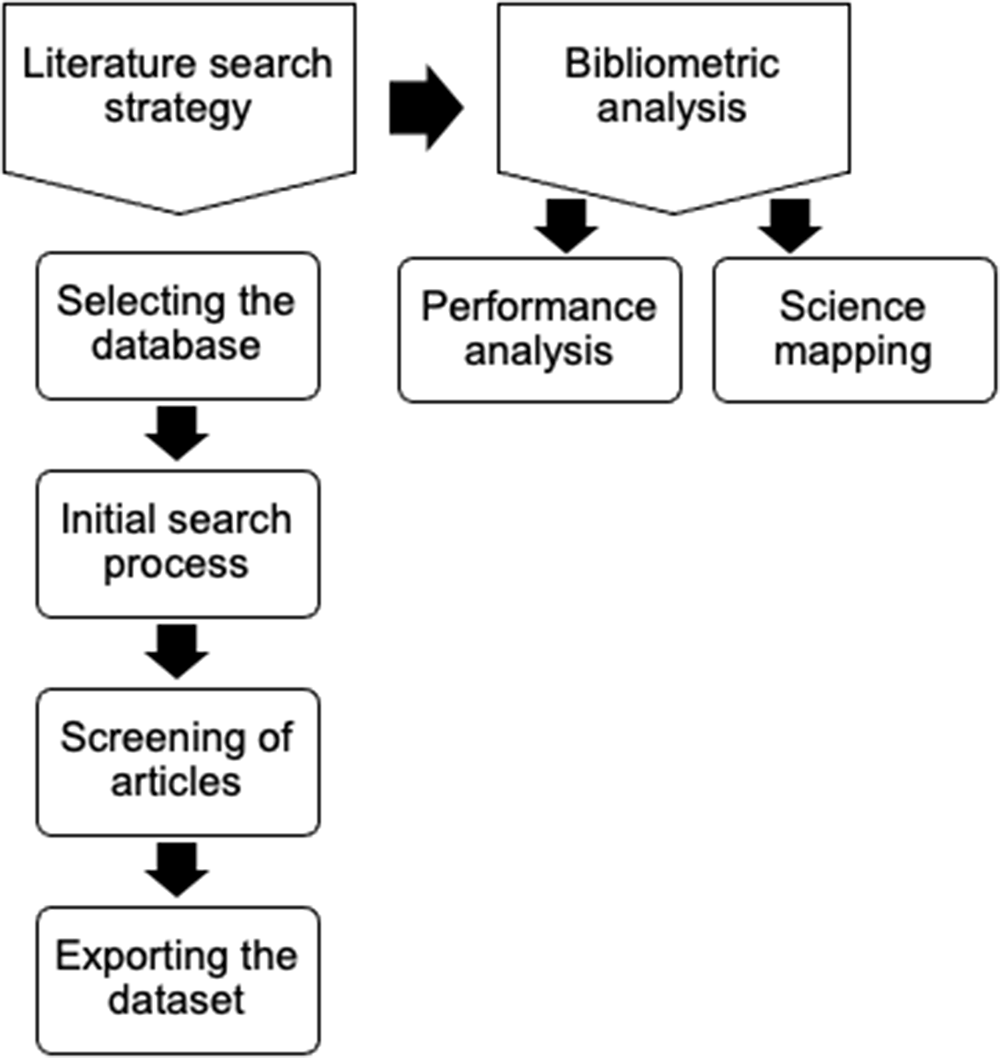

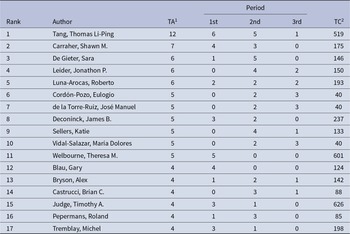

To conduct the bibliometric research, we follow Öztürk et al.’s (Reference Öztürk, Kocaman and Kanbach2024) two-step methodology for data collection and a comprehensive evaluation of the selected field of study. Öztürk et al. (Reference Öztürk, Kocaman and Kanbach2024) offer a functional framework for researchers who wish to conduct bibliometric research in any field, especially in business and management. Their contributions are practical in nature, particularly regarding best practices for designing and conducting bibliometric studies. The framework provides guidance for each decision in the process, outlining actions that support well-founded choices to carry out the research effectively and generate meaningful contributions. By adhering to this guidance, bibliometric studies can achieve greater rigor and robustness. The methodological flow diagram is presented in Fig 1.

Figure 1. Methodological flowchart of the research.

To identify the relevant bibliography from a transparent and reproducible approach this study was conducted following four stages (see Fig. 1).

(1) We selected the Web of Science (WoS) database. WoS is generally considered the most comprehensive database of scholarly work, covering thousands of journals, often including the most prominent ones (Župič & Čater, Reference Župič and Čater2015).

(2) The initial search process begins with the selection of keywords. In this way, all possible variants of terms related to PS were identified, with the aim of comprehensively including most of the research studies in the field. The search string can be found in Table 1. After searching for the terms in the topic, 995 studies published between 1966 and 2024 were identified. The search was conducted by the end of December 2024.

Table 1. Web of Science Consultation on Pay Satisfaction

Source: Own elaboration.

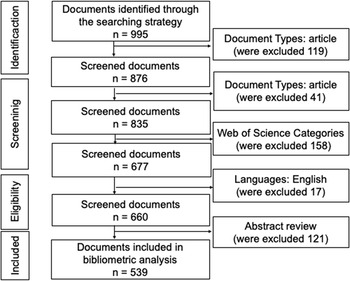

(3) The 995 identified studies are filtered to ensure that they are indeed related to the research field of PS. To perform this filtering, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) protocol. We included only ‘articles,’ as commonly done in bibliometric studies (e.g., Öztürk & Dil, Reference Öztürk and Dil2022). The selection was limited to categories directly related to the study topic – such as Management, Business, Psychology Applied… – for those fields where there could be some doubt, we reviewed each article’s abstract – and in case of doubt, the full texts – . We excluded documents written in languages other than English. We followed the flow of inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the dataset, as presented in a PRISMA diagram adapted from Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman (Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009) and edited in Fig 2.

Figure 2. Flow of inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the dataset.

After applying all the restrictions, a total of 539 publications were included. Since Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim (Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021) recommend having more than 500 articles to conduct a bibliometric analysis, our sample is considered sufficient.

(4) The final dataset was saved as a ‘tab-delimited text file,’ suitable for the software used, with the option ‘full record and cited references’ selected.

The bibliometric analysis was conducted using two procedures: performance analysis and scientific mapping (Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma & Herrera, Reference Cobo, López-Herrera, Herrera-Viedma and Herrera2011). It consists of revealing the social, conceptual, and intellectual structure in the evolutionary processes of a research field (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Kocaman and Kanbach2024). Therefore, scientific mapping is used to gain an overall view of the interactions among scientific actors from multiple perspectives (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck, Waltman, Ding, Rousseau and Wolfram2014).

For the bibliometric analyses, we used the free software package called Visualization of Similarities (VOS) viewer (www.vosviewer.com), developed by Van Eck and Waltman (Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010), version 1.6.20, as well as the Microsoft Excel package. Additionally, we used biblioNetwork function of the R package bibliometrix (www.bibliometrix.org), developed by Aria and Cuccurullo (Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). Data cleaning is essential for drawing accurate conclusions in bibliometric research (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021; Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Kocaman and Kanbach2024; Župič & Čater, Reference Župič and Čater2015). Therefore, a de-duplication process was carried out to refine the data before the analysis. First, we gathered the keywords assigned by the authors (Author Keywords) and by the database (Keyword Plus). The network is built by taking keywords that appear in at least 5 articles. This threshold is the default value set in the software tool (VOSviewer) and is a broadly accepted threshold within bibliometric analysis (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2010). Additionally, the selection of this threshold facilitates visualization on the map while ensuring that the keywords are sufficiently relevant and significant in the literature. We excluded the keywords we used in the initial search (see, Table 1). Second, a VOSviewer thesaurus file was developed to perform data cleaning (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021) and to merge terms. This may be useful not only for merging synonyms (e.g. ‘human-resource management´ and ‘HRM´) but also, for correcting spelling differences (e.g. ‘behavior´ and ‘behaviour´). Thesaurus file can be used to merge different variants of an author name. This may for example be useful when the name of a researcher is written in different ways in different documents (e.g. ‘Tang, Thomas Li-Ping´ and ‘Tang, TLP´).

