Introduction

Founded by activists involved in the Spanish 15M demonstrations, Partido X surged out of nowhere in the 2015 Spanish elections. Fed up with their mainstream parties’ endless corruption scandals, millions of Spanish voters were convinced by Partido X's denouncements of austerity and its championing of transparency, popular sovereignty and democratic renewal. So, before the party's leaders knew what was happening, they were swept into government, soon negotiating with its senior coalition partner, the PSOE, the introduction of binding monthly national plebiscites.

Or so it might have happened. Instead, Partido X completely failed at the voting booth, while fellow upstart Podemos managed to gather over 20 per centFootnote 1 – despite the fact that Partido X seemed just as well positioned as Podemos to profit from the mainstream party malaise among the Spanish electorate, if not better: Its message resonated well with Spanish voters, it stayed clear of dinosaur left‐wing ideology and rhetoric (even clearer so than Podemos) and it had enlisted a tax‐evasion whistleblower as its lead candidate (not a relatively elitist academic as Pablo Iglesias was). Despite all this, Partido X was outclassed by Podemos. This paper suggests a set of crucial factors which can account for this particular and many other cases of challenger party success and failure.

But does it matter which challenger carries the day? The example of Southern Europe may illustrate that it does. In Italy, the competitor of the Five Star Movement, Italia dei Valori, would certainly not have formed a coalition with the Lega, but probably with a decimated Partito Democratico. In Greece, a victorious KKE or Antarsya might have led Greece out of the euro. And if, in Spain, Partido X had captured Podemos' electorate, it might have put more emphasis on reforming the polity than on simply changing the government's policies.

Political scientists agree that challenger parties, defined as those parties that have never been in government (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020, p. 17), have been on the rise, and they can present a cornucopia of reasons for this. However, they have so far been hard‐pressed to explain why specific challenger parties carry the day and not others. This reticence is unfortunate given the evident importance of challenger parties for many countries’ politics (including, by now, government formation and national policy making). Recently, a few studies have assessed party‐level determinants of challenger party success, but have not yet arrived at a theory of satisfactory explanatory force (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Giuliani & Massari, Reference Giuliani and Massari2019).

We propose and test a more comprehensive, causes‐of‐effects explanation which is theoretically based on successful communication. In contrast to an effects‐of‐causes approach that studies whether a specific cause has a measurable effect, a causes‐of‐effects approach begins the inquiry with an effect (in our case, success and failure of challenger parties) and provides explanations for it (Goertz & Mahoney, Reference Goertz and Mahoney2012, Chapter 3). In this pursuit, our main contribution is to pay attention to a neglected, major determinant of challenger party success, namely, the availability of a communication channel, and integrate it into a theory of electoral success via successful communication. We argue that a party's message matters, but for distinguishing between electoral successes and failures the capacity to make oneself and one's message known is more important. We thus challenge the literature's focus on challenger parties’ messages and the widespread claim that closing a representational gap is the decisive step for a challenger to take (e.g. De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Meguid, Reference Meguid2008; van de Wardt & Otjes, Reference van de Wardt and Otjes2021). The second neglected aspect of successful communication on which we focus is the importance of the prominence of party leaders.

Empirically, our approach is also innovative as it combines both a cross‐country comparison, a range of party‐level predictors, and a low threshold for party inclusion. Furthermore, we propose a straightforward quantitative measure of a party leader's previous prominence, innovating in a field where the difficulty to quantify leadership qualities has made accumulation of knowledge difficult (Lobo, Reference Lobo2018). Finally, we make a novel contribution by subjecting the common (often implicit) claim, that a populist message heightens challenger parties’ electoral chances, to an empirical test on the party‐level.

We find that successful challengers were those able to contact a large share of the electorate repeatedly and independently of the mass media's regular reporting on party politics. Specifically, these parties could spread their message through (and due to) various ingenious means of outsider mass contact: TV talk shows, radio, activism, live shows, etc. In terms of the message, we find that parties can exploit existing representational gaps and employ populism to improve their electoral lot, given that these messages are amplified by outsider mass contact. We also find that sporting what we call a locomotive, that is, a prominent party leader who is well‐known prior to and independent of his or her party's prominence, greatly helps challengers pull clear of their competitors.

To identify these effects, we build an original dataset, and regress party characteristics on vote gain. We collected data on 78 challenger parties in five countries (Ireland and Southern Europe) during the electoral fallout of the Great Recession (covering all national and European elections between 2010 and 2016). We measured leader prominence with Google Trends, determined parties’ means for mass contact with available (online) resources, and semi‐automatically coded party manifestos for parties’ stances on austerity and their use of populism. Our results are robust to various model specifications.

Determinants of challenger party success

The vast literature on electoral behaviour is able to explain challenger parties’ rising fortunes by pointing to, on the one hand, long‐term developments such as increased affluence (Hino, Reference Hino2012; Kitschelt, Reference Kitschelt1988), the rise of postmaterialist values (Grant & Tilley, Reference Grant and Tilley2019; Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019), economic globalization (Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012), government parties’ colonization of the state (Katz & Mair, Reference Katz and Mair1995), and on the other hand, short‐term unresponsiveness on the part of the mainstream parties (Angelucci & Vittori, Reference Angelucci and Vittori2021; Morgan, Reference Morgan2011; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2019). Such perceived representation failure can be due to voters’ disappointment with the state of the economy (Golder, Reference Golder2003; Gomez & Ramiro, Reference Gomez and Ramiro2019; Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016), the government's policies (Morgan, Reference Morgan2011) or with the way politics is done (Hanley & Sikk, Reference Hanley and Sikk2016; Sanhueza Petrarca et al., Reference Sanhueza Petrarca, Giebler and Weßels2022). For the context of the Great Recession such disappointment was indeed widespread and challenger parties seem to have profited from this (Bosch & Durán, Reference Bosch and Durán2019; Giuliani & Massari, Reference Giuliani and Massari2019; Hernández & Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016). Especially during crises, when mainstream parties struggle to sustain their voters’ loyalty, the ‘cracks in the armor of the major parties’ (Gerring, Reference Gerring2005, p. 98) can widen, improving challengers’ electoral chances. Differing political institutions, especially electoral ones, also contribute considerably to explaining the temporal and international variance in challenger party success (e.g. Bolleyer & Bytzek, Reference Bolleyer and Bytzek2013; Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Riera and Roussias2015; Jackman & Volpert, Reference Jackman and Volpert1996; March & Rommerskirchen, Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015; cf. Grant & Tilley, Reference Grant and Tilley2019). However, none of these factors operate at the party‐level and thus they cannot account for why a specific challenger party becomes successful.