Results

Performance analysis

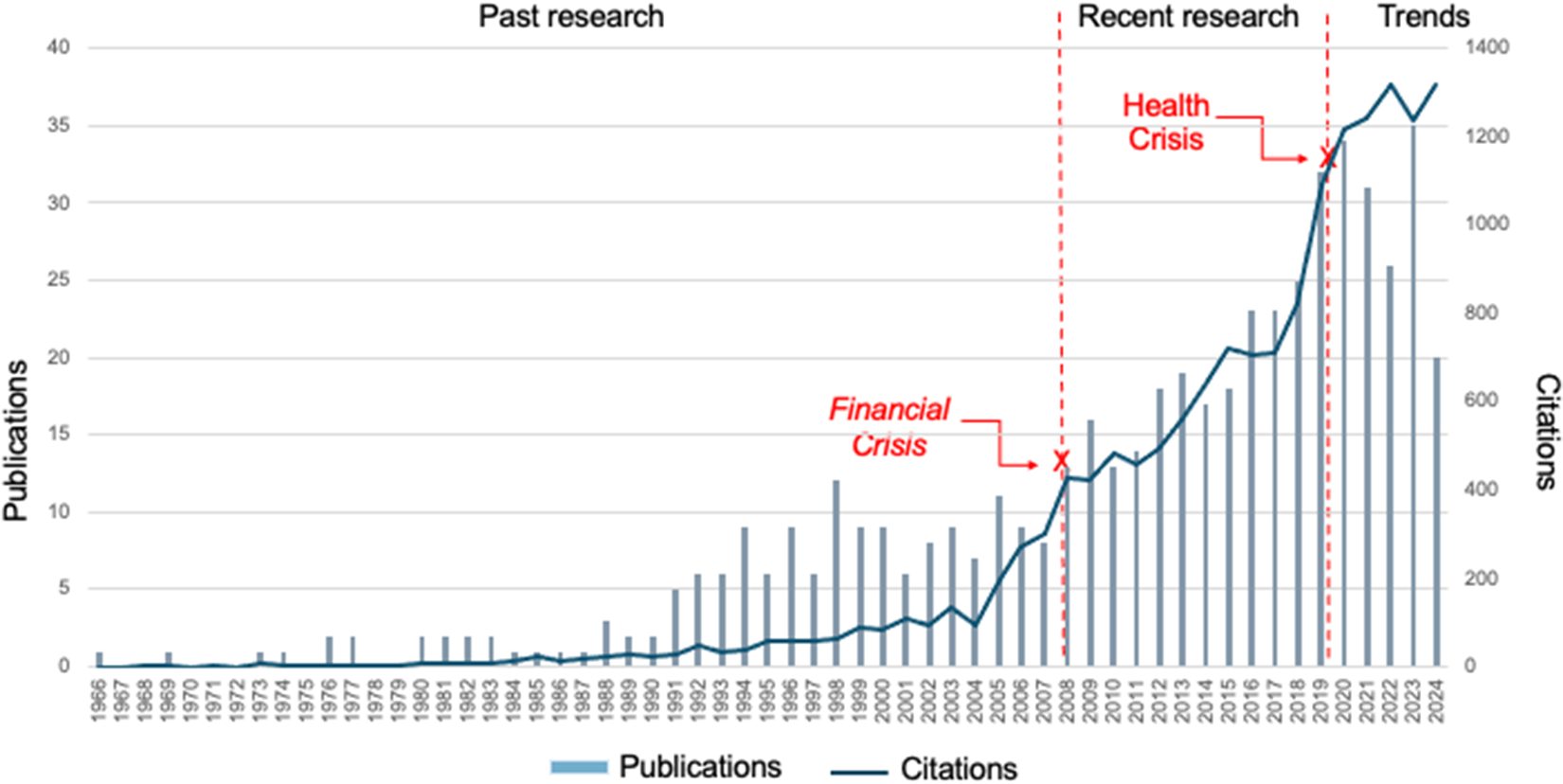

Annual evolution of publications and citations

The first study in the selected sample was published in the journal Personnel Psychology, by Klein and Maher (Reference Klein and Maher1966); since then and, especially in recent years, the number of articles published on this topic has increased considerably. The projected publication rate in this field of study grew steadily during the observed period, but showed some differences, reflecting three milestones in the development of the literature. In the first period, which corresponds to the first 42 years of research (1966 to 2007), referred to here as ‘past research,’ 162 documents were published (30.22% of the total), with an overall average of 4 publications per year. With 12 articles, 1998 was the year with the highest publication peak. This past research coincides with different economic phases, notably the economic expansion that began in the 1990s (Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Allan, England, Blustein, Autin, Douglass and Santos2017). This phase was characterized by economic growth driven by globalization and the emergence of new technologies and the digital economy. The year 2007 marks the first milestone in the PS research field. Thus began the second period (spanning 12 years), called ‘recent research,’ which corresponds to a rise in PS publications from 2008 to 2019, totaling 231 (43.10% of the total) and an average of 19 articles published per year. In 2019, the highest number of articles – 32 – was published. In this context, human resource practices prioritized the study of pay equity to determine the impact that pay adjustments triggered by the financial crisis could have on PS (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Yoon, Bamberger, Gerhart, Gupta, Nyberg and Sturman2015). Finally, in the last period (5 years), from 2020 to 2024, referred to here as ‘trends,’ it coincides with the emergence and spread of COVID-19. This stage represented an unprecedented shift, disruptively transforming the way we work. A total of 146 articles were published (26.68% of the total), with an average of 29 articles published per year, marking the historical peak in this research field in 2023, with 35 articles published. The results show that, despite the already growing interest in investigating PS, the COVID-19 pandemic brought a turning point. In this context, human resource practices prioritized well-being and flexibility (Bolino, Henry & Whitney, Reference Bolino, Henry and Whitney2024). Figure 3 shows the evolution of the number of publications and citations per year on the PS field.

Figure 3. Publication impact by year on pay satisfaction.

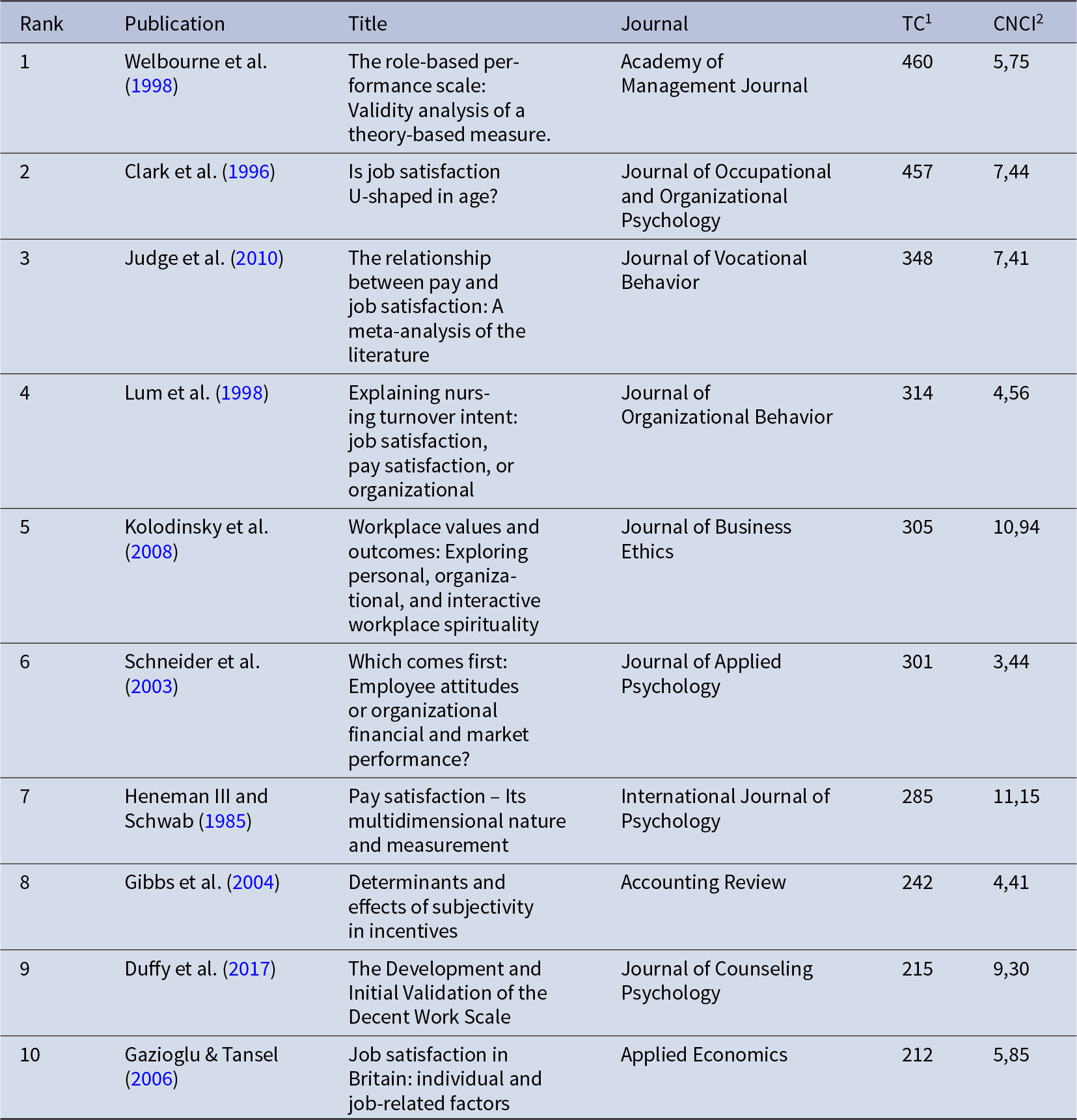

Most cited articles

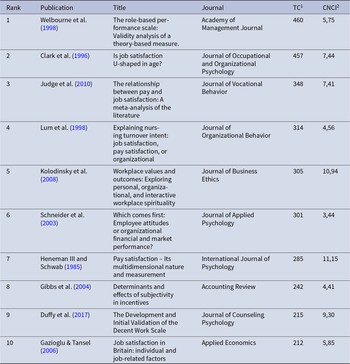

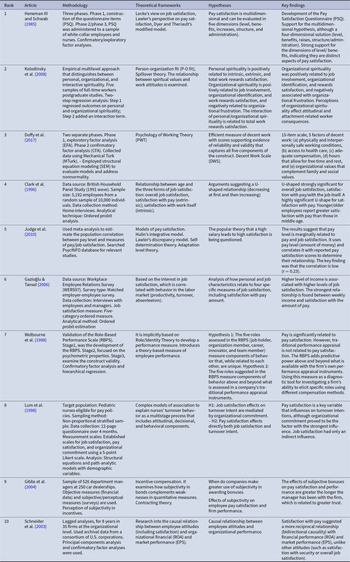

Publications during the three indicated periods (see Fig. 3) generated 1,953; 7,534 and 6,056 citations, respectively. According to Wang (Reference Wang2013), the most cited publications are often those published in earlier years due to the time that elapses between publication and being cited. Given the observed evolution pattern, it is reasonable to assume that this positive trend will continue. Table 2 shows the most cited publications. This numerical data is essential to present the most influential studies in the dataset. In addition to the ten most cited articles, we include in the table information on citation performance (the ratio of actual to expected citations) based on the Category Normalized Citation Impact (CNCI). CNCI is a normalized impact indicator, provided by InCites Benchmarking & Analytics, that compares documents of the same type, within the same category, and year. It is used to check a document’s citation performance. When performance is above average, the ratio is greater than one (CNCI > 1).

Table 2. Most cited publications in the dataset

Note: 1. TC: Total Citations. 2. CNCI Ratio: Category Normalized Citation Impact.

Source: Own elaboration.

Considering the ten most cited articles in the analysis of PS, various studies have contributed significantly to understanding the factors that influence how employees perceive their compensation and its relationship to job performance. One pioneering work in this area is by Welbourne et al. (Reference Welbourne, Johnson and Erez1998), who developed the Role-Based Performance Scale (RBPS), grounded in Katz and Kahn’s Role Theory (Reference Katz and Kahn1978) and Identity Theory (Burke, Reference Burke1991). This approach provided insight into how employees take on different roles within the company, directly influencing their PS. Indeed, their findings revealed that PS is more closely linked to the career role, whereas an emphasis on other organizational roles may generate dissatisfaction, thus highlighting the complexity of the relationship between PS and performance.

In general, the most frequently cited literature reviewed suggests that PS is a multidimensional construct (Heneman III & Schwab, Reference Heneman III and Schwab1985) influenced both by tangible factors, such as pay level and benefits (Judge et al., Reference Judge, Piccolo, Podsakoff, Shaw and Rich2010), and by intangible elements, such as professional recognition, trust, career opportunities, and alignment with organizational values (Gibbs et al., Reference Gibbs, Merchant, Stede and Vargus2004), challenging the traditional belief that a higher pay level always leads to greater satisfaction (Judge et al., Reference Judge, Piccolo, Podsakoff, Shaw and Rich2010).