While this differential electoral success of challenger parties per se has rarely been studied, some subgroups of challenger parties have received more attention, for example, new parties, niche parties, populist parties and parties of certain ideological shades (especially radical right, radical left and green parties). The most robust finding here is that parties, in order to be successful, have to lay claim to a part of the salient issue space (e.g. Abedi, Reference Abedi2002; Krause, Reference Krause2020; van de Wardt & Otjes, Reference van de Wardt and Otjes2021; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021). In these studies, the units of analysis are typically elections (over time and/or across countries) and the dependent variable is the success of the national representative of a certain party type (populist, new, radical right, etc.). In other words, these studies, too, usually do not pit individual parties of a certain type against each other. Even case studies of successful challenger parties give little to no room to the competitors (e.g., Bosch & Durán, Reference Bosch and Durán2019; Conti & Memoli, Reference Conti and Memoli2015; Lisi et al., Reference Lisi, Sanches and dos Santos Maia2021; an exception is Tsakatika, Reference Tsakatika2016).

There are a few studies which not only compare challenger parties with each other, but also include unsuccessful parties and those of similar ideology in the same election. Giuliani and Massari (Reference Giuliani and Massari2019) compare parties’ gains and losses across the EU before and during the Great Recession. They find that new parties and those advocating euroscepticism do better, but their limited party‐level‐predictors and explained variance make it difficult to account for any individual party's electoral fate. De Vries and Hobolt (Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020) contend that niche issues (immigration, environment, European integration) and anti‐elite rhetoric decisively influence challenger parties’ vote share but they, too, struggle to discriminate failures from successes due to relatively low explained variance (4%). In other words, these studies successfully demonstrate the effects‐of‐a‐cause (a representational gap) but they do not yet give a comprehensive account of the causes‐of‐an‐effect (challenger party success). Finally, Wieringa and Meijers’ study (Reference Wieringa and Meijers2022) adds an important predictor, that is, political experience of the party leader, but their sample is restricted to new parties in the Netherlands.

In this contribution, we take a more systematic and encompassing approach to the study of party‐level determinants of challenger parties’ electoral success. We cover the three crucial aspects of (challenger) party communication while using a sample of parties broadly representative of challenger parties in today's consolidated Western democracies. Specifically, we examine the importance of challengers’ political messages (catering to a representational niche and featuring populist ideas) not in comparison with mainstream parties but for coming out on top among other challenger parties. In doing so, we juxtapose and relate the influence of the party's message to two previously ignored, important party characteristics which aim at effectively publicizing the party, namely large‐scale repeated contact with voters and a party leader's previous prominence.

Importantly, this study is not inquiring into the proven effects of party performance (in government) or the durability of a party's following; rather, it starts where these two phenomena leave off. During the Great Recession, mainstream parties had disappointed many of their voters, who turned away from them (Bartels, Reference Bartels, Bartels and Bermeo2014; Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). From there, challenger parties could vie for these voters – based on other ways of attracting electoral support, to be described in the following.

Challenger party communication

Parties aiming to convince voters of their value must succeed on several fronts. According to a basic model of communication, the most important party‐level characteristics should be the party's message, the chosen communication channel and the sender itself (Berlo, Reference Berlo1960). Leaving out any of these necessarily diminishes the explanatory power of a model of communicative, and therefore electoral, success (McGuire, Reference McGuire1989).Footnote 2 Hence, we turn to each theoretically necessary component in turn, and finally to their interaction.

The channel

Much scholarly attention has focused on challenger parties’ messages while other components of communication have often been neglected when explaining the effectiveness of parties’ communication efforts.Footnote 3 Existing studies often seem to assume that the channel of communication is similar for all parties, when in fact parties’ means to contact the electorate differ greatly.Footnote 4 This is true not just when comparing large and small parties, or government and opposition parties. Even before entering parliament (at which point the media usually allows for converting one's vote share into airtime, Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Riera and Roussias2015), some parties manage to reach potential voters much better than others. An example may illustrate that establishing such a channel of communication can be a matter of determined, purposive behaviour.

Before founding Podemos in early 2014, its founders had worked for years to build a loyal audience, to whom they could spread their message. Starting in 2010 on a local television station, they diligently broadcasted political talk shows week after week – and re‐broadcasted them on YouTube and via social media channels. They slowly rose through the media prominence hierarchy, honing their skills and professionality along the way. Benefitting from the Spanish media's infotainment format, and from TV channels’ interest in inviting controversial guests to their talk shows, party leader Pablo Iglesias eventually made it to prime‐time programs. His breakthrough came in April 2013, a year before the fateful European elections, when he appeared on a small, but national TV channel in a conservative talk show. This led to a range of invitations by talk shows on the most‐viewed Spanish TV channels over the rest of the year (Gallardocamacho & Lavín, Reference Gallardocamacho and Lavín2016).