Other impactful topics indicated by several highly cited works include, for example, changes in job expectations with age (Clark, Oswald & Warr, Reference Clark, Oswald and Warr1996), financial performance in companies (Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Hanges, Smith and Salvaggio2003), or turnover in the healthcare sector (Lum et al., Reference Lum, Kervin, Clark, Reid and Sirola1998). Finally, studies such as those by Kolodinsky et al. (Reference Kolodinsky, Giacalone and Jurkiewicz2008) and Duffy et al. (Reference Duffy, Allan, England, Blustein, Autin, Douglass and Santos2017) broadened the traditional focus of PS by including factors such as workplace spirituality and the perception of decent work. These studies highlight that, while PS remains a fundamental pillar, employees also seek an environment that respects their values and offers them a sense of purpose and fairness in their work.

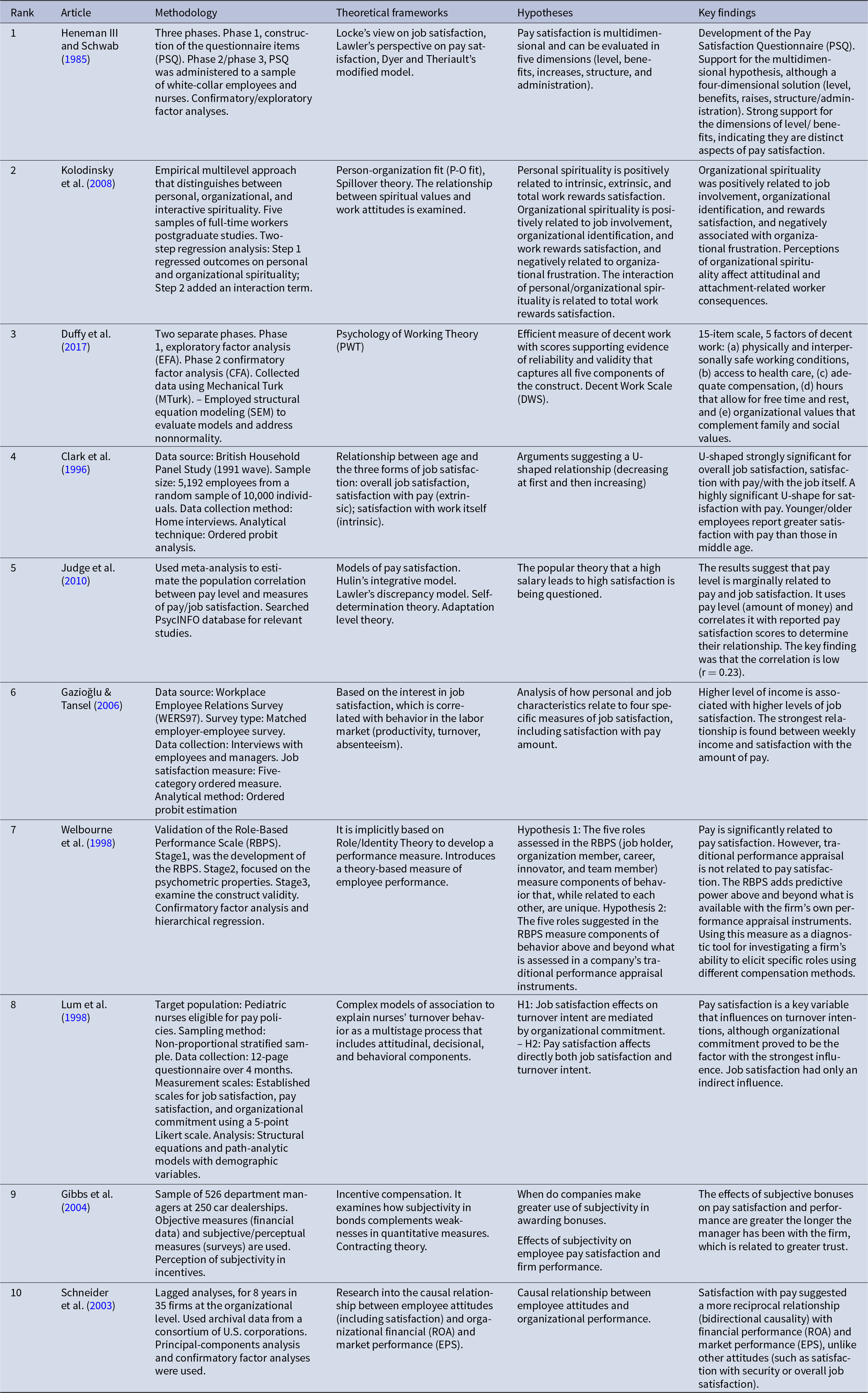

We observe that all the documents, when compared to other documents of the same type (i.e., articles), within the same category and published in the same year, perform above average (see CNCI > 1 in Table 2). The best-performing article is Heneman III and Schwab (Reference Heneman III and Schwab1985), with a ratio of 11.15. Table 3 summarizes the main articles according to its relevance, indicating their methodologies, theoretical frameworks, hypotheses, and key findings.

Table 3. Summary of the most cited articles in the sample according to their relevance

Note: We integrated quantitative (cited) and qualitative (Category Normalized Citation Impact ratio) data. Source: Own elaboration.

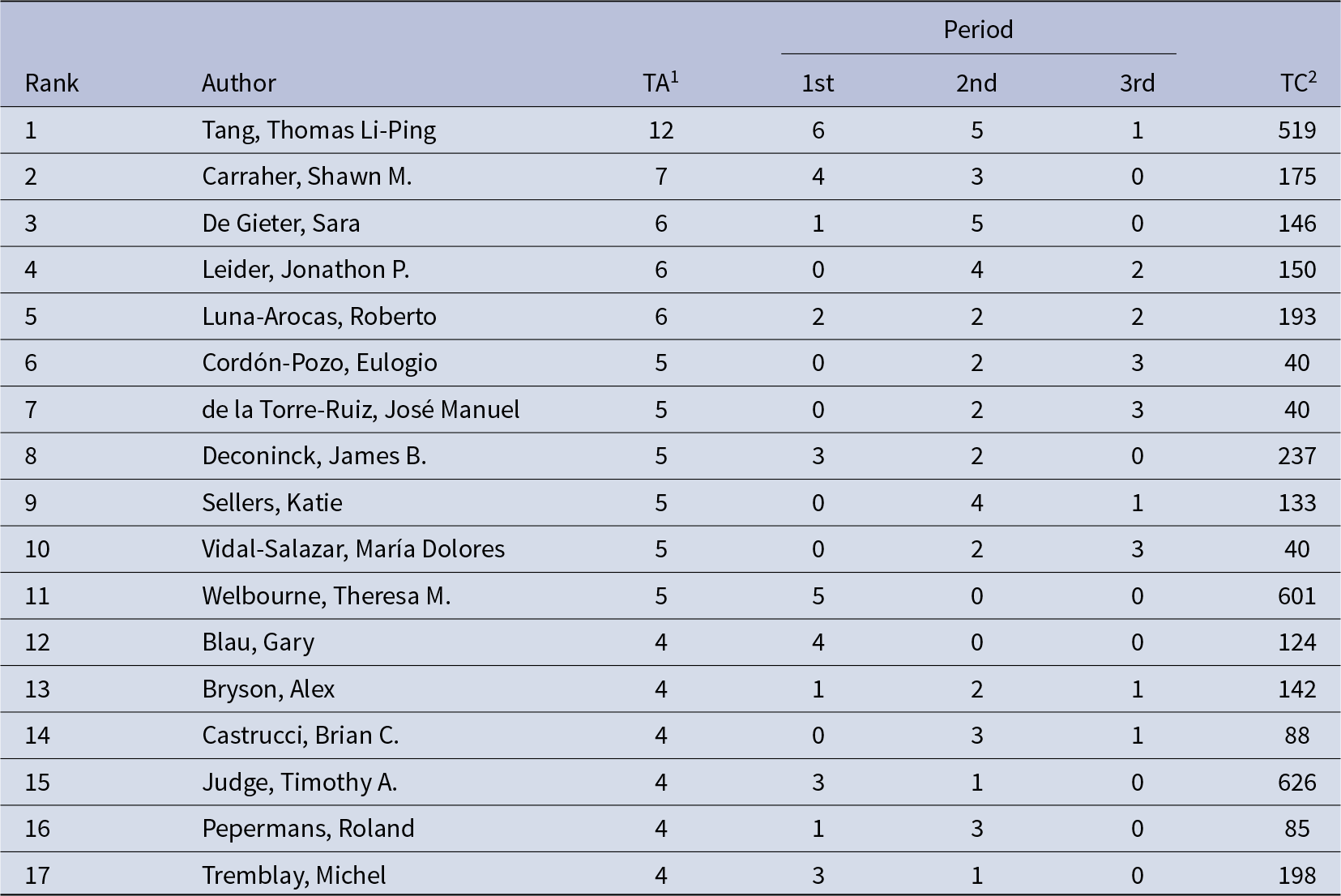

Most productive authors

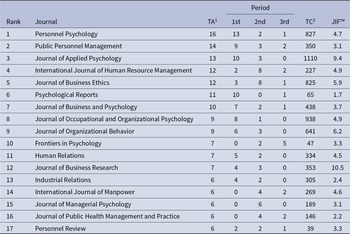

On the other hand, the 539 articles in our sample included a total of 1,396 authors. Those authors who contributed four or more articles are mentioned in Table 4. Their publications have been divided among the three analyzed periods (see Table 4). A total of 17 authors were included, who together account for over 16% of all the articles analyzed. Tang is the most prolific author in terms of article production, as he is the author of twelve articles.

Table 4. Most prolific authors in the dataset

Note: Articles by period: 1st = 1966–2007; 2nd = 2008–2019; 3rd = 2020–2024. 1. TA: Total Articles. 2. TC: Total Citations.

Source: Own elaboration.

We also analyzed whether the articles were written by a single author or by multiple authors, and found that 70 articles (i.e., 12.99%) were written by a single author. This means that more than three-quarters of the articles in our sample were written by more than one author, which can be interpreted as the presence of a research community on this topic and the tendency for authors to collaborate. Among the most cited authors, Judge ranks first.