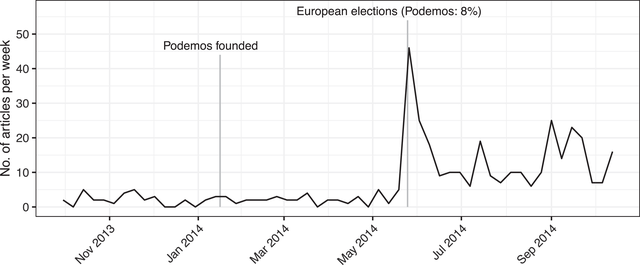

An often‐overlooked fact is that the founding of the party itself in early 2014 was largely ignored by the Spanish mainstream media. But because the founders of Podemos had built up their own means of mass contact they could convince and mobilize voters nonetheless: This way they obtained 8 per cent in the European elections, which in turn made them overcome the crucial first barrier of newsworthiness (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Challenger party newsworthiness: Article headlines containing ‘Podemos’ in top Spanish newspapers (El País, El Mundo, ABC). Note: ‘Podemos’ means ‘we can,’ so that even before the foundation of the party a few headlines per week contain this term. Data: Factiva.

While in the past a strong connection to an already organized social group may have been crucial (Bolleyer & Bytzek, Reference Bolleyer and Bytzek2013), today this might be dispensable: Challenger parties successfully opening up communication channels, which bypass the traditional news media, are not a rare phenomenon anymore. In Italy, Beppe Grillo managed to reach his potential adherents through his live shows, occasional street activism and especially through his hugely popular blog (Pepe & di Gennaro, Reference Pepe and di Gennaro2009). Syriza in Greece was able to harness the extraordinary wave of anti‐memorandum protests to deliver its message to the angry participants (Altiparmakis, Reference Altiparmakis2019; Tsakatika, Reference Tsakatika2016). Or take the 2021 meteoric rise of ‘There is such a people’ in Bulgaria, which was essentially based on its leader's more than 4000 broadcasts of a highly popular evening talk show, during which he could not only disseminate his views but also build rapport with his viewers. In short, winning over voters through self‐made mass contact seems to have become a passable road for challenger parties.

What these examples also have in common is that mass contact does not hinge on party status. On the contrary, voters are contacted not primarily by a political party (with its transparent electoral interests), but by someone from outside the political game proper. Such communication chimes in well with accounts of political disaffection (Pharr & Putnam, Reference Pharr and Putnam2018). Further support comes from political psychology, which stresses that successful leaders need to establish trustworthy representation. Without sustained mass contact, party leaders must find it difficult to construct themselves as representatives of voters in terms of values, norms and behaviour (Reicher et al., Reference Reicher, Haslam, Platow, Rhodes and Hart2014). Hence, the build‐up of such a relationship of representation is partly based on, but not limited to, the publicization of a party's policy proposals.

Hypothesis 1: The more extensive a challenger party's means (outside of regular party politics) for regularly contacting a considerable share of the electorate, the better its electoral performance. (Mass contact hypothesis)

The sender

The literature on the importance of leaders remains inconclusive. Some have found that voter perceptions of leaders have seldom decided elections (see several contributions in King, Reference King2002), since ‘issues of performance and issues of policy loom much larger in most voters’ minds than do the issues of personality’ (King, Reference King2002, p. 220). Others, based on longitudinal data and more sophisticated statistical methods, have found instead that leader favourability can have a decisive impact on election outcomes (Garzia, Reference Garzia2014). Acknowledging the lack of a general consensus, we argue that leaders should matter more whenever parties matter less, including in small or recently founded challenger parties (Aarts et al., Reference Aarts, Blais, Aarts, Blais and Schmitt2013; Arter, Reference Arter2016; Garzia, Reference Garzia, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis‐Beck2016). In an age of personalized politics, party leaders are not only principal senders of parties’ programmatic messages, they also often represent the party to the voters, sometimes to the point of embodying it (Alexiadou & O'Malley, Reference Alexiadou and O'Malley2021; cf. van der Pas et al., Reference van der Pas, De Vries and van der Brug2013). In fact, Garzia (Reference Garzia2014) finds that accounting for perceptions of leadership better explains party identification than sociological models do. This is also evident in the literature on the coattail effect that assumes an electoral benefit for a leader's party in legislative elections following a presidential (Ferejohn & Calvert, Reference Ferejohn and Calvert1984) or gubernatorial (Samuels, Reference Samuels2000) election.

Leader effects studies gauge leaders’ favourability (Aarts & Blais, Reference Aarts, Blais and Schmitt2013; Garzia, Reference Garzia2014) and voters’ opinions of party leaders’ personality characteristics (King, Reference King2002; Lobo, Reference Lobo2018). However, the first crucial hurdle is sheer name recognition (van Kessel, Reference van Kessel2013, p. 193); hence, many challenger parties struggle with the fact that ‘nobody knows who the hell [they] are’ (Graham Booth, UKIP MEP in 2008, quoted in van Kessel, Reference van Kessel2013, p. 193). A charismatic personality may help (Arter, Reference Arter2016; Chaisty & Whitefield, Reference Chaisty and Whitefield2022) but there are other ways (innovation, notoriety, etc.) to achieve distinctiveness and thus let potential supporters know about the party's existence (Harmel & Svåsand, Reference Harmel and Svåsand1993). Leaders have many functions to fulfil but for a fledgling challenger party trying to make its voice heard, the most important one is making the party identifiable through the leader (Arter, Reference Arter2016; Harmel & Svåsand, Reference Harmel and Svåsand1993). Thus, while Wieringa and Meijers (Reference Wieringa and Meijers2022) have recently argued that a leader's parliamentary competence matters, we hold that publicity is the essential asset for fledgling challenger parties. It is hard to imagine that such successful challengers as Beppe Grillo's Five Star Movement, Macron's En Marche!, or Zelensky's Servant of the People could have performed as they have without the previous prominence of their leaders (Chaisty & Whitefield, Reference Chaisty and Whitefield2022).

For these personalities, we use the term locomotive: A widely known candidate who commands the steam needed to pull a challenger party to victory – or at least to increase its electoral chances. The term is sometimes used in the literature, for example, where local candidates in Brazil associate their ticket with the governor (Samuels, Reference Samuels2000), or when, in Russia, governors are placed on national party lists to use their visibility for the governing party (Moraski, Reference Moraski2017). We extend the metaphor: Not just incumbents, but any previously prominent person turned party leader (or frontrunner) can function as an electoral locomotive.

Hypothesis 2: The more prominent a new party's leader (independent of her party's prominence), the better the party's electoral performance. (Locomotive hypothesis)

Apart from our focus on the communication channel, we test hypotheses which have been put forward and examined by existing studies, of which the most prominent applicable claims pertain to parties’ programmatic messages.

The message

New parties can emerge where there is programmatic space to occupy (Hillen & Steiner, Reference Hillen and Steiner2020; Hino, Reference Hino2012; Ignazi, Reference Ignazi1992; van de Wardt & Otjes, Reference van de Wardt and Otjes2021) and such exclusive fit between parts of the electorate and a challenger party helps the latter to survive in the long run (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; March & Rommerskirchen, Reference March and Rommerskirchen2015; Rochon, Reference Rochon1985). Thus, many challenger parties make programmatic offers not covered by other parties (van de Wardt et al., Reference van de Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014), and this appears to help challenger parties thrive (e.g., Mauerer et al., Reference Mauerer, Thurner and Debus2015; Spoon & Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2019; Wagner, Reference Wagner2021), or at least helps voters already inclined to vote against the mainstream decide on a specific challenger (Bosch & Durán, Reference Bosch and Durán2019; Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016). According to this logic, in the electoral context of the Great Recession in Southern Europe and Ireland, challenger parties’ best bet in terms of an issue neglected by the mainstream parties should be an anti‐austerity stance. In all of these countries, both major mainstream parties had implemented highly unpopular austerity policies as a response to a sovereign debt crisis.Footnote 5 This expectation is in line with the literature on the impact of the crisis in Southern Europe, which diagnoses a misalignment between mainstream parties’ neoliberal policies and large parts of the electorate (e.g. Roberts, Reference Roberts2017a), sometimes called a crisis of responsiveness or representation (Morgan, Reference Morgan2011; Roberts, Reference Roberts, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017b). While the economic crisis and especially the post‐2010 austerity policies are often said to have spurred ‘the rise of radical left parties’ (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018, p. 17), we expect that an anti‐austerity stance can also help parties which are culturally and economically not considered left‐wing. In a situation where both left‐ and right‐of‐center mainstream parties implemented austerity, and both left‐ and right‐wing challengers militated against austerity, there is little reason to expect much issue constraint on voters (Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wagner2021; cf. Fenger, Reference Fenger2018). In other words, austerity should be a ‘wedge issue’ potentially capable of prying open the cracks in the established party system (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; van de Wardt et al., Reference van de Wardt, De Vries and Hobolt2014).Footnote 6

Hypothesis 3: The clearer a challenger party champions an issue which is neglected by the mainstream parties, the better its electoral performance. (Representational failure hypothesis)

There is a large literature explaining the rise of populism (e.g. Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Kriesi, Reference Kriesi2014; Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Roberts, Reference Roberts, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017b), citing cultural, economic and political reasons. These studies often imply that some parties do better because they are populist. However, this hypothesis has not been studied by systematically comparing populist to non‐populist parties (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2018). Considering populism's current popularity in political science, this dearth of evidence is surprising, and should be ameliorated:

Hypothesis 4: The more populist a challenger party's message, the better its electoral performance. (Populism hypothesis)

Apart from the independent influences of the three main aspects of electoral communication outlined so far, successful communication crucially depends on interaction, especially between communication channel and message: A fitting message should be particularly effective when combined with a well‐working channel to deliver it.Footnote 7 Hence we expect an interaction effect between channel and message(s):

Hypothesis 5: The more extensive a party's outsider mass contact means, the higher the positive impact of championing a neglected issue on the party's electoral performance. (Megaphone hypothesis A)

Hypothesis 6: The more extensive a party's outsider mass contact means, the higher the positive impact of employing populism on the party's electoral performance. (Megaphone hypothesis B)

In summary, we expect that both an anti‐austerity and a populist stance (a party's message) help challenger parties capture votes, but we also expect – going beyond existing studies – that unconventional avenues for mass contact (the channel) and harnessing a well‐known personality as a party leader (the sender) will be even more decisive in separating the challenger wheat from the chaff.

Data and methods

We tackle our research questions by choosing a most‐similar environment, building an original dataset spanning 78 parties and running ordinary least squares regression models on the variables of interest. Data analysis was done with R (especially Benoit et al., Reference Benoit, Watanabe, Wang, Nulty, Obeng, Müller and Matsuo2018; Hlavac, Reference Hlavac2018; Wickham, Reference Wickham2016; Xie, Reference Xie2021). More specifically, we select five countries in a similar economic and political situation, namely the four major Southern European countries (Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece) and Ireland during the post‐2008 protracted economic vicissitudes (2008–2016), also called the Great Recession. Although the causes and manifestations of the economic crisis somewhat differed among these countries, the general electoral context was the same. They were among the hardest‐hit by the crises and they all suffered from prolonged negative growth and sky‐rocketing unemployment. Also, all five experienced a sovereign debt crisis and their successive governments all found themselves facing EU demands for austerity to which they yielded.Footnote 8 This displeased large swathes of the electorate, who massively punished mainstream parties for the state of the economy (Bartels, Reference Bartels, Bartels and Bermeo2014; Hernández & Kriesi, Reference Hernández and Kriesi2016) and for implementing austerity (Bojar et al., Reference Bojar, Bremer, Kriesi and Wang2020; Hübscher et al., Reference Hübscher, Sattler and Wagner2021; Roberts, Reference Roberts2017a; Talving, Reference Talving2017). This case selection lends itself to identifying determinants of challenger party success, which is appropriate given the limited evidence on the subject so far.