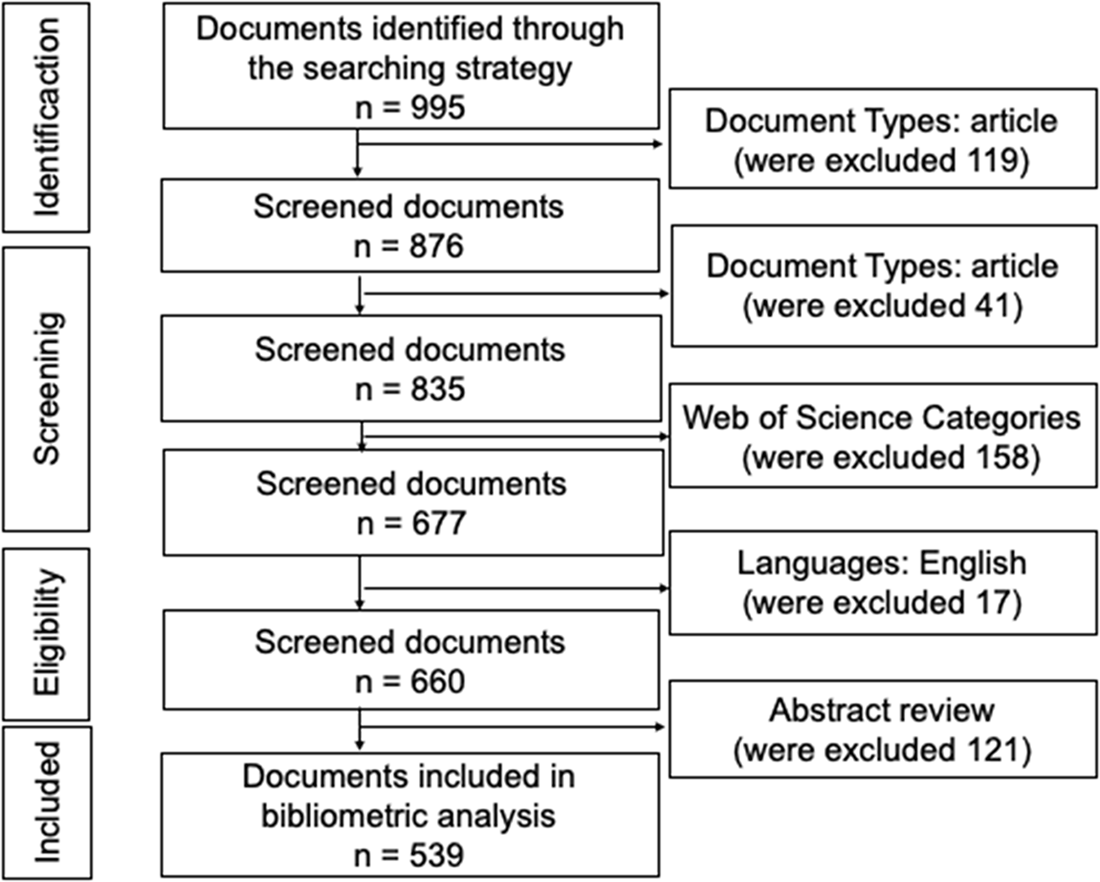

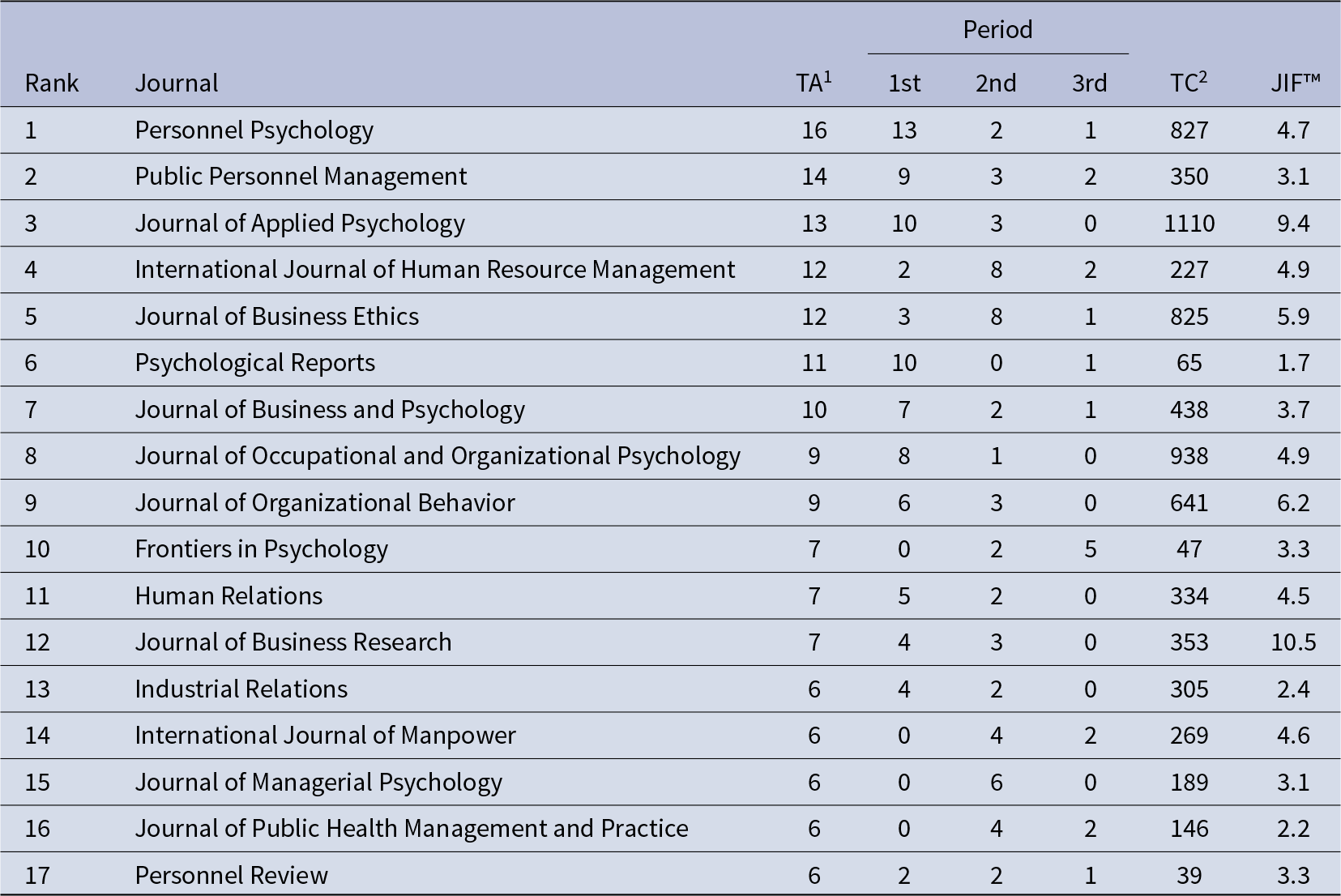

Most active journals, measured in number of articles and citations

The 539 articles were published in 278 different journals. Table 5 shows the 17 journals in which six, or more, articles on PS were published in our dataset, covering about 29% of the sample’s articles. The 2023 impact factor and the total citations of the listed journals are also shown in Table 5. More than 34% and 14% of the publications are in the ‘Management’ and ‘Business’ areas, respectively.

Table 5. The most active journals in the dataset

Note: Articles by Period: 1st = 1966–2007; 2nd = 2008–2019; 3rd = 2020–2024. 1. TA: Total Articles. 2. TC: Total Cites. JIF: Journal Impact ™ Factor 2023. We only include journals that contribute six or more articles to the field.

Source: Own elaboration.

The most productive journal is Personnel Psychology, with 16 published articles. Table 5 shows that these journals have reasonably high impact factors, which allows us to assert that the journals publishing articles related to PS are of relatively high quality. With very high impact factor values (for the year 2023), the Journal of Business Research (JIF: 10.5) is the top-ranked journal.

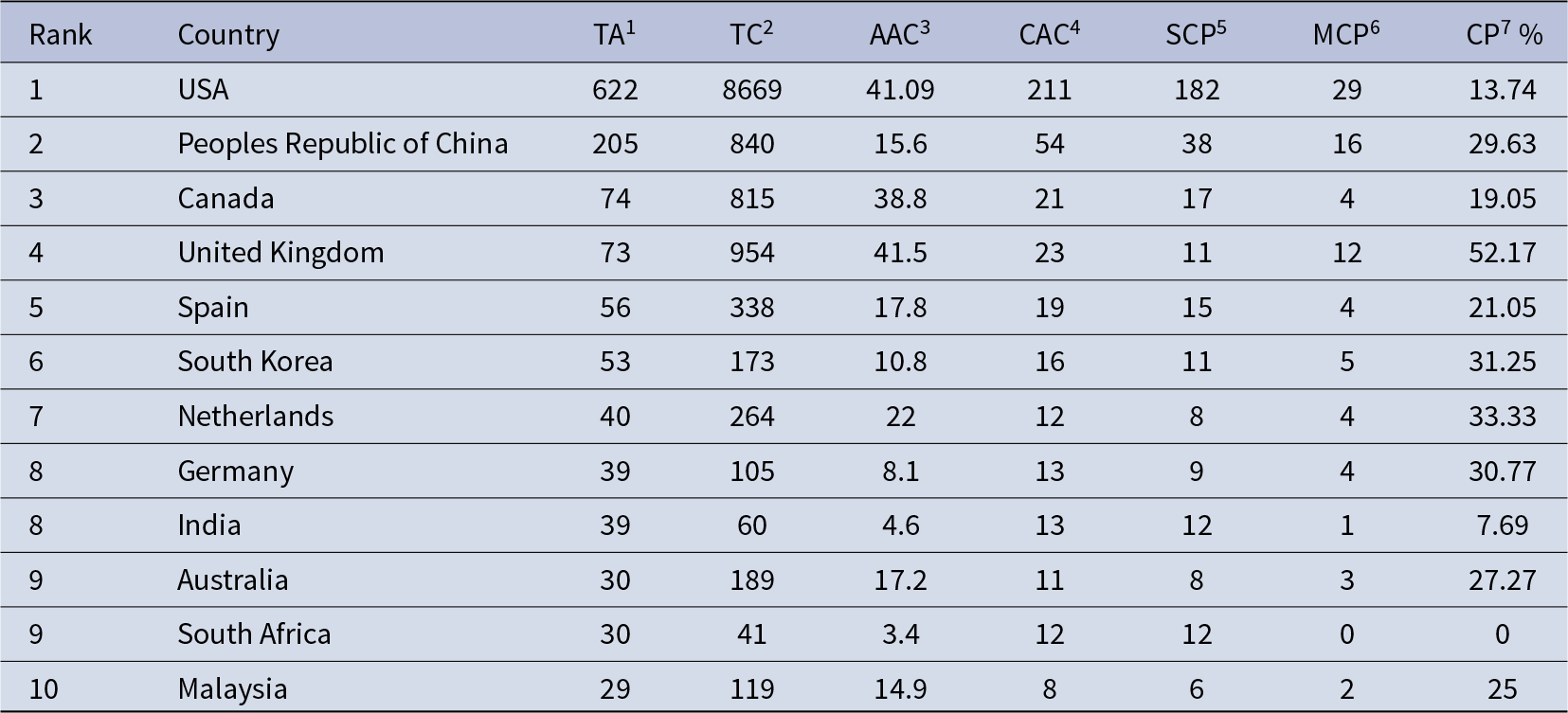

Most active countries and affiliations, measured in number of articles, citations, and collaborations

A total of 74 different countries and 708 different affiliations participated in the research for the 539 articles in the sample. Tables 6 and 7 show the most prominent countries and affiliations in the literature on PS, based on the number of publications and the total number of citations. The United States of America was undoubtedly the most productive country, with 211 articles (39.15% of the total) and 41.09 citations per article. The highest percentage of international collaboration was from the United Kingdom (52.17%), while the lowest was from South Africa, which did not collaborate internationally in the scientific production within the sample. Regarding affiliations, those with at least 5 articles in the dataset, the University of Wisconsin is the most active in scientific production in this line of research.