When studying supply‐side determinants of electoral success, ideally, the whole universe of parties attempting to court the national electorate should be studied. This means studying a lot of duds next to the few successful cases (Bolleyer, Reference Bolleyer2013). But most studies either disregard unsuccessful parties completely, or set a relatively high electoral cut off point.Footnote 9 Consequently, associations between failure (and success) on the one hand, and these parties’ strategic choices and individual constraints, cannot be systematically analyzed. This study sets the bar for inclusion lower: We include all non‐regionalist parties which have not been in (national) government and have obtained at least 0.5 per cent in any national election between 2005 and 2020, making for a total of 74 parties (for our main model, details see Supporting Information Appendix A1). According to this criterion, the Greek party system featured the most non‐regionalist challenger parties (27), while the rest of the countries had 9 to 13 parties. Speaking in broad ideological terms, 26 parties were situated on the left, 24 parties occupied center‐left to center‐right positions, and 16 parties were on the right. The remaining eight parties had very limited programmatic offers (e.g., the Greek Hunters Party, or the Spanish ‘Blank Seats’, which promised to leave their parliamentary seats empty to visualize the ballot's ‘blank vote’ option).Footnote 10 More than half the parties (57 per cent) were founded after the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis.

Since we compare only challenger parties, evaluations of government performance should not increase an individual party's vote share. However, particularly bad government performance can increase the pool of disaffected voters in a given country and can thereby increase the overall share of votes for challenger parties in that country, which (among other reasons) necessitates controlling for the effects of individual countries.

Measurement of variables

We briefly describe the measurement of the included variables, while coding details, validity checks, etc., can be found in the methodological Supporting Information Appendix A.

In order to calculate our dependent variable we use the parties’ highest electoral result in any national (post‐)crisis election (2010‐2016) and the 2014 European elections, compared to the highest of the two last pre‐crisis national elections and the 2004 EU elections respectively. Our main dependent variable is the highest achieved vote gain in these elections. We use this aggregate measure because we are interested in the performance of challenger parties in the crisis period as a whole, not at a specific election. Because our dependent measure is not absolute vote share but vote share gain (in percentage points), the influence of pre‐existing party loyalties (party identification from the voters’ point of view) should play a negligible role.

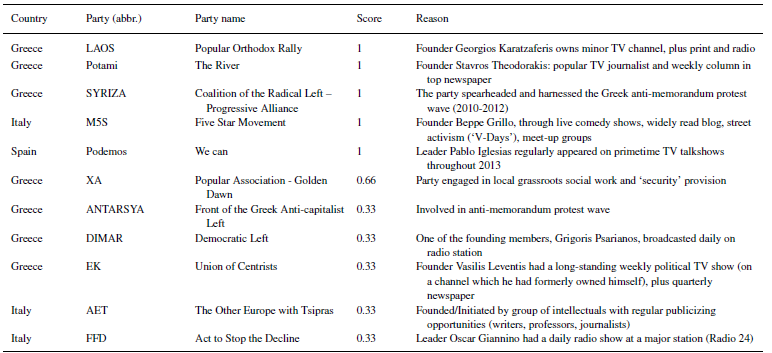

Independent variables. We measure the availability of a means of outsider mass contact on the basis of publicly available information on the occupation and further activities of any party official in a leadership position. Through this we investigate whether the party had a means of contacting voters on a large scale which was not due to it being a prominent political party (see Table 1). We coded as full outsider mass contact the possibility to have regular contact (about monthly) with at least (roughly) 1 per cent of the electorate (but this criterion cannot be applied mechanically, see Supporting Information Appendix A2 for details). More specifically, one of the party leaders must have had either direct access to voters (e.g., as an activist or entertainer) or indirect access through the media (e.g., as a journalist or regular talk show guest), but not because of their prominence as party leaders. The variable was coded as a four‐tier ordinal variable. It was transformed into a continuous one, assuming equidistant values from 0 to 1, because analysis of variance and likelihood ratio tests suggested that the simpler model (with the continuous variable) is to be preferred.

Table 1. Outsider mass contact

Coding decisions are specified in detail in Appendix A2.

We operationalize previously existing prominence of a leader (the locomotive) by measuring voters’ interest in the party's leader before the party was founded. We use Google Trends scores, measuring how often a future party leader's name is googled in the year prior to the party's foundation. In this way we avoid measuring interest due to the party's rising prominence. Because the proposed mechanism rests on making a nascent party known to the public, it should only work in the short term. Hence, parties founded before the onset of the Great Recession automatically score zero on this variable. As a consequence, this variable captures both the prior interest in a future party leader and the newness of a party.

To quantify a party's message in terms of its programmatic stance (on austerity and populism) we analyze party manifestos as the most appropriate ‘authoritative’ party documents which are also available for very small parties (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, van der Brug and de Lange2016, p. 35). We use the available electoral programs from MARPOR (Burst et al., Reference Burst, Krause, Lehmann, Lewandowski, Matthieß, Merz and Zehnter2020), but small parties are usually not included in this database. Hence, for most parties, manifestos were collected with the help of the Internet Archive (2021), which stores historical copies of websites. We use one manifesto per party, namely those pertaining to elections which happened closely after May 2010, when the EU changed its general policy course to advocating austerity. All manifestos were machine‐translated to English.

The semi‐automatic coding procedure is based on Rooduijn and Pauwels’ (Reference Rooduijn and Pauwels2011) recommendation to combine the high validity of human coding with the efficiency of automatic text analysis by pre‐selecting text passages for the coding process (also see Hawkins & Castanho Silva, Reference Hawkins, Castanho Silva, Hawkins, Carlin, Littway and Kaltwasser2018). Thus, we first automatically scanned the first 10,000 characters of each document for a permissive selection of keywords. Then, the identified passages containing 100 words before and after each keyword were handcoded by two independent coders according to each variable's coding rules.

A party's anti‐austerity stance is operationalized as a categorical variable from 0 to 3. It can assume the values 0 (no criticism of austerity policies, describing austerity as painful but inevitable etc.), 1 (criticism of austerity's macroeconomic effects, rejection of individual measures or of austerity's foreign imposition), 2 (general opposition: austerity is wrong in general) or 3 (aggressive, single‐minded dismissal in strong language, e.g., ‘austericide’, ‘blood tax’). Each passage identified by the keywords is coded accordingly, but for each manifesto as a whole the highest value is counted (because higher values subsume lower values on our ordinal scale; for details see Supporting Information Appendix A2). We also conduct several robustness checks with alternative measures, including sum and dummy scores, finding substantively similar results (see Supporting Information Appendix B3.2)

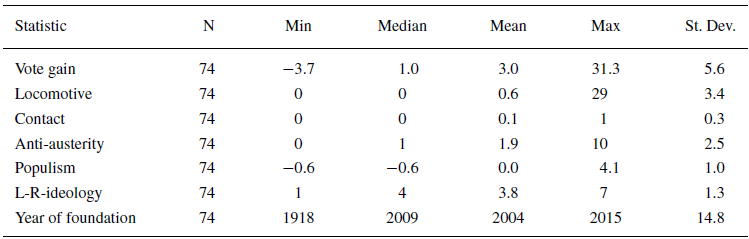

For measuring populism we adhere to its ideational definition (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004) and thus count, on the one hand, how often parties criticize elites as corrupt and juxtapose them to the ‘good people’; and on the other hand, how often parties demand that politics be an expression of the popular will. Summary statistics for our main variables are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary statistics

Turning to control variables, the parties have been assigned an ideological left‐right score between 1 and 7 by the authors (communist to fascist; correlation with Chapel Hill expert survey is 0.93). We add country dummies to the main model to avoid unobserved country‐level characteristics confounding our findings. The baseline for the country dummies is Italy.

We also created control variables measuring extremism (based on the ideology measure) and whether a party is the result of a split. The former could confound our results for a populist or anti‐austerity message, the latter those for the locomotive hypothesis. We also create controls for the number of parties contesting an election, trust in government and several economic conditions (growth, unemployment, bond spread, stock indices). But adding more variables is problematic given our relatively small sample size. Thus, we test these separately (in Supporting Information Appendix B2.2).

Model specification

We estimate OLS regressions with a party's maximum vote gain (compared to pre‐crisis levels) as the dependent variable. To the basic model of our four independent variables, we add ideology as our most important control variable, country dummies and the expected interaction effects. Because of heteroskedasticity, we use Huber‐White standard errors throughout the models. When disaggregating the dependent variable (including various election results of one party as separate observations) standard errors are clustered on the party level.

Results

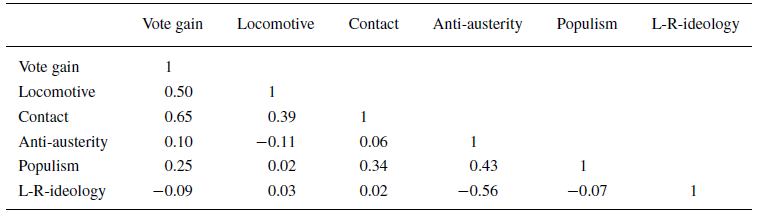

Table 3 presents bivariate correlations: The two variables derived from the manifesto data (anti‐austerity and populism) by themselves only weakly correlate with the dependent variable, while outsider mass contact and the prominent leader variable (a locomotive) correlate moderately highly.

Table 3. Correlations of main variables with each other

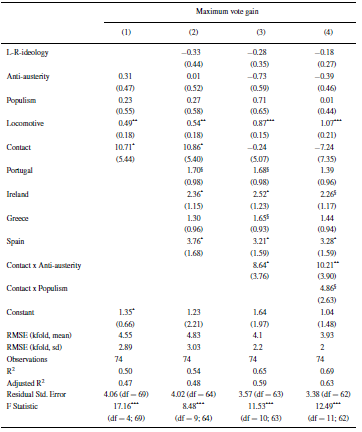

Table 4 presents the results of our main OLS regressions. The unit of analysis is the party. Model 1 shows the results for the independent variables of interest excluding control variables. Model 2 adds the controls, and models 3 and 4 additionally include the expected interaction effects. Including two interactions is not unproblematic given our limited sample size. Hence, we use repeated k‐fold cross validation (10 folds, 30 repetitions) to make sure we did not overfit the data. We find that the RMSE of the cross‐validation test samples decreases from model 3 to model 4, and so does its standard deviation. Also, the RMSE is relatively small in general, given the residuals’ standard deviation (3.93 vs 3.38 for model 4). Thus, we select model 4 as the final model not only because it reflects our theoretical expectations (of a dual interaction) and explains most variance, but also because cross validation indicates no model overfitting. Additionally, variance inflation factors stay below the conventional threshold (5) for all covariates.

Table 4. Main results

Note:

§p < 0.1;

*p < 0.05;

**p < 0.01;

***p < 0.001.

The locomotive hypothesis is strongly supported by the evidence. The coefficient is positive and statistically significant across the models, and increases with completeness of the model. The effect is large in substantial terms: Parties are estimated to gain a full percentage point for each percentage point increase in a party leader's previous prominence (compared to the most prominent politician in a given country).