Table 6. The most active countries in the dataset

Note: 1: Total Articles; 2: Total Citations; 3: Average Article Citations; 4: Corresponding Author’s Countries; 5: Single Country Publications; 6: Multiple Country Publications. 7: Collaboration percentage.

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 7. The most active affiliations in the dataset

Note: Affiliations with at least 5 articles in the dataset. 1: Total Articles; 2: Total Citations.

Source: Own elaboration.

Science mapping

Scientific mapping makes it possible to establish the conceptual field by using a co-occurrence analysis of keywords. The co-occurrence analysis creates groups of keywords (Author Keyword and Keyword Plus) that appear together frequently, with each group representing a specific topic (Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck and Waltman2017). The purpose of this analysis is to highlight the connections among the keywords that, at a given time, are considered most relevant (Callon, Courtial & Laville, Reference Callon, Courtial and Laville1991).

The concept underlying this network is based on the idea that when certain keywords appear frequently in literature, they are more likely to be thematically related (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021). Therefore, the goal is to locate these subgroups, or clusters, that are closely linked to one another and correspond to areas of interest or research issues (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Kocaman and Kanbach2024). Once the clusters are identified, through trend maps, we provide a deeper view of the interconnections and relationships among the various concepts within the cluster over time (see Van Eck & Waltman, Reference Van Eck, Waltman, Ding, Rousseau and Wolfram2014).

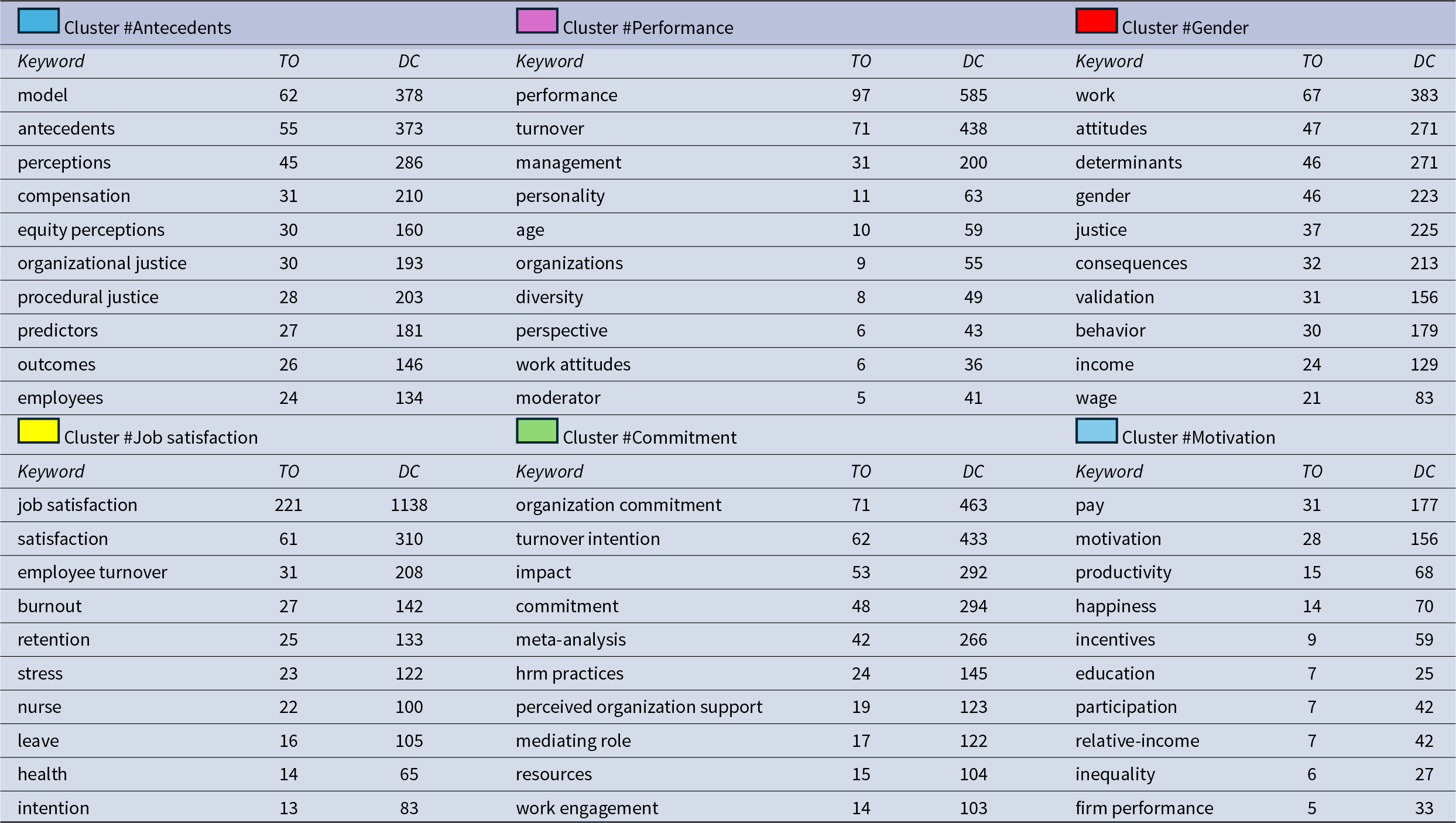

Keyword co-occurrence analysis

We created a graphical representation of the research areas on PS and how each area relates to the others. Therefore, the objective is to locate the subgroups, or clusters, that are closely linked to each other and correspond to areas of interest or research problems (Öztürk et al., Reference Öztürk, Kocaman and Kanbach2024). Six clusters were obtained, corresponding to the main research topics in the field of PS. The cluster #1 (red) is named ‘gender’; the cluster #2 (green) is named ‘commitment’; the cluster #3 (blue) is named ‘antecedents’; the cluster #4 (yellow) is named ‘job satisfaction’; the cluster #5 (purple) ‘performance’; and the cluster #6 (cyan) is named ‘motivation.’

By using the keyword co-occurrence method, it was established that a set of ‘signal words’ reflect the core content of the research literature (see, Vermaut, Burnay & Faulkner, Reference Vermaut, Burnay and Faulkner2024). These signal words were obtained by extracting the 10 most important nodes of each cluster in terms of total occurrences and total link strength (or degree of centrality). The degree of centrality measures the number of times a keyword is linked with other keywords in the keyword co-occurrence network (Vermaut et al., Reference Vermaut, Burnay and Faulkner2024). The higher the degree, the more central the keyword is. Table 8 summarizes the top 60 most prolific and trending topics on PS of each cluster, classified according to the total number of keyword occurrences (TO) and their degree of centrality (DC). Among the most prolific topics, job satisfaction, performance, organization commitment, and turnover have appeared.

Table 8. Top ten most frequent keywords by cluster

Note: TO: total occurrences; DC: degree of centrality.

Source: own elaboration.

Visualization keyword co-occurrence analysis

Figure 4 presents the visualization of the keyword co-occurrence network in the field of PS, from 1966 to 2024. Readers interested in an in-depth analysis can use VOS viewer interactively and zoom in on the map at the following URL: https://tinyurl.com/2c4339fu

Figure 4. Keyword co-occurrence network map.

Figure 5 shows the temporal mapping of the identified topics. This map allows us to establish a chronological order of the developments that research on PS has undergone. The temporal mapping, generated in VOS viewer, is identical to the network visualization, except that the elements are colored differently to reflect the relative importance of the average year of publication. In the lower right corner of the visualization, there is a color bar (see Fig. 5). This color bar indicates how the scores are assigned to colors. The scores of the keywords (average publication year) are represented by colors ranging from blue for scores lower than or equal to the minimum score (2007), to green for intermediate scores (2008–2019), and to yellow for scores higher than or equal to the maximum score (2020).

Figure 5. Keyword co-occurrence overlay map.

Sensemaking is applied to interpret the co-occurrences patterns and interrelations among the topics within each cluster (see Figures S5.1–5.6 in Supplementary material), with keywords structure to construct a coherent narrative that encapsulates both the essence and the scope of the cluster (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021).

Cluster #Antecedents. Among the various factors that may explain PS, previous studies have analyzed administrative, environmental, structural, and situational factors (e.g., Dyer & Theriault, Reference Dyer and Theriault1976; Weiner, Reference Weiner1980). Nevertheless, as reflected by the predominant keywords in this cluster, research on the causes of PS has been based on two key models: equity theory (Adams, Reference Adams1965) and discrepancy theory (Lawler, Reference Lawler1971). Both models highlight the importance of subjective evaluations in predicting PS. In this context, Heneman III and Schwab (Reference Heneman III and Schwab1985) propose and validate a multidimensional model for PS, according to which employees evaluate their pay using relative standards (equity and comparisons) that predict satisfaction. This model has been developed further by subsequent research aiming to determine the antecedents of PS (e.g., Berkowitz, Fraser, Treasure & Cochran, Reference Berkowitz, Fraser, Treasure and Cochran1987; Bygren, Reference Bygren2004; DeConinck & Stilwell, Reference DeConinck and Stilwell2004; Heneman & Judge, Reference Heneman, Judge, Rynes and Gerhart2000; Major & Testa, Reference Major and Testa1989). In more recent years, these equity-based models have been developed further, for example, by incorporating the moderating effect of pay level when explaining the impact of pay discrepancies on PS (Yao, Locke & Jamal, Reference Yao, Locke and Jamal2018). Because equity perceptions are considered one of the standards that trigger the perception of a type of organizational justice – specifically distributive justice – it is not surprising that within this cluster, we find studies that use organizational justice as a theoretical foundation and incorporate its different dimensions (distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational) into models of PS research (e.g., Heneman & Judge, Reference Heneman, Judge, Rynes and Gerhart2000; Welbourne, Reference Welbourne1998).

In recent decades, the major changes in compensation systems (for example, the rising importance of benefits and variable pay) have led researchers to develop new theoretical models of PS, broadening its scope to reflect all aspects of compensation (e.g., Williams et al., Reference Williams, Brower, Ford, Williams and Carraher2008). Within this context, pay communication emerges as a relevant topic (e.g., Day, Reference Day2011; de la Torre-ruiz, Cordón-Pozo, Vidal Salazar & Ortiz-Perez, Reference de la Torre-ruiz, Cordón-Pozo, Vidal Salazar and Ortiz-Perez2024; Jawahar & Stone, Reference Jawahar and Stone2011; Till & Karren, Reference Till and Karren2011; Xavier, Reference Xavier2014). Although firms invest money and resources in implementing human resource management practices designed to improve employee well-being, they often fail to communicate clearly and effectively about the characteristics and advantages of these practices. The latest research carried out in this cluster focuses on benefits communication as a means of influencing employees’ pay comparisons and consequently its positive association with satisfaction (e.g., Cordón-Pozo, Vidal-Salazar, de la Torre-ruiz & Gómez-Haro, Reference Cordón-Pozo, Vidal-Salazar, de la Torre-ruiz and Gómez-Haro2023). Hence, attention to communicating benefits is a critical variable in ensuring the effectiveness and return on investment of the total compensation packages offered by the organization. The implementation of communication strategies is not optional but rather a strategic imperative to maximize the effectiveness of compensation systems and meet the expectations of an increasingly informed and demanding workforce. In this sense, it can also help companies adapt to expanding transparency requirements in the European Union, where the principle of equal pay has recently been strengthened through new pay transparency measures (see Directive (EU) 2023/970).

Cluster #Performance. This cluster is closely related to the studies identified in the previous cluster, as performance has been considered a determining factor in pay judgments. People who evaluate their own performance positively are often less satisfied with their pay, due to the perception of a greater discrepancy between effort and reward (Lawler, Reference Lawler1971). This is why many of the studies included in this cluster analyze the factors that may influence how that performance is perceived. Thus, external performance evaluations, along with objective factors such as age, seniority, and education (e.g., Motowidlo, Reference Motowidlo1982), or subjective ones such as social comparisons (e.g., Major & Testa, Reference Major and Testa1989), are potential sources of variation in self-perceived performance. Furthermore, perceived performance is not only an intrinsic factor; it is also influenced by the social and business environment (Vest, Scott & Markham, Reference Vest, Scott and Markham1994). Understanding these factors has proven relevant in studies on PS, given the close relationship between performance perception and PS. Within this cluster, we also find studies that have analyzed the effectiveness of performance-based compensation systems and their effect on employees’ PS (e.g., Welbourne et al., Reference Welbourne, Johnson and Erez1998). Recent research highlights performance management in employees’ PS processes (e.g., Xavier, Reference Xavier2014). It addresses the complexity of modern work environments, from generational perspectives, where people are considered a key factor within companies. Therefore, research focuses on aligning personal and organizational goals by emphasizing performance-based reward systems (e.g., Conroy & Gupta, Reference Conroy and Gupta2019; Kulikowski, Reference Kulikowski2018).

Cluster #Gender. Early research on the field of PS and gender focused on a simplistic perspective that considered several objective factors – such as education, pay, or sex – as predictors of PS (e.g., Klein & Maher, Reference Klein and Maher1966; Penzer, Reference Penzer1969; Ronan & Organt, Reference Ronan and Organt1973). However, subsequent studies found that although objective factors, primarily pay and sex, partly predict PS, incorporating employees’ subjective perceptions could substantially improve that predictive capability (e.g., Dreher, Reference Dreher1981). Moreover, some studies have considered the moderating effect of gender to analyze the measurement invariance of Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ) – a commonly used tool to measure PS – to determine whether it works adequately in different contexts and populations (e.g., De Gieter, Hofmans, De Cooman & Pepermans, Reference De Gieter, Hofmans, De Cooman and Pepermans2009). This is because previous research has shown how cultural or social factors can affect, for instance, how men and women interpret career success differently (e.g., Fernández Puente & Sánchez Sánchez, Reference Fernández Puente and Sánchez Sánchez2021), have varying attitudes toward different career stages (e.g., Lynn et al., Reference Lynn, Cao and Horn1996), or value work-life balance policies differently (e.g., Kanu, Odinko & Ujoatuonu, Reference Kanu, Odinko and Ujoatuonu2023). Considering the moderating effect of gender, cultural, and organizational context would ensure the equivalence of the questionnaire’s measurement structure, allowing for comparison of PS in international studies and across genders (e.g., Arya, Mirchandani & Harris, Reference Arya, Mirchandani and Harris2019; Dreher, Carter & Dworkin, Reference Dreher, Carter and Dworkin2019). In this way, these studies have examined to what extent the influence of various antecedents of PS – such as equity perceptions (e.g., Gomez-Mejia & Balkin, Reference Gomez-Mejia and Balkin1984), the referents used for comparison (e.g., Ataay, Reference Ataay2018), the perceived value of money (e.g., Li‐Ping Tang, Luna‐Arocas & Sutarso, Reference Li‐Ping Tang, Luna‐Arocas and Sutarso2005; Luna-Arocas & Tang, Reference Luna-Arocas and Tang2004) or attitudes toward money (e.g., Sahi, Reference Sahi2023) – differs between women and men. Previous research has confirmed these discrepancies, revealing differences between men and women regarding perceptions of their pay (e.g., Davison, Reference Davison2014). Especially notable are those studies that have examined the so-called ‘satisfied female paradox,’ which explores why some women are more satisfied with their pay than men despite earning less (e.g., Brüggemann & Hinz, Reference Brüggemann and Hinz2023; Smith, Reference Smith, Kendall and Hulin2020).

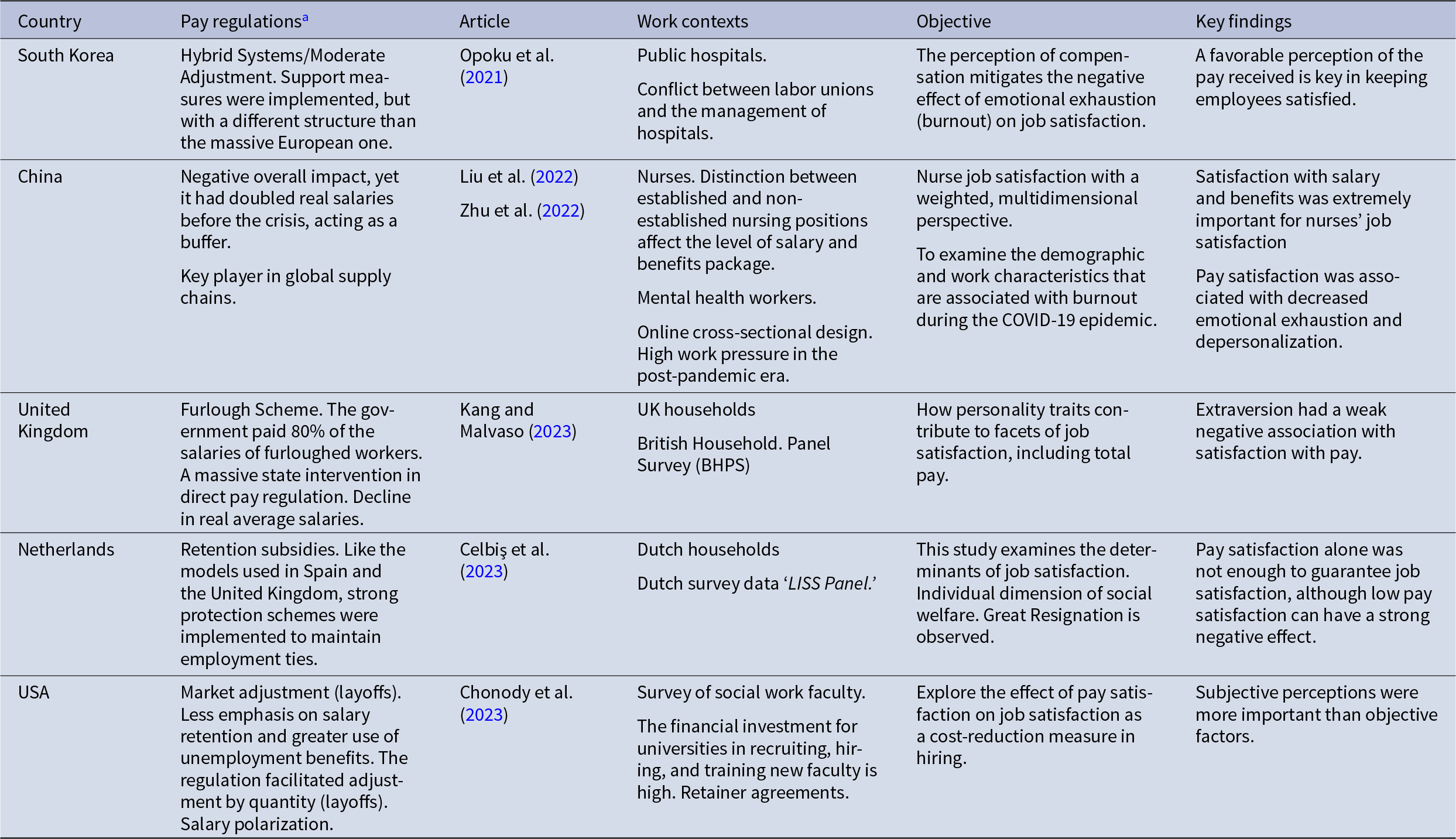

Cluster #Job satisfaction. Initially, past research in the field of PS and job satisfaction focused on understanding how better educated and more highly trained workers affected labor relations and increased expectations about employment (e.g., Klein & Maher, Reference Klein and Maher1966; Penzer, Reference Penzer1969). The Job Descriptive Index (JDI) developed by Smith, Kendall and Hulin (Reference Smith, Kendall and Hulin1969) measured job satisfaction through five key dimensions: the work itself, pay, opportunities for promotion, supervision, and coworkers. These dimensions laid the groundwork for establishing PS as a crucial component of job satisfaction (e.g., Schwab & Wallace Jr, Reference Schwab and Wallace1974). Subsequently, sector-specific studies in nursing (e.g., Lum et al., Reference Lum, Kervin, Clark, Reid and Sirola1998) or accounting (e.g., Lynn et al., Reference Lynn, Cao and Horn1996), emphasized the importance of considering specific contexts when analyzing job satisfaction. Likewise, in more recent years, studies have focused on countries such as China (e.g., Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhou, Jin, Chuang, Chien and Tung2022), South Korea (e.g., Opoku, Yoon, Kang & You, Reference Opoku, Yoon, Kang and You2021), United Kingdom (e.g., Kang & Malvaso, Reference Kang and Malvaso2023), the Netherlands (e.g., Celbiş, Wong, Kourtit & Nijkamp, Reference Celbiş, Wong, Kourtit and Nijkamp2023), or among others, the USA (e.g., Chonody, Kondrat, Godinez & Kotzian, Reference Chonody, Kondrat, Godinez and Kotzian2023), and studies conducted in cross-country comparison such as USA vs Spain (e.g., Luna-Arocas & Tang, Reference Luna-Arocas and Tang2004, Reference Luna-Arocas and Tang2015). Cultural values (such as family identity and collectivism), unionization, and sectoral differences determine both the antecedents and consequences of pay satisfaction.