In contrast, our representational gap hypothesis and our populism hypothesis cannot, by themselves, be confirmed.Footnote 11 While model 2 suggests a significant substantial effect (over 10 percentage points) of outsider mass contact, the coefficient turns negative when introducing the interaction terms (models 3 and 4).

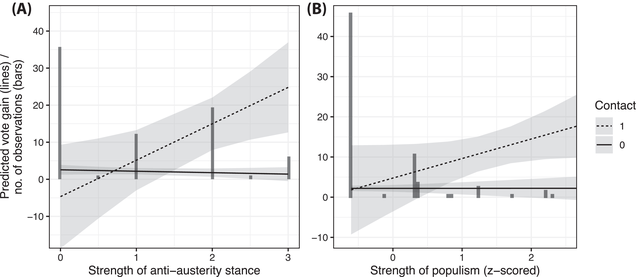

The results of our full model concur with previous studies which found an effect of taking up neglected issues (e.g. De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020), but show that this effect (at least in our case) is not independent of an important, hitherto omitted variable: Figure 2(A) shows that resolute criticism of austerity policies (a score of 2) combined with mass contact can lead to sizable vote gains (around 15 percentage points, rest of covariates at median values) although confidence intervals are relatively large. Similarly, we estimate that a strongly populist message (one standard deviation above the mean) should benefit challengers with 5–14 percentage points, given full means of mass contact (Figure 2B). In contrast, challengers without the ability to independently contact voters cannot expect to profit from either message. Consequently, both megaphone hypotheses, which postulated interaction effects between outsider mass contact on the one hand and anti‐austerity stance and populism on the other hand, are supported by the evidence. These sizable interaction effects contribute to the full model's ability to explain a considerable share of the variance in challenger parties’ vote gains (69 per cent).

Figure 2. Relationship between vote gain (in percentage points) and (A) anti‐austerity stance and (B) populism, for two values of outsider mass contact (no mass contact and full mass contact). Dark gray bars: Number of observations for each value of anti‐austerity/populism. Other variables at their mean. Confidence intervals based on robust standard errors. Same graph but showing all four values of outsider mass contact in Supporting Information Appendix B2.

Our measure of ideology does not have an effect on our dependent variable. Introducing a number of further theoretically plausible controls does not affect the coefficients of our predictors; and these controls also remain small and below conventional levels of significance (see Supporting Information Appendix B2.2). Some of the country dummies, however, exhibit substantial, significant effects, but when dropping them, the predictors’ coefficients stay almost exactly the same (Supporting Information Appendix B2.2).

Robustness checks

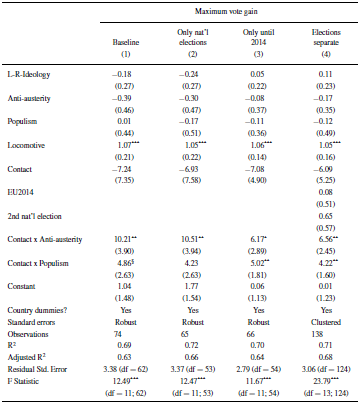

Robustness checks are especially important because of our limited sample size and the influence of high‐leverage observations (i.e., the dependence of our results on a small number of successful cases – also see Table 2 in Supporting Information Appendix B1). Thus, we now turn towards examining whether our results are robust to changes in the sample based on the dependent variable (Table 5).

Table 5. Sample modifications based on DV

Note:

§p < 0.1;

*p < 0.05;

**p < 0.01;

***p < 0.001.

Model 1 repeats the full model as a baseline for ease of comparison. In model 2 we only use national elections, and in model 3 we exclude the elections possibly affected by the ensuing refugee crisis (2015 and 2016). For model 4, we disaggregate the dependent variable using the two first national crisis elections and the EU 2014 elections as separate observations. In general, results are very similar across the four models. However, the interaction between outsider mass contact and an anti‐austerity stance becomes weaker for models 3 and 4. And the second interaction once drops below statistical significance (in model 2). But overall, our main findings hold: previously existing prominence of a leader (the ‘locomotive’) on the one hand, and outsider mass contact together with either an anti‐austerity stance or populism on the other, are both associated with vote gains for challenger parties.

We perform a series of further robustness checks in the Appendix. We transform our dependent variable, using its logarithm and its inverse hyperbolic sine, and show that the residuals are well‐behaved (Supporting Information Appendix B3.1, B5). We also vary the measurement of the covariates and restrict/expand the sample based on various criteria (newness, government experience, Cook's distance, country). Our main findings remain unaltered, although the interaction between outsider mass contact and populism is less robust than the one with an anti‐austerity stance or the locomotive effect, which remain strong throughout the models (Supporting Information Appendix B3). Finally, we take a closer look at the model's over‐ and underpredictions to ascertain whether these cases cast doubt on our theoretical arguments, but we find that, by and large, they actually support our main arguments (Supporting Information Appendix B4).

Conclusion

Countless challenger parties never even cross the public's attention threshold. This article set out to explain what it is about a select few of them that propels them to electoral success. Despite the evident implications for politics and policies, research on party‐level determinants of differential electoral success of challenger parties is still in its infancy. The studies which have broken ground are either restricted to one polity (Wieringa & Meijers, Reference Wieringa and Meijers2022) or highly limited in the coverage of potential influences (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Giuliani & Massari, Reference Giuliani and Massari2019). Our original dataset makes a step to overcoming these limitations: Treating electoral success of challengers theoretically as communicative success, we provide measures of all three essential components of communicative success (sender, message and channel), thus going beyond parties’ political messages and including two hitherto neglected determinants of electoral success, namely the means for contacting voters and a party leader's pre‐existing prominence.