Similarly, the effect of such satisfaction on voluntary turnover (e.g., Li-Ping Tang, Kim & Shin-Hsiung Tang, Reference Li-Ping Tang, Kim and Shin-Hsiung Tang2000) or on motivation (e.g., Igalens & Roussel, Reference Igalens and Roussel1999) was also explored. Beginning in the 2000s, research on job and PS developed by examining additional organizational factors, such as performance-based pay (e.g., Green & Heywood, Reference Green and Heywood2008) and human resource practices (e.g., Ileana Petrescu & Simmons, Reference Ileana Petrescu and Simmons2008), as well as well-being (e.g., Clark et al., Reference Clark, Kristensen and Westergård‐Nielsen2009). In this context, the importance of compensation strategies to facilitate employee retention (Judge et al., Reference Judge, Piccolo, Podsakoff, Shaw and Rich2010) and the pressures to become more sustainable led to new lines of research focusing on rewards and work-related stress (e.g., Delmas & Pekovic, Reference Delmas and Pekovic2018), or decent work (e.g., Duffy et al., Reference Duffy, Allan, England, Blustein, Autin, Douglass and Santos2017).

The COVID-19 pandemic marked a turning point in research on job and PS (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhou, Jin, Chuang, Chien and Tung2022), placing greater emphasis on employee well-being and mental health (Zhu, Xie, Liu, Yang & Zhou, Reference Zhu, Xie, Liu, Yang and Zhou2022). Consequently, the latest trends in PS have produced studies on burnout (e.g., Atkins, Sener, Drake & Marley, Reference Atkins, Sener, Drake and Marley2023), especially in the healthcare and caregiving sectors (e.g., Opoku et al., Reference Opoku, Yoon, Kang and You2021; Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Xie, Wong, Lai, Chen and Qin2024; Young, Aronoff, Goel, Jerome & Brower, Reference Young, Aronoff, Goel, Jerome and Brower2023; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Xie, Liu, Yang and Zhou2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, pay satisfaction played a key role in employee well-being and retention. Although research suggests that compensation alone may not be sufficient to offset the detrimental effects of burnout on job turnover intentions (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Zhang, Xie, Wong, Lai, Chen and Qin2024), pay satisfaction can reduce burnout, particularly by decreasing emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Xie, Liu, Yang and Zhou2022). Likewise, in recent years, there has been a growing focus on diversity and individual differences in the workplace (e.g., Kang & Malvaso, Reference Kang and Malvaso2023).

The relationship between pay satisfaction and job satisfaction varies according to sector and geographical context (see Table 9). In sectors directly affected by COVID-19, such as nursing or mental health work, pay satisfaction was investigated as a measure to reduce burnout (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Zhou, Jin, Chuang, Chien and Tung2022; Opoku et al., Reference Opoku, Yoon, Kang and You2021; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Xie, Liu, Yang and Zhou2022). In some geographical contexts, where there were regulatory distinctions regarding the COVID-19 crisis, the relationship between pay satisfaction and job satisfaction was examined as an individual dimension of social welfare (Celbiş et al., Reference Celbiş, Wong, Kourtit and Nijkamp2023; Kang & Malvaso, Reference Kang and Malvaso2023), or as a cost-reduction measure in hiring (Chonody et al., Reference Chonody, Kondrat, Godinez and Kotzian2023). This involved the choice between prioritizing job preservation at the expense of average salary levels (as seen in Spain, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands) and tolerating job destruction while upholding income via unemployment insurance (U.S. approach). European countries leveraged salaries as the primary adjustment mechanism, implementing temporary reductions through short-time work schemes (such as ERTEs and furloughs) to mitigate the risk of mass unemployment, with regulation focused on preserving the productive sector and the workforce’s skills. Conversely, the U.S. adjustment was characterized by significant job losses and a disproportionate fall in salaries at the lower end of the distribution, suggesting less protection and greater reliance on layoffs and direct pay cuts in firms’ strategies.

Table 9. Summary of the relevance of contextual differences

Note.

a COVID-19 Answer (ILO Global Wage Report 2020–21).

Source: Own elaboration.

Beyond salary, other dimensions of job satisfaction are emerging in recent literature, such as psychosocial factors like autonomy, job stability, work-life balance, and supportive leadership, among others. For example, Ritter, Small and Everett (Reference Ritter, Small and Everett2022) found that exchange relationships built on loyalty and respect directly affected performance appraisal satisfaction, which also positively impacted job and reward satisfaction. Filandri, Pasqua and Tomatis (Reference Filandri, Pasqua and Tomatis2024) found that, when different dimensions of satisfaction are considered, both job stability and salary are relevant to job satisfaction, and there does not appear to be any compensatory effect. The ‘psychosocial dimensions’ mentioned are not mere peripherals, but structural determinants of employee well-being.

Cluster #Commitment. Within this cluster, we primarily find research analyzing the relationship between PS and organizational commitment, demonstrating that this relationship is complex. While most studies find a positive relationship between PS and organizational commitment (e.g., Luna-Arocas, Danvila-Del Valle & Lara, Reference Luna-Arocas, Danvila-Del Valle and Lara2020), other works are less conclusive. For example, Piotrowska (Reference Piotrowska2022) highlights that certain non-pay elements of a job, such as the ability to telework, exert a greater influence on organizational commitment than PS. Meanwhile, Giauque, Resenterra and Siggen (Reference Giauque, Resenterra and Siggen2010) do not find any relationship between PS and the commitment of highly qualified workers. However, an explanation for this absence of a relationship can be found in the work of Jayasingam and Yong (Reference Jayasingam and Yong2013), who find that the relationship between PS, and the affective commitment of highly qualified workers only occurs when they perform tasks that are not knowledge intensive. Other studies have incorporated the intention to leave the organization into the analysis of this relationship, again yielding complex and diverse results. While some studies show that the relationship between PS and the intention to leave the organization is mediated by organizational commitment (e.g., Panaccio, Vandenberghe & Ben Ayed, Reference Panaccio, Vandenberghe and Ben Ayed2014), others indicate that PS acts as a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and the intention to leave the organization (e.g., Hung, Lee & Lee, Reference Hung, Lee and Lee2018). Finally, within this cluster, we also find studies that have examined the relationship between PS and other attitudes or behaviors that are, in some ways, related to commitment, such as the intention to leave (e.g., DeConinck & Stilwell, Reference DeConinck and Stilwell2004; Redondo, Sparrow & Hernández-Lechuga, Reference Redondo, Sparrow and Hernández-Lechuga2023).

Cluster #Motivation. In this cluster, we can highlight studies that have analyzed the motivating nature of pay in general, and PS, in particular. Although PS and the motivating effect of pay have traditionally been considered to relate directly to the amount of money received, various studies have shown that money is not the only factor that can influence employee motivation and its impact depends on how employees value money (Luna-Arocas & Tang, Reference Luna-Arocas and Tang2004).

Recent worldwide crises (e.g., the Covid-19 pandemic) have changed employees’ expectations about compensation and working conditions, resulting in phenomena such as the Great Resignation (Celbiş et al., Reference Celbiş, Wong, Kourtit and Nijkamp2023). Therefore, it is considered necessary to consider other types of intrinsic motivators that complement extrinsic motivators, such as money (e.g., Aljumah, Reference Aljumah2023; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zheng, Sui, Yi, Liu, Luan and Chen2021). These intrinsic motivators include so-called psychological rewards, ranging from perceived supervisor support and recognition (e.g., De Gieter, De Cooman, Pepermans & Jegers, Reference De Gieter, De Cooman, Pepermans and Jegers2010; Honig, Reference Honig2021). In this regard, other studies have proposed a reverse relationship; that is, they consider that intrinsically motivated employees perceive the pay they receive in a particular way, which in turn increases their PS (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hongwei, Hongting, Shan, Chang and Jiang2019). In summary, the evolution of research shows a shift from purely economic models toward approaches that view pay as part of a broader set of psychological, social, and cultural factors associated with motivation (Ten Hoeve, Drent & Kastermans, Reference Ten Hoeve, Drent and Kastermans2024). This underscores that, while pay is important, it alone is not sufficient to ensure happiness, commitment, or optimal performance (Almadana Abón et al., Reference Almadana Abón, Molina Gómez, Mercadé Melé and Núñez Sánchez2024).

Discussion

Advancing any field requires a prior understanding of its existing literature (Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao & Bresciani, Reference Paul, Lim, O’Cass, Hao and Bresciani2021). This study analyzes the scientific literature on pay satisfaction, conducting bibliometric research of 539 articles available in the Web of Science Core Collection database for the period 1966–2024. The analytical approach encompassing both a descriptive perspective and a more in-depth approach using bibliometric techniques and tools, particularly the Visualization of Similarities (VOS) viewer software.

One of the key findings of this research is the steady growth of publications and citations since the year 2000, with a notable increase in the last decade. This upward trend underscores the growing interest and advances in the field of pay satisfaction research. In this vein, this review first provides a more comprehensive understanding of the main actors shaping research on pay satisfaction – articles, authors, journals, countries, and affiliations – thus offering academics and professionals a useful reference repertoire for identifying sources of expert knowledge in the field (practical contribution). Second, the review outlined the nomological network of the most relevant thematic groups and showed the multiple ways in which pay affects employee satisfaction. This influence is manifested through its interactions with antecedents (e.g., antecedents, performance, and gender) and consequences (e.g., job satisfaction, commitment, and motivation), as well as in different situational contexts (e.g., sector and country). This constitutes a theoretical contribution. These contributions align with the objectives of bibliometric reviews, which aim to promote theoretical and practical advances (Mukherjee, Lim, Kumar & Donthu, Reference Mukherjee, Lim, Kumar and Donthu2022).

Future lines research

Moving forward, future researchers may find motivation in the sustained growth of publications in this field.

From the #Antecedents, pay communication thus stands out as a cost-effective and efficient tool for companies to convey recognition and support to employees, consolidating its status as a relevant topic in human capital management (e.g., de la Torre-ruiz et al., Reference de la Torre-ruiz, Cordón-Pozo, Vidal Salazar and Ortiz-Perez2024; Young et al., Reference Young, Aronoff, Goel, Jerome and Brower2023). The findings reinforce the importance of designing transparent, equitable, and consistent compensation systems to improve satisfaction and well-being at work. Nevertheless, despite new global regulations, with a particular and growing focus on pay transparency and corporate social responsibility (e.g., Cullen, Reference Cullen2024), research on pay communication is still in its early stages (Bamberger & Alterman, Reference Bamberger and Alterman2024). Research on the dimensions of pay transparency and pay satisfaction not only adds value to organizational theory, but also has practical applications for designing more inclusive and equitable policies. This line of research is essential to meet the expectations of an increasingly informed and demanding workforce, as well as to help firms adapt to growing transparency regulations in the European Union, where the principle of equal pay has recently been consolidated through pay transparency measures (see Directive (EU) 2023/970). Exploring this area will allow for unraveling the dynamics among communication, equity, and satisfaction, providing companies with key tools for talent management in fairer.

From the #Performance mainly encompasses research that in some way links performance and pay satisfaction. This performance can affect how employees value their pay, and at the same time, pay satisfaction can influence employees’ performance. Despite advances in this field, recent studies highlight the need to consider workforce diversity and analyze whether these relationships are influenced by certain individual characteristics. For example, Li, Duan, Chu and Qiu (Reference Li, Duan, Chu and Qiu2023) identified four distinct worker profiles differing in their satisfaction with their pay, which, in turn, resulted in differences in their job performance. Therefore, organizations need to transform the concept of management into that of classification management to design the reward system. Future research is encouraged to explore how the personalization of reward systems, taking diversity into account, affects work performance, and what strategies maximize pay satisfaction for different profiles within the firm.

From the #Gender highlights the crucial role of gender in pay satisfaction studies. This line of research underlines the ´paradox of the contented female worker‘, and the challenges associated with the pay gap and job segregation (e.g., Brüggemann & Hinz, Reference Brüggemann and Hinz2023). The findings of the studies in this cluster emphasize the need for more inclusive and equitable approaches in pay policies to address persistent inequalities and foster fairer work environments. Future research is encouraged to explore how perceptions of pay satisfaction vary according to the type of reference point used (same sex, opposite sex, or same industry). This approach would allow for a deeper understanding of how perceptions of pay satisfaction are formed and to what extent employment increase awareness of inequality.

From the #Job satisfaction, pay satisfaction is emphasized as a key component of job satisfaction. The findings from these studies can help companies design more effective compensation strategies to increase job satisfaction and thus reduce turnover. For instance, recent studies have highlighted the relationship between pay satisfaction and burnout, especially in high-pressure sectors, such as healthcare (e.g., Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Sener, Drake and Marley2023). On the other hand, given the cost pressures faced by many firms, paying higher salaries to employees is not always an option. Given that firms can retain and train employees to acquire the necessary skills (Atkins et al., Reference Atkins, Sener, Drake and Marley2023), future research is encouraged to explore how other aspects beyond the monetary component can influence pay satisfaction. For example, emotional compensation and purpose, and search for meaning in work as a complement to traditional compensation.

From the #Commitment involves creating explicit models to illustrate the causal relationships among pay satisfaction, commitment, employee attitudes and behaviors (i.e. Redondo et al., Reference Redondo, Sparrow and Hernández-Lechuga2023). Although pay-related aspects remain relevant, non-pay factors are recognized as playing an increasingly crucial role. This shift reflects an adaptation to a work environment marked by more complex relationships. A relevant future line of research would be to examine how personalized human resource policies contribute to strengthening pay satisfaction, especially in contexts where workers have autonomy, learning opportunities, and enriching work experiences. It would be interesting to analyze the extent to which these practices enhance organizational commitment and the perception of pay equity among high-potential employees. Future research could also explore the moderating role of individual characteristics – such as gender, age, or career path – in the relationship between such personalization policies and pay satisfaction, which would allow for progress toward a more inclusive model tailored to the needs of a diverse workforce.

From the #Motivation highlights that although monetary compensation is important, it is not the only determinant of worker satisfaction and motivation. The increasing relevance of intrinsic motivation and psychological rewards in promoting satisfaction and job commitment, especially in environments such as healthcare and caregiving, where monetary rewards are limited (De Gieter et al., Reference De Gieter, De Cooman, Pepermans and Jegers2010; Ten Hoeve et al., Reference Ten Hoeve, Drent and Kastermans2024), makes it interesting to investigate how to effectively combine financial incentives and psychological rewards to maximize satisfaction. Future research is encouraged to explore the extent to which the balance between extrinsic and intrinsic rewards enhances employee retention, pay satisfaction, and well-being, while also considering individual differences (e.g., professional values, gender, or age) that could moderate this relationship.

Limitations

Notwithstanding the state-of-the-art overview of pay satisfaction, this study remains limited in several ways. First, we focus on the financial component of compensation (i.e., monetary pay and benefits), which is consequently included as a keyword in our search. However, other non-financial components of compensation (e.g., learning or recognition) could also be included in future studies to develop a broader conceptualization of compensation.

Second, the study is based on a single data source. Like most literature databases, Web of Science does not cover every scientific journal, but only a carefully selected set of the most important core journals for scientific disciplines. Moreover, bibliometric data are not designed exclusively for bibliometric analysis and may therefore contain errors that affect the outcomes of any analysis based on them. To minimize these inaccuracies, the authors have undertaken rigorous efforts and applied due diligence to ensure that the dataset was thoroughly cleansed of erroneous entries prior to conducting the analysis.

Third, the nature of bibliometric methodology itself is a limitation. Qualitative claims stemming from bibliometrics can be quite subjective, given that bibliometric analysis is quantitative in nature, and the relationship between quantitative and qualitative results is often unclear (Donthu et al., Reference Donthu, Kumar, Mukherjee, Pandey and Lim2021). Although fundamental ideas have been presented, this review still has limitations in terms of the breadth and diversity of the bibliometric knowledge considered. Future reviews may extend methods available to guide future research.

Practical implications for management

We believe that this work has important implications for business management and practice. First, the design of hybrid compensation systems that strategically combine monetary and non-monetary rewards (e.g., Almadana Abón et al., Reference Almadana Abón, Molina Gómez, Mercadé Melé and Núñez Sánchez2024) and adapt to the needs of different employee profiles would help companies generate a competitive advantage. This personalization of rewards can help organizations address the challenge of managing generational, sectoral, and gender diversity. Hence, organizations should consider flexible systems that allow employees to choose among different benefits according to their preferences. In this sense, the use of digital platforms that enable employees to manage their benefits in a personalized way through artificial intelligence and technology can be especially relevant.

Likewise, phenomena such as the Great Resignation or employees’ quiet quitting have highlighted the need to consider employee well-being, especially in high-pressure sectors (e.g., health and education). This implies that managers must prioritize psychological support strategies, recognition, and reasonable workloads, beyond pay. Organizations that successfully integrate equitable compensation with a sustainable work environment that combats burnout will be better positioned to increase job satisfaction and ensure the retention of valuable talent in the new post-pandemic era. Related to this, the newer generations of employees are taking into account factors beyond money, such as the purpose of their work, when deciding to remain in their organizations. In this sense, organizations need to offer meaningful jobs that allow them to fulfill these more emotional needs.

Also, managers need to be aware of the importance of implementing transparency policies aligned with new European regulations in order to clearly communicate the components of total compensation. This would help employees better understand all elements of their pay, recognize companies’ efforts to address their needs, and consequently increase the effectiveness of pay policies (de la Torre-ruiz et al., Reference de la Torre-ruiz, Cordón-Pozo, Vidal Salazar and Ortiz-Perez2024).

Finally, human resources departments must carry out continuous evaluations and adjustments. To this end, they should implement periodic feedback mechanisms on pay and job satisfaction to adjust compensation policies in an agile manner. Continuous measurement of pay satisfaction, for example through pulse surveys and analytics to monitor compensation satisfaction in real time, would contribute to this purpose.

Conclusion

This paper provides an overview of the literature on pay satisfaction through a bibliometric investigation. It also offers valuable insights for academics and professionals interested in designing and managing more effective, fair, and equitable compensation systems. Our bibliometric research provides guidance for those wishing to investigate in the field of pay satisfaction, informing them about its most interesting aspects, its research structure, and its theoretical foundations. With this work, we aim to contribute to the proper development of this emerging research field and to encourage compensation researchers to explore new study topics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2025.10072.

Acknowledgments

Sandra Montalvo-Arroyo wants to acknowledge the funding received by the Junta de Andalucía Government Regional, Spain, in the form of a Research Grant to develop his PhD (Predoc-00061/2021), and thereby, this paper. Also, to Faculty of Economics and Business of the University of Granada, and Sustainability Research Team ISDE (SEJ-481). We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, especially on the discussion section.

Funding statement

Sandra’s work was funded by the Junta de Andalucía Government Regional (Predoc-00061/2021) by the Institution ‘Regional Ministry of Economic Transformation, Industry, Knowledge and Universities, Junta de Andalucía,’ Spain.

Funding received from the Junta de Andalucía Government Regional, Spain, by the Institution ‘Regional Ministry of University, Research, and Innovation’, under Grant DGP_PIDI_2024_01934.

For open access charge was funded by the University of Granada.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Sandra Montalvo-Arroyo (smontalvo@ugr.es; corresponding author; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1691-9674) is a PhD student in the Business and Management Department at the University of Granada through a public pre-doctoral contract research grant (00061/2021) from the ‘Regional Ministry of Economic Transformation, Industry, Knowledge and Universities, Junta de Andalucía,’ Spain. She is a member of the research group Innovation, Sustainability, and Development (ISDE-SEJ 481).

Alejandro Ortiz-Perez (aleortiz@ugr.es; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1595-0917), PhD, is an Assistant Professor in Human Resource Management and Business Strategy. He is a full member of the research group Innovation, Sustainability, and Development (ISDE). His research interests are related with the analysis of environmental strategies in the supply chain, human resource management and organizational behavior. He is author of multiple works in prestigious academic journals such as, Business Strategy and the Environment, Employee Relations, among others. He has presented his work in different national and international research events, and conferences.

María Dolores Vidal-Salazar (lvidal@ugr.es; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2437-8297), PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Business and Management Department at the University of Granada. Her research interests include the relationship between several human resource management practices (i.e., personnel training and development, compensation) and firm as well as employees’ performance. Her works have been published in several high-impact journals, such as Human Resource Management or International Journal of Human Resource Management, and she has presented her works international conferences, such as the Academy of Management Conference and EURAM.

José Manuel De la Torre-Ruiz (jmtorre@ugr.es; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8316-8383), PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Management Department at the University of Granada (Spain). He is a Full Member of the research group Innovation, Sustainability, and Development (ISDE-SEJ 481). His primary research interests are human resource management and organizational behavior. He is author of multiple works in prestigious academic journals such as, Business Strategy and the Environment, Management Decision, Small Group Research, International Journal of Manpower, among others.