We find that a party leader who was prominent before a new party's foundation can boost that party's vote to an impressive extent. This finding is supportive of the contention that leader effects could turn out to be more substantial than previously assumed if studies could disentangle them from party attachment (Garzia, Reference Garzia, Arzheimer, Evans and Lewis‐Beck2016). While the causes of a leader's previous prominence might well be too diverse to pin down, future studies could explore the exact mechanism through which this locomotive effect works. Also, future research should take into consideration the influence of sheer prominence when trying to determine the impact of other leader characteristics such as popularity and competence. While parties certainly prefer positive evaluations of their leaders, there might indeed be no such thing as bad publicity for parties struggling to achieve ‘distinctiveness’ (Harmel & Svåsand, Reference Harmel and Svåsand1993).

A second way for fledgling parties to attract attention and win over voters is to establish a way of contacting them on a large scale. As most challenger parties are unable to rely on the mainstream media's ordinary reporting on politics, they need their own means of mass contact to make voters aware of their existence, and to propagate their views and identity. This is why we find strong empirical support for an interaction effect between outsider mass contact and an anti‐austerity stance: Championing a neglected issue only helps challengers if they dispose of a megaphone – a means to amplify their voice. In the Appendix (A2), we further discuss whether this finding constitutes a more general challenge to the representational gap hypothesis.

A possibly counterintuitive finding of our study is that a populist message on its own does not lead to vote gains. Although at odds with the amount of media and scholarly attention given to challenger parties marked as populist, this result is in line with the current absence of evidence for an effect of populism on electoral success. But this apparent contradiction can be resolved: We do find (limited) support for the political efficacy of a populist message when it is coupled with outsider mass contact. While the latter may simply function as an amplifier to the populist message, it may also lend credence to the message: An outsider to party politics contacts the populace, offering her‐ or himself as the real representative of the people. This substantive representational aspect of populism clearly deserves further scrutiny.

With regard to the measurement of outsider mass contact, it is inevitable that some country experts will take issue with the coding of particular parties, but we hold that our transparent measurement procedure, plus the applied robustness checks, should go a long way in dissipating doubts. More exact measurement (e.g., by estimating more precisely the numbers of voters in contact with a party, and the intensity of the contact) would be a difficult, yet worthwhile way forward.

How generalizable are our findings? Our results are based on many unsuccessful and a few successful parties. The latter's characteristics naturally shape our results decisively. Consequently, our results certainly need validation in other contexts. Nonetheless, despite its indisputable peculiarities, Southern Europe shares many cultural and political features both with the rest of Europe and Latin America. Although Portugal, Spain and Greece were late in democratizing, their party systems institutionalized relatively quickly (Mainwaring, Reference Mainwaring1998), that is, until the Great Recession. On the other hand, Italy's party system was reshuffled in the 1990s, and Ireland's has exhibited relative stability (cf. Mair, Reference Mair1979). Such variety in the degree of party system institutionalization is found among other geographical groups of democracies as well, including Northwestern Europe. In fact, the democracies of Northwestern Europe have recently experienced unprecedented levels of electoral volatility themselves, expedited during the Great Recession and the subsequent refugee crisis (Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019). Conversely, the populist right has made inroads in Southern Europe as well, and even Ireland seems to move towards a more common strain of multiparty system. In light of these recent developments, Peter Mair's (Reference Mair, Katz and Crotty2006) prediction that across democratic party systems there will be ‘more room’ for challenger parties ‘for the free competition for influence and control’ seems prescient (also see Kayser & Wlezien, Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011). In short, while our sample certainly differs on some political, socio‐economic and cultural traits, we hold that the decisive party system dynamics are in a similar state of flux as in other established democracies to merit cautious generalization.

With respect to the idiosyncrasies of the political and electoral context of the Great Recession, we readily admit that this is not a typical situation. In fact, we chose the particular post‐crisis electoral context not only because the included countries are in a very similar situation to allow for direct comparison (see above), but also because it is conducive to challenger party success due to the mainstream parties’ (perceived) performance failure. So, the effects we found might be smaller in other electoral contexts, and their relative weight compared to other influences (such as economic voting) might vary somewhat, but we see no reason why they should be absent. Future studies could also ascertain how far our findings generalize to mainstream parties, for example, the importance of a previously prominent party leader.

This study has demonstrated that taking all aspects of the communicative process of political parties into account can go a long way in explaining the high variation in challenger party success. Explaining why some challenger parties succeed and others fail will stay a complicated endeavour, not least because our most potent variables are multifarious in form and causes. Future studies should explore these and other potential determinants, and proceed to integrate them with country‐ and election‐level variables.

We started out with the observation that Partido X's message resonated well with Spanish voters’ grievances but that the party failed nonetheless. It would be more correct to say that the party's message could have resonated well with Spanish voters – if the voters had heard it. What the party was missing was an opportunity to effectively communicate its message to the Spanish population.Footnote 12 An opportunity for large‐scale contact, a megaphone so‐to‐speak, could have helped the party broadcast its message. A prominent leader (a locomotive) would have further bolstered its chances for electoral success. Notwithstanding other potential assets not considered here, we hope to have demonstrated that, contrary to simplistic accounts of the Great Recession, it takes much more for a challenger party than a leftist, populist stance to enter the national electoral stage successfully.

Acknowledgements

For their generous feedback the authors would like to thank Hanspeter Kriesi, Elias Dinas and the participants of the latter's colloquium, especially Pedro Martín Cadenas and Sergi Martínez. We would also like to thank the EJPR editors and the three anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and timely, constructive comments.

Open Access Funding provided by European University Institute within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Using publicly available data, no ethics review was required for this study.

Funding Information

Jan Matti Dollbaum's part of this paper was written in the context of the BMBF‐funded research project ‘Protest and Social Cohesion: Comparing Local Conflict Dynamics’ (Research Institute Social Cohesion, Project Identification: 01UG2050CY).

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary information